Abstract

BACKGROUND:

Active compression-decompression cardiopulmonary resuscitation (ACDCPR) has been popular in the treatment of patients with cardiac arrest (CA). However, the effect of ACD-CPR versus conventional standard CPR (S-CRP) is contriversial. This study was to analyze the efficacy and safety of ACD-CPR versus S-CRP in treating CA patients.

METHODS:

Randomized or quasi-randomized controlled trials published from January 1990 to March 2011 were searched with the phrase “active compression-decompression cardiopulmonary resuscitation and cardiac arrest” in PubMed, EmBASE, and China Biomedical Document Databases. The Cochrane Library was searched for papers of meta-analysis. Restoration of spontaneous circulation (ROSC) rate, survival rate to hospital admission, survival rate at 24 hours, and survival rate to hospital discharge were considered primary outcomes, and complications after CPR were viewed as secondary outcomes. Included studies were critically appraised and estimates of effects were calculated according to the model of fixed or random effects. Inconsistency across the studies was evaluated using the I2 statistic method. Sensitivity analysis was made to determine statistical heterogeneity.

RESULTS:

Thirteen studies met the criteria for this meta-analysis. The studies included 396 adult CA patients treated by ACD-CPR and 391 patients by S-CRP. Totally 234 CA patients were found out hospitals, while the other 333 CA patients were in hospitals. Two studies were evaluated with high-quality methodology and the rest 11 studies were of poor quality. ROSC rate, survival rate at 24 hours and survival rate to hospital discharge with favorable neurological function indicated that ACD-CPR is superior to S-CRP, with relative risk (RR) values of 1.39 (95% CI 0.99–1.97), 1.94 (95% CI 1.45–2.59) and 2.80 (95% CI 1.60–5.24). No significant differences were found in survival rate to hospital admission and survival rate to hospital discharge for ACD-CPR versus S-CRP with RR values of 1.06 (95% CI 0.76–1.60) and 1.00 (95% CI 0.73–1.38).

CONCLUSION:

Quality controlled studies confirmed the superiority of ACD-CPR to S-CRP in terms of ROSC rate and survival rate at 24 hours. Compared with S-CRP, ACD-CPR could not improve survival rate to hospital admission or survival rate to hospital discharge.

KEY WORDS: Active compression-decompression, Cardiopulmonary resuscitation, Cardiac arrest, Meta-analysis

INTRODUCTION

Cardiac arrest (CA) seizes a large number of lives all around the world and causes increasing global concern. Approximately 400 000 to 460 000 people in the USA may die every year from sudden CA in the emergency department or before arrival at a hospital.[1] Standard CPR (S-CRP) has been used for cardiopulmonary resuscitation.[2] However, the mortality has not improved remarkably after S-CRP. The reported success rate of CPR ranged from 5% to 10%.[3] The reported coronary perfusion pressure (CPP), which was closely related to the successful resuscitation, was far from normal in patients with CA receiving S-CRP.[4] Active compression-decompression cardiopulmonary resuscitation (ACDCPR) with a hand-held suction device is applied on the mid sternum to compress the chest and then to actively decompress the chest after each compression. European Resuscitation Council Guidelines for Resuscitation 2010 does not recommend ACD-CPR as an option for CRP in CA patients.[5] However, recent studies demonstrated that ACD-CPR improved clinical outcome compared with S-CRP[5] and that the curative effect of ACD-CRP and S-CRP was not consistent in CA patients. Based on a systematic review and meta-analysis of the literature, we assessed existing evidences about the efficacy and safety of ACD-CRP and S-CRP in the management of CA.

METHODS

Search strategy

Studies were searched in PubMed, EmBASE, and China Biomedical Document Database from January 1990 to May 2011 by using the following terms: Active compression-decompression cardiopulmonary resuscitation, cardiac arrest, and cardiopulmonary resuscitation. The Cochrane database of systematic reviews was searched using such phrase as active compression-decompression cardiopulmonary resuscitation.

Inclusion and exclusion criteria

Inclusion criteria were as follows: 1) randomized or quasi-randomized controlled studies in adults (more than 18 years) diagnosed with CA at in-patient or out-patient clinics; 2) intervention with ACD-CRP; 3) intervention with S-CRP as control; 4) English and Chinese languages; 5) results including at least one of the following variables: ROSC rate, survival rate at 24 hours, survival rate to hospital admission, survival rate to hospital discharge, survival rate to hospital discharge without neurological impairment and complications of CPR. Exclusion criteria were as follows: 1) animal studies; 2) patients studied under 18 years old; 3) non-randomized studies; 4) studies far from our purpose of the study.

Selection of studies

The included studies were examined by two independent reviewers, and disagreements were handled by discussion.

Data extraction

Original data were extracted on a standard form, which includes: 1) the general information of selected studies, including details of study design, and randomized-blind criteria; 2) study population; 3) intervention and comparison and 4) measures of efficacy and safety.

Analysis of methodological quality and scientific evidence

The methodology in all the studies was analyzed including: 1) random distribution; 2) allocation concealment; 3) blind method if any; 4) studies lost or not; 5) quality evaluation of intention treatment. Jadad score was applied to evaluate the studies, the method was considered of low quality when the score was 1–2 and of high quality when it was 3–5.[6]

Data analysis and synthesis of results

Standard meta-analytical techniques were used to determine the efficacy and safety of ACD-CRP and S-CRP, using a model of fixed or random effects.[7] We analyzed dichotomous variables by estimation of relative risk (RR) with a 95% confidence interval as well as continuous variables by weighted mean difference (WMD) with a 95% confidence interval. The degree of inconsistency between the studies was quantified using the I2 statistical method that describes the proportion of variance across the studies because I2<50% and I2>50% reflect small and large inconsistency respectively.[8] The sensitivity of the method was analyzed to explore statistical heterogeneity.[9] As in recent studies, we did not use funnel plots to examine the possibility of publication bias.[10]

RESULTS

Searching results

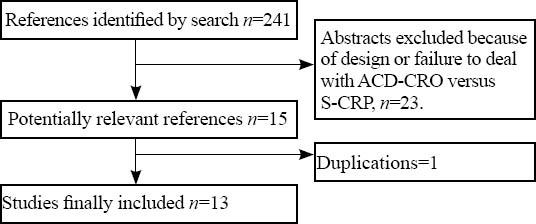

In 151 articles searched, 130 were reviews and editorials, investigations, analytical studies, and case reports. Sixty animal studies were excluded and another 4 studies were excluded because their intervention groups did not use ACD-CRP. Furthermore, two studies were published in duplication. The latest study was selected. Finally, 13 randomly controlled trials were included into this meta-analysis involving 2 353 CA patients.[11–23] Thus 1 252 patients accepted ACD-CRP, and 1 252 received S-CRP (Figure 1).

Figure 1.

Searching strategy.

Included studies

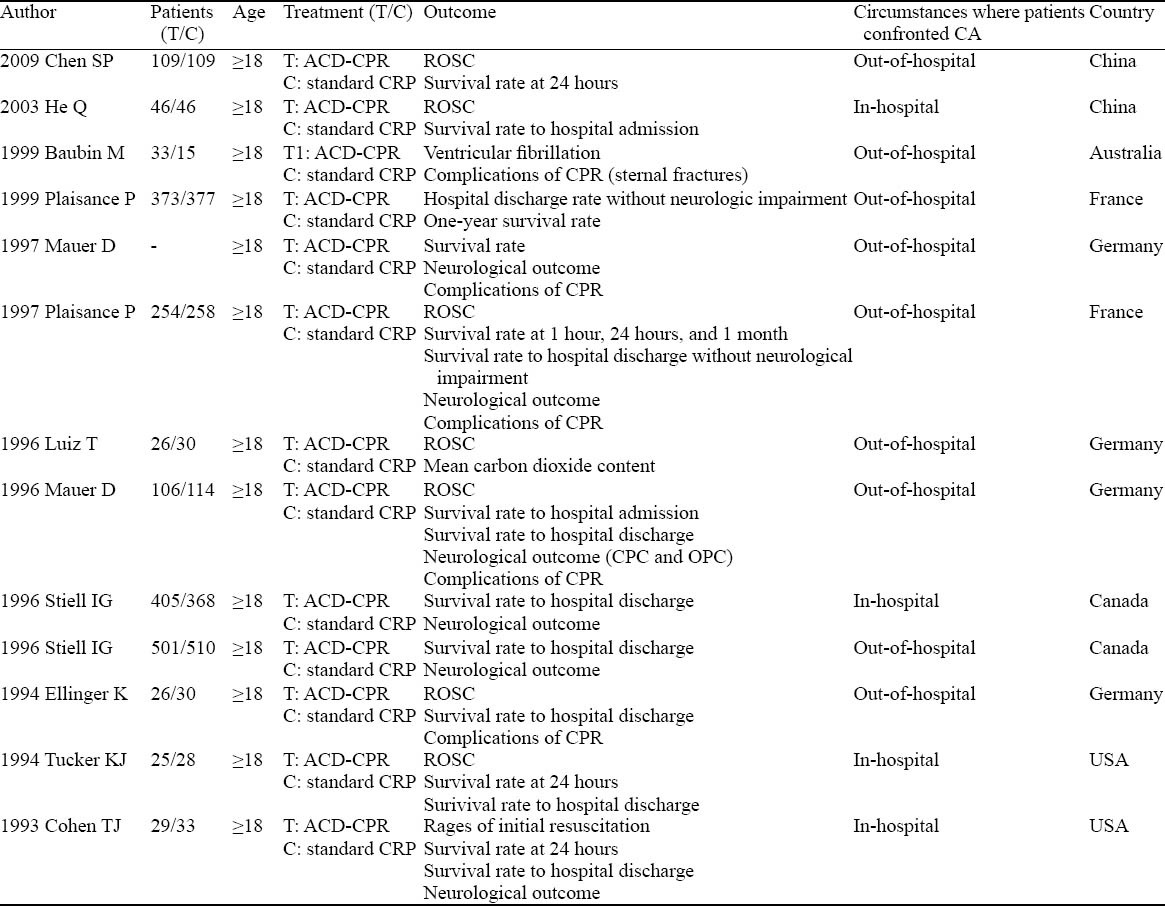

Among the included studies, 4 were accomplished in Germany, 2 in France, 2 in Canada, and 1 in Australia. The rest 4 studies were conducted in the USA (2 studies) and China (2 studies). The four studies included patients with CA encountered in hospitals while the other studies included patients with CA out hospitals. Only Stiell studied both out-hospital and in-hospital CA patients. The four studies were multi-center control studies, and the other studies were single-center control studies. Stiell et al[21] studied a largest sample of 2 000 patients, while Tucker et al[23] studied 53 patients, comparatively the smallest sample. Six studies provided ROSC rate, 4 with survival rate at 24 hours, 2 with survival rate to hospital admission, 4 with survival rate to hospital discharge, and 5 with complications of CPR (Table 1).

Table 1.

General information about included studies

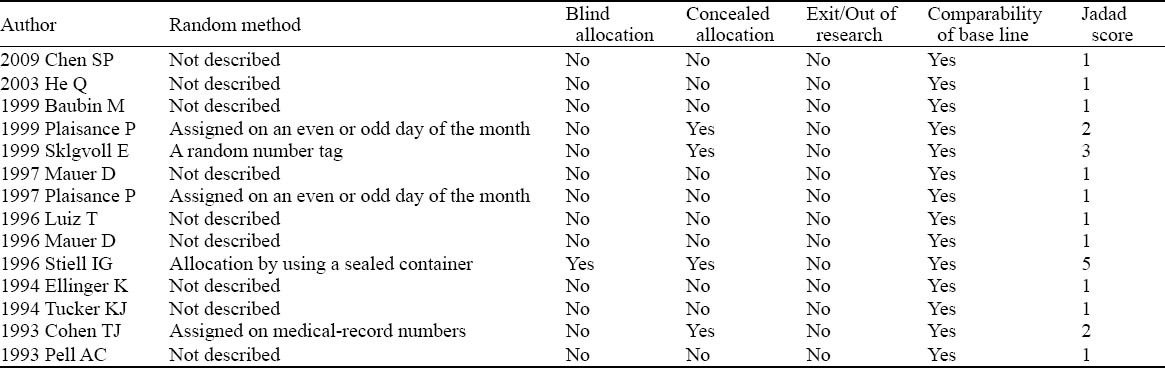

Methodology of the included studies

In 13 studies included in this analysis, there was no significant difference in baseline conditions. Four studies described the details of randomization. Only one study provided double blind allocation, while the rest did not mention it. In four studies using concealed allocation, only two were appropriate. According to Jadad scoring, more than three scores were found in two studies which were considered of high-quality methodology, while the rest studies were not satisfied with scores fewer than 3 (Table 2).

Table 2.

Quality of the included studies

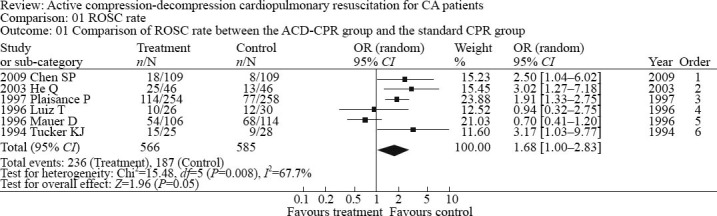

ROSC rate

Six studies provided specific data on ROSC rate. The ACD-CRP group included 566 patients, and the S-CRP group consisted of 585 patients. There was significant difference among the studies (P=0.002, I2=74.4%). The calculated RR merger was 1.39 (95% CI 0.99–1.97), and analysis showed a significant improvement of ROSC rate in the ACD-CRP group compared with the S-CRP group (Figure 2).

Figure 2.

Comparison of ROSC rate between the ACD-CPR group and the S-CPR group.

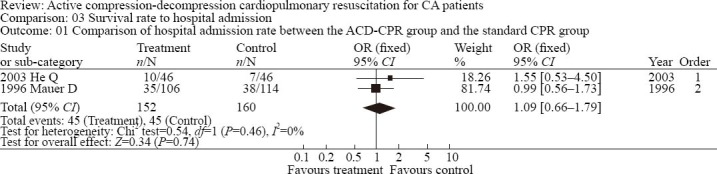

Survival rate to hospital admission

Two studies provided specific data on survival rate to hospital admission for out hospital patients. The ACD-CRP group included 162 patients and the S-CRP group comprised 160 patients. No statistical heterogeneity was seen in the studies (P=0.45, I2=0%), so the model of fixed effects was used for analysis. The calculated OR merger was 1.06 (95% CI 0.76–1.60), and joint analysis also showed no significant difference in survival rate to hospital admission in the ACD-CRP group compared with the S-CRP group (Figure 3).

Figure 3.

Comparison of hospital admission rate between the ACD-CPR group and the S-CPR group.

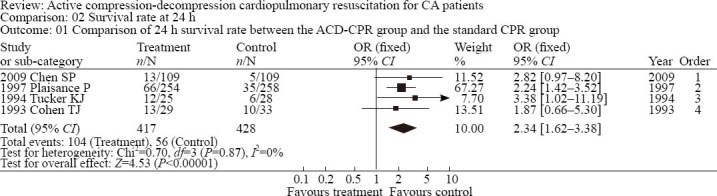

Survival rate at 24 hours

Four studies provided specific data on survival rate at 24 hours. The ACD-CRP group included 417 patients, and the S-CRP group 428 patients. No significant heterogeneity was seen in the studies (P=0.78, I2=0%), thus random effects were analyzed. The calculated OR merger was 1.94 (95% CI 1.45–2.59), and joint analysis also showed a significant improvement in survival rate at 24 hours in the ACD-CRP group compared with the S-CRP group (Figure 4).

Figure 4.

Survival rate comparison at 24 hours between the ACD-CPR group and the S-CPR group.

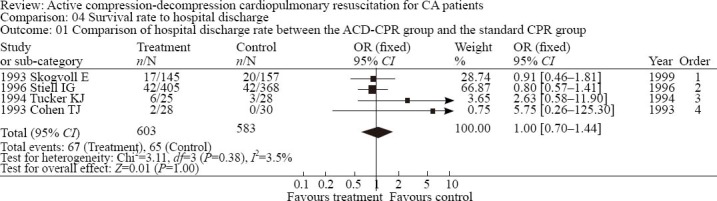

Survival rate to hospital discharge

Four studies provided specific data on survival rate to hospital discharge. The ACD-CRP group included 608 patients and the S-CRP group 583 patients. No statistically heterogeneity was found in the studies (P=0.39, I2=0.9%), thus fixed effects were analyzed. The calculated RR merger was 1.00 (95% CI 0.73–1.38), and joint analysis also showed no significant difference in survival rate to hospital discharge in the ACD-CRP group compared with the S-CRP group (Figure 5).

Figure 5.

Hospital discharge rate comparison between the ACD-CPR group and the S-CPR group.

Complications of CPR

Five studies described complications after CPR; however, data were difficult to collect for analysis. Instead, descriptive studies were used for evaluating complications after CPR. It was reported that there were more sternal fractures and rib fractures (13/15 vs. 11/20; P<0.05) in ACD-CPR patients than in STD-CPR patients (14/15 vs. 6/20; P<0.005). Also sternal dislodgements (2.9% vs. 0.4%, P=0.03) and hemoptysis (5.4% vs. 1.3%, P=0.01) were more frequent in ACD ACLS patients. Others found that there was no difference in the incidence of complications caused by CPR.

DISCUSSION

The American Heart Association Guidelines for Cardiopulmonary Resuscitation and Emergency Cardiovascular Care 2010 recommend premier selection of standard CPR for CA patients in and out of hospital.[2] However, studies showed that standard CPR can only supply vital organs with limited blood pressure (BP),[24] even specialists are unable to perform high-quality resuscitation because of energy consumption.[25] The overall survival rate after cardiac arrest remains low. In 74 studies involving 36 communities as reported, the survival rate ranged from 2% to 44%.[26] The increase of CPP was found to be closely related to successful resuscitation.[2] Chest expansion after segues can suck blood into the heart where blood is ready for the next pump. The more the chest is expanded, the more cardiac output is given. During ACD-CPR, positive and negative pressures are used alternately to the chest by a “plunger” that forms a seal with the anterior chest wall. Several studies found that ACD-CPR produced better hemodynamic effects than standard CPR in patients,[27–29] but there were exceptions.[30]

The results of this meta-analysis indicate that ACD-CPR is superior to STD-CPR for CA patients in terms of ROSC rate, survival rate at 24 hours, and admission rate. However, survival rate to hospital discharge is not statistically significant. ACD-CPR can be used to impove the neurological outcome at discharge or to produce a better long-term outcome. This finding is not consistent with the published meta-analyses, suggesting that ACD-CPR is not beneficial to patients with CA.[31] This meta-analysis showed an increased rate of complications including sternal fracture which might be associated with ACD-CPR. Sternal fracture is unlikely to increase mortality because it causes no severe internal organ damage.

In this meta-analysis, methodological quality was not high in most of quasi-randomized controlled trials because only Chinese and English articles were reviewed. Large-scale multi-center randomized, controlled clinical studies on ACD-CRP for CA patients are needed.

The price of ACD-CPR device is acceptable for any hospital. However, the efficacy of ACD-CPR may be highly dependent on the quality and duration of training.[32]

In conclusion, compared with S-CPR, ACD–CPR can improve the ROSC rate and survival rate at 24 hours. There is no difference in hospital admission rate and hospital discharge rate between S-CPR and ACD-CPR patients. More studies are needed to provide sufficient evidence for clinical practice.

Footnotes

Funding: None.

Ethical approval: Not needed.

Conflicts of interest: The authors declare that there is no conflict of interest.

Contributors: Luo XR proposed the study, analyzed the data and wrote the first draft. All authors contributed to the design and interpretation of the study and to further drafts.

REFERENCES

- 1.Zheng ZJ, Croft JB, Giles WH, Mensah GA. Sudden cardiac death in the United States, 1989 to 1998. Circulation. 2001;104:2158–2163. doi: 10.1161/hc4301.098254. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Neumar RW, Otto CW, Link MS, Kronick SL, Shuster M, Callaway CW, et al. Adult advanced cardiovascular life support: 2010 American Heart Association Guidelines for Cardiopulmonary Resuscitation and Emergency Cardiovascular Care Circulation. 2010;122:729–767. doi: 10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.110.970988. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Jiang L, Zhang JS. Mechanical cardiopulmonary resuscitation for patients with cardiac arrest. World J Emerg Med. 2011;2:165–168. doi: 10.5847/wjem.j.1920-8642.2011.03.001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.von Planta I, Wagner O, von Planta M, Ritz R. Determinants of survival after rodent cardiac arrest: implications for therapy with adrenergic agents. Int J Cardiol. 1993;38:235–245. doi: 10.1016/0167-5273(93)90241-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Deakin CD, Nolan JP, Soar J, Sunde K, Koster RW, Smith GB, et al. European Resuscitation Council Guidelines for Resuscitation 2010 Section 4. Adult advanced life support. Resuscitation. 2010;81:1305–1352. doi: 10.1016/j.resuscitation.2010.08.017. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Aufderheide TP, Frascone RJ, Wayne MA, Mahoney BD, Swor RA, Domeier RM, et al. Standard cardiopulmonary resuscitation versus active compression-decompression cardiopulmonary resuscitation with augmentation of negative intrathoracic pressure for out-of-hospital cardiac arrest: a randomized trial. Lancet. 2011;377:301–311. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(10)62103-4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Jadad AR, Moore RA, Carroll D, Jenkinson C, Reynolds DJ, Gavaghan DJ, et al. Assessing the quality of reports of randomized clinical trials:is blinding necessary? Control Clin Trials. 1996;17:1–12. doi: 10.1016/0197-2456(95)00134-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Egger M, Smith GD, Douglas G. Systematic reviews in health care: meta-analysis in context. BMJ Books. 2001;2:3–475. [Google Scholar]

- 9.Higgins JP, Thompson SG, Deek JJ, Altman DG. Measuring inconsistency in meta-analyses. Br Med J. 2003;327:557–560. doi: 10.1136/bmj.327.7414.557. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Higgins J, Thompson S, Deeks J, Altman D. Statistical heterogeneity in systematic reviews of clinical trials: a critical appraisal of guidelines and practice. J Health Serv Res Policy. 2002;7:51–61. doi: 10.1258/1355819021927674. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Tang J, Liu JL. Misleading funnel plot for detection of bias in meta-analysis. J Clin Epidemiol. 2000;53:477–484. doi: 10.1016/s0895-4356(99)00204-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Chen SP. Curative effects of the heart pump in 109 pre-hospital cardiopulmonary resuscitation patients for cardiopulmonary resuscitation. Chin Crit. 2009;21:378. [Google Scholar]

- 13.Kulstad EB, Courtney DM, Waller D. Induction of therapeutic hypothermia via the esophagus: a proof of concept study. World J Emerg Med. 2012;3:118–122. doi: 10.5847/wjem.j.issn.1920-8642.2012.02.007. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Baubin M, Sumann G, Rabl W, Eibl G, Wenzel V, Mair P. Increased frequency of thorax injuries with ACD-CPR. Resuscitation. 1999;41:33–38. doi: 10.1016/s0300-9572(99)00033-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Plaisance P, Lurie KG, Vicaut E, Adnet F, Petit JL, Epain D, et al. A comparison of standard cardiopulmonary resuscitation and active compression-decompression resuscitation for out-of-hospital cardiac arrest. French Active Compression-Decompression Cardiopulmonary Resuscitation Study Group. N Engl J Med. 1999;341:569–575. doi: 10.1056/NEJM199908193410804. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Skogvoll E, Wik L. Active compression-decompression cardiopulmonary resuscitation: a population-based, prospective randomised clinical trial in out-of-hospital cardiac arrest. Resuscitation. 1999;42:163–172. doi: 10.1016/s0300-9572(99)00086-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Mauer D, Schneider T, Dick W, Elich D, Mauer M. Active compression-decompression resuscitation. Improved survival rate in an emergency medicine system with emergency physician assistance? Med Klin (Munich) 1997;92:381–388. doi: 10.1007/BF03042567. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Plaisance P, Adnet F, Vicaut E, Hennequin B, Magne P, Prudhomme C, et al. Benefit of active compression-decompression cardiopulmonary resuscitation as a prehospital advanced cardiac life support. A randomized multicenter study. Circulation. 1997;95:955–961. doi: 10.1161/01.cir.95.4.955. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Luiz T, Ellinger K, Denz C. Active compression-decompression cardiopulmonary resuscitation does not improve survival in patients with prehospital cardiac arrest in a physician-manned emergency medical system. Cardiothorac Vasc Anesth. 1996;10:178–186. doi: 10.1016/s1053-0770(96)80234-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Mauer D, Schneider T, Dick W, Withelm A, Elich D, Mauer M. Active compression-decompression resuscitation: a prospective, randomized study in a two-tiered EMS system with physicians in the field. Resuscitation. 1996;33:125–134. doi: 10.1016/s0300-9572(96)01006-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Stiell IG, Hébert PC, Wells GA, Laupacis A, Vandemheen K, Dreyer JF, et al. The Ontario trial of active compression-decompression cardiopulmonary resuscitation for in-hospital and prehospital cardiac arrest. JAMA. 1996;275:1417–1423. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Ellinger K, Luiz T, Denz C, van Ackern K. Randomized use of an active compression-decompression technique within the scope of preclinical resuscitation. Anasthesiol Intensivmed Notfallmed Schmerzther. 1994;29:492–500. doi: 10.1055/s-2007-996790. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Tucker KJ, Galli F, Savitt MA, Kahsai D, Bresnahan L, Redberg RF. Active compression-decompression resuscitation: effect on resuscitation success after in-hospital cardiac arrest. J Am Coll Cardiol. 1994;24:201–209. doi: 10.1016/0735-1097(94)90564-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Reynolds JC, Salcido DD, Menegazzi JJ. Correlation between coronary perfusion pressure and quantitative ECG waveform measures during resuscitation of prolonged ventricular fibrillation. Resuscitation. 2012;83:1497–1502. doi: 10.1016/j.resuscitation.2012.04.013. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Wang HC, Chiang WC, Chen SY. Video recording and time motion analyses of manual versus mechanical cardiopulmonary resuscitation during ambulance transport. Resuscitation. 2007;74:453–460. doi: 10.1016/j.resuscitation.2007.01.018. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Eisenberg MS, Cummins RO, Damon S, Larsen MP, Hearne TR. Survival rates from out-of-hospital cardiac arrest: recommendations for uniform definitions and data to report. Ann Emerg Med. 1990;19:1249–1259. doi: 10.1016/s0196-0644(05)82283-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Shultz JJ, Coffeen P, Sweeney M, Detloff B, Kehler C, Pineda E, et al. Evaluation of standard and active compression– decompression CPR in an acute human model of ventricular fibrillation. Circulation. 1994;89:684–693. doi: 10.1161/01.cir.89.2.684. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Orliaguet GA, Carli PA, Rozenberg A, Janniere D, Sauval P, Delpech P. End-tidal carbon dioxide during out-of-hospital cardiac arrest resuscitation: comparison of active compression– decompression and standard CPR. Ann Emerg Med. 1995;25:48–51. doi: 10.1016/s0196-0644(95)70354-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Guly UM, Mitchell RG, Cook R, Steedman DJ, Robertson CE. Paramedics and technicians are equally successful at managing cardiac arrest outside hospital. BMJ. 1995;310:1091–1094. doi: 10.1136/bmj.310.6987.1091. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Malzer R, Zeiner A, Binder M, Domanovits H, Knappitsch G, Sterz F, et al. Hemodynamic effects of active compression-decompression after prolonged CPR. Resuscitation. 1996;31:243–253. doi: 10.1016/0300-9572(95)00934-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Lafuente-Lafuente C, Melero-Bascones M. Active chest compression-decompression for cardiopulmonary resuscitation. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2004;2:CD002751. doi: 10.1002/14651858.CD002751.pub2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Plaisance P, Lurie KG, Vicaut E, Adnet F, Petit JL, Epain D, et al. A comparison of standard cardiopulmonary resuscitation and active compression–decompression resuscitation for out-of-hospital cardiac arrest. French Active Compression-Decompression Cardiopulmonary Resuscitation Study Group. N Engl J Med. 1999;341:569–575. doi: 10.1056/NEJM199908193410804. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]