Abstract

There has been limited research on the importance of seasons in the lives of older adults. Previous research has highlighted seasonal fluctuations in physical functioning—including limb strength, range of motion, and cardiac death—the spread of influenza in seasonal migration patterns. In addition, older adults experience isolation for various reasons, such as decline of physical and cognitive ability, lack of transportation, and lack of opportunities for social interaction. There has been much attention paid to the social isolation of older adults, yet little analysis about how the isolation changes throughout the year. Based on findings from an ethnographic study of older adults (n = 81), their family members (n = 49), and supportive professionals (n = 46) as they embark on relocation from their homes, this study analyzes the processes of moving for older adults. It examines the seasonal fluctuations of social isolation because of the effect of the environment on the social experiences of older adults. Isolation occurs because of the difficulty inclement weather causes on social interactions and mobility. The article concludes with discussion of the ways that research and practice can be designed and implemented to account for seasonal variation.

Keywords: relocation, housing/home, qualitative, transition, seasonal fluctuations, social isolation

The interaction of older adults and their living environments remains a key issue in gerontology. Concerns about the appropriateness and affordability of housing environments of this population lead to questions of sustaining older adults in their homes and/or neighborhoods and supporting relocation when preferred or optimal. Aging-in-place and relocation scholars continue to analyze individual functioning and environmental contexts (Lehning, Smith, & Dunkle, 2012; Scharlach, Graham, & Lehning, 2011), building on early scholarship on the interactions of individual competence and environmental press which is defined as the requirements and opportunities from the physical and social environments (Lawton & Nahemow, 1973). Adaptation may result by either increasing an older adult’s competence or lowering the press (i.e., impact of the environment) on an older adult (Lawton & Nahemow, 1973). Environmental press is often defined as the requirements and opportunities from the physical and social environments (Lawton & Nahemow, 1973). Carp and Carp (1984) refined conceptualizations of such interactions by arguing for a hierarchy of individual competences. We continue to refine our conceptions of environment and hope that this article contributes to better understanding the environmental contexts of older adults.

However, the seasonal nature of the interaction of older adults and their physical environments has received less attention in the literature. Although Krout, Moen, Holmes, Oggins, and Bowen (2002) found that climate was one of the general considerations in choosing a Continuing Care Retirement Community for 19.8% of older adults in their study, it ranked lower than other considerations such as medical services or nearness to relatives and friends. In their needs assessment of older adults, Weeks and LeBlanc (2010) identified categories of “adequacy (maintenance)” noting seasonal maintenance concerns of homes (e.g., shoveling snow or winter driving) and the challenge of employing others to assist with these seasonal tasks. Other scholars examining the environmental contexts of older adults have examined consequences of inadequate heating on falls (Luukinen, Koski, & Kivelä, 1996).

Scholars have examined other health and mobility outcomes because of seasonal fluctuations, such as research on vitamin D deficiency contributing to seasonal affective disorder and vitamin C intake leading to increased risk of cardiovascular disease in older adults in the community and in long-term care facilities (Liu et al., 1997; Woodhouse & Khaw, 2000). Studies have examined the differential prevalence of coronary diseases and resulting deaths by seasons (Gerber, Jacobsen, Killian, Weston, & Roger, 2006) as well as prevalence and cost of treatment related to seasonal migration of older adults (Chui, Cohen, & Naumova, 2011; Li & Guo, 2011).

Research on falls and fall prevention has also been examined in seasonal terms. Bird et al. (2013) found that in winter months, ankle strength is decreased. The change in ankle strength leads to a greater likelihood of tripping and/or falls. However, falls may not necessarily predict institutionalization when other activities of daily living are also examined (Dunn, Furner, & Miles, 1993). Scholars have also distinguished among season, climate, and precipitation. Stevens, Thomas, and Sogolow (2007) found that fatalities from falls were more attributable to climate measured by temperature than to season, and Hemenway and Colditz (1990) found that living in winter climates leads to more fractures and falls for White women. Also, addressing the gendered differences for older adults, Dunn et al. (2012) found that walking patterns of females increased with higher temperatures but not for males. In their systematic review of the effect of season and weather on physical activity, Tucker and Gilliland (2007) note that research and interventions on activity for all age groups have not adequately accounted for fluctuations in weather or for alternative programming when outdoor opportunities are limited. This article aims to contribute to the ways fluctuations affect the well-being of older adults.

In addition to research on seasonal fluctuations and older adults, studies on social isolation provide further background. Social isolation in older adulthood constrains the potential to function optimally in the community. Older adults experience isolation for various reasons, ranging from decline of physical and cognitive ability to lack of transportation and lack of opportunities for social interaction. Other scholars have examined social isolation in terms of individual and “interdependence mode” responses (Nicholson, 2009). Scholars have also analyzed distinctions between actual and perceived isolation (Cornwell & Waite, 2009). Although scholars have paid attention to social isolation among older adults, the lived experiences of isolation throughout the year have received little attention.

This article presents qualitative data about seasonal relationships of older adults and their homes, emerging from a study on relocation of older adults set in the Midwestern United States. Seasonal fluctuations affect older adults in three ways: (a) ways the older adults altered their actions, (b) ways members of their kin reacted to seasonal fluctuations, and (c) ways social networks changed their actions affecting the isolation of the older adult. These findings show the specific ways older adults experience seasonal isolation and provide examples of how the built environment influences the interactional opportunities of older adults. Moreover, related to relocation, the seasonal nature of isolation can influence whether older adults move and the timing of their moves.

METHODOLOGY

The study of relocation involved 81 older adults (n = 81), their kin (n = 49), and professionals involved in the moving process (n = 46) from the Midwestern United States. Data were collected from January 2009 to May 2012. Study participants were from a Midwest small town where they lived within 50 miles (either in their premove or postmove location) of a university research center.

The researcher recruited older persons through flyers, and researcher attendance at senior residence community meetings involving older adults, and snowball sampling of community contacts where senior service providers and older adults referred the researcher to potential study participants. Some participants delayed moving or were unable to move because of the Great Recession or other factors. The study period was extended because of these delays. There were 59 females and 22 males in the study. Although 77 of the older participants were White (95.1%), 3 African Americans (3.7%) and 1 Asian (1.2%) also participated in the project. The study involved singles (n = 43) and couples (n = 38) where couples were counted as one older adult in the study. These persons were moving from individual homes, apartments, or, in a few cases, other types of senior housing. Study participants were moving to independent living sections of Continuing Care Retirement Communities, subsidized senior housing, smaller homes, condos, or homes of similar square footage with different layouts more accommodating to their needs (e.g., laundry room on first floor).

Each older adult participant was asked to identify his or her kin who were most involved in the move. Where possible, kin were recruited to participate in the study. Many of the kin were adult children of the older adult who was moving because adult children are more likely than other kin to provide assistance (Wolff & Kasper, 2006). Participants were also asked to identify professionals they were working with in planning their move. Where possible, the researcher observed interactions with the older adult and the professional (e.g., real estate agent).

The specific research questions for the study were as follows:

What are the processes of disbanding their homes and recreating new ones for older adults?

How do older people, their kin, and involved professionals talk about moving?

The study was approved by the Blinded for Review Institutional Review Board. Because of the nature of ethnographic research where the researcher may meet members of the kin network at meals, garage sales, or on moving day, all participants gave permission verbally to participate in the study on meeting the researcher the first time to avoid completing paperwork during these events.

This ethnographic study of the experiences of moving of older adults involved interviews, participant observation, and document review to capture the “holistic view” of moving for older adults. The three stages of moving observed in this study were premove planning, move in-process, and postmove adjustment. Ethnographic fieldwork included moving events such as packing objects, donating objects, preparing objects for garage sales, working at garage sales, planning furniture layout, and assembling furniture. To engage in prolonged contact with the concerns of older adults engaged in moving, Miles and Huberman (1994) suggest that “these situations are typically ‘banal’ or normal ones, reflective of the everyday life” (p. 6). Older adults were interviewed at multiple stages in the study about topics on the timing and motivations of their move, the involvement of their family and professionals, and what they hoped to gain from moving. Kin and professionals were interviewed about their roles and feelings about the move, usually informally during some of the events of moving (garage sales, hanging pictures, etc.). Many of the observations were digitally recorded because conversations about moving could be captured (e.g., during the sorting of items and packing of boxes). At times, photographs were taken at these events. Field notes were also kept about the participant observation experiences by the researcher.

In the anthropological tradition, data analysis involved reviewing of field notes (from participant observations of packing/unpacking, garage sales, and moving day experiences), analyzing digitally recorded interviews selectively transcribed, and reviewing documents (marketing materials collected, sketches, and lists related to moving made by older adults in the study). The themes from the project emerged as the data were iteratively examined. Because of anthropological training and its epistemological emphasis on being open to emergent themes, the researcher did not place “constraints on outputs” (Patton, 2002, p. 39). The researcher engaged study participants both through formal presentations of research findings and individual conversations in preparation for conference presentations to increase the trustworthiness of the data (Rubin & Babbie, 2012). The researcher also triangulated data collection and analysis to further ensure trustworthiness of data (Barusch, Gringieri, & George, 2011; Stake, 2005).

FINDINGS

The findings show that seasonality fluctuations affected the older adult, their kin network, and other members of their social network. Older adults may consciously change their actions because of the season. Also, kin who may be in emotional and logistical caregiving roles may have elevated or different concerns over the course of the seasons. Lastly, members of an older adults’ social network, who may be older persons themselves, may change their actions based on the season.

Seasonal Fluctuations: Impact on Older Persons’ Activities

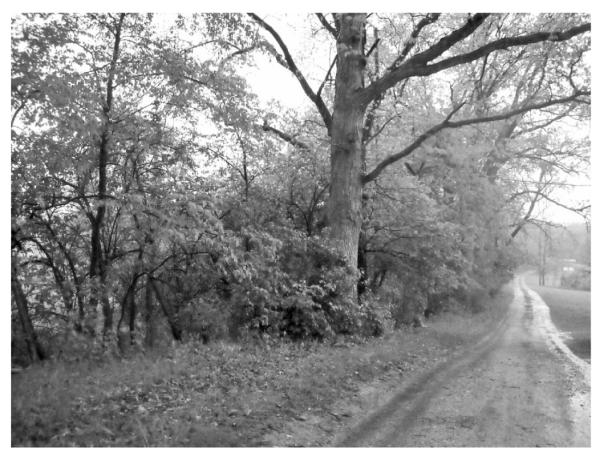

First of all, several older adults mentioned the challenges posed by their homes in the winter. For example, Mrs. Brown, age 82 years at the time of her move, lived on 95 acres, and had been widowed for a few years. She lived in a home that she built with her husband, a renowned photographer. She loved the small town where she raised her two sons but was becoming burdened by her large property. She had a long driveway that needed to be plowed in the winter, and she found it difficult to navigate its deep, muddy rivets when the snow melted in the spring (see Figure 1). The driveway made it difficult for her to leave her home or to have visitors.

Figure 1.

Mrs. Brown’s driveway.

Another older adult, Mrs. McGee, also expressed challenges with her home. In our conversation, she mentions the effect of seasons on her activities. She stopped running in her mid-50s, so walking is now one of her forms of exercise. As a current exercise instructor who leads exercise classes for older adults year round, Mrs. McGee possesses much knowledge about physical fitness. So when she says in Lines 19–20 that she’s seen people who’ve fallen, she has probably worked with them in their rehabilitative phases if they attended her exercise class. She makes the effort (to continue walking in the winter) by being creative about the ways she walks. She drives to a nearby paved road to walk, usually without her dogs.

| 1 | Mrs. McGee: | I don’t like mud very much … |

| 2 | I don’t want them to pave our beautiful, wonderful country |

|

| 3 | road. | |

| 4 | Researcher: | Yeah. |

| 5 | Mrs. McGee: | At this point, I wouldn’t mind if I had a paved road,1 and a paved |

| 6 | driveway. | |

| 7 | Researcher: | So, are you saying to me that in the summer- time, you do walk up, |

| 8 | up and down, or? | |

| 9 | Mrs. McGee: | Oh, yeah, well, I, in good weather, |

| 10 | Researcher: | Yeah, yeah, yeah, yeah. |

| 11 | Mrs. McGee: | I walk … |

| 12 | Researcher: | So, it is a … |

| 13 | … | |

| 14 | Researcher: | Um, okay, so then, not so much the driving, but the walking you, you |

| 15 | Mrs. McGee: | The walking |

| 16 | Researcher: | know the patch, cause you know your road well. |

| 17 | Mrs. McGee: | Yeah. |

| 18 | Researcher: | You’ve been here a long time, that, that you just know. |

| 19 | Mrs. McGee: | Yeah, and that, that can be hard. And, I’m, I’ve seen so many older |

| 20 | people who’ve had falls. | |

| 21 | Researcher: | Oh, yeah. |

| 22 | Mrs. McGee: | And, I, |

| 23 | Researcher: | Yeah. |

| 24 | Mrs. McGee: | so far, I’ve never fallen [knocks on wood], |

| 25 | Researcher: | Yeah. |

| 26 | Mrs. McGee: | and I don’t wanna fall. |

| 27 | Researcher: | Yeah, no that’s rough. The recovery is so … |

| 28 | Mrs. McGee: | It’s very, very bad. And (other dog’s name), being a dog who |

| 29 | throws up, even some days I take him, I have a friend who lives just |

|

| 30 | 2 miles away on (name of road), | |

| 31 | Researcher: | Okay. |

| 32 | Mrs. McGee: | and that’s a paved road, so it’ll be 2 miles away. He can throw up |

| 33 | in the car going over there. | |

| 34 | Researcher: | Oh. |

| 35 | Mrs. McGee: | And, I feel, sometimes, I’ll feel guilty walking without them, and |

| 36 | they don’t get a walk, but I, I do that, I, um, | |

| 37 | Researcher: | Yeah. |

| 38 | Mrs. McGee: | I just drive 2 miles, and walk on her, on her road. |

| 39 | Researcher: | Oh, cause it’s better. |

| 40 | Mrs. McGee: | In the, in the winter. Yeah, ’cause it’s paved. |

| 41 | Researcher: | Yeah, Yeah. |

| 42 | Mrs. McGee: | So, yeah, |

| 43 | Researcher: | Okay. |

| 44 | Mrs. McGee: | I feel a little isolated about walking, |

| 45 | Researcher: | Okay so walking. |

| 46 | Mrs. McGee: | it is nice, just to go out your front door, and that … |

| 47 | Researcher: | Yeah, and when you were younger, you did more, or? |

| 48 | Mrs. McGee: | Well, I, I can’t, well, sometimes, I don’t wanna do it, cause I don’t |

| 49 | want those dogs to be fill-, particularly (dog’s name) to be really filled |

|

| 50 | with mud, and | |

| 51 | Researcher: | Yeah. |

| 52 | Mrs. McGee: | come back in this house, and they just fill it, I’m not a great |

| 53 | Researcher: | Yeah. |

| 54 | Mrs. McGee: | housekeeper. I mean, enough is enough, you know. |

| 55 | Researcher: | (Laughter) |

| 56 | Mrs. McGee: | So, um, I can’t remember what it was like when I was younger. |

In this transcript, Mrs. McGee describes explicit changes in actions during the winter months. These changes involve her considering the precarious nature of her driveway and driving to a friend’s neighborhood where, in her opinion, walking conditions could be safer. However, she also has to modify her pet care. She cannot walk her dogs in the way she prefers because one dog gets carsick. She realizes that if she takes the dog, and the dog enters the house, she will have to clean her dog’s muddy feet. She suggests that she is not a “great housekeeper” (Lines 52–54). Her subsequent statement, “enough is enough,” acknowledges her limitations in desiring exercise, that she will walk, but without her dogs accompanying her.

At the beginning of our interview, she told me about her history with the road. She stated, “I was the one instrumental in getting it to be [designated] a ‘Natural Beauty Road.’” She alludes to a decision when her husband was alive not to pave her road (Lines 2–3). Yet now she would welcome a paved road and a paved driveway (Lines 5–6). Mrs. McGee does not indicate that she acted differently in the past (Line 48) because of her concern of the dogs’ feet muddying her home occurred then, too. Rather, she changes her routine to avoid falls, which she has observed happening to others during the winter season. Although arguably in the preceding examples, this could be a challenge of rural living in addition to seasonal variation, the older adults mentioned explicitly her challenges in the winter.

For Mr. and Mrs. James, ages 84 and 81 years at the time of the interview, who cancelled their move because of financial constraints, they expressed that they might consider moving in the future given that “we could be a burden to the home.” When the researcher asked for further explanation, Mrs. James said, “It’s a, it’s a big house, and it could be overwhelming to us one day.” Mr. James added, “We still been doing it ourselves … Each year it’s getting harder and harder.” He mentioned both the mowing of the lawn and snow shoveling and the costs for both if they were not able to do it themselves. Their comments denote the challenge of caring for their homes through the year and addressing the needs that change with the seasons. Although seasonal fluctuations affected the activities of older adults, for the participants in this study, winter weather seemed to change their routines in pronounced ways. For example, one 91-year-old female said that she goes to aqua aerobics regularly at the recreation center that was free after her 90th birthday, “So I missed very little. I go in any weather except ice. 242 times.” Also, kin expressed more concern in the winter months, as featured in next section.

SEASONAL FLUCTUATIONS: IMPACT ON THE KIN NETWORK

In addition to older adults themselves, their family members discussed the seasonality of housing. In conversations with the family, Mrs. Ash’s daughter, Karen, was deeply concerned about her mother in the winter. She encouraged her mother, age 91 years at time of her move, to relocate before the winter season fell. Given the scope of work to get out of her house, Mrs. Ash wanted to delay moving and stay one last winter in her home of 50 years.

Researcher: It’s happening pretty, pretty quickly after Joe’s passing, if you, not even 1 year.

Mrs. Ash: Yeah it’s not even a year, you’re right.

Researcher: To make all these plans …

Mrs. Ash: And I think the children are, especially Karen, Karen she doesn’t want me to

have another winter in (CITY) because the winters aren’t the easiest season with the

snow and the ice, and, and, the slippery roads. But I am, still functioning. To know

when it’s not to go out.

Mrs. Ash then promised her daughter to be safe when getting the mail every day in the winter season. Her house was on a corner, with the driveway situated on the side of her house and her mailbox facing the street. To satisfy and relieve her out-of-state daughter, Mrs. Ash agreed that, to prevent falls, she would drive to the mailbox rather than walk on her driveway to get the mail. Importantly, she regularly participates in water aerobics classes year round so her daughter would not be worried about her mother’s fitness in walking the distance to the mailbox. The deliberate practice of driving her to her mailbox as a way to keep a promise made to her daughter is an example of the way Mrs. Ash changed her daily habits seasonally.

Another adult daughter compared the various tasks her older father engaged in over the year. She said,

For years I’ve worried, especially when we get a big snowfall … You know, um, mowing the lawn, he’ll take, maybe do the front one day, and the back one day, but, you know, I’m not as worried about the lawn care as snow removal.

When asked if she ever asked him to hire help for snow removal, she said, “Oh, yes.” She added “He will only do it when he’s on like the doctor’s restriction.”

SEASONAL FLUCTUATIONS: IMPACT ON THE SOCIAL NETWORK

In addition to family members, other members of older adults’ social networks may also change their practices based on the seasons. This may lead to fewer opportunities for social interaction for the older adult. For example, Mrs. McGee also disclosed another way the winter season affects her activities. Her friends refuse to come to her home for book club in the winter. Please see transcript in the following text:

| 1 | Mrs. McGee: | When I have friends, |

| 2 | Researcher: | I was actually … |

| 3 | Mrs. McGee: | who don’t like to come out here, I have to teach ‘em to come in the |

| 4 | back way. | |

| 5 | Researcher: | Okay. |

| 6 | Mrs. McGee: | I have a friend who is, she’s in better shape than I am, she’s 4 |

| 7 | years younger, but that curve in the road, | |

| 8 | Researcher: | Yeah, yeah. |

| 9 | Mrs. McGee: | she’s sort of like afraid she’s gonna, in the winter. So, I never have |

| 10 | the book group up here in the winter. Let’s put it that way. |

|

| 11 | Researcher: | Okay, so you, you consciously choose that. Okay. Yeah, yeah. |

| 12 | Mrs. McGee: | Well, because a lot of them wouldn’t come out. |

| 13 | Researcher: | And they tell you that? |

| 14 | Mrs. McGee: | Oh, yeah, well (female name) tells me. |

| 15 | Researcher: | Yeah. |

| 16 | Mrs. McGee: | So, we never have, we never have it here, but so what, so I have to |

| 17 | have my book club in the spring or the fall. | |

| 18 | Researcher: | Yeah. |

| 19 | Mrs. McGee: | (Laughter). |

| 20 | Researcher: | I see. So, yeah, that’s another way, is friends’ reactions to … |

| 21 | Mrs. McGee: | Yeah, but (gentleman friend’s name) does not have an all-wheel |

| 22 | drive, but I think he always seems to get out here. You know. |

In this transcript, Mrs. McGee describes how her particular home, set on a country road, affects her friend’s visits. Her book club friend worries about navigating the winding roads on the way to Mrs. McGee’s home. So she plans to host the group at other times of the year. However, her boyfriend visits regardless of the season (Lines 20–21).

Scholarship about social interactions of older persons continues to address the role of peer interaction. In “Social Relations, Language and Cognition in the ‘Oldest Old,’” Keller-Cohen et al. (2006) explore the relationship between the number and types of interactions of persons 85 years and older and task-based displays of cognitive and language abilities. She suggests that those with fewer interactions with family and a higher proportion of friends scored better on those tasks. This study suggests that family members may communicate and advocate on the older adults’ behalf, overshadowing the need for older adults to communicate themselves at the same level. In her article, she notes:

The advantages were explicitly described by a 90-year-old resident:

A retirement center such as this is a most desirable place for people aged 65 to 100-plus to live. When I was still in my own home, there were days in the winter when I didn’t see anyone: here I have so many friends to talk with whose interests and experiences are much the same as mine. Most people do not realise what a positive experience this can be… . For communication, this is as good as it gets. (Keller-Cohen et al., 2006, p. 598)

Keller-Cohen is one of the few scholars who have offered data on the seasonal isolation of older persons.

DISCUSSION AND IMPLICATIONS

These findings show the seasonal changes in actions of older adults and the members of their social network. Although research has considered the health implications of seasonal variation, less attention has been paid to the ways older adults change their navigation of their social spaces over the course of the year. There is little in the literature about how weather affects the social lives of older adults and how research and services might be altered to address these seasonal changes. I suggest the importance of the lived experience of older adults and exploration of the reduction of social isolation and how these experiences change over the year. Although these findings are exploratory, the links between older adults, their living environments, and seasonal fluctuations provide a new area of investigation for these reasons: (a) we need to better understand seasonality in relation to home environments, social isolation, and social interaction, (b) social service programming might be altered to address seasonal changes, and (c) programs might be introduced to address the seasonal needs of older adults.

First, we can consider seasonality as part of the lived experience of older adults in terms of maintenance tasks and individual and social activities. The maintenance tasks of home and yard ownership fluctuate throughout the year. Many older adults undertake these tasks as they arise. For those older adults with the resources to employ others to do this work, this requires the anticipation of when the work is needed, understanding of the work needed, and compensation for the work, which requires budgeting, and transactions that are smooth and respectful to both parties. These arrangements may not always result in the completion of the work, so backup arrangements may have to be planned. For those older adults who have family support for the work, these tasks may be paid, or technically unpaid, although they could be implicitly bartered for inheritance support in some cases.

We can also examine the ways seasonal fluctuations affect how older people engage in their own activities and engage with others. We need to understand better how older people change what they do, where they go, and who they interact with based on seasons. We can also consider how programs aimed for older adults might be planned and executed differently over the year. Visiting service programs, such as home health care agencies, may consider seasonally driven care, which may take into account the geographical location of older adults, their changing needs, and their homes over the year in designing care plans.

We may also look to other entities that may use technology to develop programs for older adults to reduce seasonal isolation. We may expand existing programs where interfaces with family, peers, and health professionals already work to facilitate checkins through telephone or virtual contacts (Hopp & Hogan, 2009; Milligan, Roberts, & Mort, 2011; Rao, 2013). Programs specifically to facilitate kin relationships are being developed (Moffatt, David, & Baecker, 2012). These extant interventions could be applied with additional attention to differential contacts related to seasons. We may also work with family members and raise concerns with peers about seasonal isolation, encouraging more contacts.

Programs may also be supplemented to pick up older adults and take them to places where exercise, including walking, can be conducted in safer environments, given the increased concerns of falls in winter. Older adults may benefit from the health advantages of physical activity and social connections through these programs. These programs may be particularly important in areas of the country where weather fluctuations are more severe over the course of the year.

There are important implications of changing practices and social interactions resulting from seasonal fluctuations. First of all, although some older adults migrate seasonally to climates that allow them to remain active, many older adults do not have the resources to live and maintain lives in two places. For those older adults with altered actions and interactions, they could report on their well-being in medical and social assessments (e.g., number of times per week engaged in exercise) with great variation. Research on older adults, including studies of social isolation and social interactions, could also be different depending on the season during which the data are collected. Lastly, research on older adults’ relationships to their homes and communities, both addressing aging in place and relocation, could vary depending on the season, including the benefits and difficulties of aging in place and the timing of relocations. As we think of optimal aging as adding life to years, rather than years to life, we might have to amend our outlooks and resultant programs to be more seasonally nuanced.

Older adults experience isolation for various reasons, ranging from decline of physical and cognitive ability to lack of transportation and lack of opportunities for social interaction.

Older adults may consciously change their actions because of the season.

The deliberate practice of driving her to her mailbox as a way to keep a promise made to her daughter is an example of the way Mrs. Ash changed her daily habits seasonally.

As we think of optimal aging as adding life to years, rather than years to life, we might have to amend our outlooks and resultant programs to be more seasonally nuanced.

Acknowledgments

This research was funded by the John A. Hartford Foundation. The author would like to thank Dr. Letha Chadiha for her help in the development of this manuscript.

NOTE

At the beginning of our interview, she told me about her history with the road. She stated, “I was the one instrumental in getting it to be [ designated] a ‘Natural Beauty Road.’”

REFERENCES

- Barusch A, Gringieri C, George M. Rigor in qualitative social work research: An empirical review of strategies used in published articles. Social Work Research. 2011;35(1):11–19. [Google Scholar]

- Bird ML, Hill KD, Robertson IK, Ball MJ, Pittaway J, Williams AD. Serum [25(OH)D] status, ankle strength and activity show seasonal variation in older adults: Relevance for winter falls in higher latitudes. Age and Ageing. 2013;42(2):181–185. doi: 10.1093/ageing/afs067. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Carp FM, Carp A. A complementary/congruence model of well-being or mental health for the community elderly. In: Altman I, Lawton MP, Wohlwill JF, editors. Human Behavior and Environment. Vol. 7: Elderly People and the Environment. Springer Publishing; New York, NY: 1984. pp. 279–336. [Google Scholar]

- Chui KKH, Cohen SA, Naumova EN. Snowbirds and infection—New phenomena in pneumonia and influenza hospitalizations from winter migration of older adults: A spatiotemporal analysis. BMC Public Health. 2011;11(1):444. doi: 10.1186/1471-2458-11-444. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cornwell EY, Waite LJ. Measuring social isolation among older adults using multiple indicators from the NSHAP study. The Journals of Gerontology Series B: Psychological Sciences and Social Sciences. 2009;64(Suppl. 1):i38. doi: 10.1093/geronb/gbp037. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Denzin NK, Lincoln YS. The Sage handbook of qualitative research methods. 3rd ed Sage; Thousand Oaks, CA: 2005. [Google Scholar]

- Dunn JE, Furner SE, Miles TP. Do falls predict institutionalization in older persons? An analysis of data from the Longitudinal Study of Aging. Journal of Aging and Health. 1993;5(2):194–207. doi: 10.1177/089826439300500203. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dunn RA, Shaw W, Trousdale MA. The effect of weather on walking behavior in older adults. Journal of Aging and Physical Activity. 2012;20(1):80–92. doi: 10.1123/japa.20.1.80. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gerber Y, Jacobsen SJ, Killian JM, Weston SA, Roger VL. Seasonality and daily weather conditions in relation to myocardial infarction and sudden cardiac death in Olmsted County, Minnesota, 1979 to 2002. Journal of the American College of Cardiology. 2006;48(2):287–292. doi: 10.1016/j.jacc.2006.02.065. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hemenway D, Colditz GA. The effect of climate on fractures and deaths due to falls among white women. Accident Analysis & Prevention. 1990;22(1):59–65. doi: 10.1016/0001-4575(90)90007-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hopp FP, Hogan M. Community-based tele-health systems for persons with diabetes: Development of an outcomes model. Social Work in Health Care. 2009;48:134–153. doi: 10.1080/00981380802533389. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Keller-Cohen D, Fiori K, Toler A, Bybee D. Social relations, language and cognition in the ‘oldest old.’. Ageing and Society. 2006;26(4):585–605. http://dx.doi.org/10.1017/S0144686X06004910. [Google Scholar]

- Krout JA, Moen P, Holmes HH, Oggins J, Bowen N. Reasons for relocation to a continuing care retirement community. Journal of Applied Gerontology. 2002;21(2):236–256. [Google Scholar]

- Lang FR, Rieckmann N, Baltes MM. Adapting to aging losses: Do Resources facilitate strategies of selection, compensation, and optimization in everyday functioning? The Journals of Gerontology. Series B, Psychological Sciences and Social Sciences. 2002;57(6):501–P509. doi: 10.1093/geronb/57.6.p501. http://dx.doi.org/10.1093/geronb/57.6.P501. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lawton MP, Nahemow L. Ecology and the aging process. In: Eisdorfer E, Lawton MP, editors. Psychology of adult development and aging. American Psychological Association; Washington, DC: 1973. pp. 619–674. [Google Scholar]

- Lehning AJ, Smith RJ, Dunkle RE. Environmental influences on the expectation to age in place: Exploring the EPA Model in Detroit. Paper presented at the 65th annual meeting of the Gerontological Society of America; San Diego. Annenberg Center for Health Sciences; Nov, 2012. [Google Scholar]

- Li S, Guo S. Seasonal migration of metropolitan retirees and rural leisure tourism development in the context of aging society: A study of two villages in Zhejiang province. Paper presented at the International Conference on Computer and Management; CAMAN; 2011. [Google Scholar]

- Liu BA, Gordon M, Labranche JM, Murray TM, Vieth R, Shear NH. Seasonal prevalence of vitamin D deficiency in institutionalized older adults. Journal of the American Geriatrics Society. 1997;45(5):598. doi: 10.1111/j.1532-5415.1997.tb03094.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Luukinen H, Koski K, Kivelä S. The relationship between outdoor temperature and the frequency of falls among the elderly in Finland. Journal of Epidemiology and Community Health. 1996;50(1):107. doi: 10.1136/jech.50.1.107. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Marcoux J. The ‘Casser Maison’ ritual: Constructing the self by emptying the home. Journal of Material Culture. 2001;6(2):312–335. [Google Scholar]

- Miles MB, Huberman AM. Qualitative data analysis: An expanded sourcebook. 2nd ed Sage; Thousand Oaks, CA: 1994. [Google Scholar]

- Milligan C, Roberts C, Mort M. Telecare and older people: Who cares where? Social Science & Medicine. 2011;72(3):347–354. doi: 10.1016/j.socscimed.2010.08.014. http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/j.socscimed.2010.08.014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Moffatt K, David J, Baecker RM. Connecting grandparents and grandchildren. In: Neustaedter C, Harrison S, Sellen A, editors. Connecting families: The impact of new communication technologies on domestic life. Springer Publishing; London, United Kingdom: 2012. pp. 173–193. [Google Scholar]

- Nicholson NR., Jr. Social isolation in older adults: An evolutionary concept analysis. Journal of Advanced Nursing. 2009;65(6):1342–1352. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2648.2008.04959.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Patton MQ. Qualitative research and evaluation methods. 3rd ed Sage; Thousand Oaks, CA: 2002. [Google Scholar]

- Rao S. Sri Rao, CEO of SenseAide, LLC launches first online senior care platform. Press release. 2013 Retrieved from https://www.senseaide.com/pressrelease.php.

- Rowles GD, Oswald F, Hunter EG. Interior living environments in old age. Annual Review of Gerontology & Geriatrics. 2003;23:167–194. [Google Scholar]

- Rubin A, Babbie E. Research methods for social work. 6th ed Thomson Brooks/Cole; Belmont, CA: 2008. [Google Scholar]

- Scharlach A, Graham C, Lehning A. The “village’ model: A consumer-driven approach for aging in place. The Gerontologist. 2011;52:418–427. doi: 10.1093/geront/gnr083. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stake R. Qualitative case studies. In: Denzin NK, Lincoln YS, editors. The Sage handbook of qualitative research methods. 3rd ed Sage; Thousand Oaks, CA: 2005. pp. 443–466. [Google Scholar]

- Stevens JA, Thomas KE, Sogolow ED. Seasonal patterns of fatal and nonfatal falls among older adults in the U.S. Accident Analysis and Prevention. 2007;39(6):1239–1244. doi: 10.1016/j.aap.2007.03.011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tucker P, Gilliland J. The effect of season and weather on physical activity: A systematic review. Public Health. 2007;121(12):909–922. doi: 10.1016/j.puhe.2007.04.009. http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/j.puhe.2007.04.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Weeks LE, LeBlanc K. Housing concerns of vulnerable older Canadians. Canadian Journal on Aging/La Revue Canadienne du Vieillissement. 2010;29(3):333–347. doi: 10.1017/S0714980810000310. http://dx.doi.org/10.1017/S0714980810000310. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wiseman RF. Why older people move. Research on Aging. 1980;2:141–154. [Google Scholar]

- Wolff J, Kasper J. Caregivers of frail elders: Updating a national profile. The Gerontologist. 2006;46(3):344–356. doi: 10.1093/geront/46.3.344. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Woodhouse PR, Khaw KT. Seasonal variation of risk factors for cardiovascular disease and diet in older adults. International Journal of Circumpolar Health. 2000;59(3/4):204–209. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]