Abstract

Background

Despite various national recommendations advising individuals to reduce their exposure to UV radiation, many people still do not utilize these skin cancer prevention strategies.

Objective

The study assesses patients’ sources of medical information, knowledge of sun protection strategies, and barriers to implement these strategies. The study also compares the overall rate of utilization of skin cancer prevention strategies between healthy and immunocompromised patients.

Materials and Methods

Survey-based study was conducted on 140 Mohs surgery patients.

Results

Seventy-three percent of healthy and 74% of immunosuppressed participants identified sunscreen use as a form of protective strategy; only 36% and 27%, respectively, use sunscreen daily. Participants cite physician and internet as equal sources of medical information. Knowing two or more strategies correlated to a higher self-rating of daily utilization of any protective strategy.

Conclusions

The results of our study show that general knowledge regarding sun protection strategies is still limited, but awareness of multiple strategies correlated with an increase in sun protective behavior. Surprisingly, despite having a much higher incidence of skin cancers, the immunosuppressed group did not show more awareness of prevention strategies or higher utilization compared to healthy participants.

Introduction

Nonmelanoma skin cancer (NMSC), which includes Squamous cell and Basal cell carcinomas (SCC and BCC), is the most common cancer in the United States with more than 3.5 million estimated cases diagnosed annually. Known risk factors for NMSC include age, skin type, chronic wounds, prior radiation, UV radiation, and immunosuppression.2 Much public health efforts, including those from the American Board of Dermatology and the US Department of Health and Human Services, have focused on improving the utilization of protective strategies to reduce exposure to UV radiation, a major risk factor for NMSC in both healthy and immunosuppressed patients. Publicized strategies include appropriate use of sunscreens, avoidance of UV exposure by seeking shade, staying indoors during the hours of peak UV radiation, and wearing protective clothing.3 Unfortunately, patient adherence to these recommendations has been disappointingly low. Prior studies showed that only 41% of women and 22% of men used sunscreen in 1992. 4 More than ten years later, despite increasing efforts by both the primary care and dermatologic medical communities to improve patient education and adherence, almost 50% Americans still reported rare or no use of sunscreens.5 Identified barriers include lack of knowledge, misconceptions regarding personal risks of NMSC, difficulty in initiating behavioral changes, and socioeconomic factors such as time, costs, etc. Some of these barriers have been addressed on a small scale in prior studies that utilized intensive and repetitive written instructions, personalized risk assessment and recommendations, even daily reminders via electronic text messaging.6 However, these proposed strategies either produced rather modest effects or are difficult to implement on a large scale basis.

Of even more pressing concern is the low rate of UV radiation protective strategies utilized by the immunosuppressed population such as patients with organ transplantation, chronic immunosuppressive therapy, chemotherapy, leukemia, lymphoma, and HIV. It is now well established that organ transplant recipients (OTRs) have more than sixty times the risk of developing SCC and more than ten times the risk of developing BCC compared to the general population.7-9 Moreover, these SCCs are considered more aggressive with increased rates of recurrence and metastasis.10-12 OTRs with long-term immunosuppression develop SCC twenty to thirty years earlier with a higher rate of metastasis than in non-immunosuppressed.13 Patients with leukemia and lymphoma show an increased predilection for more aggressive SCCs with increased number of recurrences and larger tumor size despite treatment.14 Due to prolonged survival on current medication regimens, SCCs are also increasing among patients with advanced HIV infection. HIV positive patients were found to have a twofold higher incidence of NMSC compared to HIV negative patients, and this fact is attributed to their higher rates of activities that increase the risk of developing skin cancer including prolonged recreational sun exposure and the use of tanning beds. 15,16

It has been shown that solar and artificial UVR exposure modulates the risk of skin cancer already increased by immunosuppression.17 Thus, reducing UV radiation is of key importance in the primary and secondary prevention of NMSC development in these patients. Given that they have more frequent contact with healthcare providers and higher disease burden that adversely affects overall quality of life, one would surmise that the immunocompromised patients would be more cognizant of their skin cancer risks and have higher rates of utilization of recommended sun protective strategies. However, several studies in both North America and Europe indicated that this is not the case. For instance, a majority of OTRs did not find their risk of skin cancer an important problem.18 Being diagnosed with NMSCs did not significantly improve the rate of sun protection in OTRs, and over 60% of OTRs did not even apply any sunscreen.19 These data demand further studies to gain a better understanding of the major factors that influence sun protective behavior in patients with NMSC.

To the above goal, we conducted a detailed face-to-face survey based study on patients with NMSC undergoing Mohs surgery at a university academic center. The study comprehensively assessed patients’ knowledge of sun protective strategies, their sources of medical information, barriers encountered while trying to implement some of these strategies, and overall rate of utilization. Subgroup analysis compared key outcomes between immunosuppressed and patients with NMSC with normal immune system. The data offered insight into specific actionable measures that can be undertaken to improve patient education and adherence to the recommended sun protective strategies.

Materials and Methods

Our survey-based, descriptive and prospective study was performed at the Dermatologic and Mohs surgery Center of University of California, San Diego (UCSD) Medical Center. This study was funded through “The Medical Student Training in Aging Research (MSTAR) Program” via the National Institute on Aging (NIA) and was exempted by the UCSD Institutional Review Board.

All patients scheduled for Mohs surgery were approached after the first stage of Mohs excision while waiting for the histology to be processed by the Mohs laboratory. An information sheet outlining the purpose of the study and a consent form were provided to them; no identifiable signature was requested on the consent form. If a patient agreed to participate, a twenty minute face-to-face interview with a single interviewer was conducted in the office. The pre-set survey consisted of twenty six questions organized into 4 categories: demographics, knowledge of skin cancer risk factors, knowledge of preventative strategies, and barriers to utilizing prevention strategies. Out of one hundred and forty participants who were approached, all completed the survey. We did not have access to any of the participants’ medical records; all data gathered was from the patients directly. There was no monetary reward for participation in this study. Data was analyzed using percentages and estimated confidence intervals for population at a set 95% confidence interval.

Results

Demographics

One hundred and forty individuals took part in the survey. Immunocompromised state was described as a participant having an organ transplant, being on chronic immunosuppressive therapy, chemotherapy, or having a diagnosis of leukemia, lymphoma or HIV. One hundred and five (75%) of the participants identified themselves as healthy, and thirty five (25%) identified themselves as immunocompromised based on the definition above. Thirteen participants were OTR, 16 received chemotherapy treatment as non-OTR, and 6 were HIV positive. Immunosuppression status was not subsequently verified via chart-review. Seventy percent (n=98) of responders were male and 30% (n=42) were female. The mean participant age was 65 (range 36-96) in the healthy and 62 (range 32-78) in the immunocompromised group with 44% of the healthy participants being in the >70 group. Previous history of NMSC was seen in 63% of immunocompromised and 55% the healthy participants. Occupation involving at least one hour of outdoor activities was present in 40% of healthy and 51% of immunocompromised participants. (See Table 1)

Table 1.

Baseline demographics of study participants

| Healthy n=105(%) | Immunosuppressed n=35(%) | ||

|---|---|---|---|

| Sex | Male | 71 (68) | 27 (77) |

| Female | 34 (32) | 8 (23) | |

| Age | <40 | 2 (2) | 1 (3) |

| 40-49 | 8 (8) | 4 (11) | |

| 50-59 | 18 (17) | 10 (29) | |

| 60-69 | 31 (30) | 12 (34) | |

| ≥70 | 46 (44) | 8 (23) | |

| Previous history of NMSC | 58 (55) | 22 (63) | |

| Occupation with > 1 hour outdoor | 42 (40) | 18 (51) |

Knowledge of Protective Strategies

The major sources of knowledge regarding skin cancer prevention strategies were the media and physicians. Both sources were cited by about half of the healthy patients. In comparison, immunosuppressed participants quoted their doctor as the most common source of knowledge. Additional sources of information included education and family which had similar predominance among both participant groups. (See Table 2)

Table 2.

Named sources of knowledge of preventive strategies among participants

| Total N=140 (%) | Healthy n=105 (%) | Immunosuppressed n= 35 (%) | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Media and Internet | 72 (51) | 55 (52) | 17 (49) |

| Doctor | 72 (51) | 50 (48) | 22 (63) |

| School | 28 (20) | 21 (20) | 7 (20) |

| Family | 23 (16) | 17 (16) | 6 (17) |

When questioned regarding specific skin cancer preventive strategies, more than 70% of participants in both groups cited use of sunscreens, making it the most well-known strategy amongst those addressed by the survey. Use of hats, protective clothing, and limiting sun exposure were cited by 30-40% of participants. Staying indoors during the peak sun hours and limiting artificial UV exposure were the least described protective strategies across both groups with only 10% and <1% of patients mentioning it, respectively. Sixty one percent of healthy (n=64) and 66% of immunocompromised (n=23) participants in both groups were able to name at least 2 skin-protective strategies. Sixty-eight percent of healthy and 80% of immunocompromised answered “yes” to being able to identify a cancerous skin lesion on their body. (See Table 3)

Table 3.

Independently known preventive strategies among healthy and immunosuppressed participants

| Healthy n=105, (%) (95% CI) | Immunosuppressed n=35 (%) (95% CI) | |

|---|---|---|

| Sunscreen | 76 (72) (63-81) | 26 (74) (59-89) |

| Hat | 45 (43) (34-52) | 12 (34) (18-50) |

| Limiting natural sun exposure | 41 (39) (30-48) | 13 (37) (21-53) |

| Limiting artificial sun exposure (tanning booths) | 1(0.01)(negligible) | 2(0.6) (negligible) |

| Protective clothing | 34 (32) (23-41) | 15 (43) (27-59) |

| Staying inside during peak hours of 10-2 | 9 (9) (4-14) | 3 (9) (negligible) |

| Stating ≥2 out of the above | 64 (61) (52-70) | 23 (66) (50-82) |

| Skin self-exam & ability to recognize suspicious skin lesions | 68 (65) (56-74) | 28 (80) (67-94) |

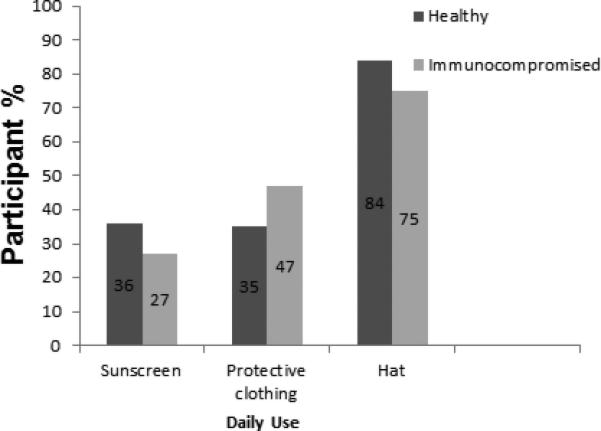

Utilization of Protective Strategies

Overall, the most commonly utilized skin cancer preventive strategy was found to be wearing a hat while outside and the least used strategy was sunscreens. Out of the participants who specifically mentioned wearing a hat as a viable skin protective method, 84% (95% CI 73%-95%) of healthy and 75% (95% CI 51%-100%) of immunocompromised participants report daily current usage. Hat use was twice as popular as wearing sunscreen across both groups. The healthy and immunocompromised groups had similar prevalence of sunscreen use. Out of the participants who mentioned sunscreen as a protective strategy, 36% (95% CI 25%-47%) of healthy, and 27% (95% CI 10%-44%) of immunocompromised individuals reported daily use of the products. Out of those participants who mentioned protective clothing, 62% (95% CI 46%-78%) and 47% (95% CI 22%-72%) of healthy and immunocompromised participants respectively used this clothing every day. (See Figure 1)

Figure 1.

Daily use of individual skin cancer preventive strategies among those who were able to name the strategy independently

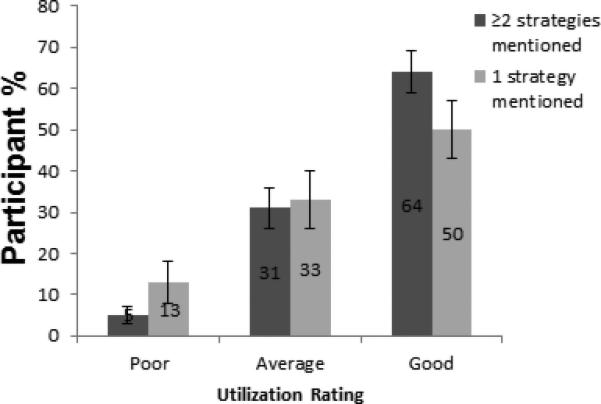

Participants were then asked to rate their adherence to any of the recommended skin cancer strategies as poor, average or good. Subsequently, the self-rating was compared to how many strategies each participant was able to name. Participants who were aware of 2 or more strategies had the best self -rating of utilization of those strategies. Sixty four percent (95% CI 59%-69%) of responders who mentioned two or more skin cancer prevention strategies rate their current behavior of utilizing those strategies as “Good” and 5% (95% CI 3%-7%) rate it as “Poor”; whereas only 50% (95% CI 43%-57%) of those who mentioned one strategy rate themselves as “Good” and 13% (95% CI 8%-18%) rate themselves as “Poor”. Participants who were only able to name one strategy had a lower percentage of a “Good” self- rating and higher percentage of a “Poor” self-rating compared to those who were familiar with multiple strategies. (See Figure 2)

Figure 2.

Self-rating of utilization of any skin cancer preventive strategy compared to how many strategies mentioned independently

Participants without prior NMSC had slightly higher percentage of sunscreen use (56% vs 44%), and lower percentages of clothing and hat use than those with recurrent disease. Also, participants with longer outdoor occupation activity did not have higher percentages of protective behaviors. (See Table 4)

Table 4.

Preventive behaviors among those with and without history of prior NMSC, and with and without occupation outdoors

| Sunscreen use n=34 (%) (95% CI) | Hat use n=47 (%) (95% CI) | Clothing use n=19 (%) (95% CI) | |

|---|---|---|---|

| History of prior NMSC n=80 | 15 (44) (27-60) | 24 (51) (37-65) | 12 (63) (41-85) |

| No history of prior NMSC n=60 | 19 (56) (39-73) | 23 (49) (35-63) | 7 (37) (15-59) |

| Occupation with > 1 hour outdoor n=60 | 15 (44) (27-60) | 24 (51) (37-65) | 8 (42) (20-64) |

| Occupation with < 1 hour outdoor n=80 | 19 (56) (39-73) | 23 (49) (35-63) | 11 (58) (36-80) |

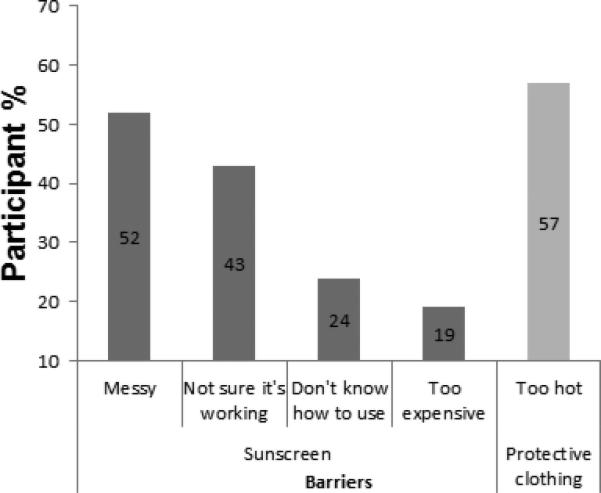

Barriers to Utilization

The most commonly cited reason for not using sunscreen was messiness of application. Of those participants with no current sunscreen use (n=21), 52% (n=11) said it was too messy and oily, followed by 24% (n=5) not being sure that it actually works. Out of the participants who mentioned wearing protective clothing as a skin cancer prevention method (n=49), over half (57%) did not actually wear the clothing because they believed they would be too hot if their skin was covered while outside in the sun. (See Figure 3)

Figure 3.

Barriers to utilization of sunscreen and protective clothing among those not using either strategy

Discussion

Our single center prospective cohort study revealed suboptimal knowledge and utilization of sun protective strategies amongst patients undergoing Mohs micrographic surgery for non-melanoma skin cancer, including those with immunosuppression. Multiple barriers to effective sun protection were identified, namely conflicting sources of information, inadequate patient education, expensive products and difficult application. Patients may be exposed to conflicting information regarding the safety and efficacy of sunscreens and other protective strategies from internet and media sources. About half of our patients utilized these resources to find information on skin cancer and prevention strategies. Given that a high proportion of medical websites contain notable inaccuracies and omissions, patients may encounter confusing or misleading information that dissuade them from proper sun protection.20,21 Moreover, in the US an analysis of skin cancer related articles between 1979 and 2003 found that the articles tended not to focus on important educational information like prevention and self-detection, but more on treatment leaving the readers uninformed about the important behaviors of primary prevention.22 Indeed, a significant portion of patients believed that sunscreens were ineffective, which may contribute to the low rate of use of sunscreens. Accurate and comprehensive patient education will improve sun protection amongst at risk patients. Those patients in our study that can cite two or more different sun protection strategies are more likely to practice at least one of those strategies daily. Although sunscreens are the most frequently taught strategy, it is also the least utilized because of cost, difficulty of application, and conflicting data on effectiveness. On the other hand, even though fewer patients were educated on wearing hats, those who were aware of them used hats more consistently than any other protective strategies. Cost and ease of use can affect utilization rate of sun protective strategies, and thus should be taken into account when discussing these strategies with patients. In order to close the gap between knowledge and practice, counseling on sun safety strategies should be targeted to fit the age, socioeconomic status and lifestyle of each patient. Our study results show that older generations prefer protective clothing to sunscreen use; younger generations, however, may need more counseling on decreasing exposure to artificial UV via tanning booths and increasing sunscreen use in daily moisturizers and cosmetics.

Our results concur with prior studies showing that knowledge regarding skin cancer preventative strategies remains limited.23 There is still a significant gap in knowledge about skin cancer and its prevention, even among those patients diagnosed with and receiving treatment for the disease. Therefore, one cannot assume that these patients have already had adequate education about skin cancer prevention. The message of skin cancer prevention must be re-enforced and re-introduced at every healthcare encounter by all providers in order to be effective. Our data also suggest that immunosuppressed patients did not have better knowledge or higher rate of utilization of sun protective strategies despite having a significantly increased risk of skin cancer. These findings are consistent with prior studies showing minimal change in sun protective behavior in patients before and after organ transplant. A higher proportion of immunosuppressed patients cited their physicians as a main source of knowledge on skin cancer and sun protection compared to healthy patients, possibly reflecting more frequent encounters with healthcare providers and more patient education by those physicians. This may be illustrated by our results showing that immunosuppressed are better at recognizing skin cancer and are more informed than their healthy counterparts on skin self-examination. Multifactorial education approach is necessary in order to increase adherence to preventive strategies among immunosuppressed patients. A previous study by Glanz et al. showed that compared to only receiving general skin preventive materials, providing personalized feedback and risk assessments to individuals at high risk of developing skin cancer was related to improved sun-protective behavior.24 Hence, immunosuppressed patients will likely benefit from an early, intensive, and customized skin cancer prevention screening in adjunct to their immunosuppression therapy. Ancillary staff, nurses, and medical students can often assist with routine sun protection discussions with patients. Given that a significant portion of participants identified media as a prominent source of knowledge, incorporation of online guidelines which clearly describe skin cancer risks and preventive strategies can save time during office visits and over time improve patient adherence.

Our study design was a cross-sectional analysis of patients at a single academic center with wide referral network from multiple disciplines. We had a good representation of immunosuppressed patients with a slight gender discrepancy of more men than women, reflecting the general epidemiology of NMSC in which men have a two to three times higher rate of NMSC than women.25 The immunocompromised status of our participants was not validated with a chart-review. Therefore, if patients fail to identify themselves as immunocompromised, the misclassification can bias our data toward the null, i.e. failure to detect significant differences between the healthy and immunocompromised groups. Patients in this cohort may also have had more healthcare encounters and thus more opportunities for patient education given the referral system and metropolitan setting of our institution.

National cancer surveys have demonstrated a “north-south gradient” of increasing incidence of cutaneous squamous cell carcinoma (CSCC) in the United States.26 Based on UV index climatological means, San Diego, with a UV index mean of ≥7, is grouped with southern and central US which have been found to have a higher incidence of CSCC as compared to northern US. With this background of sun exposure, our cohort may have a higher history of prior NMSC than patients from the northern states. In addition, we may also have a higher percentage of patients with outdoor occupations and leisure activities. However, our results show that having prior NMSC doesn't increase protective behavior and the same held true for people with outdoor occupation. Thus, although our cohort may have a higher baseline of participants with recurrent NMSC and outdoor occupations, we don't anticipate a significant difference in protective behaviors in either subgroups as compared to the general population. Lastly, as residents of San Diego, our participants may have been exposed to more sun protective education than residents of other lower UV index regions. Thus, our data may overestimate knowledge and possibly utilization compared to studies in areas with lower sun exposure and lower incidence of NMSC. Nevertheless, our data still demonstrates a clear and significant gap in knowledge despite this potential bias.

In the future, we plan on expanding our analysis to include questions regarding the attitudes and concerns of patients toward skin cancer as such can influence the level of preventive behavior. Future research is necessary to develop skin cancer prevention educational tools that are easy to implement, effective in bridging the gaps in patient knowledge, and able to improve patient adherence to sun protective strategies.

Footnotes

Institution where work was performed:

University of California, San Diego

Dermatologic Mohs Surgery Center

Contributor Information

Alina Goldenberg, School of Medicine, University of California- San Diego

Bichchau Thi Nguyen, Procedural Dermatology Fellow, Department of Dermatology, Brigham and Women's Hospital, Boston, Massachusetts

Shang I Brian Jiang, Director of Mohs Micrographic and Dermatologic Surgery, Associate Clinical Professor in the Division of Dermatology, University of California- San Diego

References

- 1.Rogers HW, Weinstock MA, Harris AR, et al. Incidence estimate of nonmelanoma skin cancer in the United States, 2006. Archives of dermatology. 2010;146:283–7. doi: 10.1001/archdermatol.2010.19. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Saladi RN, Persaud AN. The causes of skin cancer: a comprehensive review. Drugs of today (Barcelona, Spain : 1998) 2005;41:37–53. doi: 10.1358/dot.2005.41.1.875777. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Eide MJ, Weinstock MA. Public health challenges in sun protection. Dermatologic clinics. 2006;24:119–24. doi: 10.1016/j.det.2005.08.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.National Health Interview Survey of topics related to cancer epidemiology. National Center for Health Statistics; Hyattsville, MD: 1992. [Google Scholar]

- 5.Halpern AC, Kopp LJ. Awareness, knowledge and attitudes to non-melanoma skin cancer and actinic keratosis among the general public. International journal of dermatology. 2005;44:107–11. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-4632.2005.02090.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Armstrong AW, Watson AJ, Makredes M, Frangos JE, Kimball AB, Kvedar JC. Text-message reminders to improve sunscreen use: a randomized, controlled trial using electronic monitoring. Archives of dermatology. 2009;145:1230–6. doi: 10.1001/archdermatol.2009.269. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Berg D, Otley CC. Skin cancer in organ transplant recipients: Epidemiology, pathogenesis, and management. Journal of the American Academy of Dermatology. 2002;47:1–17. doi: 10.1067/mjd.2002.125579. quiz 8-20. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Hartevelt MM, Bavinck JN, Kootte AM, Vermeer BJ, Vandenbroucke JP. Incidence of skin cancer after renal transplantation in The Netherlands. Transplantation. 1990;49:506–9. doi: 10.1097/00007890-199003000-00006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Jensen P, Hansen S, Moller B, et al. Skin cancer in kidney and heart transplant recipients and different long-term immunosuppressive therapy regimens. Journal of the American Academy of Dermatology. 1999;40:177–86. doi: 10.1016/s0190-9622(99)70185-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Adamson R, Obispo E, Dychter S, et al. High incidence and clinical course of aggressive skin cancer in heart transplant patients: a single-center study. Transplantation proceedings. 1998;30:1124–6. doi: 10.1016/s0041-1345(98)00178-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Herman S, Rogers HD, Ratner D. Immunosuppression and squamous cell carcinoma: a focus on solid organ transplant recipients. Skinmed. 2007;6:234–8. doi: 10.1111/j.1540-9740.2007.06174.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Muhleisen B, Petrov I, Gachter T, et al. Progression of cutaneous squamous cell carcinoma in immunosuppressed patients is associated with reduced CD123+ and FOXP3+ cells in the perineoplastic inflammatory infiltrate. Histopathology. 2009;55:67–76. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2559.2009.03324.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Rowe DE, Carroll RJ, Day CL., Jr Prognostic factors for local recurrence, metastasis, and survival rates in squamous cell carcinoma of the skin, ear, and lip. Implications for treatment modality selection. Journal of the American Academy of Dermatology. 1992;26:976–90. doi: 10.1016/0190-9622(92)70144-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Weimar VM, Ceilley RI, Goeken JA. Aggressive biologic behavior of basal- and squamous-cell cancers in patients with chronic lymphocytic leukemia or chronic lymphocytic lymphoma. The Journal of dermatologic surgery and oncology. 1979;5:609–14. doi: 10.1111/j.1524-4725.1979.tb00732.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Silverberg MJ, Leyden W, Warton EM, Quesenberry CP, Jr., Engels EA, Asgari MM. HIV Infection Status, Immunodeficiency, and the Incidence of Non-Melanoma Skin Cancer. Journal of the National Cancer Institute. 2013;105:350–60. doi: 10.1093/jnci/djs529. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Flegg PJ. Potential risks of ultraviolet radiation in HIV infection. International journal of STD & AIDS. 1990;1:46–8. doi: 10.1177/095646249000100111. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Reichrath J, Nurnberg B. Solar UV-radiation, vitamin D and skin cancer surveillance in organ transplant recipients (OTRs). Advances in experimental medicine and biology. 2008;624:203–14. doi: 10.1007/978-0-387-77574-6_16. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Skiveren J, Mortensen EL, Haedersdal M. Sun protective behaviour in renal transplant recipients. A qualitative study based on individual interviews and the Health Belief Model. The Journal of dermatological treatment. 2010;21:331–6. doi: 10.3109/09546630903410166. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Szepietowski JC, Reich A, Nowicka D, Weglowska J, Szepietowski T. Sun protection in renal transplant recipients: urgent need for education. Dermatology (Basel, Switzerland) 2005;211:93–7. doi: 10.1159/000086435. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Lawrentschuk N, Sasges D, Tasevski R, Abouassaly R, Scott AM, Davis ID. Oncology health information quality on the Internet: a multilingual evaluation. Annals of surgical oncology. 2012;19:706–13. doi: 10.1245/s10434-011-2137-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Robinson JK, Alam M, Ashourian N, et al. Skin cancer prevention education for kidney transplant recipients: a systematic evaluation of Internet sites. Progress in transplantation (Aliso Viejo, Calif) 2010;20:344–9. doi: 10.1177/152692481002000407. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Stryker JE, Solky BA, Emmons KM. A content analysis of news coverage of skin cancer prevention and detection, 1979 to 2003. Archives of dermatology. 2005;141:491–6. doi: 10.1001/archderm.141.4.491. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Renzi C, Mastroeni S, Mannooranparampil TJ, Passarelli F, Caggiati A, Pasquini P. Skin cancer knowledge and preventive behaviors among patients with a recent history of cutaneous squamous cell carcinoma. Dermatology (Basel, Switzerland) 2008;217:74–80. doi: 10.1159/000127389. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Glanz K, Schoenfeld ER, Steffen A. A randomized trial of tailored skin cancer prevention messages for adults: Project SCAPE. American journal of public health. 2010;100:735–41. doi: 10.2105/AJPH.2008.155705. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Lewis KG, Weinstock MA. Trends in nonmelanoma skin cancer mortality rates in the United States, 1969 through 2000. The Journal of investigative dermatology. 2007;127:2323–7. doi: 10.1038/sj.jid.5700897. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Karia PS, Han J, Schmults CD. Cutaneous squamous cell carcinoma: estimated incidence of disease, nodal metastasis, and deaths from disease in the United States, 2012. Journal of the American Academy of Dermatology. 2013;68:957–66. doi: 10.1016/j.jaad.2012.11.037. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]