Abstract

Chronic opioid-consumption increases postoperative pain. Epigenetic changes related to chronic opioid use and surgical incision may be partially responsible for this enhancement. The CXCL1/CXCR2 signaling pathway implicated in several pain models and is known to be epigenetically regulated via histone acetylation. The current study was designed to investigate the role of CXCL1/CXCR2 signaling in opioid-enhanced incisional sensitization, and to elucidate the possible epigenetic mechanism underlying CXCL1/CXCR2 pathway-mediated regulation of nociceptive sensitization in mice. Chronic morphine treatment generated mechanical and thermal nociceptive sensitization and also significantly exacerbated incision-induced mechanical allodynia. Peripheral but not central mRNA levels of CXCL1 and CXCR2 were increased after incision. The source of peripheral CXCL1 appeared to be wound area neutrophils. Histone H3 subunit acetylated at the lysine 9 position (AcH3K9) was increased in infiltrating dermal neutrophils after incision and was further increased in mice with chronic morphine treatment. The association of AcH3K9 with the promoter region of CXCL1 was enhanced in mice after chronic morphine treatment. The increase in CXCL1 near wounds caused by chronic morphine pretreatment was mimicked by pharmacologic inhibition of histone deacetylation. Finally, local injection of CXCL1 induced mechanical sensitivity in naive mice, whereas blocking CXCR2 reversed mechanical hypersensitivity after hindpaw incision.

Keywords: Chemokine, opioid-induced hyperalgesia, skin incision, histone acetylation, postoperative pain

Introduction

Opioids are now widely used for the treatment of acute and chronic pain. However, the long term use of opioids can generate both psychological and physiological complications. Opioid-induced hyperalgesia (OIH) is one such problem. OIH is an enhanced pain sensitivity resulting from prolonged medical or illicit exposure to opioids1. It has been clinically recognized that chronically opioid-consuming patients experience increased postoperative pain compared with opioid-naive patients, and require higher doses of postoperative pain relievers possibly due to OIH 7, 12, 34. For example, Chapman et al. showed that chronic pain patients receiving prolonged opioid therapy showed more intense acute postoperative pain compared with chronic pain patients without histories of opioid pharmacotherapy 7. Moreover, several groups have studied the interaction of chronic opioid administration and surgical incision in rodent models generally concluding that perioperative opioid exposure worsens thermal, punctate and pressure-related nociceptive sensitization 3, 21, 22, 37. Our group reported that chronic morphine treatment prior to incision leads to excess production of wound area cytokines thus providing one potential mechanism whereby preoperative opioid exposure worsens postoperative pain 22.

A novel family of cytokines that has been linked to the induction and maintenance of pain sensitization are the chemotactic cytokines (chemokines). Chemokines mediate the infiltration of leukocytes to sites of injury by activating specific G protein-coupled receptors on the leukocyte cell surface, and can also directly stimulate nociceptive sensory neurons 29. One chemokine, keratinocyte-derived chemokine (KC, CXCL1) and its cognate CXC chemokine receptor 2 (CXCR2) have been recently implicated in the regulation of nociceptive sensitivity in several pain models 4, 26, 39, 43. For example, Zhang et al. reported that astrocyte-produced CXCL1 acted on CXCR2-expressing dorsal horn neurons to elicit central sensitization in a mouse nerve ligation model 43. Both peripheral and central injection of CXLC1 were observed to cause mechanical hyperalgesia in naive rodents 14, 26, 43, whereas, administration of CXCR2 antagonists were shown to attenuate inflammatory, neuropathic and incisional nociceptive sensitization 4, 19, 27, 39, 43. Moreover, both CXCL1 and CXCR2 have been demonstrated to be epigenetically regulated via histone acetylation 19, 39. Epigenetic regulation refers to modifications of DNA or surrounding chromatin without alteration of DNA sequence. The modification of histone proteins, DNA methylation and microRNA regulation are well-known mechanisms of epigenetic regulation that influence gene expression. Since our previous studies demonstrated that epigenetic mechanisms play a crucial role in opioid-induced hyperalgesia 23, and chronic opioid exposure leads to the enhanced local expression of chemokines after incision 22, 37, we hypothesized that the epigenetic regulation of CXCL1 and its cognate CXCR2 receptor near incisional wounds may lead to the enhanced activity of this pain-related signaling pathway. The current study, therefore, was designed to investigate the role of CXCL1/CXCR2 signaling in opioid-enhanced incisional sensitization. Additional studies to elucidate the possible epigenetic mechanism underlying CXCL1/CXCR2 pathway-mediated regulation of nociceptive sensitization in mice were carried out.

Materials and methods

Animal use

All experimental protocols were reviewed and approved by Veterans Affairs Palo Alto Healthcare System Institutional Animal Care and Use Committee prior to beginning the work. All protocols conform to the guidelines for the study of pain in awake animals as established by the International Association for the Study of Pain. Male mice 8–9 weeks old of the C57BL/6J strain were obtained from Jackson Laboratory (Bar Harbor, ME). Mice were housed four per cage and maintained on a 12-h light/dark cycle and an ambient temperature of 22 ± 1 °C, with food and water available ad libitum.

Hindpaw incision

The hindpaw incision model in mice was performed in our laboratory as described in previous studies 9, 24, 38. Briefly, mice were anesthetized using isoflurane 2–3% delivered through a nose cone. After sterile preparation with alcohol, a 5 mm longitudinal incision was made with a number 11 scalpel on the plantar surface of the right hindpaw. The incision was sufficiently deep to divide deep tissue including the plantaris muscle longitudinally. After controlling bleeding, a single 6-0 nylon suture was placed through the midpoint of the wound and antibiotic ointment was applied. Mice used in these experiments did not show evidence of infection in the paws or wound dehiscence at the time of behavioral or biochemical assays.

Drug administration

Chronic morphine administration

Mice received subcutaneous morphine (Sigma Chemical, St. Louis, MO) injections twice per day on an ascending schedule: day 1, 10 mg/kg; day 2, 20 mg/kg; day 3, 30 mg/kg and day 4, 40 mg/kg in 50 μl to 100 μl volumes as described previously 37. Saline vehicle injections in control animals followed the same twice daily schedule. Incision and nociceptive testing procedures began approximately 18 hours after the final dose of morphine or saline. This morphine administration protocol has been used extensively by the lab in studying opioid tolerance, dependence and hyperalgesia 22, 23, 37.

Mouse recombinant CXCL1 administration

Mouse recombinant CXCL1 (R&D Systems, Minneapolis, MN) was freshly prepared in 0.9% saline, which was the vehicle used for control injections. CXCL1 or vehicle was injected intra-plantar in the right hindpaws of normal mice 100ng/15ul. The dose was chosen based on the previous findings that local or central administration of similar doses of CXCL1 caused nociceptive sensitization in other models 14, 43.

SB225002 administration

The selective CXCR2 antagonist SB225002 (Cayman Chemical, Ann Arbor, MI) was freshly prepared in 100% ethanol as a stock solution (50mg/ml), which was further diluted in 0.9% saline prior to use. Mice received either SB225002 (100μg) or vehicle (5% ethanol in 0.9% saline) intraplantar on day 1 after incision in a volume of 15μl. The dose was chosen based on the previously reported finding that at this dose SB225002 significantly reduced carrageenan induced hypersensitivity in mice 27.

Suberoylanilide Hydroxamic Acid administration

Suberoylanilide Hydroxamic Acid (SAHA, Cayman Chemical, Ann Arbor, MI) was freshly dissolved in a vehicle of dimethyl sulfoxide (DMSO) (Sigma Chemical, St. Louis, MO). The concentration was adjusted to 40 μg/μl so that 50 mg/kg dose could be administrated intraperitoneally in a volume of 12.5 μl/10g body weight. An equal volume of DMSO was injected as vehicle. Animals received intraperitoneal injection of SAHA (50 mg/kg) 1 day before hindpaw incision, 2 hours before incision and each morning for 3 days after incision. The selected SAHA dose was based on our previous studies demonstrating that this dose of SAHA enhanced incision-induced histone acetylation and nociceptive sensitization 39.

Nociceptive testing

All nociceptive testing was done with the experimenter blind to drug treatment.

Mechanical hypersensitivity

Mechanical nociceptive thresholds were assayed using von Frey filaments according to a modification of the “up-down” algorithm described by Chaplan et al 6 as described previously 9, 24, 38. Mice were placed on wire mesh platforms in clear cylindrical plastic enclosures of 10 cm diameter and 30 cm height. After 20 minutes of acclimation, fibers of sequentially increasing stiffness with initial bending force of 0.2 gram were applied to the plantar surface of the hindpaw adjacent to the incision, just distal to the first set of foot pads and left in place 5 sec with enough force to slightly bend the fiber. Withdrawal of the hindpaw from the fiber was scored as a response. When no response was obtained, the next stiffer fiber in the series was applied in the same manner. If a response was observed, the next less stiff fiber was applied. Testing proceeded in this manner until 4 fibers had been applied after the first one causing a withdrawal response allowing the estimation of the mechanical withdrawal threshold using a curve fitting algorithm 33.

Thermal sensitization

Paw withdrawal response latencies to noxious thermal stimulation were measured using the method of Hargreaves et al. 15 as we have modified for use with mice 24. In this assay, mice were placed on a temperature-controlled glass platform (29 °C) in a clear plastic enclosure. After 30 min of acclimation, a beam of focused light was directed towards the same area of the hindpaw as described for the von Frey assay. A 20 s cutoff was used to prevent tissue damage. The light beam intensity was adjusted to provide an approximate 10s baseline latency in control mice. Three measurements were made per animal per test session separated by at least one minute.

RNA isolation and real-time quantitative polymerase chain reaction (PCR) amplification

Mice were first euthanized by carbon dioxide asphyxiation and an ovular full-thickness patch of skin providing 1.5- to 2-mm margins surrounding the hindpaw incisions was collected. Spinal cord tissue was harvested by extrusion. Lumbar spinal cord segments were dissected on a chilled surface. Dissected tissue was then quick-frozen in liquid nitrogen and stored at −80°C until required for analysis. For real-time quantitative PCR, total RNA was isolated from skin and spinal cord using the RNeasy Mini Kit (Qiagen, Valencia, CA) according to the manufacturer’s instructions. The purity and concentration were determined spectrophotometrically. The total RNA samples were reverse transcribed into complementary DNA using a First Strand complementary DNA Synthesis Kit (Invitrogen, Carlsbad, CA). Real-time PCR was performed in an ABI prism 7900HT system (Applied Biosystems, Foster City, CA). All PCR experiments were performed using the SYBR Green I master kit (Applied Biosystems). The primer sets for 18S message RNA(mRNA) and the amplification parameters were described previously 38. Melting curves were performed to document single product formation and agarose electrophoresis confirmed product size. The CXCR2 and CXCL1 primers were purchased from SABiosciences (SABiosciences, Valencia, CA). As negative controls, RNA samples that were not reverse transcribed were run. Data were normalized to 18S mRNA expression.

CXCL1 enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay (ELISA)

The skin samples were dissected as described in section 2.5. Mouse hindpaws were homogenized at 4°C in PBS in the presence of protease inhibitor cocktail (Roche, Mannheim, Germany). The samples were then centrifuged for 10 minutes at 12,000 rpm. The levels of CXCL1 expression in skin were measured in the supernatant by enzyme immunoassay using a commercial kit (R&D systems, Minneapolis, Minnesota) according to the manufacturer’s instructions. All samples were run in duplicate and the analyte concentrations were calculated in relation to a standard curve.

Chromatin immunoprecipitaion (ChIP) assay

ChIP assay was performed by using a commercially available ChIP kit according to the manufacturer’s protocol (Millipore, Billerica, MA). Briefly, the fresh spinal cord samples were cross-linked in phosphate buffered saline containing 1% formaldehyde (Sigma) and then quenched with glycine to a final concentration of 125 mM as previously described 23. Lysates were sonicated on ice for 8 min (10 seconds on and 10 seconds off) using Vibra Cell sonicator with a 2-mm microtip, followed by immunoprecipitation with specific antibody (5μg) against acetylated histone H3 at lysine 9 (AcH3K9) (Millipore) or IgG (Millipore) as negative control. Input control consisted of 1% sonicated chromatin. Target gene promoter enrichment in ChIP samples was measured in duplicate by quantitative PCR. Primer sequences used to amplify the promoter region were designed by the Primer 3 program: CXCL1, ATCTAGGAACCCCCTCCTCA (forward), and AGCATCCCTACCCTGCTGTA (reverse). Data were analyzed using the 2- Ct method and normalized with input samples as described previously 39. Melting curves were performed to document single product formation and agarose electrophoresis confirmed product size.

Tissue processing and immunohistochemistry

The technique of immunohistochemical analysis was described previously 23. Briefly, the skin samples were fixed in 10% buffered formalin for 24 h. Blocking of the sections took place overnight at 4°C in PBS containing 10% normal donkey serum, followed by exposure to the primary antibodies, including goat anti-CXCL1 polyclonal antibody (1:100, sc-16961, Santa Cruz, Dallas, TX), rat anti-neutrophil (allotypic marker) monoclonal antibody (1:300, MCA771GA, AbD Serotec, Raleigh, NC), or rabbit anti-acetylated histone H3K9 (AcH3K9) antibody (1:1000, GTX12179, Epigentek, Brooklyn, NY) overnight at 4°C, and all of these primary antibodies have been validated for immunohistochemistry in our previous publication 10, 36, 39. Double-label immunofluorescence was performed with donkey anti-goat IgG conjugated with Alexa Fluor 488, or donkey anti-rat or rabbit IgG conjugated with Alexa Fluor 594 secondary antibodies. Confocal laser-scanning microscopy was carried out using a Zeiss LSM/510 META microscope (Thornwood, NY). Sections from control and experimental animals were processed in parallel. Control experiments omitting either primary or secondary antibody revealed no significant staining. The numbers of AcH3K9 positive cells and AcH3K9 and CXCL1 co-localized cells were counted by a blinded experimenter in 10–15 randomly selected high-power fields (HPF, 400X) of skin wound areas per animal.

Statistical analysis

All data are expressed as mean ± standard error of the mean (SEM). Data from behavioral tests in different groups were analyzed by two-way ANOVA followed by Bonferroni’s post-hoc test for multiple comparisons. The time course changes of gene expression and ChIP assay within each group was analyzed by one-way ANOVA with post-hoc Dunnett’s testing. Comparisons between two groups for gene expression and ChIP assay were analyzed by unpaired t-test at each timepoint. For within and between group comparisons for immunostaining morphometric analysis data were analyzed by unpaired t-test. The data for CXCL1 protein levels were analyzed by one-way ANOVA followed by Bonferroni’s post-hoc test for multiple comparisons. P values less than 0.05 were considered significant (Prism 5; GraphPad Software, La Jolla, CA).

Results

Chronic morphine administration enhanced incision-induced nociceptive sensitization

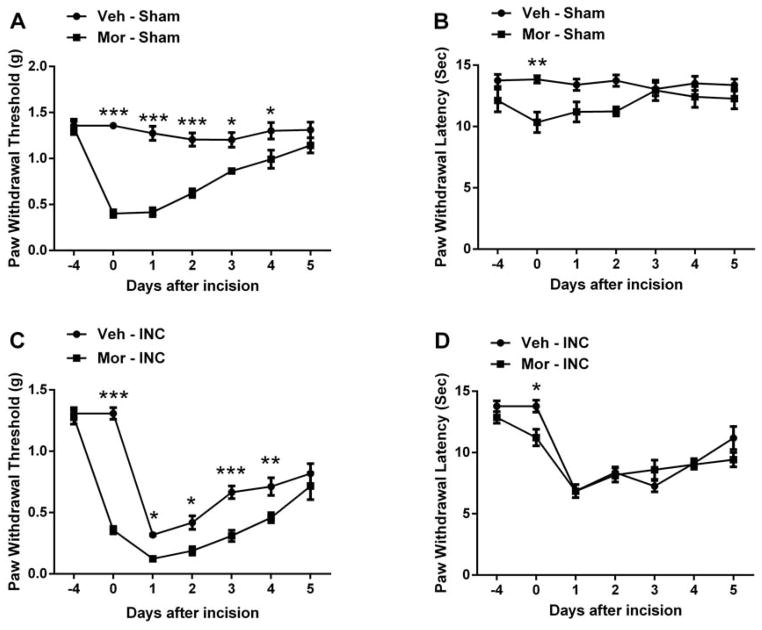

Similar to our previous observations 21, 22, 37, 4 days escalating doses of morphine pre-administration induced mechanical allodynia and thermal sensitization in mice (Fig 1A and 1B). Moreover, chronic morphine pretreatment also significantly exacerbated incision-induced mechanical hypersensitivity without significant alteration of thermal sensitivity (Fig 1C and 1D).

Figure 1.

Assessment of mechanical and thermal sensitivity after chronic morphine treatment and/or hand paw incision. Chronic morphine treatment causes mechanical allodynia (A) and thermal sensitization (B). Chronic morphine treatment enhanced incision-induced mechanical allodynia (C), without alteration of thermal sensitivity (D). Animals received prior subcutaneous injection of escalating morphine or vehicle (saline) for 4 days. Incision and nociceptive testing procedures began approximately 18 hours after the final dose of morphine or saline. Incisions were made after measuring nociceptive thresholds at day 0. Values are displayed as the mean ± SEM. N=6. *p<0.05, **p<0.01 or *** p<0.001. Veh=vehicle; Mor=morphine; INC= incision.

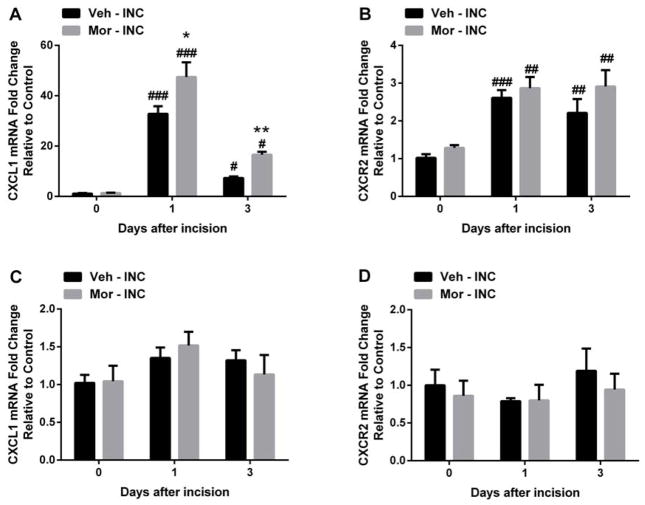

Peripheral but not central CXCL1/CXCR2 expression was increased by incision and/or morphine administration

Because the CXCL1/CXCR2 signaling pathway induced marked nociceptive sensitizations in several animal pain models 4, 19, 26, 39, we first examined the effects of incision and chronic morphine treatment on peripheral CXCL1 and CXCR2 expression. The mRNA levels of CXCL1 and CXCR2 were significantly increased in skin at both day 1 and day 3 after incision (Fig 2A and 2B). Peripheral CXCL1 mRNA levels were further increased in mice with prior morphine treatment (Fig 2A). Chronic morphine pretreatment didn’t alter the peripheral mRNA levels of CXCL1 and CXCR2 at day 0 compared with vehicle treated group (Fig 2A and 2B). Then, we examined the effects of incision and chronic morphine treatment on spinal CXCL1 and CXCR2 expression. Fig 2C and Fig 2D showed that neither incision nor incision/morphine treatment altered the mRNA levels of CXCL1 and CXCR2 expression in spinal cord.

Figure 2.

Changes in CXCL1 and CXCR2 mRNA expression in skin and spinal cord tissue after incision and/or chronic morphine treatment. (A) The mRNA level of CXCL1 was significantly increased in skin after incision and further increased with chronic morphine treatment. (B) The mRNA level of CXCR2 was significantly increased after incision. Neither incision nor morphine treatment altered the mRNA expression of CXCLl (C) and CXCR2 (D) in spinal cord tissue. Values are displayed as the mean ± SEM. N=5. # p<0.05, ## p<0.01, ### p<0.001 vs. day 0 (before incision); * p<0.05, ** p<0.01 vs. vehicle treated group. Veh=vehicle; Mor=morphine; INC= incision.

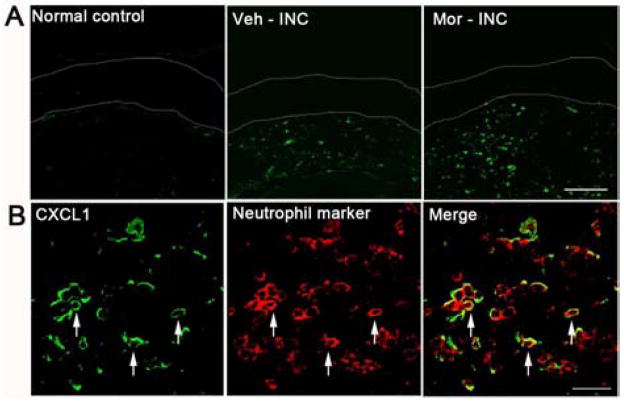

Next, we sought to define which cells in the skin expressed CXCL1. Incision induced the up-regulation of CXCL1 protein localized to the dermal layer, and the number of CXCL1 positive cells was further increased with prior morphine treatment (Fig 3A). In addition, immunostaining for CXCL1was strongly co-localized with a neutrophil marker at day 1 after incision in mice with morphine pretreatment (Fig 3B).

Figure 3.

Expression of CXCL1 in skin tissue at 1 day after incision. (A) Expression of CXCL1 was increased after incision and further increased in mice treated with morphine in the dermal layer. The epidermal layer was labeled by two dotted lines. Scale bar: 100 μm; (B) Double immunostaining showed that most CXCL1 (green) and neurtrophils (red) were co-localized (arrows) in the dermal layer at 1 day after incision in mice pretreated with morphine. Scale bar: 20 μm. Veh=vehicle; Mor=morphine; INC= incision.

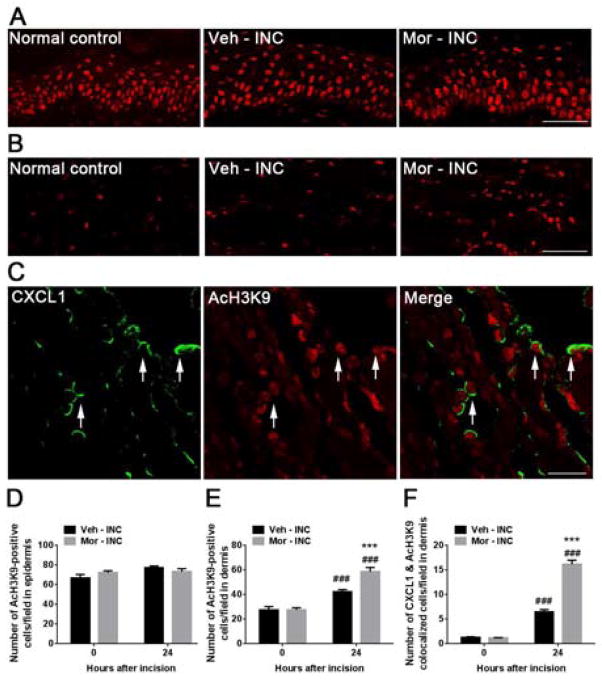

Histone acetylation was induced by incision and morphine administration

We examined hindpaw tissue for changes in histone acetylation caused by incision and chronic morphine treatment. Immunohistochemical data demonstrated that incision significantly increased acetylation of H3K9 in the dermis of hindpaw skin samples at 1 day after incision (Fig 4B and 4E) without alteration in epidermis (Fig 4A and 4D). Furthermore, acetylation of H3K9 was further increased in skin in morphine pretreated compared with vehicle treated mice (Fig 4B and 4E). In addition, the number of CXCL1 and AcH3K9 co-localized cells was increased after incision and further increased at day 1 in mice with prior morphine treatment (Fig 4C and 4F).

Figure 4.

Levels of acetylated histone H3 at lysine 9 (AcH3K9) in skin tissue at 1 day after incision. (A) Levels of acetylated H3K9 were unchanged in the epidermal layer after incision in both vehicle and morphine pretreated groups. Scale bar: 50 μm. (B) Expression of AcH3K9 was increased after incision and further increased in mice treated with morphine in the dermal layer. Scale bar: 50 μm. (C) Double immunostaining showed CXCL1 (green) and AcH3K9 (red) were colocolized (arrows) in the dermal layer at 1 day after incision in mice treated with morphine. Scale bar: 20 μm. (D) Quantification of AcH3K9 positive cells in the epidermis. (E) Quantification of AcH3K9 positive cells in the dermis. (D) Quantification of both CXCL1 and AcH3K9 positive cells in the dermis. Values are displayed as the mean ± SEM, n = 4, ### p<0.001 vs. day 0 (before incision); *** p<0.001 vs. vehicle treated group. Veh=vehicle; Mor=morphine; INC= incision.

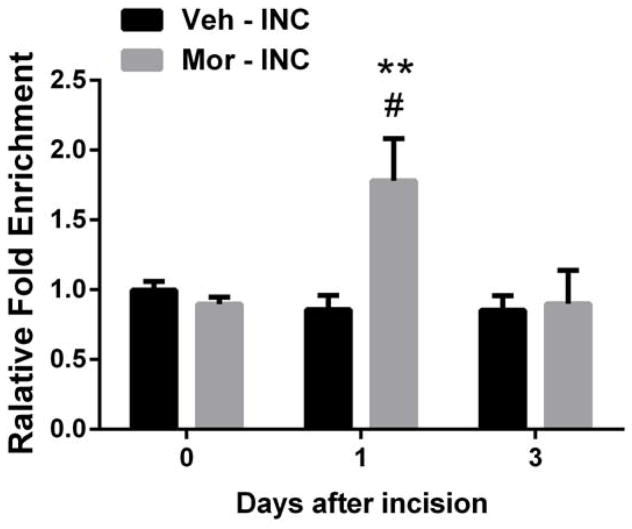

Acetylation of histone H3(AcH3K9) was increased in the promoter region of CXCL1

Above we showed that incision and chronic morphine treatment increase peripheral histone acetylation. Previously CXCL1 expression was demonstrated to be epigenetically regulated 39. Therefore, we examined specifically the association of acetylated histone protein with the CXCL1 gene promoter. ChIP assays revealed that AcH3K9 in the promoter region of CXCL1 significantly increased at 1 day in incised mice pretreated with morphine compared to incised mice treated with vehicle, however, incision per se did not support this epigenetic change (Fig 5). Additionally, there were no significant differences in the AcH3K9 fold enrichment of the promoter region of CXCL1 after chronic morphine treatment compared to controls.

Figure 5.

Chromatin immunoprecipitation (ChIP) analysis of CXCL1 in skin tissue at day 1 after incision. Histone acetylation near the CXCL1 promoter in skin significantly increased at day 1 after incision in mice treated with morphine compared with mice treated with vehicle. Values are displayed as the mean ± SEM, n = 4, # p<0.05 vs. day 0 (before incision); ** p<0.01 vs. vehicle treated group. Veh=vehicle; Mor=morphine; INC= incision.

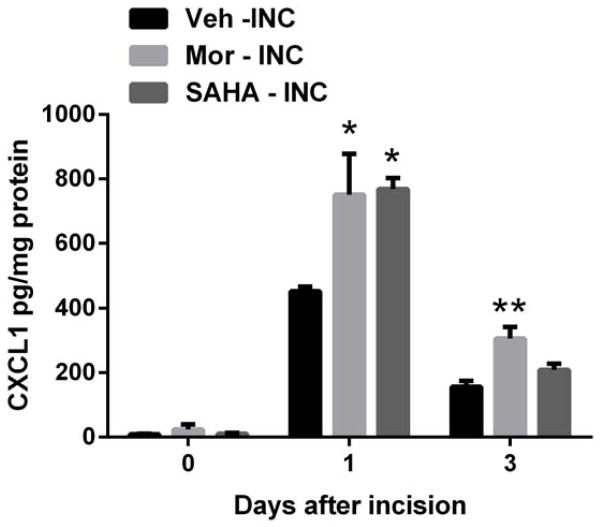

An histone deacetylase (HDAC) inhibitor mimicked the effects of chronic morphine treatment

Chronic morphine treatment increased overall histone acetylation in skin tissues after incision, enhanced association of AcH3K9 with the promoter region of CXCL1 and increased expression of CXCL1 in skin after incision. We therefore hypothesized that an HDAC inhibitor would increase peripheral CXCL1 production. Fig 6 demonstrates that the administration of HDAC inhibitor, SAHA significantly increased CXCL1 protein level at day 1 after incision, which mimicked the effect caused by chronic morphine treatment.

Figure 6.

Effects of morphine or SAHA treatment on CXCL1 expression in skin tissues after incision. The protein level of CXCL1 was monitored by ELISA and increased after incision and further increased in mice with chronic morphine or SAHA treatment. Values are displayed as the mean ± SEM, n = 5, * p<0.05, ** p<0.01 vs. vehicle treated group. Veh=vehicle; Mor=morphine; INC= incision; SAHA = suberoylanilide hydroxamic acid.

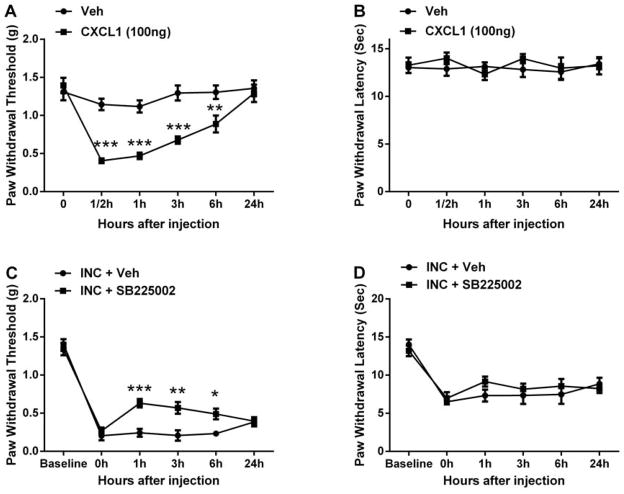

CXCL1/CXCR2 signaling was functionally involved in nociceptive sensitization

Since CXCL1 and its receptor CXCR2 were up-regulated in skin tissue after incision and further increased in mice treated with morphine, we examined whether the peripheral CXCL1/CXCR2 signaling pathway was involved in nociceptive sensitization after incision. Intraplantar injection of mouse recombinant CXCL1 (100 ng) induced mechanical allodynia in naive mice, without thermal sensitization (Fig 7A and 7B). In addition, peripheral administration of the CXCR2 antagonist SB225002 (100 μg intraplantar) at day 1 after incision significantly reversed incision-induced mechanical hypersensitivity for 6h after injection and did not have any effect on thermal sensitivity (Fig 7C and 7D).

Figure 7.

Assessment of peripheral CXCL1/CXCR2 signaling on nociceptive sensitization after incision. Intraplantar injection of recombinant CXCL1 induced mechanical allodynia (A), without effects on thermal sensitivity (B). Intraplantar injection of the CXCR2 antagonist SB225002 at 1 day after incision significantly reversed incision-induced mechanical hypersensitivity (C), also without effects on thermal sensitivity (D). Values are displayed as the mean ± SEM, n = 6, *p<0.05, **p<0.01 or *** p<0.001 vs. vehicle treated group. Veh=vehicle; INC= incision.

Discussion

Repeated administration of opioids paradoxically increases pain sensitivity, a phenomenon termed opioid-induced hyperalgesia (OIH). Moreover, chronic opioid exposure creates an exaggerated pain response to injuries such as surgical incisions. Various studies demonstrate that patients chronically consuming opioids tend to have more serious pain for a prolonged period after operations, and also need greater doses of analgesics to control postoperative pain. However, little work has been done specifically directed at understanding the mechanism involved in opioid-enhanced postoperative pain. On the other hand, chronic morphine exposure activating epigenetic mechanisms governing gene expression has been suggested to support OIH, and several proinflammatory chemokine signaling pathways are known to be epigenetic regulated such as the CXCL1/CXCR2 pathway. In these studies, therefore, we sought to explore the role of CXCL1/CXCR2 signaling in opioid-enhanced incisional hyperalgesia and elucidate the possible underlying epigenetic mechanism.

The principal findings of our studies were: 1) chronic morphine pretreatment by itself caused increased nociceptive sensitization and also enhanced incision-induced mechanical hyperalgesia; 2) peripheral CXCL1/CXCR2 signaling was up-regulated after incision, and CXCL1 was further increased with chronic morphine treatment. The involved CXCL1 was expressed primarily on neutrophils; 3) acetylated histone H3 subunit at the lysine 9 position (AcH3K9) was increased in infiltrating dermal neutrophils after incision and was further increased in mice with chronic morphine treatment; 4) there is an increased association of AcH3K9 with the promoter of the CXCL1 gene after incision with chronic morphine treatment; 5) The increase in protein levels of CXCL1 near wounds caused by chronic morphine pretreatment was mimicked by HDAC inhibitor administration after incision; 6) peripheral CXCL1/CXCR2 signaling is functionally involved in nociceptive sensitization after incision in mice. Together these observations suggest that peripheral CXCL1/CXCR2 signaling contributes to incision-induced hyperalgesia, and epigenetic regulation of CXCL1 expression could explain some portion of the opioid-enhanced postoperative nociceptive sensitization in mice.

Accumulating evidence shows that CXCL1/CXCR2 is up-regulated in peripheral and central nervous system tissue in various pain models and contributes to nociceptive sensitization. For example, expression of CXCL1 and its main receptor CXCR2 were increased in both the sciatic nerve and spinal cord in sciatic nerve ligation-induced hyperalgesia 26, 43. Intraplantar injection of carrageenan induced CXCL1 release in mouse hindpaw tissues 11. In addition, our group and others showed that incision causes CXCL1 up-regulation in wound area skin 4, 10. Administration of a CXCR2 antagonist or CXCL1 antibody attenuated neuropathic pain, inflammatory pain and incisional pain in laboratory animals 4, 19, 26, 27, 39, 43. In agreement with these findings, we also found that both CXCL1 and CXCR2 mRNA levels were up-regulated peripherally after incision. However, neither incision nor morphine treatment altered spinal CXCL1/CXCR2 expression. Importantly, peripheral CXCL1 levels after hindpaw incision were further increased in chronically morphine treated animals. Consistent with a functional role for CXCL1/CXCR2 signaling in incisional nociception, pharmacological experiments showed that intraplantar injection of recombinant CXCL1 induced mechanical hyperalgesia, whereas intraplantar injection of the CXCR2 receptor antagonist SB225002 attenuated mechanical hypersensitivity. Our data suggest that opioids enhance injury-related pain in part by augmenting the expression of injury-related mediators.

Histone acetylation at specific lysine residues is one of best-studied histone modifications and is regulated by the balance of the activities of histone acetyltransferases (HATs) and histone deacetylases (HDACs). The role of histone acetylation has been suspected of controlling pain sensitization by regulating the expression of pro- and anti-nociceptive genes. For example, immunostaining of AcH3K9 was markedly increased in the surrounding epineurium after partial sciatic nerve ligation in a neuropathic pain model 19. Similarly, we previously demonstrated incision-induced increases of AcH3K9 in spinal cord dorsal horn neurons. Blockade of HDAC activity in these mice further increased histone acetylation and exacerbated incision-induced mechanical nociceptive hypersensitivity 39. In the current study, we observed an increased number of cells with AcH3K9 in wounded skin after incision. This indicates that incision does in fact activate not only central histone acetylation, but also similar processes in the periphery.

Several recent reports suggest that chronic opioid treatment causes behavioral changes in laboratory animals through epigenetically-regulated processes 2, 8, 23, 42. For example, chronic morphine treatment activated histone H3 acetylation and reduced the overall enzymatic activity of HDAC in spinal cord 23. Altering histone acetylation by using HAT or HDAC inhibitors was shown to diminish or enhance opioid-induced hyperalgesia, tolerance and physical dependence in the same group of studies. We recently observed that morphine exposure epigenetically activated prodynorphin and brain-derived neurotrophic factor (BDNF) gene expression via histone acetylation, and selective antagonists for BDNF or dynorphin receptors could block opioid-induced hyperalgesia (unpublished observations). Similarly, Bie et al. demonstrated that epigenetic up-regulation of nerve growth factor in the central nucleus of the amygdala by morphine is directly linked to reward and sensitization-related behaviors 2. The current studies focused on the peripheral effects of chronic opioid treatment, we found that morphine enhanced peripheral AcH3K9 levels and CXCL1 expression after incision. Our ChIP experiments provided the key observation that when mice were pretreated with chronic morphine, there was an increased association of acetylated histone with CXCL1 promoter DNA after incision clearly demonstrating a functional epigenetic modification had occurred. It is noteworthy that we previously demonstrated that blockade of HDAC activity exaggerated incision-induced mechanical hyperalgesia and epigenetically regulated spinal CXCL1 expression 39, here we further demonstrated that HDAC inhibition increased CXCL1 after surgical injury in the periphery.

Previous studies suggested that chronic opioid administration could alter the production of pain-related cytokine and chemokine signaling molecules. For example, we found that wound levels of IL-1β, IL-6, TNF-α and CXCL1were greater if mice received morphine for several days prior to hindpaw incision 22. The same studies showed that the systemic administration of the broad spectrum cytokine production inhibitor pentoxifylline completely eliminated the morphine-enhancement of nociception and also reduced the excess production of IL-1β and CXCL1 caused by the chronic morphine treatment 22. The current report builds upon those results by providing a mechanism whereby morphine causes epigenetic changes within infiltrating neutrophils that lead to excess CXCL1 production. Unknown, however, is how morphine causes these epigenetic changes. Studies in preparations of neutrophils from morphine treated versus control mice may be helpful in identifying the involved mechanisms.

Antagonist ligands for CXCR2 receptors are in clinical development 16, 35. In several inflammatory disease models, blocking CXCR2 substantially decreased inflammation, tissue damage and mortality. Recently, several selective CXCR2 inhibitors have been developed that are now being tested in clinical trials. For example, SB656933 was used in trials for cystic fibrosis and ozone-induced tissue injury. Administration of SB656933 dose-dependently inhibited the up-regulation of CD11b on neutrophils and also reduced ozone-induced airway inflammation 20. Another selective CXCR2 antagonist SCH527123 was also demonstrated to be a potent inhibitor of ozone-induced neutrophil recruitment in a recent clinical trial 18. The same drug has been used in patients with severe asthma where it was found that SCH527123 was safe and reduced sputum neutrophil levels 31. More relevant to the present studies, CXCL1/CXCR2 signaling has been shown to be involved in nociceptive sensitization in several pain models 4, 26, 27, 39, 43. Reductions in nociceptive sensitization from CXCR2 blockade receptors expressed on sensory neurons which in turn activate sodium ion channels thus enhancing excitability 41. It may be reasonable to suggest that CXCR2 antagonists be examined as potential postoperative analgesics that might have specific efficacy in patients chronically consuming opioids.

Based on studies in laboratory animals, several mechanisms have been proposed to explain OIH 1 including activation of the central glutaminergic system 28, enhanced production and release of excitatory neurotransmitters, induction of spinal synaptic long-term potentiation 13, increased sensitization of peripheral nociceptors 17, and influences of genetic variation 25. Our present study contributes evidence for a previously unexplored mechanism as contributing to opioid-enhanced postoperative pain, but it may not be the sole mechanism. We also acknowledge that large numbers of genes contribute to determining nociceptive sensitivity 30; our results reveal only one of what may be many genes regulated by histone acetylation under the conditions of opioid exposure and surgical incision. Future studies might also include investigations evaluating the signaling pathways leading to activation of epigenetic mechanisms after opioid exposure, incision and the combination.

According to world drug report 2013, the prevalence of opioid use has gone up in many parts of world, such as Asia and Africa, though the USA is the world’s main consumer of these drugs 40. As the mainstay therapy for the management of chronic moderate to severe pain, and because illicit opioid use is growing, we can expect that a significant number of patients presenting for surgery will have opioid use histories. Unfortunately, the preoperative use of opioids is linked to greater postoperative pain, increased analgesia requirement and a greater likelihood of experiencing opioid-related side effects 5, 32, 34. Arriving at a better understanding of the cellular and molecular mechanisms supporting opioid-enhanced postoperative pain may be the best way to identify effective therapeutic interventions. In this study, we demonstrated the role of peripheral CXCL1/CXCR2 signaling in postoperative pain in the setting of prior morphine exposure. Our observations add to the growing body of evidence that excess wound area pro-inflammatory cytokines and chemokines may contribute to the exacerbated pain levels experienced by opioid consuming patients after surgeries. Moreover, targeting CXCL1/CXCR2 signaling may be useful in treating nociceptive sensitization, particularly for postoperative pain in chronic opioid consuming patients.

Perspective.

Peripheral CXCL1/CXCR2 signaling helps to control nociceptive sensitization after incision, and epigenetic regulation of CXCL1 expression explains in part opioid-enhanced incisional allodynia in mice. These results suggest targeting CXCL1/CXCR2 signaling may be useful in treating nociceptive sensitization, particularly for postoperative pain in chronic opioid consuming patients.

Footnotes

Disclosure: The work was supported by NIH award GM079126 (Bethesda, MD, USA) and VA Merit Review award 5I01BX000881 (Washington D.C., USA). The authors declare no conflict of interests.

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

References

- 1.Angst MS, Clark JD. Opioid-induced hyperalgesia: a qualitative systematic review. Anesthesiology. 2006;104:570–587. doi: 10.1097/00000542-200603000-00025. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Bie B, Wang Y, Cai YQ, Zhang Z, Hou YY, Pan ZZ. Upregulation of nerve growth factor in central amygdala increases sensitivity to opioid reward. Neuropsychopharmacology. 2012;37:2780–2788. doi: 10.1038/npp.2012.144. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Cabanero D, Campillo A, Celerier E, Romero A, Puig MM. Pronociceptive effects of remifentanil in a mouse model of postsurgical pain: effect of a second surgery. Anesthesiology. 2009;111:1334–1345. doi: 10.1097/ALN.0b013e3181bfab61. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Carreira EU, Carregaro V, Teixeira MM, Moriconi A, Aramini A, Verri WA, Jr, Ferreira SH, Cunha FQ, Cunha TM. Neutrophils recruited by CXCR1/2 signalling mediate post-incisional pain. Eur J Pain. 2013;17:654–663. doi: 10.1002/j.1532-2149.2012.00240.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Carroll IR, Angst MS, Clark JD. Management of perioperative pain in patients chronically consuming opioids. Reg Anesth Pain Med. 2004;29:576–591. doi: 10.1016/j.rapm.2004.06.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Chaplan SR, Bach FW, Pogrel JW, Chung JM, Yaksh TL. Quantitative assessment of tactile allodynia in the rat paw. J Neurosci Methods. 1994;53:55–63. doi: 10.1016/0165-0270(94)90144-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Chapman CR, Davis J, Donaldson GW, Naylor J, Winchester D. Postoperative pain trajectories in chronic pain patients undergoing surgery: the effects of chronic opioid pharmacotherapy on acute pain. J Pain. 2011;12:1240–1246. doi: 10.1016/j.jpain.2011.07.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Ciccarelli A, Calza A, Santoru F, Grasso F, Concas A, Sassoe-Pognetto M, Giustetto M. Morphine withdrawal produces ERK-dependent and ERK-independent epigenetic marks in neurons of the nucleus accumbens and lateral septum. Neuropharmacology. 2013;70:168–179. doi: 10.1016/j.neuropharm.2012.12.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Clark JD, Qiao Y, Li X, Shi X, Angst MS, Yeomans DC. Blockade of the complement C5a receptor reduces incisional allodynia, edema, and cytokine expression. Anesthesiology. 2006;104:1274–1282. doi: 10.1097/00000542-200606000-00024. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Clark JD, Shi X, Li X, Qiao Y, Liang D, Angst MS, Yeomans DC. Morphine reduces local cytokine expression and neutrophil infiltration after incision. Mol Pain. 2007;3:28. doi: 10.1186/1744-8069-3-28. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Cunha TM, Verri WA, Jr, Silva JS, Poole S, Cunha FQ, Ferreira SH. A cascade of cytokines mediates mechanical inflammatory hypernociception in mice. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2005;102:1755–1760. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0409225102. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.de Leon-Casasola OA, Myers DP, Donaparthi S, Bacon DR, Peppriell J, Rempel J, Lema MJ. A comparison of postoperative epidural analgesia between patients with chronic cancer taking high doses of oral opioids versus opioid-naive patients. Anesth Analg. 1993;76:302–307. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Drdla R, Gassner M, Gingl E, Sandkuhler J. Induction of synaptic long-term potentiation after opioid withdrawal. Science. 2009;325:207–210. doi: 10.1126/science.1171759. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Guerrero AT, Cunha TM, Verri WA, Jr, Gazzinelli RT, Teixeira MM, Cunha FQ, Ferreira SH. Toll-like receptor 2/MyD88 signaling mediates zymosan-induced joint hypernociception in mice: participation of TNF-alpha, IL-1beta and CXCL1/KC. Eur J Pharmacol. 2012;674:51–57. doi: 10.1016/j.ejphar.2011.10.023. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Hargreaves K, Dubner R, Brown F, Flores C, Joris J. A new and sensitive method for measuring thermal nociception in cutaneous hyperalgesia. Pain. 1988;32:77–88. doi: 10.1016/0304-3959(88)90026-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Hertzer KM, Donald GW, Hines OJ. CXCR2: a target for pancreatic cancer treatment? Expert opinion on therapeutic targets. 2013;17:667–680. doi: 10.1517/14728222.2013.772137. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Hogan D, Baker AL, Moron JA, Carlton SM. Systemic morphine treatment induces changes in firing patterns and responses of nociceptive afferent fibers in mouse glabrous skin. Pain. 2013;154:2297–2309. doi: 10.1016/j.pain.2013.05.033. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Holz O, Khalilieh S, Ludwig-Sengpiel A, Watz H, Stryszak P, Soni P, Tsai M, Sadeh J, Magnussen H. SCH527123, a novel CXCR2 antagonist, inhibits ozone-induced neutrophilia in healthy subjects. Eur Respir J. 2010;35:564–570. doi: 10.1183/09031936.00048509. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Kiguchi N, Kobayashi Y, Maeda T, Fukazawa Y, Tohya K, Kimura M, Kishioka S. Epigenetic augmentation of the macrophage inflammatory protein 2/C-X-C chemokine receptor type 2 axis through histone H3 acetylation in injured peripheral nerves elicits neuropathic pain. J Pharmacol Exp Ther. 2012;340:577–587. doi: 10.1124/jpet.111.187724. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Lazaar AL, Sweeney LE, MacDonald AJ, Alexis NE, Chen C, Tal-Singer R. SB-656933, a novel CXCR2 selective antagonist, inhibits ex vivo neutrophil activation and ozone-induced airway inflammation in humans. Br J Clin Pharmacol. 2011;72:282–293. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2125.2011.03968.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Li X, Angst MS, Clark JD. Opioid-induced hyperalgesia and incisional pain. Anesth Analg. 2001;93:204–209. doi: 10.1097/00000539-200107000-00040. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Liang D, Shi X, Qiao Y, Angst MS, Yeomans DC, Clark JD. Chronic morphine administration enhances nociceptive sensitivity and local cytokine production after incision. Mol Pain. 2008;4:7. doi: 10.1186/1744-8069-4-7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Liang DY, Li X, Clark JD. Epigenetic regulation of opioid-induced hyperalgesia, dependence, and tolerance in mice. J Pain. 2013;14:36–47. doi: 10.1016/j.jpain.2012.10.005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Liang DY, Li X, Shi X, Sun Y, Sahbaie P, Li WW, Clark JD. The complement component C5a receptor mediates pain and inflammation in a postsurgical pain model. Pain. 2012;153:366–372. doi: 10.1016/j.pain.2011.10.032. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Liang DY, Liao G, Lighthall GK, Peltz G, Clark DJ. Genetic variants of the P-glycoprotein gene Abcb1b modulate opioid-induced hyperalgesia, tolerance and dependence. Pharmacogenet Genomics. 2006;16:825–835. doi: 10.1097/01.fpc.0000236321.94271.f8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Manjavachi MN, Costa R, Quintao NL, Calixto JB. The role of keratinocyte-derived chemokine (KC) on hyperalgesia caused by peripheral nerve injury in mice. Neuropharmacology. 2013;79C:17–27. doi: 10.1016/j.neuropharm.2013.10.026. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Manjavachi MN, Quintao NL, Campos MM, Deschamps IK, Yunes RA, Nunes RJ, Leal PC, Calixto JB. The effects of the selective and non-peptide CXCR2 receptor antagonist SB225002 on acute and long-lasting models of nociception in mice. Eur J Pain. 2010;14:23–31. doi: 10.1016/j.ejpain.2009.01.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Mao J, Price DD, Mayer DJ. Mechanisms of hyperalgesia and morphine tolerance: a current view of their possible interactions. Pain. 1995;62:259–274. doi: 10.1016/0304-3959(95)00073-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Miller RJ, Jung H, Bhangoo SK, White FA. Cytokine and chemokine regulation of sensory neuron function. Handb Exp Pharmacol. 2009:417–449. doi: 10.1007/978-3-540-79090-7_12. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Mogil JS. Pain genetics: past, present and future. Trends Genet. 2012;28:258–266. doi: 10.1016/j.tig.2012.02.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Nair P, Gaga M, Zervas E, Alagha K, Hargreave FE, O’Byrne PM, Stryszak P, Gann L, Sadeh J, Chanez P, Study I. Safety and efficacy of a CXCR2 antagonist in patients with severe asthma and sputum neutrophils: a randomized, placebo-controlled clinical trial. Clinical and experimental allergy : journal of the British Society for Allergy and Clinical Immunology. 2012;42:1097–1103. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2222.2012.04014.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Patanwala AE, Jarzyna DL, Miller MD, Erstad BL. Comparison of opioid requirements and analgesic response in opioid-tolerant versus opioid-naive patients after total knee arthroplasty. Pharmacotherapy. 2008;28:1453–1460. doi: 10.1592/phco.28.12.1453. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Poree LR, Guo TZ, Kingery WS, Maze M. The analgesic potency of dexmedetomidine is enhanced after nerve injury: a possible role for peripheral alpha2-adrenoceptors. Anesth Analg. 1998;87:941–948. doi: 10.1097/00000539-199810000-00037. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Rapp SE, Ready LB, Nessly ML. Acute pain management in patients with prior opioid consumption: a case-controlled retrospective review. Pain. 1995;61:195–201. doi: 10.1016/0304-3959(94)00168-E. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Reutershan J. CXCR2--the receptor to hit? Drug news & perspectives. 2006;19:615–623. doi: 10.1358/dnp.2006.19.10.1068009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Sahbaie P, Li X, Shi X, Clark JD. Roles of Gr-1+ leukocytes in postincisional nociceptive sensitization and inflammation. Anesthesiology. 2012;117:602–612. doi: 10.1097/ALN.0b013e3182655f9f. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Sahbaie P, Shi X, Li X, Liang D, Guo TZ, Qiao Y, Yeomans DC, Kingery WS, David Clark J. Preprotachykinin-A gene disruption attenuates nociceptive sensitivity after opioid administration and incision by peripheral and spinal mechanisms in mice. J Pain. 2012;13:997–1007. doi: 10.1016/j.jpain.2012.07.009. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Sun Y, Li XQ, Sahbaie P, Shi XY, Li WW, Liang DY, Clark JD. miR-203 regulates nociceptive sensitization after incision by controlling phospholipase A2 activating protein expression. Anesthesiology. 2012;117:626–638. doi: 10.1097/ALN.0b013e31826571aa. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Sun Y, Sahbaie P, Liang DY, Li WW, Li XQ, Shi XY, Clark JD. Epigenetic regulation of spinal CXCR2 signaling in incisional hypersensitivity in mice. Anesthesiology. 2013;119:1198–1208. doi: 10.1097/ALN.0b013e31829ce340. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.UNITED NATIONS OFFICE ON DRUGS AND CRIME. World Drug Report 2013. United Nations publication; New York: 2013. [Google Scholar]

- 41.Wang JG, Strong JA, Xie W, Yang RH, Coyle DE, Wick DM, Dorsey ED, Zhang JM. The chemokine CXCL1/growth related oncogene increases sodium currents and neuronal excitability in small diameter sensory neurons. Mol Pain. 2008;4:38. doi: 10.1186/1744-8069-4-38. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Wang WS, Kang S, Liu WT, Li M, Liu Y, Yu C, Chen J, Chi ZQ, He L, Liu JG. Extinction of aversive memories associated with morphine withdrawal requires ERK-mediated epigenetic regulation of brain-derived neurotrophic factor transcription in the rat ventromedial prefrontal cortex. J Neurosci. 2012;32:13763–13775. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.1991-12.2012. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Zhang ZJ, Cao DL, Zhang X, Ji RR, Gao YJ. Chemokine contribution to neuropathic pain: respective induction of CXCL1 and CXCR2 in spinal cord astrocytes and neurons. Pain. 2013;154:2185–2197. doi: 10.1016/j.pain.2013.07.002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]