Abstract

BACKGROUND:

S100B is involved in brain injury. This study aimed to determine plasma and cerebral spinal fluid (CSF) levels of S100B in patients with spontaneous intracerebral hemorrhage (ICH), and to correlate S100B levels with Glasgow Coma Scale (GCS) scores, ICH volumes, presence of intraventricular hemorrhage (IVH), and survival rate, and to correlate CSF S100B levels with plasma S100B levels as well as CSF interleukin-1beta (IL-1β) levels.

METHODS:

Ten patients with suspicion of subarachnoid hemorrhage and 38 patients with spontaneous basal ganglia hemorrhage were included in the study. Their plasma and CSF samples were collected. The concentrations of IL-1β in CSF and S100B in plasma and CSF were analyzed by enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay.

RESULTS:

Plasma or CSF S100B levels in the ICH group were significantly higher than those in the control group (178.7±74.2 versus 63.2±23.0 pg/ml; P<0.001 or 158.1±70.9 versus 1.8±0.7 ng/ml; P<0.001). S100B levels were highly associated with GCS scores, ICH volumes, presence of IVH, and survival rate (all P<0.05). CSF S100B levels were highly associated with plasma S100B levels as well as CSF IL-1β levels (both P<0.01) in patients with ICH. A receiver operating characteristic curve identified CSF and plasma S100B cutoff levels that predicted 1-week mortality of patients with a high sensitivity and specificity. The areas under curves (AUCs) of GCS scores and ICH volumes were larger than those of CSF and plasma S100B levels, but the differences were not statistically significant (P>0.05).

CONCLUSION:

High levels of S100B are present in the cerebrospinal fluid and peripheral blood of patients with ICH and may contribute to the inflammatory processes of ICH. The levels of CSF and plasma S100B after spontaneous onset of ICH seem to correlate with clinical outcome in these patients. Increases in peripheral S100B properly reflect brain injury, and plasma S100B level may serve as a useful clinical marker for evaluating the prognosis of ICH.

KEY WORDS: S100B, Interleukin-1 beta, Intracerebral hemorrhage, Intraventricular hemorrhage, Brain injury, Inflammation, Pathogenesis

INTRODUCTION

S100B or the PP form of S100 protein is a 21-kD, calcium-binding protein that is mainly expressed in astroglial cells in the central nervous system.[1] While S100B is involved in multiple intracellular processes as a neurotrophic factor, high concentrations of S100B have been shown to induce neuronal death, leading to the induction of pro-inflammatory cytokines such as interleukin-1 beta (IL-1β) and inflammatory stress-related enzymes like inducible nitric oxide synthase.[2-4] Some in vitro data indicate a cross-talk between S100B and IL-1β, which up-regulate each other.[5] Interestingly, elevated expression of S100B has been described in acute brain injury after ICH,[6] with conditions also associated with elevation of IL-1β.[7] We assume that S100B levels in the cerebrospinal fluid (CSF) could be associated with IL-1β levels of CSF and that S100B could play an important role in the inflammatory processes of intracranial hemorrhage (ICH).

The S100B level in peripheral blood is known to be elevated in patients with various disorders of the central nervous system including intracerebral hemorrhage and also serves as a well-known biomarker for the severity of brain damage to predict the prognosis after ICH.[8] To our knowledge, however, none of the study has evaluated changes of CSF S100B levels after brain injury in patients with ICH.

Since the peripheral S100B level has been used to suggest the extent of brain damage, the mechanisms underlying the increased peripheral S100B level have been investigated in recent years. Previous studies[9,10] have suggested that S100b secrets increasingly from disrupted and /or activated glial cells into CSF and that S100B subsequently leaks into the blood stream through the damaged blood-brain barrier. Moreover, Diehl et al[11] reported that the plasma S100B level was not always correlated with the CSF S100B level in a rat model of post-traumatic disorder, suggesting an extracerebral origin of peripheral S100B. Despite these findings, the precise mechanisms of plasma S100B elevation have not yet been investigated in patients with ICH.

In this study, we investigated changes in CSF and plasma S100B levels, the correlations between the CSF and plasma S100B levels for determination of whether increased peripheral S100B properly reflect the conditions of the central nervous system, and the correlations between the CSF S100B and IL-1β levels for determination of the role of S100B in the inflammatory processes and for evaluation of whether S100B levels are associated with GCS scores, ICH volumes, presence of intraventricular hemorrhage (IVH), and survival rate in patients with ICH.

METHODS

Patients and controls

Between February 2007 and August 2008, 38 consecutive patients with spontaneous hemorrhage of the basal ganglia who had been admitted to the intensive care unit of the First Hangzhou Municipal People's Hospital were enrolled in the study. ICH was defined as intraparenchymal hemorrhage of the brain. Hypertension and diabetes mellitus were diagnosed previously in the patients.

The patients met the following inclusion criteria: (1) ICH noted on brain computed tomograph (CT) scan on their presentation to the emergency department; (2) age between 40 and 80 years; (3) admission time less than 6 hours; (4) no other previous systemic diseases including uremia, liver cirrhosis, malignancy, and chronic heart or lung disease except for diabetes mellitus and hypertension; (5) need and acceptance of surgical therapy; and (6) time to surgery within 12 hours. The exclusion criteria included: (1) history of head trauma or previous stroke; (2) use of antiplatelet or anticoagulant medication; (3) history of arteriovenous malformation of the brain; and (4) history of ruptured cerebral aneurysm.

A control group consisted of 10 age- and sex-matched patients admitted to the neurosurgery department for suspected subarachnoid hemorrhage, with normal results of brain magnetic resonance imaging and without vascular risk factors. In these patients a lumbar puncture showed negative results.

Informed consent was obtained from all participants in the study. The study protocol was approved by the Ethics Committee of the First Hangzhou Municipal People's Hospital.

Clinical and neuroradiological data

Age, sex, GCS score, body temperature, heart rate, respiratory rate, systolic arterial pressure, and diastolic arterial pressure of the participants were recorded on admission to the emergency department. Arterial pressures were measured non-invasively using a conventional blood pressure sphygmomanometer. Mean arterial pressure was calculated from the diastolic and systolic values (Mean arterial pressure=diastolic arterial pressure+1/3[systolic arterial pressure - diastolic arterial pressure]).

Diagnoses of the disease were confirmed by brain CT. IVH was determined by brain CT for the presence of blood in the ventricles. The amount of IVH was graded as follows: grade 0, no IVH; grade 1, slight hemorrhage in the third or fourth ventricle or occipital horns; grade 2, moderate hemorrhage in the ventricles; and grade 3, severe hemorrhage packing the ventricular system.[12, 13] ICH volume was calculated according to the formula A×B×C×0.5, where A and B represent the largest perpendicular diameters through the hyperdense area on CT scan, and C represents the thickness of ICH (the number of 10-mm slices containing hemorrhage).[14] Hydrocephalus was defined as the presence of dilated ventricles on brain CT scan. The hydrocephalus of ICH patients was assessed by 2 doctors. Preoperative hemorrhage growth was defined as an increase in the volume of intraparenchymal hemorrhage >33% as measured by CT compared with the initial CT scan.[15] Postoperative re-bleeding was identified when the postoperative CT volume was greater than the preoperative volume or there was a <5 ml difference in the pre- and postoperative CT blood volume measurements.[16]

Management of intracerebral hemorrhage

Treatments of the disease included surgical therapy, mechanical ventilation, blood pressure control, use of intravenous fluids, hyperosmolar agents, and H2 blockers, early nutritional support, and physical therapy. Decision-making for intubation and mechanical ventilation was based on the level of consciousness of individuals, ability to protect their airway, and arterial blood gas levels.[17-19] When clinical and radiological examinations provided some estimated elevation of intracranial pressure, osmotherapy with intravenous mannitol was administered.[20] The mean arterial pressure below 130 mmHg (systolic arterial pressure below 170 mmHg) was maintained.[21]

Craniotomy was performed with a small bone window (diameter 3-4cm) or with a large bone flap (diameter 10-12cm, and defined as external decompression) for evacuation of hematoma and external ventricular drainage. The criteria for evacuation of hematoma included: (1) level of consciousness, GCS scores 5-12, and (2) volume of hemorrhage, hematoma >30ml in volume on CT scan, and those factors causing significant mass effect with a midline shift. The exclusion criteria for evacuation of hematoma included: (1) artificial maintenance of blood pressure and respiration, and (2) alert or somnolent, GCS scores 13-15. External ventricular drainage was indicated for hydrocephalus or/and IVH with grade 2-3. External decompression depended on intracranial pressure and the preference of neurosurgeons.

Neurological deterioration was defined in patients with one or more of the following clinically identified episodes: (1) a spontaneous decrease in GCS scores 2 or more from the previous examination; (2) a further loss of papillary reactivity; and (3) development of papillary asymmetry greater than 1 mm. In the event of such an occurrence, brain CT was performed to identify preoperative hemorrhage growth or postoperative re-bleeding.

Collection of samples

In the control group, venous blood was drawn on admission and CSF samples were collected when lumbar puncture was performed. In the ICH patients, venous blood was drawn on admission and before surgery. CSF samples were collected through external ventricular drainage catheters, puncturing ventricles, or basal cistern during the operation. Blood samples were immediately placed into sterile EDTA test tubes and centrifuged at 1500g for 20 minutes at 4°C to collect plasma. Plasma was stored at -70°C until being assayed. Also CSF samples were immediately placed into sterile test tubes. CSF was obtained by the above-mentioned centrifugation and then stored at -70°C until being assayed.

The concentrations of IL-1β in CSF and S100B in plasma and CSF were analyzed by enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay (ELISA) using commercial kits (R&D Systems, Minneapolis, Minn, USA) in accordance with the instructions of the manufacturer. Outcome was assessed as mortality in one week. Cause of death during the study was ICH.

Statistical analysis

Statistical analysis was made using SPSS 10.0 software (SPSS Inc., Chicago, USA) and MedCalc 9.6.4.0 software (MedCalc Software, Mariakerke, Belgium). The areas under the curve (AUC) were presented as mean±SEM. Other continuous variables were presented as mean±SD. Categorical variables were expressed as counts (percentage). Significance for intergroup differences was assessed by the chi-square test (or Fisher's exact test) for categorical variables and the Mann-Whitney U test for continuous variables (except AUC). The Spearman's rank-order correlation coefficient test was used to analyze the correlations between continuous variables. Multivariate analysis using forward stepwise logistic regression determined predictors of 1-week mortality of patients. Variables were introduced into the logistic model if significant difference was shown by the univariate analysis. A receiver operating characteristic curve (ROC curve) identified the CSF and plasma S100B cutoff levels that predicted the 1-week mortality. Under the ROC curve, z statistical analysis was made to compare the AUCs of the plasma and CSF S100B levels with those of GCS scores and ICH volumes for the 1-week mortality. A P value of less than 0.05 was considered statistically significant.

RESULTS

Characteristics of patients

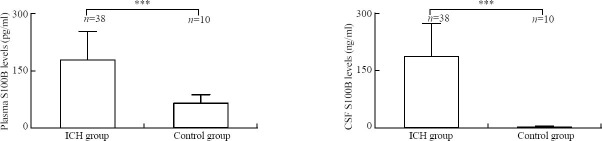

In the 38 patients, 29 were men and 9 women, aged on average 64.5±11.0 years (range, 42-80 years). In this series 15 patients (39.5%) died of ICH in a week. Thirty-five patients (92.1%) presented with hypertension, and 10 patients (26.3%) suffered from diabetes mellitus. The mean admission time was 2.1±1.5 hours (range, 0.3- 6 hours). On admission, the mean arterial pressure was 128.4±20.3 mmHg (range, 87.7-163.0 mm Hg), the mean GCS score was 8.0±2.5 (range, 5-13), and the mean ICH volume was 51.4±17.6 ml (range, 20-80 ml). Twenty-seven patients (71.1%) were complicated with IVH and 18 patients (47.4%) complicated with hydrocephalus. Surgical procedures included evacuation of hematoma (35 patients, 92.1%), external decompression (19 patients, 50.0%), and external ventricular drainage (19 patients, 50.0%). The mean time for surgery was 3.3±1.8 hours (range, 1.2-8.5 hours). Altogether 38 CSF samples and 38 plasma samples were collected (Table 1).

Table 1.

Comparison of survival and non-survival groups based on patient demographics and neurological conditions

Mortality prediction

There was significant difference in patients with diabetes mellitus between survivors and non-survivors

in the ICU (P=0.002). GCS score on admission was significantly different (P=0.000) between the 2 groups. The results of brain CT on admission were statistically different in ICH volume (P=0.000) in the presence of IVH (P=0.014) and hydrocephalus (P=0.010) between the 2 groups. The proportion of patients who received mechanical ventilation was higher in the non-survival group than that in the survival group (P=0.000). In the non-survival group, more patients underwent external decompression (P=0.000) and external ventricular drainage (P=0.003). CSF was collected by puncturing of the ventricles in the survival group (P=0.000) and by ventricular drainage with catheters in the non-survival group (P=0.003) (Table 1).

When the above variables found to be significant by the univariate analysis were introduced into a logistic model, only GCS score (odds ratio=0.426, 95% CI =0.253-0.718, P=0.001) was statistically significant after forward stepwise logistic regression analysis probably because of a small number of patients studied in the present study.

Blood glucose level was significantly lower in the survival group than in the non-survival group on admission (P=0.005) (Table 2). Because only blood glucose level was significantly different, all variables for the univariate analysis were introduced into a logistic model. Blood glucose level (odds ratio 1.343, 95% CI=1.055-1.708, P=0.017) was significantly different after forward stepwise logistic regression analysis.

Table 2.

Comparison of the survival and non-survival groups based on admission data

Changes in plasma and CSF S100B levels of ICH and control groups

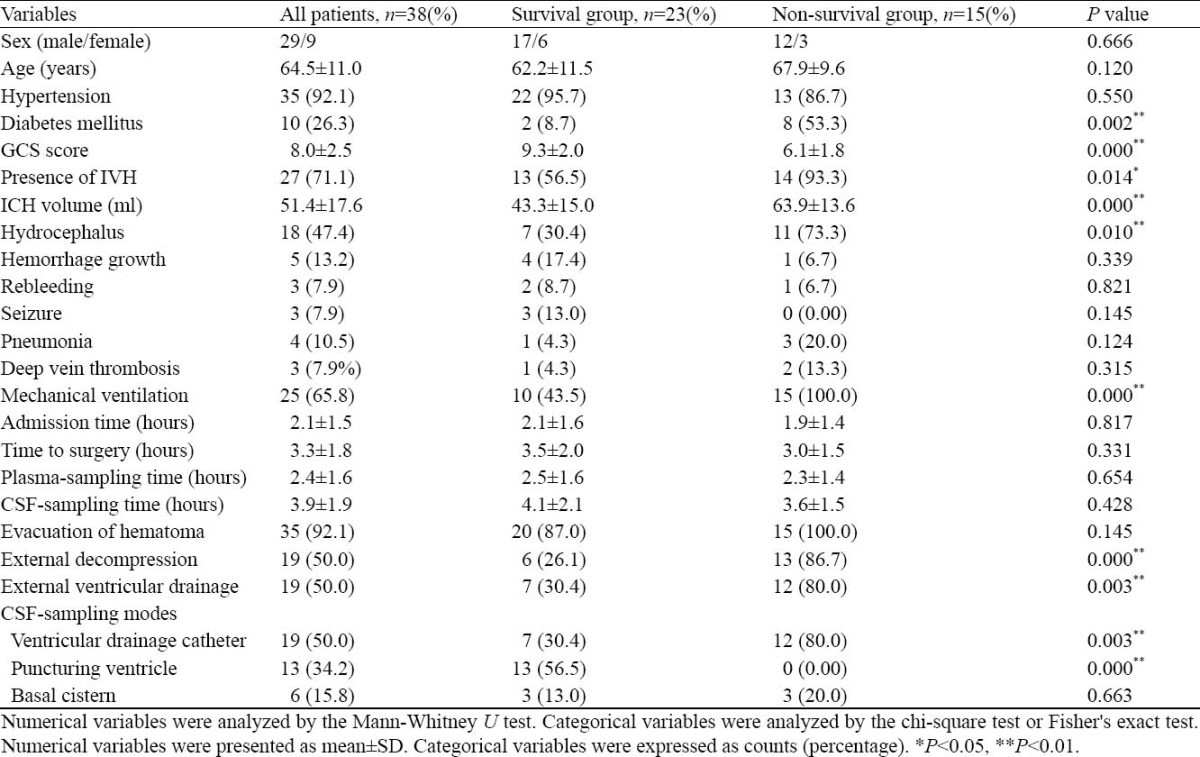

The Mann-Whitney U test showed that the plasma S100B level was significantly higher in the ICH group than in the control group (178.7±74.2 versus 63.2±23.0 pg/ml, P<0.001), and the CSF S100B level was significantly higher in the ICH group than in the control group (158.1±70.9 versus 1.8±0.7 ng/ml, P<0.001) (Figure 1).

Figure 1.

Comparison of the levels of S100B between the ICH group and control group using the Mann-Whitney U test. ***P<0.001, bar=standard deviation.

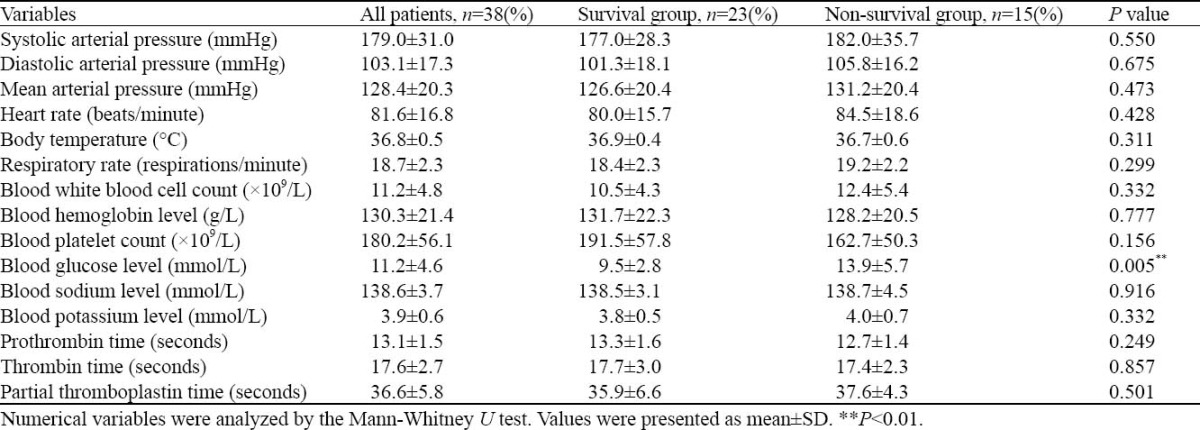

Changes in plasma and CSF S100B levels of non-survivors and survivors after ICH

The Mann-Whitney U test revealed that the plasma S100B level was significantly higher in the non-survival group than in the survival group (227.2±68.2 versus 147.0±60.5 pg/ml, P=0.001), and the CSF S100B level was significantly higher in the non-survival group than in the survival group (209.2±68.9 versus 124.8±50.0 ng/ml, P<0.001) (Figure 2).

Figure 2.

Comparison of the levels of S100B between the survival group and non-survival group after ICH using the Mann-Whitney U test. **P<0.01; ***P<0.001; bar=standard deviation.

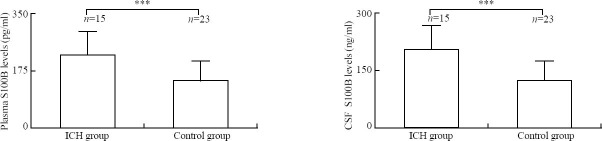

Changes in plasma and CSF S100B levels of IVH patients and non-IVH patients after ICH

The Mann-Whitney U test showed that the plasma S100B level was significantly higher in the IVH group than in the non-IVH group (195.7±70.9 versus 137.0±67.8 pg/ml, P=0.023), and the CSF S100B level was significantly higher in the IVH group than in the non-IVH group (174.8±72.2 versus 117.1±49.5 ng/ml, P=0.021) (Figure 3).

Figure 3.

Comparison of the levels of S100B between the non-IVH group and IVH group after ICH using the Mann-Whitney U test. *P<0.05; bar=standard deviation.

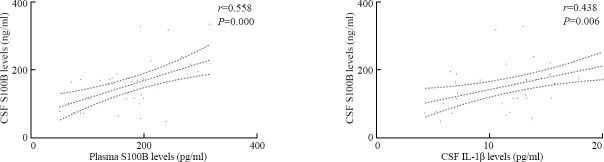

Relationships between CSF S100B levels and levels of S100B in plasma and IL-1β in CSF after ICH

Spearman's rank-order correlation coefficient analysis revealed that there were significant correlations between CSF S100B levels and plasma S100B levels (r=0.558, P<0.001), and between CSF S100B levels and CSF IL-1β levels (12.3±4.7 pg/ml) (r=0.438, P=0.006) (Figure 4).

Figure 4.

Correlations between CSF S100B levels and levels of S100B in plasma and IL-1β in CSF after ICH using Spearman's rank-order correlation coefficient analysis.

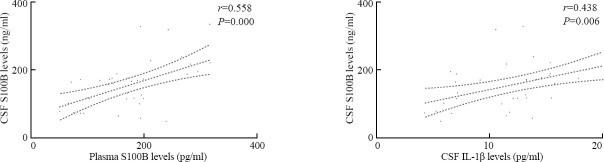

Relationships between GCS scores and levels of S100B in plasma and CSF after ICH

Spearman's rank-order correlation coefficient analysis showed that there were significant correlations between GCS scores and plasma S100B levels (r=-0.451, P=0.004) and between GCS scores and CSF S100B levels (r=-0.508, P=0.001)(Figure 5).

Figure 5.

Correlations between GCS scores and levels of S100B in plasma and CSF after ICH using Spearman's rank-order correlation coefficient analysis.

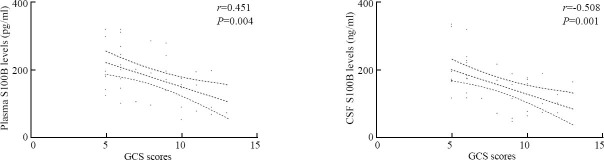

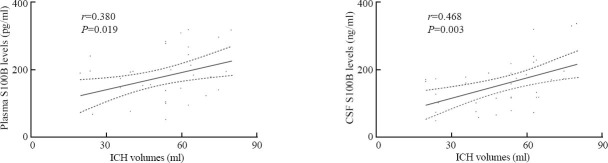

Relationships between ICH volumes and levels of S100B in plasma and CSF after ICH

Spearman's rank-order correlation coefficient analysis revealed that there were significant correlations between ICH volumes and plasma S100B levels (r=0.380, P=0.019) and between ICH volumes and CSF S100B levels (r=0.468, P=0.003)(Figure 6).

Figure 6.

Correlations between ICH volumes and levels of S100B in plasma and CSF after ICH using Spearman's rank-order correlation coefficient analysis.

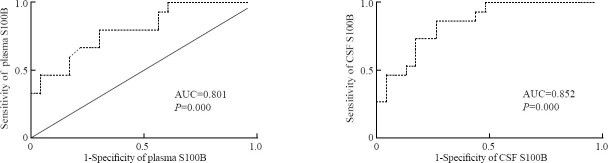

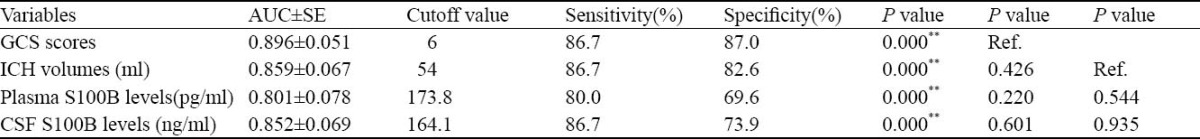

Predictive significances of plasma and CSF S100B for 1-week mortality of patients with ICH

The Z statistical analysis was made under the receiver operating curve (ROC). A ROC curve identified plasma and CSF S100B cutoff levels that predicted 1-week mortality of patients with a high sensitivity and specificity. The areas under curves (AUCs) of GCS scores and ICH volumes were larger than those of CSF and plasma S100B levels, but the differences were not statistically significant (P>0.05) (Figure 7, Table 3).

Figure 7.

Receiver operating characteristic curve analysis using Z statistical analysis

Table 3.

Comparison of receiver operating characteristic curves using z statistical analysis

DISCUSSION

Spontaneous ICH is a common fatal subtype of stroke.[20, 22] A low GCS score, a large ICH volume, and the presence of IVH on the initial brain CT are consistent predictors of mortality.[20,23-25] In this study, however, forward stepwise logistic regression analysis demonstrated only a low GCS score followed by a poor outcome. This distinction may be due to the small sample size in this study. The outcome of ICH is determined by both the initial impact and the subsequent secondary injury, with a complex cascade of inflammatory processes, in which cytokines are involved. Anti- and pro-inflammatory cytokines play a part in almost every step of inflammatory reactions.[7,26-29] Pro-inflammatory cytokine IL-1β induces systematically the acute phase response in the central nervous system, and is involved in brain injury after ICH.[7,28]

Increasing evidence has suggested that implicated in the Ca2+-dependent regulation of intracellular activities, S100B, a member of the multigenic family of EF-hand type Ca2+-binding proteins, also has extracellular regulatory roles.[1, 30] The brain is the richest source of S100B, and astrocytes are of the brain cell type with the highest expression of protein and release of S100B constitutively.[1] Moreover, agents such as serotonin agonists, glutamates and lysophosphatidic acids may increase the release of S100B by astrocytes,[31-33] suggesting that S100B release is one mechanism by which astrocytes communicate with neurons and/or alter neuronal and microglial function.

Extracellular effects of S100B in the brain have attracted much attention from researchers because of its elevated expression in pathological conditions of the brain.[34-37] There is considerable evidence that S100B acts as a neurotrophic and neuronal survival protein in the development of the nervous system.[38] However, S100B can be neurotoxic according to its concentration. In cell cultures, the high concentration of S100B can induce neuronal death through release of nitric oxide from astrocytes.[3] S100B can also induce proinflammatory cytokines.[39, 40] In S100B transgenic mice, overexpression of S100B was found to cause greater cerebral injury and mortality as glial activation and neuroinflammation.[41] Specifically, S100B upregulates the expression of IL-1β via ERK1/2, JNK and p38 MAPK activation in primary microglia[2], and conversely, IL-1β induces the secretion of S100B involving the MARK pathway and NF-kB signaling in astrocytes.[42] Moreover, some in vitro data indicate a cross-talk between S100B and IL-1β, up-regulating each other.[5] Experimental and clinical evidence has supported the hypothesis that a “cytokine cycle” involves S100B and IL-1β in Alzheimer's disease.[43] Recent proteomic analyses of spinal cord injury have defined S100B as a pro-inflammatory cytokine.[44] In the present study significant elevated levels of CSF S100B were found to be related to CSF IL-1β levels in ICH patients. These findings suggest that extracellular S100B could be involved in the inflammatory response to brain injury after ICH.

The S100B level in peripheral blood is elevated in patients with disorders of the central nervous system like ischemic stroke, subarachnoid hemorrhage and traumatic brain injury.[34-37] The changes of peripheral S100B concentrations after intracerebral hemorrhage have been studied in patients and experimental animal models. Studies[6,8] including the present study found elevated levels of S100B in peripheral blood after ICH. The underlying mechanisms of the increased S100B level in peripheral blood have been investigated. Studies have suggested that S100B secretes increasingly from disrupted and/or activated glial cells into cerebrospinal fluid and subsequently leaks into the blood stream through the damaged blood-brain barrier.[9, 10] The S100B level in peripheral blood mainly reflects blood-brain barrier dysfunction and is not necessarily related to brain lesions.[45, 46] Diehl et al[11] reported that the serum S100B level was not always correlated with the cerebrospinal S100B level in a rat model of post-traumatic stress disorder, suggesting an extracerebral origin of peripheral blood S100B. In a rat model of ischemic stroke, the S100B level of peripheral blood was strongly correlated with the cerebrospinal S100B level.[47] In this study, we found that the peripheral S100B level was strongly correlated with the cerebrospinal S100B level in patients with ICH, indicating the increase of peripheral S100B reflects brain injury after ICH, and serum S100B may leak from the central nervous system into the peripheral blood stream through the disrupted blood-brain barrier.

S100B is a brain-specific protein that releases into peripheral blood and cerebral spinal fluid within a few hours after disease onset. S100B is often recognized as a promising biomarker for central nervous system disorders such as ischemic stroke, traumatic brain injury, and subarachnoid hemorrhage.[34-37] Moreover, the S100B level in peripheral blood has been reported to be associated with clotting volume and to predict unfavourable outcome after acute spontaneous ICH.[8] In the present study S100B levels were enhanced both in CSF and blood. S100B levels were highly associated with GCS score, ICH volume, presence of IVH, and survival rate in ICH patients. A ROC curve identified plasma and CSF S100B cutoff levels that predicted 1-week mortality of patients, with a high sensitivity and specificity. Areas under curves of GCS scores and ICH volumes were larger than those of CSF and plasma S100B levels, but the differences were not statistically significant.

In conclusion, the high levels of S100B are present in the cerebrospinal fluid and pheripheral blood of patients with ICH and may contribute to the inflammatory processes of ICH. The levels of CSF and plasma S100B after spontaneous onset of ICH seem to correlate with clinical outcome in these patients. Increased peripheral S100B level properly reflects brain injury, and plasma S100B levels can serve as a useful clinical marker for evaluating the prognosis of ICH. The present study is monocentric and has the inherent limitations of any small sample size. Consequently, the conclusions in this study remain to be verified.

ACKNOWLEDGEMENT

The authors thank the staff of the central laboratory of the First Hangzhou Municipal People's Hospital for their technical support.

Footnotes

Funding: This work was financially supported by grant from Hangzhou Health Bureau (2006B005).

Ethical approval: The study was approved by the institutional ethics committee.

Competing interest: The authors declare that there are no competing interests involving the study.

Contributors: MH and XQD contributed equally to the manuscript. MH, XQD and YYH contributed to the design of the study and drafted the manuscript. XQD, WHY and ZYZ enrolled the patients. XQD and YYH contributed to data analysis and interpretation of the results. All authors read and approved the final version.

REFERENCES

- 1.Donato R. S100: a multigenic family of calcium-modulated proteins of the EF-hand type with intracellular and extracellular functional roles. Int J Biochem Cell Biol. 2001;33:637–668. doi: 10.1016/s1357-2725(01)00046-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Bianchi R, Giambanco I, Donato R. S100B/RAGE-dependent activation of microglia via NF-kappaB and AP-1 Co-regulation of COX-2 expression by S100B, IL-1beta and TNF-alpha. Neurobiol Aging. 2010;31:665–677. doi: 10.1016/j.neurobiolaging.2008.05.017. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Hu J, Castets F, Guevara JL, Van Eldik LJ. S100β stimulates inducible nitric oxide synthase activity and mRNA levels in rat cortical astrocytes. J Biol Chem. 1996;271:2543–2547. doi: 10.1074/jbc.271.5.2543. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Kim SH, Smith CJ, Van Eldik LJ. Importance of MAPK pathways for microglial pro-inflammatory cytokine IL-1 beta production. Neurobiol Aging. 2004;25:431–439. doi: 10.1016/S0197-4580(03)00126-X. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Liu L, Li Y, Van Eldik LJ, Griffin WS, Barger SW. S100Binduced microglial and neuronal IL-1 expression is mediated by cell type-specific transcription factors. J Neurochem. 2005;92:546–553. doi: 10.1111/j.1471-4159.2004.02909.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Tanaka Y, Marumo T, Shibuta H, Omura T, Yoshida S. Serum S100B, brain edema, and hematoma formation in a rat model of collagenase-induced hemorrhagic stroke. Brain Res Bull. 2009;78:158–163. doi: 10.1016/j.brainresbull.2008.10.012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Holmin S, Mathiese T. Intracerebral administration of interleukin-1β and induction of inflammation, apoptosis and vasogenic edema. J Neurosurg. 2000;92:108–120. doi: 10.3171/jns.2000.92.1.0108. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Delgado P, Alvarez Sabin J, Santamarina E, Molina CA, Quintana M, Rosell A, et al. Plasma S100B level after acute spontaneous intracerebral hemorrhage. Stroke. 2006;37:2837–2839. doi: 10.1161/01.STR.0000245085.58807.ad. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Tanaka Y, Koizumi C, Marumo T, Omura T, Yoshida S. Serum S100B indicates brain edema formation and predicts long-term neurological outcomes in rat transient middle cerebral artery occlusion model. Brain Res. 2007;1137:140–145. doi: 10.1016/j.brainres.2006.12.025. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Tanaka Y, Marumo T, Omura T, Yoshida S. Serum S100B indicates successful combination treatment with recombinant tissue plasminogen activator and MK-801 in a rat model of embolic stroke. Brain Res. 2007;1154:194–199. doi: 10.1016/j.brainres.2007.03.085. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Diehl LA, Silveira PP, Leite MC, Crema LM, Portella AK, Billodre MN, et al. Long-lasting sex-specific effects upon behavior and S100b levels after maternal separation and exposure to a model of post-traumatic stress disorder in rats. Brain Res. 2007;1144:107–116. doi: 10.1016/j.brainres.2007.01.084. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Inagawa T. Recurrent primary intracerebral hemorrhage in Izumo city, Japan. Surg Neurol. 2005;64:28–36. doi: 10.1016/j.surneu.2004.09.039. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Inagawa T, Ohbayashi N, Takechi A, Shibukawa M, Yahara K. Primary intracerebral hemorrhage in Izumo city, Japan: incidence rates and outcome in relation to the site of hemorrhage. Neurosurgery. 2003;53:1283–1298. doi: 10.1227/01.neu.0000093825.04365.f3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Kothari RU, Brott T, Broderick JP, Barsan WG, Sauerbeck LR, Zuccarello M, et al. The ABCs of measuring intracerebral hemorrhage volumes. Stroke. 1996;27:1304–1305. doi: 10.1161/01.str.27.8.1304. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Brott T, Broderick J, Kothari R, Barsan W, Tomsick T, Sauerbeck L, et al. Early hemorrhage growth in patients with intracerebral hemorrhage. Stroke. 1997;28:1–5. doi: 10.1161/01.str.28.1.1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Morgenstern LB, Demchuk AM, Kim DH, Frankowski RH, Grotta JC. Rebleeding leads to poor outcome in ultra-early craniotomy for intracerebral hemorrhage. Neurology. 2001;56:1294–12950. doi: 10.1212/wnl.56.10.1294. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Grotta J, Pasteur W, Khwaja G, Hamel T, Fisher M, Ramirez A. Elective intubation for neurological deterioration after stroke. Neurology. 1995;45:640–644. doi: 10.1212/wnl.45.4.640. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Gujjar AR, Deibert E, Manno EM, Duff S, Diringer MN. Mechanical ventilation for ischemic stroke and intracerebral hemorrhage: indications, timing, and outcome. Neurology. 1998;51:447–451. doi: 10.1212/wnl.51.2.447. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Steiner T, Mendoza G, Georgia MD, Schellinger P, Holle R, Hacke W. Prognosis of stroke patients requiring mechanical ventilation in a neurological critical care unit. Stroke. 1997;28:711–715. doi: 10.1161/01.str.28.4.711. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Butcher K, Laidlaw J. Current intracerebral haemorrhage management. J Clin Neurosci. 2003;10:158–167. doi: 10.1016/s0967-5868(02)00324-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Diringer MN. Intracerebral hemorrhage: pathophysiology and management. Crit Care Med. 1993;21:1591–1603. doi: 10.1097/00003246-199310000-00032. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Sutherland GR, Auer RN. Primary intracerebral hemorrhage. J Clin Neurosci. 2006;13:511–517. doi: 10.1016/j.jocn.2004.12.012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Broderick JP, Brott TG, Duldner JE, Tomsick T, Huster G. Volume of intracerebral hemorrhage: a powerful and easy-to-use predictor of 30-day mortality. Stroke. 1993;24:987–993. doi: 10.1161/01.str.24.7.987. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Hemphill JC, 3rd, Bonovich DC, Besmertis L, Manley GT, Johnston SC. The ICH score: a simple, reliable grading scale for intracerebral hemorrhage. Stroke. 2001;32:891–897. doi: 10.1161/01.str.32.4.891. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Shaya M, Dubey A, Berk C, Gonzalez-Toledo E, Zhang J, Caldito G, et al. Factors influencing outcome in intracerebral hematoma: a simple, reliable, and accurate method to grade intracerebral hemorrhage. Surg Neurol. 2005;63:343–348. doi: 10.1016/j.surneu.2004.06.019. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Abbott N. Inflammatory mediators and modulation of blood-brain barrier permeability. Cell Mol Neurobiol. 2000;20:131–147. doi: 10.1023/A:1007074420772. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Hua Y, Wu J, Keep RF, Nakamura T, Hoff JT, Xi G. Tumor necrosis factor-alpha increases in the brain after intracerebral hemorrhage and thrombin stimulation. Neurosurgery. 2006;58:542–550. doi: 10.1227/01.NEU.0000197333.55473.AD. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Simi A, Tsakiri N, Wang P, Rothwell NJ. Interleukin-1 and inflammatory neurodegeneration. Biochem Soc Trans. 2007;35:1122–1226. doi: 10.1042/BST0351122. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Zhang X, Li H, Hu S, Zhang L, Liu C, Zhu C, et al. Brain edema after intracerebral hemorrhage in rats: the role of inflammation. Neurol India. 2006;54:402–407. doi: 10.4103/0028-3886.28115. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Van Eldik LJ, Wainwright MS. The Janus face of glial-derived S100B: beneficial and detrimental functions in the brain. Restor Neurol Neurosci. 2003;21:97–108. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Ciccarelli R, Di Iorio P, Bruno V, Battaglia G, D’Alimonte I, D’Onofrio M, et al. Activation of A(1) adenosine or mGlu3 metabotropic glutamate receptors enhances the release of nerve growth factor and S-100beta protein from cultured astrocytes. Glia. 1999;27:275–281. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Pinto SS, Gottfried C, Mendez A, Gonçalves D, Karl J, Gonçalves CA, et al. Immunocontent and secretion of S100B in astrocyte cultures from different brain regions in relation to morphology. FEBS Lett. 2000;486:203–207. doi: 10.1016/s0014-5793(00)02301-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Whitaker-Azmitia PM, Murphy R, Azmitia EC. Stimulation of astroglial 5-HT1A receptors releases the serotonergic growth factor, protein S-100, and alters astroglial morphology. Brain Res. 1990;528:155–158. doi: 10.1016/0006-8993(90)90210-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Hayakata T, Shiozaki T, Tasaki O, Ikegawa H, Inoue Y, Toshiyuki F, et al. Changes in CSF, S100B and cytokine concentrations in early-phase severe traumatic brain injury. Shock. 2004;22:102–107. doi: 10.1097/01.shk.0000131193.80038.f1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Lynch JR, Blessing R, White WD, Grocott HP, Newman MF, Laskowitz DT. Novel diagnostic test for acute stroke. Stroke. 2004;35:57–63. doi: 10.1161/01.STR.0000105927.62344.4C. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Sanchez-Peña P, Pereira AR, Sourour NA, Biondi A, Lejean L, Colonne C, et al. S100B as an additional prognostic marker in subarachnoid aneurysmal hemorrhage. Crit Care Med. 2008;36:2267–2273. doi: 10.1097/CCM.0b013e3181809750. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Townend WJ, Guy MJ, Pani MA, Martin B, Yates DW. Head injury outcome prediction in the emergency department: a role for protein S-100B? J Neurol Neurosurg Psychiatry. 2002;73:542–546. doi: 10.1136/jnnp.73.5.542. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Donato R, Sorci G, Riuzzi F, Arcuri C, Bianchi R, Brozzi F, et al. S100B's double life: Intracellular regulator and extracellular signal. Biochim Biophys Acta. 2009;1793:1008–1022. doi: 10.1016/j.bbamcr.2008.11.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Hu J, Van Eldik LJ. Glial-derived proteins activate cultured astrocytes and enhance beta amyloid-induced glial activation. Brain Res. 1999;842:46–54. doi: 10.1016/s0006-8993(99)01804-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Ponath G, Schettler C, Kaestner F, Voigt B, Wentker D, Arolt V, et al. Autocrine S100B effects on astrocytes are mediated, via RAGE. J Neuroimmunol. 2007;184:214–222. doi: 10.1016/j.jneuroim.2006.12.011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Mori T, Tan J, Arendash GW, Koyama N, Nojima Y, Town T. Overexpression of human S100B exacerbates brain damage and periinfarct gliosis after permanent focal ischemia. Stroke. 2008;39:2114–2121. doi: 10.1161/STROKEAHA.107.503821. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.De Souza DF, Leite MC, Quincozes-Santos A, Nardin P, Tortorelli LS, Rigo MM, et al. S100B secretion is stimulated by IL-1beta in glial cultures and hippocampal slices of rats: Likely involvement of MAPK pathway. J Neuroimmunol. 2009;206:5257. doi: 10.1016/j.jneuroim.2008.10.012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Griffin WS, Sheng JG, Royston MC, Gentleman SM, McKenzie JE, Graham DI, et al. Glial-neuronal interactions in Alzheimer's disease: the potential role of a ‘cytokine cycle’ in disease progression. Brain Pathol. 1998;8:65–72. doi: 10.1111/j.1750-3639.1998.tb00136.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Tsai MC, Shen LF, Kuo HS, Cheng H, Chak KF. Involvement of acidic fibroblast growth factor in spinal cord injury repair processes revealed by a proteomics approach. Mol Cell Proteomics. 2008;7:1668–1687. doi: 10.1074/mcp.M800076-MCP200. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Kanner AA, Marchi N, Fazio V, Mayberg MR, Koltz MT, Siomin V, et al. Serum S100 beta: a noninvasive marker of blood-brain barrier function and brain lesions. Cancer. 2003;97:2806–2813. doi: 10.1002/cncr.11409. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Kapural M, Krizanac-Bengez Lj, Barnett G, Perl J, Masaryk T, Apollo D, et al. Serum S-100 beta as a possible marker of blood-brain barrier disruption. Brain Res. 2002;940:102–104. doi: 10.1016/s0006-8993(02)02586-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Tanaka Y, Marumo T, Omura T, Yoshida S. Relationship between cerebrospinal and peripheral S100B levels after focal cerebral ischemia in rats. Neurosci Lett. 2008;436:40–43. doi: 10.1016/j.neulet.2008.02.056. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]