Abstract

Aims

To explore factors at the family caregiver and nursing home administrative levels that may affect participation in a clinical trial to determine the efficacy of hand feeding versus percutaneous gastrostomy tube feeding in persons with late-stage dementia.

Background

Decision-making regarding use of tube feeding vs. hand feeding for persons with late-stage dementia is fraught with practical, emotional and ethical issuesand is not informed by high levels of evidence.

Design

Qualitative case study.

Methods

Transcripts of focus groups with family caregivers were reviewed for themes guided by behavioral theory. Analyses of notes from contacts with nursing home administrators and staff were reviewed for themes guided by an organizational readiness model. Data were collected between the years 2009–2012.

Results

Factors related to caregiver willingness to participate included understanding of the prognosis of dementia, perceptions of feeding needs and clarity about research protocols. Nursing home willingness to participate was influenced by corporate approval, concerns about legal and regulatory issues and prior relationships with investigators.

Conclusion

Participation in rigorous trials requires lengthy navigation of complex corporate requirements and training competent study staff. Objective deliberation by caregivers will depend on appropriate recruitment timing, design of recruitment materials and understanding of study requirements. The clinical standards and policy environment and the secular trends therein have relevance to the responses of people at all levels.

Keywords: Caregiving, decision-making, dementia, nutrition, nursing home care, research in practice

INTRODUCTION

Approximately 5.4 million people in the United States have been diagnosed with some form of dementiaand 96% of these individuals are over the age of 65. By the year 2050, it is expected that the numbers will triple to 11–16 million persons (Alzheimer’s Association 2012). In the UK, as in other areas of Western Europe, a small decline in dementia was recently reported, (prevalence 6.5% of the ≥ 65 year population). This group, however, will continue to have a major impact on services utilized (Matthews et al. 2013). As the disease progresses, care needs increase and persons with dementia (PWD) are often placed in nursing homes (NH) where nearly 67% of dementia related deaths occur (Mitchell et al. 2005).

Weight loss is strongly associated with advanced dementia, which is attributed to the neurodegenerative process and dietary changes (Albanese et al. 2013). Ultimately, family caregivers (or the health care power of attorney) may be faced with the decision to continue hand feeding or place a percutaneous gastrostomy (PEG) tube for nutritional intake (Teno et al. 2011).

BACKGROUND

In the U.S. and Europe, PEG tube placement in PWD continues without high levels of scientific evidence supporting efficacy (Volkert et al. 2006, Garrow et al. 2007) and with great variation by region (Kuo et al. 2009, Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services [CMS] 2011a). This variation is potentially due to physician personal beliefs and knowledge (or lack thereof) regarding outcomes data (Shega et al. 2003), which limits guidance to caregivers to make informed decisions for their loved ones (Teno et al. 2011). Further, caregivers’ perceptions and cultural values influence decision-making (Modi et al. 2010, Watkins et al. 2012).

PEG tubes are often chosen over hand feeding based on misguided beliefs that tube feeding improves wound healing, decreases episodes of aspiration pneumonia and/or increases survival (Shega et al. 2003, Teno et al. 2012). Other factors include higher NH reimbursement for PEG fed residents, patient and physician characteristics (Mitchell et al. 2003, Finucane et al. 2007, Modi et al. 2007) and the climate and norms of the NH (Lopez et al. 2010a). Additionally, as cognitive and functional capacity of the PWD declined and increased adverse health events occurred, transitions between acute and long term care occurred more frequently and often resulted in PEG tube placement (Teno et al. 2009, Kuo et al. 2009). International studies highlighted that residents who had unaddressed feeding deficiencies or were tube fed experienced more adverse health outcomes (Lou et al. 2007).

In view of studies to date, no adequately powered randomized trial to determine the efficacy of feeding methods has been conducted (Garrow et al. 2007, Leeds et al. 2008). Feeding among persons with late-stage dementia, however, is controversial as this vulnerable group lacks the cognitive capacity to articulate their preferences. Furthermore, the provision of food and fluid is culturally-bound, which makes decision-making difficult even when Advance Directives are present (Amella 1999, Hanson et al. 2011). Additionally, the context of the research, in this case the NH, is complex (Watson & Green 2006, Kaasalainen et al. 2010, Colon-Emeric et al. 2010). Thus the design and choice of research methods for rigorous efficacy studies of feeding alternatives are exceptionally challenging.

THE STUDY

Aims

To address the need for a randomized trial to determine feeding method efficacy, a qualitative pilot study of methods to be used in a large clinical trial to determine the efficacy of feeding method was undertaken. This feasibility study, funded by the National Institute on Aging was entitled Feeding in Elderly Late-Stage Dementia: The FIELD Trial. This descriptive case report describes the processes and challenges encountered in the early phases of research. It includes the challenges of: a) engaging caregivers to consider trial participation and b) engaging nursing homes to partner in the study. Given the cultural, ethnic and racial differences in values and traditions related to eating and caregiving, special effort was made to consider racial differences in dynamics related to research participation. Ultimately, for an adequately powered clinical trial to be conducted, the complex professional, organizational and interpersonal factors need explication and consideration. We highlight how these issues could impact the validity of a subsequent trial and how factors related to research priorities may change over-time.

Design

A qualitative cross-sectional design using multiple methods informed this multi-level case study. We investigated caregivers’ perceptions and knowledge about and experience with feeding issues with PWD and participation in research. We also examined their reactions to draft FIELD recruitment materials. We also explored the organizational contextual factors (individual leadership, corporate structure, regulatory level) that were evident in the process of exploring FIELD participation.

Guiding Models

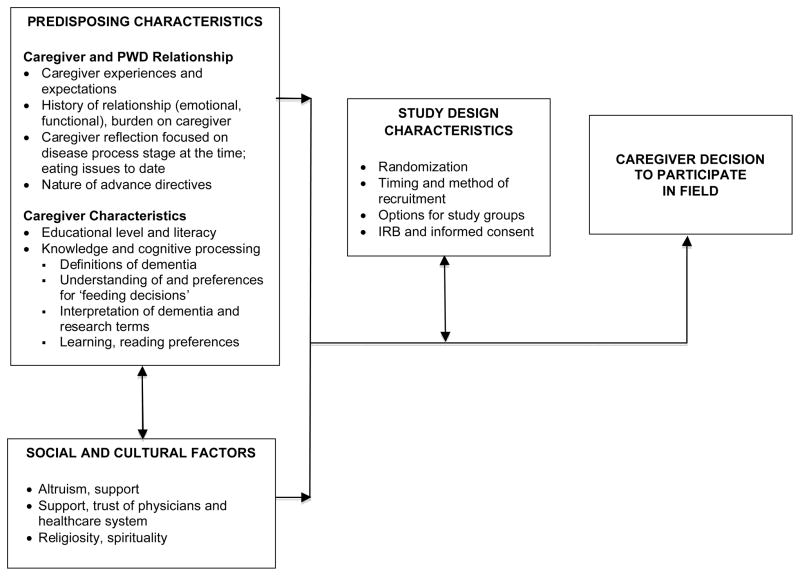

Conceptual frameworks that integrate the theoretical domains of several disciplines are necessary to understand the complex context where research occurs. Based on the Andersen (1995) and Swanson and Ward (1995) models for vulnerable individuals’ willingness to enroll in clinical trials, caregiver focus group analyses considered predisposing characteristics including caregiver and PWD characteristics, knowledge and cognitive processing, as well as social and cultural factors. Reactions to study characteristics were observed (Figure 1).

Figure 1.

Caregiver Decisions to Participate in FIELD

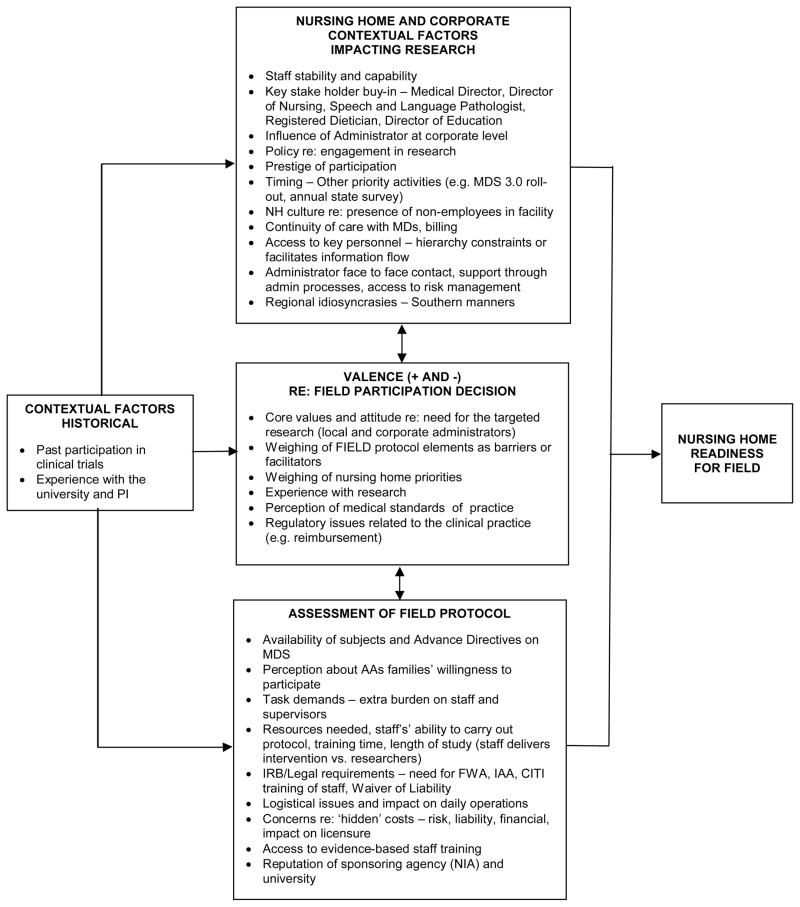

With respect to the potential conduct of efficacy research in nursing homes, there are two broad levels of recruitment: the organizational level - the nursing home and the subject level, in this case the caregiver who is legally authorized to give consent. Within the two levels, there may be additional sub-levels. In the organizational level, there may be administrators, other leadership champions and corporate level decision makers. As our formative work proceeded at the organizational level, we were guided by elements of an organizational readiness for change model (Weiner 2009, Stetler et al. 2009, Zapka et al. 2013). Important inquiry domains included historical contextual factors, nursing home and corporate issues, assessment of elements of the FIELD protocol and change valence (positive and negative factors) having an impact on the participation decision (Figure 2).

Figure 2.

Organizational Readiness for FIELD

Settings and Participants

Focus group participants included adults caring for PWD in their own or at the PWD’s home in South Carolina. Some reported experience with the PWD being in a nursing home. They were recruited with flyers and the assistance of local dementia support group agencies. Additionally, to ensure diverse representation of caregivers who may have different cultural views as well as issues with health literacy, the local Alzheimer’s Association contacted a very rural support group held at a small church. Groups were held in three different geographical areas to explore variations among African Americans and white populations: one each in a rural, a suburban and an urban area. Discussions lasted approximately 2-hoursand participants received an honorarium of a $50 gift card.

Descriptive and retrospective studies of feeding tube performance have been conducted in hospital and nursing home settings (Finucane et al. 1999, Candy et al. 2009). Studies of outcomes related to PWD have largely been done in nursing homes (Hanson et al. 2011). Given enrollment in a prospective trial of feeding methods would need to be attempted when caregivers are at the point of making a decision regarding feeding method, this pilot was conducted in nursing homes. Snowball sampling identified Skilled Nursing Facilities (SNF) in three counties in South Carolina with a sizeable population of residents with dementia. Researchers made initial contact with administrators and other key personnel including Medical Directors, Directors of Nursing and unit managers. Subsequently, frequent communications via face-to-face meetings, telephone and email transpired between the researchers and stakeholders.

Data Collection

Caregiver focus groups were conducted in the usual meeting places of the three community groups. An open-ended protocol reflected main domains of the decision model. The conversations were led by two researchers, digitally recorded and field notes were taken. Open-ended questions were followed by distribution of draft recruitment materials. Five sample flyers each had five sections: 1) information on Alzheimer’s disease and its impact on the brain and feeding in late-stage dementia; 2) general information about the study protocol; 3) currently known risks associated with tube feeding and hand feeding; 4) participant’s rights; and 5) benefit of research participation for caregivers and their loved ones. All flyers were identical in content and layout but differed in the selection of four background pictures; one was blank. Facilitators queried about general impressions, readability and reactions.

Project notes of in-person, telephone and email communication with nursing home staff were maintained by the investigators. The research team entered into conversation with all potential decision-makers including risk management personnel and preferentially used face-to-face contact whenever feasible.

Ethical considerations

After approval by the university’s Institutional Review Board (IRB) the study was initiated. The investigators were cognizant of the emotional elements of caretaking for PWD and care was taken in wording of the questioning protocol. The facilitators were experienced in group process with vulnerable populations and encouraged frankness while creating a supportive environment. Contacts with nursing home staff were initiated to discuss interest in the trial and neither names of nursing homes nor staff were identified.

Data Analysis

A template style of analysis (La Pelle 2004) was used for the focus groups. This content analysis uses a priori categories for categorization (i.e., deductive or theory-driven) formulated by the analyst and derived from researchers’ scholarly and experiential knowledge (Crabtree & Miller 1999). Interview questions reflected the conceptual model (Figure 1). The content of responses was reviewed and an initial list of categories defined (La Pelle 2004, Charmaz 2006). Focus group transcripts were reviewed iteratively for themes by two investigators. The process was repeated with modification of themes with an additional investigator until consensus was reached.

The field notes of NH contacts were reviewed for domains and themes and categorized by two investigators using the readiness model (Figure 2). A third team member reviewed data and validated findings for model fit. Entries that were considered vague or a weak model fit by the first team were then categorized by consensus of all three investigators.

Rigour

Use of organizational and behavioral models guided this work and contributed to credibility of data interpretation. Focus group data were analyzed by two investigators and reviewed by a third. Any variations in interpretation were discussed and consensus reached. Data from study records were interpreted and verified by two investigators. These processes provided consistency and objectivity in identifying themes.

Findings

Participants

Nineteen individuals participated in the caregiver focus groups including 17 women and 4 African Americans. The majority were caregivers to a parent or spouse.

Twelve nursing homes were approached to participate. Ownership varied; two were nonprofit church-affiliated, seven were for-profit corporations, one was a for-profit limited liability corporation, one was government/county owned and one was non-profit corporate owned. Bed sizes ranged from 20–176 licensed beds with a mean of 120 beds; 11 facilities accepted Medicare and nine Medicaid. Overall, Medicare Nursing Home Ratings for the facilities ranged from 2–5 stars with a mean 4 stars (very good) (CMS 2011b). Nineteen staff from the 12 nursing homes engaged in conversations concerning the feasibility of the study; 12 administrators and seven directors (Social Work, Nursing and Dietetics).

Issues related to engaging caregivers

Figure 1 reflects the domains and factors which potentially impact a caregiver’s decision to participate in FIELD and summarizes the content of focus group discussions according to the major domains.

Predisposing characteristics

The influence of predisposing characteristics on potential trial participation was evident. Variability in expectations and experiences of the caregiver and PWD relationship was clearly evident – each had to ‘tell their story.’ Comments suggested that the history and nature of the relationship (e.g. emotional, functional) were related to their perceptions of burden. Caregiver reflection was clearly focused on the stage of disease at the time of the discussion, except for the few participants whose family member had died. In these instances, participants reflected on events immediately preceding death. Frequent comments reflected emotional bonding and the need to respect the loved one’s wishes, particularly when advance directives were in place:

I would prefer not to even see that as a suggestion [participate in a trial], because that might make me want to think that’s what I’m supposed to do and I don’t need any more of that… my mom put it in writing that she didn’t want to be assisted… I wouldn’t even let my dad see this [brochure] with that word on there (tube feeding); that would frighten him… I wouldn’t go against my mother’s wishes.

The participants’ comments highlighted the need for researchers to consider educational level and literacy in the recruitment and implementation protocols. For example, educational level and literacy were apparently related to understanding the progression of dementia and understanding of recruitment materials and aspects of the trial. Frequent comments indicated variation in interpretation of terminology, operational definitions and format:

She has dementia, but Alzheimer’s hasn’t caught up with her yet.

There’s way too much writing [on flyer]. I like the top part, really big lettering. That’s what grabbed me [points to ‘The FIELD Trial’]. This other stuff is way too difficult to read. It took me ten minutes to realize that they all said the same thing. It blew my mind.

While participants agreed to participate in a group talking about PWD and feeding, some participants expressed a view that there were no ‘decisions.’ In other words, a decision implies selecting between at least two alternatives, but some caretakers only viewed one option. A participant from the rural church group viewed the shift from hand feeding to tube insertion as the natural progression rather than a decision:

In my mother-in-law’s case, I don’t see it as a choice. I mean if we chose not to have her tube fed… what would be the alternative be if she refused food?… We’d starve her to death.

Alternatively, there was adamant opposition to tube feeding in the one group conducted in a higher socioeconomic community, but with some counter:

I guess I’m horrified that you all are suggesting that tube feeding may be a better option….

I think it says… whether hand feeding or tube feeding were the better option… I don’t want to be the one sitting down reading the newspaper after letting my husband die thinking that I should have been doing tube feeding.

The review of the print materials illustrated the primacy of pictures to attract attention. In fact, several participants did not notice the text was the same in all the samples —the initial focus was on the colored pictures:

Well, this one shows compassion [picture of younger and older hands]. This one shows someone who cares… a friendly face [picture of an aide smiling encouragingly].

And if you want African American people to volunteer you can have African American hands or people.

Many reported the print material as too ‘busy.’ Acronyms (i.e. FIELD) and scientific terms, while clear to academics, were not necessarily so for the caregivers. For example FIELD Trial was interpreted as a type of research instead of an acronym:

Before you talk about this specific FIELD Trial, you need to talk about field trials in general… what a field trial is, what its purpose is and what is the benefit….

You have five or six different ideas going on. That’s too much to get our attention

[asked what ‘randomization’ meant]. Maybe you let the caregiver pick someone to hand feed your parent. Randomly they’re going to do it on their own and not the researchers….

… the paragraph on ‘Risks Involved’ was not expected… ‘ noted one participant, not digesting the importance of understanding potential risks when consenting to a trial.

A significant lack of understanding of feeding progression itself was exhibited. Sections of the brochure were reported as confusing and reactions extremely varied. Some participants however noted they ‘learned a lot’:

[respondent stops reading]… I can’t deal with blood. I’ll stop here. At Momma’s age, I don’t want to put her through another blood draw.

…the paragraph where is says as people get closer to the end of life they just naturally … stop eating and that doesn’t cause them any discomfort … I didn’t know that … I found it very enlightening.

Social and cultural factors

While many comments could be considered specific to a particular individual, they also reflected more general social and cultural issues and norms. There was occasional reference to potential attitudes of minority participants that have been highlighted in the literature. Members of minority communities have indicated previous experiences along with an overall cautiousness toward research in general (Corbie-Smith et al. 2002, Magwood et al. 2009, McDonald et al. 2012, Green et al. 2013):

‘n the African American community, people are very suspicious…and may think something’s going on and you’re trying to put something over on them. You’re not trying to sugar coat it because it is a trial…trial sounds like a court trial.

Altruism is generally viewed as a prevailing characteristic of many cultures. Altruism can be viewed as supporting participation and retention in a clinical trial where there is no benefit to them personally (Grill & Karlawich 2010). Yet others have argued that reciprocity is connected to all acts of altruism (Mein et al. 2012). However, altruism may not be operating or evident because of burden of caregiving and the nature of dementia and its progression. Caregivers’ concerns appeared two-fold, risk versus benefit for family member [PWD] -- ‘what’s in it for their loved one [PWD]’—and weighing caregiver benefit versus burden because of additional ‘tasks’ or responsibilities. For example, participants questioned why they should agree, given there wasn’t apparent benefit specifically to extending life. Further, when risks were explained, one caregiver verbally emphasized ‘infection’ and viewed the possibility of infection as an added burden:

It’s not that I don’t believe in the feeding tube. It may be ok for a family with a parent …they may want to do the research in order to help the next generation. It’s not me.

Well, I’ve got enough issues with bladder infections with my mom, we’ve had pneumonia twice…I don’t need more health problems…we’re not adding length of life….

Why even study this?…We need to understand how to deal with the issues we’re having now.

Furthermore, caregivers didn’t want to make decisions that could be viewed as harmful; if there is an adverse event, there is then burden of guilt of ‘not taking care of’ a loved one.

Although general cautiousness regarding the FIELD study was expressed, participants indicated they would consider enrolling if the suggestion came from their family member’s physician. In other research, African American participants have emphasized trust of their physician (personal relationship) versus trusting system (Brown 2003). White participants, while appearing not inclined to enroll, also shared that they would consider enrolling if approached by their physician.

Our focus group recruitment process included efforts to include participants with strong spiritual/religious affiliation. There were, however, few related comments (e.g. ‘God in his wisdom deals with this disease’) during discussion.

Study design characteristics

The FIELD study proposed a randomized design. As reported above, there was lack of clarity in operational definitions and some assumptions that the caregiver could choose which treatment the PWD would receive. Difficulty with not understanding dementia and its progression further complicates the decisions about timing for enrollment in an efficacy trial. Simultaneously, there were clear examples of misinterpretation of recruitment materials that will grossly challenge IRB expectations of informed consent. Clear disclosure of risks involved is essential to informed consent, yet the caregiver burden with the PWD condition is overwhelming and request for them to consider more potential risk may be daunting.

Issues related to engaging organizations

Guided by the organizational readiness model, data are reported below categorized by major domains of Figure 2.

Historical context

Factors that were hypothesized to contribute to the organization administrator’s willingness to act as a research site included past experiences with research in the facility and experience with the investigators. Some nursing homes had participated as sites of product trials, but none had participated in a clinical trial. As faculty in a college of nursing, the principal investigator (PI) had a long-standing relationship with one facility as a research site. Additionally, the PI was active in several community groups and state policy-making committees that involved several nursing home administrators so there was some a priori credibility established.

Nursing home and corporate context

Review of interactions elicited numerous comments concerning nursing home and corporate contextual factors that were potential barriers or facilitators to participation in the FIELD trial. Positive comments, interpreted as facilitators, were made about stable and capable staff and observations by administrators that there was buy-in by key stakeholders including the Medical Director, Director of Nursing, Speech and Language Pathologist, Registered Dietician and Director of Education. In the for-profit organizations, obtaining permission at the corporate level was viewed as critical and if positive, was an enormous incentive to move forward. A few administrators mentioned that participation in research was viewed as prestigious; one wished to be involved in manuscript publication.

With respect to barriers, a majority of interviewees indicated that staffing issues, notably staff turnover, was problematic. Several organizations pleaded timing issues as barriers: they were in the midst of Minimum Date Set (MDS) 3.0 roll-out, annual state survey, facility sale, or renovations. One organization had a corporate-level policy that prohibited participation in any research.

An interesting contextual issue we termed ‘getting to no,’ that is, refusal to participate, frequently took several contacts through several mechanisms (planned and ‘drop in’ visits, calls, phone messages and email) over several months’ time. Rather than being direct early on about unwillingness or inability to participate, decisions were delayed for numerous minor reasons and they eventually declined. It was noted that in facilities where there was a longer history of collaboration with the research team, administrators were more forthright about their inability to approve clinical trials.

Assessment of FIELD protocol

Many observations by NH staff about the FIELD protocol ultimately appeared to drive the perceptions about the pluses and minuses of participation. Directors of Nursing were concerned they might not have enough eligible residents who met inclusion criteria, that is, a) residents who did not have some type of Advance Directive since this was completed on admission, or b) residents with profound nutritional compromise whose family would be poised in the near future to make a decision about feeding. They offered opinions that culture or religion of families, especially families of African American residents, could negatively impact the participation decision.

Physicians were concerned about study physician’s involvement in the care of ‘their’ residents and possible billing issues. Some administrators implied a corporate culture of caution of outsiders - they may have been originally interested, but interest was tempered if investigators would be actively present. They were reassured by study protocols that discussed the role of the research team members with resident’s usual care team and described how all procedures would follow the institution’s protocols for use of vendors and billing. Additionally, some were reluctant to participate because additional scrutiny from state and federal agencies would be initiated if they indicated on required CMS paperwork that research was being conducted in their facility. A letter provided by the State Survey and Certification director assured administrators that participation in the study would not affect any survey if all regulations were followed.

Implications of involvement in the trial by institutions that rarely engaged in systematic investigation beyond quality improvement projects raised operational questions. Uniformly, management asked about the task demands. They were concerned about extra burden on staff and supervisors, particularly if there was significant staff turnover. While all resources would be provided including compensation for key staff, several concerns remained, including concerns that staff may not be able to carry out the protocol and would be absent from duties for training and about the length of their commitment to the study (approximately 6-months).

Logistical issues and impact on daily operations were raised. Originally we had planned and budgeted for trained research assistants to assist with feeding the residents. Nursing homes, however, wanted their own staff to be trained to carry out the mealtime protocol, insisting they wanted control over meals and families would not be pleased with research assistants’ feeding, which disrupted sometimes long-standing relationships. Thus, additional in-depth training of all staff would be required to assure fidelity to treatment.

Because none of these agencies had their own IRB, few had any mechanism to review research projects. Since some of their staff would be involved in gathering data for the research (e.g., initial assessment by the speech therapist for safe swallowing and on-site supervision of nursing staff across all shifts for intake records), key staff would be required to be CITI trained. Additionally, due to federal regulations governing the protection of human subjects, agencies were required to obtain a Federal-wide Assurance (FWA), as well as execute an IRB Authorization Agreement (IAA) with the University’s IRB. Despite detailed conversations, this component of research integrity and collaboration with the IRB remained daunting in the eyes of NH administration.

These administrators, however, appreciated access to evidence-based training for their staff by the research team who were experts in the fields of nutrition, gastroenterology and geriatric nursing. Most interviewees cited the reputations of the sponsoring agency, the National Institute on Aging (NIA)and the academic health center as a positive factor.

Valence – pluses and minuses toward decision to participate

With respect to the evaluation of pluses and minuses of participating (valence) in the FIELD trial, there was broad consensus among the local NH administrators and staff of the need to establish the efficacy of feeding modes. No one in any facility, however, brought up the issue of financial incentives which favor tube feeding, (Finucane et al. 2007) perhaps given the social desirability of not appearing cost-focused (Colon-Emeric et al. 2010). However, at the end of the day, interviewees found numerous issues with the protocol and the priorities of their facility.

After at least two meetings and numerous phone calls and emails with each NH, it took almost 24 months to finally come to an agreement with only one of the 12 nursing homes to participate. That administrator had been involved in clinical trials in the past and recognized both the value of participation to his residents, as well as the agency. With this champion, the researchers were able to navigate the agency’s parent organization and engage in dialogue directly with key corporate level decision-makers. A key turning point in the nursing home’s decision to participate was when the University’s General Counsel approved, at the request of the agency’s Risk Manager, the University’s entry into a double waiver of subrogation to limit perceived agency risk and the associated liability of others conducting research among this vulnerable population at the facility. The main conclusion, however, was that a randomized trial in nursing homes would not move forward.

DISCUSSION

This formative work reinforces findings that conducting trials in nursing homes continues to be a major challenge (Kaasalainen et al. 2010, Cohen-Mansfield et al. 2012) especially when the research involves incompetent populations (Karlawish et al. 2009). This is particularly true with studies of patients with a diagnosis that carries emotional and ethical concerns as well as studies which may or may not yield direct benefit to the patient. Staff, notably nurses, is challenged by having sufficient skills for assessing and meeting PWD feeding needs as well as considering the involved ethical issues (Pasman et al. 2003). The findings of our formative study highlight that the challenges are at many levels: the organization, staff, caregivers and affected older adults (Manthorpe & Watson 2003). The findings also illustrate how a priority research question may change over time, highlighting the need to remain cognizant of changing professional norms and public policy around a particular clinical practice or intervention. Our work demonstrated the utility of understanding and applying theoretically based models in research.

Prior to the funding of the study in 2009 there was interest in pursuing a randomized clinical trial to determine efficacy of feeding methods, even though there was plentiful debate about the ethical concerns about artificial nutrition and hydration (Dharmarajan et al. 2001, Garrow et al. 2007, Leeds et al. 2008, Nakaema et al. 2013). The history of the debate results from the complex interplay of ethical concerns, legal changes, public opinion and financial and institutional concerns, including reimbursement by the Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services (Mitchell et al. 2003, Brody et al. 2011, AGS 2013). The discussion about research priorities related to feeding alternatives progressed to focus on informed decision-making about feeding and physician-caregiver communication, rather than demand for a randomized efficacy trial (Carey et al. 2006, Hanson et al. 2011, Teno et al. 2011). This scientific, professional and policy secular trend must be considered in the discussion of our findings. The following observations from our study, however, do have relevance to research in nursing homes in general.

Successful nursing home recruitment will require extensive lead-time for navigating corporate requirements and development of trusting relationships with administrators and staff. Identifying institutional champions and appropriate incentives will be necessary. Organizational core values and culture often predicted the outcome as demonstrated in prior work (Lopez et al. 2010a). Concerns about legal issues, impact on staff resources and conflicting activities were clearly evident in our study and these have been noted in the literature (Finucane et al. 2007). With the particular issues (feeding), concerns about professional norms and regulatory expectations and oversight were highlighted, (Brody et al. 2011). With respect to the FIELD study, particularly the fact that policy supported the promotion of PEG use probably had a major negative effect which would not be evident in other types of studies

Likewise, engaging and recruiting caregivers requires appropriate timing and intensive communication and education. Timing of recruitment in the continuum of disease progression is essential given the caregiver’s own cognitive and emotional processes. This would have required major coordination between investigators and NH clinicians. This point however, may not be just with respect to FIELD, as the limitations of understanding research design was evident. However, the emotional and ethical concerns because of the topic, ‘feeding’, added to the perceived burden and even inappropriate nature of the study. It was seen as an ethical issue of respecting their loved one’s wishes and/or the perception that they would be starving their loved one if the tube was not inserted.

Knowledge and cognitive processing issues were magnified during the caregivers’ review of study materials. Definitions of dementia were dubious for some. For less educated and low literacy participants, comments indicated that feeding issues and practices were not viewed as ‘feeding decisions.’ In one group with more educated and primarily white participant participants, many were totally against PEG tubes. This is a reflection in many research and opinion pieces related to the feeding issue (Gillick 2009).

These knowledge and cognitive processing issues clearly emphasize the need for careful design and pre-testing of caregiver materials. Colorful, well-pictured illustrated recruitment materials must be carefully designed and piloted. Text must be jargon-free and literacy-level appropriate. Communications must be tailored to caregiver needs yet recognize the ethical challenges to be neutral and encourage informed decision-making. This point is important regardless of the research purpose. Attempting to communicate complex issues via written materials alone may not be only ineffective but not desirable in light of caregiver stressors and burden. Investigators must plan for extensive training of recruitment staff and have resources for interpersonal interaction. This has been highlighted as an important issue in the now priority research related to patient-centered care and decision-making.

These issues in turn must consider IRB requirements for explicit details. This seems to lend itself to the debate regarding informed consent – explicit detail does not equate to clarity and in some instances raises inappropriate alarm about participation. Two phases of education may be necessary: first, engaging caregivers to talk with researchers, then extensive explanation of the specific study. Explanation of the criteria of a ‘study’ (rather than ‘trial’) with generalizable findings will be a major challenge given the vivid, opinionated reactions from some contrasted with naïve comments from others. These points apply, no matter what the research question is.

Limitations of the study

The authors acknowledge limitations of this work. Focus group participants were not at the point of actually making a feeding decision. As noted above, there was a tendency for caregivers to ‘think in the moment.’ Additionally, while we recruited a racially and educationally diverse sample, the total sample was small and representative of one region. The recruitment of nursing homes to participate in a pilot study was clearly based on a convenience sample and therefore had limited generalizability.

CONCLUSIONS

If a rigorous efficacy and safety trial is ultimately conducted in the current environment, major methodological challenges will need to be addressed. There is increasing call for investigators to consider the environmental context of the organizations where clinical trials are conducted, as these will ultimately impact the dissemination and adoption of efficacious strategies (Anderson et al. 2005, Kessler & Glasgow 2011, Hendy et al. 2012). Successful recruitment at caregiver, administrator and system levels will require extensive lead time for navigating corporate requirements, the development of trusting relationships, the design of suitable study recruitment materials and the selection of highly trained study staff (Kayser-Jones 2003). Obtaining objective deliberation by caregivers will depend on the timing of the study introduction and recommendation of the primary physician. Context and culture, elements not always addressed in clinical trials, must be made explicit in future work, especially as they highly influence emotionally and ethically charged end-of-life decisions. If professional standards and policies are entrenched, no matter what the efficacy issues, randomized clinical trials are unlikely to be supported. As noted above, the domains of the readiness model are relevant when considering other research studies or other structural and process innovations in health care settings in many international settings.

Relevance to clinical practice

When making decisions for PWD, caregivers need objective guidance from nursing home clinicians including nurses; however there is often misinterpretation of the level of evidence that can be shared with family members who are often the health care proxy for cognitively impaired institutionalized persons (Lopez et al. 2010b). Furthermore, families may misunderstand as nurses discuss options for providing nutritional support with families and offer either ‘comfort care’ or tube feeding. Families need to be offered intensive individualized comfort care that focuses on offering appropriately tailored care focused on symptom management versus ‘only’ comfort, which may be interpreted as ‘doing less’ thus neglecting the individual’s needs (Lopez & Amella 2012). Furthermore, as caregivers make decisions, they need to be informed of choices for clinical trials. Staff, both professional and non-licensed, needs to be educated regarding the consenting process – that it is an ongoing process that is enacted as long as the individual is enrolled. Thus, researchers and staff need to be educated as to ways that actively involve caregivers in consent and cognitively impaired persons who have capacity to assent (Aselage et al. in press) in decision-making. While this may be time and resource intense, in this very vulnerable population to do less would be unethical.

Summary Statement.

Why is this research needed?

To conduct randomized clinical trials in nursing homes, particularly with vulnerable populations such as persons with dementia, it is critical to understand willingness to participate at the organizational, administrative, staff, caregiver and patient levels.

What are the key findings?

Readiness of caregivers to participate in trials requires a lengthy process of education about dementia as well as the methods of research trials.

Caregiver recruitment must include carefully designed educational materials, especially for low literacy individuals.

Nursing home readiness to engage in clinical trials heavily reflects corporate experience and values, addressing technical and potential legal issues and the perceived impact of research activities on daily facility operations.

How should the findings be used to influence policy/research/education?

When readiness to participate is decreased because of regulatory concerns, consideration should be given to vehicles to influence policy.

Nursing home staff education should include evidence based nutrition assessment and feeding skills.

The readiness model and related organizational and behavioral theory have application to other health care organizations in the United States and international settings.

Acknowledgments

Funding statement

This study was funded by The National Institutes of Health National Institute on Aging Research [Grant R21AG032083].

Footnotes

Conflict of Interest statement

No conflict of interest has been declared by the authors.

Author Contributions:

- substantial contributions to conception and design, acquisition of data, or analysis and interpretation of data;

- drafting the article or revising it critically for important intellectual content.

Contributor Information

Jane ZAPKA, Department of Public Health Sciences, Medical University of South Carolina, Charleston, South Carolina, USA.

Elaine J. AMELLA, College of Nursing, Medical University of South Carolina, Charleston, South Carolina, USA.

Gayenell S. MAGWOOD, College of Nursing, Medical University of South Carolina, Charleston, South Carolina, USA.

Mohan MADISETTI, College of Nursing, Medical University of South Carolina, Charleston, South Carolina, USA.

Donald A. GARROW, Gulf Comprehensive Gastroenterology, Englewood, Florida, USA.

Melissa B. ASELAGE, Duke University School of Nursing, Durham, North Carolina, USA.

References

- Albanese E, Taylor C, Siervo M, Stewart R, Prince MJ, Acosta D. Dementia severity and weight loss: A comparison across eight cohorts. The 10/66 study. Alzheimers & Dementia. 2013 doi: 10.1016/j.jalz.2012.11.014. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Alzheimer’s Association. [accessed 03/23/2013];2012 Alzheimer’s Disease Facts and Figures [on-line report] 2012 Retrieved from http://www.alz.org/downloads/facts_figures_2012.pdf.

- Amella EJ. Factors influencing the proportion of food consumed by nursing home residents with dementia. Journal of the American Geriatrics Society. 1999;47(7):879–885. doi: 10.1111/j.1532-5415.1999.tb03849.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- American Geriatrics Society. [Accessed October 12, 2013];Feeding Tubes in Advanced Dementia Position Statement. doi: 10.1111/jgs.12924. www.americangeriatrics.org/files/documents/feeding.tubes.advanced.dement... [DOI] [PubMed]

- Andersen RM. Revisiting the behavioral model and access to medical care: does it matter? Journal of Health and Social Behavior. 1995;36(1):1–10. doi: 10.2307/2137284. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Anderson RA, Crabtree BF, Steele DJ, McDaniel RR., Jr Case study research: the view from complexity science. Qualitative Health Research. 2005;15(5):669–685. doi: 10.1177/1049732305275208. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Aselage M, Amella E, Zapka J, Mueller M, Beck C. Hastings Center Report. Informed consent and assent for persons with dementia in nursing homes. (in press) [Google Scholar]

- Brody H, Hermer LD, Scott LD, Grumbles LL, Kutac JE, McCammon SD. Artificial nutrition and hydration: the evolution of ethics, evidenceand policy. Journal of General Internal Medicine. 26(9):1053–1058. doi: 10.1007/s11606-011-1659-z. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brown DR, Topcu M. Willingness to participate in clinical treatment research among older African Americans and Whites. Gerontologist. 2003;43(1):62–72. doi: 10.1093/geront/43.1.62. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Candy B, Sampson EL, Jones L. Enteral tube feeding in older people with advanced dementia: findings from a Cochrane systematic review. International Journal of Palliative Nursing. 2009;15(8):396–404. doi: 10.12968/ijpn.2009.15.8.43799. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services. Nursing Home Data Compendium 2010 Edition. 2011a Available at: http://www.cms.gov/Medicare/Provider-Enrollment-and-Certification/CertificationandComplianc/Downloads/nursinghomedatacompendium_508.pdf.

- Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services. [accessed 10/12/2012];Nursing Home Compare. 2011b Available at www.medicare.gov/NursingHomeCompare/search.aspx?bhcp=1.

- Charmaz K. Constructing Grounded Theory: A practical guide through qualitative analysis. Newbury Park, CA: Sage; 2006. Gathering Rich Data; pp. 13–42. [Google Scholar]

- Cohen-Mansfield J, Thein K, Marx MS, Dakheel-Ali M. What are the barriers to performing nonpharmacological interventions for behavioral symptoms in the nursing home? Journal of the American Medical Directors Association. 2012;13(4):400–405. doi: 10.1016/j.jamda.2011.07.006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Colon-Emeric CS, Plowman D, Bailey D, Corazzini K, Utley-Smith Q, Ammarell N, Toles M, anderson R. Regulation and mindful resident care in nursing homes. Qualitative Health Research. 2010;20(9):1283–1294. doi: 10.1177/1049732310369337. doi: 1049732310369337. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Corbie-Smith G, Thomas SB, St George DM. Distrust, raceand research. Archives of Internal Medicine. 2002;162(21):2458–2463. doi: 10.1001/archinte.162.21.2458. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Crabtree BF, Miller WL. Doing Qualitative Research. 2. Thousand Oaks, California: Sage Publications; 1999. [Google Scholar]

- Dharmarajan TS, Unnikrishnan D, Pitchumoni CS. Percutaneous endoscopic gastrostomy and outcome in dementia. American Journal of Gastroenterology. 2001;96(9):2556–2563. doi: 10.1111/j.1572-0241.2001.04099.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Finucane TE, Christmas C, Travis K. Tube feeding in patients with advanced dementia: a review of the evidence. Journal of the American Medical Association. 1999;282(14):1365–1370. doi: 10.1001/jama.282.14.1365. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Finucane T, Christmas C, Leff B. Tube feeding in dementia: how incentives undermine health care quality and patient safety. Journal of the American Medical Directors Association. 2007;8(4):205–208. doi: 10.1016/j.jamda.2007.01.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Garrow D, Pride P, Moran W, Zapka J, Amella E, Delegge M. Feeding alternatives in patients with dementia: examining the evidence. Clinical Gastroenterology and Hepatology. 2007;5(12):1372–1378. doi: 10.1016/j.cgh.2007.09.014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Green MA, Kim MM, Barber S, Odulana AA, Godley PA, Howard DL. Connecting communities to health research: Development of the Project CONNECT minority research registry. Contemporary Clinical Trials. 2013 doi: 10.1016/j.cct.2013.01.001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gillick MR. Rethinking the role of tube feeding in patients with advanced dementia. New Englan Journal of Medicine. 2000;342(3):206–210. doi: 10.1056/NEJM200001203420312. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Grill JD, Karlawish J. Addressing the challenges to successful recruitment and retention in Alzheimer’s disease clinical trials. Alzheimer’s Research and Therapy. 2010;2(6):34. doi: 10.1186/alzrt58. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hanson LC, Carey TS, Caprio AJ, Lee TJ, Ersek M, Garrett J. Improving decision-making for feeding options in advanced dementia: a randomized, controlled trial. Journal of the American Geriatrics Society. 2011;59(11):2009–2016. doi: 10.1111/j.1532-5415.2011.03629.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hendy J, Chrysanthaki T, Barlow J, Knapp M, Rogers A, Sanders C. An organizational analysis of the implementation of telecare and telehealth: the whole systems demonstrator. BMC Health Services Research. 2012;12:403. doi: 10.1186/1472-6963-12-403. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kaasalainen S, Williams J, Hadjistavropoulos T, Thorpe L, Whiting S, Neville S, Tremeer J. Creating bridges between researchers and long-term care homes to promote quality of life for residents. Qualitative Health Research. 2010;20(12):1689–1704. doi: 10.1177/1049732310377456. doi: 1049732310377456. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Karlawish J, Rubright J, Casarett D, Cary M, Ten Have T, Sankar P. Older adults’ attitudes toward enrollment of non-competent subjects participating in Alzheimer’s research. American Journal of Psychiatry. 2009;166(2):182–188. doi: 10.1176/appi.ajp.2008.08050645. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kayser-Jones J. Continuing to conduct research in nursing homes despite controversial findings: reflections by a research scientist. Qualitative Health Research. 2003;13(1):114–128. doi: 10.1177/1049732302239414. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kessler R, Glasgow RE. A proposal to speed translation of healthcare research into practice: dramatic change is needed. American Journal of Preventive Medicine. 2011;40(6):637–644. doi: 10.1016/j.amepre.2011.02.023. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kuo S, Rhodes RL, Mitchell SL, Mor V, Teno JM. Natural history of feeding-tube use in nursing home residents with advanced dementia. Journal of the American Medical Directors Association. 2009;10(4):264–270. doi: 10.1016/j.jamda.2008.10.010. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- La Pelle N. Simplifying qualitative data analysis using general purpose software tools. Field Methods. 2004;16(1):85–108. doi: 10.1177/1525822X03259227. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Leeds JS, McAlindon ME, Sanders DS. PEG feeding and dementia-results need to be interpreted with caution. Is this the time for a randomized controlled study? American Journal of Gastroenterology. 2008;103(8):2143. doi: 10.1111/j.1572-0241.2008.01982_1.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lopez RP, Amella EJ, Mitchell S, Stumpf N. Nurses’ perspectives on feeding decisions for nursing home residents with dementia. Journal of Clinical Nursing. 2010a;19:632–638. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2702.2009.03108.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lopez RP, Amella EJ, Strumpf NE, Teno JM, Mitchell SL. The influence of nursing home culture on the use of feeding tubes. Archives of Internal Medicine. 2010b;170(1):83–88. doi: 10.1001/archinternmed.2009.467. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lopez RP, Amella EJ. Intensive individualized comfort care: Making the case. Journal of Gerontological Nursing. 2012;38(7):3–5. doi: 10.3928/00989134-20120605-02. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lou M, Dai Y, Huang G, Yu P. Nutritional status and health outcomes for older people with dementia living in institutions. Journal of Advanced Nursing. 2007;60(5):470–477. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2648.2007.04442.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Magwood GS, andrews JO, Zapka J, Cox MJ, Newman S, Stuart GW. Institutionalization of Community Partnerships: The Challenge for Academic Health Centers. Journal of Health Care for the Poor and Underserved. 2012;23(4):1512–1526. doi: 10.1353/hpu.2012.0161. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Manthorpe J, Watson R. Poorly served? Eating and dementia. Journal of Advanced Nursing. 2003;41(2):162–169. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2648.2003.02520.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Matthews FE, Arthur A, Barnes LE, Bond J, Jagger C, Robinson L, Brayne C. A two-decade comparison of prevalence of dementia in individuals aged 65 and older from three geographical areas of England: results of the Cognitive Function Ageing Study 1 and II. The Lancet. 2013 doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(13)61570-6. http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/S0140-6736(13)61570-6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- McDonald JA, Barg FK, Weathers B, Guerra CE, Troxel AB, Domchek S. Understanding participation by African Americans in cancer genetics research. Journal of the National Medical Association. 2012;104(7–8):324–330. doi: 10.1016/s0027-9684(15)30172-3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mein G, Seale C, Rice H, Johal S, Ashcroft RE, Ellison G. Altruism and participation in longitudinal health research? Insights from the Whitehall II Study. Social Science & Medicine. 2012;75(12):2345–2352. doi: 10.1016/j.socscimed.2012.09.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mitchell SL, Buchanan JL, Littlehale S, Hamel MB. Tube-feeding versus hand-feeding nursing home residents with advanced dementia: a cost comparison. Journal of the American Directors Association. 2003;4(1):27–33. doi: 10.1097/01.JAM.0000043421.46230.0E. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mitchell SL, Teno JM, Miller SC, Mor V. A national study of the location of death for older persons with dementia. Journal of the American Geriatrics Society. 2005;53(2):299–305. doi: 10.1111/j.1532-5415.2005.53118.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Modi S, Whetstone L, Cummings D. Influence of patient and physician characteristics on percutaneous endoscopic gastrostomy tube decision-making. Journal of Palliative Medicine. 2007;10(2):359–366. doi: 10.1089/jpm.2006.0145. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Modi S, Velde B, Gessert CE. Perspectives of community members regarding tube feeding in patients with end-stage dementia: findings from African-American and Caucasian focus groups. Omega (Journal of Death and Dying) 2010;62(1):77–91. doi: 10.2190/OM.62.1.d. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nakaema KE, Cassefo G, Chiba T. Artificial nutrition in old patients dying of dementia. Current Opinion in Supportive and Palliative Care 2013. 2013 Oct 22; doi: 10.1097/SPC.0b013e3283657652. Epub ahead of print. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pasman HR, The BA, Onwuteaka-Philipsen BD, van der Wal G, Ribbe MW. Feeding nursing home patients with severe dementia: a qualitative study. Journal of Advanced Nursing. 2003;42(3):304–311. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2648.2003.02620.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shega JW, Hougham GW, Stocking CB, Cox-Hayley D, Sachs GA. Barriers to Limiting the Practice of Feeding Tube Placement in Advanced Dementia. Journal of Palliative Medicine. 2003;6(6):885–893. doi: 10.1089/109662103322654767. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stetler CB, Ritchie JA, Rycroft-Malone J, Schultz AA, Charns MP. Institutionalizing evidence-based practice: an organizational case study using a model of strategic change. Implementation Science. 2009;4:78. doi: 10.1186/1748-5908-4-78. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Swanson GM, Ward AJ. Recruiting minorities into clinical trials: toward a participant-friendly system. JNCI Journal National Cancer Institute. 1995;87(23):1747–1759. doi: 10.1093/jnci/87.23.1747. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Teno JM, Mitchell SL, Skinner J, Kuo S, Fisher E, Intrator O. Churning: the association between health care transitions and feeding tube insertion for nursing home residents with advanced cognitive impairment. Journal of Palliative Medicine. 2009;12(4):359–362. doi: 10.1089/jpm.2008.0168. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Teno JM, Mitchell SL, Kuo SK, Gozalo PL, Rhodes RL, Lima JC. Decision-making and outcomes of feeding tube insertion: a five-state study. Journal of the American Geriatrics Society. 2011;59(5):881–886. doi: 10.1111/j.1532-5415.2011.03385.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Teno JM, Gozalo P, Mitchell SL, Kuo S, Rhodes R, Bynum J. Does Feeding Tube Insertion and Its Timing Improve Survival? Journal of the American Geriatrics Society. 2012;60(10):1918–1921. doi: 10.1111/j.1532-5415.2012.04148.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Volkert D, Benner YN, Berry E, Lochs H. ESPEN Guidelines for Enteral Nutrition: Geriatrics. Clinical Nutrition. 2006;25(2):330–360. doi: 10.1016/j.clnu.2006.01.012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Watkins YJ, Wilkie DJ, Dancy B, Bonner GJ, Ferrans CE, Wang E. Relationship among trust in physicians, demographicsand end-of-life treatment decisions made by African American dementia caregivers. Journal of Hospice & Palliative Nursing. 2012;14(3):238–243. doi: 10.1097/NJH.0b013e318243920c. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Watson R, Green S. Feeding and dementia: a systematic literature review. Journal of Advanced Nursing. 2006;54(1):86–93. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2648.2006.03793.x. doi: dx.doi.org/10.1111/j.1365-2648.2006.03793.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Weiner BJ. A theory of organizational readiness for change. Implementation Science. 2009;4:67. doi: 10.1186/1748-5908-4-67. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zapka J, Simpson K, Hiott L, Langston L, Fakhry S, Ford D. A mixed methods descriptive investigation of readiness to change in rural hospitals participating in a tele-critical care intervention. BMC Health Services Research. 2013;13:33. doi: 10.1186/1472-6963-13-33. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]