Abstract

Patients with heart disease and depression have an increased mortality rate. Both behavioral and biologic factors have been proposed as potential etiologic mechanisms. Given that the pathophysiology of depression is thought to involve disruption in brain serotonergic signaling, we investigated platelet response to serotonin stimulation in patients with stable coronary artery disease (CAD). We enrolled 92 patients with stable CAD. Platelet response to increasing concentrations of serotonin (5HT), epinephrine-augmented 5HT, and ADP was measured by optical aggregation and flow cytometry. As concentrations of 5HT and ADP increased, so did the activation and aggregation of the platelets. However, upon addition of the highest concentration of 5HT (30 uM), a significant decrease in platelet activation (p = 0.005) was detected by flow cytometry. This contrasts the increase in platelet activation seen with the addition of the highest concentration of ADP. In conclusion, we found increased platelet activation and aggregation with increased concentrations of ADP; however, when platelets are stimulated with a high concentration of 5HT (30 uM), there is decreased platelet activation. The data demonstrate unique patterns of platelet activation by 5HT in patients with stable CAD. The cause of this phenomenon is unclear. Our study sheds light on the in-vitro response of platelet function to serotonin in patients with stable CAD which may further the mechanistic understanding of heart disease and depression.

Keywords: Platelets, Serotonin, Depression, Heart Disease

Platelet reactivity is a key component of the pathophysiology of coronary atherosclerosis1. Potent vasoconstrictors such as adenosine diphosphate (ADP), epinephrine and thromboxane have been well studied in patients with stable coronary artery disease (CAD). Mental stress has been shown to induce platelet activation among patients with CAD2. Serotonin (5-HT) has recently gained increasing interest as greater evidence collects on depression as an independent risk factor for cardiovascular disease. 5-HT has been thought to be the link between the two diseases of CAD and depression3. 5-HT has been shown to also mediate an exaggerated platelet response in patients with acute coronary syndrome4. There has been a recent cross-sectional study showing increased platelet reactivity to serotonin in depressed patients 3 months after an ACS5. However, to our knowledge, no study has examined 5-HT-mediated platelet activity in truly stable CAD without an event within one year. To further delineate the role of serotonin in heart disease, we conducted a study to observe the physiologic response of platelets to direct serotonin challenge and augmented serotonin challenge in patients with stable CAD.

Methods

We enrolled 92 patients with stable CAD from a single urban academic medical center between February 2011 and July 2013. Patients were designated as stable CAD patients if they had CAD diagnosed by cardiac catheterization (≥50% coronary stenosis), ECG criteria of myocardial infarction, or stress testing revealing ischemia or infarction. Patients were recruited from outpatient cardiology clinics when they presented for scheduled follow-up and who by report had been taking daily aspirin therapy for at least six months. Exclusion criteria included an acute coronary syndrome within the past year prior to enrollment, current or previous (14 days) use of glycoprotein IIb/IIIa, active narcotic use by personal report or laboratory testing, inability to give informed consent, baseline platelet count <100 K/μl, current use of antidepressants, and chronic disease with a <1 year expected mortality.

The study was approved by the Johns Hopkins Institutional Review Board and all patients provided written informed consent. All patients had platelet functional testing.

Study participants had blood drawn and immediately centrifuged to obtain platelet rich plasma (PRP). Once PRP was obtained, the remainder of the blood was centrifuged to form Platelet Poor Plasma (PPP) as a control. Flow cytometry was performed to measure platelet activation brought on by varying concentrations of serotonin and ADP. The PRP was diluted to the same concentrations for each patient sample (250 ± 20 ×103 platelets/μL) and incubated with various concentrations of serotonin hydrochloride (0.3, 3,5,15, and 30 μmolar) and ADP (0.5, 5, 10, 20 μmolar). 1mM Epinephrine was not used to boost platelet activation levels in this analysis due to the sensitivity of flow cytometry on detecting even minimal expressions of platelet activation. RGDS (Sigma Aldrich) was used as a negative control. For flow cytometry PAC-1-FITC (Sigma Aldrich) was used to determine the conformational change of activated platelets, while anti-CD61-PerCP (Sigma Aldrich) was used to label platelets for analysis. These samples were incubated at room temperature, and quenched with 1% paraformaldehyde (Polysciences). These samples were analyzed using a FACS-Caliber® flow cytometer (Beckton Dickinson, Franklin Lakes, New Jersey). The results were represented as histograms and dot plots using Cell Quest 3.1 software (Beckton Dickinson, Franklin Lakes, New Jersey).

Platelet aggregation was assessed using standard light transmission in PRP. Serotonin-Hydrochloride and adenosine diphosphate (ADP) were added to PRP to obtain 0.3, 3, 5, 15, and 30 μmolar serotonin and 0.5, 5, 10, 20 μmolar ADP concentrations respectively. The range of concentrations used is the same as a recent study conducted showing association of depression score and platelet aggregation in patients with ACS6. Unlike ADP, 5-HT, in vitro, is a very weak platelet agonist that causes reversible platelet aggregation and is considered a ‘helper agonist’ hence it is generally used in conjunction with a second agonist when measuring platelet aggregation7. A fixed dose of epinephrine was chosen because it induces an increase in the maximal response to 5-HT without changing the EC50 value of 5-HT or the affinity of 5-HT to the platelet 5HT2A 4. 1 mM arachidonic acid was used to assess aspirin response.

Distributions of demographic and clinical characteristics of the study sample are described as mean and standard deviation for continuous variables and as frequency (%) for categorical variables. The association of epinephrine–augmented serotonin platelet aggregation or serotonin stimulated platelet activation as measured by flow cytometry, as well as ADP-induced platelet aggregation and activation as dependent variables with agonist dose, adjusted for sex or race was assessed using mixed model regression, with random effect for within-individual repeat measurements. To assess whether there may be confounding by gender or race on either epinephrine–augmented serotonin platelet aggregation or serotonin stimulated platelet activation as measured by flow cytometry, as well as ADP-induced platelet aggregation and activation we initially controlled for both gender and race and found no differences in either serotonin or ADP induced platelet aggregation and activation, therefore we report data unadjusted for gender or race.

Results

Demographic and clinical characteristics of the 92 stable CAD patients are presented in Table 1. The mean age of the participants was 66 years. Men comprised 67% of the population. The mean body mass index (BMI) was 32 kg/m2. The predominant race was white (87%) with 12% African Americans. Two thirds had prior myocardial infarction in the past with 29% requiring prior coronary artery bypass surgery and 95% having a prior percutaneous intervention. Fifteen percent had a history of depression in the past. Half of the population had a family history of early CAD and most had hypertension and dyslipidemia. Thirteen percent of the enrolled population were current smokers. Thirty-eight percent were diabetic. As a prerequisite requirement, all participants were on aspirin therapy. One third of the participants were on Clopidogrel therapy in addition to their aspirin therapy.

TABLE 1.

Characteristics of patients with stable coronary artery disease

| Variable | Total (N=92) |

|---|---|

| Age (years) | 66 ± 9 |

| Men | 62 (67%) |

| Body Mass Index (kg/m2) | 32 (19–61) |

| European American | 80 (87%) |

| African American | 11 (12%) |

| Asian | 1 (1%) |

| Prior Myocardial Infarction | 61 (66%) |

| Prior Coronary Artery Disease | 92 (100%) |

| Prior Coronary Artery Bypass | 27 (29%) |

| Prior Percutaneous Intervention | 87 (95%) |

| Diabetes Mellitus | 35 (38%) |

| Hypertension* | 78 (85%) |

| Dyslipidemia* | 82 (89%) |

| History of Depression | 14 (15%) |

| Current Smoker | 12 (13%) |

| Family History** | 47 (51%) |

| Antiplatelet Medications | |

| Aspirin | 92 (100%) |

| Clopidogrel | 27 (29%) |

Documented medical history of Hypertension and Dyslipidemia

Family History of early myocardial infarction

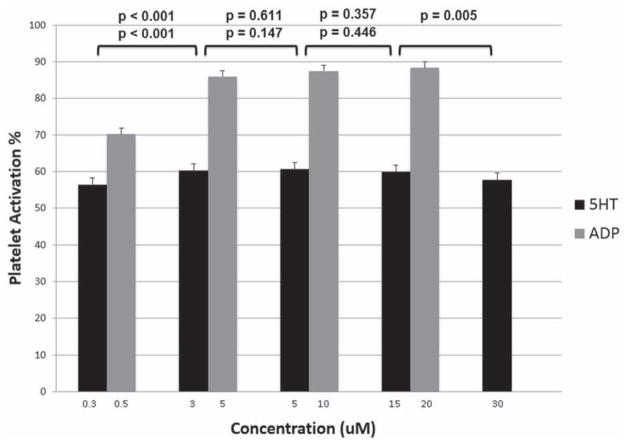

When platelets were activated with non-augmented direct serotonin, there was an initial increase from serotonin concentration 0.3 to 3 μM (56.5% ± 1.9 vs 60.2% ± 1.9, mean percent activation ± standard error, p<0.001) with a plateau of platelet activation level from concentrations 3 to 15 μM (60.2% ± 1.9 vs 60.6% ± 1.9 vs 59.9% ± 1.9). However, upon addition of the highest concentration of 5-HT (30μM), platelet activation was significantly lower when compared to the second to highest concentration of serotonin (15 μM) detected by flow cytometry (57.8% ± 1.8 vs 59.9% ± 1.8, p= 0.005). The peak platelet activation was seen at the 5-HT concentration of 5 μM. This is in contrast to the platelet activation that was seen with ADP. Platelet activation in response to ADP showed an initial increase from the lowest to next concentration, then a subsequent plateau at the higher ADP concentrations from 5 μM to 20 μM without evidence of lower platelet activation at the maximum concentration of ADP (20 μM) as seen with 5-HT. Platelet activation at the highest concentration of ADP (20 μM) was not significantly different when compared to the second to highest concentration of ADP (10 μM) (88.4% ± 1.5 vs 87.7% ± 1.5, p= 0.45). See Figure 1. A mixed regression model showed no significant difference for gender (p=0.63 for 5-HT, p=0.63 for ADP) or race (p=0.82 for 5-HT, p=0.49 for ADP). After adjustment for Clopidogrel use we found that direct serotonin stimulated platelet activation was not decreased in those patients on Clopidogrel therapy compared to those not on Clopidogrel(p=0.43). For ADP-induced platelet activation, there was an overall significant decrease in those patients on Clopidogrel therapy compared to those not on Clopidogrel (p<0.001). Although when directly comparing the Clopidogrel groups at each of the ADP levels, only the lowest concentration of 5 μM was statistically significant. The others mean activations were lower for those patients on Clopidogrel therapy compared to those not on Clopidogrel, but were not statistically significant. See Table 2.

FIGURE 1.

Mean percent of platelet activation in response to increasing 5HT and ADP concentrations. 5HT = serotonin; ADP = adenosine diphosphate.

TABLE 2.

Mean Platelet aggregation and activation in patients on (+) and off Clopidogrel (−)

| Clopidogrel (+) | Clopidogrel (−) | p-value | |

|---|---|---|---|

| 5HT Aggregation | |||

| 0.3 | 31.5 | 32.6 | 0.79 |

| 3.0 | 51.1 | 53.1 | 0.39 |

| 5.0 | 51.3 | 55.4 | 0.08 |

| 15 | 53.0 | 57.6 | 0.05 |

| 30 | 52.5 | 56.4 | 0.10 |

| 5HT Activation | |||

| 0.3 | 53.0 | 59.2 | 0.13 |

| 3.0 | 62.4 | 63.0 | 0.72 |

| 5.0 | 62.3 | 63.6 | 0.44 |

| 15 | 61.5 | 63.0 | 0.39 |

| 30 | 60.7 | 60.3 | 0.81 |

| ADP Aggregation | |||

| 0.5 | 5.0 | 13.5 | <0.01 |

| 5.0 | 41.9 | 66.2 | <0.01 |

| 10 | 46.1 | 70.3 | <0.01 |

| 20 | 52.6 | 74.1 | <0.01 |

| ADP Activation | |||

| 0.5 | 59.4 | 74.3 | <0.01 |

| 5.0 | 75.9 | 90.5 | 0.81 |

| 10 | 78.7 | 91.4 | 0.28 |

| 20 | 80.7 | 91.7 | 0.06 |

5HT = serotonin; ADP = adenosine diphosphate

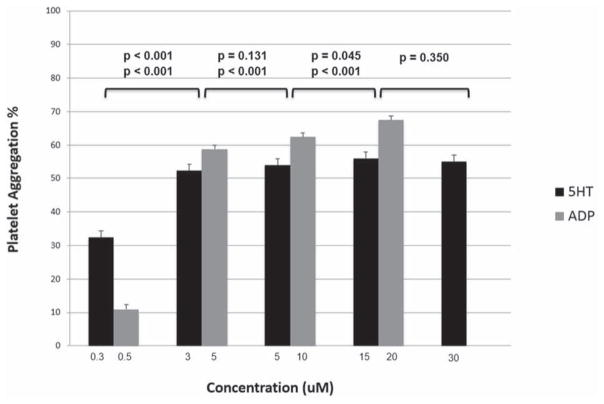

Platelet aggregation when stimulated with epinephrine-augmented 5-HT increased from lowest concentration of 0.3 μM to the next of 3 μM (32.5% ± 1.9 vs 52.3% ± 1.9, p<0.001), and again from 5-HT concentrations of 5 μM to 15 μM (53.9% ± 1.9 vs 56.1% ± 1.9, p=0.045). No difference in aggregation level was seen from concentrations 3 μM to 5 μM (52.3% ± 1.9 vs 53.9% ± 1.9, p=0.131), and from 15 μM to 30 μM (56% ± 1.9 vs 55% ± 1.9, p=0.35). Of note, the mean aggregation level was lower at the highest 5-HT concentration of 30 μM compared to the peak level at the 5-HT concentration of 15 μM. When platelets were stimulated with ADP there was a continued increase in aggregation level with each increasing concentration of ADP (11.0% ± 1.2 vs 58.8% ± 1.2 vs 62.4% ± 1.2 vs 67.5% ± 1.2, p <0.001 between each concentration). See Figure 2. A mixed regression model showed no significant difference for gender (p=0.13 for 5-HT, p=0.90 for ADP) or race (p=0.04 for 5-HT, p=0.49 for ADP). After adjustment for Clopidogrel use we found that epinephrine-augmented serotonin platelet aggregation was not decreased in those patients on Clopidogrel therapy compared to those patients not on Clopidogrel at any of the 5-HT concentration(p=0.26 in linear regression model). However, for ADP-induced platelet aggregation, there was a significant decrease in those patients on Clopidogrel therapy compared to those not on Clopidogrel (p<0.001). See Table 2.

FIGURE 2.

Mean percent of platelet aggregation in response to increasing concentrations of 5HT and ADP. Abbreviations as in Figure 1.

Discussion

Our study demonstrated unique patterns of platelet activation to direct serotonin challenge in patients with stable coronary artery disease. Initial concentrations of serotonin caused increased platelet activation however, when platelets were stimulated directly with high concentrations of 5-HT at 30μM, there was a significant decrease in platelet activation after the peak level at 5-HT concentration of 15μM. This is in contrast to ADP stimulated platelets that show increased platelet aggregation and activation with increasing concentrations of ADP8. To our knowledge, no other studies have shown this effect. The cause of this phenomenon is unclear. One possible explanation would be a response to over-saturation of platelets with 5-HT, which may cause a negative feedback mechanism with decreased activity of the 5-HT transporter (SERT), which ultimately may lead to decreased platelet activation and aggregation. This phenomenon has been demonstrated in mice9. Ziu and colleagues examined in vitro and in vivo platelet function following a 24 hour elevation of serotonin infusion in mice. They found an initial dose-dependent enhanced 5-HT uptake rate in platelets leading to increased platelet activation which was then followed by a loss of SERT on the platelet plasma membrane and an attenuation of 5-HT uptake. Specifically they found that that SERT expression was reduced by 42% on the platelet plasma membrane of the 5-HT-infused animals which correlated with a 61% lower 5-HT uptake rate in platelets from 5-HT versus saline-infused mice.

We did not find a corresponding reduction in platelet aggregation at maximal serotonin concentration. However the key difference in the platelet activation and aggregation measurements was the use of epinephrine for augmentation of the serotonin effects during aggregation experiments only. We believe that the effects of the epinephrine likely masked the serotonin effects and recruited additional receptors leading to aggregation such that the peak effect of the serotonin phenomenon was not able to be observed during platelet aggregation when additional non-serotonin receptors are recruited.

In addition to this unique pattern of activation, we found that Clopidogrel therapy, a mainstay in treatment of ACS, does not decrease either direct serotonin platelet activation or epinephrine augmented serotonin platelet aggregation, unlike its significant reduction of ADP-induced platelet activation and aggregation. These results may suggest an alternative potential pathway to target in patients with depression, who have enhanced platelet reactivity to 5-HT, and in patients who are low-responders to Clopidogrel. Clopidogrel low-responders have been shown to have improved platelet inhibition with serotonin receptor antagonism10. This has led to the theory of triple therapy of a serotonin antagonist in addition to the aspirin and clopidogrel regimen, especially in those patients with hypo-responsiveness to clopidogrel. These studies including our current results suggest that inhibiting the serotonin pathway may be a key mechanism in treating CAD in patients with depression. Serotonin receptor and transporter genetic polymorphisms may contribute to the further understanding of platelet serotonin signaling11.

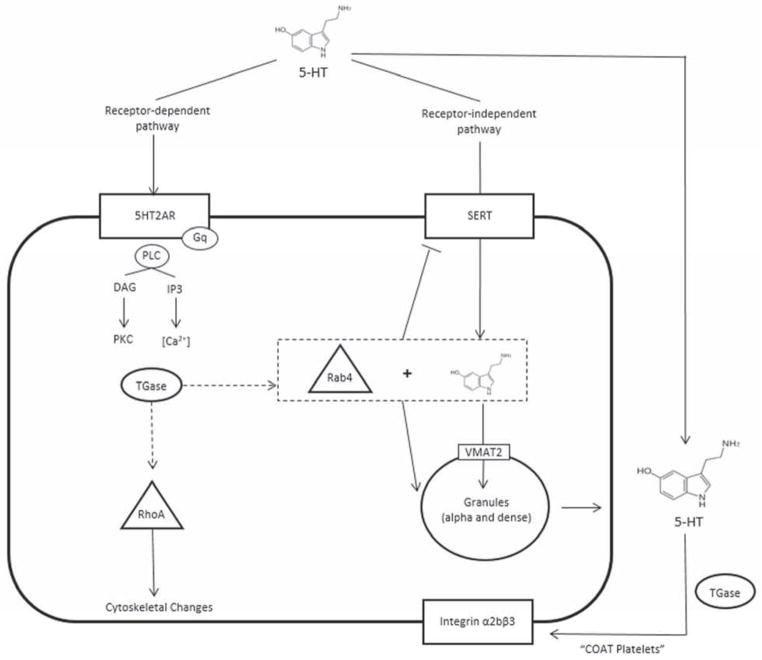

Serotonin plays a key role in vascular tone and platelet function. Elevated levels of plasma 5-HT has been observed in patients with a number of cardiovascular diseases12–17. The importance of serotonin to clinical disease is clear; however the exact complex role of 5-HT is incompletely understood. There seems to be two main pathways of action: serotonin receptor-dependent and –independent. In the receptor-dependent pathway, extracellular 5-HT binds to the 5HT2A receptor on the platelet surface, which initiates a G-protein signaling pathway that ultimately increases intracellular calcium17. This leads to the release of procoagulant molecules, including 5-HT. The procoagulants through a transglutaminase (TGase)-mediated process form coated platelets (COAT), which are enriched in membrane-bound procoagulant proteins18, 19. This pathway has been shown in studies to be important with the use of 5HT2A specific receptor antagonist such as Ketanserin, which have reduced platelet aggregation. The receptor-independent pathway uses the saturable SERT to transport 5-HT intracellularly, where it is taken up into the dense granules. In addition to the sequestration, cytoplasmic 5-HT is activated via TGase to GTP-bound active 5-HT molecules20. This leads to stimulation of granule release. Another downstream effect of the GTP-bound active 5-HT is with Rab4-GTP, a protein with a key role in vesicular transport, where SERT is down regulated and leads to decreased serotonin uptake21. This down regulation may be a potential reason for the decreased activation seen with 5-HT at the highest concentration in our study. See Figure 3.

FIGURE 3.

Serotonin pathway in platelets. 5-HT = serotonin; 5HT2AR = serotonin receptor type 2A; SERT = serotonin transporter; PLC = phospholipase C; DAG = diacyl glycerol; IP3 = inositol 1,4,5-triphosphate; PKC = protein kinase C; Tgase = transglutaminase; VMAT = vesicular monoamine transporter 2; COAT = collagen and thrombin activated.

There were several limitations to our study. As mentioned earlier, epinephrine-augmentation for 5-HT platelet aggregation may have possibly masked results. In addition, higher 5-HT levels were not used to possibly show further decrease in platelet activation. Platelet function was studied in-vitro without correlation to clinical outcomes or depression assessment which is planned for future studies. The implication of a likely mechanism in this complex process of thrombosis and platelet serotonin response is still not perfectly clear, and will require further investigation.

Acknowledgments

This study was funded by the US National Heart, Lung, and Blood Institute (RO1 HL096694) and in part by the NIH CTSA grant UL1 RR 025005.

Footnotes

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

References

- 1.Maree AO, Fitzgerald DJ. Aspirin and coronary artery disease. Thromb Haemost. 2004;92:1175–1181. doi: 10.1160/TH04-02-0127. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Reid GJ, Seidelin PH, Kop WJ, Irvine MJ, Strauss BH, Nolan RP, Lau HK, Yeo EL. Mental-stress-induced platelet activation among patients with coronary artery disease. Psychosom Med. 2009;71:438–445. doi: 10.1097/PSY.0b013e31819cc751. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.McCaffery JM, Frasure-Smith N, Dube MP, Theroux P, Rouleau GA, Duan Q, Lesperance F. Common genetic vulnerability to depressive symptoms and coronary artery disease: a review and development of candidate genes related to inflammation and serotonin. Psychosom Med. 2006;68:187–200. doi: 10.1097/01.psy.0000208630.79271.a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Shimbo D, Child J, Davidson K, Geer E, Osende JI, Reddy S, Dronge A, Fuster V, Badimon JJ. Exaggerated serotonin-mediated platelet reactivity as a possible link in depression and acute coronary syndromes. Am J Cardiol. 2002;89:331–333. doi: 10.1016/s0002-9149(01)02236-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Zafar MU, Paz-Yepes M, Shimbo D, Vilahur G, Burg MM, Chaplin W, Fuster V, Davidson KW, Badimon JJ. Anxiety is a better predictor of platelet reactivity in coronary artery disease patients than depression. Eur Heart J. 2010;31:1573–1582. doi: 10.1093/eurheartj/ehp602. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Williams MS, Rogers HL, Wang NY, Ziegelstein RC. Do Platelet-Derived Microparticles Play a Role in Depression, Inflammation, and Acute Coronary Syndrome? Psychosomatics. 2013 doi: 10.1016/j.psym.2013.09.004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Li N, Wallen NH, Ladjevardi M, Hjemdahl P. Effects of serotonin on platelet activation in whole blood. Blood Coagul Fibrinolysis. 1997;8:517–523. doi: 10.1097/00001721-199711000-00006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Atiemo AD, Ng’Alla LS, Vaidya D, Williams MS. Abnormal PFA-100 closure time is associated with increased platelet aggregation in patients presenting with chest pain. J Thromb Thrombolysis. 2008;25:173–178. doi: 10.1007/s11239-007-0045-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Ziu E, Mercado CP, Li Y, Singh P, Ahmed BA, Freyaldenhoven S, Lensing S, Ware J, Kilic F. Down-regulation of the serotonin transporter in hyperreactive platelets counteracts the pro-thrombotic effect of serotonin. J Mol Cell Cardiol. 2012;52:1112–1121. doi: 10.1016/j.yjmcc.2012.02.004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Duerschmied D, Ahrens I, Mauler M, Brandt C, Weidner S, Bode C, Moser M. Serotonin antagonism improves platelet inhibition in clopidogrel low-responders after coronary stent placement: an in vitro pilot study. PLoS One. 7:e32656. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0032656. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Williams MS. Platelets and depression in cardiovascular disease: A brief review of the current literature. World J Psychiatry. 2:114–123. doi: 10.5498/wjp.v2.i6.114. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Golino P, Maseri A. Serotonin receptors in human coronary arteries. Circulation. 1994;90:1573–1575. doi: 10.1161/01.cir.90.3.1573. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Vikenes K, Farstad M, Nordrehaug JE. Serotonin is associated with coronary artery disease and cardiac events. Circulation. 1999;100:483–489. doi: 10.1161/01.cir.100.5.483. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Kaumann AJ, Levy FO. 5-hydroxytryptamine receptors in the human cardiovascular system. Pharmacol Ther. 2006;111:674–706. doi: 10.1016/j.pharmthera.2005.12.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Yamada S, Akita H, Kanazawa K, Ishida T, Hirata K, Ito K, Kawashima S, Yokoyama M. T102C polymorphism of the serotonin (5-HT) 2A receptor gene in patients with non-fatal acute myocardial infarction. Atherosclerosis. 2000;150:143–148. doi: 10.1016/s0021-9150(99)00356-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Cote F, Thevenot E, Fligny C, Fromes Y, Darmon M, Ripoche MA, Bayard E, Hanoun N, Saurini F, Lechat P, Dandolo L, Hamon M, Mallet J, Vodjdani G. Disruption of the nonneuronal tph1 gene demonstrates the importance of peripheral serotonin in cardiac function. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2003;100:13525–13530. doi: 10.1073/pnas.2233056100. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Przyklenk K, Frelinger AL, 3rd, Linden MD, Whittaker P, Li Y, Barnard MR, Adams J, Morgan M, Al-Shamma H, Michelson AD. Targeted inhibition of the serotonin 5HT2A receptor improves coronary patency in an in vivo model of recurrent thrombosis. J Thromb Haemost. 8:331–340. doi: 10.1111/j.1538-7836.2009.03693.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Dale GL, Friese P, Batar P, Hamilton SF, Reed GL, Jackson KW, Clemetson KJ, Alberio L. Stimulated platelets use serotonin to enhance their retention of procoagulant proteins on the cell surface. Nature. 2002;415:175–179. doi: 10.1038/415175a. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Dale GL. Coated-platelets: an emerging component of the procoagulant response. J Thromb Haemost. 2005;3:2185–2192. doi: 10.1111/j.1538-7836.2005.01274.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Walther DJ, Peter JU, Winter S, Holtje M, Paulmann N, Grohmann M, Vowinckel J, Alamo-Bethencourt V, Wilhelm CS, Ahnert-Hilger G, Bader M. Serotonylation of small GTPases is a signal transduction pathway that triggers platelet alpha-granule release. Cell. 2003;115:851–862. doi: 10.1016/s0092-8674(03)01014-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Ahmed BA, Jeffus BC, Bukhari SI, Harney JT, Unal R, Lupashin VV, van der Sluijs P, Kilic F. Serotonin transamidates Rab4 and facilitates its binding to the C terminus of serotonin transporter. J Biol Chem. 2008;283:9388–9398. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M706367200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]