Abstract

The chemical structural differences distinguishing chlorophylls in oxygenic photosynthetic organisms are either formyl substitution (chlorophyll b, d, and f) or the degree of unsaturation (8-vinyl chlorophyll a and b) of a side chain of the macrocycle compared with chlorophyll a. We conducted an investigation of the conversion of vinyl to formyl groups among naturally occurring chlorophylls. We demonstrated the in vitro oxidative cleavage of vinyl side groups to yield formyl groups through the aid of a thiol-containing compound in aqueous reaction mixture at room temperature. Heme is required as a catalyst in aqueous solution but is not required in methanolic reaction mixture. The conversion of vinyl- to formyl- groups is independent of their position on the macrocycle, as we observed oxidative cleavages of both 3-vinyl and 8-vinyl side chains to yield formyl groups. Three new chlorophyll derivatives were synthesised using 8-vinyl chlorophyll a as substrate: 8-vinyl chlorophyll d, [8-formyl]-chlorophyll a, and [3,8-diformyl]-chlorophyll a. The structural and spectral properties will provide a signature that may aid in identification of the novel chlorophyll derivatives in natural systems. The ease of conversion of vinyl- to formyl- in chlorophylls demonstrated here has implications regarding the biosynthetic mechanism of chlorophyll d in vivo.

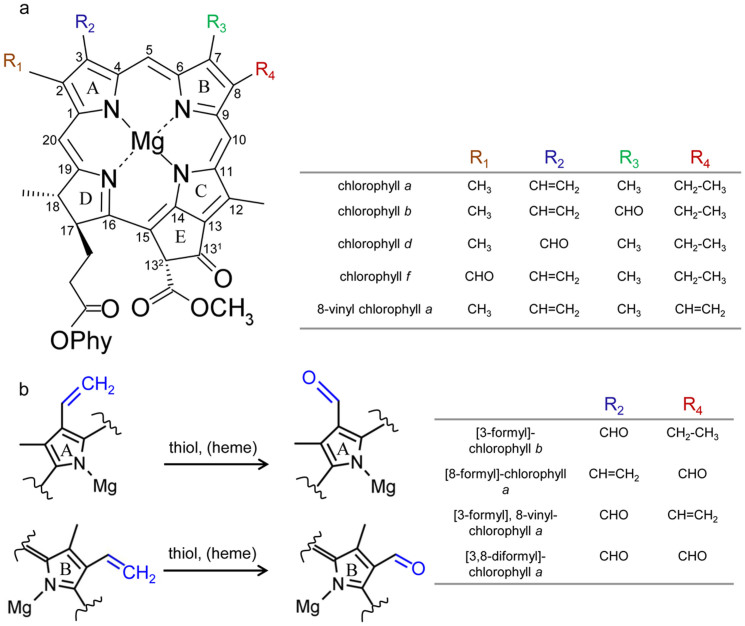

Chlorophylls are cyclic tetrapyrroles essential for photosynthesis, participating in both photon capture and conversion into chemical energy. Naturally occurring chlorophylls are distributed across oxygenic photosynthetic organisms, with Chl a predominating in most of these organisms. All chlorophylls have similar chemical structure with one or two side group substitutions. Chl b, d and f differ from Chl a by a formyl substitution at the C7, C3 and C2 positions, respectively (Figure 1a). Chl b is largely found in higher plants as well as prochlorophytes and acts as an accessory pigment. The marine cyanobacterium Prochlorococcus uniquely utilises 8-vinyl Chl a (Figure 1a) and 8-vinyl Chl b for oxygenic photosynthesis1. Both 8-vinyl Chl a and 8-vinyl Chl b have an unreduced vinyl side group at the C8 position in addition to the vinyl group at the C3 position and are also called 3,8 divinyl chlorophylls. The unicellular cyanobacterium Acaryochloris marina has replaced Chl a with Chl d for almost all photosynthetic functions2,3. The most recently discovered naturally occurring chlorophyll, Chl f, is a minor pigment that has been found in two disparate cyanobacterial lineages4,5. Replacement of either methyl or vinyl side chains of Chl a for formyl groups manifest themselves in different spectral and chemical manners, depending on the change in the distribution of electrons across the macrocycle6.

Figure 1. Chemical structures of chlorophylls and schematic of the vinyl to formyl conversion described in this study.

(a) Structures of naturally occurring chlorophylls. Carbon skeleton atoms are numbered according to the IUPAC system and rings A – E on the macrocycle are indicated. (b) partial structures of chemically synthesised formyl chlorophyll derivatives on ring A (C3) and ring B (C8). Vinyl and formyl groups are highlighted in blue. Phy, phytol (C20H39).

Chl b is synthesised from chlorophyll(ide) a via the enzyme CAO (chlorophyll(ide) a oxidase)7,8,9. CAO catalyses two hydroxylations at the C7 position of chlorophyll(ide) a, yielding an aldehyde hydrate which spontaneously forms a formyl group to yield Chl b. Chl d is also most likely synthesised from chlorophyll(ide) a10, but the enzyme(s) responsible are unknown. The biosynthesis of Chl d from Chl a must involve a different mechanism from the characterised CAO enzyme as it requires the conversion of the 3-vinyl group of Chl a to a 3-formyl group in Chl d rather than a methyl to formyl conversion as is the case for the synthesis of Chl b from Chl a. The oxidative cleavage of the 3-vinyl in Chl a (or its demetallated/dephytylated derivatives) to yield a formyl group can be achieved chemically in solvents using a strong oxidising agent11,12 or using thiol-containing compounds under acidic conditions13,14,15. Additionally, Chl d has been synthesised non-enzymatically in the presence of the cysteine protease papain16,17. Although chemical syntheses of 2-formyl chlorins have recently been described18,19, as yet there are no published data regarding the biosynthesis of Chl f.

Here we describe the oxidative cleavage of vinyl side chains of naturally occurring chlorophylls to yield formyl groups. Although not enzyme catalyzed, it progresses in a ‘biological-like' environment: in an aqueous buffer at a moderate pH and at room temperature in the presence of a thiol containing compound and heme. When methanol is used as a solvent, only the thiol-containing compound is vital for this oxidative cleavage reaction. As well as demonstrating the synthesis of Chl d from Chl a, we show this oxidative cleavage mechanism can be extended to the vinyl side group at other positions of chlorophylls, such as the 3-vinyl group in Chl b and 8-vinyl group in 8-vinyl chlorophyll a, to give formyl substitution derivatives, including [3-formyl]-Chl b, [8-formyl] Chl a, [3-formyl], 8-vinyl Chl a, and [3,8-diformyl] Chl a (or 8-formyl Chl d) under these reaction conditions (Figure 1b).

Results

Synthesis of [3-formyl]-Chl a (also named as Chl d) from Chl a

To characterise the reaction mechanism for the biosynthesis of Chl d from Chl a, we tested a number of E. coli-expressed Acaryochloris enzymes along with various cofactors, initially basing the reaction conditions on those reported to characterise the CAO enzyme in vitro8. However, rather than identifying the enzymatic synthesis of Chl d from Chl a, we determined the requirements for the non-enzymatic synthesis of Chl d from Chl a in an aqueous buffer. The minimal reaction conditions in 50 mM Tris, pH 8.0 were detergent-solubilised Chl a, heme and β-mercaptoethanol which typically yielded approximately 10% Chl d after 18 h at room temperature with stirring (Figure 2a, top panel). Replacing the aqueous buffer with methanol accelerated this reaction with almost all of the Chl a substrate consumed after 4 h (Figure 2b). Interestingly, under these conditions heme was not required for the reaction to proceed. The accelerated reaction rate observed is likely due to the increased solubility of Chl a in methanol and the 10 fold higher solubility of oxygen in methanol compared to in an aqueous buffer20. As conversion of the 3-vinyl group of Chl a to the 3-formyl group of Chl d was achieved in the presence of β-mercaptoethanol alone in methanol but not in the aqueous buffer we suggest that oxygen-bound heme is the essential reactant in the aqueous reaction mixture. Addition of hydrogen peroxide to the reaction mix accelerated the reaction significantly, most likely due to re-reduction of any oxidised heme, and when heme was removed from the reaction mix or replaced with protoporphyrin IX, almost all of the Chl a remained unreacted (data not shown).

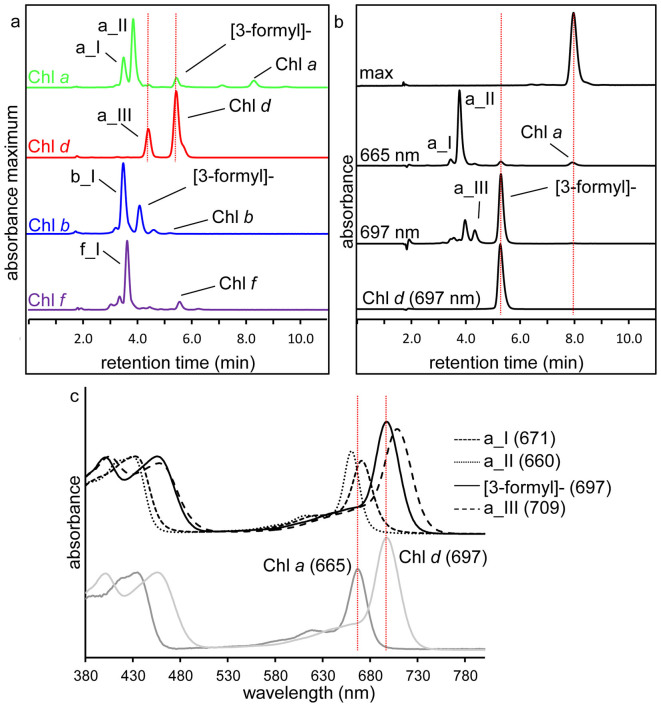

Figure 2. Reaction of monovinyl chlorophylls with β-mercaptoethanol in aqueous and methanolic environments.

(a) Spectrum maximum (maximum absorbance reading at the range of 630–710 nm) RP-HPLC chromatograms of the aqueous buffer reaction mixture after reaction with β-mercaptoethanol using purified Chl a, Chl d, Chl b or Chl f as reactant. Dotted vertical lines mark the retention time of product a_III and Chl d. For more details regarding products a_I, a_II, a_III, b_I and f_I refer to the text and Table 1. (b) RP-HPLC chromatograms of Chl a prior to (top panel) and following (two middle panels) reaction with β-mercaptoethanol in methanol, detected at indicated wavelengths. Chromatogram of Chl d from Acaryochloris (lower chromatogram) is shown for comparison with the chemically synthesised [3-formyl]-Chl a (Chl d). Dotted vertical line marks the retention time of Chl d and Chl a. (c) Online spectra of the major derivatives synthesised from Chl a. The absorption spectra of Chl a and Chl d are plotted and their Qy maxima are marked with vertical lines for comparison with synthesised products. Qy maxima are indicated (in nm).

In both methanolic or the aqueous buffer the same major products were formed, although the relative amounts of each product formed was somewhat different (Figure 2). Four detectable products were observed under both reaction conditions- products of a_I, a_II, a_III and Chl d with a small amount of unreacted Chl a remaining (Figure 2a and 2b). Chemically synthesised Chl d (or [3-formyl]-Chl a) was positively identified based on comparison of its absorption spectrum, retention time and mass with that of bona fide Chl d from Acaryochloris (Figure 2b and 2c, Table 1).

Table 1. Spectral and mass properties for Chl a, Chl b, Chl f and 8-vinyl Chl a (in bold) and their major derivatives following reaction with β-mercaptoethanol.

| Chlorophyll (Chl) and Derivatives | Soret (nm) | Qy (nm) | Soret:Qy ratio (intensity) | Mass (Da) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Chl a | 433 | 666 | 0.97 | 892 |

| a_I | 432 | 671 | 1.06 | 1062 |

| a_II ([31-βME]-Chl a) | 429 | 660 | 0.88 | 986 |

| a_III | 406 | 709 | 0.74 | 970 |

| [3-formyl]-Chl a(Chl d) | 402, 457 | 697 | 0.74 | 894 |

| Chl b | 470 | 653 | 2.4 | 906 |

| b_I ([31-βME]-Chl b) | 468 | 648 | 2.44 | 1000 |

| [3-formyl]-Chl b([3,7-diformyl]-Chl a) | 484 | 674 | 2.54 | 908 |

| Chl f | 407 | 707 | 0.90 | 906 |

| f_I ([31-βME]-Chl f) | 404 | 704 | 0.94 | 1000 |

| 8-vinyl Chl a | 443 | 667 | 1.15 | 890 |

| [31,81-diβME]-Chl a | 435 | 659 | 1.20 | 1078 |

| [31-βME, 8-formyl]-Chl a | 462 | 671 | 2.65 | 986 |

| [3-formyl,81-βME]-Chl a | 462 | 693 | 1.04 | 986 |

| [31-βME,8-vinyl]-Chl a | 440 | 661 | 1.06 | 984 |

| [3,8-diformyl]-Chl a | 487 | 687 | 2.34 | 894 |

| [81-βME]-Chl a | 438 | 664 | 1.01 | 984 |

| [8-formyl]-Chl a | 465 | 675 | 2.34 | 892 |

| [3-formyl, 8-vinyl]-Chl a(8-vinyl Chl d) | 467 | 695 | 0.99 | 892 |

Absorption maxima (in nm) are given according to HPLC online absorption spectra in 100% methanol; Soret:Qy ratios and mass (in Da) of the formyl and sulfoxide of β-mercaptoethanol (βME) derivatives are given. The chemical subunits in square parentheses represent the substituted side groups and the chemical names in normal brackets represent the alternative designated name for synthesised chlorophyll derivatives.

The major byproduct, a_II, had a slightly blue-shifted Qy maximum (c.f. Chl a) (Figure 2c) and a molecular mass of 986 Da (Table 1). Based on 1H-1H, heteronuclear single quantum coherence (HSQC) and heteronuclear multiple-bond correlation (HMBC) spectroscopy analysis, product a_II was identified as the sulfoxide derivative of [31-β-mercaptoethanol]-Chl a (Table S1, Figure S1). The most polar Chl a derivative, product a_I, had a slightly red-shifted Qy maximum relative to Chl a (Figure 2c) and a mass of 1062 Da (Table 1). This product was not characterised further, however under the same reaction conditions as described above, product a_I was synthesised from HPLC-purified product a_II (and no Chl d was produced). Another product, a_III, had a mass of 970 Da and a significantly red-shifted absorption spectrum with a Qy maximum of 709 nm (Figure 2, Table 1). Again, this product was not examined further, however it was also derived from Chl d under these reaction conditions, indicating Chl d is an intermediate product in the synthesis of a_III (Figure 2a). In order to confirm the reactive properties of 3-vinyl group of chlorophylls, both Chl b and Chl f also reacted with β-mercaptoethanol, with both yielding probable sulfoxide of [31-β-mercaptoethanol]- derivatives based on their masses, retention times and spectral properties relative to the substrate (Figure 2a, products b_I and f_I, Table 1). Strikingly, although [3-formyl]-Chl b was identified when Chl b was substrate (see below), no [3-formyl]-Chl f was observed.

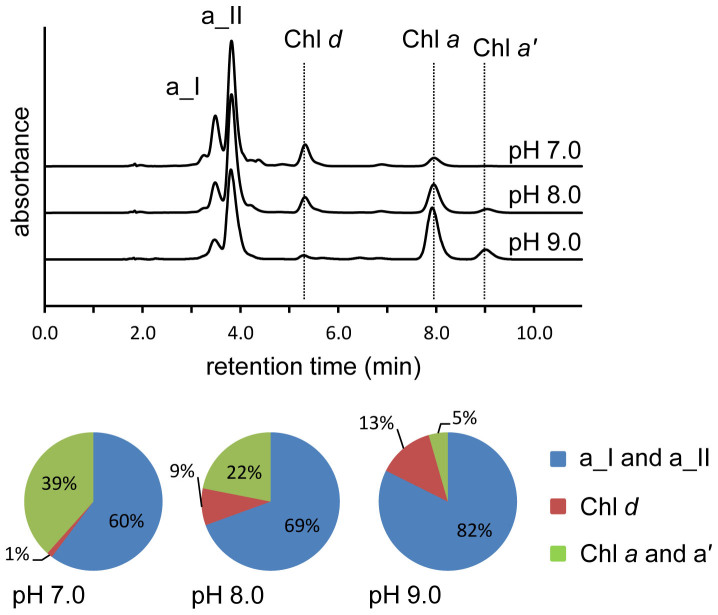

As pH affects the equilibrium protonation state of thiol reagents and therefore their function15, we examined the effect of pH on the conversion of Chl a and using β-mercaptoethanol as the thiol reagent. There was an increase in the Chl d yield (from 9% up to 13%) when the pH was reduced from 8.0 to 7.0 (Figure 3), however when the pH was dropped further to 5.6, demetallation and dephytylation of Chl a were observed (data not shown). Increasing the pH to 9.0 reduced Chl d yields significantly with Chl d making up only 1% of the chlorophyll derivatives and ~40% of the pigment remaining as Chl a or the C132-epimer, Chl a’ (Figure 3).

Figure 3. pH dependence of Chl d chemical synthesis from Chl a.

Chromatograms (spectrum maximum plots) of detergent solubilised Chl a reacted with β-mercaptoethanol and heme in a 50 mM Tris buffer at the indicated pH. Unreacted Chl a, Chl d and 31-sulfoxide of β-mercaptoethanol derivatives (a_I and a_II) are marked. Proportions of the major products and remaining Chl a and Chl a’ (the C132-Chl a epimer) are indicated in the pie charts for each pH tested.

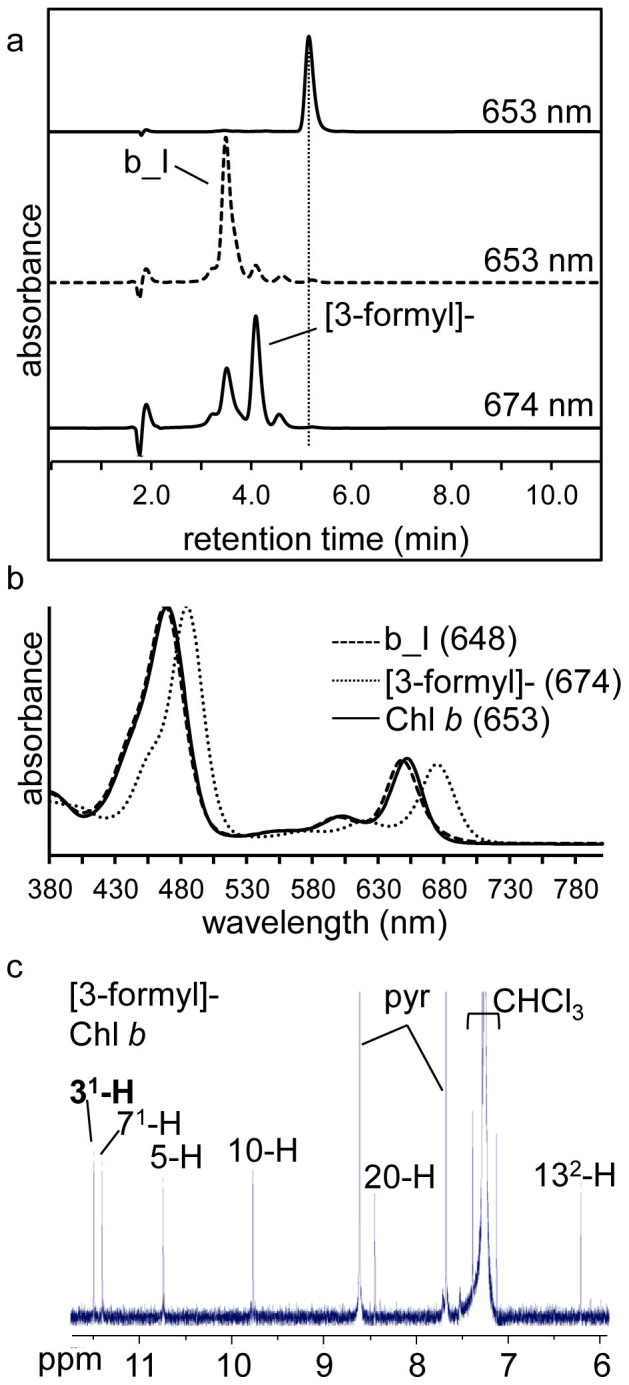

[3-formyl]-Chl d is synthesised from Chl b

Chl b differs from Chl a by a 7-methyl group of Chl a being replaced by a formyl group in Chl b (Figure 1a). The presence of the 3-vinyl group is common to both Chl a and Chl b. When Chl b was used as substrate, we also observed the conversion of its 3-vinyl to a 3-formyl group, yielding [3-formyl]-Chl b (Figure 4). [3-formyl]-Chl b showed a characteristic red shift of both the Soret and Qy peaks (cf. Chl b), with a Qy maximum of ~674 nm (Figure 3b), which is the same as that of the previously described [3-formyl]-Chl b ([7-formyl]-Chl d) synthesised in a Prochlorothrix hollandica CAO (PhCAO)-expressing Acaryochloris mutant21. The mass (908 Da, Table 1) and 1H-NMR spectrum of the [3-formyl]-Chl b confirmed the presence of both the 3-formyl and 7-formyl groups (Figure 4c). Surprisingly, the efficiency of [3-formyl]-Chl b synthesis was around 30%, assuming the extinction coefficients of the Chl b derivatives are equal, which is significantly more than the 10–12% yield observed for Chl d ([3-formyl]-Chl a) synthesis using Chl a as substrate. Additionally, the synthesis of [3-formyl]-Chl b yielded fewer byproducts compared to Chl d synthesis, with a single major byproduct, b_I, formed (Figure 2a and 4a,). As was the case with the major byproduct formed with Chl a as the substrate (a_II), this b_I had the same mass shift of plus 94 Da, reduced retention time and an absorption spectrum relative to the substrate (Chl b) and so is likely the sulfoxide derivative of [31-β-mercaptoethanol]-Chl b (Figure 4b, Table 1).

Figure 4. Synthesis of [3-formyl]-Chl b from Chl b.

(a) RP-HPLC chromatograms of Chl b prior to reaction (upper panel) and following reaction (lower panels), detected at indicated wavelength. Dotted vertical line marks the retention time of Chl b. (b) Online spectra of Chl b, chemically synthesised [3-formyl]-Chl b and product b_I. For more detail regarding product b_I refer to the text and Table 1. Qy maxima are as indicated (in nm). (c) Partial 1H-NMR spectrum of [3-formyl]-Chl b with the 31 proton in bold. Peaks corresponding to CHCl3, and pyridine (pyr) are indicated.

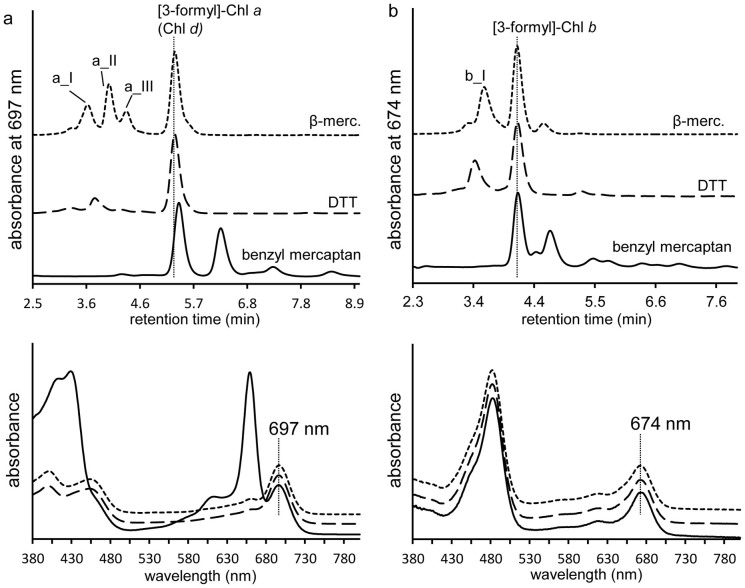

To examine the role of the thiol compound in the conversion of vinyl to formyl, different thiol compounds were tested under the same reaction conditions using either Chl a or Chl b as substrate. Replacing β-mercaptoethanol with either dithiothreitol or benzyl mercaptan also yielded the conversion of the 3-vinyl group of Chl a and Chl b to a 3-formyl group (Figure 5), and in the absence of a thiol compound no formyl group was formed (data not shown), confirming the indispensable role of the thiol group in this co-oxidative reaction.

Figure 5. Dithiothreitol and benzyl mercaptan also facilitate the conversion of the C3 vinyl of Chl a (a) and Chl b (b) to a formyl.

RP-HPLC chromatograms (top panels) demonstrate retention times of the 31-formyl derivatives of Chl a and Chl b were identical and are marked with vertical lines. Spectra (bottom panels) were identical to the 31-formyl derivatives formed in the presence of β-mercaptoethanol (β-merc.). Note, in the case of the reaction of Chl a with benzyl mercaptan, another product spectrally similar to Chl a has a similar retention time to Chl d, causing the mixed online absorption spectrum. Qy for [3-formyl]-Chl a (Chl d) and [3-formyl]-Chl b are marked. Dotted line, β-mercaptoethanol; dashed line, dithiothreitol; solid line, benzyl mercaptan.

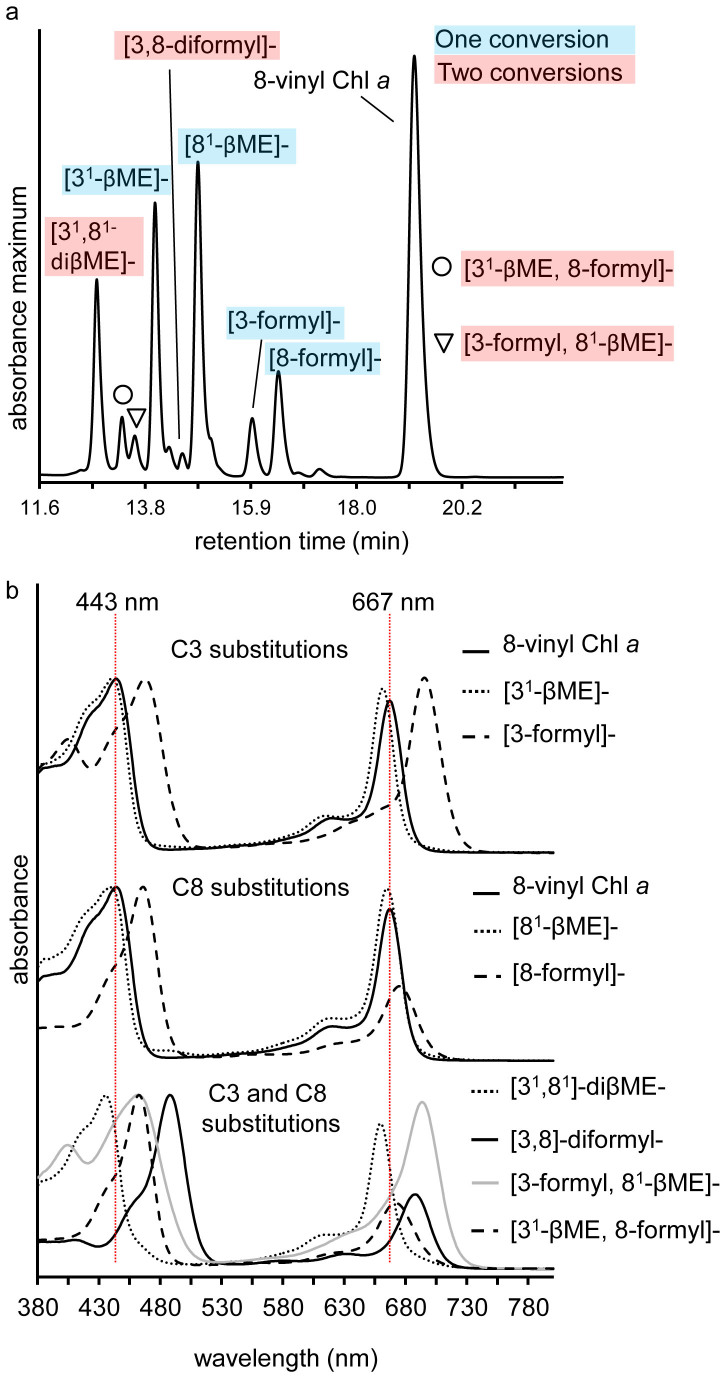

The thiol-driven reaction targets both the C3 and C8 vinyl of 8-vinyl Chl a

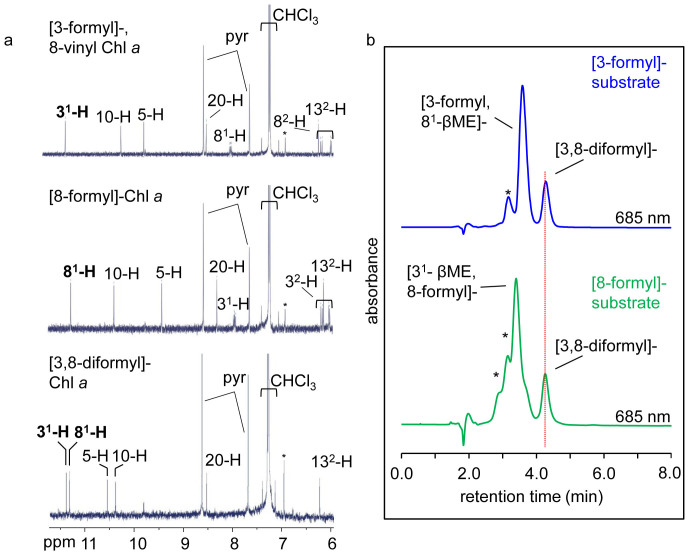

For both Chl a and Chl b, the initial reaction target is the 3-vinyl under our reaction conditions. To test whether this reaction was structurally specific to the location of vinyl group on the chlorophyll macrocycle, we reacted 8-vinyl Chl a (two vinyls, at the C3 and the C8 position, Figure 1a) with β-mercaptoethanol in methanol. A large number of polar products with varying absorption spectra were produced (Figure 6). Mass spectrometry and 1H-NMR spectroscopy confirmed two of these products corresponded to two novel formyl chlorophylls: [3-formyl], 8-vinyl Chl a (or 8-vinyl Chl d) and [8-formyl]-Chl a (Figure 7a, Table 1, Figure S2). These results demonstrate that the thiol-driven oxidative cleavage of the vinyl is not specific to a particular position on the macrocycle. When HPLC-purified [3-formyl], 8-vinyl Chl a or [8-formyl]-Chl a was reacted with β-mercaptoethanol again, both yielded the same product with a mass of 894 Da, plus 2 relative to the substrate, which we conclude is the [3,8-diformyl]-Chl a (or 8-formyl Chl d; Figure 7b, Table 1, Figure S2). This was confirmed by 1H-NMR spectroscopy, with key proton resonances for the [3,8-diformyl]-Chl a being δH(600 MHz; CDCl3; Me4Si) 6.23 (1 H, s, C13-2), 8.52 (1 H, s, C20), 10.37 (1 H, s, C5), 10.54 (1 H, s, C10), 11.31 (1 H, s, C8-1), 11.37 (1 H, s, C3-1) inter alia (Figure 7a). This [3,8-diformyl]-Chl a product was also formed when 8-vinyl Chl a was reacted with β-mercaptoethanol (Figure 4) however at the completion of the reaction the yield of [3,8-diformyl]-Chl a was only ~2% of the chlorophylls synthesised. Interestingly, this chlorophyll derivative shares spectral characteristics of both the single 3- and 8-formyl chlorophyll derivatives, with a Qy maximum of 687 nm, intermediate between the two, and an increased Soret:Qy ratio, similar to the [8-formyl]-Chl a (Figure 6b, Table 1).

Figure 6. RP-HPLC chromatogram and online absorption spectra of 8-vinyl Chl a formyl and sulfoxide of β-mercaptoethanol derivatives.

(a) RP-HPLC spectrum maximum plot of an incomplete 8-vinyl Chl a reaction after 2 h. Products with either a C3 or C8 conversion (one conversion) are marked in blue, and those products where both the C3 and C8 vinyl have reacted (two conversions) are marked with red. (b) Online spectra of 8-vinyl Chl a and the major formyl and sulfoxide of β-mercaptoethanol derivatives. The Soret and Qy maxima of 8-vinyl Chl a are marked with vertical red lines. Spectra are arithmetically shifted for clarity. βME, sulfoxide of β-mercaptoethanol.

Figure 7. Confirmation that both the C3 and C8 vinyl groups of 8-vinyl Chl a are converted to formyl groups.

(a) Partial 1H-NMR spectra of [3-formyl, 8-vinyl]-Chl a (8-vinyl Chl d), [8-formyl]-Chl a and [3, 8-diformyl]-Chl a. Formyl associated protons are in bold, CHCl3, pyridine (pyr) and solvent contaminant (*) peaks are indicated. (b) RP-HPLC chromatogram (detected at 685 nm) of completed reaction mixtures using either [3-formyl], 8-vinyl-Chl a (8-vinyl Chl d, upper panel) or [8-formyl]-Chl a (lower panel) as substrate. The peak corresponding to the [3,8-diformyl]-Chl a product is marked with a vertical dotted line. *, unknown products.

Having a formyl group at both the C3 and C8 positions also bathochromically shifts the Soret peak by approximately 20 nm relative to either of the single formyl chlorophylls (from 466 nm to 487 nm). As was the case for Chl a, Chl b and Chl f, based on mass, relative retention times and spectral characteristics, we also observed the formation of probable sulfoxide of β-mercaptoethanol (βME) derivatives as well as formyl groups, at the C3 and C8 positions of 8-vinyl Chl a. These were as follows: [81-βME]-Chl a, [31-βME], 8-vinyl-Chl a, [3-formyl, 81-βME]-Chl a, [31-βME, 8-formyl]-Chl a and [31, 81- βME]-Chl a (Figure 6, Table 1), with approximately 60% of the chlorophyll at the end of the reaction corresponding to [31, 81-βME]-Chl a (data not shown). The 31-βME derivative and the 81-βME derivatives of Chl a were distinguished by reacting these derivatives with β-mercaptoethanol to form the [31-sulfoxide, 8-formyl]- and [3-formyl, 81-sulfoxide]- derivatives respectively and comparing them to products formed from the structurally confirmed [3-formyl], 8-vinyl Chl a (8-vinyl Chl d) and [8-formyl]-Chl a (Figure 7b, Table 1).

Discussion

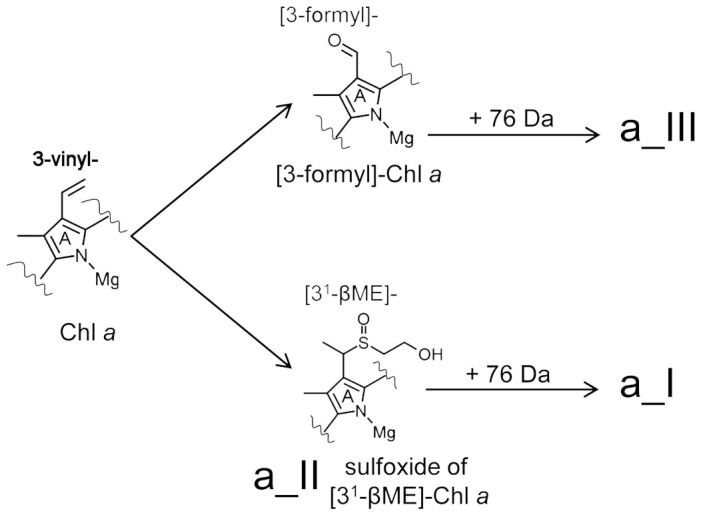

Interaction between chlorophylls and either a thiol reagent and heme in an aqueous buffer environment or thiol alone in a methanol environment leads to the synthesis of novel C3 and C8 position chlorophyll derivatives. Both Chl a and Chl b have a vinyl group at the C3 position and two reaction pathways result in the formation of either 31-sulfoxide β-mercaptoethanol derivatives, or 3-formyl derivatives (Figure 8). In the case of 8-vinyl Chl a, these reactions are extended to the C8-vinyl group.

Figure 8. Substitutions at the C3 position of ring A of Chl a mediated by β-mercaptoethanol.

The C3 vinyl position of Chl a is targeted by the thiol group of β-mercaptoethanol yielding a sulfoxide derivative of [31-β-mercaptoethanol] Chl a (product a_II), which can react further with β-mercaptoethanol to yield an unkown product (a_I) with a mass of a_II plus 76 Da. An alternate, competing reaction also targets the C3 vinyl group of Chl a, oxidatively cleaving it to yield [3-formyl]-Chl a (Chl d). As is the case for product a_II, [3-formyl]-Chl a also reacts further with β-mercaptoethanol to yield an unknown product (a_III) with a mass of [3-formyl]-Chl a plus 76 Da. Structure of product a_II and synthesized Chl d is confirmed by NMR anaylsis (details see supplementary information).

Using the HPLC-purified 31-sulfoxide derivative (a_II) as a reactant under the same reaction conditions, only product a_I was produced, so therefore the 31-sulfoxide derivative is not a precursor to the formation of the 3-formyl group, which is consistent with the observation by Oba et al.14. Incubation of Chl d under these reaction conditions also yielded another product, product a_III (Figure 2a). Relative to their precursors, both a_I and a_III have a red-shifted Qy maximum and an increased mass of 76 Da. Unfortunately insufficient product was yielded for structural analysis of these derivatives. Co-oxidation of thiols and olefins, particularly conjugated olefins, has previously been observed, and an anti-Markovnikov reaction mechanism has been suggested22. This reaction scheme has been used to explain the thiol attack on the 3-vinyl group of Chl (or pheophorbide) a and formation of the 31-formyl13,15. We have shown here that these two reaction pathways are independent of the position of vinyl group at the macrocycle, i.e. both the C3 and the C8 vinyl group in 8-vinyl Chl a may be oxidatively cleaved to give the corresponding formyl derivative as well as the sulfoxide products (Figure 6). These data support the fact that there are different reaction mechanisms for the formation of the formyl groups converted from vinyl group at the C3 (or C8 in vitro) position compared to the methyl group at the C7 or C2 positions, corresponding to the naturally occurring Chl d, Chl b and Chl f respectively.

The reactivity of the vinyl group of chlorophylls with β-mercaptoethanol was strongly dependent on the presence of heme in an aqueous buffer whereas in methanol heme was not required for the formation of the formyl group and other β-mercaptoethanol derivatives. Oxygen is approximately 10 times less soluble in water than methanol20. This suggests that it is the ability of heme to promote oxygen radical formation in water as well as its ability to deliver the oxygen to the chlorophyll molecule, that allows these thiol driven reactions to take place in an aqueous, relatively low oxygen environment. A number of lines of evidence support this hypothesis: No Chl d was synthesised from Chl a when the heme was either removed or replaced with protoporphyrin IX in the aqueous reaction mixture. Reaction kinetics were accelerated when hydrogen peroxide was added to the reaction mix. Furthermore, it has been shown previously that the presence of the radical scavenger ascorbic acid significantly reduces the synthesis of pheophorbide d from pheophorbide a under similar reaction conditions15.

Previously, it has been shown that under acidic conditions, pheophorbide d can be produced from pheophorbide a in either a micellar15 or organic solvent14 environment in the presence of hydrogen sulfide or thiophenol respectively. More recently, it has been shown that under less acidic conditions, demetallation and dephytylation of the chlorophyll can be avoided, allowing the synthesis of Chl d from Chl a in organic solvents13, which agrees well with the optimal pH range of 7–8 observed in our experiments. Our results expand on these previous reports with the observation that other thiol-containing reagents such as β-mercaptoethanol, benzyl mercaptan and dithiothreitol can drive this reaction under mild conditions, either for detergent-solubilised chlorophyll in aqueous reaction buffer or chlorophyll in a methanolic reaction mixture.

Three new [formyl-] chlorophyll derivatives are synthesised using 8-vinyl Chl a as the reactant, 8-vinyl Chl d (or [3-formyl]-8-vinyl-Chl a), [8-formyl]-Chl a and [8-formyl]-Chl d (or [3,8-diformyl]-Chl a)(Figure 6). The different spectral profiles of the formyl derivatives of chlorophylls synthesised in this study can be explained by shifts in the electronic configuration caused by the electronegative oxygen atom23. The 8-vinyl Chl d has a similar Qy absorption peak to (8-ethyl) Chl d, due to the electron withdrawing effect of the oxygen atom, along the Y axis of the chlorophyll. Distinctly though, the Soret peak is bathochromically shifted ~10 nm toward the green window region, which is analogous to the spectral changes from Chl a to 8-vinyl Chl a1. It is believed that 8-vinyl Chl a and 8-vinyl Chl b in Prochlorococcus confer an advantage, enabling the organism to thrive in the open ocean at depths down to 200 m due to the approximately 10 nm bathochromic shift in their Soret-bands matching the available blue light there24. This bathochromic shift in the Soret peak is even more pronounced in both the [3,8-diformyl]-Chl a and [3,7-diformyl]-Chl a with Soret maxima of 487 and 484 nm respectively (Table 1). At least in the case of the [3,7-diformyl]-Chl a ([3-formyl]-Chl b or [7-formyl]-Chl d), synthesis of this chlorophyll in Acaryochloris leads to a modest increase in the in vivo absorption at around 480 nm21, and the chlorophyll is incorporated into the antenna of photosystem II25. So although as yet these formyl chlorophylls have not yet been identified in nature, it would appear that at least spectrally, they may provide a competitive advantage in some instances, absorbing wavelengths of light not absorbed by other organisms. Our data provide a spectral signature for these novel formyl chlorophylls, which should aid in their identification in nature, if they are present. We observed that any formyl group substitution on ring B (either at position C7 or C8) caused a dramatic decrease in the intensity of the Qy peak, which is also the case with the C7 formyl substitution in Bchl e and f from Bchl c or d respectively26. The red shift in the Qy peak of [8-formyl]-Chl a relative to the 8-vinyl Chl a was initially surprising as it is the opposite of the blue shifted Qy peak of the structurally similar Chl b (Table 1). The transition dipole moment of the Qy axis in Chl a lies almost along the line bisected by C2 and C11 axis27. Thus adding an electron withdrawing formyl group along the axis, such as in Chl d and Chl f, would be expected to red shift the Qy absorbance maxima while adding an electron withdrawing substituent at right angles to this axis such as in Chl b would blue shift the Qy absorbance maxima. As an 8-formyl group is close to being along this Qy axis this would explain the observed red shift in of [8-formyl]-Chl a.

Here for the first time we show that [3-formyl]-Chl b can also be synthesised from Chl b in the presence of a thiol (Figure 4). Although the 10% yield of Chl d synthesised from Chl a under our reaction conditions was less than the 31% reported by Fukusumi et al.13, our results for [3-formyl]-Chl b synthesis (30% yield) were comparable, and this is achieved for detergent-solubilised Chl b rather than in an organic solvent such as chloroform or the alcohol methanol. Reaction kinetics can be increased around 3-fold in the methanolic reaction mixtures instead of the aqueous reaction mixture, however the relative yields of each product remain largely unaffected. A series of novel chlorophyll derivatives are formed by using 8-vinyl Chl a as substrate due to the oxidative cleavage independently at either the 3-vinyl or 8-vinyl position of 8-vinyl Chl a (Figure 6). Yield of the 3- and 8-formyl derivatives of 8-vinyl Chl a was difficult to measure as they were both intermediates, reacting further with the β-mercaptoethanol. Assuming the extinction coefficient of Chl d for the 3-formyl derivative and that of Chl b for the 8-formyl derivative (which it resembles spectrally and likely has a similar molecular extinction coefficient to) the average ratio of formation of formyl group at C3 and C8 positions is 0.6:1. It may be that the C8 vinyl is more reactive than the C3 vinyl, as a similar trend is observed when comparing the relative synthesis of 31 and 81 sulfoxide of β-mercaptoethanol derivatives.

Despite the obvious advantage of being able to exploit far red light for oxygenic photosynthesis, increasing available photons by approximately 14%28, as yet only the monophyletic Acaryochloris has been shown to utilise Chl d. We have demonstrated, at least in vitro, the simplicity with which Chl d can be synthesised from Chl a in an aqueous buffer. Whether these thiol-driven reactions shed light on the in vivo synthesis of formyl groups from vinyl on the chlorophyll macrocycle remains uncertain. Clearly, in addition to the synthesis of Chl d, Acaryochloris must have had to acquire the ability to efficiently utilise this chlorophyll in its photosytems. For example the Acaryochloris D1 protein, located in the reaction center of photosystem II, has a cysteine residue in place of a conserved glycine in Chl a-utilising photosynthetic organisms29. Interestingly, 8-vinyl Chl a-utilising Prochlorococcus also have a cysteine residue at this position. Acaryochloris has an unusually large genome for a unicellular cyanobacterium30 so perhaps this has allowed a certain level of gene plasticity, leading to neofunctionalisation of the ‘Chl d synthase’ and other associated changes to its photosynthetic apparatus which would be required for efficient utilisation of Chl d.

Methods

Chlorophyll isolation and quantification

All pigment extraction and purification steps were performed in a darkened room or under weak green light to avoid photo-damage. All solvents used were HPLC grade. Chl a and b were isolated from Arabidopsis seedlings by grinding leaf tissue in 100% acetone. Chl d and Chl f were extracted from Acaryochloris marina MBIC 11017 and Halomicronema hongdechloris cells respectively using 100% methanol. 8-vinyl Chl a was isolated from a Δslr1923 Synechocystis PCC 6803 mutant31 using 100% methanol. All chlorophylls were purified from total pigment using a Strata C18-T reverse phase column (200 mg/3 ml, Phenomenex, USA) and isolated from one another using a 4.6 × 150 mm Synergi 4 µm Max-RP column (Phenomenex, Australia) on a Shimadzu HPLC (model 10A series) using 100% methanol (Fisher Scientific, USA) at a flow rate of 1 ml/min. Eluted pigments were detected with a diode array absorption detector (SPD-M10Avp; Shimadzu, Japan). Purified chlorophylls were vacuum dried and stored at −80°C. Chl a and b products, following their reaction with the thiol compound, were also separated using this HPLC program. Separation of 8-vinyl Chl a reaction products was performed as described above except a 15 min linear gradient (0–100%) of solvent A (85% (v/v) methanol in 150 mM ammonium acetate) and solvent B (methanol) followed by 100% solvent B for 20 min at a flow rate of 0.9 ml/min was used. Chlorophyll concentrations were quantified by spectroscopy in 100% methanol using the following molar extinction coefficients: Chl a, ε665 nm = 70.02 × 103 L mol−1 cm−1; Chl d, ε697 nm = 63.68 × 103 L mol−1 cm−1 Chl f, ε707 nm = 71.11 × 103 L mol−1 cm−1 and Chl b, ε652 nm = 38.55 × 103 L mol−1 cm−132,33. The dried chlorophylls were resuspended in a small volume of 100% acetone immediately prior to setting up reactions. Yields of chlorophyll derivatives were determined based on peak area from the HPLC and either the published molar extinction coefficients described above or estimated based on the extinction coefficient of either the parent chlorophyll or spectrally similar chlorophyll as stated in the text.

Reaction conditions

Under standard reaction conditions, 10 µl of acetone dissolved chlorophyll was added to 3 ml of 0.02% (w/v) n-dodecyl-β-D-maltoside (Sigma) or 0.02% (v/v/) Triton X-100 in 50 mM Tris buffer, pH 8.0 plus 10 µM hemin chloride (MP Biochemicals) and 50 mM β-mercaptoethanol (Sigma). Where stated, hemin chloride was omitted or replaced with 10 µM protoporphyrin IX (Sigma), and β-mercaptoethanol was replaced with 50 mM benzyl mercaptan (Sigma) or 50 mM dithiothreitol (Sigma). For the pH experiments, pH was maintained using a 50 mM Tris buffer for pH 7–9 or 50 mM MES buffer for pH 5.6. After 18 h shaking at room temperature, unless stated otherwise, the chlorophylls and their derivatives were extracted from the reaction mix with saturated NaCl solution and 100% butanol, which was transferred to a new tube and evaporated in a vacuum concentrator. Pigments were resuspended in 100% methanol and immediately subjected to HPLC. The separated pigments were collected from the HPLC, dried using a vacuum concentrator or nitrogen gas stream, and stored at −80°C prior to mass spectrometry or NMR. For β-mercaptoethanol reactions in methanol, a small volume of acetone-solubilised chlorophyll (20 µM) was added to 50 mM β-mercaptoethanol dissolved in 100% methanol and incubated with shaking for 2–4 h. Reactions were concentrated using a nitrogen gas stream before performing HPLC.

NMR spectroscopy

All NMR experiments were performed using a Bruker Avance III-800 or Bruker Avance III-600 spectrometer at the School of Molecular Biology, University of Sydney. Dried HPLC purified samples were resuspended in chloroform-d (Sigma) with 0.5% (v/v) pyridine-d5 (Cambridge Isotope Laboratories, Inc).

Mass spectrometry

Mass spectrometry was performed as described previously.10

Author Contributions

P.C.L performed the experiments and analysed the data. R.D.W performed the NMR experiments and data processing. P.C.L, R.D.W and M.C. conceived of and designed experiments and wrote the manuscript.

Supplementary Material

Supplementary Information

Acknowledgments

The authors would like to thank Dr Ben Crossett for help with the MALDI/TOF mass spectrometry, Dr Ann Kwan for invaluable assistance with the NMR spectroscopy, Ms Yaqiong Li for her time and discussions regarding the HPLC and Dr Dan Canniffe and Prof Neil Hunter for the Synechocystis divinyl reductase mutant. This work was funded by the Australian Research Council (DP120100286). M. C. holds an Australian Research Council Future Fellowship (FT120100464).

References

- Chisholm S. W. et al. Prochlorococcus-marinus nov gen-nov sp - an oxyphototrophic marine prokaryote containing divinyl chlorophyll-a and chlorophyll-b. Arch. Microbiol. 157, 297–300, 10.1007/bf00245165 (1992). [Google Scholar]

- Loughlin P., Lin Y. & Chen M. Chlorophyll d and Acaryochloris marina: current status. Photosynth. Res. 116, 277–293, 10.1007/s11120-013-9829-y (2013). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Miyashita H. et al. Chlorophyll d as a major pigment. Nature 383, 402–402, 10.1038/383402a0 (1996). [Google Scholar]

- Akutsu S. et al. Pigment analysis of a chlorophyll f-containing cyanobacterium strain KC1 isolated from Lake Biwa. Photomed. Photobiol. 233, 35–40 (2011). [Google Scholar]

- Chen M., Li Y. Q., Birch D. & Willows R. D. A cyanobacterium that contains chlorophyll f - a red-absorbing photopigment. FEBS Lett. 586, 3249–3254, 10.1016/j.febslet.2012.06.045 (2012). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schliep M., Cavigliasso G., Quinnell R. G., Stranger R. & Larkum A. W. D. Formyl group modification of chlorophyll a: a major evolutionary mechanism in oxygenic photosynthesis. Plant, Cell Environ. 36, 521–527, 10.1111/pce.12000 (2013). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Espineda C. E., Linford A. S., Devine D. & Brusslan J. A. The AtCAO gene, encoding chlorophyll a oxygenase, is required for chlorophyll b synthesis in Arabidopsis thaliana. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 96, 10507–10511, 10.1073/pnas.96.18.10507 (1999). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Oster U., Tanaka R., Tanaka A. & Rudiger W. Cloning and functional expression of the gene encoding the key enzyme for chlorophyll b biosynthesis (CAO) from Arabidopsis thaliana. Plant J. 21, 305–310, 10.1046/j.1365-313x.2000.00672.x (2000). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tanaka A. et al. Chlorophyll a oxygenase (CAO) is involved in chlorophyll b formation from chlorophyll a. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 95, 12719–12723, 10.1073/pnas.95.21.12719 (1998). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schliep M., Crossett B., Willows R. D. & Chen M. O-18 Labeling of Chlorophyll d in Acaryochloris marina reveals that chlorophyll a and molecular oxygen are precursors. J. Biol. Chem. 285, 28450–28456, 10.1074/jbc.M110.146753 (2010). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Holt A. S. & Morley H. V. A proposed structure for chlorophyll-d. Can. J. Chem. 37, 507–514, 10.1139/v59-069 (1959). [Google Scholar]

- Aoki K. et al. in Photosynthesis Research for Food, Fuel and the Future 808–811 (Springer, 2013). [Google Scholar]

- Fukusumi T. et al. Non-enzymatic conversion of chlorophyll-a into chlorophyll-d in vitro: A model oxidation pathway for chlorophyll-d biosynthesis. FEBS Lett. 586, 2338–2341, 10.1016/j.febslet.2012.05.036 (2012). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Oba T. et al. A mild conversion from 3-vinyl- to 3-formyl-chlorophyll derivatives. Bioorg. Med. Chem. Lett. 21, 2489–2491, 10.1016/j.bmcl.2011.02.054 (2011). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pickering M. D. & Keely B. J. Origins of enigmatic C-3 methyl and C-3 H porphyrins in ancient sediments revealed from formation of pyrophaeophorbide d in simulation experiments. Geochim. Cosmochim. Acta 104, 111–122, 10.1016/j.gca.2012.11.021 (2013). [Google Scholar]

- Koizumi H. et al. Serendipitous discovery of Chl d formation from Chl a with papain. Sci. Technol. Adv. Mat. 6, 551–557, 10.1016/j.stam.2005.06.022 (2005). [Google Scholar]

- Fukuyo S., Ohashi S., Iwamoto K., Shiraiwa Y. & Kobayashi M. in Photosynthesis. Energy from the Sun (eds Allen, Gantt, Golbeck, & Osmond) Ch. 255, 1165–1168 (Springer, Netherlands, 2008). [Google Scholar]

- Liu M. et al. Regioselective [b]-pyrrolic electrophilic substitution of hydrodipyrrin-dialkylboron complexes facilitates access to synthetic models for chlorophyll f. New J. Chem. 38, 1717–1730, 10.1039/C3NJ01508D (2014). [Google Scholar]

- Xu M., Kinoshita Y. & Tamiaki H. Synthesis of chlorophyll-f analogs possessing the 2-formyl group by modifying chlorophyll-a. Bioorg. Med. Chem. Lett. In press DOI:10.1016/j.bmcl.2014.06.022 (2014). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Battino R., Rettich T. R. & Tominaga T. The solubility of oxygen and ozone in liquids. J. Phys. Chem. Ref. Data 12, 163–178 (1983). [Google Scholar]

- Tsuchiya T. et al. Metabolic engineering of the Chl d-dominated cyanobacterium Acaryochloris marina: production of a novel chl species by the introduction of the chlorophyllide a oxygenase gene. Plant Cell Physiol. 53, 518–527, 10.1093/pcp/pcs007 (2012). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- D'Souza V. T., Nanjundiah R., Baeza H. J. & Szmant H. H. Thiol-olefin cooxidation (TOCO) reaction. 9. A self-consistent mechanism under nonradical-inducing conditions. J. Org. Chem. 52, 1729–1740, 10.1021/jo00385a016 (1987). [Google Scholar]

- Hoober J. K., Eggink L. L. & Chen M. Chlorophylls, ligands and assembly of light-harvesting complexes in chloroplasts. Photosynth. Res. 94, 387–400, 10.1007/s11120-007-9181-1 (2007). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Scheer H. & Chen M. Extending the limits of natural photosynthesis and implications for technical light harvesting. J. Porphyr. Phthalocya. 17, 1–15, 10.1142/S1088424612300108 (2013). [Google Scholar]

- Tsuchiya T. et al. Artificially produced 7-formyl -chlorophyll d functions as an antenna pigment in the photosystem II isolated from the chlorophyllide a oxygenase-expressing Acaryochloris marina. Biochim. Biophys. Acta 1817, 1285–1291, 10.1016/j.bbabio.2012.02.021 (2012). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Orf G. S. et al. Spectroscopic insights into the decreased efficiency of chlorosomes containing bacteriochlorophyll f. Biochim. Biophys. Acta 1827, 493–501, 10.1016/j.bbabio.2013.01.006 (2013). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Linke M., Lauer A., von Haimberger T., Zacarias A. & Heyne K. Three-Dimensional Orientation of the Qy Electronic Transition Dipole Moment within the Chlorophyll a Molecule Determined by Femtosecond Polarization Resolved VIS Pump−IR Probe Spectroscopy. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 130, 14904–14905, 10.1021/ja804096s (2008). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chen M. & Blankenship R. E. Expanding the solar spectrum used by photosynthesis. Trends Plant Sci. 16, 427–431, 10.1016/j.tplants.2011.03.011 (2011). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ito H. & Tanaka A. Evolution of a divinyl chlorophyll-based photosystem in Prochlorococcus. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 108, 18014–18019, 10.1073/pnas.1107590108 (2011). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Swingley W. D. et al. Niche adaptation and genome expansion in the chlorophyll d-producing cyanobacterium Acaryochloris marina. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 105, 2005–2010, 10.1073/pnas.0709772105 (2008). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Canniffe D. P., Jackson P. J., Hollingshead S., Dickman M. J. & Hunter C. N. Identification of an 8-vinyl reductase involved in bacteriochlorophyll biosynthesis in Rhodobacter sphaeroides and evidence for the existence of a third distinct class of the enzyme. Biochem. J. 450, 397–405, 10.1042/bj20121723 (2013). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Li Y. Q., Scales N., Blankenship R. E., Willows R. D. & Chen M. Extinction coefficient for red-shifted chlorophylls: Chlorophyll d and chlorophyll f. Biochim. Biophys. Acta 1817, 1292–1298, 10.1016/j.bbabio.2012.02.026 (2012). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Porra R. J., Thompson W. A. & Kriedemann P. E. Determination of accurate extinction coefficients and simultaneous-equations for assaying chlorophyll-a and chlorophyll-b extracted with 4 different solvents - verification of the concentration of chlorophyll standards by atomic-absorption spectroscopy. Biochim. Biophys. Acta 975, 384–394, 10.1016/s0005-2728(89)80347-0 (1989). [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Supplementary Information