Abstract

Objective

The aim of this guideline is to assist FPs and other primary care providers with recognizing features that should raise their suspicions about the presence of colorectal cancer (CRC) in their patients.

Composition of the committee

Committee members were selected from among the regional primary care leads from the Cancer Care Ontario Provincial Primary Care and Cancer Network, the members of the Ontario Colorectal Cancer Screening Advisory Committee, and the members of the Cancer Care Ontario Gastrointestinal Cancer Disease Site Group.

Methods

This guideline was developed through systematic review of the evidence base, synthesis of the evidence, and formal external review involving Canadian stakeholders to validate the relevance of recommendations.

Report

Evidence-based guidelines were developed to improve the management of patients presenting with clinical features of CRC within the Canadian context.

Conclusion

The judicious balancing of suspicion of CRC and level of risk of CRC should encourage timely referral by FPs and primary care providers. This guideline might also inform indications for referral to CRC diagnostic assessment programs.

Colorectal cancer (CRC) is one of the most common types of cancer in Canada.1 Patients who present to FPs with symptoms of CRC are often at later stages of the disease.2 In attempts to improve the rate of early detection of CRC, many jurisdictions across Canada have introduced population-based screening programs. Although CRC screening rates are increasing, they are low, and even with screening, patients with CRC can be missed.2 Therefore, patients presenting with signs and symptoms predictive of CRC will depend on their FPs and other primary care providers (PCPs) to recognize, investigate, and refer them for further assessment and management of CRC.3

In order to provide guidance for the introduction of CRC diagnostic assessment programs (DAPs) in Ontario, the Cancer Care Ontario (CCO) Provincial Primary Care and Cancer Network initiated collaboration in February 2009 with CCO’s Program in Evidence-based Care (PEBC) to form the Colorectal Cancer Referral Working Group. The working group was tasked with determining how patients presenting to FPs and other PCPs with signs or symptoms of CRC should be managed. The following questions were evaluated in completing this overall objective.

What signs, symptoms, and other clinical features that present in primary care are predictive of CRC?

What is the diagnostic accuracy of investigations commonly considered for patients presenting with signs or symptoms of CRC?

What main known risk factors increase the likelihood of CRC in patients presenting with signs or symptoms of CRC?

Which patient and provider factors are associated with delayed referral?

Does a delay in the time to consultation affect patient outcomes?

These guidelines do not address CRC screening or gastrointestinal emergencies.

Composition of committee

The working group consisted of 3 FPs (M.E.D., A.H., C.L.), 2 surgeons (M.S., W.H.), and 1 methodologist (E.T.V.). Committee members were selected from the Ontario Colorectal Cancer Screening Advisory Committee, the Provincial Primary Care and Cancer Network, and CCO’s Gastrointestinal Cancer Disease Site Group. Internal and external reviewers included FPs, gastroenterologists, radiologists, and surgeons. The work of the PEBC is supported by the Ontario Ministry of Health and Long-Term Care through CCO, and the PEBC is editorially independent from its funding source.

Methods

The methods of the practice guideline development cycle were used.4 The guideline was developed through systematic review of the evidentiary base, evidence synthesis, and input from a formal internal and external review by Canadian stakeholders. The methods and main findings are described in detail elsewhere.2,5 The recommendations were developed based on evidence from level I systematic reviews and meta-analyses, level II case-control and cohort studies, and level III expert opinion.

Many jurisdictions consider a positive screening guaiac fecal occult blood test (FOBT) result to be an indicator for increased risk of CRC. The median positive predictive value (PPV) for the combined guaiac FOBTs evaluated in a review was 5.7%.6 A recent report evaluating the FOBT used in the ColonCancerCheck program in Ontario showed a PPV of 5.4% for single (1-time) testing in asymptomatic patients.7 A PPV is the probability that the disease is truly present when the clinical feature is present or positive. Estimated PPVs of possible signs and symptoms of CRC were extracted from the peer-reviewed literature. Clinical features with pooled PPVs from our systematic review and from published meta-analyses that were equal to or greater than the PPV for a positive FOBT result were considered to indicate increased risk of CRC.

Colonoscopy is currently recommended for individuals considered to be at increased risk of CRC, such as those with a screen-positive FOBT result and individuals with a first-degree relative with CRC. Therefore, colonoscopy was also recommended for the management of patients presenting with clinical features indicative of increased risk of CRC. Published Canadian guidelines and the target wait time of 8 weeks for colonoscopy after a positive FOBT result from the ColonCancerCheck program in Ontario were used to help establish wait time recommendations.7,8

Report

What signs, symptoms, and other clinical features that present in primary care are predictive of CRC?

Table 1 provides a summary of the signs and symptoms considered to suggest increased risk of CRC presenting in primary care and their respective median PPVs that were ascertained from our systematic review.2

Table 1.

Clinical features indicating increased risk of CRC

| CLINICAL FEATURE | MEDIAN PPV (RANGE), % |

|---|---|

| Palpable rectal or abdominal mass | NA* |

| Rectal bleeding combined with weight loss | 13.0 (4.7–23) |

| Iron deficiency anemia | 11.0 (7.7–41) |

| Rectal bleeding mixed with stool | 11.0 (3.0–21) |

| Rectal bleeding in the absence of perianal symptoms | 10.8 (6.9–18) |

| Rectal bleeding combined with a change in bowel habits | 10.5 (9.2–27) |

| Dark rectal bleeding | 9.7 (7.4–17) |

| Rectal bleeding and diarrhea | 9.0 (3.4–19) |

| Rectal bleeding and age > 60 or > 65 y | 8.6 (4.6–20) |

| Rectal bleeding and age > 70 or > 75 y | 7.9 (4.9–31) |

| Change in bowel habits or diarrhea | 7.5 (0.94–14) |

| Rectal bleeding and male sex | 7.5 (2.4–17) |

| Rectal bleeding and age > 50 or > 55 y | 5.9 (4–11) |

| Rectal bleeding (undefined) | 5.3 (2.2–16) |

| Rectal bleeding and abdominal pain | 5.1 (1.7–23) |

| Rectal bleeding first episode | 5.0 (2.2–14) |

CRC—colorectal cancer, NA—not available, PPV—positive predictive value.

Individual studies reported PPVs > 15%.

What is the diagnostic accuracy of investigations commonly considered for patients presenting with signs or symptoms of CRC?

Owing to a paucity of studies examining the diagnostic accuracy of the recommended investigations and physical examination maneuvers for patients presenting with signs or symptoms of CRC, recommendations for investigations and maneuvers were based on the consensus of the working group in terms of their ease of performance in primary care and the potential provision of valuable information leading to expedited referral. Recommendations regarding a detailed workup of unexplained anemia were beyond the scope of these guidelines; FPs and PCPs can refer to existing published guidelines if indicated.9,10 Given the compelling evidence for the association between iron deficiency anemia (IDA) and CRC, a ferritin test should be ordered if anemia is present. Imaging of palpable abdominal masses might help to determine whether such masses are intracolonic or extracolonic and, thus, direct the appropriate workup and specialist referral. Proctoscopy was not recommended as a standard of care owing to a lack of evidence for its use, a lack of widespread availability, and a low rate of use in primary care. However, based on consensus, it can still be used at the discretion of the clinician. Digital rectal examination was included because it is a simple maneuver, it can be easily performed in primary care, and if a suspicious rectal mass is felt, it can provide valuable information leading to expedited referral. This is supported by 2 studies that showed that the PPV for digital rectal examination in the presence of other symptoms was above 5%.11,12 Because there were very few studies examining the diagnostic accuracy of carcinoembryonic antigen measurement, erythrocyte sedimentation rate, and other blood tests for predicting CRC in symptomatic patients, these were also not recommended and should not be ordered.

What main known risk factors increase the likelihood of CRC in patients presenting with signs or symptoms of CRC?

There is well established evidence that patients with a personal history of colorectal polyps or inflammatory bowel disease are at increased risk of CRC.13 Meta-analyses by Jellema et al and Olde Bekkink et al found high specificity but low sensitivity for a family history of CRC in symptomatic patients.14,15 Jellema et al reported a pooled PPV of 6% for a family history of CRC in symptomatic patients.14 Family history was defined as CRC in a first-degree relative in some of the included studies but was not defined in other included studies.

Referral recommendations

In order to ensure that patients are stratified appropriately according to risk, a full history, physical examination, and investigations as outlined in Box 1 should be completed.9,10 When the patient’s clinical features warrant referral, the FP or PCP should initiate the referral within 24 hours of presentation. Patients should be referred to a CRC DAP, if available, or to a specialist competent in endoscopy (Box 2).

Box 1. Clinical encounter recommendations.

A focused history and physical examination should be performed if patients present with 1 or more of the following signs or symptoms:

The focused history should determine the following details:

To supplement the history, a focused physical examination and investigations should include the following:

|

CBC—complete blood count, CRC—colorectal cancer, IBD—inflammatory bowel disease, IDA—iron deficiency anemia, MCV—mean corpuscular volume.

Box 2. Referral recommendations: Referring physicians should send a referral within 24 hours to a specialist competent in endoscopy or to a diagnostic assessment program, where available.

|

Urgent referral Expect a consultation within 2 weeks and a definitive diagnostic workup to be completed within 4 weeks of referral if a patient has at least 1 of the following:

Semiurgent referral Expect a consultation within 4 weeks and a definitive diagnostic workup to be completed within 8 weeks of referral if a patient has at least 1 of the following:

Referring physicians should include in the consultation request information about anything that can increase the likelihood of CRC:

Patients not meeting referral criteria If the unexplained signs or symptoms of patients do not meet the criteria for referral but, based on clinical judgment, there remains a low level of suspicion of CRC, then the following are appropriate:

Excessive wait times In situations where wait times for specialists to perform colonoscopy are considered excessive, referring physicians can order the following (depending on locally available resources):

This is best done in coordination with the specialist, if possible. Normal or negative results should not lead to a cancellation of the consultation. Positive results might facilitate more timely investigation of a patient |

CRC—colorectal cancer, CT—computed tomography, DCBE—double-contrast barium enema, FOBT—fecal occult blood test, IBD—inflammatory bowel disease, IDA—iron deficiency anemia.

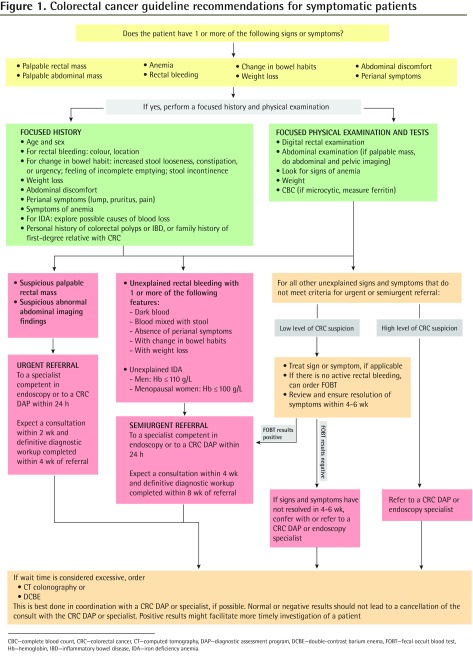

Figure 1 provides referral triage and timeliness recommendations for signs and symptoms causing suspicion of CRC.

Figure 1.

Colorectal cancer guideline recommendations for symptomatic patients

CBC—complete blood count, CRC—colorectal cancer, CT—computed tomography, DAP—diagnostic assessment program, DCBE—double-contrast barium enema, FOBT—fecal occult blood test, Hb—hemoglobin, IBD—inflammatory bowel disease, IDA—iron deficiency anemia.

Urgent referrals: In our systematic review, 3 studies found rectal and abdominal masses to be statistically significant predictors of CRC.16–18 The PPV for combined rectal or abdominal masses was 16.7% in one study.16 Two studies found PPVs of 80%17 and 22.6%18 for rectal masses and 41%17 and 16.3%18 for abdominal masses. Based on the relatively high PPVs, as well as the clinical experience of the working group, these signs were thought to require urgent consultation. Target wait times for an urgent referral include consultation within 2 weeks and completion of a definitive diagnostic workup within 4 weeks.

Semiurgent referrals: For the remaining clinical features indicating increased risk, a semiurgent referral is recommended. These include IDA and rectal bleeding, especially in combination with other clinical features. The cutoff values for hemoglobin (≤ 110 g/L for men or ≤ 100 g/L for nonmenstruating women and iron level below the normal range) were taken from the 2-week referral guideline developed by the National Institute for Health and Care Excellence in 2005 and endorsed by the New Zealand Guidelines Group in 2009.19,20 Based on consensus, the working group decided that for patients with a past medical history of inflammatory bowel disease or family history of CRC who were part of a surveillance program and who presented with interim signs or symptoms of CRC, early re-referral to specialists can be considered at the discretion of the FP or PCP for those patients who have not had recent endoscopy.

Target wait times for a semiurgent referral include a consultation within 4 weeks and completion of a definitive diagnostic workup within 8 weeks.

For signs or symptoms with lower PPVs that do not lead to referral, clinical judgment is recommended to decide whether there is a high level or low level of suspicion of CRC. Semiurgent referral is recommended if there is a high level of clinical suspicion.

Low level of CRC suspicion

If there is a low level of CRC suspicion, signs and symptoms should be treated, if indicated, and resolution in 4 to 6 weeks should be ensured. This time frame was chosen based on the clinical experience of the working group and to be consistent with the National Institute for Health and Care Excellence and New Zealand Guidelines Group guidelines that recommend referral only after symptoms persist for at least 6 weeks.19,20 If signs or symptoms have not resolved in 4 to 6 weeks, then semiurgent referral should be made. In the absence of recent CRC screening and in the absence of active rectal bleeding, a 3-sample FOBT can be considered at the discretion of the clinician. A concurrent positive FOBT result might provide additional information that would justify an expedited workup.

The use of FOBT in low-suspicion symptomatic patients is based on a 2010 meta-analysis by Jellema et al, which found good diagnostic performance for both guaiac and immunological-based FOBT tests in symptomatic patients.14 However, most of these studies were conducted in secondary care and did not provide specific signs or symptoms for which FOBT was used.

Recommendations for system-related delays to consultation

If the time to consultation is considered excessive, the referring physician can consider interim investigations. Sensitivities or specificities were higher than 83% when computed tomography colonography or double-contrast barium enema in symptomatic patients were compared with colonoscopy alone.21–33 Flexible sigmoidoscopy also showed good sensitivity for detecting CRC, especially when combined with double-contrast barium enema.22,25,31,34 There were few studies examining the diagnostic accuracy of abdominal computed tomography or abdominal or pelvic ultrasound among symptomatic patients; however, such imaging might be helpful in differentiating abdominal or pelvic masses.

Which patient and provider factors are associated with delayed referral? Does a delay in the time to consultation affect patient outcomes?

Evidence from prospective and retrospective studies suggest several factors can delay the diagnosis of CRC.19,20,35–38 Patient-related factors that were found to have the most influence on delay were patients not recognizing their symptoms as being suggestive of CRC or fear of the possible sequelae of tests or interventions that might occur. Patients with more severe symptoms, other comorbidities, or social support had shorter delays. Physician-related factors included a lack of recognition of the symptoms of CRC in patients, not investigating IDA, or not performing a rectal examination. In addition, referral to a specialist without a gastrointestinal interest or with inadequate test results provided to the specialist can lead to delays. Although overall socioeconomic status did not have a strong effect on delay, lower levels of education; living in a rural area; and being single or divorced, female, younger, black, or South Asian led to increases in delay. Furthermore, although studies suggest that longer delays in referral have not had an effect on patient mortality, the effects of psychological morbidity on patients and their families should mandate more urgent evaluation.39–45 Recommendations to address these issues are provided in Box 3.9,10

Box 3. Recommendations to reduce diagnostic delay.

|

CRC—colorectal cancer, PCP—primary care provider.

Conclusion

A systematic approach was used to identify clinical features suggestive of possible CRC that should prompt FPs and other PCPs to refer patients for expedited consultation and colonoscopy. Patients with abdominal or rectal masses should be referred urgently. In patients with IDA or rectal bleeding especially in combination with other signs or symptoms, a semiurgent referral to a specialist competent in endoscopy should be made. Other presenting symptoms should be managed, and resolution within 6 weeks should be ensured. Use of FOBTs can be considered in patients whose symptoms do not lead to urgent or semiurgent referral and for whom there is a low suspicion of CRC. For symptomatic patients who are waiting a substantial amount of time for a consultation, interim investigations can be considered. Attempts to address delays in diagnosis should be made at the patient, provider, and policy levels.

This guideline might help reduce delays in CRC diagnosis by assisting FPs and other PCPs in recognizing clinical features that should raise their suspicion about the presence of CRC and leading them to more timely and appropriate referrals. It might also guide program development for DAPs for patients with features that raise suspicion of CRC and help policy makers ensure that resources are in place so that target wait times can be achieved.

EDITOR’S KEY POINTS

Clinical features that are associated with an increased risk of colorectal cancer include a palpable rectal or abdominal mass; rectal bleeding, especially in combination with other signs and symptoms; iron deficiency anemia; and a change in bowel habits.

Patients with abdominal or rectal masses should be referred urgently to a diagnostic assessment program, if available, or to a specialist competent in endoscopy. In patients with iron deficiency anemia or rectal bleeding, especially in combination with other signs or symptoms, a semiurgent referral should be made. Other presenting symptoms should be managed, and resolution within 6 weeks should be ensured.

Footnotes

This article is eligible for Mainpro-M1 credits. To earn credits, go to www.cfp.ca and click on the Mainpro link.

This article has been peer reviewed.

La traduction en français de cet article se trouve à www.cfp.ca dans la table des matières du numéro d’août 2014 à la page e383.

Contributors

All authors contributed to the literature review and interpretation, and to preparing the report for submission.

Competing interests

None declared

References

- 1.Canadian Cancer Society [website] Cancer statistics at a glance. Toronto, ON: Canadian Cancer Society; 2014. Available from: www.cancer.ca/en/cancer-information/cancer-101/cancer-statistics-at-a-glance/?region=on. Accessed 2014 Jul 2. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Cancer Care Ontario [website] Colorectal cancer. Toronto, ON: Cancer Care Ontario; 2014. Available from: www.cancercare.on.ca/common/pages/UserFile.aspx?fileId=124403. Accessed 2014 Jul 10. [Google Scholar]

- 3.Baranek PM, editor. The patient experience. From symptoms to diagnosis. Summary of the Cancer Quality Council of Ontario 2007 signature event. “Is it cancer? Improving the patient journey to diagnosis.”. Toronto, ON: Cancer Care Ontario; 2007. pp. 12–3. Available from: www.cancercare.on.ca/common/pages/UserFile.aspx?fileId=64408. Accessed 2014 Jul 2. [Google Scholar]

- 4.Browman GP, Levine MN, Mohide EA, Hayward RS, Pritchard KI, Gafni A, et al. The practice guidelines development cycle: a conceptual tool for practice guidelines development and implementation. J Clin Oncol. 1995;13(2):502–12. doi: 10.1200/JCO.1995.13.2.502. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Del Giudice EM, Vella ET, Hey A, Simunovic M, Harris W, Levitt C. Systematic review of clinical features of suspected colorectal cancer in primary care. Can Fam Physician. 2014;60:e405–15. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Rabeneck L, Zwaal C, Goodman JH, Mai V, Zamkanei M. Cancer Care Ontario guaiac fecal occult blood test (FOBT) laboratory standards: evidentiary base and recommendations. Clin Biochem. 2008;41(16–17):1289–305. doi: 10.1016/j.clinbiochem.2008.08.069. Epub 2008 Aug 29. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Cancer Care Ontario . ColonCancerCheck. 2010 Program report. Toronto, ON: Cancer Care Ontario; 2012. Available from: www.cancercare.on.ca/common/pages/UserFile.aspx?fileId=156747. Accessed 2014 Jul 2. [Google Scholar]

- 8.Paterson WG, Depew WT, Paré P, Petrunia D, Switzer C, Veldhuyzen van Zanten SJ, et al. Canadian consensus on medically acceptable wait times for digestive health care. Can J Gastroenterol. 2006;20(6):411–23. doi: 10.1155/2006/343686. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Anemia guidelines for family medicine. 2nd ed. Toronto, ON: Medication Use Management Services Guideline Clearinghouse; 2008. Anemia Review Panel. [Google Scholar]

- 10.Goddard AF, James MW, McIntyre AS, Scott BB. Guidelines for the management of iron deficiency anaemia. London, UK: British Society of Gastroenterology; 2005. Available from: www.bsg.org.uk/images/stories/docs/clinical/guidelines/sbn/iron_def.pdf. Accessed 2009 Jul 3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Fijten GH, Starmans R, Muris JW, Schouten HJ, Blijham GH, Knottnerus JA. Predictive value of signs and symptoms for colorectal cancer in patients with rectal bleeding in general practice. Fam Pract. 1995;12(3):279–86. doi: 10.1093/fampra/12.3.279. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Wauters H, Van Casteren V, Buntinx F. Rectal bleeding and colorectal cancer in general practice: diagnostic study. BMJ. 2000;321(7267):998–9. doi: 10.1136/bmj.321.7267.998. Erratum in: BMJ 2001;322(7284):488. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Leddin D, Hunt R, Champion M, Cockeram A, Flook N, Gould M, et al. Canadian Association of Gastroenterology and the Canadian Digestive Health Foundation: guidelines on colon cancer screening. Can J Gastroenterol. 2004;18(2):93–9. doi: 10.1155/2004/983459. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Jellema P, van der Windt DA, Bruinvels DJ, Mallen CD, van Weyenberg SJ, Mulder CJ, et al. Value of symptoms and additional diagnostic tests for colorectal cancer in primary care: systematic review and meta-analysis. BMJ. 2010;340:c1269. doi: 10.1136/bmj.c1269. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Olde Bekkink M, McCowan C, Falk GA, Teljeur C, Van de Laar FA, Fahey T. Diagnostic accuracy systematic review of rectal bleeding in combination with other symptoms, signs and tests in relation to colorectal cancer. Br J Cancer. 2010;102(1):48–58. doi: 10.1038/sj.bjc.6605426. Epub 2009 Nov 24. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Barwick TW, Scott SB, Ambrose NS. The two week referral for colorectal cancer: a retrospective analysis. Colorectal Dis. 2004;6(2):85–91. doi: 10.1111/j.1463-1318.2004.00589.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Chohan DP, Goodwin K, Wilkinson S, Miller R, Hall NR. How has the ‘two-week wait’ rule affected the presentation of colorectal cancer? Colorectal Dis. 2005;7(5):450–3. doi: 10.1111/j.1463-1318.2005.00821.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Flashman K, O’Leary DP, Senapati A, Thompson MR. The department of health’s “two week standard” for bowel cancer: is it working? Gut. 2004;53(3):387–91. doi: 10.1136/gut.2003.020503. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.National Institute for Health and Care Excellence [website] Referral guidelines for suspected cancer. NICE guidelines CG27. London, UK: National Institute for Health and Care Excellence; 2005. Available from: www.nice.org.uk/CG027. Accessed 2014 Jul 2. [Google Scholar]

- 20.New Zealand Guidelines Group . Suspected cancer in primary care: guidelines for investigation, referral and reducing ethnic disparities. Wellington, NZ: New Zealand Guidelines Group; 2009. Available from: www.midlandcancernetwork.org.nz/file/fileid/17510. Accessed 2014 Jun 27. [Google Scholar]

- 21.Anderson N, Cook HB, Coates R. Colonoscopically detected colorectal cancer missed on barium enema. Gastrointest Radiol. 1991;16(2):123–7. doi: 10.1007/BF01887325. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Brewster NT, Grieve DC, Saunders JH. Double-contrast barium enema and flexible sigmoidoscopy for routine colonic investigation. Br J Surg. 1994;81(3):445–7. doi: 10.1002/bjs.1800810341. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Duff SE, Murray D, Rate AJ, Richards DM, Kumar NA. Computed tomographic colonography (CTC) performance: one-year clinical follow-up. Clin Radiol. 2006;61(11):932–6. doi: 10.1016/j.crad.2006.06.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Helfand M, Marton KI, Zimmer-Gembeck MJ, Sox HC., Jr History of visible rectal bleeding in a primary care population. Initial assessment and 10-year follow-up. JAMA. 1997;277(1):44–8. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Irvine EJ, O’Connor J, Frost RA, Shorvon P, Somers S, Stevenson GW, et al. Prospective comparison of double contrast barium enema plus flexible sigmoidoscopy v colonoscopy in rectal bleeding: barium enema v colonoscopy in rectal bleeding. Gut. 1988;29(9):1188–93. doi: 10.1136/gut.29.9.1188. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Ott DJ, Scharling ES, Chen YM, Wu WC, Gelfand DW. Barium enema examination: sensitivity in detecting colonic polyps and carcinomas. South Med J. 1989;82(2):197–200. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Roberts-Thomson IC, Tucker GR, Hewett PJ, Cheung P, Sebben RA, Khoo EE, et al. Single-center study comparing computed tomography colonography with conventional colonoscopy. World J Gastroenterol. 2008;14(3):469–73. doi: 10.3748/wjg.14.469. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Robinson C, Halligan S, Iinuma G, Topping W, Punwani S, Honeyfield L, et al. CT colonography: computer-assisted detection of colorectal cancer. Br J Radiol. 2011;84(1001):435–40. doi: 10.1259/bjr/17848340. Epub 2010 Nov 16. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Sofic A, Beslic S, Kocijancic I, Sehovic N. CT colonography in detection of colorectal carcinoma. Radiol Oncol. 2010;44(1):19–23. doi: 10.2478/v10019-010-0012-1. Epub 2010 Mar 18. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Taylor SA, Halligan S, Saunders BP, Morley S, Riesewyk C, Atkin W, et al. Use of multidetector-row CT colonography for detection of colorectal neoplasia in patients referred via the department of health “2-week-wait” initiative. Clin Radiol. 2003;58(11):855–61. doi: 10.1016/s0009-9260(03)00273-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Thompson MR, Flashman KG, Wooldrage K, Rogers PA, Senapati A, O’Leary DP, et al. Flexible sigmoidoscopy and whole colonic imaging in the diagnosis of cancer in patients with colorectal symptoms. Br J Surg. 2008;95(9):1140–6. doi: 10.1002/bjs.6234. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Tolan DJ, Armstrong EM, Chapman AH. Replacing barium enema with CT colonography in patients older than 70 years: the importance of detecting extracolonic abnormalities. AJR Am J Roentgenol. 2007;189(5):1104–11. doi: 10.2214/AJR.07.2026. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.White TJ, Avery GR, Kennan N, Syed AM, Hartley JE, Monson JR. Virtual colonoscopy vs conventional colonoscopy in patients at high risk of colorectal cancer—a prospective trial of 150 patients. Colorectal Dis. 2009;11(2):138–45. doi: 10.1111/j.1463-1318.2008.01554.x. Epub 2008 May 3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Rex DK, Weddle RA, Lehman GA, Pound DC, O’Connor KW, Hawes RH, et al. Flexible sigmoidoscopy plus air contrast barium enema versus colonoscopy for suspected lower gastrointestinal bleeding. Gastroenterology. 1990;98(4):855–61. doi: 10.1016/0016-5085(90)90007-n. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Korsgaard M, Pedersen L, Laurberg S. Delay of diagnosis and treatment of colorectal cancer—a population-based Danish study. Cancer Detect Prev. 2008;32(1):45–51. doi: 10.1016/j.cdp.2008.01.001. Epub 2008 Apr 10. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Mitchell E, Macdonald S, Campbell NC, Weller D, Macleod U. Influences on pre-hospital delay in the diagnosis of colorectal cancer: a systematic review. Br J Cancer. 2008;98(1):60–70. doi: 10.1038/sj.bjc.6604096. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Neal RD, Allgar VL. Sociodemographic factors and delays in the diagnosis of six cancers: analysis of data from the “National Survey of NHS Patients: Cancer.”. Br J Cancer. 2005;92(11):1971–5. doi: 10.1038/sj.bjc.6602623. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Singh H, Daci K, Petersen LA, Collins C, Petersen NJ, Shethia A, et al. Missed opportunities to initiate endoscopic evaluation for colorectal cancer diagnosis. Am J Gastroenterol. 2009;104(10):2543–54. doi: 10.1038/ajg.2009.324. Epub 2009 Jun 23. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Ramos M, Esteva M, Cabeza E, Campillo C, Llobera J, Aguiló A. Relationship of diagnostic and therapeutic delay with survival in colorectal cancer: a review. Eur J Cancer. 2007;43(17):2467–78. doi: 10.1016/j.ejca.2007.08.023. Epub 2007 Oct 10. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Ramos M, Esteva M, Cabeza E, Llobera J, Ruiz A. Lack of association between diagnostic and therapeutic delay and stage of colorectal cancer. Eur J Cancer. 2008;44(4):510–21. doi: 10.1016/j.ejca.2008.01.011. Epub 2008 Feb 12. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Wattacheril J, Kramer JR, Richardson P, Havemann BD, Green LK, Le A, et al. Lagtimes in diagnosis and treatment of colorectal cancer: determinants and association with cancer stage and survival. Aliment Pharmacol Ther. 2008;28(9):1166–74. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2036.2008.03826.x. Epub 2008 Aug 8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Terhaar sive Droste JS, Oort FA, van der Hulst RW, Coupé VM, Craanen ME, Meijer GA, et al. Does delay in diagnosing colorectal cancer in symptomatic patients affect tumor stage and survival? A population-based observational study. BMC Cancer. 2010;10:332. doi: 10.1186/1471-2407-10-332. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Rupassara KS, Ponnusamy S, Withanage N, Milewski PJ. A paradox explained? Patients with delayed diagnosis of symptomatic colorectal cancer have good prognosis. Colorectal Dis. 2006;8(5):423–9. doi: 10.1111/j.1463-1318.2006.00958.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Comber H, Cronin DP, Deady S, Lorcain PO, Riordan P. Delays in treatment in the cancer services: impact on cancer stage and survival. Ir Med J. 2005;98(8):238–9. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Tørring ML, Frydenberg M, Hansen RP, Olesen F, Hamilton W, Vedsted P. Time to diagnosis and mortality in colorectal cancer: a cohort study in primary care. Br J Cancer. 2011;104(6):934–40. doi: 10.1038/bjc.2011.60. Epub 2011 Mar 1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]