Abstract

AIM: To investigate the effectiveness of phenol for the relief of cancer pain by endoscopic ultrasound-guided celiac plexus neurolysis (EUS-CPN).

METHODS: Twenty-two patients referred to our hospital with cancer pain from August 2009 to July 2011 for EUS-CPN were enrolled in this study. Phenol was used for 6 patients with alcohol intolerance and ethanol was used for 16 patients without alcohol intolerance. The primary endpoint was the positive response rate (pain score decreased to ≤ 3) on postoperative day 7. Secondary endpoints included the time to onset of pain relief, duration of pain relief, and complication rates.

RESULTS: There was no significant difference in the positive response rate on day 7. The rates were 83% and 69% in the phenol and ethanol groups, respectively. Regarding the time to onset of pain relief, in the phenol group, the median pre-treatment pain score was 5, whereas the post-treatment scores decreased to 1.5, 1.5, and 1.5 at 2, 8, and 24 h, respectively (P < 0.05). In the ethanol group, the median pre-treatment pain score was 5.5, whereas the post-treatment scores significantly decreased to 2.5, 2.5, and 2.5 at 2, 8, and 24 h, respectively (P < 0.01). There was no significant difference in the duration of pain relief between the phenol and ethanol groups. No significant difference was found in the rate of complications between the 2 groups; however, burning pain and inebriation occurred only in the ethanol group.

CONCLUSION: Phenol had similar pain-relieving effects to ethanol in EUS-CPN. Comparing the incidences of inebriation and burning pain, phenol may be superior to ethanol in EUS-CPN procedures.

Keywords: Celiac plexus neurolysis, Celiac plexus blockade, Endoscopic ultrasound, Phenol, Pain management, Upper gastrointestinal cancer

Core tip: We compared the pain-relieving effect and complications between endoscopic ultrasound-guided celiac plexus neurolysis (EUS-CPN) using phenol on patients intolerant to alcohol and ethanol on patients without alcohol intolerance. Phenol had similar pain-relieving effects to ethanol; using phenol can avoid burning pain and inebriation complications. To date, few data regarding phenol-based EUS-CPN exist, and it is generally believed that phenol has a slightly slower onset and shorter duration of action than ethanol. Consequently, phenol is not routinely used in EUS-CPN. However, approximately half of East Asians lack mitochondrial aldehyde dehydrogenase activity, which causes alcohol intolerance. Our data provide evidence on phenol-based EUS-CPN for patients with alcohol intolerance.

INTRODUCTION

Abdominal pain is a common problem in patients with upper gastrointestinal cancer and often affects both quality of life and survival[1]. Pain is present in as many as 70% to 80% of patients at the time of pancreatic cancer diagnosis[2,3]. Although pain can be well controlled in the majority of cancer patients with conventional analgesics, it can be difficult to treat and patients may suffer from drug-related side effects[4]. In these patients, celiac plexus neurolysis (CPN) may be indicated[3]. Endoscopic ultrasound-guided CPN (EUS-CPN) was developed in 1996, and its use has become quite widespread because it is theoretically safer than posterior percutaneous CPN, as EUS provides detailed imaging of the blood vessels and other organs[5]. EUS-CPN has been reported to relieve pain in 51%-89% of patients[5-8].

The 2 neurolytic agents commonly used to permanently destroy the celiac plexus are ethanol and phenol[9]. Ethanol causes the immediate precipitation of endoneural lipoproteins and mucoproteins within the celiac plexus, leading to the extraction of cholesterol and phospholipids from the neural membrane[10]. Phenol achieves neurolysis similar to that achieved with ethanol by causing protein coagulation and necrosis of neural structures. Although there are limited data comparing ethanol and phenol, it is generally considered that ethanol causes greater neural destruction[10].

The absence of aldehyde dehydrogenase (ALDH2) causes alcohol intolerance. ALDH2 is a major contributor to alcohol sensitivity and drinking behavior in East Asians[11,12]. Approximately half of East Asian populations, including the Japanese, lack mitochondrial ALDH2 activity, which is responsible for the oxidation of acetaldehyde. Persons with deficient ALDH2 activity show rapid and intense flushing of the face and symptoms of mild-to-moderate intoxication after drinking alcohol in an amount that has no effect on Caucasoids[13]. In these patients, ethanol is contraindicated for CPN and phenol is used as an alternative. However, phenol is not routinely used in these circumstances, and there are few data regarding CPN using phenol[10].

In this study, we compared the differences in pain-relieving effect and complications associated with ethanol and phenol use in EUS-CPN.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Patients

Twenty-four patients referred to our hospital who received EUS-guided pain therapy using ethanol or phenol between August 2009 and July 2011 were eligible for inclusion. EUS-CPN had been performed for patients with epigastric pain caused by upper abdominal neoplasms and graded 4 or higher on the Numeric Rating Scale (NRS), in which 0 indicates no pain and 10 indicates the worst pain ever experienced. Of these, 2 patients were excluded as they had received a previous CPN that could affect cancer-related pain. The remaining 22 patients were enrolled in this study. Relevant data were retrieved from the medical records at our institution. The protocol of the present study was approved by the institutional review boards of the Sapporo Medical University and registered with the UMIN Clinical Trials Registry (number: UMIN000008129). Informed consent for the procedure was obtained from all patients.

Treatment allocation

In August 2009, we performed EUS-CPN using phenol for the first time on a patient with alcohol intolerance. As of July 2011, we had performed EUS-CPN using phenol on 6 patients with alcohol intolerance. During the same period, we performed EUS-CPN using ethanol on 16 patients without alcohol intolerance. The diagnosis of alcohol intolerance was established by an alcohol patch test[14]. Therefore, during the same time period, this study compared the pain-relieving effect and complications between EUS-CPN using phenol on patients intolerant to alcohol and ethanol on patients without alcohol intolerance.

EUS-CPN

EUS-CPN was performed under conscious sedation [i.v. injection of diazepam (5-10 mg) and pethidine hydrochloride (50 mg)] by 1 of 2 experienced endosonographers (H. I. and T. H.) using a linear-array echo endoscope (GF-UCT240; Olympus, Tokyo, Japan). CPN was performed utilizing a sterile 22-gauge needle system (Echo-Tip; Wilson-Cook Medical, Winston-Salem, NC, United States). Using an echo endoscope, the aorta was identified at the level of the diaphragm in the posterior lesser curve of the gastric fundus, and traced in a sagittal plane to the celiac trunk. The celiac plexus was targeted based on its expected anatomical position relative to the position of the celiac trunk. The needle was inserted around the celiac trunk via a transgastric approach under EUS guidance. In this study, 2 CPN techniques [i.e., central CPN and celiac ganglia neurolysis (CGN)] were performed based on the endosonographer’s choice. Our techniques were similar to those described previously[5,8,15]. To prevent severe transient pain after the procedure, 1-2 mL of 0.5% bupivacaine was injected before the ethanol injection; however, local anesthetic was not injected before the phenol injection because it has been reported that phenol has an immediate local anesthetic effect[10].

Neurolytic agents

We used 7% phenol in water and absolute ethanol as neurolytic agents. In percutaneous CPN, ethanol has been used with a total dose of 40-60 mL and phenol has been used with doses of 20-25 mL[16]. In contrast, in EUS-CPN, ethanol has been used with a total dose of 10-20 mL in previous studies; however, the optimal dose of phenol has not been reported[6]. Therefore, in this study, in terms of the amount of neurolytic agent, we used phenol in the same way as ethanol. In all patients, the total amount of neurolytic agent injected did not exceed 20 mL.

Pain scores and data collection

All patients undergoing EUS-CPN routinely filled out pre- and post-treatment pain score questionnaires with the aid of a nurse, who was blinded to the type of neurolytic agent used. Most patients are hospitalized for more than 7 d after procedures related to the diagnosis and treatment of cancer. Patient interviews were conducted in the patient’s unit and post-treatment questionnaires were obtained 2, 8, and 24 h after the procedure and every day up to 1 wk after the procedure. Thereafter, nearly all of these patients were continuously followed at an outpatient clinic in our hospital for 2-4 wk by a physician (other than the endosonographer who performed the EUS-CPN), and the pain score was measured during the patient interview. Pain levels reflected the strongest pain experienced during each interval. When the pain score increased to ≥ 4, thereby requiring the initiation of narcotic use or a narcotic agent dose increase, follow-up was terminated, as this reflected a loss of pain relief.

Complications

Complications were defined as any procedural side effect treated in any capacity beyond standard observation.

Outcome parameters

The primary endpoint was the positive response rate on postoperative day 7. Positive response was defined as a pain score decreased to ≤ 3 on postoperative day 7. Secondary endpoints included the time to onset of pain relief, duration of pain relief, and complication rates. To evaluate the time to onset of pain relief in each group, before and after pain scores were compared in both the phenol and ethanol groups. The post-treatment scores were evaluated at 2, 8, and 24 h after the procedure. The definition of the duration of pain relief was from the date of the EUS-CPN procedure until the day the pain score increased to ≥ 4.

Statistical analysis

Categorical variables were compared with Fisher’s exact test. Continuous variables are presented as the median (with a range) and were compared using the Mann-Whitney U-test. The NRS values before and after the procedure were compared using the Wilcoxon signed-rank test. The Kaplan-Meier method was used to compare the duration of pain relief between the phenol and ethanol groups. Patients who had not experienced an exacerbation of daily pain graded as ≥ 4 on the NRS were censored on the date of death. A 2-tailed P value of < 0.05 was considered significant. Statistical analyses were performed with SPSS (version 19.0; IBM, Tokyo, Japan).

RESULTS

Patient characteristics

Patient characteristics are shown in Table 1. There were no significant differences between the 2 groups with respect to the following variables: age, gender, type of primary tumor, cancer treatment, direct invasion of the celiac plexus, preoperative pain score, or history of narcotic use. No significant difference was found in the CPN procedure used or in the total amount of neurolytic agent used between the 2 groups.

Table 1.

Patient characteristics and endoscopic ultrasound-guided celiac plexus neurolysis -related data

| Phenol | Ethanol | P value | |

| Number of patients | 6 | 16 | |

| Age (yr) [median (range)] | 63 (52-74) | 71 (47-83) | 0.396 |

| Gender (n) [male/female] | 2/4 | 7/9 | 1 |

| Primary site (n) | 1 | ||

| Pancreas/other | 5/1 | 12/4 | |

| Treatment (n) | 0.090 | ||

| CRT/CT/NT | 2/3/1 | 0/11/5 | |

| Direct invasion of celiac plexus (n) | 1 | 7 | 0.350 |

| NRS before CPN [median (range)] | 5.0 (4-7) | 5.5 (4-8) | 0.472 |

| History of narcotic use (n) | 1 | 11 | 0.056 |

| EUS-CPN technique | 0.330 | ||

| Central/CGN | 3/3 | 4/12 | |

| Total amount of neurolytic agent (mL) [median (range)] | 18.0 (13-20) | 13.0 (3.5-20) | 0.085 |

EUS-CPN: Endoscopic ultrasound-guided celiac plexus neurolysis; NRS: Numeric Rating Scale; CRT: Chemoradiotherapy; CT: Chemotherapy; NT: No therapy; CGN: Celiac ganglia neurolysis.

Pain relief

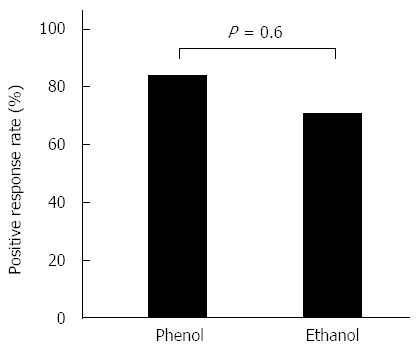

There was no significant difference in the positive response rate on day 7 between the phenol and ethanol groups. The positive response rate was 83% (5 of 6 cases) in the phenol group and 69% (11 of 16 cases) in the ethanol group (Figure 1).

Figure 1.

Positive response rate on day 7. The positive response rate was 83% in the phenol group and 69% in the ethanol group.

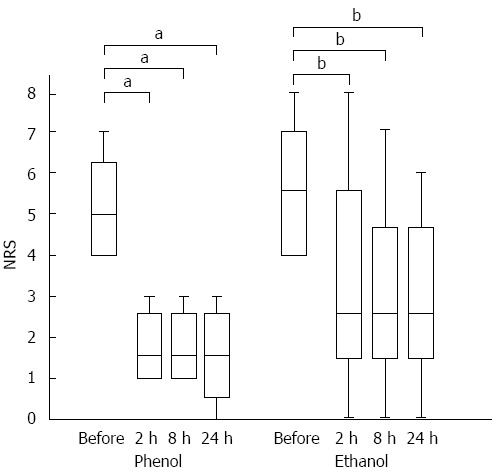

Regarding the time to the onset of pain relief, the NRS scores at 2, 8, and 24 h after the procedure were lower than the scores before the procedure in both groups. In the phenol group, the median NRS scores before the procedure and at 2, 8, and 24 h after the procedure were 5, 1.5, 1.5, and 1.5, respectively (P < 0.05). The equivalent median scores in the ethanol group were 5.5, 2.5, 2.5, and 2.5, respectively (P < 0.01) (Figure 2).

Figure 2.

Time to the onset of pain relief in each group. A box-plot of pre- and post-endoscopic ultrasound-guided celiac plexus neurolysis pain scores. The first and third quartiles are represented by the ends of the box, the median is indicated by the horizontal line in the interior of the box, and the maximum and minimum values are at the ends of the whiskers. In each group, the pain score was decreased at 2 h after the procedure. The statistical analysis is based on the Wilcoxon signed-rank test. NRS: Numeric Rating Scale. aP < 0.05 vs control; bP < 0.01 vs control.

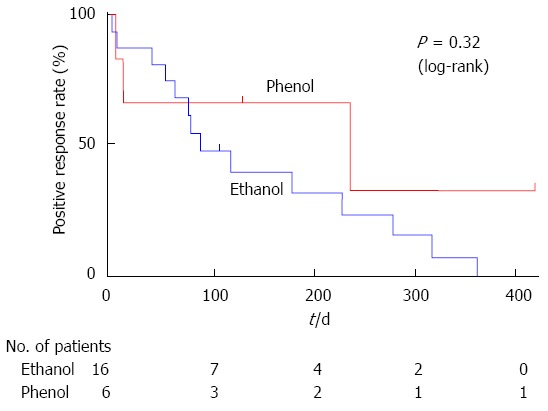

No significant difference was found in the duration of pain relief between the phenol and ethanol groups, as compared using a log-rank test (Figure 3). Referring to Figure 2, 5 of the 22 patients were censored because of death without an exacerbation of pain (3, phenol; 2, ethanol); however, none of these patients were lost to follow-up. The median duration of pain relief was 237 d in the phenol group and 90 d in the ethanol group.

Figure 3.

A Kaplan-Meier analysis of the duration of pain relief. There was no significant difference in the duration of pain relief between endoscopic ultrasound-guided celiac plexus neurolysis using phenol and ethanol, as compared using a log-rank test.

Complications

Complications developed in 7 patients: 1 in the phenol group and 6 in the ethanol group (16.7% vs 37.5%; P = 0.62). Diarrhea occurred after the procedure in 2 patients (1 patient from each group), but improved within 3 d. Burning pain occurred after the procedure in 2 patients in the ethanol group. This was treated with analgesics at a rescue dose and disappeared within 24 h. Inebriation occurred in 2 patients in the ethanol group, but they recovered within 24 h. During the procedure, transient hypotension also occurred in 1 patient in the ethanol group. However, hypotension was alleviated within 24 h with fluid replacement.

DISCUSSION

To date, phenol has been used clinically in CPN, but no study has made a detailed evaluation of the efficacy of phenol. Descriptions of phenol use have been noted only in some review articles[10,16]. To our knowledge, our results represent the first retrospective observational study of CPN using phenol. In the current study, we describe the efficacy of phenol as a neurolytic agent in EUS-CPN, and reveal that it has a similar pain-relieving effect to ethanol. Similar to ethanol, phenol has neuro-destructive properties; however, it is generally believed that phenol has a slightly slower onset of action[10]. Therefore, to confirm the time to onset of pain relief, we evaluated pain scores before and after EUS-CPN. In the phenol group, the pain score had already decreased 2 h after the procedure; this result was the same as that in the ethanol group. Our results reveal that EUS-CPN using phenol also sufficiently achieves prompt pain-relieving effects within 2 h after the procedure, at the latest.

It is also generally considered that ethanol causes more neural destruction than phenol and that phenol has a shorter duration of action than ethanol[10]. Our results reveal that in comparison to ethanol, phenol has a similar effect on day 7 after the procedure, and the effect is long lasting. In the Kaplan-Meier analysis, the rate of censoring because of death without an exacerbation of pain was 12.5% in the ethanol group and 50% in the phenol group. This observation may also show that phenol has a long-lasting effect, and suggests that the efficacy of phenol should be reconsidered in a prospective, randomized, controlled trial.

In many studies, adding a local anesthetic agent to ethanol has been recommended to prevent burning pain after CPN using ethanol; however, it is generally considered that the burning pain associated with ethanol injection does not occur with phenol because it has an immediate local anesthetic effect[10]. The rate has been reported to be 3.4%-34% in previous studies using ethanol with a local anesthetic[15,17]. In our study, the rate of burning pain in the ethanol group was 13%; burning pain did not occur in the phenol group, even though a local anesthetic agent was not added. Additionally, inebriation did not occur in the phenol group. Inebriation occurred after the procedure in 2 patients (13%) in the ethanol group. Because Japanese patients have a lower ability to metabolize alcohol than Caucasoid patients, this complication often occurs in Japanese patients during EUS-CPN using ethanol[12]. Our results showed that using phenol can avoid burning pain and inebriation complications, and may therefore confer some advantages over ethanol.

The main limitation of this study is its small sample size. Our sample size was too small to definitively verify a statistical difference. Thus, this study is regarded as a pilot study. Another limitation is that the current study was not a randomized, comparative study. Phenol injection was performed only for patients with alcohol intolerance. In addition, the rate of the tumor invasion to the celiac trunk, which has been reported to be related to a negative CPN response, was 17% in the phenol group; however, the rates reported in the EUS-CPN literature are higher (42.6%-47.1%)[17-19]. This difference may result in the high positive response rate in the phenol group. Given these limitations, our study should be seen as a pilot study providing preliminary data regarding the pain-relieving effect and safety of EUS-CPN using phenol for cancer-related pain.

In conclusion, our preliminary data suggest that phenol has a similar pain-relieving effect to ethanol. In terms of the incidences of inebriation and burning pain, phenol may be superior to ethanol in CPN.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

We wish to thank Wataru Jomen, MD; Yutaka Okagawa, MD; Kaoru Ono, MD; Fumito Tamura, MD; and Ikumi Umeda, MD for their assistance with data collection.

COMMENTS

Background

Pancreatic cancer commonly causes pain that is difficult to control. Endoscopic ultrasound-guided celiac plexus neurolysis (EUS-CPN) is often employed to improve pain and quality of life while reducing drug-related side effects. Ethanol is a neurolytic agent commonly used to permanently destroy the celiac plexus. However, approximately half of East Asians lack mitochondrial aldehyde dehydrogenase activity, which causes alcohol intolerance. In these patients, ethanol is contraindicated for CPN and phenol is used as an alternative. However, few data regarding phenol-based EUS-CPN exist.

Research frontiers

There is no detailed analysis regarding CPN using phenol. However, it is generally believed that phenol has a slightly slower onset and shorter duration of action than ethanol.

Innovations and breakthroughs

To date, descriptions of phenol use have been noted only in some review articles. This results represent the first retrospective observational study of CPN using phenol. In the current study, the authors describe the efficacy of phenol as a neurolytic agent in EUS-CPN, and reveal that it has a similar pain-relieving effect to ethanol.

Applications

The current study showed that phenol-based EUS-CPN had a good pain relieving effect for alcohol-intolerant cancer patients. To date, phenol has not been routinely used in these patients. Therefore, this data will encourage the use of phenol in EUS-CPN for alcohol-intolerant patients with cancer pain.

Terminology

Phenol is a volatile aromatic organic compound with the molecular formula C6H5OH and is a white, crystalline solid. It once was widely used as an antiseptic, particularly in carbolic soap. Phenol derivatives are also used in the preparation of cosmetics, including sunscreens, hair colorings, and skin lightening preparations. In medical use, phenol is used as a neurolytic agent and can be injected intrathecally and epidurally.

Peer review

Dr. Ishiwatari et al presented the use of phenol as an injectate in EUS-CPN as an alternative to ethanol. The technique is original and it has not been reported previously, thus increasing the value and interest of the study findings.

Footnotes

P- Reviewer: Baghbanian M, Fusaroli P, Shah OJ S- Editor: Qi Y L- Editor: A E- Editor: Ma S

References

- 1.Johnson CD, Davis CL. Pain relief in upper abdominal malignancy. Hepatobiliary Pancreat Dis Int. 2006;5:330–333. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Wong GY, Schroeder DR, Carns PE, Wilson JL, Martin DP, Kinney MO, Mantilla CB, Warner DO. Effect of neurolytic celiac plexus block on pain relief, quality of life, and survival in patients with unresectable pancreatic cancer: a randomized controlled trial. JAMA. 2004;291:1092–1099. doi: 10.1001/jama.291.9.1092. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Yan BM, Myers RP. Neurolytic celiac plexus block for pain control in unresectable pancreatic cancer. Am J Gastroenterol. 2007;102:430–438. doi: 10.1111/j.1572-0241.2006.00967.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Collins D, Penman I, Mishra G, Draganov P. EUS-guided celiac block and neurolysis. Endoscopy. 2006;38:935–939. doi: 10.1055/s-2006-944734. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Wiersema MJ, Wiersema LM. Endosonography-guided celiac plexus neurolysis. Gastrointest Endosc. 1996;44:656–662. doi: 10.1016/s0016-5107(96)70047-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Puli SR, Reddy JB, Bechtold ML, Antillon MR, Brugge WR. EUS-guided celiac plexus neurolysis for pain due to chronic pancreatitis or pancreatic cancer pain: a meta-analysis and systematic review. Dig Dis Sci. 2009;54:2330–2337. doi: 10.1007/s10620-008-0651-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Sakamoto H, Kitano M, Kamata K, Komaki T, Imai H, Chikugo T, Takeyama Y, Kudo M. EUS-guided broad plexus neurolysis over the superior mesenteric artery using a 25-gauge needle. Am J Gastroenterol. 2010;105:2599–2606. doi: 10.1038/ajg.2010.339. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Sahai AV, Lemelin V, Lam E, Paquin SC. Central vs. bilateral endoscopic ultrasound-guided celiac plexus block or neurolysis: a comparative study of short-term effectiveness. Am J Gastroenterol. 2009;104:326–329. doi: 10.1038/ajg.2008.64. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Noble M, Gress FG. Techniques and results of neurolysis for chronic pancreatitis and pancreatic cancer pain. Curr Gastroenterol Rep. 2006;8:99–103. doi: 10.1007/s11894-006-0004-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Mercadante S, Nicosia F. Celiac plexus block: a reappraisal. Reg Anesth Pain Med. 1998;23:37–48. doi: 10.1016/s1098-7339(98)90109-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Goedde HW, Harada S, Agarwal DP. Racial differences in alcohol sensitivity: a new hypothesis. Hum Genet. 1979;51:331–334. doi: 10.1007/BF00283404. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Harada S, Agarwal DP, Goedde HW. Aldehyde dehydrogenase deficiency as cause of facial flushing reaction to alcohol in Japanese. Lancet. 1981;2:982. doi: 10.1016/s0140-6736(81)91172-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Goedde HW, Agarwal DP, Harada S, Meier-Tackmann D, Ruofu D, Bienzle U, Kroeger A, Hussein L. Population genetic studies on aldehyde dehydrogenase isozyme deficiency and alcohol sensitivity. Am J Hum Genet. 1983;35:769–772. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Higuchi S, Muramatsu T, Saito M, Sasao M, Maruyama K, Kono H, Niimi Y. Ethanol patch test for low Km aldehyde dehydrogenase deficiency. Lancet. 1987;1:629. doi: 10.1016/s0140-6736(87)90267-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Levy MJ, Topazian MD, Wiersema MJ, Clain JE, Rajan E, Wang KK, de la Mora JG, Gleeson FC, Pearson RK, Pelaez MC, et al. Initial evaluation of the efficacy and safety of endoscopic ultrasound-guided direct Ganglia neurolysis and block. Am J Gastroenterol. 2008;103:98–103. doi: 10.1111/j.1572-0241.2007.01607.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Wang PJ, Shang MY, Qian Z, Shao CW, Wang JH, Zhao XH. CT-guided percutaneous neurolytic celiac plexus block technique. Abdom Imaging. 2006;31:710–718. doi: 10.1007/s00261-006-9153-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Doi S, Yasuda I, Kawakami H, Hayashi T, Hisai H, Irisawa A, Mukai T, Katanuma A, Kubota K, Ohnishi T, et al. Endoscopic ultrasound-guided celiac ganglia neurolysis vs. celiac plexus neurolysis: a randomized multicenter trial. Endoscopy. 2013;45:362–369. doi: 10.1055/s-0032-1326225. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Iwata K, Yasuda I, Enya M, Mukai T, Nakashima M, Doi S, Iwashita T, Tomita E, Moriwaki H. Predictive factors for pain relief after endoscopic ultrasound-guided celiac plexus neurolysis. Dig Endosc. 2011;23:140–145. doi: 10.1111/j.1443-1661.2010.01046.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.De Cicco M, Matovic M, Bortolussi R, Coran F, Fantin D, Fabiani F, Caserta M, Santantonio C, Fracasso A. Celiac plexus block: injectate spread and pain relief in patients with regional anatomic distortions. Anesthesiology. 2001;94:561–565. doi: 10.1097/00000542-200104000-00006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]