Abstract

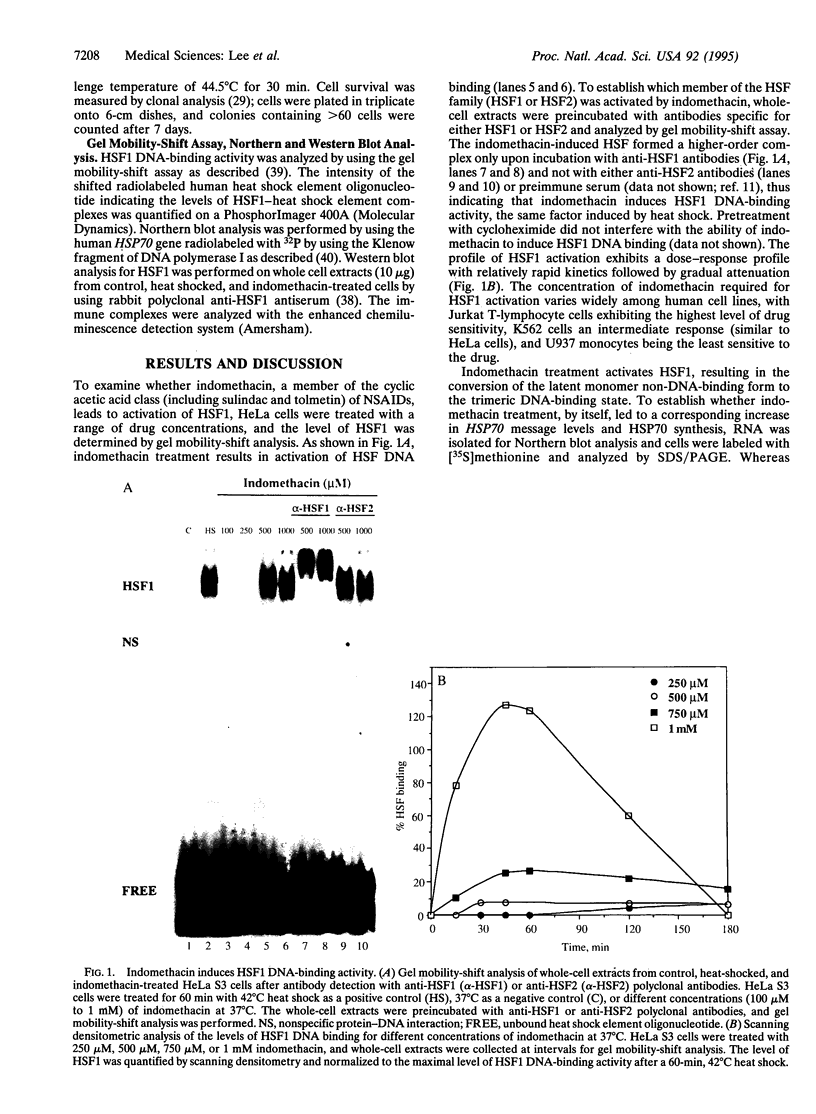

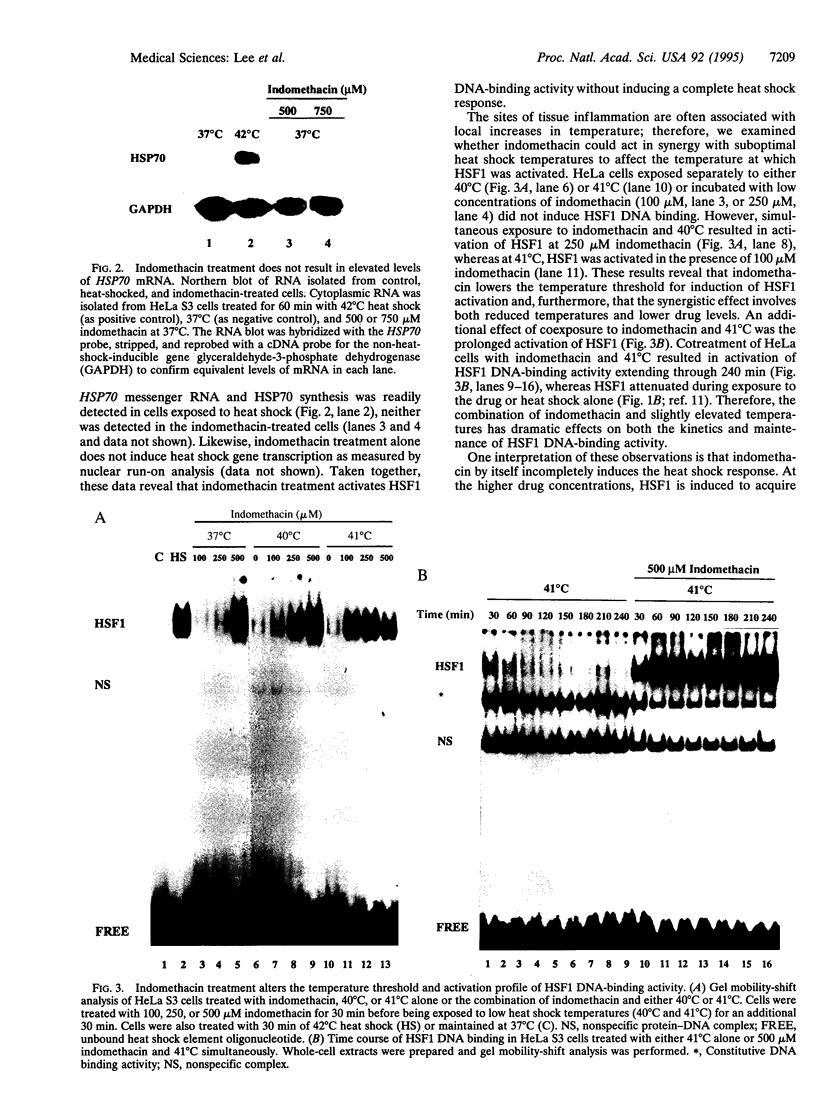

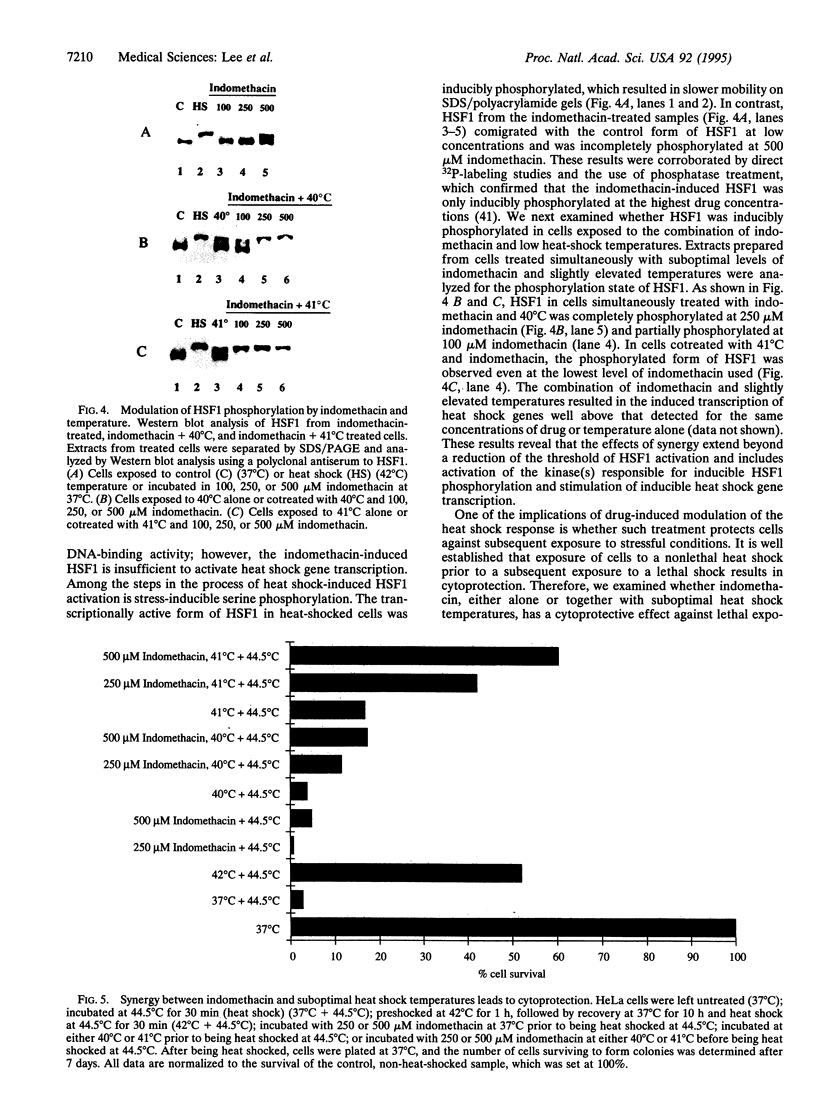

The activation of heat shock genes by diverse forms of environmental and physiological stress has been implicated in a number of human diseases, including ischemic damage, reperfusion injury, infection, neurodegeneration, and inflammation. The enhanced levels of heat shock proteins and molecular chaperones have broad cytoprotective effects against acute lethal exposures to stress. Here, we show that the potent antiinflammatory drug indomethacin activates the DNA-binding activity of human heat shock transcription factor 1 (HSF1). Perhaps relevant to its pharmacological use, indomethacin pretreatment lowers the temperature threshold of HSF1 activation, such that a complete heat shock response can be attained at temperatures that are by themselves insufficient. The synergistic effect of indomethacin and elevated temperature is biologically relevant and results in the protection of cells against exposure to cytotoxic conditions.

Full text

PDF

Images in this article

Selected References

These references are in PubMed. This may not be the complete list of references from this article.

- Abravaya K., Myers M. P., Murphy S. P., Morimoto R. I. The human heat shock protein hsp70 interacts with HSF, the transcription factor that regulates heat shock gene expression. Genes Dev. 1992 Jul;6(7):1153–1164. doi: 10.1101/gad.6.7.1153. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Abravaya K., Phillips B., Morimoto R. I. Attenuation of the heat shock response in HeLa cells is mediated by the release of bound heat shock transcription factor and is modulated by changes in growth and in heat shock temperatures. Genes Dev. 1991 Nov;5(11):2117–2127. doi: 10.1101/gad.5.11.2117. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Angelidis C. E., Lazaridis I., Pagoulatos G. N. Constitutive expression of heat-shock protein 70 in mammalian cells confers thermoresistance. Eur J Biochem. 1991 Jul 1;199(1):35–39. doi: 10.1111/j.1432-1033.1991.tb16088.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Baler R., Dahl G., Voellmy R. Activation of human heat shock genes is accompanied by oligomerization, modification, and rapid translocation of heat shock transcription factor HSF1. Mol Cell Biol. 1993 Apr;13(4):2486–2496. doi: 10.1128/mcb.13.4.2486. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Benjamin I. J., Horie S., Greenberg M. L., Alpern R. J., Williams R. S. Induction of stress proteins in cultured myogenic cells. Molecular signals for the activation of heat shock transcription factor during ischemia. J Clin Invest. 1992 May;89(5):1685–1689. doi: 10.1172/JCI115768. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Blake M. J., Udelsman R., Feulner G. J., Norton D. D., Holbrook N. J. Stress-induced heat shock protein 70 expression in adrenal cortex: an adrenocorticotropic hormone-sensitive, age-dependent response. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 1991 Nov 1;88(21):9873–9877. doi: 10.1073/pnas.88.21.9873. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Clerget M., Polla B. S. Erythrophagocytosis induces heat shock protein synthesis by human monocytes-macrophages. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 1990 Feb;87(3):1081–1085. doi: 10.1073/pnas.87.3.1081. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Craig E. A., Gambill B. D., Nelson R. J. Heat shock proteins: molecular chaperones of protein biogenesis. Microbiol Rev. 1993 Jun;57(2):402–414. doi: 10.1128/mr.57.2.402-414.1993. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Currie R. W., Tanguay R. M., Kingma J. G., Jr Heat-shock response and limitation of tissue necrosis during occlusion/reperfusion in rabbit hearts. Circulation. 1993 Mar;87(3):963–971. doi: 10.1161/01.cir.87.3.963. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Georgopoulos C., Welch W. J. Role of the major heat shock proteins as molecular chaperones. Annu Rev Cell Biol. 1993;9:601–634. doi: 10.1146/annurev.cb.09.110193.003125. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gething M. J., Sambrook J. Protein folding in the cell. Nature. 1992 Jan 2;355(6355):33–45. doi: 10.1038/355033a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hendrick J. P., Hartl F. U. Molecular chaperone functions of heat-shock proteins. Annu Rev Biochem. 1993;62:349–384. doi: 10.1146/annurev.bi.62.070193.002025. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jurivich D. A., Sistonen L., Kroes R. A., Morimoto R. I. Effect of sodium salicylate on the human heat shock response. Science. 1992 Mar 6;255(5049):1243–1245. doi: 10.1126/science.1546322. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jurivich D. A., Sistonen L., Sarge K. D., Morimoto R. I. Arachidonate is a potent modulator of human heat shock gene transcription. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 1994 Mar 15;91(6):2280–2284. doi: 10.1073/pnas.91.6.2280. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jättelä M., Wissing D., Bauer P. A., Li G. C. Major heat shock protein hsp70 protects tumor cells from tumor necrosis factor cytotoxicity. EMBO J. 1992 Oct;11(10):3507–3512. doi: 10.1002/j.1460-2075.1992.tb05433.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kaufmann S. H., Schoel B., van Embden J. D., Koga T., Wand-Württenberger A., Munk M. E., Steinhoff U. Heat-shock protein 60: implications for pathogenesis of and protection against bacterial infections. Immunol Rev. 1991 Jun;121:67–90. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-065x.1991.tb00823.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kopp E., Ghosh S. Inhibition of NF-kappa B by sodium salicylate and aspirin. Science. 1994 Aug 12;265(5174):956–959. doi: 10.1126/science.8052854. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Langer T., Lu C., Echols H., Flanagan J., Hayer M. K., Hartl F. U. Successive action of DnaK, DnaJ and GroEL along the pathway of chaperone-mediated protein folding. Nature. 1992 Apr 23;356(6371):683–689. doi: 10.1038/356683a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Li G. C., Li L., Liu R. Y., Rehman M., Lee W. M. Heat shock protein hsp70 protects cells from thermal stress even after deletion of its ATP-binding domain. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 1992 Mar 15;89(6):2036–2040. doi: 10.1073/pnas.89.6.2036. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lindquist S., Craig E. A. The heat-shock proteins. Annu Rev Genet. 1988;22:631–677. doi: 10.1146/annurev.ge.22.120188.003215. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lis J., Wu C. Protein traffic on the heat shock promoter: parking, stalling, and trucking along. Cell. 1993 Jul 16;74(1):1–4. doi: 10.1016/0092-8674(93)90286-y. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Luce M. C., Cristofalo V. J. Reduction in heat shock gene expression correlates with increased thermosensitivity in senescent human fibroblasts. Exp Cell Res. 1992 Sep;202(1):9–16. doi: 10.1016/0014-4827(92)90398-r. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Malamy J., Carr J. P., Klessig D. F., Raskin I. Salicylic Acid: a likely endogenous signal in the resistance response of tobacco to viral infection. Science. 1990 Nov 16;250(4983):1002–1004. doi: 10.1126/science.250.4983.1002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Martin J., Horwich A. L., Hartl F. U. Prevention of protein denaturation under heat stress by the chaperonin Hsp60. Science. 1992 Nov 6;258(5084):995–998. doi: 10.1126/science.1359644. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mestril R., Chi S. H., Sayen M. R., O'Reilly K., Dillmann W. H. Expression of inducible stress protein 70 in rat heart myogenic cells confers protection against simulated ischemia-induced injury. J Clin Invest. 1994 Feb;93(2):759–767. doi: 10.1172/JCI117030. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Morimoto R. I. Cells in stress: transcriptional activation of heat shock genes. Science. 1993 Mar 5;259(5100):1409–1410. doi: 10.1126/science.8451637. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mosser D. D., Theodorakis N. G., Morimoto R. I. Coordinate changes in heat shock element-binding activity and HSP70 gene transcription rates in human cells. Mol Cell Biol. 1988 Nov;8(11):4736–4744. doi: 10.1128/mcb.8.11.4736. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rabindran S. K., Haroun R. I., Clos J., Wisniewski J., Wu C. Regulation of heat shock factor trimer formation: role of a conserved leucine zipper. Science. 1993 Jan 8;259(5092):230–234. doi: 10.1126/science.8421783. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sanchez Y., Taulien J., Borkovich K. A., Lindquist S. Hsp104 is required for tolerance to many forms of stress. EMBO J. 1992 Jun;11(6):2357–2364. doi: 10.1002/j.1460-2075.1992.tb05295.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sarge K. D., Murphy S. P., Morimoto R. I. Activation of heat shock gene transcription by heat shock factor 1 involves oligomerization, acquisition of DNA-binding activity, and nuclear localization and can occur in the absence of stress. Mol Cell Biol. 1993 Mar;13(3):1392–1407. doi: 10.1128/mcb.13.3.1392. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schröder H., Langer T., Hartl F. U., Bukau B. DnaK, DnaJ and GrpE form a cellular chaperone machinery capable of repairing heat-induced protein damage. EMBO J. 1993 Nov;12(11):4137–4144. doi: 10.1002/j.1460-2075.1993.tb06097.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Siegel M. I., McConnell R. T., Cuatrecasas P. Aspirin-like drugs interfere with arachidonate metabolism by inhibition of the 12-hydroperoxy-5,8,10,14-eicosatetraenoic acid peroxidase activity of the lipoxygenase pathway. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 1979 Aug;76(8):3774–3778. doi: 10.1073/pnas.76.8.3774. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sistonen L., Sarge K. D., Phillips B., Abravaya K., Morimoto R. I. Activation of heat shock factor 2 during hemin-induced differentiation of human erythroleukemia cells. Mol Cell Biol. 1992 Sep;12(9):4104–4111. doi: 10.1128/mcb.12.9.4104. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Skowyra D., Georgopoulos C., Zylicz M. The E. coli dnaK gene product, the hsp70 homolog, can reactivate heat-inactivated RNA polymerase in an ATP hydrolysis-dependent manner. Cell. 1990 Sep 7;62(5):939–944. doi: 10.1016/0092-8674(90)90268-j. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Udelsman R., Blake M. J., Stagg C. A., Li D. G., Putney D. J., Holbrook N. J. Vascular heat shock protein expression in response to stress. Endocrine and autonomic regulation of this age-dependent response. J Clin Invest. 1993 Feb;91(2):465–473. doi: 10.1172/JCI116224. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Westwood J. T., Clos J., Wu C. Stress-induced oligomerization and chromosomal relocalization of heat-shock factor. Nature. 1991 Oct 31;353(6347):822–827. doi: 10.1038/353822a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Westwood J. T., Wu C. Activation of Drosophila heat shock factor: conformational change associated with a monomer-to-trimer transition. Mol Cell Biol. 1993 Jun;13(6):3481–3486. doi: 10.1128/mcb.13.6.3481. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wu B., Hunt C., Morimoto R. Structure and expression of the human gene encoding major heat shock protein HSP70. Mol Cell Biol. 1985 Feb;5(2):330–341. doi: 10.1128/mcb.5.2.330. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]