Abstract

Solitary fibrous tumours are infrequent neoplasms based in the pleura that are predominantly benign with malignant pathology and behaviour described in 10–36% of cases. Extrathoracic solitary fibrous tumours (ESFTs) have been considered separately to their intrathoracic counterparts and comprise a third of all solitary fibrous tumours. The extrathoracic location was identified as an adverse prognostic factor for local recurrence but not for metastatic disease. So far, there have not been any reports of solitary fibrous tumours demonstrating caval infiltration. We present a case of a benign ESFT infiltrating into the perirenal inferior vena cava. Together with extrauterine leiomyomas, ESFTs should also be considered as a differential diagnosis for the rare benign lesions invading the inferior vena cava.

Keywords: Inferior vena cava, Solitary fibrous tumour, Retroperitoneal neoplasm

Solitary fibrous tumours (SFTs) are an infrequent but distinct neoplasm that generally arise from submesothelial connective soft tissue in the pleura. SFTs are rarely recognised in extrathoracic sites 1 and their clinicopathological features have only been reported in a few small case series in recent years. 2 Extrathoracic SFTs (ESFTs) have been reported to have a higher rate of aggressive behaviour than those described classically. 3 Those tumours with atypical or malignant features seen on histological examination have poorer prognosis. They are recommended to be managed and followed up in the same manner as other high grade soft tissue tumours.

To date, there have been no known reports of ESFTs involving the inferior vena cava (IVC). We present an interesting case of a histologically benign ESFT arising from the IVC, which was preoperatively diagnosed as a leiomyosarcoma of the IVC.

Case history

A 43-year-old Indonesian man, a hepatitis B carrier, was referred to our institution for an incidental finding of a right abdominal mass on routine ultrasonography of the hepatobiliary system as part of the screening protocol for hepatitis B carriers. He was completely asymptomatic. Computed tomography (CT) of the abdomen and pelvis demonstrated a heterogeneously enhancing right anterior retroperitoneal mass. This was inseparable from the wall of the IVC for a length of 4cm as demonstrated on CT (Fig 1). This mass was abutting against the posterior aspect of the second part of the duodenum and the inferior aspect of segment 6 of the liver but not invading into the liver. The differential diagnoses were that of a leiomyosarcoma with an extravascular component or that of a neuroendocrine tumour such as a paraganglioma. There was no evidence of pulmonary or hepatic metastases.

Figure 1.

Axial computed tomography of the abdomen of tumour invading inferior vena cava

The phaeochromocytoma screen was negative. The patient was assessed to be surgically fit and underwent an exploratory laparotomy with excision of the right retroperitoneal tumour that was arising from the suprarenal IVC (Fig 2). The IVC was partially side clamped to allow excision of the tumour en bloc with a cuff of the IVC wall (Figs 2 and 3). The cavotomy was repaired primarily with 5/0 Prolene® (Ethicon, Somerville, NJ, US) sutures. He was discharged after eight days with no complications.

Figure 2.

Coronal computed tomography of the abdomen

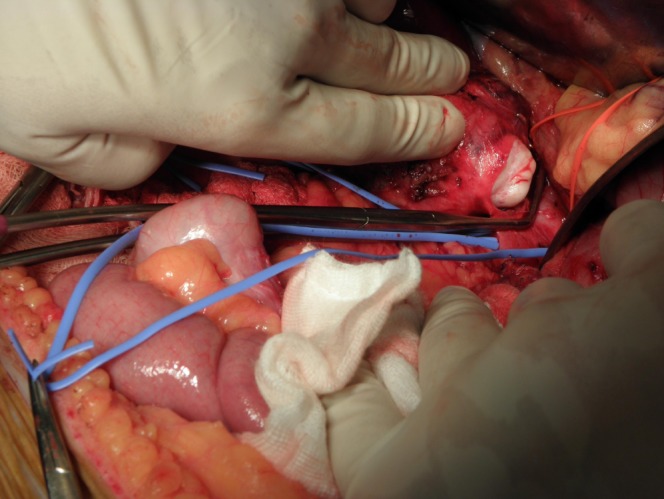

Figure 3.

Blue vessel loop identifying the right renal vein and inferior vena cava

The histology of the mass demonstrated a well circumscribed spindle cell tumour with variable cellularity (Fig 4). The cellular areas showed patternless sheets of spindle cells surrounding thin wall staghorn vessels. Strands of collagen deposition could be seen interspersed between the spindle cells in these cellular areas. The hypocellular areas showed relative paucity of spindle cells with surrounding loose myxoid stroma. The tumour cells had bland ovoid vesicular nuclei, inconspicuous nucleoli and indistinct cell borders. A few scattered mitoses (1–2 per 10 high powered fields) were seen in the tumour. Immunohistochemical stains were performed. The lesional spindle cells stained positively for CD34 and Bcl-2. There was focal positive staining for S100 protein. They were negative for anion exchange proteins 1 and 3, h-caldesmon and desmin. There were no areas of necrosis or other histological features of malignancy in this SFT. The portal lymph node that was excised was also negative for malignancy.

Figure 4.

Satinsky clamp partially applied along the longitudinal axis of the inferior vena cava and the tumour widely excised with vena cava wall

Discussion

SFTs are an uncommon neoplasm of mesenchymal origin. They was first recognised by Klemperer and Rabin as a distinctive pleural lesion in 1931. 4 Over the last decade, more than 100 ESFTs have been reported, located in the meninges, orbit, upper respiratory tract, salivary glands, thyroid, peritoneum, liver, retroperitoneum, adrenal gland, kidney, spermatic cord, urinary bladder and prostate spinal cord, periosteum, and soft tissue mainly in the head and neck. 2,5–15

They may show aggressive behavior with local recurrence or metastasis and well established histological criteria exist to predict clinically aggressive behaviour. 15 Vallat-Decouvelaere et al suggested histological features such as nuclear atypia, areas of increased cellularity, necrosis and 4 or more mitoses per 10hpf as being predictive of clinically aggressive behaviour of the tumour, and found local or distant relapse in those cases in 80%. 5 Gold et al reported that a primary tumour size of more than 10cm and positive surgical resection margins are positively correlated with unfavourable clinical outcome. 2

Figure 5.

Whitish surface of the extrathoracic solitary fibrous tumour seen on opening the inferior vena cava

In the studies of Gold et al and Vallat-Decouvelaere et al, local recurrence occurred in 6.7% and 4.3% and metastasis in 5.3% and 5.4% respectively. 2,5 Local recurrence or metastasis occurs most often within the first two years while the sites of distant metastasis are most commonly seen in the lungs, bone and liver. 5 Occasionally, histologically benign SFTs behave in a clinically malignant fashion a long period of time after the excision of the original tumour. 2

A more recent large series of ESFTs with a long follow-up period showed that they behave clinically in a manner similar to high grade soft tissue sarcomas. 3 They have relatively high rates of local recurrence (16.2%) and metastatic spread (8.9%) as well as a poor overall prognosis (5-year survival rate 40%).

Although the presence of malignant histopathological features remains an indicator of a poor clinical outcome for these cases, no ESFT should currently be considered definitely benign, even in the absence of such features. It should be emphasised that histological appearance does not correlate perfectly with the clinical behaviour in SFTs. Appropriate surgical excision and an extended follow-up period is therefore necessary to identify and manage the relatively high rate of recurrent disease. 3

We believe that this is the first report of an ESFT arising from the IVC, which was preoperatively diagnosed as a leiomyosarcoma, a more common clinical condition that arises from the IVC. In this case, the preoperative preparation and operative strategic planning was of paramount importance. The IVC invasion was recognised prior to surgery and CT revealed that less than half the circumference was involved.

Figure 6.

Histology of solitary fibrous tumour (haematoxylin and eosin stain)

Figure 7.

Spindle cells in tumour showing strong positive immunohistochemical staining for CD34 (400x magnification)

Fortunately, in our patient, there was no need to resect the IVC. It was recognised that the lumen of the IVC may be compromised and so the inferior mesenteric vein was harvested prior to the resection of the tumour for the purpose of vein patching the IVC defect following excision. Kuehnl et al performed a retrospective study of their results in vena cava resection for a series of 35 patients. 16 They analysed perioperative complications and factors affecting long-term survival, concluding that patients with tumour invasion in the superior vena cava or IVC should be considered for surgical resection as survival is significantly better in those with complete resection, and morbidity and mortality rates are acceptable. This was therefore the approach we undertook for our patient.

References

- 1.Takizawa I, Saito T, Kitamura Yet al Primary solitary fibrous tumor (SFT) in the retroperitoneum. Urol Oncol 2008; 26: 254–259. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Gold JS, Antonescu CR, Hadju Cet al Clinicopathologic correlates of solitary fibrous tumors. Cancer 2002; 94: 1,057–1,068. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Cranshaw IM, Gikas PD, Fisher Cet al Clinical outcomes of extra-thoracic solitary fibrous tumours. Eur J Surg Oncol 2009; 35: 994–998. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Klemperer P, Rabin CB. Primary neoplasms of the pleura: a report of five cases. Arch Pathol 1931; 11: 385–412. [Google Scholar]

- 5.Vallat-Decouvelaere AV, Dry SM, Fletcher CD. Atypical and malignant solitary fibrous tumors in extrathoracic locations: evidence of their comparability to intra-thoracic tumors. Am J Surg Pathol 1998; 22: 1,501–1,511. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Nielsen GP, O’Connell JX, Dickersin GR, Rosenberg AE. Solitary fibrous tumor of soft tissue: a report of 15 cases, including 5 malignant examples with light microscopic, immunohistochemical, and ultrastructural data. Mod Pathol 1997; 10: 1,028–1,037. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Wagner S, Greco F, Hamza Aet al Retroperitoneal malignant solitary fibrous tumor of the small pelvis causing recurrent hypoglycemia by secretion of insulin-like growth factor 2. Eur Urol 2009; 55: 739–742. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Zeitler DM, Kanowitz SJ, Har-El G. Malignant solitary fibrous tumor of the nasal cavity. Skull Base 2007; 17: 239–246. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Muñoz E, Prat A, Adamo Bet al A rare case of malignant solitary fibrous tumor of the spinal cord. Spine 2008; 33: E397–399. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Korkolis DP, Apostolaki K, Aggeli Cet al Solitary fibrous tumor of the liver expressing CD34 and vimentin: a case report. World J Gastroenterol 2008; 14: 6,261–6,264. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Martorell M, Pérez-Vallés A, Gozalbo Fet al Solitary fibrous tumor of the thigh with epithelioid features: a case report. Diagn Pathol 2007; 2: 19. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Daigeler A, Lehnhardt M, Langer Set al Clinicopathological findings in a case series of extrathoracic solitary fibrous tumors of soft tissues. BMC Surg 2006; 6: 10. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Hu Y, Mahar TJ, Hicks DGet al Malignant solitary fibrous tumor: report of 3 cases with unusual features. Appl Immunohistochem Mol Morphol 2009; 17: 451–457. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Miyamoto H, Molena DA, Schoeniger LO, Xu H. Solitary fibrous tumor of the pancreas: a case report. Int J Surg Pathol 2007; 15: 311–314. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Gengler C, Guillou L. Solitary fibrous tumour and haemangiopericytoma: evolution of a concept. Histopathology 2006; 48: 63–74. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Kuehnl A, Schmidt M, Hornung HMet al Resection of malignant tumors invading the vena cava: perioperative complications and long-term follow-up. J Vasc Surg 2007; 46: 533–540. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]