Abstract

BACKGROUND:

Emergency departments (EDs) are critical to the management of acute illness and injury, and the provision of health system access. However, EDs have become increasingly congested due to increased demand, increased complexity of care and blocked access to ongoing care (access block). Congestion has clinical and organisational implications. This paper aims to describe the factors that appear to influence demand for ED services, and their interrelationships as the basis for further research into the role of private hospital EDs.

DATA SOURCES:

Multiple databases (PubMed, ProQuest, Academic Search Elite and Science Direct) and relevant journals were searched using terms related to EDs and emergency health needs. Literature pertaining to emergency department utilisation worldwide was identified, and articles selected for further examination on the basis of their relevance and significance to ED demand.

RESULTS:

Factors influencing ED demand can be categorized into those describing the health needs of the patients, those predisposing a patient to seeking help, and those relating to policy factors such as provision of services and insurance status. This paper describes the factors influencing ED presentations, and proposes a novel conceptual map of their interrelationship.

CONCLUSION:

This review has explored the factors contributing to the growing demand for ED care, the influence these factors have on ED demand, and their interrelationships depicted in the conceptual model.

KEY WORDS: Emergency department, Demand, Crowding, Risk factors, Emergency services, Emergency medicine, Emergency room

INTRODUCTION

Hospital emergency departments (EDs) play a vital role in the acute health care system, providing care for patients with acute illness and injury, and access to the health system. Over the last 15 years,[1-4] EDs in Australia have become progressively more congested due to the combined effects of increasing demand for care,[5-8] increased complexity of care, and access block.[1-3,9] In the 10 years from September 1998 to October 2009, public hospital ED visits have increased from 5 010 000 (268 per 1000 population) to 7 390 000 (331 per thousand population).[10] Figures for private EDs are not available. ED congestion has implications for patient outcomes,[1] as well as for the efficiency and effectiveness of ED operations as evidenced by staff and patient satisfaction.[1]

Factors affecting demand for emergency care are complicated and multifaceted. This study aims to identify from the literature those factors influencing the growing demand for emergency medical care, and to describe their interrelationship. In particular this work is the basis for further research into patients attending private EDs, and therefore particular attention is paid to the factors influencing the demand for private hospital ED care.

METHODS

Multiple databases (PubMed, ProQuest, Academic Search Elite and Science Direct) were searched using the following terms: emergency services/care/visits, emergency medicine, emergencies, emergency department use/utilization/visits, accidents, crowding/crowds, healthcare surveys, health service needs and demand, access block, ambulatory care/utilization, emergency room, frequent ED utilization/users, heat wave, influenza, homelessness, non-urgent visits, perception, regular source of care, predictors, emergency health-care system, health care reform, medicare, Australia, health insurance, insurance policies, and national health insurance.

In addition, seven leading international emergency medicine journals were searched for relevant articles. Annual reports from the Australian Bureau of Statistics, the Australasian College for Emergency Medicine, the Australian Institute of Health and Welfare, the Private Health Insurance Administration Council, the Productivity Commission, and the Queensland Ambulance Service were retrieved via Google. All titles and abstracts were screened by the research team for relevance to the question, and those that addressed the particular issue were examined in detail.

The search yielded 602 articles. Studies were excluded if they were for pediatric patients‘ ED utilization; ambulance utilization; health services not directly related to ED utilization; and psychiatric emergency services utilization. Studies published earlier than 1990 (except Andersen & Newman’s seminal work from 1973) or written in languages other than English were also excluded. This review was based on the remaining 100 articles. The vast majority of these derived from the USA, and therefore tended to reflect the particular environment of the US health system. All were examined for evidence of factors that influence demand or that explain the relationship between such factors. Particular attention was paid to those articles that may explain variances between private and public hospital utilization.

RESULTS

The Australian emergency health care system

The Australian health care system is complex, with community based care provided by both publically and privately funded health professionals, and public and private hospitals.[10] Operational funding for public hospitals relies heavily on the Commonwealth government via Australian Health Care Agreements between the Commonwealth, and State or Territorial Governments. Private hospitals are largely funded by individuals supported by private health insurance, which is in turn subsidised by taxpayers. Private hospitals include for-profit organisations, as well as those run by charitable (mostly religious) organisations.

Australia’s health system is funded principally by government. Medicare[11] is a compulsory universal health insurance scheme funded by general taxation supported by a special purpose Medicare Levy on taxable income. Medicare subsidises the cost of community medical care and provides free public hospital accommodation and treatment.

Private health insurance is a significant part of Australia’s health funding system. According to the Australian Institute of Health and Welfare,[12] private insurance was the main funding source for 37% of hospital separations (ie when a patient is discharged, dies in hospital, or is transferred to another hospital) during 2008–2009. It provides rebates for private treatment in both public and private hospitals, and funding for some ancillary services such as dentistry and physiotherapy.[10] However, ED services provided by private hospitals are not covered by private health insurance.

Private EDs have been an important part of the emergency management system since 1988.[13] They are located mainly in capital cities, with some in regional centers. In the period of 2006-2007, there were an estimated 24 private EDs and 47 private hospitals providing emergency care in Australia.[14] Service quality of private EDs has been high because they meet international standards and a growing demand for emergency services.[14] However, the number of emergency care services provided by private EDs has been lower than the number of people with private health insurance. It was estimated that private EDs provided 500 645 emergency services in the period of 2008-2009,[15] while public EDs provided 7.2 million emergency services in the same period.[16] Although approximately 44% of Australians held private health insurance,[17] private EDs accounted for only 6.5% of total emergency services in that period.

Factors influencing emergency health care demand

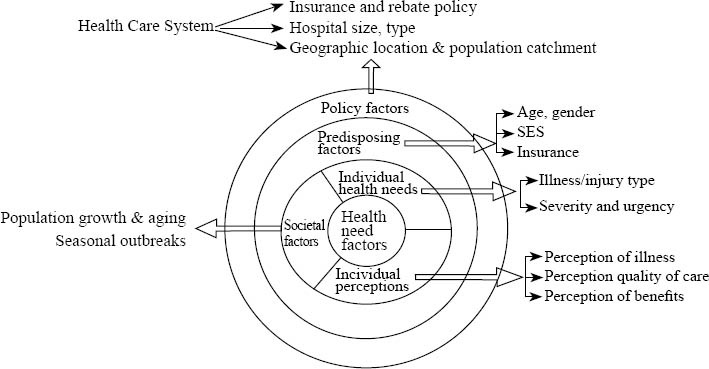

The relationship between factors influencing hospital ED use is summarized in Figure 1, which uses a framework adapted and modified from the Anderson and Newman health utilization model.[18] This well validated model specifies that ‘health need factors’ (defined as a perception by the individual that they have an illness requiring urgent care) are influenced by predisposing factors and policy factors into an action which is to seek acute health care.

Figure 1.

ED utilization literature review model modified from Andersen and Newman health utilization model.

Health need factors include individual health needs, individual perceptions, and societal factors, and are at the centre of the figure, indicating their importance in driving action (Table 1). They are framed by the predisposing and policy factors.

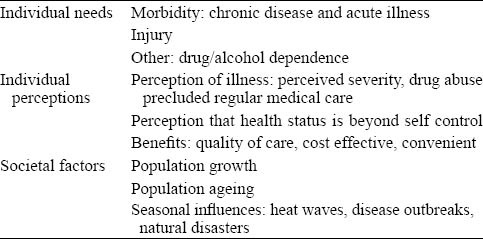

Table 1.

Health need related factors

Health need factors

Individual health needs (morbidity, injury and health related factors)

Individual health need factors, including morbidity, injury, and other health related factors, appear to be the primary predictors of ED utilization.[19-33] A large study of twenty-eight US hospitals concluded that 95% of presenting patients cited medical necessity as their reason for attending ED.[34] Another study showed that poor health was associated with increased ED use among low-income elderly African Americans in New Orleans.[33] Injury has been an indication for ED utilization among the homeless.[26] Drug dependency,[27] uncontrolled asthma[25] and alcohol abuse[28,32] are also associated with increased ED use. A study of crack-cocaine smokers in the USA found that those treated most frequently for drug abuse also had increased ED use.[22]

Individual perceptions (perception of illness, quality of care, and benefits)

Demand for ED service is associated with a variety of individual perceptions. Among these, perceived severity of illness[35-40] is most frequent identified, followed by perceived quality of ED care,[34,37,41] current perceived symptoms,[42] and perceptions of convenience.[34] Other patient beliefs play a role in demand. Some consider that their substance abuse interferes with them seeking care from a regular doctor.[43] The patients who believed that their health status was determined by the "function of external forces" or the "power of the medical personnel" had an increased likelihood of ED use.[33] Another study from the USA[44] found that those who identified ED as their regular source of care were likely to consider ED treatment cost-effective.

Health professionals and patients differ in their beliefs as to why people use ED for non-urgent conditions. A study across five Australian EDs[45] found that clinicians were more likely to emphasize cost and access issues, whereas patients emphasized medical acuity and complexity. However it is patients’ perception, not professionals’ that drive them toward ED for treatment.

Societal factors (growth and ageing, seasonal influences)

As the population grows and ages, ED demand increases. A 1999 study[46] found that ED service demand growth was faster than population growth, and the proportion of ED patients requiring hospital admission was significantly increased, as was patient acuity and length of stay. Between 1988 and 1997, the population in the catchment area of the study hospital rose by 18.6%, and ED visits rose by 27%. Population ageing and economic changes were beyond the scope of this study. A similar result was found in a recent study from the USA,[47] where ED utilization increased by 28.6% while the population increased by 16.1%. This study attributed the increase, in part, to an ageing population.

Seasonal influences such as heat waves, natural disasters and disease outbreaks have demonstrated impact on ED demand. Influenza outbreaks are associated with increased presentations among elders and with ED overcrowding and ambulance diversion.[48,49] In 2006, a Californian heat wave resulted in increased ED presentations among elders (≥65 years of age) and young children (0-4 years of age).[50]

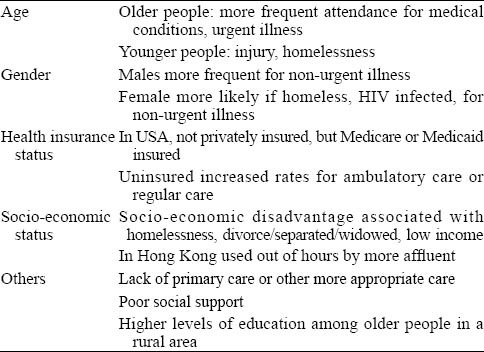

Predisposing factors

Predisposing factors are those that appear to influence the transition of a patient’s health perception into a desire to access emergency health care (Table 2).

Table 2.

Predisposing factors

Age

ED utilization varies among different age groups. Very young children[51] (0-2 year of age) have been found to have a higher rate of ED use for non-urgent illness. A USA study of adolescents in 1998[52] found that those of 18-21 years old were overrepresented in ED visits in proportion to their percentage in the general population. In 2004 a study[53] reviewing the risk factors for returns to ED within 72 hours of initial visit found that older age (>65 years) was associated with increased risk of return. Another study[54] found that those who had 35 or more ED visits over 3 years were significantly older than those with fewer visits.

In general, older people were more likely to use EDs frequently[55] and for urgent illness,[19] while younger people were more likely to use EDs for non-urgent illness[39,51,56-57] and to identify EDs as their usual source of care.[58-59] Younger people tend to present to EDs more frequently for injury,[52,60] while older people are more likely to attend for medical conditions.[60] A study examining the factors associated with ED use among the homeless found that younger age was associated with frequent ED use.[57] However this higher rate of use is likely to reflect particular characteristics of the homeless.

Gender

Being male appears to be an independent predictor of both frequent [61] and repeated ED use among people of 75 years old or over.[62] Males are more likely to use ED for non-urgent illness,[35,63] and more often identify ED as their usual source of care.[58] Inconsistent results were found in some studies. Higher rates of female use were seen amongst the homeless[57] and HIV-infected adults.[64] One Italian study[39] found that females were associated with non-urgent ED use.

Health insurance status

Insurance status influences patterns of ED utilization. A common feature in American studies was that having Medicaid[55,57,65-68] or Medicare[55,57,67-68] was an independent predictor of frequent or any ED use.[30,69] A 2004 study[53] found that being USA Medicare insured was associated with an increased risk of ED early return within 72-hour of the index visit. Several studies[55,65,68] found that being uninsured or lacking access to primary care (PC) did not predict frequent ED use. However, lack of private health insurance and having public insurance (USA Medicare or Medicaid) have been associated with the use of EDs for non-urgent illness.[70] Uninsured people have been found to have an increased rate of using EDs for ambulatory care[71] and to identify the ED as their regular source of care.[58-59] A 1998 study[52] of ED utilization by adolescents found that a lack of health insurance was common among adolescents aged 11 to 21 years who may rely heavily on EDs for their health care needs.

Socio-economic status

Most studies show that socio-economic disadvantage (SED) significantly increases an individual’s likelihood of using ED. Being homeless,[72] divorced, separated or widowed,[21] or having a low income[23,64] is associated with an increased likelihood of ED use. Being homeless[43,57,59,73-74] or having a low income[44,67,69,75] is also directly related to frequent ED use and identifying ED as the regular source of care.

However, a study[51] found the majority of non-urgent ED users (how so ever defined) were white, middle or high income earners, with a regular source of care other than the ED, and these people used EDs for convenience or preference. Another study from Hong Kong[37] found that those with skilled jobs and those living in self-owned property were more likely to use ED for non-urgent illness. While most affluent people in Hong Kong rely on private general practitioners (GPs) for PC, they are not available out of hours, and working people may be reluctant to sacrifice work time to access GP services.

Others (appropriate care, social support, and level of education attainment)

Other factors, such as the availability of appropriate care, social support, and levels of education may affect ED utilization. A 2009 trial [76] examined whether more comprehensive interventions would alter health care seeking behaviors among homeless people. Those to whom housing and case management were offered had fewer subsequent ED visits.

Social support can play a role in ED demand. A 1997 study[59] suggested that lack of social support was a predictor identifying ED as the regular source of care. Another study the same year[62] found that living alone was associated with repeated ED use in those aged 75 and over. A 2003 study[77] found that a lower level of perceived social support could be related to frequent ED use. More recently,[35] patients from smaller sized families were found to be more likely to use ED for non-urgent illness. The authors hypothesized that in the members of larger families may have been available to look after those at home while care-givers took the sick person to the outpatient department during the day.

The level of education may influence the process of decision-making. A study[30] identifying factors associated with having any ED visit (vs. non-ED visits) among people at age of 65 years or older in a rural area found that people with an education standard higher than high school had a significantly greater likelihood of having at least one ED visit. More educated people in rural areas may be more conscious of their health care needs, and thus may seek immediate care when they are unwell. People in rural areas have limited access to PC, so may seek care from EDs.

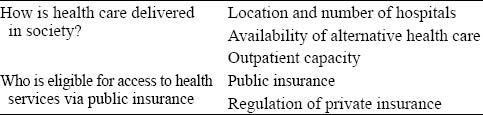

Policy factors

Table 3.

Policy factors

Health policies affect an individual’s health care utilization in two ways. Firstly, policy defines how health care is delivered in society, and dictates the location and number of hospitals, and the availability of alternative health care facilities. Secondly, policy dictates the eligibility of individuals to access health services via public insurance.

PC accessibility is strongly affected by health policy. Better access to PC[21,29,78] and greater continuity of care [78] are significantly associated with decreased ED use. When PC services are not available,[38,40,63,70] or there is an inability to access PC in a timely manner,[79] there is an association with ED use for non-urgent illness. Medicaid beneficiaries receiving outpatient care from Federal Qualified Health Centers[80] have been found to be less likely to use ED services than other Medicaid beneficiaries. A 2006 study[81] found that greater Community Health Centre (CHC) capacity reduced ED use for poor and low-income people, while greater CHC capacity appeared to increase ED use among high-income people. This finding may indicate interaction between variable CHC capacity and level of income in terms of ED utilization. Two other studies[82-83] evaluating whether referring uninsured ED patients to the PC setting would reduce their future ED demand found only a short term increased use of PC, and limited effect on reducing future ED use. Continued use of PC services was not achieved in either study.

Hospital location may affect utilization. One study[84] suggested that elderly people living in remote rural areas were less likely to visit the ED than their urban and adjacent rural counterparts. A 2010 study [85] found that patients in large hospital EDs used the ED more inappropriately. Another study from the USA [81] suggested that communities with high ED use tended to have less outpatient capacity than communities with lower ED use, and had more EDs relative to population than low-ED use communities.

Health policy changes may also affect ED demand. In the USA,[86] more than 50 000 Medicaid beneficiaries were dis-enrolled on implementation of the Oregon Health Plan in March 2003. A sudden and continued increase of ED visits by uninsured people ensued.

DISCUSSION

In short, the factors described impact on demand for ED care. The literature does not identify the relative contribution made by these factors, nor their capacity to predict future growth.

Much of the political discussion of this issue relates to ED use for non-urgent illness by those labeled as "inappropriate ED users". However, this title is based on clinical definitions made by health professionals. Significant differences exist between health professionals and lay people regarding their perceptions of urgency of illness. Most ED patients perceive their problems as urgent,[35,40,45,87] even though their conditions may be deemed non-urgent by health professionals. Those at SED, with public health insurance,[47,51,50] or with limited access to PC,[40,79] are generally considered more likely to use EDs for non-urgent conditions although two studies have identified the opposite.[37,51]

A small number of frequent ED users account for a disproportionate number of total ED visits.[67,74,88-89] People at SED are at high risk of frequent ED use,[57,67,73-75,90] raising questions about the adequacy of other parts of the health care system. However, frequent ED users are generally sicker than infrequent ED users,[57,65-69,75, 77,88-96] most have another regular source of care[66-67, 92] and are heavy users of other parts of the health care system.[65,77,89,91,93] Interventions[97-99] addressing their non-medical needs have resulted in less frequent ED use, while those focusing on medical needs alone failed to achieve that objective.[100] Frequent ED users are often from vulnerable groups, therefore comprehensive care must address medical needs, social needs, and psychological requirements.

While it is impossible to draw causal relationships between the above variables and ED utilization, some key factors have emerged. Individual ED use is driven by health care needs, perceptions of illness, and societal factors which influence these. Limited access to PC is significantly associated with ED use. Individual perceptions influence where people seek care, and many seek ED care for conditions they perceive as urgent, but which health care providers consider non-urgent. Both PC accessibility and individual perceptions influence ED use for non-urgent illness.

Those at SED are high users of ED in all forms. Such people have disproportionate health care requirements and limited access to PC. The influence of SED and PC accessibility on ED utilization may be used to direct future policy.

In conclusion, this review has explored the factors contributing to the growing demand for ED care, the influence these factors have on ED demand, and their interrelationships depicted in the conceptual model. No evidence was found in the literature of the relative influence of these factors in choosing between public and private hospital ED care. Future research is needed to explore the role of private hospital EDs, and to inform policy development for their better use within the Australian system. This may help alleviate the burden on public hospital EDs and improve acute care for critically ill patients in Australia.

There were limitations in our study. Study designs, settings and outcome measures varied from study to study, making them difficult to compare. The studies that were reviewed suffered from a range of shortcomings, including retrospective design, and limited power to define causal relationships. Many were limited to one or two emergency departments, or had small sample sizes affecting generalizability. Most were conducted outside Australia so may have limited applicability to local conditions. There was a significant lack of any studies that addressed the particular issues of private EDs and their relative role within the emergency health system.

Footnotes

Funding: None.

Ethical approval: Not needed.

Conflicts of interest: Xiang-yu Hou is a member of the editorial board of the WJEM.

Contributors: He J proposed the study and wrote the paper. All authors contributed to the design and interpretation of the study and to further drafts.

REFERENCES

- 1.Richardson DB, Mountain D. Myths versus facts in emergency department overcrowding and hospital access block. Med J. 2009;190:369–374. doi: 10.5694/j.1326-5377.2009.tb02451.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Richardson DB. Responses to access block in Australia: Australian Capital Territory. Med J Aust. 2003;178:103–104. doi: 10.5694/j.1326-5377.2003.tb05093.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Fatovich DM, Nagree Y, Sprivulis P. Access block causes emergency department overcrowding and ambulance diversion in Perth, Western Australia. Emerg Med J. 2005;22:351–354. doi: 10.1136/emj.2004.018002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Fatovich DM, Hirsch RL. Entry overload, emergency department overcrowding, and ambulance bypass. Emerg Med J. 2003;20:406–409. doi: 10.1136/emj.20.5.406. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Brisbane: Queensland Ambulance Services; QAS (2007). Queensland Ambulance Services Audit Report. www.emergency. qld.gov.au/publications/pdf/FinalReport.pdf . [Google Scholar]

- 6.Productivity Commission (2010). Report on Government Services 2010. Productivity Commission. http://uat.pc.gov.au/_data/assets/pdf_fi le/0005/93902/rogs-2010-volume1.pdf .

- 7.Canberra: Australian Institute of Health and Welfare, cat. no. HSE 71; AIHW (2009). Australian Hospital Statistics 2007-08. Services Series No. 33. http://www.aihw.gov.au/publications/index.cfm/title/10776 . [Google Scholar]

- 8.Canberra: Australian Institute of Health and Welfare, cat. no. HSE 55; AIHW (2008). Australian Hospital Statistics. 2006-07. Health Services Series No. 31. www.aihw.gov.au/publication-detail/?id=6442468093 . [Google Scholar]

- 9.ACEM (2004). Access Block and Overcrowding i n Emergency Department. Australian College for Emergency Medicine. www.acem.org.au/media/Access_Block1.pdf .

- 10.Jane H. Incremental change in the Australian health care system. Health Affairs. 1999;18:95. doi: 10.1377/hlthaff.18.3.95. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Department of Human Services. Welcome to Medicare. 2011. [Accessed 20th September 2011]. http://www.medicareaustralia.gov.au/

- 12.Canberra: Australia Institute of Health and Welfare; AIHW (2011). Australia's health 2010. Cat. no. AUS 122. www. aihw.gov.au/publication-detail/?id=6442468376 . [Google Scholar]

- 13.Commonwealth Department of Health and Ageing (2001). Approved Pr ivate Emergency Depar tment Program Guidelines. www.acem.org.au/media/policies...guidelines/guidelines_apedp.pdf .

- 14.Canberra: Australian Bureau of Statistics; ABS (2008e). Australia's private hospital sector. http://www.pc.gov.au/__data/assets/pdf_file/0003/93036/06-chapter3.pdf . [Google Scholar]

- 15.Canberra: AustralianBureau of Statistics; ABS (2010). Private Hospitals Australia. http://www.abs.gov.au/ausstats/abs@.nsf/mf/4390.0 . [Google Scholar]

- 16.Canberra: Australian Institute of Health and Welfare; AIHW (2010). Australian hospital statistics 2008-09. Cat. no. HSE 84. www.aihw.gov.au/publication-detail/?id=6442468373 . [Google Scholar]

- 17.Australian Trade Commission (2009). Insurance in Australia. http://www.austrade.gov.au/ArticleDocuments/1358/Insurance-in-Australia-2009.pdf.aspx .

- 18.Andersen R, Newman JF. Societal and individual determinants of medical care utilization in the United States. Milbank MemFund Q Health Soc Winter. 1973;51:95–124. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Wolinsky FD, Liu L, Miller TR, An H, Geweke JF, Kaskie B, et al. Emergency department utilization patterns among oldera dults. J Gerontol A Biol Sci Med Sci. 2008;63:204–209. doi: 10.1093/gerona/63.2.204. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Weber EJ, Showstack JA, Hunt KA, Colby DC, Callaham ML. Does lack of a usual source of care or health insurance increase the likelihood of an emergency department visit? Results of a national population-based study. Ann Emerg Med. 2005;45:4–12. doi: 10.1016/j.annemergmed.2004.06.023. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Simmons LA, Anderson EA, Braun B. Health needs and health care utilization among rural, low-income women. Women & Health. 2008;47:53–69. doi: 10.1080/03630240802100317. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Siegal HA, Falck RS, Jichuan W, Carlson RG, Massimino KP. Emergency Department Utilization by Crack-Cocaine Smokers in Dayton, Ohio. Am J Drug Alcohol Abuse. 2006;32:55–68. doi: 10.1080/00952990500328737. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Shah SM, Cook DG. Socio-economic determinants of casualty and NHS Direct use. J Public Health (Oxf) 2008;30:75–81. doi: 10.1093/pubmed/fdn001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Shah MN, Rathouz PJ, Chin MH. Emergency department utilization by noninstitutionalized elders. Acad Emerg Med. 2001;8:267–273. doi: 10.1111/j.1553-2712.2001.tb01303.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Guilbert TW, Garris C, Jhingran P, Bonafede M, Tomaszewski KJ, Bonus T, et al. Asthma that is not well-controlled is associated with increased healthcare utilization and decreased quality of life. J Asthma. 2011;48:126–132. doi: 10.3109/02770903.2010.535879. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Padgett DK, Struening EL, Andrews H, Pittman J. Predictors of emergency room use by homeless adults in New York City: The influence of predisposing, enabling and need factors. Soc Sci Med. 1995;41:547–556. doi: 10.1016/0277-9536(94)00364-y. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Neighbors CJ, Zywiak WH, Stout RL, Hoffmann NG. Psychobehavioral risk factors, substance treatment engagement and clinical outcomes as predictors of emergency department use and medical hospitalization. J Stud Alcohol. 2005;66:295–304. doi: 10.15288/jsa.2005.66.295. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Merrick ESL, Hodgkin D, Garnick DW, Horgan CM, Panas L, Ryan M, et al. Older adults’ inpatient and emergency department utilization for ambulatory-care-sensitive conditions: relationship with alcohol consumption. J Aging Health. 2011;23:86–111. doi: 10.1177/0898264310383156. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.McCusker J, Karp I, Cardin S, Durand P, Morin J. Determinants of emergency department visits by older adults: a systematic review. Acad Emerg Med. 2003;10:1362–1370. doi: 10.1111/j.1553-2712.2003.tb00011.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Fan L, Shah MN, Veazie PJ, Friedman B. Factors associated with emergency department use among the rural elderly. J Rural Health. 2011;27:39–49. doi: 10.1111/j.1748-0361.2010.00313.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Cowie R, Cowie R, Underwood M, Revitt S, Field S. Predicting emergency department utilization in adults with asthma: a cohort study. J Asthma. 2001;38:179. doi: 10.1081/jas-100000037. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Cherpitel CJ. Drinking patterns and problems, drug use and health services utilization: a comparison of two regions in the US general population. Drug Alcohol Depend. 1999;53:231–237. doi: 10.1016/s0376-8716(98)00138-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Bazargan M, Bazargan S, Baker RS. Emergency department utilization, hospital admissions, and physician visits among elderly african american persons. Gerontologist. 1998;38:25–36. doi: 10.1093/geront/38.1.25. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Ragin DF, Hwang U, Cydulka RK, Holson D, Haley LL, Jr, Richards CF, et al. Reasons for using the emergency department: results of the EMPATH study. Acad Emerg Med. 2005;12:1158–1166. doi: 10.1197/j.aem.2005.06.030. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Selasawati HG, Naing L, Wan Aasim WA, Winn T, Rusli BN. Factors associated with inappropriate utilisation of emergency department services. Asia Pac J Public Health. 2007;19:29–36. doi: 10.1177/10105395070190020601. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Olsson M, Hansagi H. Repeated use of the emergency department: qualitative study of the patient's perspective. Emerg Med J. 2001;18:430–434. doi: 10.1136/emj.18.6.430. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Lee A, Lau FL, Hazlett CB, Kam CW, Wong P, Wong TW, et al. Factors associated with non-urgent utilization of Accident and Emergency services: a case-control study in Hong Kong. Soc Sci Med. 2000;51:1075–1085. doi: 10.1016/s0277-9536(00)00039-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Callen J, Blundell L, Prgomet M. Emergency department use in a rural Australian setting: are the factors prompting attendance appropriate? Aust Health Rev. 2008;32:710. doi: 10.1071/ah080710. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Bianco A, Pileggi C, Angelillo IF. Non-urgent visits to a hospital emergency department in Italy. Public Health. 2003;117:250. doi: 10.1016/S0033-3506(03)00069-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Baker DW, Stevens CD, Brook RH. Determinants of emergency department use by ambulatory patients at an urban public hospital. Ann Emerg Med. 1995;25:311–316. doi: 10.1016/s0196-0644(95)70285-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Sempere-Selva T, Peiró S, Sendra-Pina P, Martínez-Espín C, López-Aguilera I. Inappropriate use of an accident and emergency department: Magnitude, associated factors, and reasons—An approach with explicit criteria. Ann Emerg Med. 2001;37:568–579. doi: 10.1067/mem.2001.113464. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Backman AS, Blomqvist P, Lagerlund M, Carlsson-Holm E, Adami J. Characteristics of non-urgent patients. Cross-sectional study of emergency department and primary care patients. Scand J Prim Health Care. 2008;26:181–187. doi: 10.1080/02813430802095838. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Larson MJ, Saitz R, Horton NJ, Lloyd-Travaglini C, Samet JH. Emergency department and hospital utilization among alcohol and drug-dependent detoxification patients without primary medical care. Am J Drug Alcohol Abuse. 2006;32:435–452. doi: 10.1080/00952990600753958. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.O’Brien GM, Stein MD, Zierler S, Shapiro M, O’Sullivan P, Woolard R. Ann Emerg Med. Vol. 30. San Antonio, TX: presented at the Society for Acad Emerg Med Annual Meeting, May 1995; 1997. Use of the ED as a regular source of care: associated factors beyond lack of health insurance; pp. 286–291. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Masso M, Bezzina AJ, Siminski P, Middleton R, Eagar K. Why patients attend emergency departments for conditions potentially appropriate for primary care: reasons given by patients and clinicians differ. Emerg Med Australas. 2007;19:333–340. doi: 10.1111/j.1742-6723.2007.00968.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Meggs WJ, Czaplijski T, Benson N. Trends in Emergency Department Utilization 1988-1997. Acad Emerg Med. 1999;6:1030–1035. doi: 10.1111/j.1553-2712.1999.tb01188.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Reeder T, Locascio E, Tucker J, Czaplijski T, Benson N, Meggs W. ED utilization: The effect of changing demographics from 1992 to 2000. Am J Emerg Med. 2002;20:583–587. doi: 10.1053/ajem.2002.35462. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Schull MJ, Mamdani MM, Fang J. Community influenza outbreaks and emergency department ambulance diversion. Ann Emerg Med. 2004;44:61–67. doi: 10.1016/j.annemergmed.2003.12.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Schull MJ, Mamdani MM, Fang J. Influenza and emergency department utilization by elders. Acad Emerg Med. 2005;12:338–344. doi: 10.1197/j.aem.2004.11.020. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Knowlton K, Rotkin-Ellman M, King G, Margolis HG, Smith D, Solomon G, et al. The 2006 California Heat Wave: impacts on hospitalizations and emergency department visits. Environ Health Perspect. 2009;117:61–67. doi: 10.1289/ehp.11594. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Cunningham PJ, Clancy CM, Cohen JW, Wilets M. The use of hospital emergency departments for nonurgent health problems: a national perspective. Med Care Res Rev. 1995;52:453–474. doi: 10.1177/107755879505200402. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Ziv A, Boulet JR, Slap GB. Emergency department utilization by adolescents in the United. Pediatrics. 1998;101:987. doi: 10.1542/peds.101.6.987. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Martin-Gill C, Reiser RC. Risk factors for 72-hour admission to the ED. Am J Emerg Med. 2004;22:448–453. doi: 10.1016/j.ajem.2004.07.023. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Shiber JR, Longley MB, Brewer KL. Hyper-use of the ED. Am J Emerg Med. 2009;27:588–594. doi: 10.1016/j.ajem.2008.05.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Baker DW, Stevens CD, Brook RH. Determinants of emergency department use: are race and ethnicity important? Ann Emerg Med. 1996;28:677–682. doi: 10.1016/s0196-0644(96)70093-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Rajpar SF, Smith MA, Cooke MW. Study of choice between accident and emergency departments and general practice centres for out of hours primary care problems. J Accid Emerg Med. 2000;17:18–21. doi: 10.1136/emj.17.1.18. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Kushel MB, Perry S, Clark R, Moss AR, Bangsberg D. Emergency department use among the homeless and marginally housed: results from a community-based study. Am J Public Health. 2002;92:778–784. doi: 10.2105/ajph.92.5.778. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Walls CA, Rhodes KV, Kennedy JJ. The emergency department as usual source of medical care: estimates from the 1998 National Health Interview Survey. Acad Emerg Med. 2002;9:1140–1145. doi: 10.1111/j.1553-2712.2002.tb01568.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Lang T, Davido A, Diakite B, Agay E, Viel JF, Flicoteaux B. Using the hospital emergency department as a regular source of care. Eur J Epidemiol. 1997;13:223–228. doi: 10.1023/a:1007372800998. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Downing A, Wilson R. Older people's use of accident and emergency services. Age Ageing. 2004;34:24–30. doi: 10.1093/ageing/afh214. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Milbrett P, Halm M. Characteristics and predictors of frequent utilization of emergency services. J Emerg Nurs. 2009;35:191–198. doi: 10.1016/j.jen.2008.04.032. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.McCusker J, Healey E, Bellavance F, Connolly B. Predictors of repeat emergency department visits by elders. Acad Emerg Med. 1997;4:581–588. doi: 10.1111/j.1553-2712.1997.tb03582.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Butler PA. Medicaid HMO enrollees in the emergency room: use of nonemergency care. Med Care Res Rev. 1998;55:7898. doi: 10.1177/107755879805500105. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Gifford AL, Collins R, Timberlake D, Schuster MA, Shapiro MF, Bozzette SA, et al. Propensity of HIV patients to seek urgent and emergent care. J Gen Intern Med. 2000;15:833–840. doi: 10.1046/j.1525-1497.2000.91136.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Sandoval E, Smith S, Walter J, Schuman SA, Olson MP, Striefler R, et al. A comparison of frequent and infrequent visitors to an urban emergency department. J Emerg Med. 2010;38:115–121. doi: 10.1016/j.jemermed.2007.09.042. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Pines J, Buford K. Predictors of frequent emergency department utilization in Southeastern Pennsylvania. J Asthma. 2006;43:219–223. doi: 10.1080/02770900600567015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Hunt KA, Weber EJ, Showstack JA, Colby DC, Callaham ML. Characteristics of frequent users of emergency departments. Ann Emerg Med. 2006;48:1–8. doi: 10.1016/j.annemergmed.2005.12.030. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Fuda KK, Immekus R. Frequent users of Massachusetts emergency departments: a statewide analysis. Ann Emerg Med. 2006;48:9–16. doi: 10.1016/j.annemergmed.2006.03.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Zuckerman S, Shen YC. Characteristics of occasional and frequent emergency department users: do insurance coverage and access to care matter? Med Care. 2004;42:176–182. doi: 10.1097/01.mlr.0000108747.51198.41. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Brim C. A descriptive analysis of the non-urgent use of emergency departments. Nurse Res. 2008;15:72–88. doi: 10.7748/nr2008.04.15.3.72.c6458. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71.Pontes MCF, Pontes NMH, Lewis PA. Health insurance sources for nonelderly patient visits to physician offices, hospital outpatient departments, and emergency departments in the United States. Hosp Top. 2009;87:19–27. doi: 10.3200/HTPS.87.3.19-27. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72.Verlinde E, Verdée T, Van de Walle M, Art B, De Maeseneer J, Willems S. Unique health care utilization patterns in a homeless population in Ghent. BMC Health Serv Res. 2010;10:242–250. doi: 10.1186/1472-6963-10-242. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73.Palepu A, Tyndall MW, Leon H, Muller J, O’Shaughnessy MV, Schechter MT, et al. Hospital utilization and costs in a cohort of injection drug users. CMAJ. 2001;165:415–420. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74.Mandelberg JH, Kuhn RE, Kohn MA. Epidemiologic analysis of an urban, public emergency department's frequent users. Acad Emerg Med. 2000;7:637–646. doi: 10.1111/j.1553-2712.2000.tb02037.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 75.Benjamin CS, Helen RB, Troyen AB. Predictors and outcomes of frequent emergency department users. Acad Emerg Med. 2003;10:320. doi: 10.1111/j.1553-2712.2003.tb01344.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 76.Sadowski LS, Kee RA, VanderWeele TJ, Buchanan D. Effect of a housing and case management program on emergency department visits and hospitalizations among chronically ill homeless adults. JAMA. 2009;301:1771–1778. doi: 10.1001/jama.2009.561. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 77.Byrne M, Murphy AW, Plunkett PK, McGee HM, Murray A, Bury G. Frequent attenders to an emergency department: A study of primary health care use, medical profile, and psychosocial characteristics. Ann Emerg Med. 2003;41:309–318. doi: 10.1067/mem.2003.68. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 78.Ionescu-Ittu R, McCusker J, Ciampi A, Vadeboncoeur AM, Roberge D, Larouche D, et al. Continuity of primary care and emergency department utilization among elderly people. CMAJ. 2007;177:1362–1368. doi: 10.1503/cmaj.061615. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 79.Howard MS, Davis BA, Anderson C, Cherry D, Koller P, Shelton D. Patients’ perspective on choosing the emergency department for nonurgent medical care: a qualitative study exploring one reason for overcrowding. J Emergency Nurs. 2005;31:429–435. doi: 10.1016/j.jen.2005.06.023. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 80.Falik M, Needleman J, Wells BL, Korb J. Ambulatory care sensitive hospitalizations and emergency visits: experiences of Medicaid patients using federally qualified health centers. Med Care. 2001;39:551–561. doi: 10.1097/00005650-200106000-00004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 81.Cunningham PJ. What accounts for differences in the use of hospital emergency departments across U.S. communities? Health Aff (Millwood) 2006;25:w324–336. doi: 10.1377/hlthaff.25.w324. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 82.McCarthy ML, Hirshon JM, Ruggles RL, Docimo AB, Welinsky M, Bessman ES. Referral of medically uninsured emergency department patients to primary care. Acad Emerg Med. 2002;9:639–642. doi: 10.1111/j.1553-2712.2002.tb02305.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 83.Horwitz SM, Busch SH, Balestracci KM, Ellingson KD, Rawlings J. Intensive intervention improves primary care follow-up for uninsured emergency department patients. Acad Emerg Med. 2005;12:647–652. doi: 10.1197/j.aem.2005.02.015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 84.Lishner DM, Rosenblatt RA, Baldwin L-M, Hart LG. Emergency department use by the rural elderly. J Emerg Med. 2000;18:289–297. doi: 10.1016/s0736-4679(99)00217-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 85.Chiou S-J, Campbell C, Myers L, Culbertson R, Horswell R. Factors influencing inappropriate use of ED visits among type 2 diabetics in an evidence-based management programme. J Eval Clin Pract. 2010;16:1048–1054. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2753.2009.01248.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 86.Lowe RA, McConnell KJ, Vogt ME, Smith JA. Impact of medicaid cutbacks on emergency department use: the oregon experience. Ann Emerg Med. 2008;52:626–634. doi: 10.1016/j.annemergmed.2008.01.335. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 87.Gill JM, Riley AW. Nonurgent use of hospital emergency departments: urgency from the patient's perspective. J Fam Pract. 1996;42:491–496. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 88.Rask K, Williams M, McNagny S, Parker R, Baker D. Ambulatory health care use by patients in a public hospital emergency department. J Gen Intern Med. 1998;13:614–620. doi: 10.1046/j.1525-1497.1998.00184.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 89.Hansagi H, Olsson M, Sjöberg S, Tomson Y, Göransson S. Frequent use of the hospital emergency department is indicative of high use of other health care services. Ann Emerg Med. 2001;37:561–567. doi: 10.1067/mem.2001.111762. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 90.Dent AW, Phillips GA, Chenhall AJ, McGregor LR. The heaviest repeat users of an inner city emergency department are not general practice patients. Emerg Med. 2003;15:322–329. doi: 10.1046/j.1442-2026.2003.00470.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 91.Williams ERL, Guthrie E, Mackway-Jones K, James M, Tomenson B, Eastham J, et al. Psychiatric status, somatisation, and health care utilization of frequent attenders at the emergency department: A comparison with routine attenders. J Psychosom Res. 2001;50:161–167. doi: 10.1016/s0022-3999(00)00228-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 92.Lucas RH, Sanford SM. An analysis of frequent users of emergency care at an urban university hospital. Ann Emerg Med. 1998;32:563–568. doi: 10.1016/s0196-0644(98)70033-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 93.LaCalle E, Rabin E. Frequent users of emergency departments: the myths, the data, and the policy implications. Ann Emerg Med. 2010;56:42–48. doi: 10.1016/j.annemergmed.2010.01.032. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 94.Ford JG, Meyer IH, Sternfels P, Findley SE, McLean DE, Fagan JK, et al. patterns and predictors of asthma-related emergency department use in harlem. Chest. 2001;120:1129. doi: 10.1378/chest.120.4.1129. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 95.Fernandes AK, Mallmann F, Steinhorst AMP, Nogueira FL, Avila EM, Saucedo DZ, et al. Characteristics of acute asthma patients attended frequently compared with those attended only occasionally in an emergency department. J Asthma. 2003;40:683. doi: 10.1081/jas-120023487. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 96.Tsai CL, Griswold SK, Clark S, Camargo CA., Jr Factors associated with frequency of emergency department visits for chronic obstructive pulmonary disease exacerbation. J Gen Intern Med. 2007;22:299–804. doi: 10.1007/s11606-007-0191-7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 97.Skinner J, Carter L, Haxton C. Case management of patients who frequently present to a Scottish emergency department. Emerge Medi J. 2009;26:103–105. doi: 10.1136/emj.2008.063081. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 98.Pope D, Fernandes CM, Bouthillette F, Etherington J. Frequent users of the emergency department: a program to improve care and reduce visits. CMAJ. 2000;162:1017–1020. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 99.Okin RL, Boccellari A, Azocar F, Shumway M, O’Brien K, Gelb A, et al. The effects of clinical case management on hospital service use among ED frequent users. Am J Emerg Med. 2000;18:603–608. doi: 10.1053/ajem.2000.9292. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 100.Spillane LL, Lumb EW, Cobaugh DJ, Wilcox SR, Clark JS, Schneider SM. Frequent Users of the Emergency Department: Can We Intervene? Acad Emerg Med. 1997;4:574–580. doi: 10.1111/j.1553-2712.1997.tb03581.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]