Abstract

After high school, college students escalate their drinking at a faster rate than their noncollege-attending peers, and alcohol use in high school is one of the strongest predictors of alcohol use in college. Therefore, an improved understanding of the role of predictors of alcohol use during the critical developmental period when individuals transition to college has direct clinical implications to reduce alcohol-related harms. We used path analysis in the present study to examine the predictive effects of personality (e.g., impulsivity, sensation seeking, hopelessness, and anxiety sensitivity) and three measures of alcohol perception: descriptive norms, injunctive norms, and perceptions regarding the perceived role of drinking in college on alcohol-related outcomes. Participants were 490 incoming freshmen college students. Results indicated that descriptive norms, injunctive norms, and the role of drinking largely mediated the effects of personality on alcohol outcomes. In contrast, both impulsivity and hopelessness exhibited direct effects on alcohol-related problems. The perceived role of drinking was a particularly robust predictor of outcomes and mediator of the effects of personality traits, including sensation seeking and impulsivity on alcohol outcomes. The intertwined relationships observed in this study between personality factors, descriptive norms, injunctive norms, and the role of drinking highlight the importance of investigating these predictors simultaneously. Findings support the implementation of interventions that target these specific perceptions about the role of drinking in college.

Keywords: personality, social norms, alcohol perceptions, alcohol use, college drinking

The highest prevalence rates for heavy drinking are for individuals between the ages of 18 and 24 (Kanny, Liu, Brewer, Garvin, & Balluz, 2012), and heavy drinking among college students is a public health concern because drinking at this level is linked to numerous negative problems, including interpersonal problems, physical assault, drinking and driving, risky sexual activity, injuries, and death (Hingson, Zha, & Weitzman, 2009). One particularly critical period is when large numbers of emerging adults enter college, navigate a new environment where alcohol use is culturally ingrained, and, on average, significantly increase their alcohol use. After high school, college students escalate their drinking at a faster rate than their noncollege-attending peers (e.g., Blanco et al., 2008). Furthermore, alcohol use in high school is one of the strongest predictors of alcohol use in college (e.g., Borsari, Murphy, & Barnett, 2007; Sher & Rutledge, 2007). Therefore, understanding theoretically relevant predictors of use during this critical period may help improve alcohol prevention efforts for incoming students. Empirical research has identified several predictors of alcohol use by high school and college students, including personality traits, social norms, and alcohol-related perceptions about the role of drinking.

Personality Traits

A variety of personality traits have been investigated as both correlates and moderators of alcohol use and alcohol-related problems (see Maisto, Bishop, & Hart, 2012). Four have emerged as especially influential: (a) impulsivity (a tendency to react to internal or external influences promoting alcohol use, without consideration of possible consequences to oneself or others; Littlefield, Sher, & Wood, 2009; Simons, Gaher, Oliver, Bush, & Palmer, 2005); (b) sensation seeking (the conscious pursuit of activities that result in excitement and pleasure; Cyders, Flory, Rainer, & Smith, 2009); (c) hopelessness (depressed mood; Woicik, Stewart, Pihl, & Conrod, 2009), and (d) anxiety sensitivity (the fear of arousal-related bodily sensations such as rapid breathing, perspiration, and elevated heart rate; DeMartini & Carey, 2011).

Impulsivity, sensation seeking, hopelessness, and anxiety sensitivity have been evaluated as predictors of alcohol use and alcohol-related problems in emerging adults. For example,Woicik et al. (2009) examined the relationships between these four personality traits and substance-use outcomes in two college-student samples (Studies 1 and 2) and a high school sample (Study 3). In one college-student sample (Study 1), hopelessness, impulsivity, and sensation seeking were associated with alcohol abuse and physiological dependence symptoms after controlling for the Big Five personality traits (extraversion, emotional stability, agreeableness, conscientiousness, and openness to experience), whereas anxiety sensitivity was not. In a large high school sample (Study 3), hopelessness, impulsivity, and sensation seeking were all related to both alcohol use and related harms, yet anxiety sensitivity was related to alcohol-related problems only (e.g., Woicik et al., 2009). Thus, these four personality traits appear to be related to alcohol-related outcomes, yet have distinct pathways to heavy drinking.

It is important to note, personality-targeted interventions that have been developed based on “personality-specific motivational pathways to risky drinking” (Conrod, Castellanos-Ryan, & Mackie, 2011, p. 297) have been shown to be efficacious among adolescents (Conrod et al., 2011; Conrod, Castellanos, & Mackie, 2008; Conrod, Stewart, Comeau, & Maclean, 2006), college students (Watt, Stewart, Birch, & Bernier, 2006), and female substance abusers (Conrod et al., 2000). Most of these interventions have targeted the four personality traits reviewed above. Although there is some evidence that the effect of sensation seeking on heavy drinking is partially mediated by response–reward bias (Castellanos-Ryan, Rubia, & Conrod, 2011), and the anxiety-sensitivity-targeted intervention reduces coping motives (Conrod et al., 2011), there is very little understanding of what mediates the effects of these traits on alcohol-related outcomes. Given that personality traits are relatively stable and can have pervasive impacts on behavior, it is not only important to examine how certain personality traits may predispose individuals to different levels of risk for alcohol-related problems, but also to identify more proximal antecedents to alcohol-related outcomes that may mediate the effects of personality.

Perceived Descriptive and Injunctive Norms

Social norms are commonly divided into two types of norms: descriptive and injunctive. Descriptive norms reflect the perceived prevalence, quantity, and/or frequency of drinking by others, whereas injunctive norms reflect the extent to which one believes that others approve/disapprove of their drinking (Cialdini, Kallgren, & Reno, 1991). Both injunctive norms and descriptive norms have been found to directly and independently predict drinking among college students (Borsari & Carey, 2003; Neighbors, Lee, Lewis, Fossos, & Larimer, 2007).

Considerable cross-sectional research shows that the descriptive-norm type is a robust predictor of alcohol use (see Borsari & Carey, 2001 for a review). For example,Neighbors et al. (2007) examined several proximal antecedents to alcohol use, including drinking motives and alcohol expectancies, and found that the descriptive-norm type was the strongest unique predictor of alcohol use when controlling for all variables in the model. Similarly, among student athletes, Hummer, LaBrie, and Lac (2009) found the descriptive norm to be one of the strongest predictors of alcohol consumption when controlling for drinking motives; descriptive norms have been shown to account for unique variance in intentions to drink (H. S. Park, Klein, Smith, & Martell, 2009; Rivis & Sheeran, 2003). Further, changes in descriptive norms have been found to mediate intervention efficacy among college students (e.g., Borsari & Carey, 2000; Doumas, Haustveit, & Coll, 2010; Neighbors, Larimer, & Lewis, 2004).

Several studies have shown positive relationships between perceived drinking approval of others (i.e., injunctive norms) and self-reported drinking behaviors among college students (LaBrie, Hummer, Neighbors, & Larimer, 2010; Larimer, Turner, Mallett, & Geisner, 2004), although this appears to depend to some extent on the specific reference group (LaBrie et al., 2010; Neighbors et al., 2008). Injunctive norms have been shown to account for unique variance in intentions to drink above and beyond descriptive norms (H. S. Park et al., 2009; Rivis & Sheeran, 2003). Although research has shown that injunctive norms are malleable (Prince & Carey, 2010), to our knowledge, no studies have found that change in injunctive norms mediate the effects of an alcohol intervention.

Perceptions About the Role of Drinking in College

Recently,Osberg et al. (2010) developed the College Life Alcohol Salience Scale (CLASS), which measures students’ beliefs about the importance of alcohol to the college experience. These perceptions regarding the role of drinking in college (subsequently, simply “the role of drinking”) have only been examined in a few investigations, but they have been found to be linked to personal alcohol use and problems cross-sectionally (Osberg et al., 2010; Osberg, Insana, Eggert, & Billingsley, 2011) and prospectively (Osberg, Billingsley, Eggert, & Insana, 2012). Although the perceived role of drinking represents the extent to which students identify with the college drinking culture, they are conceptually and empirically distinct from descriptive norms and injunctive norms, as the role of drinking appears to account more for personal perceptions about the purpose of college drinking (e.g., “To become drunk is a college rite of passage”) versus perceptions about peer drinking (descriptive norms) and acceptance about alcohol use (injunctive norms; Osberg et al., 2010). For example, in a study examining the effect of exposure to movies that glorify college drinking on outcomes of alcohol use and alcohol-related problems,Osberg et al. (2012) examined several potential mediators, including the role of drinking, descriptive norms, injunctive norms, positive alcohol expectancies, and negative alcohol expectancies. All of these variables significantly mediated the relationship between college-drinking movie exposure and alcohol use (except for negative alcohol expectancies) and the relationship between movie exposure and alcohol problems (except for injunctive norms). However, the strongest mediated effects were through the role of drinking. Therefore, the perceived role of drinking appears to be a theoretically important and proximal antecedent to alcohol-related outcomes. However, the influence of the role of drinking on personal alcohol use has yet to be evaluated with incoming college students.

Relationship Between Personality, Alcohol Perceptions, and Alcohol Outcomes

As little research has analyzed the role of personality traits on descriptive norms, injunctive norms, and the perceived role of drinking, it is not known if these proximal antecedents may mediate the relationship between personality traits and alcohol-use outcomes (e.g., students who are impulsive may endorse higher descriptive norms, which then influence alcohol-related outcomes). Alternatively, consistent with some previous research (see Maisto et al., 2012 for a review), personality factors (e.g., sensation seeking and impulsivity) may have a direct effect on alcohol use outcomes. Therefore, a theoretically informed examination of the role of personality traits and alcohol-related perceptions on alcohol outcomes is needed.

Several theoretical models place personality traits as distal antecedents to alcohol-related outcomes, whereas perceived descriptive norms and other alcohol-related perceptions represent more proximal antecedents to alcohol-related outcomes. For example, the theory of planned behavior (TPB; Ajzen, 2011) situates personality traits as distal (or “external”) variables that affect behavior through more proximal antecedents like norms and attitudes. Within this theoretical framework, norms have been conceptualized as perceptions about the approval of important others and have been termed subjective norms (Fishbein & Ajzen, 2010). Injunctive norms have been used to refer to the approval of others and is functionally equivalent to subjective norms as operationalized in the TPB. Injunctive norms have received less research attention in the context of college drinking than descriptive norms. Additional guidance on the interplay between personality traits and alcohol-related perceptions come from Cox and Klinger’s (1988) motivational model of alcohol use in which personality traits are distal “historical factors” that affect alcohol use through more proximal antecedents, including “cognitive mediating events,” which are conceptualized as a key process that motivates individuals to abstain or consume alcohol (p. 171). Thus, in the present study, we examine the predictive effects of personality on alcohol-related outcomes through theoretically more proximal antecedents that represent alcohol-related perceptions, including descriptive norms, injunctive norms, and the role of drinking.

Purpose

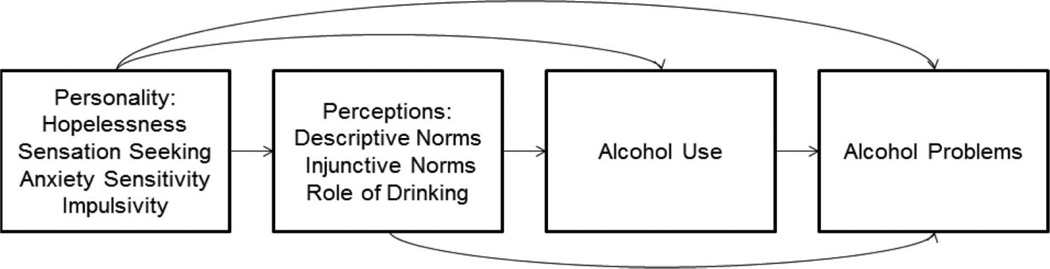

The purpose of this study is to simultaneously evaluate the unique role of theoretically relevant predictors of alcohol use and problems. To do so, we will evaluate the role of four distinct personality traits (impulsivity, sensation seeking, hopelessness, and anxiety sensitivity) and three perceptions about alcohol use (descriptive norms, injunctive norms, and the role of drinking) in predicting alcohol use and alcohol-related problems, as represented in Figure 1. Furthermore, simultaneously evaluating predictors of alcohol-use behaviors provides a unique opportunity to identify the unique influence of several predictors on outcomes. Results from this study may help researchers to prioritize variables that are related to alcohol use and misuse for incoming college students in order to inform treatment development.

Figure 1.

Hypothesized model. Distal antecedents, proximal antecedents, alcohol outcomes, personality–alcohol perceptions.

Overall, we predicted that both personality variables (impulsivity, sensation seeking, hopelessness, and anxiety sensitivity) and mediating variables (descriptive norms, injunctive norms, and the role of drinking) would predict alcohol-related outcomes (see Figure 1). In addition, we expected that the predictive effects of personality traits on alcohol outcomes would be at least partially mediated by descriptive norms, injunctive norms, and the role of drinking. Although the organization of our overall path model is consistent with and guided by theory, we were hesitant to derive specific hypotheses regarding how personality traits would relate to descriptive norms, injunctive norms, and the role of drinking, and how each variable would relate to alcohol-related outcomes in the multivariate model, given the lack of overlap in the personality, perceived drinking norms, and the perceived role of drinking in college literatures.

Method

Participants and Procedures

All incoming first-year undergraduate college students who were entering a large, state university in the mid-Atlantic region were eligible to participate if they had a mailing address in the United States. A group of 1,200 eligible students was randomly selected and they were invited to participate in a randomized controlled trial of an Internet-delivered alcohol-education intervention. Potential participants received a letter in the mail describing the study and they received additional information about the study after they logged into the intervention with their unique username and password. Research participants were entered in a drawing to win one of 10 $50 gift cards that could be used at stores and restaurants near campus for the completion of the follow-up surveys. From the pool of 1,200 randomly selected students, 936 of them (78%) consented to participate and completed the baseline assessment, which took approximately 45 min to complete. The analytic sample included 490 incoming first-year undergraduate college student drinkers who reported consuming alcohol on the baseline assessment. Participants were 49.2% (N = 241) female with an average age of 18.06 (SD = 0.29). Ethnicity was 90.8% (N = 445) White, 6.7% (N = 33) Hispanic, 3.9% (N = 19) Asian, 3.5% (N = 17) Black or African American, and 3.0% (N = 16) was classified as other (participants could select more than one response).

Measures

Participants completed the following measures. The internal consistency (Cronbach’s alpha) of each multi-item inventory is presented in Table 1.

Table 1.

Correlations, Means, Standard Deviations, and Cronbach’s Alphas for Study Variables

| Variable | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | 6 | 7 | 8 | 9 | 10 | M | SD |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1. Hopelessness | .86 | 9.27 | 2.88 | |||||||||

| 2. Sensation seeking | −.17 | .65 | 13.93 | 4.44 | ||||||||

| 3. Anxiety sensitivity | −.08 | −.13 | .68 | 11.09 | 3.92 | |||||||

| 4. Impulsivity | .08 | .30 | .02 | .69 | 5.92 | 3.24 | ||||||

| 5. Role of drinking in college | .03 | .22 | −.01 | .31 | .92 | 42.53 | 8.71 | |||||

| 6. Injunctive norms | .10 | −.16 | .02 | .00 | .17 | — | 2.28 | 0.72 | ||||

| 7. Descriptive norms | .04 | .18 | −.11 | .15 | .41 | .20 | .88 | 20.21 | 11.70 | |||

| 8. Alcohol use | .05 | .23 | −.13 | .17 | .44 | .00 | .58 | — | 10.70 | 9.67 | ||

| 9. Alcohol problems | .17 | .14 | .03 | .33 | .37 | .11 | .27 | .52 | .85 | 3.21 | 3.53 | |

| 10. Gender | −.01 | −.19 | .27 | −.02 | −.19 | −.01 | −.34 | −.27 | .07 | — | 0.49 | .50 |

Note. Significant correlations (p < .05) are in bold typeface for emphasis. Underlined values on the diagonal represent Cronbach’s alphas. The ”role of drinking in college was measured by the College Life Alcohol Salience Scale (CLASS).

Personality

The Substance Use Risk Profile Scale (SURPS; Woicik et al., 2009) is a 23-item measure that was developed using undergraduate and high school student samples and assesses four personality traits (hopelessness, impulsivity, anxiety sensitivity, and sensation seeking) that are associated with substance use. Participants read each item (e.g., “I would like to skydive”) and were asked to select the best response from a 4-point Likert scale ranging from (1) “strongly disagree” to (4) “strongly agree.” Woicik et al. demonstrated that the scale has good internal consistency, convergent and discriminant validity, and 2-month test–retest reliability.

Descriptive norms

Participants completed the Drinking Norms Rating Form (Baer, Stacy, & Larimer, 1991), which asks participants to estimate the amount of alcohol consumed by a typical college student at the host site of the same gender for each day of the week during the past 30 days. Descriptive norms were calculated by summing the responses for each day of the week.

Injunctive norms

Participants completed a single-item measure that asked them to select the response they believed best represents “the most common attitude” among college students at the host site about alcohol use (Perkins & Berkowitz, 1986) using a Likert-response scale (1 = drinking is never a good thing to do to 5 = getting drunk frequently is okay if that’s what the individual wants to do). Injunctive norms are commonly measured with one item (e.g., Turrisi, Mastroleo, Mallett, Larimer, & Kilmer, 2007). Previous research on injunctive norms with college-student samples is similar to ours, in that they also used this single-item measure (Mallett, Bachrach, & Turrisi, 2009). However, multiitem measures of injunctive norms have also been used (e.g., Neighbors et al., 2008).

The role of drinking in college

Perceptions about the role of drinking (i.e., the perceived importance of alcohol use) in college were measured by the summed score of the 15-item College Life Alcohol Salience Scale (CLASS; Osberg et al., 2010) using a 5-point Likert scale (1 = strongly disagree, 5 = strongly agree). Example items from this measure include “Missing class due to a hangover is part of being a true college student” and “The reward at the end of a hard week of studying should be a weekend of heavy drinking.”

Alcohol use

A modified version of the Daily Drinking Questionnaire (DDQ; Collins, Parks, & Marlatt, 1985) was used to assess alcohol consumption during the past 30 days. Participants were asked to report the number of drinks consumed on each day of a typical week. Responses were summed to obtain the average number of drinks consumed per week.

Alcohol-related negative problems

The Brief Young Adult Alcohol Problems Questionnaire (BYAACQ, Kahler, Strong, & Read, 2005) is a 24-item dichotomous (yes/no) inventory used to assess whether participants have experienced a wide-range of alcohol-related problems in the past 30 days. The sum score for this valid and reliable measure (Kahler, Hustad, Barnett, Strong, & Borsari, 2008) was used to reflect the total number of unique alcohol-related problems experienced in the past 30 days.

Data-Analysis Plan

Path analysis using Mplus 6.12 (Muthén & Muthén, 1998) was conducted to examine a theory-based model in which personality variables (impulsivity, sensation seeking, hopelessness, and anxiety sensitivity) were modeled as distal determinants of alcohol outcomes, and perceived drinking norms (descriptive and injunctive) and the role of drinking were modeled as more proximal antecedents to alcohol use and alcohol-related problems. Gender was included in the model as a covariate to account for known gender differences in alcohol use and problems (e.g., Johnston, O’Malley, Bachman, & Schulenberg, 2009; Perkins, 2002). As recommended by mediation experts (Fritz & MacKinnon, 2007; Preacher & Hayes, 2004, 2008), we examined the total, direct, and indirect effects of each predictor variable on outcomes using the bias-corrected bootstrap based on 10,000 bootstrapped samples (Efron & Tibshirani, 1993). Bootstrapping creates empirically derived sampling distributions from which statistical tests are based. It is important to note that bootstrapping does not rely on the assumption that indirect effects are normally distributed and provides a powerful test of mediation (Fritz & MacKinnon, 2007). Across all models, parameters were estimated using maximum likelihood estimation, and missing data were handled using full information maximum likelihood, which is more efficient and has less bias than alternative procedures (Enders, 2001; Enders & Bandalos, 2001).

Results

Preliminary Analyses

The distributions of the outcome variables and the pattern of missing data were examined. Outliers greater than 3 SDs above the mean for each outcome variable were incrementally recoded to one unit above the next lowest value.

Drinker/Nondrinker Comparisons

Given that the ultimate outcome variable was alcohol problems, nondrinkers (n = 446) were dropped from analyses, leaving an analytic sample of 490 college student drinkers for the path analysis. Nondrinkers were defined as participants who did not report drinking alcohol during an average week during the past 30 days. The drinking sample was similar to the nondrinking sample in terms of gender, age, and anxiety sensitivity (see Table 2). However, drinkers were statistically different from nondrinkers in ethnicity, and also reported lower levels of hopelessness, higher sensation seeking and impulsivity, a higher perceived role of drinking, and higher descriptive norms. In addition, there was a trend for drinkers to have higher injunctive norms than nondrinkers (p = .06).

Table 2.

Group Comparisons for Nondrinkers (n = 446) and Drinkers (n = 490)

| Nondrinkers |

Drinkers |

|||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Variable | N (%) | N (%) | χ2 | p |

| Men | 222 (49.8%) | 249 (50.8%) | 0.10 | 0.75 |

| Caucasian | 352 (78.9%) | 445 (90.8%) | 26.11 | <0.001 |

|

M (SD) |

M (SD) |

t |

p |

|

| Age | 18.08 (0.28) | 18.06 (0.29) | 0.68 | 0.49 |

| Hopelessness | 9.78 (3.04) | 9.27 (2.89) | 2.57 | 0.01 |

| Sensation seeking | 12.89 (13.93) | 13.93 (4.44) | −3.46 | <0.001 |

| Anxiety sensitivity | 11.43 (3.99) | 11.10 (4.92) | 1.25 | 0.21 |

| Impulsivity | 5.14 (3.13) | 5.92 (3.24) | −3.66 | <0.001 |

| Role of drinking in college | 31.35 (10.26) | 42.53 (8.72) | −17.69 | <0.0001 |

| Injunctive norms | 2.18 (0.85) | 2.28 (0.72) | −1.91 | 0.06 |

| Descriptive norms | 12.29 (9.99) | 20.21 (11.70) | −10.65 | <0.0001 |

Note. Role of drinking in college was measured by the College Life Alcohol Salience Scale (CLASS).

Descriptive Statistics and Bivariate Correlations of Drinkers

The descriptive statistics and correlations for the variables included in the path model are reported in Table 1. On average, participants reported drinking 10.70 standard drinks in a typical drinking week prematriculation. Participants perceived descriptive norms to be almost twice the amount of their own drinking (M = 19.19, SD = 12.21). On average, perceived injunctive norms indicated that participants felt other students were “moderately” supportive of alcohol use (i.e., “Occasionally getting drunk is okay as long as it doesn’t interfere with academics or other responsibilities”). Participants reported an average of 3.14 (SD = 3.50) alcohol-related problems in the past 30 days.

Regarding significant correlations among the variables, sensation seeking had a modest positive correlation with impulsivity (r = .30) and smaller negative correlations with hopelessness (r = −.17) and anxiety sensitivity (r = −.13). All other personality variables were nonsignificantly correlated. Descriptive norms, injunctive norms, and role of drinking were all positively correlated with each other (rs = .17–.41). The correlations among the personality variables and the correlations among the mediating variables were modest, reducing potential issues related to multicollinearity and suggesting that each variable could have distinct pathways to alcohol-related outcomes.

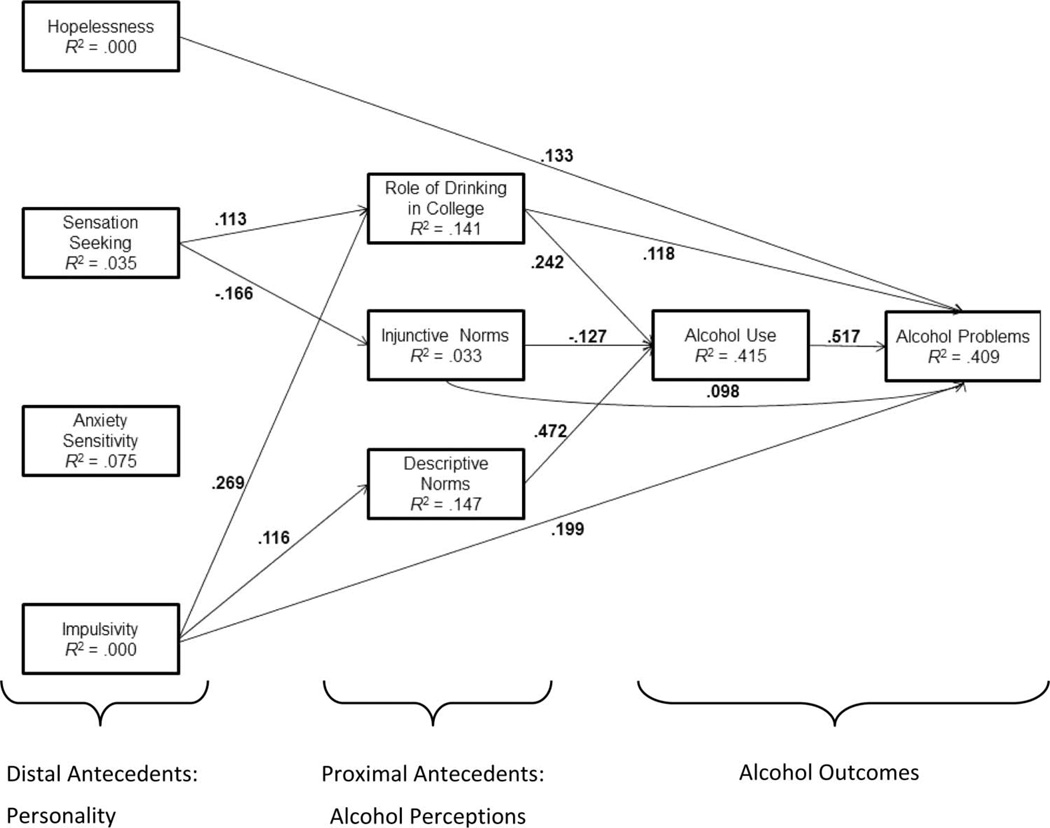

Path Analysis

We examined the direct effects of (a) personality on descriptive norms, injunctive norms, and role of drinking, alcohol use, and alcohol-related problems; and (b) descriptive norms, injunctive norms, and role of drinking on alcohol use and alcohol-related problems. Our model also permitted the examination of indirect (i.e., mediated) effects of (a) personality on alcohol use via descriptive norms, injunctive norms, and role of drinking; (b) personality on alcohol problems via descriptive norms, injunctive norms, and role of drinking, as well as on alcohol use; and (c) descriptive norms, injunctive norms, and role of drinking on alcohol problems via alcohol use. All significant direct effects of personality, descriptive norms, injunctive norms, and role of drinking on alcohol outcomes are shown in Figure 2. All direct, indirect, and total effects are shown in Table 3. To control for gender, a dummy-coded gender variable (0 = men, 1 = women) was entered as a predictor of all other variables. In the following decomposition of the direct, indirect, and total effects, we report the standardized regression coefficients to provide more interpretable indicators of effect size, but all p values are based on the unstandardized results.

Figure 2.

Path model of associations among personality traits, social norms, perceptions about the role of drinking in college, alcohol use, and alcohol problems. Role of drinking in college was measured by the College Life Alcohol Salience Scale (CLASS; Osberg et al., 2010). Only significant effects (p < .05) are shown. Although the correlations among personality variables as well as the correlations among alcohol-perception variables were estimated, they are not shown for reasons of parsimony. Gender was controlled for by entering it as an exogenous predictor of all study variables; these effects are also omitted for clarity.

Table 3.

Total, Direct, and Indirect Effects of Personality on Alcohol Outcomes Through Descriptive Norms, Injunctive Norms, and the Role of Drinking

| Independent variable: |

Hopelessness |

Sensation seeking |

Anxiety sensitivity |

Impulsivity |

||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Dependent variable: Alcohol use | β | B | 95% CI | p | β | B | 95% CI | p | β | B | 95% CI | p | β | B | 95% CI | p |

| Total indirect effects | .02 | .07 | (−.11, .27) | .503 | .09 | .20 | (.07, .35) | .004 | .01 | .02 | (−.12, .16) | .832 | .11 | .34 | (.16, .55) | .001 |

| Specific indirect effects | ||||||||||||||||

| Descriptive norms | .02 | .07 | (−.07, .24) | .380 | .04 | .10 | (−.01, .22) | .081 | −.01 | −.01 | (−.11, .11) | .840 | .06 | .16 | (.03, .32) | .028 |

| Injunctive norms | −.01 | −.03 | (−.09, .01) | .254 | .02 | .05 | (.02, .09) | .021 | −.00 | −.01 | (−.04, .03) | .795 | −.01 | −.02 | (−.06, .02) | .363 |

| Role of Drinking | .01 | .02 | (−.04, .10) | .542 | .03 | .06 | (.01, .13) | .034 | .01 | .03 | (−.02, .09) | .265 | .07 | .19 | (.11, .31) | <.001 |

| Direct effect | .04 | .13 | (−.15, .40) | .350 | .07 | .15 | (−.03, .33) | .096 | −.05 | −.13 | (−.32, .06) | .164 | .00 | .00 | (−.23, .24) | .970 |

| Total effect | .06 | .20 | (−.09, .48) | .171 | .16 | .35 | (.14, .56) | .001 | −.05 | −.12 | (−.33, .11) | .298 | .12 | .35 | (.03, .66) | .031 |

| Dependent variable: BYAACQ | β | B | 95% CI | p | β | B | 95% CI | p | β | B | 95% CI | p | β | B | 95% CI | p |

| Total indirect | .04 | .05 | (−.01, .11) | .138 | .07 | .06 | (.02, .10) | .010 | −.02 | −.02 | (−.06, .03) | .515 | .09 | .10 | (.03, .17) | .005 |

| Specific indirect effects | ||||||||||||||||

| Descriptive Norms | −.00 | −.00 | (−.02, .00) | .511 | −.01 | −.01 | (−.02, .00) | .272 | .00 | .00 | (−.01, .01) | .864 | −.01 | −.01 | (−.03, .00) | .218 |

| Injunctive norms | .01 | .01 | (−.00, .03) | .301 | −.02 | −.01 | (−.03, −.00) | .056 | .00 | .00 | (−.01, .01) | .803 | .00 | .01 | (−.00, .02) | .394 |

| Role of drinking | .00 | .00 | (−.01, .02) | .576 | .01 | .01 | (.00, .03) | .091 | .01 | .01 | (−.00, .02) | .316 | .03 | .04 | (.01, .07) | .021 |

| Alcohol use | .02 | .03 | (−.03, .08) | .365 | .04 | .03 | (−.00, .07) | .117 | −.03 | −.03 | (−.06, .01) | .171 | .00 | .00 | (−.05, .05) | .971 |

| Descriptive norms → Alcohol use | .01 | .01 | (−.01, .05) | .387 | .02 | .02 | (−.00, .04) | .080 | −.00 | −.00 | (−.02, .02) | .840 | .03 | .03 | (.01, .06) | .027 |

| Injunctive norms → Alcohol use | −.00 | −.01 | (−.02, .00) | .257 | .01 | .01 | (.00, .02) | .025 | −.00 | −.00 | (−.01, .01) | .796 | −.00 | −.00 | (−.01, .00) | .365 |

| Role of drinking → Alcohol use | .00 | .00 | (−.01, .02) | .548 | .01 | .01 | (.00, .03) | .040 | .01 | .01 | (−.00, .02) | .273 | .03 | .04 | (.02, .06) | <.001 |

| Direct effect | .13 | .16 | (.07, .27) | .002 | .03 | .02 | (−.03, .08) | .468 | .04 | .04 | (−.03, .11) | .303 | .20 | .22 | (.12, .32) | <.001 |

| Total effect | .17 | .21 | (.09, .34) | .001 | .10 | .08 | (.02, .15) | .018 | .02 | .02 | (−.06, .11) | .618 | .29 | .31 | (.20, .43) | <.001 |

Note. BYAACQ − Brief Young Adult Alcohol Problems Questionnaire. All parameter estimates and significance tests are based on 10,000 bootstrapped samples. Significant effects are determined by both a 95% CI that does not include zero and ps < .05, which are in bold typeface for emphasis.

Direct Effects

Examination of direct effects indicates that each personality variable and each alcohol-perception variable had a unique relationship with alcohol-related outcomes.

Personality on perceived drinking norms and the perceived role of drinking in college

Descriptive norms, injunctive norms, and role of drinking were each associated with a unique set of personality variables. Higher levels of sensation seeking (p = .001) were related to lower injunctive norms. Impulsivity (p < .001) and sensation seeking (p = .018) were positively related to role of drinking. Impulsivity (p = .028) was significantly associated with high descriptive norms. Hopelessness and anxiety sensitivity did not exert any direct effects on descriptive norms, injunctive norms, or role of drinking.

Personality on alcohol outcomes

Both hopelessness (p = .002) and impulsivity (p < .001) had positive direct effects on alcohol-related problems after controlling for gender, the remaining personality variables, descriptive norms, injunctive norms, and role of drinking.

Perceived drinking norms and the role of drinking in college on alcohol outcomes

Descriptive norms, injunctive norms, and role of drinking had direct effects on alcohol consumption. Specifically, the role of drinking (p < .001) and descriptive norms (p < .001) were associated with more alcohol use. In contrast, injunctive norms were negatively related to alcohol use (p = .001). In addition, the role of drinking (p = .009) and injunctive norms (p = .022) had direct effects on alcohol-related problems. However, descriptive norms (β = −.067, p = .140) were not directly associated with alcohol-related problems.

Indirect Effects

Personality on alcohol use via perceived drinking norms and the perceived role of drinking in college

The predictive effect of sensation seeking on alcohol use was fully mediated by role of drinking (indirect effect [IND] β = .03, p = .034) and injunctive norms (IND β = .02, p = .021). In addition, the indirect effect of sensation seeking on alcohol use through descriptive norms was marginal (IND β = .04, p = .081). In other words, there was a significant total effect of sensation seeking (total effect [TOT] β = .16, p = .001) on alcohol use while controlling for gender and other personality variables in the model, but this effect became marginally significant when controlling for descriptive norms, injunctive norms, and role of drinking (direct effect [DIR] β = .07, p = .096).

The predictive effect of impulsivity on alcohol use was fully mediated by descriptive norms (IND β = .06, p = .028) and role of drinking (IND β = .07, p < .001). The total effect of impulsivity on alcohol use (TOT β = .12, p = .031) was significant, but dropped to near zero when controlling for descriptive norms, injunctive norms, and role of drinking (DIR β = .00, p = .970).

Personality on alcohol problems via perceived drinking norms, perceptions about the role of drinking in college, and alcohol use

The predictive effect of sensation seeking on alcohol problems was fully mediated by descriptive norms, injunctive norms, the role of drinking, and alcohol use. The total effect of sensation seeking on alcohol problems was significant (TOT β = .10, p = .018), but this effect became nonsignificant when controlling for descriptive norms, injunctive norms, role of drinking, and alcohol use (DIR β = .03, p = .468). The indirect effects of sensation seeking on alcohol problems via injunctive norms (IND β = −.02, p = .056) and role of drinking (IND β = .01, p = .091) approached significance (ps < .10). However, the doublemediated effect via injunctive norms and alcohol use (IND β = .01, p = .025) and double-mediated effect via role of drinking and alcohol use (IND β = .01, p = .040) were both statistically significant. It is important to note that all of the indirect effects together fully mediated the predictive effects of sensation seeking on alcohol problems as shown by the stronger total indirect effect (total indirect effect [TOT IND] β = .07, p = .010).

The predictive effect of impulsivity on alcohol problems was only partially mediated by descriptive norms, injunctive norms, the role of drinking, and alcohol use. The total effect of impulsivity on alcohol problems was significant (TOT β = .29, p < .001), but so was the direct effect (DIR β = .20, p < .001). The indirect effects of impulsivity on alcohol problems via role of drinking directly (IND β = .03, p = .021), descriptive norms and alcohol use (IND β = .03, p = .027), and role of drinking and alcohol use (IND β = .03, p < .001) were all significant (TOT IND β = .09, p = .005). Hopelessness and anxiety sensitivity did not have any significant indirect effects on alcohol use or alcohol-related problems.

Perceived drinking norms and perceptions about the role of drinking in college on alcohol problems via alcohol use

The predictive effects of descriptive norms, injunctive norms, and role of drinking on alcohol problems were partially or fully mediated by alcohol use. The total effect of role of drinking on problems was significant (TOT β = .24, p < .001), as was the direct effect (DIR β = .12, p = .009). The predictive effects of descriptive norms on alcohol problems was fully mediated by alcohol use (IND β = .24, p < .001). Specifically, the significant total effect of descriptive norms on alcohol problems (TOT β = .18, p < .001) became nonsignificant when controlling for alcohol use (DIR β = −.07, p = .140). Injunctive norms did not have a significant total effect on alcohol problems (TOT β = .03, p = .469), but showed evidence of suppression as its direct effect on alcohol problems when controlling for other variables in the model was positive (DIR β = .10, p = .022), but its indirect effect on alcohol problems via alcohol use was negative (IND β = −.07, p = .001).

Covariate Effects

Significant gender differences deserve mention. Although gender was unrelated to hopelessness or impulsivity, women endorsed higher levels of anxiety sensitivity (β = .27, p < .001) and lower levels of sensation seeking (β = −.19, p < .001) than men. Women also reported lower descriptive norms (β = −.32, p < .001) and lower perceptions of the role of drinking (β = −.18, p < .001) than men. When controlling for all personality and alcohol perception factors, there was no significant gender difference in alcohol use, but women reported experiencing more alcohol-related problems than men (β = .20, p < .001).

Discussion

In this study, we explored the relationship between theoretically relevant variables and alcohol use and alcohol-related problems in a sample of incoming college-students drinkers. The inclusion of personality factors provided an opportunity to evaluate the unique influence of individual characteristics on descriptive norms, injunctive norms, the role of drinking, and outcomes. Findings indicate that the predictive effects of two personality traits (impulsivity and sensation seeking) on alcohol use were fully mediated by perceived descriptive norms and the role of drinking, and their effect on alcohol-related problems were fully (for sensation seeking) and partially (for impulsivity) mediated by perceived descriptive norms, the role of drinking, and alcohol use. Specifically, there were significant indirect effects through each of the mediating measures, suggesting that they each may play a unique role in explaining how personality relates to alcohol outcomes. We found it interesting that the most consistent and strongest mediation pathways were through perceptions about the role of drinking in college. As interventions targeted toward perceived descriptive norms are prevalent (Wechsler et al., 2003), it has been well-accepted that descriptive norms are proximal antecedents to alcohol outcomes. Although the magnitude of the significant indirect effects of personality on alcohol-related outcomes via alcohol perception variables was small (Bs = .01 to .19), it is consistent with other research examining the influence of personality on behavior (e.g., A. Park, Sher, Wood, & Krull, 2009; Quinn & Fromme, 2011; Rice & Van Arsdale, 2010; Treloar, Morris, Pedersen, & McCarthy, 2012). It is also worth noting that the specific indirect effects represent unique effects of multiple mediators, and indirect pathways through multiple outcomes will necessarily be smaller. For example, effects averaging .3 magnitude through three pathways would have an indirect effect of only .027. That said, these findings suggest that the role of drinking may also be a prime target for interventions.

Consistent with previous studies, impulsivity and sensation seeking were strong predictors of alcohol use and problems (e.g., McAdams & Donnellan, 2009; Zuckerman, 2007). Of particular interest was that impulsivity and sensation seeking had indirect effects on alcohol use, which was mediated through descriptive norms, injunctive norms, and the role of drinking. Although individuals who have higher levels of sensation seeking are presumed to engage in heavy drinking in an attempt to seek novel, exciting experiences (Zuckerman, 1994), highly impulsive individuals are also presumed to engage in heavy drinking due to deficits in behavioral control (e.g., poor response inhibition; Castellanos-Ryan et al., 2011). Despite theoretically distinct motivational pathways to alcohol misuse, the perceptions of others’ behaviors (descriptive norms) and others’ beliefs (injunctive norms), and overall perceptions of the role of drinking in college helped to explain the relationship between these personality traits and alcohol use and problems. It is important for future research to determine why such distinct personality traits share similar cognitive mediators. We speculate that individuals high in sensation seeking may have higher perceived importance of the role of drinking in college as they develop a global view of life and perhaps the college years specifically as a time for exploring novel experiences, which happens to include heavy drinking. Highly impulsive individuals who exhibit an inability to resist temptations to drink in high-risk situations may develop higher perceived importance of the role of drinking in an attempt to rationalize their heavy drinking, which may, in turn, minimize their own cognitive dissonance. It is important for future research to empirically examine such speculations.

Contrary to a previous study with an adolescent sample (Woicik et al., 2009), hopelessness and anxiety sensitivity were not significantly related to alcohol use or alcohol-related problems. The reason for this discrepant relationship is not clear. It is possible that relationships might differ once students leave secure social networks and set foot on campus and are immersed in a new social environment. As such, anxiety sensitivity and hopelessness would be more positively related to college-student drinking once students begin navigating new social relationships.

It is important to highlight that the purpose of this study was not to find the “best” predictor of alcohol use and related problems. However, these results are consistent with previous studies that have highlighted the importance of college students’ perceptions. Specifically, descriptive norms, injunctive norms, and the role of drinking were significant predictors of both alcohol use and alcohol-related problems; however, their relationships with alcohol problems was not as strong (Neighbors et al., 2007). Collectively, these results indicate that these variables represent unique constructs that influence behavior. These findings not only add to the specificity of theory, but also provide directions in terms of targets for intervention development.

Clinical Implications

The current study indicated that perceptions about college drinking prior to matriculation were directly related to alcohol use and alcohol-related problems in incoming college students. Thus, it appears that incoming students who drink alcohol already have positive perceptions about drinking in college. Given these results, primary and indicated interventions that specifically target the perceived importance of drinking as part of the college experience are warranted. As descriptive norms, injunctive norms, and the role of drinking were related to alcohol-use involvement during the transition from high school to college, it seems that providing a multicomponent primary intervention addressing descriptive norms, injunctive norms, and the role of drinking may have the strongest effect on alcohol use by incoming students.

An indicated, personality-targeted intervention could address the specific mediational pathways of each personality trait and the role of drinking could be an additional intervention component for individuals high in impulsivity and sensation seeking (Conrod et al., 2011). Specifically, as the role of drinking mediated the effects of both sensation seeking and impulsivity on alcohol-related outcomes, an intervention focusing on modifying the perceived importance of the role of drinking in college may be more effective for those with higher levels of sensation seeking and impulsivity. Recommendations to modify the role of drinking include modifying the campus environment and drinking culture (e.g., alcohol outlet density, increased enforcement and fines) and attempting to modify the degree to which individuals “[internalize] the drinking culture” (Osberg et al., 2012, p. 925). It is plausible that the internalization of the drinking culture can be diluted by motivating individuals to participate in alcohol-free leisure activities (e.g., Murphy et al., 2012; Yarnal, Qian, Hustad, & Sims, 2013). In addition, it is notable that some of the questions on the CLASS (Osberg et al., 2010), which was used to assess the role of drinking, are similar to questions that assess personal values about alcohol use on a separate measure (e.g., “alcohol—beer, wine, or liquor—plays an important role in my enjoyment of life,” and “drinking alcohol is simply part of a normal social life”; Slater, 2001, p. 266); interventions aimed at changing personal values may be an effective strategy to reduce alcohol use by modifying the perceived role of drinking. However, the efficacy of values-clarification interventions remains mixed (Larimer & Cronce, 2002).

Limitations and Recommendations for Future Research

The results of this study should be interpreted with the acknowledgment of the following limitations. First, it was cross-sectional in nature and so we could not infer cause and effect. Longitudinal studies examining the predictive effects of personality on alcohol outcomes would improve the ability to examine mediation. Second, although the high consent rate (78%) from randomly selected incoming students and the moderate sample size increases our confidence in these results, we recognize that this study was conducted at a single university with incoming college students, so we must be careful when generalizing these results to distinct populations (e.g., college students as a whole, noncollege students). However, the number of drinks consumed per week in this sample (M = 10.70) is similar to a separate sample of incoming college-student drinkers from a different college (M = 11.51; Hustad, Barnett, Borsari, & Jackson, 2010), suggesting that these results may generalize to other samples of incoming student drinkers. Third, despite the fact that previous research has shown little evidence for bias in self-reported alcohol use in college students (Borsari & Muellerleile, 2009), it is important to point out the limitations of using only retrospective self-reports of alcohol use and alcohol-related problems. Using ecological momentary assessment (EMA; Shiffman, 2009) or transdermal alcohol monitoring (Dougherty et al., 2012) would be a better way to ensure that our findings do not depend on retrospective memory biases. Fourth, the present study was exploratory, in that we were unable to develop hypotheses regarding the specific direct and indirect effects of personality on alcohol-related outcomes, so these findings should be viewed as preliminary. Fifth, some of the subscales from our measure of personality (SURPS; Woicik et al., 2009) had modest internal consistency estimates in this sample, and our single-item measure of injunctive norms prevented any examination of reliability. Thus, it is important for researchers to use more reliable measures and/or use methods that correct for measurement error (e.g., structural equation modeling) so that potentially important relationships between variables are not underestimated. Finally, it is important to note that a substantial portion (47.6%) of incoming college students did not drink at the time of assessment. Given that these individuals were not part of our path analysis, it is important for future research to include these nondrinkers in longitudinal analyses to examine how personality traits, descriptive norms, injunctive norms, and the perceived role of drinking may predict the transition to alcohol use.

Conclusion

In summary, our multivariate path analysis indicated that personality, descriptive norms, injunctive norms, and the role of drinking can operate in direct and indirect fashions on alcohol outcomes. The CLASS is a promising new measure of perceptions about the role of drinking in college that may potentially inform prevention science. It would be ideal if these findings could assist with the development and implementation of alcohol interventions to reduce alcohol use by incoming students.

Acknowledgments

This research was supported by the National Center for Research Resources and the National Center for Advancing Translational Sciences, National Institutes of Health (NIH), through Grant UL1RR033184 and KL2RR033180 to Lawrence Sinoway. Brian Borsari’s contribution to this manuscript was supported by National Institute on Alcohol Abuse and Alcoholism Grant R01AA017874. The content is solely the responsibility of the authors and does not necessarily represent the official views of the National Institute on Alcohol Abuse and Alcoholism, the National Institutes of Health, or the Department of Veterans Affairs or the United States Government. The authors would like to thank everyone who contributed significantly to the work, including the participants and Michelle Loxley. We gratefully acknowledge the support of this research study from campus administrators, including Philip Burlingame, Andrea Dowhower, Linda LaSalle, and Damon Sims.

Contributor Information

John T. P. Hustad, Pennsylvania State University College of Medicine, Department of Medicine and Public Health Sciences

Matthew R. Pearson, Center on Alcoholism, Substance Abuse, and Addictions, University of New Mexico

Clayton Neighbors, Department of Psychology, University of Houston.

Brian Borsari, Mental Health and Behavioral Sciences Service, Providence Veterans Affairs Medical Center, Providence, Rhode Island and Center for Alcohol and Addiction Studies, Brown University.

References

- Ajzen I. The theory of planned behaviour: Reactions and reflections. Psychology & Health. 2011;26:1113–1127. doi: 10.1080/08870446.2011.613995. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Baer JS, Stacy A, Larimer ME. Biases in perception of drinking norms among college students. Journal of Studies on Alcohol. 1991;52:580–586. doi: 10.15288/jsa.1991.52.580. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Blanco C, Okuda M, Wright C, Hasin DS, Grant BF, Liu SM, Olfson M. Mental health of college students and their non-college-attending peers: Results from the National Epidemiologic Study on Alcohol and Related Conditions. Archives of General Psychiatry. 2008;65:1429–1437. doi: 10.1001/archpsyc.65.12.1429. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Borsari B, Carey KB. Effects of a brief motivational intervention with college student drinkers. Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology. 2000;68:728–733. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Borsari B, Carey KB. Peer influences on college drinking: A review of the research. Journal of Substance Abuse. 2001;13:391–424. doi: 10.1016/s0899-3289(01)00098-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Borsari B, Carey KB. Descriptive and injunctive norms in college drinking: A meta-analytic integration. Journal of Studies on Alcohol. 2003;64:331–341. doi: 10.15288/jsa.2003.64.331. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Borsari B, Muellerleile P. Collateral reports in the college setting: A meta-analytic integration. Alcoholism, Clinical and Experimental Research. 2009;33:826–838. doi: 10.1111/j.1530-0277.2009.00902.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Borsari B, Murphy JG, Barnett NP. Predictors of alcohol use during the first year of college: Implications for prevention. Addictive Behaviors. 2007;32:2062–2086. doi: 10.1016/j.addbeh.2007.01.017. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Castellanos-Ryan N, Rubia K, Conrod PJ. Response inhibition and reward response bias mediate the predictive relationships between impulsivity and sensation seeking and common and unique variance in conduct disorder and substance misuse. Alcoholism: Clinical and Experimental Research. 2011;35:140–155. doi: 10.1111/j.1530-0277.2010.01331.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cialdini RB, Kallgren CA, Reno RR. A focus theory of normative conduct: A theoretical refinement and reevaluation of the role of norms in human behavior. In: Mark PZ, editor. Advances in experimental social psychology. Vol. 24. San Diego, CA: Academic Press; 1991. pp. 201–234. [Google Scholar]

- Collins RL, Parks GA, Marlatt GA. Social determinants of alcohol consumption: The effects of social interaction and model status on the self-administration of alcohol. Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology. 1985;53:189–200. doi: 10.1037//0022-006x.53.2.189. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Conrod PJ, Castellanos N, Mackie C. Personality-targeted interventions delay the growth of adolescent drinking and binge drinking. Journal of Child Psychology and Psychiatry. 2008;49:181–190. doi: 10.1111/j.1469-7610.2007.01826.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Conrod PJ, Castellanos-Ryan N, Mackie C. Long-term effects of a personality-targeted intervention to reduce alcohol use in adolescents. Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology. 2011;79:296–306. doi: 10.1037/a0022997. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Conrod PJ, Stewart SH, Comeau N, Maclean AM. Efficacy of Cognitive–Behavioral Interventions Targeting Personality Risk Factors for Youth Alcohol Misuse. Journal of Clinical Child and Adolescent Psychology. 2006;35:550–563. doi: 10.1207/s15374424jccp3504_6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Conrod PJ, Stewart SH, Pihl RO, Côté S, Fontaine V, Dongier M. Efficacy of brief coping skills interventions that match different personality profiles of female substance abusers. Psychology of Addictive Behaviors. 2000;14:231–242. doi: 10.1037//0893-164x.14.3.231. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cox WM, Klinger E. A motivational model of alcohol use. Journal of Abnormal Psychology. 1988;97:168–180. doi: 10.1037//0021-843x.97.2.168. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cyders MA, Flory K, Rainer S, Smith GT. The role of personality dispositions to risky behavior in predicting first-year college drinking. Addiction. 2009;104:193–202. doi: 10.1111/j.1360-0443.2008.02434.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- DeMartini KS, Carey KB. The role of anxiety sensitivity and drinking motives in predicting alcohol use: A critical review. Clinical Psychology Review. 2011;31:169–177. doi: 10.1016/j.cpr.2010.10.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dougherty DM, Charles NE, Acheson A, John S, Furr RM, Hill-Kapturczak N. Comparing the detection of transdermal and breath alcohol concentrations during periods of alcohol consumption ranging from moderate drinking to binge drinking. Experimental and Clinical Psychopharmacology. 2012;20:373–381. doi: 10.1037/a0029021. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Doumas DM, Haustveit T, Coll KM. Reducing heavy drinking among first year intercollegiate athletes: A randomized controlled trial of web-based normative feedback. Journal of Applied Sport Psychology. 2010;22:247–261. [Google Scholar]

- Efron B, Tibshirani R. An introduction to the bootstrap. New York, NY: Chapman and Hall; 1993. [Google Scholar]

- Enders CK. The performance of the full information maximum likelihood estimator in multiple regression models with missing data. Educational and Psychological Measurement. 2001;61:713–740. [Google Scholar]

- Enders CK, Bandalos DL. The relative performance of full information maximum likelihood for missing data in structural equation models. Structural Equation Modeling. 2001;8:430–457. [Google Scholar]

- Fishbein M, Ajzen I. Predicting and changing behavior: The reasoned action approach. New York, NY: Psychology Press; 2010. [Google Scholar]

- Fritz MS, MacKinnon DP. Required Sample Size to Detect the Mediated Effect. Psychological Science. 2007;18:233–239. doi: 10.1111/j.1467-9280.2007.01882.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hingson RW, Zha W, Weitzman ER. Magnitude of and the trends in alcohol-related mortality and morbidity among U.S. college students ages 18–24, 1998–2005. Journal of Studies on Alcohol and Drugs. 2009;16:12–20. doi: 10.15288/jsads.2009.s16.12. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hummer JF, LaBrie JW, Lac A. The prognostic power of normative influences among NCAA student-athletes. Addictive Behaviors. 2009;34:573–580. doi: 10.1016/j.addbeh.2009.03.021. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hustad JTP, Barnett NP, Borsari B, Jackson KM. Web-based alcohol prevention for incoming college students: A randomized controlled trial. 2010. Unpublished raw data. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Johnston LD, O’Malley PM, Bachman JG, Schulenberg JE. Volume II: College students and adults ages 19–50. Bethesda, MD: United States Department of Health and Human Services, National Institutes of Health, National Institute on Drug Abuse; 2009. Monitoring the future: National survey results on drug use, 1975–2008. [Google Scholar]

- Kahler CW, Hustad JTP, Barnett NP, Strong DR, Borsari B. Validation of the 30-Day version of the Brief Young Adult Alcohol Consequences Questionnaire for use in longitudinal studies. Journal of Studies on Alcohol and Drugs. 2008;69:611–615. doi: 10.15288/jsad.2008.69.611. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kahler CW, Strong DR, Read JP. Toward efficient and comprehensive measurement of the alcohol problems continuum in college students: The Brief Young Adult Alcohol Consequences Questionnaire. Alcoholism: Clinical and Experimental Research. 2005;29:1180–1189. doi: 10.1097/01.alc.0000171940.95813.a5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kanny D, Liu Y, Brewer RD, Garvin WS, Balluz L. Vital signs: Binge drinking prevalence, frequency, and intensity among adults: United States, 2010. Morbidity and Mortality Weekly Report. 2012;61:14–19. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- LaBrie JW, Hummer JF, Neighbors C, Larimer ME. Whose opinion matters? The relationship between injunctive norms and alcohol consequences in college students. Addictive Behaviors. 2010;35(4):343–349. doi: 10.1016/j.addbeh.2009.12.003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Larimer ME, Cronce JM. Identification, prevention and treatment: A review of individual-focused strategies to reduce problematic alcohol consumption by college students. Journal of Studies on Alcohol. 2002;14:148–163. doi: 10.15288/jsas.2002.s14.148. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Larimer ME, Turner AP, Mallett KA, Geisner IM. Predicting drinking behavior and alcohol-related problems among fraternity and sorority members: Examining the role of descriptive and injunctive norms. Psychology of Addictive Behaviors. 2004;18:203–212. doi: 10.1037/0893-164X.18.3.203. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Littlefield AK, Sher KJ, Wood PK. Is “maturing out” of problematic alcohol involvement related to personality change? Journal of Abnormal Psychology. 2009;118:360–374. doi: 10.1037/a0015125. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Maisto SA, Bishop TM, Hart EJ. Theories of college student drinking. In: Correia CJ, Murphy JG, Barnett NP, editors. College student alcohol abuse: A guide to assessment, intervention, and prevention. Hoboken, NJ: Wiley; 2012. pp. 81–112. [Google Scholar]

- Mallett KA, Bachrach RL, Turrisi R. Examining the unique influence of interpersonal and intrapersonal drinking perceptions on alcohol consumption among college students. Journal of Studies on Alcohol and Drugs. 2009;70:178–185. doi: 10.15288/jsad.2009.70.178. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McAdams KK, Donnellan MB. Facets of personality and drinking in first-year college students. Personality and Individual Differences. 2009;46:207–212. [Google Scholar]

- Murphy JG, Dennhardt AA, Skidmore JR, Borsari B, Barnett NP, Colby SM, Martens MP. A randomized controlled trial of a behavioral economic Suppl. to brief motivational interventions for college drinking. Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology. 2012;80:876–886. doi: 10.1037/a0028763. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Muthén LK, Muthén BO. MPlus user’s guide. Los Angeles, CA: Muthén & Muthén; 1998. [Google Scholar]

- Neighbors C, Larimer ME, Lewis MA. Targeting misperceptions of descriptive drinking norms: Efficacy of a computer-delivered personalized normative feedback intervention. Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology. 2004;72:434–447. doi: 10.1037/0022-006X.72.3.434. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Neighbors C, Lee CM, Lewis MA, Fossos N, Larimer ME. Are social norms the best predictor of outcomes among heavydrinking college students? Journal of Studies on Alcohol and Drugs. 2007;68:556–565. doi: 10.15288/jsad.2007.68.556. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Neighbors C, O’Connor RM, Lewis MA, Chawla N, Lee CM, Fossos N. The relative impact of injunctive norms on college student drinking: The role of reference group. Psychology of Addictive Behaviors. 2008;22:576–581. doi: 10.1037/a0013043. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Osberg TM, Atkins L, Buchholz L, Shirshova V, Swiantek A, Whitley J, Oquendo N. Development and validation of the College Life Alcohol Salience Scale: A measure of beliefs about the role of alcohol in college life. Psychology of Addictive Behaviors. 2010;24:1–12. doi: 10.1037/a0018197. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Osberg TM, Billingsley K, Eggert M, Insana M. From. Animal House to Old School: A multiple mediation analysis of the association between college drinking movie exposure and freshman drinking and its consequences. Addictive Behaviors. 2012;37:922–930. doi: 10.1016/j.addbeh.2012.03.030. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Osberg TM, Insana M, Eggert M, Billingsley K. Incremental validity of college alcohol beliefs in the prediction of freshman drinking and its consequences: A prospective study. Addictive Behaviors. 2011;36:333–340. doi: 10.1016/j.addbeh.2010.12.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Park A, Sher KJ, Wood PK, Krull JL. Dual mechanisms underlying accentuation of risky drinking via fraternity/sorority affiliation: The role of personality, peer norms, and alcohol availability. Journal of Abnormal Psychology. 2009;118:241–255. doi: 10.1037/a0015126. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Park HS, Klein KA, Smith S, Martell D. Separating subjective norms, university descriptive and injunctive norms, and U.S. descriptive and injunctive norms for drinking behavior intentions. Health Communication. 2009;24:746–751. doi: 10.1080/10410230903265912. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Perkins HW. Surveying the damage: A review of research on consequences of alcohol misuse in college populations. Journal of Studies on Alcohol. 2002;14:91–100. doi: 10.15288/jsas.2002.s14.91. [Special issue: College drinking, what it is, and what do to about it. Review of the state of the science] [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Perkins HW, Berkowitz AD. Perceiving the community norms of alcohol use among students: Some research implications for campus alcohol education programming. International Journal of the Addictions. 1986;21:961–976. doi: 10.3109/10826088609077249. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Preacher KJ, Hayes AF. SPSS and SAS procedures for estimating indirect effects in simple mediation models. Behavior Research Methods, Instruments & Computers. 2004;36:717–731. doi: 10.3758/bf03206553. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Preacher KJ, Hayes AF. Contemporary approaches to assessing mediation in communication research. In: Hayes AF, Slater MD, Snyder LB, editors. The Sage sourcebook of advanced data analysis methods for communication research. Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage; 2008. pp. 13–54. [Google Scholar]

- Prince MA, Carey KB. The malleability of injunctive norms among college students. Addictive Behaviors. 2010;35:940–947. doi: 10.1016/j.addbeh.2010.06.006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Quinn PD, Fromme K. Alcohol use and related problems among college students and their noncollege peers: The competing roles of personality and peer influence. Journal of Studies on Alcohol and Drugs. 2011;72:622–632. doi: 10.15288/jsad.2011.72.622. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rice KG, Van Arsdale AC. Perfectionism, perceived stress, drinking to cope, and alcohol-related problems among college students. Journal of Counseling Psychology. 2010;57:439–450. [Google Scholar]

- Rivis A, Sheeran P. Social influences and the theory of planned behaviour: Evidence for a direct relationship between prototypes and young peoples exercise behaviour. Psychology & Health. 2003;18:567–583. [Google Scholar]

- Sher KJ, Rutledge PC. Heavy drinking across the transition to college: Predicting first-semester heavy drinking from precollege variables. Addictive Behaviors. 2007;32:819–835. doi: 10.1016/j.addbeh.2006.06.024. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shiffman S. Ecological momentary assessment (EMA) in studies of substance use. Psychological Assessment. 2009;21:486–497. doi: 10.1037/a0017074. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Simons JS, Gaher RM, Oliver MNI, Bush JA, Palmer MA. An experience sampling study of associations between affect and alcohol use and problems among college students. Journal of Studies on Alcohol. 2005;66:459–469. doi: 10.15288/jsa.2005.66.459. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Slater MD. Personal value of alcohol use as a predictor of intention to decrease post-college alcohol use. Journal of Drug Education. 2001;31:263–269. doi: 10.2190/V8Q4-7M7C-Y1Y0-AV59. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Treloar HR, Morris DH, Pedersen SL, McCarthy DM. Direct and indirect effects of impulsivity traits on drinking and driving in young adults. Journal of Studies on Alcohol and Drugs. 2012;73:794–803. doi: 10.15288/jsad.2012.73.794. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Turrisi R, Mastroleo NR, Mallett KA, Larimer ME, Kilmer JR. Examination of the mediational influences of peer norms, environmental influences, and parent communications on heavy drinking in athletes and nonathletes. Psychology of Addictive Behaviors. 2007;21:453–461. doi: 10.1037/0893-164X.21.4.453. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Watt M, Stewart S, Birch C, Bernier D. Brief CBT for high anxiety sensitivity decreases drinking problems, relief alcohol outcome expectancies, and conformity drinking motives: Evidence from a randomized controlled trial. Journal of Mental Health. 2006;15:683–695. [Google Scholar]

- Wechsler H, Nelson TE, Lee JE, Seibring M, Lewis C, Keeling RP. Perception and reality: A national evaluation of social norms marketing interventions to reduce college students’ heavy alcohol use. Journal of Studies on Alcohol. 2003;64:484–494. doi: 10.15288/jsa.2003.64.484. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Woicik PA, Stewart SH, Pihl RO, Conrod PJ. The Substance Use Risk Profile Scale: A scale measuring traits linked to reinforcement-specific substance-use profiles. Addictive Behaviors. 2009;34:1042–1055. doi: 10.1016/j.addbeh.2009.07.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yarnal C, Qian X, Hustad JTP, Sims D. Intervention for positive use of college student leisure time. Journal of College and Character. 2013;14:171–176. doi: 10.1515/jcc-2013-0022. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zuckerman M. Behavioral expressions and biosocial bases of sensation seeking. Cambridge, UK: Cambridge University Press; 1994. [Google Scholar]

- Zuckerman M. Sensation seeking and risky behavior. Washington, DC: American Psychological Association; 2007. [Google Scholar]