Abstract

BACKGROUND:

This study aimed to compare the topical anesthetic lignocaine, adrenaline, and tetracaine (LAT) (4% lignocaine, 1:2 000 adrenaline, 1% tetracaine) with the conventional lignocaine infiltration(LI) for repair of minor lacerations, for the comfort of anesthetic administration, efficacy, adverse effects and cost.

METHODS:

This was a prospective randomized clinical trial. Forty Asian patients who required toilet and suture for minor lacerations in the emergency department of the Singapore General Hospital over a 4-month period. The patients were assigned randomly to 2 arms of treatment. The first was the LAT gel group who had LAT gel applied to the laceration prior to suturing. The second was the control group in whom the anesthetic administered was lignocaine infiltration (LI) via a syringe. The pain of the process of administering anesthetic and efficacy of anesthesia were scored using the visual pain scale included within. The efficacy of LAT vs. lignocaine infiltration as an anesthetic prior to the toilet and suture of minor lacerations and complications of therapy.

RESULTS:

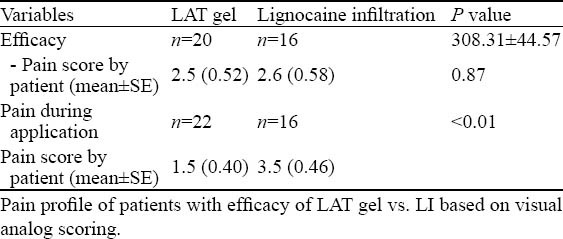

Twenty patients were randomized to LAT gel and 16 to LI on an intention to treat analysis. The mean pain score by patients in the LAT gel group was 2.5 (0.52 SE), and 2.5 (0.58 SE) in the LI group. The pain score for pain during application of the anesthetic was 1.5 (0.40) in the LAT gel group, and 3.5 (0.46) in the LI group. There was no difference in complications between the LAT and LI groups

CONCLUSION:

LAT gel prior to the toilet and suture of minor lacerations is proven to be as efficacious as LI in terms of patient comfort and effectiveness of anesthesia. The complications are also comparable to those treated with LI.

KEY WORDS: Lignocaine infiltration, Lacerations, Emergency department, Pain score

INTRODUCTION

The ideal anesthetic management for lacerations would be one which is painless and can be performed quickly and with a low complication rate. Lignocaine, adrenaline, and tetracaine (LAT) gel has been used widely for anesthesia before suturing of lacerations in the United States and United Kingdom. Hospitals usually use lignocaine infiltration (LI) for local anesthesia. Minor lacerations form a good 10%–15% of emergency department attendances in Singapore. LAT is a formulation of lignocaine base (4%), racemic adrenaline (epinephrine) HCl (0.182%) and tetracaine HCl (0.569%). Studies have shown that application of the gel has at least as good efficacy as the conventional mode of LI which is much more painful and may result in patchy anesthesia.[1–3,6]

This study seeks to compare the efficiency of LAT gel with LI for the anesthesia of lacerations prior to toilet and suture. Null hypothesis is assumed, that there is no difference in efficacy of anesthesia between the LAT gel and LI groups of treatment.

METHODS

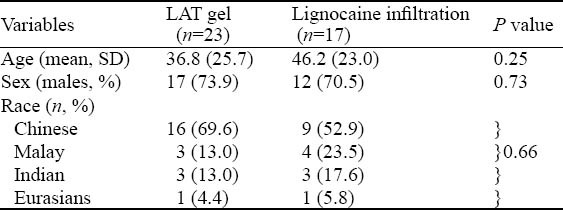

Patients presenting to the Emergency Department aged > or = 1 year up to 70 years with clean, non bite lacerations < or = 6 hours, were enrolled in this study from January 2003 through April 2003. The sample size estimation before recruitment was actually 46 with 23 in each arm of treatment. These criteria were not met due to the disruption of the study by the severe acute respiratory syndrome (SARS) outbreak. This was a prospective randomized clinical trial of 40 such patients who required toilet and suture for such minor lacerations. Approval to carry out the study at Singapore General Hospital (SGH) was granted by the SGH Ethics Committee. Exclusion criteria were those with lacerations on the fingers, toes, nose, penis due to the vasoconstrictive effect of adrenaline in LAT. Lacerations on mucous membranes and those caused by bites, whether human or animal bite wounds were also excluded. Patients with known allergy to lignocaine were excluded. The dermographic profile is shown in Table 1 and the characteristics of the wounds are shown in Table 2.

Table 1.

Demographic profile

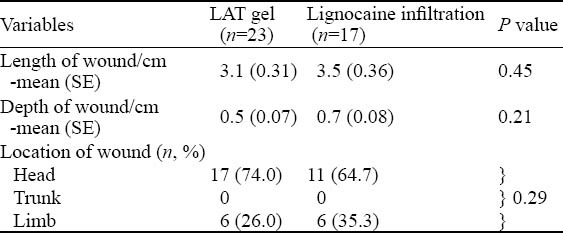

Table 2.

Characteristics of wounds

For patients aged >1 to 18 years, consent was taken from the accompanying adult/parent.

Suitable patients were assigned using sealed envelopes to 2 arms of treatment. The first was the control group in whom the anesthetic administered was LI via a syringe. The clinician in charge performed LI. The second group had the LAT gel applied to the laceration by a trained nurse prior to suturing. This gel was pre-prepared in a 5 mL syringe which was inspected for discoloration or broken seal. The LAT gel was then squirted into and around the laceration with a syringe tip. Mucous membranes were avoided as they absorb LAT more readily than a wound bed. The wound was then covered with a sterile piece of gauze and taped down with micropore. The gel was allowed to remain on the wound for 20 minutes. The skin may be blanched for the vasocontrictive effects of adrenaline. Once anesthesia was achieved by either LI or LAT, the wound was cleaned thoroughly to remove any dirt or foreign body and the laceration was then sutured. The supplies were discarded after use.

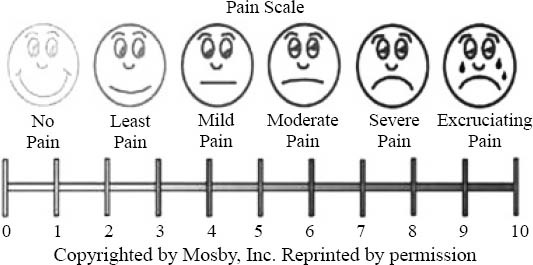

The pain of administering the anesthetic was scored on a 100 mm visual analog scale marked ‘most pain’ at the high end and ‘no pain’ at the left end point. This was also scored in children aged 10 years and below by using the same scale but with faces drawn to describe facial expressions of pain. Figure 1 shows that the pain scale was used to score pain. The efficacy of anesthesia was assessed by the practitioner using a 27G needle and the presence of blanching was also noted for LAT gel applications. Scoring of pain was done by the patients themselves if they were above 10 years or by the parents and the clinician if less than 10 years. Observers based pain scores on the pain experienced as the needle pierced the patients’ skin to measure the actual anesthetic performance separated from the patients response to fear and distress. The number of sutures needed to stitch the laceration were recorded. After the procedure the patients were given the usual wound care advice and told to return after 7 days for review. The wound was reviewed for infection, dehiscence, erythema, redness and loss of stitches. In the event of any complication mentioned above, patient was told to return another 7 days later for further review.

Figure 1.

Pain scale.

Data were entered into Access 97 (Microsoft Inc, Redmond, WA) and analyzed using SPSS. For continuous data, Student’s t test was used if the data were normally distributed. Otherwise the Mann-Whitney U test was used. Fisher’s exact test was used to assess differences between the 2 groups of qualitative data (sex, race, wound contamination, etc). Multivariate logistic regression was used to adjust for confounding variables such as age, sex and race. The analysis was on an equivalence test of means basis using two one-sided tests on data with sample sizes of 23 in both groups. This achieved 80% power at a 5% significance level when the true difference between the means was 0.00, the standard deviation was 2.50, and the equivalence limits were –2.20 and 2.20.

RESULTS

There were 23 patients in the group receiving LAT and 17 in the group receiving LI. The two groups had similar demographic profile (Table 1). The possible confounders like age, sex and race were quite balanced in both arms. Only one patient less than 10 years was included in the study. He was a precocious 7 year old and could do the pain scoring himself. There was hence no need to attempt a separate analysis of data for pain scoring by pediatric patients. The length of the wounds was 3.1 cm (SE 0.31) for the LG group and 3.5 cm (SE 0.36) for the LI group (P=0.45). The depth of the wounds was 0.5 cm (SE 0.07) and 0.7cm (SE 0.08) respectively (P=0.21). Table 2 shows the locations of the wounds, namely the head (72.7%) and the limbs (27.3%). We did not manage to get any patients with trunk wounds during the study period. The degree of contamination was mild in all the patients except one who had moderate contamination in the LI group. He had some foreign bodies in the wound which could be removed manually. There was no failure of anesthetic efficacy for the LAT gel group at all during the process of suturing. Hence there was no need for LAT gel patients to switch to LI midway during the procedure, which may confound the results.

Table 3 outlines the outcome of the two groups. There was no difference in the efficacy of LAT gel vs LI with patient pain score (P<0.87). The improvement in patient comfort for the LAT group was significant during the process of anesthetic administration compared with the LI group (P<0.01). Patients usually reported a slight smarting sensation when lignocaine gel was applied.

Table 3.

Primary outcome

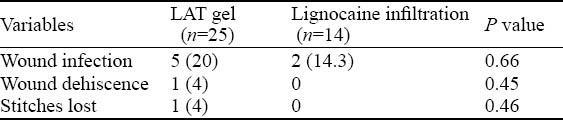

Complications included wound infection, wound dehiscence and loss of stitches. There was no significant difference in the rate of complications between the two groups (Table 4). Furthermore, the incidence rate for wound dehiscence and stitches lost was nil in the LI group, hence disabling the ability of the logistic regression.

Table 4.

Complications in each treatment arm (n, %)

DISCUSSION

In this study we found that LAT gel is as efficacious as LI for anesthesia prior to the toilet and suture of minor lacerations. LAT gel is used vastly in Westen countries but has not yet significantly popularized in Singapore. The local anecdotal clinical benefits, however, have been raving, especially by Emergency Department clinicians who have been using it for pediatric patients at the Kendang Kerbau Children’s Hospital. This study was undertaken to evaluate its use on Asians as well, as we know that sometimes Asians’ responses to drugs are different from those of Caucasians.

The study found that LAT gel was as efficacious as LI in terms of patient comfort and effectiveness of anesthesia (P<0.05). In our opinion, a difference in pain score between the 2 arms of treatment more than or equal to 2 is clinically significant. Table 3 shows that pain scoring by patient in the LI group was 3.5 versus 1.5 in the LAT gel group.

In our study the efficacy of LAT gel as an anesthetic was similar to that in other studies.[1,2,3,6] One study even used the adrenaline mixture on fingers in 5–18 year old children, with no ill effects of digital ischemia caused by the adrenaline component.[3] It also did away with the inherent disadvantages of having cocaine in concoctions which had tetracaine, adrenaline and cocaine gel.[2] However, the combination of the constituents of LAT gel differs from manufacturer to manufacturer and this will result in different efficacies of the gel. For example, ours was a mixture of 4% lignocaine, 1:2 000 adrenaline, and 1% tetracaine. It was presented in a 5 mL syringe capped with a Luer lock cap. Other mixtures included a constitutional mix of 12.3 mg lignocaine, 8.2 mg tetracaine, and 0.82 mg adrenaline.[5]

The cost of 1 syringe of LAT gel is about 5 US dollars and that of a 5 mL syringe of 1% lignocaine solution for infiltration is about 2.50 US dollars. Although the cost of lignocaine for LI is half that of LAT gel, many patients, will be willing to pay more of the relatively small sum for the comfort of the needleless anesthetic technique with LAT gel. This is even more so for the parents of children whose kids have to undergo toilet and suturing of minor lacerations. In addition, one does away with needles and hence the potential of needlestick injuries. In human immunodeficiency virus and high risk hepatitis transmissions, this is an immense advantage.

The limitations of the study were a small sample size of 40 done only for a short period of 4 months in 2003. The premature termination of the study was due to the unexpected SARS (Severe Acute Respiratory Syndrome) outbreak in Singapore. The outbreak caused major chaos in hospitals throughout Singapore lasting more than 1 year and our department was not spared. We, however, carried on with the publishing of this article as the anesthesic concoction and utilization of LAT has not changed.[4] Hence the study results would be as relevant today as then. Singapore General Hospital is an adult hospital with minimal pediatric attendances. Consent for the pediatric patient in the study as mentioned earlier was taken from his accompanying parents. Hence all cases of pain scoring during the procedure were done by the patients themselves and not by proxy. We felt that if a bigger sample size was taken, there would be instances where a switch to LI from unsuccessful LAT gel anesthesia would be necessary. One postulation is that adults are able to tolerate slightly inadequate anesthesia more than pediatric patients. Earlier studies focused primarily on the pediatric age group studying gel vs solutions /creams which were applied topically, such as eutectic mixture of local anaesthesia (EMLA) cream. Tetracaine was deemed of more rapid onset and a less expensive alternative to EMLA.[7]

In conclusion, the use of LAT gel is beneficial in Asian adults and not confined to the pediatric age group, though further studies with a larger sample size are preferred.

Footnotes

Funding: None.

Ethical approval: The study was approved by the Medical Ethics Committee of Singapore General Hospital, Singapore.

Conflicts of interest: The authors declare that there is no conflict of interest.

Contributors: Lee JMH proposed the study, analyzed the data and wrote the first draft. All authors contributed to the design and interpretation of the study and to further drafts.

REFERENCES

- 1.Chen BK, Cunningham BB. Topical Anaesthetics in children: Agents and techniques that equally comfort patients, parents and clinicians. Curr Opin Pediatr. 2001;13:324–330. doi: 10.1097/00008480-200108000-00007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Ernst AA, Marvez E, Nick TG, Chin E, Wood E, Gonzaba WT. Lidocaine adrenaline tetracaine gel vs. tetracaine adrenaline cocaine gel for topical anaesthesia in linear scalp and facial lacerations in children aged 5 to 17 years. Pediatrics. 1995;95:255–258. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.White NJ, Kim MK, Brousseau DC, Bergholte J, Hennes H. The anesthetic effectiveness of lidocaine-adrenaline-tetracaine gel on finger lacerations. Pediatr Emerg Care. 2004;20:812–815. doi: 10.1097/01.pec.0000148029.61222.9f. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Anderson K. Towards evidence-based emergency medicine: best BETs from the Manchester Royal Infirmary. BET 1: Comparison of topical anaesthetic agents for minor wound closure in children. Emerg Med J. 2012;29:339–340. doi: 10.1136/emermed-2012-201159.2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Chipont Benabent E, García-Hermosa P, Alió Y, Sanz JL. Suture of skin lacerations using LAT gel. Arch Soc Esp Oftalmol. 2001;76:505–508. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Little C, Kelly OJ, Jenkins MG, Murphy D, McCarron P. The use of topical aneasthesia during repair of minor lacerations Departmnetns of Emergency Medicine: a literature review. Int Emerg Nurs. 2009;17:99–107. doi: 10.1016/j.ienj.2008.10.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Eidelman A, Weiss JM, Lau J, Carr DB. Topical anaesthetics for dermal instrumentation: a systematic review of randomized controlled trials. Ann Emerg Med. 2005;46:343–351. doi: 10.1016/j.annemergmed.2005.01.028. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Ong ME, Chan YH, Teo J, Saroja S, Yap S, Ang PH, et al. Hair apposition technique for scalp lacerations repair: a randomized controlled trial comparing physicians and nurses (HAT 2 study) Am J Emerg Med. 2008;26:433–438. doi: 10.1016/j.ajem.2007.07.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]