Abstract

Objective

To compare the effects of both dietary fatty acid composition and exercise vs. sedentary conditions on circulating levels of hunger and satiety hormones. Eight healthy males were randomized in a 2×2 crossover design. The four treatments were 3 days of HF diets (50% of energy) containing high saturated fat (22% of energy) with exercise (SE) or sedentary (SS) conditions, and high monounsaturated fat (30% of energy) with exercise (UE) or sedentary (US) conditions. Cycling exercise was completed at 45% of VO2max for 2h daily. On the third HF day, 20 blood specimens were drawn over a 24h period for each hormone (leptin, insulin, ghrelin, and peptide YY (PYY)). A visual analog scale (VAS) was completed hourly between 0800 and 2200. Average 24h leptin and insulin levels were lower while 24h PYY was higher during exercise vs sedentary conditions. FA composition did not differentially affect 24h hormone values. VAS scores for hunger and fullness did not differ between any treatment but did correlate with ghrelin, leptin, and insulin. High saturated or unsaturated fat diets did not differ with respect to markers of hunger or satiety. Exercise decreased 24h leptin and insulin while increasing PYY regardless of FA composition.

Keywords: Satiety, Dietary Fat, Exercise, Hormones

Introduction

The prevalence of obesity in the U.S. continues to be a public health concern with roughly two-thirds of the adult population being classified as overweight and 31% obese (Ogden et al., 2006). Obesity is associated with hypertension, dyslipidemia, cardiovascular disease, stroke, diabetes mellitus, musculoskeletal disorders, certain cancers and an increased risk of disability, and thus obese individuals have an increased risk for morbidity and mortality (Bogers et al., 2007; Vongpatanasin, 2007). The rapid rise in obesity over past decades indicates important environmental influences, two of which are total caloric intake and level of physical activity.

During the past fifteen years, research into the mechanisms of hunger and satiety has identified numerous circulating hormones that control hunger and satiety and thus act to regulate total caloric intake and body weight (Druce et al., 2004). These include ghrelin, leptin, insulin, and Peptide YY (PYY). The main region of the brain involved in hunger and satiety control are the hypothalamus, in particular the arcuate nucleus (ARC), and the dorsal vagal complex in the brain stem (Kalra et al., 1999; Schwartz et al., 2000). Within the ARC, there are two subsets of neurons that integrate signals and influence energy homeostasis. These neurons are the neuropeptide Y (NPY)/agouti-related peptide (AgRP) neurons and the pro-opiomelanocortin (POMC)/cocaine-and amphetamine-regulated transcript (CART) neurons (Sainsbury et al., 2002). NPY and AgRP expressing neurons are orexigenic (hunger stimulating), while those expressing POMC and CART are anorexigenic (hunger suppressing) (Sainsbury et al., 2002; Schwartz et al., 2000). Ghrelin is a 28-amino acid peptide that is synthesized and secreted by the X/A-like endocrine cells in the fundus of the stomach (Wren et al., 2000). It is thought that ghrelin induces or stimulates hunger by stimulating the NPY/AgRP neurons (Nakazato et al., 2001). Plasma ghrelin levels rise during fasting conditions and decrease within one hour after nutrient intake (Cummings et al., 2001). Conversely, insulin, leptin, and PYY are thought to decrease energy intake by inducing satiety. Peptide YY is a 36-amino acid peptide belonging to the NPY family (Monteleone et al., 2005) and is secreted from the endocrine L cells of the ileum and colon in response to nutrient intake (Morinigo et al., 2006). PYY targets on the Y2 receptor which is highly expressed in NPY neurons. This binding of Y2 leads to the inhibition of food intake (Batterham et al., 2002). Leptin, which was discovered in 1994, is primarily produced and secreted by white adipose tissue, but is also released from the GI tract (Bado et al., 1998) and has been shown to inhibit food intake (Friedman & Halaas, 1998). It influences food intake and energy expenditure by inhibiting the NPY/AgRP neurons and directly stimulating the POMC/CART neurons of the ARC (Cowley et al., 2001). Insulin, which is released from pancreatic beta cells, is well known for its role in glucose homeostasis, but also acts as a satiety signal (Schwartz et al., 1992). It exerts its effects by inhibiting NPY/AgRP neurons and stimulating POMC neurons (Baskin et al., 1999; Breen et al., 2005; Sipols et al., 1995). Insulin levels are highest following nutrient intake and decrease during fasting. Together, signals for these hormones are integrated in the ARC of the hypothalamus to influence energy intake, EE, and overall energy balance.

Although the knowledge of the hormonal control of hunger and satiety has grown during the past fifteen years, an understanding of the effects of an acute high-fat (HF) diet is less well understood. We recently expanded upon our previous studies of the rate of adaptation (increasing fat oxidation to match a higher dietary fat intake) to a HF diet (Cooper et al., 2009; Cooper et al., 2010). This study was designed to test whether the fatty acid composition in the HF diet interacted with exercise to influence the rate of change in fat oxidation. In addition, we measured circulating levels of leptin, grehlin, PPY, and insulin during the HF feeding to test whether they were influenced by fatty acid composition and exercise. We investigated the fatty acid composition of the HF diet because fatty acids characteristically affect metabolism differently (Jones & Schoeller, 1988) and may have a differential influence on energy expenditure (Kien et al., 2005) and hunger and satiety hormone response. Kien et al (Kien et al., 2005) studied a high saturated versus unsaturated fat diet for 4 weeks and found increases in fat mass in those subjects on the high saturated fat diet. They concluded that one possible explanation for their results were differences in satiety in response to the high saturated fat diet which caused subjects to consume more food than those on the high unsaturated fat diet. In a different study, Poppitt et al (Poppitt et al., 2006) examined the post-prandial effects of one HF meal rich in either saturated or unsaturated FAs and found no treatment effect on ghrelin or insulin while leptin decreased regardless of FA composition. They concluded that increasing dietary saturated FAs did not negatively effect leptin or total ghrelin levels. Importantly, this study was based on a 6h post-prandial response to one HF meal. It is yet to be determined whether a HF diet, rather than one HF meal, containing primarily saturated or unsaturated FAs has a differential effect on hormones such as ghrelin, leptin, insulin, and PYY. Additionally, the impact of sub-maximal exercise on all of these hormones is not well understood and the relationship between exercise and different dietary FAs has not been previously addressed.

The purpose of this study was to examine the effects of an acute HF diet rich in saturated versus mono-unsaturated fatty acids as well as exercise on circulating levels of hunger and satiety hormones under eucaloric conditions. Based on previous studies on the fatty acid effects on metabolism and those results by Kien et al (Kien et al., 2005), we hypothesized that the high mono-unsaturated fat diet would increase satiety by increasing leptin, insulin, and PYY levels while lowering ghrelin levels compared to the high saturated fat diet. We also hypothesized that acute sub-maximal exercise would decrease 24h averages of insulin and leptin, increase PYY, and have no effect on ghrelin levels. This hypothesis was based on similar results shown in previous studies on the acute effects of aerobic exercise independent of dietary influences (Hulver & Houmard, 2003; Kraemer et al., 2004; Martins et al., 2007; Olive & Miller, 2001; Viru, 1992).

Methods

Study Design

This study was a single-blinded (participants were blinded to treatment conditions), randomized 2×2 crossover design. The four treatments were HF diets (50% of energy) containing high saturated fat (22% of energy) with exercise (SE) or sedentary (SS) conditions, and high monounsaturated fat (30% of energy) with exercise (UE) or sedentary (US) conditions. Each study visit included a 4-day lead-in diet (30% of energy from fat) followed by a 5-day, 6-consecutive night inpatient visit in a metabolic chamber at the University of Wisconsin-Madison (UW) hospital’s Clinical and Translational Research Core (CTRC). For the inpatient visits, day 1 was the same diet composition as the lead-in diet while days 2–5 were the HF diet (50% of energy from fat). For the exercise visits, cycling exercise was completed at 45% of VO2max for 2h during each day of the inpatient visits. On the fourth day of the inpatient visit (third day of the HF diet), blood was drawn hourly between 0800 and 2200 and every two hours between 2400 and 0800 for each hormone, and a visual analog scale (VAS) was completed hourly between 0800 and 2200 hours.

Subjects

Eight apparently healthy men between the ages of 18 and 45 were recruited to participate in a research study at the University of Wisconsin-Madison CTRC. This study was approved by the Institutional Review Board at UW-Madison and informed written consent was obtained from each participant. For this randomized crossover study, inclusion criteria were males between 18 and 45 years of age, BMI between 18 and 30kg/m2, and a moderately sedentary lifestyle (<3h/wk of low-to-moderate-intensity exercise and no vigorous exercise). Exclusion criteria included a history of metabolic or pulmonary disease and claustrophobia. All eight participants completed all four of the study visits.

Protocol

This was a sub-study to an investigation of the effects of energy expenditure and dietary fats on the time course of fat oxidation following a change to high fat diet (Cooper et al., 2009). The study was designed to have participants in energy balance throughout each study visit. Briefly, there were four treatment conditions and each participant completed all four treatment conditions in random order. Treatment conditions are described in the study design section above. Prior to participation in the four study visits, subjects underwent a physical exam and screening where a fasting blood sample was taken to screen for abnormal blood lipids, glucose, and insulin levels. Resting metabolic rate and VO2max were measured during screening as described elsewhere (Cooper et al., 2009). These measures were used to establish eucaloric energy intake (balance of energy intake to energy expenditure) and exercise time and intensity. For each study visit, participants stayed in a metabolic chamber at the CTRC for 5 consecutive days and 6 nights. Visits were separated by at least two weeks. On the fourth day of each visit (the third day on the high-fat (HF) diet) an intravenous catheter was placed in the antecubital space (venous cannulation) of the participant at 0800 hours and kept patent with saline. Blood draws were done hourly between 0800 and 2200 hours and every two hours between 2400 and 0800 hours on day 5. Blood was drawn into chilled EDTA tubes (Greiner Vacuette, Monroe, NC) and immediately spun at 1600 x g for 15 minutes at 4°C. Aprotinin (0.6TIU/ml, Phoenix Pharmaceuticals Inc, Burlingame, CA) was immediately added to the plasma which was aliquoted and stored at −80 degrees until assayed.

Participants also completed a 5 question visual analog scale (VAS) hunger and satiety questionnaire as previously developed (Kral et al., 2004). The questionnaire was given every hour from 0800 until 2300 hours on day 4 and again at 0800 on day 5. The 5 questions with the corresponding standard 100mm lines for each question were on one sheet of paper. After completing the 5 questions for a given hour, that sheet was removed from the remaining blank questionnaires to be completed during subsequent hours. Scales included hunger, fullness, thirst, and nausea, and how much they thought they could eat.

Diet

Prior to each study visit, participants were provided with a four-day lead-in Western diet. All meals and snacks contained roughly 55% carbohydrate (CHO), 15% protein, and exactly 30% fat. Total energy intake for the lead-in diet was based on the participant’s RMR*1.65 , which is the US average total energy expenditure in adults (Institute of Medicine of the National Academies, 2005). During the study visits, all meals were provided by the UW Hospitals and Clinics kitchen. On the first day of each visit, participants remained on the “standard” American diet consisting of 55% CHO, 15% protein, and 30% fat. On days 2 through 5, participants were either on a high saturated fat or high mono-unsaturated fat diet. Both HF diets provided 35% of energy from CHO, 15% protein, and 50% fat. For the high saturated fat treatments, 22% of total energy consumed was saturated fat, 14% was mono-unsaturated fat, and 14% poly-unsaturated fat. For the high mono-unsaturated fat treatment, 30% of total energy was mono-unsaturated fat, 10% of energy was saturated and 10% poly-unsaturated fat. Subjects received 3 meals each day (breakfast at 0830, lunch at 1200, and dinner at 1900 hours) along with two snacks (1600 and 2200 hours). Meals provided 25%, 25%, 40% (minus 50kcal), and 10% of daily energy needs for breakfast, lunch, dinner, and afternoon snack respectively. Additionally, they received a 50kcal evening snack. Total energy intake was prescribed to equal expected 24-hour energy expenditure (24hEE). An energy intake of RMR*1.35 for sedentary visits was selected based on previous observations of participants under sedentary conditions in the metabolic chamber. The caloric intake of RMR*1.8 for exercise visits was based on a study by Smith et al (Smith et al., 2000). Participants were required to eat all of the food provided to them.

Exercise

During the exercise visits, participants rode a stationary bike at 45% of their VO2max two times each day (at 1000 and 2100). The goal for the exercise visits was to raise 24hEE to the subject’s RMR*1.8. To calculate duration of exercise, the energy cost of cycling at 45% of VO2max was estimated from the individual linear equation between VO2 and work (watts) generated during each subject’s VO2 max test. Relative VO2 (ml/kg/min) at 45% of VO2 max was used to calculate the minutes of cycling needed to raise 24h EE to 1.8*RMR, and this time was split between the morning and evening sessions of exercise. The total duration of exercise for each subject was approximately 2 hours per day (1 hour in the morning and 1 hour in the evening).

Assays

Radioimmunoassays (RIAs) were used for all hormones assays. Plasma was assayed for total ghrelin, leptin, insulin, and PYY from all four study visits. All RIA kits used were from Linco (Millipore, Billerica, MA). Plasma samples were run in duplicate and each participant’s total number of samples were run within the same assay. The intra- and inter-assay coefficients of variation (CV) for leptin were 4.2% and 6.3% respectively while the intra- and inter-assay CV for ghrelin were 3.8% and 12.6% respectively. Intra- and inter-assay CVs for insulin were 11.3% and 13.7% respectively and the intra- and inter-assay CV for PYY were 9.8% and 15.8% respectively.

Statistical Analysis

The SAS version 8.2 statistical package (SAS Institute Inc, Cary, NC) was used for all data analysis with subjects serving as their own controls due to the randomized crossover design. A PROC MIXED analysis was performed for repeated-measures analysis to test the effects of the four different treatment groups on the dependent variables (hormones and VAS scores for hunger and fullness. Post-hoc analyses were done using a Tukey’s test. We also calculated 24-h averages to study the treatment effects. The 24-h average is the average of all values for each hormone over the 24h period. Three individual time-of-day comparisons had also been proposed a priori to preserve power: (1) the hour after dinner (2000 hours) to look for acute dietary FA composition differences, (2) the morning post-exercise period (1100 hours) and (3) the evening post-exercise period (2200 hours) to look for acute exercise effects. Pearson correlations were used to examine the relationship between subjective and hormonal measures of hunger and satiety. Values are presented as mean ± SEM unless otherwise indicated, and statistical significance was set at p < 0.05.

Results

Subjects

Eight healthy male participants completed all four study visits (Table 1). Per the eligibility criteria, all subjects were sedentary (<3h per week of low to moderate exercise) and were free from metabolic disease. Fasting blood lipids, glucose, and insulin levels were in the normal range (data not shown). Total energy intake and expenditure was recorded during every day of each study visit and have been reported elsewhere (Cooper et al., 2009). Briefly, energy balanced averaged −195±130, −208-±127, −35±125, and −26±106 kcal/d for SE, UE, SS and US, respectively.

Table 1.

SAubject Characteristics

| Mean | SD | |

|---|---|---|

| Age, y | 25 | 8 |

| Height, cm | 185 | 6 |

| Weight, kg | 76.5 | 6.5 |

| BMI, kg/m2 | 22.5 | 3.3 |

| Body fat, % | 20.3 | 2.7 |

| VO2max, mL/kg/min | 40.5 | 5.1 |

BMI, body mass index; VO2max, maximal aerobic capacity.

Hormones

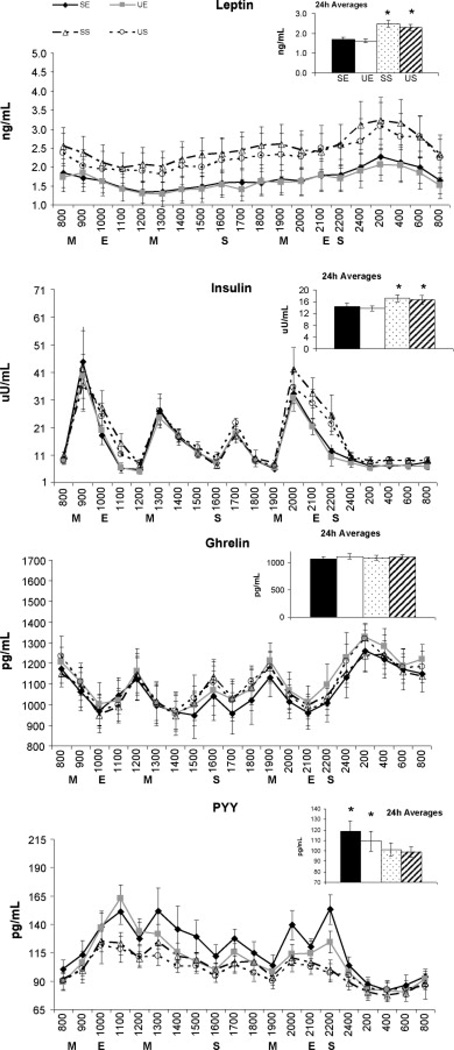

Hormone 24h profiles and the 24h mean values for each of the four treatment conditions are shown in Figure 1. For leptin, there was a main effect for treatment (p<0.001) and time (p<0.001), but no treatment*time interaction. Further analysis revealed that both exercise treatments were significantly lower than sedentary treatments with no effect of FA composition (24h averages: 1.7±0.1, 1.6±0.1, 2.5±0.2, and 2.3±0.2ng/mL for SE, UE, SS, and US, respectively). Similarly, insulin levels showed a main effect for treatment (p<0.001) and time (p<0.001), but no treatment*time interaction. Further analysis revealed that insulin during the exercise treatments were lower than during sedentary treatments, while no FA effect was detected (24h averages:14.4±4.7, 13.7±4.3, 17.3±4.9, 16.7±4.7µU/mL for SE, UE, SS, and US, respectively). Analysis of ghrelin profiles revealed a main effect for time (p<0.001), but no treatment effect or treatment*time interaction. Finally, the PYY 24h profile revealed a main effect for treatment (p<0.001) and time (p<0.001), but no interactions. Further analysis of the treatment effect showed that both exercise treatments were significantly greater than sedentary treatments (24h averages: 118±10, 109±9, 101±6, and 99±5pg/µL for SE, UE, SS, and US, respectively).

Figure 1.

24h hormone profiles and 24h averages of each hormone for all four treatment conditions. Analysis between the four treatment conditions done using a repeated measures ANOVA. Data presented as Mean ± SEM. A priori comparisons showed insulin levels to be lower in both post-exercise periods (p=0.03) and the hour after dinner for SE and UE vs SS treatments (p=0.04). Additionally, PYY levels were higher in both post-exercise periods for exercise compared to sedentary treatments (p=0.01). Finally, the SE treatment led to higher PYY levels the hour after dinner (p=0.01) and was also higher than the UE treatment following evening exercise (p=0.01). For 24h averages, exercise compared to sedentary conditions led to significantly lower 24h averages for leptin (p<0.001) and insulin (p<0.001) but a higher 24h averages for PYY (p<0.001). No differences in dietary fatty acid composition existed. M, meal; E, exercise; S, snack; SE, High saturated fat diet + exercise; UE, High mono-unsaturated fat diet + exercise; SS, High saturated fat diet + sedentary; US, High mono-unsaturated fat diet + sedentary. * indicates significant treatment differences

For the three time-of-day comparisons that had been proposed a priori to test for acute exercise or dietary effects, neither ghrelin nor leptin showed differences between treatments for the three time-points. For insulin, the morning post-exercise time-point resulted in both exercise treatments being significantly lower than the SS treatment (6.0±1.7 (p=0.03) and 6.2±1.8 (p=0.03) vs 15.3±3.5 µU/mL for SE and UE vs SS, respectively). A difference was also found one hour after dinner (33.2±5.5 (p=0.04) and 31.7±4.7 (p=0.01) vs 42.2±7.7 µU/mL for SE and UE vs SS, respectively). The US treatment was not significantly different from any other treatment condition. Following evening exercise, both sedentary treatments had significantly higher insulin levels compared to the two exercise treatments (12.3±2.7 and 10.2±3.3 vs 25.6±7.1 (p<0.01, p<0.001) and 22.2±2.6µU/mL (p=0.02, p=0.03) for SE and UE vs SS and US, respectively). Conversely, for PYY, the morning post-exercise time was significantly greater for both exercise compared to sedentary conditions (151±11 and 163±12 vs 123±10 (p=0.01, p<0.001) and 118±11pg/mL (p<0.001, p<0.001) for SE and UE vs SS and US, respectively). The hour after dinner showed the SE treatment had significantly higher PYY values than the other 3 conditions (139±13 vs 113±9 (p=0.01), 110±6 (p=0.01), and 106±9pg/mL (p<0.01) SE vs UE, SS, and US, respectively). Finally, the evening post-exercise time showed the same effect as morning exercise (153±13 and 124±10 vs 100±9 (p<0.001, p+0.01) and 97±8pg/mL (p=0.01, p=0.01) for SE and UE vs SS and US, respectively) with the one exception of the SE treatment also being significantly higher than the UE treatment (153±13 vs 124±10pg/mL, p=0.01).

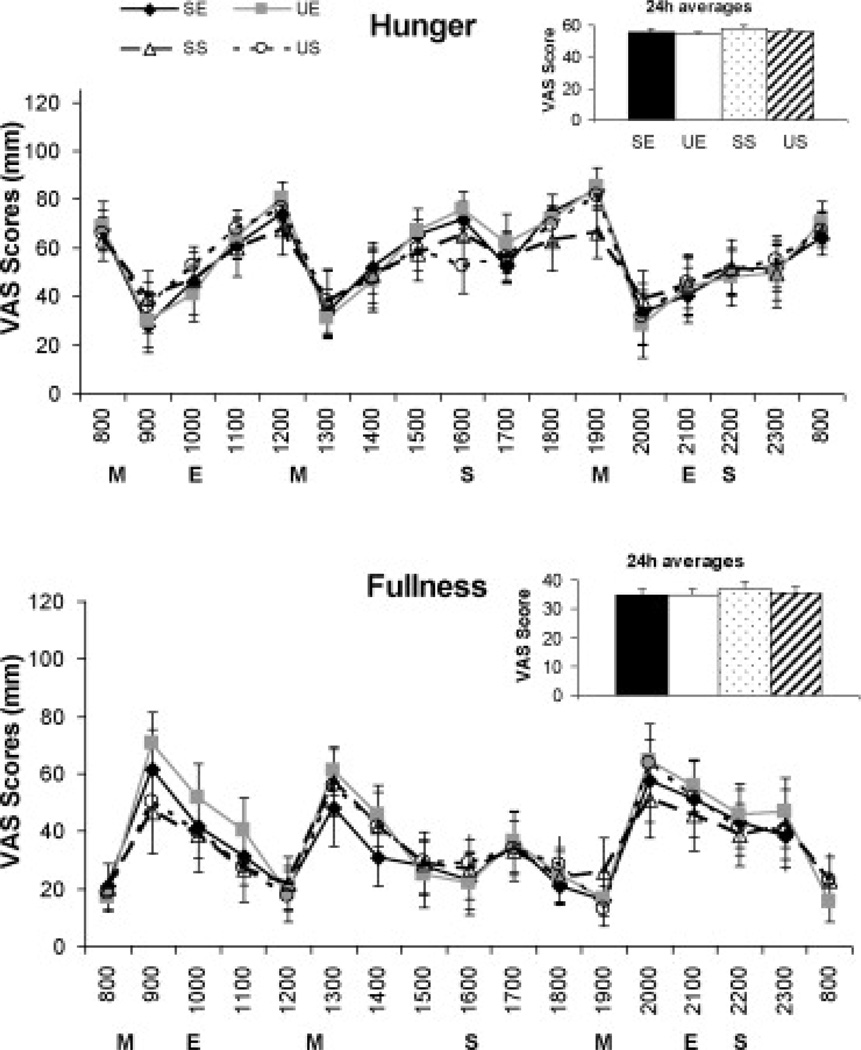

Visual Analog Scale (VAS)

The hourly profiles for subjective VAS measures of hunger and fullness as well as 24h mean values are shown in Figure 2. For perceived hunger, there was a main effect of time (p<0.001), but no treatment effect or treatment*time interaction. Similarly, comparison of feelings of fullness between the four treatments revealed a main effect for time (p<0.001), but no treatment or interaction effect. No significant differences were detected between any of the four treatment conditions for each question on nausea (3.8±2.7, 2.8±2.7, 4.1±3.3, and 2.9±4.3mm for SE, UE, SS, and US, respectively), thirst (22.4±9.1, 24±8.6, 19.2±8.1, and 20.4±7.6mm for SE, UE, SS, and US, respectively), and how much they thought they could eat (64.2±9.6, 64.5±11.1, 63.2±11.2, and 61±11.6mm for SE, UE, SS, and US, respectively).

Figure 2.

Hourly visual analog scale (VAS) scores and 2h hour average VAS scores for subjective measures of hunger and fullness on Day 4 (third day of HF diet) for each of the four treatment conditions. Analysis between the four treatment conditions done using a repeated measures ANOVA. Data presented as Mean ± SEM. No treatment or time effects were detected. M, meal; E, exercise; S, snack; SE, High saturated fat diet + exercise; UE, High mono-unsaturated fat diet + exercise; SS, High saturated fat diet + sedentary; US, High mono-unsaturated fat diet + sedentary.

Correlations

We assessed relationships between hormonal measures and VAS measures of hunger and satiety using within subject comparisons for each treatment condition (Table 2). Only the hours containing both VAS scores and hormone measures were included. The correlations were very similar across treatments (no statistical differences due to treatment condition) and we therefore collapsed the treatments together and performed the correlations using treatment as a covariate. Treatment was not significant when this was done. VAS hunger scores showed significant positive correlations with ghrelin and negative correlations with leptin and insulin. Interestingly, no correlation between PYY and hunger scores was detected. VAS fullness scores were significantly positively correlated with leptin and insulin for all treatments and were negatively correlated with ghrelin. Once again, PYY did not correlate with VAS fullness scores. Finally, we ran correlations between each of the four hormones measured. Many significant correlations, both positive and negative, were detected between the hormones. The largest correlation was between leptin and ghrelin (r = −0.33, p<0.001).

Table 2.

Correlation matrix between visual analog scale measures of hunger and fullness and hormone levels. Correlations are presented with all treatment conditions combined.

| Hunger | Fullness | Leptin | Insulin | Ghrelin | PYY | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Hunger | 1.0 | −0.71* (p<0.001) |

−0.37* <0.001 |

−0.43* −0.001 |

0.30* 0.008 |

−0.01 0.84 |

| Fullness | 1.0 | 0.32* <0.001 |

0.41* <0.001 |

−0.30* <0.001 |

−0.01 0.94 |

|

| Leptin | 1.0 | 0.18* <0.001 |

−0.33* <0.001 |

−0.03 0.43 |

||

| Insulin | 1.0 | −0.25* <0.001 |

0.12* 0.001 |

|||

| Ghrelin | 1.0 | −0.18* <0.001 |

||||

| PYY | 1.0 |

Top number represents correlation coefficient and bottom number represents p values.

Significance at p = 0.05.

Discussion

While many investigators have studied the effects of various compositions of total fat in a meal or diet, this is one of the few to investigate dietary FA composition from a HF diet. Other unique aspects of this study include studying the effects of aerobic exercise in conjunction with the different HF diets, measuring hormones over a 24h period, having both physiological and subjective measures of hunger and satiety, and looking at HF diets rather than a single HF meal. We found that acute HF diets rich in either mono-unsaturated or saturated FAs did not differentially affect hunger or satiety as determined by mean 24h hormone values for ghrelin, leptin, insulin, and PYY. The only dietary FA effects detected were higher PYY values for the SE treatment compared to the UE treatment following the evening meal. Aerobic exercise, regardless of dietary FA composition, led to increases in 24h measures of PYY, decreases in leptin and insulin, and no changes in ghrelin.

The ratio of unsaturated fats to saturated fats in the diet has been shown to influence other energy metabolism parameters, including energy substrate utilization (Jones & Schoeller, 1988) and post-prandial energy expenditure (Jones et al., 2008) in humans. Therefore, it has been suggested that dietary FA composition may differentially affect satiety (Jones & Schoeller, 1988; Piers et al., 2002). We did not, however, find an effect of dietary FA composition from a HF diet on VAS measures of hunger and fullness. Although we had a relatively small number of subjects in this study, the largest mean differences in VAS scores was 3mm. Our findings are consistent with previous studies which have shown that dietary FA composition did not differentially affect subjective measures hunger and fullness (Alfenas & Mattes, 2003; Flint et al., 2003; Kamphuis et al., 2001; Lawton et al., 2000; MacIntosh et al., 2003). Not all research supports our study results though (Lawton et al., 2000; Maljaars et al., 2009). For example, Maljaars et al (Maljaars et al., 2009) did find that fullness scores were significantly increased in a MUFA- and PUFA-rich fat infusions following liquid meal ingestion compared to the SFA-rich fat infusion. Our study, however, went beyond the previous studies by including 24h profiles of the hunger and satiety hormones (leptin, ghrelin, insulin, and PYY), in addition to VAS scores. Measuring the 24h profiles of hunger and satiety hormones in general is important because energy intake is distributed across the day. This is particularly true for leptin and insulin, which are thought to be long-term regulators of energy intake. 24h profiles can provide information that fasting levels and single meal responses may miss. We feel this is especially true for protocols that are designed to keep subjects in energy balance over the course of a 24h period. Studying 24h profiles allows for examination of hormone levels between meals as well as during the night. To take advantage of the additional sampling, we investigated individual time points as well in order to address acute effects of meals and exercise for the short-term hormone responses.

The absence of FA treatment effects in our study strengthens results from previous single meal studies. Poppitt et al (Poppitt et al., 2006) measured the post-prandial effects following a single HF meal rich in either saturated or unsaturated FAs on hunger and satiety hormones in 18 healthy subjects and found no treatment effect on ghrelin, insulin, or leptin levels. Our lack of difference in 24h PYY levels in response to dietary FA composition is also in agreement with Maljaars et al (Maljaars et al., 2009) who reported no differences in PYY levels between unsaturated or saturated FAs following ileal infusions of fat emulsions in 15 human subjects. Based on our results and previous observations, it appears that in humans, acute diets rich in either mono-unsaturated or saturated FAs do not differentially affect ghrelin, leptin, insulin, or PYY levels over a 24h period and therefore may not differentially affect hunger or satiety during treatments of one meal to three days. Interestingly, one study lasting 6-weeks on HF diets (60% of energy), showed that a high mono-unsaturated fat diet lowered leptin concentrations compared to a high saturated fat diet in rats (Stachon et al., 2006). Thus, there may be potential for dietary FA composition to affect hormones after longer treatments in humans. To detect a treatment effect in our study with regard to dietary FA composition, the difference would have needed to be 20pg/µL for PYY, 150pg/mL for ghrelin, 15µU/mL for insulin, and 0.5ng/mL for leptin.

Aerobic exercise increases energy expenditure (EE) and could be important for weight loss or obesity prevention, however, the increased EE from exercise will result in fat loss only when the calories expended are not completely compensated for by increased energy intake. Therefore, investigating the effects of exercise on markers of hunger and satiety is important for understanding energy balance. Further, since exercise influences metabolic responses to a HF diet, we hypothesized that it may influence circulating hunger and satiety hormone levels as well. We found that exercise compared to sedentary conditions during a HF diet, regardless of dietary FA composition, increased 24h PYY levels, decreased 24h leptin and insulin levels, and had no effect on ghrelin. It is possible that the opposing directions of the satiety hormones responses negated one another and, therefore, exercise may not significantly alter satiety. Interestingly, acute exercise effects were detected as morning and evening post-exercise PYY was higher and insulin lower compared to sedentary conditions. Our 24 hormone profiles expand on the findings of others who investigated exercise effects for a few hours post-exercise. (Hulver & Houmard, 2003; Kraemer et al., 2004; Martins et al., 2007; Olive & Miller, 2001; Viru, 1992). Ghrelin has repeatedly been shown not to respond to aerobic exercise (Borer et al., 2005; Kraemer et al., 2004), while PYY was recently shown to increase in response to acute exercise (Martins et al., 2007). Similarly, insulin levels have been shown to decrease in response to acute exercise with greater decreases observed in higher intensity exercise (Viru, 1992). Finally, leptin concentrations in response to single bouts of exercise have produced varying results. These previous studies suggest that the key for decreasing leptin concentrations in response to exercise is a high volume of exercise (~800kcals needed) (Hulver & Houmard, 2003). Interestingly, if feeding occurs, this decrease is ablated (Koistinen et al., 1998). Each of our exercise bouts were of lower volume than 800 kcal and thus insufficient to acutely decrease leptin levels; however, our exercise treatment did cause all time-points throughout the 24h period to be lower than sedentary conditions. This provides further implications for a long-term role of leptin in energy balance regulation as large fluctuations during the day do not occur.

An important question related to the effects of exercise is whether it is the actual exercise bout that alters metabolism or hormone levels, or whether it is the energy deficit or weight loss that stems from exercise that elicits these effects. Unless studies compensate for energy expended during acute exercise, changes in satiety hormones that occur with an exercise intervention can be attributed to either the exercise bout or changes in energy balance. This is especially true for leptin because leptin is thought to elicit more long-term control over energy balance. To this end, Thong et al (Thong et al., 2000) studied whether 6 months of exercise induced weight loss would differentially affect leptin levels when compared to diet induced weight loss. In both instances, leptin levels decreased in proportion to decreases in body weight and no differences were found between the methods of weight loss. They concluded that exercise training, independent of weight loss, did not affect circulating leptin levels. Thong et al (Thong et al., 2000), however, instructed their subjects to abstain from strenuous exercise and consume an energy maintenance diet for three days prior to the post-weight loss measures of leptin after and overnight fast. These results are different than those observed in our study where we did show decreases in 24h measures of leptin concentrations suggesting that the decrease in leptin levels that we observed were due to the acute effects of exercise.

A limitation of our study is that we chose to investigate only four hunger and satiety hormones; two of which are considered to have short-term (meal-to-meal) control and two of which have both short-term and long-term (day-to-day) roles in the regulation of energy balance. There are however other hunger and satiety hormones that impact energy intake including CCK, GLP-1, and oxyntomodulin (Badman & Flier, 2005). Therefore, when considering the total impact of exercise and/or composition of nutrients in the diet, it is important to keep in mind that there are multiple hormones that acutely suppress (or stimulate) food intake and that the integration of these signals influence overall energy balance in a manner that is not yet fully understood. Our study provides some initial results on how these four hormones respond to aerobic exercise and fatty acid composition of the diets while maintaining energy balance. Although we found little evidence of a fatty acid influence, exercise did have an influence. Our study only addressed the role of exercise under conditions of energy balance. More research is clearly needed to determine the role of exercise on influencing hunger and satiety responses under a wider array of energy intakes.

We also investigated whether the hunger and satiety hormonal responses translated to perceived, subjective feelings of hunger or fullness using a VAS. Because we did not detect any dietary FA effect on hunger and satiety hormones levels, with the exception of the time-points following the evening meal and evening exercise in PYY, it is not surprising that subjective feelings of hunger and fullness from the VAS did not show a dietary FA effect. Our 24h data is similar to post-prandial measures from Casas-Agustench et al (Casas-Agustench et al., 2009) who also reported no differences in satiety measures between meals rich in mono- or poly-unsaturated fat and saturated fats. Interestingly, although we did see exercise treatment effects on 24h insulin, leptin, and PYY hormone levels, VAS scores also did not show a treatment effect for exercise vs. sedentary conditions. This is important because we did detect significant correlations between VAS scores and all of the hormones with the exception of PYY. These results suggest that local changes may influence perceived hunger and/or fullness independently of the mean level. To this end, we did test whether there were correlations between the hourly rhythms of the hormone levels and the VAS scores, but no significant correlations were observed under the conditions of our study (data not shown). It is also possible that as long as individuals remain in energy balance, as was our experimental design, changes in hormone levels in response to exercise may not affect overall perceived hunger or fullness. Finally, when studying subjective data, it is important to consider the power of the study to detect a significant difference should one exist. Our treatment differences were relatively small (the largest mean difference was 3mm). Based on these small group differences with the VAS data, we would have needed a sample size of 101 to detect a statistically significant, but clinically minor, difference.

Although the study was designed to maintain energy balance, out ability to do so was not perfect. We predicted 24EE based on RMR and minutes of prescribed exercise and designed the diet to match that value rather than the potentially more precise matching intake to expenditure based on real time calculations of expenditure while the subjects were in the metabolic chamber. Despite this, our errors in attaining energy balance were small (Cooper et al., 2009) and comparable to those in other studies (Hansen et al., 2007). Because of the unintended negative energy balance under exercise conditions, we cannot rule out that the energy balance difference between exercise and sedentary conditions was a possible explanation for treatment differences with some of the hormones, especially leptin. It is impossible to determine whether the lower leptin levels found throughout a 24h period during both exercise treatments was due to the negative energy balance, exercise, or a combination of the two. Of note, however, the imbalance in exercise was small relative to the physical activity EE which were 960kcal and 940kcal for SE and UE treatments, respectively. Additional limitations to our study are the relatively small number of subjects and the limited age and BMI range, namely young, healthy males.

Our data indicate that dietary FA composition from an acute HF diet does not differentially affect either hormonal or subjective measures of hunger and satiety over a 24h period under conditions of energy balance. Exercise, however, was associated with changes in 24h values of PYY, insulin, and leptin, albeit in opposing directions. While these results are of interest, additional studies of longer duration, differing degrees of energy imbalance, and differing changes in body composition are needed to better understand the overall role of aerobic exercise is with regard to hunger and satiety. Finally, despite a lack of differences in 24h averages of subjective measures of hunger and fullness, the VAS scores did correlate with insulin, ghrelin, and leptin, but not PYY.

Acknowledgements

We thank the staff at the CTRC for the time and effort they contributed to this study.

Grants: This study was supported in part by NIH grants DK30031 and T32 DK007665, and 1UL1RR025011.

References

- Alfenas RC, Mattes RD. Effect of fat sources on satiety. Obes.Res. 2003;11:183–187. doi: 10.1038/oby.2003.29. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Badman MK, Flier JS. The gut and energy balance: visceral allies in the obesity wars. Science. 2005;307:1909–1914. doi: 10.1126/science.1109951. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bado A, Levasseur S, Attoub S, Kermorgant S, Laigneau JP, Bortoluzzi MN, et al. The stomach is a source of leptin. Nature. 1998;394:790–793. doi: 10.1038/29547. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Baskin DG, Figlewicz LD, Seeley RJ, Woods SC, Porte D, Jr, Schwartz MW. Insulin and leptin: dual adiposity signals to the brain for the regulation of food intake and body weight. Brain Res. 1999;848:114–123. doi: 10.1016/s0006-8993(99)01974-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Batterham RL, Cowley MA, Small CJ, Herzog H, Cohen MA, Dakin CL, et al. Gut hormone PYY(3–36) physiologically inhibits food intake. Nature. 2002;418:650–654. doi: 10.1038/nature00887. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bogers RP, Bemelmans WJ, Hoogenveen RT, Boshuizen HC, Woodward M, Knekt P, et al. Association of overweight with increased risk of coronary heart disease partly independent of blood pressure and cholesterol levels: a meta-analysis of 21 cohort studies including more than 300 000 persons. Arch.Intern.Med. 2007;167:1720–1728. doi: 10.1001/archinte.167.16.1720. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Borer KT, Wuorinen E, Chao C, Burant C. Exercise energy expenditure is not consciously detected due to oro-gastric, not metabolic, basis of hunger sensation. Appetite. 2005;45:177–181. doi: 10.1016/j.appet.2005.01.012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Breen TL, Conwell IM, Wardlaw SL. Effects of fasting, leptin, and insulin on AGRP and POMC peptide release in the hypothalamus. Brain Res. 2005;1032:141–148. doi: 10.1016/j.brainres.2004.11.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Casas-Agustench P, Lopez-Uriarte P, Bullo M, Ros E, Gomez-Flores A, Salas-Salvado J. Acute effects of three high-fat meals with different fat saturations on energy expenditure, substrate oxidation and satiety. Clin.Nutr. 2009;28:39–45. doi: 10.1016/j.clnu.2008.10.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cooper JA, Watras AC, Adams AK, Schoeller DA. Effects of dietary fatty acid composition on 24-h energy expenditure and chronic disease risk factors in men. Am.J Clin.Nutr. 2009;89:1350–1356. doi: 10.3945/ajcn.2008.27419. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cooper JA, Watras AC, Shriver T, Adams AK, Schoeller DA. Influence of Dietary Fatty Acid Composition and Exercise on Changes in Fat Oxidation from a High-Fat Diet. J.Appl.Physiol. 2010 doi: 10.1152/japplphysiol.01025.2009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cowley MA, Smart JL, Rubinstein M, Cerdan MG, Diano S, Horvath TL, et al. Leptin activates anorexigenic POMC neurons through a neural network in the arcuate nucleus. Nature. 2001;411:480–484. doi: 10.1038/35078085. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cummings DE, Purnell JQ, Frayo RS, Schmidova K, Wisse BE, Weigle DS. A preprandial rise in plasma ghrelin levels suggests a role in meal initiation in humans. Diabetes. 2001;50:1714–1719. doi: 10.2337/diabetes.50.8.1714. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Druce MR, Small CJ, Bloom SR. Minireview: Gut peptides regulating satiety. Endocrinology. 2004;145:2660–2665. doi: 10.1210/en.2004-0089. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Flint A, Helt B, Raben A, Toubro S, Astrup A. Effects of different dietary fat types on postprandial appetite and energy expenditure. Obes.Res. 2003;11:1449–1455. doi: 10.1038/oby.2003.194. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Friedman JM, Halaas JL. Leptin and the regulation of body weight in mammals. Nature. 1998;395:763–770. doi: 10.1038/27376. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hansen KC, Zhang Z, Gomez T, Adams AK, Schoeller DA. Exercise increases the proportion of fat utilization during short-term consumption of a high-fat diet. Am.J.Clin.Nutr. 2007;85:109–116. doi: 10.1093/ajcn/85.1.109. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hulver MW, Houmard JA. Plasma leptin and exercise: recent findings. Sports Med. 2003;33:473–482. doi: 10.2165/00007256-200333070-00001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Institute of Medicine of the National Academies. Dietary Reference Intakes for Energy, Carbohydrate, Fiber, Fat, Fatty Acids, Cholesterol, Protein, and Amino Acids. The National Academies Press; 2005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jones PJ, Jew S, AbuMweis S. The effect of dietary oleic, linoleic, and linolenic acids on fat oxidation and energy expenditure in healthy men. Metabolism. 2008;57:1198–1203. doi: 10.1016/j.metabol.2008.04.012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jones PJ, Schoeller DA. Polyunsaturated:saturated ratio of diet fat influences energy substrate utilization in the human. Metabolism. 1988;37:145–151. doi: 10.1016/s0026-0495(98)90009-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kalra SP, Dube MG, Pu S, Xu B, Horvath TL, Kalra PS. Interacting appetite-regulating pathways in the hypothalamic regulation of body weight. Endocr.Rev. 1999;20:68–100. doi: 10.1210/edrv.20.1.0357. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kamphuis MM, Westerterp-Plantenga MS, Saris WH. Fat-specific satiety in humans for fat high in linoleic acid vs fat high in oleic acid. Eur.J.Clin.Nutr. 2001;55:499–508. doi: 10.1038/sj.ejcn.1601222. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kien CL, Bunn JY, Ugrasbul F. Increasing dietary palmitic acid decreases fat oxidation and daily energy expenditure. Am.J.Clin.Nutr. 2005;82:320–326. doi: 10.1093/ajcn.82.2.320. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Koistinen HA, Tuominen JA, Ebeling P, Heiman ML, Stephens TW, Koivisto VA. The effect of exercise on leptin concentration in healthy men and in type 1 diabetic patients. Med.Sci Sports Exerc. 1998;30:805–810. doi: 10.1097/00005768-199806000-00005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kraemer RR, Durand RJ, Acevedo EO, Johnson LG, Kraemer GR, Hebert EP, et al. Rigorous running increases growth hormone and insulin-like growth factor-I without altering ghrelin. Exp.Biol.Med.(Maywood.) 2004;229:240–246. doi: 10.1177/153537020422900304. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kral TV, Roe LS, Rolls BJ. Combined effects of energy density and portion size on energy intake in women. Am.J Clin.Nutr. 2004;79:962–968. doi: 10.1093/ajcn/79.6.962. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lawton CL, Delargy HJ, Brockman J, Smith FC, Blundell JE. The degree of saturation of fatty acids influences post-ingestive satiety. Br.J.Nutr. 2000;83:473–482. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- MacIntosh CG, Holt SH, Brand-Miller JC. The degree of fat saturation does not alter glycemic, insulinemic or satiety responses to a starchy staple in healthy men. J.Nutr. 2003;133:2577–2580. doi: 10.1093/jn/133.8.2577. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Maljaars J, Romeyn EA, Haddeman E, Peters HP, Masclee AA. Effect of fat saturation on satiety, hormone release, and food intake. Am.J Clin.Nutr. 2009;89:1019–1024. doi: 10.3945/ajcn.2008.27335. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Martins C, Morgan LM, Bloom SR, Robertson MD. Effects of exercise on gut peptides, energy intake and appetite. J Endocrinol. 2007;193:251–258. doi: 10.1677/JOE-06-0030. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Monteleone P, Martiadis V, Rigamonti AE, Fabrazzo M, Giordani C, Muller EE, et al. Investigation of peptide YY and ghrelin responses to a test meal in bulimia nervosa. Biol.Psychiatry. 2005;57:926–931. doi: 10.1016/j.biopsych.2005.01.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Morinigo R, Moize V, Musri M, Lacy AM, Navarro S, Marin JL, et al. Glucagon-like peptide-1, peptide YY, hunger, and satiety after gastric bypass surgery in morbidly obese subjects. J Clin.Endocrinol.Metab. 2006;91:1735–1740. doi: 10.1210/jc.2005-0904. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nakazato M, Murakami N, Date Y, Kojima M, Matsuo H, Kangawa K, et al. A role for ghrelin in the central regulation of feeding. Nature. 2001;409:194–198. doi: 10.1038/35051587. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ogden CL, Carroll MD, Curtin LR, McDowell MA, Tabak CJ, Flegal KM. Prevalence of overweight and obesity in the United States, 1999–2004. JAMA. 2006;295:1549–1555. doi: 10.1001/jama.295.13.1549. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Olive JL, Miller GD. Differential effects of maximal- and moderate-intensity runs on plasma leptin in healthy trained subjects. Nutrition. 2001;17:365–369. doi: 10.1016/s0899-9007(01)00522-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Piers LS, Walker KZ, Stoney RM, Soares MJ, O'Dea K. The influence of the type of dietary fat on postprandial fat oxidation rates: monounsaturated (olive oil) vs saturated fat (cream) Int.J Obes.Relat Metab Disord. 2002;26:814–821. doi: 10.1038/sj.ijo.0801993. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Poppitt SD, Leahy FE, Keogh GF, Wang Y, Mulvey TB, Stojkovic M, et al. Effect of high-fat meals and fatty acid saturation on postprandial levels of the hormones ghrelin and leptin in healthy men. Eur.J Clin.Nutr. 2006;60:77–84. doi: 10.1038/sj.ejcn.1602270. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sainsbury A, Cooney GJ, Herzog H. Hypothalamic regulation of energy homeostasis. Best.Pract.Res.Clin.Endocrinol Metab. 2002;16:623–637. doi: 10.1053/beem.2002.0230. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schwartz MW, Figlewicz DP, Baskin DG, Woods SC, Porte D., Jr Insulin in the brain: a hormonal regulator of energy balance. Endocr.Rev. 1992;13:387–414. doi: 10.1210/edrv-13-3-387. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schwartz MW, Woods SC, Porte D, Jr, Seeley RJ, Baskin DG. Central nervous system control of food intake. Nature. 2000;404:661–671. doi: 10.1038/35007534. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sipols AJ, Baskin DG, Schwartz MW. Effect of intracerebroventricular insulin infusion on diabetic hyperphagia and hypothalamic neuropeptide gene expression. Diabetes. 1995;44:147–151. doi: 10.2337/diab.44.2.147. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Smith SR, de JL, Zachwieja JJ, Roy H, Nguyen T, Rood J, et al. Concurrent physical activity increases fat oxidation during the shift to a high-fat diet. Am.J Clin.Nutr. 2000;72:131–138. doi: 10.1093/ajcn/72.1.131. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stachon M, Furstenberg E, Gromadzka-Ostrowska J. Effects of high-fat diets on body composition, hypothalamus NPY, and plasma leptin and corticosterone levels in rats. Endocrine. 2006;30:69–74. doi: 10.1385/ENDO:30:1:69. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Thong FS, Hudson R, Ross R, Janssen I, Graham TE. Plasma leptin in moderately obese men: independent effects of weight loss and aerobic exercise. Am.J.Physiol.Endocrinol.Metab. 2000;279:E307–E313. doi: 10.1152/ajpendo.2000.279.2.E307. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Viru A. Plasma hormones and physical exercise. Int.J Sports Med. 1992;13:201–209. doi: 10.1055/s-2007-1021254. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vongpatanasin W. Cardiovascular morbidity and mortality in high-risk populations: epidemiology and opportunities for risk reduction. J.Clin.Hypertens.(Greenwich.) 2007;9:11–15. doi: 10.1111/j.1524-6175.2007.07722.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wren AM, Small CJ, Ward HL, Murphy KG, Dakin CL, Taheri S, et al. The novel hypothalamic peptide ghrelin stimulates food intake and growth hormone secretion. Endocrinology. 2000;141:4325–4328. doi: 10.1210/endo.141.11.7873. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]