Abstract

Mesenchymal dysplasia (mes) mice harbour a truncation in the C-terminal region of the Hh-ligand receptor, Patched-1 (mPtch1). While the mes variant of mPtch1 binds to Hh-ligands with an affinity similar to that of wild type mPtch1 and appears to normally regulate canonical Hh-signalling via smoothened, the mes mutation causes, among other non-lethal defects, a block to mammary ductal elongation at puberty. We demonstrated previously Hh-signalling induces the activation of Erk1/2 and c-src independently of its control of smo activity. Furthermore, mammary epithelial cell-directed expression of an activated allele of c-src rescued the block to ductal elongation in mes mice, albeit with delayed kinetics. Given that this rescue was accompanied by an induction in estrogen receptor-alpha (ERα) expression and that complex regulatory interactions between ERα and c-src are required for normal mammary gland development, it was hypothesized that expression of ERα would also overcome the block to mammary ductal elongation at puberty in the mes mouse. We demonstrate here that conditional expression of ERα in luminal mammary epithelial cells on the mes background facilitates ductal morphogenesis with kinetics similar to that of the MMTV-c-srcAct mice. We demonstrate further that Erk1/2 is activated in primary mammary epithelial cells by Shh-ligand and that this activation is blocked by the inhibitor of c-src, PP2, is partially blocked by the ERα inhibitor, ICI 182780 but is not blocked by the smo-inhibitor, SANT-1. These data reveal an apparent Hh-signalling cascade operating through c-src and ERα that is required for mammary gland morphogenesis at puberty.

Keywords: Hedgehog pathway, Patched1, Estrogen receptor, Mesenchymal dysplasia, Mammary gland

Introduction

Estrogens are a class of hormones that play crucial roles in diverse aspects of human biology, including sexual development and reproduction. Dysregulation of estrogen signalling has been implicated in a variety of diseases, including breast and uterine cancers, osteoporosis and cardiovascular disease. Estrogen receptor-alpha (ERα) is one of the principal protein receptors responsible for mediating the actions of estrogen (Heldring et al., 2007). As a member of the large superfamily of nuclear hormone receptors, ERα acts as a ligand-activated transcription factor (Heldring et al., 2007; Mangelsdorf et al., 1995). Upon binding of its ligand, 17β-estradiol (E2), ERα modulates transcription by either binding directly to estrogen response elements (ERE) in the promoter of E2 regulated genes, or indirectly through protein–protein interactions with other transcription factors (Heldring et al., 2007; Klinge, 2000).

ERα regulates target gene transcription through two independent activation functions (AF), AF-1 and AF-2 (Arao et al., 2011; Arnal et al., 2013; Lannigan, 2003; McGlynn et al., 2013). Transcriptional activation by ERα can be promoted through functional cooperation between the two AFs or through either AF independently (Arnal et al., 2013). AF-2 contains the ligand binding domain (LBD), and its activity depends on E2 binding (Arao et al., 2011; McGlynn et al., 2013). Ligand-independent activation is facilitated by the AF-1 domain. This domain harbours several sequences that facilitate phosphorylation by factors mediating a number of signal transduction pathways. For example, MAPK and Cdk7 activates ERα by directly phosphorylating Ser118 within the AF-1 domain (Bunone et al., 1996; Chen et al., 2002).

More recently, it was determined that E2 elicits changes in cellular processes through ERα outside of the nucleus via activation of protein kinases, phosphatases and secondary messengers (Haynes et al., 2003; Kousteni et al., 2001). One of these rapid “non-genomic” signal transduction mechanisms includes the c-src protein tyrosine kinase (Castoria et al., 2012; Li et al., 2007). ERα transiently activates c-src in response to E2 binding by increasing phosphorylation of Tyr416, resulting in downstream activation of ras and MAPK (Migliaccio et al., 1998, 1996). The SH2-domain of c-src also interacts directly with ERα at Tyr537 (Arnold et al., 1995; Migliaccio et al., 2000; Sun et al., 2012). Phosphorylation of Tyr537 by c-src rapidly activates signal transduction pathways involving Erk and phosphoinositide 3-kinase (PI3K) (Varricchio et al., 2007), as well as stimulating ERα target gene transcription, ERα ubiquitylation and proteosomal degradation (Sun et al., 2012).

Genetic deletion of ERα in mice established important roles for this receptor for normal adult mammary gland development. Mammary glands of adult female ERα knock-out ( αERKO) mice fail to respond to ovarian hormones resulting in a failure of ductal rudiments to elongate and fill the fat pad (Couse et al., 2000; Lubahn et al., 1993; Pedram et al., 2009). Interestingly, animals lacking detectable c-src also exhibit defects in mammary gland morphogenesis and primary mammary epithelial cells (MECs) derived from c-src-null mice fail to respond to exogenous estrogen stimulation (Kim et al., 2005). Thus, proper mammary gland morphogenesis not only requires E2-activated ERα, but also depends on ERα interaction with other signalling cascades.

We and others demonstrated previously that Hedgehog (Hh)-signalling also plays a role in mammary gland development (Chang et al., 2012; Moraes et al., 2009). Animals homozygous for the mesenchymal dysplasia (mes) (Makino et al., 2001; Sweet et al., 1996) allele of the Hh-ligand receptor, Patched-1 (Ptch1), displayed a blocked mammary gland phenotype resembling that of the ERα knock-out mice. The lack of ductal outgrowth in mes mice was associated with reduced expression of ERα and progesterone receptor (PR) in epithelial cells (Chang et al., 2012; Moraes et al., 2009). The mes allele encodes a deletion in the second-last exon of mPtch1, resulting in a truncated protein that replaces the last 220 a. a. with a random 68 a.a. polypeptide. We showed that this region of Ptch1 binds to factors containing SH3- and WW-domains, that the SH3-domain of c-src binds to the C-terminus of mPtch1 (Chang et al., 2010) and that transiently expressed mPtch1 binds to endogenous c-src in the absence of added Shh-ligand (Harvey et al., 2014). Using a genetic approach, we showed further that forced expression of an activated c-src (c-srcAct) transgene in luminal mammary epithelial cells rescued the blocked mammary morphogenesis arising in mes mice (Chang et al., 2012). This rescue was accompanied by a strong increase in ERα expression.

Interactions between the ERα activity and Hh-signalling has also been demonstrated. In ERα-positive gastric cancer cells, E2 induced Shh expression and promoted cellular proliferation independent of smo-activity (Kameda et al., 2010). A similar result was reported in the ERα-positive breast cancer cell line, MCF-7. Here, E2 induced expression of Shh and Gli1. This activation is inhibited in cells treated with the anti-estrogen, ICI 182780 (Koga et al., 2008). Inhibiting smo-activity with the small molecule inhibitor, cyclopamine, significantly suppressed proliferation of both ERα-positive and ERα-negative breast cancer cell lines, MCF-7 and MDA-MB-231, respectively (Che et al., 2013). Cyclopamine also significantly decreased ERα expression in MCF-7 cells. Since c-src binds to mPtch1 (Chang et al., 2010; Harvey et al., 2014) and also activates ERα (Castoria et al., 2012; Sun et al., 2012), we sought to determine whether ERα-activity acts genetically downstream of Ptch1. We demonstrate here that conditional expression of ERα overcomes the block to ductal elongation in mes mice with kinetics similar to those for the rescue of the mes phenotype by the MMTV-c-srcAct allele. Furthermore, we define a novel pathway stimulated by Shh that activates Erk1/2 and requires the activity of either ERα or c-src but not smo.

Materials and methods

Cell culture

HEK 293 cells (a gift of S. Girardin) were cultured in DMEM with 10% FBS and 1% penicillin-streptomycin. Shh Light II fibroblasts (ATCC) were cultured in DMEM supplemented with 400 mg/ml G418 (Gibco) and 0.14 μg/ml Zeocin (Invitrogen)

Mice

Wild type C57Bl/6N mice (Charles River) or C57Bl/6N mice heterozygous for the mesenchymal dysplasia (mes) allele of Ptch1 (JacksonLabs) were crossed with CERM mice, which harbour a flag-tagged ERα transgene under the control of the tetO and the “Tet-On” transgene under the control of the MMTV promoter (Díaz-Cruz et al., 2011; Frech et al., 2008, 2005; Hruska et al., 2002; Miermont et al., 2010) (P. A. Furth, Georgetown University). Compound mice were then backcrossed onto C57Bl/6 (CharlesRiver) for > 4 generations. Transgene expression was induced by constant administration (changed twice per week) of 2 mg/ml doxycycline in sterile-filtered drinking water containing 5% sucrose.

For genotyping, tail DNA was extracted and 2 μl DNA was amplified in a 25 μl polymerase chain reaction using Taq DNA Polymerase (Thermo Scientific). Forward (F) and reverse (R) primer sequences were as follows:

Mes

F 5′-TCCAAGTGTCGTCCGGTTTG-3′ and R 5′-GTGGCTTCCACAATCACTTG-3′ (Chang et al., 2012); FLAG-ERα: F 5′-CGAGCTCGGTACCCGGGTCG-3′ and R 5′-GAACACAGTGGGCTTGCTGTTG-3′ (Miermont et al., 2010); MMTV-rtTa: F 5′-ATCCGCACCCTTGATGACTCCG-3′ and R 5′-GGCTATCAACCAACACACTGCCAC-3′ (Miermont et al., 2010). Reaction conditions for MMTV-rtTa and mes were 60 s each for denaturation, annealing and extension for 32 cycles, while for FLAG-ERα they were 60 s denaturation, 90 s annealing, and 120 s extension for 35 cycles. The annealing temperatures for mes, FLAG-ERα and MMTV-rtTa were 53 °C, 57 °C and 56 °C, respectively.

Whole mount analysis

Whole mount analysis of mammary glands was performed as previously described (Chang et al., 2012; Rasmussen et al., 2000). Briefly, mammary glands were fixed in Carnoy’s fixative (10% acetic acid, 30% chloroform, 60% ethanol) overnight at 4 °C, and washed in 70%, 50% and 25% ethanol for 15 min each. The glands were rinsed in water for 5 min and then stained in Carmine alum overnight at room temperature. The glands were washed in 70%, 95% and 100% ethanol for 15 min each, and then cleared in xylene for two changes for 30 min each followed by mounting with Permount.

Immunofluorescence

Paraffin-embedded tissue sections were deparaffinized in xylene and rehydrated gradually through 100%, 95%, 80%, 70% ethanol washed and water. Antigen retrieval was performed by boiling sections for 15 min in 10 mM sodium citrate, pH 6.0, in a pressure cooker pre-heated in a microwave oven for 20 min before immersing slides. After boiling, sections were permeabilized with 0.2% TritonX-100 for 10 min. After washing, sections were incubated with primary antibodies for 1 h at room temperature in 3% BSA in PBS. Antibodies and dilutions are as follows: 1:100 anti-ERα (Santa Cruz; sc-542), 1:100 anti-BrdU (abcam: ab6326), 1:20 anti-Flag (abm;G191) and undiluted anti-Alx4 containing supernatant (produced in our lab). Sections were then washed and labelled with fluorescently-labelled secondary antibody added to samples for 1 h. Sections were imaged using a Nikon Ellipse fluorescent microscope equipped with a QImaging Fast1394 digital camera and compiled using Qcapture Pro software (QImaging).

Preparation of Shh-conditioned media

Shh-conditioned media was prepared as previously described (Capurro et al., 2012). Shh-and pcDNA-conditioned media were prepared by transfecting 40% confluent 10 cm plates of HEK293 cells in 10% FBS with 10 μg of pcDNA3.1-N-Shh (gift of J. Filmus, Sunnybrook Health Sciences Centre) or pcDNA3 using 2 mg/ml PEI at a 2:1 ratio. Cells were grown for 24 h before the media was switched to 5% FBS for 48 h. The media was collected, centrifuged at 2500 rpm for 5 min at 4 °C and harvested. The supernatant was then sterile-filtered using a 0.22 μm syringe filter. Prior to use, conditioned media was diluted in serum free DMEM to a final serum concentration of 0.5%. Activity of conditioned media was measured in a luciferase assay in Shh Light II fibroblasts (Chang et al., 2010; Sasaki et al., 1997).

Primary cell culture

Primary mammary epithelial and mesenchymal cells were isolated as described previously (Chang et al., 2012; Niranjan et al., 1995). Briefly, thoracic and inguinal mammary glands were dissected from euthanized mice and minced with a razor blade into small fragments. The minced mammary glands were incubated in a solution of 3 mg/ml collagenase A and trypsin (Sigma-Aldrich) in DMEM/F12 for 2 h at 37 °C. Mechanical dissociation was then performed by slowly pipetting with a 5 ml pipette, adding FBS to a final concentration of 2%. Epithelial (pelleted) and mesenchymal (supernatant) layers were separated by centrifuging at 200 rpm for 2 min. The mesenchymal layer was collected and washed with DMEM/F12 and plated in DMEM/F12 containing 10% FBS supplemented with 10 μg/ml insulin, 10 μg/ml transferrin and 20 ng/ml EGF. For organoid culture, the epithelial pellet was resuspended in 3 mg/ml collagenase A in DMEM/F12 and incubated for 30 min at 37 °C. The cells were pelleted by centrifugation, washed and plated in primary culture media mentioned above. The organoid containing media was removed and re-plated once the remaining mesenchymal cells attached to the plate (~2 h).

For Erk1/2 activation assays, primary mouse mammary epithelial cells and mesenchymal cells were serum starved in 0.2% FBS containing culturing media for 24 and 48 h, respectively. Cells were then stimulated with pcDNA3-conditioned media, Shh-conditioned media, or Shh-conditioned media with either 10 nM ICI 182 780, 20 nM SANT-1 (Toronto Research Chemicals), or 10 nM PP2 for 24 h. Cells were lysed in 1% NP40 lysis buffer and levels of phospho-Erk1/2 and total Erk1/2 determined by western blot.

Western blotting

Cell lysates were prepared following addition of 1% NP40 lysis buffer containing protease and phosphatase inhibitors (0.57 mM PMSF, 10 μM leupeptin, 0.3 μM aprotinin, 10 mM NaF, 1 mM sodium orthovanadate). For western blots, 4 × SDS-loading buffer (50 mM Tris pH 6.8, 100 mM DTT, 2% SDS, 0.1% bromophenol blue, 10% glycerol) was added to 50 μg of lysate and boiled for 5 min. Samples were resolved by 10% SDS-PAGE and blotted onto nitrocellulose membrane. Blots were probed with primary antibody overnight at 4 °C. Antibodies and dilutions used are as follows: 1:1000 mouse α-p-ERK (Cell Signaling) and 1:1000 rabbit α-ERK (Cell Signaling). Blots to be re-probed were stripped in stripping buffer (2% SDS, 62.5 mM Tris pH 6.8, 100 mM β-mercaptoethanol) for 30 min at 72 °C.

Quantitative RT-PCR

For quantitative RT-PCR (qPCR), total RNA was isolated from primary mouse mammary mesenchymal and epithelial cells using Trizol (Invitrogen). DNAse treatment (Fermentas) was performed on 400 ng of RNA from each sample. Reverse transcription was performed using SuperScript II Reverse Transcriptase (Invitrogen) and random hexamer primers (Fermentas). Resulting cDNA was diluted 1:25 and qPCR was then performed using an iQ SYBR Green Supermix (Bio-Rad) in 10 μl reactions. All reactions consisted of 40 cycles with 30 s denaturation at 72 °C, 30 s annealing and 30 s extension at 60 °C. Primer specificity was confirmed by a melt curve analysis. Results were quantified using the ΔΔCt method with Arbp as a reference gene. Primers adapted from previously published sequences (Webster et al., 1995; Zhang et al., 2009) were used as follows:

mPtch1 forward: 5′-GGTGGTTCATCAAAGTGTCG-3′;

mPtch1 reverse: 5′-GGCATAGGCAAGCATCAGTA-3′;

mGli1 forward: 5′-CCCATAGGGTCTCGGGGTCTCAAAC-3′;

mGli1 reverse: 5′-GGAGGACCTGCGGCTGACTGTGTAA-3′;

mArbp forward: 5′-GAAAATCTCCAGAGGCACCATTG-3′;

mArbp reverse: 5′-TCCCACCTTGTCTCCAGTCTTTAT-3′;

Results

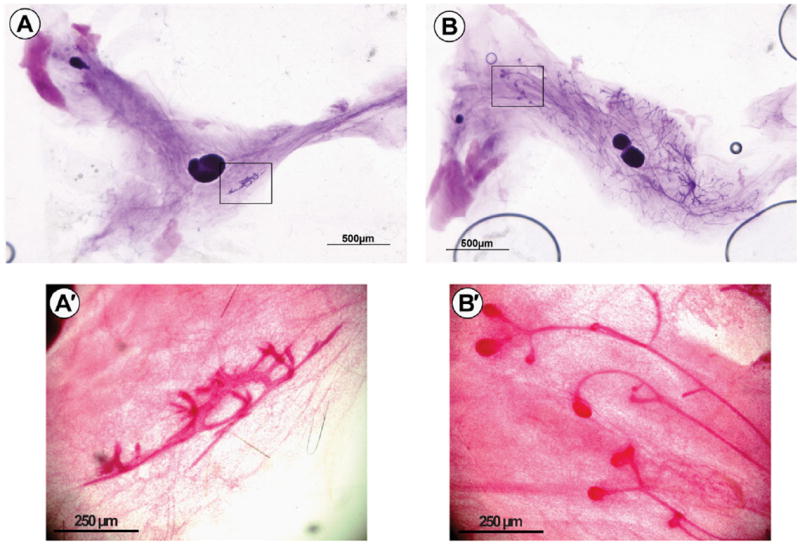

Mice homozygous for the mes allele exhibit a block to ductal elongation in the mammary gland during puberty. This defect is overcome, albeit with distinct kinetics relative to wild type animals, by constitutive expression of activated c-src under the control of the MMTV-promoter. Given the increased expression of ERα in mes/MMTV-c-srcAct mice and the role of c-src in activating ERα, we hypothesized that forced expression of ERα would also rescue the mes phenotype. CERM mice (Frech et al., 2005; Tilli et al., 2003), a compound transgenic mouse that harbours a tetO-ERαFlag allele under the control of MMTV-”Tet-On”, were bred to mes mice and backcrossed onto a C57Bl/6 background. ERα expression in compound mes/CERM mice was then induced by long-term administration of the doxycycline beginning at 3 weeks of age. As Fig. 1A and A′ illustrate, at 20 weeks of age, mammary gland #4 in the adult mes females had not developed, remaining in the state that developed during embryogenesis. However, as Fig. 1B shows, ductal elongation was apparent in compound mice homozygous for the mes allele and expressing MMTV-directed ERα (mes/CERM). At this stage, terminal end buds were also apparent (Fig. 1B′) indicative of these ducts elongating into the fat pad similar to that observed for wild type mice at puberty.

Fig. 1.

Forced expression of ERα rescues the mammary gland phenotype in mes mice. Mammary gland #4 was isolated from twenty week-old mice and whole mounts prepared. (A) and (A′) mes; (B) and (B′) mes/CERM. After twenty weeks, mammary ductal morphogenesis in mes mice is blocked. This phenotype is reversed in mes mice expressing ERα directed to mammary epithelium, albeit with delayed kinetics. Magnification of ducts reveal a non-proliferative rudimental ductal structure in mes mammary glands (A′). Terminal end buds are present and ductal structures have not reached the limits of the fat pads in mes/CERM mice (B′).

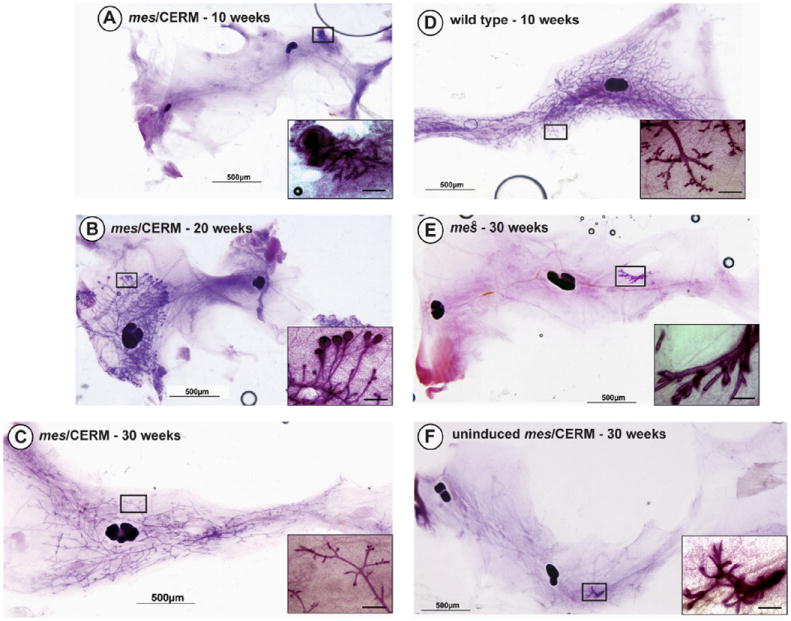

Similar to the observation we reported previously for mes/MMTV-c-srcAct mice (Chang et al., 2012), the rescue by CERM mice of the mes phenotype exhibited distinct kinetics of ductal elongation relative to the development of wild type mammary glands (Fig. 2). By ten weeks of age, only rudimentary ductal structures resembling those of their mes littermates were seen for doxycycline-fed mes/CERM mice (Fig. 2A). However, between 15 and 20 weeks, the mammary ducts in doxycycline-fed mes/CERM mice had penetrated the fat pad to various degrees (Fig. 2B). Significantly, terminal end buds (TEBs) were present in these animals (see Fig. 1B′). Complete morphogenesis was observed in doxycyline-fed mes/CERM females between 24 to 30 weeks of age (Fig. 2C). For these mature animals, the ducts in these mammary glands reached the limits of the fat pad and TEBs were no longer present. As we reported previously (Chang et al., 2012), development of the mammary glands in mes littermates beyond the primitive ductal structures established during embryogenesis was not observed, even at thirty weeks (Fig. 2E) nor were ducts evident in mes/CERM animals not induced with doxycycline (Fig. 2F).

Fig. 2.

Delayed rescue of mammary morphogenesis in mes/CERM mice is complete by thirty weeks. Whole mounts of mammary gland #4 were prepared from glands isolated from age-matched littermates at different points during development. (A) Mammary glands from mes/CERM exhibit no ductal proliferation at ten weeks, while wild type littermates (D) are completely developed. (B) Terminal end buds with partial filling of the mammary gland fat pad by ductal elongation are found in mes/CERM females at twenty weeks of age. (C) Ducts have reached the limits of the fat pad by thirty weeks of age and terminal end buds are no longer present. (F) Mammary glands from uninduced adult mes/CERM mice fail to develop and resemble mammary glands from mes mice (E) that exhibit only a rudimentary ductal tree, even at thirty weeks. Rescue of the mes mammary defect by ERα in animals older than eighteen weeks is significant (p = 0.0278; Fisher’s exact test). Ductal structures are magnified in corresponding inserts. Scale bar: 50 μm.

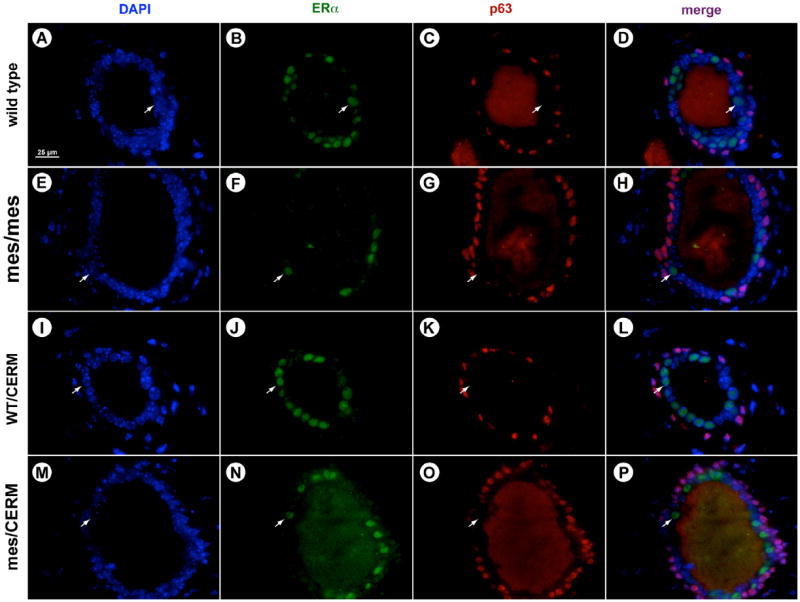

To determine if the mammary ducts of mes/CERM mice exhibited normal epithelial organization, sections were probed for ERα and the myoepithelial marker, p63 (Fig. 3). Nuclear ERα expression was observed in mammary epithelial cells from ducts of adult virgin wild type, mes, wild type/CERM and mes/CERM mice. Expression of ERα was restricted to the luminal epithelial cells, evident by the lack of overlap between signals for ERα with p63. As we demonstrated previously (Chang et al., 2010; Moraes et al., 2009), reduced ERα expression was observed in mes mice (Fig. 3E and H) compared to wild type littermates (Fig. 3A–D). While approximately 40% of epithelial cells were positive for ERα staining in wild type animals, ERα staining was only observed in 10–20% of epithelial cells in mes littermates. An approximate 2-fold increase in the percentage of cells demonsrating nuclear localized ERα expression was observed in mes mice expressing MMTV-ERα, relative to mes alone. However, expression levels and subcellular localization of ERα were indistinguishable between wild type (Fig. 3A–D), mes/CERM (Fig. 3M–P) and WT/CERM (Fig. 3I and L) littermates.

Fig. 3.

mes/CERM ducts demonstrate normal cellular organization and ERα expression. Immunofluorence staining for ERα and p63 in adult virgin wild type ((A)–(D)), mes/mes ((E)–(H)), wild type/CERM ((I)–(L)) and mes/CERM ((M)–(P)) mice. No co-localization of ERα is observed with p63 ((D), (H), (L) and (P)). Reduced ERα expression is apparent in mes mice (F) compared to wild type (p = 0.02) (B). ERα expression is increased, however, in mes mice expressing MMTV-ERα (p = 0.021) (N), but expression levels do not differ between mes/CERM and wild type littermates. Scale bar: 25 μm. ERα-positive cell percentages were determined by cell counting; 10 fields per animal, n = 3 for all animal groups. Data was analyzed by one-way ANOVA followed by pairwise comparisons of means using Dunnett’s multiple comparison’s test.

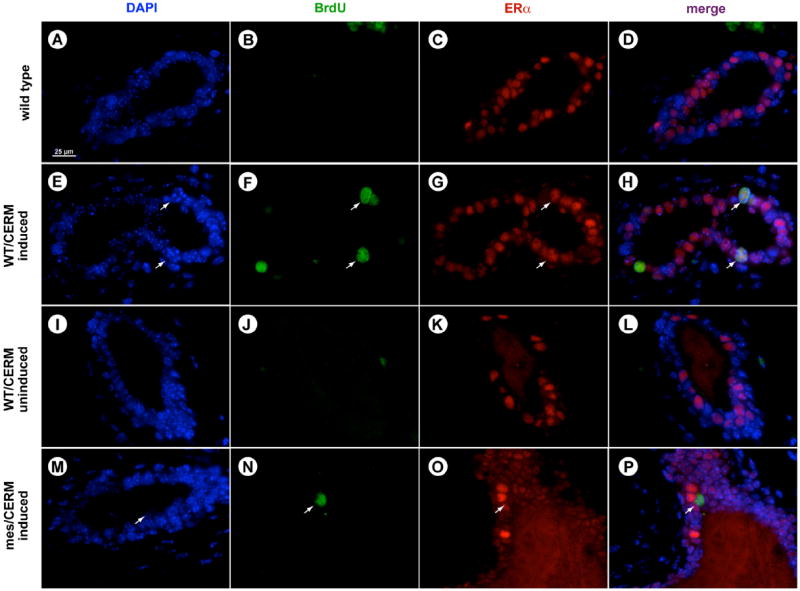

Immunofluorescence revealed that induction of the conditional ERα expression in both wild type and mes mice caused aberrant cell cycle progression in adult mammary glands (Fig. 4). Specifically, cells incorporating BrdU were essentially absent in the mammary glands of wild type adult animals (Fig. 4A and D). However, following the 2 h pulse of BrdU, a fraction of cells in every duct in doxycycline-fed WT/CERM (Fig. 3E and H) and mes/CERM (Fig. 3M–P) mice stained positively, indicating the presence of cycling cells due to the induced expression of ERα. BrdU incorporation was not observed in WT/CERM mice not fed doxycycline (Fig. 4I and L). Cells expressing detectable levels of the flag-tagged ERα transgene were not associated with the cells that had incorporated BrdU (Supplementary Fig. 1), although all BrdU-incorporating cells stained with an anti-ERα antibody (Fig. 4C and D), suggesting that transgene expression generated an overall proliferative state in the mammary gland rather than driving specific cells through the cell cycle.

Fig. 4.

Forced ERα expression induces cell cycle progression in adult mammary glands. Twenty four week-old wild type ((A)–(D)), induced wild type/CERM ((E)–(H)), uninduced wild type/CERM ((I)–(L)) and mes/CERM ((M)–(P)) littermates were injected with BrdU 2 h prior to mammary gland excision and incorporation was determined through immunofluorescence. BrdU incorporation was absent in the mammary glands of 24 week-old adult wild type mice (B). Cells positive for BrdU staining are observed in ducts from both induced wild type/CERM (F) and mes/CERM mice (N), but not in wild type/CERM that were not fed doxycycline (J). BrdU positive cells co-localize with cells expressing ERα ((H) and (P)). Scale bar: 25 μm.

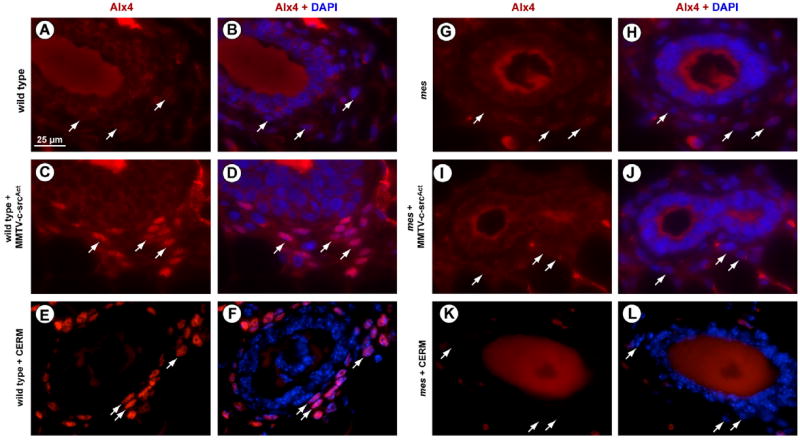

To further investigate the overall proliferative state of the mammary gland, changes in the expression of the stromally-restricted, homeodomain protein, Alx4 (Hudson et al., 1998; Qu et al., 1998, 1997a, 1997b), were assessed. Alx4 is induced in stromal fibroblasts during puberty and pregnancy but is not expressed in the resting adult mammary gland (Hudson et al., 1998; Joshi et al., 2006). Furthermore, administration of E2 to pre-pubescent female mice induces Alx4 expression in these fibroblasts while the absence of Alx4 in stromal fibroblasts in Strong’s luxoid mice causes defects in mammary ductal morphogenesis during puberty. Thus, we examined the expression of Alx4 expression in stromal cells in wild type and mes adults that conditionally expressed ERα (CERM mice) and compared these to mammary glands expressing activated c-src under the control of the MMTV promoter. As Fig. 5A and B illustrates, Alx4 expression was generally absent in the adult wild type stromal cells adjacent the epithelial ducts. However, in wild type mice with induced ERα (Fig. 5E and F) or constitutive expression of c-srcAct (Fig. 5C and D) in mammary epithelial cells, an induction of Alx4 expression in stromal fibroblasts in these adult animals was apparent. In contrast to CERM or MMTV-c-srcAct on the wild type background, however, Alx4 expression was not induced by these two alleles on the mes background (Fig. 5I, J and K,L, respectively). Thus, the luminal epithelial-restricted expression of either ERα or c-srcAct appeared to generate a signal, emanating from mammary epithelial cells, that stimulated stromal fibroblasts to express Alx4. The induction of Alx4 expression in these fibroblasts was dependent, however, on the presence of wild type mPtch1.

Fig. 5.

Conditional expression of ERα induces stromal expression of Alx4 in adult female mice. Mammary glands of wild type ((A)–(B)), wild type/c-srcAct ((C)–(D)), wild type/CERM ((E)–(F)), mes ((G)–(H)), mes/c-srcAct ((I)–(J)), mes/CERM (induced) ((K)–(L)) virgin 24 week-old adult female mice were stained for Alx4. Staining is absent in wild type mammary ducts. Expression of constitutive c-srcAct or conditional ERα in ductal epithelial cells induces stromal expression of Alx4. Scale bar: 25 μm.

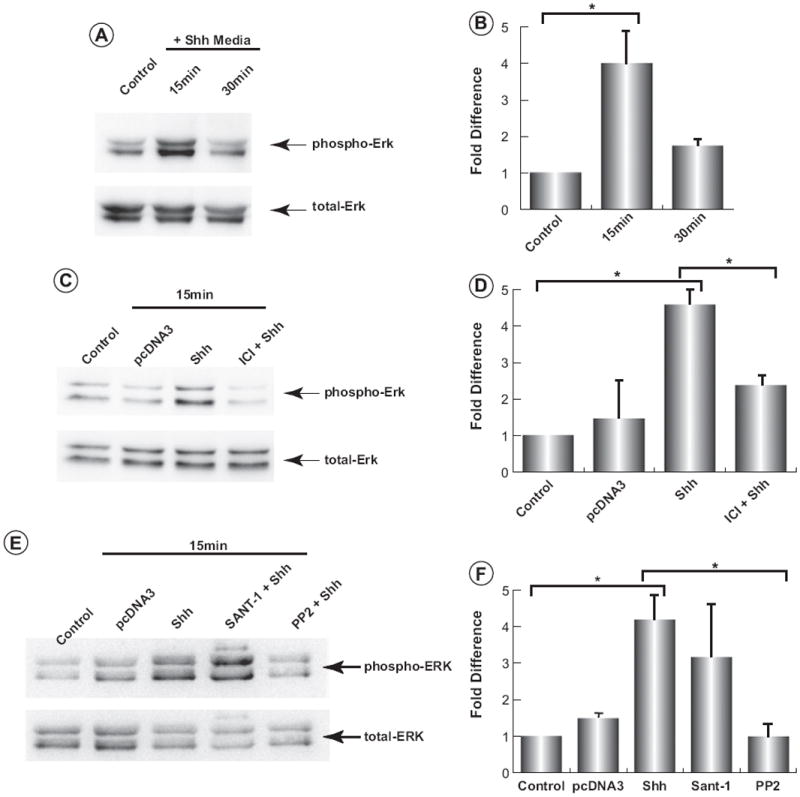

E2 rapidly activates the MAPK signalling pathway in the human breast cancer cell lines, MCF-7 and T47D (Castoria et al., 1999; Improta-Brears et al., 1999; Migliaccio et al., 1996; Song et al., 2002), in a c-src-dependent manner (Di Domenico et al., 1996; Song et al., 2002). Shh-ligand also stimulates the activation of both Erk1/2 (Chang et al., 2010) and c-src (Harvey et al., 2014) in a human mammary epithelial cell line, MCF10a, that lacks detectable expression of smo (Chang et al., 2012, 2010; Mukherjee et al., 2006; Zhang et al., 2009). As Fig. 6A illustrates, phosphorylation of Erk1/2 was induced in wild type, serum-starved primary mammary epithelial cells within 15 min of stimulation by N-Shh. Stimulation occurred in the presence of the smo-antagonist, SANT-1, which we showed previously inhibited canonical Hh-signalling in primary mammary mesenchymal cells (Harvey et al., 2014). Activation of Erk1/2 occurring through a smo-independent mechanism (Fig. 6E) is also consistent with our previous observations using the smo-deficient MCF10a breast cancer line (Chang et al., 2010) as well as in smo-deficient MEFs (unpublished observation). Thus, the dependence of c-src activity on N-Shh stimulation of Erk1/2 was determined in primary mammary epithelial cells treated with the c-src inhibitor PP2 (Hanke et al., 1996). As Fig. 6E shows further, a complete block of Erk1/2 activation occurs when c-src activity is inhibited.

Fig. 6.

Shh activates Erk1/2 in primary mammary epithelial cells is an ERα- and c-Src- dependent manner. Primary mammary epithelial cells isolated from wild type mice at three months of age were serum starved for 24 h and then treated with Shh-conditioned media, pcDNA3-control media, or Shh-conditioned media with ICI 182 780, SANT-1 or PP2 for 1 h. Blots were probed for activated (phospho)-Erk1/2 and then re-probed for total Erk1/2. (A) Activation of Erk1/2 is observed 15 min following stimulation by sonic hedgehog. (C) Addition of ICI 182 780 1 h prior to Shh stimulation partially inhibits Erk1/2 activation. (E) Cells were treated with 20 nM SANT-1 or 5 μM PP2 for 1 h before Shh stimulation. PP2, but not SANT-1 treatment inhibits Shh-dependent Erk1/2 activation. Quantification of Erk1/2 activation are shown ((B), (D) and (F)). Data were analyzed by two-way ANOVA followed by pairwise comparison of means using Dunnett’s multiple comparisons test. Data are displayed as mean ± SEM, n = 3 for all groups, except PP2 + Shh, n = 2. *p < 0.05.

The role of ERα for N-Shh activation of Erk1/2 was then determined by stimulating cells in the presence of the anti-estrogen, ICI 182780 (Wakeling et al., 1991). As illustrated in Fig. 6C, ICI 182780 partially inhibited Erk1/2 activation by N-Shh ligand. Specifically, treatment of primary epithelial cells with N-Shh-conditioned media caused a 4-fold increase in Erk1/2 phosphorylation. This level of activation was reduced by 50% in the presence of ICI 182780. Thus, N-Shh activated Erk1/2 in the presence of the smo-inhibitor, SANT-1, but required the activities ERα and c-src.

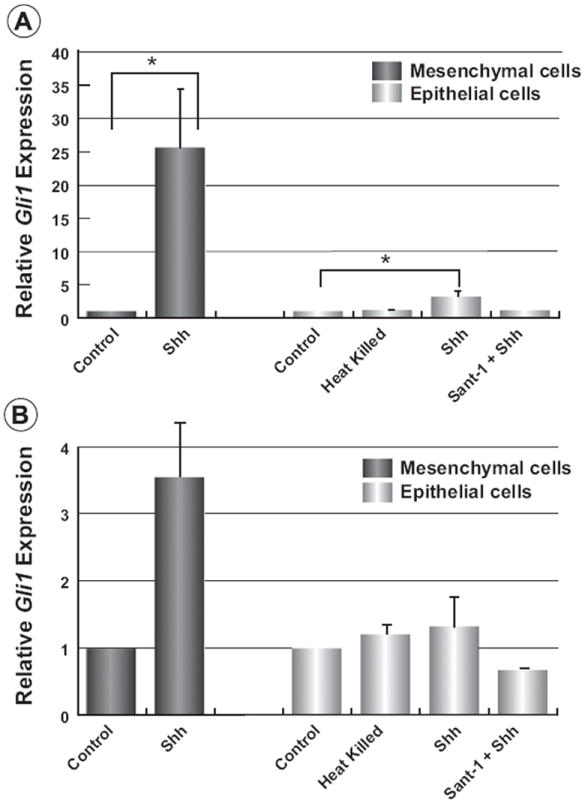

While N-Shh stimulates non-canonical Hh-signalling cascades in both primary mammary epithelial and mesenchymal cells, smo-dependent canonical Hh-signalling in primary epithelial cells has not been reported. Thus, primary epithelial and mesenchymal cells from wild type mammary glands were stimulated with N-Shh peptide and changes in expression of both Hh-pathway targets, Gli1 and Ptch1 were determined. As Fig. 7A reveals, stimulation of primary mammary mesenchymal cells resulted in a greater than 25-fold increase in Gli1 expression. Likewise, Fig. 7B illustrates the 4-fold increase in Ptch1 expression in these same cells. We demonstrated previously that Gli1 and Ptch1 induction in primary mouse mesenchymal cells through N-Shh stimulation was dependent on the activity of smo, since induction is abolished in cells treated with N-Shh in the presence of SANT-1 or by using heat-killed N-Shh peptide (Harvey et al., 2014). However, despite the apparent response of these mesenchymal cells to N-Shh ligand, a very limited or no induction of Gli1 and Ptch1, respectively, were observed for primary epithelial cells. Specifically, a small but significant 3-fold increase in Gli1 levels was observed after 24 h while no induction of Ptch1 was observed. Thus, mammary epithelial cells are relatively refractory to stimulation through the canonical Hh-pathway but are able to respond through non-canonical pathway, determined by the activation of Erk1/2 by N-Shh.

Fig. 7.

Limited canonical Hh-signalling in primary mammary epithelial cells. Primary mammary epithelial and mesenchymal cells isolated from three monthold wild type mice were serum starved for 24 h and 48 h, respectively. Cells were then stimulated with heat-killed N-Shh peptide, active N-Shh peptide, or N-Shh peptide with 20 nM SANT-1 for 24 h. (A) qPCR reveals that Gli1 is induced 25-fold in mesenchymal by N-Shh. Only a small but significant 3-fold increase in Gli1 was seen in epithelial cells from the same animals, however. (B) N-Shh peptide induced Ptch1 expression 3.5-fold in mesenchymal cells. No induction of mPtch1 was observed for epithelial cells. Data were annalyzed by one-way ANOVA followed by pairwise comparisons of means by Dunnett’s multiple comparisons test. Data are displayed as mean ± SE, *p < 0.05, n = 3.

Taken together, using both a genetic approach and experiments using primary mammary cells in culture, these data suggest that a novel Hh-signalling pathway involving the activities of ERα and c-src is required for regulating mammary gland development.

Discussion

The Hedgehog-signalling pathway regulates morphogenesis in a large number of tissues. Detailed genetic and molecular studies have shown further that control of these processes by the Hedgehog ligands is typically mediated by control of the activities of the Patched-1 receptor that, in turn, indirectly controls the activity of smo. Interestingly, the primary sequence of mPtch1 predicts that, while potentially habouring a sterol-sensing domain (Carstea et al., 1997; Loftus et al., 1997), signalling cascades involving the direct association of SH3 or WW-domains with Ptch1 may also be involved in Hh-signalling. Our previous studies showed that a number of factors harbouring these domains can associate with the cytoplasmic C-terminal region of mPtch1 (Chang et al., 2010). These include the SH3-domains of signalling factors such as c-src, Grb2 and PIK3R2 (p85α) as well as factors harbouring WW-domains such as the E3 ubiquitin ligases, WWP2 and Smurf2. Supporting this was the recent observation that Drosophila Smurf (dSmurf) complexes Drosophila Patched (dPtch) (Huang et al., 2013).

Further evidence of Hh-pathways operating independently of smo was revealed in the mesenchymal dysplasia (mes) mouse (Sweet et al., 1996). The 32-bp deletion in this animal in the sequence encoding the mPtch1 C-terminus causes a truncation in this region of mPtch1 and the addition of a small amount of an unrelated, random sequence (Makino et al., 2001). A number of non-lethal defects arise in this mouse, including a block to mammary gland morphogenesis during puberty. As we have shown, this defect is not due to the lack of ovarian hormones but rather to the apparent unresponsiveness in cells of the mammary gland to these factors (Chang et al., 2012; Moraes et al., 2009). Despite these defects, the mes variant of the mPtch1 protein binds Shh-ligand with an affinity similar to the wild type mPtch1 (Nieuwenhuis et al., 2007) and appears to facilitate signalling through the canonical Hh-signalling pathway similar to cells with the full length protein (Harvey et al., 2014). Thus, in the context of the canonical Hh-pathway, the basis for blocked morphogenesis in the mes mammary gland is not apparent.

We hypothesized and showed previously, however, that the defect in the mes mammary gland could be rescued, albeit with delayed kinetics, by expressing an activated version of c-src (Chang et al., 2012). Among changes in the mammary glands of the mes/MMTV-c-srcAct mice was a significant increase in the levels of expression of ERα relative to mes mice alone and its accumulation in the cytoplasm of mammary epithelial cells. These data suggested that Hh-signalling in the mammary gland may require, at least in part, signalling through pathways that controlled the expression and activities of ERα and that forced expression of ERα in mes mice might also rescue the mes mammary phenotype. As we demonstrated here, conditional expression of an ERα transgene under the control of the MMTV promoter also overcame the block to mammary morphogenesis with kinetics similar to that of the MMTV-c-srcAct allele. Thus, these two distinct mouse models have revealed a novel Hh-signalling pathway, involving c-src and ERα, that plays an important role in postnatal mammary gland morphogenesis.

We note that the phenotype of the mes mice we reported in this and our previous paper (Chang et al., 2012) differs from a previous report (Moraes et al., 2009). In the latter paper, the blocked development of the mammary gland at puberty was not as robust as we have observed. The reason for the differences between these phenotypes is not apparent, particularly given that both labs backcrossed their animals onto C57Bl/6 backgrounds, albeit, using C57Bl/6 mice from colonies that first diverged in 1951 (Charles River (C57Bl/6N) versus Jackson Labs (C57Bl/6J)). We have characterized almost 40 mes mice on the C57Bl/6N background and have found only 3 with partial ductal development of mammary gland #4. Furthermore, for both the mes/MMTV-c-srcAct and mes/CERM animals, ductal growth was not apparent until after about 15 weeks, again supporting the stronger penetrance of mes mammary phenotype in our colony. Similar to Moraes et al., however, we observed that mixing FVB onto the mes/C57Bl/6N background had no effect on the mes phenotype (unpublished observation).

Our data also showed that stimulation by N-Shh of primary mammary epithelial cells activated Erk1/2 in both an ERα and c-src-dependent manner. Inhibition of activation of either factor, but not inhibition of smo, reduced or blocked the ability of N-Shh to stimulate Erk1/2. Thus, the non-canonical Hh-signalling pathway we identified previously appears to involve changes in the activities of ERα and c-src in mammary epithelial cells. The precise mechanism remains undefined. It is clear, however, that the activities of both c-src and ERα are required for the N-Shh-dependent activation of Erk1/2. In the presence of inhibitors that blocked the activities of ERα or c-src, respectively, N-Shh-dependent Erk1/2 activation was attenuated or blocked completely while treatment with the small molecule inhibitor of smo, SANT-1, had no effect. Thus, these data support the existence of a pathway stimulated by the Hh-ligands in mammary epithelial cells that operates through both c-src and ERα resulting in the activation of Erk1/2.

In both MMTV-c-srcAct and in CERM mice on the mes background, a significant increase in the levels of ERα relative to mes mice alone are observed in the mammary epithelial cells. The altered expression of ERα suggested that the level of its expression required for ductal morphogenesis at puberty in response to 17β-estradiol requires the normal activity of the mPtch1 C-terminus. This model does not preclude the possibility that the canonical Hh-pathway, signalling through smo, is also required. This possibility has not been strictly tested in the mouse mammary gland (i.e. conditional or tissue-specific knock out of smo in mammary epithelial and/or mesenchymal cells). However, mice harbouring conditional c-srcAct or ERα alleles are sufficient to overcome the block to the pubescent mammary morphogenesis and is associated with increased levels of ERα relative to mes mice alone.

Our data also revealed the mPtch1-dependent activation of the mammary stromal cells in vivo. Specifically, Alx4-expression was probed in mammary glands of wild type mice expressing mammary epithelial-restricted ERα or c-srcAct. In adult mice taken at 24 weeks, the stromally-restricted paired-like homeodomain transcription factor, Alx4, was induced in mammary fibroblasts whereas the wild type adults do not express Alx4 in these cells. We conclude that ERα or c-src expression in the luminal cells induced the expression of factors that stimulated the surrounding stromal cells. Interestingly, despite the rescue by ERα and c-src in the mes mice, induction of Alx4 expression was not observed in mes stromal cells. Thus, wild type mPtch1 appears to be required for stromal induction of Alx4 by adjacent mammary epithelial cells. The basis for the difference between mes and wild type mice has not been defined. We propose the possibility that ERα and c-src induce the expression of a Hh-ligand in mammary epithelial cells. This ligand then stimulates adjacent mesenchymal cells to express Alx4 but is dependent on the activities of wild type mPtch1in these cells. This model can be tested in reciprocal transplantation experiments between mes and wild type mammary glands. Regardless, these data offer further evidence for the role of components of the Hh-pathway in mediating signalling interactions between stromal and epithelial compartments in the developing mammary gland.

While the focus of this study was on Hh-signalling that operates, at least in part, through novel non-canonical signalling pathways, we also tested the response of primary mammary epithelial cells in culture to signal through the smo-dependent canonical pathway. Under the conditions of primary cell culture, we observed that primary mammary epithelial did not induce expression of the Hh-target gene, mPtch1, and only weakly induced mGli1. In contrast, primary mesenchymal cells from the same animals responded robustly to the same N-Shh ligand, as evident by mPtch1 and mGli1 expression levels being strongly induced. The lack of signalling in primary epithelial cells through the canonical pathway is consistent with the lack of response we observed for human cell lines derived from breast cancers or untransformed cells, including MCF7, MDA-MB-231 and MCF10a (Chang et al., 2010 and unpublished observations). For some of these latter lines, specifically MCF10a and MDA-MB-231, the expression of smo message appears to be absent, at least as determined by sensitive rtPCR studies of smo expression in these cells (Chang et al., 2010; Mukherjee et al., 2006; Zhang et al., 2009). The failure to stimulate the canonical pathway by N-Shh is distinct from the myriad of studies describing the consequences of altered expression of the downstream Hh-pathway components on cell growth, mobility, transformation or metastasis in mammary epithelial cell lines or, more often, breast cancer cell lines (for reviews, see Che et al., 2013; Cui et al., 2010; Hui et al., 2013; O’Toole et al., 2009). However, these studies have typically not described the activation of the canonical Hh-pathway upon stimulation by Hh-ligand. Indeed, evidence suggests that the “Hh repression state”, that is the state in which Gli3 acts as a repressor (Gli3rep), is required for normal mammary gland development (Hatsell and Cowin, 2006; Hui et al., 2013). It might be expected, therefore, that changes to the expression of downstream factors that overcome the dominance of the Gli3rep might lead to altered cell characteristics and might contribute to cell transformation as occurs, for example, in the MMTV-Gli1 mice (Fiaschi et al., 2009). However, our data suggest further that, while the mammary epithelial cells appear refractory to Hh-signalling through the canonical pathway, non-canonical signalling cascades can be invoked.

To conclude, combined with our data characterizing the effect of the MMTV-c-srcAct allele on development in the mes mammary gland, our data suggest that a novel Hh-signalling pathway involving the activities of ERα and c-src are required for mammary gland morphogenesis at puberty. These data suggest further that, for mammary epithelial cells, non-canonical pathways rather than the canonical Hh-pathway operating through smo are required for branching morphogenesis at this stage of mammary gland development.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

This project was funded by a grant to PAH by the Canadian Institutes of Health Research (MOP-97929).

Footnotes

Appendix A. Supporting information

Supplementary data associated with this article can be found in the online version at http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/j.ydbio.2014.04.007.

References

- Arao Y, Hamilton KJ, Ray MK, Scott G, Mishina Y, Korach KS. Estrogen receptor α AF-2 mutation results in antagonist reversal and reveals tissue selective function of estrogen receptor modulators. Proc Nat Acad Sci U S A. 2011;108:14986–14991. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1109180108. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Arnal J-F, Fontaine C, Abot A, Valera M-C, Laurell H, Gourdy P, Lenfant F. Lessons from the dissection of the activation functions (AF-1 and AF-2) of the estrogen receptor alpha in vivo. Steroids. 2013;78:576–582. doi: 10.1016/j.steroids.2012.11.011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Arnold SF, Obourn JD, Jaffe H, Notides AC. Phosphorylation of the human estrogen receptor on tyrosine 537 in vivo and by src family tyrosine kinases in vitro. Mol Endocrinol. 1995;9:24–33. doi: 10.1210/mend.9.1.7539106. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bunone G, Briand PA, Miksicek RJ, Picard D. Activation of the unliganded estrogen receptor by EGF involves the MAP kinase pathway and direct phosphorylation. EMBO J. 1996;15:2174–2183. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Capurro MI, Shi W, Filmus J. LRP1 mediates the Shh-induced endocytosis of the GPC3-Shh complex. J Cell Sci. 2012 doi: 10.1242/jcs.098889. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Carstea ED, Morris JA, Coleman KG, Loftus SK, Zhang D, Cummings C, Gu J, Rosenfeld MA, Pavan WJ, Krizman DB, Nagle J, Polymeropoulos MH, Sturley SL, Ioannou YA, Higgins ME, Comly M, Cooney A, Brown A, Kaneski CR, Blanchette-Mackie EJ, Dwyer NK, Neufeld EB, Chang TY, Liscum L, Strauss JF, 3, Ohno K, Zeigler M, Carmi R, Sokol J, Markie D, O’Neill RR, Van Diggelen OP, Elleder M, Patterson MC, Brady RO, Vanier MT, Pentchev PG, Tagle DA. Niemann-Pick C1 disease gene: homology to mediators of cholesterol homeostasis. Science. 1997;277:228–231. doi: 10.1126/science.277.5323.228. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Castoria G, Barone MV, Di Domenico M, Bilancio A, Ametrano D, Migliaccio A, Auricchio F. Non-transcriptional action of oestradiol and progestin triggers DNA synthesis. EMBO J. 1999;18:2500–2510. doi: 10.1093/emboj/18.9.2500. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Castoria G, Giovannelli P, Lombardi M, De Rosa C, Giraldi T, De Falco A, Barone MV, Abbondanza C, Migliaccio A, Auricchio F. Tyrosine phosphorylation of estradiol receptor by Src regulates its hormone-dependent nuclear export and cell cycle progression in breast cancer cells. Oncogene. 2012;31:4868–4877. doi: 10.1038/onc.2011.642. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chang H, Balenci L, Okolowsky N, Muller WJ, Hamel PA. Mammary epithelial-restricted expression of activated c-src rescues the block to mammary gland morphogenesis due to the deletion of the C-terminus of Patched-1. Dev Biol. 2012;370:187–197. doi: 10.1016/j.ydbio.2012.07.027. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chang H, Li Q, Moraes RC, Lewis MT, Hamel PA. Activation of Erk by sonic Hedgehog independent of canonical Hedgehog signalling. Int J Biochem Cell Biol. 2010;42:1462–1471. doi: 10.1016/j.biocel.2010.04.016. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Che J, Zhang F-Z, Zhao C-Q, Hu X-D, Fan S-J. Cyclopamine is a novel Hedgehog signaling inhibitor with significant anti-proliferative, anti-invasive and anti-estrogenic potency in human breast cancer cells. Oncol Lett. 2013;5:1417–1421. doi: 10.3892/ol.2013.1195. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chen D, Washbrook E, Sarwar N, Bates GJ, Pace PE, Thirunuvakkarasu V, Taylor J, Epstein RJ, Fuller-Pace FV, Egly J-M, Coombes RC, Ali S. Phosphorylation of human estrogen receptor alpha at serine 118 by two distinct signal transduction pathways revealed by phosphorylation-specific antisera. Oncogene. 2002;21:4921–4931. doi: 10.1038/sj.onc.1205420. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Couse JF, Curtis Hewitt S, Korach KS. Receptor null mice reveal contrasting roles for estrogen receptor alpha and beta in reproductive tissues. J Steroid Biochem Mol Biol. 2000;74:287–296. doi: 10.1016/s0960-0760(00)00105-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cui W, Wang L-H, Wen Y-Y, Song M, Li B-L, Chen X-L, Xu M, An S-X, Zhao J, Lu Y-Y, Mi X-Y, Wang E-H. Expression and regulation mechanisms of Sonic Hedgehog in breast cancer. Cancer Sci. 2010;101:927–933. doi: 10.1111/j.1349-7006.2010.01495.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Di Domenico M, Castoria G, Bilancio A, Migliaccio A, Auricchio F. Estradiol activation of human colon carcinoma-derived Caco-2 cell growth. Cancer Res. 1996;56:4516–4521. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Díaz-Cruz ES, Sugimoto Y, Gallicano GI, Brueggemeier RW, Furth PA. Comparison of increased aromatase versus ERα in the generation of mammary hyperplasia and cancer. Cancer Res. 2011;71:5477–5487. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-10-4652. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fiaschi M, Rozell B, Bergstrom A, Toftgard R. Development of mammary tumors by conditional expression of GLI1. Cancer Res. 2009;69:4810–4817. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-08-3938. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Frech MS, Halama ED, Tilli MT, Singh B, Gunther EJ, Chodosh LA, Flaws JA, Furth PA. Deregulated estrogen receptor α expression in mammary epithelial cells of transgenic mice results in the development of ductal carcinoma in situ. Cancer Res. 2005;65:681–685. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Frech MS, Torre KM, Robinson GW, Furth PA. Loss of cyclin D1 in concert with deregulated estrogen receptor alpha expression induces DNA damage response activation and interrupts mammary gland morphogenesis. Oncogene. 2008;27:3186–3193. doi: 10.1038/sj.onc.1210974. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hanke JH, Gardner JP, Dow RL, Changelian PS, Brissette WH, Weringer EJ, Pollok BA, Connelly PA. Discovery of a novel, potent, and Src family-selective tyrosine kinase inhibitor study of Lck- and FynT- dependent T cell activation. J Biol Chem. 1996;271:695–701. doi: 10.1074/jbc.271.2.695. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Harvey MC, Fleet A, Okolowsky N, Hamel PA. Distinct effects of the mesenchymal dysplasia variant of murine patched-1 on canonical and non-canonical Hedgehog-signalling pathways. J Biol Chem. 2014 doi: 10.1074/jbc.M113.514844. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hatsell SJ, Cowin P. Gli3-mediated repression of Hedgehog targets is required for normal mammary development. Development. 2006;133:3661–3670. doi: 10.1242/dev.02542. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Haynes MP, Li L, Sinha D, Russell KS, Hisamoto K, Baron R, Collinge M, Sessa WC, Bender JR. Src kinase mediates phosphatidylinositol 3-kinase/Akt-dependent rapid endothelial nitric-oxide synthase activation by estrogen. J Biol Chem. 2003;278:2118–2123. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M210828200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Heldring N, Pike A, Andersson S, Matthews J, Cheng G, Hartman J, Tujague M, Strom A, Treuter E, Warner M, Gustafsson J-A. Estrogen receptors: how do they signal and what are their targets. Physiol Rev. 2007;87:905–931. doi: 10.1152/physrev.00026.2006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hruska KS, Tilli MT, Ren S, Cotarla I, Kwong T, Li M, Fondell JD, Hewitt JA, Koos RD, Furth PA, Flaws JA. Conditional over-expression of estrogen receptor alpha in a transgenic mouse model. Transgenic Res. 2002;11:361–372. doi: 10.1023/a:1016376100186. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Huang S, Zhang Z, Zhang C, Lv X, Zheng X, Chen Z, Sun L, Wang H, Zhu Y, Zhang J, Yang S, Lu Y, Sun Q, Tao Y, Liu F, Zhao Y, Chen D. Activation of Smurf E3 ligase promoted by smoothened regulates Hedgehog signaling through targeting patched turnover. PLoS Biol. 2013;11:e1001721. doi: 10.1371/journal.pbio.1001721. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hudson R, Taniguchi-Sidle A, Boras K, Wiggan O, Hamel PA. Alx-4, a transcriptional activator whose expression is restricted to sites of epithelial-mesenchymal interactions. Dev Dyn. 1998;213:159–169. doi: 10.1002/(SICI)1097-0177(199810)213:2<159::AID-AJA1>3.0.CO;2-F. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hui M, Cazet A, Nair R, Watkins DN, O’Toole SA, Swarbrick A. The Hedgehog signalling pathway in breast development, carcinogenesis and cancer therapy. Breast Cancer Res. 2013;15:203. doi: 10.1186/bcr3401. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Improta-Brears T, Whorton AR, Codazzi F, York JD, Meyer T, McDonnell DP. Estrogen-induced activation of mitogen-activated protein kinase requires mobilization of intracellular calcium. Proc Nat Acad Sci U S A. 1999;96:4686–4691. doi: 10.1073/pnas.96.8.4686. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Joshi PA, Chang H, Hamel PA. Loss of Alx4, a stromally-restricted homeodomain protein, impairs mammary epithelial morphogenesis. Dev Biol. 2006;297:284–294. doi: 10.1016/j.ydbio.2006.05.032. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kameda C, Nakamura M, Tanaka H, Yamasaki A, Kubo M, Tanaka M, Onishi H, Katano M. Oestrogen receptor-alpha contributes to the regulation of the Hedgehog signalling pathway in ERalpha-positive gastric cancer. Br J Cancer. 2010;102:738–747. doi: 10.1038/sj.bjc.6605517. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kim H, Laing M, Muller W. c-Src-null mice exhibit defects in normal mammary gland development and ERalpha signaling. Oncogene. 2005;24:5629–5636. doi: 10.1038/sj.onc.1208718. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Klinge CM. Estrogen receptor interaction with co-activators and co-repressors. Steroids. 2000;65:227–251. doi: 10.1016/s0039-128x(99)00107-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Koga K, Nakamura M, Nakashima H, Akiyoshi T, Kubo M, Sato N, Kuroki S, Nomura M, Tanaka M, Katano M. Novel link between estrogen receptor alpha and Hedgehog pathway in breast cancer. Anticancer Res. 2008;28:731–740. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kousteni S, Bellido T, Plotkin LI, O’Brien CA, Bodenner DL, Han L, Han K, DiGregorio GB, Katzenellenbogen JA, Katzenellenbogen BS, Roberson PK, Weinstein RS, Jilka RL, Manolagas SC. Nongenotropic, sex-nonspecific signaling through the estrogen or androgen receptors: dissociation from transcriptional activity. Cell. 2001;104:719–730. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lannigan DA. Estrogen receptor phosphorylation. Steroids. 2003;68:1–9. doi: 10.1016/s0039-128x(02)00110-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Li L, Hisamoto K, Kim KH, Haynes MP, Bauer PM, Sanjay A, Collinge M, Baron R, Sessa WC, Bender JR. Variant estrogen receptor-c-Src molecular interdependence and c-Src structural requirements for endothelial NO synthase activation. Proc Nat Acad Sci U S A. 2007;104:16468–16473. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0704315104. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Loftus SK, Morris JA, Carstea ED, Gu JZ, Cummings C, Brown A, Ellison J, Ohno K, Rosenfeld MA, Tagle DA, Pentchev PG, Pavan WJ. Murine model of Niemann-Pick C disease: mutation in a cholesterol homeostasis gene. Science. 1997;277:232–235. doi: 10.1126/science.277.5323.232. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lubahn DB, Moyer JS, Golding TS, Couse JF, Korach KS, Smithies O. Alteration of reproductive function but not prenatal sexual development after insertional disruption of the mouse estrogen receptor gene. Proc Nat Acad Sci U S A. 1993;90:11162–11166. doi: 10.1073/pnas.90.23.11162. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Makino S, Masuya H, Ishijima J, Yada Y, Shiroishi T. A spontaneous mouse mutation, mesenchymal dysplasia (mes), is caused by a deletion of the most C-terminal cytoplasmic domain of patched (ptc) Dev Biol. 2001;239:95–106. doi: 10.1006/dbio.2001.0419. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mangelsdorf DJ, Thummel C, Beato M, Herrlich P, Schütz G, Umesono K, Blumberg B, Kastner P, Mark M, Chambon P, Evans RM. The nuclear receptor superfamily: the second decade. Cell. 1995;83:835–839. doi: 10.1016/0092-8674(95)90199-x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McGlynn LM, Tovey S, Bartlett JMS, Doughty J, Cooke TG, Edwards J. Interactions between MAP kinase and oestrogen receptor in human breast cancer. Eur J Cancer. 2013;49:1176–1186. doi: 10.1016/j.ejca.2012.11.020. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Miermont AM, Parrish AR, Furth PA. Role of ERalpha in the differential response of Stat5a loss in susceptibility to mammary preneoplasia and DMBA-induced carcinogenesis. Carcinogenesis. 2010;31:1124–1131. doi: 10.1093/carcin/bgq048. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Migliaccio A, Castoria G, Di Domenico M, De Falco A, Bilancio A, Lombardi M, Barone MV, Ametrano D, Zannini MS, Abbondanza C, Auricchio F. Steroid-induced androgen receptor-oestradiol receptor beta-Src complex triggers prostate cancer cell proliferation. EMBO J. 2000;19:5406–5417. doi: 10.1093/emboj/19.20.5406. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Migliaccio A, Di Domenico M, Castoria G, De Falco A, Bontempo P, Nola E, Auricchio F. Tyrosine kinase/p21ras/MAP-kinase pathway activation by estradiol-receptor complex in MCF-7 cells. EMBO J. 1996;15:1292–1300. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Migliaccio A, Piccolo D, Castoria G, Di Domenico M, Bilancio A, Lombardi M, Gong W, Beato M, Auricchio F. Activation of the Src/p21ras/Erk pathway by progesterone receptor via cross-talk with estrogen receptor. EMBO J. 1998;17:2008–2018. doi: 10.1093/emboj/17.7.2008. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Moraes RC, Chang H, Harrington N, Landua JD, Prigge JT, Lane TF, Wainwright BJ, Hamel PA, Lewis MT. Ptch1 is required locally for mammary gland morphogenesis and systemically for ductal elongation. Development. 2009;136:1423–1432. doi: 10.1242/dev.023994. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mukherjee S, Frolova N, Sadlonova A, Novak Z, Steg A, Page GP, Welch DR, Lobo-Ruppert SM, Ruppert JM, Johnson MR, Frost AR. Hedgehog signaling and response to cyclopamine differ in epithelial and stromal cells in benign breast and breast cancer. Cancer Biol Ther. 2006;5:674–683. doi: 10.4161/cbt.5.6.2906. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nieuwenhuis E, Barnfield PC, Makino S, Hui C-C. Epidermal hyperplasia and expansion of the interfollicular stem cell compartment in mutant mice with a C-terminal truncation of Patched1. Dev Biol. 2007;308:547–560. doi: 10.1016/j.ydbio.2007.06.016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Niranjan B, Buluwela L, Yant J, Perusinghe N, Atherton A, Phippard D, Dale T, Gusterson B, Kamalati T. HGF/SF: a potent cytokine for mammary growth, morphogenesis and development. Development. 1995;121:2897–2908. doi: 10.1242/dev.121.9.2897. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- O’Toole SA, Swarbrick A, Sutherland RL. The Hedgehog signalling pathway as a therapeutic target in early breast cancer development. Expert Opin Ther Targets. 2009;13:1095–1103. doi: 10.1517/14728220903130612. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pedram A, Razandi M, Kim JK, O’Mahony F, Lee EY, Luderer U, Levin ER. Developmental phenotype of a membrane only estrogen receptor alpha (MOER) mouse. J Biol Chem. 2009;284:3488–3495. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M806249200. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Qu S, Li L, Wisdom R. Alx-4: cDNA cloning and characterization of a novel paired-type homeodomain protein. Gene. 1997a;203:217–223. doi: 10.1016/s0378-1119(97)00497-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Qu S, Niswender KD, Ji Q, Van der Meer R, Keeney D, Magnuson MA, Wisdom R. Polydactyly and ectopic ZPA formation in Alx-4 mutant mice. Development. 1997b;124:3999–4008. doi: 10.1242/dev.124.20.3999. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Qu S, Tucker SC, Ehrlich JS, Levorse JM, Flaherty LA, Wisdom R, Vogt TF. Mutations in mouse Aristaless-like4 cause Strong’s luxoid polydactyly. Development. 1998;125:2711–2721. doi: 10.1242/dev.125.14.2711. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rasmussen SB, Young LJT, Smith GH. Preparing Mammary Gland Whole Mounts from Mice. Plenum Publishers; New York: 2000. [Google Scholar]

- Sasaki H, Hui C, Nakafuku M, Kondoh H. A binding site for Gli proteins is essential for HNF-3beta floor plate enhancer activity in transgenics and can respond to Shh in vitro. Development. 1997;124:1313–1322. doi: 10.1242/dev.124.7.1313. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Song RX-D, McPherson RA, Adam L, Bao Y, Shupnik M, Kumar R, Santen RJ. Linkage of rapid estrogen action to MAPK activation by ERalpha-Shc association and Shc pathway activation. Mol Endocrinol. 2002;16:116–127. doi: 10.1210/mend.16.1.0748. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sun J, Zhou W, Kaliappan K, Nawaz Z, Slingerland JM. ERα phosphorylation at Y537 by Src triggers E6-AP-ERα binding, ERα ubiquitylation, promoter occupancy, and target gene expression. Mol Endocrinol. 2012;26:1567–1577. doi: 10.1210/me.2012-1140. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sweet HO, Bronson RT, Donahue LR, Davisson MT. Mesenchymal dysplasia: a recessive mutation on chromosome 13 of the mouse. J Hered. 1996;87:87–95. doi: 10.1093/oxfordjournals.jhered.a022981. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tilli MT, Frech MS, Steed ME, Hruska KS, Johnson MD, Flaws JA, Furth PA. Introduction of estrogen receptor-alpha into the tTA/TAg conditional mouse model precipitates the development of estrogen-responsive mammary adenocarcinoma. Am J Pathol. 2003;163:1713–1719. doi: 10.1016/s0002-9440(10)63529-8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Varricchio L, Migliaccio A, Castoria G, Yamaguchi H, De Falco A, Domenico MD, Giovannelli P, Farrar W, Appella E, Auricchio F. Inhibition of estradiol receptor/Src association and cell growth by an estradiol eeceptor α tyrosine-phosphorylated peptide. Mol Cancer Res. 2007;5:1213–1221. doi: 10.1158/1541-7786.MCR-07-0150. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wakeling AE, Dukes M, Bowler J. A potent specific pure antiestrogen with clinical potential. Cancer Res. 1991;51:3867–3873. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Webster MA, Cardiff RD, Muller WJ. Induction of mammary epithelial hyperplasias and mammary tumors in transgenic mice expressing a murine mammary tumor virus/activated c-src fusion gene. Proc Nat Acad Sci U S A. 1995;92:7849–7853. doi: 10.1073/pnas.92.17.7849. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhang X, Harrington N, Moraes RC, Wu M-F, Hilsenbeck SG, Lewis MT. Cyclopamine inhibition of human breast cancer cell growth independent of Smoothened (Smo) Breast Cancer Res Treat. 2009;115:505–521. doi: 10.1007/s10549-008-0093-3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.