Background: Metal ions at LIMBS and MIDAS are essential for integrin-ligand interactions.

Results: MD simulations showed strikingly different and functionally relevant conformations of LIMBS in αVβ3 and αIIbβ3.

Conclusion: The α-subunit regulates metal ion coordination at LIMBS and hence function of β3 integrins.

Significance: The results reveal a new mechanism of integrin regulation by the α-subunit.

Keywords: Cell Adhesion, Cell Biology, Integrin, Molecular Dynamics, Signal Transduction

Abstract

The aspartate in the prototypical integrin-binding motif Arg-Gly-Asp binds the integrin βA domain of the β-subunit through a divalent cation at the metal ion-dependent adhesion site (MIDAS). An auxiliary metal ion at a ligand-associated metal ion-binding site (LIMBS) stabilizes the metal ion at MIDAS. LIMBS contacts distinct residues in the α-subunits of the two β3 integrins αIIbβ3 and αVβ3, but a potential role of this interaction on stability of the metal ion at LIMBS in β3 integrins has not been explored. Equilibrium molecular dynamics simulations of fully hydrated β3 integrin ectodomains revealed strikingly different conformations of LIMBS in unliganded αIIbβ3 versus αVβ3, the result of stronger interactions of LIMBS with αV, which reduce stability of the LIMBS metal ion in αVβ3. Replacing the αIIb-LIMBS interface residue Phe191 in αIIb (equivalent to Trp179 in αV) with Trp strengthened this interface and destabilized the metal ion at LIMBS in αIIbβ3; a Trp179 to Phe mutation in αV produced the opposite but weaker effect. Consistently, an F191/W substitution in cellular αIIbβ3 and a W179/F substitution in αVβ3 reduced and increased, respectively, the apparent affinity of Mn2+ to the integrin. These findings offer an explanation for the variable occupancy of the metal ion at LIMBS in αVβ3 structures in the absence of ligand and provide new insights into the mechanisms of integrin regulation.

Introduction

Integrins are αβ heterodimeric cell adhesion receptors that mediate divalent cation-dependent cell-matrix and cell-cell adhesion during morphogenesis, as well as the maintenance of tissues and organs in adult life. 18 α- and 8 β-subunits assemble into 24 integrin receptors in mammals. Integrins regulate fundamental aspects of cell behavior, including migration, adhesion, differentiation, growth, and survival, by communicating bidirectional signals between the extracellular environment and the intracellular cytoskeleton (1).

Integrins are unusual receptors as they do not engage physiologic ligand unless activated. This property allows patrolling blood leukocytes and platelets, for example, to circulate without aggregating or interacting with the vessel walls. Inappropriate activation of integrins contributes to the pathogenesis of common diseases including heart attacks, stroke, and cancer growth and metastasis. Thus understanding how these receptors are regulated is important in promoting health and treating disease (2).

The integrin heterodimer comprises a head segment that sits on top of two leg segments each spanning the plasma membrane once and ending with a short cytoplasmic tail. The ligand-binding head consists of a seven-bladed β-propeller domain from the α-subunit that associates noncovalently with a GTPase-like domain, βA, from the β-subunit (3). Contacts between the cytoplasmic tails and transmembrane segments hold the integrin in an inactive state (unable to bind physiologic ligand). Binding of talin to the β-cytoplasmic tail breaks these contacts, switching the ectodomain into the active (ligand-competent) conformation, a process called “inside-out” signaling (4). Ligand binding then triggers global conformational changes that propagate through the plasma membrane to the cytoplasmic tails, leading to “outside-in” signaling.

Integrin-ligand interactions are regulated in a complex manner by divalent cations (5–8). Although Mn2+ and, to a lesser extent, Mg2+ stimulate ligand binding, Ca2+ is typically inhibitory. The ligand-binding face of the βA domain is decorated by three metal ion-binding sites: a metal ion-dependent adhesion site (MIDAS),4 flanked on one side (facing the propeller domain of the α-subunit) by a ligand-associated metal ion-binding site (LIMBS), and on the opposite side by an Adjacent to MIDAS (ADMIDAS) (9). A ligand aspartate completes the octahedral metal coordination of an Mg2+ (or Mn2+) at MIDAS in ligand-bound integrins. Ca2+ but not Mg2+ binds preferentially at LIMBS and ADMIDAS in physiologic buffer conditions, and both sites can coordinate Mn2+. The metal ion at LIMBS stabilizes the one at MIDAS (9–11), thus acting as a positive regulator of ligand binding to integrins, whereas the ADMIDAS metal ion can stabilize alternate inactive and active conformations of the integrin (2).

At the ligand-binding face of βA domain, the LIMBS loop residues Arg216, Asp217, and Ala218 contact residues in the α-subunit propeller domain (Fig. 1), but a potential role of the α-subunit in regulating metal ion occupancy in the βA domain has not been explored. In this study, we carried out computational and functional studies on the two β3 integrins αVβ3 and αIIbβ3. Our studies reveal an important role of the α-subunit in regulating metal ion stability at LIMBS in β3 integrins. The significance of this finding is discussed.

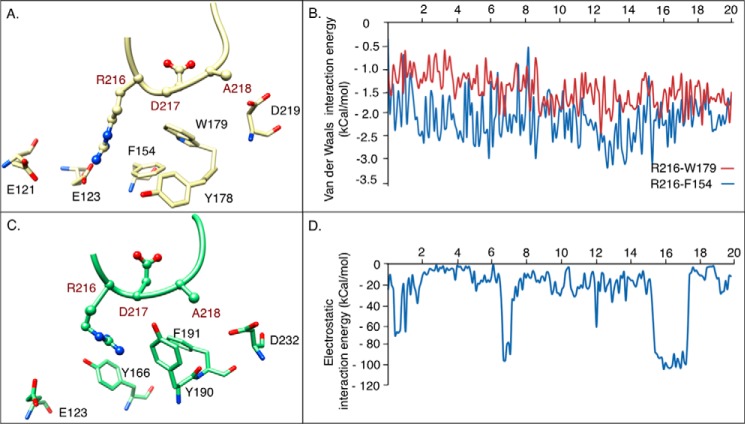

FIGURE 1.

α-subunit residues facing LIMBS in β3 integrins. A ribbon diagram showing the residues from αIIb and αV facing LIMBS loop residues Arg216-Ala218 is presented. The β3 subunits of unliganded αIIbβ3 (green, 3fcs.pdb) and αVβ3 (yellow, 4g1e.pdb) ectodomains were superposed with Chimera. The metal ion (M2+) at LIMBS (sphere) has the color of the respective integrin. αIIb and αV residues are labeled in green and black, respectively, and the LIMBS residues are labeled in red.

EXPERIMENTAL PROCEDURES

Molecular Dynamics Simulations Design

The crystal structures of the ectodomains of αIIbβ3 (Protein Data Bank (PDB) 3fcs) (12) and αVβ3 (PDB 4g1e) (13) were downloaded from the Protein Data Bank. In αIIbβ3, LIMBS (also known as SymBS, synergistic metal-binding site), MIDAS, and ADMIDAS were occupied by Ca2+, Mg2+, and Ca2+ respectively. Because only LIMBS was metal-occupied (by Ca2+) in unliganded αVβ3 structure, Mg2+ and Ca2+ were respectively placed at MIDAS and ADMIDAS such that their initial distances (i.e. before minimization) from all the proximal oxygen atoms were between 2.4 and 4 Å. Mutations were made to the native structures using the software Swiss-Pdb Viewer 4.1.0 (14). All non-protein atoms were removed from αIIbβ3 and αVβ3 structures, leaving α- and β-subunits with nearly 24,000 atoms for each, including hydrogens. Proteins were solvated in water boxes of sizes 168 × 169 × 207 Å (for αVβ3) and 180 × 144 × 226 Å (for αIIbβ3), adding ∼183,000 and 185,000 water molecules to αVβ3 and αIIbβ3, respectively, and ionized with 150 mm KCl. To investigate the effects of Phe191 in αIIb and Trp179 in αV on coordinating divalent cations at LIMBS, six distinct combinations of cation type and mutation for αIIbβ3 and four for αVβ3 were tested. To investigate the effects of each cation arrangement, the αIIbβ3 and αVβ3 structures were equilibrated with LIMBS-MIDAS-ADMIDAS occupancies of Ca2+-Mg2+-Ca2+ and Mn2+-Mn2+-Mn2+.

Molecular Dynamics Simulations

MD simulations of the integrin ectodomain were performed with NAMD cvs_20130828 software package (15). The CHARMM27 force field parameter (16) was used to model the protein. The TIP3P model (17) was used for water molecules. Structures were visualized with Visual Molecular Dynamics (VMD) (18) or Chimera (19). The crystal structures of the ligand-free forms of αIIbβ3 and of αVβ3 ectodomains were used without modification, except for the manual placement of metal ions at LIMBS and ADMIDAS in αVβ3 and the removal of the sugar and water molecules before solvation. All simulations were carried out at the computing facilities of the National Energy Research Scientific Computing Center (NERSC). Periodic boundary conditions were applied in all three directions. Afterward, the entire system was minimized for 20,000 steps followed by 20 or 40 ns of equilibration. A time step of 2 fs was used in all simulations. The temperature and pressure of the systems were held constant at 1 atmosphere and 310 K respectively, using the isothermal-isobaric ensemble with the Langevin piston and Hoover method, as successfully used for modeling integrins (20–22). We performed 20 or 40 ns of MD simulation for each run, and the trajectories were used for all analyses. The cutoff distance for non-bonded interactions was 1.2 nm, and the particle mesh Ewald method was used for electrostatic force calculations (15). All B-factors were set at zero. The hydrogen atom bond length was constrained using the SHAKE algorithm (23).

Structure Analysis

Two parameters, root mean square deviation (r.m.s.d.) values of the LIMBS metal ion and the energy of interaction of the metal ion with the LIMBS pocket, were used to evaluate stability of the metal ion at LIMBS. The r.m.s.d. of a single atom is a measure of its distance at each time step from the initial position of the ion. Hence, higher r.m.s.d. values represent fluctuations with larger amplitudes and less stable ion pocket bonds. Higher interaction energies reflect higher bond stability between the ion and LIMBS or between the α-subunit and the LIMBS loop comprising residues Arg216, Asp217, and Ala218. To let systems equilibrate for a considerable time span before starting to take samples for r.m.s.d. measurements, r.m.s.d. values for the ion were averaged over time steps between t = 16–20 ns for all simulations (n = 40). Energies of interaction between the divalent ion and the LIMBS pocket were estimated using Langevin dynamics. As this energy of interaction did not show significant fluctuations throughout the simulations, values for energy were averaged over t = 0–20 ns (n = 200).

Reagents and Site-directed Mutagenesis

Restriction and modification enzymes were obtained from New England Biolabs Inc. (Beverly, MA), Invitrogen Life Technologies, or Fisher Scientific. All cell culture reagents were obtained from Invitrogen Life Technologies. The non-inhibitory monoclonal antibody (mAb) AP3 (American Type Culture Collection, ATCC) detects the β3 subunit in all conformations. The heterodimer-specific mouse mAbs CD41P2 to αIIbβ3 and LM609 to αVβ3 were from Millipore (Danvers, MA). The function-blocking anti-β1 mAb P5D2 was from R&D Systems, Inc. (Minneapolis, MN). Mouse mAb AP5 detects the N-terminal sequence in the PSI domain only in high affinity/ligand-bound states. The Fab fragment of AP5 was prepared by papain digestion followed by anion exchange and size-exclusion chromatography. The allophycocyanin-labeled goat anti-mouse Fc-specific IgG antibody was from Jackson ImmunoResearch Laboratories (West Grove, PA). Recombinant αVβ3-specific high affinity fibronectin 10 domain (hFN10) (24) was expressed and purified from Escherichia coli as described (25), and fibronectin-depleted human fibrinogen (FB) was obtained from Enzyme Research Laboratories (South Bend, IN,). Wild-type ligands FN10 and FB and mAbs AP5 (Fab) and AP3 (IgG) were labeled respectively with N-hydroxy succinimidyl esters of Fluor 488 (Alexa Fluor 488) or Alexa Fluor 647 (Invitrogen) according to the manufacturer's instructions. Excess dye was removed using Centri-Spin size-exclusion microcentrifuge columns (Princeton Separations, Adelphia, NJ). The final hFN10, FB, AP5, and AP3 concentrations and dye-to-protein molar ratios (F/P) were determined spectrophotometrically, giving dye:protein molar ratios of 1–5. F191/W (F/W) and F992F/A992A (FF/AA) substitutions in human αIIb, W179/F (W/F), and F990F/A990A (FF/AA) substitutions in human αV and β-genu deletion (Δ-genu) or D158/N (D/N) substitutions in β3 (26) were introduced using site-directed mutagenesis with the QuikChange kit (Agilent Technologies) and confirmed by DNA sequencing.

Transfections and mAb Binding

HEK293T (ATCC) cells were transiently co-transfected with pcDNA3 plasmids encoding different combinations of wild type and mutant β3 integrins using Lipofectamine 2000 reagent (Invitrogen) according to the manufacturer's protocol. Plasmids used encoded full-length wild-type αIIbβ3 or αVβ3, the respective integrin carrying F191/W (αIIbF/Wβ3) or W179/F (αVW/Fβ3) substitutions or encoding constitutively active forms of these integrins by substituting the conserved transmembrane motif F992F (in αIIb) or F990F (in αV) to AA (27) (yielding αIIbF/W+FF/AAβ3 and αVW/F+FF/AAβ3, respectively) or by deleting the β-genu (Δ-genu) sequence (E476DYRPSQ) in β3 (26) (yielding αIIbβ3Δ-genu and αIIbF/Wβ3Δ-genu). In addition, two mutations were created in constitutively active αIIbβ3, one known to cause loss of binding to FB (Y189/A, Y/A in αIIb) (28) (αIIbY/Aβ3Δ-genu), and the second by substituting the LIMBS metal-coordinating residue Asp158 with asparagine (αIIbFF/AAβ3D/N). 48 h after transfection, cells were detached (10 mm EDTA/PBS) and washed twice in Hanks' balanced saline solution (HBSS) and once in HBSS containing 1 mm CaCl2/1 mm MgCl2 (HBSS2+). 6 × 105 αIIbβ3-expressing cells in 100 μl of HBSS+0.5% BSA were stained with the Alexa Fluor 647-labeled Fab fragment of AP5 (10 μg/ml; 30 min; room temperature) followed by one wash and then fixed (1% buffered paraformaldehyde). To assess β3 integrin expression levels, 6 × 105 cells in 100 μl of HBSS+0.5% BSA were incubated with CD41-P2 (anti-αIIbβ3) mAb or LM609 (anti-αVβ3) mAb at 10 μg/ml for 30 min at 4 °C followed by one wash and then addition of allophycocyanin-labeled anti-mouse Fc-specific IgG (10 μg/ml) for 20 min on ice. Samples were again washed once in HBSS and then fixed. Other cells were labeled with Alexa Fluor 647-labeled AP3 (anti-β3) (at 10 μg/ml; 30 min; 4 °C), washed once in HBSS, and then fixed. 20,000 cells were analyzed for each sample using a FACSCalibur or LSRFortessa flow cytometer (BD Biosciences). Binding of CD41-P2, LM609, AP3, and AP5 to β3 integrin-expressing HEK293T was expressed as mean fluorescence intensity, as determined using the FlowJo software (BD Biosciences). Cell binding of AP5 was normalized by dividing its mean fluorescence intensity by the mean fluorescence intensity for CD41-P2 and multiplying by 100.

Soluble Ligand Binding Assays

For ligand binding experiments, 1 mm CaCl2/1 mm MgCl2 or 1 mm MnCl2 was added to 6 × 105 β3 integrin-expressing HEK293T cells in 100 μl of HBSS buffer containing 0.5% BSA and incubated in the presence of a saturating amount of Alexa Fluor 488-labeled FB (160 μg/ml) or Alexa Fluor 488-labeled wild-type FN10 (12.6 μg/ml) for 30 min at 25 °C. To block any potential interaction of FN10 with endogenous β1 integrins in HEK293T, αIIbβ3-expressing HEK293T cells were preincubated with the function-blocking anti-β1 mAb P5D2 before adding Alexa Fluor 488-labeled FN10. Saturating amounts of each ligand were derived from dose-response curves, where labeled ligand was added in increasing concentrations to HEK293T cells expressing constitutively active β3 integrins in the presence of 1 mm MnCl2. Integrin-ligand interactions in the presence of varying concentrations of Mn2+ were measured by adding increasing amounts of MnCl2 to a mixture of β3 integrin-expressing cells and saturating amounts of Alexa Fluor 488-labeled ligand. Treated cells were then incubated with Alexa Fluor 647-labeled AP3 (10 μg/ml; 30 min; 4 °C) followed by washing once in HBSS containing the corresponding concentration of Mn2+. Cells were then fixed with 1% paraformaldehyde and analyzed by flow cytometry. Binding of soluble ligand to β3 integrin-expressing cells was normalized by dividing mean fluorescence intensity by that for Alexa Fluor 647-labeled AP3 and multiplying by 100. Mean and S.D. values from three independent experiments were calculated and compared using Student's t test. Non-linear curve fittings of the dose-response curves were performed using GraphPad Prism (GraphPad Software Inc., La Jolla, CA).

RESULTS

LIMBS Structure and Stability of the Metal Ion in β3 Integrins

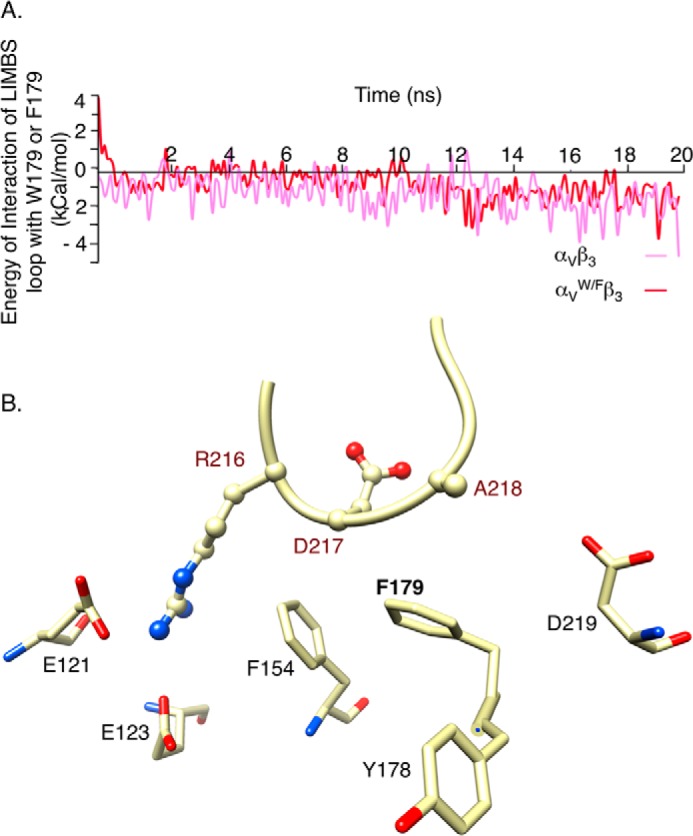

Measurements of the energy of interaction of αV and αIIb subunits with the α-subunit-facing LIMBS loop residues Arg216-Asp217-Ala218 revealed a stronger (2–3-fold) interaction of αV with the LIMBS loop when compared with αIIb. This difference was first detected at 8 ns of simulations and maintained through 40 ns (Fig. 2A).

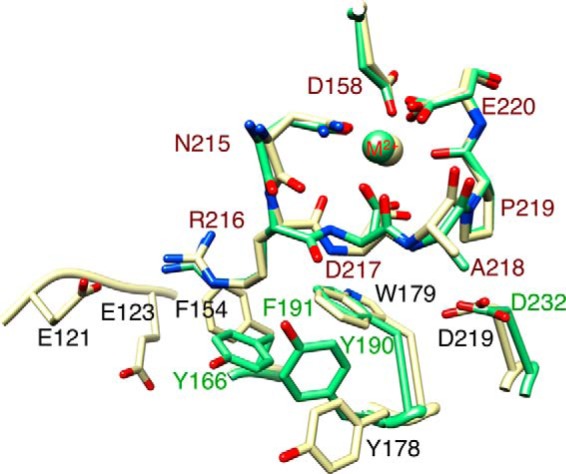

FIGURE 2.

α-subunit/LIMBS interaction energies and LIMBS conformations in β3 integrins. A, computed energy of interaction between αIIb and αV subunits and LIMBS loop residues Arg216-Ala218. The two trajectories appear to equilibrate after around 8 ns of simulation. The transient peak seen afterward (at ∼16 ns) most likely represents a high energy local minimum state that the system occasionally takes, rather than simply a random fluctuation. B and C, snapshots of molecular dynamics simulations at t = 20 ns, showing structures of LIMBS in αIIbβ3 (B) and αVβ3 (C), in the same orientation, with the LIMBS Ca2+ shown as a large sphere in each case. In αIIbβ3, the LIMBS metal ion contacts six primary oxygens (magnified red spheres) and two secondary oxygens (small red spheres) (B). In αVβ3, the LIMBS metal ion also contacts six primary oxygens but only one secondary oxygen (C). Note that the side chain of Arg216 is stretched out in C versus in B and that five primary oxygens in αVβ3 (C) lie in one plane, in contrast to the octahedral arrangement of the primary oxygens in αIIbβ3 (B).

MD simulations after a few nanoseconds of equilibration showed that Ca2+ coordination at LIMBS in αIIbβ3 comprised six “primary” oxygens (i.e. the two carboxyl oxygens of Asp158 and Asp217, one carboxyl oxygen of Glu220, and the carbonyl oxygen of Pro219) (Fig. 2B), which hold a mean distance of 2.2–2.3 Å from the encapsulated cation for the entire simulation, along with two “secondary” oxygens (i.e. the carbonyl oxygens of Asp217 and Ala218), whose mean distance from the cation was no more than 4.5 Å over the whole trajectory. The primary oxygens remained in close contact with the Ca2+ at LIMBS, forming highly stable bonds with a mean length of 2.2–2.3 Å and fluctuation amplitude below 0.5 Å. The primary coordinating oxygens formed an octahedral arrangement, with a planar surface formed by OD2 of Asp158, OE1 of Glu220, OD1 of Asp217, and the carbonyl oxygen of Pro219, with OD1 of Asp158 and OD2 of Asp217 at the top and bottom of the plane, respectively (Fig. 2B), restricting cation fluctuations. Replacing Ca2+ with Mn2+ in LIMBS, MIDAS, and ADMIDAS of αIIbβ3 increased the energy of interaction of Mn2+ with LIMBS by 5–8% and had a small but significant effect on r.m.s.d. (Table 1).

TABLE 1.

Summary of mean r.m.s.d. and interaction energy values for tested β3 integrins

| Integrin and β3 metal ion occupancy state | αIIbβ3 (Ca2+-Mg2+-Ca2+) |

αIIbβ3 (Mn2+-Mn2+-Mn2+)a |

αVβ3 (Ca2+-Mg2+-Ca2+)a |

αVβ3 (Mn2+-Mn2+-Mn2+)a |

||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Wild type | F191/W | D158/N | Wild type | F191/W | D158/N | Wild type | W179/F | Wild type | W179/F | |

| r.m.s.d. (Å) | ||||||||||

| Mean | 2.0 | 8.3 | 14.5 | 2.7 | 11.8 | 4.7 | 12.3 | 6.1 | 11.0 | 4.7 |

| S.D. | 0.5 | 1.2 | 1.2 | 1.4 | 1.1 | 1.1 | 0.7 | 0.7 | 0.8 | 1.0 |

| p valueb | <0.001 | <0.001 | 0.002 | <0.001 | <0.001 | <0.001 | <0.001 | <0.001 | <0.001 | |

| Energy of interaction between LIMBS and metal ion (kcal/mol) | ||||||||||

| Mean | 859 | 865 | 620 | 930 | 913 | 752 | 775 | 732 | 779 | 780 |

| S.D. | 20 | 14 | 14 | 17 | 23 | 15 | 15 | 13 | 15 | 16 |

| p valueb | <0.001 | <0.001 | <0.001 | <0.001 | <0.001 | <0.001 | <0.001 | <0.001 | <0.001 | |

a Integrin mutation.

b All p values were compared to wild-type αIIbβ3 (Ca2+-Mg2+-Ca2+) structure.

In contrast, the LIMBS pocket is distorted toward a planar shape in αVβ3 (Fig. 2C), the result of the stronger interaction that pulled the LIMBS loop toward αV, changing metal ion coordination at this site. MD simulations showed that Ca2+ at LIMBS is coordinated by six primary oxygens (the two carboxyl oxygens of Asp158 and Asp217, the carbonyl oxygen of Pro219, and the carboxyl oxygen of Asn215), but only one secondary coordinating oxygen, the carbonyl oxygen from Asp217 (Fig. 2C). The carboxyl oxygens of Asp158 and Asp217 as well as the carbonyl oxygen of Pro219 all form one planar surface that surrounds the cation, with only the side chain oxygen of Asn215 interacting with the cation at the bottom of the plane (Fig. 2C). These changes made Ca2+ at LIMBS significantly less stable in αVβ3 when compared with αIIbβ3, as reflected by the significantly higher r.m.s.d. and lower energy of interaction of the metal with LIMBS (Table 1). Replacing Ca2+ with Mn2+ in LIMBS, MIDAS, and ADMIDAS of αVβ3 had minimal effects on r.m.s.d. or on the energy of interaction of Mn2+ with LIMBS (Table 1).

Structural Basis for the Stronger Interaction of αV with the LIMBS Loop

In αVβ3, all three LIMBS loop residues were involved in more extensive interactions with αV: Arg216 side chain was engaged in strong ionic bonds with Glu121 and Glu123, and its carbonyl oxygen occasionally H-bonded the side chain of Tyr178 (H-bond probability 0.5%). Arg216 also formed van der Waals contacts with Phe154 and with the indole group of Trp179 (Fig. 3, A and B). In addition, the main and side chains of Asp217 formed van der Waals contacts with the indole group of Trp179, and the side chain of Ala218 contacted the carboxyl oxygen of Asp219 in αV. These interactions stretched the LIMBS loop toward αV, distorting LIMBS.

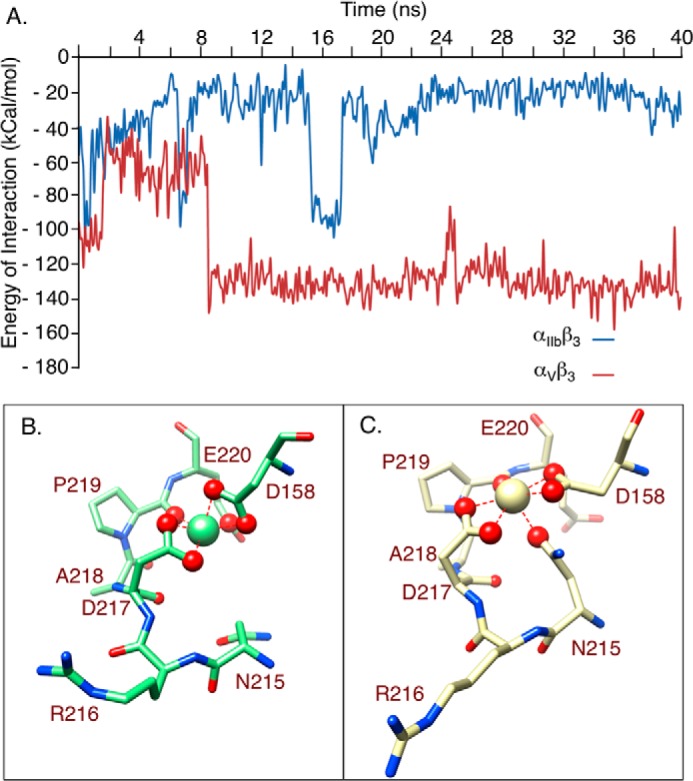

FIGURE 3.

α-subunit residues interacting with the LIMBS loop. A, snapshot of MD simulations at 20 ns showing interactions of the LIMBS loop Arg216-Ala218 residues (shown as ball and stick) with αV subunit residues (shown as stick). The structures in A and C are shown in the same orientation after superposing LIMBS of each. LIMBS residues are labeled red in A and C (also in Figs. 4B and 5B). In αV, the LIMBS loop interacts with the Phe154, Tyr178, Trp179, Asp219, Glu121, and Glu123 of αV. B, MD simulations showing van der Waals energy of interaction between Arg216 of the LIMBS loop with Trp179 and Phe154 of αV. C, snapshot of MD simulations at 20 ns showing interactions of the LIMBS loop Arg216-Ala218 residues with αIIb subunit residues (shown as stick). In αIIb, interactions are limited to the corresponding residues Tyr166, Tyr190, Phe191, and Asp232 and a transient interaction with Glu123. D, electrostatic energy of interaction between Arg216 of the LIMBS loop and Glu123 of αIIb. Occasional jumps to higher energy levels represent ionic bonds between Arg216 and Glu123. The energy peaks at t = 7 and 16 ns show sharp increases to the same value of about 100 kcal/mol, suggesting that the ionic bond occurs at a local energy minimum that the system continues to take, whereas the Arg216-Glu123 bond spends most of the simulation time in a lower electrostatic energy state (i.e. longer bond distance).

In contrast, interaction of αIIb with LIMBS loop residues Arg216-Asp217-Ala218 was primarily limited to Arg216. The side chain of Arg216 formed intermittent H-bonds with the hydroxyl group of Tyr190 (H-bond probability 5.0%), and its carbonyl oxygen contacted the side chain of Tyr190 (Fig. 3C). Arg216 side chain also formed occasional ionic interactions with Glu123 (Fig. 3D), but made no contacts with Phe191. Additionally, Asp232 made intermittent van der Waals contacts with the side chain of Ala218.

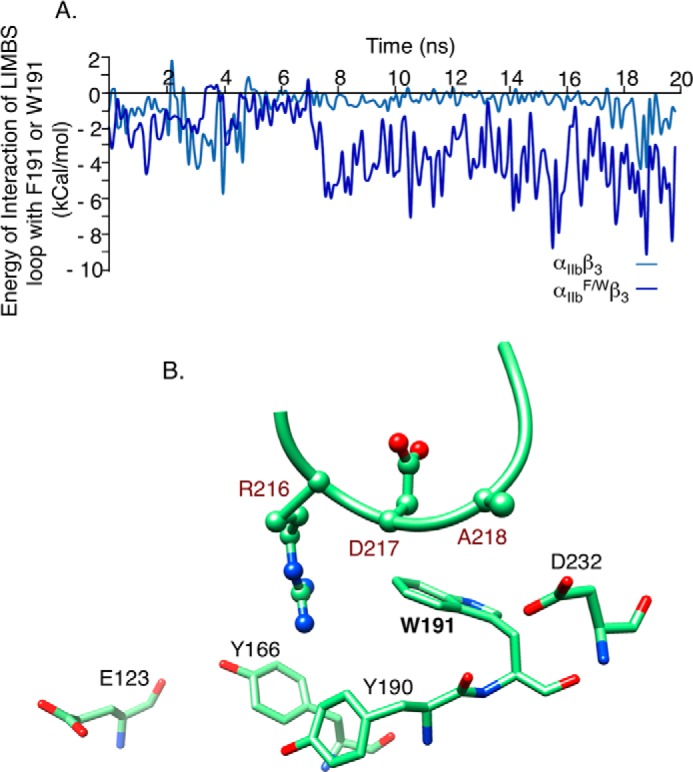

Effects of Modifying αIIb and αv on Stability of the Metal Ion at LIMBS

Of the α-subunit residues contacting the LIMBS loop residues Arg216-Asp217-Ala218, the side chains of Phe191 in αIIb and Trp179 in αV are superimposable (Fig. 1). We evaluated the impact of interchanging these two residues on stability of the metal ion at LIMBS in the two β3 integrins. As an internal control, we measured the effects of destabilizing the metal ion at LIMBS through the D158/N substitution (which removes one of the main coordinating oxygens from the metal ion). MD simulations showed that implementing the D158/N mutation in αIIbβ3 yielded a significant increase in r.m.s.d. (∼2-fold) and a reduction in the energy of interaction (Table 1), both reflecting destabilization of the metal ion at LIMBS.

Implementing the F191/W substitution in αIIb significantly increased the energy of interaction of the LIMBS loop with the bulkier Trp191 in αIIbF/W when compared with Phe191 in wild-type αIIb (Fig. 4A). Snapshot of the structure at t = 20 ns showed that the side chain of Arg216 of β3 releases its interaction with Tyr190 and forms van der Waals contacts with the indole group of Trp191 in αIIbF/W (compare Fig. 4B with Fig. 3C), pulling the LIMBS loop region toward the αIIbF/W propeller domain. With Trp191 and Tyr190 pulling the LIMBS loop in the same direction, Ala218 is brought closer to Asp232 to form more contacts, increasing the energy of interaction of αIIbF/W with the LIMBS loop and deforming the octahedral shape of the pocket. These movements displaced the oxygens forming the LIMBS pocket from their native pattern toward a more planar configuration. Although the energy of interaction of Ca2+ or Mn2+ with the LIMBS pocket in the αIIbF/Wβ3 structure did not change, r.m.s.d. increased by ∼4-fold (Table 1). Hence, it appears that the energetic component of the free energy remains unchanged upon applying F191/W, whereas the entropic component is highly changed upon deformation of the pocket as represented by a 4-fold increase in r.m.s.d.

FIGURE 4.

Effect of F191/W change in αIIbβ3 on interaction energies and shape of LIMBS. A, computed energy of interaction between LIMBS loop residues Arg216-Ala218 and Trp191 in αIIbF/W. B, snapshot at t = 20 ns of the interactions of LIMBS loop with αIIbF/W residues Tyr166, Tyr190, Trp191, Asp232, and Glu123. Mutating Phe191 to Trp in αIIbF/W enhanced interactions of the larger Trp191 side chain with the LIMBS loop, especially with Arg216, modifying the conformation of the LIMBS pocket (see “Results”).

Implementing the W179/F substitution in αvW/F did not change the energy of interaction of the LIMBS loop with αVW/F (Fig. 5A). However, it reduced fluctuations of the Ca2+ or Mn2+ at LIMBS (r.m.s.d. reduced by ∼2-fold, Table 1), the result of removing the contacts between Trp179 and the LIMBS loop (Fig. 5B). The W179/F substitution did not significantly change the interaction energy of the metal ion with LIMBS (Table 1) because it did not affect the other interactions of αV with the LIMBS loop, particularly with Arg216 (Fig. 5B).

FIGURE 5.

Effect of W179/F in αVβ3 on interaction energies and shape of LIMBS. A, computed energy of interaction between the LIMBS loop residues Arg216-Ala218 and Phe179 in αVW/F. Mutating Trp179 to Phe does not change the energy of interaction with the LIMBS loop significantly. B, snapshot at t = 20 ns of interactions of the LIMBS loop with αV subunit residues Glu121, Glu123, Phe154, Phe179, and Asp219. The W179/F mutation weakens interaction of LIMBS loop with αVW/F, reshaping the LIMBS pocket. The structure is shown in the same orientation as in Fig. 4B.

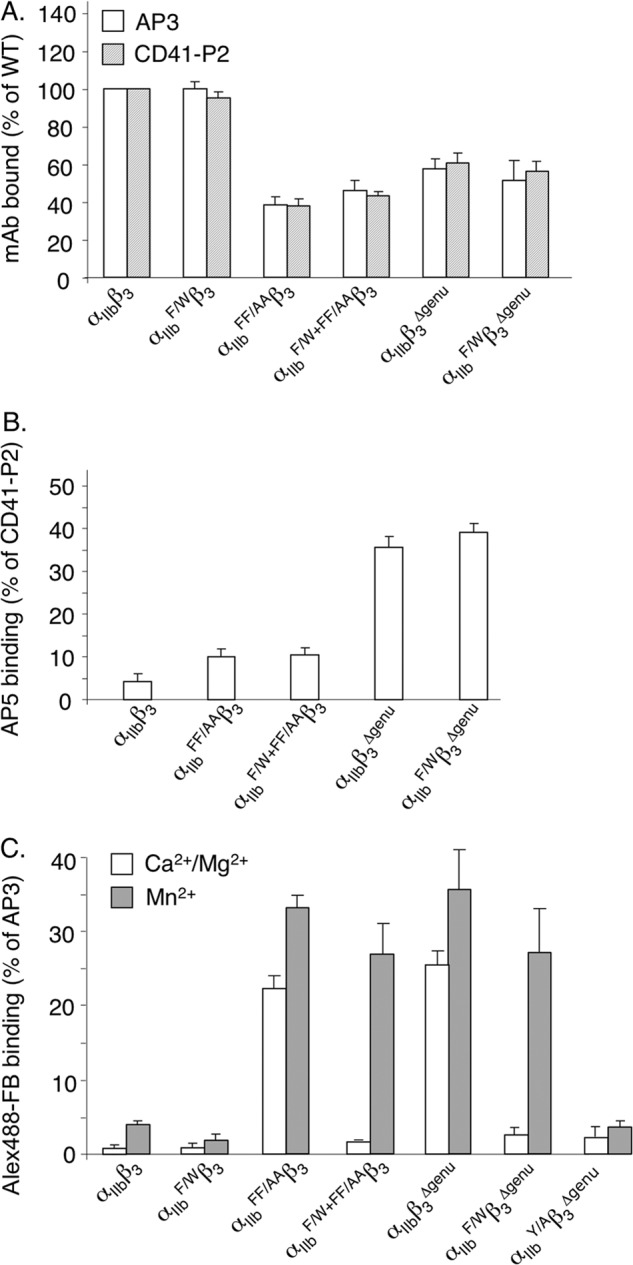

Binding of Wild-type and F191/W Mutant αIIbβ3 to Soluble Ligand

We next sought experimental validation of the computational studies. We expressed recombinant αIIbF/Wβ3 in its resting and mutationally activated (αIIbF/W+FF/AAβ3, αIIbF/Wβ3Δ-genu) states in HEK293T cells and compared its surface expression, structure, and ligand binding capacity with that of constitutively active wild type αIIbFF/AAβ3. As shown in Fig. 6A, surface expression of the mutant resting or constitutively active heterodimeric receptor was comparable with that of resting or constitutively active wild-type αIIbβ3, and the F191/W mutation did not change the recognition of the constitutively active integrin by the ligand-induced binding site (LIBS) mAb AP5 (Fig. 6B). Binding of WT αIIbβ3 to soluble Alexa Fluor 488-labeled FB (Alexa Fluor 488-FB) was minimal in the presence of 1 mm each of the physiologic divalent cations Ca2+ and Mg2+ (Ca2+/Mg2+), but increased only slightly in 1 mm Mn2+ (Fig. 6C). αIIbF/W+FF/AAβ3, αIIbF/Wβ3Δ-genu bound constitutively to Alexa Fluor 488-FB in Ca2+/Mg2+-containing buffer, as expected, with 1 mm Mn2+ further increasing ligand binding by ∼1.5-fold (Fig. 6C).

FIGURE 6.

Effect of αIIb F191/W mutation in αIIbβ3 on cell surface expression, activation, and binding to soluble ligand. A, histograms (mean ± S.D.; n = 3) comparing cell surface expression and heterodimer formation of αIIbβ3, αIIbF/Wβ3, and constitutively active αIIbFF/AAβ3, αIIbβ3Δ-genu, αIIbF/W+FF/AAβ3, and αIIbF/Wβ3Δ-genu. Constitutive activation reduced expression of the wild type and F191/W integrin to equivalent degrees. B, histograms (mean ± S.D.; n = 3) showing binding of the LIBS mAb AP5 to αIIbβ3 and to constitutively active αIIbFF/AAβ3, αIIbF/W+FF/AAβ3, αIIbβ3Δ-genu, and αIIb F/Wβ3Δ-genu. Binding was expressed as a percentage of binding of the heterodimer-specific mAb CD41-P2. C, histograms (mean ± S.D.; n = 3) showing binding of wild-type and constitutively active αIIbF/W+FF/AAβ3 to saturating amounts of soluble Alexa Fluor 488-FB (Alex488-FB) in 1 mm Ca2+ plus 1 mm Mg2+ (Ca2+/Mg2+) or 1 mm Mn2+. Binding is expressed as a percentage of Alexa Fluor 647-AP3 mAb staining. F191/W did not significantly impair ligand binding to constitutively active αIIbβ3 in Mn2+. However, ligand binding to constitutively active αIIbβ3 in Mn2+ was abolished when the ligand contact residue Tyr189 was simultaneously mutated to Ala.

Cellular αIIbF/Wβ3 showed minimal binding to soluble Alexa Fluor 488-FB in Ca2+/Mg2 buffer, with 1 mm Mn2+ increasing binding by ∼2-fold (Fig. 6C). Introduction of the F191/W mutation in constitutively active αIIbF/W+FF/AAβ3 and αIIbF/Wβ3Δ-genu integrins abolished ligand binding in the presence of Ca2+/Mg2+, but did not reduce binding in the presence of 1 mm Mn2+ (Fig. 6C). As a negative control, replacing the ligand contact residue Tyr189 in αIIb with alanine abolished binding of cellular αIIbYAβ3Δ-genu to soluble Alexa Fluor 488-FB in 1 mm Mn2+(Fig. 6C), in agreement with a published study (28).

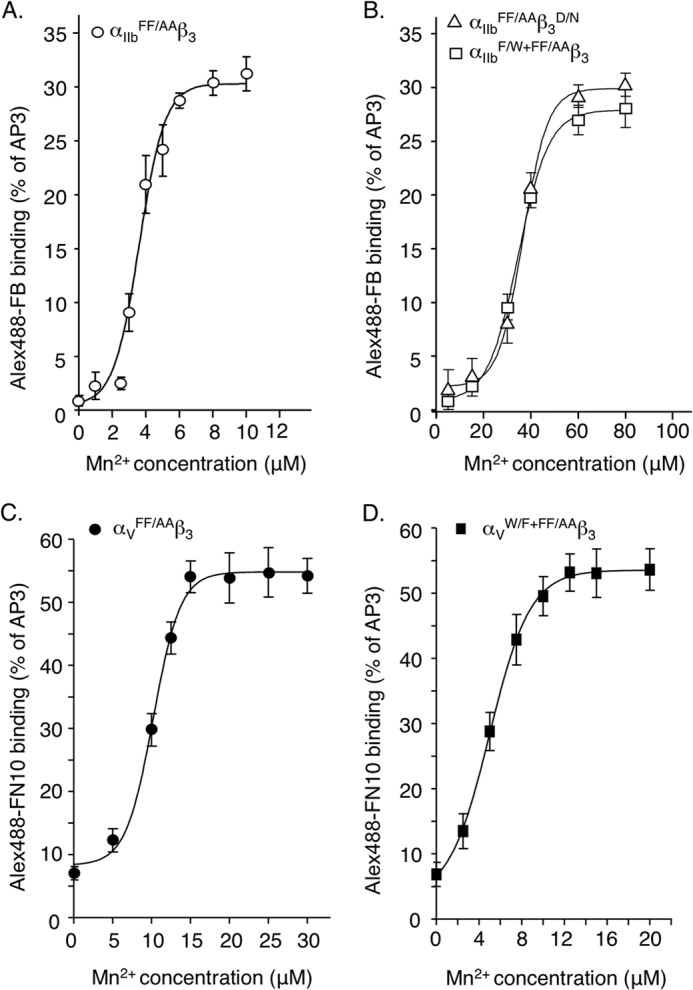

Effects of F191/W in αIIb and W179/F in αV on Apparent Affinity of Mn2+ to the Respective Integrins

We measured the binding of constitutively active wild-type and mutant β3 integrins to saturating amount of soluble ligand across a range of Mn2+ concentrations. Half-maximal binding of αIIbFF/AAβ3 to Alexa Fluor 488-FB was achieved at an Mn2+ concentration of 5.9 μm ± 2.1 (mean ± S.D., n = 3) (Fig. 7A). Removing one of the LIMBS metal-coordinating oxygens (through the D158/N mutation) increased the Mn2+ concentration required for half-maximal binding of ligand to αIIbFF/AAβ3D/N by ∼6-fold to 36.7 ± 8.6 μm, an indirect measure of the reduction in apparent affinity (Kd(app)) of Mn2+ to αIIbFF/AAβ3D/N (Fig. 7B). The F191/W substitution in αIIbFF/AAβ3 yielded an almost identical value (34.6 ± 6.2 μm) (Fig. 7B). In contrast, the W179/F mutation in αV significantly increased the apparent Kd(app) of Mn2+ to the αVW/F+FF/AAβ3 heterodimer (as judged by mAb LM609 binding, not shown) by ∼2-fold (mean ± S.D., 5.0 ± 1.9 μm from 10.2 ± 3.5 μm to αVFF/AAβ3, p = 0.018) (Fig. 7, C and D).

FIGURE 7.

Effect of αIIbF/W, αVW/F, and β3D/N mutations on integrin-ligand interactions in the presence of varying concentrations of Mn2+. A and B, dose-response curves comparing binding of αIIbFF/AAβ3 (A) and αIIbFF/AAβ3D/N and αIIbF/W+FF/AAβ3 (B) with saturating amounts of soluble Alexa Fluor 488-FB (Alex488-FB) in the presence of increasing concentrations of Mn2+. C and D, dose-response curves comparing binding of cellular αVFF/AAβ3 (C) and αVW/F+FF/AAβ3 (D) with saturating amounts of soluble Alexa Fluor 488-FN10 in the presence of increasing concentrations of Mn2+. Binding was expressed as a percentage of Alexa Fluor 647-AP3 mAb binding.

DISCUSSION

In this study, we provide computational and functional evidence that the α-subunit plays an essential role in stability of the metal ion coordination at LIMBS in β3 integrins. By combining these two approaches, we demonstrated the following. 1) interaction of the LIMBS loop with αV is more extensive than with αIIb; 2) metal ion coordination at LIMBS after 20 ns of equilibration becomes planar in αVβ3; 3) changing the αIIb-LIMBS loop interface residue Phe191 to Trp destabilized the metal ion at LIMBS, whereas a Trp179 to Phe mutation in αV produced opposite but weaker effects; and 4) introducing F191/W in cellular αIIbβ3 reduced the apparent affinity of Mn2+ to this integrin; the reverse was observed upon introducing the W179/F mutation in cellular αVβ3.

The higher energy of interaction of αV with the LIMBS loop residues Arg216-Ala218 was directly related to the more extensive contacts αV made with this loop when compared with αIIb. The stronger contacts increased fluctuations of the metal ion at LIMBS in αVβ3, as reflected by the ∼4-fold increase in r.m.s.d., and also increased the mean distances between the coordinating oxygens and the metal ion at LIMBS, as reflected by the reduction in total energy of interaction of the metal ion with the pocket. These observations may offer an explanation for the variable occupancy of LIMBS by metal ion in crystal structures of unliganded αVβ3 ectodomains, where LIMBS was metal-occupied in one (4g1e.pdb, used in this study) (13) but not in four other unliganded αVβ3 ectodomain structures (9, 26, 29, 30). The lack of metal occupancy at LIMBS was attributed to unfavorable crystallization conditions (13). However, LIMBS is metal ion occupied in αVβ3 under the same crystallization conditions when αVβ3 is ligand-bound (9, 25). The data produced in this study suggest that variability in LIMBS occupancy by metal is the result of the different contacts the LIMBS loop makes with αV in contrast to αIIb. In the presence of ligand, Glu220 of the βA domain provides an extra primary oxygen, stabilizing the metal ion at LIMBS. In the absence of ligand, this stabilizing influence is lost, and the metal ion is freer to escape LIMBS. This scenario is reflected in the higher r.m.s.d. and lower energy of interaction of the metal ion with LIMBS in unliganded αVβ3 when compared with αIIbβ3 (Table 1).

αVβ3 is widely expressed in tissues including bone, where it mediates dynamic cell adhesion (31, 32). The majority of Mn2+ in the body is sequestered in bone (33) to levels that approach the Kd of αVβ3 for Mn2+ (7), suggesting that Mn2+ plays an important role in regulating αVβ3 function in this tissue. In contrast, αIIbβ3 is solely expressed on circulating platelets in blood containing high levels of its physiologic ligands, mainly fibrinogen, and mm concentrations of the divalent cations Ca2+ and Mg2+. Maintaining αIIbβ3 in a dormant inactive state in this environment is therefore essential to prevent pathologic thrombosis. The present data provide insights into how regulation can be tailored to the particular environment where an integrin is expressed. Occupancy of LIMBS, MIDAS, and ADMIDAS by metal ions in unliganded αIIbβ3 may explain the rapid ligand association rates to activated αIIbβ3 (7). This potential proactivation tendency at the ligand-binding site must be counteracted by energy barrier(s) to activation elsewhere to effectively keep αIIbβ3 in an inactive state on circulating resting platelets. One such barrier may exist in the integrin leg segments, between the α-subunit Calf-2 domain and the β3 subunit EGF-like 4 (IE4) and βTD domains (34). Disruption of this interface rendered αIIbβ3 as susceptible to Mn2+-induced ligand binding as αVβ3 (34). In αVβ3, where this Calf-2/IE4-βTD barrier is weak or absent (34), a relatively stronger αV-LIMBS interface may help favor the inactive αVβ3 conformation, thus limiting stable occupancy of the metal ion in this integrin to conditions when ligand is also accessible.

Acknowledgment

We thank Dr. José Luis Alonso for helpful discussions.

This work was supported, in whole or in part, by National Institutes of Health Grants DK088327, DK096334, and DK007540 (to M. A. A.) and by a National Science Foundation CAREER Award CBET-0955291 (to M. R. K. M.).

- MIDAS

- metal ion-dependent adhesion site

- LIMBS

- ligand-associated metal-binding site

- ADMIDAS

- adjacent to MIDAS

- FB

- fibrinogen

- MD

- molecular dynamics

- r.m.s.d.

- root mean square deviation

- HBSS

- Hank's balanced saline solution.

REFERENCES

- 1. Hynes R. O. (2002) Integrins: bidirectional, allosteric signaling machines. Cell 110, 673–687 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Arnaout M. A., Goodman S. L., Xiong J. P. (2007) Structure and mechanics of integrin-based cell adhesion. Curr. Opin. Cell Biol. 19, 495–507 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Xiong J. P., Stehle T., Diefenbach B., Zhang R., Dunker R., Scott D. L., Joachimiak A., Goodman S. L., Arnaout M. A. (2001) Crystal structure of the extracellular segment of integrin αVβ3. Science 294, 339–345 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Moser M., Legate K. R., Zent R., Fässler R. (2009) The tail of integrins, talin, and kindlins. Science 324, 895–899 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Hu D. D., Barbas C. F., Smith J. W. (1996) An allosteric Ca2+ binding site on the β3-integrins that regulates the dissociation rate for RGD ligands. J. Biol. Chem. 271, 21745–21751 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Mould A. P., Akiyama S. K., Humphries M. J. (1995) Regulation of integrin α5β1-fibronectin interactions by divalent cations: evidence for distinct classes of binding sites for Mn2+, Mg2+, and Ca2+. J. Biol. Chem. 270, 26270–26277 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Smith J. W., Piotrowicz R. S., Mathis D. (1994) A mechanism for divalent cation regulation of β3-integrins. J. Biol. Chem. 269, 960–967 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Loftus J. C., O'Toole T. E., Plow E. F., Glass A., Frelinger A. L., 3rd, Ginsberg M. H. (1990) A β3 integrin mutation abolishes ligand binding and alters divalent cation-dependent conformation. Science 249, 915–918 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Xiong J. P., Stehle T., Zhang R., Joachimiak A., Frech M., Goodman S. L., Arnaout M. A. (2002) Crystal structure of the extracellular segment of integrin αVβ3 in complex with an Arg-Gly-Asp ligand. Science 296, 151–155 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Murcia M., Jirouskova M., Li J., Coller B. S., Filizola M. (2008) Functional and computational studies of the ligand-associated metal binding site of β3 integrins. Proteins 71, 1779–1791 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Valdramidou D., Humphries M. J., Mould A. P. (2008) Distinct roles of β1 metal ion-dependent adhesion site (MIDAS), adjacent to MIDAS (ADMIDAS), and ligand-associated metal-binding site (LIMBS) cation-binding sites in ligand recognition by integrin α2β1. J. Biol. Chem. 283, 32704–32714 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Zhu J., Luo B. H., Xiao T., Zhang C., Nishida N., Springer T. A. (2008) Structure of a complete integrin ectodomain in a physiologic resting state and activation and deactivation by applied forces. Mol. Cell 32, 849–861 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Dong X., Mi L. Z., Zhu J., Wang W., Hu P., Luo B. H., Springer T. A. (2012) αVβ3 integrin crystal structures and their functional implications. Biochemistry 51, 8814–8828 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Guex N., Peitsch M. C. (1997) SWISS-MODEL and the Swiss-PdbViewer: an environment for comparative protein modeling. Electrophoresis 18, 2714–2723 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Phillips J. C., Braun R., Wang W., Gumbart J., Tajkhorshid E., Villa E., Chipot C., Skeel R. D., Kalé L., Schulten K. (2005) Scalable molecular dynamics with NAMD. J. Comput. Chem. 26, 1781–1802 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. MacKerell A. D., Jr., Banavali N., Foloppe N. (2000) Development and current status of the CHARMM force field for nucleic acids. Biopolymers 56, 257–265 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Jorgensen W. L., Chandrasekhar J., Madura J. D., Impey R. W., Klein M. L. (1983) Comparison of simple potential functions for simulating liquid water. J. Chem. Phys. 79, 926–935 [Google Scholar]

- 18. Humphrey W., Dalke A., Schulten K. (1996) VMD: visual molecular dynamics. J. Mol. Graph. 14, 33–38, 27–38 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Pettersen E. F., Goddard T. D., Huang C. C., Couch G. S., Greenblatt D. M., Meng E. C., Ferrin T. E. (2004) UCSF Chimera: a visualization system for exploratory research and analysis. J. Comput. Chem. 25, 1605–1612 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Mehrbod M., Mofrad M. R. (2013) Localized lipid packing of transmembrane domains impedes integrin clustering. PLoS Comput. Biol. 9, e1002948. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Mehrbod M., Trisno S., Mofrad M. R. (2013) On the activation of integrin αIIbβ3: outside-in and inside-out pathways. Biophys. J. 105, 1304–1315 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Chen W., Lou J., Hsin J., Schulten K., Harvey S. C., Zhu C. (2011) Molecular dynamics simulations of forced unbending of integrin αvβ3. PLoS Comput. Biol. 7, e1001086. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Kräutler V., van Gunsteren W. F., Hünenberger P. H. (2001) A fast SHAKE algorithm to solve distance constraint equations for small molecules in molecular dynamics simulations. J. Comput. Chem. 22, 501–508 [Google Scholar]

- 24. Richards J., Miller M., Abend J., Koide A., Koide S., Dewhurst S. (2003) Engineered fibronectin type III domain with a RGDWXE sequence binds with enhanced affinity and specificity to human αvβ3 integrin. J. Mol. Biol. 326, 1475–1488 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Van Agthoven J. F., Xiong J. P., Alonso J. L., Rui X., Adair B. D., Goodman S. L., Arnaout M. A. (2014) Structural basis for pure antagonism of integrin αVβ3 by a high-affinity form of fibronectin. Nat. Struct. Mol. Biol. 21, 383–388 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. Xiong J. P., Mahalingham B., Alonso J. L., Borrelli L. A., Rui X., Anand S., Hyman B. T., Rysiok T., Müller-Pompalla D., Goodman S. L., Arnaout M. A. (2009) Crystal structure of the complete integrin αVβ3 ectodomain plus an α/β transmembrane fragment. J. Cell Biol. 186, 589–600 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27. Wegener K. L., Partridge A. W., Han J., Pickford A. R., Liddington R. C., Ginsberg M. H., Campbell I. D. (2007) Structural basis of integrin activation by talin. Cell 128, 171–182 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28. Kamata T., Irie A., Tokuhira M., Takada Y. (1996) Critical residues of integrin αIIb subunit for binding of αIIbβ3 (glycoprotein IIb-IIIa) to fibrinogen and ligand-mimetic antibodies (PAC-1, OP-G2, and LJ-CP3). J. Biol. Chem. 271, 18610–18615 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29. Mahalingam B., Van Agthoven J. F., Xiong J. P., Alonso J. L., Adair B. D., Rui X., Anand S., Mehrbod M., Mofrad M. R., Burger C., Goodman S. L., Arnaout M. A. (2014) Atomic basis for the species-specific inhibition of αV integrins by mAb 17E6 is revealed by the crystal structure of αVβ3 ectodomain-17E6 Fab complex. J. Biol. Chem. 289, 13801–13809 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30. Xiong J. P., Stehle T., Goodman S. L., Arnaout M. A. (2004) A novel adaptation of the integrin PSI domain revealed from its crystal structure. J. Biol. Chem. 279, 40252–40254 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31. Lakkakorpi P. T., Horton M. A., Helfrich M. H., Karhukorpi E. K., Väänänen H. K. (1991) Vitronectin receptor has a role in bone resorption but does not mediate tight sealing zone attachment of osteoclasts to the bone surface. J. Cell Biol. 115, 1179–1186 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32. Roca-Cusachs P., Gauthier N. C., Del Rio A., Sheetz M. P. (2009) Clustering of α5β1 integrins determines adhesion strength whereas αvβ3 and talin enable mechanotransduction. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 106, 16245–16250 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33. Brandt M., Schramm V. L. (1986) in Manganese in Metabolism and Enzyme Function. (Schramm V. L., EdIer F. C., eds), pp. 3–13, Academic Press, New York [Google Scholar]

- 34. Kamata T., Handa M., Sato Y., Ikeda Y., Aiso S. (2005) Membrane-proximal α/β stalk interactions differentially regulate integrin activation. J. Biol. Chem. 280, 24775–24783 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]