Abstract

In 2012, an estimated 35.3 million people lived with HIV, while approximately two million new HIV infections were reported. Community-based interventions (CBIs) for the prevention and control of HIV allow increased access and ease availability of medical care to population at risk, or already infected with, HIV. This paper evaluates the impact of CBIs on HIV knowledge, attitudes, and transmission. We included 39 studies on educational activities, counseling sessions, home visits, mentoring, women’s groups, peer leadership, and street outreach activities in community settings that aimed to increase awareness on HIV/AIDS risk factors and ensure treatment adherence. Our review findings suggest that CBIs to increase HIV awareness and risk reduction are effective in improving knowledge, attitudes, and practice outcomes as evidenced by the increased knowledge scores for HIV/AIDS (SMD: 0.66, 95% CI: 0.25, 1.07), protected sexual encounters (RR: 1.19, 95% CI: 1.13, 1.25), condom use (SMD: 0.96, 95% CI: 0.03, 1.58), and decreased frequency of sexual intercourse (RR: 0.76, 95% CI: 0.61, 0.96). Analysis shows that CBIs did not have any significant impact on scores for self-efficacy and communication. We found very limited evidence on community-based management for HIV infected population and prevention of mother- to-child transmission (MTCT) for HIV-infected pregnant women. Qualitative synthesis suggests that establishment of community support at the onset of HIV prevention programs leads to community acceptance and engagement. School-based delivery of HIV prevention education and contraceptive distribution have also been advocated as potential strategies to target high-risk youth group. Future studies should focus on evaluating the effectiveness of community delivery platforms for prevention of MTCT, and various emerging models of care to improve morbidity and mortality outcomes.

Keywords: Community-based interventions, Antiretroviral therapy, HIV prevention, HIV/AIDS

Multilingual abstracts

Please see Additional file 1 for translations of the abstract into the six official working languages of the United Nations.

Introduction

In 2012, an estimated 35.3 million people lived with HIV, while approximately two million new HIV infections were reported globally; a 33% decline in the number of new infections as compared to 2001 [1]. Concurrently, the number of AIDS deaths also declined from 2.3 million in 2005 to 1.6 million in 2012 [1]. As many as eight million people in low- middle- income countries (LMICs) are currently receiving lifesaving treatment [2]. In Sub-Saharan Africa, interventions to prevent HIV led to a decline in the number of newly infected children by 24% between 2009 and 2011 [3], owing to the rapid increase in access to preventive and therapeutic services for women with HIV. Notwithstanding the progress made on many fronts since the emergence of AIDS in 1981, a lot more still needs to be done. The number of new HIV infections among children was 210,000; five out of 10 women or their infants did not receive antiretroviral (ARV) medicines during breastfeeding to prevent mother-to-child transmission (MTCT); and four out of 10 pregnant women living with HIV did not receive ARV medicines to prevent MTCT, in 2012 [4]. The intricate link between tuberculosis (TB) and HIV also poses a major threat to the efforts to control both infections as people living with HIV have a 12–20 times higher risk of developing TB. The details on HIV epidemiology, burden, and transmission has been documented in our previous publication [5].

Effective HIV prevention measures should ideally emphasize human dignity, responsibility, voluntary participation, and empowerment through access to information, services and support systems [6]. A thorough understanding of common values and belief systems also helps to identify positive values and practices that can facilitate and more effectively promote HIV interventions. Hence community-based approaches are increasingly being advocated for HIV prevention. Community-based interventions (CBIs) are built on shared values and norms, and belief systems and social practices, and permit culturally sensitive discussions of HIV, and sexual and reproductive health. They allow increased access and ease availability of medical care to population potentially at risk of, or already infected with HIV by reaching individuals in homes, schools, or community centres. CBIs involve education and counseling to promote HIV awareness and risk-reducing behaviors, promotion of HIV testing and counseling, administering of appropriate treatment to HIV-infected mothers to prevent MTCT, micronutrient supplementation for pregnant and lactating women and interventions to increase adherence to treatment via home visits. Nonetheless, the nature and scale of CBIs vary according to the type of the HIV epidemic scenario. In hyperendemic situations and generalized epidemics, extraordinary efforts are required to mobilize the whole community. In low-prevalence countries and concentrated epidemics, CBIs should focus on reaching those groups that are most at risk [6].

This paper aims to systematically analyze the effectiveness of CBIs for the prevention and management of HIV, including education and counseling, adherence to treatment and MTCT.

Methods

We systematically reviewed literature published before July 2013 to identify randomized controlled trials (RCTs), quasi-experimental, and before-and-after studies on CBIs for the prevention and management of HIV. Studies were included if intervention was delivered within community settings and reported outcomes were relevant to the review. We excluded studies if any component of the intervention was delivered at a health facility; if the interventions targeted special populations including sex workers, men who have sex with men, injection drug users, prisoners, bar workers, patients with mental illness and armed forces; or if the objective was to evaluate process outcomes. Search was conducted in PubMed, Cochrane libraries, Embase, and the World Health Organization (WHO) Regional Databases to identify all published and unpublished studies. Additional studies were identified by manually searching references from the included studies. Studies that met the inclusion criteria were selected and double data abstracted on a standardized abstraction sheet. Quality assessment of the included RCTs was done using the Cochrane risk of bias assessment tool [7]. We conducted meta-analysis for individual studies using the software Review Manager 5.1. Pooled statistics were reported as relative risk (RR) for categorical variables and standard mean difference (SMD) for continuous variables between the experimental and control groups with 95% confidence intervals (CIs). The outcomes of interest included knowledge, attitudes, and behavior outcomes; birth outcomes; HIV transmission; and morbidity and mortality. These are outlined in Table 1. We also attempted to qualitatively synthesize the findings reported in the included studies for other pragmatic parameters identified in our conceptual framework including intervention coverage, challenges/barriers, enabling factors, aspects related to the integrated delivery, monitoring and evaluation and equity. The detailed methodology is described in Paper 2 of this series [8].

Table 1.

Outcomes analyzed

| Outcomes | Outcomes analyzed |

|---|---|

|

Knowledge, attitudes, and behaviors |

Knowledge about HIV/AIDS and risk reduction |

| Self-efficacy | |

| Communication | |

| Engaging in sexual intercourse | |

| Protected sex | |

| Treatment adherence | |

|

Birth outcomes |

Low birth weight |

| Stillbirth | |

|

HIV transmission |

HIV infection at birth |

| HIV infection among infants with/without breastfeeding | |

|

Morbidity and mortality |

Detectable viral load |

| All-cause mortality | |

| Cause-specific mortality |

Review

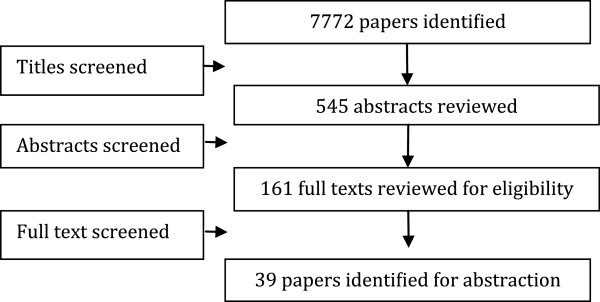

We identified 7,772 titles from the search conducted in all databases. After screening titles and abstracts, 161 full texts were reviewed; of which 39 studies (Figure 1) [9-35] were selected for inclusion. These included 18 RCTs, 14 quasi-experimental studies, and seven before-and-after studies. Nine studies could not be included in the meta-analysis as they did not report poolable data. For the 18 RCTs, randomization was adequate in all the studies except for one, allocation concealment and participant blinding could not be done in majority of the studies due to the nature of interventions, adequate sequence generation was not done or unclear in most of the studies, and selective reporting was not apparent in any of the studies (see Table 2).

Figure 1.

Search flow diagram.

Table 2.

Quality assessment of the included RCTs

| Article | Randomization | Sequence generation | Allocation concealment | Blinding of participants | Blinding of assessors | Selective reporting |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Berrien 2004 |

Done |

Done |

Done |

No |

No |

No |

| Carlson 2012 |

Done |

Done |

Not clear |

No |

No |

No |

| Chhabra 2010 |

Done |

Coin toss |

No |

No |

No |

No |

| Chen 2011 |

Done |

Not clear |

No |

No |

Not clear |

No |

| Clark 2005 |

Not clear |

No |

No |

No |

No |

No |

| Fawole 1999 |

Done |

Not clear |

Not clear |

No |

No |

No |

| Fitzgerald 1999 |

Done |

Not clear |

Not clear |

No |

No |

No |

| Huba 1999 |

Done |

Not clear |

No |

No |

Not clear |

No |

| Kiene 2006 |

Done |

Done |

No |

No |

Not clear |

No |

| Klepp 1997 |

Done |

Not clear |

No |

No |

Not clear |

No |

| Jemmott 2010 |

Done |

Done |

No |

No |

Yes |

No |

| Rotheram-Borus 1998 |

Done |

Not Clear |

No |

No |

Yes |

No |

| Shapiro 2010 |

Done |

Done |

Not clear |

Not clear |

Not clear |

No |

| Selke 2010 |

Done |

Not clear |

No |

No |

Not clear |

No |

| Walker 2004 |

Done |

Done |

Not clear |

No |

Not clear |

No |

| Williams 2006 | Done | Done | No | No | Done | No |

Included studies mainly focused on community-based HIV prevention through educational activities, counseling sessions, home visits, mentoring, women’s groups, peer-leadership, custom computerized HIV/AIDS risk reduction, and street outreach activities and address perceived barriers to counseling and voluntary testing. Among studies conducted on known HIV cases, three studies provided home healthcare to HIV-infected adults to improve general health and treatment adherence, one study evaluated the impact of community delivered ARV regimens during pregnancy and breast feeding, and one study utilized computer-based technologies including Personal Digital Assistant to support home assessments for HIV-infected adults. Most of the studies targeted adolescents and youth, while some targeted HIV-infected population in general, urban working women, and high-risk heterosexual men. All of the studies were non-integrated including six studies that were school-based. The characteristics of the included studies are summarized in Table 3.

Table 3.

Characteristics of the included studies

| Study | Study design | Country | Intervention | Target Population | Integrated/non-Integrated |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Agarwal 2004 |

Pre-post study |

India |

Health education about the prevention of reproductive tract infection and HIV/AIDS imparted through one-to-one interactions with men and women during home visits, at village-based clinics and health camps, and through health-education talks with men and women |

Men and women of reproductive age |

Non-integrated |

| Baptiste 2006 |

Quasi- experimental |

South Africa, Trinidad, and Tobago |

Community participatory, family-based prevention (CHAMP) |

Youth |

Non-integrated |

| Berrien 2004 |

RCT |

USA |

Eight structured home visits for education and counseling to improve adherence over a three-month period by a registered nurse |

HIV-positive children and youth (aged 7 years and above) |

Non-integrated |

| Blake 2003 |

Pre-post |

USA |

Condom availability in high schools, and community discussion and involvement for HIV prevention |

Adolescents |

Non-integrated |

| Carlson 2012 |

cRCT |

Tanzania |

28-week course in health curriculum, two-to-three hour weekly sessions on HIV/AIDS competence and other subjects (citizenship, community health, social ecology) |

Adolescents aged 9–14 years |

School-based non-integrated |

| Chen 2011 |

RCT |

Bahamas |

Teaching sessions involving parents |

Youth |

School-based non-integrated |

| Chhabra 2010 |

RCT |

India |

HIV/AIDS and alcohol abuse educational program designed keeping in mind cultural, linguistic, and community-specific characteristics. A single one-hour session per week for 10 consecutive weeks. |

Rural and tribal youth aged 13–16 years, in schools |

School-based non-integrated |

| Clark 2005 |

RCT |

USA |

Ten sessions on adult identity mentoring, conducted once or twice a week for six weeks |

African-American seventh-grader students |

School based non-integrated |

| Fawole 1999 |

RCT |

Nigeria |

Health education initiatives to increase HIV knowledge and sexual practices |

School children |

School-based non-integrated |

| Fitzgerald 1999 |

RCT |

Namibia |

14-sessions of face-to face intervention emphasizing abstinence and safer sex for HIV prevention |

Youth |

Non-integrated |

| Harper 2009 |

Quasi- experimental |

USA |

Nine sessions of community-based, culturally- and ecologically-tailored HIV prevention intervention (SHERO) |

Mexican-American female adolescents aged 12–21 years |

Non-integrated |

| Heitgerd 2011 |

Pre-post study |

USA |

Community-based small group discussions on healthy relations |

People living with HIV |

Non-integrated |

| Huba 1999 |

RCT |

USA |

Home healthcare via home visits by multi-disciplinary teams |

People living with HIV |

Non-integrated |

| Jemmott 2010 |

cRCT |

South Africa |

Two six-session interventions based on behavior-change theories on HIV/STD risk-reduction targeted at sexual risk behaviors |

Sixth-grade students |

School-based non-integrate |

| Jemmott 1998 |

RCT |

USA |

Abstinence and safe sex HIV risk reduction intervention |

African-American adolescents |

Non-integrated |

| Kiene 2006 |

RCT |

US |

A custom computerized HIV/AIDS risk reduction intervention to increase HIV/AIDS preventive behaviors |

General population |

Non-integrated |

| Kinsler 2004 |

Quasi- experimental |

Belize |

Cognitive-behavioral peer-facilitated school-based HIV/AIDS education program |

School children |

Non-integrated school- based |

| Kinsman 2001 |

Quasi- experimental |

Uganda |

Non-integrated school-based program |

School children |

Non-integrated school- based |

| Klepp 1997 |

RCT |

Tanzania |

Program to reduce children’s risk of HIV infection, and improve tolerance and care towards HIV patients |

Sixth-grade students |

Non-integrated school- based |

| Li 2012 |

Quasi- experimental |

China |

School-based curriculum for HIV prevention education |

School children |

Non-integrated school- based |

| Maticka-Tyndale 2007 |

Quasi- experimental |

Kenya |

Primary-school HIV education initiative on the knowledge, self-efficacy and sexual practices, and condom use |

School children |

Non-integrated school- based |

| Mcbride 2007 |

Quasi- experimental |

USA |

Family-based HIV preventive intervention (CHAMP) |

African-American youth |

Non-integrated |

| Merakou 2006 |

Quasi- experimental |

Greece |

Peer-education intervention |

Adolescents |

Non-integrated school- based |

| Middelkoop 2006 |

Quasi- experimental |

South Africa |

Young adults from the community received training in HIV/AIDS and drama, and developed sketches to address perceived barriers to voluntary counseling and testing |

Young adults and community members |

Non-integrated |

| Morisky 2004 |

Quasi- experimental |

Philippines |

Participatory action research to change high-risk sexual behaviors |

Heterosexual men |

Non-integrated |

| Munodawafa 1995 |

Quasi- experimental |

Zimbabwe |

Health instruction provided by student nurses on prevention of STDs, HIV/AIDS, and drugs |

School children |

Non-integrated school- based |

| Murdock 2003 |

Pre-post study |

South Africa |

Female-led HIV workshops |

Women |

Non-integrated |

| Nelson 2012 |

Pre-post study |

USA |

Native Voice Intervention: four-day workshop on substance abuse, HIV, and hepatitis prevention |

American Indian/Alaska native youth |

Non-integrated |

| Norr 2004 |

Quasi-experimental |

Botswana |

Peer-group HIV prevention intervention based on social–cognitive learning theory, gender inequality, and the primary health care model for community-based health promotion |

Urban employed women |

Non-integrated |

| Okonofua 2003 |

RCT |

Nigeria |

Community participation, peer education, public lectures, health clubs in the schools, and training of STD treatment providers |

Adolescents |

Non-integrated |

| Pearlman 2002 |

Quasi- experimental |

USA |

Community-based HIV/AIDS peer leadership prevention program |

Adolescents |

Non-integrated |

| Rotheram-Borus 1998 |

RCT |

USA |

Education sessions: a seven-session intervention of 1.5 hours each or a three-session intervention of 3.5 hours each |

Adolescent aged 13–24 years |

Non-integrated |

| Selke 2010 |

cRCT |

Kenya |

The intervention group received monthly Personal Digital Assistant for supported home assessments |

Adult with HIV on ART |

Non-integrated |

| Shapiro 2010 |

RCT |

Southern Botswana |

300 mg of Abacavir, 300 mg of Zidovudine, and 150 mg of Lamivudine twice daily (the NRTI group), or 400 mg of Lopinavir and 100 mg of Ritonavir co-formulated as Kaletra (Abbott) with 300 mg of Zidovudine and 150 mg of Lamivudine twice daily (the protease-inhibitor group) from 26 to 34 weeks’ gestation through planned weaning by six months post partum |

HIV-infected women between 26 and 34 weeks’ gestation |

Non-integrated |

| Villarruel 2006 |

Pre-post study |

Philadelphia, USA |

HIV and health-promotion control interventions consisting of six 50-minute modules delivered by adult facilitators to small, mixed-gender groups |

Adolescents |

Non-integrated |

| Visser 2005 |

Pre-post study |

South Africa |

Life skills training and HIV/AIDS education in schools as part of the school curriculum |

Adolescents |

School-based non-integrated |

| Walker 2004 |

RCT |

Mexico |

HIV prevention course that promoted condom use, the same course with emergency contraception as back-up, or the existing sex education course |

Adolescents |

School-based non-integrated |

| Williams 2006 |

RCT |

USA |

Community-based, home-visit intervention to improve medication adherence |

Adults with HIV on ART |

Non-integrated |

| Wendell 2003 | Quasi-experimental | USA | Street outreach intervention to improve risk behaviors | General population | Non-integrated |

Quantitative synthesis

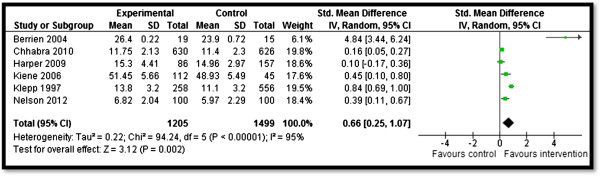

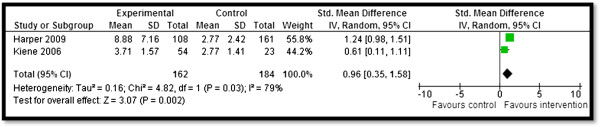

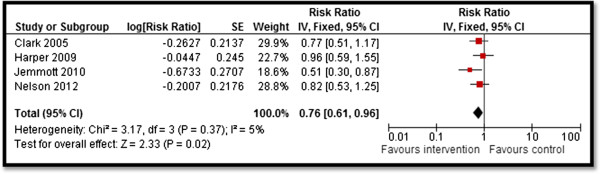

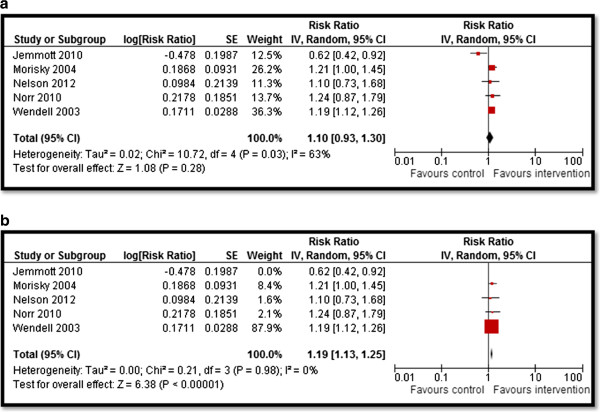

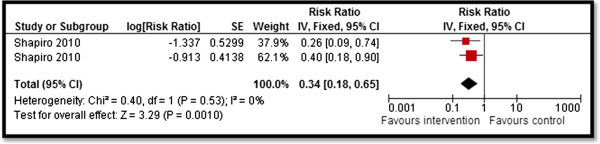

Table 4 summarizes the quantitative findings. CBIs to increase awareness about HIV/AIDS risk factors and promote preventive measures resulted in significant improvement in outcomes related to HIV/AIDS knowledge, attitudes, and behavior. Community delivered interventions such as HIV/AIDS education and counseling during home visits, educational programs built on community specific characteristics, and computer-based HIV risk reduction interventions significantly improved participants’ knowledge scores (SMD: 0.66; 95% CI: 0.25, 1.07) for HIV/AIDS (see Figure 2). Community-based culturally and ecologically tailored HIV prevention interventions and custom computerized HIV risk reduction interventions resulted in a significantly increased condom use (SMD: 0.96; 95% CI: 0.03, 1.58) among the target population (see Figure 3). Community education on abstinence and safe sex, and adult identity mentoring for preventing HIV risk behaviors led to a significant decrease in sexual activity (RR: 0.76; 95% CI: 0.61, 0.96) (see Figure 4). The frequency of protected sex increased by 19% (RR: 1.19; 95% CI: 1.13, 1.25), with street outreach activities and peer-group education on abstinence and HIV risk reduction. However, this finding was reported in sensitivity analysis conducted after removing Jemmott 2010 [28] due to high heterogeneity, and because this study proved to be an outlier on visual inspection (see Figure 5a and 5b). Our analysis did not find any impact of CBIs on scores for self-efficacy, risk taking, and communication.

Table 4.

Summary estimates for the overall and subgroup analysis for school-based, non-integrated, and integrated delivery strategies

|

Outcomes |

Estimates |

|---|---|

| Knowledge, attitudes, and practices | |

| HIV/AIDS related knowledge |

0.66 [0.25, 1.07] 6 datasets, 6 studies |

| Self-efficacy |

0.42 [-0.09, 0.93] 4 datasets, 4 studies |

| Communication |

-0.10 [-0.56, 0.35] 5 datasets, 5 studies |

| Risk taking |

-0.18 [-0.43, 0.07] 1 dataset, 1 study |

| Engaging in sexual intercourse |

0.76 [0.61, 0.96] 4 datasets, 4 studies |

| Protected sex |

1.10 [0.93, 1.30] 5 datasets, 5 studies |

| Protected sex (with sensitivity analysis) |

1.19 [1.13, 1.25] 4 datasets, 4 studies |

| Mean number of times condoms used |

0.96 [0.35, 1.58] 2 datasets, 2 studies |

| Treatment adherence score |

3.88 [2.69, 5.07] 1 dataset, 1 study |

|

Birth outcomes |

|

| Low birth weight |

0.92 [0.68, 1.24] 2 datasets, 1 study |

| Stillbirth |

0.34 [0.18, 0.65] 2 datasets, 1 study |

|

HIV transmission |

|

| HIV at birth |

1.32 [0.24, 7.31] 2 datasets, 1 study |

| HIV infection at six months among breastfed infants |

1.74 [0.33, 9.31] 2 datasets, 1 study |

|

Morbidity and Mortality |

|

| Detectable viral load |

1.16 [0.48, 2.80] 2 datasets, 2 studies |

| All-cause infant mortality (in six months) | 0.56 [0.27, 1.17] 2 datasets, 1 study |

*estimates in bold are statistically significant.

Figure 2.

Forest plot for the impact of CBIs on knowledge.

Figure 3.

Forest plot for the impact of CBIs on condom use.

Figure 4.

Forest plot for the impact of CBIs on sexual activity.

Figure 5.

Forest plot for the impact of CBIs on protected sex (a) with all studies, (b) after sensitivity analysis.

We found limited evidence on the effectiveness of CBIs for the management of HIV-infected population. Home visits for HIV patients to improve treatment adherence and general health outcomes led to a significant increase in treatment adherence score (MD: 3.88; 95% CI: 2.69–5.07), however, this finding is based on a single study. One study evaluated community-based delivery of highly- active antiretroviral therapy (HAART) during pregnancy and lactation to prevent MTCT [33]. It reported significant decrease in stillbirths by 66% (RR 0.34; 95% CI: 0.18, 0.65) (see Figure 6), while there were no significant impacts on low birth weight (LBW), and HIV transmission at birth or at six months among breastfeeding infants. We did not find any impact of CBIs on morbidity and mortality outcomes.

Figure 6.

Forest plot for the impact of CBIs on stillbirth.

Qualitative synthesis

Community support and mobilization have been reported as the key enabling factors for the success of CBIs for HIV prevention since they require a culturally sensitive approach [24,25]. Localized intervention strategies aimed at community mobilization were found to be effective and sustainable when delivered within the context of an existing or emergent public health system and linked to other programs in the community [25]. Most of the studies focusing on the prevention of HIV risk behaviors targeted adolescents and highlighted the significance of culturally grounded HIV prevention programs created in collaboration with community members to address adolescent sexual behaviors and prevent unhealthy sexual practices [13]. Culturally sensitive educational interventions have reported increased knowledge, efficacy, confidence and communication skills, and decreased risky behaviors [25]. The establishment of community support at the onset of such programs led to acceptance and engagement of the community in HIV prevention efforts even in remote and less industrialized areas [25,36]. Emphasizing citizenship skills, active participation, and decision making promoted adolescent participation in HIV prevention programs targeting young people [24]. Continuous involvement from the former participants and facilitators in education and community development are also key components to increase coverage and participation [24]. School-based delivery of HIV prevention education and contraceptive distribution have also been advocated as strategies to target the high-risk youth group. Studies support using teachers as life skills presenters because they have contact with the students on an ongoing basis, which contributes to the sustainability of the program [36]. However, teachers require a lot of support from the project teams to facilitate change.

Included studies suggest that home-based interventions can achieve better adherence to prescribed medication regimens among HIV-positive children, adults, and their families as it allows their patients and caretakers to better understand HIV infection and ARV medications [11,23]. Home-based delivery of ART and health education by nurses help to build trusting and accepting relationships between nurses and families, which can ensure successful adherence [11].

One of the major barriers in implementing programs for HIV prevention and screening is the traditional cultural beliefs and reluctance to talk about sexual issues. This poses a major roadblock in the development of HIV education programs [25]. These barriers could be addressed if the community was involved from the very inception of such programs and provided an opportunity to design initiatives that are sensitive to their culture and beliefs. Schools-based HIV prevention programs are also faced with issues such as maintaining specific standards of safety, discipline and educational attainment, and often lack resources for HIV prevention interventions. Low teacher involvement, lack of human resources, and low awareness and commitment to deal with the problem makes school-based delivery difficult [36]. When designing school-based programs, regional differences need to be taken into account as some schools might be more comfortable with a single sex delivery for HIV prevention interventions [25]. Furthermore, despite the intensive training, teachers rarely change their preconceptions about adolescent sexuality [37]. Compounding these problems is the issue that many adolescents lack strong role models and mentors to guide them through the exploration that naturally occurs as a part of adolescent self-identity development, thus potentially leading to unhealthy and risky sexual practices [26].

Discussion

Our review findings suggest that CBIs to increase HIV awareness and risk reduction interventions are effective in improving knowledge, attitudes, and practice outcomes as evidenced by increased knowledge scores for HIV/AIDS, protected sexual encounters, condom use, and decreased frequency of sexual intercourse. CBIs did not show any impact on scores for self-efficacy and communication. We found very limited evidence on community-based management programs for HIV-infected population and prevention of MTCT for HIV-infected pregnant women. Existing evidence from a single study suggests that healthcare and treatment via home visitations have the potential to improve adherence to ART regimen. Community-based provision of HAART to HIV-positive pregnant women led to significant decrease in stillbirths, although these findings are based on a single study. We did not find any impact of CBIs on prevention of MTCT, LBW, and HIV/AIDS associated morbidity and mortality. We could not conduct any subgroup analyses for the relative effectiveness of integrated and non-integrated delivery strategies in our review since all the studies were delivered in non-integrated manner. Existing systematic reviews on community-based HIV/AIDS prevention and control programs are limited in their scope as they either evaluate the effectiveness of a single intervention, or interventions targeted at a specific population group [38-43].

With HIV still being a global epidemic, it is crucial that efforts be undertaken to utilize existing community-based infrastructure to introduce interventions for HIV prevention and also target the most vulnerable population groups. Many of the risk factors for HIV/AIDS including drug abuse and unsafe sexual practices are initiated in the adolescent age group. Targeting preventive interventions towards adolescence presents a window of opportunity to reduce the future burden of HIV/AIDS and allows time for maximum impact on health to be achieved in the years ahead. Based on our review findings, community-based preventive health education and counseling, abstinence and HIV risk reduction, and street outreach interventions are effective in improving a range of knowledge, attitudes, and behavior outcomes. These interventions should be scaled-up at the community level to target high-risk population groups, including adolescents, to improve HIV/AIDS related knowledge and modify sexual risk behaviors to prevent HIV. However, implementation, scaling-up, and sustainability may be difficult to achieve and need careful consideration [44-47].

We found a dearth of evidence on the effectiveness of CBIs targeting HIV-infected population groups, and pregnant and lactating women living with HIV. Targeting pregnant women with HIV is critical as prevention of MTCT would not be possible if this group remains neglected [48]. The coverage of effective ART regimens in LMICs for preventing MTCT was 57% in 2011, and a lot still needs to be done to eliminate it completely. Nearly half of all children newly infected with HIV in 20 countries in Africa are acquiring HIV during breastfeeding because of the low ART coverage their mothers receive. Various community delivery models for targeting pregnant women with HIV need to be evaluated for effectiveness to improve birth outcomes, HIV transmission, and maternal and neonatal morbidity and mortality. Integrating HIV voluntary testing, counseling, and treatment with routine community delivered antenatal care (ANC) in high-risk areas could potentially improve coverage and reduce the risk of MTCT during pregnancy and lactation. In the 21 priority countries in Sub-Saharan Africa, services to prevent new HIV infections among children have been integrated into existing maternal and child health care [49]. Greater attention should be paid to the period before pregnancy to improve the rates of voluntary testing and counselling to prevent MTCT [50].

With the increasing risk of TB resurgence associated with HIV, various HIV and TB integrated models have also been proposed. The WHO estimates that the scale-up of collaborative HIV/TB activities (including HIV testing, ART, and recommended preventive measures) have stopped 1.3 million people from dying from 2005 to 2012 [1]. However, challenges persist, as progress in reducing TB-related deaths among people living with HIV has slowed in recent years [1]. In 2012, South Africa launched an integrated five-year strategy addressing HIV, TB, and sexually- transmitted infections. Similarly, in Malawi, the number of facilities providing integrated HIV and sexual and reproductive health services have increased [49]. Large-scale community intervention models have been launched in Malawi, Mozambique, and South Africa involving decentralization of care and delegation to non-clinician physicians [51]. However, there is still a need to rigorously evaluate the emerging new models of care for effectiveness in order to improve morbidity and mortality outcomes.

Conclusion

CBIs are effective in improving knowledge, attitudes, and practice outcomes. Future studies should focus on evaluating the effectiveness of community delivery platforms for prevention of MTCT, and various emerging models of care to improve morbidity and mortality outcomes.

Abbreviations

ANC: Antenatal care; ARV: Antiretroviral; ART: Antiretroviral therapy; CBI: Community-Based Intervention; IDoP: Infectious diseases of poverty; LMIC: Low- middle-income country; MTCT: Mother-to-Child Transmission; WHO: World Health Organization.

Competing interests

The authors declare that they have no financial or non-financial competing interests.

Authors’ contributions

ZAB was responsible for designing and coordinating the review. SH and HHA were responsible for the data collection, screening of the search results, screening of the retrieved papers against inclusion criteria, appraising the quality of papers, and abstracting the data. RAS and JKD were responsible for data interpretation and writing the review. ZAB critically reviewed and modified the manuscript. All authors read and approved the final manuscript.

Supplementary Material

Multilingual abstracts in the six official working languages of the United Nations.

Contributor Information

Rehana A Salam, Email: rehana.salam@aku.edu.

Sarah Haroon, Email: sarahharoonkhan@gmail.com.

Hashim H Ahmed, Email: hashimhussnain@gmail.com.

Jai K Das, Email: jai.das@aku.edu.

Zulfiqar A Bhutta, Email: zulfiqar.bhutta@sickkids.ca.

Acknowledgements

The collection of scoping reviews in this special issue of Infectious Diseases of Poverty was commissioned by the UNICEF/UNDP/World Bank/WHO Special Programme for Research and Training in Tropical Diseases (TDR) in the context of a Contribution Agreement with the European Union for “Promoting research for improved community access to health interventions in Africa”.

References

- Bakamjian L Neggers Y Crowe K Geelhoed D Lafort Y Chissale E Candrinho B Degomme O Barbiero VK Bollinger L Global report: UNAIDS report on the global AIDS epidemic 2013 J Am Board Fam Med 2013262187–195.23471933 [Google Scholar]

- World Bank and HIV/AIDS: the facts. http://go.worldbank.org/KD7W8BE720.

- Sub-Saharan Africa. Regional Fact Sheet 2012. Geneva, Switzerland: The Joint United Nations Programme on HIV/AIDS (UNAIDS); 2012. [Google Scholar]

- Joint United Nations Programme on HIV/AIDS. Progress Report on the Global Plan Towards the Elimination of new HIV Infections Among Children by 2015 and Keeping Their Mothers Alive. Geneva, June: UNAIDS; 2013. [Google Scholar]

- Bhutta ZA, Sommerfeld J, Lassi ZS, Salam RA, Das JK. Global Burden, Distribution and Interventions for the Infectious Diseases of Poverty. Infect Dise of Pov. 2014;3:21. doi: 10.1186/2049-9957-3-21. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Merico F, Mngquandaniso N, Pertzera K, Allen C, Manyika P, Ufitamahoro E, Musabende A, Rich M, Zabat GM, Caoili JC. Community-based HIV interventions for young people. Afr J Tradit Complement Altern Med. 2013;5(4):419–420. [Google Scholar]

- Higgins JPT, Green S. Cochrane Handbook for Systematic Reviews of Interventions Version 5.1.0. [updated March 2011] 2011. (The Cochrane Collaboration). Available from [ www.cochrane-handbook.org]

- Lassi ZS, Salam RA, Das JK, Bhutta ZA, Lassi ZS, Salam RA, Das JK, Bhutta ZA. Conceptual framework and assessment methodology for the systematic review on community based interventions for the prevention and control of IDoP. Infect Dise of Pov. 2014;3:22. doi: 10.1186/2049-9957-3-22. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Aggarwal AK, Duggal M. Knowledge of men and women about reproductive tract infections and AIDS in a rural area of north India: impact of a community-based intervention. J Health Popul Nutr. 2004;22(4):413–419. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Baptiste DR, Bhana A, Petersen I, McKay M, Voisin D, Bell C, Martinez DD. Community collaborative youth-focused HIV/AIDS prevention in South Africa and Trinidad: preliminary findings. J Pediatr Psychol. 2006;31(9):905–916. doi: 10.1093/jpepsy/jsj100. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Berrien VM, Salazar JC, Reynolds E, McKay K. Adherence to antiretroviral therapy in HIV-infected pediatric patients improves with home-based intensive nursing intervention. AIDS Patient Care STDs. 2004;18(6):355–363. doi: 10.1089/1087291041444078. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rotheram-Borus MJ, Gwadz M, Fernandez MI, Srinivasan S. Timing of HIV interventions on reductions in sexual risk among adolescents. Am J Community Psychol. 1998;26(1):73–96. doi: 10.1023/a:1021834224454. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Harper GW, Bangi AK, Sanchez B, Doll M, Pedraza A. A quasi-experimental evaluation of a community-based HIV prevention intervention for Mexican American female adolescents: the SHERO’s program. AIDS Educ Prev. 2009;21(Supplement B):109–123. doi: 10.1521/aeap.2009.21.5_supp.109. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Heitgerd JL, Kalayil EJ, Patel-Larson A, Uhl G, Williams WO, Griffin T, Smith BD. Reduced sexual risk behaviors among people living with HIV: results from the Healthy Relationships outcome monitoring project. AIDS Behav. 2011;15(8):1677–1690. doi: 10.1007/s10461-011-9913-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McBride CK, Baptiste D, Traube D, Paikoff RL, Madison-Boyd S, Coleman D, Bell CC, Coleman I, McKay MM. Family-based HIV preventive intervention: child level results from the CHAMP family program. Soc Work Ment Health. 2007;5(1–2):203–220. doi: 10.1300/J200v05n01_10. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Middelkoop K, Myer L, Smit J, Wood R, Bekker L-G. Design and evaluation of a drama-based intervention to promote voluntary counseling and HIV testing in a South African community. Sex Transm Dis. 2006;33(8):524–526. doi: 10.1097/01.olq.0000219295.50291.1d. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Morisky DE, Ang A, Coly A, Tiglao TV. A model HIV/AIDS risk reduction programme in the Philippines: a comprehensive community-based approach through participatory action research. Health Promot Int. 2004;19(1):69–76. doi: 10.1093/heapro/dah109. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- O’Hara Murdock P, Lutchmiah J, Mkhize M. Peer led HIV/AIDS prevention for women in South African informal settlements. Health Care Women Int. 2003;24(6):502–512. doi: 10.1080/07399330303975. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nelson K, Tom N. Evaluation of a substance abuse, HIV and hepatitis prevention initiative for urban Native Americans: the native voices program. J Psychoactive Drugs. 2012;43(4):349–354. doi: 10.1080/02791072.2011.629158. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Norr K, Tlou S, Moeti M. Impact of peer group education on HIV prevention among women in Botswana. Health Care Women Int. 2004;25(3):210–226. doi: 10.1080/07399330490272723. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pearlman DN, Camberg L, Wallace LJ, Symons P, Finison L. Tapping youth as agents for change: evaluation of a peer leadership HIV/AIDS intervention. J Adolesc Health. 2002;31(1):31–39. doi: 10.1016/s1054-139x(02)00379-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wendell DA, Cohen DA, LeSage D, Farley TA. Street outreach for HIV prevention: effectiveness of a state-wide programme. Int J STD AIDS. 2003;14(5):334–340. doi: 10.1258/095646203321605549. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Williams AB, Fennie KP, Bova CA, Burgess JD, Danvers KA, Dieckhaus KD. Home visits to improve adherence to highly active antiretroviral therapy: a randomized controlled trial. JAIDS. 2006;42(3):314–321. doi: 10.1097/01.qai.0000221681.60187.88. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Carlson M, Brennan RT, Earls F. Enhancing adolescent self-efficacy and collective efficacy through public engagement around HIV/AIDS competence: A multilevel, cluster randomized-controlled trial. Soc Sci Med. 2012;75(6):1078–1087. doi: 10.1016/j.socscimed.2012.04.035. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chhabra R, Springer C, Leu C-S, Ghosh S, Sharma SK, Rapkin B. Adaptation of an alcohol and HIV school-based prevention program for teens. AIDS Behav. 2010;14(1):177–184. doi: 10.1007/s10461-010-9739-3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Clark LF, Miller KS, Nagy SS, Avery J, Roth DL, Liddon N, Mukherjee S. Adult identity mentoring: reducing sexual risk for African-American seventh grade students. J Adolesc Health. 2005;37(4):337. e331–337. e310. doi: 10.1016/j.jadohealth.2004.09.024. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Huba GJ, Cherin DA, Melchior LA. Retention of clients in service under two models of home health care for HIV/AIDS. Home Health Care Serv Q. 1999;17(3):17–26. doi: 10.1300/j027v17n03_02. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jemmott Iii JB, Jemmott LS, O’Leary A, Ngwane Z, Icard LD, Bellamy SL, Jones SF, Landis JR, Heeren GA, Tyler JC. School-based randomized controlled trial of an HIV/STD risk-reduction intervention for South African adolescents. Arch Pediatr Adolesc Med. 2010;164(10):923. doi: 10.1001/archpediatrics.2010.176. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kiene SM, Barta WD. A brief individualized computer-delivered sexual risk reduction intervention increases HIV/AIDS preventive behavior. J Adolesc Health. 2006;39(3):404–410. doi: 10.1016/j.jadohealth.2005.12.029. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Klepp K-I, Ndeki SS, Leshabari MT, Hannan PJ, Lyimo BA. AIDS education in Tanzania: promoting risk reduction among primary school children. Am J Public Health. 1997;87(12):1931–1936. doi: 10.2105/ajph.87.12.1931. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Munodawafa D, Marty PJ, Gwede C. Effectiveness of health instruction provided by student nurses in rural secondary schools of Zimbabwe: a feasibility study. Int J Nurs Stud. 1995;32(1):27–38. doi: 10.1016/0020-7489(94)00029-j. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Selke HM, Kimaiyo S, Sidle JE, Vedanthan R, Tierney WM, Shen C, Denski CD, Katschke AR, Wools-Kaloustian K. Task-shifting of antiretroviral delivery from health care workers to persons living with HIV/AIDS: clinical outcomes of a community-based program in Kenya. JAIDS. 2010;55(4):483–490. doi: 10.1097/QAI.0b013e3181eb5edb. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shapiro RL, Hughes MD, Ogwu A, Kitch D, Lockman S, Moffat C, Makhema J, Moyo S, Thior I, McIntosh K. Antiretroviral regimens in pregnancy and breast-feeding in Botswana. N Engl J Med. 2010;362(24):2282–2294. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa0907736. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Blake SM, Ledsky R, Goodenow C, Sawyer R, Lohrmann D, Windsor R. Condom availability programs in Massachusetts high schools: relationships with condom use and sexual behavior. Am J Public Health. 2003;93(6):955–962. doi: 10.2105/ajph.93.6.955. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chen X, Stanton B, Gomez P, Lunn S, Deveaux L, Brathwaite N, Li X, Marshall S, Cottrell L, Harris C. Effects on condom use of an HIV prevention programme 36 months postintervention: a cluster randomized controlled trial among Bahamian youth. Int J STD AIDS. 2010;21(9):622–630. doi: 10.1258/ijsa.2010.010039. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Visser MJ. Life skills training as HIV/AIDS preventive strategy in secondary schools: evaluation of a large-scale implementation process. SAHARA J. 2005;2(1):203–216. doi: 10.1080/17290376.2005.9724843. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Walker D, Gutierrez JP, Torres P, Bertozzi SM. HIV prevention in Mexican schools: prospective randomised evaluation of intervention. BMJ. 2006;332(7551):1189. doi: 10.1136/bmj.38796.457407.80. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Underhill K, Operario D, Montgomery P. Abstinence-only programs for HIV infection prevention in high-income countries. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2007;4(4):CD005421. doi: 10.1002/14651858.CD005421.pub2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ng BE, Butler LM, Horvath T, Rutherford GW. Population-based biomedical sexually transmitted infection control interventions for reducing HIV infection. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2011;3(3):CD001220. doi: 10.1002/14651858.CD001220.pub3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Djossa Adoun MAS, Gagnon M-P, Godin G, Tremblay N, Njoya MM, Ratte S, Gagnon H, Cote J, Miranda J, Ly BA. Information and communication technologies (ICT) for promoting sexual and reproductive health (SRH) and preventing HIV infection in adolescents and young adults. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2011;2:CD009013. [Google Scholar]

- Skevington SM, Sovetkina EC, Gillison FB. A systematic review to quantitatively evaluate 'Stepping Stones’: a participatory community-based HIV/AIDS prevention intervention. AIDS Behav. 2013;17(3):1025–1039. doi: 10.1007/s10461-012-0327-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ross DA, Dick B, Ferguson J. Preventing HIV/AIDS in Young People: A Systematic Review of the Evidence from Developing Countries. Geneva, Switzerland: UNAIDS Inter-agency Task Team on Young People; 2006. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gallant M, Maticka-Tyndale E. School-based HIV prevention programmes for African youth. Soc Sci Med. 2004;58(7):1337–1351. doi: 10.1016/S0277-9536(03)00331-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sawyer SM, Afifi RA, Bearinger LH, Blakemore S-J, Dick B, Ezeh AC, Patton GC. Adolescence: a foundation for future health. Lancet. 2012;379(9826):1630–1640. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(12)60072-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Viner RM, Ozer EM, Denny S, Marmot M, Resnick M, Fatusi A, Currie C. Adolescence and the social determinants of health. Lancet. 2012;379(9826):1641–1652. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(12)60149-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Catalano RF, Fagan AA, Gavin LE, Greenberg MT, Irwin CE, Ross DA, Shek DTL. Worldwide application of prevention science in adolescent health. Lancet. 2012;379(9826):1653–1664. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(12)60238-4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Patton GC, Coffey C, Cappa C, Currie D, Riley L, Gore F, Degenhardt L, Richardson D, Astone N, Sangowawa AO. Health of the world’s adolescents: a synthesis of internationally comparable data. Lancet. 2012;379(9826):1665–1675. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(12)60203-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kosinski KC, Adjei MN, Bosompem KM, Crocker JJ, Durant JL, Osabutey D, Plummer JD, Stadecker MJ, Wagner AD, Woodin M, Gute D. Effective control of Schistosoma haematobium infection in a Ghanaian community following installation of a water recreation area. PLoS Negl Trop Dis. 2012;6(7):e1709. doi: 10.1371/journal.pntd.0001709. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- UNAIDS. World AIDS Day Report: Results. Geneva, Switzerland: Joint United Nations Programme on HIV/AIDS (UNAIDS); 2012. Available at http://www.unaids.org/en/media/unaids/contentassets/documents/epidemiology/2012/gr2012/jc2434_worldaidsday_results_en.pdf. [Google Scholar]

- Keiser J, Utzinger J. Efficacy of current drugs against soil-transmitted helminth infections: systematic review and meta-analysis. JAMA. 2008;299(16):1937–1948. doi: 10.1001/jama.299.16.1937. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- UNAIDS. Closer to Home: Delivering antiretroviral therapy in the community. M Sans Frontieres. 2012. Available at http://issuu.com/msf_access/docs/aids_report_closertohome_eng_2012/17?e=0.

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Multilingual abstracts in the six official working languages of the United Nations.