Abstract

We recently encountered three patients with episodes of syncope associated with food ingestion. A 31-year-old woman had an episode of syncope in the hospital while drinking soda. Transient asystole was noted on the telemonitor, confirming the diagnosis of swallow syncope. The other two patients were 78- and 80 year old gentlemen, respectively, who presented with recurrent and transient episodes of dizziness during deglutition. Extensive work-up of syncope was negative in both cases and a diagnosis of swallow syncope was made by clinical criteria. These cases illustrate the challenging problem of swallow syncope. The diagnosis can be suspected on the basis of clinical presentation and confirmed with the demonstration of transient brady-arrhythmia during deglutition. Medical management includes avoiding trigger foods, use of anticholinergics, and/or placement of a permanent cardiac pacemaker.

Keywords: Diagnosis, Presyncope, Swallow, Symptoms, Syncope, Treatment

Syncope is a common presenting complaint that accounts for 1.5% of all emergency room admissions and 6% of all hospital admissions.[1] However, the underlying etiology often times remains elusive. Recently, we encountered three patients with syncope associated with swallowing.

CASE REPORTS

Case 1

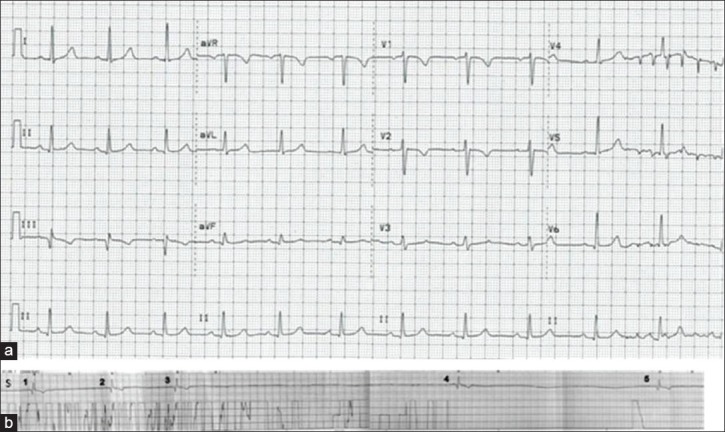

A 31-year-old obstetrics resident came to the emergency room after having an episode of syncope while drinking an aerated beverage. She suddenly felt that something was “stuck in her chest” followed by lightheadedness and sudden loss of consciousness. She recovered completely within several seconds. Interestingly, she had a similar episode while drinking soda, 3 weeks earlier. Her physical examination was unremarkable. Her electrocardiogram (EKG) [Figure 1], echocardiogram, computed tomography (CT) scan, and magnetic resonance image (MRI) of the brain were found to be normal. During hospitalization, she lost consciousness while swallowing an aerated beverage. Her telemetry revealed bradycardia followed by two periods of asystole lasting 7.5 and 6 s, respectively [Figure 1]. The asystole resolved spontaneously within a few seconds. A diagnosis of swallow syncope was made. A single-chamber pacemaker was inserted on the recommendation of a cardiologist. An esophagogastroduodenoscopy (EGD) was performed to rule out esophageal disorders, which showed reflux esophagitis and non-erosive gastritis in the antrum. The patient has been completely asymptomatic for the past 18 months.

Figure 1.

(a) EKG at the time of admission. Rate: 66/min, normal sinus rhythm, normal-axis, PR interval 0.176 s, QRS duration 0.096 s, QTc interval 0.434 s. (b) Telemetry strip at the time of syncope. (S, swallow; 1-3 sinus bradycardia with a rate of 25-30/min; 3-4 asystole lasting ~7.5 s; 4-5 second asystole lasting ~6 s)

Case 2

A 78-year-old retired physician presented to his physician's office with the complaint of dizziness occurring daily for the last several months. Each episode started during deglutition and was associated with a sudden onset of generalized weakness and lightheadedness. These episodes would last 10-15 min. As a physician, he noted that his pulse rate and blood pressure decreased during the episodes. He also observed that consuming coffee before his meals prevented his symptoms during swallowing. His past medical history included hypertension, coronary artery disease, and sick sinus syndrome requiring dual-chamber pacemaker insertion. Interrogation of his pacemaker did not reveal any episodes of bradycardia or arrhythmia. His pacemaker was reprogrammed empirically, but no improvement in the symptoms was noted. Further evaluation included an echocardiogram, an EKG, and blood glucose monitoring during the episodes, which were all normal. He was given a clinical diagnosis of swallow syncope and he takes a cup of regular coffee before his meals to prevent the symptoms.

Case 3

An 80-year-old retired engineer came to the gastroenterology clinic for follow-up of his dysphagia. He had a left parietal lobe stroke 6 months ago. He reported episodes of lightheadedness after swallowing sticky foods like peanut butter or rice, occurring two to three times a month for the last 6 months. These episodes were sudden in onset and usually resolved within minutes. One week prior to the clinic visit, he had an episode of syncope. He felt a “belch” like sensation in his throat while eating barbecued meat and this was followed by loss of consciousness which lasted a few minutes. He did not have any signs of seizure activity. He had a history of hypertension, atrial fibrillation, carotid artery stenosis with bilateral carotid endarterectomy, and seizure disorder with last reported seizure 14 years ago. He took metoprolol, aspirin, amlodipine, and levetiracetam at home. His vital signs were stable and physical examination was unremarkable. His EKG and echocardiogram showed left ventricular hypertrophy, with a normal systolic function. He had a negative stress test. An EGD for the evaluation of dysphagia showed a hiatal hernia, a Schatzki ring, and non-erosive gastritis. Patient underwent continuous EKG monitoring while swallowing a meal in the coronary care unit (CCU) under the supervision of a cardiologist (EKG stress test). However, no conduction abnormalities were elicited during swallowing. A clinical diagnosis of swallow syncope was made and patient was recommended to take Hyoscyamine tablets on regular basis to prevent syncopal symptoms. He was also asked to avoid the trigger foods and has not had any attacks of syncopal episodes in the past 6 months.

DISCUSSION

The three cases presented here illustrate a unique problem of swallow syncope. So far, there have been less than 100 published cases of swallow syncope reported in the literature.[2,3] However, it may be more common than described due to a lack of awareness of this clinical entity.[4]

All cases were adults (age range = 31-80 years) who presented with sudden onset of symptoms during swallowing, ranging from self-limited lightheadedness to actual loss of consciousness.[5] Age of onset has been found to vary in the literature, ranging from 4[6] to 85 years.[7] Two of our three cases were males and male predominance is identified in the literature as well.[8] In each case, the onset of episodes was during the act of deglutition and each episode lasted for seconds to minutes with spontaneous resolution.[5] Almost all the cases reported in the literature have described the onset of symptoms during or immediately following the act of deglutition, making it an essential feature of the diagnosis. Duration of syncopal symptoms with swallowing ranged from 3 weeks in case 1 to 6 months in case 3. A broad range of duration of symptoms has been found in the literature with diagnosis being made in a few weeks to as long as 26 years after the onset of symptoms.[9] These findings suggest that the spectrum of symptoms is highly variable in both frequency and intensity in these patients.

Case 1 reported carbonated beverage as the trigger food,[7] whereas dry sticky foods were responsible for symptoms in case 3.[10] Both these cases had symptomatic episodes once in every few weeks. Most of the cases with an identified trigger food had intermittent symptoms as well[7,11]. On the other hand, patients who reported daily symptoms could not identify a trigger food, as seen in case 2.[5] Symptoms have been noted with different consistencies or temperatures of the trigger foods amongst the reported cases.[7,11,12,13] However, carbonated beverages have been implicated commonly.[10] Development of syncopal symptoms may be related to the release of dissolved carbon dioxide from the beverage in the lumen of esophagus and stomach resulting in increased intraluminal pressure in these organs, leading to vagal stimulation.[10,11]

Diagnosis was made on the basis of clinical features and the telemetry findings in case 1 [Figure 1]. Various types of transient conduction abnormalities during swallowing have been reported including asystole, sinus bradycardia, and atrioventricular (AV) block.[5,8,11,12] Even tachyarrhythmia has been implicated.[14] As cardiac and neurologic causes of syncope are more common, these disorders must be ruled out in all cases of swallow syncope. Furthermore, it is not always possible to have a diagnostic EKG or telemetry strip, especially in patients presenting to the office as in cases 2 and 3. The 24-h Holter monitor or provocative testing can help in making diagnosis in such cases.[6]

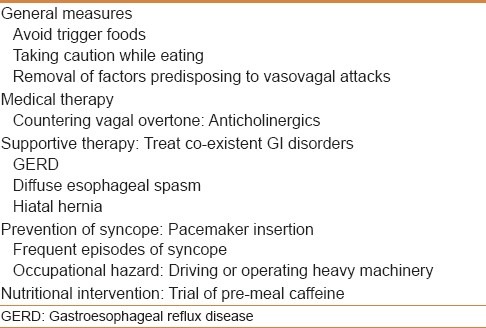

Provocative testing has been proposed to reproduce symptoms and confirm the diagnosis.[5,11,12,15] A continuous EKG recording during swallowing trigger foods or “swallow stress EKG” can be done. Case 3 had a negative “swallow stress EKG”. Similar findings have been reported previously,[8,16] and increased sympathetic tone has been implicated in preventing the development of symptoms during observation of the patient. Further investigations are needed to establish the sensitivity and specificity of the “stress EKG” testing. The other provocative test is esophageal balloon dilation. The severity of symptoms may vary with the regulation of esophageal dilatation from the balloon.[15] These observations can explain the intermittent nature of symptoms in many cases, where the esophagus gets distended to a symptom threshold only during some swallows to produce symptoms. This can also explain the observation that carbonated beverages are the common trigger foods. However, balloon dilatation of the esophagus for diagnosis of swallow syncope needs to be standardized in a prospective manner before more widespread clinical use. In the absence of any objective findings, a diagnosis of swallow syncope may be considered on clinical grounds as in cases 2 and 3 and confirmed with patient's response to various therapeutic measures [Table 1].

Table 1.

Summary of therapeutic options for swallow syncope

Case 1 was managed with a permanent pacemaker placement given her frequent episodes and her risk of having a syncopal attack at work, and she has been symptom free for the past 1 year. Most of the cases receiving a permanent pacemaker do not experience any further symptoms. Pacer interruptions have been noted to reproduce symptoms, indicating the need for permanent pacemaker.[10,13] A cardiology evaluation is indicated in patients with syncopal attacks for possible pacemaker placement. However, there is one instance where pacemaker placement did not alleviate the symptoms of swallow syncope.[4] A possible explanation for it was that the pacemaker only prevented the bradycardia but did not have any effect on the vasodepressor effect of vagal nerve stimulation which leads to hypotension and syncope. This was noted in case 2 who already had a pacemaker and continued to have symptoms despite a functioning pacemaker. A trial of temporary pacing while swallowing can be tried in such cases to establish the efficacy of pacing in preventing symptoms before a permanent pacemaker is implanted.[17] Case 2 learned to abort the symptoms by taking a cup of regular coffee before meals. Caffeine has been shown to increase sympathetic activity and decrease parasympathetic activity in human subjects.[18,19] In a randomized double-blinded trial, caffeine has also been shown to prevent vasovagal reactions in patients after blood donation.[20] It may exert a therapeutic action in swallow syncope by increasing the sympathetic discharge and countering the increased vagal tone. Anti-cholinergic medications like Hyoscyamine may also prevent symptoms of swallow syncope. However, controlled clinical trials are needed to establish their efficacy in this disorder. General measures advisable to every patient include avoiding trigger foods and the removal of medications that can cause orthostatic hypotension or bradycardia [Table 1].

Swallow syncope can be confused with post-parandial syncope.[21] However, post-parandial syncope presents with lightheadedness, sweating, and tremors, which occur 30-60 min after ingestion of food. Further, post-prandial syncope is associated with tachycardia rather than bradycardia. Glossopharyngeal neuralgia can also present with bradycardia and syncope during and after swallowing, However, it is associated with moderate to severe throat pain which is absent in swallow syncope.[22]

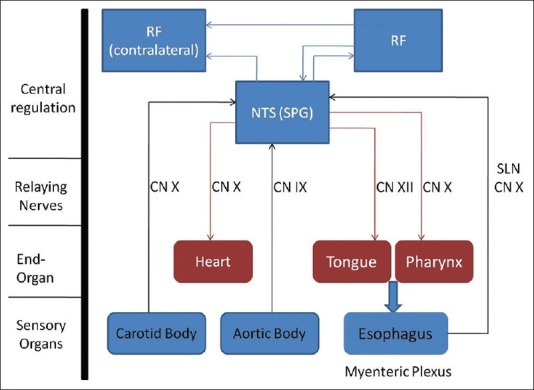

There is some association between swallow syncope and esophageal disorders as seen in cases 1 and 3. These disorders include gastroesophageal reflux disease, hiatal hernia, esophageal stricture, esophageal spasm, achalasia, and esophageal cancer.[2,23] A patient with suspected diagnoses of swallow syncope should be considered for a barium swallow, an upper endoscopy, and/or an esophageal manometry study. No causal relationship has been established between esophageal disorders and swallow syncope. However, we have postulated that esophageal disorders may alter sensory pathways from the esophagus to central nervous system (CNS) leading to syncope [Figure 2]. Adequate management of esophageal disorders may ameliorate the symptoms of swallow syncope.

Figure 2.

Swallowing and baroreceptor reflex arcs with NTS as the common relay point for both the arcs and a potential site of abnormality in swallow syncope. (CN, cranial nerve; NTS, nucleus of tractus solitarius; RF, reticular formation; SLN, superior laryngeal nerve; SPG, swallow pattern generator)

The underlying pathophysiology in swallow syncope is thought to be a vagus nerve mediated reflex. Various studies have revealed that swallowing is coordinated by a swallow pattern generator (SPG) present in the nucleus of tractus solitarius (NTS) in the CNS[24] [Figure 2]. The baroreceptor reflex is also a vagally mediated reflex relaying from the NTS[25] [Figure 2]. Based on the available information, we suspect that patients with swallow syncope may have altered signaling in the vagal neurons involved in esophageal peristalsis and baroreceptors in the carotid and aortic body, leading to syncopal symptoms after swallowing [Figure 2].

Although uncommon, swallow syncope should be kept in the differential diagnosis of unexplained episodes of syncope, especially when there is an association between symptoms and food ingestion.

Footnotes

Source of Support: Nil

Conflict of Interest: None declared.

REFERENCES

- 1.Daccarett M, Jetter TL, Wasmund SL, Brignole M, Hamdan MH. Syncope in the emergency department: Comparison of standardized admission criteria with clinical practice. Europace. 2011;13:1632–8. doi: 10.1093/europace/eur201. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Omi W, Murata Y, Yaegashi T, Inomata J, Fujioka M, Muramoto S. Swallow syncope, a case report and review of the literature. Cardiology. 2006;105:75–9. doi: 10.1159/000089543. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Mitra S, Ludka T, Rezkalla SH, Sharma PP, Luo J. Swallow syncope: A case report and review of literature. Clin Med Res. 2011;9:125–9. doi: 10.3121/cmr.2010.969. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Armstrong PW, McMillan DG, Simon JB. Swallow syncope. Can Med Assoc J. 1985;132:1281–4. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.James AH. Cardiac syncope after swallowing. Lancet. 1958;1:771–2. doi: 10.1016/s0140-6736(58)91578-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Woody RC, Kiel EA. Swallowing syncope in a child. Pediatrics. 1986;78:507–9. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Lichstein E, Chadda KD. Atrioventricular block produced by swallowing, with documentation by His bundle recordings. Am J Cardiol. 1972;29:561–3. doi: 10.1016/0002-9149(72)90450-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Tomlinson IW, Fox KM. Carcinoma of the oesophagus with ‘swallow syncope’. Br Med J. 1975;10:315–6. doi: 10.1136/bmj.2.5966.315. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Weiss S, Ferris EB. Adams-Stokes syndrome with transient complete heart block of vagovagal reflex origin: Mechanism and treatment. Archives of Internal Medicine. 1934;54:931–51. [Google Scholar]

- 10.Wik B, Hillestad L. Deglutition syncope. Br Med J. 1975;27:747. doi: 10.1136/bmj.3.5986.747. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Waddington JK, Matthews HR, Evans CC, Ward DW. Carcinoma of the oesophagus with ‘swallow syncope’. Br Med J. 1975;26:232. doi: 10.1136/bmj.3.5977.232-a. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Kopald HH, Roth HP, Fleshler B, Pritchard WH. Vagovagal syncope; report of a case associated with diffuse esophageal spasm. N Engl J Med. 1964;271:1238–41. doi: 10.1056/NEJM196412102712404. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Kunis RL, Garfein OB, Pepe JA, Dwyer EM., Jr Deglutition syncope and atrioventricular block selectively induced by hot food and liquid. Am J Cardiol. 1985;55:613. doi: 10.1016/0002-9149(85)90274-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Ho KL, Al Beshir M. Supraventricular tachycardia induced by swallowing. Ann Intern Med. 2012;157:531–2. doi: 10.7326/0003-4819-157-7-201210020-00020. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Nakagawa S, Hisanaga S, Kondoh H, Koiwaya Y, Tanaka K. A case of swallow syncope induced by vagotonic visceral reflex resulting in atrioventricular node suppression. J Electrocardiol. 1987;20:65–9. doi: 10.1016/0022-0736(87)90010-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Nakano T, Okano H, Konishi T, Ma W, Takezawa H. Swallow syncope after aneurysmectomy of the thoracic aorta. Heart Vessels. 1987;3:42–6. doi: 10.1007/BF02073646. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Kadish AH, Wechsler L, Marchlinski FE. Swallowing syncope: Observations in the absence of conduction system or esophageal disease. Am J Med. 1986;81:1098–100. doi: 10.1016/0002-9343(86)90418-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Lipsitz LA, Jansen RW, Connelly CM, Kelley-Gagnon MM, Parker AJ. Haemodynamic and neurohumoral effects of caffeine in elderly patients with symptomatic postprandial hypotension: A double-blind, randomized, placebo-controlled study. Clin Sci (Lond) 1994;87:259–67. doi: 10.1042/cs0870259. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Bonnet M, Tancer M, Uhde T, Yeragani VK. Effects of caffeine on heart rate and QT variability during sleep. Depress Anxiety. 2005;22:150–5. doi: 10.1002/da.20127. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Sauer LA, France CR. Caffeine attenuates vasovagal reactions in female first-time blood donors. Health Psychol. 1999;18:403–9. doi: 10.1037//0278-6133.18.4.403. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Jynsen RW, Lipsilz LA. Postprandial hypotension: Epidemiology, pathophysiology, and clinical management. Ann Intern Med. 1995;122:286–95. doi: 10.7326/0003-4819-122-4-199502150-00009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Teixeira MJ, de Siqueira SR, Bor-Seng-Shu E. Glossopharyngeal neuralgia: Neurosurgical treatment and differential diagnosis. Acta Neurochir (Wien) 2008;150:471–5. doi: 10.1007/s00701-007-1493-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Foreman J, Vigh A, Wardrop RM., 3rd Hard to swallow. Am J Med. 2011;124:218–20. doi: 10.1016/j.amjmed.2010.10.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Jean A. Brainstem control of swallowing: Localization and organization of the central pattern generator for swallowing. In: Taylor A, editor. Neurophysiology of the jaws and teeth. London: MacMillan; 1990. pp. 294–321. [Google Scholar]

- 25.Lipski J, Mcallen RM. The sinus nerve and baroreceptor input to the medulla of the cat. J Physiol. 1975;251:61–78. doi: 10.1113/jphysiol.1975.sp011081. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]