Abstract

Background

Treatment non-adherence in people with schizophrenia is associated with relapse and homelessness. Building upon the usefulness of long-acting medication, and our work in psychosocial interventions to enhance adherence, we conducted a prospective uncontrolled trial of customized adherence enhancement (CAE) plus long-acting injectable antipsychotic (LAI) using haloperidol decanoate in 30 homeless or recently homeless individuals with schizophrenia and schizoaffective disorder.

Methods

Participants received monthly CAE and LAI (CAE-L) for 6 months. Primary outcomes were adherence as measured by the Tablets Routine Questionnaire (TRQ) and housing status. Secondary outcomes included psychiatric symptoms, functioning, side effects, and hospitalizations.

Results

Mean age of participants was 41.8 years (SD 8.6), mainly minorities (90% African-American) and mainly single/never married (70%). Most (97%) had past or current substance abuse, and had been incarcerated (97%). Ten individuals (33%) terminated the study prematurely. CAE-L was associated with good adherence to LAI (76% at 6 months) and dramatic improvement in oral medication adherence, which changed from missing 46% of medication at study enrollment to missing only 10% at study end (p = 0.03). There were significant improvements in psychiatric symptoms (p<.001) and functioning (p<.001). Akathisia was a major side effect with LAI.

Conclusion

While interpretation of findings must be tempered by the methodological limitations, CAE-L appears to be associated with improved adherence, symptoms, and functioning in homeless or recently homeless individuals with schizophrenia or schizoaffective disorder. Additional research is needed on effective and practical approaches to improving health outcomes for homeless people with serious mental illness.

Keywords: Homelessness, schizophrenia, schizoaffective disorder, treatment adherence, antipsychotic medication, haloperidol

Introduction

While psychotropic medications are a cornerstone of treatment for individuals with schizophrenia, rates of non-adherence can exceed 60%. 1, 2, 3 Poor adherence is associated with homelessness.4, 5, 6 A review in homeless persons found the weighted average prevalence of schizophrenia in homeless individuals is 11%, and that approximately half of these individuals are not receiving treatment. 6 Because a major obstacle to medication adherence is difficulty with medication routines, 1, 7 long-acting injectable antipsychotic (LAI) medication can be an attractive treatment option. However, LAI is underused for schizophrenia,8 and less than one in five individuals with non-adherence receive LAIs8.

Building upon work by these investigators in psychosocial interventions to enhance adherence, 9, 10 we conducted a trial of customized adherence enhancement (CAE) plus LAI antipsychotic (CAE-L) in 30 homeless or recently homeless individuals with schizophrenia and schizoaffective disorder. We anticipated that CAE-L would be associated with reduced rates of homelessness, improved adherence and reduced psychiatric symptoms.

Methods

This was a prospective, uncontrolled trial of CAE-L in non-adherent, homeless or recently homeless individuals with schizophrenia and schizoaffective disorder. CAE-L was administered monthly over 6 months. Primary study outcomes were medication adherence, as measured with the Tablet Routines Questionnaire (TRQ 11, 12) and housing status. Secondary outcomes included psychiatric symptoms, functioning, side effects, hospitalizations, and treatment satisfaction. Post-treatment follow-up was conducted at 9 and 12 months.

Study Population

Study participants were age ≥18, with a DSM diagnosis of schizophrenia or schizoaffective disorder confirmed with the Mini International Neuropsychiatric Inventory (MINI 13). Individuals were recruited from homeless shelters, community mental health clinics (CMHCs), and the community. The study was approved by the local Institutional Review Board (IRB) and oversight included an external Data and Safety Monitoring Board (DSMB). All participants provided written informed consent. Individuals had poor adherence (missing 20% or more of prescribed medication) as measured by the Tablets Routine Questionnaire (TRQ) 11,12, and were currently homeless or had been homeless within the past 12 months as per the Federal definition of homelessness. 14 Participants had to be willing to take LAI.

Individuals were excluded if they had known contra-indication to haloperidol, were on LAI at screening, had prior treatment with clozapine, substance dependence, unstable medical conditions, or were at high risk of harm to self or others. Individuals already in permanent supported housing that included comprehensive mental health services were excluded. The study was conducted from July 2010 to December 2012.

The CAE-L intervention

LAI: Haloperidol decanoate was chosen as the LAI, given its low cost and potential generalizability. Individuals already on oral haloperidol were switched to LAI as per the manufacturer’s package insert. 15 Individuals not on any antipsychotic or on antipsychotics other than haloperidol at screening were started on oral haloperidol (2 mg twice daily) and then transitioned to LAI within 2–3 weeks of enrollment. Individuals received LAI every 4 weeks for the duration of the study. Subsequent dose modification was based on clinical status.

Customized adherence enhancement: Customized Adherence Enhancement (CAE), originally designed for non-adherent bipolar patients,9, 10 targets key areas also relevant to non-adherent individuals with schizophrenia and includes psychoeducation focused on medication, developing medication routines, communicating with providers about benefits and burdens of medications, and managing adherence in the context of substance abuse. Detailed information on CAE is described in greater detail elsewhere.9,10

Modifications of CAE for use in individuals with schizophrenia included reducing the duration of sessions (generally ranging from 30-40 minutes), repetition of key messages, either completing only half of the material from a session that would have been covered with bipolar patients or repeating the material a second time in two consecutive sessions to reinforce the key points, and increasing overall number of sessions (8 sessions, generally given at one month intervals on the day that LAI was administered).

Concomitant treatments

Antipsychotic drugs other than haloperidol were discontinued. Stable doses of psychotropic drugs other than antipsychotics were continued through the course of the study. New psychotropic medications were strongly discouraged. Medications for side effects were given at the discretion of the treating psychiatrist.

Study Assessments

Individuals completed assessments at screening (time of oral antipsychotic drug initiation), CAE-L baseline (first administration of LAI or first CAE session) and at 13 and 25 weeks follow-up. All study participants received nominal financial compensation for research assessments but did not receive compensation for other components of study participation.

Primary Outcomes

Primary outcomes were change from screening on the TRQ 11, 12 and on housing status. Housing status was grouped in progressively less desirable order: permanent housing without assistance, permanent housing with some assistance, transitional housing, short-term/emergency shelter, outdoors, and incarceration. The TRQ format was modified slightly to document adherence values as an exact proportion.

Secondary outcomes

Adherence was also assessed with the Morisky Rating Scale 16 and observed injection frequency of LAI (proportion of injections given within 7 days of the scheduled time). Adherence attitudes were assessed with the Attitude toward Medication Questionnaire (AMQ 12,17) which was slightly adapted to include prescribed psychotropic medication, and the Drug Attitude Inventory (DAI18).

Secondary outcomes included health resource use (hospitalizations), psychiatric symptoms as assessed by the Brief Psychiatric Rating Scale (BPRS 19), Positive and Negative Syndrome Scale (PANSS 20) and the Clinical Global Impression (CGI 21). Substance abuse and legal status were measured with the Addiction Severity Index (ASI 22,23). Functioning was measured with the Social and Occupational Functioning Assessment Scale (SOFAS 24). Satisfaction with CAE-L was assessed at the conclusion of the 6 month treatment period.

All outcome assessments were conducted at screening, baseline, Week 13, and at Week 25, except for satisfaction with treatment, PANSS, and life and work functioning, which were conducted at the CAE-L baseline and Week 25 visits. After the 25-week treatment, participants continued to receive care in their CMHC or indigent care organizations, and treatment history was communicated to providers at these sites. We conducted limited post-treatment follow-up at 9 and 12 months, which included the CGI.

Safety measures

Biological and safety outcomes included body mass index (BMI), vital signs, and laboratory testing. Laboratory testing was conducted at screening and week 25. A 12-lead Electrocardiogram (EKG) was assessed at screening. Involuntary movements were evaluated with the Abnormal Involuntary Movement Scale (AIMS 21), Simpson Angus Scale (SAS 25), and Barnes Akathisia Rating Scale (BARS 26), conducted at screening, baseline and week 25. Participants were assessed for side effects at every study visit.

Data analysis

Descriptive statistics were calculated for baseline characteristics. We conducted a modified intent-to-treat analysis that included all subjects who received at least one dose of LAI or one CAE session. Statistical analysis was performed using SPSS software version 20 (IBM Corporation, NY). In a first analysis, time- to- event data for LAI dropout were modeled using Kaplan-Meier estimation. A Cox proportional hazard model was then fit on the same time- to -event data, to assess what variables might be affecting dropout. Explanatory variables that were considered included age, gender, and personality disorder. Having antisocial personality disorder (ASPD) was found to be significantly related to hazard rate, with higher hazard for those with ASPD. Thus, ASPD status was included in subsequent longitudinal mixed models of the BPRS, DAI, and Morisky scales.

Mixed models for BPRS, DAI, and Morisky scales considered time of measurement as a categorical variable, either at baseline, 13 weeks, or 25 weeks. It was of interest to test whether there appeared to be differences in the factor levels associated with time of measurement which would indicate that there was indeed change over time in the outcome variables subsequent to CAE-L. A random intercept model was adopted, with ASPD status included as an explanatory factor. AR (1) error covariance structures were fit.

Results

Screened and enrolled samples

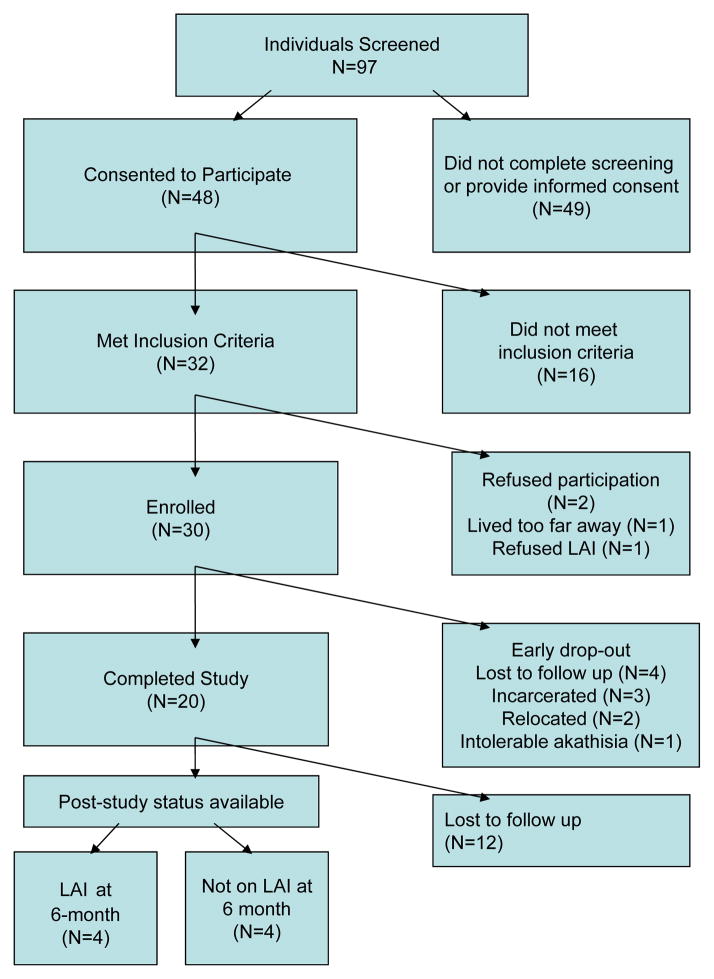

Figure 1 illustrates a CONSORT diagram of participants in the study. Of 97 individuals screened for the study, 48 consented to participate. Among those, 32 individuals met inclusion criteria and 30individuals were enrolled. Age, gender, and race did not differ significantly between screened and enrolled patients. Table 1 illustrates demographic and clinical variables in enrolled individuals. Of note were the relatively high proportion of minorities (90% African-American), single/never married individuals (70%) and relatively low levels of education (most did not finish high school). Nearly all (97%) had a history of past or current substance abuse, and nearly all had past incarceration (97%). In the 6 months prior to study enrollment, participants spent 44% of their time in emergency shelter/short-term housing. On average, individuals missed approximately half of prescribed psychotropic medication.

Figure 1.

CONSORT Diagram of participation in a study of customized adherence enhancement plus long-acting injectable antipsychotic (LAI).

Table 1.

Clinical characteristics of 30 non-adherent homeless/recently homeless individuals with schizophrenia or schizoaffective disorder

| Variable | Screening Value | Baseline Value |

|---|---|---|

|

| ||

| Age in years Mean (SD -- Range) | 41.8 (8.6 --22–54) | |

|

| ||

| Female N (%) | 14 (46.7) | |

|

| ||

| Race N (%) | ||

| White | 3 (10) | |

| Black | 27 (90) | |

|

| ||

| Hispanic ethnicity N (%) | 2 (6.7) | |

|

| ||

| Education in years Mean (SD -- Range) | 11.2 (1.9 --8–15) | |

|

| ||

| Marital Status N (%) | ||

| Single, never married | 21 (70) | |

| Married | 2 (6.7) | |

| Separated/Divorced/Widowed | 7 (23.3) | |

|

| ||

| Type of Illness N (%) | ||

| Schizophrenia | 10 (33) | |

| Schizoaffective disorder | 20 (67) | |

| Bipolar sub-type | 18 (89) | |

| Depressive sub-type | 2 (11) | |

|

| ||

| Age at onset of illness in years | ||

| Mean (SD) | 24.1 (10.5) | |

| Range (Median) | 22 (41) | |

|

| ||

| TRQ Mean (SD) | ||

| Past Week | 57.2 (6.1) | 20.7 (7.0) (n=23) |

| Past Month | 46.1 (5.7) | 30.1 (8.4) (n=17) |

|

| ||

| Housing status as a proportion of the previous 180 days % | ||

| -Outdoors | 1 | |

| -Short-term/emergency shelter | 44 | |

| -Transitional housing | 6 | |

| -Permanent housing with assistance | 35 | |

| -Permanent housing without assistance | 2 | |

| -Incarceration | 10 | |

|

| ||

| ASI | (n=20) | |

| -Drug Mean (SD) | 0.6 (1.3) | |

| -Legal Mean (SD) | 0.6 (1.3) | |

|

| ||

| Past or current substance abuse | ||

| N (%) | 29 (97) | |

|

| ||

| History of incarceration N (%) | 29 (97) | |

|

| ||

| BMI Mean (SD) | 32.9 (6.6) | |

TRQ: Tablets Routine Questionnaire; ASI: Addiction Severity Index ; BMI: Body Mass Index

LAI

Injections were administered intramuscularly (IM) in the deltoid muscle. Conservative dosing was used to minimize drug-related adverse effects. Mean end-point dose of haloperidol decanoate was 68.0 mg, SD 21.1, range 50-100 mg/monthly injection.

Concomitant medication

Most (N=25, 84%) individuals were able to identify their prescribed antipsychotic medications at the time of enrollment. Individuals were predominantly prescribed atypical antipsychotics (21/25, 84%), with aripiprazole being the most common (6/25, 24%). Four individuals (4/25, 16%) were on typical drugs, including 3 on oral haloperidol and 1 on perphenazine. Table 1 illustrates concomitant (non-antipsychotic) medications such as mood stabilizing drugs (lithium, anticonvulsants) and antidepressants taken by 9 (30%) participants.

CAE components

Based upon results of the standardized adherence needs assessment, 27/30 (90%) individuals were assigned to receive the CAE component that addressed inadequate or incorrect understanding of mental disorder (psychoeducation module); 24/30 (80%) were assigned to receive the CAE component that addressed lack of medication-taking routines (med routine module); 25/30 (83 %) received the CAE component that addressed poor communication with care providers (communication module); 21/30 (70%) were assigned to receive the CAE component that addressed substance use, (Modified motivational interviewing module). Overall, 12 (40%) individuals were assigned to all 4 CAE modules, 14 (47%) assigned to 3 modules, 3 (10%) assigned to 2 modules and 1 individual (3%) assigned to a single CAE module.

Drop-Outs

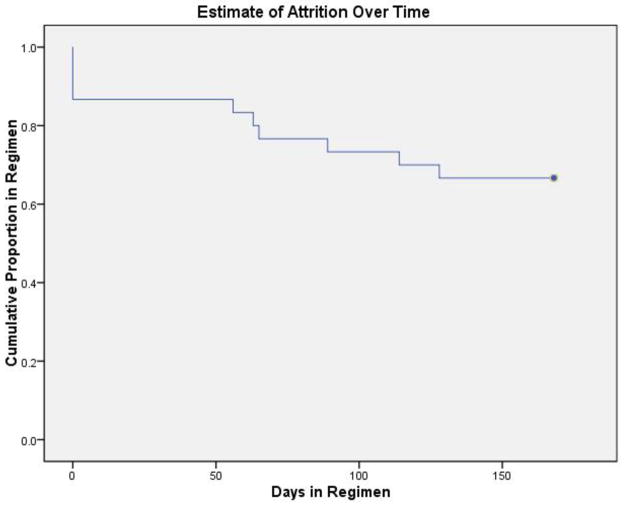

10 individuals (33%) terminated the study prematurely. Reasons for drop out included: 4 (40%) lost to follow-up, 3 (30%) incarcerated, 2 (20%) re-located, and 1 (10%) due to akathisia. Time- to- event data for the dropout from injection treatments were modeled using Kaplan-Meier estimation (Figure 2; Table 2). After 168 days, 66.7% of individuals completed treatment. Most of the dropout occurred immediately after enrollment, with 13.3% of subjects dropping out before receiving a single dose of LAI.

Figure 2.

Kaplan-Meier curve of time to dropout from LAI regimen, corresponding to data from Table 2.

Table 2.

Kaplan-Meier Estimate of Attrition during a 25 -Week (168 Day) Regimen of Long-Acting Injectable Antipsychotic Among 30 Homeless /Recently Homeless Individuals with Schizophrenia or Schizoaffective Disorder

| Time (Days) | Cumulative Proportion Remaining on LAI Regimen at Given Time

|

N of Cumulative Dropouts from | N of Remaining Cases | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Estimate | Std. Error | Regimen | |||

|

|

|||||

| 1 | 0 | .867 | .062 | 4 | 26 |

| 2 | 56 | .833 | .068 | 5 | 25 |

| 3 | 63 | .800 | .073 | 6 | 24 |

| 4 | 65 | .767 | .077 | 7 | 23 |

| 5 | 89 | .733 | .081 | 8 | 22 |

| 6 | 114 | .700 | .084 | 9 | 21 |

| 7 | 128 | .667 | .086 | 10 | 20 |

Total duration of observation: 168 days; 20 subjects continued with LAI regimen for full duration.

Primary and secondary outcome changes

Table 3 illustrates change from screening and baseline in adherence with concomitant oral psychotropic medications, symptoms, housing status, social functioning, as well as LAI adherence. There were significant differences in scores across time periods for nearly all outcome measures. To evaluate change in housing status, we considered the percentage of days in the past months that were spent in sub-optimal housing. A longitudinal mixed model was fit, with time of measurement as a factor, along with APSD status and random subject-level intercept. Age and gender were not statistically significant variables, and hence were not included in the reported model. We considered the estimated TRQ means from screen, 13 weeks, and 25 weeks as 56.31%, 39.88% and 11.82% respectively. Within the mixed model, the test of equality across time periods had a p-value of 0.001, which supports rejection of the null hypothesis that the time periods have equal means. Hence, these differences are statistically significant. Table 3 also illustrates significant improvement in symptoms (BPRS, PANSS, CGI), substance/legal status (ASI drug, ASI legal) and functioning (SOFAS). There were no significant changes in hospitalizations.

Table 3.

Change in Treatment Adherence Behavior (TRQ, Morisky, Injection frequency), Treatment Attitudes (AMQ, DAI), Psychiatric Symptoms (BPRS, PANSS, CGI), and Functional status (SOFAS) among 30 Homeless or Recently Homeless individuals with Schizophrenia or Schizoaffective Disorder

| Variable | Screen a | Baseline a | Wk 13 | Wk 25 | N | Statistic |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

| ||||||

| TRQ Mean (SD) b | ||||||

| Past Week | 57.2 (33.2) | 12.4 (17.3) | 13.9 (31.4) | 10 | 0.047 | |

| Change from baseline (mean 95% CL) | -42.9 (−60.6, −25.2) | −38.9 (−75.7, −2.0) | 10 | 0.028 | ||

| Past Month | 46.1 (31.2) | 8.2 (11.6) | 10.1 (16.7) | |||

| Change from baseline (mean, 95% CL) | −36.3 (−52.9, −19.8) | −29.6, (−54.3, −4.8) | ||||

|

| ||||||

| Morisky Scale Mean (SD) | 2.5 (1.3) | 2.5 (1.2) | 1.4 (1.3) | 1.4 (1.6) | 30 | 0.001 |

|

| ||||||

| Injection Frequency | N/A | N/A | 83 (35) | 76 (35) | 29 | |

|

| ||||||

| DAI Mean (SD) | 7.4 (2.0) | 7.0 (2.0) | 8.2 (2.0) | 8.1 (1.3) | 30 | 0.006 |

|

| ||||||

| AMQ Mean (SD) | 7.2 (3.5) | N/A | N/A | 4.5 (3.3) | 19 | 0.019 |

|

| ||||||

| BPRS Mean (SD) | 46.1 (10.0) | 47.1 (11.5) | 34.0 (9.0) | 32.8 (10.0) | 30 | < 0.001 |

|

| ||||||

| PANSS Mean (SD) | N/A | 78.2 (26.6) | N/A | 51.8 (16.7) | 13 | 0.005 |

|

| ||||||

| CGI Mean (SD) | 4.9 (0.8) | 4.6 (0.9) | 3.5 (0.8) | 3.3 (0.8) | 18 | < 0.001 |

|

| ||||||

| SOFAS Mean (SD) | 48.3 (7.9) | 47.9 (8.0) | N/A | 59.3 (9.8) | 19 | < 0.001 |

|

| ||||||

| -Psychiatric Hospitalizations | N/A | 1.0 (3.0) | N/A | 0.1 (0.3) | 17 | 0.13 |

| -Medical Hospitalizations | 0.1 (0.3) | 0.3 (0.7) | 17 | 0.66 | ||

|

| ||||||

| Rates of sub-optimal housing status | ||||||

All values reported as Mean (SD)

Mean TRQ for oral medications prescribed in addition to LAI

TRQ: Tablet Routines Questionnaire

DAI : Drug Attitudes Inventory

AMQ : Attitudes to Medication Questionnaire

BPRS: Brief Psychiatric Rating Scale

PANSS: Positive and Negative Syndrome Scale

CGI: Clinical Global Impression

SOFAS: Social and Occupational Functioning Assessment Scale;

Over the course of the study participants had improvement in housing status. Mean proportion of time in sub-optimal housing went from 56% in the 6 months prior to study enrollment, 41 % in the first 3 months of the study and 14% in the last 3 months of the study (p= .001).

While the overall numbers of individuals with schizoaffective disorder was too small to conduct any comparative analysis we did note that that 13 of the 20 individuals with schizoaffective disorder completed the study and that overall change from baseline in TRQ, DAI and BPRS among individuals with schizoaffective disorder all suggested change in the same direction as was seen in the larger sample. The TRQ and DAI scores, available only for a partial group of the patients with schizoaffective disorder, showed numerical but not statistically significant change. For BPRS statistically significant change from baseline was observed (mean baseline BPRS = 44.7 (SD 10.4), mean endpoint BPRS = 34.1 (SD 9.9), t=2.51, df=11, p =0.029).

Tolerability and adverse effects

Table 4 illustrates side effects experienced by > 5% of study participants. Side effects were generally mild to moderate in intensity and transient, except for akathisia, which persisted for some individuals in spite of adjunct therapies. One individual discontinued LAI due to severe akathisia. Another individual had an increase in QTC interval on EKG from 443 milliseconds at baseline to 462 milliseconds on oral haloperidol, and this individual was not started on LAI. QTC interval decreased to less than 450 milliseconds when oral haloperidol was discontinued.

Table 4.

Adverse Events Occurring in > 5% of Homeless or Recently Homeless Individuals with Schizophrenia or Schizoaffective Disorder treated with LAI.

| Adverse Event | N | Percent |

|---|---|---|

| Akathisia | 12/30 | 40 |

| Dry mouth | 10/30 | 33 |

| Muscle twitching | 10/30 | 33 |

| GI complaints | 7/30 | 23 |

| Sedation | 6/30 | 20 |

| Blurry vision | 4/30 | 13 |

| Sexual dysfunction | 3/30 | 10 |

| Change in appetite | 3/30 | 10 |

| Injection site reaction | 3/30 | 10 |

| Change in urination | 3/30 | 10 |

| Headache | 2/30 | 7 |

With respect to standardized involuntary movement and neurological rating scales, there were no significant changes in AIMS and SAS, but change in BARS was significant, reflecting the emergence of akathisia. BMI and total cholesterol did not change significantly. There was statistically significant worsening in serum triglycerides, but since participants were not fasting prior to blood draws, clinical significance of non-fasting triglyceride changes is questionable. 27

There were 5 Serious Adverse Events (SAEs) during the study: 1 emergency room visit for non-study related medical reasons, 1 hospitalization for non-study related medical reasons, 1 hospitalization due to seizure and allergic reaction to anticonvulsant medication, and 2 hospitalizations due to suicide attempts. The seizure occurred in an individual with epilepsy, who was non-adherent with prescribed anticonvulsant medication. It is possible that the LAI contributed to the SAE by lowering seizure threshold. Both individuals with suicide attempts were continued on LAI after the attempt, and appeared to have a good response to continued exposure to CAE-L. External DSMB review of the 2 suicide attempts concluded that they did not appear related to study involvement.

In general, participants expressed satisfaction with CAE-L. The majority strongly agreed (N= 11, 61.1%) or agreed (N=7, 38.9%) that CAE was useful, and either strongly agreed (N= 6, 33.3 %) or agreed (N=10, 55.6%) that benefit exceeded the burden or hassle of participation. No individuals discontinued the psychosocial component of the study due to adverse effects.

Post-treatment follow-up

Of the 20 individuals who completed 25 weeks of CAE-L, 12 provided information at 3 months post-study and 8 individuals provided information at 6 months post-study. As noted in Figure 1, only 4 individuals continued to take LAI at 6-months post-study. While CGI scores between those who remained on LAI after 25 weeks did not appear markedly different from those not on LAI, small sample size did not permit valid statistical comparison.

Discussion

This prospective, uncontrolled study in homeless or recently homeless seriously mentally ill found that use of a novel psychosocial intervention plus LAI was associated with improvements in adherence and psychiatric symptoms. While there are substantial limitations to the study methods including small sample size, lack of a control group and relatively short duration, findings are still of substantial clinical relevance, given the tremendous personal and societal burden related to homelessness among people with schizophrenia 28-30. Approximately one in ten homeless individuals has schizophrenia, 6 and there are few established treatments for this vulnerable group. 28 The prognosis for these individuals is typically poor, with mortality rates four times that of the general population, 31 and double that of non-homeless individuals with schizophrenia. 32, 33 Consistent with the multiple challenges faced by homeless individuals with schizophrenia, 34, 35 the sample enrolled in this study were individuals with few social supports, limited education, frequent comorbid substance use, and a history of multiple involvements in the criminal justice system.

Similar to other reports ,36 individuals in this study reported missing 46–57% of prescribed medication. Use of CAE-L was associated with good adherence to maintenance LAI (76% at 6-months) and dramatic improvement in oral prescribed drug adherence, which changed from missing approximately 46% of prescribed medication to missing only 10% of prescribed medication by the end of the study. This could be particularly important for individuals with schizoaffective disorder who are often on multiple psychotropic agents.37 It is not entirely clear what factors facilitated the improved oral adherence, but it is possible that LAI and CAE had synergistic effects on improving insight and acceptance of medications more broadly.

Improvements in psychiatric symptoms have been noted as an independent effect of CAE, 9,10 and pairing CAE with LAI may have facilitated further reduction in symptoms and possibly improved insight into need for treatment. Housing improvement is a complicated issue that could have been affected by a variety of factors and may not have been related to CAE or LAI. However, it is also possible that individuals being less symptomatic and better able to manage their own personal affairs, such as meeting with social workers could have helped individuals to obtain appropriate housing.

Both the original version of CAE,9,10 developed for people with bipolar disorder, and the version used in this study, consist of detailed manuals that stress pragmatic problem-solving specifically focused on adherence relevant to the individual. Other features included delivering information in small chunks and use of modest incentives (i.e. washcloths, pencils, pill minders) for active participation.

A recent review suggested that LAIs reduce risk of relapse when combined with psychosocial interventions.38 Use of LAIs reduces the chance that individuals will miss prescribed medication doses due to forgetting or not wanting to take them in situations that can be stigmatizing (such as at work or school). When individuals miss an injection, visit staff can follow-up, and both assess clinical status and re-schedule the injection. LAIs can minimize antipsychotic withdrawal symptoms resulting from partial adherence. 39 In addition, LAIs are not influenced by first-pass metabolism, decreasing the potential for drug-drug interactions, and the slow rate of absorption of LAIs may reduce the differences between peak and trough plasma levels, 40 resulting in fewer side effects (an important predictor of adherence) relative to oral antipsychotics. 41, 42 A number of antipsychotic medications are currently available in LAI form, including typical and atypical drugs.38 Newer LAI antipsychotic formulations have relatively low extra-pyramidal side effect profiles .38 In our study, in spite of modest haloperidol dosages, akathisia was relatively common and at times not well-controlled even with supplemental treatments.

A limitation to study generalizability was the fact that the majority of individuals did not remain on LAI post-study. Perhaps using an atypical antipsychotic with a lower propensity for akathisia could have improved long-term LAI adherence. Additionally, logistic barriers to coordination between CMHC and study staff in transitioning stable individuals to maintenance care, and lack of the CAE/psychosocial component in routine clinical settings could have caused individuals to drop out of care. While CAE-L appears to engage and stabilize this very high-risk group, it may be that long-term or “booster” sessions are needed to maintain these gains.

Given methods limitations it is not possible to conclude that combining CAE with LAI has additive or synergistic effect. With the relatively severe symptoms and difficulties in concentration and attention experienced by many individuals in the study, it seems unlikely that CAE alone would have been enough to change health outcomes. One could argue that improvement was due to LAI. However, since some of the individuals had been on LAI in the past and were non-adherent, it might be reasonable to expect that a needs-based psychosocial intervention could enhance gains due to somatic therapy. Given that there are few established effective approaches to help homeless individuals with schizophrenia, there is a clear need for research that tests effective and practical approaches to improving health outcomes for these vulnerable individuals. In spite of the noted limitations of our study, findings have substantial implications for clinical practice. If findings can be replicated under controlled conditions this could represent a potential new best practice for the treatment of homeless, non-adherent individuals with schizophrenia and schizoaffective disorder.

Clinical Points.

Combining a long-acting injectable antipsychotic medication with a psychosocial intervention that targets individual reasons for medication non-adherence may improve outcomes for homeless individuals with schizophrenia and schizoaffective disorder.

Haloperidol decanoate can be helpful in reducing symptoms and improving functioning for homeless individuals with schizophrenia, although akathisia may be a common troubling side-effect.

Acknowledgments

This study was supported by a grant from the Reuter Foundation to the first author. Support for this project was also provided by the Clinical and Translational Science Collaborative (Dahms Clinical Research Unit) NIH grant number UL1 RR024989.

Dr Ramirez has served as speaker for Bristol Myers Squibb, Merck and Novartis. Dr Sajatovic has received grant support from AstraZeneca, Pfizer, Merck, Ortho-McNeil Janssen, royalties from Springer Press, Johns Hopkins University Press and Oxford Press, and served as consultant for Cognition Group, ProPhase and United BioSource Corporation (Bracket).

The authors wish to acknowledge Ms. Elisabeth Welter MS, MA for her assistance with preparation of the manuscript.

Footnotes

Drs Levin, Hahn, Tatsuoka, Mr Bialko, Ms Cassidy, MsWilliams and Ms Fuentes-Casiano report no conflict of interest.

Ms. Welter is affiliated with the Department of Neurology, Case Western Reserve University School of Medicine and University Hospitals Case Medical Center

Ms. Welter reports no conflict of interest.

Portions of this data have been presented at the 13th Annual Congress on Schizophrenia Research; Colorado Springs, CO. April 3, 2011 and will also be presented at the 14th Annual Congress on Schizophrenia Research: Orlando, Florida, April 25, 2013.

ClinicalTrials.gov: http://www.clinicaltrials.gov/ NCT01152697

Contributor Information

Martha Sajatovic, Email: Martha.sajatovic@uhhospitals.org, Department of Psychiatry, and Neurological Outcomes Center, Case Western Reserve University School of Medicine, University Hospitals Case Medical Center, 11100 Euclid Avenue, Cleveland, OH 44106, 216-844-2808

Jennifer Levin, Department of Psychiatry, Case Western Reserve University School of Medicine and University Hospitals Case Medical Center

Luis F. Ramirez, Department of Psychiatry, Case Western Reserve University School of Medicine, University Hospitals Case Medical Center

David Y. Hahn, Department of Psychiatry, Case Western Reserve University School of Medicine, University Hospitals Case Medical Center

Curtis Tatsuoka, Department of Neurology, Case Western Reserve University School of Medicine, University Hospitals Case Medical Center

Christopher S. Bialko, Department of Psychiatry, Case Western Reserve University School of Medicine, University Hospitals Case Medical Center

Kristin A. Cassidy, Department of Psychiatry, Case Western Reserve University School of Medicine, University Hospitals Case Medical Center

Edna Fuentes-Casiano, Department of Psychiatry, Case Western Reserve University School of Medicine, University Hospitals Case Medical Center

Tiffany D. Williams, Department of Psychiatry, Case Western Reserve University School of Medicine, University Hospitals Case Medical Center

References

- 1.Gilmer TP, Dolder CR, Lacro JP, et al. Adherence to treatment with antipsychotic medication and health care costs among Medicaid beneficiaries with schizophrenia. The American journal of psychiatry. 2004;161(4):692–699. doi: 10.1176/appi.ajp.161.4.692. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Valenstein M, Ganoczy D, McCarthy JF, et al. Antipsychotic adherence over time among patients receiving treatment for schizophrenia: a retrospective review. The Journal of clinical psychiatry. 2006;67(10):1542–1550. doi: 10.4088/jcp.v67n1008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Velligan DI, Wang M, Diamond P, et al. Relationships among subjective and objective measures of adherence to oral antipsychotic medications. Psychiatric services (Washington, D.C. ) 2007;58(9):1187–1192. doi: 10.1176/ps.2007.58.9.1187. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Zygmunt A, Olfson M, Boyer CA, et al. Interventions to improve medication adherence in schizophrenia. The American journal of psychiatry. 2002;159(10):1653–1664. doi: 10.1176/appi.ajp.159.10.1653. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Fenton WS, Blyler CR, Heinssen RK. Determinants of medication compliance in schizophrenia: empirical and clinical findings. Schizophrenia bulletin. 1997;23(4):637–651. doi: 10.1093/schbul/23.4.637. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Folsom D, Jeste DV. Schizophrenia in homeless persons: a systematic review of the literature. Acta psychiatrica Scandinavica. 2002;105:404–413. doi: 10.1034/j.1600-0447.2002.02209.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Sajatovic M, Levin J, Fuentes-Casiano E, et al. Illness experience and reasons for nonadherence among individuals with bipolar disorder who are poorly adherent with medication. Comprehensive psychiatry. 2011;52(3):280–287. doi: 10.1016/j.comppsych.2010.07.002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.West JC, Marcus SC, Wilk J, et al. Use of depot antipsychotic medications for medication nonadherence in schizophrenia. Schizophrenia bulletin. 2008;34(5):995–1001. doi: 10.1093/schbul/sbm137. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Sajatovic M, Levin J, Tatsuoka C, et al. Customized adherence enhancement for individuals with bipolar disorder receiving antipsychotic therapy. Psychiatric services (Washington, D.C. ) 2012;63(2):176–178. doi: 10.1176/appi.ps.201100133. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Sajatovic M, Levin J, Tatsuoka C, et al. Six-month outcomes of customized adherence enhancement (CAE) therapy in bipolar disorder. Bipolar disorders. 2012;14(3):291–300. doi: 10.1111/j.1399-5618.2012.01010.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Scott J, Pope M. Nonadherence with mood stabilizers: prevalence and predictors. The Journal of clinical psychiatry. 2002;63(5):384–390. doi: 10.4088/jcp.v63n0502. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Peet M, Harvey NS. Lithium maintenance: 1. A standard education programme for patients. The British journal of psychiatry : the journal of mental science. 1991;158:197–200. doi: 10.1192/bjp.158.2.197. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Sheehan DV, Lecrubier Y, Sheehan KH, et al. The Mini-International Neuropsychiatric Interview (M.I.N.I.): the development and validation of a structured diagnostic psychiatric interview for DSM-IV and ICD-10. The Journal of clinical psychiatry. 1998;59 (Suppl 20):22–33. quiz 34–57. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Development DoHaU, editor. Homeless Emergency Assistance and Rapid Transition to Housing. 2011. [Google Scholar]

- 15.TEVA Parenteral Medicines I. Irvine, CA: 2009. [Google Scholar]

- 16.Morisky DE, Green LW, Levine DM. Concurrent and predictive validity of a self-reported measure of medication adherence. Medical care. 1986;24(1):67–74. doi: 10.1097/00005650-198601000-00007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Harvey NS. The development and descriptive use of the Lithium Attitudes Questionnaire. Journal of affective disorders. 1991;22(4):211–219. doi: 10.1016/0165-0327(91)90067-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Awad AG. Subjective response to neuroleptics in schizophrenia. Schizophrenia bulletin. 1993;19(3):609–618. doi: 10.1093/schbul/19.3.609. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Overall JA, Gorham DR. The Brief Psychiatric Rating Scale. Psychological reports. 1962;10:799–812. [Google Scholar]

- 20.Kay SR, Fiszbein A, Opler LA. The positive and negative syndrome scale (PANSS) for schizophrenia. Schizophrenia bulletin. 1987;13(2):261–276. doi: 10.1093/schbul/13.2.261. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Guy W. Clinical Global Impressions. ECDEU Assessment Manual for psychoparmacology. Rockville, MD: US Department of Health, Education, and Welfare (DHEW); 1976. [Google Scholar]

- 22.McLellan AT, Luborsky L, Woody GE, et al. An improved diagnostic evaluation instrument for substance abuse patients. The Addiction Severity Index. The Journal of nervous and mental disease. 1980;168(1):26–33. doi: 10.1097/00005053-198001000-00006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.McLellan AT, Luborsky L, Cacciola J, et al. New data from the Addiction Severity Index. Reliability and validity in three centers. The Journal of nervous and mental disease. 1985;173(7):412–423. doi: 10.1097/00005053-198507000-00005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Morosini PL, Magliano L, Brambilla L, et al. Development, reliability and acceptability of a new version of the DSM-IV Social and Occupational Functioning Assessment Scale (SOFAS) to assess routine social functioning. Acta psychiatrica Scandinavica. 2000;101(4):323–329. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Simpson GM, Angus JW. A rating scale for extrapyramidal side effects. Acta psychiatrica Scandinavica. Supplementum. 1970;212:11–19. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-0447.1970.tb02066.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Barnes TR. A rating scale for drug-induced akathisia. The British journal of psychiatry : the journal of mental science. 1989;154:672–676. doi: 10.1192/bjp.154.5.672. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Ridker PM. Fasting versus nonfasting triglycerides and the prediction of cardiovascular risk: do we need to revisit the oral triglyceride tolerance test? Clinical chemistry. 2008;54(1):11–13. doi: 10.1373/clinchem.2007.097907. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Foster A, Gable J, Buckley J. Homelessness in schizophrenia. The Psychiatric clinics of North America. 2012;35(3):717–734. doi: 10.1016/j.psc.2012.06.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Dixon L, Weiden P, Torres M, et al. Assertive community treatment and medication compliance in the homeless mentally ill. The American journal of psychiatry. 1997;154(9):1302–1304. doi: 10.1176/ajp.154.9.1302. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Folsom DP, Hawthorne W, Lindamer L, et al. Prevalence and risk factors for homelessness and utilization of mental health services among 10,340 patients with serious mental illness in a large public mental health system. The American journal of psychiatry. 2005;162(2):370–376. doi: 10.1176/appi.ajp.162.2.370. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Babidge NC, Buhrich N, Butler T. Mortality among homeless people with schizophrenia in Sydney, Australia: a 10-year follow-up. Acta psychiatrica Scandinavica. 2001;103(2):105–110. doi: 10.1034/j.1600-0447.2001.00192.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Mortensen PB, Juel K. Mortality and causes of death in schizophrenic patients in Denmark. Acta psychiatrica Scandinavica. 1990;81(4):372–377. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-0447.1990.tb05466.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Tsuang MT, Woolson RF, Fleming JA. Premature deaths in schizophrenia and affective disorders. An analysis of survival curves and variables affecting the shortened survival. Archives of general psychiatry. 1980;37(9):979–983. doi: 10.1001/archpsyc.1980.01780220017001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Breakey WR, Fischer PJ, Kramer M, et al. Health and mental health problems of homeless men and women in Baltimore. JAMA : the journal of the American Medical Association. 1989;262(10):1352–1357. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Gelberg L, Linn LS, Mayer-Oakes SA. Differences in health status between older and younger homeless adults. Journal of the American Geriatrics Society. 1990;38(11):1220–1229. doi: 10.1111/j.1532-5415.1990.tb01503.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Osterberg L, Blaschke T. Adherence to medication. The New England journal of medicine. 2005;353(5):487–497. doi: 10.1056/NEJMra050100. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Olfson M, Marcus SC, Wan GJ. Treatment patterns for schizoaffective disorder and schizophrenia among Medicaid patients. Psychiatric services (Washington, D.C. ) 2009;60(2):210–216. doi: 10.1176/ps.2009.60.2.210. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Zhornitsky S, Stip E. Oral versus Long-Acting Injectable Antipsychotics in the Treatment of Schizophrenia and Special Populations at Risk for Treatment Nonadherence: A Systematic Review. Schizophrenia Research and Treatment. 2012;2012 doi: 10.1155/2012/407171. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Hughes DA. Estimation of the impact of noncompliance on pharmacokinetics: an analysis of the influence of dosing regimens. British journal of clinical pharmacology. 2008;65(6):871–878. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2125.2008.03124.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Ereshefsky L, Mascarenas CA. Comparison of the effects of different routes of antipsychotic administration on pharmacokinetics and pharmacodynamics. The Journal of clinical psychiatry. 2003;64 (Suppl 16):18–23. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Fleischhacker WW, Meise U, Gunther V, et al. Compliance with antipsychotic drug treatment: influence of side effects. Acta psychiatrica Scandinavica. Supplementum. 1994;382:11–15. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Canas F, Moller HJ. Long-acting atypical injectable antipsychotics in the treatment of schizophrenia: safety and tolerability review. Expert opinion on drug safety. 2010 Sep;9(5):683–697. doi: 10.1517/14740338.2010.506712. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]