Abstract

We show that silymarin, a polyphenolic flavonoid isolated from milk thistle (Silybum marianum), inhibits cytokine mixture (CM: TNF-α, IFN-γ, and IL-1β)-induced production of nitric oxide (NO) in the pancreatic beta cell line MIN6N8a. Immunostaining and Western blot analysis showed that silymarin inhibits iNOS gene expression. RT-PCR showed that silymarin inhibits iNOS gene expression in a dose-dependent manner. We also showed that silymarin inhibits extracellular signal-regulated protein kinase-1 and 2 (ERK1/2) phosphorylation. A MEK1 inhibitor abrogated CM-induced nitrite production, similar to silymarin. Treatment of MIN6N8a cells with silymarin also inhibited CM-stimulated activation of NF-κB, which is important for iNOS transcription. Collectively, we demonstrate that silymarin inhibits NO production in pancreatic beta cells, and silymarin may represent a useful anti-diabetic agent.

Keywords: Silymarin, Beta cells, NO, iNOS, ERK1/2

INTRODUCTION

Insulin-dependent Diabetes mellitus (IDDM) is characterized by selective destruction of insulin-producing beta cells in the pancreatic islets of Langerhans. Strong experimental evidence suggests that proinflammatory cytokines, such as tumor necrosis factor (TNF)-α, interferon (IFN)-γ, and interleukin (IL)-1β produced nitric oxide (NO) and influence pancreatic beta cells destruction by stimulating the production of oxygen radicals (Cetkovic-Cvrlje and Eizirik, 1994; Darville and Eizirik, 1998; Broniowska et al., 2014). Further, IFN-γ, TNF-α, and IL-1β synergistically increase the expression of inducible NO synthase (iNOS) and NO generation (Yamada et al., 1993; Cetkovic-Cvrlje and Eizirik, 1994). A transgenic mouse study showed that NO plays an important role in beta cell destruction (Takamura et al., 1998; Flodstrom et al., 1999). NO inhibits the activity of the mitochondrial Krebs cycle enzyme aconitase in addition to electron transport, resulting in an impairment of mitochondrial function and insulin secretion (Corbett et al., 1992; Welsh and Sandler, 1992). NO induces ataxia telangiectasia mutated protein (ATM)-dependent γ-H2AX protein phosphorylation, a marker of double-stranded breaks of DNA, in pancreatic β cells (Oleson et al., 2014). Transgenic mice carrying that express iNOS cDNA under the control of the insulin promoter have been shown to develop diabetes, whereas treatment with the iNOS inhibitor aminoguanidine prevented or delayed the development of diabetes (Takamura et al., 1998). IL-1β fails to induce iNOS mRNA expression or increase nitrite formation in islets isolated from iNOS knockout mice, with no impairment in islet function observed (Flodstrom et al., 1999). Moreover, iNOS knockout mice exhibited reduced sensitivity to multiple low-dose streptozotocin-induced diabetes (Flod-strom et al., 1999). Therefore, inhibition of NO production by blocking iNOS production or activity may be a useful strategy to prevent inflammatory disorders, including IDDM.

Silymarin is a standardized extract isolated from the fruit and seeds of milk thistle Silybum marianum (Pliskova et al., 2005). Silymarin is known to protect against hepatotoxicity caused by a variety of agents including ethanol, phenylhydrazine, acetaminophen, microcystin, and ochratoxin (Mereish et al., 1991; Valenzuela and Garrido, 1994; Bektur et al., 2013; Zhang et al., 2013). Main silymarin components (silybin, isosilybin, silydianin and silychristin) were analyzed using HPLC and proposed capillary zone electrophoresis methods (Kvasnicka et al., 2003). Various studies also indicate that sili binin, a major polyphenolc flavonoid in silymarin, exhibits anticarcinogenic effects (Hogan et al., 2007; Mokhtari et al., 2008). Moreover, silibinin possesses a number of additional biological effects such as anti-inflammatory effects (Kang et al., 2002; Cristofalo et al., 2013). Silymarin induces recovery of the endocrine function of damaged pancreatic tissue in alloxan-induced diabetic rats (Soto et al., 2004). Silymarin treatment increased the expression of both Pdx-1 and the insulin gene, while increasing β-cell proliferation in pancreatic tissue (Soto et al., 2014). Although the mechanism is largely unknown, silymarin does exert direct antioxidant activity by scavenging free radicals, and modulating antioxidant and inflammatory enzymes (Letteron et al., 1990; Zhao et al., 1999). In the present study, we investigated the effects of silymarin on the regulation of iNOS, p44/42, and NF-κB activities in proinflammatory cytokine-stimulated the MIN6N8a, a mouse pancreatic beta cell line.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Materials

MIN6N8a cells, SV40 T-transformed insulinoma cells derived from NOD mice, were grown in Dulbecco’s Modifed Eagle’s Medium supplemented with 10% fetal bovine serum, 2 mM L-glutamine, 100 U/ml of penicillin, 100 μg/ml of streptomycin, and 50 μM 2-mercaptoethanol. For each experiment, cells (5×105 cells/ml) were plated in 100-mm dishes. Silymarin and PD98059 (2’-amino-3’-methoxyflavone) were purchased from Sigma (St. Louis, MO) and CalBiochem (San Diego, CA), respectively. The anti-iNOS antibody and antibodies against phospho-p44/42 and p44/42 were purchased from Upstate Biotechnology (Lake Placid, NY, USA) and Cell Signaling Technology, Inc. (Beverly, MA, USA), respectively.

Nitrite determination

MIN6N8a cells were treated with the indicated concentrations of silymarin in the presence of cytokine mixture (CM: TNF-α, 500 U/ml; IFN-γ, 100 U/ml; IL-1β, 10 U/ml) for 48 h. Culture supernatants were collected, and the accumulation of NO2− in culture supernatants was measured as an indicator of NO production in the medium as previously described (Green et al., 1982; Huong et al., 2012).

Immunofluorescence staining

MIN6N8a cells were treated with silymarin (50 μg/ml) in the presence of CM on a cover slide in 12-well plates. Cells were rinsed 3 times with PBS, fixed with 4% paraformaldehyde for 10 min at room temperature, and rinsed again. Cells were then blocked with 1% bovine serum albumin, followed by the addition of the primary antibody. After extensive washing with Tris-buffered saline, fluorescein isothiocyanate-conjugated IgG was added. Following incubation, the slides were rinsed, mounted, and viewed at 488 nm on a confocal microscope (FV300, Olympus, Japan).

RT-PCR

Total RNA was isolated with TRI Reagent (Molecular Research Center, Cincinnati, OH, USA). Forward and reverse primer sequences were as follows: iNOS: 5´-CTG CAG CAC TTG GAT CAG GAA CCT G-3´, 5′-GGG AGT AGC CTG TGT GCA CCT GGA A-3′; and β-actin: 5′-TGG AAT CCT GTG GCA TCC ATG AAA C-3′, 5′-TAA AAC GCA GCT CAG TAA CAG TCC G-3′. Equal amounts of RNA were reverse-transcribed into cDNA with oligo(dT)15 primers. PCR was performed with cDNA and each primer. Samples were heated to 94°C for 5 min and cycled 30 times at 94°C for 1 min, 55°C for 1.5 min, and 94°C for 1 min, after which an additional extension step at 72°C for 5 min was conducted. PCR products were separated by 8% SDS-PAGE, followed by staining with ethidium bromide. The iNOS and β-actin primers produced amplified products of 311 and 349 bp, respectively.

Western immunoblot analysis

Whole cell lysates were separated by 10% SDS-PAGE and then electrotransferred to nitrocellulose membranes (Amer-sham International, Buckinghamshire, UK). The membranes were then preincubated for 1 h at room temperature in Tris-buffered saline (TBS), pH 7.6 containing 0.05% Tween-20 and 3% bovine serum albumin, followed by incubation with iNOS, phosphorylated ERK1/2, and phospho-ERK1/2 (Thr202/Tyr-204)-specific antibodies. Immunoreactive bands were detected by incubation with conjugates of anti-rabbit IgG with horse-radish peroxidase and enhanced chemiluminescence reagent (Amersham).

Electrophoretic mobility shift assay (EMSA)

An EMSA was performed as described in previous literature (Jeon et al., 1996; Li et al., 2010). Nuclear extracts were prepared as previously described (Xie et al., 1993). The double-stranded oligonucleotides were end-labeled with [γ-32P]-ATP. Nuclear extracts (5 μg) were incubated with poly (dI-dC) and the [32P]-labeled DNA probe in binding buffer (100 mM KCl, 30 mM HEPES, 1.5 mM MgCl2, 0.3 mM EDTA, 10% glycerol, 1 mM DTT, 1 mM PMSF, 1 μg/ml of aprotinin, and 1 μg/ml of leupeptin) for 10 min. DNA-binding activity was separated from free probe by 4% SDS-PAGE in 0.5X TBE buffer. Following elec trophoresis, the gel was dried and subjected to autoradiography.

Statistical analysis

The mean ± SD was determined for each treatment group in a given experiment. When significant differences were present, treatment groups were compared to the respective vehicle controls using a Dunnett’s two-tailed t test (Dunnett, 1955).

RESULTS

Inhibition of iNOS expression by silymarin in cytokine-stimulated MIN6N8a cells

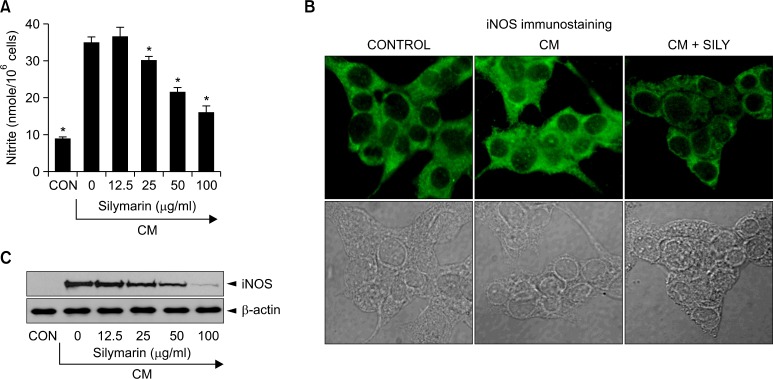

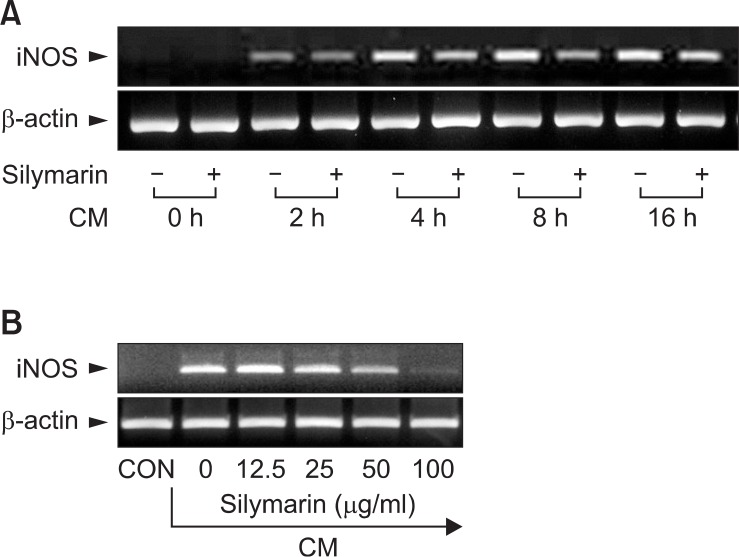

We investigated the effects of silymarin on iNOS production in cytokine-stimulated MIN6N8a mouse pancreatic beta cells. Cytokines, including IL-1β, IFN-γ, and TNF-α, are known to induce or potentiate iNOS expression and NO producti on (Cetkovic-Cvrlje and Eizirik, 1994; Darville and Eizirik, 1998). Treatment with a cytokine mixture (CM: TNF-α, 500 U/ml; IFN-γ, 100 U/ml; IL-1β, 10 U/ml) increased production of nitri te ≥ 4-fold over basal levels in MIN6N8a cells (Fig. 1A). CM-induced nitrite generation was inhibited by silymarin in a dose-dependent manner. We further analyzed the effects of silymarin on iNOS production by immunohistochemical staining. MIN6N8a cells were cultured on a cover slip in 12-well plates and incubated with silymarin (50 μg/ml) in the presence of CM for 24 h. Immunofluorescence staining of iNOS showed that silymarin inhibited iNOS production (Fig. 1B). Western immunoblot analysis further confirmed the inhibition of iNOS by silymarin (Fig. 1C). We next analyzed the effect of silymarin on iNOS gene expression. iNOS mRNA expression after CM treatment was detected at 2 h, peaked at 8 h, and was maintained until 16 h, and the expression of iNOS mRNA was inhibited by silymarin (Fig. 2A). Silymarin also inhibited iNOS mRNA expression in a dose-dependent manner (Fig. 2B). Control β-actin was constitutively expressed and was not affected by silymarin treatment. These results showed that silymarin decreased iNOS gene expression, which is involved in pancreatic beta cell destruction.

Fig. 1.

Inhibition of the production of nitrite and iNOS by silymarin in cytokine-mixture (CM)-stimulated pancreatic beta cells. The pancreatic beta cell line, MIN6N8a, was treated with the indicated concentrations of Silymarin in the presence of cytokine mixture (CM: TNF-α, 500 U/ ml; IFN-γ, 100 U/ml; IL-1β, 10 U/ml) for 48 h. (A) Supernatants were subsequently isolated and analyzed for nitrite. (B) MIN6N8a cells were treated with silymarin (50 μg/ml) in the presence of CM for 24 h on a cover slip in 12-well plates. Cells were subjected to immunofluorescence staining using an antibody specific for murine iNOS. The immunoreactive regions for iNOS were localized along the margins of the cytoplasm in the control group. (C) MIN6N8a cells were treated with the indicated concentrations of silymarin in the presence of CM for 24 h Expression of iNOS was analyzed by Western blot using an antibody specific for murine iNOS. Each column shows the mean ± S.D. of triplicate determinations. *p<0.05 compared to the control group as determined by Dunnett’s two-tailed t test.

Fig. 2.

Inhibition of iNOS gene expression by silymarin in CM-stimulated MIN6N8a cells. (A) MIN6N8a cells were treated with silymarin (50 μg/ml) in the presence of CM for indicated times. (B) Cells were treated with indicated concentrations of silymarin in the presence of CM for 8 h. Total RNA was isolated and analyzed for mRNA expression levels of iNOS and β-actin.

Inhibition of p44/42 (ERK1/2) phosphorylation by silymarin in CM-stimulated MIN6N8a cells

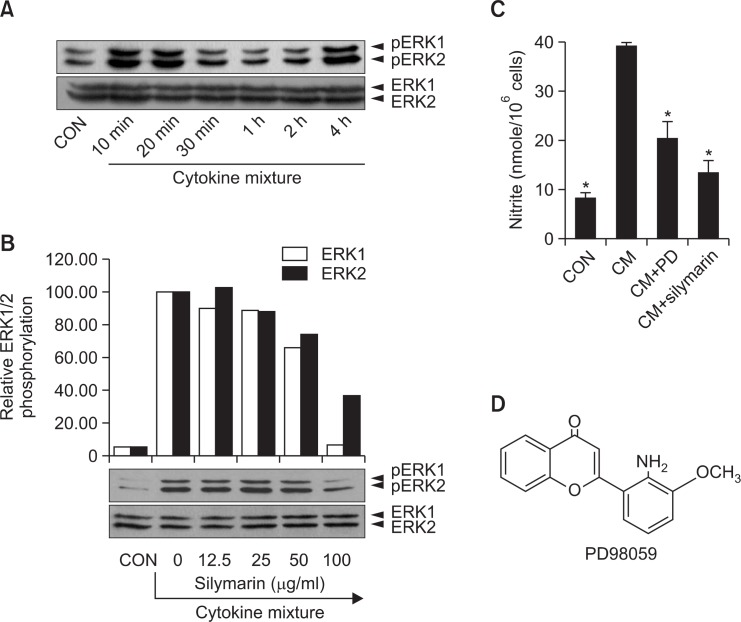

Since p44/42 kinase is important for NO generation in CM-stimulated MIN6N8a and a possible target of silymarin, we further determined the role of p44/42 in NO inhibition by silymarin. A kinetic study showed that CM-induced phosphorylation of p44/42 peaked at 10 min, was maintained until 20 min, and then decreased at 30 min (Fig. 3A). When cells were treated with silymarin for 20 min in the presence of CM, the phosphorylation of p44/p42 was decreased in a dose-related manner (Fig. 3B). The p44/42 kinase pathways were specifically blocked when MIN6N8a cells were treated with CM. PD98059 is a specific inhibitor of mitogen activated protein kinase/extracellular signal-regulated kinase 1 (MEK-1), which is responsible for ERK1/2 activation. PD98059 inhibited CM-induced production of nitrite, whereas SB203580, a bicyclic inhibitor of p38, had no inhibitory effect (Fig. 3C). These results suggest that the p44/42 kinase pathway plays an important role in the regulation of NO generation in CM-stimulated MIN6N8a cells, and that is inhibited by silymarin.

Fig. 3.

Inhibition of p44/42 phosphorylation by silymarin in CM-stimulated MIN6N8a cells. (A) MIN6N8a cells were treated with CM for the indicated time. (B) Cells were treated with silymarin for 20 min in the presence of CM. The phosphorylation of p44/p42 was analyzed by Western blot. The relative band densities were analyzed with Image J program. (C) Cells were treated with PD98059 (50 μM) or silymarin (50 μg/ml) for 48 h in the presence of CM. The supernatants were subsequently isolated and analyzed for nitrite. Each column shows the mean ± S.D. of triplicate determinations. *p<0.05 compared to the control group as determined by Dunnett’s two-tailed t test. (D) The chemical structure of PD98059.

Inhibition of NF-κB activation by silymarin in CM-stimulated MIN6N8a cells

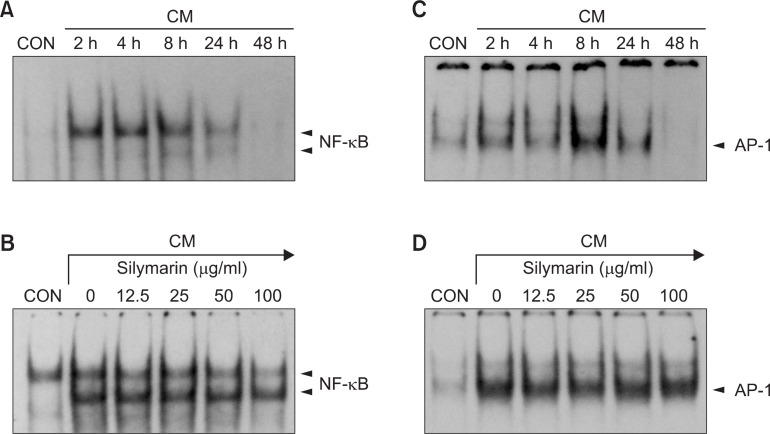

The effects of silymarin on NF-κB and AP-1, which have bi nding motifs in the promoter of iNOS gene, were evaluated using EMSA. Treatment of MIN6N8a cells with CM induced a marked increase in NF-κB binding to its cognate site (Fig. 4A). The induction of NF-κB binding was inhibited by silymarin in a dose-dependent manner (Fig. 4B). Protein binding at NF-κB-binding sequences is necessary for induction of iNOS expression (Xie et al., 1994). AP1, a transcription factor that binds to the promoter of the iNOS gene, was also induced by CM (Fig. 4C). However, CM-induced AP-1 binding was not significantly influenced by silymarin (Fig. 4D). The specificity of the retarded bands was confirmed by adding excess 32P-unlabeled double-stranded NF-κB or AP-1 (data not shown). These results indicate that silymarin reduces the DNA-binding activity of NF-κB, which is important in the regulation of iNOS gene expression by CM in pancreatic beta cells.

Fig. 4.

Inhibition of NF-κB activation by silymarin in CM-stimulated MIN6N8a cells. (A, C) MIN6N8a cells were treated with CM for the indicated times. Nuclear extracts were then isolated and analyzed for the activities of NF-κB (A) and AP-1 (C). (B, D) Cells were incubated with silymarin in the presence of CM for 2 h. Nuclear extracts were then isolated and analyzed for the activities of NF-κB (B) and AP-1 (D).

DISCUSSION

In a previous study, we showed that production of NO, an important mediator of inflammatory responses, is inhibited by silymarin in LPS-stimulated macrophages (Kang et al., 2002). Since proinflammatory cytokines are known to induce the expression of iNOS mRNA and production of NO, resulting in cell death of beta cells (Cetkovic-Cvrlje and Eizirik, 1994; Darville and Eizirik, 1998), we investigated if silymarin could suppress NO production and iNOS gene expression induced by cytokines. We demonstrated that silymarin inhibits NO production and iNOS gene expression in mouse pancreatic beta cells. The protective role of silymarin in pancreatic beta cells was further supported by a previous study that utilized the RINm5F rat insulinoma cell line (Matsuda et al., 2005). IL-1β and/or IFN-γ induced cell death in a time-dependent manner in RINm5F cells and correlated well with NO production. Silymarin inhibited both cytokine-induced NO production and cell death in RINm5F cells. An in vivo study using a rat model further showed that silymarin increased insulin gene expression and beta cell proliferation (Soto et al., 2014).

We demonstrated that silymarin inhibits the p44/42 (ERK-1/2) pathway in cytokine-stimulated beta cells. Silibinin, a major component of silymarin, has been shown to inhibit TPA-induced MMP-9 expression through the Raf/MEK/ERK pathway in thyroid and breast cancer cells (Kim et al., 2009a; Oh et al., 2013). Silibinin also prevented TNF-α-induced MMP-9 expression in gastric cancer cells through inhibition of the MAPK pathway (Kim et al., 2009b). ERK activity is required for iNOS gene expression in insulin-producing INS-1E cells and MIN6N8a cells (Larsen et al., 2005; Youn et al., 2013). In the present study, we demonstrated that the involvement of the ERK1/2 pathways in the regulation of iNOS gene expression in a mouse insulinoma cell line stimulated with cytokines. PD98059, which selectively inhibit the ERK1/2 pathway, inhibited NO production in response to CM, similarly to silimarin. ERK has been reported to be involved in NF-κB-mediated transcription of iNOS, indicating that ERK regulates iNOS gene expression by increasing the transactivation capacity of NF-κB (Larsen et al., 2005).

In vitro evidence suggests that cytokine-induced activation of the transcription factor NF-κB is an important component of signaling that trigger beta cell apoptosis (Baker et al., 2001; Heimberg et al., 2001). Expression of a dominant negative inhibitor of NF-κB protects MIN6 beta-cells from cytokine-induced apoptosis. Conditional NF-κB blockade using a degradation-resistant NF-κB protein inhibitor protects pancreatic beta cells from diabetogenic agents (Eldor et al., 2006). The transgenic mice showed nearly complete protection against diabetes induced by multiple low doses of streptozotocin and reduced intraislet lymphocytic infiltration. In the present study, we showed that NF-κB was positively regulated by CM treatment to induce iNOS gene expression, whereas silymarin significantly inhibited the CM-induced NF-κB activity (Fig. 4B). NF-κB plays an important role in the expression of many genes involved in inflammatory responses, including iNOS (Xie et al., 1994). In unstimulated cells, NF-κB exists in the cytoplasm as an inactive form bound to IκB, an inhibitor of NF-κB. External stimuli, including cytokines and lipopolysaccharide, results in the phosphorylation of IκB, which releases the active NF-κB to bind κB motifs in the promoter regions of various genes including iNOS.

In summary, these experiments demonstrate that silymarin inhibits CM-induced iNOS gene expression in a mouse pancreatic beta cell line. Based on our findings, the most likely mechanism that can account for this biological effect involves inhibition of the ERK1/2 kinase pathway and NF-κB activity. Due to the critical role that NO release, NF-κB, and ERK1/2 play in mediating inflammatory responses in pancreatic beta cells, inhibition of these activities by silymarin is a potential useful strategy for beta cell protection.

Acknowledgments

This research was supported by research funds from Chosun University, 2013.

REFERENCES

- Baker MS, Chen X, Cao XC, Kaufman DB. Expression of a dominant negative inhibitor of NF-kappaB protects MIN6 beta-cells from cytokine-induced apoptosis. J Surg Res. 2001;97:117–122. doi: 10.1006/jsre.2001.6121. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bektur NE, Sahin E, Baycu C, Unver G. Protective effects of silymarin against acetaminophen-induced hepatotoxicity and nephrotoxicity in mice. Toxicol Ind Health. 2013:1–12. doi: 10.1177/0748233713502841. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Broniowska KA, Oleson BJ, Corbett JA. beta-cell responses to nitric oxide. Vitam Horm. 2014;95:299–322. doi: 10.1016/B978-0-12-800174-5.00012-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cetkovic-Cvrlje M, Eizirik DL. TNF-alpha and IFN-gamma potentiate the deleterious effects of IL-1 beta on mouse pancreatic islets mainly via generation of nitric oxide. Cytokine. 1994;6:399–406. doi: 10.1016/1043-4666(94)90064-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Corbett JA, Wang JL, Hughes JH, Wolf BA, Sweetland MA, Lancaster JR, Jr, McDaniel ML. Nitric oxide and cyclic GMP formation induced by interleukin 1 beta in islets of Langerhans. Evidence for an effector role of nitric oxide in islet dysfunction. Biochem J. 1992;287(Pt 1):229–235. doi: 10.1042/bj2870229. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cristofalo R, Bannwart-Castro CF, Magalhaes CG, Borges VT, Peracoli JC, Witkin SS, Peracoli MT. Silibinin atte nuates oxidative metabolism and cytokine production by monocytes from preeclamptic women. Free Radic Res. 2013;47:268–275. doi: 10.3109/10715762.2013.765951. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Darville MI, Eizirik DL. Regulation by cytokines of the inducible nitric oxide synthase promoter in insulin-producing cells. Diabetologia. 1998;41:1101–1108. doi: 10.1007/s001250051036. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dunnett M. A multiple comparison procedure for comparing several treatments with a control. J Am Stat Assoc. 1955;50:1096–1121. [Google Scholar]

- Eldor R, Yeffet A, Baum K, Doviner V, Amar D, Ben-Neriah Y, Christofori G, Peled A, Carel JC, Boitard C, Klein T, Serup P, Eizirik DL, Melloul D. Conditional and specific NF-kappaB blockade protects pancreatic beta cells from diabetogenic agents. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2006;103:5072–5077. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0508166103. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Flodstrom M, Tyrberg B, Eizirik DL, Sandler S. Reduced sensitivity of inducible nitric oxide synthase-deficient mice to multiple low-dose streptozotocin-induced diabetes. Diabetes. 1999;48:706–713. doi: 10.2337/diabetes.48.4.706. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Green LC, Wagner DA, Glogowski J, Skipper PL, Wishnok JS, Tannenbaum SR. Analysis of nitrate, nitrite, and [15N]nitrate in biological fluids. Anal Biochem. 1982;126:131–138. doi: 10.1016/0003-2697(82)90118-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Heimberg H, Heremans Y, Jobin C, Leemans R, Cardozo AK, Darville M, Eizirik DL. Inhibition of cytokine-induced NF-kappaB activation by adenovirus-mediated expression of a NF-kappaB super-repressor prevents beta-cell apoptosis. Diabetes. 2001;50:2219–2224. doi: 10.2337/diabetes.50.10.2219. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hogan FS, Krishnegowda NK, Mikhailova M, Kahlenberg MS. Flavonoid, silibinin, inhibits proliferation and promotes cell-cycle arrest of human colon cancer. J Surg Res. 2007;143:58–65. doi: 10.1016/j.jss.2007.03.080. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Huong PT, Lee MY, Lee KY, Chang IY, Lee SK, Yoon SP, Lee DC, Jeon YJ. Synergistic induction of iNOS by IFN-gamma and glycoprotein isolated from Dioscorea batatas. Korean J Physiol Pharmacol. 2012;16:431–436. doi: 10.4196/kjpp.2012.16.6.431. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jeon YJ, Yang KH, Pulaski JT, Kaminski NE. Attenuation of inducible nitric oxide synthase gene expression by delta 9-tetrahydrocannabinol is mediated through the inhibition of nuclear factor- kappa B/Rel activation. Mol Pharmacol. 1996;50:334–341. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kang JS, Jeon YJ, Kim HM, Han SH, Yang KH. Inhibition of inducible nitric-oxide synthase expression by silymarin in lipopolysaccharide-stimulated macrophages. J Pharmacol Exp Ther. 2002;302:138–144. doi: 10.1124/jpet.302.1.138. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kim S, Choi JH, Lim HI, Lee SK, Kim WW, Kim JS, Kim JH, Choe JH, Yang JH, Nam SJ, Lee JE. Silibinin prevents TPA-induced MMP-9 expression and VEGF secretion by inactivation of the Raf/MEK/ERK pathway in MCF-7 human breast cancer cells. Phytomedicine. 2009a;16:573–580. doi: 10.1016/j.phymed.2008.11.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kim S, Choi MG, Lee HS, Lee SK, Kim SH, Kim WW, Hur SM, Kim JH, Choe JH, Nam SJ, Yang JH, Lee JE, Kim JS. Silibinin suppresses TNF-alpha-induced MMP-9 expression in gastric cancer cells through inhibition of the MAPK pathway. Molecules. 2009b;14:4300–4311. doi: 10.3390/molecules14114300. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kvasnicka F, Biba B, Sevcik R, Voldrich M, Kratka J. Analysis of the active components of silymarin. J. Chromatogr. A. 2003;990:239–245. doi: 10.1016/s0021-9673(02)01971-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Larsen L, Storling J, Darville M, Eizirik DL, Bonny C, Billestrup N, Mandrup-Poulsen T. Extracellular signal-regulated kinase is essential for interleukin-1-induced and nuclear factor kappaB-mediated gene expression in insulin-producing INS-1E cells. Diabetologia. 2005;48:2582–2590. doi: 10.1007/s00125-005-0039-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Letteron P, Labbe G, Degott C, Berson A, Fromenty B, Delaforge M, Larrey D, Pessayre D. Mechanism for the protective effects of silymarin against carbon tetrachloride-induced lipid peroxidation and hepatotoxicity in mice. Evidence that silymarin acts both as an inhibitor of metabolic activation and as a chain-breaking antioxidant. Biochem Pharmacol. 1990;39:2027–2034. doi: 10.1016/0006-2952(90)90625-u. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Li MH, Kothandan G, Cho SJ, Huong PT, Nan YH, Lee KY, Shin SY, Yea SS, Jeon YJ. Magnolol inhibits LPS-induced NF-kappaB/rel activation by blocking p38 kinase in murine macrophages. Korean J Physiol Pharmacol. 2010;14:353–358. doi: 10.4196/kjpp.2010.14.6.353. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Matsuda T, Ferreri K, Todorov I, Kuroda Y, Smith CV, Kandeel F, Mullen Y. Silymarin protects pancreatic beta-cells against cytokine-mediated toxicity: implication of c-Jun NH2-terminal kinase and janus kinase/signal transducer and activator of transcription pathways. Endocrinology. 2005;146:175–185. doi: 10.1210/en.2004-0850. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mereish KA, Bunner DL, Ragland DR, Creasia DA. Protection against microcystin-LR-induced hepatotoxicity by Silymarin: biochemistry, histopathology, and lethality. Pharm Res. 1991;8:273–277. doi: 10.1023/a:1015868809990. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mokhtari MJ, Motamed N, Shokrgozar MA. Evaluation of silibinin on the viability, migration and adhesion of the human prostate adenocarcinoma (PC-3) cell line. Cell Biol Int. 2008;32:888–892. doi: 10.1016/j.cellbi.2008.03.019. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Oh SJ, Jung SP, Han J, Kim S, Kim JS, Nam SJ, Lee JE, Kim JH. Silibinin inhibits TPA-induced cell migration and MMP-9 expression in thyroid and breast cancer cells. Oncol Rep. 2013;29:1343–1348. doi: 10.3892/or.2013.2252. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Oleson BJ, Broniowska KA, Schreiber KH, Tarakanova VL, Corbett JA. Nitric oxide induces ataxia telangiectasia mutated (ATM) protein-dependent gammaH2AX protein formation in pancreatic beta cells. J Biol Chem. 2014;289:11454–11464. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M113.531228. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pliskova M, Vondracek J, Kren V, Gazak R, Sedmera P, Walterova D, Psotova J, Simanek V, Machala M. Effects of silymarin flavonolignans and synthetic silybin derivatives on estrogen and aryl hydrocarbon receptor activation. Toxicology. 2005;215:80–89. doi: 10.1016/j.tox.2005.06.020. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Soto C, Mena R, Luna J, Cerbon M, Larrieta E, Vital P, Uria E, Sanchez M, Recoba R, Barron H, Favari L, Lara A. Silymarin induces recovery of pancreatic function after alloxan damage in rats. Life Sci. 2004;75:2167–2180. doi: 10.1016/j.lfs.2004.04.019. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Soto C, Raya L, Juarez J, Perez J, Gonzalez I. Effect of Silymarin in Pdx-1 expression and the proliferation of pancreatic beta-cells in a pancreatectomy model. Phytomedicine. 2014;21:233–239. doi: 10.1016/j.phymed.2013.09.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Takamura T, Kato I, Kimura N, Nakazawa T, Yonekura H, Takasawa S, Okamoto H. Transgenic mice overexpressing type 2 nitric-oxide synthase in pancreatic beta cells develop insulin-dependent diabetes without insulitis. J Biol Chem. 1998;273:2493–2496. doi: 10.1074/jbc.273.5.2493. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Valenzuela A, Garrido A. Biochemical bases of the pharmacological action of the flavonoid silymarin and of its structural isomer silibinin. Biol Res. 1994;27:105–112. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Welsh N, Sandler S. Interleukin-1 beta induces nitric oxide production and inhibits the activity of aconitase without decreasing glucose oxidation rates in isolated mouse pancreatic islets. Biochem Biophys Res Commun. 1992;182:333–340. doi: 10.1016/s0006-291x(05)80149-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Xie H, Chiles TC, Rothstein TL. Induction of CREB activity via the surface Ig receptor of B cells. J Immunol. 1993;151:880–889. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Xie QW, Kashiwabara Y, Nathan C. Role of transcription factor NF-kappa B/Rel in induction of nitric oxide synthase. J Biol Chem. 1994;269:4705–4708. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yamada K, Otabe S, Inada C, Takane N, Nonaka K. Nitric oxide and nitric oxide synthase mRNA induction in mouse islet cells by interferon-gamma plus tumor necrosis factor-alpha. Biochem Biophys Res Commun. 1993;197:22–27. doi: 10.1006/bbrc.1993.2435. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Youn CK, Park SJ, Li MH, Lee MY, Lee KY, Cha MJ, Kim OH, You HJ, Chang IY, Yoon SP, Jeon YJ. Radi cicol inhibits iNOS expression in cytokine-stimulated pancreatic beta cells. Korean J Physiol Pharmacol. 2013;17:315–320. doi: 10.4196/kjpp.2013.17.4.315. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhang W, Hong R, Tian T. Silymarin’s protective effects and possible mechanisms on alcoholic fatty liver for rats. Biomol Ther. 2013;21:264–269. doi: 10.4062/biomolther.2013.020. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhao J, Sharma Y, Agarwal R. Significant inhibition by the flavonoid antioxidant silymarin against 12-O-tetradecanoylphorbol 13-acetate-caused modulation of antioxidant and inflammatory enzymes, and cyclooxygenase 2 and interleukin-1alpha expression in SENCAR mouse epidermis: implications in the prevention of stage I tumor promotion. Mol Carcinog. 1999;26:321–333. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]