Abstract

Environmental pollution liability insurance was officially introduced in China only in 2006, as part of new market-based approaches for managing environmental risks. By 2012, trial applications of pollution insurance had been launched in 14 provinces and cities. More than ten insurance companies have entered the pollution insurance market with their own products and contracts. Companies in environmentally sensitive sectors and high-risk industries bought pollution insurance, and a few successful compensation cases have been reported. Still, pollution insurance faces a number of challenges in China. The absence of a national law weakens the legal basis of pollution insurance, and poor technical support stagnates further implementation. Moreover, current pollution insurance products have limited risk coverage, high premium rates, and low loss ratios, which make them fairly unattractive to polluters. Meanwhile, low awareness of environmental and social liabilities leads to limited demand for pollution insurance products by industrial companies. Hence, the pollution insurance market is not yet flourishing in China. To improve this situation, this economic instrument needs stronger backing by the Chinese state.

Electronic supplementary material

The online version of this article (doi:10.1007/s13280-013-0436-0) contains supplementary material, which is available to authorized users.

Keywords: Pollution insurance, China, Environmental risk management, Compensation, Pollution, Insurance companies

Introduction

Environmental pollution liability insurance (or pollution insurance), an outgrowth of comprehensive general liability insurance, developed in the 1960s in industrialized countries, especially in the USA, France, and Germany. Prior to the emergence of pollution insurance, the loss and compensation costs associated with pollution were covered by comprehensive general liability insurance. However, when the number of accidents and the cost of pollution compensation increased dramatically in the 1960s and exceeded the risk coverage of comprehensive general liability insurance policies, pollution liabilities were excluded and needed to be covered by a new type of insurance, pollution insurance (Hollaender and Kaminsky 2000). At the moment, there are two main types of pollution insurance in the world: compulsory pollution insurance and voluntary pollution insurance. The former is widely implemented in the USA and Germany, where companies have been compelled to buy pollution insurance through law and government regulations. The latter is adopted in, for instance, France, and it allows companies to choose whether to buy pollution insurance or not (Bie 2008). Pollution insurance systems in developed countries, such as the USA, Germany, Sweden, France, and the United Kingdom, have become important in solving problems of compensation for environmental damage (Minoli and Bell 2002; Bie and Fan 2007). Hence, some scholars believe that regulation through insurance, or “surrogate regulation” (Abraham 1986), can outperform direct governmental regulation (Shavell 1979; Levmore and Logue 2003), while others are much more critical of the governance powers of the insurance industry beyond state control (Ericson et al. 2003).

Environmental pollution liability insurance is a type of insurance that covers the third-party costs related to pollution, which may include the costs of restoration and clean-up and liability costs for injuries and deaths caused by pollution (Stone 2001). Pollution insurance has as its final object the protection of the insured’s pollution liability toward third parties who have suffered a loss caused by the insured (Chen 2006). As such, it differs from life insurance and general property insurance, where no third-party liabilities are involved. Because liability insurance indemnity is primarily based on compensation paid by the insured to third parties, liability insurance indemnity only exists when the third parties make successful claims. Although some have emphasized the moral hazard that comes with insurance—as insurance can destroy incentives to minimize risk (Shavell 1979; Abraham 1986)—most scholars see strong advantages to pollution insurance as an environmental regulative tool. First, pollution insurance ensures that the victims of pollution can be compensated, even if the company that caused the pollution goes bankrupt. Second, pollution insurance mitigates environmental risks in that it rewards polluters who invest in risk reduction and prevention measures with lower premiums (Freeman and Kunreuther 2003). Third, as an insurance tool, pollution insurance spreads the risks and costs of environmental pollution of one company over a group of polluters, to protect individual—insured—companies from bankruptcy (Freeman and Kunreuther 1997).

Since the 1990s, pollution insurance has expanded from the key industrialized OECD economies to many other countries, including emerging economies such as India (Sankar 1998) and China. In China, the emergence of pollution liability insurance should be understood against two backgrounds: increasingly frequent environmental pollution incidents and risks and experimentation with new market-based approaches to managing environmental risks (He et al. 2012). Since the beginning of the 1980s, China has experienced rapid economic growth, with an average annual GDP increase in more than 9.8 %. With the development of a market economy, China has witnessed dramatic growth in environmental problems related to the abuse of natural resources and poor control of pollution. Entering the twenty-first century, China has been struck by a series of serious environmental disasters and incidents (He et al. 2011), such as the 2005 chemical spill over Songhuajiang River, which increased the awareness and understanding of both the Chinese government and the public about environmental risks. At the same time, the increasing number of pollution incidents and the huge pollution loads put enormous pressure on China’s environmental management system. To further control these increasing environmental risks, new approaches to environmental management, including marked-based instruments, are being tried and implemented in China. Environmental pollution liability insurance is one of these new marked-based approaches recently introduced in China’s still predominantly command-and-control-oriented environmental management system. In 2006, the Chinese government decided to promote environmental insurance strongly, and in 2008, the government started national trial applications of pollution insurance in several cities and provinces. It is expected that a nationwide pollution insurance program will be implemented by 2015 (MEP and IRC 2007). Nevertheless, it is predictable that China will face challenges in applying this new policy tool, for it is clear that the preconditions for developing pollution insurance in China differ considerably from the experience of other countries. First, compared to pollution insurance practices in foreign countries, the third-party environmental liability legal framework in China has not been soundly established. Second, limited law enforcement capacity and low levels of compliance influence the adoption of market-based approaches (Van Rooij et al. 2012). Third, the slow development of environmental litigation in China has limited access to justice.

This study analyzes and reviews the development, implementation, and market construction of pollution insurance in China. More specifically, this study asks whether—6 years after its national introduction—pollution insurance in China offers the same advantages as it has offered in OECD countries. The Chinese government defines pollution insurance as insurance related to compensation for losses suffered by third parties because of environmental pollution accidents. This definition covers insurance for polluting companies and for ships. In this study, however, the emphasis is on insurance for polluting companies (for ships, see Chen 2006). After reviewing the history of pollution insurance in China, the paper continues with a detailed analysis of the governance structure, the stakeholders in pollution insurance, local practices, and the development of the pollution insurance market. The data used in the analysis were collected in 2011 and 2012 and are derived from a variety of sources, including primary data collected during interviews in Beijing, Chongqing, and Jiangsu with (national and provincial) government officials, experts, insurance companies, and insured companies; analysis of governmental publications, policy documents, and media reports; and the analysis of secondary data collected by Chinese scholars. The absence of any systematic statistical data on pollution insurance in China forced us to rely on a variety of primary and secondary data sources to obtain an overview of the current state of pollution insurance in China.

A Short History of Pollution Insurance Promotion in China

Influenced by international environmental conventions, the introduction of pollution insurance in China’s environmental legal framework can be traced back to the 1980s (Table 1). China joined the 1969 International Convention on Civil Liability for Oil Pollution Damage (CLC 69) in 1980, and joined the 1992 International Convention on Civil Liability for Oil Pollution Damage (in short, CLC 92) in 2000. This Convention stipulates in article 7 that “the owner of a ship registered in a Contracting State and carrying more than 2000 tons of oil in bulk as cargo shall be required to maintain insurance or other financial security.” In 1991, China ratified the Basel Convention on the Control of Transboundary Movements of Hazardous Wastes and Their Disposal, but it has not yet signed and ratified the Protocol on Liability and Compensation for Damage Resulting from Transboundary Movements of Hazardous Waste and Their Disposal. This Protocol requires the entities at risk of responsibility for pollution damage caused by transboundary hazardous waste movements and their disposal to obtain insurances, bonds, or other financial guarantees. In 2008, China also joined to the 2001 Protocol of the International Convention on Civil Liability for Bunker Oil Pollution Damage (in short, the Bunker Convention), which requires ships over 1000 tons to maintain insurance or other financial security to cover the liability of the registered owner for pollution damage. Following (discussions on) these conventions, the concept of pollution insurance was introduced to China in the 1980s (Chen 2006). China’s 1982 Marine Environmental Protection Law and China’s 1983 Environmental Protection Regulations on Offshore Oil Exploration and Exploitation included provisions on oil pollution liability insurance for ships. As a member of CLC 92 and the Bunker Convention, China began the application of mandatory guarantees for marine pollution, especially pollution liability insurance, at the start of the twenty-first century.

Table 1.

Overview of major pollution insurance (PI)-related national policies

| Title | Documents cataloga | Issue year | Focus |

|---|---|---|---|

| Marine Environmental Protection Law | SCNPC | 1982 | Article 28: Ships carrying more than 2000 tons of bulk cargo should hold valid “oil pollution damage liability insurance or other financial security certificate” or “credit certificate of civil liability for oil pollution damage” or provide other financial credit guarantees |

| Amended in 1999 | Article 66: Improvement and implementation of the civil liability regime of ship oil pollution compensation. Establishment of ship oil pollution insurance and an oil pollution compensation fund system based on the principle of risk-sharing among ship owners and cargo owners |

||

| Environmental Protection Regulations on Offshore Oil Exploration and Exploitation | The State Council | 1983 | Article 9: The enterprises, institutions and operators engaged in offshore oil exploration and exploitation should purchase pollution liability insurance or provide other financial guarantees |

| Opinions on reforms and development of insurance industries | No. 23 Policy Paper of the State Council | 2006 | Article 5: Development of liability insurance instruments, such as liability insurance for safe production, liability insurance for construction engineering, product liability insurance, public liability insurance, environmental pollution liability insurance, etc. |

| The 11th Five-year Plan for energy-saving and emissions reduction | No. 15 Policy Paper of the State Council | 2007 | Strengthening financial services to the environmental protection domain and the study and establishment of PI systems |

| The Guidelines on Environmental Pollution Liability Insurance | No. 189 Policy Paper of the MEP and the IRC | 2007 | The principle, purpose and work involved in establishment of PI systems. |

| Opinions on Deepening the Reforms of Economic Structure | No. 103 Policy Paper of the GOSC | 2008 | Establishment and improvement of a resources economy and environmental protection: development of trial applications of PI (responsible departments: NDPC, MOF, MEP, etc.) |

| Circular on work arrangement of energy-saving and emissions reduction in 2009 | No. 48 Policy Paper of the GOSC | 2009 | Develop PI trial applications for sewage treatment projects |

| Tort Liability Law | SCNPCC | 2009 | Chapter 8: Environmental Pollution Liability Identification of environmental pollution liabilities and compensation requirements |

| Regulations on preventing vessel pollution to marine environments | No. 561 Decree of the State Council | 2009 | Article 53: The owners of ships navigating in Chinese waters shall maintain vessel oil pollution liability insurance or other financial guarantees |

| Regulations on Taihu Lake Basin | No. 604 Decree of the State Counci | 2010 | Article 51: Encourage companies responsible for water pollution in Taihu Lake Basin to obtain PI |

| Implementation of rules on civil liability insurance for vessel-induced oil pollution damage | No. 3 Decree of the Ministry of Transport | 2010 | Implementation of rules that mandate civil liability insurance for vessels navigating in Chinese sea areas |

| Guidelines on enhancing dioxin pollution prevention | No. 123 Policy Paper of MEP, MFA, NDRC, MST, MIIT, MOF, MHURD, DOC, GAQSIQ | 2010 | Improvement of economic policies on environmental protection. Promotion of PI in dioxin-discharging enterprises involving high environmental risk |

| The 12th Five-year Plan for energy-saving and emissions reduction | No. 26 Policy Paper of the State Council | 2011 | Enterprises responsible for heavy metal pollution in key areas should obtain PI |

| Opinions on enhancing the key work of environmental protection | No. 35 Policy Paper of the State Council | 2011 | Improvement of PI systems and development of trial applications of compulsory PI |

| Safety Regulations on Dangerous Chemicals | No. 591 Decree of the State Counci | 2011 | Article 57: The owners or operators of ships that transport dangerous chemicals through inland rivers should obtain ship pollution liability insurance certificates or financial guarantees |

| Circular on enhancing prevention of pollution by lead-acid storage batteries and lead recovery industries | No. 56 Policy Paper of the MEP | 2011 | Promotion of PI for lead-acid storage batteries and lead recovery industries, based on the introduction of market mechanisms and insurance brokering services. Enterprises in key areas and enterprises with high environmental risks should buy PI. PI will be linked to special funds for heavy metal pollution prevention and control |

GOSC General Office of the State Council, NDRC National Development and Reform Commission, MEP Ministry of Environmental Protection, MHURD Ministry of Housing and Urban–Rural Development, MST Ministry of Science and Technology, MIIT Ministry of Industry and Information Technology, AQSIQ General Administration of Quality Supervision, Inspection and Quarantine, TRC China Insurance Regulatory Commission, MFA Ministry of Foreign Affairs, DOC Department of Commerce, IRC Insurance Regulatory Commission

aThe Chinese legal system mainly consists of four levels: laws promulgated by the National People’s Congress (NPC) or Standing Committees of the National People’s Congress (SCNPC) (the highest legal status), administrative regulations of the State Council, sectoral regulations of ministries and commissions, and local policies and regulations [promulgated by local People’s Congresses (PC) and Standing Committees of People’s Congresses (SCPC)]

Legislation in the 1980s introduced ship pollution insurance in China. However, pollution insurance regulations at that time remained fragmented; pollution insurance was only mentioned in one or two clauses as a choice among financial credit guarantees. Furthermore, during these early years, pollution insurance regulations lacked details, practical measures, and technical support. As a result, early pollution insurance policies did not have much practical meaning and hardly promoted pollution insurance. Moreover, the regulations remained exclusively focused on ships and offshore activities.

Prepared by those initial pollution insurance policies, practical pollution insurance trial applications started only in the 1990s. Pollution insurance in China developed in three stages: the fragmented application stage, the stage of pilot application on a national scale, and the stage of nationwide mandatory application in industries (Fig. 1).

Fig. 1.

Three stages of pollution insurance promotion in China

First Stage: Fragmented Application

In the 1990s, pushed by local Environmental Protection Bureaus (EPBs), pollution insurance was applied in a rather fragmented manner in some cities in China. In 1991, the Environmental Protection Bureau in Dalian cooperated with insurance companies to develop the first pollution insurance products. Later, this style of pollution insurance application expanded to Shenyang, Changchun, Jilin, and some other cities in the northeast of China. However, these first trials of pollution insurance turned out to be failures, as hardly any industry was interested in buy such insurance products. Only about ten polluting companies bought pollution insurance during this period. In Jilin, not even one company bought pollution insurance (Table 2). As the number of insurance contracts decreased year by year, the local trial applications essentially came to a standstill in the middle of the 1990s.

Table 2.

First stage pollution insurance promotion in China (source: Liu 1996)

| City | Start time | Operation of pollution insurance |

|---|---|---|

| Dalian | Oct. 1991 | Time: 4 years (until Oct. 4, 1994) Number of contracts: 15; premium: 2.2 million Yuan Compensation case: one case (125 000 Yuan); loss ratio: 5.7 % |

| Shenyang | Sep. 1993 | Time: 2 years (until Sep. 1995) Number of contracts: 10; premium: 950 000 Yuan Compensation case: no cases; loss ratio: 0 % |

| Changchun | June 1992 | Time: 1 year (until June 1993) Number of contracts: 1; premium: 5000 Yuan Compensation case: no cases; loss ratio: 0 % |

The People’s Insurance Company (Group) of China (PICC) and the Taipingyang Insurance (Group) Company (Taipingyang) participated in the first attempts and designed the primary pollution insurance products, with very limited insurance coverage and high premiums. The loss ratio1 of pollution insurance in the northeastern trial cities turned out to be very low. In Dalian, the loss ratio of pollution insurance in 4 years was 5.7 %, and in Shenyang, the loss ratio of pollution insurance in 2 years was 0 %, which are both much lower than the loss ratios of other insurance products (Liu 1996). As a result, the buyers of pollution insurance saw no benefit to owning pollution insurance products and withdrew from the market. In addition, in the 1990s, the environmental protection system in China was still very much in development, without a framework law on environmental protection and lacking strict law enforcement (Mol and Carter 2006; He et al. 2012). Hence, the external pressure on polluters to buy pollution insurance was low.

Second Stage: Pilot Application on a National Scale

During the second phase of pollution insurance promotion, which started in 2006, pollution insurance was promoted by the national government and was experimentally applied in various local areas. At the same time, a systematic pollution insurance policy framework was constructed (Table 1).

In 2006, the State Council issued Opinions on the reform and development of the insurance industry, announcing the decision to promote environmental pollution liability insurance and marking the official introduction of pollution insurance in China. In 2007, The Guidelines on Environmental Pollution Liability Insurance (The Guidelines) were issued by the Ministry of Environmental Protection (MEP) and the Insurance Regulation Committee (IRC). The Guidelines stated the principles, targets, responsible departments, and work arrangements for developing pollution insurance in China and guided the trial application of pollution insurance in local areas. Furthermore, in other State Council regulations issued between 2007 and 2011, pollution insurance was encouraged and supported as an important economic instrument for energy savings, emissions reduction, and environmental protection (Table 1). Pollution insurance promotion has also been stipulated as a key goal of economic reform since 2008. The 2009 Tort Liability Law defined the liabilities of environmental pollution, clarified that the polluter shall assume the burden of proving that it is not liable in the case of a dispute, and detailed how to address pollution caused by several polluters or third parties. Those provisions founded and advanced the legal basis of environmental litigation and pollution insurance in China. In addition, as a new liability law issued after the trial application of pollution insurance, the Tort Liability Law embodied the governments’ concern about environmental liabilities and stimulated stakeholders to engage in pollution insurance.

At the same time, technical support was steadily being developed by the government. MEP and IRC issued the Environmental Risk Assessment Guide—the Risk Classification Method for the chlor-alkali and sulfuric acid industries in 2010 and 2011. Recommended calculation methods for environmental pollution damage costs were announced in 2011. These methodology guidelines formed part of the technical support structure for pollution insurance. However, technical support for pollution insurance remains weak, as no unified standard for risk assessment and loss compensation has been developed for these industries, and risk assessment methodologies for other industries are still under investigation.

Supported by these national policies, eight provinces and cities (Jiangsu, Hubei, Hunan, Henan, Chongqing, Shenzhen, Ningbo, and Shenyang) had been chosen for pollution insurance trial applications by the end of 2008. Industries dealing with dangerous chemicals, petrochemicals, dangerous waste treatment, landfills, sewage treatment plants, and various industrial parks were selected as the main targets for the pilot programs. Insurance companies also responded quickly to The Guidelines. PICC, the Pingan Insurance (Group) Company of China (Pingan), Taipingyang, and other insurance companies developed pollution insurance products and entered the pollution insurance market. By the end of 2011, the pollution insurance trial application areas had expanded from 8 to 14 provinces. In October 2008, the first case of pollution insurance compensation in a National Pollution Insurance Trial Application occurred in Hunan Province. The Pingan Insurance Company paid 11 000 Yuan to 120 households affected by the spillover of hydrogen chloride gas from a chemical factory. This illustrates that pollution insurance has already had an on effect environmental pollution compensation in China.

Third Stage: Nationwide Mandatory Application in Industries

The pollution insurance policies issued in 2010, 2011, and early 2012 illustrate a trend toward the development of mandatory pollution insurance. First, influenced by international conventions, the compulsory vessel pollution insurance market developed rapidly with the issuing of Implementation Rules on Civil Liability Insurance for Vessel-induced Oil Pollution Damage in 2010, which required all ships carrying oil substances and ships larger than 1000 tons carrying non-oil substances to maintain insurance or other financial guarantees. In 2011, the State Council issued Opinions on Enhancing the Key Work of Environmental Protection, in which it announced the development of trial applications of compulsory pollution insurance. At the same time, the State Council issued Safety Regulations on Dangerous Chemicals which declares that ships transporting dangerous chemicals over inland rivers have to obtain ship pollution liability insurance. The MEP Circular on Enhancing Pollution Prevention in Lead-acid Storage Batteries and Lead Recovery Industries indicates that enterprises in key areas and enterprises with high environmental risks have to buy pollution insurance (MEP 2011). These all seem to indicate the start of a new, third stage in the development of pollution insurance in China: a nationwide mandatory application of pollution insurance in industries with high environmental risks. Implementation of such a nationwide mandatory system, however, is only starting.

Governance Structure and Stakeholders

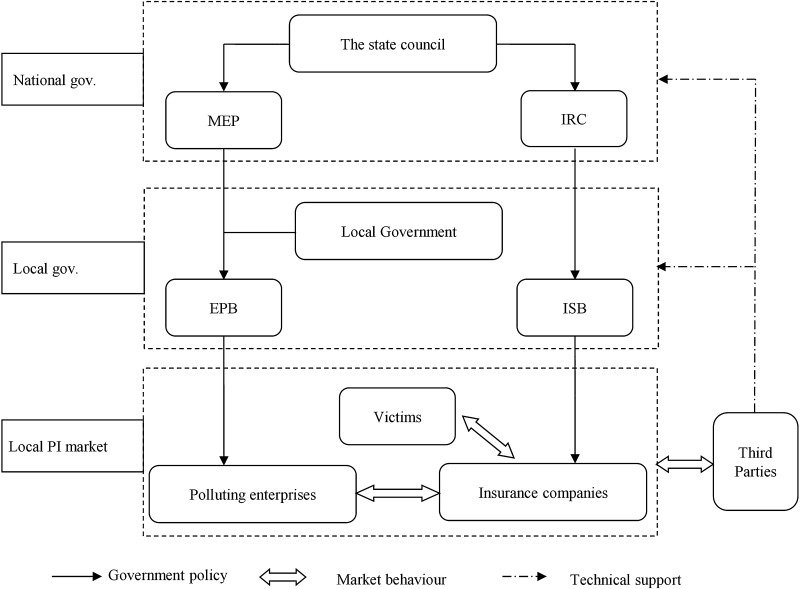

Currently, (2013), five categories of stakeholders are involved in the Chinese pollution insurance system: the government, insurance companies, polluting companies, victims, and third parties. Based on an analysis of pollution insurance policies and local practices, Fig. 2 graphs the relationships between these stakeholders and the governance structure of pollution insurance application.

Fig. 2.

Governance structure and stakeholders in pollution insurance trial applications

According to The Guidelines (2007), which is the most authoritative policy on pollution insurance promotion, the key principle in pollution insurance promotion in China is “pushed by the government, operated by the market.” Hence, the government is identified as the main promoter of pollution insurance, through pollution insurance legislation, institutional construction and financial incentives. Under the direction of the State Council, MEP and IRC are the departments authorized to take charge of pollution insurance (trial) applications by issuing the main policies for pollution insurance implementation and directing local government departments in pollution insurance application practices. Given the lack of experience, the national government has given local governments considerable freedom to experiment with pollution insurance application to learn from variations in pollution insurance trials. In addition, the national government (especially MEP and IRC) pushes technical support by entrusting research institutes to study environmental risk assessment standards and pollution insurance policy making and issues guidelines on environmental risk assessment in high-risk industries. In 2011, MEP also started working on environmental pollution damage identification and assessment and issued recommended methods for calculating environmental pollution damage costs.

Local governments, especially the Environmental Protection Bureaus (EPB) and Insurance Supervision Bureaus (ISB), are the main agents responsible for experimenting with and promoting pollution insurance in local areas. In working with pollution insurance, the Environmental Protection Bureaus are directed by the Ministry of Environmental Protection and local municipal governments, while the Insurance Supervision Bureaus are directly guided by IRC. As stated in The Guidelines, the two departments are required to cooperate with each other to promote, develop, and implement local pollution insurance legislation, motivate polluting companies to become involved in (and thus buy) pollution insurance, and develop standards for damage compensation. In addition, EPBs should strengthen environmental supervision and inspection of polluting companies and prepare them for adequate prevention and management of environmental accidents. ISB supervises the development of the pollution insurance market and guarantees that all pollution insurance contracts are executed correctly. In practice, EPBs have administrative control over polluters and can compel them to buy pollution insurance. ISB’s power in the insurance market is only related to supervision and inspection of insurance companies; it “encourages” insurance companies to develop pollution insurance products. As a result, it has been proven that EPBs play a more important role in local pollution insurance promotion, by putting polluters in contact with insurance companies and by pushing polluting companies to buy pollution insurance. Various local governmental agencies have developed pollution insurance application policies based on their local contexts, enabling various pollution insurance designs to be tested to benefit the construction of the national pollution insurance system (Table S1 in the Electronic Supplementary Material).

Insurance companies and polluting companies are the key stakeholders in the pollution insurance market. At present, pollution insurance trading between these stakeholders takes place under the administration of local governments. Insurance companies submit their pollution insurance products to IRC to receive a permit to enter the pollution insurance market and then further develop their business under the supervision of ISB. The polluting companies are pushed by the EPBs to buy pollution insurance from insurance companies. Insurance companies conduct risk assessments of polluting companies before they provide insurance services. In some provinces, insurance companies collaborate with the local EPB in conducting a risk assessment of a polluting company and in negotiating pollution insurance contracts.

In the past, victims—individual citizens, communities, or organizations negatively influenced by environmental pollution accidents—could only turn to the local EPB or the court to seek financial compensation of pollution damage. Even with the assistance of local EPBs, many victims were not compensated fairly due to the lack of clarity in identifying the responsible polluters, bankruptcies of the polluters, and close ties between polluters and governmental agencies. Although Chinese law authorizes lawsuits to seek compensation for victims who have suffered from environmental pollution, it is difficult to amass sufficient proof to prevail in environmental compensation cases in China, because the plaintiffs typically lack the scientific knowledge, expertise and resources needed to meet their burden of proof in environmental disputes. Even when plaintiffs prevail in court, they may encounter further obstacles when seeking to collect compensation awards (Goldman 2006), when, for example, the polluter goes bankrupt or disappears before paying. With the establishment of pollution insurance policies and a pollution insurance market, victims can more easily obtain reasonable compensation through pollution insurance. However, to date, victims (or their representatives, such as NGOs) have not been involved and have not had any influence on policy making related to pollution insurance.

Third parties, such as insurance brokers, academic research institutes focused on pollution insurance, and insurance assessors, function more or less independently from governmental agencies, insurance companies, polluting companies, and victims. At present, the involvement of such third parties in the development of the pollution insurance system is limited, as there are very few state-certified parties for risk assessment and loss identification and very few experienced insurance brokers. Only research institutes have been quite active in assisting governmental agencies and insurance companies in policy making and technical standard setting on pollution insurance. For example, the environmental industry association helped MEP in the development of environmental risk assessment guidelines and developed the environmental risk classification methods for the chlor-alkali and sulfuric acid industries. Risk classification methods for other heavy-polluting industries, such as crude lead smelting, are still in development. The Policy Research Centre for Environment and Economy of the Ministry of Environmental Protection (PRCEE) is the main (but hardly independent) third party that studies pollution insurance policies and drafts policy proposals. In local trial applications, research institutes have also assisted EPBs and insurance companies in standard setting. For instance, expert teams have investigated polluting companies and assessed environmental risks in Chongqing and Jiangsu to help insurance companies in drafting pollution insurance contracts.

Local Practices in Pollution Insurance Promotion in China

In summary, China’s pollution insurance governance system lacks knowledge and experience, as it was only officially introduced in China in 2006. National pollution insurance policies have been relatively general, without a systematic legal basis and without detailed implementation measures, which has left considerable space for local pollution insurance practices. Hence, over the past few years, the central government has encouraged and pushed local pollution insurance trial applications to experiment with different designs for pollution insurance products and contracts.

By the end of 2011, 14 provinces and cities (Jiangsu, Hubei, Hunan, Chongqing, Shenzhen, Ningbo, Shenyang, Hebei, Henan, Yunnan, Shanghai, Sichuan, Fujian, and Shanxi) had started applying pollution insurance trials. Some of the local governments in these pilot areas (i.e., Shanghai, Hebei, Henan, Liaoning, Chongqing, and Jiangsu) have launched local legislation on pollution insurance and have begun to explore and establish pollution insurance policies. Most of these provinces and cities have issued implementation guidelines, announced principles, and setup work arrangements with industries (Table S1 in the Electronic Supplementary Material). The Regulations on Pollution Prevention and Control of Hazardous Waste (SCPC 2008), approved by the Standing Committee of the People’s Congress (SCPC) of Liaoning Province in 2008, was the first local legislation on pollution insurance in China. Article 8 states that it “supports and encourages insurance companies to develop pollution liability insurance for hazardous waste; supports and encourages companies that produce, collect, store, transport, use, and dispose hazardous waste to take hazardous waste pollution liability insurance.” Other local pieces of legislation have similar provisions, encouraging pollution insurance along with pollution control and environmental management. In most trial application areas, EPBs and ISBs have proven to be the main departments responsible for pollution insurance promotion and issuance of local guidelines. Pollution insurance trials in most localities are focused on environmentally sensitive areas and industries with high environmental risks, such as shipping, chemicals, and hazardous waste treatment.

Reflecting international developments, two types of local pollution insurance systems have developed in China. Voluntary pollution insurance systems are practiced in Shanghai, Hebei, and Chongqing, where governmental policies “encourage” polluting companies to buy pollution insurance. Mandatory pollution insurance systems are present in Hunan and Jiangsu, among other provinces, where companies in specific sectors and of specific sizes have to buy pollution insurance (Table S1 in the Electronic Supplementary Material) so that they will not be confronted with punitive measures. For instance, the city of Wuxi in Jiangsu Province combines pollution insurance with administrative measures. Companies that do not buy pollution insurance in Wuxi cannot get their environmental impact assessments approved for new construction and expansion projects and will be downgraded one level in their company behavior assessments. In addition, their noncompliance with environmental regulations will be communicated to banks, who will limit their credit support. Influenced by the 2011 national policy developments concerning mandatory pollution insurance, more and more provinces and cities are issuing local policies for compulsory pollution insurance. For example, the city of Shenzhen in Guangdong Province declared in 2011 that all enterprises engaged in lead-acid battery storage and lead recovery had to buy pollution insurance.

Local governments also explore preferential measures and financial incentives for local pollution insurance policies. The city of Wuhan in Hubei Province prepared a government fund of 2 million Yuan (approximately 314 000 US$) to provide a 50 % premium subsidy for pollution-insured companies. In the city of Zhuzhou in Hunan Province, 50 % of the premium costs of insured companies are used to offset some pollution charges. In Hunan Province, companies that did not have an environmental incident last year received a premium discount of 5 % and companies that had no environmental incident in the past 2 years received a discount of 10 % on their pollution insurance renewal, paid for by the government.

The Market of Pollution Insurance

Since 2008, the market for pollution insurance products and contracts in China has developed gradually.

Insurance Companies and Pollution Insurance Products

Since the introduction of pollution insurance policies in China, quite a number of insurance companies have responded to the requirements and requests of governments and developed pollution insurance products. In 2010, 146 insurance companies, including 58 property insurance companies, existed in China (Ma et al. 2012). More than 10 insurance companies have entered the pollution insurance market in China, with pollution insurance products approved by IRC (PRCEE 2011). PICC, Pingan, and the Huatai Insurance Group Company (Huatai) are the leading companies in the Chinese pollution insurance market, having captured significant shares of the market. Until the end of 2010, Pingan had the largest market share, servicing the pollution insurance policies of 350 companies and underwriting a loss of over 3.5 thousand million Yuan. In addition, PICC, Pingan, Taipingyang, and Yongan have formed so-called coinsurance organizations to share the risk of pollution insurance and have together developed the entity Coastal and Inland Ship Pollution Liability Insurance, which is now the most popular provider of ship pollution insurance in China (Tables 3, 4). In addition to these major insurance companies, other insurance companies exist that do not yet have national approval for pollution insurance products but that have already designed products and started pollution insurance businesses in local areas. These local operations, which do not yet have national approval, have become an important part of the Chinese pollution insurance market.

Table 3.

Main pollution insurance (PI) products of major insurance companies in China (PRCEE 2011)

| Insurance company | PI products |

|---|---|

| The People’s Insurance Company (Group) of China (PICC) | Environmental pollution liability insurance |

| Additional moral damage liability insurance to PI | |

| Additional natural disaster liability insurance to PI | |

| Additional specific provisions on environmental pollution liability accidents | |

| Additional theft and robbery liability insurance to PI | |

| Additional specific provisions on excess of loss cover to PI | |

| Additional own site clean-up cost insurance to PI | |

| Ship oil pollution liability insurance | |

| Ping An Insurance (Group) Company of China (Pingan) | Environmental pollution liability insurance |

| Additional in-place clean-up cost insurance to PI | |

| Additional moral damage liability insurance to PI | |

| Additional natural disaster liability insurance to PI | |

| Additional employee casualty liability insurance to PI | |

| Additional out place clean-up cost insurance to PI | |

| Additional specific provisions on territorial scope of coverage to PI | |

| Additional specific provisions on loss discovery time to PI | |

| Huatai Insurance Group Company (Huatai) | Location pollution liability insurance |

| Location pollution liability insurance (accidental insurance) | |

| Ancheng Property & Casualty Insurance Company (Ancheng) | Environmental pollution liability insurance |

| In-place clean-up cost insurance | |

| Moral damage liability insurance | |

| Chang An Property and Liability Insurance Ltd. (Changan) | Environmental pollution liability insurance |

| Coinsurance of PICC, Pingan, Taipingyang, and Yongan insurance companies | Coastal and inland ship pollution liability insurance (2008) |

Table 4.

Pollution insurance (PI) market in different regions

| Provinces | Started time | PI market | PI Products | Insurance companies |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Jiangsu | 2008 | Until June 2011: Insured companies: 207 Total premium of 8 million Yuan Coverage: 420 million Yuan Insured ships: 1500 Total premium of 20 million Yuan Coverage: 3000 million Yuan |

Premium rate: 2 % Coverage limitation: 3 levels started from 1 million Yuan |

PICC, Pingan, Taipingyang, Taibao, Yongan, Changan, Dadi, Dubang, coinsurance organizations |

| Hunan | 2008 | Until Oct. 2010: Insured companies: 240 Coverage: 280 million Yuan Compensation: 1.42 million Yuan Until Oct. 2011: Insured companies: 393 Coverage: 195.49 million Yuan |

Pingan | |

| Yunnan (Kunming) | 2009 | Until Sep. 2010: Insured companies: 45 |

Pingan, PICC | |

| Zhejiang | 2009 | Until Nov. 2011: Insured companies: 59 Premium: 2.15 million Yuan Coverage: above 40 million Yuan Compensation: 691.8 thousand Yuan (in Ningbo) |

Premium rate: 5.4 % | Pingan, PICC, coinsurance organization (PICC, Taibao, Pingan, Dadi, Huatai) |

| Chongqing | 2009 | Until July 2011: Insured companies: 3 Premium: 76 000 Yuan Coverage: 3 million Yuan |

Premium rate: 2.5 % | Coinsurance organization (PICC, Pingan, Ancheng, Huatai) |

| Guangdong (Shenzhen) | 2009 | Until Dec. 2010: Insured companies: 8 Premium: 0.5 million Yuan Coverage: 16 million Yuan |

Premium rate: 3.1 % | PICC, Pingan, Taibao, Samsung fire |

| Liaoning | Shenyang and Dalian started PI in 2008 PI in the whole province started in 2010 |

PICC, Pingan | ||

| Shanghai | 2009 | Until March 2009: PI for dangerous chemicals: Premium: 4.18 million Yuan Coverage: 1561 million Yuan |

Premium rate: 0.26 % Coverage limitation for dangerous chemicals: 5 levels from 3 million Yuan to 50 million Yuan |

Huatai, Anxing, Taibao |

| Hubei | 2009 | Until Dec. 2009: Insured companies: 8 Coverage: 25 million Yuan |

PICC, Taipingyang, Pingan | |

| Hebei (Baoding) | 2010 | Until Nov. 2011: Insured companies: 15 |

PICC, coinsurance organizations (8 insurance companies) | |

| Henan | 2010 | Until Feb. 2012: Insured companies: 1 Premium: 0.15 million Yuan Coverage: 2 million Yuan |

Premium rate: 7.5 % | |

| Sichuan | 2010 | Until June 2011: Insured companies: 4 |

Coverage limitation: 3 million Yuan Compensation for personal injury: 200 thousand Yuan for each person |

PICC, Pingan |

| Fujian | 2011 | 9 insurance companies filed PI products in ISB in Fujian | ||

| Shanxi | 2011 | Until Oct. 2011: Insured companies: 82 |

Data sources official reports on pollution insurance by local governments; media and internet reporting on pollution insurance; pollution insurance trial application investigation carried out by the Policy Research Centre for Environment and Economy, Ministry of Environmental Protection (PRCEE), and Policy Research Office in IRC in 2009 and 2012

According to incomplete national statistics (Gao 2010), the number of environmental insurance policies (including ship insurance policies) increased dramatically from 2008 to 2009 (Fig. 3). In 2009, approximately 1700 ships and companies bought pollution insurance products in China, 1000 more than in 2008. The total amount of the premiums jumped from 12.5 million Yuan in 2008 to 43.8 million Yuan (approximately 6.9 million US$) in 2009, with a total loss coverage of 5.87 thousand million Yuan (approximately 922 million US$). Although more recent data are unavailable, these facts indicate the relatively rapid development of the pollution insurance market in China. However, the total premium income of pollution insurance in 2009 only accounted for 0.015 % of the total premium income of the insurance industry (PRCEE 2011), and the number of insured assets was just a drop in the ocean compared with the assets that could potentially be insured against pollution liability in China. Hence, there is considerable room for further development of the pollution insurance market in China.

Fig. 3.

Developments in pollution insurance in China, 2008 to 2009 (source Gao 2010) (National statistical data on pollution insurance development in China is limited. Only data from 2008 and 2009 are available; no data from 2010 and 2011 have been published)

At present, most of the pollution insurance products in China are the result of examples from foreign pollution insurance businesses, with fewer variations. A comparison of the popular pollution insurance contracts offered by PICC, Pingan, and Ancheng indicates that the basic pollution insurance products available in China are quite similar and generally only cover direct losses caused by environmental pollution incidents, including personal injuries or death, direct property loss of third parties caused by environmental incidents, necessary clean-up or pollution control costs associated with eliminating or mitigating pollution damage caused by the incident at sites not owned by the polluter, and necessary and reasonable “legal fees” for arbitration and litigation after the accident. Losses caused by accumulated environmental pollution and ecological losses associated with environmental incidents are not covered by most pollution policies in China. This limited coverage of risks and costs does not satisfy the needs of industrial companies and is believed to contribute to the limited demand for pollution insurance (Liu and Chik 2012). However, from the insurers’ perspective, the costs related to gradual pollution and ecological losses come with large uncertainties, and their inclusion may increase the premiums significantly. Furthermore, high premiums for pollution insurance products may not be acceptable to most of the insured companies. Thus, at present, disagreements exist between industrial companies and insurance companies about the risk coverage of pollution insurance.

Moreover, all pollution insurance products in China have a maximum coverage limit. Due to the lack of pollution data and advanced risk assessment models in China’s pollution insurance market, risk assessment and classification are primarily based on simple indicators and come with large uncertainty. For instance, Pingan assesses the environmental risks of polluting companies based on industrial categories, enterprise size, location, and the company’s compliance with environmental regulations, but it gives limited consideration to actual pollutant emissions and production processes. As a result of these uncertainties in risk assessment, insurance companies set rather high premium rates. According to Lin (2010), the premium rates for pollution insurance in China are between 2 and 8 %, which is much higher than the premium rates of other insurance products and higher than the premium rates of pollution insurance in Western OECD countries. In addition, Chinese insurance companies group polluters with poor environmental management performance, especially companies with poor records in environmental pollution incidents, and charge them higher premiums.

Local Pollution Insurance Markets

At present, there are no official national statistical data on pollution insurance trial applications. Therefore, for this analysis, market development data were collected from local and regional media reports and governmental overviews, which vary considerably from region to region. Because the data sources differ among the localities, the data are incomplete and have different time horizons. Hence, only a rough picture is available of the pollution insurance market in distinct local regions (Table 4). Until early 2012, pollution insurance contracts between polluters and insurance companies existed in all 14 trial regions. In addition, at least in Hunan, Yunnan, Ningbo, and Hubei, pollution insurance compensation was paid following pollution incidents caused by insured companies.

The pollution market has developed in an unequal manner in these trial regions. Jiangsu and Hunan started very early in developing a pollution insurance market, and had, by 2012, a relatively mature market with a significant amount of money being paid in premiums. In contrast, the pollution insurance market in Chongqing, Yunnan, and Shenzhen, among other regions, developed rather slowly. These provinces and cities started developing a pollution insurance market in 2009 by making implementation plans, but by 2012, the pollution insurance markets in these regions were still only developed to a preliminary degree, with a small number of insured companies and a limited amount of money being paid in premiums. Jiangsu and Hunan are also typical cases of regions with mandatory pollution insurance systems, while Chongqing and Shenzhen are typical of regions with voluntary pollution insurance promotion systems. In Hebei, Sichuan, Shanxi, and Fujian, the pollution insurance market started to develop later, and market construction and information provisioning is just beginning.

With the pollution market still very much in development, the loss ratio in China is very low. Again, no systematic data are available, but our research on cases, companies and news reports indicates that compensation cases associated with pollution incidents are usually small in scale and involve low levels of compensation. In 2009, a petrochemical corporation in Hunan Province leaked benzene into the drainage system, causing a major fire and explosion, which damaged houses, fish ponds and farmlands. After the incident, the government investigated the cause of the incident and assessed the loss. The Pingan Insurance Company checked the government report and paid a total of 550 000 Yuan (approximately 86 500 US$) to the farmers involved. As far as we could determine, this is the largest compensation case reported in China. Our investigation of pollution compensation reports indicates that pollution insurance can indeed help victims to obtain compensation, but the number of pollution insurance compensation cases to date have been limited and the compensation payments have been relatively small.

Regardless of these empirical findings, insurance companies do fear the high-consequence risks of environmental incidents in China and the potentially large compensation amounts involved. Coinsurance, whereby several insurance companies combine forces to share special risk, is becoming more popular in pollution insurance. In Suzhou, Jiangsu, Chongqing, Hebei, and Zhejiang, coinsurance organizations have been established by several insurance companies to decrease the pollution insurance risk covered by each insurance company. Coinsurance enables insurance companies to lower their premium rates and make pollution insurance products more attractive in China. This is necessary, because the normal premium rates in China are between 2 and 5.4 % (Table 4), which is somewhat lower than those found by Lin (2010) but still too high to attract polluting companies. Henan Province has an exceptionally high premium rate (7.5 %), but this rate might not be representative, because it is based on only one case.

In our interviews and data analysis, a limited demand for pollution insurance products by industrial companies was observed. In addition to premium rates, several context factors explain this limited demand. Traditionally in China, the government pays for severe environmental pollution damage. There is also limited access to environmental litigation justice, which limits industrial company awareness of environmental and social liabilities. Meanwhile, due to the weak enforcement of laws (Kostka and Mol 2013), the penalty for not buying pollution insurance is very low for industrial enterprises. As a result, companies will not spend money on pollution insurance.

In addition, our inventory and analysis did not confirm that pollution insurance was perceived by polluting companies as a mechanism for preventing bankruptcy. Most polluting companies in environmentally sensitive sectors are rather doubtful of, or more often, unaware of the need to buy pollution insurance. Many of the main polluters are state-owned enterprises (SOEs), who can logically count on the support of the government and hence have little incentive to protect themselves against liability by buying insurance. Some large-scale industrial companies consider their solid economic basis sufficient to address compensation for environmental incidents and see pollution insurance as an unnecessary cost. Many small and medium-sized industrial companies fail to see a sufficient benefit to this new economic burden and complain that (mandatory) pollution insurance promotion in some provinces reduces the competitiveness of companies in these provinces.

Our investigations could not confirm whether pollution insurance has stimulated risk reduction and prevention by industrial companies. The no-claim discounts reported for Jiangsu, for example, could have such an influence, but more data on company measures would be needed to substantiate this.

According to the law of large numbers in insurance, the greater the number of companies that are insured is, the smaller the variance of the risk is and the smaller the effective risk faced by the insurer is (Priest 1987). Insurance companies need a large and stable insurance market with large numbers of insured companies to make more precise determinations of the reserves needed to compensate for losses incurred and to develop good insurance services with low premiums. Because only a few companies have bought pollution insurance in most provinces and cities in China, the risks of environmental incidents cannot be widely shared with others, and insurance companies cannot offer attractive services and low premiums to polluters. Moreover, because of the low level of awareness of environmental and social liabilities, as well as the low costs associated with violating pollution insurance requirements, industrial enterprises have limited demand for pollution insurance. This vicious cycle blocks the development of a mature pollution insurance market. Only government regulations and policies on mandatory pollution insurance, premium subsidies and stringent environmental law enforcement can break this cycle and push polluters to buy pollution insurance products. We indeed see that in regions with mandatory pollution insurance policies, such as Jiangsu and Hunan, the number of insured companies is relatively large and premiums are relatively low.

Conclusions

The introduction of pollution insurance in China is part of the wider development of environmental management innovations, whereby China’s conventional command-and-control approach is being supplemented by market-oriented models. As a mature economic approach to environmental risk management in Western countries, pollution insurance offers several benefits: (1) it spreads the risks and costs of environmental pollution for one company over a group of polluters, thus protecting individual companies from bankruptcy; (2) it ensures that pollution victims can be compensated; (3) it mitigates environmental risks in that it rewards polluters with lower premiums in exchange for investing in risk reduction and prevention measures. While significant advances have been made since its introduction in 2006, and several large insurance companies have developed and implemented pollution insurance products and contracts, contemporary pollution insurance in China cannot yet fulfill these three functions. The reported number of incidents for which victims and losses have actually been compensated is very low, as has been the financial compensation itself. This, and the fact that coverage costs are generally quite low, makes it difficult to assess the effect of pollution insurance in protecting polluters from bankruptcy. Although some insurance companies do charge polluters with poor environmental records higher premiums (which may encourage them to invest in environmental pollution control), the actual number of companies that have bought pollution insurance is much too low to speak of a substantial effect on risk reduction.

One of the main causes for these shortcomings is the poor dissemination of pollution insurance products among polluting companies, which is related to relatively high premiums, low compensation payments, and little need felt by polluting companies to buy such insurance. If the pollution insurance market is to mature and fulfill its promises, strong state intervention—much more than just subsidies to lower premiums for polluting companies—is necessary. A pollution insurance market only seems to develop when there is some type of mandatory insurance policy, as local developments in Jiangsu and Hunan prove. Mandatory pollution insurance implementation in environmentally sensitive industries seems to be taken up in China, as in 2011, the State Council announced the further development of mandatory pollution insurance tries. Promoting environmental liability insurance at the same time will ensure that victims of pollution damage are compensated in the case of an accident. Stronger enforcement of environmental regulations by EPBs is also necessary, including higher compensation charges to make pollution insurance economically rational. The government and third parties also need to support the further development of pollution insurance by developing standards for compensation, loss identification, and risk assessment methods. Lastly, a systematic national policy or law on pollution insurance needs to be developed to give local (trial) applications a strong legal basis.

This all means that in order for pollution insurance to mature in China, this economic instrument needs further backing and support by the central government. The conditions that made pollution insurance such a success in many OECD countries are not yet present in China, and the central Chinese government has the most important role to play in creating a different, more favorable context.

Electronic supplementary material

Acknowledgments

This work was supported by the Netherlands Royal Academy of Arts and Sciences and the Chinese Academy of Sciences (Project No. 10CDP030).

Biographies

Yan Feng

is a PhD candidate at Wageningen University. Sponsored by Cooperative Project of Netherlands Royal Academy of Arts and Sciences and CAS: Environmental Risk and Emergency Management in China, Yan focused on the innovation in environmental risk management in China and took environmental pollution liability insurance as one target for her studies. Yan Feng received her B.Sc. in Environmental Sciences and Engineering from Tsinghua University of China, and M.Sc. in Environmental economics and management from Research Center for Eco-Environmental Sciences, Chinese Academy of Sciences.

Arthur P. J. Mol

was trained in environmental studies (M.Sc.) and sociology (Ph.D.). He is now director of the Wageningen School of Social Sciences, and professor of environmental policy at Renmin University, China. As a substantial contributor to the Ecology Modernization Theory, He concerns with researches in environmental management, Environmental Policy, Nature Management, Politics, Public Administration, and environmental Sociology.

Yonglong Lu

is the Chair and Research Professor, Regional Ecological Risk Assessment and Environmental Management Group at Research Center for Eco-Environmental Sciences (RCEES), Chinese Academy of Sciences (CAS); Co-Director, RCEES, CAS; Fellow of TWAS (the Academy of Sciences for the Developing World); President of Scientific Committee on Problems of the Environment (SCOPE); Member of ICSU (International Council for Sciences) Committee on Scientific Planning and Review; Science Advisory Board Member, International Union for Conservation of Nature (IUCN); Member of International Resource Panel, United Nations Environment Program (UNEP). As an active environmental scientist, he has published more than 170 papers in the peer reviewed journals. His research areas include human and ecological health impacts and risk assessment of persistent toxic substances, urban ecological planning and assessment, energy and environmental impacts, environmental management and policy, sustainable watershed management, environmental emergency response, and environmental technology innovation and diffusion policies.

Guizhen He

is an assistant researcher in the Environmental Management and Policy Group at Research Center for Eco-Environmental Sciences, CAS. She has a combined education background with environmental engineering (B.Sc.), hydrobiology (M.Sc.) and environmental economics and management (PhD), and published papers on environmental auditing, environmental assessment, government performance evaluation, and policy analysis.

C.S.A. van Koppen

worked at Utrecht University as a professor of environmental education from 2004 to 2009, and now works in Wageningen university as an associate professor of environmental policy. He was trained in environmental sciences (M.Sc.) and environmental sociology (Ph.D.). His work concentrates in environmental policy studies, especially in nature conservation policy and social learning.

Footnotes

Loss ratio: in insurance, the loss ratio is the ratio of total losses incurred (paid and reserved) in claims, plus adjustment expenses, divided by the total earned premiums.

Contributor Information

Yan Feng, Email: fengy02@gmail.com.

Arthur P. J. Mol, Email: arthur.mol@wur.nl

Yonglong Lu, Phone: +86-1062917903, FAX: +86-1062918177, Email: yllu@rcees.ac.cn.

Guizhen He, Email: heguizh@yahoo.com.cn.

C. S. A. van Koppen, Email: kris.vankoppen@wur.nl

References

- Abraham KS. Distributing risk: Insurance, legal theory, and public policy. New Haven: Yale University Press; 1986. [Google Scholar]

- Bie, T. 2008. Environmental pollution liability insurance in foreign countries. Qiu Shi. Retrieved March 3, 2008, from http://www.bizjournals.com/philadelphia/stories/2001/11/05/focus4.html (in Chinese).

- Bie, T., and X. Fan. 2007. Comparative study on the international environmental pollution liability insurance systems. Insurance Studies 89–92 (in Chinese).

- Chen P. A study on the types of liability of the insurer for oil pollution and that of the party liable. In: Faure MG, Hu J, editors. Prevention and compensation of marine pollution damage, recent developments in Europe, China and the US. Alphen: Kluwer; 2006. pp. 241–262. [Google Scholar]

- Ericson, R.V., A. Doyle, and D. Barry. 2003. Insurance as governance. Toronto: University of Toronto Press.

- Freeman PK, Kunreuther H. Managing environmental risk through insurance. Dordrecht: Kluwer Academic Publishers; 1997. [Google Scholar]

- Freeman PK, Kunreuther H. Managing environmental risk through insurance. In: Henk Folmer TT, editor. Yearbook of environmental and resource economics. Glos: Edward Elgar Publishing Limited; 2003. pp. 159–189. [Google Scholar]

- Gao, J. 2010. Environmental pollution liability insurance have made positive progress in China. China Environment News. Retrieved September 20, 2010, from http://www.cenews.com.cn/xwzx/zhxw/ybyw/201009/t20100919_664056.html (in Chinese).

- Goldman P. Public interest environmental litigation in China: Lessons learned from the U.S. Experience. Vermont Journal of Environmental Law. 2006;8:251–278. [Google Scholar]

- He G, Zhang L, Lu Y, Mol APJ. Managing major chemical accidents in China: Towards effective risk information. Journal of Hazardous Materials. 2011;187:171–181. doi: 10.1016/j.jhazmat.2011.01.017. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- He G, Lu Y, Mol APJ, Beckers T. Changes and challenges of China’s environmental management. Environmental Development. 2012;3:25–38. doi: 10.1016/j.envdev.2012.05.005. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Hollaender K, Kaminsky MA. The past, present, and future of environmental insurance including a case study of MTBE litigation. Environmental Forensics. 2000;12:205–211. doi: 10.1006/enfo.2000.0021. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Kostka G, Mol APJ. Implementation and participation in China’s local environmental politics: Challenges and innovations. Journal of Environmental Policy & Planning. 2013;15:3–16. doi: 10.1080/1523908X.2013.763629. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Levmore, S., and K.D. Logue. 2003. Insuring against terrorism—and crime. Michigan Law and Economics Research Paper No. 03-005; U of Chicago, Public Law Working Paper No. 47; U Chicago Law & Econ, Olin Working Paper No. 189. Available at SSRN: http://ssrn.com/abstract=414144 or http://dx.doi.org/10.2139/ssrn.414144.

- Lin, Q. 2010. The role of government in environmental pollution liability insurance. Popular Business 320 (in Chinese).

- Liu, Y. 1996. The states and prospect of pollution liability insurance in China. China Environment Management 16–18 (in Chinese).

- Liu C, Chik ARB. Reasons for insufficient demand of environmental liability insurance in China: A case study of Baoding, Hebei Province. Asian Social Science. 2012;8:201–204. [Google Scholar]

- Ma, Y., S. Xue, P. Bai, X. Huo, and X. Bian. 2012. Investment analysis report on insurance industry in China (2012–2016). China Investment Consultant Company (in Chinese).

- MEP. 2011. Circular on enhancing pollution prevention in lead-acid storage batteries and lead recovery industries. MEP.

- MEP and IRC. 2007. The guidelines on environmental pollution liability insurance. MEP.

- Minoli DM, Bell JNB. Insurance as an alternative environmental regulator: findings from a retrospective pollution claims survey. Business Strategy and the Environment. 2002;12:107–117. doi: 10.1002/bse.350. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Mol APJ, Carter NT. China’s environmental governance in transition. Environmental Politics. 2006;15:149–170. doi: 10.1080/09644010600562765. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- PRCEE. 2011. The development report of environmental pollution liability insurance in China. PRCEE.

- Priest GL. The current insurance crisis and modern Tort law. The Yale Law Journal. 1987;96:1521–1590. doi: 10.2307/796494. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Sankar, U. 1998. Laws and institutions relating to environmental protection in India. In The role of law and legal institutions in Asian economic development. Rotterdam: Erasmus University.

- SCPC, L. 2008. Regulations on pollution prevention and control of hazardous waste. SCPC.

- Shavell S. On moral hazard and insurance. The Quarterly Journal of Economics. 1979;93:541–562. doi: 10.2307/1884469. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Stone, A. 2001. Pollution insurance growing in popularity. Philadelphia Business Journal. Retrieved Nov 5, 2001, from http://www.bizjournals.com/philadelphia/stories/2001/11/05/focus4.html.

- Van Rooij B, Wainwright AL, Wu Y, Zhang YA. The compensation trap: The limits of community-based pollution regulation in China. Pace Environmental Law Review. 2012;29:701–745. [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.