Abstract

Green and Ewing propose corrections to our methodology, which we incorporate and extend here. The improved methodology supports our initial conclusion of extensive lineage-specific constraint concentrated in ENCODE elements. We clarify that our estimate is dependent on the constrained and neutral references used, which can further increase the number of nucleotides involved, since a particularly stringent definition was initially used.

In our initial report (1), we found reduced genetic diversity at noncoding genomic regions that have not been conserved across mammals but are biochemically active, suggesting that some fraction of these regions has experienced lineage-specific purifying selection, and proposed a method for estimating the proportion under human constraint (PUC). Green and Ewing suggest that our PUC estimate is inflated by several technical artifacts, and that a reduction in SNP density cannot be reliably distinguished from a reduction in mutation rate. In this response, we incorporate and build upon their improved method by including additional quality filters, and we repeat our analysis, confirming the validity of each of their proposed corrections, but demonstrating continued support for our original conclusions. We address each of the corrections raised below.

First, Green and Ewing point out that masking CpG nucleotides formed by both reference and alternate alleles can lead to lower density measurements in GC-rich features, and that including positions where the reference genome contains the derived allele leads to higher density measurements and higher derived allele frequency (DAF) measurements in less-constrained regions. We confirm that incorporating both corrections modestly decreases our density-based total estimate of recent constraint.

Second, they show that density-based estimates can be biased by variable mutation rate due to nucleotide composition and regional effects. However, we note that our analysis comparing heterozygosity levels at bound and unbound regulatory motifs would not be affected by such mutation rate differences, because the nucleotide composition is the same between bound and unbound instances. Moreover, the remaining results in our original paper are supported by DAF, which is not sensitive to mutation rate.

Third, they point out that the allele frequency estimates of the 1000 Genomes Pilot low-coverage data are biased by sequencing depth, causing rarer alleles to be more efficiently called in higher-coverage regions, and thus lowering the mean DAF of higher-coverage regions. Since higher GC content is associated with both higher sequencing depth and with ENCODE-defined active regions, this could potentially lead to artificially lower DAF for ENCODE regions. Green and Ewing proposed a procedure for correcting this effect by calculating relative constraint within bins of equal sequencing depth, which led to a reduced, albeit still substantial, estimate of human constraint.

As the rare part of the Pilot allele frequency spectrum (DAF < 2%) ought to show the strongest signal of selection, they also specifically focused on rare genotypes. However, rare variants are also the most prone to genotype errors. To address these potential genotyping errors, we have extended Green and Ewing’s methodology by including a quality filter that requires at least 50 of the YRI individuals to have genotype calls from all three sequencing centers and exclude the top and bottom 5% of SNPs by total read depth to avoid technical artifacts. Lastly, we use mammalian-conserved and unconserved regions as the reference points for DAF within each coverage bin, which are much more abundant annotations than nondegenerate conserved protein-coding nucleotides, to reduce sampling error.

We refer to the resulting value as coverage-corrected relative constraint (ccRC) to emphasize that it can take on both positive and negative values, and that it represents an aggregate measure of overall constraint, rather than a partitioning between constrained and non-constrained bases. The ccRC values of a test feature and two control features can then be used to produce a PUC value as described previously.

The resulting ccRC values (Table 1) confirm our original observation of extensive lineage-specific purifying selection concentrated at ENCODE elements, especially at regulatory motifs bound by their cognate proteins (2, 3) and at enhancers defined by histone modification patterns (4, 5). Moreover, the signal of selection is apparent both in the mean DAF and in the fraction of alleles with DAF less than 2%, the additional criterion proposed by Green and Ewing, consistent with an increased accuracy at these rare sites.

Table 1.

Coverage-corrected relative constraint (ccRC) based on derived allele frequencies at annotated genomic features. Values are in arbitrary units scaled between noncoding unconserved (zero) and noncoding conserved (unity).

| Feature | Mb covered by feature |

ccRC using mean DAF |

ccRC using DAF < 2% |

|||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Mammalian- conserved |

Total mammalian-conserved | 108.3 | 1.07 | 1.26 | ||

| Nondegenerate protein-coding | 12.4 | 2.21 | 4.10 | |||

| Noncoding (TSS- distal, nonexonic) genome |

Total noncoding conserved | 73.0 | 1.00 | 1.00 | ||

| Mammalian conserved noncoding ENCODE |

Total | 56.4 | 1.08 | 1.08 | ||

| Bound motif | 0.6 | 1.46 | 1.36 | |||

| Dnase | 27.3 | 1.25 | 1.19 | |||

| Enhancer | 19.6 | 1.33 | 1.34 | |||

| Long RNA | 45.3 | 1.09 | 1.10 | |||

| Non-ENCODE | Total | 16.6 | 0.76 | 0.74 | ||

| Mammalian- unconserved |

Total mammalian-unconserved | 1831.0 | 0.03 | 0.03 | ||

| Noncoding (TSS- distal, nonexonic) genome |

Total noncoding unconserved | 1620.6 | 0.00 | 0.00 | ||

| Mammalian unconserved noncoding ENCODE |

Total | 1122.9 | 0.03 | 0.04 | ||

| Bound motif | 3.0 | 0.77 | 0.14 | |||

| Dnase | 344.0 | 0.00 | −0.01 | |||

| Enhancer | 314.0 | 0.12 | 0.13 | |||

| Long RNA | 955.6 | 0.06 | 0.08 | |||

| Non-ENCODE | Total | 497.7 | −0.06 | −0.09 | ||

| Fourfold degenerate protein-coding | 1.0 | −0.37 | −1.37 | |||

Lastly, we stress that our original PUC estimates had made the assumption that constrained nucleotides have the same average selection coefficient as conserved coding positions, specifically in non-degenerate sites, which are the most constrained class of nucleotides we observe. These PUC estimates can change and become considerably higher if instead we model the constraint using different reference annotations.

For example, estimating PUC using the new ccRC values and our original report's constrained and unconstrained references leads to an updated estimate of 51 Mb of the mappable non-mammalian-conserved genome being under human constraint (1.6% of the entire genome). When the constrained reference is the average of all mammalian-conserved regions, including both coding and non-coding elements, this estimate rises to 157 Mb (5.1% of the entire genome). We can also make a PUC estimate that quantifies the difference in constraint between ENCODE and non-ENCODE regions in the unconserved noncoding genome.

Using this approach, we can directly estimate the fraction of ENCODE nucleotides that are likely to be constrained at the level of mammalian-conserved noncoding elements, specifically testing noncoding ENCODE elements outside mammalian-conserved regions. This results in 129 Mb (11.5% of the unconserved noncoding ENCODE nucleotides) having the same level of constraint as mammalian-conserved noncoding nucleotides (our constrained reference), and the remaining 994 Mb (88.5%) having the same level of constraint as non-conserved noncoding regions outside ENCODE elements (the unconstrained reference).

It important to note that each of these estimates is a simplification of a much more complex picture, as each nucleotide has its own selection coefficient which we do not have power to estimate directly, and human constraint is due to a mixture of multiple classes of elements (not only two) which we do not seek to distinguish in our analysis.

In summary, we agree with the proposed corrections from Green and Ewing, which will also be important in interpreting related population genomics work estimating constraint at regulatory elements (6–8). However, these corrections should be coupled with the additional quality filters applied here when looking at low-coverage data. Our ccRC estimates, which incorporate both corrections, support our original conclusion of extensive lineage-specific constraint on regulatory elements and continue to be consistent with previous estimates by other groups (9, 10).

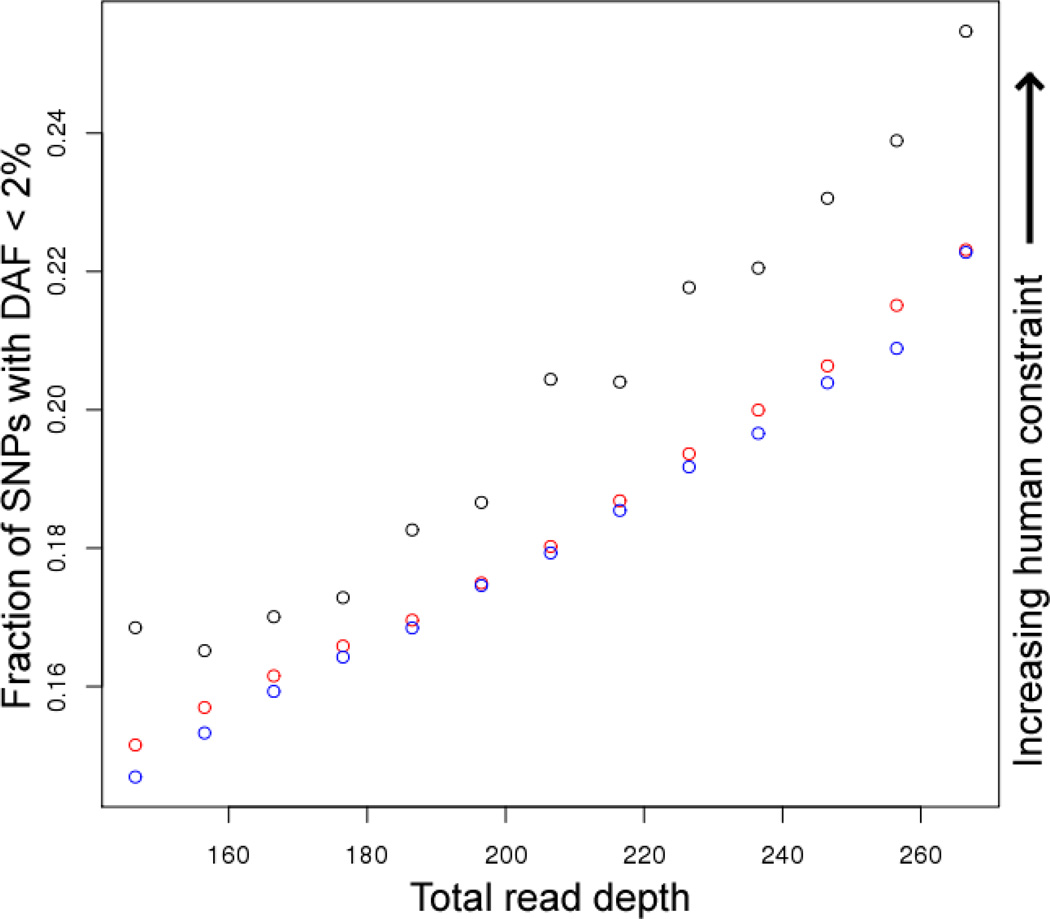

Figure 1.

Fraction of SNPs with DAF < 2% in annotated features, binned by depth of coverage. Blue = unconserved noncoding non-ENCODE, red = unconserved noncoding ENCODE, black = conserved noncoding.

Acknowledgments

We thank P. Green and B. Ewing for numerous suggestions, for sharing unpublished datasets, and for their helpful correspondence.

Footnotes

Suggested changes and format may be viewed with the track changes function of Microsoft Word

References and Notes

- 1.Ward LD, Kellis M. Evidence of Abundant Purifying Selection in Humans for Recently Acquired Regulatory Functions. Science. 2012;337:1675–1678. doi: 10.1126/science.1225057. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Cheng C, et al. Understanding transcriptional regulation by integrative analysis of transcription factor binding data. Genome Res. 2012;22:1658–1667. doi: 10.1101/gr.136838.111. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Gerstein MB, et al. Architecture of the human regulatory network derived from ENCODE data. Nature. 2012;489:91–100. doi: 10.1038/nature11245. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Ernst J, et al. Mapping and analysis of chromatin state dynamics in nine human cell types. Nature. 2011;473:43–49. doi: 10.1038/nature09906. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Hoffman MM, et al. Integrative annotation of chromatin elements from ENCODE data. Nucleic Acids Res. 2013;41:827–841. doi: 10.1093/nar/gks1284. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Spivakov M, et al. Analysis of variation at transcription factor binding sites in Drosophila and humans. Genome Biol. 2012;13:R49. doi: 10.1186/gb-2012-13-9-r49. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Mu XJ, Lu ZJ, Kong Y, Lam HYK, Gerstein MB. Analysis of genomic variation in non-coding elements using population-scale sequencing data from the 1000 Genomes Project. Nucleic Acids Res. 2011;39:7058–7076. doi: 10.1093/nar/gkr342. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Gronau I, Arbiza L, Mohammed J, Siepel A. Inference of Natural Selection from Interspersed Genomic Elements Based on Polymorphism and Divergence. Mol. Biol. Evol. 2013 doi: 10.1093/molbev/mst019. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Asthana S, et al. Widely distributed noncoding purifying selection in the human genome. PNAS. 2007;104:12410–12415. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0705140104. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Meader S, Ponting CP, Lunter G. Massive turnover of functional sequence in human and other mammalian genomes. Genome Res. 2010;20:1335–1343. doi: 10.1101/gr.108795.110. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]