Abstract

We examine the use and value of fertility intentions against the backdrop of theory and research in the cognitive and social sciences. First, we draw on recent brain and cognition research to contextualize fertility intentions within a broader set of conscious and unconscious mechanisms that contribute to mental function. Next, we integrate this research with social theory. Our conceptualizations suggest that people do not necessarily have fertility intentions; they form them only when prompted by specific situations. Intention formation draws on the current situation and on schemas of childbearing and parenthood learned through previous experience, imbued by affect, and organized by self-representation. Using this conceptualization, we review apparently discordant knowledge about the value of fertility intentions in predicting fertility. Our analysis extends and deepens existing explanations for the weak predictive validity of fertility intentions at the individual level and provides a social-cognitive explanation for why intentions predict as well as they do. When focusing on the predictive power of intentions at the aggregate level, our conceptualizations lead us to focus on how social structures frustrate or facilitate intentions and how the structural environment contributes to the formation of reported intentions in the first place. Our analysis suggests that existing measures of fertility intentions are useful but to varying extents and in many cases despite their failure to capture what they seek to measure.

Each pair of statements below is true for the contemporary U.S.:

-

Fifty percent of pregnancies (and 35% of births) are unintended (Finer and Henshaw, 2006; Martinez, et al., 2006);

and

Intentions are the strongest predictor of a woman’s subsequent fertility behavior (Westoff and Ryder 1977; Schoen et al, 1999).

-

Among birth cohorts of women recently completing childbearing, women missed their stated intentions (at age 22) by an average of nearly one birth (Morgan and Rackin 2010)

and

Recent birth cohorts’ mean intentions (at age 22) exceed only slightly their average completed fertility (at age 40; Quesnel-Vallée and Morgan 2004; Morgan and Rackin 2010).

While not irreconcilable, the first statement in each pair suggests a more modest role of fertility intentions (on fertility behavior) than the second one. Demographers have debated the value and role of fertility intentions for decades (Klerman, 2000; Morgan 2001; Schoen et al 1999; Luker, 1999). But demographers cannot be divided into those that value them and those that do not. Instead the literature suggests an ongoing struggle to come to terms with the seemingly obvious importance of fertility intentions and the shortcomings of current conceptualizations. In this paper, we reconcile the above statements by addressing some conceptual shortcomings in the fertility intentions literature. More specifically, we examine the value of fertility intentions for fertility research against the backdrop of theory and research in the cognitive and social sciences.

In the first half of the paper we develop a cognitive-social model of intentions. We begin by summarizing research, drawn from recent brain and cognitive science, on the automatic and deliberative mechanisms through which cognition occurs. We then summarize insights about social structure and its relation to cognition and behavior from social theory, drawing in macro-historical concepts (see Johnson-Hanks et. al. 2011). Especially important is William Sewell’s (1992, 2005) conceptualization of the “duality of structure” that posits an ongoing macro-level interaction of virtual (or schematic) mental frames with the material objects that instantiate social institutions. Our proposed model of intentions integrates these cognitive and social theories, elaborating their implications for conceptualizing how intentions are formed and their relation to cognitive processes, behavior, and environmental structures. We theorize intentions in terms of two dualities at two levels of analysis: (1) the interplay of automatic and deliberative processes in the brain and (2) the interplay of virtual (ideational) structures and their instantiations in the material world.

The second half of the paper explores the implications of our model for research on fertility intentions and fertility. After addressing the relationship between fertility intentions reported on demographic surveys and the psychological concept of intention, we demonstrate that our model expands our understanding of the strong but imperfect relationship between fertility intentions and actual fertility behavior at both the individual and aggregate levels.

Conceptual Foundation: Insights from Cognitive Science and Social Theory

We define intentions as in the psychological literature: intentions are complex mental states in which there is a desire for some outcome, a belief that taking a particular action will lead to that outcome and some degree of commitment to perform the action (Malle et al., 2003). Fishbein and Ajzen (2010) have developed a model of intentions – the Theory of Reasoned Action (TRA) – that has dominated research in psychology and demography for decades. In this model, “intentions” are consciously developed and draw on other mental constructs such as attitudes, desires, and beliefs. Fishbein and Ajzen acknowledge that intentions are socially influenced: intentions are a function of not only the individual’s attitudes and beliefs but also the subjectively perceived attitudes and beliefs of others. TRA views all behaviors as intended in some sense and intentions as a necessary mediator between other mental constructs and behavior. Intentions are most predictive of behaviors when they are proximate to the context of action and target specific actions.

Insights from Cognitive Science

TRA has been widely used in fertility research1 and has proven useful in many substantive areas2. However, as argued elsewhere (Morgan and Bachrach, 2011; Bachrach and Morgan, 2011), recent developments in cognitive science challenge one of its key features – most notably the assumption that the formation of conscious intentions to act precede all behaviors3. We discuss the evidence against this assumption in a later section. Here, we provide necessary background by outlining three major insights drawn from contemporary cognitive science and neuroscience and combining them into a simplified model of cognitive processes in the brain.

1. Cognition depends on two types of processes in the brain

We label these deliberative and automatic processes.4 Deliberative processes include those brain functions that we are most familiar with – reasoning, making decisions, simulating future courses of action, and controlling impulses. These are largely conscious and correspond to what we think of as rational thought and free will. Automatic processes in the brain occur outside consciousness. These have a broad range of capabilities: they can sense incoming stimuli, direct attention to what is important, interpret environmental cues, learn new information and store it in memory, retrieve information, produce appropriate action, and even pursue goals (Bargh and Morsella 2008, Gazzaniga 2011). Even complex culturally derived actions, like driving a car, can be largely consigned to automatic processes once they are learned (Evans 2008). Unconscious brain mechanisms do most of the brain’s work and provide the raw material that informs conscious decisions, but deliberative thought can override and redirect automatic processes (Kahneman, 2011). The two brain systems are therefore deeply intertwined and mutually dependent; little of the brain’s action, including the formation of intentions, can be understood without reference to both (Lieberman, 2007; Donald, 2002).

2. The brain automatically creates mental representations of the world and one’s relation to it

One of the major functions of the unconscious brain is to develop mental representations of the body and its interactions with the environment. This is done on an ongoing basis, largely through automatic processes that represent sensory inputs in the brain, integrate them to produce complete images, and associate the images with meanings (Damasio 2010). These processes produce patterns of connectivity among neural structures that store5 knowledge about the self and those aspects of the world that are relevant for survival and well-being. We use the term “schema” to refer to the elements of meaning that comprise this body of knowledge (Strauss and Quinn 1997; Johnson-Hanks et. al. 2011: 2–8).6,7 In cognitive science, a schema is defined as a relatively stable and abstract representation of the meaning of an object or event (DiMaggio 1997; Mandler 1984). Schemas can represent concepts (for example, the concept of a family) or actions appropriate to particular contexts (for example, using a condom with a new partner). Schemas are linked in neural networks in patterns of interconnectivity that reflect their interdependencies in our experience. Thus, for example, traditionally the schema for “children’s daycare” was more closely connected to “motherhood” (or mother’s work) than it is to “fatherhood” (or father’s work).

Once established in neural networks, cues from the environment or our own deliberative thought can trigger the activation of schemas, possibly but not necessarily at a conscious level (Strauss and Quinn, 1997; Damasio, 2010). At one extreme, successful reiteration(s) of a schema can legitimate and strengthen it, making it appear non-ideological and noncontroversial. Such “(u)ncontested schemas, hegemonic ones, are experienced as normal and transparent modes of being or acting—not as options, but as “just the ways things are” (Johnson-Hanks et. al. 2011:6).

3. Schemas are imbued with sensation and feeling and may be linked strongly (or not) to a person’s identity or sense of self

Schemas do not simply represent cold facts or definitions. Research on “embodied cognition” has shown that schemas are grounded in representations of the sensory, somatic and affective states registered by the brain as we learn and reproduce them (Damasio, 2010; Ignatow, 2007; Smith 1996). The schema for “baby,” then, might engage an abstract notion of a recently born organism as well as the sound and image of the word baby, but it will surely engage visual images of a round face and tiny toes, the feel of soft skin, and perhaps also that distinctive baby smell. It will also engage feelings we have had in encountering babies: did we melt with pleasure or fear dropping them? These feelings and sensations, experienced over time in our encounters with babies, help to position the schema in relation to the neural networks in the brain that represent the self. One is more likely to hold an image of the self as a future mother if one’s schema for baby is positive, warm and cuddly than if it suggests images of possible failure. The self can be thought of as a set of schemas (self-representations) that characterize what and who we are in relation to the world. These neural structures are deeply embodied, being linked to and grounded in basic somatic sensations of continuity, individuality, and ownership of our own experience and actions (Damasio 2010). Images that are closely linked to the sense of self, in turn, have motivational force (Foote 1951, Hitlin 2003, Strauss and Quinn 1997).

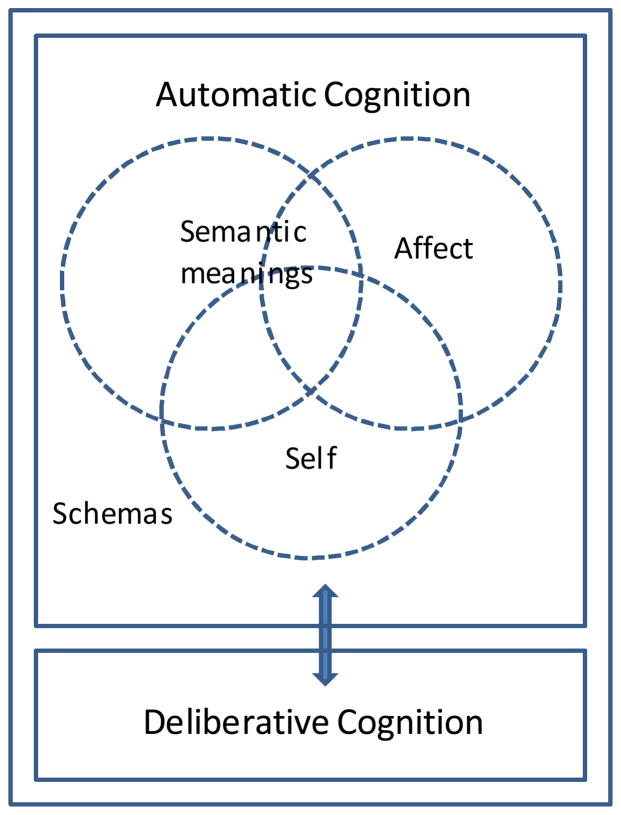

Figure 1 summarizes the key features of our simplified model of cognition. Automatic processes in the brain create representations of the individual’s experience of the environment. These representations form a network of schemas, each of which captures the semantic meaning of a common object, action, or concept; the feelings or affect associated with it, and its salience to the self. Through this mapping process, the brain prepares itself to interpret the meaning, affective value, and personal significance of incoming environmental cues. Deliberative processes, such as impulse regulation and reasoning, complement and interact with the automatic processes. Deliberative processes draw from the information about meaning, affect, and self-relevance that is provided through automatic cognition, but can also reshape cognitive mappings. For example, a first time mother may have genuine and legitimate fears about childbirth. But when they arise she substitutes new knowledge that she has learned about childbirth, from a childbirth class for instance. After repeated substitutions, the initial fear reaction is unconsciously supplanted by a schema reflecting the normalcy of childbearing and its safety.

Figure 1.

Cognition: Dual Processes in the Brain

Insights from Social Theory

Of course, cognitive function does not operate in a vacuum. Where do all these schemas come from and how are they connected with affect and motivation? While some basic schemas are innate (Gazzaniga 2011, Miller & Rodgers 2001), most are learned through interactions with our environments (Damasio 2010). And because we are first and foremost social animals, our environments are predominantly social and socially structured. How can social theory add to our model of cognitive function?

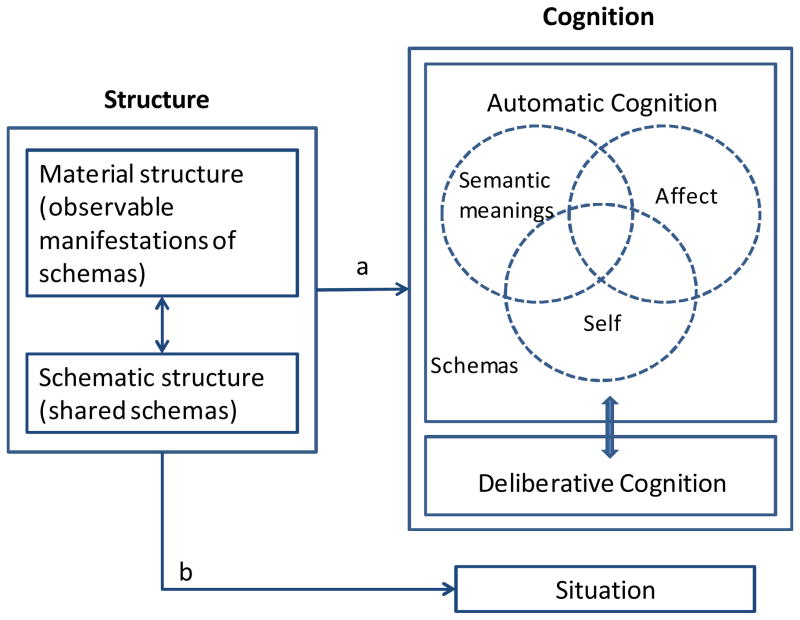

Social structures are durable forms of organization, patterns of behavior, or systems of social relations (Johnson-Hanks et al. 2011; see also, e.g., Parsons 1949; Radcliffe-Brown 1932; Sahlins 2000). Structures are dual in nature (Sewell, 1992, 2005; Giddens 1979). As the left-hand box in Figure 2 illustrates, social structures emerge from the interplay of observable material structures on the one hand (e.g., objects, speech, observable behaviors, and built environments) and the schematic meanings that material forms instantiate on the other (e.g., values, beliefs, norms, scripts, and ways of categorizing). For example, one aspect of the motherhood structure depends both on the idea that being a parent conveys status and love and also on the presence of material objects or actions that instantiate the idea (e.g., people treating mothers with respect and Mother’s Day cards). Another aspect may depend mutually on ideas about investment in children (e.g, that good parents teach their child skills, like numeracy) and the marketing of early learning toys and programs (e.g., advertising claims that a product will facilitate numeracy). Schematic and material structures are deeply interdependent in their construction and reconstruction of social life, but neither one is totally dependent on the other, and each can change independently of the other.

Figure 2.

The Effects of Structure

Social structures impact cognition (and behavior) in two important ways. The first we discussed in the previous section: Over time, neural networks (i.e., schemas) are structured by recurrent, similarly patterned experience (DiMaggio 1997; McClelland, McNaughton & O’Reilly, 1995, Strauss and Quinn, 1997). Such regularities of experience are produced by structures. Through interaction with the people, things, and events that provide material evidence of the structures that shape our social lives, schemas representing the ideas, scripts, and values associated with particular structures take form in our neural networks. Path a in Figure 2 illustrates this influence. For example, we learn that the birth of a baby is cause for celebration by observing others as they celebrate a baby’s birth, as well as from public displays of cards and gifts for new babies (cf. Bandura, 1977). Learning the meanings and affective values associated with childbirth prepares us to interpret new information about a birth appropriately and to reproduce expected behavior with greater or less fidelity. Our responses and behaviors become part of the social environment, thereby reinforcing and/or modifying the material instantiation of childbirth schemas in the world.

Second, particular structures become important for action and decision-making when they are relevant to a specific context or situation.8 Structures organize the material features of a situation: the patterns of opportunity and constraint that shape action in a particular context (see path b in Figure 2). They also influence how individuals construe a particular situation. By structuring the material circumstances of particular situations, structures influence the cues that evoke particular schemas in the participant’s brain. Thus, structures shape what McNicoll (1980) calls the “decision environment:” the frames of reference or schemas through which the individual attaches meaning to a situation (what is going on?), identifies potential courses of action (what could I do?), and chooses among them (what will I do?). For example, consider two women experiencing an unwanted pregnancy at a university: one belongs to a highly religious family and is attending a Catholic University, and the other, from a nonreligious family, is attending a private secular university. Although the situations faced by the two women are similar in some respects (the unwanted pregnancy), they differ markedly in others. The first woman will not likely receive help from her family or student health services in obtaining an abortion and could face material sanctions (expulsion from school, alienation from family) if she persisted in ending the pregnancy. In addition, her family may provide material and emotional support for having the baby. On the other hand, if the second woman considered abortion, she might well receive financial help and emotional support from family and easily access services through the student health services; she might also face sanctions from her family and school if she carried the baby to term. These women are embedded in different structures, and the structures imply very distinct sets of material resources and constraints. These settings also provide very different sets of cues for construal. Thus, different structures transform a similar event into very different situations.

People’s experience with social structures can vary greatly. An individual’s experience of structures (both over time and in current situations) depends on his or her location within society (McPherson 2004), and encountering different structures can produce differences across persons in both mental maps and in the situational cues they experience (thus influencing construal). Specifically, individuals are located within society along socially meaningful dimensions such as age, sex, income, and education. Many structures are differentially distributed across this multi-dimensional social space: two-biological-parent intact families are more common among the college-educated; welfare systems mainly impact poor populations. Thus, exposure to and identification with specific structures and the material and schematic components of which they are made depends on a person’s position – ascribed, achieved, or chosen – within social space as well as his or her position in geographic space (Johnson-Hanks, et al., 2011).

Intentions: A Cognitive-Social Model

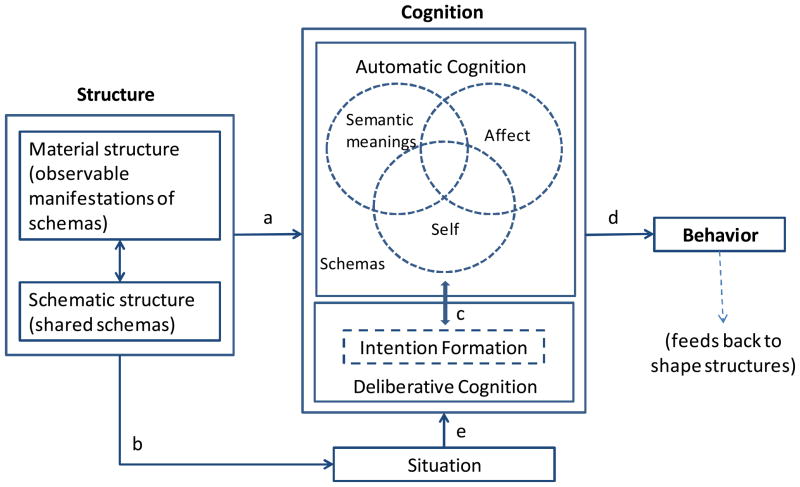

What do these ideas from cognitive science and social theory suggest about intentions? We offer the following propositions that build on, but expand and modify, the classical psychological model. Figure 3 codifies our model of intentions.

Figure 3.

A Cognitive-Social Model of Intentions

First, returning to our definition, intentions entail a desire for an outcome and a belief that a certain action will bring it about. Thus, we suggest that a woman forming an intention to become a mother would usually have a schema of parenthood associated with positive affect. 9 She would also have a mental script for becoming a mother – a set of schemas that linked particular actions to conceiving and bearing a child. Having a desire for the outcome implies that the relevant schemas are not only positively valued but linked to the self in some way, perhaps as part of an image of a potential future self. This linkage does not necessarily imply intention, however, because it may occur automatically, without conscious deliberation.

Intention formation requires not only conscious deliberation but also some degree of commitment to act (Fishbein and Ajzen; 2010; Malle et al., 2003). We suggest that an intention is formed when the deliberative brain consciously ties both a schema for an outcome and the schemas for achieving the outcome to the self, thereby motivating action.10 For example, the conscious commitment to become a parent automatically establishes a firmer connection among schemas related to parenthood, the action schemas necessary to achieve it, and the self. Further, the attachment of the parenthood and action schemas to the self intensifies their affective content. Because action is produced by emotional cues (LeDoux 2002), this strengthens their power to motivate action. The bi-directional path c at the center of Figure 3 thus shows deliberative systems of the brain both drawing on the schemas, affect, and self-representations created through automatic processes and strengthening associations among these elements. In the short term, the brain stores the intention in a temporary holding area, but these representations will fade over time. With enough reinforcement, however, the intention will be integrated in the neural networks that manage long-term memory (McClelland, McNaughton & O’Reilly, 1995). In this way, conscious goals can become learned and implemented by automatic systems.

Second, as represented by path d in Figure 3, our model suggests that action relevant to an outcome need not depend on the individual forming a prior intention. There are two reasons for this. Cognitive science has shown that while we generally become aware of our actions, action may precede not only conscious deliberation but also awareness (Gazzaniga 2011, Libet et al. 1983). If the schemas described above link certain actions to motherhood and if they are positively integrated in the self, then they can produce action when triggered by environmental cues even in the absence of conscious deliberation. For example, a woman who holds very positive images of motherhood (or who is fervently pro-life) may not ever think about the possibility of abortion when faced with an unintended pregnancy.11

The other reason that relevant intentions need not precede action is that actions may be relevant to multiple outcomes (Barber 2001), so that intentional action directed at one outcome will have consequences for others. If I form an intention to take action a1 to obtain outcome o1, and if a1 also produces outcome o2, then o2 will be an unintended consequence of my action. Further, if o1 affects the probabilities of yet other outcomes, these too may occur in the absence of any intention. Having sexual intercourse with an attractive partner may be driven by schemas of and intentions related to relationship formation. Nevertheless, sexual intercourse satisfies a precondition for pregnancy and parenthood.

Third, if an intention is formed, it is likely to influence not only action directed at the specific outcome it targets, but also the organization and affective content of schemas directly and indirectly related to the intention. Because our neural networks link schemas together, the changes to the schema associated with a particular action or outcome may have ripple effects that modify related schemas (Smith, 1996). For instance, the intent/decision to accept a demanding job may strengthen schemas that encourage and justify fertility postponement. Alternatively, the intent/decision to become a parent could weaken a persons’ attachment to a particular job or to the labor force.

Fourth, intentions are framed by structure (path a in Figure 3). This proposition follows from the fact that the schemas we learn and use most reliably are those that we learn from observing recurring patterns of social life (i.e., schemas represented materially in the world) – the very essence of structure. Because we are exposed to these schemas repeatedly and learn them so thoroughly, they become the taken-for-granted baseline assumptions for intention formation. This does not mean that intentions will always mirror the dominant structural patterns, but it does mean that intentions are formed in relation to a structured world. For instance, most persons would acknowledge the norm that one should become a parent and that one should have a second child to provide a sibling for the first born. Of course not all persons have exactly two children, but rationales for other family sizes are frequently couched as reasonable exceptions to this widely accepted schema. Structure also frames intention formation by shaping the circumstances that prompt it. The material cues present in structured situations elicit schemas (via construal) that will produce intentions appropriate to the situation (Miller 2011).

Fifth, we form intentions only when the circumstances of a situation demand or motivate it (path e in Figure 3). The formation of intentions requires the action of deliberative processes, and these processes are costly to the brain. They engage only when necessary, generally when automatic processes are not producing a coherent story or direction for action (DiMaggio 1997, Kahneman 2011). This is especially likely when people confront new or unexpected situations or choices requiring tradeoffs between similarly valued options. Incoherence generates confusion or a sense of conflict, which in turn requires deliberation and a conscious decision on how to act. This view of intention formation is similar to that suggested by Ní Bhrolcháin and Beaujouan (2012), who draw on psychology and behavioral economics in their analysis of fertility intentions. They suggest that fertility preferences are “constructed” rather than retrieved, especially in the context of unfamiliar circumstances or those that require tradeoffs.

An unplanned pregnancy is an example of a situation that will usually trigger the formation of fertility intentions. The schemas evoked by this event are likely to be in conflict. Even among women who welcome it, an unexpected pregnancy will throw existing representations of the future life course into conflict with schemas representing the impact of a new baby. The brain will invoke deliberative processes to resolve the confusion, and intentions will be formed – sometimes with ease and sometimes only after extended and painful deliberation. Our claim that the formation of intentions depends on motivating situations also extends to women who form fertility intentions well in advance of pregnancy. A marriage, learning that one’s current partner has decided to be voluntarily childless, or committing oneself to a challenging career: these situations bring parenthood structures into awareness in ways that may evoke the formation of intentions. Without such motivating situations, there is no reason to invest in intention formation.

Our model is highly compatible with the TRA model in most respects. Both models account for the influence of social structure and experience on cognitive processes and behavior. The beliefs, attitudes and norms featured by TRA can be conceptualized as schemas (see footnote 7) in our model. The main conflict between the two is in whether conscious intention formation must precede behavior: TRA assumes it must, whereas we posit that behavior can occur in the absence of a relevant intention. In TRA the causal path between intention and behavior is modified by variables that reflect an individual’s “control” – their ability to bring actions into line with intentions. Because our model is grounded in cognitive science on how the brain produces action, these modifiers are unnecessary. The individual and situational constraints and enablers that influence control in TRA are incorporated into the production of behavior via the cognitive processes at the core of our model. Finally, our model also goes further in key ways: we make explicit the dual (material-schematic) nature of structures in the environment and their relation to cognition via multiple pathways; we also tie our model directly to knowledge about dual processes (automatic and deliberative) in cognition.

Using our Model to Reconcile What We Know about Fertility Intentions

How does re-visiting the intentions concept in the light of cognitive science and macro social theory help reconcile the seemingly contradictory facts we introduced at the outset? These facts suggest three questions:

Why is there so much slippage between intentions and fertility outcomes?

Why do fertility intentions predict fertility as well as they do?

What is the predictive value of intentions for fertility at the aggregate level?

Before we address these questions, however, we must clarify a fundamental issue regarding the measurement of fertility intentions.

Implications for measures of fertility intentions

Demographic research necessarily relies on survey reports of fertility intentions. These have an ambiguous relationship to intentions as defined by psychologists and as discussed above. Our discussion above implies that, at any given point in time, an individual may or may not have formed an intention regarding a particular outcome, and that, in fact, people do form intentions only when motivated in to do so. This argument suggests that fertility intention-making may be a stage in a longer developmental process (Ní Bhrolcháin and Beaujouan, 2012). We envision several stages (Harter 1999). In the first stage one learns about parenthood from one’s own experience of being parented and watching family life unfold in other families and through media portrayals. This builds a network of schemas in the brain about what families look like, how they function, what parents do, what makes a good parent, whether parent-child relationships are loving or conflicted, and so forth. The second stage, overlapping the first, is the organization of this knowledge in relation to mental models of the self and the self-to-be.12 The third stage is the conscious development of intentions. We suspect that the first stage begins in childhood, the second in adolescence, and the third in response to specific situations in the transition to, or during, adulthood.

This conceptualization has implications for our interpretations of data on fertility intentions or expectations collected in demographic surveys. Given the ubiquitous nature of families and the implications of fertility for adult roles and responsibilities, it is likely that most people do form fertility intentions at some point in their reproductive lives. However, they have not necessarily done so at the ages at which demographers begin asking them our questions (cf. Stevens-Simon, Beach and Klerman, 2001; Ní Bhrolcháin and Beaujouan 2011). Demographers’ questions about fertility intentions (and desires or expectations) almost always produce quantitative answers in western cultures. The survey context demands answers, and respondents will provide them. In some cases, the answers may reflect intentions; in other cases, scripts or cultural models imbued with positive affect and integrated into self-schemas (Hayford and Morgan 2008); in yet others, answers may simply reflect basic prototypes of a family – a mother, father and two children, for example – perhaps associated with positive affect but not deeply integrated into a schema of a future self. In the discussion that follows, we refer to the measures used by demographers as “reported intentions”, to distinguish them from the more specific psychological construct.

Why is there so much slippage between reported intentions and fertility outcomes?

One of the challenges of studying fertility through an intentions framework is that so many births occur without a prior intention (Finer and Henshaw, 2006). Some of these apparently result from intentional action – not using a condom to demonstrate trust for the partner or rejecting abortion on moral grounds – but these intentions are often grounded in schemas that are far afield from those that would give rise to what demographers think of as fertility intentions. A consideration of the proximate determinants of fertility provides a starting point for exploring these competing values and their effects on fertility outcomes. Much theorizing and empirical work treats fertility as the unitary outcome of interest; it is the dependent variable. A primary independent variable is the fertility intention. This produces the simple model (A) below:

| (A) |

Of course, other variables, z, can have direct or indirect effects as shown in (B):

| (B) |

But fertility results from a process that we represent using the heuristic from Davis and Blake (1956), where variables proximate to fertility are i) sexual intercourse, ii) conception and iii) carrying a pregnancy to term. Thus, models (A) and (B) become multidimensional, in the case of model (A):

| (C) |

Fertility is strongly influenced by actions, intentional or not, relating to having sex, using contraception, and carrying the birth to term. Where intentions relative to these actions exist, they may not accord directly with fertility intentions (or even the schemas that give rise to fertility intentions). Why? Our model suggests that patterns of association in neural networks are shaped by the external structures that frame social behavior and experience. We speculate that the schemas that underlie fertility intentions draw on structures related to parenthood and family, whereas those that inform intentions about sex, contraception, and abortion may be more closely associated with structures related to relationships, pregnancy, morality, and risk. Many observers have blamed our high rates of unintended pregnancy on the long-standing reluctance in our culture to discuss sexuality, pregnancy and contraception (Jones et al. 1985). While saturating the media with sex, we treat it as something apart from parenthood. In terms used by McNicoll (1980), schemas about parenthood and family, on the one hand, and sex and contraception, on the other, belong to separate “domains of consistency.” If these schemas aren’t linked in our experiences, they will not be closely linked in our mental maps, and won’t necessarily influence each other unless both domains are explicitly evoked by a situation.

There is also a second layer of multidimensionality if we acknowledge that a person’s life course encompasses a range of domains. For simplicity let’s identify four: fertility, education and work, leisure, and relationships. If we replace fertility in Model C above with these variables, and include in the diagram the intentions relating to each of them, the complexity of the model grows exponentially. As suggested previously, this means that schemas, intentions, and actions related to work, relationships, and leisure can influence fertility outcomes, just as those related to fertility can affect outcomes in other domains. The multiplicity of structures relevant to fertility implies that individuals encounter a great many situations in which action relevant to fertility must be taken. In many of these, the structures and schemas that underpin fertility intentions will not play a major role. Further, conflicts and complementarities among particular structures are likely to be accounted for when individuals form fertility intentions as a result of situations that are defined by those structures, making their conflicts and complementarities evident. They are less likely to be reflected in fertility intentions reported by individuals who have not yet formed intentions, or whose intentions were framed in situations not evoking the conflicting structures.

Beyond the issues raised by competing values and goals, our model suggests other reasons that weaken the link between reported fertility intentions and achieved fertility. What reported intentions represent may change over time. Before actual intentions have been formed, reported intentions likely reflect schemas of parenthood. The common observation in low fertility settings that behavior falls short of intentions (Bongaarts 2001; Morgan 2003; Quesnel-Vallée and Morgan 2004) may well reflect the move from general dispositions (that are generally favorable toward childbearing/children) to more concrete plans that require tradeoffs and costs. As Iacovou and Tavares (2011) show, the realities of lived experience, both in the formation and dissolution of partnerships and in the raising of children, account for most modifications of individual fertility intentions. Once formed, intentions can change in many ways. They can become less salient; they can change qualitatively (for example, moving from an emphasis on number of children to a desire for a child of a particular sex), or quantitatively -- increasing or decreasing the intended number of children (Hayford 2009). The opportunity for intentions to change depends on how proximate they are to action. When action is delayed, intentions can be easily diverted or superseded by other intentions drawing on other structures.

Why do reported fertility intentions predict fertility as well as they do?

Although inconsistency between intentions and actual fertility is commonplace at the individual level (Morgan and Rackin 2010), intentions are strong predictors of fertility when compared to other variables. The consensus is well-captured by Schoen et. al (1999:790): of all the variables examined “(o)nly marital status has an effect (on fertility) with a magnitude that is comparable with that of fertility intentions”. Moreover, intentions bring additional explanatory power and do not simply mediate the effects of more distal variables.

There are many reasons why reported intentions predict as well as they do. At a cognitive level, the schemas that inform the reporting of intentions in response to survey questions can influence action even when fertility intentions haven’t been formed (Miller 2011). Positive images of family life or of the self as a future parent can spill over to influence the value attached to schemas of action that are linked to parenthood schemas in the brain, such as getting married or continuing a pregnancy. Further, the schemas that inform survey reports of intended fertility will likely overlap substantially with the schemas that inform actual intention formation, making it likely that people’s responses to questions about fertility intentions will predict the intentions they later form. Once formed, fertility intentions can affect sexual, contraceptive and abortion behaviors in two ways: deliberative “proceptive” efforts to conceive (Miller 1986) or contraceptive action but, also, more gradually, by affecting the organization of neural networks so that the schemas associated with fertility behaviors are more closely tied to identity and more in alignment with the intentions. These changes make it more likely that persons will act on an intention.

From a macro perspective, the schemas underpinning reported intentions are learned through immersion in a particular social location characterized by particular material structures. Navigation of the environment gives rise to situations that elicit these schemas, reinforce them, and produce action that affects fertility outcomes. The tendency for people to remain embedded in particular structures over time enhances the continuity and reinforcement of these basic schemas and therefore the correspondence between reported intentions informed by them and later intention formation and behavior. For example, the only daughter of a professional couple is likely to hold schemas of adult work and family roles that reflect her upbringing and experience. These are likely to prompt a modest report of intended family size regardless of whether she has formed fertility intentions. Barring a youthful rebellion, the same set of schemas will guide her actions in attending college and beginning a career, making it likely that her completed family size will be similarly modest.

Social structures also support the development of realistic intentions (i.e., those more likely to be realized). As we suggested, intentions are formed in the context of situations that bring structures into ambiguous or conflicting relations to each other. Why is it, as the evidence suggests, that married women do hit their targets whereas unmarried women are more likely fall short of their intentions (Quesnel-Vallée and Morgan 2004; Morgan and Rackin 2010)? One reason is that being married places one in a structural position that brings parenthood to mind and increases the likelihood of situations supportive of or conducive to parenthood. Also, marriage increases the relevance of family-related schemas to the self. By doing so, it may trigger situations that bring conflicts between self-schemas related to work and parenthood into awareness, or situations that reveal an opportunity offered by the coincidence of structures (Johnson-Hanks 2005a; 2005b). Marriage also entails balancing the needs of both partners as well as potentially having children, putting existing self-schemas in doubt. These circumstances produce intentions that have been focused through the lens of intersecting structures that constrain and facilitate the married couple’s life.

What is the predictive value of intentions for fertility at the aggregate level?

One of the early uses of reported fertility intentions was to predict the completed fertility for cohorts still in the childbearing years. It was understood that individual women might miss this reported intention “low or high,” but it was hoped that individual-level errors would offset each other making the mean prediction close to the target. Because such offsetting does in fact occur, reported intentions are necessarily better predictors of actual fertility behavior at the aggregate level than at the individual level.

However, even aggregate reported intentions are imperfect at predicting aggregate behavio. In the U.S., recent cohorts completing childbearing have come close to meeting their expectations (that were recorded when these women were in their early 20s; Quesnel-Vallée and Morgan 2004; Morgan and Rackin 2010).13 But a common finding in other developed countries is that fertility is well below levels suggested by reported intentions. How can the framework we developed above help us to understand the relationship between fertility intentions and behaviors at the aggregate level?

Asking the question at the aggregate level focuses attention on social structure – are there regularities at this level and can we identify the mechanisms that produce them? In looking for macro-level explanations that explain aggregate differences, we are not denying micro-level decision making; we view macro-level dynamics as a product of the interaction of micro- and macro-level processes (Johnson-Hanks et al. 2011). However, we assume that the major influences on aggregate measures of fertility also operate, at least in part, at the aggregate level, and therefore are structural in our sense of the word. Thus, emphasis moves away from what happens in the brain to the structures in the world.

Structures shape both reported intentions and actual fertility, but not necessarily in the same ways. As we discussed previously, intentions are framed by structure and emerge from a developmental process. When people form fertility intentions, they draw on schemas learned and imbued with value through their experience with structures during childhood. As adulthood progresses and life course choices are made, intentions will be influenced by the contemporaneous structures that enter into these decisions, but this influence need not be powerful.14 Intentions refer to future behavior and the further off that future seems the greater the likelihood that contemporaneous structures that conflict or compete with long-standing schemas of parenthood will be discounted. At the aggregate level, a shared cultural model of a “best” sized family emerges, shaped in part by the structural characteristics of a contemporary time and place, but also deeply rooted in structures of the past.

Actual fertility is also motivated by the structures of the past, but because the timing of childbearing can be manipulated, it is more sensitive to current structural conditions. An existing but under-appreciated framework proposed by Bongaarts (2001; also see Morgan and Taylor 2006; Morgan and Rackin 2010) is quite useful in pointing to the structures that can drive aggregate fertility levels up or down. Here we develop the model as a cohort model focused on the net difference between reported intentions (in young adulthood) and behavior over the subsequent life course. 15 The model posits that aggregate behavior (mean children ever born, CEB) will mirror the cohort’s earlier aggregate reported intentions – absent unanticipated influences.

However, unanticipated factors will cause some women’s fertility to fall short of intentions (S) while others will cause intentions to be surpassed (P).

Components of S include fertility shortfalls due to sub- or infecundity and to competition with other goals/preferences. P includes unanticipated circumstances such as an infant death, an unsatisfying gender composition of one’s children, or an unwanted birth. Each leads to more births than stated intentions imply.

The impact of contemporaneous structures on actual fertility is most clearly evident in the components of S that reflect competing goals and preferences. Some women or couples may choose to postpone or forego births because they are engaged in a career or leisure activities that would be compromised by having more children (Barber 2001). Births that are postponed may eventually be foregone creating smaller family sizes than intended. The likelihood of “competition” (between family and other activities) depends upon a social environment where alternatives are available and acceptable or even encouraged. Synergies between family and other activities that could contribute to having more births than intended (P) also depend on the structural environment. For example, an expansion of day care facilities or policies encouraging their use through subsidies could advance the timing/number of births (Rindfuss et. al. 2010). At the aggregate level, shifts in the structures that define these conflicts and complementarities can have an important influence on cohort fertility rates.16

Other aspects of structure also influence the relationship between intentions and births through their effects on conceptions and fertility outcomes. For example, some groups may have more unwanted births than others because of the difficulty of obtaining an abortion or because it is less acceptable (Sklar and Berkov 1974; Morgan and Parnell 2002). Health care, religious, and governmental structures can also influence the level of unwanted births by restricting access to contraception or questioning its moral value. High levels of child mortality, themselves a function of health care structures as well as structures that shape poverty and disadvantage, may press actual fertility above intended levels. Insurance structures that fail to provide adequate coverage for infertility services or ensure generous coverage for contraception set the stage for a shortfall of births relative to intentions.

Structures can also influence the relationship between intentions and actual fertility by framing people’s responses to fertility outcomes. Gender structures in many areas of the world shape the meanings of sons and daughters and the expected roles of boys and girls and hence give rise to preferences for the sex composition of children. In the U.S., there is a well-documented stated preference for a mixed gender composition – to have one son and one daughter (Hank 2007). Common behavioral patterns instantiate this schema: couples expecting a second child often openly wish for a child of the opposite sex and couples with two children of the same sex are more likely to have a third child. In situations where the sex of children cannot be controlled, this preference leads to higher fertility. In societies where gender structures are less sharply differentiated or less salient or where such differentiation declines, this effect is diminished (Pollard and Morgan, 2002; Hank 2007).

Cohort fertility depends not only on the configuration of structural influences but also on the stability of the structural environment. Picture the cohort of US men and women born in 1960. In the year they were born, both the percent of men and women ever married and the TFR were at their highest points in the century (US Census Bureau 2007; NCHS 1999). By the time they were 20, families had changed dramatically: the TFR had been cut in half, declining from 3.7 to 1.8; the percent ever married had declined from 77 to 70, and the percent divorced had more than doubled. Other things had changed as well. The proportion of U.S. women ages 16 and older who were in the labor force had increased from 38% to 52% (Toosi 2002), manufacturing was on the decline and service industries were expanding, and educational attainment had increased dramatically. When asked by NLSY interviewers about their intended fertility in 1982, men and women in this cohort reported an average of about 2.5 births (Quesnel-Vallée and Morgan 2004). This cohort’s earliest family experiences occurred in the context of family structures that emphasized marriage and childbearing, but the cohort came to maturity as the children of the baby boom were flooding the labor market. The intentions expressed by this cohort represented a compromise between the family structures they had experienced and the structures that they now perceived as relevant to childbearing. This cohort never achieved its reported target: its completed fertility averaged around 2 births – a further compromise as work, family, and other structures continued to evolve, shaping not only what was possible but what was appropriate to the times (see Quesnel-Vallée and Morgan 2004; Morgan and Rackin 2010).

The Bongaarts framework focuses on the difference between reported intentions and fertility behavior. In doing so, it focuses on the causes of fertility behaviors and takes intentions as a given. However, as the above example suggests, concordance between intentions and actual fertility depends on the nature and stability of structural influences on both. If these influences are similar, the differences between measures of intentions and fertility should be relatively small. If intentions and fertility respond to different structural influences, or are differentially influenced by past and present structures as we argue above, then there is more room for divergence.

The dominant pattern in the developed world is for reported intentions to approximate replacement levels but for completed fertility to be modestly lower (Frejka and Calot 2004).17 The apparent structural story behind this gap is the tension between a relatively enduring, culturally shared, schema of the family as including at least two children, rooted in dominant family structures, and the tendency for anti-natalist pressures to exceed pro-natalist effects in contemporary economic, consumption, and health-related structures. A key question is: What makes the schema of the two-child family so resilient in the face of changing economic conditions? Is this resilience temporary, a sentimental holdover from earlier times, or is it driven by something fundamental in human experience? Evidence that intentions for one child are becoming more prevalent in parts of Europe (Goldstein et al 2003) suggests that the two-child norm could be a temporary phenomenon, subject to change in new generations. However, the U.S. experience clearly reflects some resistance to change.18

As the discussion in this section makes clear, both expressed intentions and actual fertility depend on two aspects of structures: the opportunities and constraints that have long been a focus of demographers and the schematic meanings they convey. It is not just the availability of jobs for women but the shared schemas about women’s roles; not just the access to or cost of abortion but the religious structures that color its acceptability. Health care structures that offer assisted reproductive technologies shape schemas about the boundaries of the fertile years, and, perhaps most importantly, family structures leave a profound imprint on people’s ideas about the size of a proper family. Expanding our view of structural influences to include those that shape the meaning and value of parenthood complements analyses of structural opportunities and constraints. Both contribute to understanding the relationship between reported intentions and fertility behaviors.

Bongaarts’s conceptualization of aggregate fertility behavior as a function of both intentions and fertility-constraining or -boosting factors provides a helpful frame for considering structural influences on fertility-intentions concordance. Concordance– addressed here at the cohort level –depends on the match between the structural effects on intentions and the structural conditions in which action related to fertility is (or is not) undertaken. Perfect concordance between intentions and fertility at the aggregate level would be achieved only if the net effects of the structural conditions influencing aggregate reported intentions were equal to the net effects of the structural conditions affecting fertility. Even in a perfectly stable society, this is unlikely. The structures that give rise to intentions are not necessarily the same structures that affect fertility, and even when they overlap, they may have differential effects on intentions and fertility. However, structural conditions in a society may evolve in ways that reduce the discordance between these sets of structures, just as the development of child care services has reduced the discordance between valued images of two-child families and the demands of female employment (Rindfuss et al., 2010).

Conclusions

Our paper began with contrasting pairs of statements on the predictive validity of reproductive intentions. We reconcile these statements by presenting a social-cognitive model of intentions and exploring its implications for what fertility intentions reported in surveys may represent for individuals at different stages of their reproductive life. The model links a pair of dualities at cognitive (individual) and social (macro) levels. At the individual level, automatic and deliberative processes in the brain interact to produce schemas, intentions and action, and at the aggregate level, material and schematic elements of structure interact to create the social environments that shape both the schemas about families and pregnancy that people learn and the situations in which these schemas are brought to bear on intention formation and action. The model identifies what cognitive and social processes give rise to intentions, and how these processes, as well as intentions themselves, exert an influence on fertility.

Our explanation of why fertility fails to match reported intentions at the individual level confirms common understandings but tells a richer, more elaborated, story. There are many unintended pregnancies because there are many situations within which the dominant schemas and materials are “not about” fertility. Pregnancy is the unanticipated consequence of actions aimed at other goals. Thus unintended pregnancies occur because goals are many and they are frequently not tightly integrated in our cognitive processes or in the material world.

Our explanation for the predictive validity of fertility intentions relies, in part, on individual-level psychology but also on relatively neglected structural explanations that promote stability in intentions over time. Many of the schemas that inform women’s reports of intentions are enduring – the image of a family, the affective value of family life – and are likely to have enduring effects on later fertility even when women are surveyed before forming intentions. These schemas are embedded in macro-level structures that are highly visible and relatively stable, also contributing to their durability at the individual level. When an intention is formed, its power to predict derives in part from the situation that gives rise to it – a decision environment that juxtaposes the opportunities and constraints afforded by different macro-level structures and focuses decision-making on realistic options.

In moving to understand the predictive power of intentions at the aggregate level, our framework focuses attention not only on how social structures frustrate or facilitate intentions but also how the structural environment contributes to the formation of reported intentions in the first place. Intentions and fertility may respond differentially to the opportunities and constraints that structures define and the meanings that they instantiate. Because fertility intentions may be rooted in deeply valued long-standing schemas about the family, whereas their implementation necessarily depends on contemporary structural conditions, there is much room for aggregate-level intentions and fertility to diverge over a cohort’s reproductive years. The size of these differences will depend on the organization and mix of structures relevant to fertility: where structures exist to reduce conflict between family schemas and structural constraints intentions should have greater predictive power.

Very generally, what is the “weak link” in intention/fertility research? Do we need more observations or a better way of thinking about what we have already observed? We stress the latter. Our data on intentions are useful, but we need to better understand and use them. The aim of this paper is to augment existing ways of thinking about intentions and the data demographers gather about them. We argue that intentions data are useful not only when they are valid measures of the underlying psychological construct, but also, to a lesser extent, when they are simply serving as indicators of the schemas and structures that shape people’s life trajectories.

Much can be done with our traditional survey measures. Reported intentions remain one of the strongest predictors of childbearing at the individual level and an important indicator at the aggregate level. But they are also misleading, in that they mask the more complex set of mental and social phenomena that drive behavior. By describing how these phenomena relate to intentions, our model can lead to hypotheses that are testable using the data we have now. For example, demographers can theorize about the circumstances under which fertility intentions may be formed and how these circumstances affect their chances of being realized, leading to differential specifications of models of the predictive value of intentions across life course stages.

Demographers can also combine existing survey measures with measures of the structural environment to test hypotheses about how structures shape both intentions and their realization across the life course. For example, by expanding the search for independent insights into structural arrangements, we can explore how structures set the scene for unintended fertility. Is it actually true that schemas that underlie fertility intentions draw on structures related to parenthood and family, whereas those that inform intentions about sex, contraception, and abortion may be more closely associated with structures related to relationships, pregnancy, morality, and risk? Our conceptualization of structure suggests that efforts should be made to capture not only the material structures that shape fertility (for example, the availability of day care services – Rindfuss et al. 2010 – or the prevalence of single-parent households – Harding 2010) but also the shared schemas that set the stage for parenthood (e.g., through analysis of parenting manuals –Hays 1998 – or ethnographic fieldwork – Edin and Kefalas 2005). Moving beyond our existing data will require theory development at the intersection of cognitive science, social science, and social demography. This paper is a contribution toward the needed theory development.

Acknowledgments

The authors are grateful for comments provided by Jennifer Johnson-Hanks, Rennie Miller, Ronald Rindfuss, Jennifer Buher Kane and two anonymous reviewers. We are grateful to the Carolina Population Center (R24 HD050924) and the Social Science Research Institute at Duke University for general support

Footnotes

For instance, the Fishbein and Ajzen (2010) model served as the conceptual cornerstone of a multicountry study of low European fertility and a conference and subsequent volume on fertility intentions. See Morgan, Sobotka and Testa 2011.

Fishbein and Ajzen (2010) review the development and application of their model in a range of substantive areas.

Fishbein and Ajzen (2010:51) allow that after intentions have been repeatedly invoked to produce behavior, they can be activated outside of consciousness; hence some habitual actions are not immediately preceded by conscious intention formation. Our critique focuses on the theory’s claim that conscious intentions must be formed at some point prior to the performance of a behavior.

Also referred to commonly as System 1 (automatic) and System 2 (controlled); Lieberman’s C (explicit learning and inhibitory, executive control) and X (associative learning, conditioning and automatic or implicit social cognition) systems (Lieberman 2007; Kahneman 2011).

“Store” is something of a misnomer: what is actually stored is the means to recreate the knowledge or image on an as-needed basis (Clark, 1997)

The term schema has been used both in the semantic sense adopted here and as signifying a disposition or process (e.g., a bonding schema; Miller and Rodgers 2001).

The concept of schema provides a flexible way of conceptualizing terms used in TRA and other psychological approaches to intentions research. Beliefs are complex schemas that link the meanings of objects, qualities, and actions, e.g. the belief that condoms frequently break. Attitudes are schemas associated with positive or negative value, e.g. a positive attitude towards babies or using a condom.

We define “situation” as a temporary arrangements of circumstances experienced by an individual. In other work we have used the term “conjuncture” to refer to short-term specific configurations of structures in which action can occur (Johnson-Hanks et al, 2011: 15). To make our language more accessible to demographers, we use the term situation to refer to the confluence of both material and schematic structures in a particular set of circumstances.

These schemas correspond to beliefs and attitudes in the terms of the classic psychological model. Beliefs and attitudes emerge from mental representations of parenthood, established over time and experience, which carry not only semantic but affective meanings.

LeDoux (2002) provides a discussion of the neural processes involved in motivation.

Miller (2011) has found evidence that fertility desires can bypass intentionality and act directly on behavior to influence fertility outcomes.

Warren Miller’s work (1992, 2011: Miller & Pasta 2002) provides a similar account, albeit framed in more traditional psychological terms. Miller emphasizes the distinction between desires and intentions, noting that desires are more closely tied than intentions to genetic foundations for fertility motivation (and, we would add, to schemas derived from social experience), and that fertility motivation is a product of both personality traits and developmental experiences.

The reader will notice that we are interchanging expectations with intentions in this summary. Survey reports of the two constructs tend to be similar. Our cognitive model provides a rationale for expecting this: for those who have not yet formed intentions, the reports likely draw from the same schemas; for those who have, the intention formation process and the implied commitment to act should produce a close correspondence between expectations and intentions. “Expectations” may actually provide a better term for survey reports of intentions for those who have not yet formed intentions.

Westoff and Ryder (1977: 449) conclude that “reproductive intentions are tailored to conditions at the time of interview and, thus, share the same possibilities of misinterpretation as other period indices.” We agree that such tailoring occurs, but emphasize in addition the powerful effect of past structures in shaping the schemas that underpin intentions.

The Bongaarts (2001) model is focused on period data (the total fertility rate, TFR) because it is by far the most commonly used and most widely available measure of fertility. The logic of the Bongaarts model follows a woman’s or a cohort’s experience. Thus, Bongaarts proposes a “synthetic cohort” approach. The left-hand side of the equation is the TFR, often described as a synthetic cohort – the fertility of women if they experienced the age-specific rates that exist in a particular year (or period). The right-hand side variables include a period measure of intentions – what women in a particular year say is their preferred or ideal size family. The macro constraints (S and P) are the ones that exist in a particular period – and would thus operate on the synthetic cohort. One parameter, and an important one, is removed as we move from a period to cohort representation: this is temporal distortion (see Bongaarts and Feeney 1998).

Period rates are affected directly and immediately by such postponement (see Bongaarts and Fenney 1998).

Period fertility is frequently well below reported intentions. A substantial part of this difference can be explained by fertility postponement (Bongaarts and Feeney 1998).

For example, between 1982 and 2002 the fertility expectations expressed by women 20–24 years of age varied between 2.32 and 2.46 – a range of only 1.4 births (Abma et al 1997; Chandra et al, 2005; Peterson 1995).

A previous version of this paper was given at the Population Association of America Annual Meetings, May 5, 2012.

Contributor Information

Christine A. Bachrach, Email: chrisbachrach@gmail.com.

S. Philip Morgan, Email: pmorgan@unc.edu.

References

- Abma Joyce, Chandra Anjani, Mosher William D, Peterson Linda, Piccinino Linda. Fertility, family planning, and women’s health: New data from the 1995 National Survey of Family Growth. National Center for Health Statistics. Vital Health Stat. 23(19) [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bachrach Christine A, Philip Morgan S. Further Reflections on the Theory of Planned Behavior and Fertility Research. Vienna Yearbook of Population Research. 2011;9:71–74. [Google Scholar]

- Bandura Albert. Social Learning Theory. Morristown, NJ: General Learning Press; 1977. [Google Scholar]

- Barber Jennifer S. Ideational influences on the transition to parenthood: Attitudes toward childbearing and competing alternatives. Social Psychology Quarterly. 2001;64(2):101–127. [Google Scholar]

- Bargh John A, Morsella Ezquiel. The unconscious mind. Perspectives on Psychological Science. 2008;3:73–79. doi: 10.1111/j.1745-6916.2008.00064.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bongaarts John. Fertility and Reproductive Preferences in Post-Transitional Societies. Population and Development Review. 2001;27:260–281. (Supplement: Global Fertility Transition) [Google Scholar]

- Bongaarts John, Potter Robert G. Fertility, Biology and Behavior. New York: Academic Press; 1983. [Google Scholar]

- Bongaarts John, Feeney Griffith. On the quantum and tempo of fertility. Population and Development Review. 1998;24(2):271–291. [Google Scholar]

- Anjani Chandra, Martinez Gladys M, Mosher William D, Abma Joyce C, Jones Jo. Fertility, family planning, and reproductive health of U.S. women: Data from the 2002 National Survey of Family Growth. National Center for Health Statistics. Vital Health Stat. 2005;23(25) [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Clark Andy. Being There: Putting Brain, Body, and World Together Again. Cambridge, MA: MIT Press; 1997. [Google Scholar]

- Damasio Antonio. Self Comes to Mind: Constructing the Conscious Brain. New York: Pantheon; 2010. [Google Scholar]

- Davis Kingsley, Blake Judith. Social Structure and Fertility: An Analytical Framework. Economic Development and Cultural Change. 1956;4:211–235. [Google Scholar]

- DiMaggio Paul. Culture and Cognition. Annual Review of Sociology. 1997;23:263–287. [Google Scholar]

- Donald Merlin. A Mind So Rare: The Evolution of Human Consciousness. New York: W. W. Norton & Company; 2002. [Google Scholar]

- Edin Kathryn, Kefalas Maria. Promises I Can Keep: Why Poor Women Put Motherhood Before Marriage. Los Angeles: University of California Press; 2005. [Google Scholar]

- Ehrlich Paul R. The Population Bomb. New York: Sierra Club/Ballantine; 1968. [Google Scholar]

- Evans Jonathan St BT. Dual-Processing Accounts of Reasoning, Judgment, and Social Cognition. Annual Review of Psychology. 2008;59:255–78. doi: 10.1146/annurev.psych.59.103006.093629. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Finer Lawrence B, Henshaw Stanley K. Disparities in rates of unintended pregnancy in the United States, 1994 and 2001. Perspectives in Sexual and Reproductive Health. 2006;38:90–96. doi: 10.1363/psrh.38.090.06. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fishbein Martin, Azjen Icek. Predicting and Changing Behavior. New York: Taylor & Francis; 2010. [Google Scholar]

- Foote Nelson N. Identification as the Basis for a Theory of Motivation. Am Sociol Rev. 1951;16:14–21. [Google Scholar]

- Frejka Tomas, Calot Geard. Cohort Reproductive Patterns in Low-Fertility Countries. Population and Development Review. 2004;27:103–132. [Google Scholar]

- Gazzaniga Michael S. Who’s in Charge: Free Will and the Science of the Brain. New York: HarperCollins Publishers; 2011. [Google Scholar]

- Giddens Anthony. Central Problems in Social Theory: Action, Structure, and Contradiction in Social Analysis. Berkeley: University of California Press; 1979. [Google Scholar]

- Goldstein Joshua, Lutz Wolfgang, Testa Maria Rita. The emergence of Sub-Replacement Family Size Ideals in Europe. Population Research and policy Review. 2003;22:479–496. [Google Scholar]

- Hank Karsten. Parental gender preferences and reproductive behaviour: A review of the recent literature. J Biosoc Sci. 2007;39:759–767. doi: 10.1017/S0021932006001787. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Harding David J. Living the Drama: Community, Conflict, and Culture Among Inner-City Boys. Chicago: University of Chicago Press; 2010. [Google Scholar]

- Harter Susan. The Construction of Self: A Developmental Perspective. New York: Guilford Press; 1999. [Google Scholar]

- Hayford Sarah R. The evolution of fertility expectations over the life course. Demography. 2009;46(4):765–784. doi: 10.1353/dem.0.0073. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hayford Sarah R, Philip Morgan S. Religiosity and fertility in the United States: The role of fertility intentions. Social Forces. 2008;86(3):1163–1188. doi: 10.1353/sof.0.0000. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hays Sharon. The Cultural Contradictions of Motherhood. New Haven: Yale University Press; 1998. [Google Scholar]

- Hitlin Steven. Values as the Core of Personal Identity: Drawing Links between Two Theories of Self. Social Psychology Quarterly. 2003;66(2):118–137. Special Issue: Social Identity: Sociological and Social Psychological Perspectives. [Google Scholar]

- Maria Iacovou, Tavares Lara Patricio. Yearning, learning, and conceding: Reasons men and women change their childbearing intentions. Population and Development Review. 2011;37(1):89–123. doi: 10.1111/j.1728-4457.2011.00391.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ignatow Gabriel. Theories of Embodied Knowledge: New Directions for Cultural and Cognitive Sociology? Journal for the Theory of Social Behaviour. 2007;37(2):115–135. [Google Scholar]

- Johnson-Hanks Jennifer. Uncertain Honor: Modern Motherhood in an African Crisis. Chicago: University of Chicago Press; 2005a. [Google Scholar]

- Johnson-Hanks Jennifer. When the future decides: Uncertainty and intentional action in contemporary Cameroon. Current Anthropology. 2005b;46(3):363–85. [Google Scholar]

- Johnson-Hanks Jennifer, Bachrach Christine A, Philip Morgan S, Kohler Hans-Peter. Understanding Family Change and Variation: Structure, Situation, and Action. New York: Springer; 2011. [Google Scholar]

- Jones Elise F, Forrest Jacqueline Darroch, Goldman Noreen, Henshaw Stanley K, Lincoln Richard, Rosoff Jeannie I, Westoff Charles F, Wulf Deirdre. Teenage pregnancy in developed countries: Determinants and policy implications. Family Planning Perspectives. 1985;17(2):53–63. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kahneman Daniel. Thinking, Fast and Slow. New York: Farrar, Straus and Giroux; 2011. [Google Scholar]

- Klerman Lorraine V. The intendedness of pregnancy: a concept in transition. Maternal and Child Health Journal. 2000;4:155–162. doi: 10.1023/a:1009534612388. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Joseph LeDoux. Synaptic Self: How Our Brains Become Who We Are. New York: Penguin; 2002. [Google Scholar]

- Libet Benjamin, Gleason Curtis A, Wright Elwood WEW, Pearl Dennis K. Time of conscious intention to act in relation to onset of cerebral activity (readiness-potential): The unconscious initiation of a freely voluntary act. Brain. 1983;106(3):623–642. doi: 10.1093/brain/106.3.623. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lieberman Matthew D. Social Cognitive Neuroscience: A Review of Core Processes. Annual Review of Psychology. 2007;58:259–89. doi: 10.1146/annurev.psych.58.110405.085654. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Luker Kristin C. A reminder that human behavior frequently refuses to conform to models created by researchers. Family Planning Perspectives. 1999;31(5):248–249. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Malle Bertram F, Moses Louis J, Baldwin Dare A. Intentions and Intentionality: Foundations of Social Cognition. Cambridge: MIT Press; 2003. [Google Scholar]

- McClelland James L, McNaughton Bruce L, O’Reilly Randall C. Why there are complementary learning systems in the hippocampus and neocortex: Insights from the successes and failures of connectionist models of learning and memory. Psychological Review. 1995;102(3):419–457. doi: 10.1037/0033-295X.102.3.419. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McNicoll Geoffrey. Institutional determinants of fertility change. Population and Development Review. 1980;6 (3):441–462. [Google Scholar]

- Mandler George. Mind and Body: The Psychology of Emotion and Stress. New York: Norton; 1984. [Google Scholar]

- Martin Joyce A, Hamilton Brady E, Ventura Stephanie J, Osterman Michelle JK, Kirmeyer Sharon, Mathews TJ, Wilson Elizabeth C. Births: Final Data for 2009. National Center for Health Statistics. National Vital Statistics Reports. 2011;60(1) [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Martinez Gladys M, Chandra Anjani, Abma Joyce C, Jones Jo, Mosher William D. Fertility, contraception, and fatherhood: Data on men and women from Cycle 6 (2002) of the National Survey of Family Growth. National Center for Health Statistics. Vital Health Stat. 2006;23(26) [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McPherson Miller. A Blau Space Primer: Prolegomenon to An Ecology of Affiliation. Industrial and Corporate Change. 2004;13:263–280. [Google Scholar]

- Miller Warren B. Proception: An Important Fertility Behavior. Demography. 1986;23:579–594. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Miller Warren B. Personality-traits and developmental experiences as antecedents of childbearing motivation. Demography. 1992;29(2):265–285. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Miller Warren B. Differences between Fertility Desires and Intentions: Implications for Theory, Research, and Policy. Vienna Yearbook of Population Research. 2011;9 [Google Scholar]

- Miller Warren B, Rodgers Joseph Lee. The Ontology of Human Bonding Systems: Evolutionary Origins, Neural Bases, and Psychological Manifestations. Boston: Kluwer Academic Publishers; 2001. [Google Scholar]

- Miller Warren B, Pasta David J. The Motivational Substrate of Unintended and Unwanted Pregnancy. Journal of Applied Biobehavioral Research. 2002;7(1):1–29. [Google Scholar]

- Morgan S Philip. Should Fertility Intentions Inform Fertility Forecasts?. Proceedings of U.S. Census Bureau Conference: The Direction of Fertility in the United States; Washington D.C: U.S. Census Bureau; 2001. [Google Scholar]

- Morgan S Philip. Is low fertility a 21st century demographic crisis? Demography. 2003;40:589–603. doi: 10.1353/dem.2003.0037. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Morgan S Philip, Bachrach Christine A. Is the Theory of Planned Behavior an Appropriate Model for Human Fertility? Vienna Yearbook of Population Research. 2011;9:11–18. [Google Scholar]

- Morgan S Philip, Parnell Allan M. Effects on pregnancy outcomes of changes in the North Carolina State Abortion Fund. Population Research and Policy Review. 2002;21 (4):319–338. [Google Scholar]

- Morgan S Philip, Rackin Heather. The Correspondence of Fertility Intentions and Behavior in the U.S. Population and Development Review. 2010;36(1):91–118. doi: 10.1111/j.1728-4457.2010.00319.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Morgan S Philip, Taylor Miles. Low Fertility in the 21st Century. Annual Review of Sociology. 2006;32:375–400. doi: 10.1146/annurev.soc.31.041304.122220. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Morgan S Philip, Sobotka Tomas, Testa Maria Rita., editors. Vienna Yearbook of Population Research, Volume 2011, Special issue on “Reproductive decision-making”. Vienna Institute of Demography, Austrian Academy of Sciences; 2011. [Google Scholar]

- Ní Bhrolcháin Máire, Beaujouan Éva. Uncertainty in fertility intentions in Britain, 1979–2007. Vienna Yearbook of Population Research. 2011:99–129. [Google Scholar]

- Ní Bhrolcháin Máire, Beaujouan Éva. How real are reproductive goals? Uncertainty and the construction of fertility preferences. Presented at Annual Meeting of Population Association of America; May 5; San Francisco. 2012. [Google Scholar]

- Parsons Talcott. The Structure of Social Action. Glencoe: The Free Press; 1949. [Google Scholar]

- Peterson LS. Birth expectations of women in the United States: 1973–88. National Center for Health Statistics. Vital and Health Statistics. 1995;23(17) [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pollard Michael S, Philip Morgan S. Emerging parental gender indifference? Sex composition of children and the third birth. American Sociological Review. 2002;67:600–613. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]