Abstract

The contribution of cis-regulatory mutations to human disease remains poorly understood. Whole genome sequencing can identify all non-coding variants, yet discrimination of causal regulatory mutations represents a formidable challenge. We used epigenomic annotation in hESC-derived embryonic pancreatic progenitor cells to guide the interpretation of whole genome sequences from patients with isolated pancreatic agenesis. This uncovered six different recessive mutations in a previously uncharacterized ~400bp sequence located 25kb downstream of PTF1A (pancreas-specific transcription factor 1a) in ten families with pancreatic agenesis. We show that this region acts as a developmental enhancer of PTF1A and that the mutations abolish enhancer activity. These mutations are the most common cause of isolated pancreatic agenesis. Integrating genome sequencing and epigenomic annotation in a disease-relevant cell type can uncover novel non-coding elements underlying human development and disease.

Most patients with syndromic pancreatic agenesis have heterozygous dominant mutations in GATA61,2. Extra-pancreatic features in these individuals include cardiac malformations, biliary tract defects, gut and other endocrine abnormalities. Four families have been reported with syndromic pancreatic agenesis with severe neurological features and cerebellar agenesis caused by recessive coding mutations in PTF1A3-5. Most cases of isolated, non-syndromic pancreatic agenesis remain unexplained with the only cause described being recessive coding mutations in PDX1 that have been reported in two families6,7. We previously noted that individuals with unexplained pancreatic agenesis were often born to consanguineous parents and rarely had extra-pancreatic features1. This suggested an autosomal recessive defect underlying isolated pancreatic agenesis.

To identify recessive mutations causing isolated pancreatic agenesis we used linkage and whole genome sequencing. Initially we performed homozygosity mapping in 6 affected and 1 unaffected subject from 3 unrelated consanguineous families (Supplementary Figure 1). This highlighted a single shared locus on chromosome 10 that included PTF1A, but mutations in coding and promoter sequences of PTF1A and the coding sequences of 24 other genes in the region were excluded by Sanger sequencing (Supplementary Figure 1 and Supplementary Table 1). We next performed whole genome sequencing on probands from the two families with multiple affected individuals. We first looked for homozygous coding mutations in the exomes of the two whole genome sequenced patients. Each patient had ~ 3.6 million variants, from which we filtered out any that were present in 81 control genomes or that were present at >1% frequency in the 1000 Genomes Project8. This left a total of 2,868 and 3,188 rare or novel homozygous SNVs and indels per patient. Of these, 8 and 19 were annotated as missense, nonsense, frameshift or essential splice site (Supplementary Table 2). However, these coding variants either did not co-segregate with the disease or were not considered plausible candidates for a role in pancreas development (Supplementary Table 2).

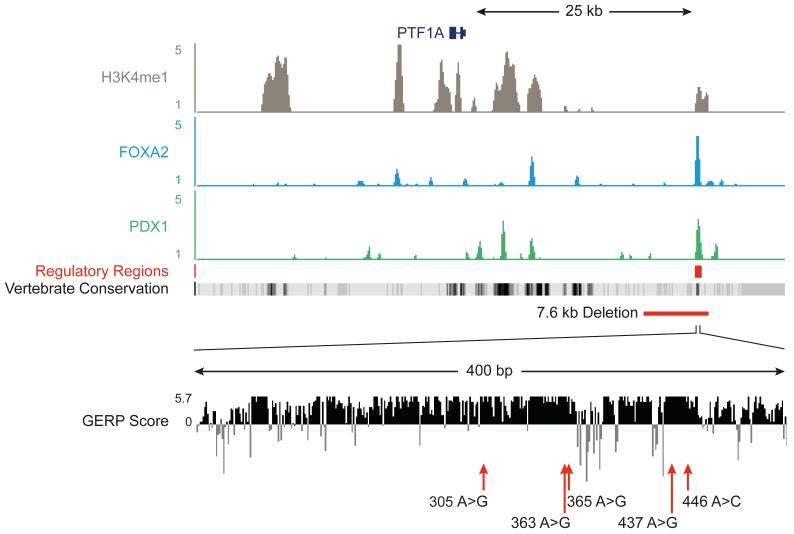

We next searched for non-coding disease-causing mutations among the remaining candidate homozygous variants. We reasoned that any causal variants should disrupt a non-coding genomic element that is active in cells that are relevant to this disease. As isolated pancreatic agenesis must be the result of a defect in early pancreas development, we determined if any of the rare or novel homozygous variants in these patients mapped to active regulatory regions from pancreatic endoderm cells derived from human embryonic stem cells (hESC) (Figure 1, Supplementary Figure 2 and Supplementary Figure 3). We thus defined 6,109 embryonic pancreatic progenitor putative transcriptional enhancers that were enriched in H3K4me1, a post-translational histone modification that is associated with enhancer regions, and were also bound by two or more pancreatic developmental transcription factors that are known to be essential for early pancreas development. Seven homozygous variants from each patient occurred in one of these annotated non-coding regions. However, only one of the 6,109 regulatory regions contained a variant in both sequenced individuals, and it was the same variant in the two unrelated patients (Supplementary Figure 2). This variant, chr10:23508437A>G, was located ~25kb downstream of PTF1A, in the region previously identified by homozygosity mapping (Figure 1). The novel variant occurred in a short (~400bp) evolutionary conserved region that showed enrichment for enhancer marks (H3K4me1 and H3K27Ac), and was bound by the transcription factors FOXA2 and PDX1 in hESC-derived pancreatic progenitor cells (Figure 1 and Supplementary Figure 4). Remarkably, this region lacked active chromatin features in 68 embryonic and adult cell types from the Epigenome RoadMap project and in 125 cell types from the ENCODE project (which includes an adult pancreatic exocrine cell line) indicating that it is specifically active in pancreatic embryonic progenitors (Supplementary Figure 5). A combination of whole genome sequencing and cis-regulatory annotations therefore identified a recessive mutation that mapped to a putative stage- and lineage-restricted transcriptional enhancer.

Figure 1. Epigenome annotation of variants from genome sequencing identifies a shared variant in a putative enhancer element.

Variant identified by whole genome sequencing, plus an additional five variants in patients with pancreatic agenesis map to a 25 Kb region downstream of PTF1A, which contains a single candidate pancreatic progenitor-specific enhancer within a highly conserved 400bp element. The top panel depicts ChIP-seq density plots for the enhancer mark H3K4me1, the second and third show occupancy for FOXA2 and PDX1. A broad panel of embryonic and adult human tissues do not show active chromatin marks in this region (Supplementary Figure 5). Vertebrate Conservation and mammalian conservation tracks (as measured by the GERP Score) tracks illustrate the high conservation of this element. The red line depicts the approximate location of a 7.6 kb deletion in this region, and red arrows indicate point mutations, using the final 3 digits from the hg19 coordinates as labels (referring to positions 23508305A>G, 23508363A>G, 23508365A>G, 23508437A>G and 23508446A>C on chromosome 10 respectively).

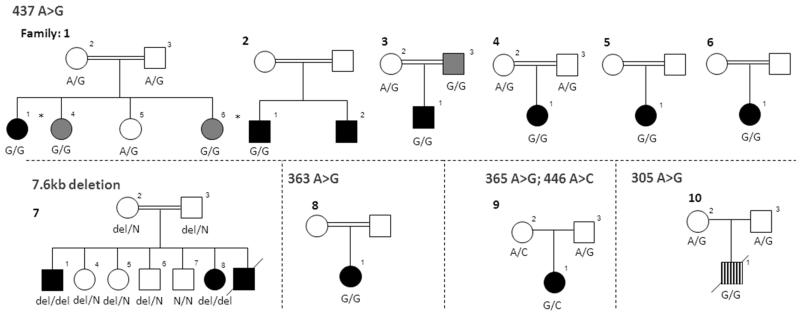

We sequenced this putative pancreatic developmental enhancer in 19 additional probands with pancreatic agenesis of unknown aetiology (9 with extra-pancreatic features and 10 isolated cases) and identified recessive mutations in 7 of the 10 patients with non-syndromic pancreatic agenesis. We also identified a homozygous mutation in one patient with pancreatic agenesis and intrahepatic cholestatic failure (Figure 2 and Supplementary Table 3). Of the 10 probands with mutations in this element, 6 had the same chr10:23508437A>G mutation as part of a shared extended haplotype (minimal shared haplotype of 1.2Mb; Supplementary Figure 6). Three of the remaining probands had different base substitution mutations: a homozygous chr10:23508363A>G mutation, a homozygous chr10:23508305A>G mutation and compound heterozygous chr10:23508365A>G/chr10:23508446A>C mutations (Figure 2). In the tenth family a 7.6kb deletion was identified by long range PCR, and sequence analysis showed that the deleted region (chr10:23502416-23510031) included the entire putative enhancer (Supplementary Figure 7).

Figure 2. Families with mutations in the PTF1A enhancer.

Black filled individuals have isolated pancreatic agenesis. Striped filled individual had pancreatic agenesis with intrahepatic cholestatic failure from which he died. Dark grey symbols are patients with exocrine insufficiency and young onset diabetes (age at diagnosis < 22 years). * Whole genome sequenced individual. DNA from the parents in family 2, 5, 6 and 8 was not available.

Testing of parents and siblings demonstrated co-segregation of the mutations with diabetes and exocrine insufficiency (Figure 2 and Supplementary Table 3). None of the mutations were present in 1092 individuals from the 1000 genomes project8 or in dbSNP137, and Sanger sequencing of 299 controls did not detect any of these variants. The deletion was not observed in the Database of Genomic Variants9. There is very little diversity in humans within this element; the only 3 variants reported in dbSNP137 or the 1000 genomes project are rare (<0.2% allele frequency). These results provide overwhelming genetic evidence that we have identified mutations causing non-syndromic pancreatic agenesis in a non-coding genomic region that is likely to be a transcriptional enhancer during pancreas development.

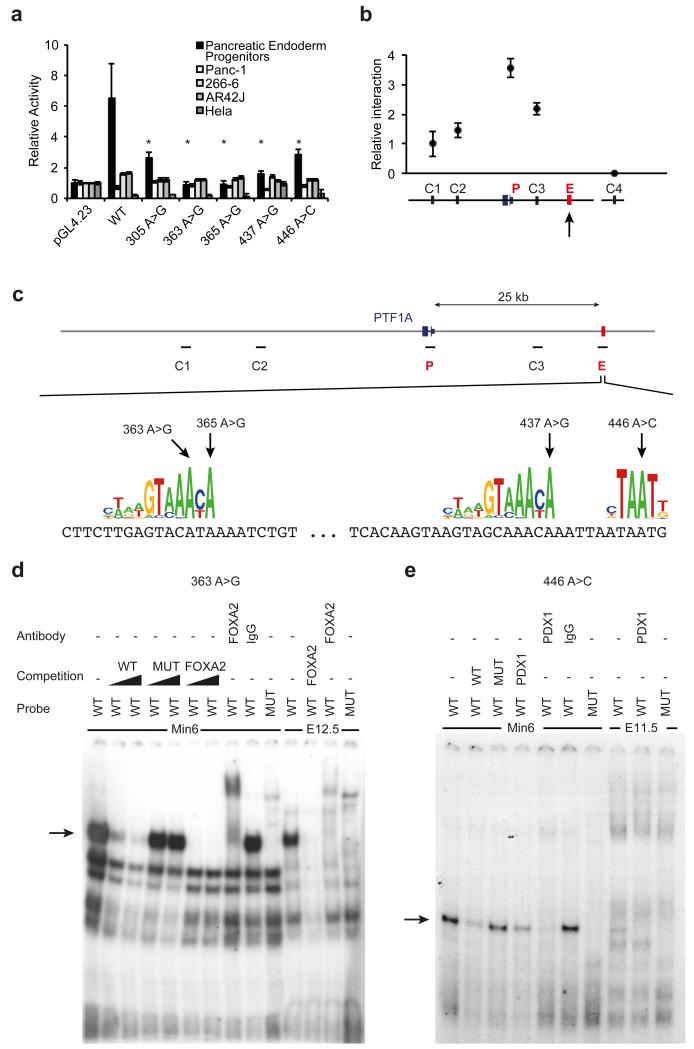

We next tested whether this previously uncharacterized non-coding element acts as a developmental enhancer of PTF1A. We linked the wild type sequence to a minimal promoter and performed luciferase assays in human pancreatic progenitor cells, which demonstrated lineage-specific enhancer activity (Figure 3A). The enhancer was not active in adult exocrine pancreatic cell lines, consistent with a stage-specific regulatory function (Figure 3A). To assess if this enhancer truly targets PTF1A, we performed chromatin conformation capture (3C) experiments. This demonstrated that the enhancer region establishes direct interactions with the PTF1A promoter in human pancreatic progenitor cells (Figure 3B and Figure 3C).

Figure 3. Pancreas agenesis mutations disrupt the function of a transcriptional enhancer that is specifically active in pancreatic progenitors.

(A) Reporter assays for the novel enhancer in hESC-derived pancreatic endoderm progenitors, several adult pancreatic exocrine transformed cells (Panc-1, 266-6, AR42J) and HeLa cells. Transcriptional enhancer activity was only observed in hESC-derived pancreatic progenitor cells, and it was disrupted by all 5 mutations. Asterisks indicate Student’s t test P<0.05 for comparisons of mutant vs. wild type enhancers in progenitors. (B) Chromosome conformation capture shows that the newly identified enhancer interacts directly with PTF1A promoter in hES cell-derived pancreatic progenitor cells. The viewpoint at PTF1A is signaled with an arrow, and the approximate regions that were tested for interaction with the viewpoint (C1, C2, C3, and P, for PTF1A promoter) are shown in (C). C4 represents a control region in an unrelated locus. (C) Pancreas agenesis mutations target critical residues in predicted binding sites for pancreatic regulators FOXA2 and PDX1. (D) Electrophoretic mobility shift assay showing high affinity, sequence-specific interaction of FOXA2 with a double stranded oligonucleotide containing the wild type (WT) sequence, but not the 363 A>G mutation (MUT). The retardation signal was suppressed by unlabelled consensus high-affinity binding site for FOXA2, and supershifted with antibodies recognizing FOXA2. Black triangles represent competition gradients of 30 and 100-fold cold probe excess. Binding activity is shown for MIN6 cells and dissected pancreatic buds from e12.5 mouse embryos. Probe refers to the radioactively labelled probed used in binding assays. (E) Electrophoretic mobility shift assay showing sequence-specific interaction of PDX1 with oligonucleotide containing the wild type (WT) sequence, but not the 446 A>C mutation (MUT). The retardation signal was suppressed by unlabelled consensus high-affinity binding site for PDX1, and supershifted with antibodies recognizing PDX1. Competition was performed with 100-fold cold probe excess. Binding activity is shown for MIN6 cells and pancreatic buds from e11.5 mouse embryos.

We next demonstrated that the five base-substitution mutations prevent enhancer activity by abolishing transcription factor binding. We noted that three of the mutations disrupt binding sites for FOXA2 and a fourth disrupts a binding site for PDX1 (Figure 3C). FOXA2 and PDX1 are essential transcription factors for pancreatic development6,10. Electrophoretic mobility shift assays confirmed that these four mutations abolished binding of FOXA2 or PDX1, as predicted, whereas the remaining point mutation disrupted the affinity of an uncharacterized sequence-specific DNA-binding protein present in mouse pancreatic progenitors (Figure 3D, Figure 3E and Supplementary Figure 8). Importantly, all five mutations disrupted the enhancer activity of this region in hESC-derived human pancreatic progenitors (Figure 3A). Collectively, these findings show that multiple mutations causing isolated pancreas agenesis disrupt the function of a previously unrecognized enhancer that targets PTF1A in human embryonic pancreatic progenitor cells.

The contribution of non-coding variants to human disease remains poorly understood. There are examples of mutations in distal regulatory elements causing monogenic disease11-14, but the number is small compared to coding mutations. Although whole genome sequencing technologies can potentially solve this problem, the discrimination of functional non-coding causal variants amongst millions of non-coding variants present in each individual remains a formidable challenge. The ENCODE project has recently uncovered functional elements throughout the non-coding genome, leading to expectations that these can be integrated with genome sequencing to discover causal non-coding mutations15. Our study now provides an example that validates this expectation, and shows that recessively inherited distal cis-regulatory mutations in a novel developmental enhancer are the most common cause of a rare Mendelian disease. The fact that the mutated regulatory element was exclusive to embryonic pancreatic progenitors among a broad panel of adult and embryonic tissues highlights the importance of analyzing disease-relevant genomic annotations. Our results support efforts to identify novel regulatory element mutations in monogenic disorders by integrating genome sequencing data with functional annotation from projects such as ENCODE15 and the Epigenome Roadmap16. These findings may also be relevant for future efforts to discover causal alleles in common non-Mendelian diseases, where many susceptibility variants appear to lie outside coding regions17.

In summary, we have demonstrated that mutation of a novel, distal, developmental enhancer of PTF1A is a common cause of isolated pancreatic agenesis in humans and demonstrate the potential of integrating genome sequencing with epigenomics to identify mutations in novel regulatory elements that cause disease.

Online Methods

Subjects

Pancreatic agenesis was defined as a) pancreatic beta-cell failure indicated by neonatal diabetes requiring insulin treatment and b) exocrine pancreatic insufficiency requiring enzyme replacement therapy, as previously described1. Isolated disease was defined as pancreatic agenesis with normal development and no neurological or other major clinical features. Clinical details of the patients are provided in Supplementary Table 3. Subjects with pancreatic agenesis were recruited by their clinicians for molecular genetic analysis in the Exeter Molecular Genetics Laboratory. The study was conducted in accordance with the Declaration of Helsinki and all subjects or their parents gave informed consent for genetic testing.

Whole genome sequencing

Whole genome sequencing of probands from families 1 and 2 was performed at Complete Genomics (Mountain View, CA, USA). The method has been described previously18. Complete Genomics software version 1.8.0.30 was used to align reads to the hg19 genome and call SNVs and indels. A total of 222 and 190Gb of bases were mapped with an average coverage of 73× and 63×. Ninety-five percent of hg19 bases had sufficient coverage to be fully called. 3,197,771 and 3,182,809 SNVs were called per sample with a Ti/Tv ratio of 2.15 and 2.14, and a novel (dbSNP131) SNP rate of 4.7 and 4.8%, respectively. 445,141 and 440,357 indels were called per sample with a dbSNP131 novelty rate of 22.4 and 22.8%.

For filtering SNVs and indels we used 69 publically available whole genomes provided by Complete Genomics18 and 12 additional whole genomes that had also been sequenced by Complete Genomics for a non-overlapping disease. We also filtered out variants present at >1% minor allele frequency in the 1000 genomes project8.

Differentiation of pancreatic endoderm from human embryonic stem cells

Human ESCs (H9 from WiCell, Maddison, WI, USA) were imported under the guidelines of the UK Stem Cell Bank Steering Committee (authorisation SCSC10-44). Cells were maintained and differentiated into artificial pancreatic progenitors using a previously fully described protocol19. These artificial pancreatic progenitors express a constellation of pancreatic endoderm markers including PDX1, HLXB9, NKX6.1, SOX9, HNF6, and PTF1A19. In brief, definitive endoderm (DE) was induced by growing hESCs in CDM-PVA + Activin-A (100ng/mL), BMP4 (10ng/mL), bFGF (20ng/mL) and LY (10 μM) (AFBLy). The CDM-PVA AFBLy cocktail was replenished daily, and daily media changes were made during the entire differentiation protocol. After the DE stage (days 1-3), cells were cultured in Advanced DMEM (Invitrogen) supplemented with SB-431542 (10 μM; Tocris), FGF10 (50 ng/ml; AutogenBioclear), all-trans retinoic acid (RA, 2 μM; Sigma) and Noggin (150 ng/ml; R&D Systems) for 3 days (days 4-6). For the next stage (days 7-10), the cells were cultured in Advanced DMEM supplemented with human FGF10 (50 ng/ml; AutogenBioclear), all-trans retinoic acid (RA, 2 uM; Sigma), KAAD-cyclopamine (0.25 μM; Toronto Research Chemicals) and Noggin (150 ng/ml; R&D Systems) for 3 days. For the last stage (days 10-12), the cells were cultured in human FGF10 (50 ng/ml; R&D Systems) for 3 days. For maturation of pancreatic progenitors (day 15 and day 18 artificial pMPCs), cells were grown in Advanced DMEM + 1% vol/vol B27 and DAPT (1 mM) for 3 days and for 3 additional days in Advanced DMEM + 1% vol/vol B27.

ChIP-Seq maps of pancreatic progenitor regulatory elements

Chromatin immunoprecipitations (ChIPs) for H3K4me1 (Abcam ab-8895; n=2), FOXA2 (Santa Cruz Biotechnology sc-6554, n=2), GATA6 (Santa Cruz Biotechnology sc-9055X; n=1), HNF1β (Santa Cruz Biotechnology sc-22840-X, n=1), ONECUT1 (Santa Cruz Biotechnology sc-13050, n=1) and PDX1 (BCBC AB2027; n=1) were performed essentially as described20, using ~10 million artificially derived pancreatic progenitors for each experiment. These transcription factors were chosen because they are known to be essential regulators of early pancreas development1,6,10,21-25, and because of the availability of antibodies that recognize human epitopes in chromatin immunoprecipitation experiments. Sequencing of ChIPs and input DNA was performed on an IlluminaHiSeq2000 platform. Transcription factor enrichment sites were detected with MACS v1.4.0beta26 and H3K4me1-enriched regions were defined with SICER v1.0327. We identified genomic regions that showed H3K4me1 enrichment in duplicate samples, and then defined H3K4me1-enriched regions bound by at least two transcription factors that were not located within 1 Kb from the transcriptional start sites of RefSeq genes. We then defined the limits of remaining regions as the outer limits of the transcription factor binding sites that cluster in each H3K4me1-enriched region. This resulted in 6,109 putative enhancer regions. ChIP-seq analysis of pancreatic progenitors, as well as global integrative and functional analysis of these regulatory maps is described elsewhere (SRS, CHC, IC, LV, JF, unpublished).

H3K27Ac ChIP

Chromatin immunoprecipitation (ChIP) for H3K27ac (Abcam ab-4729: n=2) was performed as previously described28, using ~10 million artificially derived pancreatic progenitors. Fold enrichment was calculated using NANOG TSS as negative control. The oligonucleotides used in this analysis are listed in Supplementary Table 4.

Homozygosity Mapping

Genome wide single nucleotide polymorphism genotyping was performed using the Affymetrix Mapping 10K Xba SNP genotyping chip by Medical Solutions, Nottingham (formerly GeneService; Nottingham, UK) with an average call rate of >96%. Runs of homozygous SNP calls that exceeded 3cM from at least 20 consecutive probes were identified in the 6 affected probands and one unaffected sibling from 3 families. Common genomic regions of homozygosity were sought across the affected patients, excluding any shared with the unaffected sibling (Supplementary Figure 1). The coding exons of all 25 RefSeq genes contained within the single shared region of homozygosity on chromosome 10 and the promoter and upstream conserved region of PTF1A were sequenced using capillary sequencing on the Applied BioSystems 3730xl DNA Analyzer (Life Technologies). Primers were designed to cover −50 to plus 10 base pairs of each exon in overlapping fragments if required (Primer designs are available on request). There was no evidence to support any causative variants within these genes

Conservation analysis

Eighty percent of bases between positions chr10:23508149 to chr10:23508510 were classified as being part of a vertebrate conserved element by PhastCons29 (LOD>17). Multiz alignment from the UCSC genome browser30 shows that there is conservation of the entire element down to Chicken, and that over half the element is conserved down to X. Tropicalis. All mutated bases are highly conserved with all having GERP31 scores of 5.65.

Sanger sequencing of the PTF1A element

We amplified the conserved ~400bp element using primers in Supplementary Table 4. PCR products were sequenced on an ABI3730 capillary machine (Applied Biosystems, Warrington, UK) and analyzed using Mutation Surveyor v3.98 (SoftGenetics, Pennsylvania, USA).

Shared haplotype analysis and cryptic relatedness testing

We first tested for a shared haplotype from the individuals in whom whole genome sequencing was undertaken. We only used SNPs where both alleles in both samples were fully called. There were 1,234 consecutive SNP calls between chr10:21314935 to 24693292 that were identical between the two samples, except for 4 discrepancies (which is within the expected genotyping error rate). For shared haplotype analyses of additional families with the 437A>G mutation we also included 3 patients genotyped on the Affymetrix Genome-wide Human SNP 5.0 or 6.0, and extracted genotypes from these SNPs for the two individuals who underwent genome sequencing. Sample 6-1 was not included in this analysis because of a lack of dense genotyping data. Any SNP that was not called for at least one sample was excluded from the analysis. One discrepancy per 50 SNPs was tolerated to allow for genotyping error. Supplementary Figure 6 presents a graphical representation of the shared haplotype.

To test whether the shared haplotype could be explained by cryptic relatedness between families we used KING32 to estimate relatedness between probands from each of the families with the 437A>G mutation. We only used SNPs that were present on both the Affymetrix Genome-wide Human SNP 5.0 or 6.0. All pairs of probands had a kinship coefficient < 0.022 consistent with them being “unrelated”32.

Deletion analysis

The genomic region chr10:23501386-23512912 was amplified in patients 7-4 and 7-8 by long-range PCR using the SequalPrep Long PCR kit (Life Technologies). PCR products were sheared by sonication (Diagenode Bioruptor), and fragments in the size range of 200–300 bp were isolated for library preparation with NextFlex adapters with a 6 base index sequence tag. Individual libraries were enriched by 6 cycles of PCR amplification and were then pooled in equimolar quantities for 100 bp paired-end sequencing on an Illumina HiSeq2000 sequencer. We used BWA (v0.6.2)33 to align sequence reads to the hg19 reference genome and then visualized the breakpoints using the Integrative Genomics Viewer34 which demonstrated that the deletion breakpoints occurred at chr10:23502416 and chr10:23510031 (Supplementary Figure 7). The deletion mutation was investigated in all available members of family 7 using a junction fragment PCR assay (primer sequences available on request).

Sanger sequencing of the PTF1A enhancer in control samples

We sequenced the putative PTF1A enhancer element in 150 healthy controls of European descent from the Exeter Family Study of Childhood health35 and 149 individuals from Turkey using Sanger sequencing (Supplementary Table 4). No variants were identified.

Transcription factor binding motif analysis

Motif discovery over the point mutation sites comparing wild type and mutation-containing sequences was performed using HOMER36.

Electrophoretic mobility-shift assays

Mouse pancreatic buds were dissected from E11.5 and E12.5 C57Bl/6J mouse embryos as described37. Nuclear extracts were purified as described38. Binding of nuclear extracts from embryonic pancreas and MIN6 β-cells to 32P-labeled oligonucleotides that contained either wild type or the mutation-containing sequence was performed as described previously39. The oligonucleotide sequences used are listed in Supplementary Table 4. Assay specificity was assessed by preincubation of the nuclear lysates with 30- and 100-fold excess of unlabelled wild type, mutant or consensus double-stranded oligonucleotides. Supershifts were performed using 2 μl of goat polyclonal serum anti-FOXA2 (sc-6554), anti-PDX1 (sc-14662) or control IgG (sc-2028; Santa Cruz Biotechnologies).

Chromosome conformation capture assay

Approximately 107 artificial pancreatic progenitors were fixed for 20 minutes at 4°C in 4% paraformaldehyde, washed three times in PBS and lysed (10 mM Tris-HCl pH 8, 10 mM NaCl, 0.3% IGEPAL CA-630 (Sigma-Aldrich, Cat. No. I8896), 1× protease inhibitor cocktail (Complete, Roche). Nuclei were digested with HindIII endonuclease (New England Biolabs). DNA was then ligated with T4 DNA ligase (Promega). Locus specific primers were designed with Primer3 v. 0.4.040 as described previously41. Relative enrichment of each ligation product was measured by real time quantitative PCR. The primer specific to PTF1A enhancer (3C-E) was considered fixed and interaction with PTF1A promoter was tested using primers close either to the promoter (3C-P) or to adjacent control regions (3C-Crt1, 3C-Crt2 and 3C-Crt3). A primer specific to the XBP1 promoter was used as an unrelated locus control (3C-XBP1). All primers are shown in Supplementary Table 4. Amplimers were compared with parallel amplifications of serial dilutions of control bacterial artificial chromosomes (BAC) that encompass the genomic region of interest (RP11-938O7) and the XBP1 control locus (RP11-594I15), which were processed identically to the pancreatic progenitor chromatin.

PTF1A enhancer cloning and luciferase reporter assays

PTF1A enhancer wild type and mutant sequences were PCR amplified from genomic DNA of a control individual and patients carrying the mutations, respectively, with Phusion High-Fidelity DNA Polymerase (New England Biolabs) (see Supplementary Table 4 for primer sequences) and cloned into pENTR/D-TOPO (Invitrogen). The enhancers were then shuttled into a pGL4.23[luc2/minP] Vector backbone (Promega) previously adapted for Gateway cloning pGL4.23-GW (Pasquali L, unpublished), using Gateway LR Clonase II Enzyme Mix (Invitrogen). Correct cloning was assessed by Sanger sequencing and restriction enzyme digestion.

DNA was prepared with PureYieldTM Plasmid Maxiprep System (Promega). At day 10 of differentiation the artificial pancreatic progenitors were transfected in 24-well plates with 400ng of pGL4.23-GW-PTF1A_Enhancer vectors and 4ng Renilla normalizer control using Lipofectamine 2000 (Invitrogen) Opti-MEM (Gibco) according to manufacturer’s instructions. Panc-1 (human pancreatic ductal), 266-6 (mouse pancreatic acinar), AR42J (rat pancreatic acinar) and HeLa cells were transfected in 96-well plates using Lipofectamine 2000 and Opti-MEM (Gibco) at a density of 4×104 of cells per well, according to manufacturer’s instructions for this format. 48 hours after transfection, luciferase activity was measured with Dual-Luciferase Reporter Assay System (Promega). Firefly luciferase activity was normalized to Renilla luciferase activity and then to the pGL4.23[luc2/minP] Vector backbone. Statistical significance was determined by comparing firefly/renilla luciferase values of each mutant to the wild type construct using a two-sided T-test. All DNA preparations were transfected in triplicate.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgements

SE and ATH are supported by Wellcome Trust Senior Investigator awards. MNW is supported by the Wellcome Trust as part of the WT Biomedical Informatics Hub funding. EDF is funded by the BOLD grant (European Community’s Seventh Framework Programme (FP7/2007-2013) under grant agreement number FP7-PEOPLE-ITN-2008 (Marie Curie Initial Training Networks, Biology of Liver and Pancreatic Development and Disease). The authors thank Michael Day, Annet Damhuis and Javier Garcia-Hurtado, for technical assistance, and Rick Tearle (Complete Genomics), Juan Tena and José Luís Skarmeta (Centro Andaluz de Biologia del Desarrollo) for advice. This work was supported by NIHR Exeter Clinical Research Facility through funding for SE and ATH and general infrastructure, and Ministerio de Economía y Competitividad (SAF2011-27086, PLE2009-0162 to JF). The views expressed in this paper are those of the authors and not necessarily those of the NHS, the NIHR or the Department of Health.

Footnotes

Competing Financial Interests: The authors declare no competing financial interests.

References

- 1.Lango Allen H, et al. GATA6 haploinsufficiency causes pancreatic agenesis in humans. Nature genetics. 2011;44:20–2. doi: 10.1038/ng.1035. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.De Franco E, et al. GATA6 Mutations Cause a Broad Phenotypic Spectrum of Diabetes From Pancreatic Agenesis to Adult-Onset Diabetes Without Exocrine Insufficiency. Diabetes. 2013;62:993–7. doi: 10.2337/db12-0885. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Sellick GS, et al. Mutations in PTF1A cause pancreatic and cerebellar agenesis. Nature genetics. 2004;36:1301–5. doi: 10.1038/ng1475. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Tutak E, et al. A Turkish newborn infant with cerebellar agenesis/neonatal diabetes mellitus and PTF1A mutation. Genetic counseling. 2009;20:147–52. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Al-Shammari M, Al-Husain M, Al-Kharfy T, Alkuraya FS. A novel PTF1A mutation in a patient with severe pancreatic and cerebellar involvement. Clinical genetics. 2011;80:196–8. doi: 10.1111/j.1399-0004.2010.01613.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Stoffers DA, Zinkin NT, Stanojevic V, Clarke WL, Habener JF. Pancreatic agenesis attributable to a single nucleotide deletion in the human IPF1 gene coding sequence. Nature genetics. 1997;15:106–10. doi: 10.1038/ng0197-106. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Schwitzgebel VM, et al. Agenesis of human pancreas due to decreased half-life of insulin promoter factor 1. The Journal of clinical endocrinology and metabolism. 2003;88:4398–406. doi: 10.1210/jc.2003-030046. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Abecasis GR, et al. An integrated map of genetic variation from 1,092 human genomes. Nature. 2012;491:56–65. doi: 10.1038/nature11632. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Iafrate AJ, et al. Detection of large-scale variation in the human genome. Nat Genet. 2004;36:949–51. doi: 10.1038/ng1416. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Gao N, et al. Dynamic regulation of Pdx1 enhancers by Foxa1 and Foxa2 is essential for pancreas development. Genes and development. 2008;22:3435–48. doi: 10.1101/gad.1752608. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Cooper DN, et al. Genes, mutations, and human inherited disease at the dawn of the age of personalized genomics. Human mutation. 2010;31:631–55. doi: 10.1002/humu.21260. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Smemo S, et al. Regulatory variation in a TBX5 enhancer leads to isolated congenital heart disease. Human molecular genetics. 2012;21:3255–63. doi: 10.1093/hmg/dds165. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Spielmann M, et al. Homeotic arm-to-leg transformation associated with genomic rearrangements at the PITX1 locus. American journal of human genetics. 2012;91:629–35. doi: 10.1016/j.ajhg.2012.08.014. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Sankaran VG, et al. A functional element necessary for fetal hemoglobin silencing. The New England journal of medicine. 2011;365:807–14. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa1103070. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.ENCODE Project Consortium et al. An integrated encyclopedia of DNA elements in the human genome. Nature. 2012;489:57–74. doi: 10.1038/nature11247. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Bernstein BE, et al. The NIH Roadmap Epigenomics Mapping Consortium. Nature biotechnology. 2010;28:1045–8. doi: 10.1038/nbt1010-1045. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Maurano MT, et al. Systematic localization of common disease-associated variation in regulatory DNA. Science. 2012;337:1190–5. doi: 10.1126/science.1222794. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Drmanac R, et al. Human genome sequencing using unchained base reads on self-assembling DNA nanoarrays. Science. 2010;327:78–81. doi: 10.1126/science.1181498. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Cho CH, et al. Inhibition of activin/nodal signalling is necessary for pancreatic differentiation of human pluripotent stem cells. Diabetologia. 2012;55:3284–95. doi: 10.1007/s00125-012-2687-x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Moran I, et al. Human beta cell transcriptome analysis uncovers lncRNAs that are tissue-specific, dynamically regulated, and abnormally expressed in type 2 diabetes. Cell metabolism. 2012;16:435–48. doi: 10.1016/j.cmet.2012.08.010. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Carrasco M, Delgado I, Soria B, Martin F, Rojas A. GATA4 and GATA6 control mouse pancreas organogenesis. The Journal of clinical investigation. 2012;122:3504–15. doi: 10.1172/JCI63240. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Xuan S, et al. Pancreas-specific deletion of mouse Gata4 and Gata6 causes pancreatic agenesis. The Journal of clinical investigation. 2012;122:3516–28. doi: 10.1172/JCI63352. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Haumaitre C, et al. Lack of TCF2/vHNF1 in mice leads to pancreas agenesis. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America. 2005;102:1490–5. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0405776102. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Jacquemin P, et al. Transcription factor hepatocyte nuclear factor 6 regulates pancreatic endocrine cell differentiation and controls expression of the proendocrine gene ngn3. Molecular and cellular biology. 2000;20:4445–54. doi: 10.1128/mcb.20.12.4445-4454.2000. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Offield MF, et al. PDX-1 is required for pancreatic outgrowth and differentiation of the rostral duodenum. Development. 1996;122:983–95. doi: 10.1242/dev.122.3.983. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Zhang Y, et al. Model-based analysis of ChIP-Seq (MACS) Genome biology. 2008;9:R137. doi: 10.1186/gb-2008-9-9-r137. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Zang C, et al. A clustering approach for identification of enriched domains from histone modification ChIP-Seq data. Bioinformatics. 2009;25:1952–8. doi: 10.1093/bioinformatics/btp340. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.van Arensbergen J, et al. Derepression of Polycomb targets during pancreatic organogenesis allows insulin-producing beta-cells to adopt a neural gene activity program. Genome research. 2010;20:722–32. doi: 10.1101/gr.101709.109. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Siepel A, et al. Evolutionarily conserved elements in vertebrate, insect, worm, and yeast genomes. Genome research. 2005;15:1034–50. doi: 10.1101/gr.3715005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Meyer LR, et al. The UCSC Genome Browser database: extensions and updates 2013. Nucleic acids research. 2013;41:D64–9. doi: 10.1093/nar/gks1048. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Davydov EV, et al. Identifying a high fraction of the human genome to be under selective constraint using GERP++ PLoS computational biology. 2010;6:e1001025. doi: 10.1371/journal.pcbi.1001025. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Manichaikul A, et al. Robust relationship inference in genome-wide association studies. Bioinformatics. 2010;26:2867–73. doi: 10.1093/bioinformatics/btq559. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Li H, Durbin R. Fast and accurate short read alignment with Burrows-Wheeler transform. Bioinformatics. 2009;25:1754–60. doi: 10.1093/bioinformatics/btp324. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Robinson JT, et al. Integrative genomics viewer. Nature biotechnology. 2011;29:24–6. doi: 10.1038/nbt.1754. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Knight B, Shields BM, Hattersley AT. The Exeter Family Study of Childhood Health (EFSOCH): study protocol and methodology. Paediatric And Perinatal Epidemiology. 2006;20:172–179. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-3016.2006.00701.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Heinz S, et al. Simple combinations of lineage-determining transcription factors prime cis-regulatory elements required for macrophage and B cell identities. Molecular cell. 2010;38:576–89. doi: 10.1016/j.molcel.2010.05.004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.van Arensbergen J, et al. Ring1b bookmarks genes in pancreatic embryonic progenitors for repression in adult beta cells. Genes and development. 2013;27:52–63. doi: 10.1101/gad.206094.112. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Maestro MA, et al. Hnf6 and Tcf2 (MODY5) are linked in a gene network operating in a precursor cell domain of the embryonic pancreas. Human molecular genetics. 2003;12:3307–14. doi: 10.1093/hmg/ddg355. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Boj SF, Parrizas M, Maestro MA, Ferrer J. A transcription factor regulatory circuit in differentiated pancreatic cells. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America. 2001;98:14481–6. doi: 10.1073/pnas.241349398. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Rozen S, Skaletsky H. Primer3 on the WWW for general users and for biologist programmers. Methods in molecular biology. 2000;132:365–86. doi: 10.1385/1-59259-192-2:365. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Tena JJ, et al. An evolutionarily conserved three-dimensional structure in the vertebrate Irx clusters facilitates enhancer sharing and coregulation. Nature communications. 2011;2:310. doi: 10.1038/ncomms1301. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.