Abstract

NOMENCLATURE The following nomenclature will be used in this article:

Names of genes are written in italicized upper-case letters, e.g., ABI4.

Names of proteins are written in non-italicized upper-case letters, e.g., ABI4.

Names of mutants are written in italicized lower-case letters, e.g., abi4.

The juvenile-to-adult and vegetative-to-reproductive phase transitions are major determinants of plant reproductive success and adaptation to the local environment. Understanding the intricate molecular genetic and physiological machinery by which environment regulates juvenility and floral signal transduction has significant scientific and economic implications. Sugars are recognized as important regulatory molecules that regulate cellular activity at multiple levels, from transcription and translation to protein stability and activity. Molecular genetic and physiological approaches have demonstrated different aspects of carbohydrate involvement and its interactions with other signal transduction pathways in regulation of the juvenile-to-adult and vegetative-to-reproductive phase transitions. Sugars regulate juvenility and floral signal transduction through their function as energy sources, osmotic regulators and signaling molecules. Interestingly, sugar signaling has been shown to involve extensive connections with phytohormone signaling. This includes interactions with phytohormones that are also important for the orchestration of developmental phase transitions, including gibberellins, abscisic acid, ethylene, and brassinosteroids. This article highlights the potential roles of sugar-hormone interactions in regulation of floral signal transduction, with particular emphasis on Arabidopsis thaliana mutant phenotypes, and suggests possible directions for future research.

Keywords: Arabidopsis thaliana, florigenic and antiflorigenic signaling, juvenile-to-adult phase transition, juvenility, signal transduction, sugar-hormone interactions, vegetative-to-reproductive phase transition

Introduction

The greatest advances in our understanding of the genetic regulation of developmental transitions have derived from studying the vegetative-to-reproductive phase transition in several dicot and monocot species. This has led to the elucidation of multiple environmental and endogenous pathways that promote, enable and repress floral induction (reviewed in Matsoukas et al., 2012). The photoperiodic (Kardailsky et al., 1999; Kobayashi et al., 1999) and vernalization (Schmitz et al., 2008) pathways regulate time to flowering in response to environmental signals such as daylength, light and temperature, whereas the autonomous (Jeong et al., 2009), aging (Yang et al., 2013; Yu et al., 2013) and gibberellin (GA)-dependent (Porri et al., 2012) pathways monitor endogenous indicators of the plant's age and physiological status. In addition, other factors and less characterized pathways also play a role in regulation of floral signal transduction. These include ethylene (Achard et al., 2006), brassinosteroids (BRs; Domagalska et al., 2010), salicylic acid (Jin et al., 2008) and cytokinins (D'aloia et al., 2011).

The photoperiodic pathway is probably the most conserved of the floral induction pathways. It is known for its promotive effect by relaying light and photoperiodic timing signals to floral induction (reviewed in Matsoukas et al., 2012). This pathway involves genes such as PHYTOCHROMES (PHYs; Sharrock and Quail, 1989; Clack et al., 1994) and CRYPTOCHROMES (CRYs; Ahmad and Cashmore, 1993; Guo et al., 1998; Kleine et al., 2003), which are involved in the regulation of light signal inputs. Other genes such as GIGANTEA (GI; Fowler et al., 1999), CIRCADIAN CLOCK ASSOCIATED1 (CCA1; Wang et al., 1997), and LATE ELONGATED HYPOCOTYL (LHY; Schaffer et al., 1998) are components of the circadian clock, whereas CONSTANS (CO), FLOWERING LOCUS T (FT; Kardailsky et al., 1999; Kobayashi et al., 1999), TWIN SISTER OF FT (TSF; Yamaguchi et al., 2005), and FLOWERING LOCUS D (FD; Abe et al., 2005) encode proteins that specifically regulate floral induction. The actions of all pathways ultimately converge to control the expression of so-called floral pathway integrators (FPIs), which include FT (Corbesier et al., 2007), TSF (Yamaguchi et al., 2005), SUPPRESSOR OF CONSTANS1 (SOC1; Yoo et al., 2005), and AGAMOUS-LIKE24 (AGL24; Lee et al., 2008; Liu et al., 2008). These act on floral meristem identity (FMI) genes LEAFY (LFY; Lee et al., 2008), FRUITFUL (FUL; Melzer et al., 2008), and APETALA1 (AP1; Wigge et al., 2005; Yamaguchi et al., 2005), which result in floral initiation. On the other hand, pathways that enable floral induction regulate the expression of floral repressors or translocatable florigen antagonists, known as antiflorigens (reviewed in Matsoukas et al., 2012). The pathways that regulate the floral repressor FLOWERING LOCUS C (FLC) are the best-characterized (reviewed in Michaels, 2009).

The vegetative-to-reproductive phase transition is preceded by the juvenile-to-adult phase transition within the vegetative phase (reviewed in Poethig, 1990, 2013; Matsoukas et al., 2013; Matsoukas, 2014). During the juvenile phase plants are incapable of initiating reproductive development and are insensitive to environmental stimuli such as photoperiod and vernalization, which induce flowering in adult plants (Matsoukas et al., 2013; Matsoukas, 2014; Sgamma et al., 2014). The juvenile-to-adult phase transition is accompanied by a decrease in microRNA156 (miR156A/miR156C) abundance and a concomitant increase in abundance of miR172, as well as the SQUAMOSA PROMOTER BINDING PROTEIN-LIKE (SPL3/4/5) transcription factors (TFs; Wang et al., 2009; Wu et al., 2009; Jung et al., 2011, 2012; Kim et al., 2012). Expression of miR172 activates FT transcription in leaves through repression of AP2-like transcripts SCHLAFMÜTZE (SMZ), SCHNARCHZAPFEN (SNZ), and TARGET OF EAT 1-3 (TOE1-3; Jung et al., 2007, 2011; Mathieu et al., 2009), whereas the increase in SPLs at the shoot apical meristem (SAM), leads to the transcription of FMI genes (Schwab et al., 2005; Schwarz et al., 2008; Wang et al., 2009; Yamaguchi et al., 2009). Therefore, from a molecular perspective juvenility can be defined as the period during which the abundance of antiflorigenic signals such as miR156/miR157 is sufficiently high to repress the transcription of FT and SPL genes (Matsoukas, 2014).

Carbohydrates serve diverse functions in plants ranging from energy sources, osmotic regulators, storage molecules, and structural components to intermediates for the synthesis of other organic molecules (reviewed in Rolland et al., 2006; Smeekens et al., 2010; Eveland and Jackson, 2012). Carbohydrates also act as signaling molecules (Moore et al., 2003) and by their interaction with mineral networks (Zakhleniuk et al., 2001; Lloyd and Zakhleniuk, 2004) affect the juvenile-to-adult and vegetative-to-reproductive phase transitions (Matsoukas et al., 2013). Interestingly, sugar signaling has been shown to involve extensive interaction with hormone signaling (Zhou et al., 1998; Arenas-Huertero et al., 2000; Moore et al., 2003). This includes interactions with hormones that are also important for the regulation of juvenile-to-adult and vegetative-to-reproductive phase transitions, including GAs (Yuan and Wysocka-Diller, 2006), abscisic acid (ABA; Arenas-Huertero et al., 2000; Laby et al., 2000), ethylene (Zhou et al., 1998), and BRs (Goetz et al., 2000; Schluter et al., 2002). Several molecular mechanisms that mediate sugar responses have been identified in plants (reviewed in Rolland et al., 2006; Smeekens et al., 2010). The best examples involve hexokinase (HXK; Moore et al., 2003), trehalose-6-phosphate (Tre6P; Van Dijken et al., 2004) and the sucrose non-fermenting 1-related protein kinase1 (SnRK1; Baena-Gonzalez et al., 2007) complex. SnRK1 has a role when sugars are in extremely limited supply, whereas HXK and Tre6P play a role in the presence of excess sugar.

The panoptic themes of floral signal transduction, sugar sensing and signaling, and hormonal regulation of growth and development have attracted much attention, and many comprehensive review articles have been published (Rolland et al., 2006; Amasino, 2010; Smeekens et al., 2010; Depuydt and Hardtke, 2011; Huijser and Schmid, 2011; Andres and Coupland, 2012). This article, however, focuses specifically on sugar-hormone interactions and their involvement in regulation of floral signal transduction, with particular emphasis on Arabidopsis thaliana mutant phenotypes. The review is divided into two sections: the first provides several pieces of evidence on the interactions between sugars and different hormones in floral induction; whereas the second describes potential mechanisms that might be involved in regulation of floral signal transduction, in response to sugar-hormone interplay.

Sugar/hormone interactions and floral signal transduction

The sugar and gibberellin signaling crosstalk

GAs are a group of molecules with a tetracyclic diterpenoid structure that function as plant growth regulators influencing a range of developmental processes. Several Arabidopsis mutants in the GA signal transduction and GA biosynthesis pathway have been isolated (Table 1; Peng and Harberd, 1993; Peng et al., 1997; Hedden and Phillips, 2000). Null mutations in the early steps of GA biosynthesis (e.g., ga1-3) do not flower in short days (SDs), whereas weak mutants (e.g., ga1-6; Koornneef and Van Der Veen, 1980), or GA signal transduction mutants [e.g., gibberellic acid insensitive (gai)], flower later than wild type (WT; Peng and Harberd, 1993). In contrast, mutants with increased GA signaling such as rga like2 (rgl2; Cheng et al., 2004; Yu et al., 2004) and spindly (spy; Jacobsen and Olszewski, 1993) have an early flowering phenotype. Evidence has been provided that both RGL2 and SPY might be involved in carbohydrate regulation of floral initiation, as mutation in both loci confers insensitivity to inhibiting glucose concentrations (Yuan and Wysocka-Diller, 2006). SPY, an O-linked B-N-acetylglucosamine transferase was shown to interact with the GI in yeast (Tseng et al., 2004). Mutants impaired in GI have a late flowering and starch-excess phenotype (Eimert et al., 1995). The interaction between SPY and GI suggests that functions of these proteins might be related, and that SPY might be a pleiotropic circadian clock regulator (Tseng et al., 2004; Penfield and Hall, 2009). In addition, the early flowering phenotype of the glucose insensitive spy may be via FT, as spy4 suppresses the reduction of CO and FT mRNA in gi2 genotypes (Tseng et al., 2004). This indicates that SPY functions in the photoperiod pathway upstream of CO and FT, involving glucose and GA metabolism-related events. Interestingly, it has been suggested that SPY4 may play a central role in the regulation of GA/cytokinin crosstalk during plant development (Greenboim-Wainberg et al., 2005).

Table 1.

List of genes in Arabidopsis thaliana that regulate floral signal transduction in response to sugar-hormone interplay.

| Gene name | Abbreviation | Allelic | Gene identifier | Description | Flowering mutant phenotypea | References | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| SD | LD | ||||||

| SUGAR-GA SIGNALING CROSSTALK | |||||||

| GA REQUIRING 1-3 | GA1-3 | CPS, KSA | At4g02780 | GA biosynthesis; ent-copalyl diphosphate synthase/magnesium ion binding | No phenotype | No phenotype | Koornneef and Van Der Veen, 1980 |

| GA REQUIRING 1-6 | GA1-6 | CPS, KSA | At4g02780 | GA biosynthesis | Late | Late | Koornneef and Van Der Veen, 1980 |

| GIBBERELLIC ACID INSENSITIVE | GAI | GRAS-3, RGA2 | At1g14920 | TFb; repressor of GA responses; involved in GA mediated signaling | Late | Late | Peng and Harberd, 1993; Peng et al., 1997; Hedden and Phillips, 2000 |

| RGA LIKE 2 | RGL 2 | GRAS-15, SCL19, DELLA protein RGL2 | At3g03450 | TF; SCARECROW-like; GA signaling; encodes a DELLA protein | Early | Early | Cheng et al., 2004; Tyler et al., 2004; Yu et al., 2004 |

| SPINDLY | SPY | n/a | At3g11540 | Repressor of GA responses; positive regulator of cytokinin signaling; glucose insensitive mutant | Early | Early | Jacobsen and Olszewski, 1993; Swain et al., 2002; Greenboim-Wainberg et al., 2005 |

| GIGANTEA | GI | n/a | At1g22770 | Starch excess mutant; component of the circadian oscillator | Late | Similar or later than WT | Eimert et al., 1995; Tseng et al., 2004; Penfield and Hall, 2009 |

| LEAFY | LFY | MAC9_13 | At5g61850 | TF; sugar and GA regulated | No phenotype | No phenotype | Blazquez et al., 1998; Eriksson et al., 2006 |

| SUGAR-ABA SIGNALING CROSSTALK | |||||||

| ABA DEFICIENT 2 | ABA2 | GIN1, ISI4, SAN3, SDR1, SIS4, SRE1 | At1g52340 | Oxidoreductase; molecular link between sugar signaling and hormone biosynthesis | Early | Early | Laby et al., 2000; Rook et al., 2001; Cheng et al., 2002 |

| ABA DEFICIENT 3 | ABA3 | GIN5, ISI2, SIS3 | At1g16540 | Involved in the conversion of ABA-aldehyde to ABA; glucose insensitive mutant; mo-molybdopterin cofactor sulfurase | Early | Early | Leon-Kloosterziel et al., 1996; Arenas-Huertero et al., 2000; Bittner et al., 2001 |

| ABA INSENSITIVE 3 | ABI3 | SIS10 | At3g24650 | TF; molecular link between sugar signaling and hormone biosynthesis | Early | Early | Giraudat et al., 1992; Huang et al., 2008 |

| ABA INSENSITIVE 4 | ABI4 | GIN6, ISI3, SIS5, SUN6 | At2g40220 | TF; molecular link between sugar signaling and hormone biosynthesis | Similar or slightly earlier than WT | Similar to WT | Finkelstein et al., 1998; Arenas-Huertero et al., 2000; Matsoukas et al., 2013 |

| CIRCADIAN CLOCK ASSOCIATED 1 | CCA1 | MYB-RELATED DNA BINDING PROTEIN | At2g46830 | TF; component of the circadian oscillator | Early | Similar to WT | Mizoguchi et al., 2002; Hanano et al., 2006 |

| TIMING OF CAB EXPRESSION 1 | TOC1 | ABI3 INTERACTING PROTEIN 1, PRR1 | At5g61380 | TF; contributes to the plant fitness (carbon fixation, biomass) by influencing the circadian oscillator period | Early | Early | Kreps and Simon, 1997; Somers et al., 1998; Kurup et al., 2000; Pokhilko et al., 2013 |

| SUGAR-ETHYLENE SIGNALING CROSSTALK | |||||||

| CONSTITUTIVE TRIPLE RESPONSE1 | CTR1 | GIN4, SIS1 | At5g03730 | Kinase; negative regulator of ethylene signaling; sugar signaling | Late | Late | Gibson et al., 2001; Cheng et al., 2002; Achard et al., 2007 |

| ETHYLENE INSENSITIVE 2 | EIN2 | CKR1, ERA3 | At5g03280 | Transporter; involved in ethylene signal transduction | Late | Late | Su and Howell, 1992; Fujita and Syono, 1996; Zhou et al., 1998; Alonso et al., 1999 |

| ETHYLENE OVERPRODUCER 1 | ETO1 | n/a | At3g51770 | Protein binding; promote ethylene biosynthesis | Early | Early | Bleecker et al., 1988; Guzman and Ecker, 1990; Roman et al., 1995; Chae et al., 2003 |

| ETHYLENE RESPONSE 1 | ETR1 | EIN1 | At1g66340 | Ethylene binding; ethylene receptor; protein histidine kinase | Late | Late | Bleecker et al., 1988; Guzman and Ecker, 1990; Chang et al., 1993; Chen and Bleecker, 1995 |

| ETHYLENE RESPONSE 2 | ETR2 | n/a | At3g23150 | Negative regulation of ethylene mediated signaling pathway; glycogen synthase kinase3; protein histidine kinase | Early | Similar or slightly later than WT | Sakai et al., 1998 |

| SUGAR-BR SIGNALING CROSSTALK | |||||||

| BRASSINOSTEROID, LIGHT AND SUGAR 1 | BLS1 | n/a | n/ac | Component for BR and light responsiveness; involved in sugar signaling | Late | Late | Laxmi et al., 2004 |

| CONSTITUTIVE PHOTOMORPHOGENESIS AND DWARFISM | CPD | CBB3, CYP90, DWARF3 | At5g05690 | Electron carrier; heme binding; iron ion binding; monooxygenase; oxygen binding; under circadian and light control | Late | Late | Szekeres et al., 1996; Li and Chory, 1997; Choe et al., 1998; Domagalska et al., 2007 |

| DE-ETIOLATED 2 | DET2 | DWARF6 | At2g38050 | Similar to mammalian steroid-5-alpha-reductase; involved in the brassinolide biosynthetic pathway | Late | Late | Li et al., 1996; Noguchi et al., 1999; Tanaka et al., 2005 |

The flowering mutant phenotype compared to WT, under short (SD; 8 h light) and long day (LD; 16 h light) conditions.

TF, transcription factor.

The mutation has been mapped within a 1.4 Mb region of chromosome 5 (Laxmi et al., 2004).

Lines of evidence have demonstrated that there is a synergistic interaction between GAs and sucrose in the activation of LFY transcription (Blazquez et al., 1998; Eriksson et al., 2006). These pieces of evidence suggest a further link between GAs with sugar metabolism-related events and floral signal transduction. The effects of GA-sugar interplay on regulation of floral induction might be transduced by the GIBBERELLIN INSENSITIVE DWARF1 (GID1), which act upstream of the DELLA (Feng et al., 2008; Harberd et al., 2009), and PHYTOCHROME-INTERACTING FACTOR (PIF; De Lucas et al., 2008; Nozue et al., 2011; Stewart et al., 2011) family of bHLH factors.

The sugar-ABA signaling crosstalk

ABA is regarded as a general inhibitor of floral induction. This is indicated in Arabidopsis where mutants deficient (e.g., aba2, aba3) in or insensitive [e.g., aba insensitive4 (abi4)] to ABA are early flowering (Table 1; Martinez-Zapater et al., 1994). On the other hand, mutants with high ABA levels [e.g., no hydrotropic response (nhr1)] flower late or even later than WT under non-inductive SDs (Quiroz-Figueroa et al., 2010). However, many mutations affecting sugar signaling are allelic with components of the ABA synthesis or ABA transduction pathways. It has been shown that aba2, aba3, and abi4 mutants are allelic to sugar-insensitive mutants glucose insensitive1 (gin1)/impaired sucrose induction4 (isi4)/sugar insensitive1 (sis1; Laby et al., 2000; Rook et al., 2001), gin5/isi2/sis3 (Arenas-Huertero et al., 2000) and gin6/isi3/sis5/sun6 (Arenas-Huertero et al., 2000), respectively. In addition, ABA accumulation and transcript levels of several ABA biosynthetic genes are significantly increased by glucose (Cheng et al., 2002). These lines of evidence indicate that signaling pathways mediated by ABA and sugars may interact to regulate juvenility and floral signal transduction (Matsoukas et al., 2013).

The downstream effects of the sugar-ABA interaction might be mediated via the circadian clock. Photoperiodic induction requires the circadian clock to measure the duration of the day or night (reviewed in Harmer, 2009; Imaizumi, 2010). The clock modulates the expression of CO, the precursor of FT that accelerates flowering in response to several pathways (reviewed in Turck et al., 2008). It has been shown that glucose has a marked effect on the entrainment and maintenance of robust circadian rhythms (Dalchau et al., 2011; Haydon et al., 2013). In addition, circadian periodicity is also regulated by ABA via an unclear mechanism. This might be through ABI3 (allelic to sis10; Huang et al., 2008) by binding to the clock component TIMING OF CAB EXPRESSION1 (TOC1; also called ABI3 Interacting Protein 1; Kurup et al., 2000; Pokhilko et al., 2013), and/or regulation of CCA1 mRNA transcription levels by ABA (Hanano et al., 2006). Thus, gating of circadian clock sensitivity by the ABA and sugar crosstalk may constitute a regulatory module that coordinates the circadian clock with additional endogenous and environmental signals to regulate juvenility and floral signal transduction.

The sugar-ethylene signaling crosstalk

Ethylene is another example of a phytohormone that regulates juvenility (Beyer and Morgan, 1971) and floral induction (Bleecker et al., 1988; Guzman and Ecker, 1990). Arabidopsis mutants impaired in ethylene signaling [e.g., ethylene insensitive2 (ein2), ein3-1] or perception [e.g., ethylene response1 (etr1-1)], flower late in inductive LDs (Table 1). This late flowering phenotype is significantly enhanced under non-inductive SDs. Mutants, which over-produce ethylene [e.g., ethylene overproducer1 (eto1), eto2-1] flower at the same time or slightly earlier than WT under LDs, but dramatically later in SDs (Bleecker et al., 1988; Guzman and Ecker, 1990; Chen and Bleecker, 1995; Achard et al., 2007). Ample evidence has shown that ethylene can influence plant sensitivity to sugars. Ethylene-insensitive plants are more sensitive to endogenous glucose, whereas application of an ethylene precursor decreases glucose sensitivity (Zhou et al., 1998; Leon and Sheen, 2003). However, this interaction may also function in an antithetical way as several ethylene biosynthetic and signal transduction genes are repressed by glucose (Yanagisawa et al., 2003; Price et al., 2004).

Ethylene sensing and signaling pathways are also tightly interconnected with those for sugar and ABA (reviewed in Gazzarrini and Mccourt, 2001; Leon and Sheen, 2003). Lines of evidence have shown that this crosstalk modulates the vegetative-to-reproductive phase transition. This is suggested by the glucose hypersensitive phenotype displayed by the late flowering mutants ein2 [allelic to enhanced response to aba3 (era3)], ein3 and etr1 (Chang et al., 1993; Zhou et al., 1998; Alonso et al., 1999; Cheng et al., 2002; Yanagisawa et al., 2003). Activation of the ethylene response [either in the presence of exogenous ethylene or by means of the eto1 or constitutive triple response1 (ctr1) mutations] attenuates the glucose effects (Zhou et al., 1998; Gibson et al., 2001). Further support for the sugar-ethylene crosstalk involvement on flowering time is derived by the epistatic analysis of the etr1 gin1 (aba2) and ein2 gin1 (aba2) double mutants in the elucidated role of GIN1 (ABA2) in the ethylene signal transduction cascade. The etr1 gin1 (aba2) and ein2 gin1 (aba2) double mutants flower earlier than etr1 and ein2 single mutants, respectively (Cheng et al., 2002). The early flowering and glucose resistance phenotypes of the double mutants etr1 gin1 (aba2) and ein2 gin1 (aba2) under LDs, may suggest that ethylene affects glucose signaling, partially, through ABA to regulate floral induction (Zhou et al., 1998; Cheng et al., 2002; Ghassemian et al., 2006). Overexpression of ETHYLENE RESPONSE2 (ETR2; Sakai et al., 1998) receptor in Oryza sativa reduced ethylene sensitivity and delayed floral induction (Wuriyanghan et al., 2009). Conversely, disruption of ETR2 by T-DNA or with RNA interference (RNAi) conferred enhanced ethylene sensitivity and early flowering. Moreover, links of the ethylene signaling with starch accumulation responses and activation of sugar transporter genes have also been observed. ETR2 promoted starch accumulation, whereas a monosaccharide transporter gene was suppressed in the ETR2 over-expression lines (Wuriyanghan et al., 2009). Interestingly, when expression of ETR2 was reduced in the OSetr2 T-DNA and RNAi lines, starch failed to accumulate, whereas sugar translocation was enhanced (Wuriyanghan et al., 2009).

Ethylene has dramatic effects on flowering time of mutants involved in activation of the ethylene response under SD conditions (Achard et al., 2007). CONSTITUTIVE TRIPLE RESPONSE1 (CTR1) is a major negative regulator of ethylene signaling that is allelic to GIN4 (Cheng et al., 2002) and SIS1 (Gibson et al., 2001). Loss-of-function ctr1 mutations result in the constitutive activation of the ethylene response pathway, which indicates that the encoded protein acts as a negative regulator of ethylene signaling (Kieber et al., 1993). Under LDs ctr1 has a flowering phenotype similar to WT. In antithesis with the other glucose insensitive genotypes, ctr1 plants flower dramatically later than WT in SDs. This could be due to impaired involvement of GA pathway, which systematize floral initiation in SDs. Interestingly, evidence has been provided that ethylene dramatically prolongs time to flowering in ctr1 under SDs by repressing the up-regulation of LFY and SOC1 transcript levels via a DELLA-dependent mechanism, and decreasing the levels of the endogenous bioactive GAs (Achard et al., 2007).

The sugar-brassinosteroids signaling crosstalk

BRs are steroid hormones known to control various skotomorphogenic (Chory et al., 1991) and photomorphogenic (Li et al., 1996) aspects of development. Genetic and physiological analyses have revealed the critical role of BRs in floral induction (Table 1), establishing a new floral signal transduction pathway. The promotive role of BRs on floral induction is exerted by the late flowering phenotype of BR-deficient mutants brassinosteroid-insensitive1 (brs1; Clouse et al., 1996; Li and Chory, 1997), brassinosteroid-insensitive2 (bin2; Li et al., 2001), deetiolated2 (det2; Chory et al., 1991), constitutive photomorphogenesis and dwarfism (cpd; Szekeres et al., 1996; Domagalska et al., 2007) and brassinosteroid, light and sugar1 (bls1; Laxmi et al., 2004). Conversely, mutations impaired in metabolizing BRs to their inactive forms, phyB-activation-tagged suppressor1 (bas1; Neff et al., 1999) and suppressor of phyB-4 7 (sob7; Turk et al., 2005) flower early (Turk et al., 2005). It has been reported that the response to exogenously applied BRs differs depending on the light quality and quantity (Neff et al., 1999), suggesting a potential interaction with sugars via light-mediated pathways (Goetz et al., 2000; Schluter et al., 2002). In addition, it has been demonstrated that BR responses are related to hormones such as GA (Gallego-Bartolome et al., 2012), ABA (Domagalska et al., 2010), and ethylene (Turk et al., 2005), which participate in sugar signaling. Furthermore, the sugar hypersensitive phenotype of the late flowering bls1 can be repressed by exogenous BRs (Laxmi et al., 2004). Moreover, the late flowering mutant det2, as other constitutively photomorphogenic mutants have been found to have an altered response to applied sugars (reviewed in Chory et al., 1996; Laxmi et al., 2004, and references therein). Collectively, these data indicate interplay between BRs and sugars in regulation of floral signal transduction. The downstream effects of this crosstalk might be mediated through BRASSINAZOLE RESISTANT1 (BZR1) and BZR2, as well as additional interacting TFs. Both BZR1 and BZR2 interact with PIF (Oh et al., 2012) and the GA signaling DELLA proteins (Oh et al., 2012). In addition, the BR-sugar interaction may also be indirectly involved in modulation of juvenility and floral signal transduction by influencing the photoperiodic pathway via the circadian clock, as BR application shortens circadian rhythms (Hanano et al., 2006).

How does the crosstalk between sugars and hormones regulate the floral signal transduction

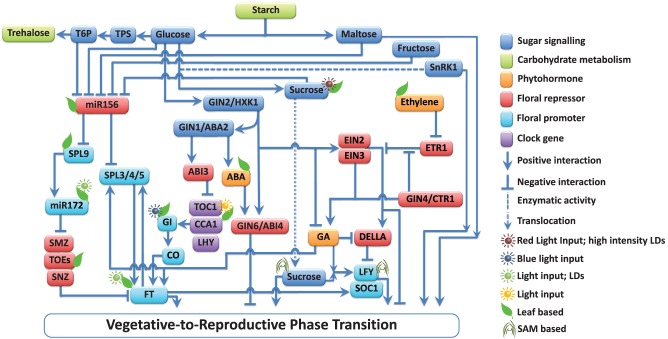

It is proposed that the effects of the sugar-hormone interplay might be mediated by hormones that enable tissues to respond to sugars, and/or hormone and sugar signaling, although essentially separate, could converge and crosstalk through specific regulatory complexes (Figure 1). One regulatory mechanism might be through metabolic enzymes, which also function as active members of transcriptional or posttranscriptional regulatory complexes (Cho et al., 2006). This cross-functionalization could be involved in mechanisms that modulate juvenility and floral signal transduction, by allowing interplay between different sugar and hormone response pathways or receptors.

Figure 1.

Multiple interactions among the components involved in floral signal transduction in response to sugar-hormone interplay. Components of the pathways are grouped into those that promote (↓) and those that repress (⊥) floral signal transduction. Sugars affect the vegetative-to-reproductive phase transition through their function as energy sources, osmotic regulators, signaling molecules, and by their interaction with mineral and phytohormone networks (Ohto et al., 2001; Lloyd and Zakhleniuk, 2004; Matsoukas et al., 2013). Starch metabolism-related events have a key role in developmental phase transitions (Corbesier et al., 1998; Matsoukas et al., 2013). The actions of all pathways ultimately converge to control the expression of a small number of so-called floral pathway integrators (FPIs), which include FLOWERING LOCUS T (FT; Kardailsky et al., 1999; Kobayashi et al., 1999) and SUPPRESSOR OF CONSTANS1 (SOC1; Yoo et al., 2005). These act on floral meristem identity (FMI) genes such as LEAFY (LFY; Lee et al., 2008) and APETALA1 (AP1; Wigge et al., 2005; Yamaguchi et al., 2005), which result in floral induction. The main components and interactions are depicted in the diagram, but additional elements have been omitted for clarity. Comprehensive reviews are available (Smeekens et al., 2010; Depuydt and Hardtke, 2011; Huijser and Schmid, 2011; Andres and Coupland, 2012; Matsoukas et al., 2012) and should be referred to for additional pieces of information.

The HXK1-miR156 regulatory module

Sugar signals can be generated either by carbohydrate concentration and relative ratios to other metabolites, such as hormones (Arenas-Huertero et al., 2000) and carbon-nitrogen ratio (Corbesier et al., 2002; Rolland et al., 2006), or by flux through sugar-specific transporters (Lalonde et al., 1999) and/or sensors (Moore et al., 2003). Sugar sensors perceive the presence of different sugars and initiate downstream signaling events. Glucose (Moore et al., 2003), fructose (Cho and Yoo, 2011; Li et al., 2011), sucrose (Seo et al., 2011), Tre6P (Van Dijken et al., 2004), and maltose (Niittyla et al., 2004; Stettler et al., 2009) function as cellular signaling molecules in specific regulatory pathways, which modulate juvenility and floral signal transduction. Of these signaling molecules, glucose has been studied the most comprehensively in plants.

Glucose-mediated floral signal transduction is largely dependent on HXK, HXK-independent, and SnRK1 signaling pathways. One possibility is that HXK1 controls juvenility and floral signal transduction by regulating the expression of miR156 (Yang et al., 2013). In this scenario, HXK1 that is largely dependent on ABA biosynthesis and signaling components (Zhou et al., 1998; Arenas-Huertero et al., 2000) promotes miR156 expression under low sugar levels. Above a threshold concentration, the circadian fluctuations of glucose, one of the final outputs of starch degradation (Stitt and Zeeman, 2012) that is regulated by starch and Tre6P (Martins et al., 2013) promotes GA biosynthesis (Cheng et al., 2002; Yu et al., 2012; Paparelli et al., 2013) and blocks HXK1 activity, resulting in downregulation of miR156 expression (Yang et al., 2013; Yu et al., 2013). Interestingly, defoliation experiments (Yang et al., 2011, 2013; Yu et al., 2013) show that removing the two oldest leaves results in increased miR156 levels at the SAM and a prolonged juvenile phase length. The fact that glucose, fructose, sucrose and maltose, partially, reverse this effect (Wang et al., 2013; Yu et al., 2013), indicates that photosynthetically derived sugars are potential components of the signal transduction pathway that repress miR156 expression in leaf primordia.

It seems highly probable that the differential regulation of SnRK1 by ABA and GAs (Bradford et al., 2003), and the antagonism between ABA and GA, which function in an opposite manner, to activate specific cis-acting regulatory elements present in ABA- and GA-responsive promoters respectively (reviewed in Yamaguchi-Shinozaki and Shinozaki, 2005), may also be involved in this regulatory module (Achard et al., 2006; Yu et al., 2012; Wang et al., 2013).

The Tre6P-miR156 regulatory module

Tre6P is a metabolite of emerging significance in plant developmental biology, with hormone-like metabolic activities (reviewed in Smeekens et al., 2010; Ponnu et al., 2011). It has been proposed that Tre6P signals the availability of sucrose (Lunn et al., 2006), and then through the SnRK1 regulatory system orchestrates changes in gene expression that enable sucrose to regulate juvenility and floral signal transduction. In Arabidopsis, Tre6P is synthesized from glucose-6-phospate by TREHALOSE PHOSPHATE SYNTHASE 1 (TPS1; Van Dijken et al., 2004). Non-embryo-lethal weak alleles of tps1 exhibit late flowering (Van Dijken et al., 2004) and ABA hypersensitive phenotypes (Gomez et al., 2010). Interestingly, the Tre6P pathway controls the expression of SPL3, SPL4, and SPL5 at the SAM, partially via miR156, and partly independently of the miR156-dependent pathway via FT (Wahl et al., 2013). Several pieces of evidence suggest that Tre6P inhibits SnRK1 when sucrose is above a threshold concentration (Polge and Thomas, 2007; Zhang et al., 2009). When the sucrose content decreases, with Tre6P decreasing as well, SnRK1 is released from repression, which leads to the induction of genes involved in photosynthesis-related events, so that more carbon is made available (Delatte et al., 2011). It has been shown that the Tre6P-SnRK1 module acts through a mechanism involving ABA (Gomez et al., 2010) and sugar metabolism (Van Dijken et al., 2004) to regulate several developmental events. The key link between sugars and ABA perception is exemplified by the ABI genes (Eveland and Jackson, 2012; Wang et al., 2013). Interestingly, ABI4 encodes an AP2 domain TF that is required for normal sugar responses during the early stages of development (Arenas-Huertero et al., 2000; Laby et al., 2000; Rook et al., 2001; Niu et al., 2002). Taken together, these data could provide another mechanistic link, at the molecular level, on how the ABA-sugar interplay might be involved in regulation of juvenility and floral signal transduction.

Perspectives

Sugars serve diverse functions in plants ranging from energy sources, osmotic regulators, storage molecules, and structural components to intermediates for the synthesis of other organic molecules. Sugars also act as signaling molecules and by their interaction with mineral and hormonal networks affect several aspects of growth and development.

There has been a long-standing interest in the role played by sugars and hormones in regulation of the juvenile-to-adult and vegetative-to-reproductive phase transitions. It has been proposed that the effects of sugar-hormone interactions might be mediated by key hormones that enable tissues to respond to sugars, and/or hormone and sugar signaling could converge and crosstalk through specific regulatory complexes and/or metabolic enzymes. However, how sugar and hormone signals are integrated into genetic pathways that regulate the juvenile-to-adult and vegetative-to-reproductive phase transitions is still incompletely understood. Recent studies have shown that metabolic enzymes, ABA, GA and Tre6P may integrate into the miR156/SPL-signaling pathway. However, despite this progress, mechanistic questions remain. Future challenges include the further clarification of the antagonistic and agonistic interactions between the sugar- and hormone-derived signals in a spatio-temporal manner at the molecular level, and their link to other known important transcriptional regulatory networks.

Conflict of interest statement

The author declares that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

Acknowledgments

The author would like to thank Professor Brian Thomas (University of Warwick, UK) and Dr Andrea Massiah (University of Warwick, UK) for valuable discussions, and the three independent reviewers for their comments on the manuscript. Ianis G. Matsoukas is supported by the Hellenic State Scholarships Foundation and University of Bolton (UK).

References

- Abe M., Kobayashi Y., Yamamoto S., Daimon Y., Yamaguchi A., Ikeda Y., et al. (2005). FD, a bZIP protein mediating signals from the floral pathway integrator FT at the shoot apex. Science 309, 1052–1056 10.1126/science.1115983 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Achard P., Baghour M., Chapple A., Hedden P., Van Der Straeten D., Genschik P., et al. (2007). The plant stress hormone ethylene controls floral transition via DELLA-dependent regulation ot floral meristem-identity genes. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 104, 6484–6489 10.1073/pnas.0610717104 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Achard P., Cheng H., De Grauwe L., Decat J., Schoutteten H., Moritz T., et al. (2006). Integration of plant responses to environmentally activated phytohormonal signals. Science 311, 91–94 10.1126/science.1118642 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ahmad M., Cashmore A. R. (1993). HY4 gene of A. thaliana encodes a protein with characteristics of a blue-light photoreceptor. Nature 366, 162–166 10.1038/366162a0 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Alonso J. M., Hirayama T., Roman G., Nourizadeh S., Ecker J. R. (1999). EIN2, a bifunctional transducer of ethylene and stress responses in Arabidopsis. Science 284, 2148–2152 10.1126/science.284.5423.2148 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Amasino R. (2010). Seasonal and developmental timing of flowering. Plant J. 61, 1001–1013 10.1111/j.1365-313X.2010.04148.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Andres F., Coupland G. (2012). The genetic basis of flowering responses to seasonal cues. Nat. Rev. Genet. 13, 627–639 10.1038/nrg3291 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Arenas-Huertero F., Arroyo A., Zhou L., Sheen J., Leon P. (2000). Analysis of Arabidopsis glucose insensitive mutants, gin5 and gin6, reveals a central role of the plant hormone ABA in the regulation of plant vegetative development by sugar. Genes Dev. 14, 2085–2096 10.1101/gad.14.16.2085 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Baena-Gonzalez E., Rolland F., Thevelein J. M., Sheen J. (2007). A central integrator of transcription networks in plant stress and energy signalling. Nature 448, 938–942 10.1038/nature06069 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Beyer E. M., Morgan P. W. (1971). Abscission: the role of ethylene modification of auxin transport. Plant Physiol. 48, 208–212 10.1104/pp.48.2.208 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bittner F., Oreb M., Mendel R. R. (2001). ABA3 is a molybdenum cofactor sulfurase required for activation of aldehyde oxidase and xanthine dehydrogenase in Arabidopsis thaliana. J. Biol. Chem. 276, 40381–40384 10.1074/jbc.C100472200 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Blazquez M. A., Green R., Nilsson O., Sussman M. R., Weigel D. (1998). Gibberellins promote flowering of Arabidopsis by activating the LEAFY promoter. Plant Cell 10, 791–800 10.1105/tpc.10.5.791 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bleecker A. B., Estelle M. A., Somerville C., Kende H. (1988). Insensitivity to ethylene conferred by a dominant mutation in Arabidopsis thaliana. Science 241, 1086–1089 10.1126/science.241.4869.1086 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bradford K. J., Downie A. B., Gee O. H., Alvarado V., Yang H., Dahal P. (2003). Abscisic acid and gibberellin differentially regulate expression of genes of the SNF1-related kinase complex in tomato seeds. Plant Physiol. 132, 1560–1576 10.1104/pp.102.019141 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chae H. S., Faure F., Kieber J. J. (2003). The eto1, eto2, and eto3 mutations and cytokinin treatment increase ethylene biosynthesis in Arabidopsis by increasing the stability of ACS protein. Plant Cell 15, 545–559 10.1105/tpc.006882 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chang C., Kwok S. F., Bleecker A. B., Meyerowitz E. M. (1993). Arabidopsis ethylene-response gene ETR1: similarity of product to two-component regulators. Science 262, 539–544 10.1126/science.8211181 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chen Q. G., Bleecker A. B. (1995). Analysis of ethylene signal-transduction kinetics associated with seedling-growth response and chitinase induction in wild-type and mutant arabidopsis. Plant Physiol. 108, 597–607 10.1104/pp.108.2.597 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cheng H., Qin L., Lee S., Fu X., Richards D. E., Cao D., et al. (2004). Gibberellin regulates Arabidopsis floral development via suppression of DELLA protein function. Development 131, 1055–1064 10.1242/dev.00992 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cheng W. H., Endo A., Zhou L., Penney J., Chen H. C., Arroyo A., et al. (2002). A unique short-chain dehydrogenase/reductase in Arabidopsis glucose signaling and abscisic acid biosynthesis and functions. Plant Cell 14, 2723–2743 10.1105/tpc.006494 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cho Y. H., Yoo S. D. (2011). Signaling role of fructose mediated by FINS1/FBP in Arabidopsis thaliana. PLoS Genet. 7:e1001263 10.1371/journal.pgen.1001263 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cho Y. H., Yoo S. D., Sheen J. (2006). Regulatory functions of nuclear hexokinase1 complex in glucose signaling. Cell 127, 579–589 10.1016/j.cell.2006.09.028 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Choe S., Dilkes B. P., Fujioka S., Takatsuto S., Sakurai A., Feldmann K. A. (1998). The DWF4 gene of Arabidopsis encodes a cytochrome P450 that mediates multiple 22alpha-hydroxylation steps in brassinosteroid biosynthesis. Plant Cell 10, 231–243 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chory J., Catterjee M., Cook R. K., Elich T., Fankhauser C., Li J., et al. (1996). From seed germination to flowering, light controls plant development via the pigment phytochrome. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 93, 12066–12071 10.1073/pnas.93.22.12066 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chory J., Nagpal P., Peto C. A. (1991). Phenotypic and genetic analysis of det2, a new mutant that affects light-regulated seedling development in Arabidopsis. Plant Cell 3, 445–459 10.1105/tpc.3.5.445 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Clack T., Mathews S., Sharrock R. A. (1994). The phytochrome apoprotein family in Arabidopsis is encoded by five genes: the sequences and expression of PHYD and PHYE. Plant Mol. Biol. 25, 413–427 10.1007/BF00043870 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Clouse S. D., Langford M., Mcmorris T. C. (1996). A brassinosteroid-insensitive mutant in Arabidopsis thaliana exhibits multiple defects in growth and development. Plant Physiol. 111, 671–678 10.1104/pp.111.3.671 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Corbesier L., Bernier G., Perilleux C. (2002). C: N ratio increases in the phloem sap during floral transition of the long-day plants Sinapis alba and Arabidopsis thaliana. Plant Cell Physiol. 43, 684–688 10.1093/pcp/pcf071 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Corbesier L., Lejeune P., Bernier G. (1998). The role of carbohydrates in the induction of flowering in Arabidopsis thaliana: comparison between the wild type and a starchless mutant. Planta 206, 131–137 10.1007/s004250050383 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Corbesier L., Vincent C., Jang S. H., Fornara F., Fan Q. Z., Searle I., et al. (2007). FT protein movement contributes to long-distance signaling in floral induction of Arabidopsis. Science 316, 1030–1033 10.1126/science.1141752 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- D'aloia M., Bonhomme D., Bouche F., Tamseddak K., Ormenese S., Torti S., et al. (2011). Cytokinin promotes flowering of Arabidopsis via transcriptional activation of the FT paralogue TSF. Plant J. 65, 972–979 10.1111/j.1365-313X.2011.04482.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dalchau N., Baek S. J., Briggs H. M., Robertson F. C., Dodd A. N., Gardner M. J., et al. (2011). The circadian oscillator gene GIGANTEA mediates a long-term response of the Arabidopsis thaliana circadian clock to sucrose. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 108, 5104–5109 10.1073/pnas.1015452108 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- De Lucas M., Daviere J. M., Rodriguez-Falcon M., Pontin M., Iglesias-Pedraz J. M., Lorrain S., et al. (2008). A molecular framework for light and gibberellin control of cell elongation. Nature 451, 480–484 10.1038/nature06520 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Delatte T. L., Sedijani P., Kondou Y., Matsui M., De Jong G. J., Somsen G. W., et al. (2011). Growth arrest by trehalose-6-phosphate: an astonishing case of primary metabolite control over growth by way of the SnRK1 signaling pathway. Plant Physiol. 157, 160–174 10.1104/pp.111.180422 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Depuydt S., Hardtke C. S. (2011). Hormone signalling crosstalk in plant growth regulation. Curr. Biol. 21, R365–R373 10.1016/j.cub.2011.03.013 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Domagalska M. A., Sarnowska E., Nagy F., Davis S. J. (2010). Genetic analyses of interactions among gibberellin, abscisic acid, and brassinosteroids in the control of flowering time in Arabidopsis thaliana. PLoS ONE 5:e14012 10.1371/journal.pone.0014012 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Domagalska M. A., Schomburg F. M., Amasino R. M., Vierstra R. D., Nagy F., Davis S. J. (2007). Attenuation of brassinosteroid signaling enhances FLC expression and delays flowering. Development 134, 2841–2850 10.1242/dev.02866 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Eimert K., Wang S. M., Lue W. I., Chen J. (1995). Monogenic recessive mutations causing both late floral initiation and excess starch accumulation in Arabidopsis. Plant Cell 7, 1703–1712 10.1105/tpc.7.10.1703 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Eriksson S., Bohlenius H., Moritz T., Nilsson O. (2006). GA4 is the active gibberellin in the regulation of LEAFY transcription and Arabidopsis floral initiation. Plant Cell 18, 2172–2181 10.1105/tpc.106.042317 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Eveland A. L., Jackson D. P. (2012). Sugars, signalling, and plant development. J. Exp. Bot. 63, 3367–3377 10.1093/jxb/err379 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Feng S., Martinez C., Gusmaroli G., Wang Y., Zhou J., Wang F., et al. (2008). Coordinated regulation of Arabidopsis thaliana development by light and gibberellins. Nature 451, 475–479 10.1038/nature06448 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Finkelstein R. R., Wang M. L., Lynch T. J., Rao S., Goodman H. M. (1998). The Arabidopsis abscisic acid response locus ABI4 encodes an APETALA 2 domain protein. Plant Cell 10, 1043–1054 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fowler S., Lee K., Onouchi H., Samach A., Richardson K., Morris B., et al. (1999). GIGANTEA: a circadian clock-controlled gene that regulates photoperiodic flowering in Arabidopsis and encodes a protein with several possible membrane-spanning domains. EMBO J. 18, 4679–4688 10.1093/emboj/18.17.4679 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fujita H., Syono K. (1996). Genetic analysis of the effects of polar auxin transport inhibitors on root growth in Arabidopsis thaliana. Plant Cell Physiol. 37, 1094–1101 10.1093/oxfordjournals.pcp.a029059 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gallego-Bartolome J., Minguet E. G., Grau-Enguix F., Abbas M., Locascio A., Thomas S. G., et al. (2012). Molecular mechanism for the interaction between gibberellin and brassinosteroid signaling pathways in Arabidopsis. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 109, 13446–13451 10.1073/pnas.1119992109 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gazzarrini S., Mccourt P. (2001). Genetic interactions between ABA, ethylene and sugar signaling pathways. Curr. Opin. Plant Biol. 4, 387–391 10.1016/S1369-5266(00)00190-4 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ghassemian M., Lutes J., Tepperman J. M., Chang H. S., Zhu T., Wang X., et al. (2006). Integrative analysis of transcript and metabolite profiling data sets to evaluate the regulation of biochemical pathways during photomorphogenesis. Arch. Biochem. Biophys. 448, 45–59 10.1016/j.abb.2005.11.020 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gibson S. I., Laby R. J., Kim D. (2001). The sugar-insensitive1 (sis1) mutant of Arabidopsis is allelic to ctr1. Biochem. Biophys. Res. Commun. 280, 196–203 10.1006/bbrc.2000.4062 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Giraudat J., Hauge B. M., Valon C., Smalle J., Parcy F., Goodman H. M. (1992). Isolation of the Arabidopsis ABI3 gene by positional cloning. Plant Cell 4, 1251–1261 10.1105/tpc.4.10.1251 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Goetz M., Godt D. E., Roitsch T. (2000). Tissue-specific induction of the mRNA for an extracellular invertase isoenzyme of tomato by brassinosteroids suggests a role for steroid hormones in assimilate partitioning. Plant J. 22, 515–522 10.1046/j.1365-313x.2000.00766.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gomez L. D., Gilday A., Feil R., Lunn J. E., Graham I. A. (2010). AtTPS1-mediated trehalose 6-phosphate synthesis is essential for embryogenic and vegetative growth and responsiveness to ABA in germinating seeds and stomatal guard cells. Plant J. 64, 1–13 10.1111/j.1365-313X.2010.04312.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Greenboim-Wainberg Y., Maymon I., Borochov R., Alvarez J., Olszewski N., Ori N., et al. (2005). Cross talk between gibberellin and cytokinin: the Arabidopsis GA response inhibitor SPINDLY plays a positive role in cytokinin signaling. Plant Cell 17, 92–102 10.1105/tpc.104.028472 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Guo H., Yang H., Mockler T. C., Lin C. (1998). Regulation of flowering time by Arabidopsis photoreceptors. Science 279, 1360–1363 10.1126/science.279.5355.1360 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Guzman P., Ecker J. R. (1990). Exploiting the triple response of Arabidopsis to identify ethylene-related mutants. Plant Cell 2, 513–523 10.1105/tpc.2.6.513 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hanano S., Domagalska M. A., Nagy F., Davis S. J. (2006). Multiple phytohormones influence distinct parameters of the plant circadian clock. Genes Cells 11, 1381–1392 10.1111/j.1365-2443.2006.01026.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Harberd N. P., Belfield E., Yasumura Y. (2009). The angiosperm gibberellin-GID1-DELLA growth regulatory mechanism: how an “inhibitor of an inhibitor” enables flexible response to fluctuating environments. Plant Cell 21, 1328–1339 10.1105/tpc.109.066969 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Harmer S. L. (2009). The circadian system in higher plants. Annu. Rev. Plant Biol. 60, 357–377 10.1146/annurev.arplant.043008.092054 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Haydon M. J., Mielczarek O., Robertson F. C., Hubbard K. E., Webb A. A. (2013). Photosynthetic entrainment of the Arabidopsis thaliana circadian clock. Nature 502, 689–692 10.1038/nature12603 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hedden P., Phillips A. L. (2000). Manipulation of hormone biosynthetic genes in transgenic plants. Curr. Opin. Biol. 11, 130–137 10.1016/S0958-1669(00)00071-9 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Huang Y., Li C. Y., Biddle K. D., Gibson S. I. (2008). Identification, cloning and characterization of sis7 and sis10 sugar-insensitive mutants of Arabidopsis. BMC Plant Biol. 8:104 10.1186/1471-2229-8-104 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Huijser P., Schmid M. (2011). The control of developmental phase transitions in plants. Development 138, 4117–4129 10.1242/dev.063511 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Imaizumi T. (2010). Arabidopsis circadian clock and photoperiodism: time to think about location. Curr. Opin. Plant Biol. 13, 83–89 10.1016/j.pbi.2009.09.007 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jacobsen S. E., Olszewski N. E. (1993). Mutations at the SPINDLY locus of Arabidopsis alter gibberellin signal transduction. Plant Cell 5, 887–896 10.1105/tpc.5.8.887 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jeong J. H., Song H. R., Ko J. H., Jeong Y. M., Kwon Y. E., Seol J. H., et al. (2009). Repression of FLOWERING LOCUS T chromatin by functionally redundant histone H3 lysine 4 demethylases in Arabidopsis. PLoS ONE 4:e8033 10.1371/journal.pone.0008033 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jin J. B., Jin Y. H., Lee J., Miura K., Yoo C. Y., Kim W. Y., et al. (2008). The SUMO E3 ligase, AtSIZ1, regulates flowering by controlling a salicylic acid-mediated floral promotion pathway and through affects on FLC chromatin structure. Plant J. 53, 530–540 10.1111/j.1365-313X.2007.03359.x [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jung J. H., Ju Y., Seo P. J., Lee J. H., Park C. M. (2012). The SOC1-SPL module integrates photoperiod and gibberellic acid signals to control flowering time in Arabidopsis. Plant J. 69, 577–588 10.1111/j.1365-313X.2011.04813.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jung J. H., Seo P. J., Kang S. K., Park C. M. (2011). miR172 signals are incorporated into the miR156 signaling pathway at the SPL3/4/5 genes in Arabidopsis developmental transitions. Plant Mol. Biol. 76, 35–45 10.1007/s11103-011-9759-z [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jung J. H., Seo Y. H., Seo P. J., Reyes J. L., Yun J., Chua N. H., et al. (2007). The GIGANTEA-regulated microRNA172 mediates photoperiodic flowering independent of CONSTANS in Arabidopsis. Plant Cell 19, 2736–2748 10.1105/tpc.107.054528 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kardailsky I., Shukla V. K., Ahn J. H., Dagenais N., Christensen S. K., Nguyen J. T., et al. (1999). Activation tagging of the floral inducer FT. Science 286, 1962–1965 10.1126/science.286.5446.1962 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kieber J. J., Rothenberg M., Roman G., Feldmann K. A., Ecker J. R. (1993). Ctr1, a negative regulator of the ethylene response pathway in Arabidopsis, encodes a member of the Raf family of protein-kinases. Cell 72, 427–441 10.1016/0092-8674(93)90119-B [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kim J. J., Lee J. H., Kim W., Jung H. S., Huijser P., Ahn J. H. (2012). The microRNA156-SQUAMOSA PROMOTER BINDING PROTEIN-LIKE3 module regulates ambient temperature-responsive flowering via FLOWERING LOCUS T in Arabidopsis. Plant Physiol. 159, 461–478 10.1104/pp.111.192369 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kleine T., Lockhart P., Batschauer A. (2003). An Arabidopsis protein closely related to Synechocystis cryptochrome is targeted to organelles. Plant J. 35, 93–103 10.1046/j.1365-313X.2003.01787.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kobayashi Y., Kaya H., Goto K., Iwabuchi M., Araki T. (1999). A pair of related genes with antagonistic roles in mediating flowering signals. Science 286, 1960–1962 10.1126/science.286.5446.1960 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Koornneef M., Van Der Veen J. H. (1980). Induction and analysis of gibberellin sensitive mutants in Arabidopsis thaliana (L.) heynh. Theor. Appl. Genet. 58, 257–263 10.1007/BF00265176 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kreps J. A., Simon A. E. (1997). Environmental and genetic effects on circadian clock-regulated gene expression in Arabidopsis. Plant Cell 9, 297–304 10.1105/tpc.9.3.297 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kurup S., Jones H. D., Holdsworth M. J. (2000). Interactions of the developmental regulator ABI3 with proteins identified from developing Arabidopsis seeds. Plant J. 21, 143–155 10.1046/j.1365-313x.2000.00663.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Laby R. J., Kincaid M. S., Kim D. G., Gibson S. I. (2000). The Arabidopsis sugar-insensitive mutants sis4 and sis5 are defective in abscisic acid synthesis and response. Plant J. 23, 587–596 10.1046/j.1365-313x.2000.00833.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lalonde S., Boles E., Hellmann H., Barker L., Patrick J. W., Frommer W. B., et al. (1999). The dual function of sugar carriers. Transport and sugar sensing. Plant Cell 11, 707–726 10.1105/tpc.11.4.707 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Laxmi A., Paul L. K., Peters J. L., Khurana J. P. (2004). Arabidopsis constitutive photomorphogenic mutant, bls1, displays altered brassinosteroid response and sugar sensitivity. Plant Mol. Biol. 56, 185–201 10.1007/s11103-004-2799-x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lee J., Oh M., Park H., Lee I. (2008). SOC1 translocated to the nucleus by interaction with AGL24 directly regulates LEAFY. Plant J. 55, 832–843 10.1111/j.1365-313X.2008.03552.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Leon P., Sheen J. (2003). Sugar and hormone connections. Trends Plant Sci. 8, 110–116 10.1016/S1360-1385(03)00011-6 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Leon-Kloosterziel K. M., Gil M. A., Ruijs G. J., Jacobsen S. E., Olszewski N. E., Schwartz S. H., et al. (1996). Isolation and characterization of abscisic acid-deficient Arabidopsis mutants at two new loci. Plant J. 10, 655–661 10.1046/j.1365-313X.1996.10040655.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Li J., Nagpal P., Vitart V., Mcmorris T. C., Chory J. (1996). A role for brassinosteroids in light-dependent development of Arabidopsis. Science 272, 398–401 10.1126/science.272.5260.398 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Li J. M., Chory J. (1997). A putative leucine-rich repeat receptor kinase involved in brassinosteroid signal transduction. Cell 90, 929–938 10.1016/S0092-8674(00)80357-8 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Li J. M., Nam K. H., Vafeados D., Chory J. (2001). BIN2, a new brassinosteroid-insensitive locus in Arabidopsis. Plant Physiol. 127, 14–22 10.1104/pp.127.1.14 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Li P., Wind J. J., Shi X., Zhang H., Hanson J., Smeekens S. C., et al. (2011). Fructose sensitivity is suppressed in Arabidopsis by the transcription factor ANAC089 lacking the membrane-bound domain. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 108, 3436–3441 10.1073/pnas.1018665108 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Liu C., Chen H., Er H. L., Soo H. M., Kumar P. P., Han J. H., et al. (2008). Direct interaction of AGL24 and SOC1 integrates flowering signals in Arabidopsis. Development 135, 1481–1491 10.1242/dev.020255 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lloyd J. C., Zakhleniuk O. V. (2004). Responses of primary and secondary metabolism to sugar accumulation revealed by microarray expression analysis of the Arabidopsis mutant, pho3. J. Exp. Bot. 55, 1221–1230 10.1093/jxb/erh143 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lunn J. E., Feil R., Hendriks J. H., Gibon Y., Morcuende R., Osuna D., et al. (2006). Sugar-induced increases in trehalose 6-phosphate are correlated with redox activation of ADPglucose pyrophosphorylase and higher rates of starch synthesis in Arabidopsis thaliana. Biochem. J. 397, 139–148 10.1042/BJ20060083 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Martinez-Zapater J. M., Coupland G., Dean C., Koornneef M. (1994). The transition to flowering in Arabidopsis, in Arabidopsis, eds Meyerowitz E. M., Somerville C. R. (Cold Spring Harbor, NY: Cold Spring Harbor Laboratory Press; ), 403–433 [Google Scholar]

- Martins M. C., Hejazi M., Fettke J., Steup M., Feil R., Krause U., et al. (2013). Feedback inhibition of starch degradation in Arabidopsis leaves mediated by trehalose 6-phosphate. Plant Physiol. 163, 1142–1163 10.1104/pp.113.226787 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mathieu J., Yant L. J., Murdter F., Kuttner F., Schmid M. (2009). Repression of flowering by the miR172 target SMZ. PLoS Biol. 7:e1000148 10.1371/journal.pbio.1000148 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Matsoukas I. G. (2014). Attainment of reproductive competence, phase transition, and quantification of juvenility in mutant genetic screens. Front. Plant Sci. 5:32 10.3389/fpls.2014.00032 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Matsoukas I. G., Massiah A. J., Thomas B. (2012). Florigenic and antiflorigenic signalling in plants. Plant Cell Physiol. 53, 1827–1842 10.1093/pcp/pcs130 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Matsoukas I. G., Massiah A. J., Thomas B. (2013). Starch metabolism and antiflorigenic signals modulate the juvenile-to-adult phase transition in Arabidopsis. Plant Cell Environ. 36, 1802–1811 10.1111/pce.12088 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Melzer S., Lens F., Gennen J., Vanneste S., Rohde A., Beeckman T. (2008). Flowering-time genes modulate meristem determinacy and growth form in Arabidopsis thaliana. Nat. Genet. 40, 1489–1492 10.1038/ng.253 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Michaels S. D. (2009). Flowering time regulation produces much fruit. Curr. Opin. Plant Biol. 12, 75–80 10.1016/j.pbi.2008.09.005 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mizoguchi T., Wheatley K., Hanzawa Y., Wright L., Mizoguchi M., Song H. R., et al. (2002). LHY and CCA1 are partially redundant genes required to maintain circadian rhythms in Arabidopsis. Dev. Cell 2, 629–641 10.1016/S1534-5807(02)00170-3 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Moore B., Zhou L., Rolland F., Hall Q., Cheng W. H., Liu Y. X., et al. (2003). Role of the Arabidopsis glucose sensor HXK1 in nutrient, light, and hormonal signaling. Science 300, 332–336 10.1126/science.1080585 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Neff M. M., Nguyen S. M., Malancharuvil E. J., Fujioka S., Noguchi T., Seto H., et al. (1999). BAS1: a gene regulating brassinosteroid levels and light responsiveness in Arabidopsis. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 96, 15316–15323 10.1073/pnas.96.26.15316 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Niittyla T., Messerli G., Trevisan M., Chen J., Smith A. M., Zeeman S. C. (2004). A previously unknown maltose transporter essential for starch degradation in leaves. Science 303, 87–89 10.1126/science.1091811 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Niu X., Helentjaris T., Bate N. J. (2002). Maize ABI4 binds coupling element1 in abscisic acid and sugar response genes. Plant Cell 14, 2565–2575 10.1105/tpc.003400 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Noguchi T., Fujioka S., Takatsuto S., Sakurai A., Yoshida S., Li J., et al. (1999). Arabidopsis det2 is defective in the conversion of (24R)-24-methylcholest-4-En-3-one to (24R)-24-methyl-5alpha-cholestan-3-one in brassinosteroid biosynthesis. Plant Physiol. 120, 833–840 10.1104/pp.120.3.833 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nozue K., Harmer S. L., Maloof J. N. (2011). Genomic analysis of circadian clock-, light-, and growth-correlated genes reveals PHYTOCHROME-INTERACTING FACTOR5 as a modulator of auxin signaling in Arabidopsis. Plant Physiol. 156, 357–372 10.1104/pp.111.172684 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Oh E., Zhu J. Y., Wang Z. Y. (2012). Interaction between BZR1 and PIF4 integrates brassinosteroid and environmental responses. Nat. Cell Biol. 14, 802–809 10.1038/ncb2545 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ohto M., Onai K., Furukawa Y., Aoki E., Araki T., Nakamura K. (2001). Effects of sugar on vegetative development and floral transition in arabidopsis. Plant Physiol. 127, 252–261 10.1104/pp.127.1.252 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Paparelli E., Parlanti S., Gonzali S., Novi G., Mariotti L., Ceccarelli N., et al. (2013). Nighttime sugar starvation orchestrates gibberellin biosynthesis and plant growth in Arabidopsis. Plant Cell 25, 3760–3769 10.1105/tpc.113.115519 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Penfield S., Hall A. (2009). A role for multiple circadian clock genes in the response to signals that break seed dormancy in Arabidopsis. Plant Cell 21, 1722–1732 10.1105/tpc.108.064022 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Peng J., Carol P., Richards D. E., King K. E., Cowling R. J., Murphy G. P., et al. (1997). The Arabidopsis GAI gene defines a signaling pathway that negatively regulates gibberellin responses. Genes Dev. 11, 3194–3205 10.1101/gad.11.23.3194 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Peng J., Harberd N. P. (1993). Derivative alleles of the Arabidopsis gibberellin-insensitive (gai) mutation confer a wild-type phenotype. Plant Cell 5, 351–360 10.1105/tpc.5.3.351 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Poethig R. S. (1990). Phase change and the regulation of shoot morphogenesis in plants. Science 250, 923–930 10.1126/science.250.4983.923 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Poethig R. S. (2013). Vegetative phase change and shoot maturation in plants. Curr. Top. Dev. Biol. 105, 125–152 10.1016/B978-0-12-396968-2.00005-1 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pokhilko A., Mas P., Millar A. J. (2013). Modelling the widespread effects of TOC1 signalling on the plant circadian clock and its outputs. BMC Syst. Biol. 7:23 10.1186/1752-0509-7-23 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Polge C., Thomas M. (2007). SNF1/AMPK/SnRK1 kinases, global regulators at the heart of energy control? Trends Plant Sci. 12, 20–28 10.1016/j.tplants.2006.11.005 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ponnu J., Wahl V., Schmid M. (2011). Trehalose-6-phosphate: connecting plant metabolism and development. Front. Plant Sci. 2:70 10.3389/fpls.2011.00070 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Porri A., Torti S., Romera-Branchat M., Coupland G. (2012). Spatially distinct regulatory roles for gibberellins in the promotion of flowering of Arabidopsis under long photoperiods. Development 139, 2198–2209 10.1242/dev.077164 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Price J., Laxmi A., St Martin S. K., Jang J. C. (2004). Global transcription profiling reveals multiple sugar signal transduction mechanisms in Arabidopsis. Plant Cell 16, 2128–2150 10.1105/tpc.104.022616 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Quiroz-Figueroa F., Rodriguez-Acosta A., Salazar-Blas A., Hernandez-Dominguez E., Campos M. E., Kitahata N., et al. (2010). Accumulation of high levels of ABA regulates the pleiotropic response of the nhr1 Arabidopsis mutant. J. Plant Biol. 53, 32–44 10.1007/s12374-009-9083-1 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Rolland F., Baena-Gonzalez E., Sheen J. (2006). Sugar sensing and signaling in plants: conserved and novel mechanisms. Annu. Rev. Plant Biol. 57, 675–709 10.1146/annurev.arplant.57.032905.105441 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Roman G., Lubarsky B., Kieber J. J., Rothenberg M., Ecker J. R. (1995). Genetic analysis of ethylene signal transduction in Arabidopsis thaliana: five novel mutant loci integrated into a stress response pathway. Genetics 139, 1393–1409 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rook F., Corke F., Card R., Munz G., Smith C., Bevan M. W. (2001). Impaired sucrose-induction mutants reveal the modulation of sugar-induced starch biosynthetic gene expression by abscisic acid signalling. Plant J. 26, 421–433 10.1046/j.1365-313X.2001.2641043.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sakai H., Hua J., Chen Q. G., Chang C., Medrano L. J., Bleecker A. B., et al. (1998). ETR2 is an ETR1-like gene involved in ethylene signaling in Arabidopsis. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 95, 5812–5817 10.1073/pnas.95.10.5812 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schaffer R., Ramsay N., Samach A., Corden S., Putterill J., Carre I. A., et al. (1998). The late elongated hypocotyl mutation of Arabidopsis disrupts circadian rhythms and the photoperiodic control of flowering. Cell 93, 1219–1229 10.1016/S0092-8674(00)81465-8 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schluter U., Kopke D., Altmann T., Mussig C. (2002). Analysis of carbohydrate metabolism of CPD antisense plants and the brassinosteroid-deficient cbb1 mutant. Plant Cell Environ. 25, 783–791 10.1046/j.1365-3040.2002.00860.x [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Schmitz R. J., Sung S., Amasino R. M. (2008). Histone arginine methylation is required for vernalization-induced epigenetic silencing of FLC in winter-annual Arabidopsis thaliana. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 105, 411–416 10.1073/pnas.0710423104 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schwab R., Palatnik J. F., Riester M., Schommer C., Schmid M., Weigel D. (2005). Specific effects of microRNAs on the plant transcriptome. Dev. Cell. 8, 517–527 10.1016/j.devcel.2005.01.018 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schwarz S., Grande A. V., Bujdoso N., Saedler H., Huijser P. (2008). The microRNA regulated SBP-box genes SPL9 and SPL15 control shoot maturation in Arabidopsis. Plant Mol. Biol. 67, 183–195 10.1007/s11103-008-9310-z [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Seo P. J., Ryu J., Kang S. K., Park C. M. (2011). Modulation of sugar metabolism by an INDETERMINATE DOMAIN transcription factor contributes to photoperiodic flowering in Arabidopsis. Plant J. 65, 418–429 10.1111/j.1365-313X.2010.04432.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sgamma T., Jackson A., Muleo R., Thomas B., Massiah A. (2014). TEMPRANILLO is a regulator of juvenility in plants. Sci. Rep. 4:3704 10.1038/srep03704 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sharrock R. A., Quail P. H. (1989). Novel phytochrome sequences in Arabidopsis thaliana: structure, evolution, and differential expression of a plant regulatory photoreceptor family. Genes Dev. 3, 1745–1757 10.1101/gad.3.11.1745 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Smeekens S., Ma J., Hanson J., Rolland F. (2010). Sugar signals and molecular networks controlling plant growth. Curr. Opin. Plant Biol. 13, 274–279 10.1016/j.pbi.2009.12.002 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Somers D. E., Webb A. A., Pearson M., Kay S. A. (1998). The short-period mutant, toc1-1, alters circadian clock regulation of multiple outputs throughout development in Arabidopsis thaliana. Development 125, 485–494 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stettler M., Eicke S., Mettler T., Messerli G., Hortensteiner S., Zeeman S. C. (2009). Blocking the metabolism of starch breakdown products in Arabidopsis leaves triggers chloroplast degradation. Mol. Plant 2, 1233–1246 10.1093/mp/ssp093 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stewart J. L., Maloof J. N., Nemhauser J. L. (2011). PIF genes mediate the effect of sucrose on seedling growth dynamics. PLoS ONE 6:e19894 10.1371/journal.pone.0019894 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stitt M., Zeeman S. C. (2012). Starch turnover: pathways, regulation and role in growth. Curr. Opin. Plant Biol. 15, 282–292 10.1016/j.pbi.2012.03.016 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Su W., Howell S. H. (1992). A single genetic locus, ckr1, defines Arabidopsis mutants in which root growth is resistant to low concentrations of cytokinin. Plant Physiol. 99, 1569–1574 10.1104/pp.99.4.1569 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Swain S. M., Tseng T. S., Thornton T. M., Gopalraj M., Olszewski N. E. (2002). SPINDLY is a nuclear-localized repressor of gibberellin signal transduction expressed throughout the plant. Plant Physiol. 129, 605–615 10.1104/pp.020002 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Szekeres M., Nemeth K., Konczkalman Z., Mathur J., Kauschmann A., Altmann T., et al. (1996). Brassinosteroids rescue the deficiency of CYP90, a cytochrome P450, controlling cell elongation and de-etiolation in arabidopsis. Cell 85, 171–182 10.1016/S0092-8674(00)81094-6 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tanaka K., Asami T., Yoshida S., Nakamura Y., Matsuo T., Okamoto S. (2005). Brassinosteroid homeostasis in Arabidopsis is ensured by feedback expressions of multiple genes involved in its metabolism. Plant Physiol. 138, 1117–1125 10.1104/pp.104.058040 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tseng T. S., Salome P. A., Mcclung C. R., Olszewski N. E. (2004). SPINDLY and GIGANTEA interact and act in Arabidopsis thaliana pathways involved in light responses, flowering, and rhythms in cotyledon movements. Plant Cell 16, 1550–1563 10.1105/tpc.019224 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Turck F., Fornara F., Coupland G. (2008). Regulation and identity of florigen: FLOWERING LOCUS T moves center stage. Annu. Rev. Plant Biol. 59, 573–594 10.1146/annurev.arplant.59.032607.092755 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Turk E. M., Fujioka S., Seto H., Shimada Y., Takatsuto S., Yoshida S., et al. (2005). BAS1 and SOB7 act redundantly to modulate Arabidopsis photomorphogenesis via unique brassinosteroid inactivation mechanisms. Plant J. 42, 23–34 10.1111/j.1365-313X.2005.02358.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tyler L., Thomas S. G., Hu J., Dill A., Alonso J. M., Ecker J. R., et al. (2004). Della proteins and gibberellin-regulated seed germination and floral development in Arabidopsis. Plant Physiol. 135, 1008–1019 10.1104/pp.104.039578 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Van Dijken A. J., Schluepmann H., Smeekens S. C. (2004). Arabidopsis trehalose-6-phosphate synthase 1 is essential for normal vegetative growth and transition to flowering. Plant Physiol. 135, 969–977 10.1104/pp.104.039743 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wahl V., Ponnu J., Schlereth A., Arrivault S., Langenecker T., Franke A., et al. (2013). Regulation of flowering by trehalose-6-phosphate signaling in Arabidopsis thaliana. Science 339, 704–707 10.1126/science.1230406 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wang J. W., Czech B., Weigel D. (2009). miR156-regulated SPL transcription factors define an endogenous flowering pathway in Arabidopsis thaliana. Cell 138, 738–749 10.1016/j.cell.2009.06.014 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wang Y., Li L., Ye T., Lu Y., Chen X., Wu Y. (2013). The inhibitory effect of ABA on floral transition is mediated by ABI5 in Arabidopsis. J. Exp. Bot. 64, 675–684 10.1093/jxb/ers361 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wang Z. Y., Kenigsbuch D., Sun L., Harel E., Ong M. S., Tobin E. M. (1997). A Myb-related transcription factor is involved in the phytochrome regulation of an Arabidopsis Lhcb gene. Plant Cell 9, 491–507 10.1105/tpc.9.4.491 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wigge P. A., Kim M. C., Jaeger K. E., Busch W., Schmid M., Lohmann J. U., et al. (2005). Integration of spatial and temporal information during floral induction in Arabidopsis. Science 309, 1056–1059 10.1126/science.1114358 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wu G., Park M. Y., Conway S. R., Wang J. W., Weigel D., Poethig R. S. (2009). The sequential action of miR156 and miR172 regulates developmental timing in Arabidopsis. Cell 138, 750–759 10.1016/j.cell.2009.06.031 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wuriyanghan H., Zhang B., Cao W. H., Ma B., Lei G., Liu Y. F., et al. (2009). The ethylene receptor ETR2 delays floral transition and affects starch accumulation in rice. Plant Cell 21, 1473–1494 10.1105/tpc.108.065391 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yamaguchi A., Kobayashi Y., Goto K., Abe M., Araki T. (2005). Twin Sister of FT (TSF) acts as a floral pathway integrator redundantly with FT. Plant Cell Physiol. 46, 1175–1189 10.1093/pcp/pci151 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yamaguchi A., Wu M. F., Yang L., Wu G., Poethig R. S., Wagner D. (2009). The microRNA-regulated SBP-Box transcription factor SPL3 is a direct upstream activator of LEAFY, FRUITFULL, and APETALA1. Dev. Cell. 17, 268–278 10.1016/j.devcel.2009.06.007 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yamaguchi-Shinozaki K., Shinozaki K. (2005). Organization of cis-acting regulatory elements in osmotic- and cold-stress-responsive promoters. Trends Plant Sci. 10, 88–94 10.1016/j.tplants.2004.12.012 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yanagisawa S., Yoo S. D., Sheen J. (2003). Differential regulation of EIN3 stability by glucose and ethylene signalling in plants. Nature 425, 521–525 10.1038/nature01984 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yang L., Conway S. R., Poethig R. S. (2011). Vegetative phase change is mediated by a leaf-derived signal that represses the transcription of miR156. Development 138, 245–249 10.1242/dev.058578 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yang L., Xu M., Koo Y., He J., Poethig R. S. (2013). Sugar promotes vegetative phase change in Arabidopsis thaliana by repressing the expression of MIR156A and MIR156C. eLife 2:e00260 10.7554/eLife.00260 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yoo S. K., Chung K. S., Kim J., Lee J. H., Hong S. M., Yoo S. J., et al. (2005). CONSTANS activates SUPPRESSOR OFOVEREXPRESSION OFCONSTANS 1 through FLOWERING LOCUS T to promote flowering in Arabidopsis. Plant Physiol. 139, 770–778 10.1104/pp.105.066928 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yu H., Ito T., Zhao Y., Peng J., Kumar P., Meyerowitz E. M. (2004). Floral homeotic genes are targets of gibberellin signaling in flower development. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 101, 7827–7832 10.1073/pnas.0402377101 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yu S., Cao L., Zhou C.-M., Zhang T.-Q., Lian H., Sun Y., et al. (2013). Sugar is an endogenous cue for juvenile-to-adult phase transition in plants. eLife 2:e00269 10.7554/eLife.00269 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yu S., Galvao V. C., Zhang Y. C., Horrer D., Zhang T. Q., Hao Y. H., et al. (2012). Gibberellin regulates the Arabidopsis floral transition through miR156-targeted SQUAMOSA promoter binding-like transcription factors. Plant Cell 24, 3320–3332 10.1105/tpc.112.101014 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yuan K., Wysocka-Diller J. (2006). Phytohormone signalling pathways interact with sugars during seed germination and seedling development. J. Exp. Bot. 57, 3359–3367 10.1093/jxb/erl096 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zakhleniuk O. V., Raines C. A., Lloyd J. C. (2001). pho3: a phosphorus-deficient mutant of Arabidopsis thaliana (L.) Heynh. Planta 212, 529–534 10.1007/s004250000450 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhang Y., Primavesi L. F., Jhurreea D., Andralojc P. J., Mitchell R. A., Powers S. J., et al. (2009). Inhibition of SNF1-related protein kinase1 activity and regulation of metabolic pathways by trehalose-6-phosphate. Plant Physiol. 149, 1860–1871 10.1104/pp.108.133934 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhou L., Jang J. C., Jones T. L., Sheen J. (1998). Glucose and ethylene signal transduction crosstalk revealed by an Arabidopsis glucose-insensitive mutant. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 95, 10294–10299 10.1073/pnas.95.17.10294 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]