Abstract

Introduction

Pancreatic trauma occurs in approximately 4% of all patients sustaining abdominal injuries. The pancreas has an intimate relationship with the major upper abdominal vessels, and there is significant morbidity and mortality associated with severe pancreatic injury. Immediate resuscitation and investigations are essential to delineate the nature of the injury, and to plan further management. If main pancreatic duct injuries are identified, specialised input from a tertiary hepatopancreaticobiliary (HPB) team is advised.

Methods

A comprehensive online literature search was performed using PubMed. Relevant articles from international journals were selected. The search terms used were: ‘pancreatic trauma’, ‘pancreatic duct injury’, ‘radiology AND pancreas injury’, ‘diagnosis of pancreatic trauma’, and ‘management AND surgery’. Articles that were not published in English were excluded. All articles used were selected on relevance to this review and read by both authors.

Results

Pancreatic trauma is rare and associated with injury to other upper abdominal viscera. Patients present with non-specific abdominal findings and serum amylase is of little use in diagnosis. Computed tomography is effective in diagnosing pancreatic injury but not duct disruption, which is most easily seen on endoscopic retrograde cholangiopancreaticography or operative pancreatography. If pancreatic injury is suspected, inspection of the entire pancreas and duodenum is required to ensure full evaluation at laparotomy. The operative management of pancreatic injury depends on the grade of injury found at laparotomy. The most important prognostic factor is main duct disruption and, if found, reconstructive options should be determined by an experienced HPB surgeon.

Conclusions

The diagnosis of pancreatic trauma requires a high index of suspicion and detailed imaging studies. Grading pancreatic injury is important to guide operative management. The most important prognostic factor is pancreatic duct disruption and in these cases, experienced HPB surgeons should be involved. Complications following pancreatic trauma are common and the majority can be managed without further surgery.

Keywords: Pancreatic trauma, Pancreatic duct injury, Grades of pancreatic injury, Operative approaches in pancreatic trauma

Pancreatic trauma is uncommon and occurs in only around 4% of all patients sustaining abdominal injuries. 1 There is significant morbidity and mortality associated with severe pancreatic injury 2 owing to its intimate relationship with the major upper abdominal vessels. Immediate resuscitation and investigations are essential to delineate the nature of the injury, and to plan further management. 3,4 If pancreatic injuries are identified, specialised input from a tertiary hepatopancreaticobiliary (HPB) team is advised. This review discusses the aetiology, presentation, investigation and management options for pancreatic trauma.

A comprehensive online literature search was performed using PubMed. Relevant articles from international journals were selected. The search terms used were: ‘pancreatic trauma’,‘pancreatic duct injury’, ‘radiology AND pancreas injury’, ‘diagnosis of pancreatic trauma’, and ‘management AND surgery’. Articles that were not published in English were excluded. All articles used were selected on relevance to this review and read by both authors.

The pancreas is closely related to the duodenum, the posterior aspect of the stomach, the common bile duct and the spleen, and it overlies the inferior vena cava, the right renal vessels, the left renal vein, the superior mesenteric vessels and the splenic vessels. Such close proximity to multiple vital structures accounts for the fact that isolated pancreatic trauma is extremely rare. Associated intra-abdominal injuries occur in over 90% of cases 3 and the most commonly injured are the stomach, the liver, the small bowel, the duodenum, major vessels and the diaphragm. 5 Blunt trauma most commonly occurs following a high energy impact such as a motor vehicle accident but we have also seen pancreatic injuries following go-karting, horse riding and football.

The acceleration–deceleration nature of blunt trauma causes the pancreas to be crushed against the first and second lumbar vertebrae. 2 The body of the pancreas is most commonly injured in blunt trauma. 6 Penetrating trauma (eg stab wound or gunshot wound)is rising in incidence and accounts for 70% of all traumatic pancreas injuries. 7 Damage to the main pancreatic duct occurs in 15% of cases and is crucial to ascertain before or during laparotomy as it necessitates pancreatic reconstruction by an experienced HPB surgeon. 8 In patients with pancreatic trauma who have survived the initial 48–72 hours of their abdominal injury (and concomitant injuries, if any, to other organs), leakage of corrosive pancreatic juice from a disrupted duct and the consequent peripancreatic inflammation and sepsis is the major cause of morbidity and mortality.

Presentation

In patients with a penetrating wound in the upper abdomen or epigastric bruising, a high index of suspicion is required to diagnose a possible pancreatic injury. History in the trauma setting is often difficult and physical examination is generally non-specific but pancreatic injury should always be considered in patients with epigastric tenderness. 9 In cases of high-impact trauma with multiple injuries, the patient is likely to have sustained significant trauma to adjacent viscera (eg liver, spleen)that requires immediate evaluation and life-saving management prior to considering the possibility of pancreatic trauma. Grey Turner’s sign and Cullen’s sign may be present although these are not sensitive markers of pancreatic trauma. The axiom that upper abdominal pain, raised white cell count and raised serum amylase accompany pancreatic trauma is inaccurate as these features are often absent. 10

Investigations

Laboratory tests are of little value in the early diagnosis of pancreatic trauma. Serum amylase has been studied extensively. An increase in serum amylase is time dependent and was found to be elevated in all patients with pancreatic injury after three hours. 11 However, there is conflicting evidence, with another study showing that over 30% of patients with severe pancreatic trauma have serum amylase levels within normal parameters. 12,13

Helical multislice computed tomography (CT) is the non-invasive imaging modality of choice in patients with abdominal trauma. Triple phase CT in haemodynamically stable patients has been shown to have a sensitivity and specificity as high as 80% 14 in detecting pancreatic injury (Fig 1). There is no pancreatic parenchymal phase (35–40 second delay) in a trauma CT protocol, 15 which may reduce sensitivity. It has been demonstrated that 20–40% of pancreatic injuries are missed if CT is performed within 12 hours of injury 12,14 owing to surrounding oedema, obscured pancreatic fracture planes and closely opposed pancreatic segments. 16 If repeat imaging demonstrates a delayed pancreatic injury, specialist HPB opinion should be sought to allow further imaging and surgical planning to begin. Features on CT that are characteristic of pancreatic injury include fracture or laceration of the pancreas, intrapancreatic haematoma and fluid separating the splenic vein from the pancreas. 17

Figure 1.

Computed tomography demonstrating transection through the pancreatic neck (arrow) and disruption of the head of the pancreas. The patient presented following a road traffic accident.

Pancreatic duct injury is poorly characterised on CT and it is often detected during laparotomy. Laceration less than 50% of the diameter of the pancreas usually indicates no ductal injury. 18 If ductal injury is suspected, magnetic resonance cholangiopancreaticography or endoscopic retrograde cholangiopancreaticography (ERCP) can be used for further assessment 19 although these modalities have not been assessed formally. ERCP can be used preoperatively but patients are rarely stable enough to tolerate the procedure and often require intraoperative assessment during laparotomy. 4

Grading pancreatic injury

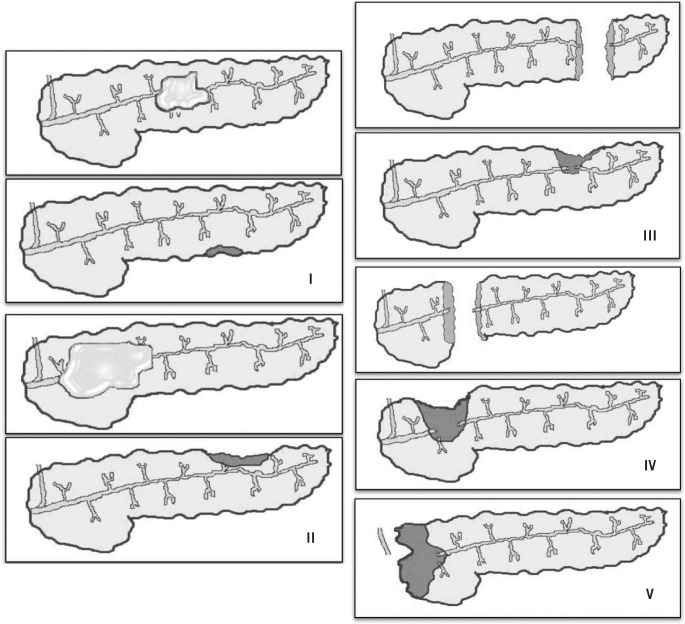

The most recent grading system for pancreatic injuries was outlined by the American Association for the Surgery of Trauma. 20 It is illustrated in Fig 2.

Figure 2.

Grading the severity of pancreatic injury: grade I – minor contusion or laceration with no duct injury, grade II – major contusion or laceration with no duct injury, grade III – transection or major laceration with duct disruption in distal pancreas, grade IV – transection of proximal pancreas or major laceration with associated injury to the ampulla, grade V – Massive disruption of the pancreatic head

Operative assessment

Patients with intra-abdominal trauma require immediate investigation and resuscitation. Resuscitation should be guided by local and Advanced Trauma Life Support® protocols, 21 and if investigations unveil proven pancreatic and associated organ injury, exploratory laparotomy is required. 22 Following haemorrhage control and prevention of further contamination, a thorough and systematic examination of the pancreas is essential. However, in patients requiring immediate laparotomy, the operating surgeon is often not experienced in HPB surgery and may proceed with a damage limitation, lifesaving approach rather than definitive treatment. In these cases, the second, reconstructive laparotomy should be performed by an experienced HPB surgeon in a tertiary centre.

Features suggestive of pancreatic trauma include retroperitoneal bile staining, fluid in the lesser sac, haematoma overlying the pancreas and fat saponification. 23 Entry into the lesser sac allows visualisation of the anterior surface of the pancreas. Mobilisation of the hepatic flexure, proximal transverse colon 22 and duodenum allows the head, uncinate process and posterior aspect of the duodenum to be evaluated. Mobilisation of the spleen and splenic flexure allows access to the pancreatic tail. Dissection through the retropancreatic space lifts the posterior surface of the pancreas off the splenic vessels. These manoeuvres allow extensive inspection of both the anterior and posterior aspects of the pancreas.

The major prognostic factor following pancreatic trauma is main pancreatic duct injury. 24,25 Various methods of pancreatography have been described, based on the degree of trauma confronted at laparotomy. Cannulation of the cystic duct or common bile duct (CBD)is a relatively straightforward technique and is useful for assessing the distal CBD, proximal pancreatic duct and ampullary intergrity. 22,23 Cannulation of the pancreatic duct can be performed by concomitant ERCP although this may not be possible in cases of combined major pancreaticoduodenal trauma. The ampulla can be cannulated under direct vision following duodenotomy. 26 However, this is technically demanding. In grade III injury with distal transection, the pancreatic duct may be identified and cannulated through the distal end. When the pancreatic head is compromised in grade IV injuries, the duct can be cannulated and passed proximally to assess the proximal duct and ampullary integrity. Duct disruption is demonstrated by extravasation of contrast media under fluoroscopy.

Operative management

Grade I and II injuries constitute the majority of pancreatic trauma. 3,27 Drainage with any required local debridement is most commonly performed. 28 Any capsular injury should not be primarily sutured as this can lead to necrosis. 2 The only documented prospective randomised trial comparing closed suction drainage with sump drainage demonstrated reduced incidence of pancreas related septic complications with a closed suction system. 28 If the drain amylase is below the serum value after 48 hours, the drain can be removed. 3

Grade III injuries generally require distal pancreatectomy and splenectomy with drainage. In children, effort should be made to preserve the spleen if possible 29 because of the potential for overwhelming postsplenectomy infection. Given the difficulty in dissecting the pancreatic tail and possible bleeding from tributaries, it is advocated that concurrent splenectomy is performed in adults to minimise operating time in unstable patients. 2 There have been no prospective randomised trials comparing stapling with non-absorbable sutures for closing the body of the pancreas. 30,31 In cases of a clean grade III transection, the pancreas can be conserved. A jejunal Roux loop can be anastomosed to the body of the pancreas and the distal part of the head of the pancreas can be sutured closed.

The management of grade IV and grade V injury is complex, requiring the input of experienced HPB surgeons. If the duodenum is not compromised and the ampulla is intact, the most straightforward option is washout and drainage 32 although pancreatic head resection may result in fewer subsequent operations and complications. In cases of massive pancreatic head disruption, pancreaticoduodenectomy may be required. Grade V pancreatic injury usually only occurs in patients with multiple other injuries who are haemodynamically unstable and mortality rates are high. 3,33

If pancreaticoduodenectomy is unavoidable, it can be done as a two-stage procedure. 34,35 Following haemostasis, the stomach, jejunum and pancreatic stump are stapled off and the CBD is drained. The patient is then stabilised on the intensive care unit (ICU) and a second laparotomy is performed after 48 hours for reconstruction. 36 No studies have evaluated the safety of pancreaticogastrostomy versus pancreaticojejunostomy in the trauma setting. It should only be performed by an experienced HPB surgeon in a tertiary unit with adequate ICU and radiological support.

Postoperative care and complications

Trauma patients require counselling following major surgery. They often have no recollection of the events that preceded admission and require careful explanation of the operative measures taken. Pancreatic resection can lead to endocrine and exocrine insufficiency, and patients may require pancreatic enzymes to aid digestion and treatment of subsequent diabetes.

Around a third of patients with pancreatic trauma develop complications. The most common complication is pancreatic fistula with rates of between 10% and 18%. 4,37 The majority of these leaks settle with conservative management, providing adequate drains are inserted in the operating theatre. Octreotide was shown to decrease pancreatic fluid output in trauma patients in a prospective non-randomised trial. 38

Patients with persisting fistulas can be treated with ERCP and stenting. 4,22 In cases not amenable to endoscopic stenting, further laparotomy and reconstruction may be required. Post-traumatic pancreatitis can occur and most commonly requires supportive therapy. 2 Abscess formation occurs in 10–25% of cases 39 and is generally amenable to radiological drainage. Secondary haemorrhage is a serious complication that can lead to rapid deterioration. 3 Radiological embolisation is the first line treatment 22 but if no bleeding vessel is identified, relaparotomy is required. Pancreatic pseudocyst is a late complication and outcomes depend on duct disruption. If the duct is intact, percutaneous drainage is sufficient. 40 Duct disruption requires endoscopic stenting in the majority of cases.

Conclusions

The diagnosis of pancreatic trauma requires a high index of suspicion and detailed imaging studies. Grading pancreatic injury is important to guide operative management. The most important prognostic factor is pancreatic duct disruption and, once ductal disruption has been confirmed, early surgical intervention should be considered and specialist HPB surgeons should be involved.

References

- 1.Asensio JA, Demetriades D, Hanpeter Det al.Management of pancreatic injuries. Curr Probl Surg 1999; 36: 325–419 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Boffard KD, Brooks AJ. Pancreatic trauma – injuries to the pancreas and pancreatic duct. Eur J Surg 2000; 166: 4–12 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Vasquez JC, Coimbra R, Hoyt DB, Fortlage D. Management of penetrating pancreatic trauma: an 11-year experience of a level-1 trauma center. Injury 2001; 32: 753–759 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Chinnery GE, Krige JE, Kotze UKet al.Surgical management and outcome of civilian gunshot injuries to the pancreas. Br J Surg 2011; 99: 140–148 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Asensio JA, Petrone P, Roldán Get al.Pancreatic and duodenal injuries. Complex and lethal. Scand J Surg 2002; 91: 81–86 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Madiba TE, Mokoena TR. Favourable prognosis after surgical drainage of gunshot, stab or blunt trauma of the pancreas. Br J Surg 1995; 82: 1,236–1,239 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Young PR, Meredith JW, Baker CCet al.Pancreatic injuries resulting from penetrating trauma: a multi-institution review. Am Surg 1988; 64: 838–843 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Graham JM, Mattox KL, Jordan GL. Traumatic injuries of the pancreas. Am J Surg 1978; 136: 744–748 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Asensio JA, Forno W. Duodenal Injuries. In: Demetriades D, Asensio JA, eds.Trauma Management. Austin, TX: Landes Bioscience; 2000. pp354–360 [Google Scholar]

- 10.Meredith JW, Trunkey DD. CT scanning in acute abdominal injuries. Surg Clin North Am 1988; 68: 255–268 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Takishima T, Sugimoto K, Hirata Met al.Serum amylase level on admission in the diagnosis of blunt injury to the pancreas: its significance and limitations. Ann Surg 1997; 226: 70–76 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Wisner DH, Wold RL, Frey CF. Diagnosis and treatment of pancreatic injuries. An analysis of management principles. Arch Surg 1990; 125: 1,109–1,113 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Cirillo RL, Koniaris LG. Detecting blunt pancreatic injuries. J Gastrointest Surg 2002; 6: 587–598 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Bradley EL,Young PR, Chang MCet al.Diagnosis and initial management of blunt pancreatic trauma: guidelines from a multiinstitutional review. Ann Surg 1998; 227: 861–869 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Linsenmaier U, Wirth S, Reiser M, Körner M. Diagnosis and classification of pancreatic and duodenal injuries in emergency radiology. Radiographics 2008; 28: 1,591–1,602 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Venkatesh SK, Wan JM. CT of blunt pancreatic trauma: a pictorial essay. Eur J Radiol 2008; 67: 311–320 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Lane MJ, Mindelzun RE, Sandhu JSet al.CT diagnosis of blunt pancreatic trauma: importance of detecting fluid between the pancreas and the splenic vein. Am J Roentgenol 1994; 163: 833–835 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Wong YC, Wang LJ, Lin BCet al.CT grading of blunt pancreatic injuries: prediction of ductal disruption and surgical correlation. J Comput Assist Tomogr 1997; 21: 246–250 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Wright MJ, Stanski C. Blunt pancreatic trauma: a difficult injury. South Med J 2000; 93: 383–385 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Moore EE, Cogbill TH, Malangoni MHet al.Organ injury scaling. II. Pancreas, duodenum, small bowel, colon, and rectum. J Trauma 1990; 30: 1,427–1,429 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Carmont MR. The Advanced Trauma Life Support course: a history of its development and review of related literature. Postgrad Med J 2005; 81: 87–91 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Degiannis E, Glapa M, Loukogeorgakis SP, Smith MD. Management of pancreatic trauma. Injury 2008; 39: 21–29 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Oláh A, Issekutz A, Haulik L, Makay R. Pancreatic transaction from blunt abdominal trauma: early versus delayed diagnosis and surgical management. Dig Surg 2003; 20: 408–414 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Degiannis E, Levy RD, Velmahos GCet al.Gunshot injuries of the head of the pancreas: conservative approach. World J Surg 1996; 20: 68–71 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Lewis G, Krige JE, Bornman PC, Terblanche J. Traumatic pancreatic pseudocysts. Br J Surg 1993; 80: 89–93 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Hayward SR, Lucas CE, Sugawa C, Ledgerwood AM. Emergent endoscopic retrograde cholangiopancreatography. A highly specific test for acute pancreatic trauma. Arch Surg 1989; 124: 745–746 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Young PR, Meredith JW, Baker CCet al.Pancreatic injuries resulting from penetrating trauma: a multi-institution review. Am Surg 1998; 64: 838–843 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Fabian TC, Kudsk KA, Croce MAet al.Superiority of closed suction drainage for pancreatic trauma. Ann Surg 1990; 211: 724–728 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Stringer MD. Pancreatitis and pancreatic trauma. Semin Pediatr Surg 2005; 14: 239–246 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Andersen DK, Bolman RM, Moylan JA. Management of penetrating pancreatic injuries: subtotal pancreatectomy using the Auto Suture stapler. J Trauma 1980; 20: 347–349 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Degiannis E, Levy RD, Potokr Tet al.Distal pancreatectomy for gunshot injuries of the distal pancreas. Br J Surg 1995; 82: 1,240–1,242 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Patton JH, Lyden SP, Croce MAet al.Pancreatic trauma: a simplified management guideline. J Trauma 1997; 43: 234–239 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Wynn M, Hill DM, Miller DRet al.Management of pancreatic and duodenal trauma. Am J Surg 1985; 150: 327–332 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Koniaris LG. Role of pancreatectomy after severe pancreaticoduodenal trauma. J Am Coll Surg 2004; 198: 677–678 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Koniaris LG, Mandal AK, Genuit T, Cameron JL. Two-stage trauma pancreaticoduodenectomy: delay facilitates anastomotic reconstruction. J Gastrointest Surg 2000; 4: 366–369 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Carillo C, Folger RJ, Shaftan GW. Delayed gastrointestinal reconstruction following massive abdominal trauma. J Trauma 1993; 34: 233–235 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Akhrass R, Yaffe MB, Brandt CPet al.Pancreatic trauma: a ten-year multi-institutional experience. Am Surg 1997; 63: 598–604 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Amirata E, Livingston DH, Elcavage J. Octreotide acetate decreases pancreatic complications after pancreatic trauma. Am J Surg 1994; 168: 345–357 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Jurkovich GJ. Duodenum and Pancreas. In: Mattox KL, Feliciano DV, Moore EE, eds.Trauma. Norwalk, CT: Appleton & Lange; 2005. pp709–734 [Google Scholar]

- 40.Lin BC, Chen RJ, Fang JFet al.Management of blunt major pancreatic injury. J Trauma 2004; 56: 774–778 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]