Abstract

BRCA1-mutated breast cancer is associated with basal-like disease; however, it is currently unclear if the presence of a BRCA1 mutation depicts a different entity within this subgroup. In this study, we compared the molecular features among basal-like tumors with and without BRCA1 mutations. Fourteen patients with BRCA1-mutated (nine germline and five somatic) tumors and basal-like disease, and 79 patients with BRCA1 non-mutated tumors and basal-like disease, were identified from the cancer genome atlas dataset. The following molecular data types were evaluated: global gene expression, selected protein and phospho-protein expression, global miRNA expression, global DNA methylation, total number of somatic mutations, TP53 and PIK3CA somatic mutations, and global DNA copy-number aberrations. For intrinsic subtype identification, we used the PAM50 subtype predictor. Within the basal-like disease, we observed minor molecular differences in terms of gene, protein, and miRNA expression, and DNA methylation variation, according to BRCA1 status (either germinal or somatic). However, there were significant differences according to average number of mutations and DNA copy-number aberrations, and four amplified regions (2q32.2, 3q29, 6p22.3, and 22q12.2), which are characteristic in high-grade serous ovarian carcinomas, were observed in both germline and somatic BRCA1-mutated breast tumors. These results suggest that minor, but potentially relevant, baseline molecular features exist among basal-like tumors according to BRCA1 status. Additional studies are needed to better clarify if BRCA1 genetic status is an independent prognostic feature, and more importantly, if BRCA1 mutation status is a predictive biomarker of benefit from DNA-damaging agents among basal-like disease.

Electronic supplementary material

The online version of this article (doi:10.1007/s10549-014-3056-x) contains supplementary material, which is available to authorized users.

Keywords: Basal-like, BRCA1, Intrinsic subtype, Breast cancer

Introduction

Studies based on gene expression data have identified and characterized four main intrinsic subtypes of breast cancer (luminal A, luminal B, HER2-enriched, and basal-like) [1, 2]. Among them, the basal-like subtype is associated with young age, BRCA1 germline and somatic mutations [1, 3, 4] and an overall poor prognosis despite that a subgroup of patients with these tumors has an excellent outcome when treated with chemotherapy [5]. In the clinical setting, basal-like tumors are usually identified by the lack of expression of hormone receptors by immunohistochemistry (IHC) and lack of overexpression of HER2 by IHC and/or FISH (the so called triple-negative [TN] status) [1, 2, 6]. Although the TN definition enriches for basal-like disease, considerable discordance exists [2, 6].

BRCA1 mutations and other associated molecular traits might confer sensitivity to specific therapeutic agents [7–10]. Nevertheless, it is unclear how different, from a biological perspective, BRCA1-mutated basal-like tumors are from BRCA1 non-mutated basal-like tumors, and whether BRCA1 mutation is an independent prognostic and/or predictive biomarker when the intrinsic subtype is taken into account [11–15]. This line of thought directed us to formulate the question of how much the biology of basal-like tumors with BRCA1 mutations differs from the biology of basal-like tumors without BRCA1 mutations. To address this question, we interrogated The Cancer Genome Atlas (TCGA) breast cancer project which provides various types of molecular data coming from DNA, RNAs, and proteins [1].

Methods

The Cancer Genome Atlas dataset

In this study, we evaluated TCGA breast cancer dataset and all data were obtained from the TCGA breast cancer online portal (https://tcga-data.nci.nih.gov/docs/publications/brca_2012/). The following files were used. For microarray gene expression data: “BRCA.exp.547.med.txt.” For reverse-phase protein array (RPPA) expression data: “rppaData-403Samp-171Ab-Trimmed.txt.” For sequencing miRNA expression: “BRCA.780.mimat.txt.” For microarray DNA methylation variation: “BRCA.methylation.27 k.450 k.txt.” For microarray DNA copy-number aberration data: “brca_scna_all_thresholded.by_genes.txt.” For intrinsic subtype identification, we used the PAM50 subtype calls as provided in the TCGA portal.

Independent dataset

We evaluated an independent and publicly available microarray-based gene expression dataset (GSE40115) that includes breast tumors from 32 patients with basal-like disease (20 with BRCA1 germline mutations and 12 with sporadic tumors [i.e. unknown BRCA1 status]). The file “GSE40115-GPL15931_series_matrix.txt” with the normalized log2 ratios (Cy5 sample/Cy3 control) of probes was used. Probes mapping to the same gene (Entrez ID as defined by the manufacturer) were averaged to generate independent expression estimates.

Seven-TN subtype classification

To identify the 7-TN subtypes described by Lehmann et al. [16], (i.e., basal one, basal two, immunomodulatory, luminal androgen receptor, mesenchymal, mesenchymal stem cell, and unstable), we submitted the raw gene expression data of each individual dataset of basal-like disease to the TNBC type online predictor (http://cbc.mc.vanderbilt.edu/tnbc/) [17].

Statistical analysis

All multiple-testing comparisons were done using an unpaired two-class significance analysis of microarrays (SAM, http://www-stat.stanford.edu/~tibs/SAM/). The mutation rates of TP53 and PIK3CA genes between two groups, the 7-TN subtype distribution between BRCA1-mutated and non-mutated basal-like tumors, and the amplification rates of ID4 between two groups, were compared using the Chi square and Fisher’s exact tests. The total number of somatic mutations between two groups was compared using a Student’s t test. All statistical computations were performed in R v.2.15.1 (http://cran.r-project.org).

Results and discussion

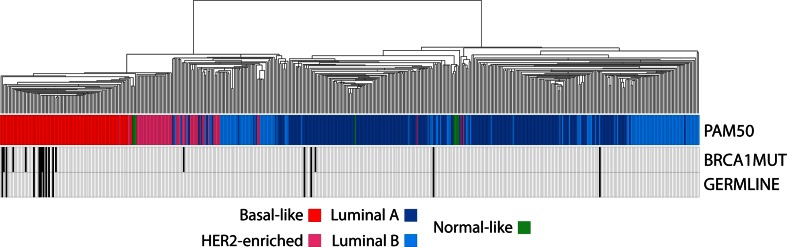

From TCGA breast cancer dataset, we identified 12 tumor samples with BRCA1 germline mutations (all classified as deleterious), seven tumor samples with somatic BRCA1 mutations, and one tumor sample with both BRCA1 germline and somatic mutations (Supplemental Material). As expected, 70 % of BRCA1 mutated tumors where of the basal-like intrinsic subtype (nine germline and five somatic), but luminal A (two germline, one germline/somatic, and one somatic), luminal B (one germline), and HER2-enriched (one somatic) tumors were also identified (Fig. 1 ). Similarly, 66.7 % of BRCA1 mutated tumors were TN.

Fig. 1.

Intrinsic profile of BRCA1-mutated breast tumors. Hierarchical clustering of 509 breast samples of the cancer genome atlas (TCGA) project using the ~1,900 intrinsic gene list [30]. PAM50 intrinsic subtype calls [30] and BRCA1 mutation status is shown below the array tree

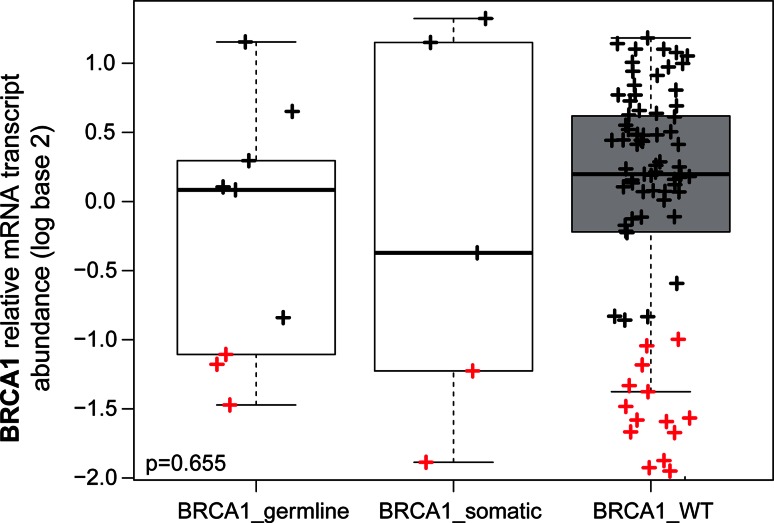

Within basal-like disease, we observed minor molecular differences (0–1.1 %) in terms of gene expression, protein expression, miRNA expression, and DNA methylation variation according to BRCA1 status (Table 1 and Supplemental Material). Indeed, no genes among 17,876 genes were found differentially expressed between basal-like BRCA1-mutated tumors versus basal-like BRCA1 non-mutated tumors (Table 1), including the BRCA1 mRNA transcript (Fig. 2). Similar results were observed when only the tumors with BRCA1 germline mutations were taken into consideration (Supplemental Material). Concordant with this result, analysis of microarray gene expression data of an independent dataset of 32 tumors with basal-like disease (20 with a BRCA1 germline mutation and 12 with sporadic tumors) revealed only 0.03 % differentially expressed genes (6 of 21,848, false discovery rate [FDR] = 0 %) between the two groups [18] (Supplemental Material). In addition, we did not identify significant differences in the proportion of the recently reported 7-TN subtype classification proposed by Lehmann and colleagues [16], between basal-like tumors with and without BRCA1 mutations (Supplemental Material). Interestingly, two clear groups within the basal-like BRCA1 wild-type disease were identified based on BRCA1 mRNA expression-only (i.e., high and low) (Fig. 2).

Table 1.

Significant molecular differences between basal-like BRCA1-mutated tumors (n = 14) and basal-like BRCA1 non-mutated tumors (n = 79)

| Total biomarkers evaluated | Type of evaluation | Comparison (more expressed or amplified) | Significant biomarkers identified (FDR = 0 %) | Percentage of altered biomarkers (%) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 17,786 (unique genes) | Expression | BRCA1MUT | 0 | 0 |

| BRCA1WT | 0 | |||

| 171 (unique proteins or phospho-proteins by RPPA) | Expression | BRCA1MUT | 0 | 0.6 |

| BRCA1WT | 1 | |||

| 1,222 (mature/star miRNA strands) | Expression | BRCA1MUT | 3 | 0.2 |

| BRCA1WT | 0 | |||

| 530 (unique genes) | Methylation | BRCA1MUT | 0 | 1.1 |

| BRCA1WT | 6 | |||

| 19,613 (unique genes) | DNA amplification | BRCA1MUT | 250 | 1.3 |

| BRCA1WT | 0 |

RPPA reverse-phase protein arrays, FDR false discovery rate BRCA1WT BRCA1 wild-type, BRCA1MUT BRCA1 mutated

Fig. 2.

Relative BRCA1 gene expression in basal-like disease based on BRCA1 mutational status. Data have been obtained from the TCGA breast cancer project. The BRCA1 gene expression has been median centered across all breast cancer samples with DNA-seq data (i.e., basal-like and not basal-like). The p-value was calculated by comparing gene expression means across the three groups. In red color, breast samples with ≥2-fold decrease in BRCA1 expression compared to its median expression in breast cancer are shown

In terms of DNA copy-number aberrations, we identified 250 genes (representing 14 different DNA regions and 1.3 % of all genes evaluated) showing higher amplification rates in basal-like BRCA1-mutated tumors compared to basal-like BRCA1 wild-type tumors (Table 2). Among them, we identified four regions (2q32.2, 3q29, 6p22.3, and 22q11.2) that have been previously shown to be amplified and characteristic of high-grade serous ovarian carcinomas [19]. Interestingly, region 6p22.3 contains ID4, a gene long known to be a marker of basal-like breast cancers [20], and known to code for a DNA-binding protein that negatively regulates BRCA1 expression in breast and ovarian cancers [21]. This gene was found amplified (i.e. low or high gains) in 78.6 % (11/14) of basal-like BRCA1 mutated tumors versus 35.1 % (26/74) of basal-like BRCA1 wild-type tumors (p = 0.008, Fisher’s exact test). Similar results were observed when the BRCA1 somatic mutations were excluded (Supplemental Material). The biological role of ID4 amplification in BRCA1 mutated breast cancer is currently unknown, and we could hypothesize that ID4 might inhibit residual function of mutant BRCA1.

Table 2.

DNA regions found significantly more amplified in basal-like BRCA1-mutated tumors (n = 14) compared to basal-like BRCA1 non-mutated tumors (n = 74)

| Basal-like BRCA1 mutated | HGSOC | Genes |

|---|---|---|

| 6p22.3 | 6p22.3 | FAM65B, TDP2, ACOT13, ALDH5A1, GPLD1, KIAA0319, MRS2, C6orf62, GMNN, DCDC2, CMAHP, KAAG1, KIF13A, DEK, NRSN1, E2F3, MBOAT1, RNF144B, CDKAL1, KDM1B, NHLRC1, TPMT, ID4, HDGFL1, PRL, LINC00340, SOX4, CAP2, FAM8A1, NUP153, RBM24, MYLIP, GMPR, ATXN1, DTNBP1, JARID2 |

| 3q29 | 3q29 | FYTTD1, KIAA0226, DLG1, BDH1, LOC220729, CEP19, LOC152217, MFI2, NCBP2, PAK2, PIGX, PIGZ, SENP5, ACAP2, ANKRD18DP, FAM157A, LMLN, IQCG, LRCH3, C3orf43, FBXO45, LRRC33, RNF168, UBXN7, WDR53, APOD, MUC20, MUC4, OSTalpha, PCYT1A, PPP1R2, SDHAP1, SDHAP2, TCTEX1D2, TFRC, TM4SF19, TNK2, ZDHHC19, XXYLT1, FAM43A, LSG1, TMEM44, RPL35A, ATP13A3, ATP13A4, ATP13A5, CPN2, GP5, HES1, HRASLS, LOC100128023, LOC100131551, LRRC15, MB21D2, MGC2889, OPA1 |

| 2q32.2 | 2q32.2 | COL3A1, COL5A2, DIRC1, NAB1, TMEM194B, C2orf88, GLS, HIBCH, INPP1, MFSD6, MSTN, STAT4, SLC40A1, WDR75, ORMDL1, OSGEPL1, PMS1, ANKAR, ASNSD1, STAT1 |

| 22q12.2 | 22q12.2 | AP1B1, ASCC2, CABP7, CCDC157, DEPDC5, DRG1, DUSP18, EIF4ENIF1, EMID1, EWSR1, GAL3ST1, GAS2L1, GATSL3, HORMAD2, INPP5 J, LIF, LIMK2, MORC2, MORC2-AS1, MTFP1, MTMR3, NEFH, NF2, NIPSNAP1, OSBP2, OSM, PATZ1, PES1, PIK3IP1, PISD, PLA2G3, PRR14L, RASL10A, RFPL1, RFPL1-AS1, RHBDD3, RNF185, RNF215, SDC4P, SEC14L2, SEC14L3, SEC14L4, SELM, SF3A1, SFI1, SLC35E4, SMTN, SNORD125, TBC1D10A, TCN2, THOC5, TUG1, UQCR10, ZMAT5 |

| 10q25.3 | – | TRUB1, CASP7, ATRNL1,FAM160B1, PDZD8, SLC18A2, C10orf96, C10orf81, DCLRE1A, HABP2, NHLRC2, NRAP, KCNK18, KIAA1598, VAX1, GFRA1, PNLIP, PNLIPRP1, PNLIPRP2, PNLIPRP3, C10orf82, HSPA12A, ADRB1, AFAP1L2, C10orf118, TDRD1, VWA2, ABLIM1 |

| 10q26.11 | – | PRLHR, FAM204A, BAG3, INPP5F, TIAL1, C10orf46, MCMBP, SEC23IP, CASC2, EMX2, EMX2OS, RAB11FIP2, EIF3A, FAM45A, GRK5, NANOS1, PRDX3, RGS10, SFXN4, SNORA19 |

| 22q11.22 | – | GGTLC2, GNAZ, LOC648691, LOC96610, POM121L1P, PPM1F, PRAME, RAB36, RTDR1, TOP3B, VPREB1, ZNF280A, ZNF280B |

| 22q11.23 | – | ADORA2A, BCR, BCRP3, C22orf13, C22orf15, C22orf43, C22orf45, CABIN1, CHCHD10, CRYBB2, CRYBB3, DDT, DDTL, DERL3, FAM211B, GGT1, GGT5, GSTT1, GSTT2, GSTTP1, GSTTP2, GUSBP11, IGLL1, IGLL3P, KIAA1671, LOC391322, LRP5L, MIF, MMP11, PIWIL3, POM121L10P, POM121L9P, RGL4, SGSM1, SLC2A11, SMARCB1, SNRPD3, SPECC1L, SUSD2, TMEM211, TOP1P2, UPB1, VPREB3, ZDHHC8P1, ZNF70 |

| 22q12.1 | – | ADRBK2, ASPHD2, C22orf31, CCDC117, CHEK2, CRYBA4, CRYBB1, HPS4, HSCB, KREMEN1, MIAT, MN1, MYO18B, PITPNB, SEZ6L, SRRD, TFIP11, TPST2, TTC28, TTC28-AS1, XBP1, ZNRF3 |

| 22q12.3 | – | C22orf24, C22orf42, SLC5A1, YWHAH, BPIFC, C22orf28, FBXO7, RFPL2, RFPL3, RFPL3-AS1, SLC5A4, SYN3, APOL5, APOL6, HMOX1, MB, MCM5, RASD2,TOM1, TIMP3, CACNG2, IFT27, PVALB, NCF4, C1QTNF6, C22orf33, CSF2RB, IL2RB, KCTD17, MPST, TMPRSS6, TST, ISX, HMGXB4, LARGE, APOL3, RBFOX2, EIF3D, FOXRED2, TXN2, APOL1, MYH9, APOL2, APOL4 |

| 2q32.1 | – | ZSWIM2, ZNF804A, FAM171B, ITGAV, GULP1, CALCRL, TFPI, ZC3H15, DNAJC10, DUSP19, NUP35, FRZB, NCKAP1, PDE1A |

| 2q33.2 | – | CTLA4, ICOS, CD28, RAPH1, FAM117B, ICA1L, ABI2, ALS2CR8, WDR12, CYP20A1, NBEAL1 |

| 3q28 | – | CCDC50, FGF12, OSTN, PYDC2, UTS2D, CLDN1, CLDN16, GMNC, IL1RAP, LEPREL1, SNAR-I, TMEM207, TP63, TPRG1 |

| 6p21.31 | – | NUDT3, C6orf1, HMGA1, BAK1, GGNBP1, LINC00336, ANKS1A, C6orf126, C6orf127, C6orf81, CLPS, FKBP5, GRM4, LHFPL5, LOC285847, SCUBE3, SNRPC, SRPK1, TAF11, TCP11, UHRF1BP1, SLC26A8, C6orf125, IP6K3, ITPR3, LEMD2, MLN, RPL10A, TEAD3, TULP1, ZNF76, C6orf106, PACSIN1, RPS10, SPDEF, BRPF3, C6orf222, MAPK13, MAPK14, PNPLA1, DEF6, FANCE, PPARD, ETV7, PXT1, KCTD20, SRSF3, STK38 |

HGSOC high-grade serous ovarian carcinoma

In terms of somatic gene mutations, basal-like BRCA1 mutated tumors showed higher average number of mutations than basal-like BRCA1 wild-type tumors (122.6 vs. 80.3, p = 0.004, Student’s t test). Regarding the distribution of TP53 and PIK3CA somatic mutations according to BRCA1 status, TP53 mutations were found in 100 % (14/14) of basal-like BRCA1 mutated versus 75.9 % (60/79) of basal-like BRCA1 wild-type tumors (p = 0.065, Fisher’s exact test). Finally, PIK3CA mutations were found in 0 % (0/14) of basal-like BRCA1 mutated tumors versus 10.1 % (8/79) of basal-like BRCA1 wild-type tumors (p = 0.602).

In our analysis, most of the unique molecular features of basal-like BRCA1 mutated tumors were found at the DNA level (i.e. amplifications and mutation rates). Indeed, basal-like BRCA1 mutated tumors showed higher amplification rates at 14 different chromosomal regions and higher number of somatic mutations, including TP53, compared to basal-like BRCA1 wild-type tumors. However, no significant differences in protein expression were found when comparing basal-like BRCA1 mutated and BRCA1 wild-type tumors. These results suggest that the genomic instability induced by BRCA1 loss [22] does not translate into a recognizable phenotype at the RNA and protein level. The potential explanation of these findings is currently unknown. Nonetheless, the fact that 4 out of 14 (28.5 %) amplified DNA regions were found to be characteristic regions of high-grade serous ovarian carcinomas suggests that, among basal-like breast tumors, those with a BRCA1 mutation are more similar to ovarian carcinoma at the genetic level.

In our analysis, the absence of recognizable prominent differences in molecular alterations based on BRCA1 mutation status would be in line with previous clinical data suggesting that BRCA1 status per se might not play a major role in conferring a distinct prognosis within basal-like disease. Results from three retrospective studies that have evaluated the prognostic role of BRCA1/2 mutations (mostly BRCA1) in TN breast cancer support this hypothesis [13–15]. In Bayraktar et al. [13], BRCA1/2 status was not found to be prognostic in 227 women with early TN breast cancer referred to genetic counseling. Similar results were observed in a cohort of 195 patients with metastatic breast cancer, where the independent prognostic value of BRCA1 in univariate analyses was lost when TN status and other clinical-pathological variables were taken into account [14]. More recently, Huzarski et al. [15] evaluated the association of germline BRCA1 mutation status with 10 year overall survival in 3,350 polish women with a diagnosis of breast cancer. The authors observed that BRCA1 mutation status was significantly associated with worse outcome when standard clinical-pathological variables were taken into account [15]. However, among patients with TN breast cancer, BRCA1 status was not associated with worse outcome [15].

The role of the BRCA1 mutation status as a predictive factor of treatment response among TN breast cancer is also under study. On the one hand, two retrospective studies have evaluated the ability of BRCA1 mutation status to predict response to multi-agent chemotherapy [11, 12]. In the first study, Arun and colleagues showed no significant differences in terms of pathological complete response rates after neoadjuvant chemotherapy (mostly anthracycline/taxane-based) among 75 patients with TN breast cancer in relation to their BRCA1 status [11]. In the second study, Gonzalez-Angulo et al. [12] observed a better outcome in BRCA1/2 mutated TN breast cancer compared to BRCA1/2 non-mutated TN breast cancers after treatment with adjuvant anthracycline/taxane-based chemotherapy. On the other hand, two recent prospective clinical trials (GeparSixto [23] and CALGB40603 [24]) have demonstrated the value of adding carboplatin, a DNA-damaging agent, to standard neoadjuvant anthracycline/taxane-based chemotherapy in 769 patients with newly diagnosed TN breast cancer, regardless of their BRCA1 mutational status.

Previous retrospective studies have suggested that BRCA1 mutated tumors might substantially benefit from platinum [9, 25]. In fact, in the GeparSixto TN trial [23, 26], recent data reported higher pCR rates in BRCA1/2-mutated patients compared to BRCA1/2 non-mutated patients. Nevertheless, data on the intrinsic subtype of the TN wild-type tumors in this clinical trial have not been reported yet and it might be interesting to analyze whether the basal-like benefits the most. Supporting the hypothesis that basal-like BRCA1 non-mutated breast cancers might also benefit to some extent from DNA-damaging agents, several studies have identified BRCA1 mutation-unrelated mechanisms of platinum sensitivity in TN BRCA1 wild-type breast cancer such as the p63/p73 network, telomeric allelic imbalance, and homologous recombination deficiency [27–29].

Conclusions

In this study, we compared DNA, RNA, and protein data among basal-like tumors with and without BRCA1 mutations and observed that minor molecular features exist. The clinical relevance of these differences is unknown and further validation in larger and prospective cohorts is warranted. Biomarker analyses are needed to clarify if BRCA1 status is an independent prognostic feature and/or a predictive biomarker of benefit from DNA-damaging agents beyond the basal-like phenotype.

Electronic supplementary material

Below is the link to the electronic supplementary material.

Acknowledgments

Beca Roche en Onco-Hematología 2012

Conflict of interest

C.M.P is an equity stock holder, and Board of Director Member, of BioClassifier LLC and University Genomics. C.M.P is also listed an inventor on a patent application on the PAM50 molecular assay. Uncompensated advisory role of A.P. for Nanostring Technologies.

Abbreviations

- TN

Triple-negative

- BRCA1

Breast cancer 1 early onset

- ID4

Inhibitor of DNA binding 4, dominant negative helix-loop-helix protein

- PIK3CA

Phosphatidylinositol-4, 5-bisphosphate 3-kinase, catalytic subunit alpha

Footnotes

Aleix Prat and Cristina Cruz have contributed equally to this work.

Contributor Information

Aleix Prat, Email: aprat@vhio.net.

Cristina Cruz, Email: ccruz@vhio.net.

Katherine A. Hoadley, Email: hoadley@med.unc.edu

Orland Díez, Email: odiez@vhebron.net.

Charles M. Perou, Email: cperou@med.unc.edu

Judith Balmaña, Email: jbalmana@vhio.net.

References

- 1.TCGA Comprehensive molecular portraits of human breast tumours. Nature. 2012;490:61–70. doi: 10.1038/nature11412. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Prat A, Adamo B, Cheang MCU, Anders CK, Carey LA, Perou CM. Molecular characterization of basal-like and non-basal-like triple-negative breast cancer. Oncologist. 2013;18(2):123–133. doi: 10.1634/theoncologist.2012-0397. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Foulkes WD, Stefansson IM, Chappuis PO, Begin LR, Goffin JR, Wong N, Trudel M, Akslen LA. Germline BRCA1 mutations and a basal epithelial phenotype in breast cancer. J Natl Cancer Inst. 2003;95:1482–1485. doi: 10.1093/jnci/djg050. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Lee E, McKean-Cowdin R, Ma H, Spicer DV, Van Den Berg D, Bernstein L, Ursin G. Characteristics of triple-negative breast cancer in patients with a BRCA1 mutation: results from a population-based study of young women. J Clin Oncol. 2011;29(33):4373–4380. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2010.33.6446. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Carey LA, Dees EC, Sawyer L, Gatti L, Moore DT, Collichio F, Ollila DW, Sartor CI, Graham ML, Perou CM. The triple negative paradox: primary tumor chemosensitivity of breast cancer subtypes. Clin Cancer Res. 2007;13(8):2329–2334. doi: 10.1158/1078-0432.CCR-06-1109. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Goldhirsch A, Winer EP, Coates AS, Gelber RD, Piccart-Gebhart M, Thürlimann B, Senn H-J. Personalizing the treatment of women with early breast cancer: highlights of the St Gallen international expert consensus on the primary therapy of early breast cancer 2013. Ann Oncol. 2013 [Google Scholar]

- 7.Fong PC, Boss DS, Yap TA, Tutt A, Wu P, Mergui-Roelvink M, Mortimer P, Swaisland H, Lau A, O’Connor MJ, Ashworth A, Carmichael J, Kaye SB, Schellens JHM, de Bono JS. Inhibition of poly(ADP-ribose) polymerase in tumors from BRCA mutation carriers. N Engl J Med. 2009;361(2):123–134. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa0900212. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Carey LA. Targeted chemotherapy? platinum in BRCA1-dysfunctional breast cancer. J Clin Oncol. 2010;28(3):361–363. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2009.24.0838. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Byrski T, Gronwald J, Huzarski T, Grzybowska E, Budryk M, Stawicka M, Mierzwa T, Szwiec M, Wiśniowski R, Siolek M, Dent R, Lubinski J, Narod S. Pathologic complete response rates in young women with BRCA1-positive breast cancers after neoadjuvant chemotherapy. J Clin Oncol. 2010;28(3):375–379. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2008.20.7019. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Balmaña J, Domchek SM, Tutt A, Garber JE. Stumbling blocks on the path to personalized medicine in breast cancer: the case of PARP inhibitors for BRCA1/2-associated cancers. Cancer Discov. 2011 doi: 10.1158/2159-8274.CD-11-0048. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Arun B, Bayraktar S, Liu DD, Gutierrez Barrera AM, Atchley D, Pusztai L, Litton JK, Valero V, Meric-Bernstam F, Hortobagyi GN, Albarracin C. Response to neoadjuvant systemic therapy for breast cancer in BRCA mutation carriers and noncarriers: a single-institution experience. J Clin Oncol. 2011;29(28):3739–3746. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2011.35.2682. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Gonzalez-Angulo AM, Timms KM, Liu S, Chen H, Litton JK, Potter J, Lanchbury JS, Stemke-Hale K, Hennessy BT, Arun BK, Hortobagyi GN, Do K-A, Mills GB, Meric-Bernstam F. Incidence and outcome of BRCA mutations in unselected patients with triple receptor-negative breast cancer. Clin Cancer Res. 2011;17(5):1082–1089. doi: 10.1158/1078-0432.CCR-10-2560. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Bayraktar S, Gutierrez-Barrera A, Liu D, Tasbas T, Akar U, Litton J, Lin E, Albarracin C, Meric-Bernstam F, Gonzalez-Angulo A, Hortobagyi G, Arun B. Outcome of triple-negative breast cancer in patients with or without deleterious BRCA mutations. Breast Cancer Res Treat. 2011;130(1):145–153. doi: 10.1007/s10549-011-1711-z. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Bayraktar S, Gutierrez-Barrera AM, Lin H, Elsayegh N, Tasbas T, Litton JK, Ibrahim NK, Morrow PK, Green M, Valero V, Booser DJ, Hortobagyi GN, Arun BK. Outcome of metastatic breast cancer in selected women with or without deleterious BRCA mutations. Clin Exp Metastasis. 2013;30(5):631–642. doi: 10.1007/s10585-013-9567-8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Huzarski T, Byrski T, Gronwald J, Górski B, Domagała P, Cybulski C, Oszurek O, Szwiec M, Gugała K, Stawicka M, Morawiec Z, Mierzwa T, Janiszewska H, Kilar E, Marczyk E, Kozak-Klonowska B, Siołek M, Surdyka D, Wiśniowski R, Posmyk M, Sun P, Lubiński J, Narod SA. Ten-year survival in patients with BRCA1-negative and BRCA1-positive breast cancer. J Clin Oncol. 2013 doi: 10.1200/JCO.2012.45.3571. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Lehmann BD, Bauer JA, Chen X, Sanders ME, Chakravarthy AB, Shyr Y, Pietenpol JA. Identification of human triple-negative breast cancer subtypes and preclinical models for selection of targeted therapies. J Clin Investig. 2011;121(7):2750–2767. doi: 10.1172/JCI45014. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Chen X, Li J, Gray WH, Lehmann BD, Bauer JA, Shyr Y, Pietenpol JA (2012) TNBCtype: a subtyping tool for triple-negative breast cancer. Cancer Inform 11 (3284-CIN-TNBCtype:-A-Subtyping-Tool-for-Triple-Negative-Breast-Cancer.pdf):147–156. doi:10.4137/cin.s9983 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 18.Larsen MJ, Kruse TA, Tan Q, Lænkholm A-V, Bak M, Lykkesfeldt AE, Sørensen KP, TvO Hansen, Ejlertsen B, Gerdes A-M, Thomassen M. Classifications within molecular subtypes enables identification of BRCA1/BRCA2 mutation carriers by rna tumor profiling. PLoS ONE. 2013;8(5):e64268. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0064268. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.TCGA Integrated genomic analyses of ovarian carcinoma. Nature. 2011;474:609–615. doi: 10.1038/nature10166. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Perou CM, Sorlie T, Eisen MB, van de Rijn M, Jeffrey SS, Rees CA, Pollack JR, Ross DT, Johnsen H, Akslen LA, Fluge O, Pergamenschikov A, Williams C, Zhu SX, Lonning PE, Borresen-Dale A-L, Brown PO, Botstein D. Molecular portraits of human breast tumours. Nature. 2000;406(6797):747–752. doi: 10.1038/35021093. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Beger C, Pierce LN, Krüger M, Marcusson EG, Robbins JM, Welcsh P, Welch PJ, Welte K, King M-C, Barber JR, Wong-Staal F. Identification of Id4 as a regulator of BRCA1 expression by using a ribozyme-library-based inverse genomics approach. Proc Natl Acad Sci. 2001;98(1):130–135. doi: 10.1073/pnas.98.1.130. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Deng C-X. BRCA1: cell cycle checkpoint, genetic instability, DNA damage response and cancer evolution. Nucleic Acids Res. 2006;34(5):1416–1426. doi: 10.1093/nar/gkl010. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.von Minckwitz G, Schneeweiss A, Loibl S, Salat C, Denkert C, Rezai M, Blohmer JU, Jackisch C, Paepke S, Gerber B, Zahm DM, Kümmel S, Eidtmann H, Klare P, Huober J, Costa S, Tesch H, Hanusch C, Hilfrich J, Khandan F, Fasching PA, Sinn BV, Engels K, Mehta K, Nekljudova V, Untch M. Neoadjuvant carboplatin in patients with triple-negative and HER2-positive early breast cancer (GeparSixto; GBG 66): a randomised phase 2 trial. Lancet Oncol. 2014;15(7):747–756. doi: 10.1016/S1470-2045(14)70160-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Sikov W, Berry D, Perou C, Singh B, Cirrincione C, Tolaney S, Kuzma C, Pluard T, Somlo G, Port E, Golshan M, Bellon J, Collyar D, Hahn O, Carey L, Hudis C, Winer E (2013) Impact of the addition of carboplatin (Cb) and/or bevacizumab (B) to neoadjuvant weekly paclitaxel (P) followed by dose-dense AC on pathologic complete response (pCR) rates in triple-negative breast cancer (TNBC): CALGB 40603 (Alliance). San Antonio Breast Cancer Symposium S5-01

- 25.Byrski T, Dent R, Blecharz P, Foszczynska-Kloda M, Gronwald J, Huzarski T, Cybulski C, Marczyk E, Chrzan R, Eisen A, Lubinski J, Narod S. Results of a phase II open-label, non-randomized trial of cisplatin chemotherapy in patients with BRCA1-positive metastatic breast cancer. Breast Cancer Res. 2012;14(4):R110. doi: 10.1186/bcr3231. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Von Minckwitz G, Hahnen E, Fasching P, Hauke J, Schneeweiss A, Salat C, Rezai M, Blohmer J, Zahm D, Jackisch C, Gerber B, Klare P, Kummel S, Eidtmann H, Paepke S, Nekljudova V, Loibl S, Untch M, Schmutzler R, Groups aGaA-BS Pathological complete response (pCR) rates after carboplatin-containing neoadjuvant chemotherapy in patients with germline BRCA (gBRCA) mutation and triple negative breast cancer (TNBC)–Results from GeparSixto. Proc Am Soc Clin Oncol: a1005, 2014

- 27.Leong C-O, Vidnovic N, DeYoung MP, Sgroi D, Ellisen LW. The p63/p73 network mediates chemosensitivity to cisplatin in a biologically defined subset of primary breast cancers. J Clin Investig. 2007;117(5):1370–1380. doi: 10.1172/JCI30866. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Birkbak NJ, Wang ZC, Kim J-Y, Eklund AC, Li Q, Tian R, Bowman-Colin C, Li Y, Greene-Colozzi A, Iglehart JD, Tung N, Ryan PD, Garber JE, Silver DP, Szallasi Z, Richardson AL. Telomeric allelic imbalance indicates defective DNA repair and sensitivity to DNA-damaging agents. Cancer Discov. 2012;2(4):366–375. doi: 10.1158/2159-8290.CD-11-0206. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Isakoff S, He L, Mayer E, Goss P, Traina T, Carey L, Krag K, Liu M, Rugo H, Stearns V, Come S, Ryan P, Finkelstein D, Hartman A, Garber J, Timms K, Winer E, Ellisen L Identification of biomarkers to predict response to single-agent platinum chemotherapy in metastatic triple-negative breast cancer (mTNBC): Correlative studies from TBCRC009. Proc Am Soc Clin Oncol: a1020, 2014

- 30.Parker JS, Mullins M, Cheang MCU, Leung S, Voduc D, Vickery T, Davies S, Fauron C, He X, Hu Z, Quackenbush JF, Stijleman IJ, Palazzo J, Marron JS, Nobel AB, Mardis E, Nielsen TO, Ellis MJ, Perou CM, Bernard PS. Supervised risk predictor of breast cancer based on intrinsic subtypes. J Clin Oncol. 2009;27(8):1160–1167. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2008.18.1370. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.