INTRODUCTION

Allogeneic hematopoietic stem cell transplantation (HCT) with a myeloablative conditioning (MAC) is a potentially curative treatment for patients with acute myelogenous leukemia (AML) 1,2. However, MAC is associated with significant regimen related toxicity (RRT) and risk of transplant-related mortality (TRM). The introduction of reduced intensity conditioning (RIC) has extended allogeneic transplantation to older and less medically fit patients by reducing RRT 3,4. RIC relies largely on graft-versus leukemia (GVL) effect of the immunocompetent cells in the graft, rather than the high-dose chemotherapy for the anti-tumor effect 1,5-7. Tower response rates and shorter remission duration of relapsed AML after donor lymphocyte infusions 8,9 suggests that it may be less sensitive to the GVL effect, potentially increasing the risk of relapse after RIC.

Donor availability is one of the factors limiting wider utilization of allogeneic HCT in patients with high risk AML that lack human leukocyte antigen (HLA) identical sibling donor 10. Unrelated umbilical cord blood (UCB) has emerged as an alternative source for HCT and may be particularly valuable patients who have a narrow window of opportunity to proceed to transplantation 11. Recent studies showed similar leukemia free survival (LFS) with UCB and unrelated donor (URD) following HCT with MAC in patients with acute leukemia12-16. Our group has reported high rates of engraftment, low treatment-related mortality (TRM) and promising disease-free survival for hematological malignancies with UCB even after RIC HCT 17.

There are limited data comparing the outcomes of AML patients undergoing UCB transplantation after RIC and MAC 18-21, but none include UCB recipients. Thus, we retrospectively studied the outcomes of adults AML patients in complete remission (CR) who underwent UCB transplantation after MAC or RIC regimens in our institution.

PATIENTS AND METHODS

Patients

Patients ≥18 years with AML who received their first allogeneic HCT with an UCB graft between January 2001 and December 2009 were included in this study. This time period was chosen so that recipients of RIC and MAC regimens were offered uniform supportive care and conditioning regimens. Only patients who were in first (CR1) and second (CR2) complete remissions (CR) prior to HCT defined as no morphological evidence of AML in a representative bone marrow biopsy and aspirate, regardless of flow cytometry of cytogenetic results, were eligible for this analysis. For example a patient with 2% of blasts but with Auer rods were not considered in remission and therefore not included in this analysis. Patients with a previous diagnosis of myelodysplastic syndrome (MDS) and myeloproliferative disorders (MPD) were included if they had progressed to AML, were treated, and achieved a CR. Treatment protocols and retrospective analysis were approved by the Institutional Review Board (IRB) of the University of Minnesota and registered at www.clinicaltrials.gov under numbers NCT00305682, NCT00365287, NCT00290641, and NCT0030984. All patients provided written informed consent in accordance with the Declaration of Helsinki before enrollment.

UCB Graft

UCB unit selection has been detailed elsewhere 17,22. In summary, UCB units were matched at antigen level for HLA-A and –B and allele level for HLA-DRB1. UCB units were selected if they were ≤ 2 HLA-mismatches with the recipient and, if the graft consisted of 2 UCB units the units were ≤ 2 HLA-mismatched to each other not necessarily at the same loci. Criteria for the utilization of double UCB grafts followed our institutional practice 17,22. All UCB units were thawed according to the methods of Rubinstein et al 23.

Treatment Plan and Supportive Care

Seventy-four patients received a RIC regimen consisting of fludarabine (40 mg/m2 intravenously daily for 5 days) and 200 cGy total body irradiation (TBI) with cyclophosphamide (50 mg/kg intravenously for 1 day) as described 17. Twenty-two of 74 RIC (30%) patients received equine antithymocyte globulin (ATG, ATGAM; Pharmacia, Kalamazoo, MI) 15 mg/kg every 12 hours; for 3 days as part of the conditioning regimen. Forty-five patients received a MAC regimen consisting of cyclophosphamide (60 mg/kg intravenously daily for 2 days), 1320 cGy TBI given divided in 8 fractions and fludarabine (25 mg/m2 daily for 3 days) as described 22. Graft versus host disease (GVHD) prophylaxis consisted of cyclosporine (days –3 to at least +100) and mycophenolate mofetil (MMF; days –3 to at least +30). Granulocyte–colony-stimulating factor (5 μg/kg per day) was administered to all patients from day +1 until an absolute neutrophil count of 2.5 x 109/L or higher was achieved for 2 consecutive days. All patients received fluconazole or voriconazole for prophylaxis of fungal infections for 100 days and trimethoprim-sulfamethoxazole for prophylaxis of Pneumocystis jiroveci after engraftment for 12 months after transplantation and extended spectrum fluoroquinolones for prophylaxis of Gram-positive organisms during treatment of GVHD. Viral prophylaxis included acyclovir if seropositive for herpes simplex or cytomegalovirus (CMV) before transplantation. CMV surveillance was performed weekly with ganciclovir treatment at the time of positive antigenemia or polymerase chain reaction testing. Chimerism was determined by quantitative PCR of informative polymorphic variable number tandem repeat (VNTR) or short tandem repeat (STR) regions in the recipient and donor as described 22

Endpoints and Definitions

The primary study endpoint was LFS defined as survival without disease relapse. Patients were censored at the time death, relapse or last follow-up. Other study endpoints included cumulative incidences of relapse, TRM, neutrophil recovery, platelet recovery, acute and chronic GVHD. Relapse was defined as disease recurrence at any site. TRM was defined as death due to causes other than leukemia relapse. Time to neutrophil engraftment were measured from the date of transplantation to the date of recovery (defined as the first of 3 consecutive days of absolute neutrophil count 5 × 109/L), with exclusion for early death (ie, death before day 21 without neutrophil recovery). Patients who had no engraftment by day 42 were treated as graft failures. Time to platelet engraftment was defined as a count higher than 50 × 109/L for the first of 7 days without platelet transfusion support. For double UCB recipients, the cell doses (nucleated cells, CD34+ and CD3+) were reported as the combined dose of the UCB donor units, and HLA and ABO matching were defined by the worst matched of the two units. Co-morbidities were scored according to the Hematopoietic Cell Transplantation Specific Co-Morbidity Index (HCT-CI) 24. Diagnostic cytogenetics were classified by Southwest Oncology Group (SWOG) 25 or by presence of monosomal karyotype 26,27.

Statistical Considerations

Patient and transplant characteristics by conditioning intensity were compared using the chi-square test for categorical data and the Wilcoxon rank-sum test for continuous data 28. LFS was calculated using the Kaplan-Meier method 28. Univariate comparisons of all end points were completed by log-rank test 29. Cumulative incidence was used to estimate the endpoints of hematopietic recovery, relapse, TRM and acute and chronic GVHD 30. A Cox proportional hazards model 31or the Fine & Gray method 32 for competing hazards was used for multivariate regression. Variables included in the models were the number of donor UCB units (1 vs. 2), maximum HLA disparity, ABO compatibility, CMV serostatus, disease status at transplantation (first CR (CR1) vs. second CR (CR2) with CR1 duration < 1 year (CR2w/CR1<1y) vs. CR2 with CR1 duration ≥1 year (CR2w/CR1≥1y), diagnostic cytogenetics by Southwest Oncology Group (SWOG) (favorable, intermediate and unfavorable) 25, HCT-CI and conditioning regimen. All factors were tested for the proportional hazards assumption. The conditioning regimen and disease status were included in each model. Age was not included in the models as it was highly correlated with the intensity of the conditioning regimen. Analyses were performed using SAS 9.2 (SAS Institute).

RESULTS

Patient and Grafts Characteristics

Patient characteristics of the 119 eligible patients are shown in Table 1. The two groups were similar for patient and graft characteristics except for age that was in part dictated by the treatment protocol. Median age at transplantation was 55 years for RIC (inter-quartile range, 50-60) and 33 years for MAC group (inter-quartile range, 24-39) (p<0.01). Sixty-six had a RIC solely based age ≥ 45 years and 8 due to preexisting co-morbidities. Forty-eight of 74 RIC patients (65%) and 25 of 45 MAC (56%) were in CR1 (p=0.31) and the remaining patients were in CR2 at UCB transplantation. Twenty-five of 46 patients in CR2 (54%) had CR1 duration less than 1 year and this was similarly distributed in both groups (p=0.9). Detailed results of diagnostic cytogenetic data were available in 115 patients. Thirty RIC (41%) and 17 MAC (38%) patients (p=0.14) had unfavorable risk karyotype according to SWOG classification 25. However, RIC patients had a higher frequency of monosomal karyotype (MK, 11% vs. 2%, p=0.06) that has been shown to carry a poor prognosis 26,27. The HCT-CI scores at the time of transplantation were similar for the 2 groups with 37 RIC (50%) and 17 MAC (40%) patients having a score ≥ 3 (p=0.13). Total nucleated (TNC), CD34+ and CD3+ cell doses were similar for the two treatment groups. The majority of patients received a transplant of 2 UCB units. Donor-recipient HLA disparity was similar between groups.

Table 1.

Demographics of UCB recipients with AML treated with RIC or MAC HCT

| Patient characteristics | RIC | MAC | p-value |

|---|---|---|---|

| Number of patients | 74 | 45 | NA |

| Year of transplant | |||

| 2001-2004 | 32 | 24 | 0.35 |

| 2005-2009 | 68 | 76 | |

| Age | |||

| ≤45 | 11 | 100 | <0.01 |

| Median (range) | 55 (25-69) | 33 (19-43) | |

| Secondary to MDS or MPD | 28 | 4 | <0.01 |

| Disease status | |||

| CR1 | 65 | 56 | 0.31 |

| CR2w/CR1<1y | 16 | 20 | |

| CR2w/CR1>=1y | 19 | 34 | |

| Cytogenetics | |||

| Favorable | 4 | 16 | 0.14 |

| Intermediate | 42 | 31 | |

| Unfavorable | 41 | 38 | |

| Unknown significance | 7 | 7 | |

| Median time from diagnosis to transplant (days),CR1 patients (inter-quartile range) | 128 (102-156) | 112 (84-146) | 0.84 |

| HCT-CI | |||

| 0 | 25 | 16 | 0.13 |

| 1-2 | 25 | 44 | |

| >2 | 50 | 40 | |

| CMV seropositive recipient | 58 | 58 | 0.97 |

| TNC (×107)/kg* Median (range) | 3.3 (0.2-6.3) | 3.9 (1.7-5.9) | 0.32 |

| CD34+ (×105)/kg* Median (range) | 4.9 (1.3-12.9) | 4.9 (1.1-1.9) | 0.34 |

| CD3+ (×106)/kg* Median (range) | 1.3 (0.4-2.6) | 1.3 (0.3-3.0) | 0.96 |

| HLA-matching† | |||

| 4/6 | 51 | 62 | 0.47 |

| 5/6 | 34 | 29 | |

| 6/6 | 15 | 9 | |

| ABO compatibility† | |||

| Matched | 22 | 18 | 0.68 |

| Minor mismatch | 42 | 38 | |

| Major mismatch | 36 | 44 | |

| Number of units | |||

| 1 | 15 | 11 | 0.56 |

| 2 | 85 | 89 | |

| Median follow-up of survivors* (year) | 3.8 (0.6-8.5) | 4.5 (0.7-8.5) | 0.40 |

Abbreviations: UCB, umbilical cord blood; RIC, reduced intensity conditioning; MAC, myeloablative conditioning; HCT, hematopoietic stem cell; MDS, myelodysplastic syndrome; MPD, myeloproliferative disorder; CR1, first complete remission; CR2w/CR1<1y, second complete remission with CR1 duration < 1 year; CR2w/CR1>=1y, second complete remission with CR1 duration ≥ 1 year; HCT-CI, hematopoietic stem cell comorbidity index; CMV, cytomegalovirus; TNC, total nucleated cell dose; HLA, human leukocyte antigen.

For double UCB recipients, the nucleated CD34+ and CD3+ cell doses reported are the combined dose of the UCB donor units.

For double UCB recipients, HLA and ABO matching was defined by the worst matched of the two units.

Leukemia-Free Survival

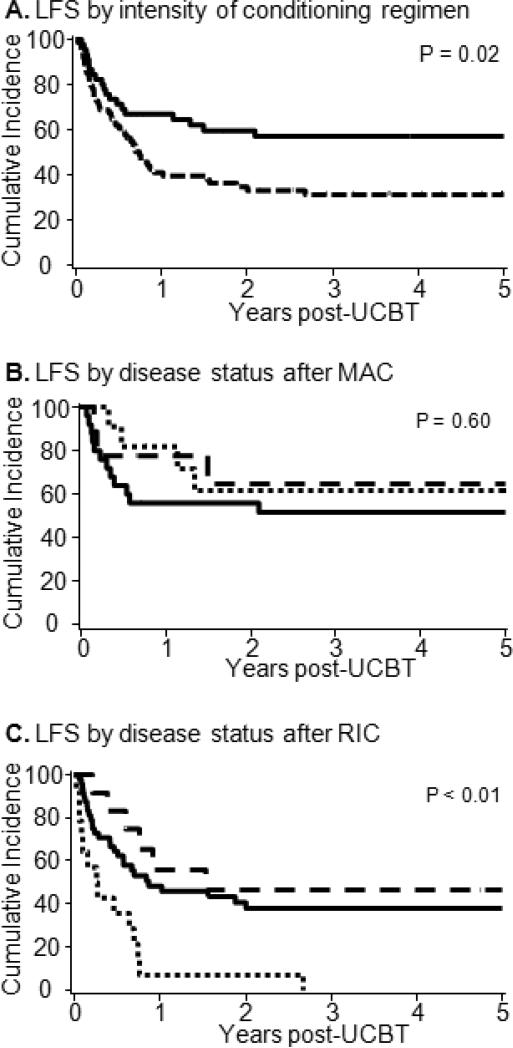

To facilitate the comparison of outcomes between RIC and MAC, point estimates of clinical outcomes are summarized in Table 2. The probability of LFS at 3-years after RIC was 31% (95% CI, 21%-43%) and after MAC 55 %(95% CI, 41%-70%) (Figure 1A). Forty-eight of 74 patients (65%) with RIC and 19 of 45 (42%) patients after MAC relapsed or died with a median time to progression of 0.7 years in the RIC group and not reached after MAC. We then studied the effect of disease status at the time of UCB transplantation on the LFS classifying the patients as CR1, CR2 with a CR1 duration < 1 year (CR2w/CR1<1y), and CR2 with a CR1 duration ≥1 year (CR2w/CR1≥1y). Considering all patients the LFS for patients in CR1 was 43% (95%CI, 31-54%), in CR2w/CR1<1y was 26% (95%CI, 10-45%) and in CR2w/CR1≥1y was 54% (95%CI, 30-73%). When the analysis was limited to recipients of MAC the LFS for patients transplanted in CR1 was 52% (95%CI, 31-69%), in CR2w/CR1≥1y was 65% (95%CI, 25-87%), and in CR2w/CR1<1y was 61% (95%CI, 27-84%) (Figure 1B). In contrast, patients after RIC the LFS was 38% (95%CI, 24-52%) in CR1, 47% (95%CI, 18-72%) in CR2w/CR1≥1y and 7% (95%CI, 1-28%) in CR2w/CR1<1y (Figure 1C). In multivariate analysis, both trhe intensity of the conditioning regimen and disease status at the time of transplantation were independent predictors of LFS (Table 3). Recipients of RIC had a 2.3-fold and CR2 w/CR1<1y a 1.9-foldhigher risk of relapse or death as compared to MAC recipients. The median follow-up of survivors for RIC was 3.8 years (inter-quartile, 1.6-5.9 years) and for MAC 4.5 years (inter-quartile, 2.5-6.5 years) (p=0.4). The most frequent causes of death after RIC (n=20) were relapse 61%, infection 22% and GVHD 5%, while after MAC (n=43) were relapse 32%, infection 36% and GVHD 11%.

Table 2.

Summary of Point Estimates of Study Endpoints

| OUTCOME | Reduced Intensity Conditioning (95%CI) | Myeloablative Conditioning (95%CI) | p-value |

|---|---|---|---|

| Hematopoietic recovery | |||

| Neutrophil recovery at 42 days | 94% (89%-99%) | 82% (71%-93%) | <0.01 |

| Platelet recovery at 6th month | 68% (51%-85%) | 67% (50%/84%) | 0.30 |

| Sustained Donor Engraftment | 86% (78%-94%) | 82% (71%-93%) | 0.57 |

| Grade II-IV acute GVHD | 47% (35%-59%) | 67% (51%-82%) | <0.01 |

| Grade III-IV acute GVHD | 16% (8%-24%) | 31% (18%-44%) | 0.05 |

| Chronic GVHD | 30% (19%-41%) | 34% (19%-49%) | 0.43 |

| 2 year TRM | 19% (10-28%) | 27% (14-40%) | 0.55 |

| Relapse at 3 years | 43% (31%-55%) | 9% (50%-78%) | <0.01 |

| Progression-free survival at 3 years | 31% (21%-43%) | 55% (41%-70%) | 0.02 |

Abbreviations: CI, confidence interval; GVHD, graft versus host disease; TRM, transplant related mortality.

Figure 1.

Leukemia-free survival of AML patients in CR1-2 who underwent umbilical cord blood transplantation (A) after myeloablative vs. nonmyeloablative conditioning; (B) for patients receiving after myeloablative or (C) nonmyeloablative conditioning according to disease status at the time of transplantation categorized as first complete remission (CR1,—), second complete remission with CR1 duration < 1 year (□ □ □ □ □ □) and second complete remission with CR1 ≥ 1year (— — —).

Table 3.

Multivariate analysis of outcomes

| Outcome | Relative risk | 95% CI | p-value |

|---|---|---|---|

| Progression free survival | |||

| Conditioning intensity | |||

| MAC | 1.0 | ||

| RIC | 2.3 | 1.3-4.0 | <0.01 |

| Disease status at HCT | |||

| CR1 | 1.0 | ||

| CR2w/CR1<1y | 1.9 | 1.0-3.4 | 0.03 |

| CR2w/CR1≥1y | 0.7 | 0.3-1.4 | 0.33 |

| Relapse incidence | |||

| Conditioning intensity | |||

| MAC | 1.0 | ||

| RIC | 4.7 | 2.0-11.0 | <0.01 |

| Disease status at HCT | |||

| CR1 | 1.0 | ||

| CR2w/CR1<1y | 1.9 | 1.0-3.8 | 0.06 |

| CR2w/CR1≥1y | 0.5 | 0.2-1.5 | 0.21 |

| Treatment-Related Mortality | |||

| Conditioning Intensity | |||

| Myeloablative* | 1.0 | ||

| Non-Myeloablative | 0.6 | 0.3-1.4 | 0.24 |

| Disease status at TX | |||

| CR1 | 1.0 | ||

| CR2w/CR1<1y | 0.9 | 0.3-2.7 | 0.86 |

| CR2w/CR1≥1y | 1.1 | 0.4-3.1 | 0.85 |

Abbreviations: MAC, myeloablative conditioning; RIC, reduced intensity conditioning; HCT, hematopoietic stem cell transplantation; CR1, first complete remission; CR2w/CR1<1y, second complete remission with CR1 duration < 1 year; CR2w/CR1>=1y, second complete remission with CR1 duration ≥ 1 year

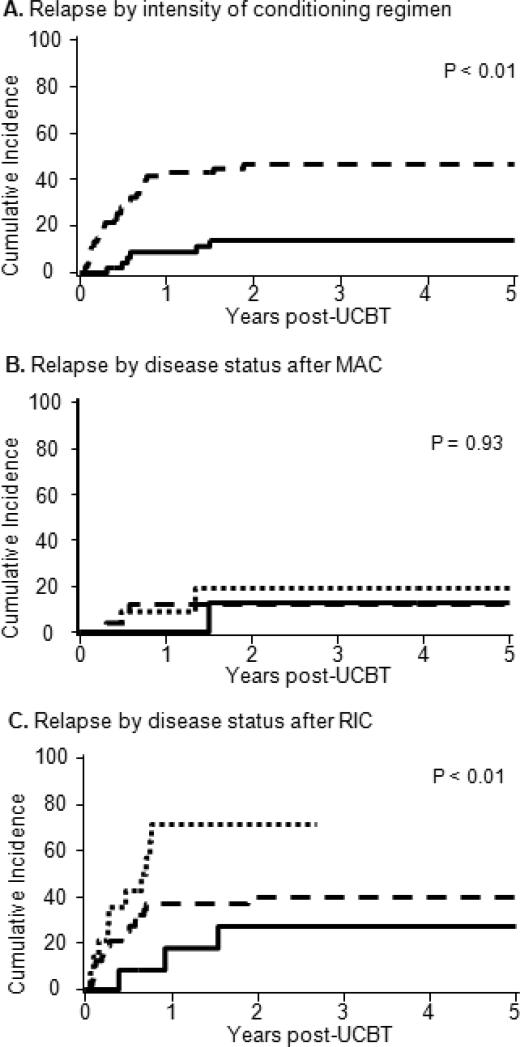

Relapse

The cumulative incidence of relapse at 3-years after RIC was 43% (95%CI, 31%-55%) and after MAC was 9% (95%CI, 50%-78%; p<0.01) (Figure 2A). The overall incidence of relapse for patients in CR1 was 30% (95%CI, 19-41%), in CR2 w/CR1<1y was 48% (95%CI, 27-69%) and in CR2 w/CR1≥1y was 21% (95%CI, 3-39%) (p=.08). In recipients of MAC the relapse incidence in CR1 was 12% (95%CI, 0-24%), in CR2w/CR1<1y was 19% (95%CI, 0-42%), and in CR2w/CR1≥1y was 13% (95%CI, 0-33%) (Figure 2B). In contrast, patients with RIC had relapse incidences in CR1 was 40% (95%CI, 25-55%), in CR2w/CR1<1y was 71% (95%CI, 21-99%), and in CR2w/CR1≥1y was 27% (95%CI, 2-52%) (Figure 2C). Median time to relapse was 1.8 years in RIC and not-reached in MAC groups. In multivariate analysis, after adjusting for disease status at transplantation, RIC had a 4.7 fold higher risk of relapse as compared to MAC recipients (Table 3).

Figure 2.

Cumulative incidence of relapse for AML patients in CR1-2 who underwent umbilical cord blood transplantation (A) after myeloablative vs. nonmyeloablative conditioning; (B) for patients receiving after myeloablative or (C) nonmyeloablative conditioning according to disease status at the time of transplantation categorized as first complete remission (CR1,——), second complete remission with CR1 duration < 1 year (□ □ □ □ □) and second complete remission with CR1 ≥ 1year (— — —).

Treatment Related Mortality

TRM at 2 years was similar in the RIC and MAC groups (19% [95%CI, 10-28%] vs. 27% [95%CI, 14-40%], p=0.5). Neither receiving a TNC cell dose above or below the median (21%, [95%CI, 11-31%] vs. 23% [95%CI, 12-34%], p=.75) nor a CD34+ cell dose above or below the median (22% [95%CI< 12-32%] vs. 22% [95%CI, 14-30%], p=.79) affected the incidence of TRM. The incidence of TRM for patients with HCT-CI score of 0 was 17% (95%CI, 2-32%), 1-2 was 16% (95%CI, 4-28%) and ≥ 3 was 29% (95%CI, 14-41%) (p=.31). TRM was also not significantly influenced by whether patients were transplanted in CR1 (22%, 95%CI, 12-32%), CR2 w/CR1<1yr (20%, 95%CI, 4-36%) or CR2 w/CR1≥1yr (24%, 95%CI, 6-42%) (p=.99). None of the variables considered were found to be independent predictors of TRM in the multivariate model.

Hematopoietic Recovery

The cumulative incidence of neutrophil recovery at day 42 after RIC was 94% (95%CI, 89-99%) at a median of 10 days (range, 5-39 days) and after MAC was 82% (95%CI 71-93%) at a median of 23 days (range, 13-38 days) (p<.01). In contrast, the proportion with full chimerism at day 21 among evaluable patients (n=105) after RIC was 20% (95%CI,10-30%) and after MAC was 60% (95%CI, 45-75) (p<.01); the difference was no longer present in evaluable patients (n=85) at day 100 when after RIC was 84% (95%CI, 74-94%) and after MAC was 94% (95%CI, 86-100%) (p=.15). Thus, when considering all patients the probability of sustained donor engraftment was also similar for recipients of RIC (86%, 95%CI, 78-94%) and MAC (82%, 95%CI, 71-93%) (p=.57). The cumulative incidence of platelet recovery ≥ 50,000/µL after RIC was 68% (95%CI, 51-85%) at a median time of 55 days (range 0-181 days) and after MAC was 67% (95% CI, 50-84%) at a median of 77 days (range 42-177 days) (p=0.30).

Graft-vs.-Host Disease

The incidences of grade II-IV acute GVHD after RIC was 47% (95%CI, 35-59%) and after MAC was 67% (95%CI, 51-82%) (p<.01). Similarly, the incidence of grade III-IV acute GVHD were lower after RIC as compared to MAC (Table 2). However, in the time period on this study only a subgroup of patients receiving a RIC were treated with ATG (n=22, 30%), but none of those receiving MAC. Thus, when studied the incidence of grade II-IV acute GVHD by deviding the RIC in those who received ATG or not. We found that the incidence of grade II-IV acute GVHD after RIC with ATG was 27% (95%CI, 9-45%) and without ATG was 56% (95%CI, 41-71%). In contrast, the 2-year incidence of chronic GVHD was not different between RIC and MAC recipients.

DISCUSSION

We studied the effect of the intensity of the conditioning regimen on the outcome of allogeneic transplantation for patients with AML in CR1-2. The main observations of our study were that 1) after MAC there was a lower risk of relapse and superior LFS, and 2) TRM was similar regardless of the intensity of the conditioning regimen, 3) the risk of acute GVHD was lower after RIC and 4) similar rates of sustained donor engraftment.

While single center and registry data both support the use RIC transplantation in AML 18-21,33-36, to date there have been no randomized clinical trials that studied the effect of the intensity of the conditioning regimen on allogeneic transplantation outcomes in AML or hematological malignancy. As compared to studies that compared the outcomes of RIC and MAC recipients 18-21, our study is unique as it included only recipients of UCB grafts and patients receive uniform conditioning regimens (within their respective groups) and supportive care. In the MRD setting, the European Group for Blood and Marrow Transplantation Group (EBMT) showed increased incidence of relapse, but no difference in LFS after RIC in AML patients older than age 50 after an allogeneic HCT with from a MSD 19 . In the MUD setting, while for patients > 50 years enjoyed similar risk of relapse and LFS regardless of the intensity of the conditioning regimen in patients < 50 years the relapse risk was increased after RIC but LFS were similar 20. Recently the Center for International Blood and Marrow Transplantation and Research (CIBMTR) compared the outcomes after RIC vs. MAC in AML and MDS patients allografted with either unrelated or related donors and reported higher relapse incidence after RIC but an only a marginally better LFS for those after MAC 34. While theses registry based studies also included patients with active disease, we included only patients in CR1-2. Notably, patients in CR1 and those CR2 with longer CR1 derived greater benefit from RIC UCB transplantation. Thus, comprehensive molecular and cytogenetic evaluation and risk stratification at diagnosis in order to consider high risk AML patients for allogeneic transplantation in early disease stages seems warranted.

In this study, the risk of relapse after MAC was relatively low (14% at 3 years), compares favorably to that of other donor sources 19,20 , and is consistent with a recent collaboration between us the Fred Hutchinson Cancer Research Center in Seattle 15. While, a significantly higher risk of relapse after RIC was not unexpected, the outcome of patients in CR2 with short CR1 was disappointing. As our study included only adults, most received double UCB grafts that have been shown by us to be associated with a lower risk of relapse after MAC 37; no similar data are available in the RIC setting. The mechanism of the favorable relapse risk after MAC remains to be determined but may be explained in part by patient selection and the high proportion of grafts with 2 HLA disparities. Cross-immune activation between the 2 units as has been shown by Gutman et al 38 may also play a role in promoting GVL. Available data do not support a role for KIR-ligand mismatching in reducing the risk of relapse in double UCB transplantation 39. Preceeding MDS/MPD 40 and monosomal karyotype 26,27 both of which have been shown to be associated with poorer outcomes after HCT were more frequent in RIC group and may have contributed to the higher risk of relapse. I one third of the RIC recipients, the in vivo T-cell depletion secondary to the administration of ATG could explain, at least in part, the overall greater risk of relapse as shown in other settings 41. In this retrospective study we lacked molecular data on enough patients to study its influence on the risk of relapse. Considering RIC patient were older compared with MAC in our study, it is possible that poor prognosis inherent with older age could not be overcome the GVL effect of RIC UCB transplantation. While a larger study is required to better determine the risk factors associated with the higher risk of relapse after RIC UCB, recipients of RIC UCB transplantation with early stage disease have relapse risk similar to that of the MAC. Alternative strategies such as higher intensity conditioning and/or post-transplantation anti-leukemic therapy may be considered for patients with high risk leukemia who had a short CR1.

We observed similar incidence of TRM between RIC and MAC what is consistent with the finding of both EBMT 19,20 and CIBMTR studies 21. While in older patients may enjoy reduced TRM by offering RIC 20, this may compromise LFS. Typically, RIC are older and only the younger with co-morbidities are typically considered this type of treatment. Our institutional defined age cut off for offering RIC rather than MAC UCB transplantation may need to be revised, in particular for older patients who are in good clinical condition and are likely to tolerate more intensive therapy. Less clinically fit patients who are poor candidates for MAC need to be counseled on the relative risk benefit of RIC UCB early in the course of their disease so that the opportunity to administer potentially curative therapy is not missed.

While a lower risk of acute GVHD has been described among patients receiving RIC 19, our finding contrasts with data from our own center that previously found higher risk of acute GVHD among recipients of RIC 42. This discrepancy is, at least in part, explained by patient selection. As we only included patients transplanted in the same time period since we had both RIC and MAC regimens to assure homogenous supportive care, 30% of the RIC but none of the MAC patients received ATG as part of the conditioning regimen. However, as the age groups hardly overlap due to protocol-defined eligibility criteria, we cannot exclude that the lesser tissue damage of RIC could have contributed to the lower risk of GVHD in this setting even in this older group of patients 43.

As compared to adult donor stem cell sources, the incidence of hematopoietic recovery after UCB transplantation is typically lower after MAC 13-15,44,45, and RIC 46. Not unexpectedly we found that the time to neutrophil recovery was shorter after RIC, but notably there was no difference in the incidence of sustained donor engraftment between the 2 groups. We and other have previously shown that UCB has enough immune cell to reproducibly engraft after RIC 17,47-50. This observation demonstrates that concerns about donor engraftment depending on the intensity of the conditioning regimen should not be a factor limiting an AML patient in remission from proceeding to UCB transplantation.

In summary, while the morbidity, as measured by the risk of TRM, of RIC and MAC UCB transplant are similar but that disease control after RIC, especially among those with short lived CR1, is suboptimal. Our study highlights the importance of careful risk stratification at the time of diagnosis, in particular for older patients that are natural candidates to RIC, so that high risk patients are considered for transplantation in CR1 rather than in CR2 after a short lived CR1.

Acknowledgments

This work was supported in part by grants from the National Cancer Institute CA65493 (C.G.B, J.E.W.), the Children’s Cancer Research Fund (J.E.W., T.E.D.), Leukemia and Lymphoma Society Scholar in Clinical Research Award (C.G.B.).

REFERENCES

- 1.Cornelissen JJ, van Putten WL, Verdonck LF, et al. Results of a HOVON/SAKK donor versus no-donor analysis of myeloablative HLA-identical sibling stem cell transplantation in first remission acute myeloid leukemia in young and middle-aged adults: benefits for whom? Blood. 2007;109:3658–66. doi: 10.1182/blood-2006-06-025627. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Koreth J, Schlenk R, Kopecky KJ, et al. Allogeneic stem cell transplantation for acute myeloid leukemia in first complete remission: systematic review and meta-analysis of prospective clinical trials. Jama. 2009;301:2349–61. doi: 10.1001/jama.2009.813. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Forman SJ. What is the role of reduced-intensity transplantation in the treatment of older patients with AML? Hematology Am Soc Hematol Educ Program. 2009:406–13. doi: 10.1182/asheducation-2009.1.406. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.McClune BL, Weisdorf DJ, Pedersen TL, et al. Effect of age on outcome of reduced-intensity hematopoietic cell transplantation for older patients with acute myeloid leukemia in first complete remission or with myelodysplastic syndrome. J Clin Oncol. 2010;28:1878–87. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2009.25.4821. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Baron F, Storb R, Storer BE, et al. Factors associated with outcomes in allogeneic hematopoietic cell transplantation with nonmyeloablative conditioning after failed myeloablative hematopoietic cell transplantation. J Clin Oncol. 2006;24:4150–7. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2006.06.9914. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Giralt S, Estey E, Albitar M, et al. Engraftment of allogeneic hematopoietic progenitor cells with purine analog-containing chemotherapy: harnessing graft-versus-leukemia without myeloablative therapy. Blood. 1997;89:4531–6. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Hegenbart U, Niederwieser D, Sandmaier BM, et al. Treatment for acute myelogenous leukemia by low-dose, total-body, irradiation-based conditioning and hematopoietic cell transplantation from related and unrelated donors. J Clin Oncol. 2006;24:444–53. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2005.03.1765. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Kolb HJ, Schattenberg A, Goldman JM, et al. Graft-versus-leukemia effect of donor lymphocyte transfusions in marrow grafted patients. Blood. 1995;86:2041–50. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Collins RH, Jr., Shpilberg O, Drobyski WR, et al. Donor leukocyte infusions in 140 patients with relapsed malignancy after allogeneic bone marrow transplantation. J Clin Oncol. 1997;15:433–44. doi: 10.1200/JCO.1997.15.2.433. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Beatty PG, Boucher KM, Mori M, et al. Probability of finding HLA-mismatched related or unrelated marrow or cord blood donors. Hum Immunol. 2000;61:834–40. doi: 10.1016/s0198-8859(00)00138-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Barker JN, Rocha V, Scaradavou A. Optimizing unrelated donor cord blood transplantation. Biol Blood Marrow Transplant. 2009;15:154–61. doi: 10.1016/j.bbmt.2008.10.020. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Eapen M, Rocha V, Sanz G, et al. Effect of graft source on unrelated donor haemopoietic stem-cell transplantation in adults with acute leukaemia: a retrospective analysis. Lancet Oncol. 2010 doi: 10.1016/S1470-2045(10)70127-3. in press. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Laughlin MJ, Eapen M, Rubinstein P, et al. Outcomes after transplantation of cord blood or bone marrow from unrelated donors in adults with leukemia. N Engl J Med. 2004;351:2265–75. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa041276. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Rocha V, Labopin M, Sanz G, et al. Transplants of umbilical-cord blood or bone marrow from unrelated donors in adults with acute leukemia. N Engl J Med. 2004;351:2276–85. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa041469. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Brunstein CG, Gutman JA, Weisdorf DJ, et al. Allogeneic Hematopoietic Cell Transplantation for Hematological Malignancy: Relative Risks and Benefits of Double Umbilical Cord Blood. Blood. 2010 doi: 10.1182/blood-2010-05-285304. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Eapen M, Logan BR, Confer DL, et al. Peripheral blood grafts from unrelated donors are associated with increased acute and chronic graft-versus-host disease without improved survival. Biol Blood Marrow Transplant. 2007;13:1461–8. doi: 10.1016/j.bbmt.2007.08.006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Brunstein CG, Barker JN, Weisdorf DJ, et al. Umbilical cord blood transplantation after nonmyeloablative conditioning: impact on transplantation outcomes in 110 adults with hematologic disease. Blood. 2007;110:3064–70. doi: 10.1182/blood-2007-04-067215. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Alyea EP, Kim HT, Ho V, et al. Comparative outcome of nonmyeloablative and myeloablative allogeneic hematopoietic cell transplantation for patients older than 50 years of age. Blood. 2005;105:1810–4. doi: 10.1182/blood-2004-05-1947. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Aoudjhane M, Labopin M, Gorin NC, et al. Comparative outcome of reduced intensity and myeloablative conditioning regimen in HLA identical sibling allogeneic haematopoietic stem cell transplantation for patients older than 50 years of age with acute myeloblastic leukaemia: a retrospective survey from the Acute Leukemia Working Party (ALWP) of the European group for Blood and Marrow Transplantation (EBMT). Leukemia. 2005;19:2304–12. doi: 10.1038/sj.leu.2403967. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Ringden O, Labopin M, Ehninger G, et al. Reduced intensity conditioning compared with myeloablative conditioning using unrelated donor transplants in patients with acute myeloid leukemia. J Clin Oncol. 2009;27:4570–7. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2008.20.9692. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Luger S, Ringden O, Perez WS, et al. Similar outcomes Using Myeloabaltive versus Reduced Intensity and Non-Myeloablative Allogeneic Transplant Preparative Regimens for AML or MDS: From the Center for Interantional Blood and Marrow Transplantat and Research. Blood. 2008;112:136. doi: 10.1038/bmt.2011.69. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Barker JN, Weisdorf DJ, DeFor TE, et al. Transplantation of 2 partially HLA-matched umbilical cord blood units to enhance engraftment in adults with hematologic malignancy. Blood. 2005;105:1343–7. doi: 10.1182/blood-2004-07-2717. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Rubinstein P, Dobrila L, Rosenfield RE, et al. Processing and cryopreservation of placental/umbilical cord blood for unrelated bone marrow reconstitution. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 1995;92:10119–22. doi: 10.1073/pnas.92.22.10119. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Sorror ML, Maris MB, Storb R, et al. Hematopoietic cell transplantation (HCT)-specific comorbidity index: a new tool for risk assessment before allogeneic HCT. Blood. 2005;106:2912–9. doi: 10.1182/blood-2005-05-2004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Slovak ML, Kopecky KJ, Cassileth PA, et al. Karyotypic analysis predicts outcome of preremission and postremission therapy in adult acute myeloid leukemia: a Southwest Oncology Group/Eastern Cooperative Oncology Group Study. Blood. 2000;96:4075–83. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Breems DA, Van Putten WL, De Greef GE, et al. Monosomal karyotype in acute myeloid leukemia: a better indicator of poor prognosis than a complex karyotype. J Clin Oncol. 2008;26:4791–7. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2008.16.0259. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Oran B, Dolan M, Cao Q, et al. Monosomal Karyotype Provides Better Prognostic Prediction after Allogeneic Stem Cell Transplantation in AML Patients. Biol Blood Marrow Transplant. 2010 doi: 10.1016/j.bbmt.2010.05.012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Kaplan EL, Meier P. Nonparametric estimation from incomplete observations. J Am Stat Assoc. 1958;53:457–481. [Google Scholar]

- 29.Snedecor G, Cochran W. Statistical Methods. ed 8th Iowa State University Press; 1989. [Google Scholar]

- 30.Lin DY. Non-parametric inference for cumulative incidence functions in competing risks studies. Stat Med. 1997;16:901–10. doi: 10.1002/(sici)1097-0258(19970430)16:8<901::aid-sim543>3.0.co;2-m. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Cox DR. Regression models and life tables. J Royal Stat Soc B. 1972;34:187–220. [Google Scholar]

- 32.Fine JP, Gray RJ. A proportional hazards model for the subdistribution of a competing risk. J Am Stat Assoc. 1999;94:496–509. [Google Scholar]

- 33.McClune BL, Weisdorf DJ. Reduced-intensity conditioning allogeneic stem cell transplantation for older adults: is it the standard of care? Curr Opin Hematol. 17:133–8. doi: 10.1097/MOH.0b013e3283366ba4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Oran B, Giralt S, Saliba R, et al. Allogeneic hematopoietic stem cell transplantation for the treatment of high-risk acute myelogenous leukemia and myelodysplastic syndrome using reduced-intensity conditioning with fludarabine and melphalan. Biol Blood Marrow Transplant. 2007;13:454–62. doi: 10.1016/j.bbmt.2006.11.024. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Mohty M, de Lavallade H, El-Cheikh J, et al. Reduced intensity conditioning allogeneic stem cell transplantation for patients with acute myeloid leukemia: long term results of a ‘donor’ versus ‘no donor’ comparison. Leukemia. 2009;23:194–6. doi: 10.1038/leu.2008.164. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Schetelig J, Bornhauser M, Schmid C, et al. Matched unrelated or matched sibling donors result in comparable survival after allogeneic stem-cell transplantation in elderly patients with acute myeloid leukemia: a report from the cooperative German Transplant Study Group. J Clin Oncol. 2008;26:5183–91. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2007.15.5184. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Verneris MR, Brunstein CG, Barker J, et al. Relapse risk after umbilical cord blood transplantation: enhanced graft-versus-leukemia effect in recipients of 2 units. Blood. 2009;114:4293–9. doi: 10.1182/blood-2009-05-220525. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Gutman JA, Turtle CJ, Manley TJ, et al. Single unit dominance following double unit umbilical cord blood transplantation coincides with a specific CD8+ T cell response against the non-engrafted unit. Blood. 2009 doi: 10.1182/blood-2009-07-228999. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Brunstein CG, Wagner JE, Weisdorf DJ, et al. Negative effect of KIR alloreactivity in recipients of umbilical cord blood transplant depends on transplantation conditioning intensity. Blood. 2009;113:5628–34. doi: 10.1182/blood-2008-12-197467. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Smith M, Barnett M, Bassan R, et al. Adult acute myeloid leukaemia. Crit Rev Oncol Hematol. 2004;50:197–222. doi: 10.1016/j.critrevonc.2003.11.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Wagner JE, Thompson JS, Carter SL, et al. Effect of graft-versus-host disease prophylaxis on 3-year disease-free survival in recipients of unrelated donor bone marrow (T-cell Depletion Trial): a multi-centre, randomised phase II-III trial. Lancet. 2005;366:733–41. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(05)66996-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.MacMillan ML, Weisdorf DJ, Brunstein CG, et al. Acute graft-versus-host disease after unrelated donor umbilical cord blood transplantation: analysis of risk factors. Blood. 2009;113:2410–5. doi: 10.1182/blood-2008-07-163238. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Socie G, Blazar BR. Acute graft-versus-host disease: from the bench to the bedside. Blood. 2009;114:4327–36. doi: 10.1182/blood-2009-06-204669. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Eapen M, Rubinstein P, Zhang MJ, et al. Outcomes of transplantation of unrelated donor umbilical cord blood and bone marrow in children with acute leukaemia: a comparison study. Lancet. 2007;369:1947–54. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(07)60915-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Eapen M, Scaradavou A, Gluckman E, et al. Effect of stem cell source on transplant outcomes in adults with acute leukemia: A comparison of unrelated bone marrow (BM), peripheral blood (PB) and cord blood (CB). Blood. 2009 In Press. [Google Scholar]

- 46.Brunstein CG. UCB vs PBSC URD in RIC for acute leukemia. Blood. 116:2010. [Google Scholar]

- 47.Ballen KK, Spitzer TR, Yeap BY, et al. Double unrelated reduced-intensity umbilical cord blood transplantation in adults. Biol Blood Marrow Transplant. 2007;13:82–9. doi: 10.1016/j.bbmt.2006.08.041. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Barker JN, Weisdorf DJ, DeFor TE, et al. Rapid and complete donor chimerism in adult recipients of unrelated donor umbilical cord blood transplantation after reduced-intensity conditioning. Blood. 2003;102:1915–9. doi: 10.1182/blood-2002-11-3337. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Miyakoshi S, Yuji K, Kami M, et al. Successful engraftment after reduced-intensity umbilical cord blood transplantation for adult patients with advanced hematological diseases. Clin Cancer Res. 2004;10:3586–92. doi: 10.1158/1078-0432.CCR-03-0754. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Morii T, Amano I, Tanaka H, et al. Reduced-Intensity Unrelated Cord Blood Transplantation (RICBT) in Adult Patients with High-Risk Hematological Malignancies. Blood. 2005;106:444b. [Google Scholar]