Abstract

Objective. This study aimed to evaluate the association between serum uric acid (SUA) levels within a normal to high range and the risk of metabolic syndrome (MetS) among community elderly and explore the sex difference. Design and Methods. A cross-sectional study was conducted in a representative urban area of Beijing between 2009 and 2010. A two-stage stratified clustering sampling method was used and 2102 elderly participants were included. Results. The prevalence of hyperuricemia and MetS was 16.7% and 59.1%, respectively. There was a strong association between hyperuricemia and four components of MetS in women and three components in men. Multiple logistic regression analysis showed ORs of hyperuricemia for MetS were 1.67 (95% CI: 1.11–2.50) in men and 2.73 (95% CI: 1.81–4.11) in women. Even in the normal range, the ORs for MetS increased gradually according to SUA levels. MetS component number also showed an increasing trend across SUA quartile in both sexes (P for trend < 0.01). Conclusion. This study suggests that higher SUA levels, even in the normal range, are positively associated with MetS among Chinese community elderly, and the association is stronger in women than men. Physicians should recognize MetS as a frequent comorbidity of hyperuricemia and take early action to prevent subsequent disease burden.

1. Introduction

Metabolic syndrome (MetS) is a complex of interrelated risk factors including obesity (particularly central adiposity), hyperglycemia, elevated blood pressure, hypertriglyceridemia, and decreased high density-lipoprotein cholesterol (HDL-C) [1]. Current available evidence suggests that MetS is associated with the development of diabetes, cardiovascular disease (CVD), and kidney diseases and is also of increased risk for mortality of CVD and all causes [2–6]. Also, population-based studies have shown that MetS is quite common, affecting about 13.7% of the middle-aged [7] and 50% of the elderly [8] in China. And its prevalence is increasing with dramatic socioeconomic change and a succession of increased unhealthy lifestyles [7].

Serum uric acid (SUA) is the end product of urine metabolism in human, and excess accumulation can lead to various diseases [9]. The relationship between SUA levels and cardiovascular conditions has been studied by a number of researches since 1960s [10–13]. However, the conclusion remains controversial, and SUA levels within a normal to high range have not been fully studied in association with MetS. In addition, most studies are primarily about adults and institutionalized people. There are limited studies focused on elderly population, which have higher prevalence of hyperuricemia and MetS and are of higher risk to develop CVD events. Data are needed to confirm the association of SUA levels with MetS and its individual components in community elderly population.

Moreover, a rapidly increasing trend of MetS prevalence has been reported in the Chinese elderly in the past decade, with an absolute change of 7.7% [14]. Therefore, it is important and urgent to identify the participants who have high risk of MetS and then to prevent subsequent related disease burden. Our study aims to examine the association of SUA levels and risk of MetS in an urban community elderly population of Beijing, China.

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Methods

This was a population-based cross-sectional survey conducted in Wanshoulu Community of Haidian district, a metropolitan area representative of the geographic and economic characteristics in Beijing, China. The eligible subjects were individuals aged ≥60 years who had lived in the local district for at least one year. Sampling and research methods were reported elsewhere [14]. In brief, a two-stage stratified clustering sampling method was used. First, 5 residential communities were selected randomly from the total 36 residential communities. Second, all eligible households were chosen from the selected 5 communities. Between September 2009 and June 2010, a total of 2162 residents aged 60–95 years were selected and invited for screening. 2102 residents (848 men, 1,254 women) completed the survey. These participants accounted for about 10% of total elderly residents in the Wanshoulu community.

Each participant was interviewed and completed a standardized questionnaire including demographic factors, medical history, family history of CVD, and lifestyles. The height, weight, waist, and blood pressure were measured according to standardized protocol. Physical examinations and face-to-face interviews were carried out by specially trained nurses and physicians. Height was measured in meters (without shoes), and weight was measured in kilograms (with heavy clothing removed and 1 kg deducted for remaining garments). Body mass index (BMI) was calculated as weight in kilograms divided by the square of height in meters. Waist circumference on standing participants was measured midway between the lower rib margin and iliac crest. Two blood pressure recordings were obtained from the right arm of participants in a sitting position after 30 minutes of rest. If the difference between the first and second measurement was more than 5 mmHg, then repeated measurements were performed. The average of last two measurements was used. Overnight fasting blood specimens were obtained for tests of serum lipids, glucose, and SUA level. Samples were sent to the Central Certified Laboratory of Chinese PLA General Hospital in less than 30 minutes.

2.2. Definition of Hyperuricemia

Participants were diagnosed with hyperuricemia if their SUA level was ≥7.0 mg/dL (417 mmol/L) in men or ≥6.0 mg/dL (357 mmol/L) in women. SUA levels of participants without hyperuricemia were categorized into 4 levels using the quartiles (P25, P50, and P75) as cut-off values. In this study, sex-specific SUA quartiles for participants without hyperuricemia were as follows: Q1: ≤4.71 mg/dL (n = 176), Q2: 4.72–5.43 mg/dL (n = 176), Q3: 5.44–6.48 mg/dL (n = 175), Q4: ≥6.49 mg/dL (n = 173) in men; Q1: ≤3.90 mg/dL (n = 267), Q2: 3.91 mg/dL–4.54 mg/dL (n = 263), Q3: 4.55 mg/dL–5.10 mg/dL (n = 260), Q4: ≥5.11 mg/dL (n = 260) in women. All the four groups were under normal range of SUA level.

2.3. Definition of MetS

MetS was defined according to the 2009 harmonizing definition set by a joint statement of the International Diabetes Federation Task Force on Epidemiology and Prevention; National Heart, Lung, and Blood Institute; American Heart Association; Word Heart Federation; International Atherosclerosis Society; and International Association for the Study of Obesity, as the presence of three or more of the following five criteria: (1) central obesity: waist circumference (WC) ≥ 90 cm in Asian men and ≥80 cm in Asian women; (2) hypertriglyceridemia: fasting plasma triglycerides (TG) ≥1.7 mmol/L; drug treatment for elevated triglycerides is an alternate indicator; (3) decreased HDL-C: fasting HDL-C <1.0 mmol/L in men and <1.3 mmol/L in women; drug treatment for reduced HDL-C is an alternate indicator; (4) elevated blood pressure: systolic blood pressure (SBP) ≥ 130 mmHg and/or diastolic blood pressure (DBP) ≥ 85 mmHg; antihypertensive drug treatment in a patient with a history of hypertension is an alternate indicator; (5) hyperglycemia: fasting glucose level of ≥5.6 mmol/L (≥100 mg/dL); drug treatment of elevated glucose is an alternate indicator [1]. This harmonizing definition is the same with the modified NECP ATP III definition [15].

2.4. Statistical Analysis

Data were double entered using Epidata 3.1. All analyses were conducted using SPSS for windows (19.0, no. of serial: 5076595). Reported probabilities were two-sided; all tests were set at the 0.05 level of statistical significance.

Descriptive data were expressed as for continuous variables and n(%) for categorical variables unless otherwise specified. t-test and Chi-square test were used to examine differences in continuous and categorical variables. The relationship between SUA levels and other variables was assessed using the partial correlation coefficients. The trend test was used to determine MetS prevalence and its component number according to SUA quartiles. Finally, multivariable logistic regression was used to estimate the association between sex-specific SUA level and MetS prevalence. We calculated the odds ratio (OR) and 95% confidence intervals (CIs) of SUA for MetS and its five components.

2.5. Ethical Considerations

Ethical approval was obtained from the Ethics Committees of Chinese PLA General Hospital (EC0411-2001). All eligible participants had given their written informed consent.

3. Results

A total of 2,102 participants completed the survey, with 848 (40.3%) men and 1254 (59.7%) women. The mean age was 71.2 ± 6.6 (60~95 yrs); the older elderly (aged ≥ 80 yrs) accounted for 9.2%. The baseline characteristics of participants according to sex and hyperuricemia are presented in Table 1.

Table 1.

Characteristics of the participants with hyperuricemia and those without.

| Characteristics | Men (n = 848) | Women (n = 1254) |

Total (n = 2102) |

||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Hyperuricemia (n = 148) | No hyperuricemia (n = 700) | P value | Subtotal | Hyperuricemia (n = 204) | No hyperuricemia (n = 1050) | P value | Subtotal | ||

| Age (yrs) | 73.5 ± 6.9 | 72.1 ± 6.8 | 0.028 | 72.3 ± 6.9 | 71.8 ± 6.0 | 70.1 ± 6.3 | 0.001 | 70.4 ± 6.2 | 71.2 ± 6.6 |

| WC (cm) | 94.0 ± 8.4 | 90.6 ± 8.4 | <0.001 | 91.2 ± 8.5 | 90.3 ± 9.5 | 85.6 ± 8.6 | <0.001 | 86.4 ± 8.9 | 88.3 ± 9.1 |

| BMI (kg/m2) | 25.7 ± 3.0 | 24.8 ± 3.1 | 0.002 | 24.9 ± 3.1 | 26.4 ± 3.8 | 24.8 ± 3.5 | <0.001 | 25.0 ± 3.6 | 25.0 ± 3.4 |

| SBP (mmHg) | 136.8 ± 17.5 | 136.6 ± 18.0 | 0.927 | 136.7 ± 17.9 | 141.9 ± 20.4 | 140.2 ± 20.9 | 0.285 | 140.5 ± 20.8 | 139.0 ± 19.8 |

| DBP (mmHg) | 77.4 ± 9.4 | 78.6 ± 9.7 | 0.191 | 78.4 ± 9.7 | 75.9 ± 10.4 | 76.8 ± 9.9 | 0.273 | 76.6 ± 10.0 | 77.3 ± 9.9 |

| TC (mmol/L)a | 5.0 ± 1.1 | 4.9 ± 0.9 | 0.131 | 4.9 ± 0.9 | 5.5 ± 1.0 | 5.5 ± 1.0 | 0.550 | 5.5 ± 1.0 | 5.3 ± 1.0 |

| TG (mmol/L) | 1.8 ± 1.0 | 1.5 ± 0.8 | 0.001 | 1.5 ± 0.9 | 2.1 ± 1.0 | 1.7 ± 0.9 | <0.001 | 1.8 ± 0.9 | 1.7 ± 0.9 |

| HDL-C (mmol/L) | 1.2 ± 0.3 | 1.3 ± 0.4 | 0.016 | 1.3 ± 0.4 | 1.4 ± 0.4 | 1.5 ± 0.4 | <0.001 | 1.5 ± 0.4 | 1.4 ± 0.4 |

| LDL-C (mmol/L)b | 3.1 ± 0.9 | 3.0 ± 0.8 | 0.338 | 3.1 ± 0.8 | 3.4 ± 0.8 | 3.4 ± 0.9 | 0.506 | 3.4 ± 0.9 | 3.3 ± 0.8 |

| FBG (mmol/L) | 6.0 ± 1.3 | 6.1 ± 1.6 | 0.428 | 6.1 ± 1.5 | 6.1 ± 1.3 | 6.1 ± 1.8 | 0.704 | 6.1 ± 1.8 | 6.1 ± 1.7 |

| 2hPG (mmol/L) | 8.1 ± 2.6 | 8.2 ± 3.0 | 0.707 | 8.2 ± 3.0 | 9.2 ± 3.3 | 8.2 ± 3.3 | <0.001 | 8.4 ± 3.3 | 8.3 ± 3.2 |

| SUA (mg/dL) | 7.9 ± 0.8 | 5.4 ± 0.9 | <0.001 | 5.8 ± 1.3 | 7.0 ± 1.0 | 4.5 ± 0.8 | <0.001 | 4.9 ± 1.2 | 5.3 ± 1.4 |

| n (%) | |||||||||

| Education (≥6 yrs) | 124 (83.8) | 576 (82.3) | 0.663 | 700 (82.5) | 142 (69.6) | 680 (64.8) | 0.183 | 822 (65.6) | 1522 (72.4) |

| Married | 131 (88.5) | 650 (92.9) | 0.075 | 781 (92.1) | 157 (77.0) | 836 (79.6) | 0.392 | 993 (79.2) | 1774 (84.4) |

| Current smoking | 27 (18.2) | 153 (21.9) | 0.329 | 180 (21.2) | 7 (3.4) | 44 (4.2) | 0.615 | 51 (4.1) | 231 (11.1) |

| Current drinking | 58 (39.2) | 267 (38.1) | 0.812 | 325 (38.3) | 14 (6.9) | 86 (8.2) | 0.522 | 100 (8.0) | 425 (20.2) |

| PA (≥0.5 h/day) | 88 (59.5) | 422 (60.3) | 0.852 | 510 (60.1) | 121 (59.3) | 603 (57.4) | 0.618 | 724 (57.7) | 1234 (58.7) |

| Family history of CVD | 84 (56.8) | 453 (64.7) | 0.068 | 537 (63.3) | 122 (59.8) | 639 (60.9) | 0.778 | 761 (60.7) | 1298 (61.8) |

| Medication for hypertension | 76 (51.4) | 278 (39.7) | 0.009 | 354 (41.7) | 125 (61.3) | 493 (47.0) | <0.001 | 618 (49.3) | 972 (46.2) |

| Medication for diabetes | 23 (15.5) | 119 (17.0) | 0.666 | 142 (16.7) | 39 (19.1) | 180 (17.1) | 0.497 | 219 (17.5) | 361 (17.2) |

| Medication for hyperlipidemia | 31 (20.9) | 86 (12.3) | 0.006 | 117 (13.8) | 38 (18.6) | 147 (14.0) | 0.088 | 185 (14.8) | 302 (14.4) |

| MetS | 93 (62.8) | 332 (47.4) | 0.001 | 425 (50.1) | 168 (82.4) | 649 (61.8) | <0.001 | 817 (65.2) | 1242 (59.1) |

Data are for continuous values or n (%) for category values; aTC: total cholesterol; bLDL-C: low density-lipoprotein cholesterol.

The prevalence of MetS and hyperuricemia in this community's elderly was 59.1%, and 16.7%, respectively. The percentage of participants who had both MetS and hyperuricemia was 12.4%; men were lower than women but with no statistical difference (11.0% versus 13.4%, P = 0.097).

3.1. Clinical Features of Participants with and without Hyperuricemia

Table 1 shows the demographic characteristics and anthropometric measurements of the 2102 participants. The mean SUA level was 5.3 ± 1.4 mg/dL (range, 1.4–11.3 mg/dL). In men, participants with hyperuricemia had older age, greater WC, higher BMI, higher TG, and lower HDL-C levels. However, there were no significant differences in blood pressure and FPG. In women, besides these differences, we also observed higher levels of 2-hour postprandial blood glucose (2hPG) in participants with hyperuricemia than those without. The percentage of participants who were married, better educated, currently smoking and drinking did not differ with hyperuricemia.

3.2. Correlation of SUA Level and Clinical Characteristics of Study Participants

Table 2 shows the correlation coefficients between SUA level and other clinical characteristics of the participants. SUA level was positively correlated with age, WC, BMI, TG, and 2hPG and negatively correlated with HDL-C in both sexes. In men SUA was also positively correlated with LDL-C and negatively correlated with FPG. In women, SUA was positively correlated with 2hPG and not correlated with TC, LDL-C.

Table 2.

Correlation of SUA and clinical characteristics of the study participants.

| Characteristics | Men (n = 848) | Women (n = 1254) | Total (n = 2102) | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| r | P value | r | P value | r | P value | |

| Age (yrs) | 0.101 | 0.003 | 0.097 | 0.001 | 0.140 | <0.001 |

| WC (cm) | 0.204 | <0.001 | 0.239 | <0.001 | 0.290 | <0.001 |

| BMI (kg/m2) | 0.155 | <0.001 | 0.224 | <0.001 | 0.181 | <0.001 |

| SBP (mmHg) | 0.021 | 0.547 | 0.046 | 0.105 | 0.002 | 0.920 |

| DBP (mmHg) | −0.047 | 0.174 | 0.013 | 0.657 | 0.017 | 0.434 |

| TC (mmol/L) | 0.101 | 0.003 | 0.001 | 0.973 | 0.051 | 0.020 |

| TG (mmol/L) | 0.196 | <0.001 | 0.199 | <0.001 | 0.140 | <0.001 |

| HDL-C (mmol/L) | −0.152 | <0.001 | −0.185 | <0.001 | −0.227 | <0.001 |

| LDL-C (mmol/L) | 0.097 | <0.001 | 0.008 | 0.779 | 0.022 | 0.316 |

| FBG (mmol/L) | −0.099 | 0.004 | −0.004 | 0.884 | −0.039 | 0.077 |

| 2hPG (mmol/L) | −0.028 | 0.422 | 0.112 | <0.001 | 0.045 | 0.037 |

Adjusted for medication for hypertension, diabetes, and hyperlipidemia.

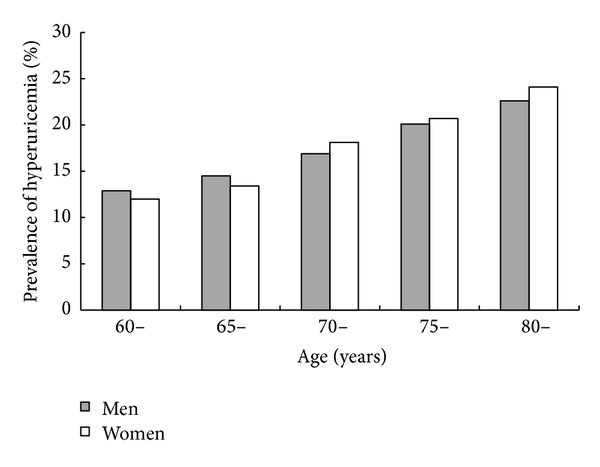

3.3. Age and Sex-Specific Prevalence of Hyperuricemia in the Participants

Figure 1 describes the prevalence of hyperuricemia by age and by sex. The prevalence showed an increasing trend with different age group (P for trend <0.001). Men had a higher prevalence in the younger elderly, but in the participants aged more than 70s, women had a higher prevalence.

Figure 1.

Age and sex-specific prevalence of hyperuricemia.

3.4. Prevalence of MetS and Its Individual Components for Different Serum Acid Levels

The prevalence of MetS was greater in participants with hyperuricemia than those without in both sexes. In men, three individual components (excluding elevated blood pressure and hyperglycemia), and, in women, four individual components (excluding elevated blood pressure) showed significant difference in participants with and without hyperuricemia (P < 0.05). The number of MetS components also showed the same trend (Table 3).

Table 3.

Prevalence of MetS and individual components according to hyperuricemia.

| Hyperuricemia | No hyperuricemia | P value | Total | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Men (n = 848) | ||||

| Individual components | ||||

| Central obesity | 112 (75.7) | 383 (54.7) | <0.001 | 495 (58.4) |

| Hypertriglyceridemia | 73 (49.3) | 244 (34.9) | 0.001 | 317 (37.4) |

| Low HDL-C | 51 (34.5) | 181 (25.9) | 0.033 | 232 (27.4) |

| Elevated blood pressure | 122 (82.4) | 545 (77.9) | 0.217 | 667 (78.7) |

| Hyperglycemia | 86 (58.1) | 378 (54.0) | 0.362 | 464 (54.7) |

| Number of MetS components | ||||

| One or more | 142 (95.9) | 654 (93.4) | 0.246 | 796 (93.9) |

| Two or more | 127 (85.8) | 516 (73.7) | 0.002 | 643 (75.8) |

| Three or more (MetS) | 93 (62.8) | 332 (47.4) | 0.001 | 425 (50.1) |

| Four or more | 56 (37.8) | 165 (23.6) | <0.001 | 221 (26.1) |

| Five | 26 (17.6) | 64 (9.1) | 0.003 | 90 (10.6) |

| Women (n = 1254) | ||||

| Individual components | ||||

| Central obesity | 176 (86.3) | 810 (77.1) | 0.004 | 986 (78.6) |

| Hypertriglyceridemia | 135 (66.2) | 478 (45.5) | <0.001 | 613 (48.9) |

| Low HDL-C | 117 (57.4) | 431 (41.0) | <0.001 | 548 (43.7) |

| Elevated blood pressure | 170 (83.3) | 854 (81.3) | 0.499 | 1024 (81.7) |

| Hyperglycemia | 128 (62.7) | 503 (47.9) | <0.001 | 631 (50.3) |

| Number of MetS components | ||||

| One or more | 203 (99.5) | 1000 (95.2) | 0.005 | 1203 (95.9) |

| Two or more | 191 (93.6) | 887 (84.5) | 0.001 | 1078 (86.0) |

| Three or more (MetS) | 168 (82.4) | 649 (61.8) | <0.001 | 817 (65.2) |

| Four or more | 117 (57.4) | 387 (36.9) | <0.001 | 504 (40.2) |

| Five | 47 (23.0) | 153 (14.6) | 0.003 | 200 (15.9) |

Table 4 showed the prevalence of MetS and its five components for those without hyperuricemia. The prevalence of MetS increased from 39.2% and 50.6% to 55.5% and 70.4%, respectively, in men and women (P for trend <0.05 in both sexes) for those with SUA level under normal range. The number of MetS components also increased gradually with increasing SUA quartiles. In men, three of the individual components (excluding elevated blood pressure and hyperglycemia) and, in women, all five components showed increasing trends according to SUA quartiles (P for trend <0.05).

Table 4.

Prevalence of MetS and individual components according to SUA quartiles for participants without hyperuricemia.

| Men (n = 700) | Women (n = 1050) | |||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Q1 | Q2 | Q3 | Q4 | P valuea | Q1 | Q2 | Q3 | Q4 | P valuea | |

| Individual components | ||||||||||

| Central obesity | 47.2 | 51.7 | 59.4 | 60.7 | 0.020 | 69.3 | 76.8 | 77.7 | 85.0 | <0.001 |

| Hypertriglyceridemia | 27.8 | 29.0 | 41.1 | 41.6 | 0.001 | 33.7 | 41.8 | 51.9 | 55.0 | <0.001 |

| Low HDL-C | 19.9 | 21.6 | 30.6 | 31.4 | 0.004 | 32.2 | 35.0 | 45.8 | 51.5 | <0.001 |

| Elevated blood pressure | 76.1 | 75.4 | 79.5 | 80.3 | 0.547 | 73.8 | 81.5 | 82.9 | 87.3 | <0.001 |

| Hyperglycemia | 52.3 | 48.9 | 58.3 | 56.6 | 0.181 | 41.2 | 46.3 | 49.2 | 52.1 | 0.007 |

| Number of MetS components | ||||||||||

| One or more | 91.5 | 92.6 | 94.8 | 94.9 | 0.089 | 90.3 | 95.8 | 96.9 | 98.1 | <0.001 |

| Two or more | 70.5 | 70.5 | 76.6 | 77.5 | 0.069 | 72.3 | 87.1 | 87.7 | 91.2 | <0.001 |

| Three or more (MetS) | 39.2 | 44.3 | 50.9 | 55.5 | 0.008 | 50.6 | 60.8 | 65.8 | 70.4 | <0.001 |

| Four or more | 14.8 | 17.6 | 30.6 | 31.4 | <0.001 | 27.7 | 33.5 | 39.6 | 46.9 | <0.001 |

| Five | 6.3 | 6.8 | 11.6 | 13.0 | 0.041 | 9.4 | 11.4 | 16.2 | 21.5 | <0.001 |

a P for trend.

3.5. ORs of SUA and MetS

Table 5 showed the ORs of SUA for MetS and its individual components. Three types of SUA level were used, including hyperuricemia as a dichotomous variable, SUA level as a continuous variable, and quartiles as an ordinal categorical variable. The table showed that, after adjusted age, education, marital status, current smoking, current drinking, physical activity, family history, medications for hypertension, diabetes, and hyperlipidemia, participants with hyperuricemia or higher SUA level were at significantly elevated ORs for MetS and most of its five individual components.

Table 5.

ORs and 95% CI of MetS and individual components according to SUA level.

| SUA level (continuous) | Hyperuricemia (dichotomous) | SUA level (quartiles for those under normal range) | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| OR (95% CI) | P value | OR (95% CI) | P value | Q1 | Q2 OR (95% CI) | Q3 OR (95% CI) | Q4 OR (95% CI) | P valuea | |

| Men | |||||||||

| MetS | 1.21 (1.08–1.36) | 0.001 | 1.67 (1.11–2.50) | 0.014 | 1.00 | 0.97 (0.66–1.43) | 1.32 (0.76–2.30) | 1.52 (1.03–2.23) | 0.007 |

| Number of MetS components | 1.24 (1.14–1.36) | <0.001 | 1.81 (1.30–2.51) | <0.001 | 1.00 | 0.87 (0.60–1.27) | 1.49 (1.02–2.18) | 1.66 (1.13–2.45) | <0.001 |

| Individual component | |||||||||

| Central obesity | 1.25 (1.12–1.39) | <0.001 | 2.34 (1.55–3.52) | <0.001 | 1.00 | 1.01 (0.69–1.48) | 1.50 (0.85–2.64) | 1.65 (1.12–2.43) | 0.027 |

| Hypertriglyceridemia | 1.27 (1.12–1.44) | <0.001 | 1.72 (1.13–2.64) | 0.012 | 1.00 | 1.53 (1.00–2.33) | 1.84 (1.27–2.90) | 1.92 (1.02–3.35) | 0.017 |

| Low HDL-C | 1.20 (1.03–1.39) | 0.019 | 1.17 (0.68–2.01) | 0.565 | 1.00 | 1.43 (0.91–2.27) | 1.57 (0.82–2.98) | 1.87 (1.19–2.93) | 0.045 |

| Elevated blood pressure | 1.01 (0.88–1.07) | 0.879 | 1.01 (0.60–1.72) | 0.970 | 1.00 | 0.94 (0.60–1.50) | 0.98 (0.62–1.57) | 1.00 (0.50–2.00) | 0.996 |

| Hyperglycemia | 1.10 (0.98–1.23) | 0.098 | 1.22 (0.83–178) | 0.321 | 1.00 | 0.95 (0.65–1.40) | 1.12 (0.81–1.74) | 0.90 (0.52–1.58) | 0.641 |

| Women | |||||||||

| MetS | 1.50 (1.32–1.69) | <0.001 | 2.73 (1.81–4.11) | <0.001 | 1.00 | 1.59 (1.15–2.19) | 1.85 (1.34–2.55) | 3.05 (1.86–5.02) | <0.001 |

| Number of MetS components | 1.39 (1.28–1.52) | <0.001 | 2.11 (1.59–2.80) | <0.001 | 1.00 | 1.98 (1.45–2.70) | 2.29 (1.14–3.63) | 2.87 (2.09–3.95) | <0.001 |

| Individual components | |||||||||

| Central obesity | 1.32 (1.16–1.50) | <0.001 | 1.83 (1.19–2.82) | 0.006 | 1.00 | 1.37 (0.95–1.97) | 1.96 (1.34–2.87) | 2.13 (1.20–3.75) | 0.002 |

| Hypertriglyceridemia | 1.35 (1.22–1.50) | <0.001 | 2.28 (1.62–3.20) | <0.001 | 1.00 | 1.41 (1.02–1.94) | 1.91 (1.39–2.63) | 2.43 (1.56–3.80) | <0.001 |

| Low HDL-C | 1.32 (1.19–1.47) | <0.001 | 1.90 (1.36–2.67) | <0.001 | 1.00 | 1.33 (0.96–1.85) | 1.89 (1.37–2.61) | 2.58 (1.65–4.04) | <0.001 |

| Elevated blood pressure | 1.15 (1.02–1.31) | 0.032 | 1.07 (0.71–1.61) | 0.740 | 1.00 | 1.56 (1.05–2.32) | 2.05 (1.11–3.78) | 2.11 (1.40–3.17) | 0.002 |

| Hyperglycemia | 1.23 (1.11–1.36) | <0.001 | 1.85 (1.32–2.59) | <0.001 | 1.00 | 1.50 (1.09–2.06) | 1.19 (0.87–1.63) | 1.78 (1.15–2.78) | 0.021 |

Adjusted for age, education, marital status, BMI, current smoking, current drinking, physical activity ≥ 0.5 h/day, family history of CVD, medications for hypertension, diabetes, and hyperlipidemia.

a P for trend.

There were sex differences of the ORs for MetS. Women had higher ORs of SUA level for MetS than men. The ORs for elevated blood pressure and hyperglycemia were not statistically significant in men using all three forms of SUA, but in women the ORs for the two components were significant using SUA levels as continuous variable and quartiles.

We also ascertained the association of SUA level and MetS in the sensitivity analysis and the results were similar (Tables 6 and 7). When participants with kidney disease (n = 105, 5.0%) were excluded, the adjusted ORs of hyperuricemia for MetS were 1.64 (95 CI: 1.09–2.47) in men and 2.68 (95 CI: 1.78–4.03) in women (Table 6). Also, in Table 7, when the participants aged under 65 years were excluded (n = 391, 18.6%), the adjusted ORs of hyperuricemia for MetS were 1.96 (95% CI: 1.26–3.06) in men and 2.55 (95% CI: 1.63–3.99) in women.

Table 6.

ORs and 95% CI of MetS and individual components excluding participants with kidney diseases.

| SUA level (continuous) | hyperuricemia (dichotomous) | SUA level (quartiles for those under normal range) | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| OR (95% CI) | P value | OR (95% CI) | P value | Q1 | Q2 OR (95% CI) | Q3 OR (95% CI) | Q4 OR (95% CI) | P valuea | |

| Male (n = 765) | |||||||||

| MetS | 1.21 (1.07–1.35) | 0.002 | 1.64 (1.09–2.47) | 0.018 | 1.00 | 1.45 (0.90–2.34) | 1.67 (1.05–2.75) | 2.30 (1.42–3.71) | 0.008 |

| Number of MetS components | 1.23 (1.12–1.37) | <0.001 | 1.79 (1.28–2.50) | <0.001 | 1.00 | 0.87 (0.59–1.15) | 1.47 (1.00–2.16) | 1.60 (1.08–2.36) | 0.033 |

| Individual component | |||||||||

| Central obesity | 1.23 (1.11–1.38) | <0.001 | 2.27 (1.50–3.43) | <0.001 | 1.00 | 0.79 (0.51–1.21) | 1.29 (0.83–2.00) | 1.33 (0.86–2.06) | 0.048 |

| Hypertriglyceridemia | 1.26 (1.11–1.43) | <0.001 | 1.68 (1.09–2.59) | 0.018 | 1.00 | 1.01 (0.58–1.76) | 1.65 (0.87–2.82) | 2.03 (1.20–3.43) | 0.014 |

| Low HDL-C | 1.20 (1.03–1.39) | 0.020 | 1.17 (0.68–2.01) | 0.564 | 1.00 | 1.18 (0.59–2.34) | 1.67 (0.86–3.22) | 2.23 (1.17–4.24) | 0.042 |

| Elevated blood pressure | 1.00 (0.87–1.16) | 0.996 | 1.01 (0.59–1.73) | 0.970 | 1.00 | 0.87 (0.49–1.55) | 0.93 (0.58–1.49) | 1.05 (0.78–1.92) | 0.823 |

| Hyperglycemia | 1.10 (0.98–1.23) | 0.104 | 1.22 (0.82–1.81) | 0.324 | 1.00 | 0.97 (0.58–1.52) | 1.45 (0.92–2.35) | 1.53 (0.96–2.45) | 0.084 |

| Female (n = 1232) | |||||||||

| MetS | 1.50 (1.32–1.69) | <0.001 | 2.68 (1.78–4.03) | <0.001 | 1.00 | 1.84 (1.24–2.72) | 2.12 (1.41–3.19) | 2.49 (1.65–3.76) | <0.001 |

| Number of MetS components | 1.39 (1.28–1.51) | <0.001 | 2.09 (1.58–279) | <0.001 | 1.00 | 2.01 (1.15–2.75) | 2.37 (1.78–3.25) | 2.89 (2.10–3.97) | <0.001 |

| Individual components | |||||||||

| Central obesity | 1.32 (1.16–1.50) | <0.001 | 1.83 (1.19–2.12) | 0.006 | 1.00 | 1.47 (0.99–2.19) | 1.65 (1.10–2.47) | 2.65 (158–3.80) | 0.001 |

| Hypertriglyceridemia | 1.35 (1.21–1.50) | <0.001 | 2.25 (1.60–3.17) | <0.001 | 1.00 | 1.81 (1.20–2.71) | 2.38 (1.58–3.58) | 2.47 (1.64–3.73) | <0.001 |

| Low HDL-C | 1.32 (1.18–1.46) | <0.001 | 1.88 (1.34–2.64) | <0.001 | 1.00 | 1.41 (0.93–2.15) | 1.94 (1.27–2.94) | 2.31 (1.52–3.50) | <0.001 |

| Elevated blood pressure | 1.18 (1.03–1.36) | 0.009 | 1.08 (0.72–1.61) | 0.132 | 1.00 | 1.62 (0.99–2.66) | 1.72 (1.05–2.82) | 2.25 (1.32–3.84) | 0.018 |

| Hyperglycemia | 1.22 (1.10–1.36) | <0.001 | 1.83 (1.30–2.57) | <0.001 | 1.00 | 1.54 (1.03–2.31) | 1.59 (1.07–2.38) | 1.97 (1.321–2.92) | 0.009 |

Adjusted for age, education, marital status, BMI, current smoking, current drinking, physical activity ≥ 0.5 h/day, family history of CVD, medications for hypertension, diabetes, and hyperlipidemia.

a P for trend.

Table 7.

ORs and 95% CI of MetS and individual components for participants aged more than 65 years.

| SUA level (continuous) | Hyperuricemia (dichotomous) | SUA level (quartiles for those under normal range) | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| OR (95% CI) | P value | OR (95% CI) | P value | Q1 | Q2 OR (95% CI) | Q3 OR (95% CI) | Q4 OR (95% CI) | P valuea | |

| Male (n = 716) | |||||||||

| MetS | 1.25 (1.10–1.42) | 0.001 | 1.96 (1.26–3.06) | 0.003 | 1.00 | 1.35 (0.80–2.29) | 1.73 (1.01–2.96) | 2.06 (1.22–3.47) | 0.043 |

| Number of MetS components | 1.25 (1.13–1.39) | <0.001 | 2.01 (1.41–2.88) | <0.001 | 1.00 | 0.83 (0.53–1.22) | 1.49 (0.96–2.28) | 1.49 (1.00–2.00) | <0.001 |

| Individual component | |||||||||

| Central obesity | 1.22 (1.08–1.37) | 0.001 | 2.18 (1.40–3.38) | 0.001 | 1.00 | 1.28 (0.80–2.05) | 1.57 (0.58–2.52) | 1.63 (1.01–2.64) | 0.054 |

| Hypertriglyceridemia | 1.28 (1.11–1.46) | 0.001 | 1.96 (1.23–3.13) | 0.005 | 1.00 | 1.11 (0.60–2.06) | 1.66 (0.91–3.05) | 1.84 (1.02–3.33) | 0.046 |

| Low HDL-C | 1.19 (1.01–1.40) | 0.040 | 1.30 (0.72–2.35) | 0.377 | 1.00 | 0.75 (0.36–1.58) | 1.21 (0.61–2.40) | 1.40 (0.70–2.77) | 0.047 |

| Elevated blood pressure | 1.05 (0.90–1.24) | 0.532 | 1.10 (0.60–2.00) | 0.767 | 1.00 | 0.80 (0.42–1.52) | 0.97 (0.49–1.89) | 1.10 (0.64–1.96) | 0.880 |

| Hyperglycemia | 1.11 (0.99–1.25) | 0.086 | 1.37 (0.90–2.08) | 0.138 | 1.00 | 1.60 (0.97–2.67) | 1.90 (1.13–3.18) | 1.14 (0.68–1.92) | 0.086 |

| Female (n = 995) | |||||||||

| MetS | 1.40 (1.23–1.59) | <0.001 | 2.55 (1.63–3.99) | <0.001 | 1.00 | 0.67 (0.43–1.04) | 1.12 (0.71–1.76) | 1.34 (0.85–2.11) | 0.024 |

| Number of MetS components | 1.35 (1.23–1.45) | <0.001 | 2.07 (2.05–2.82) | <0.001 | 1.00 | 1.83 (1.29–2.59) | 2.10 (1.48–3.00) | 2.47 (1.73–3.54) | <0.001 |

| Individual components | |||||||||

| Central obesity | 1.25 (1.09–1.44) | 0.001 | 1.82 (1.13–2.94) | 0.014 | 1.00 | 0.80 (0.51–1.27) | 1.10 (0.68–1.78) | 1.57 (0.95–2.62) | 0.045 |

| Hypertriglyceridemia | 1.27 (1.13–1.42) | <0.001 | 2.37 (1.63–3.46) | <0.001 | 1.00 | 0.59 (0.38–0.92) | 1.12 (0.75–1.78) | 1.15 (0.73–1.72) | 0.015 |

| Low HDL-C | 1.29 (1.15–1.45) | <0.001 | 1.84 (1.26–2.68) | 0.002 | 1.00 | 0.87 (0.54–1.39) | 1.53 (0.96–2.43) | 1.78 (1.14–2.84) | 0.005 |

| Elevated blood pressure | 1.17 (1.00–1.34) | 0.046 | 1.08 (0.71–1.62) | 0.730 | 1.00 | 0.60 (0.34–1.06) | 1.00 (0.55–1.83) | 1.42 (0.73–2.78) | 0.051 |

| Hyperglycemia | 1.23 (1.10–1.38) | <0.001 | 1.92 (1.33–2.78) | 0.001 | 1.00 | 1.46 (1.02–1.84) | 1.74 (0.78–1.86) | 2.12 (1.50–2.74) | 0.018 |

Adjusted for age, education, marital status, BMI, current smoking, current drinking, physical activity ≥ 0.5 h/day, family history of CVD, medications for hypertension, diabetes, and hyperlipidemia.

a P for trend.

4. Discussion

In this study, we evaluated the association of SUA level and MetS in a Chinese community elderly population. We found that higher SUA level, even within normal range, was associated with an increased prevalence of MetS even after adjusting for confounding factors. This association of MetS risk by SUA levels was more robust in women than in men.

MetS and CVD are rapidly growing threats to public health worldwide, especially in economically developing countries such as China. Just in the past decade, prevalence of MetS in China has increased about 8% [14]. Considering the huge elderly people in China and the strong association of MetS with the development of CVD and diabetes [5], identifying high-risk asymptomatic individuals for MetS is of critical importance and may lead to improvements in prevention and treatment of the subsequent CVD events and increased socioeconomic burden.

A number of studies have researched the association between SUA levels and MetS or its individual components, primarily in adults or institutionalized people. There is little information about the situation in the community elderly, a population with higher prevalence of hyperuricemia and MetS and higher risk of developing CVD events. In this study, we investigated the main components of MetS in the aging population and their potential association with SUA levels. In this representative sample of the Chinese urban elderly, we found a graded positive association between hyperuricemia and the prevalence of MetS. Even in the normal range, SUA level still has higher remarkable increased risk of MetS. And MetS component number was found to rise along with the increase of SUA levels too. This is in accordance with previous studies. Several studies reported that there are significant associations of hyperuricemia with visceral or central obesity, high BMI, TGs, and vascular endothelial dysfunction [16]. A cohort study from Taiwan reported there was remarkable increase of 67% and 21% in the risk of MetS according to different SUA levels [11]. Significantly positive gradient between incidence of MetS and uric acid levels was observed among middle-aged and older participants in the Aerobics Center Longitudinal Study [17]. Also there are studies which indicated the mechanism that decreasing uric acid level may prevent or reverse the course of MetS. One possible biological mechanism is related to insulin-stimulated endothelial nitric oxide synthesis, and hyperuricemia may induce endothelial cell dysfunction and contribute to the development of MetS [18].

The prevalence of hyperuricemia was 16.2% in this population, with 17.5% in men and 16.3% in women, but with no significant difference (P = 0.475). After we calculate the age-specific prevalence, we can see men had a higher prevalence in the younger elderly, while in the participants aged more than 70s, the prevalence of hyperuricemia in women was higher than men. This is contrary to previous studies focused on adults [19, 20]. A meta-analysis including 59 studies of China showed the pooled prevalence of hyperuricemia in adult men was 21.6% (95% CI: 18.9%–24.6%), but it was only 8.6% (95% CI: 8.2%–10.2%) in adult women [21]. Different from these studies, we focused on the elderly and the women have all hit menopause. There is evidence showing estrogens in women may promote more efficient renal clearance of urate and explaining a substantial portion in the SUA level [20, 22]. Gouty arthritis and cardiovascular complications are rarely observed in premenopausal women; however, the incidences of hyperuricemia and MetS increase dramatically after menopause [20]. Also there is evidence which showed that when postmenopausal women with hyperuricemia took hormone replacement therapy, the SUA level and prevalence of hyperuricemia reduced significantly, which suggested a protective effect of estrogen [23, 24].

The present study also provides evidence that elevated SUA level was more strongly associated with MetS in women than in men. Previous studies that performed sex-specific analyses also reported similar results. Sex is clearly an important factor in the relationship between hyperuricemia and MetS. Women with a higher SUA concentration had a higher incidence of hypertension, hypertriglyceridemia, and low HDL-C, as well as increased cardiovascular morbidity and mortality compared to that in men [25]. A cohort study in the Taiwanese showed the hazards ratio of SUA level for MetS is 1.67 and 2.38 in women but only 1.24 and 1.38 in men compared with the lowest tertile [11]. But the underlying mechanism of the sex-related difference is still unclear and needed future investigation.

This is a population-based cross-sectional study with strict training process and quality assurance programs. Wanshoulu district is a representative metropolitan area of the geographic and economic characteristics in Beijing, such as income levels, residential status, and lifestyle factors. The response rate was high and there was no statistically significant difference between participants who completed and those who did not complete the data. Consequently, the findings are more representative than the previous ones, which are mainly about institutionalized patients or health screeners, and potentially reduce the selection bias. Second, our study showed that higher SUA levels, even in the normal range, are strongly associated with the prevalence of MetS. Most studies have revealed the association between obvious hyperuricemia and MetS. The results of our study showed higher SUA levels, even not high enough to the criteria of hyperuricemia, are of elevated risk of MetS. Third, this study explored the sex difference between the association of SUA level and prevalence of MetS, and a stronger association was revealed in women.

There are several limitations in this study which need to be considered. First, the nature of cross-sectional study did not allow us to assess the temporal relationship. Further cohort study with follow-up data is needed to verify the results. Second, the study only included participants who were aged ≥60 years and therefore may not be generalized to young people. But on the other hand, this aged population has a higher prevalence of developing MetS and CVD and would bring on bigger disease burden, so as to give us a critical alert to pay more attention to uric acid in the elderly with MetS and take early prevention actions to prevent serious CVD events. Third, the sex difference in the association of SUA level and MetS risk needs future investigations to explore the underlying mechanisms. Also, we did not have the information whether the women included in the study were taking hormone replacement therapy, which would have impact on both SUA level and MetS prevalence.

5. Conclusions

In summary, the present study showed a strong association between SUA and prevalence of MetS in Chinese community elderly population living in urban Beijing, even in the normal range of SUA level. It also provides additional evidence that SUA is more closely associated with the risk of developing MetS in women than in men. Physicians should recognize MetS as a frequent comorbidity of hyperuricemia and take early action to prevent subsequent chronic disease and related potential socioeconomic burden in the Chinese elderly.

Acknowledgments

This study was supported by research grants from National Natural Science Foundation of China (81072355, 81373080), Ministry of Science and Technology of China (2009BAI86B01), National Public Benefit Research Foundation by the Ministry of Health of China (201002011), Beijing Municipal Science and Technology Commission (D121100004912003), and Science Technological Innovation Nursery Fund of PLA General Hospital (13KMM26). The views and opinions expressed in this paper are those of the authors and do not necessarily reflect the official position of the study sponsors.

Conflict of Interests

The authors declare that there is no conflict of interests regarding the publication of this paper.

References

- 1.Alberti KGMM, Eckel RH, Grundy SM, et al. Harmonizing the metabolic syndrome: a joint interim statement of the international diabetes federation task force on epidemiology and prevention; National heart, lung, and blood institute; American heart association; World heart federation; International atherosclerosis society; and international association for the study of obesity. Circulation. 2009;120(16):1640–1645. doi: 10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.109.192644. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Galassi A, Reynolds K, He J. Metabolic syndrome and risk of cardiovascular disease: a meta-analysis. The American Journal of Medicine. 2006;119(10):812–819. doi: 10.1016/j.amjmed.2006.02.031. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Gami AS, Witt BJ, Howard DE, et al. Metabolic syndrome and risk of incident cardiovascular events and death: a systematic review and meta-analysis of longitudinal studies. Journal of the American College of Cardiology. 2007;49(4):403–414. doi: 10.1016/j.jacc.2006.09.032. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Ford ES, Li C, Sattar N. Metabolic syndrome and incident diabetes: current state of the evidence. Diabetes Care. 2008;31(9):1898–1904. doi: 10.2337/dc08-0423. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Mottillo S, Filion KB, Genest J, et al. The metabolic syndrome and cardiovascular risk: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Journal of the American College of Cardiology. 2010;56(14):1113–1132. doi: 10.1016/j.jacc.2010.05.034. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Chen J, Muntner P, Hamm LL, et al. The Metabolic Syndrome and Chronic Kidney Disease in U.S. Adults. Annals of Internal Medicine. 2004;140(3):167–I39. doi: 10.7326/0003-4819-140-3-200402030-00007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Gu D, Reynolds K, Wu X, et al. Prevalence of the metabolic syndrome and overweight among adults in China. The Lancet. 2005;365(9468):1398–1405. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(05)66375-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.He Y, Jiang B, Wang J, et al. revalence of the metabolic syndrome and its relation to cardiovascular disease in an elderly Chinese population. Journal of the American College of Cardiology. 2006;47(8):1588–1594. doi: 10.1016/j.jacc.2005.11.074. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.So A, Thorens B. Uric acid transport and disease. The Journal of Clinical Investigation. 2010;120(6):1791–1799. doi: 10.1172/JCI42344. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Feig DI, Kang DH, Johnson RJ. Medical progress: uric acid and cardiovascular risk. The New England Journal of Medicine. 2008;359(17):1811–1821. doi: 10.1056/NEJMra0800885. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Yang T, Chu CH, Bai CH, et al. Uric acid level as a risk marker for metabolic syndrome: a Chinese cohort study. Atherosclerosis. 2012;220(2):525–531. doi: 10.1016/j.atherosclerosis.2011.11.014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Tae WY, Ki CS, Hun SS, et al. Relationship between serum uric acid concentration and insulin resistance and metabolic syndrome. Circulation Journal. 2005;69(8):928–933. doi: 10.1253/circj.69.928. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Choi HK, Ford ES. Prevalence of the metabolic syndrome in individuals with hyperuricemia. The American Journal of Medicine. 2007;120(5):442–447. doi: 10.1016/j.amjmed.2006.06.040. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Liu M, Wang J, Jiang B, et al. Increasing prevalence of metabolic syndrome in a Chinese elderly population: 2001–2010. PLoS ONE. 2013;8(6) doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0066233.e66233 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Grundy SM, Cleeman JI, Daniels SR, et al. Diagnosis and management of the metabolic syndrome: an American Heart Association/National Heart, Lung, and Blood Institute scientific statement. Circulation. 2005;112(17):2735–2752. doi: 10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.105.169404. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Lin JD, Chiou WK, Chang HY, Liu FH, Weng HF. Serum uric acid and leptin levels in metabolic syndrome: a quandary over the role of uric acid. Metabolism: Clinical and Experimental. 2007;56(6):751–756. doi: 10.1016/j.metabol.2007.01.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Sui X, Church TS, Meriwether RA, Lobelo F, Blair SN. Uric acid and the development of metabolic syndrome in women and men. Metabolism: Clinical and Experimental. 2008;57(6):845–852. doi: 10.1016/j.metabol.2008.01.030. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Mercuro G, Vitale C, Cerquetani E, et al. Effect of hyperuricemia upon endothelial function in patients at increased cardiovascular risk. The American Journal of Cardiology. 2004;94(7):932–935. doi: 10.1016/j.amjcard.2004.06.032. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Zhang Q, Lou S, Meng Z, Ren X. Gender and age impacts on the correlations between hyperuricemia and metabolic syndrome in Chinese. Clinical Rheumatology. 2011;30(6):777–787. doi: 10.1007/s10067-010-1660-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Rho YH, Woo JH, Choi SJ, Lee YH, Ji JD, Song GG. Association between serum uric acid and the Adult Treatment Panel III-defined metabolic syndrome:. results from a single hospital database. Metabolism: Clinical and Experimental. 2008;57(1):71–76. doi: 10.1016/j.metabol.2007.08.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Liu B, Wang T, Zhao HN, et al. The prevalence of hyperuricemia in China: a meta-analysis. BMC Public Health. 2011;11, article 832 doi: 10.1186/1471-2458-11-832. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.de Souza A, Fernandes V, Ferrari AJ. Female gout: clinical and laboratory features. The Journal of Rheumatology. 2005;32(11):2186–2188. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Hak AE, Choi HK. Menopause, postmenopausal hormone use and serum uric acid levels in US women—the Third National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey. Arthritis research & therapy. 2008;10(5, article R116) doi: 10.1186/ar2519. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Sumino H, Ichikawa S, Kanda T, Nakamura T, Sakamaki T. Reduction of serum uric acid by hormone replacement therapy in postmenopausal women with hyperuricaemia. The Lancet. 1999;354(9179):p. 650. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(99)92381-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Kawamoto R, Tomita H, Oka Y, Ohtsuka N. Relationship between serum uric acid concentration, metabolic syndrome and carotid atherosclerosis. Internal Medicine. 2006;45(9):605–614. doi: 10.2169/internalmedicine.45.1661. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]