Abstract

Aim: The present study was performed in order to differentiate E. histolytica and E. dispar in children from Gorgan city, using a PCR method.

Background: Differential detection of two morphologically indistinguishable protozoan parasites Entamoeba histolytica and E. dispar has a great clinical and epidemiological importance because of potential invasive pathogenic E. histolytica and non-invasive parasite E. dispar.

Patients and methods: One hundred and five dysentery samples were collected from children hospitalized in Taleghani hospital in Gorgan city. The fecal specimens were examined by light microscopy (10X then 40X) to distinguish Entamoeba complex. A single round PCR amplifying partial small-subunit rRNA gene was performed on positive microscopy samples to differentiate E. histolytica/ E. dispar and E. moshkovskii from each other.

Results: Twenty-five specimens (23.8%) were positive for Enramoeba complex in direct microscopic examination. PCR using positive controls indicated E. histolytica and E. dispar in two (2/25, 8%) and three (3/25, 12%) samples, respectively.

Conclusion: There is a warrant to performing molecular diagnosis for stool examination at least in hospitalized children in order to prevent incorrect reports from laboratories and consequently mistreating by physicians.

Custom Keyword Group: Entamoeba histolytica, Entamoeba dispar, children, dysentery, PCR, Gorgan, Iran

Introduction

Amoebiasis is still mentioned as one of the main health problems in tropical and subtropical regions (1). The true prevalence of infection caused by Entamoeba histolytica is unknown for most areas of the world (2).

E. histolytica causes widespread mortality and morbidity worldwide through diarrheal disease and abscess establishment in parenchymal tissues such as liver, lung, and brain (3). In contrast, other amoebae that infect humans include E. dispar, E. moshkovskii, E. coli, E. hartmanni, and Endolimax nana, have been considered nonpathogenic (4).

E. histolytica, E. dispar, and E. moshkovskii are morphologically indistinguishable but are different biochemically and genetically. Although E. histolytica is recognized as a pathogen, the ability of the other two species to cause disease is unclear (5). It is also worthy to note that until recently the differentiation of E. histolytica from the non-pathogenic amebic species was not possible (6, 7).

The epidemiology of E. histolytica in Iran is poorly understood. Fortunately, several studies over the last decade have begun to evaluate the prevalence or incidence of E. histolytica in specific populations of Iran, these studies were utilized different molecular methods in order to differentiate the non-pathogenic E. dispar or E. moshkovskii from the pathogenic E. histolytica (8-16). In this study, we used the well-characterized diagnostic tests (single round PCR) to examine the prevalence of E. histolytica, E. dispar and E. moshkovskii infections in children with dysentery in Golestan province, Iran.

Patients and Methods

From January 2010 to September 2012, 105 dysentery samples were collected from children hospitalized in Taleghani hospital in Gorgan city, the capital of Golestan Province, located in northern Iran and south east of Caspian sea. Socio-demographic and clinical data were collected from the child’s parents and medical records.

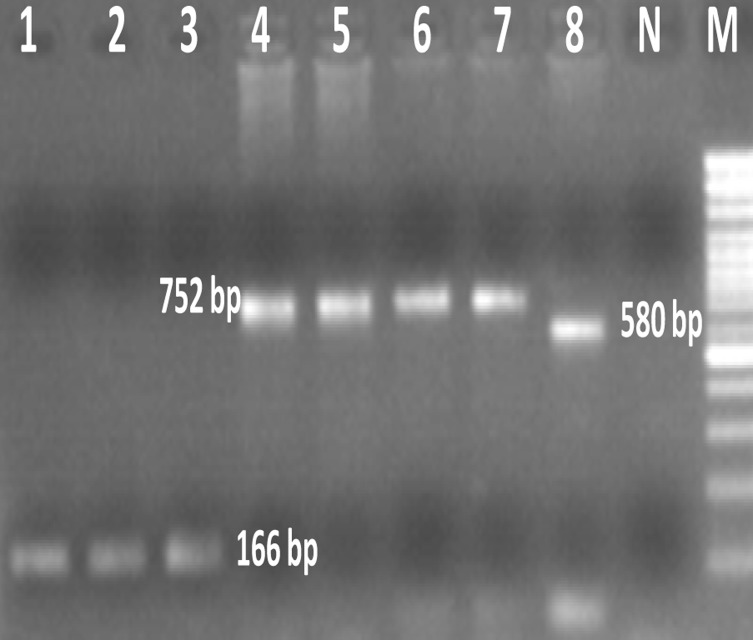

Stool specimens were screened microscopically using direct slide smear for the presence of Entamoeba spp. (13). Genomic DNA was extracted directly from stool specimens were microscopically positive by using a QIAamp® DNA Stool Kit (QIAGEN) according to the manufacturer's instructions. The extracted DNA was stored at -20°C until PCR amplification. A single–round PCR reaction and primers sets amplifying partial small-subunit rRNA gene were used as described previously (13, 17, 18). The sequence of the forward primer used was conserved in all three Entamoeba spp., but the reverse primers were specific for apiece. The expected PCR products from E. histolytica, E. dispar and E. moshkovskii were 166 bp, 752 bp, and 580 bp, respectively (17).

Amplification of each species–specific DNA fragment started with an initial denaturation at 94°C for 3 min, followed by 30 cycles of 94°C for 1 min, 58°C for 1 min, and 72°C for 1 min, with a final extension at 72°C for 7 min (14). PCR products were visualized with ethidium bromide staining after electrophoresis on 1.5% agarose gels. DNA isolated from axenically grown E. histolytica KU2, E. dispar AS 16 IR and E. moshkovskii Laredo (ATCC accession no. 300 42) (13) were used as positive controls. Medical Research Ethics Committee of Golestan University of Medical Sciences approved the study.

Figure 1.

Agarose gel electrophoresis of Entamoeba species using single–round PCR. Lanes 2-3: E. histolytica – positive isolates; Lane 5-7: E. dispar – positive isolates; Lanes 1, 4 and 8: E. histolytica , E. dispar and E. moshkovskii positive controls, respectively. N: Negative control. M: 100 bp ladder DNA size marker

Results

Out of the 105 children with dysentery, 25 (23.8%) cases were infected with E. histolytica/E. dispar/E. moshkovskii complex. After DNA extraction, the single-round PCR was carried out to differentiate the Entamoeba spp. of 25 samples that were microscopically positive. Three (12%) E. dispar and 2 (8%) E. histolytica were detected by PCR (Figure 1). Infection of E. moshkovskii was not observed in this study.

Amplification produced fragments of 166bp, 752bp and 580bp corresponding to the expected products from E. histolytica, E. dispar and E. moshkovskii, respectively.

Discussion

Infection with E. histolytica is a severe health problem in many tropical and subtropical areas of the world, especially in developing countries such as Iran (19, 20).

It is now known that most of human cases of infection with E. histolytica/E. dispar are actually E. dispar. E. dispar is non-pathogenic, and requires no treatment. Because of this, differential diagnosis of the pathogen E. histolytica from the commensally E. dispar is of the utmost importance (21).

Most epidemiological studies for E. histolytica infection were performed before the acceptance of E. histolytica/E. dispar and E. moshkovskii as distinct species. There is a clear need to perform new epidemiological studies to distinguish these three species of Entamoeba and to find true prevalence of E. histolytica species (14).

The results of this study clearly show that, microscopy is not a sensitive and reliable technique for diagnosing amebic dysentery as well as differentiation of E. histolytica from E. dispar and E. moshkovskii, because most amebic infections in this population were due to other nonpathogenic Entamoeba species (17). In a previous study in Gonbad city 16 (69.5%) from 23 microscopic positive isolates for Entamoeba species were amplified in PCR as E. dispar, none of the isolates (0%) revealed as E. histolytica and the seven isolates were not amplified in PCR. The higher prevalence of E. dispar is in concordance with our study (10). The 20 negative PCR isolates (30.43%) with both two sets of E. histolytica and E. dispar primers in this study might be due to lack of enough DNA template, PCR error or misdiagnosis with some other Entamoeba species. However, this conjecture should be confirmed by the further development of molecular diagnosis for other nonpathogenic Entamoeba species commonly found in humans, such as E. coli and E. hartmanni (17).

While the isolates were achieved typically from patients who suffered from dysentery, we found no E. histolytica among the isolates and observed no correlation between the presences of Entamoeba spp. and clinical symptoms, such as abdominal pain, diarrhea or nausea. It may be that the clinical symptoms of some patients were due to viral or bacterial pathogens not detected by the tests that had been run as in a valid study, Kermani et al. showed that Enteroaggregative Escherichia coli was the most prevalent pathogen in both persistent and acute diarrhea children admitted to a pediatric hospital (22).

In conclusion, the finding of our study emphasis to perform molecular diagnosis for stool examination at least in hospitalized children in order to prevent incorrect results from medical laboratories and consequently mistreating by physicians.

Acknowledgment

The authors would like to thank Fatemeh Malek, Zeinab Golalikhani, Hamid Mirkarimi and Akbar Mirbazel in the Taleghani hospital who helped to collect the samples. This work was financially supported by Golestan University of Medical sciences, project code: 8912240184.

References

- 1.Tanyuksel M, A P. Laboratory Diagnosis of Amebiasis. Clin Microbiol Rev. 2003;16:713–729. doi: 10.1128/CMR.16.4.713-729.2003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Stauffer W, Ravdin J. Entamoeba histolytica: An update. Curr Opin Infect Dis. 2003;16:479–485. doi: 10.1097/00001432-200310000-00016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.M I, G J, E S. Asymptomatic Intestinal Colonization by Pathogenic Entamoeba histolytica in Amebic Liver Abscess: Prevalence, Response to Therapy, and Pathogenic Potential. Clin Infect Dis. 1992;14:889–893. doi: 10.1093/clinids/14.4.889. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Blessmann J, Ik A, Pa N, Bt D, Tq V, Al Van, al e. Longitudinal study of intestinal Entamoeba histolytica infections in asymptomatic adult carriers. J. Clin. Microbiol. 2003;41:4745–4750. doi: 10.1128/JCM.41.10.4745-4750.2003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Fotedar R, Stark D, Beebe N, Marriott D, Ellis J, Harkness J. PCR detection of Entamoeba histolytica, Entamoeba dispar, and Entamoeba moshkovskii in stool samples from Sydney, Australia. J. Clin. Microbiol. 2007;45:1035–1037. doi: 10.1128/JCM.02144-06. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Ali I, Cg C, A Petri. Molecular epidemiology of amebiasis. Infect Genet Evol. 2008;8:698–707. doi: 10.1016/j.meegid.2008.05.004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Espinosa-Cantellano M, Mart{\'i}nez-Palomo A. Pathogenesis of Intestinal Amebiasis: From Molecules to Disease. Clin Microbiol Rev. 2000;13:318–331. doi: 10.1128/cmr.13.2.318-331.2000. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Hooshyar H, Rezaian M, Kazemi B, Jeddi-Tehrani M, Solaymani-Mohammadi S. The distribution of Entamoeba histolytica and Entamoeba dispar in northern, central, and southern Iran. Parasitol Res. 2004;94:96–100. doi: 10.1007/s00436-004-1175-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Solaymani-Mohammadi S, M R, Z B, A R, R M, A P, al e. Comparison of a Stool Antigen Detection Kit and PCR for Diagnosis of Entamoeba histolytica and Entamoeba dispar Infections in Asymptomatic Cyst Passers in Iran. J. Clin. Microbiol. 2006;44:2258–2261. doi: 10.1128/JCM.00530-06. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.E N, A H, M A, F M, M R, M Z. Prevalence of Entamoeba histolytica and Entamoeba dispar in Gonbad city, Iran. Iran J Parasitol. 2007;2:48–52. [Google Scholar]

- 11.E N, A H, B K, M R, A A, M Z. High genetic diversity among Iranian Entamoeba dispar isolates based on the noncoding short tandem repeat locus D-A. Acta Trop. 2009;111:133–136. doi: 10.1016/j.actatropica.2009.03.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.E N, Z N, N S, M R, H D, A H. Characterization of Entamoeba histolytica and Entamoeba dispar in fresh stool by PCR. Gastroenterol Hepatol Bed Bench. 2010;3:37–41. [Google Scholar]

- 13.E N, Z N, N S, M R, H D, M Z, B K, A H. Discrimination of Entamoeba moshkovskii in patients with gastrointestinal disorders by single-round PCR. Jpn J Infect Dis. 2010;63:136–138. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Hooshyar H, Rostamkhani P, Rezaian M. Molecular epidemiology of human intestinal amoebas in Iran. Iran J Public Health. 2012;41:10–17. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Pestehchian N, Nazary M, Haghighi A, Salehi M, Yosefi H. Frequency of Entamoeba histolytica and Entamoeba dispar prevalence among patients with gastrointestinal complaints in Chelgerd city, southwest of Iran. J Res Med Sci. 2011;16:1436–40. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Fallah E, Shahbazi A, Yazdanjoii M, Rahimi-Esboei B. Differential detection of Entamoeba histolytica from Entamoeba dispar by parasitological and nested multiplex polymerase chain reaction methods. J Analyt Res Clin Med. 2014;2:27–32. [Google Scholar]

- 17.Hamzah Z, Petmitr S, Mungthin M, Leelayoova S, Chavalitshewinkoon-Petmitr P. Differential Detection of Entamoeba histolytica, Entamoeba dispar, and Entamoeba moshkovskii by a Single-Round PCR Assay. J. Clin. Microbiol. 2006;44:3196–3200. doi: 10.1128/JCM.00778-06. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Kheirandish F, Badparva E, Haghighi A, Nazemalhosseini-Mojarad E, Kazemi B. Differential diagnosis of Entamoeba spp. In gastrointestinal disorder patients in Khorramabad, Iran. Afr J Microbiol Res. 2011;5:2863–2866. [Google Scholar]

- 19.E N, A H, B K, M Z. Prevalence and genetic diversity of Entamoeba histolytica and Entamoeba dispar in Iran. Foodborne Disease and Public Health: National Academy of Sciences, Washington DC, USA. 2008. pp. 31–32.

- 20.E N, M R, A H. Update of knowledge for best Amebiasis management. Gastroenterol hepatol bed bench. 2008;1:45–50. [Google Scholar]

- 21.report W. A consultation with experts on amoebiasis. Mexico City, Mexico. 28- 29th January, 1997. Epidemiol Bull. 1997;18:13–14. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Kermani N, Jafari F, Nazemalhosseini M, Hoseinkhan N, Zali R. Prevalence and associated factors of persistent diarrhea in Iranian children admitted to a pediatric hospital. East Mediterr Health J. 2010;16:831–836. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]