Abstract

BACKGROUND:

Low tidal volume mechanical ventilation is difficult to correct hypoxemia, and prolonged inhalation of pure oxygen can lead to oxygen poisoning. We suggest that continuous tracheal gas insufflation (TGI) during protective mechanical ventilation could improve cardiopulmonary function in acute lung injury.

METHODS:

Totally 12 healthy juvenile piglets were anesthetized and mechanically ventilated at PEEP of 2 cmH2O with a peak inspiratory pressure of 10 cmH2O. The piglets were challenged with lipopolysaccharide and randomly assigned into two groups (n=6 each group): mechanical ventilation (MV) alone and TGI with continuous airway flow 2 l/min. FIO2 was set at 0.4 to avoid oxygen toxicity and continuously monitored with an oxygen analyzer.

RESULTS:

Tidal volume, ventilation efficacy index and mean airway resistant pressure were significantly improved in the TGI group (P<0.01 or P<0.05). At 4 hours post ALI, pH decreased to below 7.20 in the MV group, and improved in the TGI group (P<0.01). Similarly, PaCO2 was stable and was significantly lower in the TGI group than in the MV group (P<0.01). PaO2 and PaO2/FIO2 increased also in the TGI group (P<0.05). There was no significant difference in heart rate, respiratory rate, mean artery pressure, central venous pressure, dynamic lung compliance and mean resistance of airway between the two groups. Lung histological examination showed reduced inflammation, reduced intra-alveolar and interstitial patchy hemorrhage, and homogenously expanded lungs in the TGI group.

CONCLUSION:

Continuous TGI during MV can significantly improve gas exchange and ventilation efficacy and may provide a better treatment for acute lung injury.

KEY WORDS: Acute lung injury, Tracheal gas insufflation, Lung protective strategy, Mechanical ventilation

INTRODUCTION

Tracheal gas insufflation (TGI) is a technique by which fresh gas is introduced into the trachea to reduce CO2 retention without changing the ventilator pipe cases. It is a useful adjunct to conventional mechanical ventilation (MV) in animal models and in patients with acute lung injury (ALI) and acute respiratory distress syndrome (ARDS); the most severe stage of ALI)[1-3] as well as in preterm infants with hyaline membrane disease.[4] When combined with MV, TGI can effectively improve ventilation by reducing the dead space of the patient-ventilator system, ventilation pressures, and tidal volumes, and by promoting CO2 elimination. TGI can also improve oxygenation. [5,6] Studies[7-9] have also shown that tracheal gas insufflation with oxygen can improve exercise tolerance, reduce respiratory work and dyspnea.

Although ALI is often related to endotoxin, few studies have investigated endotoxin-induced ALI in large animals, and mostly the experiments used deep anesthesia and pure oxygen inhaled which are not recommened clinically. In the current study, Juvenile piglets were chosen (a species similar to humans) as a model to study endotoxin-induced ALI. Pressure control mode was used and oxygen concentration inhaled was kept nearly 40% throughout the study, which were consistent with the actual clinical practices. We tested the hypothesis that assisting TGI during MV with protective strategy would avoid ventilator-associated injury, offset diffusional issues, and remove CO2.

METHODS

Animal preparation and measurements

Twelve juvenile piglets (4-6 kg, 4-6 wk, either sex, purchased from the Gaoqiao Experimental Animal Farm, Jiading District,Shanghai,China) were used to study LPS-induced ALI. All experimental procedures were approved by the Institutional Animal Care Committee of Tongji University. The piglets were anesthetized with ketamine (30 mg/kg i.m., followed by i.v. infusion at 5-8 mg/kg per hour). The anterior neck was dissected, tracheostomized, and placed with a cuffed endotracheal tube (ETT, 4.5 mm internal diameter, Taizhou Kechuang Medical Product Co., Ltd, China). After catheterization of the femoral artery and jugular vein, arterial and central venous pressures were continuously measured (Hewlett Packard, Viridia 24C, Germany). O2 saturation (Pulse Oximetry) and electrocardiogram were also monitored.

Airway resistance (Raw) and dynamic lung compliance (Cdyn) were measured by pneumotachography with a graphic monitor (NewPort Navigator GM-250, NMI Newport Medical Instruments, Inc, USA). Lactated Ringer's solution was infused at 10 ml/kg per hour. After stabilization, arterial blood chemistry (ABL 700, Radiometer, Copenhagen, Denmark), lung mechanics, central venous pressure, and baseline vital signs were recorded. Ventilation efficacy index (VEI) was calculated according to the following equation: VEI=3800/[respiratory rate×(PIP - PEEP)×PaCO2 (mmHg)].[10]

Experimental protocols

Lung injury was induced by continuous instillation of lipopolysaccharide (LPS, O111: B4, L4391, Sigma) into the lungs at 60 μg/kg for 2 hours. ALI was defined as Pa02/FIO2<300 and Cdyn <70% of baseline. To avoid ventilator-associated injury, mechanical ventilation was set at 2 cmH20 PEEP in a pressure-triggered (1.0 cmH2O sensitivity) flow control mode at 20 L/min flow, 10 cmH2O PIP and time cycled setting at 0.4 second for inspiration and backup breathing frequency of 30 cycles/ min (Newport E200, USA). FI02 was set at 0.4 to avoid oxygen toxicity and continuously monitored with an oxygen analyzer (MAX02, USA). Then, animals were randomly assigned to two groups (n=6 each group):MV alone (control): ventilator settings were maintained throughout the experiment; and TGI: air insufflation rate was maintained at 2 l/min during MV through a pediatric gastric tube (inner diameter, 1.0 mm; outer diameter, 1.8 mm) placed through the tracheal stoma. Experimental variables were recorded and assessed every 30 minutes for 4 hours after initial lung injury.

Lung histology

The piglets were euthanized with an overdose of potassium chloride 4 hours after ALI. With the ventilator cycling, the chest was opened for gross inspection of lung injury. Then, the left atrium was dissected and the lungs were perfused via the pulmonary arteries with cold 10% formaldehyde buffer at 60 cmH2O until the effluent ran clear (about 30 minutes). Lung samples were placed in 10% buffered formalin for subsequent paraffin embedding, sectioning, and staining (hematoxylin and eosin). Lung histology was examined under a light microscope by a histopathologist (Wang JC), who was blind to the experiments. A lung injury score was used to quantify microscopic changes.[11, 12] Seven aspects (edema, alveolar and interstitial inflammation, alveolar and interstitial hemorrhage, atelectasis, and necrosis) were each scored on a 5-grade scale: 0, no injury; 1, injury in 25% of the field; 2, injury in 50% of the field; 3, injury in 75% of the field; and 4, injury throughout the field. The highest and lowest possible scores were 28 and 0.

Data analysis

All values were expressed as means ± SD. Pre- and post-injury data (ALI, 1, 2 and 4 hours) were evaluated with two-way repeated-measures ANOVA, followed by Tukey's multiple-comparison test (SPSS 15.0) to determine significance of differences between the groups. The differences in histological scores between the groups were assessed by the Kruskal-Wallis test followed by the Student-Newman-Keuls test. Significance was set at P<0.05.

RESULTS

A mean of 9.1±0.4 hours (range 7-11 hours) was required to reach ALI following the LPS instillation. When the animals reached ALI, their heart rate and respiratory rate increased whereas their mean arterial pressure decreased (all P<0.05 or 0.01). However, the central venous pressure, cardiac output and systemic vascular resistance remained stable (Table 1). LPS instillation also decreased Cdyn and VT and increased the mean airway resistant pressure (Paw) and mean Raw (all P<0.05) (Table 2). PaO2/FIO2 was significantly decreased, and pH value and PaCO2 only changed slightly (Figure 1). There were no significant differences in these variables in the two groups at baseline or at onset of ALI.

Table 1.

Vital signs and CVP in both groups (mean±SD, n=6)

Table 2.

Variables of arterial blood gas analysis in both groups (mean±SD, n=6)

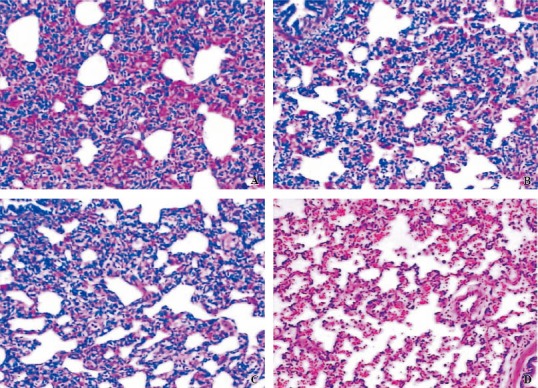

Figure 1.

Typical photomicrographs (original magnification ×100) of lung sections stained with hematoxylin and eosin for both TGI and MV groups 4 hours after injury: A: dependent region for MV; B: non-dependent region for MV; C:dependent region for TGI; D: non-dependent region for TGI. The damage in both dependent and non-dependent sites was significantly reduced after TGI.

Comparisons of vital signs and central venous pressure

Table 1 summarizes the data of vital signs and CVP. Four hours after ALI induction, the heart rate decreased gradually from 186 beats/min to 169 beats/min (P<0.01) in the TGI group, but there was no significant difference between the two groups. The respiratory rate remained stable in both groups during a 4-hour treatment. MAP in the TGI group was higher at 4 hours after ALI induction (P<0.05), but there was no significant difference compared with the MV group. Nor significant difference was observed in CVP in both groups.

Comparisons of blood gas analysis

PH, PaO2, and PaO2/FIO2 in the MV group continued to decline, pH from 7.315 to 7.15±0.12, Pa02 from 104 mmHg to 74 mmHg, Pa02/FIO2 from 259 to 184 whereas PaC02 was increased from 48.2 mmHg to 66.8 mmHg at 4 hours (Table 2). PH was improved and significantly higher in the TGI group than the MV group (P<0.01). PaO2 and PaO2/FI0 2 in the TGI group decreased slightly during 1 hour after ALI induction, but they increased gradually since then and were significantly higher than in the MV group (P<0.05). PaC02 was significantly lower since 1 hour in the TGI group than in the MV group and remained relatively stable (P<0.05 or 0.01).

Comparisons of ventilatory function and respiratory mechanics

Expiratory tidal volume in the TGI group was significantly higher since 1 hour than in the MV group. VEI in the TGI group increased from 0.15 at ALI to 0.20 at 4 hours (P<0.05), and was significantly higher than in the MV group (P<0.01) (Table 3). The mean airway resistant pressure in the TGI group at 4 hours was lower than that in the MV group (P<0.05). But the lung compliance and airway resistance between the two groups were not significantly different.

Table 3.

Variables of ventilation function and respiratory mechanics in both groups (mean±SD, n=6)

Histology and global lung injury scores

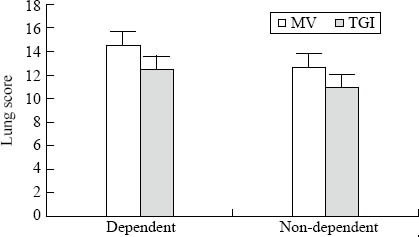

Grossly, the lungs appeared dark red, water abundant, atelectatic and hemorrhagic in the MV group, especially in the dependent regions. In the TGI group, the gross lesions were less severe. Figure 1 illustrates the lung histopathology of dependent and non-dependent regions from the two groups. Intra-alveolar and interstitial inflammation and hemorrhage, atelectasis, edema, and exudation were severe, especially in the dependent regions in the MV group. Lung damage was less in the TGI group. Semi-quantitative evaluation by the global lung injury score also demonstrated that TGI treatment improved lung damage (Figure 2; F=7.253, P=0.013).

Figure 2.

Regional lung injury scores for mechanical ventilation (MV) and continuous tracheal gas insufflation (TGI). Values are expressed as mean±SD. *P<0.05 versus the MV group.

DISCUSSION

ALI and ARDS are progressive respiratory failures caused by various intra- and extra-pulmonary pathogenic disorders. Their common causes include infection, aspiration, trauma, drug overdose, among others.[13,14] Clinically, sepsis or endotoxin-induced ALI often worsens despite of the use of antibiotics. Mechanical ventilation is the cornerstone of supportive therapy.[15] With the strategy of permissive hypercapnia (PHC) recommended, the mortality rate of ARDS/ALI has somewhat fallen, but remains high.[16,17] Low tidal volume mechanical ventilation is difficult to correct hypoxemia, and prolonged inhalation of pure oxygen can lead to oxygen poisoning. At the same time, PHC can also cause complications such as acidosis, increased intracranial pressure and pulmonary artery pressure, electrolyte imbalance, and others.

Tracheal gas insufflation is an adjunctive method during mechanical ventilation to reduce anatomic dead space and to facilitate CO2 elimination. This will concurrently decrease VT and peak inspiratory pressure, and thus minimize the ventilator-associated lung injury.[1-4,18,19] The main mechanism of TGI is to reduce the dead space ventilation and increase alveolar ventilation. [20, 21] Meanwhile, TGI can also promote oxygenation and increase PaO2.[15-17] TGI can be combined not only with conventional mechanical ventilation, but also with high-frequency oscillatory ventilation, partial liquid ventilation and so on, and the results were incentive.[22-24]

Zhu et al[25] found that in a rabbit model of acute lung injury, continuous TGI during MV by keeping PaCO2 stable around 35-45 mmHg significantly reduced peak airway pressure, tidal volume, the radio of dead space ventilation to tidal volume, and improve Cdyn and PaO2, while the total protein of lavage fluid, myeloperoxidase and interleukin -8 decreased. In the present study the method combining TGI with MV to treat ALI improved gas exchange and cardiopulmonary function. This can be verified by better outcomes including expiratory tidal volume, VEI, PaCO2, airway resistance pressure, PaO2, PaO2/FIO2, and lung histology in the TGI group.

In summary, our data show that TGI is better than MV in the treatment of LPS-induced ALI in piglets. This approach may offer an alternative lung protective strategy in sepsis-induced ALI and ARDS. Further experimental studies regarding the underlying mechanisms and clinical investigation are warranted.

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

We would like to thank Qi Yin and Jing-jing Lu from the Department of Respiratory Medicine, East Hospital Affiliated to Tongji University for their experimental assistance and valuable comments. This study was conducted at the Pediatrics Hospital, Fudan University, Shanghai.

Footnotes

Funding: The study was supported by a grant from Pudong New Area Science and Technology Commission, Shanghai, China (PKJ2009-Y18).

Ethical approval: None.

Competing interest: None.

Contributors: Guo ZL proposed and wrote the study. All authors contributed to the intellectual content and approved the final version.

REFERENCES

- 1.Faisy C, Guerot E, Diehl JL, Iftimovici E, Fagon JY. Clinically significant gastrointestinal bleeding in critically ill patients with and without stress-ulcer prophylaxis. Intensive Care Med. 2003;29:1306–1313. doi: 10.1007/s00134-003-1863-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Kantorova I, Svoboda P, Scheer P, Doubek J, Rehorkova D, Bosakova H, et al. Stress ulcer prophylaxis in critically ill patients: A randomized controlled trial. Hepatogastroenterology. 2004;51:757–761. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Miano TA, Reichert MG, Houle TT, MacGregor DA, Kincaid EH, Bowton DL. Nosocomial pneumonia risk and stress ulcer prophylaxis: a comparison of pantoprazole vs ranitidine in cardiothoracic surgery patients. Chest. 2009;136:440–447. doi: 10.1378/chest.08-1634. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Kahn JM, Doctor JN, Rubenfeld GD. Stress ulcer prophylaxis in mechanically ventilated patients: integrating evidence and judgment using a decision analysis. Intensive Care Med. 2006;32:1151–1158. doi: 10.1007/s00134-006-0244-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Hicks P, Cooper DJ, Webb S, Myburgh J, Seppelt I, Peake S, et al. Surviving Sepsis Campaign: international guidelines for management of severe sepsis and septic shock. Crit Care Med. 2008;36:296–327. doi: 10.1097/01.CCM.0000298158.12101.41. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Kantorova I, Svoboda P, Scheer P, Doubek J, Rehorkova D, Bosakova H, et al. Stress ulcer prophylaxis in critically ill patients: a randomized controlled trial. Hepatogastroenterology. 2004;51:757–761. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Lv ZY, Zhong NS. Internal Medicine. 7th Edition. Beijing: People's Medical Publishing House; 2008. [Google Scholar]

- 8.Knaus WA, Draper EA, Wagner DP, Zimmerman JE. APACHE II: a severity of disease classification system. Crit Care Med. 1985;13:818–825. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Marshall JC, Cook DJ, Christou NV, Bernard GR, Sprung CL, Sibbald WJ. Multiple organ dysfunction score: a reliable descriptor of a complex clinical outcome. Crit Care Med. 1995;23:1638–1652. doi: 10.1097/00003246-199510000-00007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Cook DJ, Reeve BK, Guyatt GH, Heyland DK, Griffith LE, Buckingham L. Stress ulcer prophylaxis in critically ill patients. Resolving discordant meta-analyses. JAMA. 2006;275:308–314. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.López-Herce J. Gastrointestinal complications in critically ill patients: what differs between adults and children? Curr Opin Clin Nutr Metab Care. 2009;12:180–185. doi: 10.1097/MCO.0b013e3283218285. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Duerksen DR. Stress-related mucosal disease in critically ill patients. Best Pract Res Clin Gastroenterol. 2003;17:327–344. doi: 10.1016/s1521-6918(03)00028-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Steinberg KP. Stress-related mucosal disease in the critically ill patient: Risk factors and strategies to prevent stress-related bleeding in the intensive care unit. Crit Care Med. 2002;30:S362–S364. doi: 10.1097/00003246-200206001-00005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Raff T, Germann G, Hartmann B. The value of early enteral nutrition in the prophylaxis of stress ulceration in the severely burned patient. Burns. 2007;23:313–318. doi: 10.1016/s0305-4179(97)89875-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Xie JX, Wu S, Kuang ZC. The comparison of early enteral and parenteral nutrition support in mechanical ventilation patients. Chin J Emerg Med. 2003;12:734–736. [Google Scholar]

- 16.Ali T, Harty RF. Stress-induced ulcer bleeding in critically ill patients. Gastroenterol Clin North Am. 2009;38:245–265. doi: 10.1016/j.gtc.2009.03.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Wahl WL, Arbabi S, Zalewski C, Wang SC, Hemmila MR. Intensive care unit core measures improve infectious complications in burn patients. J Burn Care Res. 2010;31:190–195. doi: 10.1097/BCR.0b013e3181c89f0b. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Janicki T, Stewart S. Stress-ulcer prophylaxis for general medical patients: a review of the evidence. J Hosp Med. 2007;2:86–92. doi: 10.1002/jhm.177. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Kantorova I, Svoboda P, Scheer P, Doubek J, Rehorkova D, Bosakova H, et al. Stress ulcer prophylaxis in critically ill patients: A randomized controlled trial. Hepatogastroenterology. 2004;51:757–761. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Faisy C, Guerot E, Diehl JL, Iftimovici E, Fagon JY. Clinically significant gastrointestinal bleeding in critically ill patients with and without stress ulcer prophylaxis. Intensive Care Med. 2003;29:1306–1313. doi: 10.1007/s00134-003-1863-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Gauvin F, Dugas MA, Chaïbou M, Morneau S, Lebel D, Lacroix J. The impact of clinically significant upper gastrointestinal bleeding acquired in a pediatric intensive care unit. Pediatr Crit Care Med. 2001;2:294–298. doi: 10.1097/00130478-200110000-00002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]