Abstract

Preeclampsia (PE) is a life-threatening hypertensive disorder of pregnancy associated with decreased circulating aldosterone levels. However, the molecular mechanisms underlying aldosterone reduction in PE remain unidentified. Here we demonstrate that reduced circulating aldosterone levels in the preeclamptic women are associated with the presence of angiotensin II type 1 receptor agonistic autoantibody (AT1-AA) and elevated soluble Fms-like tyrosine kinase-1 (sFlt-1), two prominent pathogenic factors in PE. Using an adoptive transfer animal model of PE, we provide in vivo evidence that the injection of IgG from women with PE, but not IgG from normotensive individuals, resulted in hypertension, proteinuria and a reduction in aldosterone production from 1377±272 pg/ml to 544±92 pg/ml (P<0.05) in pregnant mice. These features were prevented by co-injection with an epitope peptide that blocks antibody-mediated AT1 receptor (AT1R) activation. In contrast, injection of IgG from preeclamptic women into non-pregnant mice induced aldosterone levels from 213±24 pg/ml to 615±48 pg/ml (P<0.05). These results indicate that maternal circulating autoantibody in preeclamptic women is a detrimental factor causing decreased aldosterone production via AT1R activation in a pregnancy-dependent manner. Next, we found that circulating sFlt-1 was only induced in autoantibody-injected pregnant mice but not non-pregnant mice. As such, we further observed vascular impairment in adrenal glands of pregnant mice. Finally, we demonstrated that infusion of VEGF121 attenuated autoantibody-induced adrenal gland vascular impairment resulting in a recovery in circulating aldosterone (from 544±92 to 1110±269 pg/ml, P<0.05). Overall, we revealed that AT1-AA-induced sFlt-1 elevation is a novel pathogenic mechanism underlying decreased aldosterone production in PE.

Keywords: preeclampsia, aldosterone, sFlt-1, angiotensin receptor, agonistic autoantibodies

INTRODUCTION

Preeclampsia (PE) is a serious and common complication of pregnancy and remains a leading cause of maternal and neonatal morbidity and mortality.1-3 It is a multisystem disorder generally appearing after the 20th week of gestation and characterized by hypertension, proteinuria, inflammation and endothelial dysfunction.4-6 Despite intensive research efforts and several large clinical trials, the underlying cause of PE remains a mystery and satisfactory treatment options are lacking.

A growing body of evidence demonstrates that AT1 angiotensin receptor agonistic autoantibodies (AT1-AAs) activate AT1 receptors on a variety of cells and provoke biological responses that are likely to contribute to the pathophysiology of preeclampsia.7-10 Significantly, transfer of either total IgG or affinity purified AT1-AA from preeclamptic women into pregnant mice resulted in hypertension and proteinuria, two hallmark features of PE.11 More recent studies showed that infusion of antibody isolated from rabbits immunized by a specific epitope peptide corresponding to a site on the second extracellular loop of the AT1R into pregnant rats contributes to hypertension and proteinuria.12 Thus, these studies provide strong evidence for a pathophysiological role of AT1-AA in PE. Moreover, using human trophoblast cells in vitro and the in vivo adoptive transfer animal model of PE revealed that AT1-AA contributes to elevated soluble Fms-like tyrosine kinase-1 (sFlt-1), an anti-angiogenic factor believed to contribute to pathophysiology associated with PE.7, 11 Infusion of recombinant vascular endothelial growth factor (VEGF121) serves to neutralize excessive sFlt-1 and thereby significantly ameliorates both hypertension and proteinuria in autoantibody-infused pregnant mice, indicating sFlt-1 is a key mediator of AT1-AA-induced features of PE13. Supporting these animal studies, human studies indicate AT1-AAs are highly associated with preeclampsia and their titers are proportional to disease severity.14 Thus, both human and animal studies support a novel concept that circulating AT1-AA is a pathogenic biomarker contributing to PE.

During normal pregnancy there is a marked expansion in plasma volume and an increase in cardiac output that is associated with a major increase in the concentration of circulating aldosterone. Increased aldosterone levels presumably contribute to sodium retention and the resultant water retention associated with volume expansion during pregnancy.15-17 However, in patients with PE there is an inadequate plasma volume expansion coupled with a suppressed level of aldosterone.18-23 Factors accounting for the reduction in aldosterone production associated with PE are not well understood. The goal of the research presented here was to address the puzzle of reduced aldosterone levels in women with PE relative to normotensive pregnant women. We present evidence that AT1-AA-mediated induction of sFlt-1 results in adrenal gland vascular impairment and decreased aldosterone production, features that can be prevented by infusion of VEGF121.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

An expanded Methods section is available in the Supplementary Methods

Patient samples

Patients admitted to Memorial Hermann Hospital were identified by the obstetrics faculty of the University of Texas Medical School at Houston. Preeclamptic patients were diagnosed with severe disease on the basis of the definition set by the National High Blood Pressure Education Program Working Group Report. Normotensive pregnant women were selected on the basis of having an uncomplicated, normotensive pregnancy with a normal term delivery. The blood samples were collected shortly following diagnosis. The research protocol, including the informed consent form, was approved by the Institutional Committee for the Protection of Human Subjects. The patient clinical data are listed in Table.1 BMI is based on self-reported pre-pregnancy height and weight. Increased BMI is a well-known risk factor for preeclampsia.

Table 1. Patient Clinical Characteristics.

| NT | SEM | PE | SEM | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| n | 12 | 15 | |||

| Age (y) | 28.7 | 2.7 | 27.2 | 2.1 | |

| Race (%) | |||||

| Black | 41.6 | 60.0 | |||

| White | 16.6 | 0.0 | |||

| Hispanic | 41.6 | 40.0 | |||

| Other | 0.0 | 0.0 | |||

| Weeks gestational age | 36.0 | 1.3 | 32.9 | 1.3 | p < 0.01 |

| Gravity | 3.2 | 0.6 | 2.5 | 0.4 | |

| BMI | 30.7 | 1.7 | 35.6 | 2.7 | p < 0.01 |

| Systolic BP (mmHg) | 116.5 | 2.2 | 172.0 | 2.4 | p < 0.01 |

| Diastolic BP (mmHg) | 70.9 | 3.0 | 98.9 | 2.8 | p < 0.01 |

| Proteinuria (mg/24h) | ND | NA | 1699.1 | 466.1 | p < 0.01 |

NT: normotensive individuals; PE: preeclamptic women; BMI: body mass index; BP: blood pressure; ND: non-detectable; NA: non-applicable.

CD34 Immunohistochemistry and quantification

Immunohistochemistry for CD34 was carried out on formalin fixed tissues as previously described24-27. The histological quantification of CD34 was carried out using Image-Pro Plus software (Media Cybernetics, Bethesda, MD). Slides with CD34 staining were examined under 100 x magnification. The microvessels that were examined for CD34 staining were mostly concentrated along the cortico-medullary junction of the adrenal glands and hence only those areas were closely examined for the CD34 staining.

Statistical analysis

Results are expressed as mean ± SEM. All data were subjected to statistical analysis using one-way ANOVA followed by Newman Keuls post hoc test or student’s t-test to determine the significance between groups. Statistical programs were run by GraphPad Prism 5, statistical software (GraphPad, San Diego, CA). Statistical significance was set at P<0.05.

RESULTS

Reduced aldosterone levels are associated with the presence of AT1-AA and elevated circulating sFlt-1 levels in the serum of pregnant women with PE

We used a sensitive luciferase bioassay to detect AT1-AA,14 ELISA for sFlt-1 and EIA for aldosterone to measure their circulating levels in normotensive pregnant women and those with PE. Consistent with earlier reports,18 our present study showed significantly decreased serum aldosterone levels in the PE patients (3602±514 pg/ml) compared to the NT women (5176±417 pg/ml, P<0.05) (Fig. 1A). In contrast, AT1-AA activity and sFlt-1 levels in the sera of women with PE were significantly increased (P<0.05) (Fig. 1B & 1C). Thus, these studies indicate that the presence of AT1-AA and elevated sFlt-1 levels in the circulation of preeclamptic women are associated with reduced circulating adolsterone levels.

Figure 1. Reduced aldosterone levels in sera of women with PE are associated with the presence of AT1-AA and elevation of sFlt-1 levels.

(A) Aldosterone levels in the sera of normotensive pregnant women (NT) and women with preeclampsia (PE) were measured by EIA specific for aldosterone. Aldosterone levels were significantly reduced in PE sera compared to NT sera. (B) AT1-AA levels in NT and PE sera were quantified by an NFAT-Luciferase bioassay that reflects AT1 receptor activation. AT1-AA activity was significantly elevated in IgG prepared from PE compared to NT sera. (C) sFlt-1 levels in NT and PE sera were measured by ELISA. sFlt-1 levels were significantly increased in PE compared to NT sera. * P<0.05 versus NT, n=12 for NT and 15 for PE.

IgG isolated from women with PE leads to decreased aldosterone production in pregnant mice and increased aldosterone production in not non-pregnant mice

We used an antibody-injection model of PE in pregnant mice to determine if aldosterone levels are decreased in this model. Blood pressure and proteinuria significantly increased in the pregnant mice injected with IgG form women with PE (PE-IgG) compared to pregnant mice injected with IgG from normotensive pregnant women (NT-IgG) (142±8 vs. 124±2 mm Hg, 242±27 vs 132±17 μg albumin/mg creatinine both P<0.05) (Fig. 2A&B). Co-injection with losartan (an AT1R antagonist) or a 7aa epitope peptide that inhibits autoantibody-induced AT1 receptor activation prevented autoantibody-induced hypertension and proteinuria (Fig. 2A&B). These findings demonstrate that the autoantibody-induced hypertension and proteinuria in the pregnant mice resulted from AT1 receptor activation.

Figure 2. PE-IgG induced hypertension and proteinuria via AT1R activation in pregnant mice.

(A) Hypertension and (B) proteinuria, two key features of PE, are induced in the PE-IgG-injected pregnant mice. Both of these features were attenuated by co-injection with losartan or a 7aa epitope peptide that corresponds to a site on the second extracellular loop of the AT1R. Blood pressure and proteinura represented here were measured on gestation day 18. * P<0.05 versus NT-IgG treatment. ** P<0.05 versus PE-IgG treatment. n=8-10 injected mice for each experimental group.

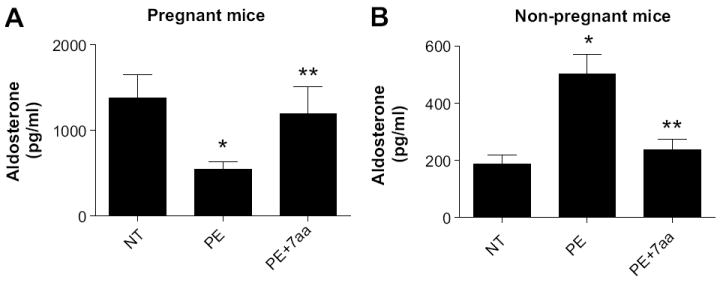

Next, we extended our studies to determine aldosterone levels in the autoantibody–induced preeclamptic mouse model. Aldosterone levels were significantly decreased in the serum of mice injected with PE-IgG (544±92 pg/ml) compared to pregnant mice injected with NT-IgG (1377±272 pg/ml, P<0.01) (Fig. 3A). To determine whether reduced aldosterone levels were dependent on autoantibody-mediated AT1R activation, we co-injected the pregnant mice with PE-IgG and the 7aa epitope peptide.9, 11 We found (Fig. 3A) that co-injection with the 7-aa epitope peptide blunted the reduction in aldosterone levels (1192±318 pg/ml, P<0.05) resulting from injection of PE-IgG. This study provides the first in vivo evidence that IgG circulating in preeclamptic women is a causative factor contributing to reduced aldosterone levels via AT1R activation in pregnant mice. In contrast to the reduction in aldosterone levels we observed in pregnant mice, the injection of PE-IgG into non-pregnant mice resulted in an increase in aldosterone production and its elevation was significantly attenuated by co-injection of the 7aa epitope peptide (Fig. 3B), indicating that AT1-AA is capable of inducing aldosterone production in non-pregnant mice via AT1R activation. Taken together, these results demonstrate that the detrimental effects of PE-IgG on aldosterone production are specific for pregnancy.

Figure 3. PE-IgG injection leads to decreased aldosterone levels in the serum of pregnant mice and increased aldosterone production in non-pregnant mice.

(A) PE-IgG but not NT-IgG significantly reduced maternal circulating adolsterone concentration in the pregnant mice. Pregnant mice were injected with NT-IgG or PE-IgG on gestational days 13 and 14. On gestational day 18, aldosterone levels in the serum of PE-IgG injected pregnant mice were significantly reduced compared to NT-IgG injected pregnant mice. The 7aa epitope peptide co-injection attenuated the reduced aldosterone production in PE-IgG injected mice * P <0.05 compared to NT, ** P<0.05 compared to PE. n = 5-7 injected mice per experimental group. (B) PE-IgG but not NT-IgG significantly induced circulating adosterone concentration in non-pregnant mice. Non-pregnant mice were injected with NT-IgG or PE-IgG on two consecutive days. Five days following the first injection injection, aldosterone levels in the serum of PE-IgG injected non-pregnant mice were significantly induced compared to NT-IgG injected non-pregnant mice. The 7aa epitope peptide co-injection reduced the elevated aldosterone production in PE-IgG injected mice *P<0.05 compared to NT, **P<0.05 compared to PE. n = 6-8 injected mice per experimental group.

Adrenal gland vascular impairment in PE-IgG-injected pregnant mice

In an effort to determine the basis for reduced aldosterone production in PE-IgG injected pregnant mice we isolated adrenal glands from these mice and conducted histological analysis. We observed that the most outer zone of the cortex of adrenal glands, the zona glomerulosa (ZG), which is exclusively responsible for aldosterone production, displayed a highly disorganized pattern in the arrangement of the cellular components, including non-uniform arrangement of the nuclei due to disruption in cellular morphology (Fig. 4, panel A-B). These abnormalities were not observed in the adrenal gland sections in the NT-IgG injected pregnant mice or mice treated with the 7aa epitope peptide (Fig. 4, panel A-B), indicating that PE-IgG-induced disorganization and cellular injury of the ZG layer is mediated by AT1R activation. Under higher magnification, a closer examination of the corticomedullary junction revealed the rich vasculature of the adrenal glands. The region was characterized by branching and spreading of the cortical capillaries in the cortex area of the NT-IgG injected pregnant mice. The presence of the cortical capillaries was diminished and had less branching in the PE-IgG injected mice, compared to the NT-IgG injected mice (Fig. 4, Panel C). Significantly, co-injection of the PE-IgG pregnant mice with the 7aa epitope peptide ameliorated the features seen in the PE-IgG injected mice, resulting in increased presence and branching of the cortical capillaries (Fig. 4, Panel C), demonstrating that PE-IgG leads to vascular impairment in adrenal glands, a feature that was not observed in the NT-IgG injected mice and was prevented by the administration of the 7aa epitope peptide.

Figure 4. Autoantibody-induced cellular and vascular impairment in adrenal glands of pregnant mice can be prevented by 7aa epitope peptide and VEGF121.

(A) Histological analysis of adrenal glands, assessed by H&E staining, indicated that the arrangement of the cellular components within the zona glomerulosa (ZG) layer of the adrenal glands displayed a disorganized and non-uniform pattern in the PE-IgG group compared to NT-IgG group (20X, Scale bar 50 μm). (B) The cellular components, including nuclei, were found to be irregularly placed in patches, shrunken and clustered in PE-IgG injected mice (100X, Scale bar 10 μm). (C) H&E staining showed that the corticomedullary junction area (CA) of the adrenal glands of PE-IgG injected pregnant mice displayed substantially diminished capillaries with less branching compared to the NT-IgG injected mice (100x, Scale bar 10 μm). n=5-7. M: Medulla, C: cortex, ZG: zona glomrulosa; S: sinusoid.

Finally, to accurately measure the effects of PE-IgG on adrenal gland vascularity in pregnant mice, we examined the expression of the CD34 as a vascular marker in the adrenal glands of the mice from all groups. CD34 staining has been used to report the micro-vasculature density in the adrenal glands24-27. Using this approach we detected CD34 in the endothelium of the blood vessels (microvessels) in the sinusoidal areas mostly in the cortico-medullary junction of the adrenal glands (Fig. 5A). Close examination at higher magnification revealed that those microvessels, extending deep into the cortex, were present in abundance in NT-IgG-injected pregnant mice. However, the microvessels stained with CD34 in these areas displayed substantial reduction in size and branching into the cortex in PE-IgG injected pregnant mice (Fig. 5A). Of note, the impaired vasculature seen in the adrenal gland of PE-injected pregnant mice was ameliorated by co-injection with the 7aa epitope peptide (Fig. 5A). Quantitative image analysis of CD34 immunostaining demonstrated significantly less immunoreactivity in adrenal gland sections from mice injected with PE-IgG compared with those from mice injected with NT-IgG or in mice co-injected with PE-IgG and the 7aa epitope peptide (Fig. 5B). Overall, these results indicate that the introduction of PE-IgG into pregnant mice results in adrenal gland vascular impairment.

Figure 5. Antibody-induced vascular impairment in adrenal glands of the pregnant mouse was attenuated by 7aa epitope peptide or VEGF121.

Adrenal gland vascularity was assessed by CD34 immunostaining. (A) CD34 immunostaining showed that CD34 was specifically expressed in the endothelium of the blood vessels (microvessels, MV) in the sinusoidal areas (S) between the cortex and medulla (M). (100x, scale bar 10 μm). Microscopic examination revealed the presence of microvessels at the corticomedullary junction of the adrenal glands. The incidence of microvessels in large areas that branched deeply into the cortex was evident by the CD34 staining in the NT-IgG injected mice. CD34 staining was decreased in the PE-IgG injected pregnant mice and 7aa epitope peptide co-injection or VEGF121 infusion attenuated vascular impairment in these mice. (B) An arbitrary histological quantification of the of CD34 staining. *P<0.05 compared to NT, **P<0.05 compared to PE.

VEGF121 treatment prevents adrenal vascular impairment and improves aldosterone production in adrenal glands of autoantibody-injected mice

Circulating levels of sFlt-1 are elevated in women with PE and in pregnant mice injected with PE-IgG (Fig. 6A). PE IgG-induced production of sFlt-1 is inhibited by co-injection with the 7aa epitope peptide that blocks autoantibody-mediated AT1R activation. sFlt-1 is a potent antagonist of VEGF signaling with detrimental effects on endothelial cells. Thus, it is possible that the anti-angiogenic properties of excessive sFlt-1 produced in the antibody-injection model of preeclampsia in pregnant mice is responsible for the reduced aldosterone observed in this model. To test this possibility, we infused VEGF121 into PE-IgG-injected pregnant mice to neutralize excessive sFlt-1 and potentially prevent autoantibody-mediated reduction in aldosterone.13, 28 Consistent with our earlier studies,13 we found that VEGF121 infusion attenuated autoantibody-induced hypertension (Fig. 6B). We also found that infusion of VEGF121 significantly attenuated PE-IgG induced adrenal damage and impaired vascularity in pregnant mice (Fig. 5A&B). Of significance, VEGF121 treatment of PE-IgG injected pregnant mice resulted in substantially increased aldosterone levels (1110±269 pg/ml) compared to those in the mice injected with PE-IgG alone (544±92 pg/ml) (Fig. 6C). These findings suggest that AT1-AA mediated sFlt-1 elevation underlies reduced aldosterone production by promoting adrenal gland vascular damage in the pregnant mice.

Figure 6. VEGF121 infusion prevented the PE-IgG-induced hypertension and reduction of aldosterone production in pregnant mice.

(A) sFlt-1 levels in the serum were significantly increased in pregnant mice compared to non-pregnant mice and further induced in the PE-IgG-injected pregnant mice (PE) compared to NT-IgG injected pregnant mice (NT). The 7aa epitope peptide coinjection (PE+7aa) attenuated PE-IgG-mediated sFlt-1 induction in the serum of pregnant mice. *P<0.05 compared to non-pregnant mice, **P<0.05 compared to NT. ***P<0.05 compared to PE. n = 6 or 7 injected mice per experimental group. (B) VEGF121 infusion significantly attenuated PE-IgG-induced hypertension in pregnant mice. Pregnant mice were injected with either PE-IgG or NT-IgG on gestation days 13.5 and 14.5. Some of the PE-IgG injected mice were continuously infused with VEGF121. Blood pressure was determined immediately prior to the initial injection and at 3 and 5 days following the initial injection. *P<0.05 compared to NT, **P<0.05 compared to PE. n = 5 or 6 mice per experimental group. (C) Aldosterone levels in the serum of PE-IgG injected pregnant mice were significantly reduced compared to NT-IgG injected pregnant mice. VEGF121 infusion attenuated the reduction in aldosterone production in PE-IgG injected mice *P<0.05 compared to NT, **P<0.05 compared to PE. n = 5-7 injected mice per experimental group. (D) Working model of AT1-AA in preeclampsia. Our findings suggest that AT1-AA contributes to reduced aldosterone production via elevated sFlt-1 production which contributes to adrenal gland vascular impairment and reduced aldosterone production. AT1-AA-mediated induction of sFlt-1 and the resulting inhibition of VEGF signaling also has detrimental effects on renal and vascular function leading to proteinuria and hypertension. Overall, AT1-AA is a detrimental factor contributing to multiple features associated with PE in a sFlt-1-dependent manner that is based on interference with VEGF signaling. Thus, interfering with AT1-AA-mediated AT1R receptor activation or neutralizing the effects of increased sFlt-1 by the infusion of VEGF121 represent important therapeutic possibilities for PE.

DISCUSSION

Normal human pregnancy, in comparison to the non-pregnant state, is characterized by elevated aldosterone levels in the circulation.15, 16 In contrast, pregnancies complicated by PE are associated with reduced levels of aldosterone, in comparison to normotensive pregnancies.19, 20 The causative factors responsible for reduced aldosterone production in PE are unidentified. In this study, we have provided evidence that reduced aldosterone levels are associated with the presence of circulating AT1-AA and elevated sFlt-1 levels in the sera of preeclamptic women. Using an adoptive transfer animal model of PE, we show that the injection of IgG from women with preeclampsia, in contrast to IgG from normotensive pregnant women, results in hypertension, proteinuria and a reduction in aldosterone production. These features were prevented when mice were co-injected with an antibody blocking 7aa epitope peptide, indicating that these features, including the reduction in aldosterone levels, resulted from antibody-mediated AT1 receptor activation. Significantly, these features were also mitigated by infusion of VEGF121 to neutralize the effects of excessive sFlt-1. Overall, our findings support a model in which AT1-AA in preeclamptic women is a pathogenic factor responsible for reduced aldosterone levels.

Because AT1-AA acts like a functional mimic of Ang II, and Ang II is known to stimulate aldosterone release from the adrenal glands, one would expect that the introduction of AT1-AA into mice would result in increased production of aldosterone. Based on this expectation we were not surprised to see that AT1-AA stimulated aldosterone production when injected into non-pregnant mice. However, the introduction of AT1-AA into pregnant mice resulted in reduced aldosterone levels, a feature associated with PE as shown here by us and previously by others10. Evidence provided here suggests that elevated sFlt-1in PE may contribute to adrenal gland vascular impairment and reduced aldosterone production. Normal pregnancy leads to an increase in sFlt-1 production compared to the non-pregnant state. However, sFlt-1 levels are further increased in preeclampsia compared to normotensive pregnancy. Our earlier studies showed that AT1-AA-mediated activation of AT1Rs contributes to elevated sFlt-1 production from the placenta in a mouse model of preeclampsia16,20. Thus, it is possible that the AT1-AA-mediated increase in circulating sFlt-1 is a pregnancy-specific factor responsible for reduced aldosterone production. Supporting this possibility, we report here that the adrenal glands of autoantibody-injected pregnant mice display vascular impairment, associated with reduced aldosterone production. Second, we provide in vivo evidence that neutralizing elevated sFlt-1 by infusion of VEGF121 resulted in improved adrenal gland vascularity associated with increased aldosterone production. Thus, our studies suggest a role for AT1-AA in adrenal gland vascular impairment and subsequent reduction of aldosterone production in PE-IgG injected pregnant mice. It is noteworthy that PE-IgG induces sFlt-1 production only in pregnant mice, not non-pregnant mice. Thus, in the absence of sFlt-1 induction in non-pregnant mice, PE-IgG injection did not result in adrenal gland vascular impairment, but rather mediated an increase in aldosterone production via AT1R activation. Overall our findings support the hypothesis that autoantibody-mediated induction of sFlt-1 is a novel pathogenic mechanism promoting adrenal gland vascular impairment leading to decreased aldosterone production in pregnant mice and that the decline in aldosterone levels and adrenal gland vascular impairment can be prevented by infusion of VEGF121 (Fig. 6D).

In a normal pregnancy the zona glomerulosa of the maternal adrenal gland remains responsive to the agonistic action of Ang II and aldosterone secretion increases as Ang II levels rise during pregnancy.15, 19 However, the maternal vasculature is somewhat unresponsive to the pressor effects of Ang II, a feature consistent with the initial drop in blood pressure early in pregnancy.29, 30 These two phenomena work together (i.e., decreased Ang II pressor response and increased aldosterone production) to achieve an expansion of blood volume during pregnancy while maintaining control of blood pressure. In contrast, an increased responsiveness to the pressor effects of Ang II and a decrease in the production of aldosterone are observed in PE. These changes are associated with increased blood pressure and decreased plasma volume.20, 21 Similar to preeclamptic women, we found that aldosterone production is reduced, while blood pressure is increased in autoantibody-injected pregnant mice. As explained in the following paragraph we believe that the inhibitory effect of PE-IgG injection on aldosterone production is due to anti-angiogenic effects of excessive sFlt-1 produced by the placentas of pregnant mice.

It is well-known that VEGF is produced by steroidogenic cells of the adrenal cortex and that VEGF receptors are present on adreno-cortical capillary endothelial cells 31-33. Earlier studies have shown that VEGF exerts paracrine control over the vasculature of the adult adrenal cortex where it plays a critical role in maintaining the dense and fenestrated vascular bed of the adrenal cortex34. We believe that the disruption of paracrine VEGF signaling in the adrenal cortex by excessive concentrations of the VEGF antagonist, sFlt-1, is detrimental to adrenal vascular homeostasis. This view is supported by our data showing that the detrimental effects of AT1-AA on adrenal-cortical vasculature and aldosterone production are corrected by infusion of VEGF121, to overcome the inhibitory effects of sFlt-1. We do not believe that the activation of adrenal AT1 receptors by AT1-AA is directly responsible for adrenal gland impairment and reduced aldosterone production in pregnant mice. Instead we propose that the autoantibody-induced production of excessive sFlt-1 by the placentas of pregnant mice results in the disruption of paracrine VEGF signaling required for adrenal vascular homeostasis.

Earlier studies have demonstrated detrimental effects of excessive sFlt-1 on kidneys, resulting in glomerular endotheliosis and renal dysfunction, manifested as proteinuria.35, 36 Previous studies from our lab have shown that AT1-AA-mediated kidney injury in pregnant mice is dependent on antibody-induced sFlt-1 production since VEGF121 infusion significantly reduced autoantibody-induced proteinuria and kidney injury.13 We show here that AT1-AA mediated sFlt-1 induction also contributes to impaired adrenal vasculature and decreased aldosterone production in pregnant mice, features that are reversed by administration of VEGF121. Taken together, our current studies support a novel working model in which AT1-AA-mediated kidney and adrenal gland dysfunction in pregnant mice is dependent on the anti-angiogenic consequences of excessive placenta-derived sFlt-1. The use of VEGF121 to overcome the detrimental effects of excessive sFlt-1 has significant therapeutic potential.

Perspectives

Here we report that maternal circulating AT1-AA levels are associated with elevated sFlt-1 and reduced aldosterone levels in the sera of preeclamptic women. In vivo adoptive transfer studies led to unexpected findings that AT1-AA contributes to the reduction of aldosterone production as seen in preeclamptic women. Intriguing, we further discovered that AT1-AA-mediated reduction of aldosterone is associated with adrenal gland vascular impairment, a feature attributed to AT1-AA-mediated sFlt-1 induction. Significantly, infusion of VEGF121 to neutralize elevated sFlt-1 production prevented AT1-AA-induced hypertension and adrenal vascular impairment and resulted in the recovery of aldosterone production in pregnant mice. Overall, our findings reveal novel factors and signaling cascades involved in decreased aldosterone production in PE and highlight possible therapeutic interventions in the management of PE.

Supplementary Material

NOVELTY AND SIGNIFICANCE.

1) What is new

A mechanism accounting for decreased aldosterone production in preeclampsia is discovered.

2) What is relevant

Preeclampsia is associated with inadequate plasma volume expansion, a feature due in part to reduced aldosterone production.

A potential therapeutic approach for preventing the reduction in aldosterone is illustrated.

3) Summary

Using an adoptive transfer animal model of PE, we show that the injection of IgG from women with preeclampsia, in contrast to IgG from normotensive pregnant women, results in hypertension, proteinuria and a reduction in aldosterone production. We show that these features, including the reduction in aldosterone levels, resulted from antibody-mediated AT1 receptor activation. These features were reversed by infusion of VEGF121 to neutralize the effects of excessive sFlt-1. Overall, our findings indicate that pathogenic autoantibodies associated with PE contribute to reduced aldosterone levels.

Acknowledgments

Sources of Funding

Support for this work was provided by the National Institute of Health grants HL076558, HD34130 and RC4HD067977. American Heart Association Grant 10GRNT3760081, March of Dimes (6-FY06-323) and the Texas Higher Education Coordinating Board.

Abbreviation

- AT1-AA

angiotensin type 1 receptor activating autoantibody

- NT

normotensive

- PE

preeclampsia

- AT1R

angiotensin type 1 receptor

- sFlt-1

soluble Fms-like tyrosine kinase-1

Footnotes

Disclosures

None.

References

- 1.Roberts JM, Pearson G, Cutler J, Lindheimer M. Summary of the nhlbi working group on research on hypertension during pregnancy. Hypertension. 2003;41:437–445. doi: 10.1161/01.HYP.0000054981.03589.E9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Sibai B, Dekker G, Kupferminc M. Pre-eclampsia. Lancet. 2005;365:785–799. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(05)17987-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Lindheimer MD, Umans JG. Explaining and predicting preeclampsia. N Engl J Med. 2006;355:1056–1058. doi: 10.1056/NEJMe068161. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Young BC, Levine RJ, Karumanchi SA. Pathogenesis of preeclampsia. Annu Rev Pathol. 5:173–192. doi: 10.1146/annurev-pathol-121808-102149. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Maynard SE, Min JY, Merchan J, Lim KH, Li J, Mondal S, Libermann TA, Morgan JP, Sellke FW, Stillman IE, Epstein FH, Sukhatme VP, Karumanchi SA. Excess placental soluble fms-like tyrosine kinase 1 (sflt1) may contribute to endothelial dysfunction, hypertension, and proteinuria in preeclampsia. J Clin Invest. 2003;111:649–658. doi: 10.1172/JCI17189. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Maynard SE, Venkatesha S, Thadhani R, Karumanchi SA. Soluble fms-like tyrosine kinase 1 and endothelial dysfunction in the pathogenesis of preeclampsia. Pediatr Res. 2005;57:1R–7R. doi: 10.1203/01.PDR.0000159567.85157.B7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Zhou CC, Ahmad S, Mi T, Abbasi S, Xia L, Day MC, Ramin SM, Ahmed A, Kellems RE, Xia Y. Autoantibody from women with preeclampsia induces soluble fms-like tyrosine kinase-1 production via angiotensin type 1 receptor and calcineurin/nuclear factor of activated t-cells signaling. Hypertension. 2008;51:1010–1019. doi: 10.1161/HYPERTENSIONAHA.107.097790. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Xia Y, Wen H, Bobst S, Day MC, Kellems RE. Maternal autoantibodies from preeclamptic patients activate angiotensin receptors on human trophoblast cells. J Soc Gynecol Investig. 2003;10:82–93. doi: 10.1016/s1071-5576(02)00259-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Wallukat G, Homuth V, Fischer T, Lindschau C, Horstkamp B, Jupner A, Baur E, Nissen E, Vetter K, Neichel D, Dudenhausen JW, Haller H, Luft FC. Patients with preeclampsia develop agonistic autoantibodies against the angiotensin at1 receptor. J Clin Invest. 1999;103:945–952. doi: 10.1172/JCI4106. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Dechend R, Homuth V, Wallukat G, Kreuzer J, Park JK, Theuer J, Juepner A, Gulba DC, Mackman N, Haller H, Luft FC. At(1) receptor agonistic antibodies from preeclamptic patients cause vascular cells to express tissue factor. Circulation. 2000;101:2382–2387. doi: 10.1161/01.cir.101.20.2382. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Zhou CC, Zhang Y, Irani RA, Zhang H, Mi T, Popek EJ, Hicks MJ, Ramin SM, Kellems RE, Xia Y. Angiotensin receptor agonistic autoantibodies induce pre-eclampsia in pregnant mice. Nat Med. 2008;14:855–862. doi: 10.1038/nm.1856. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Wenzel K, Rajakumar A, Haase H, Geusens N, Hubner N, Schulz H, Brewer J, Roberts L, Hubel CA, Herse F, Hering L, Qadri F, Lindschau C, Wallukat G, Pijnenborg R, Heidecke H, Riemekasten G, Luft FC, Muller DN, Lamarca B, Dechend R. Angiotensin ii type 1 receptor antibodies and increased angiotensin ii sensitivity in pregnant rats. Hypertension. 2011;58:77–84. doi: 10.1161/HYPERTENSIONAHA.111.171348. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Siddiqui AH, Irani RA, Zhang Y, Dai Y, Blackwell SC, Ramin SM, Kellems RE, Xia Y. Recombinant vascular endothelial growth factor 121 attenuates autoantibody-induced features of pre-eclampsia in pregnant mice. Am J Hypertens. 2010;24:606–612. doi: 10.1038/ajh.2010.247. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Siddiqui AH, Irani RA, Blackwell SC, Ramin SM, Kellems RE, Xia Y. Angiotensin receptor agonistic autoantibody is highly prevalent in preeclampsia: Correlation with disease severity. Hypertension. 2010;55:386–393. doi: 10.1161/HYPERTENSIONAHA.109.140061. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Skinner SL, Lumbers ER, Symonds EM. Analysis of changes in the renin-angiotensin system during pregnancy. Clin Sci. 1972;42:479–488. doi: 10.1042/cs0420479. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Irani RA, Xia Y. Renin angiotensin signaling in normal pregnancy and preeclampsia. Seminars in nephrology. 2009;31:47–58. doi: 10.1016/j.semnephrol.2010.10.005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Elsheikh A, Creatsas G, Mastorakos G, Milingos S, Loutradis D, Michalas S. The rennin-aldosterone system during normal and hypertensive pregnancy. Arch Gynecol Obstet. 2001;264:182–185. doi: 10.1007/s004040000104. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Bussen SS, Sutterlin MW, Steck T. Plasma renin activity and aldosterone serum concentration are decreased in severe preeclampsia but not in the hellp-syndrome. Acta Obstet Gynecol Scand. 1998;77:609–613. doi: 10.1034/j.1600-0412.1998.770606.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Langer B, Grima M, Coquard C, Bader AM, Schlaeder G, Imbs JL. Plasma active renin, angiotensin i, and angiotensin ii during pregnancy and in preeclampsia. Obstet Gynecol. 1998;91:196–202. doi: 10.1016/s0029-7844(97)00660-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.de Groot CJ, Taylor RN. New insights into the etiology of pre-eclampsia. Ann Med. 1993;25:243–249. doi: 10.3109/07853899309147870. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Escher G, Mohaupt M. Role of aldosterone availability in preeclampsia. Molecular aspects of medicine. 2007;28:245–254. doi: 10.1016/j.mam.2007.03.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Irani RA, Xia Y. Renin angiotensin signaling in normal pregnancy and preeclampsia. Seminars in nephrology. 2011;31:47–58. doi: 10.1016/j.semnephrol.2010.10.005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Gennari-Moser C, Khankin EV, Schuller S, Escher G, Frey BM, Portmann CB, Baumann MU, Lehmann AD, Surbek D, Karumanchi SA, Frey FJ, Mohaupt MG. Regulation of placental growth by aldosterone and cortisol. Endocrinology. 2011;152:263–271. doi: 10.1210/en.2010-0525. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Magennis DP, McNicol AM. Vascular patterns in the normal and pathological human adrenal cortex. Virchows Arch. 1998;433:69–73. doi: 10.1007/s004280050218. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Bernini GP, Moretti A, Bonadio AG, Menicagli M, Viacava P, Naccarato AG, Iacconi P, Miccoli P, Salvetti A. Angiogenesis in human normal and pathologic adrenal cortex. The Journal of clinical endocrinology and metabolism. 2002;87:4961–4965. doi: 10.1210/jc.2001-011799. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Zielke A, Middeke M, Hoffmann S, Colombo-Benkmann M, Barth P, Hassan I, Wunderlich A, Hofbauer LC, Duh QY. Vegf-mediated angiogenesis of human pheochromocytomas is associated to malignancy and inhibited by anti-vegf antibodies in experimental tumors. Surgery. 2002;132:1056–1063. doi: 10.1067/msy.2002.128613. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Favier J, Plouin PF, Corvol P, Gasc JM. Angiogenesis and vascular architecture in pheochromocytomas: Distinctive traits in malignant tumors. The American journal of pathology. 2002;161:1235–1246. doi: 10.1016/S0002-9440(10)64400-8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Gilbert JS, Verzwyvelt J, Colson D, Arany M, Karumanchi SA, Granger JP. Recombinant vascular endothelial growth factor 121 infusion lowers blood pressure and improves renal function in rats with placental ischemia-induced hypertension. Hypertension. 2010;55:380–385. doi: 10.1161/HYPERTENSIONAHA.109.141937. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Pepe GJ, Albrecht ED. Actions of placental and fetal adrenal steroid hormones in primate pregnancy. Endocr Rev. 1995;16:608–648. doi: 10.1210/edrv-16-5-608. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Walsh SW. Progesterone and estradiol production by normal and preeclamptic placentas. Obstet Gynecol. 1988;71:222–226. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Feraud O, Mallet C, Vilgrain I. Expressional regulation of the angiopoietin-1 and -2 and the endothelial-specific receptor tyrosine kinase tie2 in adrenal atrophy: A study of adrenocorticotropin-induced repair. Endocrinology. 2003;144:4607–4615. doi: 10.1210/en.2003-0099. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Mallet C, Feraud O, Ouengue-Mbele G, Gaillard I, Sappay N, Vittet D, Vilgrain I. Differential expression of vegf receptors in adrenal atrophy induced by dexamethasone: A protective role of acth. American journal of physiology Endocrinology and metabolism. 2003;284:E156–167. doi: 10.1152/ajpendo.00450.2001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Taniguchi A, Tajima T, Nonomura K, Shinohara N, Mikami A, Koyanagi T. Expression of vascular endothelial growth factor and its receptors flk-1 and flt-1 during the regeneration of autotransplanted adrenal cortex in the adrenalectomized rat. The Journal of urology. 2004;171:2445–2449. doi: 10.1097/01.ju.0000127755.87490.37. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Vittet D, Ciais D, Keramidas M, De Fraipont F, Feige JJ. Paracrine control of the adult adrenal cortex vasculature by vascular endothelial growth factor. Endocrine research. 2000;26:843–852. doi: 10.3109/07435800009048607. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Schrijvers BF, Flyvbjerg A, De Vriese AS. The role of vascular endothelial growth factor (vegf) in renal pathophysiology. Kidney Int. 2004;65:2003–2017. doi: 10.1111/j.1523-1755.2004.00621.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Karumanchi SA, Maynard SE, Stillman IE, Epstein FH, Sukhatme VP. Preeclampsia: A renal perspective. Kidney Int. 2005;67:2101–2113. doi: 10.1111/j.1523-1755.2005.00316.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.