Abstract

BACKGROUND:

Acute kidney injury following percutaneous coronary intervention (PCI) is associated with a worse outcome. However, the risk factors and outcomes of acute kidney injury (AKI) in patients after intracoronary stent implantation are still unknown.

METHODS:

A retrospective case control study was done in 325 patients who underwent intracoronary stent implantation from January 2010 to March 2011 at the Drum Tower Hospital of Nanjing University School of Medicine. Those were excluded from the study if they had incomplete clinical data. The patients were divided into a normal group and a AKI group according to the standard of post-operation day 7 to identify AKI. The parameters of the patients included: 1) pre-operative ones: age, gender, hypertension, diabetes mellitus, cerebrovascular disease, left ventricular insufficiency, peripheral angiopathy, creatinine, urea nitrogen, estimated glomerular filtration rate (eGFR), hyperuricemia, proteinuria, emergency operation, hydration, medications (ACEI/ARBs, statins); 2) intraoperative ones: dose of contrast media, operative time, hypotension; and 3) postoperative one: hypotension. The parameters were analyzed with univariate analysis and multivariate logistical regression analysis.

RESULTS:

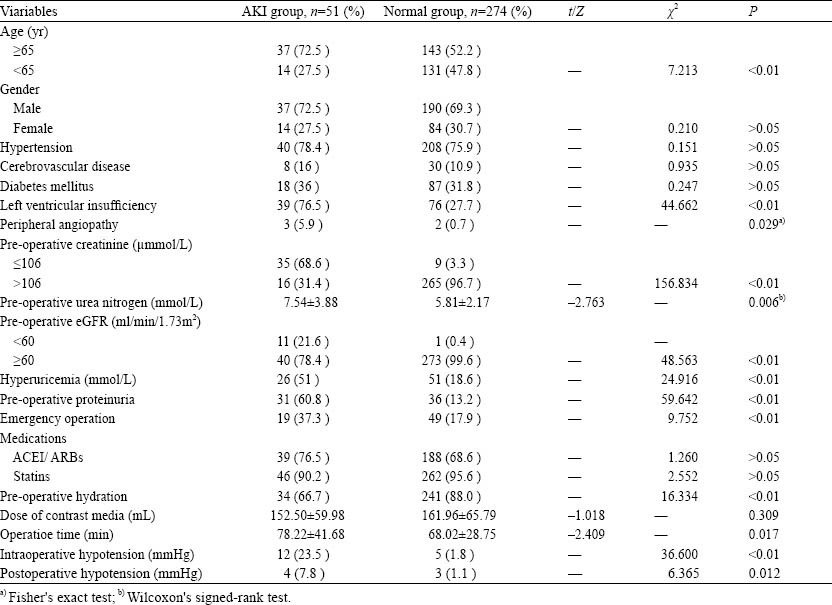

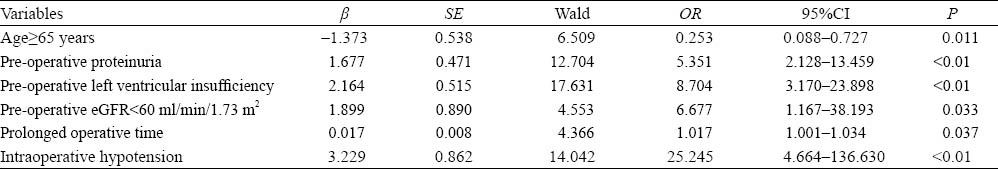

Of the 325 patients, 51(15.7%) developed AKI. Hospital day and in-hospital mortality were increased significantly in the AKI-group. Univariate analysis showed that age, pre-operative parameters (left ventricular insufficiency, peripheral angiopathy, creatinine, urea nitrogen, estimated glomerular filtration rate, hyperuricemia, proteinuria, hydration), emergency operation, intraoperative parameters (operative time, hypotension) and postoperative hypotension were significantly different. However, multivariate logistic regression analysis revealed that increased age (OR=0.253, 95%CI=0.088–0.727), pre-operative proteinuria (OR=5.351, 95%CI=2.128–13.459), pre-operative left ventricular insufficiency (OR=8.704, 95%CI=3.170–23.898), eGFR≤60 ml/min/1.73 m2 (OR=6.677, 95%CI=1.167–38.193), prolonged operative time, intraoperative hypotension (OR=25.245, 95%CI=1.001–1.034) were independent risk factors of AKI.

CONCLUSIONS:

AKI is a common complication and associated with ominous outcome following intracoronary stent implantation. Increased age, pre-operative proteinuria, pre-operative left ventricular insufficiency, pre-operative low estimated glomerular filtration rate, prolonged operative time, intraoperative hypotension were the significant risk factors of AKI.

KEY WORDS: Intracoronary stent implantation, Acute kidney injury, Risk factor, Outcome

INTRODUCTION

Acute kidney injury is a complex disorder of renal function that occurs in a variety of settings with clinical manifestations ranging from a minimal elevation of serum creatinine to renal failure.[1] It is of great concern because of its adverse effects on patients’ clinical outcomes, including prolonged hospitalization and increased morbidity and mortality.[2] These studies have documented the adverse prognostic impact of chronic renal insufficiency after percutaneous coronary intervention (PCI). Acute or chronic renal failure may occur after PCI for multiple reasons including hemodynamic instability, radiocontrast administration, and toxicity.[3] However, the incidence, risk factors and outcomes of AKI after PCI have rarely been reported. This study was undertaken to determine the incidence of AKI in patients undergoing intracoronary stent implantation and analyze the independent risk factors and outcomes of AKI in these patients.

METHODS

Patients and materials

A retrospective case control study was carried out in 325 patients who had undergone intracoronary stent implantation, including emergency and elective operation, from January 2010 to March 2011 in Drum Tower Hospital of Nanjing University School of Medicine. Those were excluded from the study if they had incomplete clinical data. We evaluated the parameters: 1) pre-operative ones: age, gender, hypertension, diabetes mellitus, cerebrovascular disease, left ventricular insufficiency (left ventricular ejection fraction, LVEF <45%), peripheral angiopathy, creatinine, urea nitrogen, estimated glomerular filtration rate (eGFR =186×serum creatinine, Scr/88.4–1.154×age–0.203×1.227(×0.742 if female), hyperuricemia, (a serum uric acid concentration of greater than 420 µmol/L and 350 µmol/L), proteinuria, emergency operation, hydration, medications (ACEI/ ARBs, statins); 2) intraoperative ones: dose of contrast media, operative time, hypotension; and 3) postoperative one: hypotension. The patients were classified into two groups according to the standard of post-operative day 7 to identify AKI.[4] They were a normal group (n=274) and an AKI group (n=51). AKI was defined as AKIN (AKI network) criteria.[5]

Statistical analysis

All data were analyzed by the SPSS11.5 for Windows. Measurement data were expressed as mean±SD and compared between the patients with and without acute kidney injury by independent-sample t test or Wilcoxon’s signed-rank test. Numeration data were expressed as percentage of total patients and compared between the two groups by the Chi-square test or Fisher’s exact test. The relative risk and 95% confidence interval of the significant factors were calculated. Multiple logistic regression analysis was made to identify the independent risk factors. A P value<0.05 was considered statistically significant.

RESULTS

The study was carried out in 325 patients who had a complete history of the disease, clinical findings, and laboratory data. The age of participants ranged from 40 to 91 years (mean age 65.57±10.66). Of the 325 patients, 51 (15.7%) developed AKI. The mean hospitalization of the AKI group was longer than that of the normal group (15.20±9.12 vs. 9.43±5.32, P<0.01), and the in-hospital mortality in the AKI group (n=2, 3.9%) was significantly higher than that in the normal group (n=0, 0%). The causes of death were circulatory collapse (n=1, 50%) and malignant arrhythmia (n=1, 50%). The demographic features of the patients in the two groups are shown in Table 1. The characteristics of the patients with independent risk factors of AKI are shown in Table 2.

Table 1.

Univariate analysis of clinical data of the AKI group and normal group after intracoronary stent implantation (mean±SD)

Table 2.

Multivariate logistical regression analysis of risk factors in the AKI group

DISCUSSION

Of the 325 patients, 51 (15.7%) developed AKI. This incidence was different from that reported elsewhere.[5] The difference can be explained by the difference in populations studied and high risk factors such as increased age, cardiovascular diseases, or by the nonuniform criteria used for defining AKI in different studies.[5–7] We found that a significantly increased length of hospital stay and a high rate of mortality were consistent with those reported by Chertow et al.[2] The causes of death in our study were circulatory collapse and malignant arrhythmia, the mechanisms of which include fluid overload, acid-base imbalance, electrolyte imbalance, myocardial depressant factors, and activation of inflammation.[8]

The incidence of AKI has been found to be increased, especially in the elderly. The reported incidence of AKI was 3.5-10 times higher in patients aged ≥65 years than in those aged <65 years.[6] Our data demonstrated an increased number of AKI patients in the elderly (OR=0.253). The increased incidence of AKI in the elderly is thought to be multifactorial, and it is attributable in part to anatomic and physiologic changes in the aging kidney, to an increased burden of comorbidities (hypertension, diabetes mellitus) affecting kidney function, to more frequent exposure to medications and interventions that alter renal hemodynamics or are nephrotoxic, and to alterations in drug metabolism and clearance associated with aging.[9,10] Taken together, the loss of renal functional reserve in the elderly is considered an increased risk for the development of AKI.[11]

The presence of baseline proteinuria is an independent risk factor for AKI.[12] Patients with proteinuria have less physiological adaptability and are therefore less able to tolerate reduced renal blood flow and other nephrotoxic insults. In our study, multivariate logistic regression analysis revealed that pre-operative proteinuria was an independent risk factor of AKI (OR=5.351). This finding is similar to that of the study by James MT et al.[13] Another study[14] has demonstrated that mild and heavy proteinuria were associated with an increased odds ratio of postoperative AKI and AKI requiring dialysis. Evidence of proteinuria before occurrence of potential acute kidney injury should prompt an individual at increased risk of AKI to receive preventive measures.[15] Thus more attention should be paid to patients with pre-operative proteinuria after intracoronary stent implantation.

Cardiorenal syndrome (CRS) includes a variety of acute or chronic conditions, involving the primary failing organs like the heart or the kidney. Thus, direct and indirect effects of each organ can initiate or perpetuate the combined disorder of the two organs through the complex combination of neurohormonal feedback mechanisms.[8] The prevalence of renal dysfunction in chronic HF was reported to be approximately 25%.[16] Even a slight decrease in estimated glomerular filtration rate (GFR) can significantly increase the mortality rate. In our study pre-operative left ventricular insufficiency significantly increased the risk of AKI (OR=8.704). The suggested mechanisms of CRS include:[8] 1) renal hypoperfusion and congestion following low cardiac output; 2) immuno-regulation imbalance (subclinical inflammation, necrosis-apoptosis); 3) neurohormonal abnormality (epinephrine, angiotensin, endothelin, renin-angiotension-aldosterone system); and 4) pharmacotherapies used in the management of HF (diuretics, ACEI/ARBs). We did not compare ejection fraction (EF) directly, but it does not indicate that EF is not important to evaluate the risk of AKI. Impaired left ventricle ejection fraction has a positive correlation with risk and severity of AKI in patients with acute heart failure.[17]

Chronic kidney disease is also associated with adverse outcomes. The low baseline eGFR (OR=6.677) was an independent risk in our study as compared with other studies.[12,13] Hsu et al[12] reported that patients with baseline eGFR 45–59 ml/min per 1.73 m2 had a nearly two-fold increase in adjusted OR of dialysis-requiring AKI compared with referent patients with eGFR of 60 ml/min per 1.73 m2 or above, whereas patients with baseline eGFR 15–29 ml/min per 1.73 m2 had a 29-fold increase in adjusted OR compared with referent patients. In this study, we cannot directly quantify the graded relationship between eGFR and risk of AKI, but the gradients of risk for acute kidney injury and subsequent adverse outcomes suggest that the reduced eGFR should be considered for prediction of acute kidney injury and its consequences.

We also found that prolonged operation time and intraoperative hypotension (OR =25.245, 95%CI=1.001–1.034) are independent risk factors of AKI. The mechanisms of AKI may be related to renal hemodynamic instability with prolonged operative time and renal hypoperfusion with hypotension.

In conclusion, AKI is a common complication after intracoronary stent implantation and is associated with ominous outcome. Increased age, pre-operative proteinuria, pre-operative left ventricular insufficiency, pre-operative low estimated glomerular filtration rate, prolonged operation time, intraoperative hypotension are the independent risk factors of AKI.

Acknowledgment

We are grateful to Professor Zhong-qiu Lu for his contribution to this study.

Footnotes

Funding: None.

Ethical approval: The present study was approved by the Ethical Committee of Nanjing Drum Tower Hospital, Nanjing, China.

Conflicts of interest: There is no conflict of interest in this study.

Contributors: He F proposed the study, and wrote the first draft. All authors read and approved the final version.

REFERENCES

- 1.Mehta RL, Kellum JA, Shah SV, Molitoris BA, Ronco C, Warnock DG, et al. Acute Kidney Injury Network: report of an initiative to improve outcomes in acute kidney injury. Crit Care. 2007;11:R31. doi: 10.1186/cc5713. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Chertow GM, Burdick E, Honour M, Bonventre JV, Bates DW. Acute kidney injury, mortality, length of stay, and costs in hospitalized patients. J Am Soc Nephrol. 2005;16:3365–3370. doi: 10.1681/ASN.2004090740. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Rihal CS, Textor SC, Grill DE, Berger PB, Ting HH, Best PJ, et al. Incidence and prognostic importance of acute renal failure after percutaneous coronary intervention. Circulation. 2002;105:2259–2264. doi: 10.1161/01.cir.0000016043.87291.33. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Palomba H, de Castro I, Neto AL, Laqe S, Yu L. Acute kidney injury prediction following elective cardiac surgery: AKICS Score. Kidney Int. 2007;72:624–631. doi: 10.1038/sj.ki.5002419. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Cruz DN, Ricci Z, Ronco C. Clinical review: RIFLE and AKIN time for reappraisal. Critical Care. 2009;13:1–9. doi: 10.1186/cc7759. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Abdel-Kader K, Palevsky PM. Acute kidney injury in the elderly. Clin Geriatr Med. 2009;25:331–358. doi: 10.1016/j.cger.2009.04.001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Parikh CR, Coca SG, Wang Y, Masoudi FA, Krumholz HM. Long-term prognosis of acute kidney injury after acute myocardial infarction. Arch Intern Med. 2008;168:987–995. doi: 10.1001/archinte.168.9.987. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Ronco C, Chionh CY, Haapio M, Anavekar NS, House A, Bellomo R. The cardiorenal syndrome. Blood Purif. 2009;27:114–126. doi: 10.1159/000167018. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Cheung CM, Ponnusamy A, Anderton JG. Management of acute renal failure in the elderly patient: a clinician's guide. Drugs Aging. 2008;25:455–476. doi: 10.2165/00002512-200825060-00002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Schmitt R, Coca S, Kanbay M, Tinetti ME, Cantley LG, Parikh CR. Recovery of kidney function after acute kidney injury in the elderly: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Am J Kidney Dis. 2008;52:262–271. doi: 10.1053/j.ajkd.2008.03.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Esposito C, Plati A, Mazzullo T, Fasoli G, De Mauri A, Grosjean F. Renal function and functional reserve in healthy elderly individuals. J Nephrol. 2007;20:617–625. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Hsu CY, Ordoñez JD, Chertow GM, Fan D, McCulloch CE, Go AS. The risk of acute renal failure in patients with chronic kidney disease. Kidney Int. 2008;74:101–107. doi: 10.1038/ki.2008.107. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.James MT, Hemmelgarn BR, Wiebe N, Pannu N, Manns BJ, Klarenbach SW. Glomerular filtration rate, proteinuria, and the incidence and consequences of acute kidney injury: a cohort study. Lancet. 2010;376:2096–2103. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(10)61271-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Huang TM, Wu VC, Young GH, Lin YF, Shiao CC, Wu PC. Preoperative proteinuria predicts adverse renal outcomes after coronary artery bypass grafting. J Am Soc Nephrol. 2010;22:156–163. doi: 10.1681/ASN.2010050553. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Hsu RK, Hsu CY. Proteinuria and reduced glomerular filtration rate as risk factors for acute kidney injury. Curr Opin Nephrol Hypertens. 2011;20:211–217. doi: 10.1097/MNH.0b013e3283454f8d. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Hillege HL, Nitsch D, Pfeffer MA, Swedberg K, McMurray JJV, Yusuf S. Renal function as a predictor of outcome in a broad spectrum of patients with heart failure. Circulation. 2006;113:671–678. doi: 10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.105.580506. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Fonarow GC, Stough WG, Abraham WT, Albert NM, Gheorghiade M, Greenberg BH. Characteristics, treatments and outcomes of patients with preserved systolic function hospitalized for heart failure: a report from the OPTIMIZEHF Registry. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2007;50:768–777. doi: 10.1016/j.jacc.2007.04.064. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]