Abstract

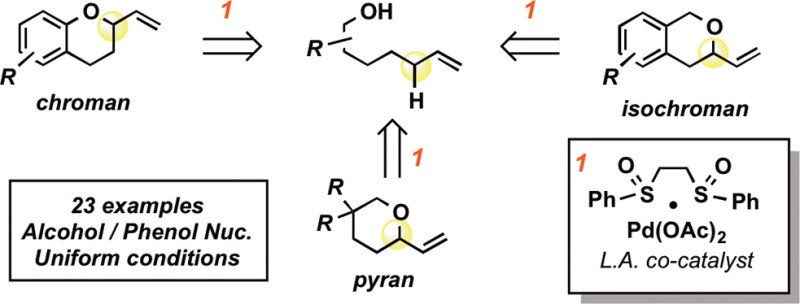

The synthesis of chroman, isochroman, and pyran motifs has been accomplished via a combination of Pd(II)/bis-sulfoxide C–H activation and Lewis acid co-catalysis. A wide range of alcohols are found to be competent nucleophiles for the transformation under uniform conditions (catalyst, solvent, temperature). Mechanistic studies suggest that the reaction proceeds via initial C–H activation followed by a novel inner-sphere functionalization pathway. Consistent with this, the reaction shows reactivity trends orthogonal to those of traditional Pd(0)-catalyzed allylic substitutions.

Selective C–H oxidation reactions enable streamlining synthetic routes due to their ability to introduce oxygen and nitrogen functionality under conditions orthogonal to those of traditional acid–base methods.1 Often, this is because novel metal-promoted pathways are accessed to effect electrophile and nucleophile activation. Here we report a Pd(II)/sulfoxide-catalyzed allylic C–H oxidation reaction that proceeds under neutral and uniform conditions to provide access to a wide range of oxygen heterocycles including benzopyran and pyran motifs.

Oxygen-containing heterocycles are widely sought for their significant biological properties.2 Pyrans and benzopyran motifs, such as chromans and isochromans, are pervasive structural elements in biologically relevant small molecules (Chart 1), as displayed by antihypertensive agent 1, opiod σ receptor antagonist 2, and Ficus microcarpa natural product ficuspirolide 3.3 Reported methods for accessing such oxygen heterocycle motifs are highly varied and generally necessitate the use of preoxidized starting materials.4 Prominently, much work has focused on processes that proceed via Pd(II) oxypalladation or Pd(0) allylic substitution methods, in some cases with high levels of asymmetric induction,5b,5c,6b−6d utilizing stereochemically defined internal olefins as precursors.5,6

Chart 1.

Pd(II)/bis-sulfoxide-catalyzed allylic C–H functionalizations of terminal olefins have shown broad applicability in synthetic methodology.7 We sought to apply a C–H activation strategy toward a general method for the synthesis of cyclic ether motifs starting from monooxygenated terminal olefin substrates. However, nucleophiles used for allylic C–H functionalization under the mild conditions of palladium sulfoxide catalysis have uniformly possessed pKa’s under 6.7−9 Higher-basicity nucleophiles impede the catalytic cycle either by deactivating the Pd catalyst or failing to undergo deprotonation under the reaction conditions whose only sources of base (the acetate counterion and dihydroquinone generated upon Pd reoxidation) are weak and catalytic.7e With pKa’s ranging from ∼10 for phenol to >15 for aliphatic alcohols, alcohols represented a major hurdle for allylic oxidations. Initial intermolecular experiments with terminal olefins and excess phenols consistently showed no desired products. Inspired by our oxidative macrolactonization and diol-forming reactions, we envisioned that rendering the reaction intramolecular might promote alcohol complexation to the Pd, with concomitant acidification enabling deprotonation under neutral conditions.8,9 Moreover, functionalization (C–O bond formation) may proceed via an inner-sphere reductive elimination mechanism that could have orthogonal scope to classic Pd(0) methods.8a,10

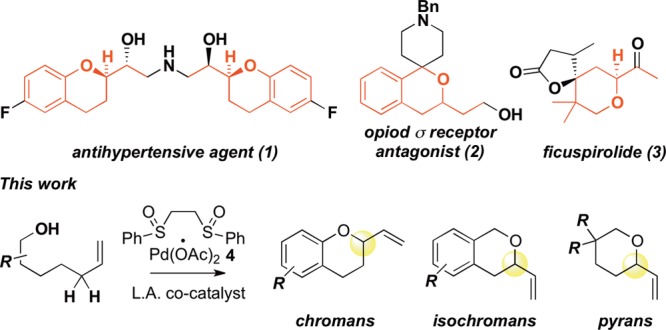

Preliminary evaluation of standard Pd(II)/bis-sulfoxide conditions using commercial catalyst 4 furnished chroman 6a in a modest 18% yield from phenol 5a (Table 1, entry 1). Increasing the concentration of weak base in solution via addition of catalytic DIPEA shut down reactivity (entry 2).11 We have previously demonstrated that catalytic amounts of both aza- and oxophilic Lewis acids (LAs) enhance the reactivity of allylic C–H functionalizations. Whereas the addition of catalytic amounts of B(C6F5)3 did not increase the yield (entry 3),12 inclusion of the oxophilic LA Cr(salen)Cl resulted in an increase to 40% yield (entry 4)7b,9,13 that was further enhanced in 1,2-dichloroethane solvent (79% yield, entry 5). Use of a less-coordinating BF4 counterion on the Cr LA diminished reactivity; however, use of an analogous, square planar porphyrin ligand resulted in nearly identical yields of 6a (entries 6,7). Significantly, a Mn(salen)Cl co-catalyst, previously shown to promote 4-catalyzed intermolecular C–H aminations, also effected a promising improvement in yield (entry 8).7b Removal of the co-catalyst from these optimized reaction conditions resulted in a dramatic decrease in yield (entry 9). Substitution of catalyst 4 for Pd(OAc)2 resulted in only trace yield (<5%) of product, supporting the hypothesis that the reaction proceeds via a C–H cleavage/π-allylPd functionalization pathway (entry 10). Consistent with the need for a π-acidic ligand capable of binding to Pd for the Cr co-catalyst effect, the more sterically bulky 2,6-dimethylbenzoquinone caused the reaction to proceed with greatly diminished yield (entry 11).13 Significantly, the loading of Pd catalyst 4 may be cut in half (5 mol%) with only a minor decrease in yield if reaction times are extended (entry 12).

Table 1. Reaction Development.

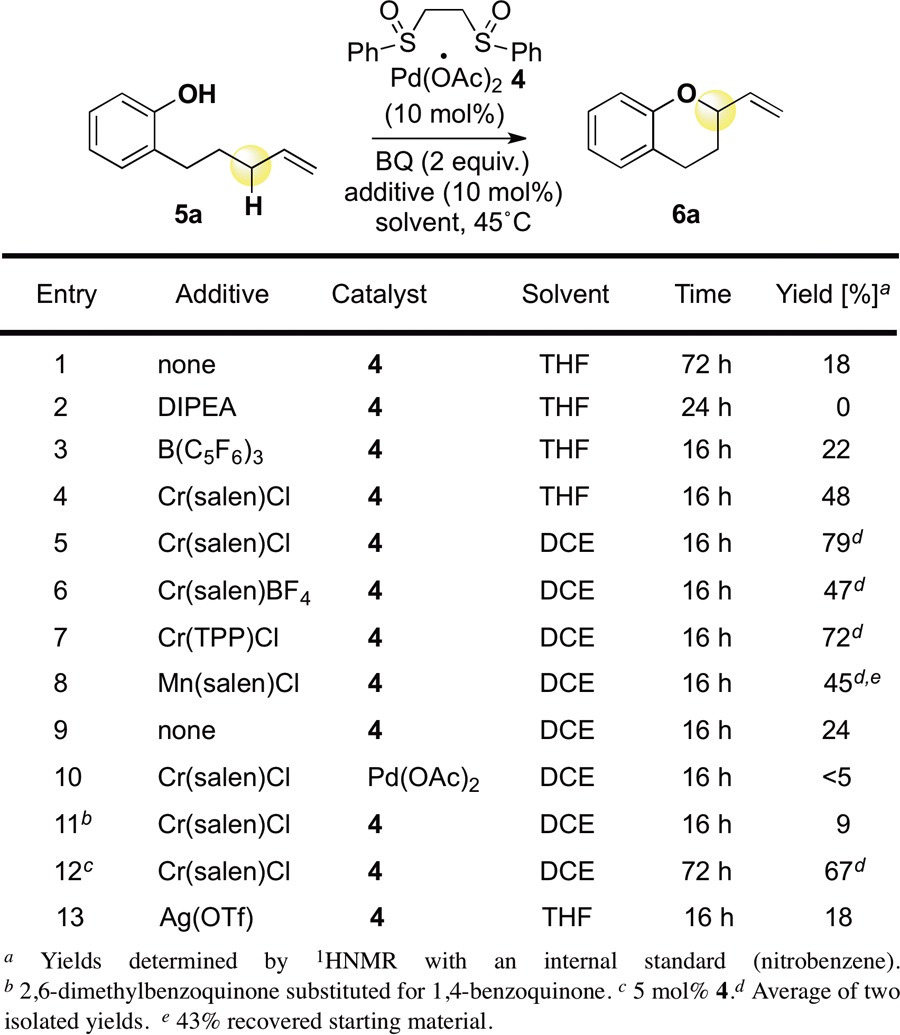

We next examined the scope of this method for furnishing the 2-vinylchroman motif. Gratifyingly, aromatic substitution shows broad tolerance for both electron-donating substituents (Table 2, products 6b, 6c, 6j) and electron-withdrawing substituents (products 6d–6i, 6k, 6l). It is significant to note that even the highly electron-withdrawing trifluoromethyl and nitro groups furnish chroman products in good yields. This is in contrast the reaction under Pd(0) allylic substitution conditions, where poor reactivity was observed with weakly nucleophilic phenols (vide infra).14 Chloride and bromide substituents are well tolerated under these oxidative conditions (products 6e–6g) and serve as handles for further manipulation. Importantly, representative substrates were selected to illustrate tolerance for substitution on the alkyl chain. The bulky ketal-substituted product 6m is obtained in 65% yield, serving as a masked ketone to access chromanone motifs. Oxygen substitution on the alkyl chain furnishes benzodioxan 6n; similarly, nitrogen substitution allows for formation of dihydro-2,4-benzoxazine product 6o. Additionally, we were gratified to find that the reaction may be scaled-up 50-fold without any diminishment in yield (product 6a).

Table 2. Chroman Formation.

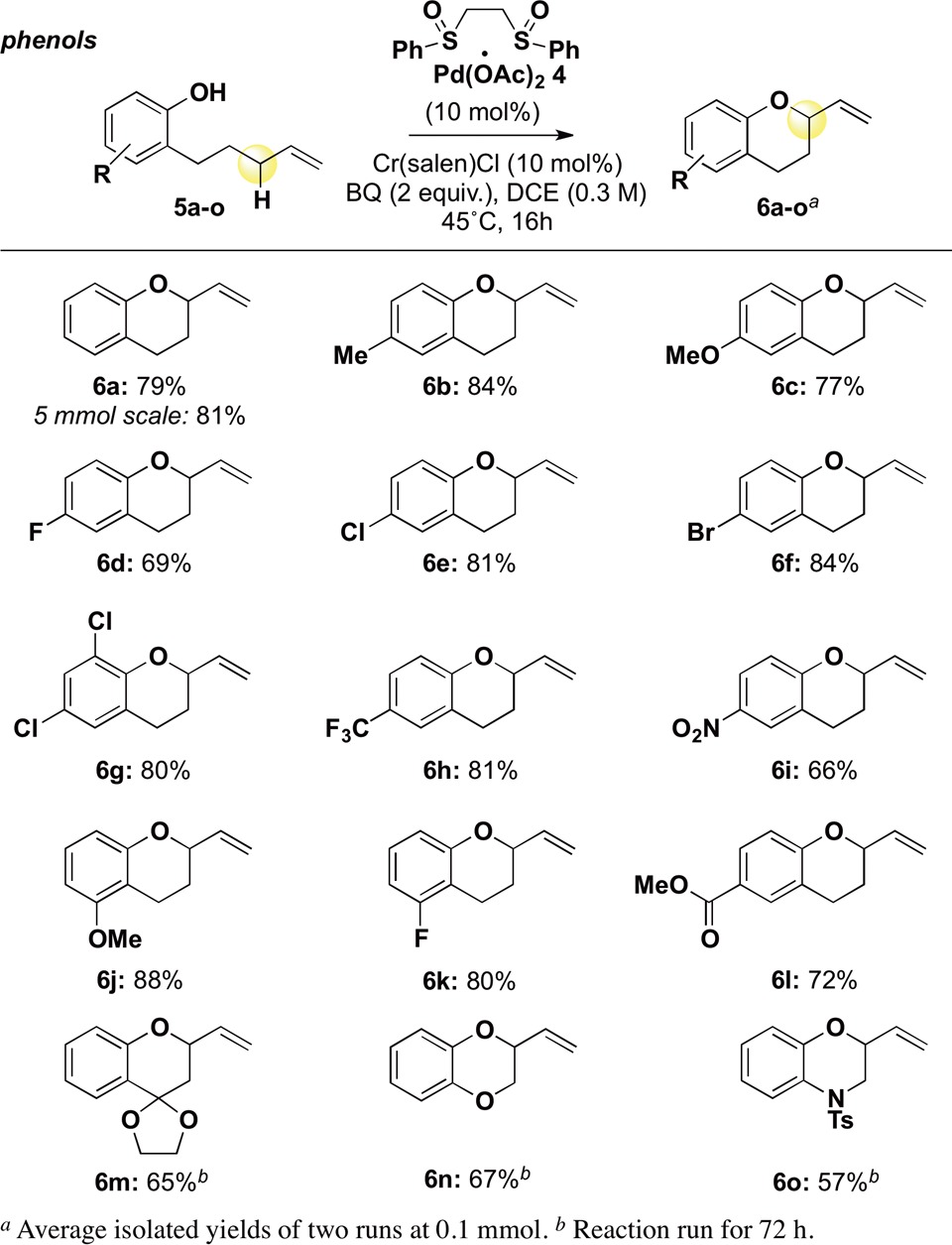

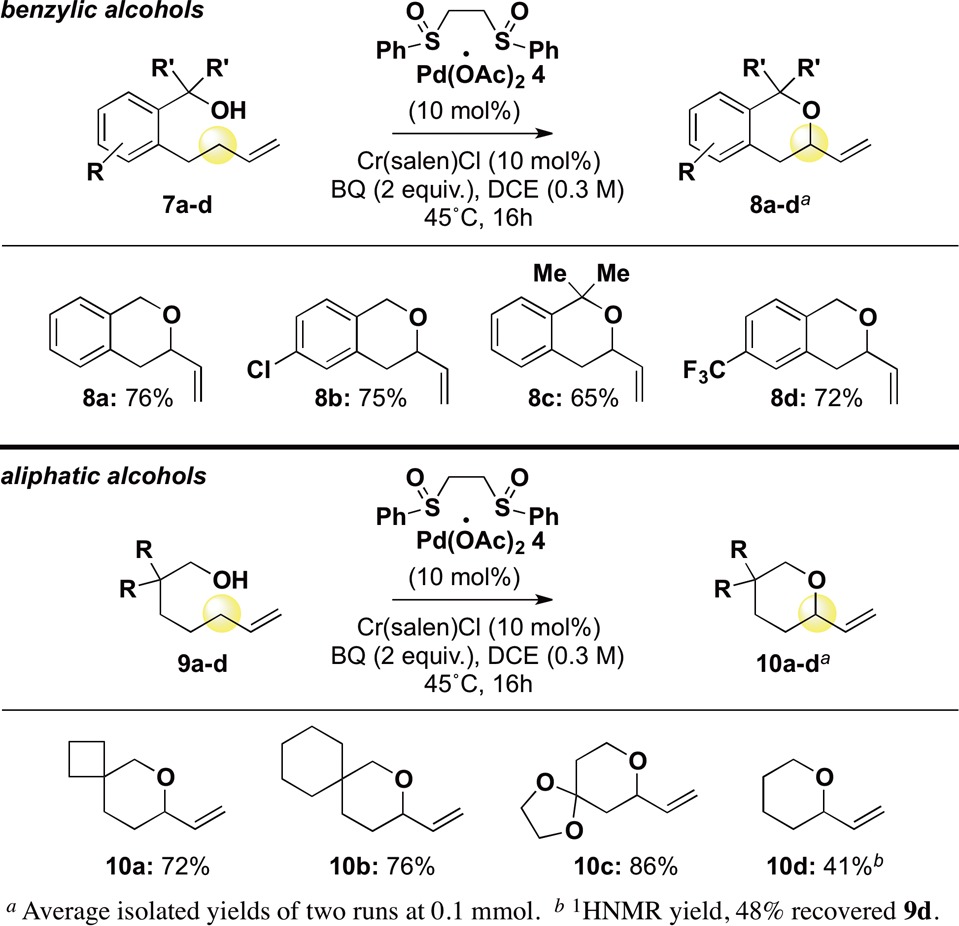

We hypothesized that such a chelation approach to nucleophile activation may extend beyond phenols to other, significantly less acidic alcohols such as benzylic and even aliphatic alcohols (pKa = 15–16). We were delighted to discover that benzyl alcohol 7a is converted into 3-vinyl-2-isochroman 8a in good yield under reaction conditions identical to those used for chroman synthesis (Table 3). Electronic substitution of the aromatic ring is also well tolerated, with chloride- and trifluoromethyl-substituted isochromans produced in good yields (products 8b and 8d, respectively). Additionally, we were pleased to observe that bulky geminal dimethyl-substituted product 8c is furnished in 65% yield. Given the facile nature of this reaction irrespective of the electronic nature of the alcohol nucleophile, aliphatic alcohols may also function as nucleophiles to furnish pyran motifs. We found that the reaction of primary alcohols 9a–9c proceeds under conditions identical to those employed for phenols and benzyl alcohols to furnish 2-vinylpyran products 10a–10c in good yields. While gem-disubstitution is beneficial for cyclization, it is not a requirement for reactivity (Table 3, 10d).

Table 3. Isochroman and Pyran Formation.

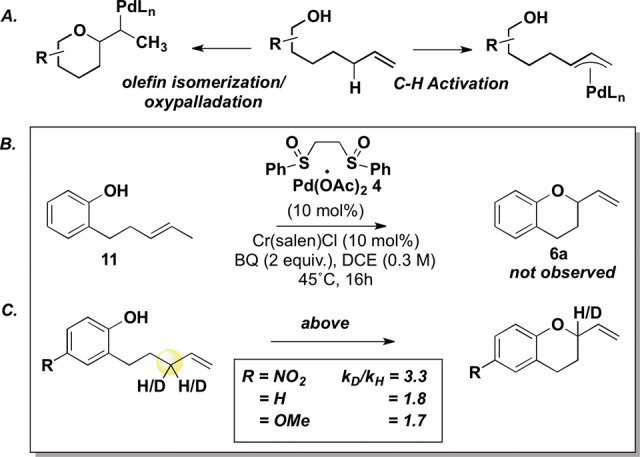

The unexpectedly broad nucleophile scope led us to examine the reaction mechanism. Benzopyrans have been generated via Pd(II)-mediated oxypalladation mechanisms from internal olefins, prompting us to evaluate an olefin isomerization/oxypalladation mechanism (Scheme 1A).5 When internal olefin 11 was subjected to the reaction conditions, minimal conversion and, critically, no chroman product was observed (Scheme 1B). Previous studies support that Pd(II)/bis-sulfoxide promotes C–H cleavage from terminal olefins to furnish π-allylPd intermediates, and we sought to evaluate if such a mechanism operates here.7b,8a,13 Isotope labeling studies were undertaken, where separate rate constants were measured for reactions proceeding with allylic hydrogen or deuterium. Interestingly, a range of kinetic isotope effects (KIEs) were observed, depending on the nature of the alcohol (Scheme 1C). With phenol nucleophiles of weak nucleophilicity and modest acidity, KIEs of 1.7–1.8 were measured, whereas a KIE of 3.3 was measured for phenol 5i, with a significantly lower pKa. This is consistent with a scenario where neither C–H cleavage nor deprotonation/functionalization (C–O bond formation) is completely rate-determining, and the observed KIE reflects multiple steps.15

Scheme 1. Mechanistic Experiments: Oxypalladation versus C–H Cleavage.

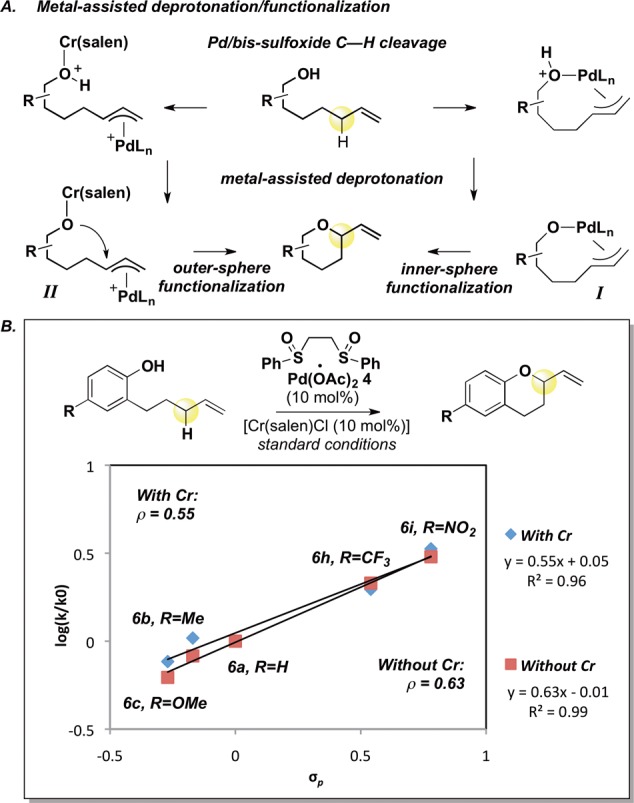

In considering the functionalization mechanism, metal-assisted alcohol deprotonation is necessary to acidify the O–H bond and enable soft deprotonation with the weak acetate and/or dihydroquinone base.16 Significantly, the course for functionalization may be determined by the metal assisting in deprotonation: π-allylPd coordination/deprotonation generates I, the precursor for inner-sphere functionalization at the Pd, whereas Cr(salen)-assisted deprotonation would promote in an outer-sphere delivery to the π-allylPd via II (Scheme 2A). To evaluate the latter possibility, a Hammett analysis of the reaction catalyzed by both Pd(II)/bis-sulfoxide 4 and Cr(salen)Cl was compared to a second Hammett analysis of the background reaction catalyzed only by 4 (Scheme 2B). The absence of a significant change in ρ values leads us to favor a mechanism whereby deprotonation and functionalization occur at Pd.

Scheme 2. Functionalization Step: Mechanistic Examination.

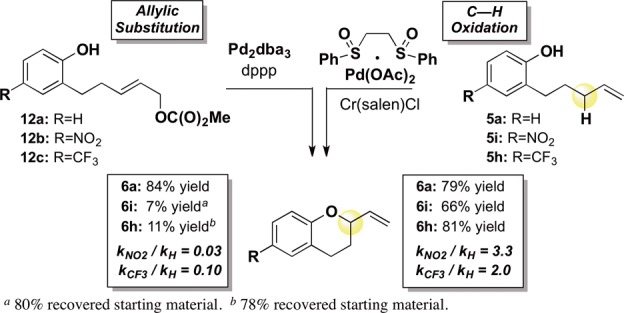

Dissociation of the alkoxide from π-allylPd I followed by an outer-sphere π-allylPd functionalization should show a reactivity trend analogous to that of Pd(0)-mediated allylic substitution reactions known to proceed via outer-sphere alkoxide functionalization of π-allylPd.6,14,17 We examined the yields and initial rates of chroman formation for Pd(0)-mediated allylic substitution with electron-deficient and electron-neutral substrates and compared them to those of the allylic C–H oxidation reaction (Scheme 3). When allylic carbonate substrate 12a, containing an electron-neutral phenol, was subjected to standard Pd(0) allylic substitution conditions, 2-vinylchroman 6a was formed in good yield (84%); however, when p-nitrophenol and p-trifluoromethyl substrates12b and 12c were exposed to identical Pd(0) conditions, reactivity was significantly retarded (7% and 11% yields, respectively, Scheme 3). In both cases, this drop in reactivity correlates with a significant decrease in reaction rate (kNO2/kH = 0.03; kCF3/kH = 0.10).14 In contrast, chroman yields for allylic C–H oxidation do not show a significant dependence on the electronic properties of the alcohol, and the Hammett analysis of the Pd(II)/bis-sulfoxide/Cr(salen)Cl-catalyzed allylic C–H oxidation reaction reveals that the reaction rate is modestly enhanced by electron-withdrawing groups on the phenol pro-nucleophile, presumably reflecting a more facile deprotonation (kNO2/kH = 3.3; kCF3/kH = 2.0) (Schemes 2 and 3).18 Such dramatic switches in reactivity and reaction rate trends are unlikely to be due to the different mechanisms for π-allylPd formation; thus, we take this as further evidence of a major deviation from the classical outer-sphere functionalization model. Although we cannot definitively rule out all outer-sphere functionalization pathways, on the basis of evidence presented we view it as highly unlikely.19 Broad nucleophile scope is likely a consequence of such a metal-chelation approach, serving as a “dampening effect” for the nucleophiles’ electronic character. We have previously provided evidence that Pd(II)/sulfoxide-catalyzed C–H functionalizations with oxygen nucleophiles (e.g., carboxylates) proceed via an inner-sphere reductive elimination step.7a,8a,9 The mechanistic findings herein constitute further evidence for such a pathway.

Scheme 3. Allylic C–H Oxidation versus Allylic Substitution.

In summary, we have developed a general Pd(II)/bis-sulfoxide-catalyzed allylic oxidation method to afford for the first time direct access to chroman, isochroman, and pyran motifs starting from terminal olefins. This operationally simple method (open to air and moisture) proceeds with high substrate generality under uniform conditions (catalyst, solvent, temperature). Its low sensitivity to the electronic nature of the alcohol nucleophile, along with inverse electronic trends observed for reaction rate relative to outer-sphere Pd(0)-catalyzed allylic substitutions, argues for an allylic C–H functionalization mechanism proceeding via inner-sphere Pd coordination/activation of the oxygen nucleophile and subsequent reductive elimination. We anticipate that this general strategy will help to broaden the scope of pro-nucleophiles used in C–H functionalization reactions.

Acknowledgments

Financial support provided by the NIH/NIGMS (2R01 GM 076153B). S.E.A. is a NSF Graduate Research Fellow. We thank Matt Kolaczkowski for help with substrate synthesis, Johnson Matthey for a gift of Pd(OAc)2, and Dr. Jennifer M. Howell for checking the experimental in Table 3, entry 8c.

Supporting Information Available

Experimental details and characterization data. This material is available free of charge via the Internet at http://pubs.acs.org.

Author Present Address

‡ G.T.R. is now a student at Duke Law School.

The authors declare no competing financial interest.

Funding Statement

National Institutes of Health, United States

Supplementary Material

References

- a Crabtree R. H. J. Chem. Soc., Dalton Trans. 2001, 2437. [Google Scholar]; b Labinger J. A.; Bercaw J. E. Nature 2002, 417, 507. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; c Dick A. R.; Sanford M. S. Tetrahedron 2006, 62, 2439. [Google Scholar]; d Giri R.; Shi B.-F.; Engle K. M.; Maugel N.; Yu J. Q. Chem. Soc. Rev. 2009, 38, 3242. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; e White M. C. Science 2012, 335, 807. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; f Che C.-M.; Lo V. K.-Y.; Zhou C.-Y.; Huang J.-S. Chem. Soc. Rev. 2011, 40, 1950. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- a Ellis G. P.; Lockhart I. M.. The Chemistry of Heterocyclic Compounds, Chromenes, Chromanones, and Chromones; Wiley: New York, 2007. [Google Scholar]; b Nicolaou K. C.; Pfefferkorn J. A.; Barluenga S.; Mitchell H. J.; Roecker A. J.; Cao G.-Q. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2000, 122, 9968. [Google Scholar]

- a De Cree J.; Geukens H.; Leempoels J.; Verhaegen H. Drug Dev. Res. 1986, 8, 109. [Google Scholar]; b Maier C. A.; Wünsch B. J. Med. Chem. 2002, 45, 4923. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; c Kuo Y.-H.; Li Y.-C. Chem. Pharm. Bull. 1999, 47, 299. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Reviews:; a Tang Y.; Oppenheimer J.; Song Z.; You L.; Zhang X.; Hsung R. P. Tetrahedron 2006, 62, 10785. [Google Scholar]; b Shen H. C. Tetrahedron 2009, 65, 3931. [Google Scholar]; c Shi Y.-L.; Shi M. Org. Biomol. Chem. 2007, 5, 1499. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; d Zeni G.; Larock R. C. Chem. Rev. 2006, 106, 4644. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pd(II):; a Hosokawa T.; Kono T.; Shinohara T.; Murahashi S.-I. J. Organomet. Chem. 1989, 370, C13. [Google Scholar]; b Trend R. M.; Ramtohul Y. K.; Stoltz B. M. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2005, 127, 17778. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; c Cannon J. S.; Olson A. C.; Overman L. E.; Solomon L. E. J. Org. Chem. 2012, 77, 1961. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; d Semmelhack M. F.; Bodurow C. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 1984, 106, 1496. [Google Scholar]; e Ward A. F.; Xu Y.; Wolfe J. P. Chem. Commun. 2012, 48, 609. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pd(0):; a Larock R. C.; Berrios-Peña R. C.; Fried C. A.; Yum E. K.; Tu C.; Leong W. J. Org. Chem. 1993, 58, 4509. [Google Scholar]; b Trost B. M.; Toste F. D. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 1998, 120, 9074. [Google Scholar]; c Trost B. M.; Shen H. C.; Dong L.; Surivet J.-P. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2003, 125, 9276. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; d Trost B. M.; Shen H. C.; Dong L.; Surivet J.-P.; Sylvain C. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2004, 126, 11966. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- a Chen M. S.; Prabagaran N.; Labenz N. A.; White M. C. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2005, 127, 6970. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; b Reed S. A.; White M. C. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2008, 130, 3316. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; c Lin S.; Song C.-X.; Cai G.-X.; Wang W.-H.; Shi Z.-J. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2008, 130, 12901. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; d Young A. J.; White M. C. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2008, 130, 14090. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; e Rice G. T.; White M. C. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2009, 131, 11707. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; f Braun M.-G.; Doyle A. G. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2013, 135, 12990. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- a Fraunhoffer K. J.; Prabagaran N.; Sirois L. E.; White M. C. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2006, 128, 9032. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; b Gade N. R.; Iqbal J. Tetrahedron Lett. 2013, 54, 4225. [Google Scholar]

- Gormisky P. E.; White M. C. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2011, 133, 12584. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- A seminal example of Pd-catalyzed inner-sphere acetoxylation of cyclohexadiene:; Bäckvall J.-E.; Byström S. E.; Nordberg R. E. J. Org. Chem. 1984, 49, 4619. [Google Scholar]

- Reed S. A.; Mazzotti A. R.; White M. C. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2009, 131, 11701. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Strambeanu I. I.; White M. C. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2013, 135, 12032. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- a Covell D. J.; White M. C. Angew. Chem., Int. Ed. 2008, 47, 6448. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; b Hansen K. B.; Leighton J. L.; Jacobsen E. N. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 1996, 118, 10924. [Google Scholar]

- Pd(0)-catalyzed functionalizations show diminished intermolecular reactivity with electron-deficient phenols:; a Goux C.; Massacret M.; Lhoste P.; Sinou D. Organometallics 1995, 14, 4585. [Google Scholar]; b Goux C.; Lhoste P.; Sinou D. Synlett 1992, 725. [Google Scholar]; c Fang P.; Ding C.-H.; Hou X.-L.; Dai L.-X. Tetrahedron: Asymmetry 2010, 21, 1176. [Google Scholar]

- a Simmons E. M.; Hartwig J. F. Angew. Chem., Int. Ed. 2012, 51, 3066. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; b Bercaw J. E.; Hazari N.; Labinger J. A.; Oblad P. F. Angew. Chem., Int. Ed. 2008, 47, 9941. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Proposed metal-assisted deprotonation/reductive elimination in Pd(0)-catalyzed aryl etherification:Palucki M.; Wolfe J. P.; Buchwald S. L. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 1996, 118, 10333. [Google Scholar]

- Trost B. M.; Dirat O.; Dudash J. Jr.; Hembre E. J. Angew. Chem., Int. Ed. 2001, 40, 3658. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- A KIE of 5.2 for aliphatic alcohol 9b, along with a 2-fold rate increase of 9b compared to phenol 5a, indicates that a trend based purely on nucleophile pKa does not apply to all alcohols and different aspects of the nucleophilicity must be considered.

- Attack of protonated alcohol on the π-allylPd followed by deprotonation is also consistent with a faster rate for electron-deficient phenols.

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.