Abstract

Panax notoginseng saponins (PNS) are one of the most important compounds derived from roots of the herb Panax notoginseng which are traditionally used as a hemostatic medicine to control internal and external bleeding in China for thousands of years. To date, at least twenty saponins were identified and some of them including notoginsenoside R1, ginsenoside Rb1, and ginsenoside Rg1 were researched frequently in the area of cardiovascular protection. However, the protective effects of PNS on cardiovascular diseases based on experimental studies and its underlying mechanisms have not been reviewed systematically. This paper reviewed the pharmacology of PNS and its monomers Rb1, Rg1, and R1 in the treatment for cardiovascular diseases.

1. Introduction

Sanchi, also known as radix notoginseng, is a Chinese herbal medicine (CHM) prepared from roots of the herb Panax notoginseng (see Figure 1). It is traditionally used as a hemostatic medicine to control internal and external bleeding in China for thousands of years. According to the theory of traditional Chinese medicine, Sanchi is sweet, bitter in flavor, and enters the “heart,” “pericardium,” and “liver” channels which function in activating blood circulation of the whole body. With the increasing attention to complementary and alternative medicine, natural products have been clinically used worldwide for the treatment of cardiovascular diseases (CVDs) due to their vasodilatory and antihypertensive actions with good effect. Currently, Sanchi as a commonly used herb for stanch bleeding, invigorating, and supplementing blood has been used for treating CVDs. It is gaining attention increasingly both in developing and in developed countries, including the United States, Japan, and Korea for its efficacy and lower adverse effects. Moreover, it has function of myocardial protection, especially for improving ischemia/reperfusion- (I/R-) induced injury after percutaneous coronary interventional therapy [1].

Figure 1.

Morphology of Radix notoginseng. (a) Whole plant; (b) roots for pharmaceutical use.

The chemical constituents of radix notoginseng are complex. As early as the 1930s, some scholars began to study the chemical constituents of radix notoginseng but had slow progress. To the 1970s, with the development of modern test science and technology, this field of research had achieved more and more significant results. Modern researches had showed that radix notoginseng consisted of saponin, dencichine, polysaccharides, amino acids, flavonoids, phytosterols, fatty acids, volatile oils, aliphatic acetylene hydrocarbons, and trace elements [2]. Panax notoginseng saponins (PNS) are one of the main active ingredients of Panax. To date, twenty-seven saponins were identified and nine of them including notoginsenoside R1, ginsenoside Rb1, Rb2, Rb3, Rc, Rd, Re, Rf, and Rg1 were quantified from different parts of Panax [3]. Most of these monomer components are 20(S)-protopanaxadiol and 20(S)-protopanaxatriol. But oleanolic acid-type saponins were not found, which was different from the same plant ginseng and American ginseng [4]. There are also a lot of same monomers compared with ginseng and American ginseng saponins, such as ginsenosides Rb1, Rb2, Rb3, Rc, Rd, Re, and gypenoside. Among them, the content of Rg1 and Rb1 is higher, as the main saponins of radix notoginseng [5]. Ginsenoside Rb1 can promote the formation of nerve fibers and maintain its function to prevent sexual dysfunction, depress central nervous system, promote serum protein synthesis, promote cholesterol synthesis and decomposition, and inhibit the decomposition of neutral fat and antihemolytic reaction [6]. Ginsenoside Rg1 can excite central nervous system, prevent sexual dysfunction, enhance memory, eliminate fatigue, promote DNA and RNA synthesis, and inhibit platelet aggregation [7]. Physiological activity of ginsenoside Rc is mainly inhibiting the central nervous system, so that may cause nerve trance phenomena. Compared with ginseng and American ginseng, Panax consists of more Rb1 and Rg1, but without Rc. Therefore, taking Panax has kind of strong tonic effect, without the ginseng-induced trance-like effect [8].

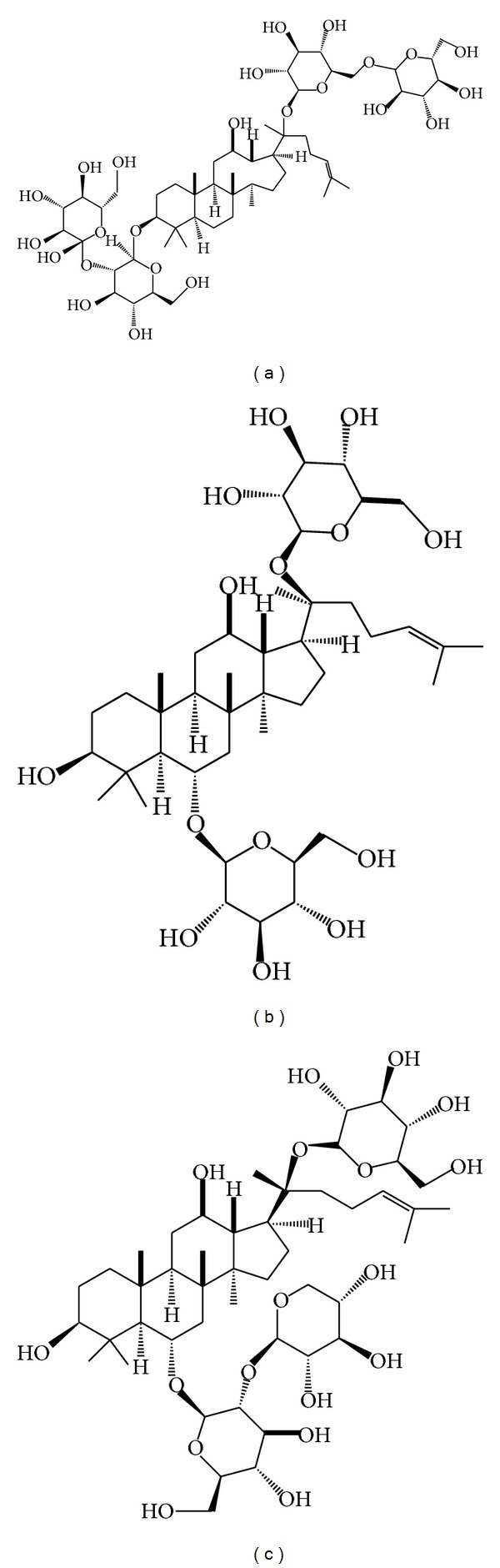

Although the incidence of CVDs is increasing rapidly with the infectious diseases controlled and improvement of people's living, CVDs are still the leading problem for human health [9]. Recently, there is a growing and sustained interest in the benefits of herbal monomer and potential drug interactions with western medications, especially for patients with CVDs for safety and fewer side effects. Protective functions of PNS on the cardiovascular system include inhibition of platelet aggregation, increasing blood flow, improving left ventricular diastolic function in hypertensive patients, and anti-inflammatory effect. These biomarkers are the potential clinical therapeutic targets for cardiovascular disease. The chemical structures of PNS (Rb1, Rg1, and R1) are shown in Figure 2. This paper reviewed the pharmacology of PNS and its monomers Rb1, Rg1, and R1 in the treatment for cardiovascular diseases.

Figure 2.

Main compounds of Panax notoginseng saponins. (a) Ginsenoside Rb1; (b) ginsenoside Rg1; (c) ginsenoside R1.

2. Cardiovascular Pharmacology

2.1. Antiplatelet and Anticoagulant Effect

Long-term antithrombotic therapies, namely, oral antiplatelet agents and anticoagulants, have demonstrated variable clinical effects in cardiovascular diseases, such as coronary heart disease (CHD), hypertension, heart failure, atrial fibrillation, and valvulopathy. Aspirin has been shown to reduce the risk for thrombosis and ischaemic events. However, the possibility of aspirin resistance, which has been described as a number of phenomena, including antithrombotic complications, prolongation of the bleeding time, and inhibition of thromboxane biosynthesis [10], provides an impetus for researching new antiplatelet products with high effectiveness and fewer adverse effects. Sanchi is considered a good source of lead compounds for novel antiplatelet and anticoagulant therapeutics. Notoginsengnosides (NG) isolated from Sanchi could inhibit both the platelet aggregation of platelet rich plasma (PRP) and washed platelet after ADP induction. In the NG-treated platelets, the levels of growth factor receptor-bound protein 2 (Grb2), thrombospondin 1, and tubulin alpha 6 were increased, whereas the levels of thioredoxin, Cu-Zn superoxide dismutase, DJ-1 protein, peroxiredoxin 3, thioredoxin-like protein 2, ribonuclease inhibitor, potassium channel subfamily V member 2, myosin regulatory light chain 9, and laminin receptor 1 were decreased [11]. The analysis of the reactive oxygen species (ROS) level also indicated that NG could decrease the ROS level in platelets. Both raw and steamed Panax notoginseng can significantly inhibit platelet aggregation and plasma coagulation. In addition, steamed Panax notoginseng has significantly more potent antiplatelet and anticoagulant effects than the raw extract, and the antiplatelet and anticoagulant effects increase with increasing steaming durations. Another research [12] demonstrated that the antiplatelet and anticoagulant effects in vitro are positively translated into a prolongation of in vivo rat bleeding time after oral administration of the raw and steamed extracts. Other studies also reported that notoginsenoside R1 (NG-R1) increases the synthesis of tissue-type plasminogen activator (t-PA) and decreases plasminogen activator inhibitor-1 (PAI-1) activity in cultured human endothelial cells from different vascular sources. NG-R1 could increase the fibrinolytic potential in vitro by increasing the production of t-PA and u-PA [13]. This potential effect of NG-R1 on the improvement of fibrinolytic system might contribute to the effect of the Chinese herb drug Panax notoginseng in the treatment of cardiovascular diseases.

2.2. Protecting Myocardium Cells from Apoptosis

Increased cardiomyocyte apoptosis can be commonly observed in heart failure after acute myocardial ischemia (MI) [14, 15]. Oxidative stress plays a significant role in tissue necrosis and reperfusion injury during this process [16]. Protecting myocardium cells from apoptosis is a potentially promising approach to limit infarct size during the revascularization of patients with acute MI. The cardioprotective mechanism involves the reduction of oxygen-derived free radicals, prolonged acidosis during early reperfusion, and signal transductions that attenuate the multiple manifestations of reperfusion injury by inhibiting the opening of the mitochondrial permeability transition pore (mPTP), a nonspecific channel localized in the mitochondrial inner membrane [17–20]. Among the distal signal transduction pathways involved in cardioprotection, the activation of reperfusion injury salvage kinases (RISK), such as phosphatidylinositol 3-kinase- (PI3K-) Akt and ERK1/2, has been implicated in the mechanistic link between protection of cardiomyocyte apoptosis and cardioprotection [21, 22]. The protective effect and potential molecular mechanisms of PNS on apoptosis in H9c2 cells in vitro and rat myocardial ischemia injury model in vivo were investigated [23]. However, the effect was blocked in vitro by LY294002, a specific PI3K inhibitor. The antiapoptotic effect of PNS was mediated by stabilizing Deltapsim in H9c2 cells. Furthermore the indices of the left ventricular ejection fractions (EF), left ventricular fractional shortening (FS), left ventricular dimensions at end diastole (LVDd), and left ventricular dimensions at end systole (LVDs) suggested that PNS improved rats' cardiac function. They found that PNS could protect myocardial cells from apoptosis induced by ischemia in both the in vitro and the in vivo models through activating PI3K/Akt signaling pathway. In vitro study [23] also suggested that PNS has a significant effect on Ang II-induced rat cardiomyocytes apoptosis by alleviating intracellular calcium overload. It was found that incubating with Ang II (10(−7) mol × L(−1)) for 48 h increased cardiomyocyte apoptosis; PNS (25, 100 mg × mL(−1)) increased myocyte viability. PNS (50 mg × mL(−1)) significantly decreased this Ang II-induced rat cardiomyocyte apoptosis and decreased fluorescent intensity of intracellular calcium. In vitro experiments [24] assessed the protective effect of PNS against doxorubicin on viability of embryonic rat heart cell H9C2. The results showed that pretreatment with PNS significantly lowered the levels of serum LDH, CK, and CK-MB and normalized myocardial superoxide dismutase, glutathione peroxidase, and catalase activities. Another researcher [25] studied the effects of total PNS and its monomers Rb1 and Rg1 on total ATPase and Na(+)-K(+)-exchanging ATPase of guinea pig heart were studied. The results showed that PNS inhibited the total myocardial ATPase but had no significant effect on the myocardial Na(+)-K(+)-exchanging ATPase.

2.3. Promoting Cardiac Angiogenesis

Despite extensive atherosclerosis that precludes complete revascularization, an increasing number of patients are being referred for coronary artery bypass surgery [26]. A variety of novel angiogenic therapies [27–30] are being evaluated as adjuncts to bypass grafting or as sole therapies for patients who are not candidates for coronary artery bypass. Vascular endothelial growth factor (VEGF) and basic fibroblast growth factor have been given as protein therapy or as gene therapy by transfection by naked DNA or with adenoviral vectors [31, 32]. However, the limitations of growth factor therapy include the risks of systemic effects inducing problematic angiogenesis in the retina or the potentiation of growth and metastasis of occult tumors [33]. It was investigated that Radix Notoginseng formula had effects on secretion of vascular endothelial growth factor (VEGF) and expression of vascular endothelial growth factor receptor-2 (VEGFR-2) in human umbilical vein endothelial cells (HUVECs) in vitro [34]. The results showed that Radix Notoginseng formula can promote HUVEC proliferation and secretion of VEGF, as well as the expression of VEGFR-2 protein, which may be one of the mechanisms of Radix Ginseng and Radix Notoginseng formula in promoting angiogenesis with fewer adverse effects.

2.4. Antimyocardial Ischemia and Hypoxia Effect

Antimyocardial ischemia/hypoxia are still challenging for treating coronary heart diseases. It has been generally accepted that efficient therapeutic approaches to ischemic heart diseases are to improve the myocardial oxygen balance between supply and demand in the ischemic heart, by either increasing coronary blood flow or decreasing cardiac mechanical function or both [35]. The traditional antianginal drugs included nitrates, b-blockers, and calcium channel blockers, which are thought to improve the myocardial oxygen balance with changes in hemodynamic parameters. However, these drugs also bring further injury to the weak cardiac function [36]. Therefore researchers are trying to find more efficient means with fewer side effects to prevent and treat myocardial ischemia. To investigate the effects of PNS extracts on antimyocardial ischemia injuries in vivo, it was found that PNS may be therapeutically useful for ameliorating antimyocardial ischemia injuries by decreasing oxidative stress and repressing inflammatory cascade [37]. PNS restrained the oxidative stress related to myocardial ischemia injury as evidenced by decreased malondialdehyde (MDA) and elevated superoxide dismutase (SOD) activity. Meanwhile, the inflammatory cascade was inhibited as evidenced by decreased cytokines such as tumor necrosis factor-α (TNF-α), C-reactive protein (CRP) and interleukin-1β (IL-1β). Other researches [38] also studied the protective effect and mechanism of ginsenoside Rg1 in cardiomyocytes hypoxia/reoxygenation (H/R) model. The results showed that pretreatment with ginsenoside Rg1 reduced lactate dehydrogenase release and increased cell viability in a dose-dependent manner. Fluorescence analysis also demonstrated ginsenoside Rg1 reduced intracellular ROS and suppressed the intracellular [Ca(2+)] level, which suggested that the myocardial protection of ginsenoside Rg1 during H/R is partially due to its antioxidative effect and intracellular calcium homeostasis.

2.5. Lipid-Lowering Effect

Lipid-lowering medications have been shown to reduce both atherogenic lipoproteins and cardiovascular morbidity and mortality [39–43]. Although the efficacy of lipid-lowering medications (various statins) in reducing atherogenic lipoproteins and vascular inflammation varies significantly, the impact of these differences on clinical outcome is unknown [44]. Alternative strategies and target levels for lipid reduction are still an important issue for lowering the risk of cardiovascular events. To explore potential benefits in cardiovascular disorders associated with excess cholesterol and hyperlipidemia, researchers investigated the effects of Sanchi on hyperlipidemia and oxidative stress in male Sprague-Dawley rats maintained on a high-fat die, which results in a significant decline in serum levels of total cholesterol (TC), triglycerides, and low-density lipoprotein-cholesterol, with an increase in serum high-density lipoprotein-cholesterol levels [45]. In addition, the results also showed reduced levels of hepatic HMG-CoA reductase.

2.6. Inhibitory Effect on the Inflammatory Responses

Inflammatory response plays an important role in cardiovascular disease including the process of atherosclerosis, cardiac hypertrophy, endothelium injury, and myocardial infarction. Dendritic cells (DCs) play a central role in the regulation of both inflammation and adaptive immunity. Notoginseng extracts have potential ability to modulate toll-like receptor (TLR) ligand-induced activation of cultured DC2.4 cells [46]. The inhibition of TNF-alpha production was time-dependent in LPS-stimulated cells by pretreatment or concurrent treatment of notoginseng but not after delayed addition of the herbal extract. Additionally, ginsenoside Rg1 more effectively inhibited LPS-stimulated cytokine production by DC2.4 cells than ginsenoside Rb1.

2.7. Inhibition of Intimal Hyperplasia and Smooth Muscle Cell Proliferation

Abnormal proliferation of vascular smooth muscle cells (VSMCs) plays an important role in formation of atherosclerosis and restenosis. However, mechanisms underlying this effect have not been completely elucidated. Several lines of evidences demonstrated that PNS could inhibit the vascular intimal hyperplasia and the smooth muscle cell (SMC) proliferation, suppress the expression of various growth factors, and induce the differentiation, maturity, and apoptosis of the vascular smooth muscle cell (VSMC). Experiments [47, 48] indicated that PNS could inhibit vessel restenosis after vascular intimal injury, and its mechanisms may be related to the blockage of the excessive proliferation of VSMC. One research [47] showed that PNS significantly inhibited the vascular intimal hyperplasia and significantly lowered the expression of proliferating cell nuclear antigen (PCNA), cyclin E, cyclinD1, fibronect (FN), and matrix metalloproteinase-9 (MMP-9) but had no significant impacts on the expression of collagen I (Col-I) and TIMP-1. Other researches [48] showed that the intimal area (IA), intimal thickness (IT), hyperplasia ratio of intimal area (HRIA), the ratio of intimal/mesolamella area, and thickness were significantly lower after treatment with PNS in rats; meanwhile the expression of proliferating cell nuclear antigen (PCNA) was significantly lowered. Another research [49] showed the restraining impact of PNS on the proliferation of VSMCs and revealed the associated mechanisms through cell cycle-related factors and extracellular regulated protein kinase (ERK) signal transduction pathway. In addition, there were also no significant differences between atorvastatin and PNS on inhibiting the activation of PDGF-induced P-ERK1/2 and increasing the content of MKP-1. PNS both inhibits VSMCs proliferation and induces VSMCs apoptosis through upregulating p53, Bax, and caspase-3 expressions and downregulating Bcl-2 expression, which constitute the pharmacological basis of its antiatherosclerotic action [50]. PNS (100 and 400 micrograms · mL(−1)) can inhibit the proliferation of VSMC stimulated by hypercholesterolemic serum (HCS) [51]. Another research [52] concluded that PNS can significantly inhibit the VSMC proliferation induced by hyperlipidemia serum. Hyperlipidemia serum could promote VSMC proliferation, while PNS could weaken this effect significantly.

2.8. Antiatherosclerosis Effect

Atherosclerosis (AS) is a systemic cardiovascular disease with complicated pathogenesis involving vascular smooth muscle cell (VSMC) proliferation, endothelial dysfunction, lipid deposition, oxidative stress, and chronic inflammation. Endothelial dysfunction plays an important role in the formation of atherosclerosis. The unbalance between the induction of VSMC apoptosis and inhibition of VSMC apoptosis attributes the injury of endothelium. One of the most important substances for inducing VSMC apoptosis is NO, which has vasodilative effect on blood vessels. Various studies had demonstrated that PNS could attenuate atherosclerosis with different mechanisms. To investigate the effects of PNS on antioxidant effect on the formation of atherosclerosis, one research [53] showed that PNS can lower the serum levels of lipid and oxidized low-density lipoprotein (oxLDL), ratio of plaque area to vessel area, and expression of CD40 and MMP-9 in the apolipoprotein E-knockout (apoE-KO) mice. Another in vivo study showed that PNS had an effect in reversing the injuries of human umbilical vascular endothelial cells (HUVEC) induced by oxidized low-density lipoprotein (ox-LDL), improving its activity, elevating the adhesion rate with monocytes, and increasing the protein expression of intercellular adhesion molecule-1 (ICAM-1) in HUVEC [54]. It suggested that the protective effect of PNS for treating arteriosclerosis obliterans (ASO) is probably by way of downregulating the expression of ICAM-1 in endothelial cells and inhibiting the adherence of monocytes to endothelial cells. PNS attenuates atherogenesis through an anti-inflammatory action of decreasing the mRNA expression levels of monocyte chemoattractant protein-1 and nuclear factor-kappaB/p65 in the aorta wall after 8 weeks of treatment in rabbits, and regulation of the blood lipid profile includes decreasing the serum levels of TC, triglyceride, low-density lipoprotein-cholesterol, interleukin-6, and C-reactive protein as well as increasing high-density lipoprotein-cholesterol level significantly [55]. PNS enhanced transcriptional activation of the LXRalpha gene promoter, subsequently upregulated ATP-binding cassette A1 and G1 (ABCA1, ABCG1), and inhibited NF-kappaB DNA binding activity in rat aortas [56]. Accumulative studies had been established to investigate the anti-inflammatory effect on atherosclerosis. The molecular mechanisms responsible for the antiatherosclerotic effects of PNS and the inflammatory response were explored [57]. The results suggested that PNS exerts its therapeutic effects on atherosclerosis through an anti-inflammatory action, including reduction of the gene expression of some inflammatory factors, such as integrins, interleukin- (IL-)18, IL-1beta and matrix metalloproteinases-2 (MMP-2), and MMP-9. In addition, PNS was found to increase the expression of IkappaBalpha, whereas attenuating the expression of NF-kappaB/p65, suggesting that the possible mechanism responsible for the effect of PNS was associated with NF-kappaB signalling pathway, which was accompanied with inflammatory response. PNS inhibits zymosan A induced atherogenesis by suppressing phosphorylation of FAK on threonine 397, integrins expression, and NF-kappaB translocation in rats [58]. The similar trend of the inhibitory effects of PNS and its two major individual ingredients, ginsenoside Rg1 and ginsenoside Rb1, on the TNF-alpha-induced NF-kappaB activation was investigated in human coronary artery endothelial cells (HCAECs) [59]. PNS can promote angiogenesis by regulating the VEGF-KDR/Flk-1 and PI3K-Akt-eNOS signaling pathways in human umbilical vein endothelial cells (HUVECs) [60]. In addition, PNS was also shown to promote changes in the subintestinal vessels in zebrafish as a feature of antiangiogenesis effect.

2.9. Antiarrhythmia Effect

Atrial arrhythmia (AA) is the most common complication after coronary artery bypass grafting (CABG). In addition to potentially increased risk of stroke and death, patients with recurrent or persistent AA require additional medications, including systemic anticoagulation [61, 62]. Several pharmacologic agents have been used to prevent AA. Rg1 isolated from saponins of Panax notoginseng had effects on cardiac electrophysiological properties and ventricular fibrillation threshold (VFT) in open-chest dogs [63]. The result showed that Rg1 prolonged sinus node recovery time (SNRT) by 19.1%, AV conduction Wenckebach cycle length (AVWCL) by 7.1%, and ventricular effective refractory period (VERP) by 7.9%, while increased VFT by 19.2%. The cardiac electrophysiological effects of Rg1 were similar to those of amiodarone.

2.10. Vasodilative Effect

Hypertension, as an independent predisposing factor for heart failure, coronary artery disease, stroke, renal disease, and peripheral arterial disease, is associated with serious morbidity and mortality [64]. Evaluation of possible resistant hypertension begins with an assessment of adherence to medications. To investigate the inhibition of endothelium-dependent abnormalityin vascular relaxation induced by PNS and its effect on receptor-operated Ca2+ channels in vascular smooth muscle, at least three experiments have been established. One research [65] suggested that PNS could increase Ca2+ level in endothelial cells via the receptor-operated Ca2+ channels in the presence of acetylcholine (ACh) or the nonselective cation channels opened by cyclopiazonic acid (CPA). Another research [66] indicated that ginsenoside-Rd could remarkably inhibit Ca2+ entry through receptor-operated calcium channel (ROCC) and store-operated calcium channel (SOCC) without effects on voltage-dependent inward Ca2+ current (VDCC) and Ca2+ release in vascular smooth muscle cells. Ginsenoside-Rd inhibited cell proliferation and reversed basilar artery remodeling [67], while Rb1 and Rg1 increased endothelial-dependent vessel dilatation through the activation of NO by modulating the PI3K/Akt/eNOS pathway and l-arginine transport in endothelial cell [68].

2.11. Inhibition of Left Ventricular Remodeling

Left ventricular remodeling can be caused by acute myocardial infarction and then lead to heart failure. Increase in left ventricular mass (LVM) might be an important pathological process for cardiovascular diseases including hypertension and heart failure. Several factors which are associated with increased LVM have been identified, which include blood pressure, physical activity, and blood viscosity [69, 70]. To investigate the effects of PNS on the overall model and in vitro model of cardiac hypertrophy, it was found that PNS inhibited the markers of cardiac hypertrophy including heart weight/body weight (HW/BW), left ventricular weight/body weight (LVW/BW), and the myofibril diameters (MD) in rats in a dose-dependent manner, but SBP of rats was not obviously influenced [71]. PNS significantly inhibited the norepinephrine (NE) induced increase of surface area and protein content in the cultured myocardial cells, indicating that PNS can prevent the overall model and in vitro model of cardiac hypertrophy in rats associated with its inhibitory action on neurohormonal factor NE, but not on pressure overload. A comparative study [72] was conducted on the action of PNS and captopril in treating SHR. The results demonstrate that PNS helps increase the effect of calcium pump on the membrane of sarcoplasmic reticulum, decrease the myocardial intracellular Ca2+, and reduce the mass of the left ventricular muscle. To research the effects of Panax notoginseng saponins (PNS) on angiotensin-converting enzymes 2 (ACE2) and tumor necrosis factor-alpha (TNF-alpha) in rats with postmyocardial infarction ventricular remodeling, it was concluded that PNS can stimulate ACE2 to inhibit the expression of TNF-alpha and enhance the antioxidants. In addition, PNS can reduce pathological injury of cardiac myocytes in myocardial ischemia and cardiac muscle, which can improve ventricular remodeling [73].

3. Conclusion

Cardiovascular disease (CVD) is a major cause of early morbidity and mortality in most developed countries, which is caused by atherosclerosis mainly, and is always treated by western routine drugs for reducing the risk of heart attack and emergency medical care [74]. During the most recent decade, the rate of death due to CVD has declined, but the burden of disease remains high. Although improved medical care and acute management of myocardial infarction have led to a considerable reduction of early mortality rate survivors, an increased prevalence of secondary diseases such as chronic heart failure caused by ventricular remodeling decreased the benefit of medical care [75, 76]. An enormous cost factor for the healthcare system that cardiovascular operations and interventional procedures increased by 28% from 2000 to 2010 was implicated [77]. Therefore, the main issue of current pharmacological, interventional, or operative therapies is their disability to reduce the risk factors and endpoints of cardiovascular diseases. Recently, there is a growing and sustained interest in the benefits of complementary herbal medicine (CHM) and potential drug interactions with western medications, especially for patients with CVD for safety and fewer adverse effects. In China, the research field of integration of traditional and western medicine in treating CVD is developing rapidly for over 30 years. Among them, issue on the blood stasis syndrome (BBS) and promoting blood circulation and removing blood stasis (PBCRBS) is one of the most developed fields of integration of traditional and western medicine. The research development of herbal extracts, herbal single monomer, and traditional Chinese patent medicine (TCPM) is increasing rapidly, especially in integration with routine western medical interventions [78–82]. For instance, at least one TCPM may regularly be used in patients with angina pectoris after percutaneous coronary intervention (PCI) in either western medicine hospitals or traditional Chinese medicine hospitals, because it shows the ability to ameliorate in-stent restenosis after PCI [83].

Several lines of evidence have proved that PNS appears to be a promising natural cardioprotective agent. PNS, which is a member of the major lipophilic components extracted from Panax notoginseng, has indicated significant therapeutic effects and multiple pharmacological actions including antiplatelet, anticoagulant, antithrombotic, antiatherosclerosis, lipid-lowering, vasodilative, anti-inflammation, antiischemia, antiarrhythmia, antihyperplasia, and promoting angiogenesis effects. The identified effect of PNS and its major monomers is summarized in Tables 1 and 2. All that demonstrated that PNS can regulate whole body by acting on multicenter and multitargets for protection. However, there are still some problems existing in the research of PNS for cardiovascular diseases. (1) In the most experimental researches, they focused on the mechanisms of one aspect of PNS, the experimental design owes rigor, and only a few studies were equipped in vitro and in vivo at the same design. (2) Research on antiplatelet and anticoagulant effect and antiatherosclerosis effect was adequate and performed more frequently compared with other effects of studies. However, studies about antiarrhythmic effect and lipid-lowering effect are seldom in vivo or in vitro. For vasodilative effect, there is deficiency of in vivo research to investigate blood pressure lowering induced by PNS. As hypertension is an independent predisposing factor for heart failure, coronary artery disease, stroke, renal disease, and peripheral arterial disease, evaluation of possible resistant hypertension begins with an assessment of adherence to medications. (3) Despite the fact that there were randomized controlled trials (RCTs) about PNS, for instance, Xuesaitong soft capsule and Xuesaitong injection for treating coronary heart diseases, but the methodological and qualities of these kinds of RCTs were not vigorous, it is imperative to conduct multicentered, large-sized samples and randomized and arid controlled trials to reasonably evaluate the efficacy and safety of PNS for CVDs. In addition, there are also short of systematic reviews (SRs) about PNS.

Table 1.

Cardiovascular effects of PNS (Rb1, Rg1, and R1) in vitro research.

| Compounds | Cells/tissues | Effects | Study | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| NG | PRP and rat washed platelets | Antiplatelet, anticoagulant, and antithrombotic effect | (i) Inhibit ADP-induced platelet aggregation | Yao et al., 2008 [3] |

| NG | Rat washed platelets | (ii) Increase the levels of Grb2, thrombospondin 1, and tubulin alpha 6 and decrease the levels of thioredoxin, Cu-Zn superoxide dismutase, DJ-1 protein, peroxiredoxin 3, thioredoxin-like protein 2, ribonuclease inhibitor, potassium channel subfamily V member 2, myosin regulatory light chain 9, and laminin receptor 1 | Yao et al., 2008 [3] | |

| (iii) Decrease the ROS level | ||||

| NG-R1 | Cultured human endothelial cells from different vascular sources | (iv) Increase the synthesis of t-PA and decrease PAI-1 activity | Zhang et al., 1997 [12] | |

|

| ||||

| PNS | H9c2 cells | Protecting myocardium cells from apoptosis | (i) Activate PI3K/Akt signaling pathway | Chen et al., 2011 [13] |

| PNS | H9c2 cells | (ii) Lower the levels of serum LDH, CK, and CK-MB and normalize myocardial superoxide dismutase, glutathione peroxidase, and catalase activities | Shi et al., 2007 [24] | |

| PNS | Cultured cardiomyocytes | (iii) Alleviate intracellular calcium overload | Chen et al., 2005 [23] | |

|

| ||||

| Radix notoginseng formula | HUVEs | Promoting cardiac angiogenesis | Promote HUVEC proliferation and secretion of VEGF, expression of VEGFR-2 protein | Lei et al., 2010 [34] |

|

| ||||

| Ginsenoside Rg1 | Rat cardiomyocyte H/R model | Antimyocardial ischemia and hypoxia effect | Reduce lactate dehydrogenase release and increased cell viability and reduce intracellular ROS and suppressed the intracellular [Ca(2+)] level | Zhu et al., 2009 [38] |

|

| ||||

| Notoginseng extracts (ginsenoside Rg1 and ginsenoside Rb1) | DCs 2.4 cells | Inhibitory effect on the inflammatory responses | Inhibition of TNF-alpha production and inhibit LPS-stimulated cytokine production | Rhule et al., 2008 [46] |

|

| ||||

| PNS | VSMCs | Inhibition of intimal hyperplasia and smooth muscle cell proliferation | (i) Inhibit the activation of PDGF-induced P-ERK1/2 and increase the content of MKP-1 | Zhang et al., 2012 [49] |

| PNS | VSMCs | (ii) Upregulate p53, Bax, and caspase-3 expressions and downregulate Bcl-2 expression | Xu et al., 2011 [50] | |

| PNS | VSMCs | (iii) Inhibit the VSMC proliferation induced by hyperlipidemia serum | Lin et al., 1993 [51] | |

| PNS | VSMCs | (iv) Inhibit the VSMC proliferation induced by hyperlipidemia serum | Wang et al., 2006 [8] | |

|

| ||||

| PNS | ApoE-KO mice | Antiatherosclerosis effect | (i) Lower the serum levels of lipid and oxLDL, ratio of plaque area to vessel area, and expression of CD40 and MMP-9 | Liu et al., 2009 [53] |

| PNS | HUVEC | (ii) Improve its activity, elevate the adhesion rate with monocytes, and increase the protein expression of ICAM-1 | Qin et al., 2008 [54] | |

| (iii) Decrease the mRNA expression levels of monocyte chemoattractant protein-1 and nuclear factor-kappaB/p65 | Liu et al., 2010 [55] | |||

| PNS, ginsenoside Rg1, and ginsenoside Rb1 | HCAECs | (iv) Inhibit TNF-alpha-induced NF-kappaB activation | Wang et al., 2011 [59] | |

| PNS | HUVECs | (v) Regulate the VEGF-KDR/Flk-1 and PI3K-Akt-eNOS signaling pathways | Hong et al., 2009 [60] | |

|

| ||||

| PNS | Endothelial cells | Vasodilative effect | (i) Increase of Ca2+ level via the receptor-operated Ca2+ channels in the presence of ACh or the nonselective cation channels opened by CPA | C. Y. Kwan, and T. K. Kwan, 2000 [65] |

| Ginsenoside-Rd | VSMCs | (ii) Inhibit Ca2+ entry through ROCC and SOCC without effects on VDCC and Ca2+ release | Guan et al., 2006 [66] | |

| Ginsenoside-Rd | BASMCs | (iii) Inhibit cell proliferation and reverse basilar artery remodeling | Li et al., 2012 [67] | |

| Rb1 and Rg1 | Endothelial cell | (iv) Increase endothelial-dependent vessel dilatation through the activation of NO by modulating the PI3K/Akt/eNOS pathway and l-arginine transport | Pan et al., 2012 [68] | |

|

| ||||

| PNS | Cultured myocardial cells | Inhibition of left ventricular remodeling | Inhibitory action on neurohormonal factor NE | Zhou et al., 2005 [71] |

NG: notoginsengnosides; NG-R1: notoginsenoside R1; H/R: hypoxia/reoxygenation; DCs: dendritic cells; VSMCs: vascular smooth muscle cells; apoE-KO: apolipoprotein E-knockout; HUVEC: human umbilical vascular endothelial cells; HCAECs: human coronary artery endothelial cells; BASMCs: basilar artery smooth muscle cells; PRP: platelet rich plasma; Grb2: growth factor receptor-bound protein 2; ROS: reactive oxygen species; t-PA: plasminogen activator; PAI-1: plasminogen activator inhibitor-1; oxLDL: oxidized low density lipoprotein; ICAM-1: intercellular adhesion molecule-1; Ach: acetylcholine; CPA: cyclopiazonic acid; ROCC: receptor-operated; SOCC: store-operated; VDCC: voltage-dependent inward Ca2+ current.

Table 2.

Cardiovascular effects of PNS (Rb1, Rg1, and R1) in vivo research.

| Compounds | Organ/animals | Effects | Study | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Raw and steamed extracts | Rats blood | Antiplatelet, anticoagulant, and antithrombotic effect protecting myocardium cells from apoptosis |

(i) Prolong rat bleeding time | Lau et al., 2009 [11] |

| PNS | Rats heart | (ii) Activate PI3K/Akt signaling pathway and improve the left ventricular EF, left ventricular FS, LVDd, and LVDs at end systole | Chen et al., 2011 [13] | |

| PNS (Rb1, Rg1) | Guinea pig heart | (iii) Inhibit the total myocardial ATPase | Chen et al., 1994 [25] | |

|

| ||||

| PNS | SD rats | Antimyocardial ischemia and hypoxia effect | Decrease MDA and elevated SOD activity and decrease cytokines such as TNF-α, CRP, and IL-1β | Han et al., 2013 [37] |

|

| ||||

| Radix Notoginseng | Sprague-Dawley rats | Lipid-lowering effect | Decline in serum levels of TC, triglycerides, and low-density lipoprotein-cholesterol, with an increase in serum high-density lipoprotein-cholesterol levels; reduced levels of hepatic HMG-CoA reductase | Xia et al., 2011 [45] |

|

| ||||

| Panax notoginseng root | Sprague-Dawley rats | Inhibition of Intimal Hyperplasia and smooth muscle cell proliferation | (i) Inhibit the vascular intimal hyperplasia and lower the expression of PCNA, cyclin E, cyclinD1, FN, and MMP-9 | Wu et al., 2010 [47] |

| PNS | Rats heart | (ii) Lower the IA, IT, HRIA, the ratio of intimal/mesolamella area and thickness, and the expression of PCNA | Wang et al., 2009 [48] | |

|

| ||||

| PNS | Rabbits | Antiatherosclerosis effect | (i) Decrease the mRNA expression levels of monocyte chemoattractant protein-1 and nuclear factor-kappaB/p65 in the aorta wall after 8 weeks of treatment in rabbits and regulate the blood lipid profile | Liu et al., 2010 [55] |

| PNS | Rats heart | (ii) Enhance transcriptional activation of the LXRalpha gene promoter, subsequently upregulated of ABCA1 and ABCG1, and inhibit NF-kappaB DNA binding activity | Fan et al., 2012 [56] | |

| PNS | Rats | (iii) Reduce the gene expression of some inflammatory factors, such as integrins, IL-18, IL-1beta, and matrix MMP-2 and MMP-9, increase the expression of IkappaBalpha, and attenuate the expression of NF-kappaB/p65 | Zhang et al., 2008 [57] | |

| PNS | Rats | (iv) Suppress phosphorylation of FAK on threonine 397, integrins expression, and NF-kappaB translocation | Yuan et al., 2011 [58] | |

| PNS | Zebrafish | (v) Promote changes in the subintestinal vessels | Hong et al., 2009 [60] | |

|

| ||||

| Rg1 | Open-chest dogs | Antiarrhythmia effect | Prolong SNRT, AVWCL, and VERP and increase VFT | Wu et al., 1995 [63] |

|

| ||||

| PNS | Rats | Inhibition of left ventricular remodeling | (i) Inhibit the markers of cardiac hypertrophy including HW/BW, LVW/BW, and the MD | Zhou et al., 2005 [71] |

| PNS | SHR | (ii) Increase the effect of calcium pump on the membrane of sarcoplasmic reticulum, decrease the myocardial intracellular Ca2+, and reduce the mass of the left ventricular muscle | Feng and Jiang, 1998 [72] | |

| PNS | Rats | (iii) Stimulate ACE2 to inhibit the expression of TNF-alpha and enhance the antioxidance | Guo et al., 2010 [73] | |

EF: ejection fractions; FS: fractional shortening; LVDd: left ventricular dimensions at end diastole; LVDs: left ventricular dimensions; MDA: malondialdehyde; SOD: superoxide dismutase; TNF-α: tumor necrosis factor-α; CRP: C-reactive protein; IL-1β: interleukin-1β; TC: total cholesterol; IA: intimal area; IT: intimal thickness; HRIA: hyperplasia ratio of intimal area; PCNA: proliferating cell nuclear antigen; ABCA1: ATP-binding cassette A1; ABCG1: ATP-binding cassette G1; IL: interleukin; MMP-2: metalloproteinases-2; SNRT: sinus node recovery time; AVWCL: AV conduction Wenckebach cycle length; VERP: ventricular effective refractory period; VFT: increase ventricular fibrillation threshold; HW/BW: weight/body weight; LVW/BW: left ventricular weight/body weight; MD: myofibril diameters.

In future research for PNS or another CHM for CVDs, it is necessary to take a systematic study on the mechanism of Chinese herb and formulas for PBCRBS. We could suggest that PNS is an important herbal medicine for cardiovascular protection; nevertheless, it could also be used as an antihypertensive agent on the basis of our clinical experience. It has been proved that PNS has an effect on reversing ventricular hypertrophy, protecting target organs, improving blood vessel function, and other auxiliary vasodilator effects. Therefore, further in vivo researches are needed to explore and verify the potential effect to provide precise guidance for clinical use and new drug discovery. Meanwhile, more rigorous studies could be performed to prove the efficacy of PNS for treating cardiovascular diseases by translating these pharmaceutical effects into clinical practice, in order to indicate its multitarget actions and finally improve clinical efficacy.

Acknowledgments

The current work was partially supported by the National Basic Research Program of China (973 Program, no. 2003CB517103) and the National Natural Science Foundation Project of China (no. 90209011). The funders had no role in study design, data collection and analysis, decision to publish, or preparation of the paper.

Conflict of Interests

All authors declare that they have no conflict of interests.

Authors' Contribution

Xiaochen Yang, Xingjiang Xiong, and Heran Wang are contributed equally to this paper.

References

- 1.Chan P, Thomas GN, Tomlinson B. Protective effects of trilinolein extracted from Panax notoginseng against cardiovascular disease. Acta Pharmacologica Sinica. 2002;23(12):1157–1162. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Dong TTX, Cui XM, Song ZH, et al. Chemical assessment of roots of Panax notoginseng in China: regional and seasonal variations in its active constituents. Journal of Agricultural and Food Chemistry. 2003;51(16):4617–4623. doi: 10.1021/jf034229k. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Yao Y, Wu WY, Guan SH, et al. Proteomic analysis of differential protein expression in rat platelets treated with notoginsengnosides. Phytomedicine. 2008;15(10):800–807. doi: 10.1016/j.phymed.2008.06.013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Ying C. Pharmacodynamical research and clinical application of Panax pseudo-ginseng saponins. Guangxi Medical Journal. 1998;20(6):1109–1112. [Google Scholar]

- 5.Yu L-M, Deng Y-K, Yuan F, et al. The research progress of Panax notoginseng saponins against myocardial ischemia. China Pharmacist. 2011;14(11):1685–1687. [Google Scholar]

- 6.Cheung LWT, Leung KW, Wong CKC, Wong RNS, Wong AST. Ginsenoside-Rg1 induces angiogenesis via non-genomic crosstalk of glucocorticoid receptor and fibroblast growth factor receptor-1. Cardiovascular Research. 2011;89(2):419–425. doi: 10.1093/cvr/cvq300. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Leung KW, Ng HM, Tang MKS, Wong CCK, Wong RNS, Wong AST. Ginsenoside-Rg1 mediates a hypoxia-independent upregulation of hypoxia-inducible factor-1α to promote angiogenesis. Angiogenesis. 2011;14(4):515–522. doi: 10.1007/s10456-011-9235-z. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Wang Z-T, Han L-H, Zhu M-J, et al. Effects of Chinese traditional medicines on angiogenesis and correlative growth factor expression in the ischemic myocardium of the rats with myocardial infarction. Chinese Journal of Integrative Medicine on Cardio-/Cerebrovascular Disease. 2006;4(4):305–307. [Google Scholar]

- 9.The Collaborative Study Group on Trends of Cardiovascular Diseases in China and Prevention. Current status of major cardiovascular risk factors in Chinese populations and their trends in the past two decades. Chinese Journal of Cardiology. 2001;29:74–79. [Google Scholar]

- 10.Patrono C, Coller B, FitzGerald GA, Hirsh J, Roth G. Platelet-active drugs: the relationships among dose, effectiveness, and side effects. Chest. 2004;126(3, supplement):234S–264S. doi: 10.1378/chest.126.3_suppl.234S. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Lau AJ, Toh DF, Chua TK, Pang YK, Woo SO, Koh HL. Antiplatelet and anticoagulant effects of Panax notoginseng: comparison of raw and steamed Panax notoginseng with Panax ginseng and Panax quinquefolium. Journal of Ethnopharmacology. 2009;125(3):380–386. doi: 10.1016/j.jep.2009.07.038. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Zhang WJ, Wojta J, Binder BR. Effect of notoginsenoside R1 on the synthesis of components of the fibrinolytic system in cultured smooth muscle cells of human pulmonary artery. Cellular and Molecular Biology. 1997;43(4):581–587. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Chen S, Liu J, Liu X, et al. Panax notoginseng saponins inhibit ischemia-induced apoptosis by activating PI3K/Akt pathway in cardiomyocytes. Journal of Ethnopharmacology. 2011;137(1):263–270. doi: 10.1016/j.jep.2011.05.011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Palojoki E, Saraste A, Eriksson A, et al. Cardiomyocyte apoptosis and ventricular remodeling after myocardial infarction in rats. The American Journal of Physiology—Heart and Circulatory Physiology. 2001;280(6):H2726–H2731. doi: 10.1152/ajpheart.2001.280.6.H2726. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Saraste A, Pulkki K, Kallajoki M, Henriksen K, Parvinen M, Voipio-Pulkki L. Apoptosis in human acute myocardial infarction. Circulation. 1997;95(2):320–323. doi: 10.1161/01.cir.95.2.320. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Giordano FJ. Oxygen, oxidative stress, hypoxia, and heart failure. Journal of Clinical Investigation. 2005;115(3):500–508. doi: 10.1172/JCI200524408. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Zhao ZQ, Corvera JS, Halkos ME, et al. Inhibition of myocardial injury by ischemic postconditioning during reperfusion: comparison with ischemic preconditioning. The American Journal of Physiology—Heart and Circulatory Physiology. 2003;285(2):H579–H588. doi: 10.1152/ajpheart.01064.2002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Kin H, Zhao ZQ, Sun HY, et al. Postconditioning attenuates myocardial ischemia-reperfusion injury by inhibiting events in the early minutes of reperfusion. Cardiovascular Research. 2004;62(1):74–85. doi: 10.1016/j.cardiores.2004.01.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Fujita M, Asanuma H, Hirata A, et al. Prolonged transient acidosis during early reperfusion contributes to the cardioprotective effects of postconditioning. The American Journal of Physiology—Heart and Circulatory Physiology. 2007;292(4):H2004–H2008. doi: 10.1152/ajpheart.01051.2006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Crompton M, Virji S, Doyle V, Johnson N, Ward JM. The mitochondrial permeability transition pore. Biochemical Society Symposium. 1999;66:167–179. doi: 10.1042/bss0660167. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Davidson SM, Hausenloy D, Duchen MR, Yellon DM. Signalling via the reperfusion injury signalling kinase (RISK) pathway links closure of the mitochondrial permeability transition pore to cardioprotection. International Journal of Biochemistry and Cell Biology. 2006;38(3):414–419. doi: 10.1016/j.biocel.2005.09.017. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Hausenloy DJ, Tsang A, Yellon DM. The reperfusion injury salvage kinase pathway: a common target for both ischemic preconditioning and postconditioning. Trends in Cardiovascular Medicine. 2005;15(2):69–75. doi: 10.1016/j.tcm.2005.03.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Chen SC, Cheng JJ, Hsieh MH, et al. Molecular mechanism of the inhibitory effect of trilinolein on endothelin-1-induced hypertrophy of cultured neonatal rat cardiomyocytes. Planta Medica. 2005;71(6):525–529. doi: 10.1055/s-2005-864153. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Shi R, Liu L, Huo Y, Cheng YY . Study on protective effects of Panax notoginseng saponins on doxorubicin-induced myocardial damage. China Journal of Chinese Materia Medica. 2007;32(24):2632–2635. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Chen JQ, Zhang YG, Li SL, Zeng Q, Rong MZ. Effects of Panax notoginseng saponins on myocardial adenosinetriphosphatase. Acta Pharmacologica Sinica. 1994;15(4):347–350. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Cosgrove DM, Loop FD, Lytle BW, et al. Predictors of reoperation after myocardial revascularization. Journal of Thoracic and Cardiovascular Surgery. 1986;92(5):811–821. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Frazier OH, Cooley DA, Kadipasaoglu KA, et al. Myocardial revascularization with laser: preliminary findings. Circulation. 1995;92(9, supplement):II58–II65. doi: 10.1161/01.cir.92.9.58. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Banai S, Jaklitsch MT, Shou M, et al. Angiogenic-induced enhancement of collateral blood flow to ischemic myocardium by vascular endothelial growth factor in dogs. Circulation. 1994;89(5):2183–2189. doi: 10.1161/01.cir.89.5.2183. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Yanagisawa-Miwa A, Uchida Y, Nakamura F, et al. Salvage of infarcted myocardium by angiogenic action of basic fibroblast growth factor. Science. 1992;257(5075):1401–1403. doi: 10.1126/science.1382313. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Unger EF, Banai S, Shou M, et al. Basic fibroblast growth factor enhances myocardial collateral flow in a canine model. The American Journal of Physiology—Heart and Circulatory Physiology. 1994;266(4):H1588–H1595. doi: 10.1152/ajpheart.1994.266.4.H1588. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Magovern CJ, Mack CA, Zhang J, Rosengart TK, Isom OW, Crystal RG. Regional angiogenesis induced in nonischemic tissue by an adenoviral vector expressing vascular endothelial growth factor. Human Gene Therapy. 1997;8(2):215–227. doi: 10.1089/hum.1997.8.2-215. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Shou M, Thirumurti V, Rajanayagam MAS, et al. Effect of basic fibroblast growth factor on myocardial angiogenesis in dogs with mature collateral vessels. Journal of the American College of Cardiology. 1997;29(5):1102–1106. doi: 10.1016/s0735-1097(97)00014-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Chiu RC, Zibaitis A, Kao RL. Cellular cardiomyoplasty: myocardial regeneration with satellite cell implantation. Annals of Thoracic Surgery. 1995;60(1):12–18. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Lei Y, Tian W, Zhu LQ, Yang J, Chen KJ. Effects of Radix Ginseng and Radix Notoginseng formula on secretion of vascular endothelial growth factor and expression of vascular endothelial growth factor receptor-2 in human umbilical vein endothelial cells. Journal of Chinese Integrative Medicine. 2010;8(4):368–372. doi: 10.3736/jcim20100412. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.World Health Organization. The Global Burden of Disease 2004 Update. Geneva, Switzerland: WHO; 2004. [Google Scholar]

- 36.Davidson P, Hancock K, Leung D, et al. Traditional Chinese Medicine and heart disease: what does Western medicine and nursing science know about it? European Journal of Cardiovascular Nursing. 2003;2(3):171–181. doi: 10.1016/S1474-5151(03)00057-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Han SY, Li HX, Ma X, et al. Evaluation of the anti-myocardial ischemia effect of individual and combined extracts of Panax notoginseng and Carthamus tinctorius in rats. Journal of Ethnopharmacology. 2013;145(3):722–727. doi: 10.1016/j.jep.2012.11.036. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Zhu D, Wu L, Li CR, et al. Ginsenoside Rg1 protects rat cardiomyocyte from hypoxia/reoxygenation oxidative injury via antioxidant and intracellular calcium homeostasis. Journal of Cellular Biochemistry. 2009;108(1):117–124. doi: 10.1002/jcb.22233. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Scandinavian Simvastatin Survival Study Group. Randomised trial of cholesterol lowering in 4444 patients with coronary heart disease: the Scandinavian Simvastatin Survival Study (4S) The Lancet. 1994;344(8934):1383–1389. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Sacks FM, Pfeffer MA, Moye LA, et al. The effect of pravastatin on coronary events after myocardial infarction in patients with average cholesterol levels. The New England Journal of Medicine. 1996;335(14):1001–1009. doi: 10.1056/NEJM199610033351401. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Sever PS, Dahlöf B, Poulter NR, et al. Prevention of coronary and stroke events with atorvastatin in hypertensive patients who have average or lower-than-average cholesterol concentrations, in the Anglo-Scandinavian Cardiac Outcomes Trial-Lipid Lowering Arm (ASCOT-LLA): a multicentre randomised controlled trial. The Lancet. 2003;361(9364):1149–1158. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(03)12948-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Long-Term Intervention with Pravastatin in Ischaemic Disease (LIPID) Study Group. Prevention of cardiovascular events and death with pravastatin in patients with coronary heart disease and a broad range of initial cholesterol levels. The New England Journal of Medicine. 1998;339(19):1349–1357. doi: 10.1056/NEJM199811053391902. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Heart Protection Study Collaborative Group. MRC/BHF Heart Protection Study of cholesterol lowering with simvastatin in 20,536 high-risk individuals: a randomised placebo-controlled trial. The Lancet. 2002;360(9326):7–22. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(02)09327-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Brown AS, Bakker-Arkema RG, Yellen L, et al. Treating patients with documented atherosclerosis to national cholesterol education program-recommended low-density-lipoprotein cholesterol goals with atorvastatin, fluvastatin, lovastatin and simvastatin. Journal of the American College of Cardiology. 1998;32(3):665–672. doi: 10.1016/s0735-1097(98)00300-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Xia W, Sun C, Zhao Y, Wu L. Hypolipidemic and antioxidant activities of Sanchi (Radix Notoginseng) in rats fed with a high fat diet. Phytomedicine. 2011;18(6):516–520. doi: 10.1016/j.phymed.2010.09.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Rhule A, Rase B, Smith JR, Shepherd DM. Toll-like receptor ligand-induced activation of murine DC2.4 cells is attenuated by Panax notoginseng. Journal of Ethnopharmacology. 2008;116(1):179–186. doi: 10.1016/j.jep.2007.11.019. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Wu L, Zhang W, Tang YH, et al. Effect of total saponins of “panax notoginseng root” on aortic intimal hyperplasia and the expressions of cell cycle protein and extracellular matrix in rats. Phytomedicine. 2010;17(3-4):233–240. doi: 10.1016/j.phymed.2009.07.021. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Wang J, Wu L, Zhang W, Deng C. Effect of Panax notoginseng saponins on vascular intima hyperplasia and PCNA expression in rat aorta after balloon angioplasty. China Journal of Chinese Materia Medica. 2009;34(6):735–739. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Zhang W, Chen G, Deng CQ. Effects and mechanisms of total Panax notoginseng saponins on proliferation of vascular smooth muscle cells with plasma pharmacology method. Journal of Pharmacy and Pharmacology. 2012;64(1):139–145. doi: 10.1111/j.2042-7158.2011.01379.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Xu L, Liu JT, Liu N, Lu PP, Pang XM. Effects of Panax notoginseng saponins on proliferation and apoptosis of vascular smooth muscle cells. Journal of Ethnopharmacology. 2011;137(1):226–230. doi: 10.1016/j.jep.2011.05.020. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Lin SG, Zheng XL, Chen QY, Sun JJ. Effect of Panax notoginseng saponins on increased proliferation of cultured aortic smooth muscle cells stimulated by hypercholesterolemic serum. Acta Pharmacologica Sinica. 1993;14(4):314–316. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Wang J, Hu JH. Inhibitory effect of Panax notoginseng on the VSMC proliferation induced by hyperlipidemia serum. China Journal of Chinese Materia Medica. 2006;31(7):588–590. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Liu G, Wang B, Zhang J, Jiang H, Liu F. Total panax notoginsenosides prevent atherosclerosis in apolipoprotein E-knockout mice: role of downregulation of CD40 and MMP-9 expression. Journal of Ethnopharmacology. 2009;126(2):350–354. doi: 10.1016/j.jep.2009.08.014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Qin JH, Zhu LQ, Cui W. Effects of panax notoginseng saponins on expression of intercellular adhesion molecule-1 in human umbilical vein endothelial cells injury induced by oxidized low-density lipoprotein. Zhongguo Zhong Xi Yi Jie He Za Zhi. 2008;28(12):1096–1099. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Liu Y, Zhang HG, Jia Y, Li XH. Panax notoginseng saponins attenuate atherogenesis accelerated by zymosan in rabbits. Biological and Pharmaceutical Bulletin. 2010;33(8):1324–1330. doi: 10.1248/bpb.33.1324. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Fan JS, Liu DN, Huang G, et al. Panax notoginseng saponins attenuate atherosclerosis via reciprocal regulation of lipid metabolism and inflammation by inducing liver X receptor alpha expression. Journal of Ethnopharmacology. 2012;142(3):732–738. doi: 10.1016/j.jep.2012.05.053. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Zhang YG, Zhang HG, Zhang GY, et al. Panax notoginseng saponins attenuate atherosclerosis in rats by regulating the blood lipid profile and an anti-inflammatory action. Clinical and Experimental Pharmacology and Physiology. 2008;35(10):1238–1244. doi: 10.1111/j.1440-1681.2008.04997.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Yuan Z, Liao Y, Tian G, et al. Panax notoginseng saponins inhibit Zymosan A induced atherosclerosis by suppressing integrin expression, FAK activation and NF-κB translocation. Journal of Ethnopharmacology. 2011;138(1):150–155. doi: 10.1016/j.jep.2011.08.066. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Wang N, Wan JB, Chan SW, et al. Comparative study on saponin fractions from Panax notoginseng inhibiting inflammation-induced endothelial adhesion molecule expression and monocyte adhesion. Chinese Medicine. 2011;6(article 37) doi: 10.1186/1749-8546-6-37. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Hong SJ, Wan JB, Zhang Y, et al. Angiogenic effect of saponin extract from Panax notoginseng on HUVECs in vitro and zebrafish in vivo. Phytotherapy Research. 2009;23(5):677–686. doi: 10.1002/ptr.2705. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Ommen SR, Odell JA, Stanton MS. Atrial arrhythmias after cardiothoracic surgery. The New England Journal of Medicine. 1997;336(20):1429–1434. doi: 10.1056/NEJM199705153362006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Kim MH, Deeb GM, Morady F, et al. Effect of postoperative atrial fibrillation on length of stay after cardiac surgery (the postoperative atrial fibrillation in cardiac surgery study [PACS2]) The American Journal of Cardiology. 2001;87(7):881–885. doi: 10.1016/s0002-9149(00)01530-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Wu W, Zhang XM, Liu PM, Li JM, Wang JF. Effects of Panax notoginseng saponin Rg1 on cardiac electrophysiological properties and ventricular fibrillation threshold in dogs. Acta Pharmacologica Sinica. 1995;16(5):459–463. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Calhoun DA, Jones D, Textor S, et al. Resistant hypertension: siagnosis, evaluation, and treatment a scientific statement from the American heart association professional education committee of the council for high blood pressure research. Hypertension. 2008;51(6):1403–1419. doi: 10.1161/HYPERTENSIONAHA.108.189141. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Kwan CY, Kwan TK. Effects of Panax notoginseng saponins on vascular endothelial cells in vitro. Acta Pharmacologica Sinica. 2000;21(12):1101–1105. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Guan YY, Zhou JG, Zhang Z, et al. Ginsenoside-Rd from panax notoginseng blocks Ca2+ influx through receptor- and store-operated Ca2+ channels in vascular smooth muscle cells. European Journal of Pharmacology. 2006;548(1–3):129–136. doi: 10.1016/j.ejphar.2006.08.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Li SY, Wang XG, Ma MM, et al. Ginsenoside-Rd potentiates apoptosis induced by hydrogen peroxide in basilar artery smooth muscle cells through the mitochondrial pathway. Apoptosis. 2012;17(2):113–120. doi: 10.1007/s10495-011-0671-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Pan C, Huo Y, An X, et al. Panax notoginseng and its components decreased hypertension via stimulation of endothelial-dependent vessel dilatation. Vascular Pharmacology. 2012;56(3-4):150–158. doi: 10.1016/j.vph.2011.12.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Shemirani H, Hemmati R, Khosravi A, Gharipour M, Jozan M. Echocardiographic assessment of inappropriate left ventricular mass and left ventricular hypertrophy in patients with diastolic dysfunction. Journal of Research in Medical Sciences. 2012;17(2):133–137. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Manolio TA, Levy D, Garrison RJ, Castelli WP, Kannel WB. Relation of alcohol intake to left ventricular mass: the Framingham study. Journal of the American College of Cardiology. 1991;17(3):717–721. doi: 10.1016/s0735-1097(10)80189-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71.Zhou Y, Tian L, Mo K. Relationship between the inhibitory effects of PNS on cardiac hypertrophy and its action on neurohormonal factor. China Journal of Chinese Materia Medica. 2005;30(12):916–919. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72.Feng P, Jiang H. Effect of total saponins of Panax notoginseng (TSPNS) on myocardial intracellular Ca2+ and activity of calcium pump of membrane of sarcoplasmic reticulum in SHR. China Journal of Chinese Materia Medica. 1998;23(3):173–175. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73.Guo JW, Li LM, Qiu GQ, et al. Effects of Panax notoginseng saponins on ACE2 and TNF-alpha in rats with post-myocardial infarction-ventricular remodeling. Journal of Chinese Medicinal Materials. 2010;33(1):89–92. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74.Richard K. Primary prevention of coronary heart disease: integration of new data, evolving views, revised goals, and role of rosuvastatin in management. A comprehensive survey. Drug Design, Development and Therapy. 2011;5:325–380. doi: 10.2147/DDDT.S14934. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 75.Rosamond W, Flegal K, Furie K, et al. Heart disease and stroke statistics—2008 update: a report from the American heart association statistics committee and stroke statistics subcommittee. Circulation. 2008;117(4):e25–146. doi: 10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.107.187998. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 76.Grech ED. ABC of interventional cardiology: percutaneous coronary intervention. II: the procedure. The British Medical Journal. 2003;326(7399):1137–1140. doi: 10.1136/bmj.326.7399.1137. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 77.Lloyd-Jones D, Adams RJ, Brown TM, et al. Executive summary: heart disease and stroke statistics—2010 update: a report from the American heart association. Circulation. 2010;121(7):948–954. doi: 10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.109.192666. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 78.Xiong XJ, Yang XC, Liu YM, Zhang Y, Wang PQ, Wang J. Chinese herbal formulas for treating hypertension in traditional Chinese medicine: perspective of modern science. Hypertension Research. 2013;36(7):570–579. doi: 10.1038/hr.2013.18. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 79.Xiong XJ, Yang XC, Liu W, Chu FY, Wang PQ, Wang J. Trends in the treatment of hypertension from the perspective of traditional chinese medicine. Evidence-Based Complementary and Alternative Medicine. 2013;2013:13 pages. doi: 10.1155/2013/275279.275279 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 80.Wang J, Xiong XJ, Yang GY, et al. Chinese herbal medicine Qi Ju di Huang Wan for the treatment of essential hypertension: a systematic review of randomized controlled trials. Evidence-Based Complementary and Alternative Medicine. 2013;2013:10 pages. doi: 10.1155/2013/262685.262685 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 81.Wang J, Xiong XJ. Current situation and perspectives of clinical study in integrative medicine in China. Evidence-Based Complementary and Alternative Medicine. 2012;2012:11 pages. doi: 10.1155/2012/268542.268542 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 82.Wang J, Yao KW, Yang XC, et al. Chinese patent medicine Liu Wei di Huang Wan combined with antihypertensive drugs, a new integrative medicine therapy, for the treatment of essential hypertension: a systematic review of randomized controlled trials. Evidence-Based Complementary and Alternative Medicine. 2012;2012:7 pages. doi: 10.1155/2012/714805.714805 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 83.Aziz S, Morris JL, Perry RA. Late stent thrombosis associated with coronary aneurysm formation after sirolimus-eluting stent implantation. Journal of Invasive Cardiology. 2007;19(4):E96–E98. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]