Abstract

A shift towards early morning biting behavior of the major malaria vector Anopheles funestus have been observed in two villages in south Benin following distribution of long-lasting insecticidal nets (LLINs), but the impact of these changes on the personal protection efficacy of LLINs was not evaluated. Data from human and An. funestus behavioral surveys were used to measure the human exposure to An. funestus bites through previously described mathematical models. We estimated the personal protection efficacy provided by LLINs and the proportions of exposure to bite occurring indoors and/or in the early morning. Average personal protection provided by using of LLIN was high (≥80% of the total exposure to bite), but for LLIN users, a large part of remaining exposure occurred outdoors (45.1% in Tokoli-V and 68.7% in Lokohoué) and/or in the early morning (38.5% in Tokoli-V and 69.4% in Lokohoué). This study highlights the crucial role of LLIN use and the possible need to develop new vector control strategies targeting malaria vectors with outdoor and early morning biting behavior. This multidisciplinary approach that supplements entomology with social science and mathematical modeling illustrates just how important it is to assess where and when humans are actually exposed to malaria vectors before vector control program managers, policy-makers and funders conclude what entomological observations imply.

Introduction

Recent evidence suggests that malaria vectors may avoid contact with long lasting insecticidal nets (LLINs) by feeding outdoors [1], at times when people do not use them in the early evening [2], [3], and/or early morning [4]. Moiroux and colleagues [4] provide evidence for a shift in malaria vector Anopheles funestus biting behavior following an LLIN distribution program with universal coverage targets in two villages in southern Benin, Tokoli-Vidjinnagnimon (Tokoli-V) and Lokohoué. Following LLIN distribution, the peak of biting activity exhibited by An. funestus was delayed, even resulting in diurnal biting behavior of a large proportion of the vector population in Lokohoué. Furthermore, the proportion of vectors collected outdoors increased in Tokoli-V. However, human landing catches are not sufficient in themselves to survey patterns of normal human exposure to mosquito bites. Indeed, the timing of human activities, and sleeping behaviors in particular, has a strong modulating effect upon human-mosquito contact and the effectiveness of LLINs that, apart from affecting malaria through a community effect, provide personal protection against bites in specific time and space [2], [5]. Quantifying interactions between mosquitoes and humans is essential to enable meaningful evaluation of personal protection methods. Also, quantifying and characterizing residual malaria transmission [5], [6] will allow targeting with complementary vector control strategies.

In this study, we investigated the interactions between mosquitoes and humans [6] in relation to LLINs use in the same two villages in southern Benin where changes in An. funestus biting behavior have recently been observed [4].

Methods

We carried out mosquito collection in the villages of Tokoli-Vidjinnagnimon (Tokoli-V) (6°26′57.1″ N, 2°09′36.6″ E) and Lokohoué (6°24′24.2″ N, 2°10′32.1″ E) to study the impact of mass distributions of LLINs with universal coverage on the biting behavior of A. funestus [4]. Mosquitoes were collected in April 2011 during six nights in four sites per village, both indoors and outdoors, in the act of biting human volunteers [7] between 23∶00 and 09∶00 [4]. All 1284 mosquito specimens [4] that were classified as members of the Funestus group by morphology [8], [9] were subsequently confirmed to be An. funestus Giles by species-specific polymerase chain reaction [10] and all data and analyses presented after refer only to unambiguously identified specimens of this important vector species.

In order to obtain appropriate data regarding relevant human behaviors, we surveyed 289 and 252 individuals living in 100 and 114 randomly selected households in Tokoli-V and Lokohoué, respectively, in March 2013 (dry season). According to an exhaustive census carried out by our team in 2007 [11], these samples represented 86% and 98% of the overall population of Tokoli-V and Lokohoué, respectively. We asked the head of the household the time at which each person who usually leave in the household (1) entered and exited his own house the night preceding the survey and (2) the time each LLIN user entered and exited his sleeping space the night preceding the survey. Insufficiently precise answers were not used for further analysis (Text S1).

Data from the human and An. funestus behavioral surveys were used to measure the human exposure to An. funestus bites through previously described mathematical models [2] (Text S1).

The average true personal protection of using an LLIN (P*), i.e. the proportion of exposure to all bites that would otherwise occur both indoors and outdoors that is prevented by using of LLIN, as well as the proportion of protected exposure which occurred indoors for LLIN users either accounting for the personal protection provided by net use (πi,n) or ignoring it to compare with available estimates for unprotected people (πi) [6] were calculated. Exposure when sleeping under an LLIN Permanet 2.0 (i.e. the LLIN distributed by the National Malaria Control Program in southern Benin) was assumed to be reduced by 92% as estimated for An. coluzzii in Benin in an area (Malanville) with very low levels of pyrethroid resistance [12].

Moreover, to assess the relative importance of the high level of host searching behavior of An. funestus during daylight hours after 6∶00, we also calculated the proportion of exposure occurring after 6∶00 for unprotected people (πd) and net users (πd,n) (Text S1).

Ethics statement

The IRD (Institut de Recherche pour le Développement) Ethics Committee and the National Research Ethics Committee of Benin approved the study (CNPERS, reference number IRB00006860). All necessary permits were obtained for the described field studies. Mosquito collections were performed in privately owned houses. No mosquito collection was done without the approval of the head of the village, the owner and occupants of the collection house. Mosquito collectors gave their written informed consent and were treated free of charge for malaria presumed illness throughout the study. The field studies did not involve endangered or protected species.

Results

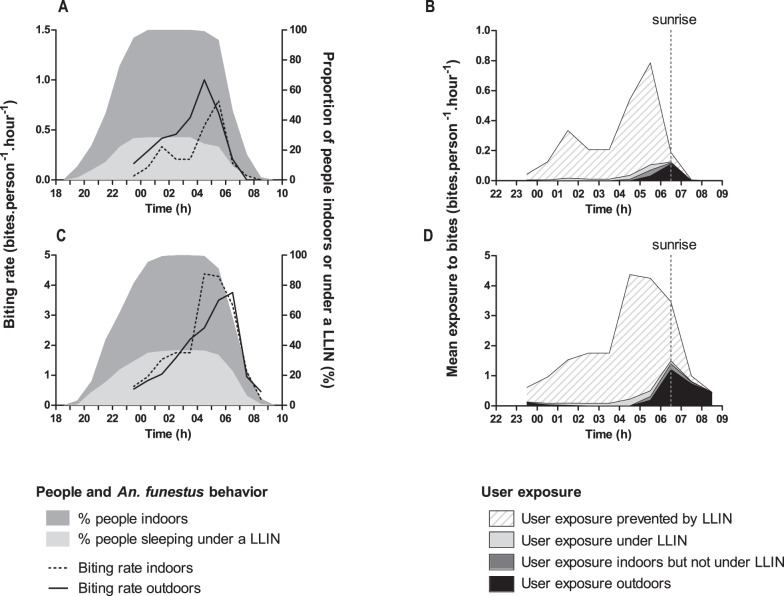

Figure 1 shows humans and An. funestus behavior profiles as well as derived estimates of hourly exposure and prevented exposure to An. funestus bite for LLIN users in Tokoli-V and Lokohoué. Only 28.5% and 36.7% of people used LLINs during the human behavioral survey in Tokoli-V and Lokohoué, respectively. Slightly different human behavior profiles between villages were observed: inhabitants of Tokoli-V went both indoors and to bed earlier than Lokohoué inhabitants (Figure 1A and 1C). Most of the total exposure to bites occurred indoors but was largely preventable by using of LLIN (Figure 1B and 1D). The peak of exposure for LLIN users occurred outdoors in and around sunrise from 6∶00 h to 7∶00 h but extended over the following two hours of full daylight in Lokohoué. Raw data are available in Table S1.

Figure 1. Hourly human and A. funestus behavior and hourly exposure to bites of LLIN users in Tokoli-Vidjinnagnimon (A, B) and Lokohoué (C, D).

Despite the obvious shift to feeding in and around dawn, LLINs were still estimated to provide average ‘true’ personal protection (P*) against 87.1% and 80.3% of exposure to An. funestus bites in Tokoli-V and Lokohoué, respectively, because the corresponding proportions of exposure that these LLIN users would have experienced indoors in the absence of nets (πi) were 94% and 86.4% (Table 1). However, a large part of the remaining bites that LLIN users are exposed to are estimated to occur outdoors (1−πi,n = 46.1% in Tokoli-V and 68.7% in Lokohoué) and/or after dawn (πd,n = 38.5% in Tokoli-V and 69.4% in Lokohoué).

Table 1. True average protection efficacy of LLINs against transmission and proportions of indoor and diurnal exposure to bites in Tokoli-Vidjinnagnimon and Lokohoué.

| Village | True average LLINpersonal protectionefficacy P* (% [95% CI]) | Exposure occurringindoors (% [95% CI]) | Exposure occurringafter 6∶00 (% [95% CI]) | ||

| Net users (πi,n) | Non-users (πi) | Net users (πd,n) | Non-users (πd) | ||

| Tokoli-V | 87.1 [81.9, 91.2] | 54.9 [35.6, 78] | 94 [88.7, 97.9] | 38.5 [16.2, 59.4] | 8.1 [3.4, 13.6] |

| Lokohoué | 80.3 [77.1, 83.2] | 31.3 [24.4, 39] | 86.4 [82.9, 89.5] | 69.4 [62.5, 75.7] | 24.5 [21.3, 27.8] |

LLIN: Long lasting insecticidal net.

Discussion

This analysis of behavioral interactions between An. funestus and humans in two villages of southern Benin showed that the ‘true’ average personal protection of LLINs remained very high (>80%), even when biting activity peaked as net use dropped at dawn [4]. This indicates that LLINs provide, on average, a high level of personal protection even in such a context with clear evidence of increasing diurnal exposure outdoors. While these worrying new vector behaviors are obviously of concern, particularly when viewed in terms of the coverage gap they create [13] in this particular setting, observations of limited impact of LLINs upon disease at the community level [11] appear to be primarily caused by low usage rates (<37% in the present study). Among the reasons for low use of LLINs during the dry season are the higher nocturnal temperatures, the lower biting nuisance [14], and the lack of awareness messaging [15]. Clearly greater efforts are needed to increase the availability of LLINs, to develop more comfortable and convenient bed nets, and to try to increase usage of available nets through awareness campaigns.

To note that the personal protection efficacy P* is an average value for the entire population and some groups of people may be much more exposed. For example, a simple simulation indicates that for very early risers (to bed at 22∶00 and outside the house at 5∶00), personal protection efficacy was 62.5% in Lokohoué, much lower than the average value of 80.3% reported in this study. Moreover, this estimate, as its name implies, refers only to the personal protection provided by using of LLIN and does not give any information about a possible community effect. Indeed, sufficient reductions in mosquito feeding and/or mosquito population may be beneficial to non-user of LLINs in terms of malaria transmission and disease [16].

We found that for LLIN users in Lokohoué, the substantial diurnal behavior of An. funestus led to most residual exposure occurring outdoors (68.7%) and/or in the early morning after 6∶00 (69.4%) and in Tokoli-V it approaches 50%. The fact that LLIN user exposure to An. funestus bites occurred both indoors and outdoors supports the hypothesis [17], [18] that, even if full universal coverage of LLINs were achieved, both improved indoor control of this highly efficient vector and complementary methods that target vectors outdoors during waking hours or at source [1] will be required to achieve much lower levels of exposure to bites from malaria vectors.

This study has two minor limitations. First, the human behavioral survey was carried out two years after the mosquito collections and human behaviors may have changed between 2011 and 2013. However, we paid great attention to carry out the human behavioral survey during the same period of the year than entomological surveys (end of the long dry season, out of school holydays) to prevent any changes in human behavior in relation to the agricultural or scholar calendars. Moreover in these villages, we have not observed changes (electrification, shift in economic activity…) likely to strongly modify human behaviors. Consequently, the fact that human and mosquito survey do not coincide was less likely to change the results and conclusions. The other issue is that mosquitoes were not collected before 23∶00 and additional biting may have occurred earlier in the evening. Because the majority of people were outdoors before 23∶00 (Figure 1A and 1C), we may have overestimated the proportion of bites occurring indoors and the ‘true’ average personal protection efficacy of LLINs.

To conclude, this study of human-mosquito behavioral interactions highlights the crucial role of LLIN use for personal protection and the possible need to develop new complementary vector control strategies targeting vectors with outdoor and early morning biting behavior. Moreover, this multidisciplinary approach that supplements entomology with social science and mathematical modeling illustrates just how important it is to assess where and when humans are actually exposed to malaria vectors, rather than just where they are caught in surveys of mosquito feeding activity, before vector control program managers, policy-makers and funders conclude what such entomological observations imply.

Supporting Information

Dataset.

(DOC)

Questionnaire of the human behavioural survey and formulae used to calculate mean exposure to bite, true average personal protection efficacy of LLINs (P*), proportions of indoor exposure to bite (πi and πi,n), and proportions of diurnal exposure to bite (πd and πd,n).

(DOC)

Acknowledgments

We thank populations of Tokoli-Vidjinnagnimon and Lokohoué for their kind support and collaboration. We also thank all the field staff for their strong commitment to this project. Special thanks are due to Carine Aicheou and Amal Dahounto for their assistance.

Data Availability

The authors confirm that all data underlying the findings are fully available without restriction. All relevant data are within the paper and its Supporting Information files.

Funding Statement

This work was supported by the Anopheles Biology and Control (ABC) Network and by the Institut de Recherche pour le Développement and the French Ministry of Foreign Affairs through the FSP project REFS No. 2006-22. The funders had no role in study design, data collection and analysis, decision to publish, or preparation of the manuscript.

References

- 1. Govella NJ, Ferguson H (2012) Why Use of Interventions Targeting Outdoor Biting Mosquitoes will be Necessary to Achieve Malaria Elimination. Front Physiol 3: 199. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Seyoum A, Sikaala CH, Chanda J, Chinula D, Ntamatungiro AJ, et al. (2012) Human exposure to anopheline mosquitoes occurs primarily indoors, even for users of insecticide-treated nets in Luangwa Valley, South-east Zambia. Parasit Vectors 5: 101. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Yohannes M, Boelee E (2011) Early biting rhythm in the afro-tropical vector of malaria, Anopheles arabiensis, and challenges for its control in Ethiopia. Medical and Veterinary Entomology 26: 103–105. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Moiroux N, Gomez MB, Pennetier C, Elanga E, Djenontin A, et al. (2012) Changes in Anopheles funestus biting behavior following universal coverage of long-lasting insecticidal nets in Benin. J Infect Dis 206: 1622–1629. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Stoddard ST, Morrison AC, Vazquez-Prokopec GM, Paz Soldan V, Kochel TJ, et al. (2009) The role of human movement in the transmission of vector-borne pathogens. PLoS Negl Trop Dis 3: e481. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Killeen GF, Kihonda J, Lyimo E, Oketch FR, Kotas ME, et al. (2006) Quantifying behavioural interactions between humans and mosquitoes: evaluating the protective efficacy of insecticidal nets against malaria transmission in rural Tanzania. BMC Infect Dis 6: 161. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Coffinet T, Rogier C, Pages F (2009) [Evaluation of the anopheline mosquito aggressivity and of malaria transmission risk: methods used in French Army]. Med Trop (Mars) 69: 109–122. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Gillies M, Coetzee M (1987) A supplement to the Anophelinae of Africa South of the Sahara (Afrotropical Region). Johannesburg, South Africa: South African Institute for Medical Research. 143 p. [Google Scholar]

- 9. Gillies M, De Meillon B (1968) The Anophelinae of Africa South of the Sahara (Ethiopian Zoogeographical Region). Publication of the South Afr Inst Med Res 54: 343. [Google Scholar]

- 10. Koekemoer LL, Kamau L, Hunt RH, Coetzee M (2002) A cocktail polymerase chain reaction assay to identify members of the Anopheles funestus (Diptera: Culicidae) group. Am J Trop Med Hyg 66: 804–811. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Corbel V, Akogbeto M, Damien GB, Djenontin A, Chandre F, et al. (2012) Combination of malaria vector control interventions in pyrethroid resistance area in Benin: a cluster randomised controlled trial. Lancet Infect Dis 12: 617–626. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Corbel V, Chabi J, Dabire RK, Etang J, Nwane P, et al. (2010) Field efficacy of a new mosaic long-lasting mosquito net (PermaNet 3.0) against pyrethroid-resistant malaria vectors: a multi centre study in Western and Central Africa. Malar J 9: 113. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Killeen GF, Seyoum A, Sikaala C, Zomboko AS, Gimnig JE, et al. (2013) Eliminating malaria vectors. Parasit Vectors 6: 172. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Moiroux N, Boussari O, Djènontin A, Damien G, Cottrell G, et al. (2012) Dry season determinants of malaria disease and net use in Benin, west Africa. PLoS One 7: e30558. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Toe LP, Skovmand O, Dabire KR, Diabate A, Diallo Y, et al. (2009) Decreased motivation in the use of insecticide-treated nets in a malaria endemic area in Burkina Faso. Malar J 8: 175. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Hawley WA, Phillips-Howard PA, ter Kuile FO, Terlouw DJ, Vulule JM, et al. (2003) Community-wide effects of permethrin-treated bed nets on child mortality and malaria morbidity in western Kenya. Am J Trop Med Hyg 68: 121–127. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Lindblade KA (2013) Commentary: Does a mosquito bite when no one is around to hear it? Int J Epidemiol 42: 247–249. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Killeen GF, Chitnis N (2014) Potential causes and consequences of behavioural resilience and resistance in malaria vector populations: a mathematical modelling analysis. Malar J 13: 97. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Dataset.

(DOC)

Questionnaire of the human behavioural survey and formulae used to calculate mean exposure to bite, true average personal protection efficacy of LLINs (P*), proportions of indoor exposure to bite (πi and πi,n), and proportions of diurnal exposure to bite (πd and πd,n).

(DOC)

Data Availability Statement

The authors confirm that all data underlying the findings are fully available without restriction. All relevant data are within the paper and its Supporting Information files.