Abstract

Urea cycle disorders (UCDs) are a group of uncommon heterogeneous conditions that are often detected in childhood and only rarely in adults where the presentations are subtle or non specific with symptoms of confusion and encephalopathy. N-acetyl-glutamate synthase (NAGS) deficiency is a rare urea cycle disorder that uncommonly presents in adulthood. To date there has been no detailed neurological description of an adult onset presentation of NAGS deficiency. In this review we examine the clinical presentation and management of UCDs with an emphasis on NAGS deficiency. An illustrative case is provided. Plasma ammonia levels should be measured in all patients with unexplained encephalopathy as treatment can be life-saving. Management of this rare disorder includes protein restriction and adjunct pharmacologic treatment to reduce plasma ammonia levels. Genetic counselling remains an essential component of management of UCDs.

Background

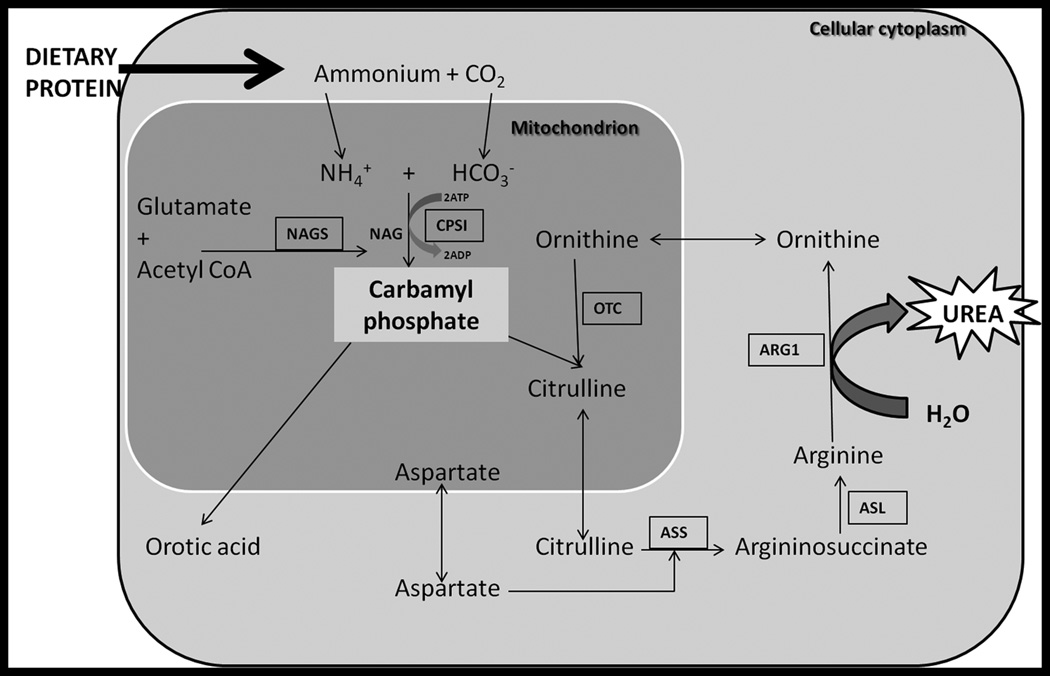

In humans and other mammals nitrogen is produced by the catabolism of proteins and excreted as urea via the kidneys through the process of the urea cycle1 (Fig. 1). The urea cycle which is active primarily in the liver converts waste nitrogen into the form of ammonium. Deficiencies of enzymes in the urea cycle may result in the accumulation of ammonium. Urea cycle disorders may present from infancy to adulthood.

Fig 1.

Simplified version of urea cycle depicted. The urea cycle converts protein into urea which is excreted by the kidneys. There are six enzymes involved: N-acetylglutamate synthase (NAGS), carbamyl-phosphate-synthetase-I (CPSI), ornithine transcarbamylase (OTC), argininosuccinate synthetase (ASS), argininosuccinate lyase (ASL), arginase (ARG1). Further abbreviations: adenosine triphosphate (ATP), adenosine diphosphate (ADP. Figure based upon www.uptodate.com.

Urea cycle review

The urea cycle consists of 6 enzymes and two mitochondrial membrane transporters (Fig. 1): N-acetyl glutamate synthase (NAGS), carbamyl phosphate synthetase I (CPSI), ornithine transcarbamylase (OTC), argininosuccinate synthetase (ASS), argininosuccinate lyase (ASL), arginase, the aspartate transporter (citrin), and the ornithine transporter1, 23. An interruption in any step of the urea cycle may cause a build-up of ammonium which is neurotoxic and if untreated may result in coma and death. All disorders except for X-linked OTC deficiency are inherited in an autosomal recessive manner. CPSI, NAGS, and OTC are located in mitochondria therefore can be affected by other mitochondrial diseases or perturbations. The incidence of UCDs in the United States is approximately 1 in 82004. Prenatal testing based on mutation analysis is available for all six conditions5–7.

Clinical presentation of UCDs

The typical presentation for a urea cycle disorder is in the first few days of life. The infant may present with gastrointestinal symptoms such as vomiting typically occurring after feeding (protein load). Neurological symptoms such as lethargy, seizures and coma can follow quickly; a presentation identical to that of an infant with sepsis however a non-diagnostic work-up for sepsis should raise the clinical suspicion for an inborn error of metabolism. A common sign is hyperventilation and respiratory alkalosis as ammonium is a CNS stimulant. Hyperventilation is thought to result from cerebral edema caused by the build up of ammonium;8 however hyperventilation can also be seen without evidence of cerebral edema. Neonates who present in the first few days of life do so as a result of the catabolic stress of labour and delivery and low fluid intake in the immediate post natal period.

Patients who have partial enzyme deficiencies, such as female carriers (X-linked OTC deficiency) will often have a delayed presentation despite a lifelong history of chronic cyclical nausea and vomiting, and possibly a seizure disorder or a psychiatric illness9. There may also be developmental delay. Many patients self-select a low protein diet. In all groups of patients hyperammonemic crises may occur with increased catabolic stress caused by infection, starvation, surgery or trauma.

Approach to a patient with a suspected UCD

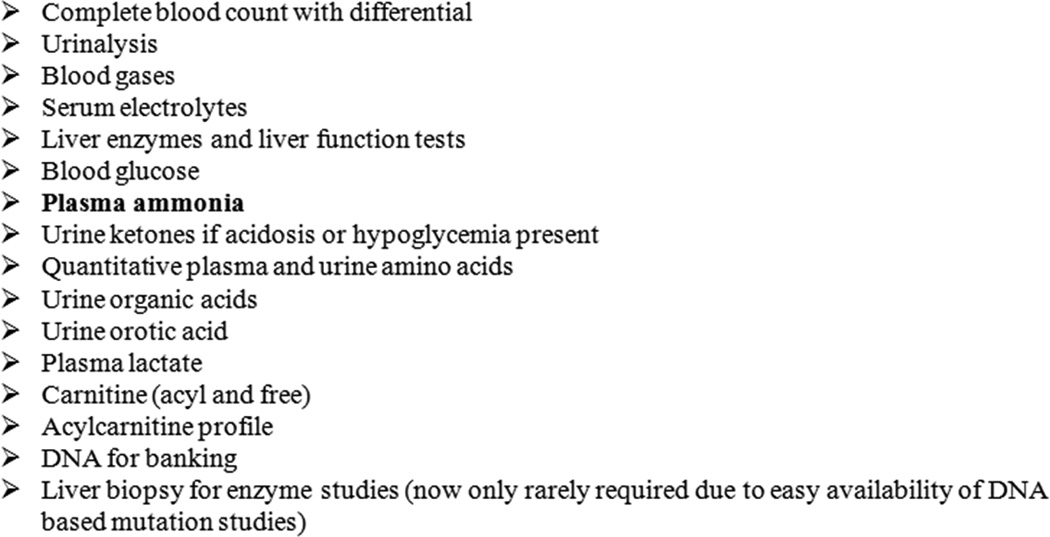

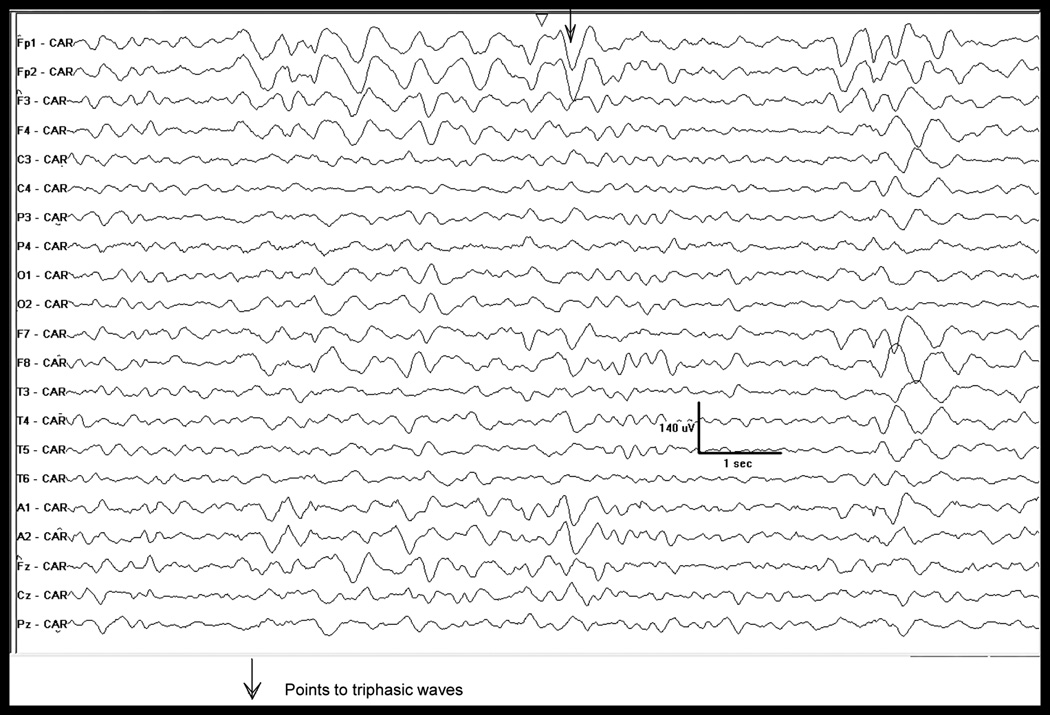

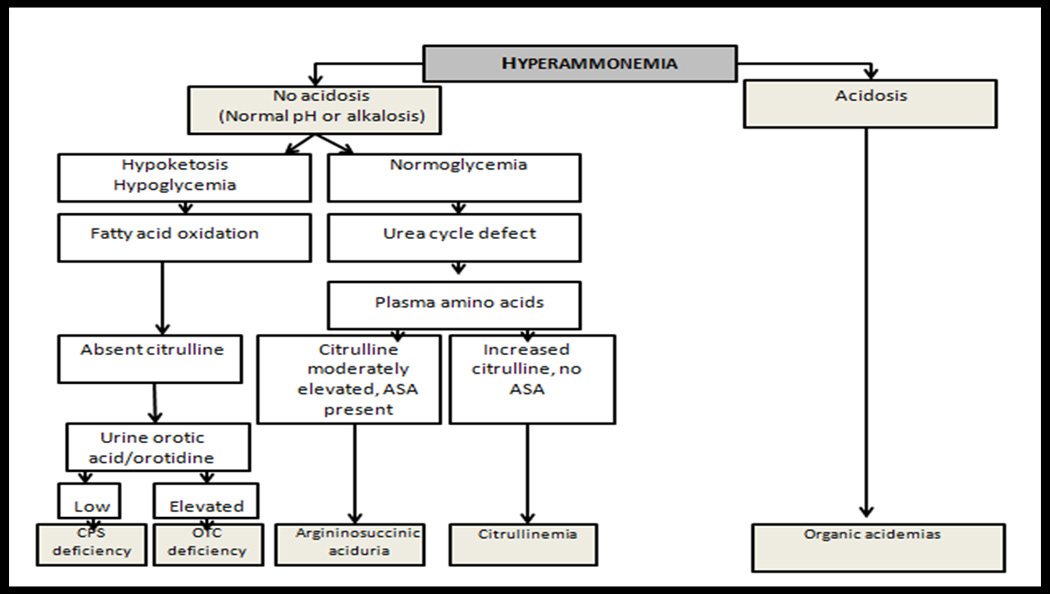

The approach to a patient considered to have a UCD includes a comprehensive neurological assessment with particular attention to family history and key clinical features such as behavioural changes, protein aversion and gastrointestinal symptoms. Investigations should first and foremost include an ammonia level. Other key investigations include arterial pH, serum lactate, serum glucose and CSF analysis, (with hyperammonemia there can be cerebral edema so CSF analysis should only be performed with caution) (Fig. 2). It is important to note that hyperammonemia may be chronic or occur only during metabolic decompensation and therefore investigations can be normal10. EEG (Fig. 3) and magnetic resonance (MR) imagings can be helpful investigations. Fluid attenuated inversion recovery sequence (FLAIR) on MR imaging has been suggested to identify white matter tract abnormalities that can exist in UCDs11. Other imaging techniques described to show abnormalities include diffusion tensor imaging (DTI) and MR spectroscopy. If plasma ammonia is elevated then metabolic indices such as plasma amino acids, urine orotic acid and urine organic acids should be measured. The importance of testing these metabolic indices is to differentiate among the various UCDs (Fig. 4). A genetics and metabolic consultation is useful to proceed with further work up for molecular analysis or tissue enzyme analysis. Patients suspected to be having a UCD should be managed in an intensive care setting as this is a medical emergency. Cerebral edema occurs early with severe hyperammonemia, and delays in reducing the level of ammonia may lead to serious neurological complications including death due to increased intracranial pressure with herniation. Survival from a severe episode often carries with it irreversible brain damage. Treatment should thus not be delayed if a UCD is suspected.

Fig 2.

Recommended laboratory studies for a patient with a suspected inborn error of metabolism. (Modified from Burton B. Inborn errors of Metabolism in Infancy: A Guide to Diagnosis. Pediatrics 1998;102(6):e69-e77.)

Fig 3.

Electroencephalogram. Referential montage (common average reference) shows diffuse background slowing (delta) with the intermittent appearance of triphasic waves, with a bifrontal predominance.

Fig. 4.

Flow chart for the approach to hyperammonemia. Modified from Burton B. Inborn errors of Metabolism in Infancy: A Guide to Diagnosis. Pediatrics 1998;102(6):e69–e77., and Summar M. Current strategies for the management of neonatal urea cycle disorders. J Pediatr. 2001 Jan;138(1 Suppl):S30-9.

Medical and metabolic management

In an emergent presentation physiologic stabilization is most important; adjunctive treatment may include intravenous fluids, and possibly hemodialysis for ammonia removal. The mainstay of ongoing management of NAGS deficiency, as with all UCDs is maintenance of plasma ammonia levels in a normal range by limiting protein intake, avoiding periods of catabolic stress, and using nitrogen scavenger drugs to allow an alternate pathway for the excretion of nitrogen precursors12, 13 (e.g. sodium phenylbutyrate). In NAGS deficiency recently specific treatment with carglumic acid, a structural analog of NAG has been used as it has been shown to activate CPSI14–17 and restore ureagenesis2, 9 Patients receiving carglumic acid typically do not require a protein restricted diet.

NAGS deficiency

N-acetylglutamate synthase (NAGS; MIM# 608300), one of the three mitochondrial enzymes of the urea cycle, produces N-acetylglutamate (NAG) from glutamate and acetyl coenzyme A (Acetyl CoA). N-acetylglutamate (NAG) was first identified in the 1950’s and initially discovered as an intermediate in the arginine-biosynthetic pathway of Escherichia coli. NAG synthase (NAGS) was later described as an essential allosteric cofactor of mitochondrial carbamylphosphate synthetase I (CPSI), the first enzyme of the urea cycle18. NAGS is primarily expressed in the liver and in the small intestine and its product, NAG, is postulated to activate CPSI19. Hyperammonemia can result once CPSI is deprived of its co-factor NAG.

The first case report of NAGS deficiency was published in 198120 and subsequently approximately 34 other cases of NAGS deficiency have been reported with most patients presenting in the neonatal period17. NAGS deficiency is the least common UCD and few late-onset neurological presentations have been described2, 20, 21,22; the gene mutation maps to chromosome 17q21.3119. There are 22 published mutations up to date that have been described for NAGS3, 23.

Deficiencies of NAGS activity can either be inherited (mutation in NAGS gene) or acquired by a secondary inhibition of NAGS activity in some conditions which cause short chain fatty acid accumulation such as some organic acidemias and the use of valproic acid.

A detailed summary of published cases of NAGS in the literature is listed in Table 1. In total 34 cases of confirmed NAGS deficiency were identified. This mini review will help with the understanding of the genetic aspects and key neurologic features associated with UCDs and therefore prompt earlier diagnosis and treatment. We discuss the unique presentation of an adult-onset UCD. Our patient had a history of behavioural change and confusion which is in keeping with a late-onset UCD. An adult presentation of NAGS deficiency however is very rare. No trigger was identified in our patient to account for his hyperammonemic crises.

Table 1.

Summary of findings in reported cases of confirmed N-acetylglutmate synthase (NAGS) deficiency. Legend: Ukn (unknown), LOC (loss of consciousness), CPS (carbamoyl phosphate synthetase) mat. (maternal), EEG (electroencephalogram), VPA (valproic acid), Gln (Glutamine), Cit (Citrulline), ND (Not Detectable).

| Case | Age at diagnosis; Sex |

Background | Family History | Clinical findings |

Death | Peak Ammonia* Normal <50 mol/L |

Gln on admission* Normal 109–750 mol/L |

Cit on admission* Normal 10– 50 mol/L |

Diagnosis by: enzyme analysis OR molecular studies |

Citation |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Consanguinity | ||||||||||

| 1 | 6 male | Ukn | Ukn | vomiting, feeding intolerance, episodic confusion | No | 500 | Ukn | Ukn | NAGS deficiency on mutation analysis | Corne et al. Mol Genet Metab 2011; 102;275.34 |

| 2 | Screened at birth; female | Turkish | Yes; older sister died of severe hyperammonemia (NAGS deficiency not confirmed) | asymptomatic | No | 393 | Ukn, but 1961 on subsequent admission | Ukn | Second liver biopsy: reduced NAGS activity, later found to be homozygous for NAGS mutation | Gessler et al. Eur J Pediatr 2010;169:197–199.35 |

| First cousins | ||||||||||

| 3 | At birth; Ukn | Ukn | Ukn | coma, seizures | No | >1400 | Ukn | Ukn | NAGS deficiency on mutation analysis | Nordenstrom et al. J Inherit Metab Dis 2007; 30:400.36 |

| 4 | 40 years; female | Ukn | Ukn | intermittent staring spells, nausea, recurrent vomiting, lethargy, ataxia, migraine headaches, eventually coma | No | 500 | Ukn | Ukn | NAGS deficiency on mutation analysis | Tuchman et al. Pediatr Res 2008;64(2):213–217.22 |

| 5 | 33 years; female | Ukn | Ukn | episodic altered mental status with coma after caesarean section. Psychomotor seizures | No | 138 – 4781 | Ukn | NAGS deficiency on mutation analysis | Grody et al. J Inherit Metab Dis.1994;17(5):5 66–574.37 Caldovic et al. Human Mutat.2007;28(8) 754–759.3 | |

| 6 | 4 days; female | Ukn | Ukn | hypotonia, drowsiness, tremor, and no suck | No | 182 | 1150 | 13 | NAGS deficiency on mutation analysis | Guffon et al. J Pediatr 2005;147:260–262.38 Schmidt et al. Biochim Biophys Acta. 2005;1740:54–59.39 |

| Yes; same village | ||||||||||

| 7 | 3 months; male | French | Ukn | muscular axial hypotonia, hyporeactivity, hepatomegaly | No | 113–367 | 841 | 19 | NAGS deficiency on mutation analysis | Guffon et al. J Pediatr 2005;147:260–262.38 Schmidt et al. Biochim Biophys Acta. 2005;1740:54–59.39 |

| Yes; first cousins | ||||||||||

| 8 | Screened at birth; male | Ukn | Older sister died of severe hyperammonemia, no diagnosis made | asymptomatic | No | 208 | 1114 | <4 | NAGS deficiency on mutation analysis | Guffon et al. J Pediatr 2005;147:260–262. Schmidt et al. Biochim Biophys Acta. 2005;1740:54–59.39 |

| No | ||||||||||

| 9 | 4 weeks; female | Ukn | No | recurrent vomiting, irritability, lethargy, later-on headaches, hallucinations | No | 256 | elevated | normal | Initially NAGS not assayed on liver biopsy Later NAGS deficiency on mutation analysis | Caldovic et al. J Pediatr 2004;145:552–554.18 |

| 10 | 9 years; female | Yes; younger sister case 9 | lethargy, anorexia, vomiting, respiratory distress and seizures | No | 978 | 1710 | ND | |||

| 11 | 33 years; male | White | None | post-operative combativeness, confusion, seizures | Yes | 621 | elevated | Low | NAGS deficiency on mutation analysis | Caldovic et al. Hum Mutat. 2005;25(3):293–298.2 |

| No | ||||||||||

| 12 | 12 years; male | Ukn | Ukn | vomiting, decreased LOC with protein, EEG showed left temporal lobe spikes | No | 350 | 801 | 21 | Liver biopsy: L-Arginine unable to activate NAGS and normal CPS activity. | Belanger-Quintana et al. Eur J Pediatr. 2003;162(11)773 .775.40 |

| No | ||||||||||

| 13 | 3 days; Ukn | Turkish | Ukn | Ukn | Ukn | Ukn | Ukn | NAGS deficiency on mutation analysis | Haberle et al. Human Mutat.2003;21(6) 593–597.23 Heckmann et al. Acta Paediatr.2005;94 (1):121–124.41 |

|

| Yes | ||||||||||

| 14 | 3–4 days; ukn | Turkish | Ukn | Ukn | Ukn | Ukn | Ukn | NAGS deficiency on mutation analysis | Haberle et al. Human Mutat.2003;21(6) 593–597.23 | |

| Yes | ||||||||||

| 15 | 6 days; Ukn | German | Ukn | Ukn | Ukn | Ukn | Ukn | Liver biopsy: No NAGS activity; later NAGS mutation found | Haberle et al. Human Mutat.2003;21(6) 593–597.23 | |

| No | ||||||||||

| 16 | 3 days; Ukn | Turkish | Ukn | Ukn | Ukn | Ukn | Ukn | NAGS deficiency on mutation analysis | Haberle et al. Human Mutat.2003;21(6) 593–597.23 Schmidt et al. Biochim Biophys Acta. 2005;1740:54–59.39 |

|

| Yes | ||||||||||

| 17 | 3 days; female | German | Ukn | signs of cerebral edema | Yes | 942 | Liver biopsy: reduced NAGS activity, NAGS mutation confirmed using cultured fibroblasts and DNA sequencing | Haberle et al. J Inherit Metab Dis 2003;26(6):601–605.42 Haberle et al. Human Mutat.2003;21(6) 593–597.23 |

||

| No | ||||||||||

| 18 | 16 hours; male | Faroe Islands | Ukn | tachypnea, jitteriness, hypertonia, hypothermia, coma | Yes | Ukn | elevated | ND | Post-mortem liver tissue: reduced NAGS Later parents found to be heterozygotes | Caldovic et al. Hum Genet 2003; 112:364–368.43 Takanashi J., et al. Am J Neuroradiol (in press) 2002.44 |

| Distant approxim ately 5 generations back | ||||||||||

| 19 | 3 days; female | Hispanic/No | No | lethargy, anorexia, respiratory distress, coma, seizures | No | 1700 | 1268 | ND | Molecular studies: both homozygous for NAGS gene mutation | Caldovic et al. Hum Genet 2003; 112:364–368.43 |

| 20 | 2 days; female | Yes; younger sibling case 19 | lethargy, anorexia, vomiting, respiratory distress and seizures | No | 978 | 1710 | ||||

| 21 | 4 days; male | Iranian Jewish/First cousins | Ukn One of twin (other twin unaffected) | unresponsive, seizures | No | 1300 | 2652 | ND | Initial liver biopsy inconclusive, later molecular analysis confirmed homozygous NAGS gene mutation | Elpeleg et al. Ann Neurol. 2002;52(6):845–89.45 |

| 22 | at birth; male | Yes; younger brother to case 21 | coma | No | 1900 | 1732 | ND | Homozygous NAGS gene mutation | ||

| 23 | 4 years; male | Ukn | None | irritability, vomiting, lethargy, protein refusal, ataxia, worsened with VPA | No | 229 | 920 | Ukn | Liver biopsy: NAGS activity reduced 26% control | Forget et al. Acta Paediatr. 1999;88(12)1409–1411.46 |

| No | ||||||||||

| 24 | 12 years 11 months; female | Austrian/Slovenian | No | vomiting, protein aversion, restlessness, disorientation, aggression, hyperreflexia | No | 221 | 1616 | 12 | Partial NAGS deficiency Liver biopsy: NAGS activity reduced 15% control | Plecko et al. Eur J Pediatr. 1998;157(12):99 6–998.47 Haberle et al. Hum Mutat. 2003;21(6):593–597.23 |

| No | ||||||||||

| 25 | 4 days; female | Ukn | Ukn | vomiting, hyperventilation, respiratory alkalosis | No | 316 | 1186 | ND | Liver biopsy: NAGS activity <5% control | Morris et al. J Inherit Metab Dis. 1998;21(8):867–868.48 |

| First cousins | ||||||||||

| 26 | 20 years; male | Ukn | Ukn | confusion, combative behaviour | No | 525 | 1571 | 2 | Partial NAGS deficiency Liver biopsy: NAGS activity <50% control | Hinnie et al. J Inherit Metab Dis. 1997;20(6):839–840.49 |

| Yes; first cousins | ||||||||||

| 27 | 3–4 days; male | Ukn | Ukn | oliguria, trembling, seizure, hypotonia, coma | No | 530 | 1054 | <1 | Liver biopsy: NAGS activity <10% control | Guffon et al. J Inherit Metab Dis. 1995;18(1):61–65.17 |

| Yes; first cousins | ||||||||||

| 28 | 5 years 7 months; male | Taiwanese | Ukn | history of lethargy and poor appetite | No | >200 | 850 | 24 | Liver biopsy: NAGS activity reduced to 9.7% of control | Vockley et al. Biochem Med Metab Biol. 1992;47(1):38–46.50 |

| No | ||||||||||

| 29 | 5 months; female | Ukn | Ukn | vomiting, hypotonia, visual impairment, persistent head and body shaking | No | 285 | 755 | 6 | Partial NAGS deficiency Liver biopsy: NAGS activity reduced to 40% of control | Burlina et al. J Inherit Metab Dis. 1992;15(3):395–398.51 |

| No | ||||||||||

| 30 | 5–6 weeks; male | Ukn | Petit mal seizures in mat. aunt and mat. grandfather, migraine headaches in mother. Brother died at 14 months after developing seizures and liver failure | hospitalized at age of 5 weeks for episode of gastroenteritis, lethargy, developed seizures | No | 215 | Elevated | Low | Liver biopsy revealed NAGS activity undetectable | Pandya et al. J Inherit Metab Dis. 1991;14(5):685–690.52 |

| 31 | 26 days; male | Yes (younger sibling case 30) | diarrhoea, irritability, tachypnea, hypertonia | No | 185 | Elevated | Low | None; positive family history | ||

| 32 | 13 months; female | Muslim | Yes, sister and male cousin (similar course) | coma, hypotonia, hyperreflexia, hepatomegaly, EEG showed triphasic waves | Yes | 241 | 549 | ND | Partial NAGS deficiency Liver biopsy: NAGS activity reduced to 33% of control | Elpeleg et al. Eur J Pediatr. 1990 Jun;149(9):634–636.53 |

| First cousins | ||||||||||

| 33 | 6 days; male | Ukn | None | poor feeding, vomiting, hypotonia, respiratory alkalosis | Yes | 711 | 940 | ND | Liver biopsy: NAGS activity Not detectable | Bachmann et al. J Inherit Metab Dis. 1988;11(2):191–193.54 |

| No | ||||||||||

| 34 | Screened at 3 days; male | Ukn | 2 siblings died during neonatal period, postmortem analysis from 2nd sibling suggested ↑ ammonia | hyperthermia, muscular hypertonia, respiratory distress, abdominal distension | Died at age 9 | 242 | 1020 | Ukn | Liver biopsy: NAGS activity Not detectable | Bachmann et al. N Engl J Med. 1981 Feb 26;304(9):543.20 (INDEX CASE) Schubiger et al. Eur J Pediatr. 1991 Mar;150(5):353–356.55 |

| No | ||||||||||

| 35 | 38; male | Irish-Scottish | None | Episodic confusion, nausea and vomiting | No | 434 | 1062 | 15 | NAGS deficiency on mutation analysis | |

| No |

Levels may vary from institution.

Illustrative Case

The patient was symptomatic in early childhood and adulthood with symptoms of hyperammonemia in the setting of a negative family history although no ammonia level was checked until his hospitalization at age 38 years. A key clinical feature was an almost 20 year history of fluctuating behavioural changes associated with nausea and vomiting. A 38-year old left-handed male dairy farmer was referred for acute confusion and bizarre behavioural changes. His past medical history was notable for similar episodes dating as far back as 18 years. There had been no previous psychiatric or neurologic evaluation however a normal cranial CT had been reported. He was taken to the emergency room by his wife and upon assessment he described ongoing nausea and vomiting as well as headache. The patient had completed secondary school and two years of college with no history of learning difficulties. He was from a non-consanguineous Irish and Scottish background with no relevant family history.

On examination vital signs were stable. There was behavioural disinhibition and fluctuating drowsiness. A mini-mental status examination (MMSE) score was 23/30, (points lost for five-minute recall, three-step command, and constructing intersecting pentagons). Cranial nerve examination and power testing was normal. There was mild spasticity on assessment of muscle tone with brisk reflexes, sustained ankle clonus, and down-going plantar reflexes. Coordination was impaired. Significant asterixis was present and gait assessment was normal. Otherwise general examination was unremarkable.

The patient was admitted to hospital. Extensive laboratory studies were all were within normal limits. Magnetic resonance imaging of head and full-spine were reviewed with expert neuro-radiologists and deemed normal. Plasma ammonia was found to be markedly elevated at 434 umol/L (15–55 umol/L). A blood gas revealed a mild respiratory alkalosis. Continuous electroencephalogram (EEG) monitoring (Fig. 3) demonstrated severe generalized encephalopathy with associated triphasic waves suggesting metabolic or hepatic etiology with no epileptiform activity.

The patient responded well to intravenous fluids, lactulose and a relatively lower protein diet. Upon discharge plasma ammonia levels decreased to 85 umol/L. A referral was made to a genetics/metabolics specialist to further investigate an underlying metabolic etiology.

A complete metabolic work-up revealed an elevated glutamine level of 1062 µmol/L (109–750 µmol/L), normal citrulline at 15 µmol/L (10–50 µmol/L), and normal urine amino acids. Urine orotic acid level was normal. On molecular studies OTC gene sequencing was normal (this was done as OTC deficiency is the most common UCD and orotic acid can be normal in OTC patients). Molecular sequencing of the NAGS gene was performed and the patient was found to be a compound heterozygote for E433G and IVS6+5 G > A, both novel mutations. The intronic mutation involved a consensus base pair located 5 bp downstream of an exon/intron boundary, in the donor splice site of intron 6. A G>A substitution in this position is expected to reduce efficiency of splicing of NAGS mRNA and lead to decreased, but not absent, expression of NAGS from this allele24. The residual NAGS expression from this allele likely resulted in sufficient NAGS enzymatic activity to avoid neonatal hyperammonemia, and may serve to explain a delayed onset in adult life in our patient.

NAGS sequencing of both parents was also performed. The patient’s father was confirmed to be a carrier of the IVS6+5 G >A mutation, but interestingly, no mutation was identified in the patient’s reported biological mother. Non-maternity, gonadal mosaicism or a de novo mutation may explain the absence of the E433G mutation in the mother.

Medical management of our case

A relatively low protein diet (around 1 gm/kg about <73 g/day) was commenced and our patient’s ammonia level was maintained in the normal range. Initially he was also started on sodium phenylbutyrate 200 mg/kg TID (4500 mg TID) and citrulline 50mg/kg TID (1200 mg TID). Sodium phenylbutyrate reduces ammonia production by creating an alternate pathway for the excretion of nitrogen containing precursors while citrulline also aids in nitrogen clearance and in maintaining the arginine pool in proximal UCDs.

Carglumic acid

Our patient was eventually switched to carglumic acid 1200 mg TID and a more liberalized protein intake once the diagnosis of NAGS deficiency was confirmed. The switch was made to carglumic acid because of non-compliance with a low-protein diet, intolerance to sodium phenylbutyrate and citrulline (stomach distress and body odour) and the specificity of carglumic acid to NAGS deficiency. Carglumic acid activates CPSI therefore leading to a reduction in ammonia levels. Currently our patient’s ammonia levels are normal and range from 29–35 umol/L.

Carglumic acid is much more expensive than sodium phenylbutyrate (daily cost 1961.00CAD$ for carglumic acid vs. 8.46CAD$ for sodium phenylbutyrate at current prices) however carglumic acid is the standard of care for patients with NAGS deficiency despite the cost, as treatment with scavengers and protein restriction are insufficient to prevent breakthrough hyperammonemia which would cause resultant increase in patient morbidity.2526

Long-term management and morbidity

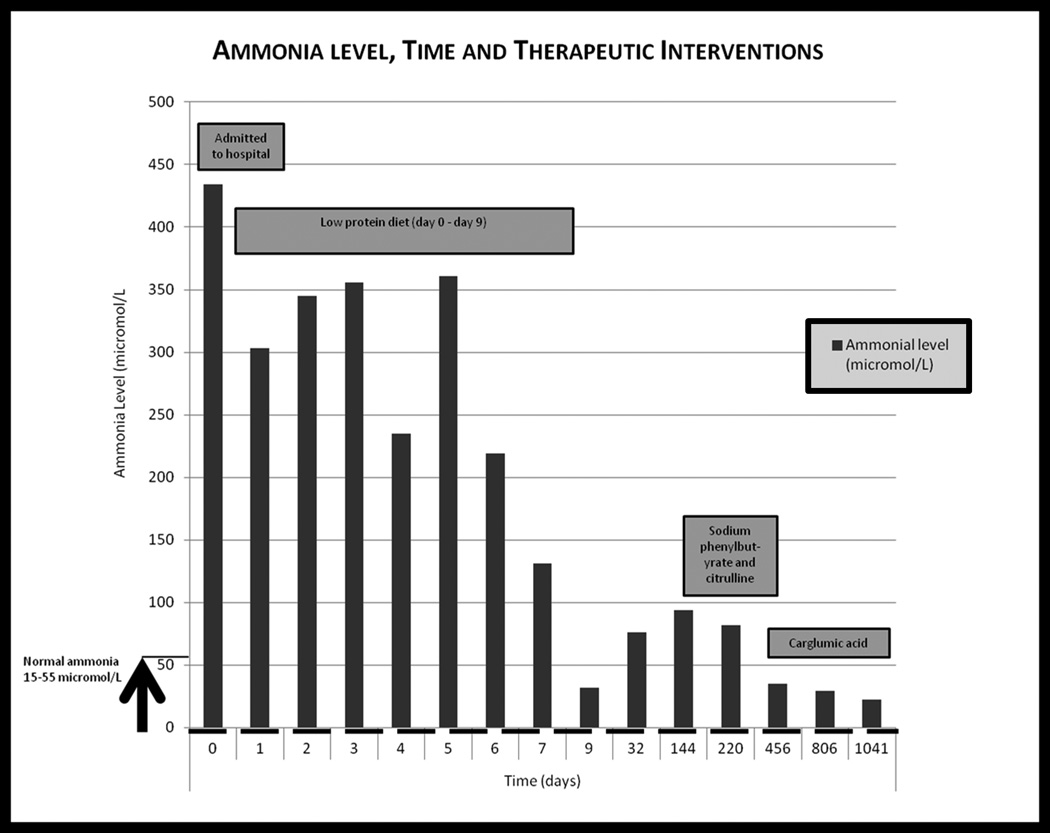

Our patient did eventually resume his work on the farm but remains troubled with short term memory loss. His behaviour has also shown a marked improvement. He has not had a hyperammonemic crisis for the last two years. His therapeutic course has been plotted (Fig. 5).

Fig. 5.

Graph of our patient’s ammonia level versus time with therapeutic interventions included. Day 0 is day of presentation. Normal ammonia values 15–55 umol/L.

Patients with UCD can present at any age and during hyperammonemic crises mortality can be as high as 10%27. In chronic management avoidance of periods of stress is important. Other neurologic sequelae of hyperammonemia may include seizures and/or developmental delay. Evidence suggests that virtually all survivors of a hyperammonemic coma are left with developmental delay28–30. Cognitive impairment in adult-onset presentations has been described even in asymptomatic OTC-deficient heterozygous women (learning disabilities and attention deficit hyperactivity disorder)31, 32. Although not specific to NAGS deficiency a recent review by Gropman et al33 does suggest that there is a neurochemical basis for cognitive and motor delay that may not only involve ammonia and glutamine as neurotoxins, but also alterations in the levels of neurotransmitters all leading to neuropathological changes. No specific literature exists regarding documenting cognitive deficits in adult-onset presentation of NAGS deficiency as it is a very rare condition.

Conclusions

Plasma ammonia should be measured in all patients with an unexplained encephalopathy including cyclical presentations to identify potential underlying metabolic disorders. EEG can be a clue with the presence of triphasic waves indicating a metabolic encephalopathy. Hyperammonemia with a normal anion gap and normal serum glucose should be investigated to rule out a urea cycle disorder. Our illustrative case describes a rare presentation of a rare urea cycle disorder. Management for these patients requires a multidisciplinary approach including a dietician, social worker and a genetic counsellor. Awareness of inborn errors of metabolism presenting with neuro-psychiatric manifestations is essential for all adult neurologists and psychiatrists. Genetic counselling is an important component of UCDs management.

Acknowledgements

We thank the patient and family for giving us permission to share their information. We thank Suzanne Ratko (dietitian) for her help with the nutritional management of the patient and Jill Tosswill (social worker) for her help with the social issues. The NAGS mutation testing was done in Dr. Mendel Tuchman’s laboratory in Washington, DC.

This study did not receive sponsorship or funding.

Abbreviations

- CPSI

Carbamoyl Phosphatase Synthase-I

- OTC

Ornithine Transcarbamylase

- ASL

Argininosuccinic acid Lyase

- UCD

Urea cycle disorder

- PCR

Polymerase chain reaction

- CSF

Cerebrospinal fluid

- bp

Base pair

Footnotes

Author contributions: Dr. Cartagena drafted and wrote the manuscript. All others were directly involved in helping with writing, editing the manuscript and provided expert advice.

Dr. A. M. Cartagena reports no disclosures.

Dr. A. N. Prasad reports no disclosures

Dr. C A Rupar reports no disclosures

Dr. M. Strong reports no disclosures

Dr. M. Tuchman reports no disclosures

Dr. N. Ah Mew reports no disclosures

Dr. C. Prasad reports no disclosures

Electronic Database information. URLs used in preparation of this article are

Locus Link. National Center for Biotechnology Information, National Library of Medicine (Bethesda, MD), 1999. World Wide Web URL:http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.org/LocusLink

Online Mendelian Inheritance in Man, OMIM (TM). Center for Medical Genetics, Johns Hopkins University (Baltimore, MD) and National Center for Biotechnology Information, National Library of Medicine (Bethesda, MD), 1999. World Wide Web URL: http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/omim/

References

- 1.Brusilow SW. Urea cycle disorders: clinical paradigm of hyperammonemic encephalopathy. Prog Liver Dis. 1995;13:293–309. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Caldovic L, Morizono H, Panglao MG, et al. Late onset N-acetylglutamate synthase deficiency caused by hypomorphic alleles. Hum Mutat. 2005;25:293–298. doi: 10.1002/humu.20146. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Caldovic L, Morizono H, Tuchman M. Mutations and polymorphisms in the human N-acetylglutamate synthase (NAGS) gene. Hum Mutat. 2007;28:754–759. doi: 10.1002/humu.20518. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Brusilow SW, Maestri NE. Urea cycle disorders: diagnosis, pathophysiology, and therapy. Adv Pediatr. 1996;43:127–170. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Altarescu G, Brooks B, Eldar-Geva T, et al. Polar body-based preimplantation genetic diagnosis for N-acetylglutamate synthase deficiency. Fetal Diagn Ther. 2008;24:170–176. doi: 10.1159/000151333. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Sniderman King L, Singh RH, Rhead WJ, Smith W, Lee B, Summar ML. Genetic counseling issues in urea cycle disorders. Crit Care Clin. 2005;21:S37–S44. doi: 10.1016/j.ccc.2005.08.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Kamoun P, Fensom AH, Shin YS, et al. Prenatal diagnosis of the urea cycle diseases: a survey of the European cases. Am J Med Genet. 1995;55:247–250. doi: 10.1002/ajmg.1320550220. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Butterworth RF. Effects of hyperammonaemia on brain function. J Inherit Metab Dis. 1998;21(Suppl 1):6–20. doi: 10.1023/a:1005393104494. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Tuchman M, Lee B, Lichter-Konecki U, et al. Cross-sectional multicenter study of patients with urea cycle disorders in the United States. Mol Genet Metab. 2008;94:397–402. doi: 10.1016/j.ymgme.2008.05.004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Tuchman M, Yudkoff M. Blood levels of ammonia and nitrogen scavenging amino acids in patients with inherited hyperammonemia. Mol Genet Metab. 1999;66:10–15. doi: 10.1006/mgme.1998.2783. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Gropman A. Brain imaging in urea cycle disorders. Mol Genet Metab. 2010;100(Suppl 1):S20–S30. doi: 10.1016/j.ymgme.2010.01.017. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Batshaw ML, Painter MJ, Sproul GT, Schafer IA, Thomas GH, Brusilow S. Therapy of urea cycle enzymopathies: three case studies. Johns Hopkins Med J. 1981;148:34–40. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Batshaw ML, MacArthur RB, Tuchman M. Alternative pathway therapy for urea cycle disorders: twenty years later. J Pediatr. 2001;138:S46–S54. doi: 10.1067/mpd.2001.111836. discussion S54-45. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Ah Mew N, McCarter R, Daikhin Y, Nissim I, Yudkoff M, Tuchman M. N-carbamylglutamate augments ureagenesis and reduces ammonia and glutamine in propionic acidemia. Pediatrics. 2010;126:e208–e214. doi: 10.1542/peds.2010-0008. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Ah Mew N, Payan I, Daikhin Y, Nissim I, Tuchman M, Yudkoff M. Effects of a single dose of N-carbamylglutamate on the rate of ureagenesis. Mol Genet Metab. 2009;98:325–330. doi: 10.1016/j.ymgme.2009.07.010. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Daniotti M, la Marca G, Fiorini P, Filippi L. New developments in the treatment of hyperammonemia: emerging use of carglumic acid. Int J Gen Med. 2011;4:21–28. doi: 10.2147/IJGM.S10490. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Guffon N, Vianey-Saban C, Bourgeois J, Rabier D, Colombo JP, Guibaud P. A new neonatal case of N-acetylglutamate synthase deficiency treated by carbamylglutamate. J Inherit Metab Dis. 1995;18:61–65. doi: 10.1007/BF00711374. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Caldovic L, Morizono H, Daikhin Y, et al. Restoration of ureagenesis in N-acetylglutamate synthase deficiency by N-carbamylglutamate. J Pediatr. 2004;145:552–554. doi: 10.1016/j.jpeds.2004.06.047. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Caldovic L, Ah Mew N, Shi D, Morizono H, Yudkoff M, Tuchman M. N-acetylglutamate synthase: structure, function and defects. Mol Genet Metab. 2010;100(Suppl 1):S13–S19. doi: 10.1016/j.ymgme.2010.02.018. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Bachmann C, Krahenbuhl S, Colombo JP, Schubiger G, Jaggi KH, Tonz O. N-acetylglutamate synthetase deficiency: a disorder of ammonia detoxication. N Engl J Med. 1981;304:543. doi: 10.1056/NEJM198102263040918. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Bachmann C, Colombo JP, Jaggi K. N-acetylglutamate synthetase (NAGS) deficiency: diagnosis, clinical observations and treatment. Adv Exp Med Biol. 1982;153:39–45. doi: 10.1007/978-1-4757-6903-6_6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Tuchman M, Caldovic L, Daikhin Y, et al. N-carbamylglutamate markedly enhances ureagenesis in N-acetylglutamate deficiency and propionic acidemia as measured by isotopic incorporation and blood biomarkers. Pediatr Res. 2008;64:213–217. doi: 10.1203/PDR.0b013e318179454b. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Haberle J, Schmidt E, Pauli S, et al. Mutation analysis in patients with N-acetylglutamate synthase deficiency. Hum Mutat. 2003;21:593–597. doi: 10.1002/humu.10216. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Rogozin IB, Milanesi L. Analysis of donor splice sites in different eukaryotic organisms. J Mol Evol. 1997;45:50–59. doi: 10.1007/pl00006200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Ah Mew N, Caldovic L. N-acetylglutamate synthase deficiency: an insight into the genetics, epidemiology, pathophysiology, and treatment. The Application of Clinical Genetics. 2011;4:127–135. doi: 10.2147/TACG.S12702. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Haberle J. Role of carglumic acid in the treatment of acute hyperammonemia due to N-acetylglutamate synthase deficiency. Ther Clin Risk Manag. 2011;7:327–332. doi: 10.2147/TCRM.S12703. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Batshaw ML, Msall M, Beaudet AL, Trojak J. Risk of serious illness in heterozygotes for ornithine transcarbamylase deficiency. J Pediatr. 1986;108:236–241. doi: 10.1016/s0022-3476(86)80989-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Msall M, Monahan PS, Chapanis N, Batshaw ML. Cognitive development in children with inborn errors of urea synthesis. Acta Paediatr Jpn. 1988;30:435–441. doi: 10.1111/j.1442-200x.1988.tb02534.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Uchino T, Endo F, Matsuda I. Neurodevelopmental outcome of long-term therapy of urea cycle disorders in Japan. J Inherit Metab Dis. 1998;21(Suppl 1):151–159. doi: 10.1023/a:1005374027693. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Bachmann C. Long-term outcome of patients with urea cycle disorders and the question of neonatal screening. Eur J Pediatr. 2003;162(Suppl 1):S29–S33. doi: 10.1007/s00431-003-1347-z. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Batshaw ML, Roan Y, Jung AL, Rosenberg LA, Brusilow SW. Cerebral dysfunction in asymptomatic carriers of ornithine transcarbamylase deficiency. N Engl J Med. 1980;302:482–485. doi: 10.1056/NEJM198002283020902. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Gyato K, Wray J, Huang ZJ, Yudkoff M, Batshaw ML. Metabolic and neuropsychological phenotype in women heterozygous for ornithine transcarbamylase deficiency. Ann Neurol. 2004;55:80–86. doi: 10.1002/ana.10794. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Gropman AL, Batshaw ML. Cognitive outcome in urea cycle disorders. Mol Genet Metab. 2004;81(Suppl 1):S58–S62. doi: 10.1016/j.ymgme.2003.11.016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Corne CFA, Aquaviva C, Besson G. First French case of NAGS deficiency. 20 years of follow up. Mol Genet Metab. 2011;102:237–324. [Google Scholar]

- 35.Gessler P, Buchal P, Schwenk HU, Wermuth B. Favourable long-term outcome after immediate treatment of neonatal hyperammonemia due to N-acetylglutamate synthase deficiency. Eur J Pediatr. 2010;169:197–199. doi: 10.1007/s00431-009-1006-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Nordenstrom A, Halldin M, Hallberg B, Alm J. A trial with N-carbamylglutamate may not detect all patients with NAGS deficiency and neonatal onset. J Inherit Metab Dis. 2007;30:400. doi: 10.1007/s10545-007-0454-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Grody WW, Chang RJ, Panagiotis NM, Matz D, Cederbaum SD. Menstrual cycle and gonadal steroid effects on symptomatic hyperammonaemia of urea-cycle-based and idiopathic aetiologies. J Inherit Metab Dis. 1994;17:566–574. doi: 10.1007/BF00711592. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Guffon N, Schiff M, Cheillan D, Wermuth B, Haberle J, Vianey-Saban C. Neonatal hyperammonemia: the N-carbamoyl-L-glutamic acid test. J Pediatr. 2005;147:260–262. doi: 10.1016/j.jpeds.2005.04.059. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Schmidt E, Nuoffer JM, Haberle J, et al. Identification of novel mutations of the human N-acetylglutamate synthase gene and their functional investigation by expression studies. Biochim Biophys Acta. 2005;1740:54–59. doi: 10.1016/j.bbadis.2005.02.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Belanger-Quintana A, Martinez-Pardo M, Garcia MJ, et al. Hyperammonaemia as a cause of psychosis in an adolescent. Eur J Pediatr. 2003;162:773–775. doi: 10.1007/s00431-002-1126-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Heckmann M, Wermuth B, Haberle J, Koch HG, Gortner L, Kreuder JG. Misleading diagnosis of partial N-acetylglutamate synthase deficiency based on enzyme measurement corrected by mutation analysis. Acta Paediatr. 2005;94:121–124. doi: 10.1111/j.1651-2227.2005.tb01799.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Haberle J, Denecke J, Schmidt E, Koch HG. Diagnosis of N-acetylglutamate synthase deficiency by use of cultured fibroblasts and avoidance of nonsense-mediated mRNA decay. J Inherit Metab Dis. 2003;26:601–605. doi: 10.1023/a:1025912417548. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Caldovic L, Morizono H, Panglao MG, Cheng SF, Packman S, Tuchman M. Null mutations in the N-acetylglutamate synthase gene associated with acute neonatal disease and hyperammonemia. Hum Genet. 2003;112:364–368. doi: 10.1007/s00439-003-0909-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Takanashi J, Barkovich AJ, Cheng SF, et al. Brain MR imaging in neonatal hyperammonemic encephalopathy resulting from proximal urea cycle disorders. AJNR Am J Neuroradiol. 2003;24:1184–1187. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Elpeleg O, Shaag A, Ben-Shalom E, Schmid T, Bachmann C. N-acetylglutamate synthase deficiency and the treatment of hyperammonemic encephalopathy. Ann Neurol. 2002;52:845–849. doi: 10.1002/ana.10406. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Forget PP, van Oosterhout M, Bakker JA, Wermuth B, Vles JS, Spaapen LJ. Partial N-acetyl-glutamate synthetase deficiency masquerading as a valproic acid-induced Reye-like syndrome. Acta Paediatr. 1999;88:1409–1411. doi: 10.1080/080352599750030194. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Plecko B, Erwa W, Wermuth B. Partial N-acetylglutamate synthetase deficiency in a 13-year-old girl: diagnosis and response to treatment with N-carbamylglutamate. Eur J Pediatr. 1998;157:996–998. doi: 10.1007/s004310050985. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Morris AA, Richmond SW, Oddie SJ, Pourfarzam M, Worthington V, Leonard JV. N-acetylglutamate synthetase deficiency: favourable experience with carbamylglutamate. J Inherit Metab Dis. 1998;21:867–868. doi: 10.1023/a:1005478904186. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Hinnie J, Colombo JP, Wermuth B, Dryburgh FJ. N-Acetylglutamate synthetase deficiency responding to carbamylglutamate. J Inherit Metab Dis. 1997;20:839–840. doi: 10.1023/a:1005344507536. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Vockley J, Vockley CM, Lin SP, et al. Normal N-acetylglutamate concentration measured in liver from a new patient with N-acetylglutamate synthetase deficiency: physiologic and biochemical implications. Biochem Med Metab Biol. 1992;47:38–46. doi: 10.1016/0885-4505(92)90006-k. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Burlina AB, Bachmann C, Wermuth B, et al. Partial N-acetylglutamate synthetase deficiency: a new case with uncontrollable movement disorders. J Inherit Metab Dis. 1992;15:395–398. doi: 10.1007/BF02435986. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Pandya AL, Koch R, Hommes FA, Williams JC. N-acetylglutamate synthetase deficiency: clinical and laboratory observations. J Inherit Metab Dis. 1991;14:685–690. doi: 10.1007/BF01799936. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Elpeleg ON, Colombo JP, Amir N, Bachmann C, Hurvitz H. Late-onset form of partial N-acetylglutamate synthetase deficiency. Eur J Pediatr. 1990;149:634–636. doi: 10.1007/BF02034751. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Bachmann C, Brandis M, Weissenbarth-Riedel E, Burghard R, Colombo JP. N-acetylglutamate synthetase deficiency, a second patient. J Inherit Metab Dis. 1988;11:191–193. doi: 10.1007/BF01799871. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Schubiger G, Bachmann C, Barben P, Colombo JP, Tonz O, Schupbach D. N-acetylglutamate synthetase deficiency: diagnosis, management and follow-up of a rare disorder of ammonia detoxication. Eur J Pediatr. 1991;150:353–356. doi: 10.1007/BF01955939. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]