Abstract

Purpose

Established in 1994, the Epstein histological criteria (Gleason score 6 or less, 2 or fewer cores positive and 50% or less of any core) have been widely used to select men for active surveillance. However, with the advent of targeted biopsy, which may be more accurate than conventional biopsy, we reevaluated the likelihood of reclassification upon confirmatory rebiopsy using multiparametric magnetic resonance imaging-ultrasound fusion.

Materials and Methods

We identified 113 men enrolled in active surveillance at our institution who met Epstein criteria and subsequently underwent confirmatory targeted biopsy via multiparametric magnetic resonance imaging-ultrasound fusion. Median patient age was 64 years, median prostate specific antigen was 4.2 ng/ml and median prostate volume was 46.8 cc. Targets or regions of interest on multiparametric magnetic resonance imaging-ultrasound fusion were graded by suspicion level and biopsied at 3 mm intervals along the longest axis (median 10.5 mm). Also, 12 systematic cores were obtained during confirmatory rebiopsy. Our reporting is consistent with START (Standards of Reporting for MRI-targeted Biopsy Studies) criteria.

Results

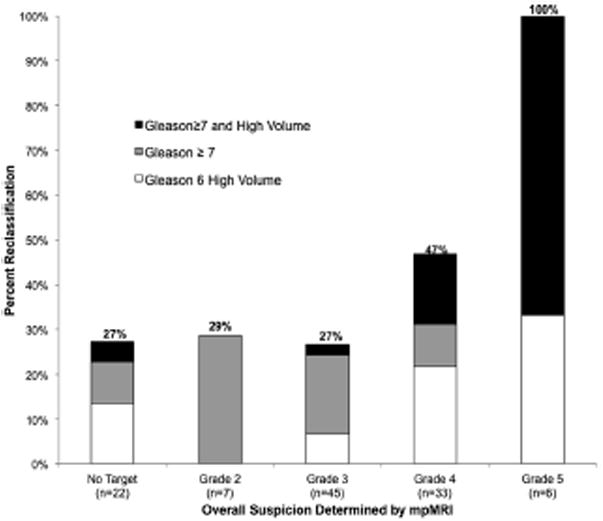

Confirmatory fusion biopsy resulted in reclassification in 41 men (36%), including 26 (23%) due to Gleason grade 6 or greater and 15 (13%) due to high volume Gleason 6 disease. When stratified by suspicion on multiparametric magnetic resonance imaging-ultrasound fusion, the likelihood of reclassification was 24% to 29% for target grade 0 to 3, 45% for grade 4 and 100% for grade 5 (p = 0.001). Men with grade 4 and 5 vs lower grade targets were greater than 3 times more likely to be reclassified (OR 3.2, 95% CI 1.4–7.1, p = 0.006).

Conclusions

Upon confirmatory rebiopsy using multiparametric magnetic resonance imaging-ultrasound fusion men with high suspicion targets on imaging were reclassified 45% to 100% of the time. Criteria for active surveillance should be reevaluated when multiparametric magnetic resonance imaging-ultrasound fusion guided prostate biopsy is used.

Keywords: prostate, prostatic neoplasms, patient selection, ultrasonography, magnetic resonance imaging

The Epstein criteria have been widely used for 2 decades to define clinically insignificant prostate cancer and assign eligibility for active surveillance.1 Epstein et al noted that certain biopsy criteria (no Gleason 4 component, no more than 2 cores involved and no core with more than 50% involvement) predicted low risk findings in radical prostatectomy specimens. The biopsy material that they studied was obtained by the random, systematic US guided technique.3 However, with the advent of mpMRI guided biopsy and specific sampling of regions of interest prostate cancer risk inflation may change the predictive significance of tissue findings in biopsy cores obtained by the new method.4

In a computer simulation model Robertson et al found that cancer core length and the percent of positive cores were theoretically greater using a targeted approach compared to a conventional systematic method.4 Hoeks et al recently reported that conventionally diagnosed prostate cancer was often upgraded when in bore mpMRI biopsy of a specific region of interest was subsequently performed. Mullins et al noted that mpMRI accurately identified an index lesion in men selected for active surveillance by conventional biopsy.6 In a nonbiopsy study Turkbey et al observed that mpMRI would have been helpful to identify men for active surveillance based on imaging correlations with radical prostatectomy findings.7 Others also examined mpMRI in the confirmatory biopsy setting and found that the number of lesions, lesion suspicion and density were associated with reclassification.8,9

We examined the usefulness of mpMRI-US confirmatory biopsy in men initially diagnosed with prostate cancer who were eligible for active surveillance, that is they met the Epstein criteria. The Epstein criteria were considered the existing standard for active surveillance and served as the main reference point.

Methods

Study subjects were all 113 men prospectively enrolled in the UCLA active surveillance program who met Epstein histological criteria for low risk prostate cancer at initial diagnosis from March 2010 to March 2013 and subsequently underwent confirmatory biopsy via mpMRI-US. Initial diagnostic biopsies were performed by a number of board certified urologists using various methods during the 2 years before study inception. Most biopsies were 12 core samplings. The primary study outcome was reclassification beyond Epstein histological criteria (Gleason score 6 or less, 2 or fewer cores positive and 50% or less of any core.) All biopsy materials thus obtained were reviewed independently by an experienced urological pathologist (JH). Our reporting is consistent with START guidelines.10

Our technique of mpMRI and mpMRi-US biopsy was previously described.11 Briefly, patients underwent mpMRI on a 3 Tesla Somatom magnet (Siemens®) using a multichannel external phased array coil. A uroradiologist (DJM) with 10 years of experience with reading prostate mpMRI who was blinded to initial diagnostic biopsy results and positive core sites at initial diagnostic biopsy assigned an image grade of 1 to 5 to regions of interest with higher scores indicating more suspicious regions.12 mpMRI was performed 1 to 3 weeks before mpMRI-US biopsy.

Table 1 shows the UCLA scoring system, which was established in 2010 and is similar to ESUR PI-RADS.13 The ESUR PI-RADS and UCLA reporting systems are standardized but there are 2 main differences. 1) ESUR PI-RADS uses qualitative evaluation of diffusion imaging and the UCLA system uses the quantitative apparent diffusion coefficient based on a series of cases with the same scanner platform and pulse sequence parameters. 2) ESUR PI-RADS weights T2 appearance, diffusion and perfusion equally while the UCLA system weights diffusion twice as much as appearance and diffusion.

Table 1. UCLA image scoring system for regions of interest on mpMRI.

| Image Grade | T2-Weighted Imaging | Apparent Diffusion Coefficient (× 10−3 mm2/sec) | Dynamic Contrast Enhancement |

|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | Normal | Greater than 1.2 | Normal |

| 2 | Faint decreased signal | 1.0–1.2 | Mildly abnormal |

| 3 | Moderately dark nodule | 0.8–1.0 | Moderately abnormal |

| 4 | Intensely dark nodule | 0.6–0.8 | Highly abnormal |

| 5 | Dark nodule with mass effect | Less than 0.6 | Profoundly abnormal |

Reprinted with permission from Urologic Oncology.11

Delineated mpMRI images were recorded and entered into the Artemis device (Eigen, Grass Valley, California) at the outset of a fusion biopsy session. Men with image grade 2 or greater targets on mpMRI underwent targeted biopsies with 1 core obtained at approximately every 3 mm along the longest axis of the target before systematic sampling.11 One patient with a grade 2 target and none with a grade 1 target did not undergo targeted biopsy because preliminary data indicated that such targets were no more likely to contain cancer than systematic biopsies. When multiple cores were obtained from a target, the single most involved core (maximal percent involvement and highest Gleason score) was used for analysis. After targeted biopsy the men underwent sampling of 12 systematic sites preselected by the Artemis device that were independent of the mpMRI result. All biopsies were performed by a single urologist (LSM) with a conventional spring-loaded gun and 18 gauge needles.

Descriptive statistics were used to summarize patient characteristics (table 2). Correlations between continuous variables were made using the nonparametric Spearman rank correlation. Our main outcomes of interest were factors associated with reclassification beyond the Epstein criteria using confirmatory mpMRI-US biopsy. Stepwise multivariate logistic regression was performed to create a parsimonious model that accounted for all relationships between covariates and reclassification beyond the Epstein criteria. Sensitivity analysis based on earlier data revealed that the likelihood of reclassification was similar in men with no targets and those with grade 2 or 3 targets. Therefore, these men were combined as the reference group. Covariates were selected a priori based on clinical relevance, including clinical stage, PSA density, number of positive cores (1 vs 2), maximal percent core involvement at diagnostic biopsy and mpMRI grade at confirmatory biopsy. We did not include PSA in the model because of collinearity with PSA density. All calculations were performed by a biostatistician (FJD) using Stata®, version 11. The study was approved by the UCLA institutional review board.

Table 2. Characteristics of 113 men undergoing mpMRI-US confirmatory biopsy.

| Median age (IQR) | 63 | (58–68) |

| Median ng/ml PSA (IQR) | 4.2 | (2.6–6.3) |

| Median cc US prostate vol (IQR) | 46.8 | (36.1–64.5) |

| Median ng/cc PSA density (IQR) | 0.08 | (0.05–0.14) |

| Median kg/m2 body mass index (IQR) | 26.3 | (23.7–28.9) |

| No. race (%): | ||

| White | 88 | (78) |

| Black | 7 | (6) |

| Asian | 8 | (7) |

| Hispanic | 6 | (5) |

| Other | 4 | (4) |

Results

Table 2 shows the clinical characteristics of the 113 men. None of these men were included in prior studies. Diagnostic biopsies were performed in various community settings and without standardization by board certified urologists. Most biopsies were done using a 12-core template. A total of 68 men (77%) were diagnosed with 1 positive core while 36 had 2 positive cores (32%). All 113 men had Gleason 6 lesions and all fulfilled the 1994 Epstein criteria for indolent prostate cancer.2

Confirmatory biopsy was performed a median of 10 months (IQR 6–19) after prostate cancer diagnosis. No relationship was found between the interbiopsy interval and the likelihood of reclassification. Targets of varying degrees of suspicion (2 or 3 vs less than 4 vs 5) were identified on mpMRI in 91 men (80.5%) with a median of 2 targets (IQR 1–2) per patient. As measured by the longest axis, median target size was 10.5 mm (range 4 to 32). There was no discernible target in 22 men. A median of 16 cores (IQR 14–18) was sampled at confirmatory biopsy, consisting of 12 systematic and 4 targeted biopsies. On confirmatory biopsy 38 men (33.6%) had no prostate cancer, 35 (31.0%) had prostate cancer fulfilling the Epstein criteria and 41 (36.3%) were reclassified beyond the Epstein criteria.

Of men reclassified beyond the Epstein criteria 26 (23%) were reclassified due to Gleason grade 7 or greater and 15 (13.3%) were reclassified due to higher volume Gleason 6 disease (table 3). Men with mpMRI image grade 4 or 5 were more often reclassified than those with mpMRI grade 2 or 3 (OR 3.2, 95% CI 1.4–7.1, p = 0.006). A 0.10 U increase in PSA density (OR 2.41, 95% CI 1.28, 4.53) was associated with reclassification. Reclassification was done in 27.0% of men with mpMRI grade 0 to 3, 46.9% with grade 4 and 100% with grade 5 (see figure). The likelihood of reclassification was similar in men with no targets and those with mpMRI grade 2 and 3 targets (27% to 29%). Finally, consistent with START guidelines,10 we performed cross tabulation of insignificant (Gleason score 3 + 3 = 6) and significant (any Gleason score 3 + 4 = 7 or higher) cancer detection by targeted vs systematic biopsies in 90 men who underwent each biopsy type (table 4). Systematic and targeted biopsy results were concordant in 50% of cases. However, targeted biopsy detected significant cancer in 3 men (3%) deemed without cancer by systematic biopsy while systematic biopsy detected significant cancer in 10 (11%) in whom targeted biopsy showed no cancer (table 4).

Table 3. Reasons for reclassification beyond Epstein criteria in 113 men undergoing mpMRI-US confirmatory biopsy.

| Upgrade | No. Pts (%) |

|---|---|

| Gleason score | 15 (13) |

| Tumor vol: | 15 (13) |

| 50% or Greater max involvement | 2 (2) |

| Greater than 2 cores pos | 9 (8) |

| 50% or Greater max involvement + greater than 2 cores pos | 4 (3) |

| Gleason 7 or greater + high tumor vol | 11 (10) |

|

|

|

| Total | 41 (36) |

Effect of MRI grade on reclassification beyond Epstein criteria using mpMRI-US biopsy.

Table 4. Systematic plus targeted biopsy at same biopsy session in 90 men.

| Targeted Prostate Biopsy | No. Systematic Prostate Biopsy (%) | ||

|---|---|---|---|

|

| |||

| No Ca | Insignificant Ca | Significant Ca | |

| No Ca | 26 (29) | 20 (22) | 10 (11) |

| Insignificant Ca | 8 (9) | 13 (14) | 1 (1) |

| Significant Ca | 3 (3) | 2 (2) | 7 (8) |

Discussion

In the current study men undergoing conventional prostate biopsy who had low risk prostate cancer by the 1994 Epstein criteria also underwent confirmatory rebiopsy by mpMRI-US.11,12 Confirmatory biopsies performed by the new method resulted in a major increase in Gleason score and tumor volume compared to those found on initial diagnostic biopsy using conventional methods. In other studies using conventional confirmatory biopsy reclassification beyond the Epstein criteria was described in 2.5% to 22% of men.14,15 In our series using a MRI/US fusion method of confirmation we found a reclassification rate of 36% beyond the Epstein criteria. Reclassification was directly related to the degree of suspicion on MRI. Thus, these data suggest that mpMRI targeting yields confirmatory results different (ie more sensitive) than those of conventional biopsy methods of cancer detection.

PSA density at initial diagnosis was directly related to the chance of reclassification at confirmatory biopsy. Kotb et al reported that PSA density greater than 0.15 ng/ml16 and San Francisco et al reported that PSA density greater than 0.08 ng/ml were associated with the risk of progression on subsequent biopsy.16,17 In the current study we did not use PSA density to determine eligibility for active surveillance, consistent with other active surveillance series.14,15,18,19 However, the significant association of PSA density and reclassification on confirmatory biopsy in our series and others suggests that it should be considered for active surveillance eligibility and monitoring during followup.

Walsh was among the first to suggest that prostate imaging could improve prior methods of prostate cancer risk stratification.20 Fradet21 and Vargas22 et al reported that a suspicious lesion on mpMRI in men undergoing active surveillance for low risk prostate cancer was associated with a substantial increase in subsequent upgrading. Turkbey et al reviewed the records of 133 men who underwent radical prostatectomy and found that preoperative mpMRI results compared favorably with other indexes, eg Epstein, D'Amico and CAPRA (Cancer of the Prostate Risk Assessment), to predict low risk disease status.7 The current data support these earlier findings with actual biopsy information obtained under MRI guidance.

Hoeks et al compared mpMRI guided, in bore biopsy within 3 months of enrollment to active surveillance and found that 12 of 64 cases (19%) were restratified.5 Using cognitive fusion biopsy Margel et al noted a 17.9% reclassification rate.23 In the current series using the Artemis device for mpMRI-US biopsy we found a 36% reclassification rate. Thus, the current results using fusion biopsy in a clinic setting compare favorably with those of other methods of targeted biopsy during active surveillance and call into question the use of existing histological criteria to assess low risk when biopsy is performed via mpMRI guidance.

The current upgrading results approach those of the ultimate confirmatory evaluation of radical prostatectomy specimens. Jeldres et al reported that 26.2% of European men who met the Epstein criteria at diagnosis were reclassified to Gleason 7 or greater at radical prostatectomy and 8.3% had nonorgan confined disease.24 In a similar series from the Cleveland Clinic Lee et al found that 40% of men who met the Epstein criteria were reclassified with Gleason 7 or greater disease at radical prostatectomy and 8.0% had nonorgan confined disease.25 While radical prostatectomy findings were not available in our series, the reclassification rate using targeted biopsy approaches previously reported whole organ findings.

When reclassification is found using conventional biopsy in men enrolled in active surveillance, this change may be explained by sampling error in the original biopsy. Sampling error may be decreased by targeting suspicious lesions noted on mpMRI. For example, in the current series when the most highly suspicious lesions were targeted, the reclassification rate was 100% for image grade 5 lesions and 45% for image grade 4 lesions. Had these lesions been targeted initially rather than at confirmatory biopsy a correct original classification may have been possible. These findings suggest the early use of targeted biopsy in active surveillance programs to help confirm low risk disease. Wong et al suggested that conventional confirmatory biopsy may not establish low risk to the extent previously believed.26 Early and correct risk assessment would help avoid treatment delay and spare many men the repeat biopsy sessions needed to determine true disease status.

Our data do not support substituting mpMRI for prostate biopsy except possibly in men with grade 5 targets, of whom all harbored tumors of more than low risk. Biopsy of lower grade targets was associated with lower cancer detection rates. However, systematic biopsy revealed significant cancer in 10 men (11%) in whom targeted biopsy showed no cancer while targeted biopsy detected significant cancer in 3 (3%) in whom systematic biopsy showed no cancer. Others suggested that the mpMRI false-negative rate approaches zero in men who meet active surveillance criteria5,22 but the current data indicate otherwise. Reasons for the differences are unclear since the mpMRI technique used by our group is similar to that used by groups who reported low false-negative rates. Perhaps more extensive PSA screening in the United States has resulted in smaller lesions than in Europe, where PSA screening has not been as widely done, ie a left shift has occurred. Until the false-negative rate of mpMRI is clarified systematic and targeted biopsy should be done.

Using the Epstein criteria, which were published in the era of blind systematic biopsy, if more than 2 cores are involved, the patient would be excluded from active surveillance. However, using targeted biopsy if multiple cores are taken from a reliable mpMRI target, the probability of finding more than 2 positive cores increases. This may be true for exceeding the Epstein rule of 50% of a core and it may also be true for finding small secondary foci of Gleason pattern 4 (another exclusion by the earlier criteria). The current findings are consonant with recent findings by Reese et al suggesting that an increased number of Gleason 6 positive cores should not exclude active surveillance.27

Our findings must be interpreted in the context of the study design. 1) The study was retrospective and observational in nature, and not a randomized, controlled trial comparing conventional transrectal US vs mpMRI-US biopsies. Some of the 113 men may not have undergone full 12-core sampling at initial diagnostic biopsy, which could have led to an increased number of reclassification events at confirmatory biopsy. 2) We had limited followup to assess the negative rate in men not reclassified beyond the Epstein criteria. Radical prostatectomy confirmation was not available. Other fusion biopsy systems are available and the effect of targeted biopsy using these systems may be different than what we observed. Despite these limitations upgrading beyond the Epstein criteria was a frequent finding with targeted biopsy and would have eliminated 36% of men from active surveillance. Whether such upgrades represent progression or simply initial under sampling was recently addressed by Penney et al.28 Reevaluation of traditional biopsy criteria for active surveillance should be considered when targeted prostate biopsy is performed.

The results of our study raise several questions. Should Gleason 6 volume criteria be liberalized when targeted biopsy is used? Should small amounts of Gleason 3 + 4 = 7 detected in MRI targets now be considered an acceptable criterion for men to enter active surveillance? Should targeted biopsy be done before enrollment in active surveillance? Efforts to answer these questions are currently in progress by studying MRI-US targeted biopsy results in men who subsequently undergo radical prostatectomy.

Conclusions

In men initially diagnosed with low risk prostate cancer mpMRI-US confirmatory biopsy, including targeting suspicious lesions seen on MRI, resulted in frequent detection of tumors exceeding the Epstein criteria. These data suggest that the Epstein criteria be reevaluated in men enrolling in active surveillance to account for the risk inflation seen with targeted prostate biopsy.

Acknowledgments

Supported by the Beckman Coulter Foundation, Jean Perkins Foundation, Steven C. Gordon Family Foundation and National Cancer Institute Award R01CA158627.

Abbreviations and Acronyms

- ESUR PI-RADS

European Society of Urogenital Radiology Prostate Imaging Reporting and Data System

- mpMRI

multiparametric MRI

- mpMRI-US

mpMRI-US fusion

- MRI

magnetic resonance imaging

- PSA

prostate specific antigen

- START

Standards of Reporting for MRI-targeted Biopsy Studies

- US

ultrasound

Footnotes

The content is solely the responsibility of the authors and does not necessarily represent the official views of the National Cancer Institute or National Institutes of Health.

References

- 1.Dall'era MA, Albertsen PC, Bangma C, et al. Active surveillance for prostate cancer: a systematic review of the literature. Eur Urol. 2012;62:976. doi: 10.1016/j.eururo.2012.05.072. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Epstein JI, Walsh PC, Carmichael M, et al. Pathologic and clinical findings to predict tumor extent of nonpalpable (stage T1c) prostate cancer. JAMA. 1994;271:368. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Hodge KK, McNeal JE, Terris MK, et al. Random systematic versus directed ultrasound guided transrectal core biopsies of the prostate. J Urol. 1989;142:71. doi: 10.1016/s0022-5347(17)38664-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Robertson NL, Hu Y, Ahmed HU, et al. Prostate cancer risk inflation as a consequence of image-targeted biopsy of the prostate: a computer simulation study. Eur Urol. 2014;65:628. doi: 10.1016/j.eururo.2012.12.057. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Hoeks CM, Somford DM, van Oort IM, et al. Value of 3-T multiparametric magnetic resonance imaging and magnetic resonance-guided biopsy for early risk restratification in active surveillance of low-risk prostate cancer: a prospective multi-center cohort study. Invest Radiol. 2014;49:165. doi: 10.1097/RLI.0000000000000008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Mullins JK, Bonekamp D, Landis P, et al. Multiparametric magnetic resonance imaging findings in men with low-risk prostate cancer followed using active surveillance. BJU Int. 2013;111:1037. doi: 10.1111/j.1464-410X.2012.11641.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Turkbey B, Mani H, Aras O, et al. Prostate cancer: can multiparametric MR imaging help identify patients who are candidates for active surveillance? Radiology. 2013;268:144. doi: 10.1148/radiol.13121325. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Somford DM, Hoeks CM, Hulsbergen-van de Kaa CA, et al. Evaluation of diffusion-weighted MR imaging at inclusion in an active surveillance protocol for low-risk prostate cancer. Invest Radiol. 2013;48:152. doi: 10.1097/RLI.0b013e31827b711e. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Stamatakis L, Siddiqui MM, Nix JW, et al. Accuracy of multiparametric magnetic resonance imaging in confirming eligibility for active surveillance for men with prostate cancer. Cancer. 2013;119:3359. doi: 10.1002/cncr.28216. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Moore CM, Kasivisvanathan V, Eggener S, et al. Standards of reporting for MRI-targeted biopsy studies (START) of the prostate: recommendations from an International Working Group. Eur Urol. 2013;64:544. doi: 10.1016/j.eururo.2013.03.030. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Natarajan S, Marks LS, Margolis DJ, et al. Clinical application of a 3D ultrasound-guided prostate biopsy system. Urol Oncol. 2011;29:334. doi: 10.1016/j.urolonc.2011.02.014. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Sonn GA, Natarajan S, Margolis DJ, et al. Targeted biopsy in the detection of prostate cancer using an office based magnetic resonance ultrasound fusion device. J Urol. 2013;189:86. doi: 10.1016/j.juro.2012.08.095. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Barentsz JO, Richenberg J, Clements R, et al. ESUR prostate MR guidelines 2012. Eur Radiol. 2012;22:746. doi: 10.1007/s00330-011-2377-y. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Soloway MS, Soloway CT, Eldefrawy A, et al. Careful selection and close monitoring of low-risk prostate cancer patients on active surveillance minimizes the need for treatment. Eur Urol. 2010;58:831. doi: 10.1016/j.eururo.2010.08.027. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Berglund RK, Masterson TA, Vora KC, et al. Pathological upgrading and up staging with immediate repeat biopsy in patients eligible for active surveillance. J Urol. 2008;180:1964. doi: 10.1016/j.juro.2008.07.051. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Kotb AF, Tanguay S, Luz MA, et al. Relationship between initial PSA density with future PSA kinetics and repeat biopsies in men with prostate cancer on active surveillance. Prostate Cancer Prostatic Dis. 2011;14:53. doi: 10.1038/pcan.2010.36. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.San Francisco IF, Werner L, Regan MM, et al. Risk stratification and validation of prostate specific antigen density as independent predictor of progression in men with low risk prostate cancer during active surveillance. J Urol. 2011;185:471. doi: 10.1016/j.juro.2010.09.115. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Klotz L, Zhang L, Lam A, et al. Clinical results of long-term follow-up of a large, active surveillance cohort with localized prostate cancer. J Clin Oncol. 2010;28:126. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2009.24.2180. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Dall'Era MA, Konety BR, Cowan JE, et al. Active surveillance for the management of prostate cancer in a contemporary cohort. Cancer. 2008;112:2664. doi: 10.1002/cncr.23502. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Walsh PC. Perfecting nerve-sparing radical prostatectomy: sailing in uncharted waters. Can J Urol. 2008;15:4230. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Fradet V, Kurhanewicz J, Cowan JE, et al. Prostate cancer managed with active surveillance: role of anatomic MR imaging and MR spectroscopic imaging. Radiology. 2010;256:176. doi: 10.1148/radiol.10091147. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Vargas HA, Akin O, Afaq A, et al. Magnetic resonance imaging for predicting prostate biopsy findings in patients considered for active surveillance of clinically low risk prostate cancer. J Urol. 2012;188:1732. doi: 10.1016/j.juro.2012.07.024. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Margel D, Yap SA, Lawrentschuk N, et al. Impact of multiparametric endorectal coil prostate magnetic resonance imaging on disease reclassification among active surveillance candidates: a prospective cohort study. J Urol. 2012;187:1247. doi: 10.1016/j.juro.2011.11.112. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Jeldres C, Suardi N, Walz J, et al. Validation of the contemporary epstein criteria for insignificant prostate cancer in European men. Eur Urol. 2008;54:1306. doi: 10.1016/j.eururo.2007.11.057. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Lee MC, Dong F, Stephenson AJ, et al. The Epstein criteria predict for organ-confined but not insignificant disease and a high likelihood of cure at radical prostatectomy. Eur Urol. 2010;58:90. doi: 10.1016/j.eururo.2009.10.025. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Wong LM, Alibhai SM, Trottier G, et al. A negative confirmatory biopsy among men on active surveillance for prostate cancer does not protect them from histologic grade progression. Eur Urol. 2013 May 2; doi: 10.1016/j.eururo.2013.04.038. Epub ahead of print. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Reese AC, Landis P, Han M, et al. Expanded criteria to identify men eligible for active surveillance of low risk prostate cancer at Johns Hopkins: a preliminary analysis. J Urol. 2013;190:2033. doi: 10.1016/j.juro.2013.05.015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Penney KL, Stampfer MJ, Jahn JL, et al. Gleason grade progression is uncommon. Cancer Res. 2013;73:5163. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-13-0427. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]