Abstract

High body mass index (BMI) has been associated with an increased risk for breast cancer among postmenopausal women. However, the relationship between BMI and breast cancer risk in premenopausal women has remained unclear. Data from two large prevention trials conducted by the National Surgical Adjuvant Breast and Bowel Project (NSABP) were used to explore the relationship between baseline BMI and breast cancer risk. The analyses included 12,243 participants with 253 invasive breast cancer events from the Breast Cancer Prevention Trial (P-1) and 19,488 participants with 557 events from the Study of Tamoxifen and Raloxifene (STAR). Both studies enrolled high-risk women (Gail score ≥ 1.66) with no breast cancer history. Women in P-1 were pre- and postmenopausal, while women in STAR (P-2) were all postmenopausal at entry. Using Cox proportional hazards regression, we found slight but nonsignificant increased risks of invasive breast cancer among overweight and obese postmenopausal participants in STAR and P-1. Among premenopausal participants, an increased risk of invasive breast cancer was significantly associated with higher BMI (p=0.01). Compared to BMI < 25, adjusted hazard ratios for premenopausal women were 1.59 for BMI 25 – 29.9 and 1.70 for BMI ≥ 30. Our investigation among annually screened, high-risk participants in randomized, breast cancer chemoprevention trials showed that higher levels of BMI were significantly associated with increased breast cancer risk in premenopausal women older than age 35, but not postmenopausal women.

Keywords: Breast cancer risk, body mass index, menopausal status, tamoxifen, raloxifene

Introduction

Despite efforts to promote healthy lifestyle choices and to raise awareness about the consequences of excess body weight, overweight and obesity remain important public health challenges in the United States. An alarming two-thirds of Americans are overweight or obese, and more than one-third is obese (1). Excess weight has been linked to an array of medical problems including cardiovascular disease, type 2 diabetes, osteoarthritis, and various types of cancer (1, 2). Since body weight is a modifiable factor, understanding its relationship with breast cancer risk among women could provide helpful insight into the prevention of breast cancer.

In epidemiologic studies, body mass index (BMI) is often the standardized method used for classifying excess weight. BMI is calculated as weight in kilograms divided by height in meters squared. There is extensive evidence in the literature supporting a relationship between increased BMI and an increased risk for breast cancer among postmenopausal women (3-6). However, studies among premenopausal women are sparse and inconsistent. Based on these limited results, some studies have suggested that obesity is protective among premenopausal women (4, 7-9), while others have found no association (6, 10, 11).

The most widely accepted explanation for the BMI and breast cancer risk association among pre- and postmenopausal women is related to estrogen production. In premenopausal women, the ovaries are the primary source of estrogen in the body. After menopause, most circulating estrogen derives from the conversion of adrenal androgens by means of adipose aromatase. Therefore, women with higher amounts of body fat have higher levels of circulating estrogen. Studies have found a stronger relationship between obesity and estrogen receptor (ER)-positive breast cancers than between obesity and ER-negative cancers (12). They have also shown that a history of using postmenopausal hormone therapy (PHT) attenuates the relationship between obesity and breast cancer risk among postmenopausal women (5). Both of these findings provide further evidence for the estrogen availability theory among postmenopausal women. Other biologically plausible explanations include insulin resistance, obesity-induced inflammation, and expression patterns of proteins in mammary epithelial cells (13, 14).

Despite the above explanations, we do not yet know the exact biological mechanisms for the development of breast cancer in obese women. Due to this uncertainty, the proposed theories are laced with speculation (10). Inconsistent results, combined with speculative explanations, underscore the need for more research to clarify the relationship between BMI and breast cancer risk with respect to menopausal status among different populations of women. In this report we use data from two large prospective chemoprevention trials [the Breast Cancer Prevention Trial (P-1) and the Study of Tamoxifen and Raloxifene (STAR, P-2)] conducted by the National Surgical Adjuvant Breast and Bowel Project (NSABP) to explore the relationship between BMI and invasive breast cancer in both pre- and postmenopausal women who are at high risk for developing breast cancer.

Methods

Description of P-1 and STAR

Both P-1 and STAR were two-arm, double-blinded, randomized clinical trials investigating the use of chemoprevention for breast cancer. P-1 opened to accrual June 1, 1992. One-hundred-thirty-one clinical centers throughout North America enrolled 13,388 women by September 30, 1997. Each woman was randomly assigned to receive either placebo or tamoxifen for five years. In March of 1998, the trial was stopped and unblinded as a result of sufficiently strong findings indicating a 49% reduction in breast cancer risk with tamoxifen use (15). A 2005 update of the results with seven years of follow-up showed that tamoxifen remained effective in reducing breast cancer risk for two years after stopping therapy (16).

The NSABP’s second breast cancer prevention trial, STAR, was designed to compare the relative effects of raloxifene to tamoxifen on breast cancer risk as well as other diseases found to be associated with tamoxifen in the P-1 trial. A total of 200 centers throughout North America enrolled and randomized 19,747 participants to STAR between July 1, 1999, and November 4, 2004. The trial results were reported in April 2006 and indicated that raloxifene was as effective as tamoxifen in preventing invasive breast cancer; however, the toxicity and side effect profiles favored raloxifene (17). A 2010 update of the findings indicated that raloxifene maintained 76% of the effectiveness of tamoxifen in preventing invasive breast cancer (i.e., raloxifene was 24% inferior to tamoxifen) and continued to remain less toxic (18). For both trials, all clinical centers obtained approval from institutional review boards, and all participants provided written informed consent.

To be eligible for enrollment into P-1 or STAR, women had to be at least 35 years of age with no history of invasive breast cancer. Women also had to be at high risk for developing breast cancer, which was defined as having a history of lobular carcinoma in situ (LCIS), having a minimum projected 5-year probability of invasive breast cancer (based on the Gail model) of at least 1.66% (19, 20), or, in P-1 only, being age 60 or older. There was no menopausal status exclusion criterion for P-1 participation, but STAR participants were required to be either surgically or naturally postmenopausal. Women were excluded from P-1 and STAR if they had previously undergone a bilateral or unilateral prophylactic mastectomy. Women were also required to have discontinued all use of estrogen or progesterone replacement therapy, oral contraceptives, or androgens for at least three months before random assignment. Other inclusion and exclusion criteria, including certain medications and conditions, along with further details regarding the scientific rationale and additional aspects of the design and recruitment of P-1 and STAR have been previously published (15, 17).

Participants were followed every six months for the first five years and annually thereafter. In order to capture all diagnoses of invasive breast cancer, they received a physical breast examination at each six-month follow-up appointment and bilateral mammograms annually. Staff members from the participating clinical centers were responsible for carrying out participant follow-up and were required to submit documentation for each event reported. The documentation was reviewed centrally by trained medical professionals at the NSABP to confirm the diagnosis of each event.

Study Design

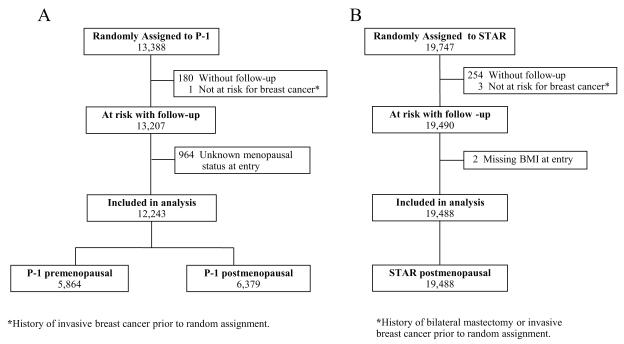

The study included all participants of P-1 and STAR with follow-up information and known menopausal status and BMI at entry. Because a large portion (almost 32%) of women assigned to placebo in P-1 crossed over to active treatment with tamoxifen at the time the findings were reported (March 31, 1998), follow-up data for all P-1 participants were censored at that time, representing an average of 4.1 years of follow-up. Follow-up for the STAR population is based on the data used in the most recent update of the trial (March 31, 2009), representing an average of 6.4 years of follow-up. The flow of participants included in the current study is shown in Figures 1a and 1b. For P-1 participants, menopausal status was inferred from questions about menstrual history at entry. A woman was considered postmenopausal if she reported that both of her ovaries were removed or if she indicated that her menstrual periods had stopped for at least 12 months. For those women with missing information or who underwent a hysterectomy before entry but had at least one intact ovary and were menstruating at the time of their hysterectomy, menopausal status was classified based on each woman’s age at entry. Women younger than age 50 were classified as premenopausal, and women age 60 or older were considered postmenopausal. For women aged 50-59, we could not confidently make any assumptions based on age; consequently, their menopausal status at entry was considered unknown and they were excluded from this evaluation.

Fig 1.

CONSORT diagrams of the Breast Cancer Prevention Trial (P-1) (Fig 1a) and the Study of Tamoxifen and Raloxifene (STAR) (Fig 1b).

In both P-1 and STAR, each participant’s height and weight were measured and recorded by clinical staff members at each participating clinical center. These measurements were used to calculate individual BMIs. For adults, BMI is usually grouped into four categories of weight classification: underweight (<18.5), normal (18.5 – 24.9), overweight (25.0 – 29.9), and obese (≥ 30.0). Because of the low numbers of women falling into the underweight category in our population, it was combined with the normal group to form three categories of BMI for this analysis.

Information about important explanatory variables was also collected at baseline. As an eligibility assessment, participants were required to complete a risk assessment form that gathered information about current age, race, age at menarche, age at first live birth, number of previous breast biopsies, presence of atypical hyperplasia, and number of first-degree relatives with a history of breast cancer. Using these responses, the 5-year predicted breast cancer risk (Gail score) was centrally calculated by the NSABP Biostatistical Center. Other variables, including history of estrogen use, history of oral contraceptive use, history of diabetes, and smoking history, were assessed via questionnaires that had been administered at the time the women entered the original studies.

Statistical Analysis

We used the STAR population to first explore the relationship between BMI and invasive breast cancer in postmenopausal women. We then looked at postmenopausal women from P-1 to see if these results would be consistent. Since P-1 also enrolled women before menopause, we were able to use this group to explore the relationship between BMI and invasive breast cancer in premenopausal women. For each of the groups (i.e., STAR postmenopausal, P-1 postmenopausal, and P-1 premenopausal), we used Cox proportional hazards regression to calculate unadjusted and adjusted hazard ratios of developing invasive breast cancer for overweight (BMI 25.0 – 29.9) and obese (BMI ≥ 30.0) participants compared to those of normal or low weight (BMI < 25.0). Time to invasive breast cancer was calculated as time from randomization to diagnosis of invasive breast cancer or time of last follow-up. Time was censored for those who had undergone a bilateral mastectomy or died during follow-up. P-values for tests for trend were obtained by including BMI as a single ordinal term (with values 0, 1, and 2) in the models and evaluating the global p-value for the term. We first assessed the association between BMI and the risk of breast cancer on a univariable basis, and then we assessed the association utilizing two forms of adjustment for important explanatory variables. The first was achieved using Cox regression modeling that incorporated all key potential variables including treatment, Gail score, age, history of diabetes, history of oral contraceptive use, history of estrogen use, and years of cigarette smoking at entry. We refer to this as the full multivariable model assessment. Because the majority of P-1 and STAR participants are white (94-97%) and race is incorporated into the Gail score, we did not include race/ethnicity as a potential factor. As a second form of adjustment, we used backward elimination to drop out all of the potential variables that did not reach a statistically significant level of p<0.05. We refer to this as the final multivariable model assessment. On the basis of results reported in the literature, we tested for an interaction between BMI and history of estrogen use among postmenopausal women, and an interaction between BMI and history of oral contraceptive use among premenopausal women. Because our populations consisted of women receiving chemopreventive therapy, we decided a priori to conduct analyses separately among treated and untreated women. To assess whether effects of BMI differed by receptor status of the tumor, we conducted separate analyses for ER-positive and ER-negative breast cancers among postmenopausal and premenopausal women. For the analysis of ER-positive breast cancer, we censored the ER-negative cancers and those with unknown ER status at the time of diagnosis. Similar logic was followed when ER-negative breast cancer was the outcome of interest. Assessments of the statistical significance of interactions and effects within treatment groups and by ER status were based on the final multivariable model for the respective study populations. P-values used to assess the statistical significance of parameters in all modeling were determined with the likelihood ratio test. All tests were evaluated using a 2-sided p-value of 0.05. Analyses were performed using SAS version 9.2 software (SAS Institute, Inc).

Results

Entry characteristics for the three groups of participants included in this analysis (i.e., STAR postmenopausal, P-1 postmenopausal, and P-1 premenopausal) by BMI are included in the top portion of Table 1. Among postmenopausal women in STAR and P-1, the mean ages were 58.5 (SD, 7.4) and 60.8 (SD, 7.5) years, respectively. Among the premenopausal women in P-1, the mean age was 46.3 (SD, 4.3) years. STAR participants had higher Gail scores, with a mean 5-year predicted breast cancer risk of 4.03% (SD, 2.2) compared to 3.87% (SD, 2.8) among postmenopausal women and 3.28% (SD, 2.0) among premenopausal women in P-1. Overall, obese women were more likely to have a history of diabetes and less likely to have smoked or to have used oral contraceptives. In addition, obese women tended to have slightly lower Gail scores than women of normal weight. More overweight and obese premenopausal women reported a history of estrogen use, whereas obese postmenopausal women were less likely to have used estrogen. The distributions of tumor characteristics of the cases by BMI are presented in the bottom portion of Table 1. Obese women were slightly more likely to have ER-positive breast cancer than women of normal weight.

Table 1.

Participant characteristics at entry and tumor characteristics for women included in the analyses by body mass index

| STAR Postmenopausal (N=19,488) |

P-1 Postmenopausal (N=6,379) |

P-1 Premenopausal (N=5,864) |

|||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

| |||||||||

| Body Mass Index | Body Mass Index | Body Mass Index | |||||||

| < 25.0 | 25.0–29.9 | ≥ 30.0 | < 25.0 | 25.0–29.9 | ≥ 30.0 | < 25.0 | 25.0–29.9 | < 30.0 | |

| Participant Characteristic (%) | |||||||||

|

| |||||||||

| Total number of participants | 5870 | 6703 | 6915 | 2204 | 2188 | 1987 | 2596 | 1785 | 1483 |

| Age (years) | |||||||||

| <49 | 9.4 | 7.7 | 10.0 | 7.6 | 7.2 | 9.4 | 81.7 | 77.8 | 78.9 |

| 50-59 | 51.0 | 48.9 | 49.8 | 31.1 | 29.5 | 31.1 | 17.6 | 21.6 | 20.6 |

| >60 | 39.6 | 43.4 | 40.2 | 61.3 | 63.3 | 59.6 | 0.7 | 0.7 | 0.5 |

| Treatment | |||||||||

| Placebo | n/a | n/a | n/a | 49.2 | 51.7 | 50.0 | 50.2 | 50.1 | 50.4 |

| Tamoxifen | 50.5 | 49.8 | 49.7 | 50.8 | 48.3 | 50.0 | 49.8 | 49.9 | 49.6 |

| Raloxifene | 49.5 | 50.2 | 50.3 | n/a | n/a | n/a | n/a | n/a | n/a |

| 5-year predicted breast cancer riska | |||||||||

| ≤2.00 | 11.3 | 10.8 | 11.1 | 20.9 | 23.0 | 22.5 | 27.3 | 30.3 | 33.6 |

| 2.01-3.00 | 28.7 | 29.7 | 32.0 | 27.7 | 26.8 | 29.0 | 32.5 | 32.7 | 32.8 |

| 3.01-5.00 | 32.6 | 31.5 | 30.4 | 30.2 | 29.5 | 28.7 | 26.0 | 23.1 | 22.3 |

| ≥ 5.01 | 27.4 | 28.1 | 26.4 | 21.2 | 20.7 | 19.8 | 14.1 | 13.9 | 11.3 |

| History of diabetes | |||||||||

| No | 98.2 | 95.7 | 89.2 | 98.0 | 95.5 | 89.9 | 98.6 | 97.7 | 94.1 |

| Yes | 1.8 | 4.3 | 10.8 | 2.0 | 4.5 | 10.1 | 1.4 | 2.3 | 5.9 |

| History of estrogen use | |||||||||

| No | 25.6 | 26.5 | 30.6 | 45.6 | 45.7 | 51.0 | 89.6 | 86.9 | 88.4 |

| Yes | 74.4 | 73.5 | 69.4 | 54.4 | 54.3 | 49.0 | 10.4 | 13.1 | 11.6 |

| History of oral contraceptive use | |||||||||

| No | 31.8 | 31.9 | 33.8 | 56.2 | 59.5 | 56.8 | 18.5 | 20.6 | 23.3 |

| Yes | 68.2 | 68.1 | 66.2 | 43.8 | 40.5 | 43.2 | 81.5 | 79.4 | 76.7 |

| History of smoking (years) | |||||||||

| None | 55.5 | 55.2 | 55.7 | 53.8 | 56.8 | 57.0 | 53.9 | 51.6 | 56.3 |

| < 15 | 14.1 | 12.5 | 11.9 | 10.0 | 8.9 | 8.6 | 17.7 | 15.4 | 14.8 |

| 15-34 | 19.4 | 21.5 | 21.8 | 21.1 | 21.2 | 21.4 | 27.4 | 31.3 | 27.4 |

| ≥ 35 | 10.3 | 10.1 | 9.9 | 14.7 | 12.9 | 12.6 | 0.8 | 1.5 | 1.3 |

| Unknown | 0.7 | 0.7 | 0.7 | 0.5 | 0.3 | 0.5 | 0.2 | 0.3 | 0.2 |

| Tumor Characteristic (%) | |||||||||

|

| |||||||||

| Total number of cases | 159 | 191 | 207 | 42 | 48 | 37 | 43 | 45 | 38 |

| Tumor size | |||||||||

| ≤ 1.0 | 35.8 | 39.3 | 31.9 | 35.7 | 47.9 | 51.4 | 39.5 | 22.2 | 23.7 |

| 1.1-3.0 | 56.0 | 49.7 | 54.6 | 47.6 | 47.9 | 45.9 | 41.9 | 62.2 | 60.5 |

| ≥ 3.1 | 5.0 | 9.4 | 8.7 | 14.3 | 4.2 | 2.7 | 18.6 | 15.6 | 15.8 |

| Unknown | 3.1 | 1.6 | 4.8 | 2.4 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| Nodal status | |||||||||

| Negative | 74.2 | 73.3 | 71.5 | 69.0 | 70.8 | 81.1 | 65.1 | 57.8 | 60.5 |

| Positive | 21.4 | 21.5 | 24.6 | 23.8 | 22.9 | 13.5 | 32.6 | 37.8 | 31.6 |

| Unknown | 4.4 | 5.2 | 3.9 | 7.1 | 6.3 | 5.4 | 2.3 | 4.4 | 7.9 |

| Estrogen receptor status | |||||||||

| Negative | 25.8 | 25.1 | 23.2 | 21.4 | 16.7 | 21.6 | 25.6 | 40.0 | 26.3 |

| Positive | 68.6 | 73.3 | 74.4 | 71.4 | 72.9 | 73.0 | 62.8 | 55.6 | 65.8 |

| Unknown | 5.7 | 1.6 | 2.4 | 7.1 | 10.4 | 5.4 | 11.6 | 4.4 | 7.9 |

Abbreviations: STAR-Study of Tamoxifen and Raloxifene, P-1-Breast Cancer Prevention Trial.

Determined by the Gail model.

The results of univariable and multivariable analyses of the association between BMI and the risk of developing invasive breast cancer are shown in Table 2 for postmenopausal women and Table 3 for premenopausal women. Of all the potential explanatory variables assessed, only treatment, Gail score, and age were statistically significant in STAR; and only treatment and Gail score were statistically significant in P-1. Among postmenopausal women in STAR, there was a slight but nonsignificant increased risk of invasive breast cancer with increasing levels of BMI (Table 2, first portion). Adjusting for all potential explanatory variables (full multivariable model assessment) or for only those that were statistically significant in the study population (final multivariable model assessment) had negligible effects on the point estimates of the hazard ratios or on the conclusions regarding the tests of trend. Compared to the lowest group (BMI <25.0), the hazard ratios for the two increasing BMI categories from the final multivariable model were 1.04 and 1.16, and the p-value for the trend test was 0.16.

Table 2.

Body mass index and incidence of invasive breast cancer among postmenopausal women

| STAR Postmenopausal | P-1 Postmenopausal | STAR/P-1 Postmenopausal a | |||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Form of Cox Regression Model |

Body mass index | N | No. of Events |

HR | 95% CI | N | No. of Events |

HR | 95% CI | N | No. of Events |

HR | 95% CI |

| Univariable assessment |

< 25.0 | 5870 | 159 | 1.00 | 2204 | 42 | 1.00 | 7883 | 194 | 1.00 | |||

| 25.0–29.9 | 6703 | 191 | 1.06 | 0.86 – 1.30 | 2188 | 48 | 1.21 | 0.80 – 1.84 | 8641 | 228 | 1.08 | 0.89 – 1.30 | |

| ≥ 30.0 | 6915 | 207 | 1.14 | 0.93 – 1.40 | 1987 | 37 | 1.07 | 0.69 – 1.66 | 8633 | 231 | 1.11 | 0.92 – 1.34 | |

| p-value (trend) | 0.22 | 0.74 | 0.29 | ||||||||||

|

| |||||||||||||

| Full multivariable assessmentb |

< 25.0 | 5829 | 159 | 1.00 | 2194 | 42 | 1.00 | 7833 | 194 | 1.00 | |||

| 25.0–29.9 | 6658 | 190 | 1.03 | 0.83 – 1.27 | 2182 | 48 | 1.23 | 0.81 – 1.86 | 8591 | 227 | 1.06 | 0.87 – 1.28 | |

| ≥ 30.0 | 6870 | 206 | 1.13 | 0.92 – 1.40 | 1978 | 36 | 1.07 | 0.68 – 1.67 | 8581 | 229 | 1.12 | 0.92 – 1.36 | |

| p-value (trend) | 0.24 | 0.73 | 0.25 | ||||||||||

|

| |||||||||||||

| Final multivariable assessmentc |

< 25.0 | 5870 | 159 | 1.00 | 2204 | 42 | 1.00 | 7883 | 194 | 1.00 | |||

| 25.0–29.9 | 6703 | 191 | 1.04 | 0.85 – 1.29 | 2188 | 48 | 1.22 | 0.81 – 1.85 | 8641 | 228 | 1.07 | 0.88 – 1.30 | |

| ≥ 30.0 | 6915 | 207 | 1.16 | 0.94 – 1.42 | 1987 | 37 | 1.09 | 0.70 – 1.69 | 8633 | 231 | 1.14 | 0.94 – 1.38 | |

| p-value (trend) | 0.16 | 0.68 | 0.17 | ||||||||||

Abbreviations: STAR-Study of Tamoxifen and Raloxifene, P-1-Breast Cancer Prevention Trial, HR-hazard ratio, CI-confidence interval.

For participants in both P-1 and STAR, only their P-1 data were included.

Adjusted for treatment, Gail score, age, history of diabetes, history of oral contraceptive use, history of estrogen use, and years of cigarette smoking; STAR/P-1 combined also adjusted for trial. Those with unknown smoking status were excluded from analyses.

Adjusted for treatment, Gail score and age in STAR and STAR/P-1 combined; and treatment and Gail score in P-1.

Table 3.

Body mass index and incidence of invasive breast cancer among premenopausal women

| P-1 Premenopausal | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Form of Cox Regression Model |

Body mass index |

N | No. of Events |

HR | 95% CI |

| Univariable assessment |

< 25.0 | 2596 | 43 | 1.00 | |

| 25.0–29.9 | 1785 | 45 | 1.57 | 1.04 – 2.39 | |

| ≥ 30.0 | 1483 | 38 | 1.63 | 1.06 – 2.53 | |

| p-value (trend) | 0.02 | ||||

|

| |||||

| Full multivariable assessmenta |

< 25.0 | 2590 | 43 | 1.00 | |

| 25.0–29.9 | 1780 | 45 | 1.55 | 1.02 – 2.36 | |

| ≥ 30.0 | 1480 | 38 | 1.66 | 1.06 – 2.58 | |

| p-value (trend) | 0.02 | ||||

|

| |||||

| Final multivariable assessmentb |

< 25.0 | 2596 | 43 | 1.00 | |

| 25.0–29.9 | 1785 | 45 | 1.59 | 1.05 – 2.42 | |

| ≥ 30.0 | 1483 | 38 | 1.70 | 1.10 – 2.63 | |

| p-value (trend) | 0.01 | ||||

Abbreviations: P-1-Breast Cancer Prevention Trial, HR-hazard ratio, CI-confidence interval.

Adjusted for treatment, Gail score, age, history of diabetes, history of oral contraceptive use, history of estrogen use, and years of cigarette smoking. Those with unknown smoking status were excluded from analyses.

Adjusted for treatment and Gail score.

When considering the results among P-1 postmenopausal women, the findings were similar to those seen in STAR in that there was no statistically significant trend of breast cancer risk across BMI categories (Table 2, second portion). Again, adjustment for possible explanatory variables had little effect on the point estimates of the hazard ratios or the tests of trend. The hazard ratios for the upper two categories of BMI from the final multivariable model were 1.22 and 1.09, and the p-value for the test of trend was 0.68. Because the results were consistent for postmenopausal women from both STAR and P-1, these two populations were combined to obtain more precise estimates of hazard ratios and confidence intervals (Table 2, last portion). There were 710 participants on the placebo arm of P-1 who were also participants in STAR. These women were only included once in this combined analysis, using the information obtained from their P-1 participation. The hazard ratios across BMI categories from the final multivariable model for the combined population of postmenopausal women were 1.07 and 1.14, and the p-value for the test of trend was 0.17.

The findings for premenopausal women were different than those found for postmenopausal women (Table 3). For this population, all assessments indicated a statistically significant trend of increasing breast cancer risk with increasing categories of BMI. As in the postmenopausal populations, adjustment for explanatory variables had very little effect on the hazard ratio estimates or the conclusions regarding the tests of trend. When considering the final multivariable model, the hazard ratios for the upper BMI categories were 1.59 and 1.70, and the test of trend was statistically significant (p=0.01).

There was no evidence of a significant interaction between BMI and history of estrogen use among STAR/P-1 postmenopausal women (p=0.93), or between BMI and history of oral contraceptive use among premenopausal women (p=0.66). Results from analyses stratified by treatment group are shown in Table 4. When considering the untreated (placebo) group of postmenopausal women, the hazard ratios for the overweight and obese groups were elevated (1.77 and 1.28, respectively), but did not show a statistically significant trend (p=0.36). Among the treated (tamoxifen or raloxifene) groups of postmenopausal women, we found no association between BMI and invasive breast cancer. For raloxifene users, hazard ratios for the two upper categories of BMI were 0.92 and 1.07 (p-value for trend 0.61) and for tamoxifen users, hazard ratios were 1.07 and 1.18 (p-value for trend 0.26). A test of interaction between BMI category and treatment group (treated vs. untreated) among the postmenopausal women was not significant (p=0.09).

Table 4.

Body mass index and incidence of invasive breast cancer by treatment group

| Body mass index |

Raloxifene | Tamoxifen | Placebo | ||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| N | No. of Events |

HR | 95% CI | N | No. of Events |

HR | 95% CI | N | No. of Events |

HR | 95% CI | ||

| STAR/P-1 Postmenopausala | < 25.0 | 2808 | 90 | 1.00 | 3990 | 81 | 1.00 | 1085 | 23 | 1.00 | |||

| 25.0–29.9 | 3256 | 95 | 0.92 | 0.69 – 1.22 | 4254 | 95 | 1.07 | 0.80 – 1.44 | 1131 | 38 | 1.77 | 1.05 – 2.97 | |

| ≥ 30.0 | 3342 | 108 | 1.07 | 0.81 – 1.42 | 4298 | 100 | 1.18 | 0.88 – 1.58 | 993 | 23 | 1.28 | 0.72 – 2.28 | |

| p-value (trend) | 0.61 | 0.26 | 0.36 | ||||||||||

|

| |||||||||||||

| P-1 Premenopausalb | < 25.0 | 1292 | 13 | 1.00 | 1304 | 30 | 1.00 | ||||||

| 25.0–29.9 | 891 | 15 | 1.79 | 0.85 – 3.76 | 894 | 30 | 1.51 | 0.91 – 2.50 | |||||

| ≥ 30.0 | 736 | 15 | 2.33 | 1.10 – 4.90 | 747 | 23 | 1.41 | 0.82 – 2.43 | |||||

| p-value (trend) | 0.02 | 0.17 | |||||||||||

Abbreviations: STAR-Study of Tamoxifen and Raloxifene, P-1-Breast Cancer Prevention Trial, HR-hazard ratio, CI-confidence interval.

Adjusted for Gail score and age.

Adjusted for Gail score

Among premenopausal women, there was also no evidence of an interaction between BMI and treatment group (p=0.59), although premenopausal obese women randomly assigned to tamoxifen had a greater risk of breast cancer than non-obese women. Among those who received tamoxifen therapy, the hazard ratios were 1.79 and 2.33 for overweight and obese women, respectively (p-value for trend 0.02). In the placebo group, there was not a statistically significant association between the risk of breast cancer and BMI (p-value for trend 0.17); but, the hazard ratios for the upper two categories of BMI remained elevated (1.51 and 1.41, respectively).

Table 5 shows the results for ER-positive and ER-negative breast cancers separately. Among postmenopausal women, there is a nonsignificant positive association between BMI and ER-positive breast cancer (hazard ratios of 1.14 and 1.23 for the overweight and obese groups, respectively; p-value for trend 0.07) and no association between BMI and ER-negative breast cancer. Among premenopausal women, there was a statistically significant trend for BMI and ER-positive breast cancer with hazard ratios for the two upper categories of BMI of 1.41 and 1.78 (p-value for trend 0.04). For ER-negative breast cancers, the test of trend was not statistically significant; but, the number of breast cancer events among premenopausal women in each BMI category by ER status was small.

Table 5.

Body mass index and incidence of ER-positive and ER-negative invasive breast cancer

| Body mass index |

ER-Positive Cancer | ER-Negative Cancer | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| N | No. of Events |

HR | 95% CI | N | No. of Events |

HR | 95% CI | ||

| STAR/P-1 Postmenopausala |

< 25.0 | 7883 | 134 | 1.00 | 7883 | 48 | 1.00 | ||

| 25.0–29.9 | 8641 | 167 | 1.14 | 0.91 – 1.43 | 8641 | 53 | 1.00 | 0.68 – 1.48 | |

| ≥ 30.0 | 8633 | 171 | 1.23 | 0.98 – 1.55 | 8633 | 53 | 1.03 | 0.70 – 1.52 | |

| p-value (trend) | 0.07 | 0.88 | |||||||

| P-1 Premenopausalb | < 25.0 | 2596 | 27 | 1.00 | 2596 | 11 | 1.00 | ||

| 25.0–29.9 | 1785 | 25 | 1.41 | 0.82 – 2.43 | 1785 | 18 | 2.52 | 1.19 – 5.33 | |

| ≥ 30.0 | 1483 | 25 | 1.78 | 1.03 – 3.07 | 1483 | 10 | 1.79 | 0.76 – 4.22 | |

| p-value (trend) | 0.04 | 0.12 | |||||||

Abbreviations: STAR-Study of Tamoxifen and Raloxifene, P-1-Breast Cancer Prevention Trial, ER-estrogen receptor, HR-hazard ratio, CI-confidence interval.

Adjusted for treatment, Gail score and age.

Adjusted for treatment and Gail score

Discussion

Our results indicate a statistically significant positive association between the risk of invasive breast cancer and BMI among premenopausal women older than 35 years that were already at high risk for developing breast cancer. Among high risk postmenopausal women in STAR and P-1, we found a slightly increased risk of invasive breast cancer among overweight and obese women, but the association was not significant.

Much concern has been previously raised about the association between estrogen-only and combined estrogen/progestin PHT and breast cancer risk. An observational study from the Women’s Health Initiative (WHI) showed that PHT use, defined as an estrogen-containing pill or patch, attenuated the association between BMI and breast cancer risk among postmenopausal women (5), which is consistent with findings from other studies (4, 6). However, results from two WHI clinical trials that compared estrogen plus progestin (21) and estrogen-only (22) therapy to placebo did not find an interaction between BMI and PHT. We did not have the ability to assess combined estrogen/progestin PHT in this study; but, over half of the P-1 and STAR postmenopausal participants reported a history of estrogen use. This history may help to explain the increase in hazard ratio but lack of significant p-value for obese postmenopausal women randomized to placebo in our study. However, consistent with results from the WHI clinical trials, we did not find a significant interaction between BMI and history of estrogen use among postmenopausal women in our study.

Similarly to PHT, oral contraceptive use has been a concern among premenopausal women. A pooled analysis by van den Brandt and colleagues (4) found that the inverse association between BMI and breast cancer risk was attenuated among women who had ever used oral contraceptives. However, we found no effect of a history of oral contraceptive use among the premenopausal women who participated in the P-1 trial. Researchers have also recently gained interest in exploring possible links between type 2 diabetes and the obesity/breast cancer risk relationship (23, 24). Our study had very small numbers of participants with a history of diabetes (3-6%), and although we tested for significance of this variable in our multivariable model, we were unable to further explore the relationship.

Prior research has suggested that high BMI is more strongly related to ER-positive than to ER-negative breast cancer, particularly among postmenopausal women (9, 12, 25, 26). We assessed whether the effects of BMI differed by receptor status of the tumor in both post- and premenopausal women. We found that among postmenopausal women, although neither reached statistical significance, BMI was more strongly associated with ER-positive breast cancer than ER-negative breast cancer. Among premenopausal women, elevated hazard ratios were seen for both subtypes but a significant trend was only found for ER-positive cancers. These results are consistent and not surprising given that obesity is believed to raise levels of circulating estrogen thereby increasing the risk of ER-positive cancer. Conversely, a recent study found a direct association between abdominal adiposity and ER-negative breast cancer only (27). Our findings for premenopausal women conflict with these results; however, it should be noted that the number of cases by ER status and BMI classifications for premenopausal women in our study were too small to conduct any meaningful evaluations.

According to existing literature, high BMI has been associated with a significantly increased breast cancer risk in postmenopausal women (3, 5, 6) and is believed to be protective in premenopausal women (3, 7, 9, 28). There are some possible explanations for why our results are inconsistent with these findings. One of the most striking differences is that most of the participants in our study were being treated with tamoxifen or raloxifene, which are selective estrogen receptor modulators (SERMs). SERMs reduce the risk of breast cancer by inhibiting estrogen-like activity in the breast. Because of this anti-estrogenic activity, it could be that the use of SERMs alters the biological pathway by which obesity leads to increased breast cancer risk. Although the trend remained nonsignificant, the hazard ratios among postmenopausal women were higher for those taking placebo than for those taking SERMs. The elevated hazard ratios in the placebo group likely concur with prior studies and with the estrogen availability theory. The interaction between BMI and treatment with SERMs was not significant, so we cannot make any definitive conclusions regarding differences by treatment groups. However, the results are suggestive of a possible treatment effect among postmenopausal women and perhaps warrant more investigation in future studies. In premenopausal women, it is unlikely that chemoprevention was the primary reason for our contradictory results since we saw hazard ratios greater than 1.0 for overweight and obese women in both the placebo and treated populations.

Another important difference between the current study and those prior is that our population consisted of women with a high risk for developing breast cancer. Studies have shown that having a family history of breast cancer attenuates the inverse association between obesity and premenopausal breast cancer (4, 12). Thus, there may be some underlying difference in high risk women that influences the effect of BMI on breast cancer risk. In addition, most studies have either censored premenopausal women at the time of menopause or assigned menopausal status at the time of diagnosis of breast cancer. We did not update menopausal status throughout our study, and thus premenopausal women at entry may have been postmenopausal by the time of diagnosis. Another difference is the age of our premenopausal women. A study by Peacock et al. found that the inverse effect of obesity on premenopausal breast cancer risk was present only among women age 35 and younger (29). It is believed that this is likely due to anovulatory cycles and the subsequent decrease in progesterone and estradiol levels (30). In P-1, all women were older than 35 years, and so may have already been experiencing anovulatory cycles thereby washing out the protective effect of obesity. However, a study conducted among premenopausal participants of the Nurses Health Study II (NHS II) found that the inverse association between BMI and breast cancer risk was not explained by menstrual cycle characteristics, infertility due to ovulatory disorders, or probable polycystic ovary syndrome (9).

Finally, we cannot rule out detection bias in other studies. It is more difficult to palpate lumps in obese women with larger breasts than in other women (31). Unless heavier women undergo regular mammographic screening, they may be more likely to have a delayed diagnosis compared to women of normal weight. This delay could push the detection of breast cancer to the postmenopausal stage of life instead of before menopause, causing the association to look stronger among postmenopausal women (9). Invasive breast cancer was the primary endpoint in STAR and P-1 and was therefore clearly defined and accurately documented. Furthermore, all participants were required to undergo regular physical breast examinations and mammographic screenings, making the current study less likely to be influenced by detection bias.

There are several limitations affecting our study. Although STAR and P-1 were large randomized clinical trials with more than 19,000 and 13,000 participants, respectively, the numbers of cases of breast cancer in each population were limited. It would be advantageous to have even larger populations with more cases to adequately explore the relationship between BMI and breast cancer risk by menopausal status, treatment, and ER status. Because most of our participants were treated with tamoxifen or raloxifene, another possible concern is a difference in treatment adherence according to BMI. However, a prior investigation of the P-1 data found no association between BMI and adherence to SERMs (32). Another limitation may be that we did not require blood tests to verify menopausal status in P-1; therefore, we did not know definitively the menopausal status for everyone, and perimenopausal women could have been classified as premenopausal. Because of this limitation, we excluded 964 (7.3%) P-1 participants for whom menopausal status could not be determined (i.e., 50-59 year olds with a prior hysterectomy). Because these women were not missing at random, we compared their BMI and Gail scores to those of the same age group from P-1. The distribution of BMI shifted only slightly with medians of 26.6 and 27.0 for those included and excluded, respectively. Furthermore, the breast cancer risks in these two groups were no different with median Gail scores of 2.66 for those included and 2.72 for those excluded from the analysis. Therefore, it is not likely that the exclusion of these women impacted the results to a meaningful degree.

Another potential criticism may be that we did not control for levels of physical activity, which is related to both obesity and breast cancer (33, 34). Physical activity levels were not collected in STAR, but were collected in P-1. A previous investigation by Land and colleagues with P-1 data found no association between physical activity and invasive breast cancer (35). Finally, although a BMI of 30 or more is a common measure of obesity and is satisfactory for clinical and epidemiological purposes (36), it is unclear whether it is the most ideal marker of obesity for breast cancer prediction. BMI is a measure of general obesity, which has been linked to increased levels of estrogen in postmenopausal women. However, waist circumference and waist-to-hip ratio are better measures of central obesity, which is related to metabolic changes and insulin resistance (27, 37). Information about waist and hip circumference was not collected in STAR, but we were able to explore the relationship between these measurements and invasive breast cancer in P-1 and found no association in the pre- or postmenopausal populations (data not shown). However, more studies with multiple anthropometric measurements are needed to determine which ones may be more accurate markers for breast cancer prediction. Furthermore, we only had measures of BMI at study entry, which may or may not be a true estimate of long-term obesity. Some studies have suggested that BMI at age 18 reflects long-term obesity and thus may be a better marker for breast cancer risk (9, 38). Despite the potential limitations of using BMI as a marker for obesity, the measurements of height and weight used in STAR and P-1 may provide more accuracy than studies that rely on self-reported data.

In our population of high-risk women participating in chemoprevention clinical trials, we found no significant association between breast cancer risk and overweight and obesity among postmenopausal women, and a significant positive association among premenopausal women age 35 and older. These results are inconsistent with previous findings reported in the literature, suggesting that the BMI/breast cancer association may not be the same for all women. To our knowledge, this is the first study to explore the relationship between BMI and invasive breast cancer incidence in a randomized clinical trial population of high risk women who are being routinely screened for breast cancer development. Due to the selective population and the small number of premenopausal breast cancer cases, more studies are needed to clarify the relationship between BMI and menopausal status and the risk of invasive breast cancer. However, our results suggest that overweight and obesity are not protective among premenopausal women in this population and that maintaining a healthy weight is likely beneficial for all women at high risk for developing breast cancer.

Acknowledgments

This work was supported by: Public Health Service grants (U10-CA-12027, U10-CA-69651, U10-CA-37377, and U10-CA-69974) from the National Cancer Institute, Department of Health and Human Services and by AstraZeneca Pharmaceuticals LP and Eli Lilly and Company.

Footnotes

REFERENCES

- 1.Flegal KM, Carroll MD, Ogden CL, Curtin LR. Prevalence and trends in obesity among US adults, 1999-2008. JAMA. 2010;303:235–41. doi: 10.1001/jama.2009.2014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Ogden CL, Yanovski SZ, Carroll MD, Flegal KM. The epidemiology of obesity. Gastroenterology. 2007;132:2087–102. doi: 10.1053/j.gastro.2007.03.052. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Trentham-Dietz A, Newcomb PA, Storer BE, Longnecker MP, Baron J, Greenberg ER, et al. Body size and risk of breast cancer. Am J Epidemiol. 1997;145:1011–9. doi: 10.1093/oxfordjournals.aje.a009057. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.van den Brandt PA, Spiegelman D, Yaun SS, Adami HO, Beeson L, Folsom AR, et al. Pooled analysis of prospective cohort studies on height, weight, and breast cancer risk. Am J Epidemiol. 2000;152:514–27. doi: 10.1093/aje/152.6.514. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Morimoto LM, White E, Chen Z, Chlebowski RT, Hays J, Kuller L, et al. Obesity, body size, and risk of postmenopausal breast cancer: The Women’s Health Initiative (United States) Cancer Causes Control. 2002;13:741–51. doi: 10.1023/a:1020239211145. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Lahmann PH, Hoffmann K, Allen N, van Gils CH, Khaw KT, Tehard B, et al. Body size and breast cancer risk: Findings from the European Prospective Investigation into Cancer And Nutrition (EPIC) Int J Cancer. 2004;111:762–71. doi: 10.1002/ijc.20315. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Vatten LJ, Kvinnsland S. Prospective study of height, body mass index and risk of breast cancer. Acta Oncol. 1992;31:195–200. doi: 10.3109/02841869209088902. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Ursin G, Longnecker MP, Haile RW, Greenland S. A meta-analysis of body mass index and risk of premenopausal breast cancer. Epidemiology. 1995;6:137–41. doi: 10.1097/00001648-199503000-00009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Michels KB, Terry KL, Willett WC. Longitudinal study on the role of body size in premenopausal breast cancer. Arch Intern Med. 2006;166:2395–402. doi: 10.1001/archinte.166.21.2395. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Pichard C, Plu-Bureau G, Neves-E Castro M, Gompel A. Insulin resistance, obesity and breast cancer risk. Maturitas. 2008;60:19–30. doi: 10.1016/j.maturitas.2008.03.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Kaaks R, Van Noord PA, Den Tonkelaar I, Peeters PH, Riboli E, Grobbee DE. Breast-cancer incidence in relation to height, weight and body-fat distribution in the dutch “DOM” cohort. Int J Cancer. 1998;76:647–51. doi: 10.1002/(sici)1097-0215(19980529)76:5<647::aid-ijc6>3.0.co;2-q. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Cleary MP, Grossmann ME. Minireview: Obesity and breast cancer: The estrogen connection. Endocrinology. 2009;150:2537–42. doi: 10.1210/en.2009-0070. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.van Kruijsdijk RC, van der Wall E, Visseren FL. Obesity and cancer: The role of dysfunctional adipose tissue. Cancer Epidemiol Biomarkers Prev. 2009;18:2569–78. doi: 10.1158/1055-9965.EPI-09-0372. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Pilie PG, Ibarra-Drendall C, Troch MM, Broadwater G, Barry WT, Petricoin EF, 3rd, et al. Protein microarray analysis of mammary epithelial cells from obese and non-obese women at high risk for breast cancer: Feasibility data. Cancer Epidemiol Biomarkers Prev. 2011;20:476–82. doi: 10.1158/1055-9965.EPI-10-0847. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Fisher B, Costantino JP, Wickerham DL, Redmond CK, Kavanah M, Cronin WM, et al. Tamoxifen for prevention of breast cancer: Report of the National Surgical Adjuvant Breast and Bowel Project P-1 study. J Natl Cancer Inst. 1998;90:1371–88. doi: 10.1093/jnci/90.18.1371. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Fisher B, Costantino JP, Wickerham DL, Cecchini RS, Cronin WM, Robidoux A, et al. Tamoxifen for the prevention of breast cancer: Current status of the National Surgical Adjuvant Breast and Bowel Project P-1 study. J Natl Cancer Inst. 2005;97:1652–62. doi: 10.1093/jnci/dji372. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Vogel VG, Costantino JP, Wickerham DL, Cronin WM, Cecchini RS, Atkins JN, et al. Effects of tamoxifen vs raloxifene on the risk of developing invasive breast cancer and other disease outcomes: The NSABP Study of Tamoxifen and Raloxifene (STAR) P-2 trial. JAMA. 2006;295:2727–41. doi: 10.1001/jama.295.23.joc60074. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Vogel VG, Costantino JP, Wickerham DL, Cronin WM, Cecchini RS, Atkins JN, et al. Update of the National Surgical Adjuvant Breast and Bowel Project Study of Tamoxifen and Raloxifene (STAR) P-2 trial: Preventing breast cancer. Cancer Prev Res (Phila) 2010;3:696–706. doi: 10.1158/1940-6207.CAPR-10-0076. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Gail MH, Brinton LA, Byar DP, Corle DK, Green SB, Schairer C, et al. Projecting individualized probabilities of developing breast cancer for white females who are being examined annually. J Natl Cancer Inst. 1989;81:1879–86. doi: 10.1093/jnci/81.24.1879. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Costantino JP, Gail MH, Pee D, Anderson S, Redmond CK, Benichou J, et al. Validation studies for models projecting the risk of invasive and total breast cancer incidence. J Natl Cancer Inst. 1999;91:1541–8. doi: 10.1093/jnci/91.18.1541. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Chlebowski RT, Hendrix SL, Langer RD, Stefanick ML, Gass M, Lane D, et al. Influence of estrogen plus progestin on breast cancer and mammography in healthy postmenopausal women: The Women’s Health Initiative Randomized Trial. JAMA. 2003;289:3243–53. doi: 10.1001/jama.289.24.3243. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Stefanick ML, Anderson GL, Margolis KL, Hendrix SL, Rodabough RJ, Paskett ED, et al. Effects of conjugated equine estrogens on breast cancer and mammography screening in postmenopausal women with hysterectomy. JAMA. 2006;295:1647–57. doi: 10.1001/jama.295.14.1647. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.DeCensi A, Gennari A. Insulin breast cancer connection: Confirmatory data set the stage for better care. J Clin Oncol. 2011;29:7–10. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2010.32.3022. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Sinicrope FA, Dannenberg AJ. Obesity and breast cancer prognosis: Weight of the evidence. J Clin Oncol. 2011;29:4–7. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2010.32.1752. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Enger SM, Ross RK, Paganini-Hill A, Carpenter CL, Bernstein L. Body size, physical activity, and breast cancer hormone receptor status: Results from two case-control studies. Cancer Epidemiol Biomarkers Prev. 2000;9:681–7. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Suzuki R, Orsini N, Saji S, Key TJ, Wolk A. Body weight and incidence of breast cancer defined by estrogen and progesterone receptor status--a meta-analysis. Int J Cancer. 2009;124:698–712. doi: 10.1002/ijc.23943. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Harris HR, Willett WC, Terry KL, Michels KB. Body fat distribution and risk of premenopausal breast cancer in the Nurses’ Health Study II. J Natl Cancer Inst. 2011;103:273–8. doi: 10.1093/jnci/djq500. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Hall IJ, Newman B, Millikan RC, Moorman PG. Body size and breast cancer risk in black women and white women: The Carolina Breast Cancer Study. Am J Epidemiol. 2000;151:754–64. doi: 10.1093/oxfordjournals.aje.a010275. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Peacock SL, White E, Daling JR, Voigt LF, Malone KE. Relation between obesity and breast cancer in young women. Am J Epidemiol. 1999;149:339–46. doi: 10.1093/oxfordjournals.aje.a009818. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Key TJ, Pike MC. The role of oestrogens and progestagens in the epidemiology and prevention of breast cancer. Eur J Cancer Clin Oncol. 1988;24:29–43. doi: 10.1016/0277-5379(88)90173-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Cui Y, Whiteman MK, Flaws JA, Langenberg P, Tkaczuk KH, Bush TL. Body mass and stage of breast cancer at diagnosis. Int J Cancer. 2002;98:279–83. doi: 10.1002/ijc.10209. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Land SR, Cronin WM, Wickerham DL, Costantino JP, Christian NJ, Klein WM, et al. Cigarette smoking, obesity, physical activity, and alcohol use as predictors of chemoprevention adherence in the National Surgical Adjuvant Breast and Bowel Project P-1 breast cancer prevention trial. Cancer Prev Res (Phila) 2011;4:1393–400. doi: 10.1158/1940-6207.CAPR-11-0172. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Nasca PC, Pastides H. Fundamentals of Cancer Epidemiology. Second ed Jones and Bartlett Publishers; Canada: 2008. [Google Scholar]

- 34.McTiernan A, Kooperberg C, White E, Wilcox S, Coates R, Adams-Campbell LL, et al. Recreational physical activity and the risk of breast cancer in postmenopausal women: The women’s health initiative cohort study. JAMA. 2003;290:1331–6. doi: 10.1001/jama.290.10.1331. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Land SR, Christian N, Wickerham DL, Costantino JP, Ganz PA. Cigarette smoking, fitness, and alcohol use as predictors of cancer outcomes among women in the National Surgical Adjuvant Breast and Bowel Project (NSABP) Breast Cancer Prevention Trial (BCPT) J Clin Oncol (ASCO Meeting Abstracts) 2011;29(15_suppl):1505. [Google Scholar]

- 36.Rose DP, Vona-Davis L. Interaction between menopausal status and obesity in affecting breast cancer risk. Maturitas. 2010;66:33–8. doi: 10.1016/j.maturitas.2010.01.019. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Harvie M, Hooper L, Howell AH. Central obesity and breast cancer risk: A systematic review. Obes Rev. 2003;4:157–73. doi: 10.1046/j.1467-789x.2003.00108.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Berstad P, Coates RJ, Bernstein L, Folger SG, Malone KE, Marchbanks PA, et al. A case-control study of body mass index and breast cancer risk in white and African-American women. Cancer Epidemiol Biomarkers Prev. 2010;19:1532–44. doi: 10.1158/1055-9965.EPI-10-0025. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]