Abstract

The number of patients with cancer who are age 65 years or older (hereinafter “older”) is increasing dramatically. One obvious aspect of cancer care for this group is that they are experiencing age-related changes in multiple organ systems, including the brain, which complicates decisions about systemic therapy and assessments of survivorship outcomes. There is a consistent body of evidence from studies that use neuropsychological testing and neuroimaging that supports the existence of impairment following systemic therapy in selected cognitive domains among some older patients with cancer. Impairment in one or more cognitive domains could have important effects in the daily lives of older patients. However, an imperfect understanding of the precise biologic mechanisms underlying cognitive impairment after systemic treatment precludes development of validated methods for predicting which older patients are at risk. From what is known, risks may include lifestyle factors such as smoking, genetic predisposition, and specific comorbidities such as diabetes and cardiovascular disease. Risk also interacts with physiologic and cognitive reserve, because even at the same chronological age and with the same number of illnesses, older patients vary from having high reserve (ie, biologically younger than their age) to being frail (biologically older than their age). Surveillance for the presence of cognitive impairment is also an important component of long-term survivorship care with older patients. Increasing the workforce of cancer care providers who have geriatrics training or who are working within multidisciplinary teams that have this type of expertise would be one avenue toward integrating assessment of the cognitive effects of cancer systemic therapy into routine clinical practice.

INTRODUCTION

Cancer is largely a disease of older age,1 and the absolute number of patients with cancer who are age 65 years or older (hereinafter “older”) will increase dramatically over the coming decades with the graying of America.2 Unfortunately, this demographic imperative is coupled with a workforce shortage of cancer providers who have geriatrics training or who are working within multidisciplinary teams that have this expertise.3–5 Consequently some oncologists feel ill prepared to address the complex and unique treatment and survivorship issues of their older patients.6

The most distinctive aspect of cancer care of older patients is that they are experiencing age-related changes in multiple organ systems, including the brain, which complicates decisions about systemic therapy and assessments of post-treatment functional outcomes. One age-related change that is often cited as a particular concern of older patients and survivors is cognitive impairment.7,8 Therefore, oncology care providers will need to be familiar with the risks for adverse cognitive effects of cancer when prescribing systemic therapy to older patients and be able to screen for symptoms of cognitive impairment when providing care for this age group.

Cancer-related cognitive impairment was first described three decades ago,9 and a fairly consistent, albeit not universal, picture of these deficits has evolved.10–12 This article uses conceptual frameworks of aging to synthesize what is known about cognitive impairment in older patients with cancer, with an emphasis on identification of the subgroups of older individuals at risk for cognitive impairment after systemic therapy. Finally, this review highlights clinical and research implications of the current body of knowledge for the care of the growing population of older patients with cancer.

THEORIES OF AGING AND COGNITIVE IMPAIRMENT

Given the heterogeneity in health observed across older patients of the same ages, the risks for cognitive impairment after cancer systemic therapy can best be understood through the lens of aging theories. Aging can be considered the net effect of the temporal accumulation of damage to cellular processes and systems, loss of compensatory mechanisms (ie, diminished reserve), and increased vulnerability to disease and death. Closely aligned to this definition is the clinical concept of frailty, which can be considered a phenotype of aging. This phenotype is characterized by diminished reserve and resistance to stressors caused by collective declines across organ systems leading to vulnerability to insult and adverse outcomes, including cognitive impairment.13–16 Thus, it is logical that older individuals with low reserve might be more vulnerable to cognitive impairment than those with greater reserve or younger patients after stressors such as cancer therapy.10,17

Aging is also associated with the accumulation of multimorbidities (eg, diabetes, heart disease) that have direct18 and indirect19 neurovascular effects on cognition. Thus, older patients with specific multimorbidities may represent a subgroup vulnerable to accelerated aging and cognitive impairment after cancer systemic therapy.

On a molecular level, aging is characterized by cell senescence. Senescence refers to the state of cells that are metabolically active but can no longer replicate. These senescent cells evoke inflammatory responses and accumulate at sites of pathology, including the brain.20,21 Senescent cells can also be considered biomarkers of the frailty phenotype22 that place patients with cancer at risk for cognitive impairment. However, the targets for certain cancer treatments negatively affect biologic markers of aging such as senescence. For instance, increases in tumor suppressor mechanisms through the p53 pathway may be effective in treating cancer but are associated with increased cell senescence, which could in turn lead to accelerating aging and increased risk for cognitive impairment.20,21

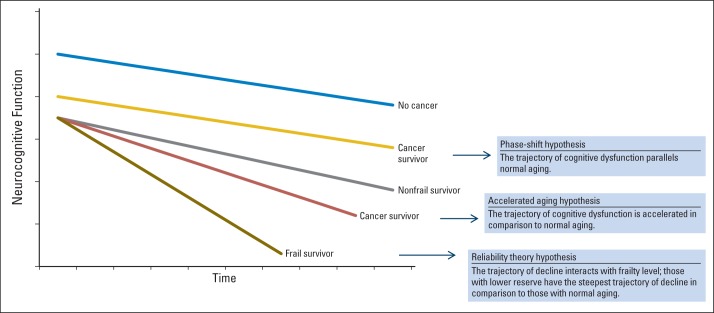

This framework raises several provocative questions. If cancer therapy has an impact on cognitive function, does the trajectory of cognitive impairment parallel that of normal aging (phase shift hypothesis)? Or is the trajectory of dysfunction accelerated in comparison to normal aging (accelerated aging hypothesis)?10 As depicted in Figure 1, the phase shift hypothesis postulates that patients with cancer experience post-treatment decrements in cognitive function compared with their noncancer counterparts, but further age-associated decline over the course of survivorship occurs at the same rate as for individuals without a cancer history.

Fig 1.

Trajectories of cognitive decline based on theories of aging and frailty phenotype. Adapted from Ahles et al.10

Alternatively, if cancer and its treatment are actually accelerating the aging process, we would expect the slope of decline in cognitive function to be steeper for patients in active treatment and survivors relative to their noncancer cohorts. These are not mutually exclusive hypotheses in that a subgroup of cancer survivors (perhaps the majority) may demonstrate the phase shift trajectory, whereas another vulnerable group may demonstrate an accelerated aging trajectory.

In addition to examining specific trajectories of aging, systems theories of aging can provide insights regarding cognition and cancer treatment. One of these, the reliability theory of aging, proposes that complex biologic systems have developed a high level of redundancy (“reserve”) to support survival.23 However, highly redundant systems have a high tolerance for the accumulation of damage when alternate pathways exist and repair does not occur. Loss of redundancy is influenced by the initial extent of system redundancy (primarily genetically determined), the systems' repair potential, and factors that increase failure rate and/or repair ability such as poor health care and lifestyle risk factors such as smoking, obesity, limited physical activity, and/or exposure to environmental toxins. Someone with a low failure rate and/or high repair potential will show fewer signs of biologic aging as they age chronologically, whereas someone with a high failure rate and/or low repair potential will age more rapidly, as evidenced by the development of a disease associated with a specific set of system failures or frailty with a patchwork of failures across multiple systems, hence the differences between chronological and biologic (physiologic) age.

The reliability theory is useful for understanding the cognitive effects of cancer and its treatments in older patients because it does not depend on a given treatment affecting a specific biologic pathway.10 Thus, one patient may be vulnerable to the DNA-damaging effects of a particular chemotherapy regimen, whereas another patient may be susceptible to the impact of the hormonal milieu of endocrine treatments.10

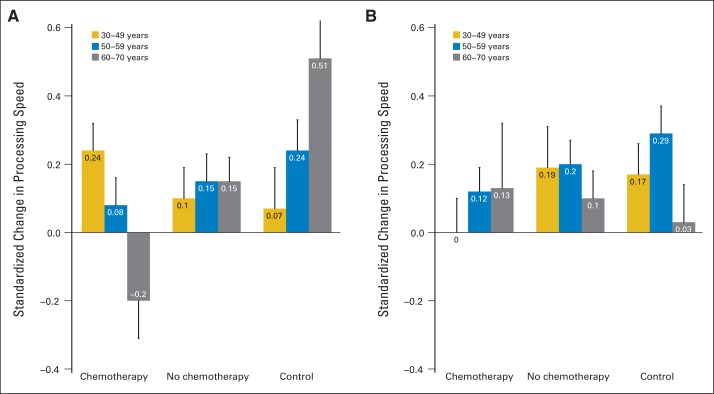

This framework has potential clinical value because it suggests that the trajectories of cognitive decline are dependent on premorbid cognitive and other system reserves. This idea is supported by research by Ahles et al10,17 demonstrating that women age 60 to 70 years with low baseline cognitive reserve who underwent chemotherapy had lower performance on tests of processing speed compared with those not receiving chemotherapy, younger patients, and controls (Fig 2). The next section reviews the key evidence on the cognitive effects of cancer systemic therapy in older patients against the backdrop of theories and processes of aging.

Fig 2.

Pre- to post-treatment change in processing speed by treatment, age group, and level of cognitive reserve among patients with breast cancer (assessed by the Wide Range Achievement Test-Reading. (A) Patients with low cognitive reserve, (B) patients with high cognitive reserve. The bar heights represent post-treatment averages pooled over assessments; the error bars represent the standard error of the averages accounting for repeated measurements from the same individuals. Reprinted with permission.10,17

EVIDENCE FOR COGNITIVE IMPAIRMENT AFTER SYSTEMIC THERAPY

Neuropsychology Studies

The largest body of evidence about cognitive impairment in older patients with cancer in association with systemic treatments is from studies of women with breast cancer and, to a lesser extent, men with prostate cancer (Table 1). Several studies that have examined cognitive outcomes for older patients or that include older participants with breast cancers have noted objective and subjective cognitive impairment.24–26,32 Other studies that include these types of older patients with cancer have yielded less consistent results.33–36 Such inconsistencies may reflect true underlying differences in participant risk and reserve postulated by theories of aging. Disparate conclusions may also reflect methodologic issues, including small samples of older patients (range, 13 to 50 patients), variations in the type of control group, or differences in the timing of assessment (eg, patients treated in midlife and evaluated at older ages).26

Table 1.

Cognitive Effects of Cancer Treatment in Selected Studies That Include Older Patients With Breast and Prostate Cancer

| Reference | Participants | Assessment Schedule | Cognitive Domains Assessed | Results |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Breast cancer | ||||

| Hurria et al24 | Patients older than age 65 years (mean, 71 years; n = 31) | Pre- and postchemotherapy | Attention; verbal and visual memory; and verbal, spatial, psychomotor, and executive function | Declines in visual memory and spatial, attention, and psychomotor function |

| Hurria et al25 | Patients age 65 years or older (mean, 70 years; n = 50) | Before and after 6 months of chemotherapy | Self-reported learning, working memory, and remote learning | Approximately 50% perceived memory decline; perceived decline related to pretreatment memory |

| Yamada et al26 | Survivors age 65 years or older (n = 30); age-, education-, and IQ-matched controls (n = 30) | Tested ≥ 10 years post- treatment | IQ, attention, language, visuospatial reasoning, memory, executive function | Survivors had significantly lower divided attention, working memory, and executive function than controls |

| Ahles et al17 | Patients exposed to chemotherapy (mean age, 51.7 years; n = 60); patients without chemotherapy (mean age, 56.6 years; n = 72); controls (mean age, 52.9 years; n = 45) | Tested pretreatment and 1, 6, and 18 months post-treatment | Verbal ability, verbal and visual memory, working memory, processing speed, sorting, distractibility, reaction time | Age (older than 60 years) and pretreatment cognitive reserve related to post-treatment processing speed decline in chemotherapy-exposed patients |

| Schilder et al27 | Patients receiving tamoxifen (mean age, 68.7 years; n = 80) v exemestane (mean age, 68.3 years; n = 99) and controls (mean age, 66.2 years; n = 120) | Tested prior to start and after 1 year of therapy | Verbal memory, visual memory, processing speed, executive function, manual motor speed, verbal fluency, reaction speed, working memory | Tamoxifen associated with lower verbal memory and executive function; women age 65 years or older receiving tamoxifen performed lowest on verbal memory and processing speed |

| Koppelmans et al28 | CMF chemotherapy (mean age, 64.1 years; n = 196) v noncancer group (mean age, 57.9 years; n = 1,509) | Tested at an average of 21 years post-treatment | Processing speed, verbal learning, memory, word fluency, executive function, visuospatial ability, psychomotor speed | Patients performed worse than controls on learning, memory, processing speed, inhibition, and psychomotor speed |

| Hurria et al29 | Patients receiving aromatase inhibitors (mean age, 72.4 years; n = 35) and age-matched controls (n = 35) | Tested pretherapy and after 6 months | Verbal function, learning and memory, visual memory, spatial, psychomotor, attention, and executive function | No significant cognitive decline but PET scan showed brain metabolic changes at 6 months |

| Prostate cancer | ||||

| Alibhai et al30 | Patients receiving ADT (mean age, 69.3 years; n = 77) matched to non-ADT cancer controls (n = 82) and noncancer controls (n = 82) by age and education | Tested before and at 6 and 12 months after ADT | Attention, processing speed, verbal memory, verbal fluency, cognitive flexibility, immediate memory, working memory, visuospatial ability | No patient-control differences at 6 months, but significantly less improvement in ADT patients for some tests within attention, visuospatial, and executive domains at 12 months |

| Jim et al31 | Patients receiving ADT (mean age, 69 years; n = 48) matched to noncancer controls (n = 48) by age and education | Tested at one time point during treatment | Verbal memory, verbal fluency, visual memory, visuospatial function, executive function | Patients did not differ from controls on any specific domain but had a higher rate of overall cognitive impairment |

Abbreviations: ADT, androgen deprivation therapy; CMF, cyclophosphamide, methotrexate, and fluorouracil; PET, positron emission tomography.

Another cancer commonly seen in older patients—prostate cancer—has also been a focus of investigation. Several studies have examined whether cognitive impairment occurs with administration of androgen deprivation therapy (ADT) to patients with nonmetastatic prostate cancer. Evidence on this issue is mixed (Table 1). For example, a cross-sectional study found higher rates of cognitive impairment in patients with prostate cancer receiving ADT for an average of 23 months compared with age- and education-matched noncancer controls.31 In contrast, a longitudinal study in which patients with prostate cancer who were starting ADT were assessed at baseline and observed for 12 months found no consistent evidence of ADT-related cognitive impairment compared with noncancer controls and patients with prostate cancer who did not receive ADT.30 A recent review highlighted these inconsistencies and noted that most studies in this area are characterized by important design weaknesses (eg, small sample sizes and suboptimal control groups) that limit inference.37 However, focusing only on well-controlled studies, it does appear that visual-spatial memory may be impaired with ADT.37,38

Overall, when cognitive impairment is noted in samples with pretreatment or nonexposed cancer or population controls, the most commonly affected domains include verbal working memory, visual memory and visual-spatial domains, executive function, and/or processing speed (Table 1).11,39–44 These cognitive impairments have been observed after considering surgery type, anxiety, depression, and/or fatigue, and they persist for variable periods of time from 139 to as many as 10 to 20 years post-treatment.28,45,46 Beyond these fairly consistent associations, the link between cancer systemic therapy and cognitive impairment is further supported by observed dose-response relationships, with greater exposure in terms of dose or treatment duration leading to higher rates of cognitive impairment.12

As summarized in Table 2, impairment in one or more domains of cognitive function could have important effects on the daily lives of older patients and survivors, including difficulty tracking medications and following medical advice, difficulty coordinating care across multiple providers, difficulty with tasks such as bill payment and meal preparation, need for additional time to perform these types of tasks, and social isolation to conceal deficits.12 Thus, it will be important to increase our research on cancer and cognition in the older population, because this is the group most likely to be faced with the simultaneous risks of cancer and the adverse effects of treatment, along with other diseases related to brain aging.5,47–49 Expansion of studies of cognition from breast and prostate cancer to other common cancers in older populations (eg, colorectal cancer) could also further support clinical care of this age group.

Table 2.

Domains of Cognitive Function Affected by Cancer Systemic Therapy and Implications for Function in Older Patients With Cancer

| Domain | Brain Region | Impact on Function |

|---|---|---|

| Working memory | Bilateral prefrontal and parietal regions | Ability to organize activities, arrive on time, make plans and decisions, correct errors, conceptualize problems, react with appropriate speed |

| Executive function | Ipsilateral dorsal lateral prefrontal cortex | |

| Psychomotor speed | Distributed frontal subcortical network; bilateral frontal and pyramidal and extrapyramidal motor systems | |

| Attention, concentration | Distributed frontal subcortical network | Ability to pay attention to new information and process the information |

| Language and verbal memory | Left hemisphere | Ability to fluently bring words to mind |

| Learning and episodic memory | Medial temporal lobes and prefrontal cortex | Ability to learn or recall new information |

| Visual memory | Right hemisphere | Ability to integrate visual information with motor activities |

| Visuospatial | Right parietal and bilateral frontal regions |

Studies of Structural and Functional Brain Neuroimaging

To the extent that cancer treatments may accelerate or mimic the effects of aging to produce cognitive impairment in domains that impact daily function, one would expect some overlap in the brain structures affected by aging and by cancer treatments. Overall, this has been the case, with similar brain structural alterations seen in aging and cancer-related cognitive impairment, including decreases in overall brain volume, gray matter, white matter connectivity, and hippocampal volume.10,28,50–53 For instance, imaging studies have demonstrated that total gray matter volume reliably decreases with advancing age, with regional changes exhibited mainly in the frontal cortex and in regions around the central sulcus, including the hippocampus.54 Lower hippocampal volume is related to memory functioning and has been observed in patients with breast cancer after treatment.55

Global white matter also diminishes with increasing age.54,56 Reduction in volume of frontal brain structures and changes in the integrity of white matter tracts have been reported after breast cancer chemotherapy as have alterations in brain activation on functional neuroimaging.50,57–62

Alterations in brain function have also been observed among patients with breast cancer by using functional MRI (fMRI) and functional positron emission tomography.51,63,64 Interestingly, several studies have found patterns of over activation in patients with breast cancer compared with controls both before and after adjuvant chemotherapy.10,57,65,66 These results have been interpreted as evidence of compensatory activation (ie, recruitment of alternate brain structures to maintain performance on neuropsychological testing) and may explain why some patients report cognitive problems but score within the normal range on neuropsychological testing. The findings also suggest that abnormal patterns of activation exist before adjuvant therapy in some patients and may be a predictor of post-treatment cognitive problems. However, most of these latter imaging studies have been among patients younger than age 65 years with breast cancer.

Although there are limited studies in older patients with prostate cancer, one study used fMRI and neuropsychological testing to compare men who received ADT with those who did not.67 They noted that after 6 months of treatment, there were no differences in average cognitive function, but men receiving ADT showed impaired brain activation and abnormal functional brain connectivity on fMRI.67

It will be important to investigate these brain structural links between aging, cancer therapy, and cognitive impairment related to systemic therapy in larger samples of older patients with cancer, especially in longitudinal settings with a healthy aging control population. At present, the results are consistent with those postulated by theories of aging. Taken together with the correlated neuropsychological testing and neuroimaging results, the body of evidence suggests that the observed cognitive effects of cancer therapy are not an artifact. However, it appears that only a susceptible subgroup of older patients experience cognitive impairment after systemic cancer therapy.10,11,17 The next section reviews what is known about factors that might identify those older patients at greatest risk for cognitive impairment after systemic therapy.

RISK FACTORS FOR COGNITIVE IMPAIRMENT FOLLOWING CANCER SYSTEMIC THERAPY

The precise biologic mechanisms and pathways underpinning cognitive impairment after cancer and/or its treatments remain uncertain; therefore, it is difficult to validate risk markers. Common candidate pathways and risk factors are consistent with theories of aging and include those that affect accumulation of damage, repair of damage, and baseline system redundancy. Accordingly, researchers have investigated changes in hormonal milieu, inflammation, oxidative stress, DNA damage and compromised DNA repair, decreased brain blood flow or disruption of the blood-brain barrier, genetic susceptibility, direct neurotoxicity or damage to specific brain regions, decreased telomere length, and cell senescence (Table 3).

Table 3.

Risk Factors for Cognitive Impairment Following Cancer Systemic Therapy

| Category | Mechanism | Source |

|---|---|---|

| Hormonal milieu | Bender et al68 Ciocca and Roig69 Shilling et al70 Deroo and Korach71 |

|

| Tamoxifen | Effects on brain estrogen receptors in frontal lobe and hippocampus; maintaining telomere length | Schilder et al27 Castellon et al72 Jenkins et al73 Bender et al74 Collins et al75 Schilder et al76 Lee et al77 |

| Aromatase inhibitors | Decreased circulating estrogen | Schilder et al27 Jenkins et al73 Bender et al74 |

| Androgen deprivation | Reduced testosterone | Moffat et al78 Thilers et al79 |

| Inflammation/cytokines and cytokine regulation | Modulation of neuronal and glial cell functioning, neural repair, and the metabolism of neurotransmitters important for normal cognitive function | Wilson et al80 McAfoose et al81 Ganz et al82 |

| Oxidative stress; DNA damage and/or repair | Treatment-induced DNA damage targeted to tumor and brain cell death; decreased brain plasticity and repair | Conroy et al50 Migliore et al83 Migliore et al84 Ganz et al85 |

| Genetic susceptibility | Ahles et al48 Saykin et al86 McAllister et al87 Egan et al88 Hariri et al89 Pezawas et al90 |

|

| ApoE | Uptake, transport, and distribution of lipids; role in neuronal repair and plasticity after injury | Ahles et al48 |

| COMT | Metabolism of catecholamines; effects on neurotransmitter levels | Small et al44 Lindenberger et al91 |

| BDNF | Neuronal repair and survival, dendritic and axonal growth, signal potentiation | Egan et al88 Hariri et al89 Pezawas et al90 |

| TNF-α-308 promoter SNP | Inflammation | Ganz et al82 |

| Vascular integrity | Variation in blood-brain transporters (eg, multidrug resistance 1 [MDR1] gene coding for protein P-glycoprotein); effects of diabetes or vascular disease; direct toxicity to brain cells and/or cell death and reduced cell division | Ahles et al48 |

| Telomere length | Accelerating aging process and/or direct apoptotic effect on neuronal mitotic cells | Maccormick92 |

| Cellular senescence | Inflammation and damage | Ahles et al10 |

| Stem cells | Neurotoxicity to progenitor cells | Seigers et al93 Dietrich et al94 |

Hormonal levels decrease over the life span. In noncancer populations, hormone replacement therapy seems to improve cognition in postmenopausal women.95 hormone replacement therapy also appears to decrease the risk of developing Alzheimer's disease by up to 29%,96–98 although this result is not universally noted.99–101 In patients with cancer, hormonal therapies have been implicated in cognitive impairment after treatment for breast cancer.27,72–76 However, effects are not universal and may not be observed with all hormonal therapies. For instance, a recent clinical trial reported cognitive declines in verbal memory and executive function among women treated with tamoxifen but not exemestane.27 This result is biologically plausible because estrogen receptors, the target of tamoxifen and other drugs in its class, are found in large numbers in the frontal lobe and hippocampus68–71; these same areas have been noted to have abnormalities on imaging studies.52,102 One intriguing result of the trial comparing hormonal therapies was a preliminary result that tamoxifen had larger effect sizes and affected a greater number of cognitive domains in women age 65 years or older compared with women younger than age 65 years.27

In contrast, aromatase inhibitors like exemestane block conversion of androgens into estrogens, and studies of their effect on cognition have been inconsistent.27,73,74 Hurria et al29 recently compared cognitive performance of older patients with breast cancer treated with an aromatase inhibitor with matched healthy controls in a longitudinal study and found no evidence for cognitive decline on the basis of neuropsychological testing. However, positron emission tomography imaging revealed metabolic changes, primarily in medial temporal lobes in patients compared with controls.

As noted previously for prostate cancer, the main finding from a recent review of studies of men treated with ADT is that spatial memory may be especially affected.37 The putative mechanism for this and other adverse cognitive effects is the decline in testosterone levels produced by ADT. This hypothesis is supported by research showing that naturally occurring reductions in testosterone among healthy men are also associated with cognitive impairment, especially in domains involving visual and spatial abilities.78,79 The link between nonverbal abilities and testosterone is further supported by research on sex differences in cognition, which has consistently demonstrated differences in visuospatial ability between the sexes favoring males.103

In terms of other risk factors that affect the ability of various systems to repair themselves, Conroy et al50 recently conducted an innovative study with breast cancer survivors and matched noncancer controls. The sample population ranged in age from 41 to 79 years old; the patients with cancer were 3 to 10 years post-treatment. They found that oxidative DNA damage was higher in patients than controls and that DNA damage was correlated with lower scores on neuropsychological tests of cognitive function and less frontal gray matter density and brain activation on fMRI. Although only small numbers of patients were assessed (n = 48), the result is interesting because oxidative DNA damage and diminished DNA repair mechanisms are also markers of senescence104 and are seen with mild cognitive impairment in noncancer settings.83,84 Hormonal therapies may also be associated with increased DNA damage.105

Although it is widely held that most systemic chemotherapy agents do not cross the blood-brain barrier in significant doses, data from animal studies suggest that small doses of common chemotherapy agents can cause cell death and reduced cell division in brain structures crucial for cognition, even at doses below those needed to effectively kill cancer cells.48 In humans, the amount of systemic agents that enters the brain may be modified by genetic variability in blood-brain barrier transporters.

Other genetic influences may also modulate the influence of exposure to cancer treatment via effects on baseline system redundancy.48,87 Polymorphisms of the apolipoprotein E (ApoE) and catechol-O-methyltransferase (COMT) genes have been studied for associations with cognitive impairment after cancer treatment,44,46 and numerous other candidate genes may play a role (eg, brain-derived neurotrophic factor [BDNF] and the tumor necrosis factor α 308 [TNF-α-308] promoter single nucleotide polymorphism).48,82,87–91

Ahles et al46 noted that 10- to 20-year breast cancer survivors who received chemotherapy and were ApoE ε4–positive had greater impairment in the visual-spatial and visual memory domains compared with ε4-negative survivors receiving this treatment (average age, 56 years), although others have not noted this provocative relationship.53

COMT plays an important role in prefrontal dopamine regulation in the frontal lobes and has been shown to be associated with executive function in normal controls. In a study of cancer and cognition by Small et al,44 patients with breast cancer treated with chemotherapy who were COMT-valine carriers performed worse on measures of attention compared with COMT-methionine homozygotes, although the average age of these women was well below 65 years. Of note, in general populations, Lindenberger et al91 have found an age interaction with the COMT gene.

As the validity of personalized medicine becomes more established, understanding the genetic and other risk profiles of older patients most vulnerable to cognitive decline could be useful in clinical decision making about systemic therapy and risk of cognitive impairment and in identifying survivors in greatest need of intensive surveillance over time.

SUMMARY AND PRACTICE IMPLICATIONS

From the preceding review, it is clear that there is a consistent body of evidence from controlled studies using neuropsychological testing and neuroimaging that supports the existence of cognitive impairment among some older patients with cancer after receiving systemic therapy. However, it is also apparent that there is not yet sufficient evidence to develop clinically useful, validated tools for risk prediction of cognitive impairment related to specific cancer systemic therapies. Moreover, older individuals vary along a continuum of physiologic and cognitive reserve from high (ie, biologically younger than their age) to frail (biologically older than their age). Although the frail phenotype is obvious in clinical practice, the challenge remains to reliably identify those with low reserve in the absence of overt symptomatology so that treatment decisions can be tailored to physiologic rather than chronological age.

One implication for oncology practice of the current body of evidence on cognitive impairment after systemic therapy is that older patients be evaluated for frailty and reserve.106 Other articles in this issue include in-depth reviews of state-of-the-art recommendations for such assessments. Although still not fully tested for predictive validity or impact on outcomes,107 many of those assessment tools can be used during routine clinical encounters and could be of help in multidisciplinary team care.

As the field of geriatric oncology moves forward, it will be important to ensure that recommended batteries of tests and biomarkers have high predicative validity for the outcomes of interest, including cognitive impairment. The results of these assessments could then be useful as adjunct tools for identifying subgroups of older patients who are likely to be at highest risk for cognitive decline after systemic therapy.108 This information could be used together with clinical data and results of tumor multigene profiles in discussions with patients about balancing benefits and harms of systemic therapy. Consideration of the cognitive impact of systemic therapy could possibly change treatment decisions, especially when indications for systemic therapy are equivocal, because cognitive changes are among the symptoms most feared by older adults.7,8 Furthermore, clinicians need to be aware that, with the aging of the population, they will be diagnosing increasing numbers of patients with pre-existing mild cognitive impairment or dementia that may be unrelated to their cancer but can have significant implications for treatment decision making and clinical management.

Surveillance for risks for and presence of cognitive impairment is also an important component of long-term survivorship care, especially with older patients. This is especially important because the time course of impairment following cancer systemic therapy is variable, improving in some patients over time and persisting for up to 20 years in others.12,45 The National Comprehensive Cancer Network recently added this dimension to its recommendations for survivorship care.109 When data become available on effective interventions, such as cognitive training, exercise, and other approaches, these could be integrated into active treatment and survivorship care to prevent or treat cognitive impairment in older patients.110–116 Finally, future therapeutic trials of systemic agents could include intermediate end points of relevance to the older age group, including cognitive function and trajectories of frailty.117–119

Given the demographic imperative of a rapidly growing older population, increasing cancer incidence with advancing age, and the increasingly chronic nature of the most common cancers, novel research in older patients with cancer and cancer survivors will be critical for developing practice guidelines aimed at minimizing cognitive impairment while maximizing survival outcomes of older patients. Clinicians and their older patients can advance the field by actively encouraging and participating in research designed to improve the care and outcomes of older patients with cancer.

Acknowledgment

We acknowledge the contributions of the Thinking and Living with Cancer study team to the intellectual or material content presented in this article: Tim Ahles, PhD; Chie Akiba; Mallory Cases; Jonathan D. Clapp; Elana Cooke; Neelima Denduluri, MD; Asma Dilawari, MD; Julia Fallon; Maria Farberov; Leigh Anne Faul, PhD; Brandon Gavett, PhD; Maria Gomez; Alyssa Hoekstra; Darlene Howard, PhD; Arti Hurria, MD; Claudine Isaacs, MD; Paul B. Jacobsen, PhD; Patricia Johnson; Gheorghe Luta, PhD; Jeanne S. Mandelblatt, MD; Trina McClendon; Meghan McGuckin; Olivia O'Brian; Renee Ornduff; Rupal Ramani; Andrew Saykin, PhD; Rebecca A. Silliman, MD, PhD; Robert A. Stern, PhD; Tiffany A. Traina, MD; R. Scott Turner, MD; John W. VanMeter, PhD; and Laura Zavala. We also acknowledge the assistance of Adrienne Ryans in preparing the manuscript.

Footnotes

Written on behalf of the Thinking and Living with Cancer Study Group.

Supported by Grants No. U10CA 84131, R01CA127617, K05CA096940, and P30CA51008 (J.S.M.); RO1 CA172119 and U54 CA137788 (T.A.); and R01CA132803 (P.B.J.) from the National Cancer Institute.

Authors' disclosures of potential conflicts of interest and author contributions are found at the end of this article.

AUTHORS' DISCLOSURES OF POTENTIAL CONFLICTS OF INTEREST

The author(s) indicated no potential conflicts of interest.

AUTHOR CONTRIBUTIONS

Conception and design: Jeanne S. Mandelblatt, Paul B. Jacobsen

Collection and assembly of data: Jeanne S. Mandelblatt

Data analysis and interpretation: Jeanne S. Mandelblatt

Manuscript writing: All authors

Final approval of manuscript: All authors

REFERENCES

- 1.Surveillance, Epidemiology, and End Results (SEER) Program. SEER*Stat Database: Mortality-All COD, Aggregated With State, Total U.S. (1969-2009) <Katrina/Rita Population Adjustment>, National Cancer Institute, Division of Cancer Control and Population Sciences, Surveillance Research Program, Surveillance Systems Branch, released April 2013. Underlying mortality data provided by NCHS ( www.cdc.gov/nchs)

- 2.United States Department of Commerce, Economics and Statistics Administration, Census Bureau. https://www.census.gov/prod/2014pubs/p25-1141.pdf.

- 3.Holmes HM, Albrand G. Organizing the geriatrician/oncologist partnership: One size fits all? Practical solutions. Interdiscip Top Gerontol. 2013;38:132–138. doi: 10.1159/000343615. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Hurria A, Mohile SG, Dale W. Research priorities in geriatric oncology: Addressing the needs of an aging population. J Natl Compr Canc Netw. 2012;10:286–288. doi: 10.6004/jnccn.2012.0025. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Hurria A, Naylor M, Cohen HJ. Improving the quality of cancer care in an aging population: Recommendations from an IOM report. JAMA. 2013;310:1795–1796. doi: 10.1001/jama.2013.280416. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Kalsi T, Payne S, Brodie H, et al. Are the UK oncology trainees adequately informed about the needs of older people with cancer? Br J Cancer. 2013;108:1936–1941. doi: 10.1038/bjc.2013.204. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Friedenberg RM. Dementia: One of the greatest fears of aging. Radiology. 2003;229:632–635. doi: 10.1148/radiol.2293031280. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Burdette-Radoux S, Muss HB. Adjuvant chemotherapy in the elderly: Whom to treat, what regimen? Oncologist. 2006;11:234–242. doi: 10.1634/theoncologist.11-3-234. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Silberfarb PM. Chemotherapy and cognitive defects in cancer patients. Annu Rev Med. 1983;34:35–46. doi: 10.1146/annurev.me.34.020183.000343. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Ahles TA, Root JC, Ryan EL. Cancer- and cancer treatment-associated cognitive change: An update on the state of the science. J Clin Oncol. 2012;30:3675–3686. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2012.43.0116. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Jim HS, Phillips KM, Chait S, et al. Meta-analysis of cognitive functioning in breast cancer survivors previously treated with standard-dose chemotherapy. J Clin Oncol. 2012;30:3578–3587. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2011.39.5640. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Hodgson KD, Hutchinson AD, Wilson CJ, et al. A meta-analysis of the effects of chemotherapy on cognition in patients with cancer. Cancer Treat Rev. 2013;39:297–304. doi: 10.1016/j.ctrv.2012.11.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Fried LP, Tangen CM, Walston J, et al. Frailty in older adults: Evidence for a phenotype. J Gerontol A Biol Sci Med Sci. 2001;56:M146–M156. doi: 10.1093/gerona/56.3.m146. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Sarkisian CA, Gruenewald TL, John Boscardin W, et al. Preliminary evidence for subdimensions of geriatric frailty: The MacArthur study of successful aging. J Am Geriatr Soc. 2008;56:2292–2297. doi: 10.1111/j.1532-5415.2008.02041.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Avila-Funes JA, Amieva H, Barberger-Gateau P, et al. Cognitive impairment improves the predictive validity of the phenotype of frailty for adverse health outcomes: The three-city study. J Am Geriatr Soc. 2009;57:453–461. doi: 10.1111/j.1532-5415.2008.02136.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Sternberg SA, Wershof Schwartz A, Karunananthan S, et al. The identification of frailty: A systematic literature review. J Am Geriatr Soc. 2011;59:2129–2138. doi: 10.1111/j.1532-5415.2011.03597.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Ahles TA, Saykin AJ, McDonald BC, et al. Longitudinal assessment of cognitive changes associated with adjuvant treatment for breast cancer: Impact of age and cognitive reserve. J Clin Oncol. 2010;28:4434–4440. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2009.27.0827. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Haring B, Leng X, Robinson J, et al. Cardiovascular disease and cognitive decline in postmenopausal women: Results from the Women's Health Initiative Memory Study. J Am Heart Assoc. 2013;2:e000369. doi: 10.1161/JAHA.113.000369. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Shai I, Schulze MB, Manson JE, et al. A prospective study of soluble tumor necrosis factor-alpha receptor II (sTNF-RII) and risk of coronary heart disease among women with type 2 diabetes. Diabetes Care. 2005;28:1376–1382. doi: 10.2337/diacare.28.6.1376. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Campisi J. Aging, cellular senescence, and cancer. Annu Rev Physiol. 2013;75:685–705. doi: 10.1146/annurev-physiol-030212-183653. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Velarde MC, Demaria M, Campisi J. Senescent cells and their secretory phenotype as targets for cancer therapy. In: Extermann M, editor. Cancer and Aging: From Bench to Clinics. Basel, Switzerland: Karger; 2013. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Kirkland JL. Translating advances from the basic biology of aging into clinical application. Exp Gerontol. 2013;48:1–5. doi: 10.1016/j.exger.2012.11.014. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Gavrilov LA, Gavrilova NS. The reliability theory of aging and longevity. J Theor Biol. 2001;213:527–545. doi: 10.1006/jtbi.2001.2430. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Hurria A, Rosen C, Hudis C, et al. Cognitive function of older patients receiving adjuvant chemotherapy for breast cancer: A pilot prospective longitudinal study. J Am Geriatr Soc. 2006;54:925–931. doi: 10.1111/j.1532-5415.2006.00732.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Hurria A, Goldfarb S, Rosen C, et al. Effect of adjuvant breast cancer chemotherapy on cognitive function from the older patient's perspective. Breast Cancer Res Treat. 2006;98:343–348. doi: 10.1007/s10549-006-9171-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Yamada TH, Denburg NL, Beglinger LJ, et al. Neuropsychological outcomes of older breast cancer survivors: Cognitive features ten or more years after chemotherapy. J Neuropsychiatry Clin Neurosci. 2010;22:48–54. doi: 10.1176/appi.neuropsych.22.1.48. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Schilder CM, Seynaeve C, Beex LV, et al. Effects of tamoxifen and exemestane on cognitive functioning of postmenopausal patients with breast cancer: Results from the neuropsychological side study of the tamoxifen and exemestane adjuvant multinational trial. J Clin Oncol. 2010;28:1294–1300. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2008.21.3553. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Koppelmans V, Breteler MM, Boogerd W, et al. Neuropsychological performance in survivors of breast cancer more than 20 years after adjuvant chemotherapy. J Clin Oncol. 2012;30:1080–1086. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2011.37.0189. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Hurria A, Patel SK, Mortimer J, et al. The effect of aromatase inhibition on the cognitive function of older patients with breast cancer. Clin Breast Cancer. 2014;14:132–140. doi: 10.1016/j.clbc.2013.10.010. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Alibhai SM, Breunis H, Timilshina N, et al. Impact of androgen-deprivation therapy on cognitive function in men with nonmetastatic prostate cancer. J Clin Oncol. 2010;28:5030–5037. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2010.30.8742. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Jim HS, Small BJ, Patterson S, et al. Cognitive impairment in men treated with luteinizing hormone-releasing hormone agonists for prostate cancer: A controlled comparison. Support Care Cancer. 2010;18:21–27. doi: 10.1007/s00520-009-0625-3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Hurria A, Lachs M. Is cognitive dysfunction a complication of adjuvant chemotherapy in the older patient with breast cancer? Breast Cancer Res Treat. 2007;103:259–268. doi: 10.1007/s10549-006-9383-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Hutchinson AD, Hosking JR, Kichenadasse G, et al. Objective and subjective cognitive impairment following chemotherapy for cancer: A systematic review. Cancer Treat Rev. 2012;38:926–934. doi: 10.1016/j.ctrv.2012.05.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Vardy J, Rourke S, Tannock IF. Evaluation of cognitive function associated with chemotherapy: A review of published studies and recommendations for future research. J Clin Oncol. 2007;25:2455–2463. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2006.08.1604. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Vardy J, Tannock I. Cognitive function after chemotherapy in adults with solid tumours. Crit Rev Oncol Hematol. 2007;63:183–202. doi: 10.1016/j.critrevonc.2007.06.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Wefel JS, Lenzi R, Theriault RL, et al. The cognitive sequelae of standard-dose adjuvant chemotherapy in women with breast carcinoma: Results of a prospective, randomized, longitudinal trial. Cancer. 2004;100:2292–2299. doi: 10.1002/cncr.20272. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Jamadar RJ, Winters MJ, Maki PM. Cognitive changes associated with ADT: A review of the literature. Asian J Androl. 2012;14:232–238. doi: 10.1038/aja.2011.107. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Nelson CJ, Lee JS, Gamboa MC, et al. Cognitive effects of hormone therapy in men with prostate cancer: A review. Cancer. 2008;113:1097–1106. doi: 10.1002/cncr.23658. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Bender CM. Chemotherapy may have small to moderate negative effects on cognitive functioning. Cancer Treat Rev. 2006;32:316–319. doi: 10.1016/j.ctrv.2006.02.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Jansen SJ, Otten W, Baas-Thijssen MC, et al. Explaining differences in attitude toward adjuvant chemotherapy between experienced and inexperienced breast cancer patients. J Clin Oncol. 2005;23:6623–6630. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2005.07.171. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Anderson-Hanley C, Sherman ML, Riggs R, et al. Neuropsychological effects of treatments for adults with cancer: A meta-analysis and review of the literature. J Int Neuropsychol Soc. 2003;9:967–982. doi: 10.1017/S1355617703970019. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Correa DD, Ahles TA. Neurocognitive changes in cancer survivors. Cancer J. 2008;14:396–400. doi: 10.1097/PPO.0b013e31818d8769. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Stewart A, Bielajew C, Collins B, et al. A meta-analysis of the neuropsychological effects of adjuvant chemotherapy treatment in women treated for breast cancer. Clin Neuropsychol. 2006;20:76–89. doi: 10.1080/138540491005875. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Small BJ, Rawson KS, Walsh E, et al. Catechol-O-methyltransferase genotype modulates cancer treatment-related cognitive deficits in breast cancer survivors. Cancer. 2011;117:1369–1376. doi: 10.1002/cncr.25685. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Ahles TA, Saykin AJ, Furstenberg CT, et al. Neuropsychologic impact of standard-dose systemic chemotherapy in long-term survivors of breast cancer and lymphoma. J Clin Oncol. 2002;20:485–493. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2002.20.2.485. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Ahles TA, Saykin AJ, Noll WW, et al. The relationship of APOE genotype to neuropsychological performance in long-term cancer survivors treated with standard dose chemotherapy. Psychooncology. 2003;12:612–619. doi: 10.1002/pon.742. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Mandelblatt JS, Hurria A, McDonald BC, et al. Cognitive effects of cancer and its treatments at the intersection of aging: What do we know; what do we need to know? Semin Oncol. 2013;40:709–725. doi: 10.1053/j.seminoncol.2013.09.006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Ahles TA, Saykin AJ. Candidate mechanisms for chemotherapy-induced cognitive changes. Nat Rev Cancer. 2007;7:192–201. doi: 10.1038/nrc2073. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Institute of Medicine. Washington, DC: The National Academies Press; 2013. Delivering High-Quality Cancer Care: Charting a New Course for a System in Crisis. http://www.iom.edu/Reports/2013/Delivering-High-Quality-Cancer-Care-Charting-a-New-Course-for-a-System-in-Crisis.aspx. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Conroy SK, McDonald BC, Smith DJ, et al. Alterations in brain structure and function in breast cancer survivors: Effect of post-chemotherapy interval and relation to oxidative DNA damage. Breast Cancer Res Treat. 2013;137:493–502. doi: 10.1007/s10549-012-2385-x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Silverman DH, Dy CJ, Castellon SA, et al. Altered frontocortical, cerebellar, and basal ganglia activity in adjuvant-treated breast cancer survivors 5-10 years after chemotherapy. Breast Cancer Res Treat. 2007;103:303–311. doi: 10.1007/s10549-006-9380-z. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.McDonald BC, Conroy SK, Ahles TA, et al. Gray matter reduction associated with systemic chemotherapy for breast cancer: A prospective MRI study. Breast Cancer Res Treat. 2010;123:819–828. doi: 10.1007/s10549-010-1088-4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.McDonald BC, Conroy SK, Smith DJ, et al. Frontal gray matter reduction after breast cancer chemotherapy and association with executive symptoms: A replication and extension study. Brain Behav Immun. 2013;30:S117–S125. doi: 10.1016/j.bbi.2012.05.007. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Peelle JE, Cusack R, Henson RN. Adjusting for global effects in voxel-based morphometry: Gray matter decline in normal aging. Neuroimage. 2012;60:1503–1516. doi: 10.1016/j.neuroimage.2011.12.086. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Bergouignan L, Lefranc JP, Chupin M, et al. Breast cancer affects both the hippocampus volume and the episodic autobiographical memory retrieval. PLoS One. 2011;6:e25349. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0025349. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Gunning-Dixon FM, Brickman AM, Cheng JC, et al. Aging of cerebral white matter: A review of MRI findings. Int J Geriatr Psychiatry. 2009;24:109–117. doi: 10.1002/gps.2087. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.McDonald BC, Conroy SK, Ahles TA, et al. Alterations in brain activation during working memory processing associated with breast cancer and treatment: A prospective functional magnetic resonance imaging study. J Clin Oncol. 2012;30:2500–2508. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2011.38.5674. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Hosseini SM, Koovakkattu D, Kesler SR. Altered small-world properties of gray matter networks in breast cancer. BMC Neurol. 2012;12:28. doi: 10.1186/1471-2377-12-28. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.de Ruiter MB, Reneman L, Boogerd W, et al. Late effects of high-dose adjuvant chemotherapy on white and gray matter in breast cancer survivors: Converging results from multimodal magnetic resonance imaging. Hum Brain Mapp. 2012;33:2971–2983. doi: 10.1002/hbm.21422. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Deprez S, Billiet T, Sunaert S, et al. Diffusion tensor MRI of chemotherapy-induced cognitive impairment in non-CNS cancer patients: A review. Brain Imaging Behav. 2013;7:409–435. doi: 10.1007/s11682-012-9220-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Koppelmans V, de Groot M, de Ruiter MB, et al. Global and focal white matter integrity in breast cancer survivors 20 years after adjuvant chemotherapy. Hum Brain Mapp. 2012;35:889–899. doi: 10.1002/hbm.22221. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Koppelmans V, de Ruiter MB, van der Lijn F, et al. Global and focal brain volume in long-term breast cancer survivors exposed to adjuvant chemotherapy. Breast Cancer Res Treat. 2012;132:1099–1106. doi: 10.1007/s10549-011-1888-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Pomykala KL, Ganz PA, Bower JE, et al. The association between pro-inflammatory cytokines, regional cerebral metabolism, and cognitive complaints following adjuvant chemotherapy for breast cancer. Brain Imaging Behav. 2013;7:511–523. doi: 10.1007/s11682-013-9243-2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Saykin AJ, de Ruiter MB, McDonald BC, et al. Neuroimaging biomarkers and cognitive function in non-CNS cancer and its treatment: Current status and recommendations for future research. Brain Imaging Behav. 2013;7:363–373. doi: 10.1007/s11682-013-9283-7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Cimprich B, Reuter-Lorenz P, Nelson J, et al. Prechemotherapy alterations in brain function in women with breast cancer. J Clin Exp Neuropsychol. 2010;32:324–331. doi: 10.1080/13803390903032537. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Scherling C, Collins B, Mackenzie J, et al. Pre-chemotherapy differences in visuospatial working memory in breast cancer patients compared to controls: An FMRI study. Front Hum Neurosci. 2011;5:122. doi: 10.3389/fnhum.2011.00122. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Chao HH, Uchio E, Zhang S, et al. Effects of androgen deprivation on brain function in prostate cancer patients: A prospective observational cohort analysis. BMC Cancer. 2012;12:371. doi: 10.1186/1471-2407-12-371. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Bender CM, Paraska KK, Sereika SM, et al. Cognitive function and reproductive hormones in adjuvant therapy for breast cancer: A critical review. J Pain Symptom Manage. 2001;21:407–424. doi: 10.1016/s0885-3924(01)00268-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Ciocca DR, Roig LM. Estrogen receptors in human nontarget tissues: Biological and clinical implications. Endocr Rev. 1995;16:35–62. doi: 10.1210/edrv-16-1-35. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Shilling V, Jenkins V, Fallowfield L, et al. The effects of oestrogens and anti-oestrogens on cognition. Breast. 2001;10:484–491. doi: 10.1054/brst.2001.0311. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71.Deroo BJ, Korach KS. Estrogen receptors and human disease. J Clin Invest. 2006;116:561–570. doi: 10.1172/JCI27987. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72.Castellon SA, Ganz PA, Bower JE, et al. Neurocognitive performance in breast cancer survivors exposed to adjuvant chemotherapy and tamoxifen. J Clin Exp Neuropsychol. 2004;26:955–969. doi: 10.1080/13803390490510905. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73.Jenkins VA, Ambroisine LM, Atkins L, et al. Effects of anastrozole on cognitive performance in postmenopausal women: A randomised, double-blind chemoprevention trial (IBIS II) Lancet Oncol. 2008;9:953–961. doi: 10.1016/S1470-2045(08)70207-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74.Bender CM, Sereika SM, Brufsky AM, et al. Memory impairments with adjuvant anastrozole versus tamoxifen in women with early-stage breast cancer. Menopause. 2007;14:995–998. doi: 10.1097/gme.0b013e318148b28b. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 75.Collins B, Mackenzie J, Stewart A, et al. Cognitive effects of hormonal therapy in early stage breast cancer patients: A prospective study. Psychooncology. 2009;18:811–821. doi: 10.1002/pon.1453. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 76.Schilder CM, Eggens PC, Seynaeve C, et al. Neuropsychological functioning in postmenopausal breast cancer patients treated with tamoxifen or exemestane after AC-chemotherapy: Cross-sectional findings from the neuropsychological TEAM-side study. Acta Oncol. 2009;48:76–85. doi: 10.1080/02841860802314738. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 77.Lee DC, Im JA, Kim JH, et al. Effect of long-term hormone therapy on telomere length in postmenopausal women. Yonsei Med J. 2005;46:471–479. doi: 10.3349/ymj.2005.46.4.471. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 78.Moffat SD, Zonderman AB, Metter EJ, et al. Longitudinal assessment of serum free testosterone concentration predicts memory performance and cognitive status in elderly men. J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 2002;87:5001–5007. doi: 10.1210/jc.2002-020419. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 79.Thilers PP, Macdonald SW, Herlitz A. The association between endogenous free testosterone and cognitive performance: A population-based study in 35 to 90 year-old men and women. Psychoneuroendocrinology. 2006;31:565–576. doi: 10.1016/j.psyneuen.2005.12.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 80.Wilson CJ, Finch CE, Cohen HJ. Cytokines and cognition: The case for a head-to-toe inflammatory paradigm. J Am Geriatr Soc. 2002;50:2041–2056. doi: 10.1046/j.1532-5415.2002.50619.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 81.McAfoose J, Baune BT. Evidence for a cytokine model of cognitive function. Neurosci Biobehav Rev. 2009;33:355–366. doi: 10.1016/j.neubiorev.2008.10.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 82.Ganz PA, Bower JE, Kwan L, et al. Does tumor necrosis factor-alpha (TNF-α) play a role in post-chemotherapy cerebral dysfunction? Brain Behav Immun. 2013:S99–S108. doi: 10.1016/j.bbi.2012.07.015. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 83.Migliore L, Scarpato R, Coppede F, et al. Chromosome and oxidative damage biomarkers in lymphocytes of Parkinson's disease patients. Int J Hyg Environ Health. 2001;204:61–66. doi: 10.1078/1438-4639-00074. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 84.Migliore L, Fontana I, Trippi F, et al. Oxidative DNA damage in peripheral leukocytes of mild cognitive impairment and AD patients. Neurobiol Aging. 2005;26:567–573. doi: 10.1016/j.neurobiolaging.2004.07.016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 85.Ganz PA, Castellon SA, Silverman DHS, et al. Does circulating tumor necrosis factor (TNF) play a role in post-chemotherapy cerebral dysfunction in breast cancer survivors (BCS)? J Clin Oncol. 2011;(suppl 15s):29. abstr 9008. [Google Scholar]

- 86.Saykin AJ, Ahles TA, McDonald BC. Mechanisms of chemotherapy-induced cognitive disorders: Neuropsychological, pathophysiological, and neuroimaging perspectives. Semin Clin Neuropsychiatry. 2003;8:201–216. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 87.McAllister TW, Ahles TA, Saykin AJ, et al. Cognitive effects of cytotoxic cancer chemotherapy: Predisposing risk factors and potential treatments. Curr Psychiatry Rep. 2004;6:364–371. doi: 10.1007/s11920-004-0023-y. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 88.Egan MF, Kojima M, Callicott JH, et al. The BDNF val66met polymorphism affects activity-dependent secretion of BDNF and human memory and hippocampal function. Cell. 2003;112:257–269. doi: 10.1016/s0092-8674(03)00035-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 89.Hariri AR, Goldberg TE, Mattay VS, et al. Brain-derived neurotrophic factor val66met polymorphism affects human memory-related hippocampal activity and predicts memory performance. J Neurosci. 2003;23:6690–6694. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.23-17-06690.2003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 90.Pezawas L, Verchinski BA, Mattay VS, et al. The brain-derived neurotrophic factor val66met polymorphism and variation in human cortical morphology. J Neurosci. 2004;24:10099–10102. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.2680-04.2004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 91.Lindenberger U, Nagel IE, Chicherio C, et al. Age-related decline in brain resources modulates genetic effects on cognitive functioning. Front Neurosci. 2008;2:234–244. doi: 10.3389/neuro.01.039.2008. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 92.Maccormick RE. Possible acceleration of aging by adjuvant chemotherapy: A cause of early onset frailty? Med Hypotheses. 2006;67:212–215. doi: 10.1016/j.mehy.2006.01.045. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 93.Seigers R, Fardell JE. Neurobiological basis of chemotherapy-induced cognitive impairment: A review of rodent research. Neurosci Biobehav Rev. 2011;35:729–741. doi: 10.1016/j.neubiorev.2010.09.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 94.Dietrich J, Han R, Yang Y, et al. CNS progenitor cells and oligodendrocytes are targets of chemotherapeutic agents in vitro and in vivo. J Biol. 2006;5:22. doi: 10.1186/jbiol50. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 95.Sherwin BB. Estrogen and cognitive aging in women. Neuroscience. 2006;138:1021–1026. doi: 10.1016/j.neuroscience.2005.07.051. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 96.Kawas C, Resnick S, Morrison A, et al. A prospective study of estrogen replacement therapy and the risk of developing Alzheimer's disease: The Baltimore Longitudinal Study of Aging. Neurology. 1997;48:1517–1521. doi: 10.1212/wnl.48.6.1517. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 97.Yaffe K, Sawaya G, Lieberburg I, et al. Estrogen therapy in postmenopausal women: Effects on cognitive function and dementia. JAMA. 1998;279:688–695. doi: 10.1001/jama.279.9.688. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 98.Paganini-Hill A, Henderson VW. Estrogen replacement therapy and risk of Alzheimer disease. Arch Intern Med. 1996;156:2213–2217. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 99.Henderson VW, Paganini-Hill A, Miller BL, et al. Estrogen for Alzheimer's disease in women: Randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled trial. Neurology. 2000;54:295–301. doi: 10.1212/wnl.54.2.295. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 100.Mulnard RA, Cotman CW, Kawas C, et al. Estrogen replacement therapy for treatment of mild to moderate Alzheimer disease: A randomized controlled trial—Alzheimer's Disease Cooperative Study. JAMA. 2000;283:1007–1015. doi: 10.1001/jama.283.8.1007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 101.Nickelsen T, Lufkin EG, Riggs BL, et al. Raloxifene hydrochloride, a selective estrogen receptor modulator: Safety assessment of effects on cognitive function and mood in postmenopausal women. Psychoneuroendocrinology. 1999;24:115–128. doi: 10.1016/s0306-4530(98)00041-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 102.Kesler SR, Kent JS, O'Hara R. Prefrontal cortex and executive function impairments in primary breast cancer. Arch Neurol. 2011;68:1447–1453. doi: 10.1001/archneurol.2011.245. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 103.Voyer D, Voyer S, Bryden MP. Magnitude of sex differences in spatial abilities: A meta-analysis and consideration of critical variables. Psychol Bull. 1995;117:250–270. doi: 10.1037/0033-2909.117.2.250. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 104.Campisi J, d'Adda di Fagagna F. Cellular senescence: When bad things happen to good cells. Nat Rev Mol Cell Biol. 2007;8:729–740. doi: 10.1038/nrm2233. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 105.Brown K. Is tamoxifen a genotoxic carcinogen in women? Mutagenesis. 2009;24:391–404. doi: 10.1093/mutage/gep022. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 106.Mohile S, Dale W, Hurria A. Geriatric oncology research to improve clinical care. Nat Rev Clin Oncol. 2012;9:571–578. doi: 10.1038/nrclinonc.2012.125. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 107.Lin JS, O'Connor E, Rossom RC, et al. Rockville, MD: Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality (US); 2013. Nov, Screening for Cognitive Impairment in Older Adults: An Evidence Update for the U.S. Preventive Services Task Force. Report No: 14-05198-EF-1. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 108.Aparicio T, Jouve JL, Teillet L, et al. Geriatric factors predict chemotherapy feasibility: Ancillary results of FFCD 2001-02 phase III study in first-line chemotherapy for metastatic colorectal cancer in elderly patients. J Clin Oncol. 2013;31:1464–1470. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2012.42.9894. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 109.National Comprehensive Cancer Network (NCCN) NCCN Clinical Practice Guidelines in Oncology: Survivorship Guidelines v1, 2013. www.nccn.org/surviorship.

- 110.Ferguson RJ, Ahles TA, Saykin AJ, et al. Cognitive-behavioral management of chemotherapy-related cognitive change. Psychooncology. 2007;16:772–777. doi: 10.1002/pon.1133. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 111.Kohli S, Fisher SG, Tra Y, et al. The effect of modafinil on cognitive function in breast cancer survivors. Cancer. 2009;115:2605–2616. doi: 10.1002/cncr.24287. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 112.Lundorff LE, Jønsson BH, Sjøgren P. Modafinil for attentional and psychomotor dysfunction in advanced cancer: A double-blind, randomised, cross-over trial. Palliat Med. 2009;23:731–738. doi: 10.1177/0269216309106872. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 113.Fardell JE, Vardy J, Johnston IN, et al. Chemotherapy and cognitive impairment: Treatment options. Clin Pharmacol Ther. 2011;90:366–376. doi: 10.1038/clpt.2011.112. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 114.Newhouse P, Kellar K, Aisen P, et al. Nicotine treatment of mild cognitive impairment: A 6-month double-blind pilot clinical trial. Neurology. 2012;78:91–101. doi: 10.1212/WNL.0b013e31823efcbb. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 115.Fardell JE, Vardy J, Shah JD, et al. Cognitive impairments caused by oxaliplatin and 5-fluorouracil chemotherapy are ameliorated by physical activity. Psychopharmacology (Berl) 2012;220:183–193. doi: 10.1007/s00213-011-2466-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 116.Oh B, Butow PN, Mullan BA, et al. Effect of medical Qigong on cognitive function, quality of life, and a biomarker of inflammation in cancer patients: A randomized controlled trial. Support Care Cancer. 2012;20:1235–1242. doi: 10.1007/s00520-011-1209-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 117.Muss HB, Berry DA, Cirrincione CT, et al. Adjuvant chemotherapy in older women with early-stage breast cancer. N Engl J Med. 2009;360:2055–2065. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa0810266. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 118.Ganz PA. Host factors, behaviors, and clinical trials: Opportunities and challenges. J Clin Oncol. 2012;30:2817–2819. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2012.43.6576. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 119.Scher KS, Hurria A. Under-representation of older adults in cancer registration trials: Known problem, little progress. J Clin Oncol. 2012;30:2036–2038. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2012.41.6727. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]