Abstract

Tumor choline metabolites have potential for use as diagnostic indicators of breast cancer progression and can be non-invasively monitored in vivo by magnetic resonance spectroscopy. Both a 31P MR visible phosphomonoester peak (~3.9 ppm) and a total choline metabolite peak (~3.2 ppm) detected by 1H MRS are elevated in human breast tumors. As determined by tumor extract studies, the principle diagnostic component of these peaks is phosphocholine (PCho), the biosynthetic precursor to the membrane phospholipid, phosphatidylcholine (PtdCho). In extracts of human breast cells, PCho and the PtdCho breakdown product, glycerophosphocholine, are incrementally increased in cell lines of increasing metastatic potential. The ability to resolve and quantify PCho in vivo would improve the precision of this putative diagnostic tool. Additionally, determining the biochemical mechanisms underlying these metabolic perturbations will improve the understanding of metastatic cancer and could suggest potential molecular targets for drug development. Reported herein is the in vivo resolution and quantification of PCho in a breast cancer xenograft model in SCID mice via image-guided 31P MR spectroscopy, localized to small voxels. Also reported is the quantification of cytosolic and lipid metabolites in breast cancer cells of increasing cancer progression, and the identification of metabolites that differ amongst cell lines by degree of cancer aggressiveness. These metabolic differences are correlated with differences in expression of genes of the choline metabolic pathway. Gene expression changes following taxane therapy are also correlated with previously reported changes in choline metabolites following the same therapy in the same tumor model. Biochemical models explaining the metabolic changes are discussed.

Keywords: Choline, phosphatidylcholine, metabolism, gene expression, breast, cancer

Introduction

Breast cancer is a significant factor in women’s health worldwide. In the US, approximately 212,920 new cases of invasive breast cancer, 61,980 in situ cases and 40,970 deaths were predicted for 2006 (1). Diagnosis and choice of appropriate therapy is complicated by the heterogeneous nature of the disease. Breast cancer is presented in a range of histological types and molecular profiles (2). Seventy percent of cases are classified as infiltrating ductal carcinoma, but there is considerable heterogeneity of gene expression and a range of therapeutic outcomes in these cases. A number of additional classifications exist, each type with a general prognosis but with considerable heterogeneity of therapeutic response.

The most established prognostic markers are involvement of axillary lymph nodes, tumor size and histologic grade. A number of molecular markers are also being investigated for proliferation (Ki-67, PCNA); expression of oncogenes (HER-2, EGF receptor); tumor suppressor activity (p53, nm-23); invasiveness (cathepsin D, plasminogen activator inhibitor and urokinase-plasminogen activator receptor); and angiogenesis (VEGF) (3). DNA arrays have established expression patterns of 70 genes involved in cell cycle regulation, invasion and metastasis, angiogenesis and signal transduction that are highly predictive of poor prognosis in breast cancer (4).

Non-invasive magnetic resonance spectroscopy (MRS) localized to the tumor can also provide useful information about tumor progression and metabolism. MR-visible choline metabolites are elevated in breast cancer (5-8). The 31P MRS visible phosphomonoester (PME) resonance (~3.9 ppm) of breast tumors is elevated relative to normal tissue, yet does not yet accurately differentiate benign from metastatic cancerous lesions (9-13). MRS of tumor extracts have established that the PME signal is a composite resonance, primarily of phosphocholine (PCho), phosphoethanolamine (PEtn) and sugar phosphates (14-16). PCho is implicated as the elevated component of the PME resonance in breast tumors (17,18).

In more recent years, the identification of elevated choline metabolites in vivo by 1H MRS was explored in breast tumors and axillary lymph node metastases (19-26). At lower field strengths, detection of the total choline (tCho) resonance (~3.2 ppm) has distinguished malignant from benign tumors with high specificity and sensitivity (27-29). However, as higher field strengths were used clinically, tCho peak detection limits were lowered, requiring the quantification of relative tCho levels (30). Quantification at low field strength (1.5 T) was subsequently achieved (31). The same group performed a clinical blind study at 4 Tesla demonstrating that when MRS and MRI readings are combined the sensitivity and accuracy of radiological assessments were significantly improved (32).

Studies of tumor extracts have identified individual components of the tCho resonance and PCho is determined to be the most diagnostic component (33). Use of the PME and tCho resonance to stage breast cancer progression is limited by the inability to resolve PCho in vivo. Since PCho appears to be the most diagnostic component, differences in other components of these resonances may dampen the effect. By image localized 31P MR spectroscopy, the resolution and quantification of PCho in small voxels of human breast cancer cell xenografts in SCID mice was recently reported (34).

High resolution NMR studies of breast cancer cell extracts have determined that PCho increases with cancer progression (35-37). PCho is a cytosolic intermediate for the synthesis of the lipid membrane component, phosphatidylcholine (PtdCho). NMR of breast cells is used to study the underlying biochemistry behind these cancer-related differences in choline metabolite levels. Transport of choline into MCF-7 breast cancer cells is 2-fold higher relative to human mammary epithelial cells (HMECs), and conversion of choline (Cho) into PCho by choline kinase is 10-fold higher, but conversion of PCho into PtdCho occurred at a similar rate (38). Glycerophosphocholine (GPC) is a degradation product of PtdCho. GPC is also elevated with breast cancer progression and relative PCho/GPC ratios are reported to increase dramatically in cells during log phase growth (37). Determining the biochemical mechanisms behind these metabolic perturbations will improve the understanding of metastatic breast cancer and may suggest novel molecular targets for drug development.

This communication is a study of the breast cancer metabolome. In particular, choline metabolites are quantified and compared with the choline pathway transcriptome for the same tumors and cells. Quantification of PCho and GPC in vivo in tumorigenic (MCF-7/S), doxorubicin resistant (MCF-7/D40) (39) and metastatic (MDA-mb-231) breast tumor xenografts is reported. Other choline compounds are quantified from tumor extracts. Also reported are the relative concentrations of lipid and cytosolic metabolites in breast cells of increasing cancer progression (normal MCF-10A, tumorigenic MCF-7 and metastatic MDA-mb-231) (40) and differences identified in choline metabolites and other metabolites varying amongst these cells. These results are correlated with quantification of mRNA expression of genes in the choline pathway. Alterations in gene expression are also correlated with changes in choline metabolites in response to therapy (34). These data suggest that a combination of anabolic and catabolic perturbations in PtdCho metabolism contribute to the alterations in choline metabolism observed with cancer progression and response to therapy.

Materials and Methods

Tumor Model

As a model for tumor therapeutic response, human tumor xenografts have been grown in SCID mice and effectively treated (41-43). In the context of therapeutic response, diffusion MRI and spectroscopy results for the animals discussed in this communication have been previously reported (34,44). Therefore methods will be presented in brief. MCF-7/S (Arizona Cancer Center Cell Culture Shared Services, Tucson, AZ), MCF-7/D40 (Arizona Cancer Center Experimental Mouse Shared Services) and MDA-mb-231 (American Type Culture Collection, Rockville, MD) human breast cancer cells were grown in DMEM-F12 media (Sigma, St. Louis, MO) supplemented with 10% FBS (Omega Scientific, Inc., Tarzana, CA), detached using trypsin (GIBCO/Invitrogen life technologies, San Diego, CA) or scraping, and placed in a 1:1 suspension of Hank’s buffered saline (Sigma) and matrigel (Becton Dickinson Labware, Bedford, MA). Cells (1 to 2 × 107) were injected into the mammary fat pad of 5 to 7 week old female SCID mice (Arizona Cancer Center Experimental Mouse Shared Services). Xenografts were allowed to grow into tumors.

In vivo localized 31P MR spectroscopy

Our method for in vivo image-localized spectroscopy has previously been reported in detail (34). Briefly, image-guided ISIS (45) or OSIRIS (46) localized spectroscopy was performed using quantitative acquisition parameters, at a field-strength of 81.15 MHz, spectral width of 8013 Hz, acquisition size of 4096 data points, TR of 10 s, either 23 (184/8) averages for an acquisition time of 1/2 h or 46 (368/8) averages for an acquisition time of 1 h, a secant hyperbolic inversion pulse, an adiabatic fast passage excitation pulse, a Hermitian refocusing pulse, and a dwell time of 62.4 μsec were used. Localized autoshimming on the water resonance was accomplished using a PRESS sequence. Voxel size was variable (0.245 to 1.450 mL) and set within the boundaries of the tumor. Mean voxel volume was 831 ± 62 μL for MCF-7 tumors, and 436 ± 7 μL for MDA-mb-231 tumors. Spectral processing included an exponential line broadening factor of -30 and a Gaussian factor of 0.06, manual phasing and baseline correction, and calibration of the α-NTP peak was (-10.05 ppm). Peak areas were determined using a Levenberg-Marquardt deconvolution routine. Individual peak areas were normalized to the total phosphate signal.

Cell Culture

MCF-10A cells were obtained from the Michigan Cancer Foundation (now Karmanos Cancer Institute, Detroit, MI), MCF-7 cells were obtained from the Arizona Cancer Center cell culture shared service (Tucson, AZ) and MDA-mb-231 cells were obtained from the American Type Culture Collection (Rockville, MD). All cell lines have been maintained at low passage number. Commercial sources of cell growth medium are as follows: EGF (Upstate Biotechnology, Lake Placid, NY), Fetal bovine serum (FBS) (Omega Scientific, Inc., Tarzana, CA), Trypsin (Invitrogen life technologies, San Diego, CA). All other media, chemicals and reagents were purchased from Sigma, St. Louis, MO) unless otherwise stated. Cells were grown in DMEM-F12 media with 5 mg/mL insulin. Due to EGF dependence for growth (47), 20 ng/mL EGF was added to MCF-10A media. Media contained 10% FBS of the same lot.

Dual-Phase Tumor and Cell Extract

Tumor metabolites were extracted via a dual-phase extraction (DPE) method previously described by Katz-Brull, et al. (48). Frozen tumors were placed in 10 mL ice-cold 0.4 mM phenylphosphonic acid in methanol for 1 h, after which the tumor tissue was homogenized to an even consistency using a Dremel hand-held homogenizer [Racine, WI] while maintaining on ice. Equal volumes (10 mL) of ice-cold chloroform and distilled and deionized water were sequentially added to the homogenate followed by vigorous vortex mixing after each addition. The mixture was left overnight in the -20°C freezer allowing phase separation.

Human breast cancer cells representing a range of cancer progression were used (40). Prior to treatment, MCF-10A (normal), MCF-7 (tumorigenic) and MDA-mb-231 (tumorigenic and metastatic) cells were grown to steady-state (confluence + 1 d) in order to best model a tumor. For metabolite comparison amongst cell lines, media was replaced and cells were allowed to grow for an additional 24 h. Replaced media contained a dilute concentration of drug carrier which we have previously shown to have no effect on cell viability or growth (40). Dual-phase cell extracts were performed as described by Tyagi, et al. (49). Four extracts per treatment group. Immediately following three initial 0.9% saline washes at room temperature, plates were placed on ice and covered during the 10 to 20 minute incubation in ice-cold methanol. Cells in methanol were scraped from each plate and ice-cold water and chloroform were added in succession with vortexing between additions. Equal volumes of methanol, water and chloroform were used (1:1:1). Extracts were kept overnight at 4°C for phase separation.

Following phase separation of both tumor and cell extracts, the upper methanol-water and the lower chloroform phases were transferred into separate containers. Methanol was reduced from the aqueous phase by blowing nitrogen gas over the mixture while on ice and samples were frozen in liquid nitrogen and lyophilized at -80°C. After lyophilization, water-soluble metabolites were resuspended in 1 mL of 2H2O. Chelex (~5 mg) was added to the resuspendate and removed by centrifuge. For 1H spectroscopy, 400 μL of resuspendate were added to a 5 mm NMR tube (Wilmad, Buena, NJ). For 31P spectroscopy, EDTA (pH 8) was added to reach a final concentration of 10 mM. Tumor samples were then diluted 1:1 in tricene buffer (pH 8.1) bringing the sample pH to within the range of pH 7.8 to 8.0. Cell extracts were already in the appropriate pH range for resolution of peaks (~8.5) so adjustment was not necessary. Protein at the interface between the aqueous and lipid phases was air dried, resuspended in 0.1 N NaOH, let stand for 30 minutes, boiled 5 minutes and neutralized in HCl. Protein content was determined via Bradford assay using BSA standards (50). Before resuspending, samples were maintained at -20°C. Resuspended samples were maintained on ice or at 4°C.

High-Resolution NMR Spectroscopy

High-resolution spectroscopy of extracts was performed on a Bruker-Biospin DRX-500 NMR spectrometer [Billerica, MA]. Phosphorous spectroscopy of the aqueous and lipid phases was performed using a Bruker-Biospin 5 mm multinuclear probe at a field strength of 202 MHz with an acquisition size of 65,000 data points, a sweep width of 50 ppm, TR of 12 s, with 5000 scans for aqueous extracts and 1200 scans for lipid extracts. Linewidths were < 1 Hz for aqueous extracts and < 2 Hz for lipid extracts. Processing included zero filling and a line broadening factor of 1 Hz was applied. As a standard, a 10 mM 1-aminopropylphosphonic acid (1-APP) in 2H2O was used. Proton spectroscopy was performed using a Bruker-Biospin 5 mm triple-resonance triple-gradient probe at a field strength of 500 MHz with an acquisition size of 32,000 data points, a sweep width of 20 ppm, TR of 3.6 s, with 256 scans. Linewidths were ~ 3 Hz. Processing included zero filling and a line broadening factor of 0.3 Hz was applied. As a standard, 0.5 mM 3-(trimethylsilyl) tetradeutero sodium propionate (TSP) in 2H2O was used. 90° pulse angles were applied for quantitative results. T1 tests determined that acquisition conditions were quantitative (5*T1) for all resonances analyzed except for inorganic phosphate (Pi) during 31P spectroscopy. Pi was determined to be 81.9% of the fully relaxed signal, and the appropriate correction was applied.

Tumor extract and lipid phase cell extract standards were placed into a Wilmad 5 mm O.D. stem coaxial insert [Buena, NJ] and inserted into the sample NMR tube. For aqueous phase of cell extracts, standards were sealed in a capillary tube and placed in the NMR tube. The ratio of sample to standard was determined from manufacturer’s specifications of the NMR tube and insert, or from a cross-section image of the capillary tube by which the inside and outside diameters were determined. For cell extracts, initial spectra were acquired without the standard. A second spectrum was acquired with the standard without spinning. Since the initial spectra were of higher resolution due to the spinning, a ratio of the standard peak and the largest metabolite peak was determined from the standard spectra and applied to all peaks of the higher resolution spectra.

Peak assignments were made by addition of known metabolites and from the literature (51). Peak areas were determined using a deconvolution routine based on the Levenberg-Marquardt algorithm. The signal to noise ratio was used to determine values for undetectable peaks with the ratio being defined as: largest peak intensity/(2*noise intensity). Undetectable peaks were given the value of 2X noise, which is the largest peak area divided by the signal to noise ratio. The deconvolution linefit was assessed for each peak. Peaks with poor linefits due to very low signal-to-noise ratio were removed from the analysis. All peak areas were normalized to the total aqueous phosphorous signal for a given extract. Cho peak areas were normalized by applying the Cho/PCho ratio from the 1H spectra to the PCho/total aqueous phosphorous ratio from the 31P spectra of the same extract. Lipid peak areas were normalized by applying the ratio of lipid peak concentration (nmol*mg protein-1)/ PCho concentration (nmol*mg protein-1) to the PCho/total aqueous phosphorous ratio from the 31P spectra of the same extract. Excel spreadsheet (Microsoft, Seattle, WA) was used to manually align acceptable signals within spectra from each cell line (n = 4). Alignments were then made of signals amongst all cell lines. Mean peak area and standard error of the mean (sem) were calculated for each peak by cell line. Significant differences in mean peak areas amongst cell lines were determined by t-test.

RNA extraction

For comparison of gene expression amongst cell lines, cells were grown one day past confluence, media was then replaced with media containing dilute drug carrier and incubated an additional 24 h before RNA extraction. For gene expression response to therapy, replacement media contained 10 nM docetaxel or drug-carrier only as a no drug control, and cells were incubated an additional 48 h before RNA extraction. RNA was extracted using the GenElute™ Mammalian Total RNA Miniprep kit (Sigma, St. Louis, MO). To remove genomic DNA contamination, RNA extracts were treated with DNAse using the DNA-free™ kit (Ambion, Austin, TX). RNA purity and concentration were determined by A260/A280 ratio.

Real-time RT-PCR

Primer sets were designed by us to generate cDNA and perform RT-PCR from β-actin, CTL1, CK1, CHKL, CTP1α, CTP1β, CPT, PLD1α, PLD2α and PLD2β mRNA. Primers were synthesized by Invitrogen life technologies (San Diego, CA). PCR conditions were optimized for each primer set by varying annealing temperature and, if necessary, Mg++ concentration so that maximum yield without spurious priming was achieved. RNA extracts from multiple cell lines were used as template RNA during optimization (Table 1).

Table 1.

Optimal PCR conditions per primer set. For the Invitrogen kit, [Mg++] was 1.8 mM in all cases and for the Qiagen Hot Start kit, stock [Mg++] was used.

| Gene | Accession # | Primer | Sequence (5’ → 3’) | Product Length | Annealing T (°C) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

| |||||

| CTL1, var. A | HSA420812 | forward | gtg ctg atg gag ttt gtg g | 107 | 57.8** |

| reverse | aga act tgc tcc cga agc | ||||

|

| |||||

| CK1 | D10704 | forward | aga ggc ggc ctt agc aac a | 76 | 60 |

| reverse | ttc cga ggc tca tca cca a | ||||

|

| |||||

| CHKL | NM_005198 | forward | gct ctc aga gcc aga aaa tgc t | 85 | 60 |

| reverse | tcc caa tgt caa agc ccc tat a | ||||

|

| |||||

| CTP1α | NM_005017 | forward | gtt tat gcc gat gga ata ttt gac t | 71 | 64.8,* 58.8** |

| reverse | aag gtt ctt cgc ttg cat cag | ||||

|

| |||||

| CTP1β | NM_004845 | forward | gcc cac agc ctc gac tga* | 69*, 104** | 60.8,* 59 ** |

| cct ttc caa tga gcc tcc** | |||||

| reverse | ctt gac act ggc agt tgg ttt c* | ||||

| tgg ttt cat cag caa atg g** | |||||

|

| |||||

| CPT | AF195623 | forward | cgc tcg tgc tca tct cct act | 76 | 64.8,* 61.8** |

| reverse | ccc agt gca cat aaa agg tat gtc | ||||

|

| |||||

| PLD1α | NM_002662 | reverse | caa gat agc caa gga caa cc | 94 | 59.2* |

| forward | tgt tcc ttc agt aat gga tgg | ||||

|

| |||||

| PLD2α | NM_002663 | forward | tct gcg gaa gca ctg c | 91 | 64.8,* 61.8** |

| reverse | act gga aga agt cat cac aga tgg | ||||

|

| |||||

| PLD2β | AF038441 | forward | agg cgg gca gtg tga ttc | 123,* 80** | 60.8,* 58.8** |

| reverse | gct cat aga tat tgg cgt tgc tc* | ||||

| act gga aga agt cat cac aga tgg** | |||||

|

| |||||

| β-actin | BC016045 | forward | cgg cat cgt cac caa ctg | 71 | 69.9,* 61.8** |

| reverse | ggc aca cgc agc tca ttg | ||||

Parameters for Invitrogen RT-PCR kit.

Optimal conditions for Qiagen Hot-Start Kit.

Real-time RT-PCR was conducted using a Smart Cycler® (Cephid, Sunnyvale, CA) and, for comparison of gene expression between cell lines, the SuperScript™ One-Step RT-PCR system with Platinum® Taq (Invitrogen life technologies, San Diego, CA) was used. For detection of gene expression response to therapy, the HotStarTaq DNA polymerase kit was used (Qiagen, Valencia, CA). Real-time detection was aquired using a SYBR-green detection format (Molecular Probes, Eugene, OR). Reverse transcriptase (RT) conversion of RNA into cDNA was performed during a 15 min (SuperScript™) or 20 min (HotStarTaq) incubation at 52°C (SuperScript™) or 50°C (HotStarTaq), which was immediately followed by a 15 min incubation at 94°C (SuperScript™) or 95°C (HotStarTaq) to stop the reaction and denature the cDNA. Next, 35 cycles were run with a 94°C melting temperature for 15 s, and a primer-set specific temperature for 60 s (annealing/extension, SuperScript™) or 30 s (annealing, HotStarTaq). HotStarTaq runs had an additional 20 s extension step at 72°C. To control for DNA contamination of the RNA extracts, a no-RT reaction was run for each extract. A no-template reaction was included during each experiment to control for DNA contamination in the reagents. In some cases, amplification of primer-dimers was observed in the no-template control at later cycles. In all cases, amplification of template occurred prior to primer-dimer amplification and primer-dimer amplification was not detected before template fluorescence had reached a maximum limit. Melt curves ranging from 60 to 90°C yielded a single melt-peak for all template reactions and a minimal melt peaks for the no-template control reaction.

Raw mRNA expression values were determined as being 2-CT, where CT is the number of cycles required for the SYBR green I fluorescence to cross the threshold of 30 arbitrary fluorescence units (SuperScript™), or the second derivative of the fluorescence curve (HotStarTaq). Expression of individual genes in the choline metabolism pathway was normalized to β-actin expression. We have previously shown that β-actin expression is reasonably invariable between these breast cancer cell lines (52). Three extracts per cell line were analyzed (n = 3). Repeatablility of measurements by this method is high (Cronbach’s alpha of 0.93) (52), so only one run per primer set per extract was performed. Results are reported as the mean and error is reported as standard error of the mean (sem). In some cases when using SuperScript™, primer-dimer formation was observed in conjunction with mRNAs expressed at very low levels. These transcripts are reported as being expressed at low, unquantifiable levels.

Results

In Vivo and Ex Vivo Quantification of Tumor Choline

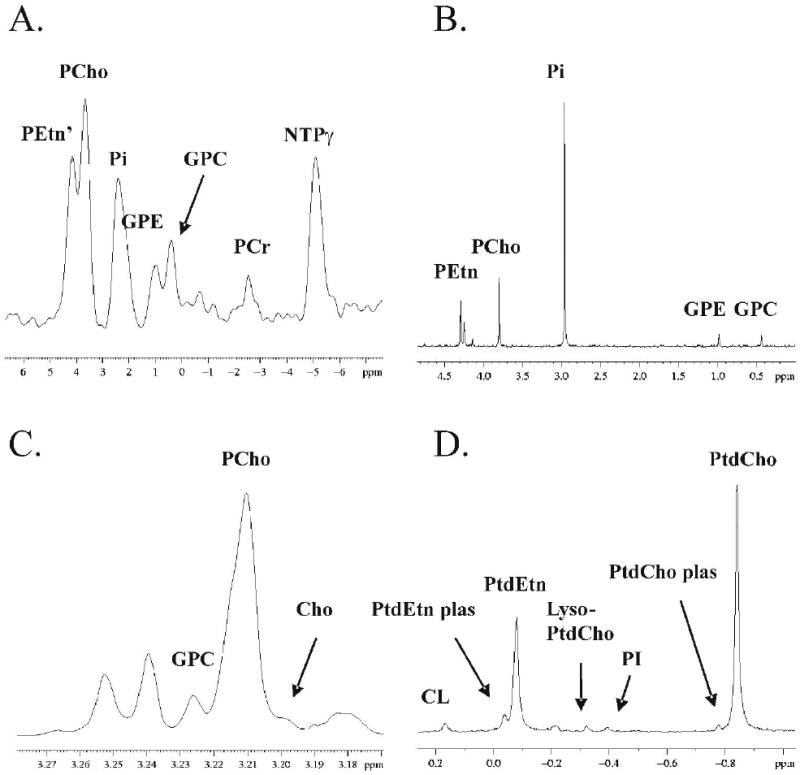

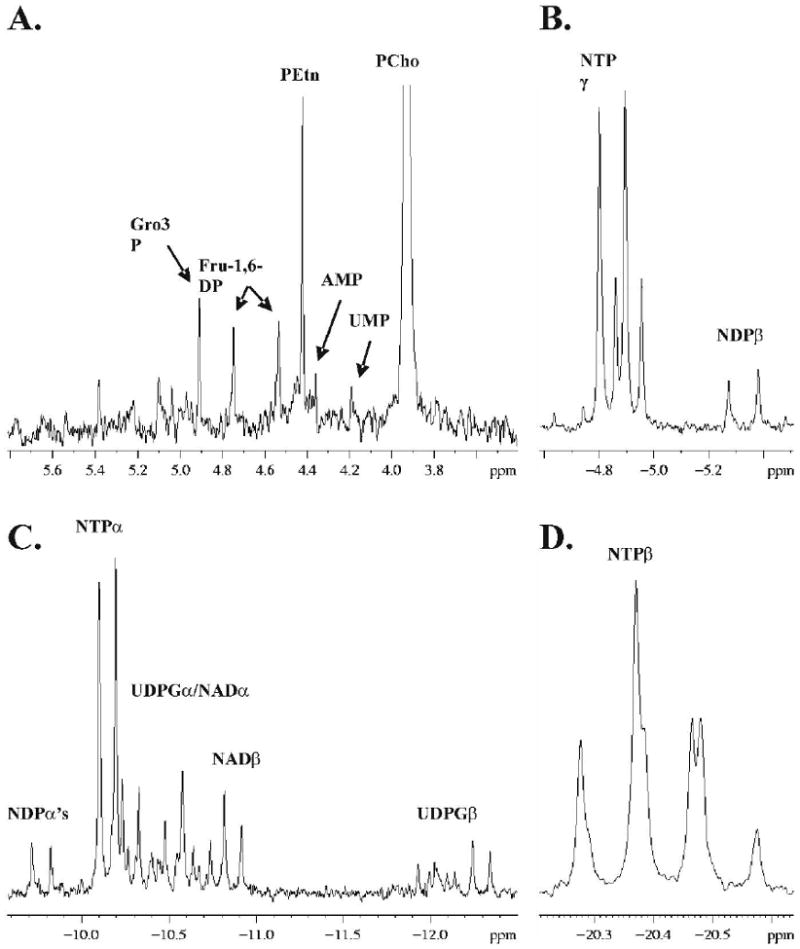

Image-guided, localized 31P MR spectroscopy was performed on MCF-7/S (n = 16), MCF-7/D40 (n = 17) and MDA-mb-231 (n = 23) mammary fat pad xenografts in SCID mice. PCho and GPC peaks were resolved and quantified (Figure 1A). Peak areas normalized to the total tumor phosphate signal were determined for PCho and GPC (Table 2). Ex vivo spectra from corresponding tumors and phantom studies are used to demonstrate that this method is quantitiative (34). Following spectroscopy, tumors were excised and both aqueous and lipid metabolites were extracted using a dual-phase method (48). High resolution NMR spectroscopy was performed on the aqueous and lipid phases of the tumor extracts for peak identification. Peaks representing choline metabolites (PCho, GPC and Cho) were resolved and identified in 31P spectra (Figure 1B) and 1H spectra (1C) of aqueous phase samples. Choline phospholipids and metabolites (PtdCho, PtdCho plasmalogen and Lyso-PtdCho) were identified in 31P spectra of non-aqueous extracts (1D). All tumor choline metabolite peaks were normalized to the total aqueous phosphorous signal and therefore concentrations can be directly compared (Table 1). In vivo PCho was significantly higher in doxorubicin-resistant MCF-7/D40 tumors (p < 0.01 relative to MCF-7/S and p < 0.001 relative to MDA-mb-231 tumors). GPC and the PCho/GPC ratio did not vary significantly between tumor types. Extracts were primarily used for peak identification and hence, the numbers were too low to determine statistical significance ex vivo. However, ex vivo quantifications generally agreed with in vivo. Cho and phospholipid levels were only identifiable ex vivo.

Figure 1.

MR Spectra of MCF-7 tumor metabolites: localized 31P MRS in vivo (A), 31P MRS ex vivo, PME and PDE region (B), 1H MRS ex vivo, choline region (C), and 31P MRS ex vivo, lipid phase. Peak abbreviations are: composite phosphoethanolamine / nucleotide monophosphate / sugar phosphate peak (PEtn’), phosphocholine (PCho), inorganic phosphate (Pi), glycerophosphoethanolamine (GPE), glycerophosphocholine (GPC), phosphocreatine (PCr), nucleotide triphosphate (NTPγ), cardiolipin (CL), phosphatidylethanolamine plasmalogen (PtdEtn plas), phosphatidylethanolamine (PtdEtn), lyso-phosphatidylcholine (Lyso-PtdCho), phosphatidylinositol (PI), phosphatidylcholine plasmalogen (PtdCho plas) and phosphatidylcholine (PtdCho).

Table 2.

Quantifications of tumor choline, in vivo and ex vivo.

| Tumor Type | Number of Spectra (n) | Tumor Choline Metabolites as % total aqueous phosphate signal (± sem) | ||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| PCho, 3.93 | GPC, 0.49 | PCho/GPC | Cho,* 3.2 | PtdCho,** -0.84 | PtdCho plas,** -0.77 | Lyso-PtdCho,** -0.33 | ||||||

| in vivo | ex vivo | in vivo | ex vivo | in vivo | ex vivo | in vivo | ex vivo | ex vivo | ex vivo | ex vivo | ex vivo | |

| MCF-7/S | 16 | 1 | 8.4 (1.0) | 15.0 | 3.6 (0.8) | 6.5 | 2.31 (1.21) | 2.32 | 0.064 | 298 | 2.8 | 7.0 |

| MCF-7/D40 | 17 | 2 | 15.1 (2.0) | 16.9 | 3.1 (0.5) | 3.3 | 10.1 (4.30) | 5.14 | 0.088 | 321 | 13.8 | 13.4 |

| MDA-mb-231 | 23 | 7 (6 lipid) | 7.1 (0.9) | 7.2 (0.7) | 4.6 (1.1) | 4.8 (0.8) | 6.88 (4.39) | 1.84 (0.42) | 0.035 (0.023) | 87.2 (23.0) | 4.0 (0.73) | 2.3 (0.66) |

(Cho/PCho from 1H spectra) * (PCho/tot aqueous PO4 signal from 31P spectra) * 100.

(PtdCho nmol/mg protein from lipid 31P spectra) / (PCho nmol/mg protein from aqueous 31P spectra) * (PCho/total aqueous PO4 signal from 31P spectra) * 100.

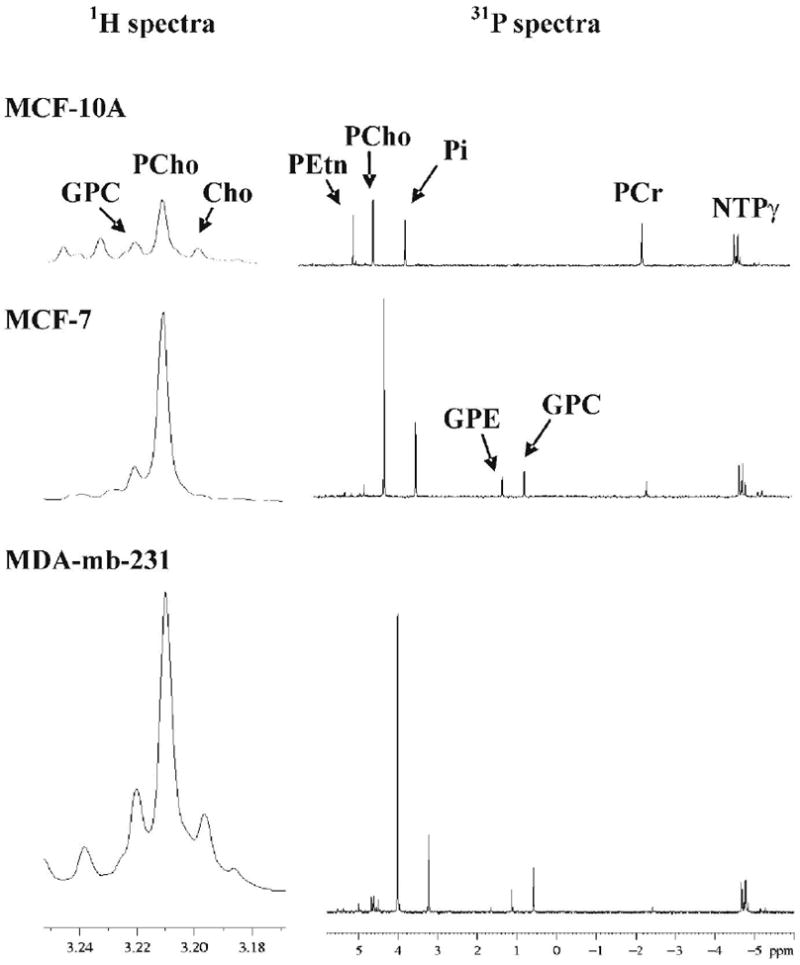

In Vitro Quantification of Choline Metabolites

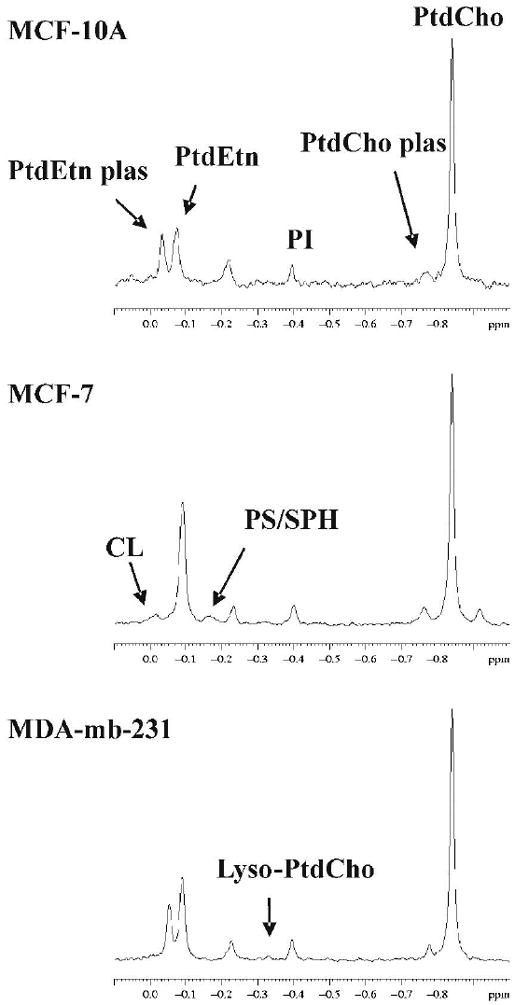

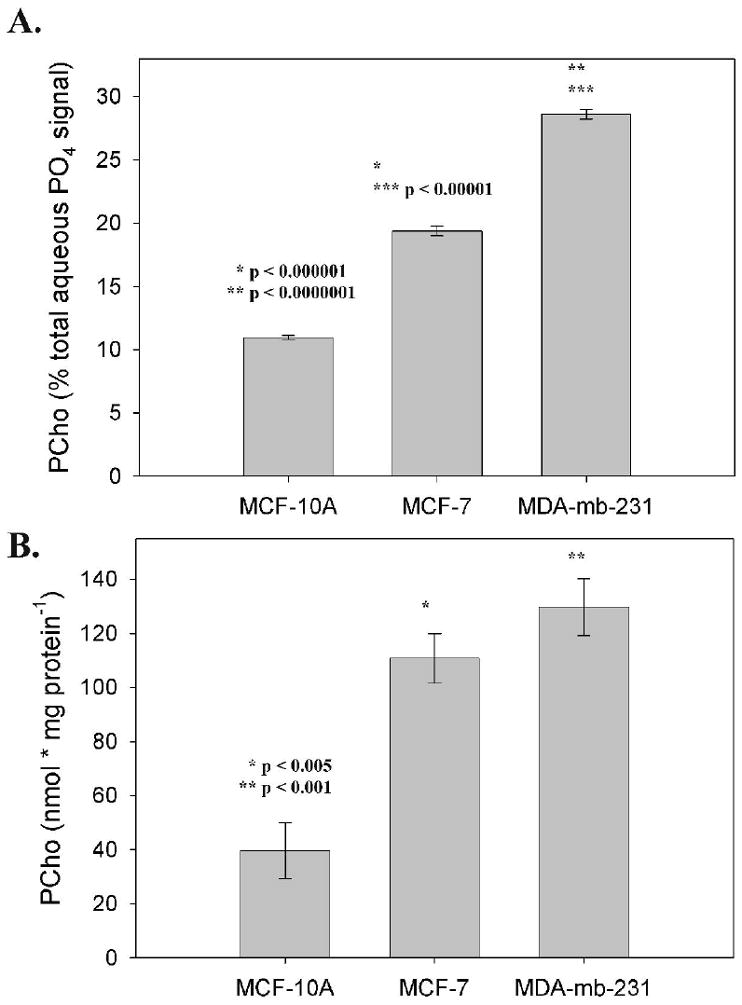

Quantitative extracts were obtained from cultured cells which not only allowed careful control over conditions but also allowed comparison to non-tumorigenic cells, viz. MCF-10A. Both 1H and 31P high resolution MR spectra were acquired from the aqueous phase of MCF-10A, MCF-7 and MDA-mb-231 cell extracts. Cells were grown to steady-state before extraction in order to mimic tumor conditions. Figure 2 shows the choline region of 1H spectra (left column) and the PME and PDE region of 31P spectra (right column). Choline phospholipids were identified in 31P spectra of the lipid phase (Figure 3). Cellular metabolites were normalized as both nmols per mg protein, or as a ratio of metabolite peak area to total aqueous phosphorous peak area. Similar peak profiles were observed by either method of normalization (Figure 4), but the peak area ratios yielded considerably lower error estimates (4A versus 4B), implying a higher degree of precision when quantifying as a percentage of total aqueous phosphorous. Both cytosolic and lipid choline metabolites were quantified as a percentage of total aqueous phosphorous and are reported in table 3.

Figure 2.

Cell extract MR spectra of human breast cancer cell lines of increasing cancer progression: normal MCF-10A cells (top row), tumoigenic MCF-10A cells (middle row), and tumorigenic/metastatic MDA-mb-231 cells (bottom row). 1H spectra of the choline region are in the left column, and 31P spectra of the PME and PDE regions are shown in the right column. Peak abbreviations are: glycerophosphocholine (GPC), phosphocholine (PCho), choline (Cho), phosphoethanolamine (PEtn), inorganic phosphate (Pi), phosphocreatine (PCr), nucleotide triphosphate (NTPγ) and glycerophosphoethanolamine (GPE).

Figure 3.

31P MR spectra of the cell extract lipid phase: MCF-10A (top), MCF-7 (middle) and MDA-mb-231 (bottom). Peak abbreviations are: phosphatidylethanolamine plasmalogen (PtdEtn plas), phosphatidylethanolamine (PtdEtn), phosphatidylinositol (PI), phosphatidylcholine plasmalogen (PtdCho plas), phosphatidylcholine (PtdCho), cardiolipin (CL), phosphatidyl serine/sphingomyelin composite (PS/SPH) and lyso phosphatidylcholine (Lyso-PtdCho).

Figure 4.

A Comparison of normalization methods: Areas of PCho peaks from cell extracts (n = 4) normalized as a percentage of total aqueous phosphate signal (A), and normalized as nmol per mg protein (B).

Table 3.

Quantifications of choline metabolites in vitro.

| Cell Line | Metabolites, ppm, as % total aqueous phosphate signal, n = 4 (± sem) | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| PCho, 3.93 | GPC, 0.49 | PCho/GPC | Cho,* 3.2 | PtdCho,** -0.84 | PtdCho plas,** -0.77 | Lyso-PtdCho,** -0.33 | |

| MCF-10A (normal) | 11.0c,c (0.14) | n.d.c,c | 80.7c.c (2.2) | 2.9c,a (0.27) | 38.70,0 (3.2) | 5.30,0 (2.0) | n.d0,b |

| MCF-7 (tumorigenic) | 19.4c,c (0.38) | 2.6 c,0 (0.020) | 7.3c,0 (0.1) | 0.20c,0 (0.15) | 32.50,0 (9.0) | 2.60,0 (1.2) | 0.180,0 (0.048) |

| MDA-mb-231 (metastatic) | 28.6c,c (0.37) | 3.2 c,0 (0.39) | 9.2c,0 (1.0) | 1.3a,a (0.53) | 50.00,0 (17.0) | 3.90,0 (1.1) | 1.4b,0 (0.15) |

n.d. = not detected at quantifiable levels, significance calculated from 2X noise.

(Cho/PCho from 1H spectra) * (PCho/tot aqueous PO4 signal from 31P spectra) * 100.

(PtdCho nmol/mg protein from lipid 31P spectra) / (PCho nmol/mg protein from aqueous 31P spectra) * (PCho/total aqueous PO4 signal from 31P spectra) * 100.

not significant,

p < 0.05,

p < 0.01,

p < 0.001 vs. other cells in order from top to bottom.

In vitro, PCho increased significantly by degree of cancer progression. The lowest PCho concentrations were observed in normal MCF-10A cells. Tumorigenic MCF-7 cells had significantly higher PCho, and metastatic MDA-mb-231 cells had yet a significantly higher concentration. This same profile is seen for the phosphatidylcholine (PtdCho) degradation product, Lyso-PtdCho. GPC also appears to increase by degree of cancer progression, with MCF-7 and MDA-mb-231 concentrations being significantly higher than in MCF-10A cells, although the differences between the tumorigenic cell lines were not significant. This same effect is seen with the PCho/GPC ratio, where the cancer cell lines do not have significantly different ratios, but both ratios are significantly lower than that of the normal cell line. While PCho levels are higher in cancer cells, the inverse is seen for Cho concentrations. Cho is significantly lower in MCF-7 and MDA-mb-231 cells compared to MCF-10A cells. However, Cho is lowest in MCF-7 cells. There were no significant differences observed in the phospholipid PtdCho or the etherlipid PtdCho plasmalogen concentrations.

In Vitro Quantification of All Metabolites Relative to Cancer Progression

In addition to the choline metabolites, quantifications of all metabolites were compared amongst cell lines to determine significant differences correlated with cancer progression. Four regions of high peak density were identified in 31P MR spectra of the extract aqueous phase (Figure 5): the phosphomonoester (PME)/nucleotide monophosphate (NMP)/sugar phosphate region (5A), the nucleotide triphosphate-γ (NTPγ) region (5B) which also includes nucleotide diphosphate-β resonances (NDPβ), the NTPα region (5C) which also includes NDPα’s, nicotinamide adenine dinucleotides (NADs), and UDPG’s (uridine diphosphate-glucourinate, -glucose, -galactose, -N-acetylglucosamine, -N-acetlygalactosamine), and the NTPβ region (5D). Table 4 is a listing of metabolites which increase with cancer progression. These include the cytosolic phospholipid synthesis and degradation intermediates PCho, Lyso-PtdCho, GPC and GPE, and the phospholipid cardiolipin (diphosphatidylglycerol). Also, some sugar phosphates were elevated including glycerol-3-phosphate and fructose-1,6-diphosphate. A single uridine diphosphate-glucose-β (UDPGlcβ) resonance increased.

Figure 5.

Regions of high signal density from 31P MR spectra of cell extracts (MCF-7 spectrum shown): PME/sugar phosphate region (A), NTPγ region (B), NTPα region (C) and NTPβ region (D). Peak assignments are: glycerol-3-phosphate (Gro3P), fructose-1,6-diphosphate (Fru-1,6-DP), phosphoethanolamine (PEtn), adenosine monophosphate (AMP), uridine monophosphate (UMP), phosphocholine (PCho), nucleotide triphosphate (NTPγ, -α, -β), nucleotide diphosphate (NDPβ, -α), uridine diphosphate-glucourinate, -glucose, -galactose, -N-acetylglucosamine, -N-acetlygalactosamine (UDPGα, -β), and nicotinamide adenine dinucleotide (NADα, -β).

Table 4.

Metabolites increasing with cancer progression.

| Cell Line | Metabolites, ppm, as % total aqueous phosphate signal, n = 4 (± sem) | ||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| incremental increase | generally elevated in cancers | ||||||||||

| Gro3P, 4.91 | F1,6BP, 4.53 | 4.46* | PCho, 3.93 | Lyso-PtdCho,** -0.326 | F1,6BP, 4.75 | GPE, 1.03 | GPC, 0.49 | UTP/CTPγ, -4.93 | UDPGlcβ, -12.09 | CL,** 0.165 | |

| MCF-10A (normal) | n.d.0,b | n.d.c,c | n.d.0,c | 11.0 c,c (0.14) | n.d.c,b | n.d.c,a | 0.19 c,c (0.051) | n.d.c,c | 1.7 b,0 (0.078) | n.d. a,0 | n.d. a,a |

| MCF-7 (tumorigenic) | 0.39 0,a (0.11) | 0.62 c,c (0.072) | 0.18 0,a (0.084) | 19.4 c,c (0.38) | 0.18 c,c (0.048) | 0.39 c,c (0.020) | 2.1 c,a (0.031) | 2.6 c,0 (0.020) | 2.0 b,0 (0.057) | 0.23 a,0 (0.027) | 3.2 a,0 (0.88) |

| MDA-mb-231 (metastatic) | 0.85 b,a (0.14) | 2.0 c,c (0.21) | 0.49 c,a (0.043) | 28.6 c,c (0.37) | 1.4 b,c (0.15) | 0.18 a,c (0.014) | 1.7 c,a (0.11) | 3.2 c,0 (0.39) | 2.3 0,0 (0.90) | 0.20 0,0 (0.076) | 3.7 a,0 (1.3) |

n.d. = not detected at quantifiable levels, significance calculated from 2X noise.

Unidentified sugar phosphate.

(PtdCho nmol/mg protein from lipid 31P spectra) / (PCho nmol/mg protein from aqueous 31P spectra) * (PCho/total aqueous PO4 signal from 31P spectra) * 100.

not significant,

p < 0.05,

p < 0.01,

p < 0.001 vs. other cells in order from top to bottom.

Table 5 includes metabolites which are significantly higher or lower only in the metastatic MDA-mb-231 cell line, although a number of them appear to increase incrementally with cancer progression but are below detection limits needed to verify this statistically. These include a number of unidentified resonances in the sugar phosphate range. Both table 4 and 5 show NTPs which increase or decrease, with the majority being UTP/CTP coresonances. Table 6 is a listing of metabolites that are higher or lower only in MCF-7 cells. Generally, metabolites increased in MCF-7 cells were NDP, NAD, and UDPG resonances. Two lipid resonances were lower in MCF-7 cells, phosphatidylethanolamine (PtdEtn) plasmalogen and an unidentified lipid at -0.225 ppm. A number of metabolites decreased with cancer progression (Table 7). These were Cho, phosphoethanolamine (PEtn), phosphocreatine (PCr), adenosine monophosphate (AMP), NDPα, and various NTPs. Metabolites remaining unchanged with cancer progression (Table 8) included two unidentified sugar-phosphates, inorganic phosphate (Pi), NDPβ, a number of UDPG and NAD resonances, and the majority of phospholipids.

Table 5.

Metabolites differing only in metastatic MDA-mb-231 cells.

| Cell Line | Metabolites, ppm, as % total aqueous phosphate signal, n = 4 (± sem) | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| higher in MDA-mb-231 (peaks ranging from 5.29 to 4.42 are sugar phosphates) | lower in MDA-mb-231 | ||||||

| 5.29 | 4.58 | 4.42 | 1.56* | UTP/CTPγ, -4.84 | NTPα, -10.22 | UTP/CTPβ, -20.54 | |

| MCF-10A (normal) | n.d. 0,a | n.d. 0,b | n.d. 0,b | n.d. 0,c | 1.5 c,a (0.024) | 1.1 0,a (0.07) | 0.985 0,0 (0.13) |

| MCF-7 (tumorigenic) | n.d. 0,a | 0.12 0,b (0.073) | 0.066 0,b (0.014) | n.d. 0,c | 1.8 c,a (0.00007) | 1.3 0,a (0.04) | 1.0 0,a (0.06) |

| MDA-mb-231 (metastatic) | 0.48 a,a (0.12) | 1.4 b,b (0.22) | 0.98 b,b (0.17) | 0.46 c,c (0.036) | 0.81 a,a (0.28) | 0.80 a,a (0.18) | 0.68 0,a (0.071) |

n.d. = not detected at quantifiable levels, significance calculated from 2X noise.

Unidentified.

(PtdCho nmol/mg protein from lipid 31P spectra) / (PCho nmol/mg protein from aqueous 31P spectra) * (PCho/total aqueous PO4 signal from 31P spectra) * 100.

not significant,

p < 0.05,

p < 0.01,

p < 0.001 vs. other cells in order from top to bottom.

Table 6.

Metabolites differing only in tumorigenic MCF-7 cells.

| Cell Line | Metabolites, ppm, as % total aqueous phosphate signal, n = 4 (± sem) | ||||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| higher (peaks ranging from -10.32 to -10.74 are UDPGα’s and NADα’s, peaks ranging from -12.02 to -12.33 are UDPGβ’s) | lower | ||||||||||||||||

| -4.63* | -4.73* | ADP/GDPα, -9.70 | -10.32 | -10.39 | -10.57 | -10.67 | -10.74 | NADβ, -10.81 | NADβ, -10.91 | -11.93 | -12.02 | -12.13 | -12.24 | -12.33 | -0.225** | PtdEtn plas,** -0.040 | |

| MCF-10A (norma l) | 0.14 b,0 (0.00004) | n.d.c,0 | 0.41 a,0 (0.10) | 1.7 b,0 (0.05) | n.d.b,0 | 1.6a,0 (0.26) | n.d. c,0 | 0.38 b,0 (0.12) | 1.1 c,0 (0.07) | 0.72 b,0 (0.17) | n.d. c,0 | 0.43 a,0 (0.070) | n.d. a,0 | 0.25 c,0 (0.11) | n.d. c,0 | 7.8 a,0 (0.70) | 7.9 a,0 (2.6) |

| MCF-7 (tumorigenic) | 0.24 b,0 (0.11) | 0.28 c,a (0.015) | 0.70 a,a (0.041) | 2.0 b,b (0.06) | 0.77 b,b (0.16) | 2.2 a,a (0.15) | 0.44 c,a (0.047) | 0.92 b,a (0.051) | 1.8 c,c (0.01) | 1.2 b,c (0.06) | 0.34 c,a (0.033) | 0.81 a,b (0.083) | 0.31 a,b (0.051) | 0.75 c,b (0.050) | 0.61 c,b (0.023) | 3.8 a,0 (1.1) | 1.2 a,a (1.0) |

| MDA-mb-231 (metastatic) | 0.16 0,0 (0.019) | 0.12 0,a (0.054) | 0.52 0,a (0.030) | 1.4 0,b (0.12) | 0.38 0,b (0.11) | 1.6 0,a (0.13) | 0.16 0,a (0.082) | 0.65 0,a (0.066) | 1.2 0,c (0.03) | 0.76 0,b (0.066) | 0.16 0,a (0.048) | 0.25 0,b (0.10) | 0.082 0,b (0.00008) | 0.40 0,b (0.065) | 0.21 0,b (0.085) | 6.2 0,0 (2.3) | 12.6 0,a (5.7) |

n.d. = not detected at quantifiable levels, significance calculated from 2X noise.

Unidentified.

(PtdCho nmol/mg protein from lipid 31P spectra) / (PCho nmol/mg protein from aqueous 31P spectra) * (PCho/total aqueous PO4 signal from 31P spectra) * 100.

not significant,

p < 0.05,

p < 0.01,

p < 0.001 vs. other cells in order from top to bottom.

Table 7.

Metabolites decreasing with cancer progression.

| Cell Line | Metabolites, ppm, as % total aqueous phosphate signal, n = 4 (± sem) | |||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| PEtn, 4.40 | AMP, 4.33 | PCr, -2.54 | ATP/GTPα, -4.78 | ATP/GTPα, -4.87 | NDPα, -9.81 | ATP/GTPα, -10.09 | NTPα, -10.18 | ATP/GTPβ, -20.24 | NTPβ, -20.34 | NTPβ, -20.44 | Cho,* 3.2 | |

| MCF-10A (normal) | 7.5 c,b (0.26) | 0.74 0,c (0.042) | 8.7 c,c (0.20) | 6.8 c,c (0.06) | 7.0 c,c (0.04) | 0.75 0,a (0.085) | 6.8 c,c (0.10) | 7.2 c,c (0.07) | 3.3 c,c (0.10) | 7.8 c,c (0.17) | 2.9 c,c (0.07) | 2.9 c,a (0.27) |

| MCF-7 (tumorigenic) | 1.3 c,c (0.054) | 0.43 0,0 (0.14) | 1.9 c,c (0.00005) | 5.0 c,a (0.02) | 5.1 c,c (0.05) | 0.64 0,b (0.027) | 4.9 c,a (0.03) | 5.3 c,c (0.03) | 2.5 c,0 (0.04) | 6.2 c,b (0.03) | 2.2 c,a (0.02) | 0.20 c,0 (0.15) |

| MDA-mb-231 (metastatic) | 0.45 b,c (0.13) | 0.13 c,0 (0.031) | 0.73 c,c (0.060) | 4.7 c,a (0.084) | 4.6 c,c (0.28) | 0.45 a,b (0.042) | 4.6 c,a (0.01) | 5.0 c,c (0.26) | 2.4 c,0 (0.14) | 5.4 c,b (0.17) | 2.0 c,a (0.05) | 1.3 a,0 (0.53) |

n.d. = not detected at quantifiable levels, significance calculated from 2X noise.

(Cho/PCho from 1H spectra) * (PCho/tot aqueous PO4 signal from 31P spectra) * 100. from 31P spectra) * 100.

not significant,

p < 0.05,

p < 0.01,

p < 0.001 vs. other cells in order from top to bottom.

Table 8.

Metabolites remaining unchanged regardless of cancer phenotype.

| Cell Line | Metabolites, ppm, as % total aqueous phosphate signal, n = 4 (± sem) (peaks at 5.38 and 5.07 are sugar phosphates, and ranging from -10.26 to -10.64 are UDPGα’s and NADα’s) | ||||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 5.38 | 5.07 | Pi, 3.15 | NDPβ, -5.26 | NDPβ, -5.36 | -10.26 | -10.44 | -10.47 | -10.54 | -10.64 | UDPGβ, -11.99 | PtdEtn,* -0.083 | PS/SPH,* -0.157 | PI, * -0.400 | PtdCho * plas, -0.772 | PtdCho, * -0.840 | -13.1 * | |

| MCF-10A (normal) | n.d. | n.d. | 10.5 (0.66) | 0.62 (0.016) | 0.73 (0.038) | 0.52 (0.054) | 0.94 (0.50) | 0.69 (0.41) | 0.55 (0.16) | 0.44 (0.18) | n.d. | 14.3 (1.5) | 0.68 (0.44) | 4.9 (1.3) | 5.3 (2.0) | 38.7 (3.2) | 8.2 (0.96) |

| MCF-7 (tumorigenic) | 0.13 (0.031) | 0.16 (0.04) | 10.4 (0.10) | 0.61 (0.029) | 0.83 (0.041) | 0.53 (0.046) | 0.53 (0.18) | 1.4 (0.42) | 0.38 (0.11) | 0.73 (0.040) | 0.23 (0.042) | 23.8 (6.6) | 0.62 (0.44) | 4.4 (1.3) | 2.6 (1.2) | 32.5 (9.0) | 1.3 (0.39) |

| MDA-mb-231 (metastatic) | 0.14 (0.021) | 0.19 (0.071) | 10.2 (1.0) | 0.50 (0.079) | 0.62 (0.033) | 0.36 (0.11) | 0.63 (0.19) | 0.53 (0.085) | 0.14 (0.062) | 0.57 (0.22) | 0.13 (0.033) | 22.3 (7.7) | 0.36 (0.13) | 4.8 (1.9) | 3.9 (1.1) | 50.0 (17.0) | 2.6 (0.87) |

n.d. = not detected at quantifiable levels, significance calculated from 2X noise.

(PtdCho nmol/mg protein from lipid 31P spectra) / (PCho nmol/mg protein from aqueous 31P spectra) * (PCho/total aqueous PO4 signal from 31P spectra) * 100.

Choline Pathway Gene (mRNA) Expression

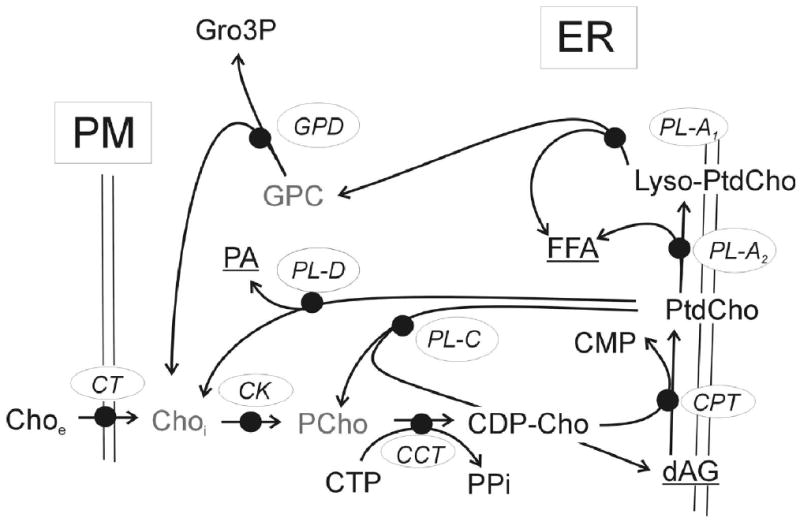

The choline metabolic pathway is well characterized and gene sequences of enzymes involved in the biosynthesis of phosphatidylcholine (PtdCho) are known (Figure 6) (7,8,53). PtdCho catabolism is mediated by three classes of PtdCho specific phospholipases (PLA2, PLC and PLD). Each class mediates PtdCho degradation by a separate pathway (Figure 6), but all can mediate the conversion of PtdCho back into cytosolic Cho or PCho. Using real-time RT-PCR, the relative mRNA expression of choline metabolism genes in normal and cancerous breast cells is quantified (Table 9). Expression is normalized to β-actin mRNA, which is known to be relatively unchanged amongst these cell lines (52) and is determined from multiple RNA extracts (n = 3).

Figure 6.

Phosphatidylcholine (PtdCho) metabolic pathway. The choline transporter (CT), mediates the uptake of extracellular choline (Choe) across the plasma membrane (PM). The Kennedy pathway enzymes: choline kinase (CK), converting intracellular choline (Choi) into phosphocholine (PCho); CTP:phosphocholine cytidylyltransferase (CCT), converting PCho and CTP into CDP-Cho; and CDP-choline:1,2-diacylglycerol cholinephosphotransferase (CPT), converting CDP-Cho and diacylglycerol (dAG) into PtdCho and CMP. PtdCho degradation is mediated by phospholipases A, C and D: PL-A2 converts PtdCho into lyso-PtdCho and free fatty acid (FFA); PL-A1 converts Lyso-PtdCho into GPC and FFA; PL-C converts PtdCho into PCho and dAG; and PL-D converts PtdCho into Cho and phosphatidate (PA).

Table 9.

Expression (mRNA) of genes in the choline pathway.

| Cell Line | Choline Metabolic Enzyme/β-actin ratio (2-CT/2-CT) * 1000 | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| CTL1A | CK1 | CHKL | CTP1α | CPT | PLD2α | PLD2β | |

| MCF-10A (normal) | 13.4 (6.2) | 2.8 (0.31) | 3.8a (0.30) | 50.0 (2.7) | 1.3 (0.79) | 16.0d (4.7) | 3.0 (0.38) |

| MCF-7 (tumorigenic) | 8.9 (2.6) | 7.4 (3.1) | 4.8 (0.20) | 41.0 (4.0) | 1.6 (0.23) | 2.9 (0.23) | 1.0e (0.13) |

| MDA-mb-231 (metastatic) | 3.5 (0.39) | 4.6 (1.4) | 8.4 (0.27) | 15.0b (1.0) | 6.2c (0.52) | 2.5 (0.12) | 2.2 (0.20) |

p < 0.002,

p < 0.004,

p < 0.007,

p < 0.05,

p < 0.01.

Choline kinase activity mediates the conversion of intracellular choline (Choi) into PCho. Expression of the choline kinase gene (CK) appears to be higher in cancer lines but the difference is not statistically significant. Choline-kinase like gene (CHKL) is the result of a recent gene duplication event of CK and is highly homologous (54), however CHKL’s biological activity has not been determined. These analyses detected CHKL transcripts at levels comparable to those of CK. CHKL mRNA is expressed at significantly higher levels in MDA-mb-231 cells but at significantly lower levels in MCF-7 cells. This is the first record of CHKL being expressed in breast cancer. The CTP:PCho cytidylyltransferase (CTP1) gene product converts PCho and CTP into CDP-choline. CTP1 has undergone a gene duplication event and is known to be expressed as both α and β forms. CTP1α was expressed in all of the breast cancer cell lines, but at significantly lower levels in MDA-mb-231 cells. Expression of CTP1β was also detected but at levels too low to accurately quantify. Choline phosphotransferase (CPT) activity converts CDP-Choline into PtdCho. CPT transcript was expressed at significantly higher levels in MDA-mb-231 cells. PLD mediates the conversion of PtdCho into Cho and phosphatidate (PA). PLD1 was found to be expressed at low unquantifiable levels. PLD2 is known to be expressed as two variants (α and β). Both variants were expressed in the breast cancer lines, however, PLD2α expression was significantly higher in MCF-10A cells and PLD2β expression was significantly lower in MCF-7 cells. Gene expression of PtdCho -PLC and PLA2 were not determined.

In addition to genes involved in PtdCho biosynthesis and catabolism, expression was determined for a number of putative choline transporters and their splice variants, including CHT1, OCT1, OCT2 and CTL1 (55). High expression was observed in all cell lines for CTL1 splice variant A (Table 9) and no expression was observed for variant B. Although expression appears to decrease with cancer progression, the values were not significantly different. Very low expression of OCT1 was detected and expression of CHT1 and OCT2 was undetectable (data not shown).

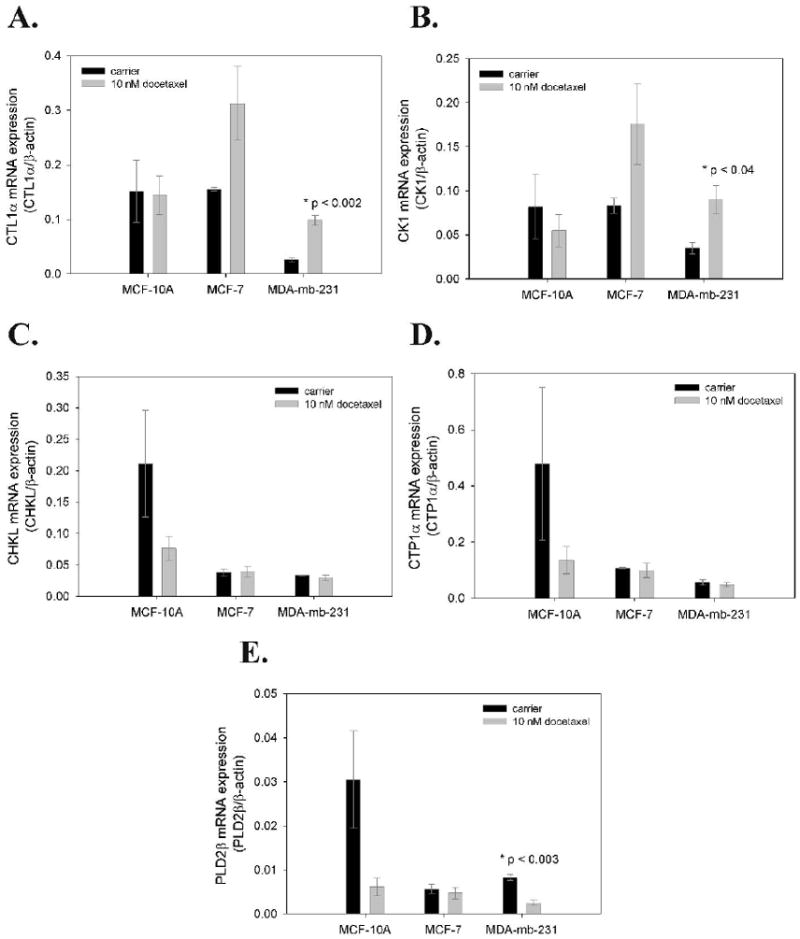

Changes in Expression of Choline Metabolism Genes in Response to Docetaxel

Significant changes in choline metabolite concentrations in these same breast cancer cell lines, 48 h after treatment with 10 nM docetaxel (34). In MDA-mb-231 cells, expression of the putative choline transporter, CTL1A (55), increased significantly 48 h post treatment with 10 nM docetaxel (Figure 7A). CTL1A also appears to increase in the cancer line MCF-7 but not with significance. The normal MCF-10A cell line did not increase CTL1A expression post-treatment. A similar profile was seen for CK1 expression response (7B), with significant increases in MDA-mb-231. CHKL, CTP1α and PLD2β all had similar expression response profiles with small post-treatment decreases in expression. Of the three, only PLD2β expression decreased significantly in the metastatic MDA-mb-231 cell line.

Figure 7.

Changes in mRNA expression of choline metabolism genes in human breast cancer cells 48 h post treatment with 10 nM docetaxel. Data are shown for a choline transporter (CTL1α), choline kinase (CK1), choline ethanolamine kinase (CHKL), CTP:phosphocholine cytidylyltransferase (CTP1α) and phospholipase 2 (PLD2β).

Discussion

Tumor choline metabolites are being studied as potential diagnostic markers for breast cancer which can be noninvasively detected and quantified via magnetic resonance spectroscopy (7,8). Herein, the in vivo detection and quantification of PCho and GPC in three different breast cancer xenograft tumor types in SCID mice (MCF-7/S, MCF-7/D40 and MDA-mb-231) is reported. Also reported is the ex vivo detection of tumor cytosolic and lipid choline metabolites. By MR spectroscopy of in vitro cell extracts, including two of the cancer cell lines and a normal breast line, an incremental increase in PCho, GPC and Lyso-PtdCho in cell lines of increasing cancer progression, and a general decrease in Cho are observed. Additionally, differences in other metabolites parsed by cancer progression are quantified.

In vivo results are not always recapitulated in vitro. Although generally elevated, PCho was quantifiably higher in the metastatic MDA-mb-231 cells in vitro, but not significantly different from MCF-7 tumors in vivo. We have previously shown that MDA-mb-231 tumor xenografts are more necrotic cf. MCF-7 tumors (44). Hence, this discrepancy might be explained by the partial volume effects of having a lower proportion of viable cancer cells in the whole tumor volume when compared to MCF-7 tumors. How this partial volume issue might influence clinical measurements is not entirely clear since the xenograft model is not necessarily an ideal model of human breast tumors. Differences in tumor perfusion and host interactions could have an effect on the proportion of viable cells to necrotic cells within a tumor.

Lowered Cho concentration in the cancerous cells implies lower choline transport and/or increased CK activity. A 2-fold increase in MCF-7 choline transport relative to HMECs was reported (38). Additionally, lower transport would be inconsistent with the observed elevation of PCho in cancer lines. An elevation in transcription of the kinases, CK1 and CHKL is observed in the cancer cells. This observation is consistent with reports of increased CK activity in breast cancer cells of increasing tumor grade (38,56), increased CK mRNA expression by micro array (57), and decreased PCho following treatment with CK inhibitors or RNAi (58,59). Increased CK activity would at least in part explain the observed lower levels of cytosolic Cho and elevated levels of PCho.

Significantly decreased CTP1α mRNA is observed in metastatic cancer cells, which codes for CTP:PCho cytidylyltransferase (CCT). This enzymatic step is rate-limiting for the generation of PtdCho from PCho, and CCT activity is subject to regulation at the level of transcription (60) and by higher-order, post translational regulatory mechanisms (61,62). CCT tightly regulates membrane lipid homeostasis and it is proposed that depletion of PtdCho in the membrane is followed by CCT activation. Regardless of higher order regulation, decreased transcript levels could lead to decreased CCT levels, translating to lower enzyme activity, and contributing to the elevation of PCho. Decreased CCT activity in NIH 3T3 fibroblasts was observed following Ha-ras transformation (63), which would be consistent with a role for CCT in the elevation of PCho in malignant cells.

Increased PtdCho degradation products in the phospholipase A2 (PLA2) pathway are detected (Figure 6). Both Lyso-PtdCho and GPC are products of PLA2 degradation of PtdCho and are significantly elevated by degree of cancer progression. GPC is converted to Cho and glycerol-3-phosphate (Gro3P) by GPC phosphodiesterase (64). Elevated Gro3P is observed incrementally by cancer progression. Based on this metabolic evidence, PLA2 activity appears to be elevated by degree of cancer progression. This increased activity would add to the PCho pool by providing Cho substrate for CK (65). These observations are possibly incongruous with the recent reporting of decreased PLA mRNA by micro array (57), however decreased mRNA expression does not necessarily lead to decreased levels of gene product or enzyme activity if other levels of regulation exist. Our result of decreased PLD mRNA in cancer is in agreement with the micro array data (57). Increased PLC activity was also reported by micro array (57), however we did not include PLC in our study. A number of PLC genes and activities have been identified, but we were not able to identify a PLC clone with activity specific for PtdCho.

Elevated transcription of genes does not necessarily translate to elevated gene product within the cell or elevated enzyme activity, but in many cases increased transcription does lead to increased activity. The combination of elevated choline metabolites and elevated expression of genes in the choline pathway suggests that multiple mechanisms are involved in generating increased tumor PCho (Table 10). Increased CK and PLA activity generating more PCho, coupled with tight regulation of CCT activity would lead to a buildup of PCho.

Table 10.

Proposed mechanisms for increased PCho by cancer progression and decreased PCho in response to docetaxel therapy.

| Condition | Evidence and Proposed Model | Net Metabolic Effect |

|---|---|---|

| Cancer Progression | ↑ choline transport (provides substrate for CK), ↑ CK activity and expression (converts Cho to PCho), ↓ CTP1α (CCT) expression and activity (inhibits conversion of PCho to PtdCho, activity decrease shown by others in MCF-7 cells), ↑ PLA activity (proposed because activity converts PtdCho to Lyso-PtdCho and GPC which are elevated), ↑ GPC phosphdiesterase activity (proposed because activity converts GPC to Cho and Gro3P (elevated), providing substrate for CK further elevating PCho). | ↓ Cho, ↑ PCho, ↑ Lyso-PtdCho, ↑ GPC, ↑ Gro3P. |

| Docetaxel Therapy | ↑ CTL1A* (suggesting increased transport), ↑ CK expression * (suggesting increased phosphorylation of Cho to PCho), ↑ CCT activity (proposed because ↑ GPC suggests PtdCho turnover which signal CCT activity, and is observed to increase following treatment with TNF), ↓ PLD expression, ↓ GPC phosphdiesterase activity (Proposed because activity converts GPC to Cho and Gro3P (not elevated), providing substrate for CK and elevating PCho. The opposite is observed). | ↓ PCho, ↑ GPC. |

These results are counterintuitive since a decrease in PCho is observed. However, GPC is further increased post treatment suggesting increased PtdCho turnover post treatment, potentially signaling an increase in CCT activity, utilizing PCho substrate pool.

Changes in expression of genes in the choline pathway were observed following docetaxel therapy. However, it is not simple to explain the coincident PCho decrease and GPC increase from the observed changes. Expression of both the choline transporter and kinase are increased, either of which would intuitively suggest an increase in PCho. Note that the observed decrease in PCho is coupled to an increase in GPC, which suggests increased PtdCho turnover. Since the homeostasis of membrane lipid content is tightly regulated by CCT, increased PtdCho turnover would suggest CCT activation and utilization of the PCho substrate pool. CTP1 mRNA did not increase, but, as discussed above, this gene’s product, CCT, is regulated post-translationally by a number of mechanisms (61,62). CCT activity increases following treatment of MCF-7 breast cancer cells with tumor necrosis factor (TNF) (66), which is consistent with a role for CCT in depletion of PCho following therapy. A significant therapy-induced decrease in PLD2β expression was also observed, which could contribute to the decrease in PCho levels by reducing the amount of choline substrate available to choline kinase. Further elevation of GPC post treatment suggests an additional increase in PLA2 activity. However, additional Gro3P was not observed post treatment (data not shown), suggesting that GPC phosphodiesterase activity is decreased. In this case, the degradation of GPC into choline would decrease and could contribute to the decrease in PCho by reducing the amount of choline substrate (Table 10).

In general terms, the evidence points toward the combination of elevated choline transport and kinase activity, decreased CCT activity and increased phopholipase activity as the factors leading to increased PCho in breast cancer. In contrast, the mechanism behind post therapy decreases in PCho appears to be a combination of increased CCT activity and decreased phospholipase and GPC phosphodiesterase activities. These conclusions are based on metabolite differences, changes in gene expression and reports from other groups. Absolute differences in enzyme activities have yet to be determined.

Acknowledgments

This work was funded by Grants NIH R24 CA83148 (R.J.G.) and NIH R01 CA80130 (Norbert W. Lutz), NIH R01 CA77575 (R.J.G.) and NIH R01 CA88285 (J.P.G.).

References

- 1.Smigal C, Jemal A, Ward E, Cokkinides V, Smith R, Howe HL, Thun M. Trends in breast cancer by race and ethnicity: update 2006. CA Cancer J Clin. 2006;56:168–183. doi: 10.3322/canjclin.56.3.168. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Perou CM, Sorlie T, Eisen MB, van de Rijn M, Jeffrey SS, Rees CA, Pollack JR, Ross DT, Johnsen H, Aksien LA, Fluge O, Pergamenschikov A, Williams C, Zhu SX, Lonning PE, Borresen-Dale AL, Brown PO, Botstein D. Molecular portraits of human breast tumours. Nature. 2000 Aug 17;406:747–752. doi: 10.1038/35021093. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Esteva FJ, Hortobagyi GN. Adjuvant systemic therapy for primary breast cancer. Surg Clin North Am. 1999;79:1075. doi: 10.1016/s0039-6109(05)70062-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.van ’t Veer Laura J, Dai H, van de Vijver MJ, He YD, Hart AA, Mao M, Peterse HL, Van Der Kooy K, Marton MJ, Witteveen AT, Schreiber GJ, Kerkhoven RM, Roberts C, Linsley PS, Bernards R, Friend SH. Gene expression profiling predicts clinical outcome of breast cancer. Nature. 2002 Jan 31;415:530–536. doi: 10.1038/415530a. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Negendank W. Studies of Human Tumors by MRS: a Review. NMR Biomed. 1992;5:303–324. doi: 10.1002/nbm.1940050518. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Leach MO, Verrill M, Glaholm J, Smith TA, Collins DJ, Payne GS, Sharp JC, Ronen SM, McCready VR, Powles TJ, Smith IE. Measurements of human breast cancer using magnetic resonance spectroscopy: a review of clinical measurements and a report of localized 31P measurements of response to treatment. NMR Biomed. 1998;11:314–340. doi: 10.1002/(sici)1099-1492(1998110)11:7<314::aid-nbm522>3.0.co;2-z. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Morse DL, Gillies RJ. Choline containing compounds as diagnostic, prognostic and therapeutic response indicators for breast cancer. In: Jagannathan NR, editor. Recent Advances in MR Imaging and Spectroscopy. Chapter 16. Jaypee Brothers Medical Publishers (P) Ltd.; New Delhi: 2005. pp. 345–397. [Google Scholar]

- 8.Gillies RJ, Morse DL. In vivo magnetic resonance spectroscopy in cancer. Annu Rev Biomed Eng. 2005;7:287–326. doi: 10.1146/annurev.bioeng.7.060804.100411. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Oberhaensli RD, Bore PJ, Rampling RP, Hiltonjones D, Hands LJ, Radda GK. Biochemical investigation of human-tumors in vivo with P-31 magnetic-resonance spectroscopy. Lancet. 1986 Jul 5;2:8–11. doi: 10.1016/s0140-6736(86)92558-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Sijens PE, Bovee WM, Seijkens D, Los G, Rutgers DH. In vivo 31P-nuclear magnetic resonance study of the response of a murine mammary tumor to different doses of gamma-radiation. Cancer Res. 1986;46:1427–1432. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Ng TC, Grundfest S, Vijayakumar S, Baldwin NJ, Majors AW, Karalis I, Meaney TF, Shin KH, Thomas FJ, Tubbs R. Therapeutic Response of Breast-Carcinoma Monitored by P-31 MRS Insitu. Magn Reson Med. 1989;10:125–134. doi: 10.1002/mrm.1910100112. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Redmond OM, Stack JP, O’Connor NG, Codd MB, Ennis JT. In vivo phosphorus-31 magnetic resonance spectroscopy of normal and pathological breast tissues. Br J Radiol. 1991;64:210–216. doi: 10.1259/0007-1285-64-759-210. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Merchant TE, Thelissen GR, de Graaf PW, Den Otter W, Glonek T. Clinical magnetic resonance spectroscopy of human breast disease. Invest Radiol. 1991;26:1053–1059. doi: 10.1097/00004424-199112000-00003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Merchant TE, Gierke LW, Meneses P, Glonek T. P 31 magnetic-resonance spectroscopic profiles of neoplastic human-breast tissues. Cancer Res. 1988 Sep 15;48:5112–5118. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Smith TA, Glaholm J, Leach MO, Machin L, Collins DJ, Payne GS, McCready VR. A comparison of in vivo and in vitro 31P NMR spectra from human breast tumours: variations in phospholipid metabolism. Br J Cancer. 1991;63:514–516. doi: 10.1038/bjc.1991.122. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Kalra R, Wade KE, Hands L, Styles P, Camplejohn R, Greenall M, Adams GE, Harris AL, Radda GK. Phosphomonoester is associated with proliferation in human breast cancer: a 31P MRS study. Br J Cancer. 1993;67:1145–1153. doi: 10.1038/bjc.1993.211. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Barzilai A, Horowitz A, Geier A, Degani H. Phosphate metabolites and steroid hormone receptors of benign and malignant breast tumors. A Nuclear Magnetic Resonance study. Cancer. 1991 Jun 1;67:2919–2925. doi: 10.1002/1097-0142(19910601)67:11<2919::aid-cncr2820671135>3.0.co;2-z. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Smith TA, Bush C, Jameson C, Titley JC, Leach MO, Wilman DE, McCready VR. Phospholipid metabolites, prognosis and proliferation in human breast carcinoma. NMR Biomed. 1993;6:318–323. doi: 10.1002/nbm.1940060506. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Jagannathan NR, Singh M, Govindaraju V, Raghunathan P, Coshic O, Julka PK, Rath GK. Volume localized in vivo proton MR spectroscopy of breast carcinoma: variation of water-fat ratio in patients receiving chemotherapy. NMR Biomed. 1998;11:414–422. doi: 10.1002/(sici)1099-1492(199812)11:8<414::aid-nbm537>3.0.co;2-w. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Roebuck JR, Cecil KM, Schnall MD, Lenkinski RE. Human breast lesions: Characterization with proton MR spectroscopy. Radiology. 1998;209:269–275. doi: 10.1148/radiology.209.1.9769842. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Gribbestad IS, Singstad TE, Nilsen G, Fjosne HE, Engan T, Haugen OA, Rinck PA. In vivo H-1 MRS of normal breast and breast tumors using a dedicated double breast coil. J Magn Reson Imaging. 1998;8:1191–1197. doi: 10.1002/jmri.1880080602. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Kvistad KA, Bakken IJ, Gribbestad IS, Ehrnholm B, Lundgren S, Fjosne HE, Haraldseth O. Characterization of neoplastic and normal human breast tissues with in vivo (1)H MR spectroscopy. J Magn Reson Imaging. 1999;10:159–164. doi: 10.1002/(sici)1522-2586(199908)10:2<159::aid-jmri8>3.0.co;2-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Seenu V, Pavan Kumar MN, Sharma U, Gupta SD, Mehta SN, Jagannathan NR. Potential of magnetic resonance spectroscopy to detect metastasis in axillary lymph nodes in breast cancer. Magn Reson Imaging. 2005;23:1005–1010. doi: 10.1016/j.mri.2005.10.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Thomas MA, Wyckoff N, Yue K, Binesh N, Banakar S, Chung HK, Sayre J, DeBruhl N. Two-dimensional MR spectroscopic characterization of breast cancer in vivo. Technol Cancer Res Treat. 2005;4:99–106. doi: 10.1177/153303460500400113. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Jacobs MA, Barker PB, Argani P, Ouwerkerk R, Bhujwalla ZM, Bluemke DA. Combined dynamic contrast enhanced breast MR and proton spectroscopic imaging: a feasibility study. J Magn Reson Imaging. 2005;21:23–28. doi: 10.1002/jmri.20239. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Stanwell P, Gluch L, Clark D, Tomanek B, Baker L, Giuffre B, Lean C, Malycha P, Mountford C. Specificity of choline metabolites for in vivo diagnosis of breast cancer using 1H MRS at 1.5 T. Eur Radiol. 2005;15:1037–1043. doi: 10.1007/s00330-004-2475-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Jagannathan NR, Kumar M, Seenu V, Coshic O, Dwivedi SN, Julka PK, Srivastava A, Rath GK. Evaluation of total choline from in-vivo volume localized proton MR spectroscopy and its response to neoadjuvant chemotherapy in locally advanced breast cancer. Br J Cancer. 2001 Apr 20;84:1016–1022. doi: 10.1054/bjoc.2000.1711. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Cecil KM, Schnall MD, Siegelman ES, Lenkinski RE. The evaluation of human breast lesions with magnetic resonance imaging and proton magnetic resonance spectroscopy. Breast Cancer Res Treat. 2001;68:45–54. doi: 10.1023/a:1017911211090. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Kim JK, Park SH, Lee HM, Lee YH, Sung NK, Chung DS, Kim OD. In vivo 1H-MRS evaluation of malignant and benign breast diseases. Breast. 2003;12:179–182. doi: 10.1016/s0960-9776(03)00012-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Bolan PJ, Meisamy S, Baker EH, Lin J, Emory T, Nelson M, Everson LI, Yee D, Garwood M. In vivo quantification of choline compounds in the breast with 1H MR spectroscopy. Magn Reson Med. 2003;50:1134–1143. doi: 10.1002/mrm.10654. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Baik HM, Su MY, Yu H, Mehta R, Nalcioglu O. Quantification of choline-containing compounds in malignant breast tumors by 1H MR spectroscopy using water as an internal reference at 1.5 T. MAGMA. 2006;19:96–104. doi: 10.1007/s10334-006-0032-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Meisamy S, Bolan PJ, Baker EH, Pollema MG, Le CT, Kelcz F, Lechner MC, Luikens BA, Carlson RA, Brandt KR, Amrami KK, Nelson MT, Everson LI, Emory TH, Tuttle TM, Yee D, Garwood M. Adding in vivo quantitative 1H MR spectroscopy to improve diagnostic accuracy of breast MR imaging: preliminary results of observer performance study at 4.0 T. Radiology. 2005;236:465–475. doi: 10.1148/radiol.2362040836. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Gribbestad IS, Petersen SB, Fjosne HE, Kvinnsland S, Krane J. 1H NMR spectroscopic characterization of perchloric acid extracts from breast carcinomas and non-involved breast tissue. NMR Biomed. 1994;7:181–194. doi: 10.1002/nbm.1940070405. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Morse DL, Raghunand N, Sadarangani P, Murthi S, Job C, Day S, Howison C, Gillies RJ. Response of choline metabolites to docetaxel therapy is quantified in vivo by localized 31P MRS of human breast cancer xenografts and in vitro by high-resolution 31P NMR spectroscopy of cell extracts. Magn Reson Med. doi: 10.1002/mrm.21333. in press. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Singer S, Souza K, Thilly WG. Pyruvate utilization, phosphocholine and adenosine triphosphate (ATP) are markers of human breast tumor progression: a 31P- and 13C-nuclear magnetic resonance (NMR) spectroscopy study. Cancer Res. 1995 Nov 15;55:5140–5145. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Ting YL, Sherr D, Degani H. Variations in energy and phospholipid metabolism in normal and cancer human mammary epithelial cells. Anticancer Res. 1996;16:1381–1388. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Aboagye EO, Bhujwalla ZM. Malignant transformation alters membrane choline phospholipid metabolism of human mammary epithelial cells. Cancer Res. 1999 Jan 1;59:80–84. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Katz-Brull R, Seger D, Rivenson-Segal D, Rushkin E, Degani H. Metabolic markers of breast cancer: enhanced choline metabolism and reduced choline-ether-phospholipid synthesis. Cancer Res. 2002 Apr 1;62:1966–1970. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Taylor CW, Dalton WS, Parrish PR, Gleason MC, Bellamy WT, Thompson FH, Roe DJ, Trent JM. Different Mechanisms of Decreased Drug Accumulation in Doxorubicin and Mitoxantrone Resistant Variants of the MCF7 Human Breast-Cancer Cell-Line. British Journal of Cancer. 1991;63:923–929. doi: 10.1038/bjc.1991.202. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Morse DL, Gray H, Payne CM, Gillies RJ. Docetaxel induces cell death through mitotic catastrophe in human breast cancer cells. Mol Cancer Ther. 2005;4:1495–1504. doi: 10.1158/1535-7163.MCT-05-0130. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Paine-Murrieta GD, Taylor CW, Curtis RA, Lopez MH, Dorr RT, Johnson CS, Funk CY, Thompson F, Hersh EM. Human tumor models in the severe combined immune deficient (SCID) mouse. Cancer Chemother Pharmacol. 1997;40:209–214. doi: 10.1007/s002800050648. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Jennings D, Hatton BN, Guo JY, Galons JP, Trouard TP, Raghunand N, Marshall J, Gillies RJ. Early response of prostate carcinoma xenografts to docetaxel chemotherapy monitored with diffusion MRI. Neoplasia. 2002;4:255–262. doi: 10.1038/sj.neo.7900225. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Jordan BF, Black K, Robey IF, Runquist M, Powis G, Gillies RJ. Metabolite changes in HT-29 xenograft tumors following HIF-1alpha inhibition with PX-478 as studied by MR spectroscopy in vivo and ex vivo. NMR Biomed. 2005;18:430–439. doi: 10.1002/nbm.977. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Morse DL, Galons JP, Payne CM, Jennings DL, Day S, Xia G, Gillies RJ. MRI-measured water mobility increases in response to chemotherapy via multiple cell-death mechanisms. NMR Biomed. 2007 Jan 30; doi: 10.1002/nbm.1127. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Ordidge RJ, Connelly A, Lohman JAB. Image-selected in vivo spectroscopy (ISIS): a new technique for spatially selective NMR spectroscopy. J Magn Reson. 1986;66:283. [Google Scholar]

- 46.Connelly A, Counsell C, Lohman JAB, Ordidge RJ. Outer Volume Suppressed Image Related Invivo Spectroscopy (OSIRIS), A High-Sensitivity Localization Technique. Journal of Magnetic Resonance. 1988;78:519–525. [Google Scholar]

- 47.Blagosklonny MV, Bishop PC, Robey R, Fojo T, Bates SE. Loss of cell cycle control allows selective microtubule-active drug-induced Bcl-2 phosphorylation and cytotoxicity in autonomous cancer cells. Cancer Res. 2000 Jul 1;60:3425–3428. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Katz-Brull R, Margalit R, Degani H. Differential routing of choline in implanted breast cancer and normal organs. Magn Reson Med. 2001;46:31–38. doi: 10.1002/mrm.1157. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Tyagi RK, Azrad A, Degani H, Salomon Y. Simultaneous extraction of cellular lipids and water-soluble metabolites: evaluation by NMR spectroscopy. Magn Reson Med. 1996;35:194–200. doi: 10.1002/mrm.1910350210. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Bradford MM. Rapid and sensitive method for quantitation of microgram quantities of protein utilizing principle of protein-dye binding. Anal Biochem. 1976;72:248–254. doi: 10.1016/0003-2697(76)90527-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Lutz NW, Yahi N, Fantini J, Cozzone PJ. Analysis of individual purine and pyrimidine nucleoside di- and triphosphates and other cellular metabolites in PCA extracts by using multinuclear high resolution NMR spectroscopy. Magnetic Resonance in Medicine. 1996;36:788–795. doi: 10.1002/mrm.1910360519. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Morse DL, Carroll D, Weberg L, Borgstrom MC, Ranger-Moore J, Gillies RJ. Determining suitable internal standards for mRNA quantification of increasing cancer progression in human breast cells by real-time reverse transcriptase polymerase chain reaction. Anal Biochem. 2005 Jul 1;342:69–77. doi: 10.1016/j.ab.2005.03.034. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Kent C, Carman GM. Interactions among pathways for phosphatidylcholine metabolism, CTP synthesis and secretion through the Golgi apparatus. TIBS. 1999;24 doi: 10.1016/s0968-0004(99)01365-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Ishidate K. Choline/ethanolamine kinase from mammalian tissues. Biochem Biophys Acta. 1997;1348:70–78. doi: 10.1016/s0005-2760(97)00118-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Michel V, Yuan Z, Ramsubir S, Bakovic M. Choline transport for phospholipid synthesis. Exp Biol Med (Maywood) 2006;231:490–504. doi: 10.1177/153537020623100503. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Ramirez de Molina, Gutierrez R, Ramos MA, Silva JM, Silva J, Bonilla F, Sanchez JJ, Lacal JC. Increased choline kinase activity in human breast carcinomas: clinical evidence for a potential novel antitumor strategy. Oncogene. 2002 Jun 20;21:4317–4322. doi: 10.1038/sj.onc.1205556. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Glunde K, Jie C, Bhujwalla ZM. Molecular causes of the aberrant choline phospholipid metabolism in breast cancer. Cancer Res. 2004 Jun 15;64:4270–4276. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-03-3829. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Al-Saffar NM, Troy H, Ramirez de Molina A, Jackson LE, Madhu B, Griffiths JR, Leach MO, Workman P, Lacal JC, Judson IR, Chung YL. Noninvasive magnetic resonance spectroscopic pharmacodynamic markers of the choline kinase inhibitor MN58b in human carcinoma models. Cancer Res. 2006 Jan 1;66:427–434. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-05-1338. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Glunde K, Raman V, Mori N, Bhujwalla ZM. RNA interference-mediated choline kinase suppression in breast cancer cells induces differentiation and reduces proliferation. Cancer Res. 2005 Dec 1;65:11034–11043. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-05-1807. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Golfman LS, Bakovic M, Vance DE. Transcription of the CTP:phosphocholine cytidylyltransferase alpha gene is enhanced during the S phase of the cell cycle. J Biol Chem. 2001 Nov 23;276:43688–43692. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M108170200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Clement JM, Kent C. CTP:phosphocholine cytidylyltransferase: insights into regulatory mechanisms and novel functions. Biochem Biophys Res Commun. 1999 Apr 21;257:643–650. doi: 10.1006/bbrc.1999.0512. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Cornell RB, Northwood IC. Regulation of CTP:phosphocholine cytidylyltransferase by amphitropism and relocalization. Trends Biochem Sci. 2000;25:441–447. doi: 10.1016/s0968-0004(00)01625-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Momchilova A, Markovska T, Pankov R. Ha-ras-transformation alters the metabolism of phosphatidylethanolamine and phosphatidylcholine in NIH 3T3 fibroblasts. Cell Biol Int. 1999;23:603–610. doi: 10.1006/cbir.1999.0430. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Podo F. Tumour Phospholipid Metabolism. NMR Biomed. 1999;12:413–439. doi: 10.1002/(sici)1099-1492(199911)12:7<413::aid-nbm587>3.0.co;2-u. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Exton JH. Phospholipase D. Ann N Y Acad Sci. 2000;905:61–68. doi: 10.1111/j.1749-6632.2000.tb06538.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Bogin L, Papa MZ, Polak-Charcon S, Degani H. TNF-induced modulations of phospholipid metabolism in human breast cancer cells. Biochim Biophys Acta. 1998 Jun 15;1392:217–232. doi: 10.1016/s0005-2760(98)00035-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]