Abstract

The anti-cancer drug cisplatin is nephrotoxic and neurotoxic. Previous data support the hypothesis that cisplatin is bioactivated to a nephrotoxicant. The final step in the proposed bioactivation is the formation of a platinum-cysteine S-conjugate followed by a pyridoxal 5'-phosphate (PLP)-dependent cysteine S-conjugate β-lyase reaction. This reaction would generate pyruvate, ammonium and a highly reactive platinum (Pt)-thiol compound in vivo that would bind to proteins. In the present work, the cellular location and identity of the PLP-dependent cysteine S-conjugate β-lyase was investigated. Pt was shown to bind to proteins in kidneys of cisplatin-treated mice. The concentration of Pt-bound proteins was higher in the mitochondrial fraction than in the cytosolic fraction. Treatment of the mice with aminooxyacetic acid (AOAA, a PLP-enzyme inhibitor), which had previously been shown to block the nephrotoxicity of cisplatin, decreased the binding of Pt to mitochondrial proteins, but had no effect on the amount of Pt bound to proteins in the cytosolic fraction. These data indicate that a mitochondrial enzyme catalyzes the PLP-dependent cysteine S-conjugate β-lyase reaction. PLP-dependent mitochondrial aspartate aminotransferase (mitAspAT) is a mitochondrial enzyme that catalyzes β-elimination reactions with cysteine S-conjugates of halogenated alkenes. We reasoned that the enzyme might also catalyze a β-lyase reaction with the cisplatin-cysteine S-conjugate. In the present study mitAspAT was stably overexpressed in LLC-PK1 cells. Cisplatin was significantly more toxic in confluent monolayers of LLC-PK1 cells that overexpressed mitAspAT when compared to control cells containing vector alone. AOAA completely blocked the cisplatin toxicity in confluent mitAspAT-transfected cells. The Pt-thiol compound could rapidly bind proteins and inactivate enzymes in close proximity to the PLP-dependent cysteine S-conjugate β-lyase. Treatment with 50- or 100 µM cisplatin for 3 h, followed by removal of cisplatin from the medium for 24 h, resulted in a pronounced loss of α-ketoglutarate dehydrogenase complex (KGDHC) activity in both mitAspAT transfected cells and control cells. Exposure to 100 µM cisplatin resulted in a significantly greater loss of KGDHC activity in the cells overexpressing mitAspAT compared to control cells. Aconitase activity was diminished in both cell types, but only at the higher level of exposure to cisplatin. AspAT activity was also significantly decreased by cisplatin treatment. By contrast, several other enzymes (both cytosolic and mitochondrial) involved in energy/amino acid metabolism were not significantly affected by cisplatin treatment in the LLC-PK1 cells, whether or not mitAspAT was overexpressed. The susceptibility of KGDHC and aconitase to inactivation in kidney cells exposed to cisplatin metabolites may be due to the close proximity of mitAspAT to KGDHC/aconitase in mitochondria. The present findings support the hypothesis that a mitochondrial cysteine S-conjugate β-lyase converts the cisplatin-cysteine S-conjugate to a toxicant and the data are consistent with the hypothesis that mitAspAT plays a role in the bioactivation of cisplatin.

Cisplatin has been used successfully to treat a variety of cancers including testicular cancer, ovarian cancer and some glioblastomas (1). Unfortunately, the drug cannot be administered at high doses due to its toxicity to renal proximal tubules and its neurotoxicity (2,3). Studies from many laboratories have implicated DNA damage as the primary mechanism by which cisplatin kills tumor cells and other dividing cells (4,5). However, the renal proximal tubule cells are well-differentiated, non-dividing cells that are not killed by other DNA-damaging agents (6). Early work suggested that a metabolite of cisplatin is responsible for the nephrotoxicity (7). Several steps in the metabolic pathway through which cisplatin is bioactivated to a nephrotoxicant have recently been identified (8–13). In the present study we have focused on the identification of the enzyme(s) that catalyze the final step in the metabolism of cisplatin to a nephrotoxicant.

Inhibition of either γ-glutamyl transpeptidase (GGT1) or pyridoxal 5'-phosphate (PLP)-dependent enzymes blocks the nephrotoxicity of cisplatin both in vivo and in vitro (8–13). Buthionine sulfoximine, which depletes endogenous glutathione by inhibiting glutathione synthesis, also protects against cisplatin-induced nephrotoxicity (14). These findings indicate that cisplatin is metabolized to a nephrotoxicant through conversion of the drug to a glutathione S-conjugate, followed by steps that involve a GGT- and cysteine S-conjugate β-lyase-dependent pathway (8–13). The enzymatic steps involved in this proposed pathway for the bioactivation of cisplatin are similar to those previously established for the bioactivation of several halogenated alkenes to nephrotoxicants (15,16). Bioactivation of halogenated alkenes involves the sequential formation of the glutathione-, cysteinylglycine- and cysteine S-conjugates. The final step in the bioactivation pathway of halogenated alkenes is a β-elimination reaction on the corresponding cysteine S-conjugate, catalyzed by cysteine S-conjugate β-lyase(s), yielding pyruvate, ammonium, and a highly reactive halogenated thiol-containing fragment. Halogenated thiol-containing fragments are rapidly converted non-enzymatically to products that thioacylate macromolecules in target cells (17–19).

Cytosolic, mitochondrial, and microsomal fractions of kidney homogenates have been shown to catalyze cysteine S-conjugate β-lyase reactions in vitro with halogenated cysteine S-conjugates (20–23). To date, at least eleven enzymes have been reported to catalyze cysteine S-conjugate β-lyase reactions with the nephrotoxicants S-(1,2--dichlorovinyl)-L-cysteine (DCVC) and S-(1,1,2,2-tetrafluoroethyl)-L-cysteine (TFEC), which are the cysteine S-conjugates of the halogenated alkenes trichloroethylene and tetrafluoroethylene, respectively (24,25). Cysteine S-conjugate β-lyases are PLP-dependent enzymes that are normally involved in amino acid metabolism. However, when the halogenated cysteine S-conjugates serve as substrates the strong electron-withdrawing property of the halogenated moiety bound to the sulfur causes these enzymes to catalyze a non-physiological β-elimination reaction (15,19,24–26). The sulfur-containing fragment produced in the β-lyase reaction with the halogenated cysteine S--conjugates, such as DCVC and TFEC, is toxic because it acts as a thioacylating agent particularly of the ε-amino group of lysyl residues in proteins (17,18,24,25). Several cysteine S-conjugate β-lyases are present in the mitochondria, including mitochondrial aspartate aminotransferase (mitAspAT), mitochondrial branched-chain aminotransferase, and alanine-glyoxylate aminotransferase isozyme II (see the Discussion). Others are largely cytosolic, including kynureninase, glutamine transaminase K (GTK) and cytosolic branched-chain aminotransferase (25).

In a similar fashion to the bioactivation pathway for halogenated alkenes, the initial step in the proposed bioactivation of cisplatin involves the formation of a cisplatin-glutathione S-conjugate (13). The sulfur moiety of glutathione replaces one of the chloride ions of cisplatin (11,12). The glutathione S-conjugate is cleaved to a cisplatin-cysteinylglycine S-conjugate by GGT, which is highly expressed on the surface of proximal tubule cells (27). The cysteinyl-glycine S-conjugate is further metabolized to a cisplatin-cysteine S-conjugate by aminopeptidases, which are also present on the surface of proximal tubule cells (28). Both the GGT- and the aminopeptidase-catalyzed reactions take place extracellularly.

We hypothesize that the cisplatin-cysteine S-conjugate is transported into the cells, where, owing to the strong electron-withdrawing property of the Pt-S moiety, it is converted by cysteine S-conjugate β-lyase(s) to pyruvate, ammonium and a reactive Pt-thiol compound ((NH2)2Pt(Cl)SH) (Eq1). We further hypothesize that this highly reactive Pt-thiol compound rapidly binds to the sulfhydryl moieties of proteins in proximity, thereby suggesting the cellular location of the PLP-dependent cysteine Sconjugate β-lyase that metabolizes the cysteine S-conjugate of cisplatin.

| (1) |

To test our hypothesis, mice were treated with cisplatin with or without AOAA, a PLP-enzyme inhibitor that blocks cysteine S-conjugate β-lyase activity and which was previously shown to protect renal proximal tubule cells against cisplatin toxicity both in vivo and in vitro (10,11). We asked whether AOAA reduced the level of Pt bound to proteins in the mitochondria, and/or cytosol of the kidney. After finding that AOAA reduced the level of Pt bound to mitochondrial protein, we investigated whether mitAspAT (an enzyme previously shown to possess cysteine S-conjugate β-lyase activity (29)) could catalyze the bioactivation of cisplatin. mitAspAT was transfected into LLC-PK1 cells and its effect on cisplatin toxicity was evaluated in both dividing and confluent cells. Finally, we assayed specific cytosolic and mitochondrial enzymes of energy/amino acid metabolism to determine which, if any, are disrupted in LLC-PK1 cells exposed to cisplatin. The results of these studies are reported here.

EXPERIMENTAL PROCEDURES

Reagents and Enzymes

Pig heart malate dehydrogenase (MDH) (910 U/mg; 5.6 mg/ml), cisplatin, G418, ammediol [2-amino-2-methyl-1,3-propanediol], AOAA, Trizma Base (Tris), HEPES, EDTA, EGTA, 2,4-dinitrophenylhydrazine, NADH, NADPH, NAD+, ADP, L-phenylalanine, trypsin, dithiothreitol, sodium thiomalate, ferrous ammonium sulfate, 3-[4,5-dimethylthiazol-2-yl]-2,5-diphenyltetrazolium bromide (MTT; Thiazolyl Blue Tetrazolium Bromide), bovine serum albumin, cytochrome c (horse heart type VI), leupeptin, the monosodium salts of L-aspartate and L-glutamate, and the sodium salts of pyruvate, α-keto-γ-methiolbutyrate and α-ketoglutarate were obtained from Sigma Chemical Company (St. Louis, MO). Hank’s balanced salt solution (HBSS) was from GIBCO/BRL. Rabbit anti-rat liver mitAspAT whole serum was a generous gift from Dr. Ana Iriarte, University of Missouri-Kansas City, Kansas City, MO. TFEC synthesized by the method of Hayden and Stevens (30) was a generous gift from Dr. Sam Bruschi, University of Washington, Seattle, USA. DCVC was synthesized by the method of McKinney et al. (31).

Animals

Male C57BL/6 mice (6–8 weeks old) were purchased from Harlan (Indianapolis, IN). Animals were housed in cages in the Animal Resource Facilities at the University of Oklahoma Health Sciences Center. Food and water were provided ad libitum. All treatment protocols were approved by the OUHSC IACUC Committee.

Treatment of Mice with Cisplatin and AOAA

Mice were treated with cisplatin and AOAA according to the same treatment protocol used in previous studies in which AOAA protected against cisplatin-induced renal toxicity (10). AOAA has been shown to inhibit kidney cysteine-conjugate beta-lyase activity in vivo (32). The AOAA treatment protocol used in the present study has been used in mice by other investigators to block the nephrotoxicity of hexachloro-1,3-butadiene, a halogenated alkene that is metabolized to a nephrotoxicant by cysteine-S-conjugate beta-lyase (33). Cisplatin was prepared as a 1 mg/ml (3.3 mM) stock solution in 0.9% (w/v) NaCl, sterilized by filtration through a 0.22 µm filter. Within 30 min of treatment, AOAA was dissolved in saline at a concentration of 10 mg/ml (110 mM), and sterilized by filtration through a 0.22 µm filter. The mice were divided into two treatment groups. Animals in group 1, the cisplatin treatment group, were each administered three doses of saline (10 µl/g body weight.) via oral gavage, 1 h before, 10 min before, and 5 h after 15 mg of cisplatin/kg body weight was injected i.p. Animals in group 2, the AOAA-cisplatin treatment group, were each administered three doses of AOAA (100 mg AOAA/kg body weight) via oral gavage 1 h before, 10 min before, and 5 h after 15 mg of cisplatin/kg body weight was injected i.p. Twenty-four h after cisplatin treatment, the mice were weighed and sacrificed by CO2 asphyxiation. The kidneys were removed, weighed, and used immediately for isolation of subcellular fractions.

Isolation of Subcellular Fractions from Mouse Kidney

Fractionation of mouse kidneys was carried out according to published methods (34,35). Briefly, the tissue was homogenized in ice-cold isolation medium (0.3 M sucrose, 25 mM Tris-HCl, pH 7.3) with a Dounce homogenizer. The homogenate was centrifuged at 500 g for 15 min. The supernatant was collected and centrifuged at 9,000 g for 15 min. The 9000 g pellet was rinsed by resuspending it in isolation medium followed by centrifugation at 10,000 g for 15 min. The washed pellet was resuspended in isolation medium and designated M1. The 9,000 g supernatant was centrifuged at 100,000 g for 1 h. The 100,000 g supernatant was the cytosolic fraction. The 100,000 g pellet was re-suspended in isolation medium and designated M2. The fractions were stored at −80°C.

Assays of Marker Enzymes in Subcellular Fractions Prepared from Mouse Kidney

Lactate dehydrogenase (LDH), glutamate dehydrogenase (GDH) and NADPH-linked cytochrome c reductase served as markers for cytosol, mitochondria and microsomes, respectively. LDH and GDH were assayed by continuously monitoring the disappearance of NADH at 340 nm (NADH ε340nm 6,230 M−1cm−1) (36). NADPH-linked cytochrome c reductase was assayed by a modification of the method of Srinivas et al. (37). The reaction mixture (0.2 ml) contained 100 mM Tris-HCl buffer pH 8.0, 6 µl of cytochrome c (20 mg/ml in distilled water), 0.1 mM NADPH and enzyme. In preliminary experiments in which NADPH was omitted there was no change in residual absorbance at 340 nm. Therefore, the blank used routinely to measure the activity of NADPH-linked cytochrome c reductase lacked cytochrome c. The disappearance of NADPH was continuously recorded at 340 nm (NADPH ε340nm 6,230 M−1cm−1). All three assays were carried out at 37°C in a SpectraMax 96-well plate spectrophotometer (Molecular Devices, Sunnyvale, CA).

Quantitation of Protein-bound Pt in Mouse Kidney Fractions

Proteins in the M1, M2, and cytosolic kidney fractions were precipitated with 10% (w/v) trichloroacetic acid for 15 min at 4°C, and pelleted by centrifugation at 13,000 g for 3 min. The pellets were washed once with ice-cold acetone and digested overnight at room temperature in 7.5 M nitric acid. The digested samples were diluted with water to 3.25 M nitric acid and the amount of Pt bound to proteins was quantified by graphite furnace atomic absorption spectrometry (GFAAS) with a Varian SpectrAA-220Z Graphite Furnace Double Beam Atomic Absorption Spectrophotometer with Zeeman background correction. The lamp current was 10 mA, the wavelength was 265.9 nm, and the slit width was 0.5 nm. Pt standards in 10% HCl (SPEX CertiPrep, Metuchen, NJ) were diluted with 3.25 M nitric acid. Each sample was measured in triplicate and calibrated relative to Pt standards that were measured with each set of samples. Hot injection was performed at 85°C, and the injection volume was 15 µl. The furnace program consisted of four phases: drying (85°C for 5 s, 95°C for 32 s, and 120°C for 10 s), ashing (1200°C for 17 s), atomization (2700°C for 3.5 s) and cleaning (2800°C for 3 s).

Transfection of LLC-PK1 Cells with Rat Liver mitAspAT cDNA

The cDNA for the rat liver precursor of mitAspAT (pmitAspAT) was a generous gift from Dr. Ana Iriarte (University of Missouri-Kansas City, Kansas City, MO) (38,39). The precursor contains the N-terminal 29-amino acid peptide that targets the protein for translocation into mitochondria (38). The targeting sequence is removed during import to form the mature mitAspAT. The cDNA of pmitAspAT was subcloned into the mammalian expression vector pcDNA3.1 (+) (Invitrogen, Carlsbad, CA) through HindIII and BamHI sites. LLC-PK1 (ATCC CRL 1392), a pig kidney proximal tubule cell line, was obtained from the American Type Culture Collection (Manassas, VA). The cells were maintained in Dulbecco’s Modified Eagle’s Medium (DMEM, Invitrogen, Carlsbad, CA), with 5% fetal bovine serum (FBS, HyClone Laboratories, Logan, UT), 50 U/ml penicillin and 50 µg/ml streptomycin (Invitrogen) at 37°C in a 5% CO2 atmosphere. The pmitAspAT cDNA was transfected into LLC-PK1 cells with the Calcium Phosphate Eukaryotic Transfection Kit (Stratagene, La Jolla, CA) as previously described (40). More than one thousand colonies grew out in the presence of 2 mg/ml G418. Six colonies were picked and grown into individual cell lines. AspAT activity of each cell line was measured, and the cell line that exhibited the highest AspAT activity was chosen for the studies presented herein and named LLC-PK1/ mitAspAT. The LLC-PK1/mitAspAT cell line maintained the same growth rate as the untransfected LLC-PK1 cells. The pcDNA 3.1 (+) vector transfected cell line (LLC-PK1/C1) from previous studies was used as the control (40). The two cell lines were maintained in DMEM containing 5% FBS and 400 µg/ml of G418.

Western Blot Analysis

Cell lysates of LLC-PK1/mitAspAT and LLC-PK1/C1 were used for SDS-polyacrylamide gel electrophoresis, and Western blot analysis as previously described (40). Rabbit anti-rat liver mitAspAT whole serum, generously provided by Dr. Ana Iriarte, was used as the primary antibody at 1:100,000 dilution (38,39,41,42).

Cisplatin Toxicity in Confluent LLC-PK1/mitAspAT Cells and LLC-PK1/C1 Cells

The toxicity of cisplatin toward LLC-PK1 cells was determined as described previously (40). Briefly, LLC-PK1/mitAspAT and LLC-PK1/C1 cells were seeded in 96-well plates at 104 cells/well in DMEM containing 5% FBS and 400 µg/ml G418. The cells became confluent on day 3 and the medium was replaced with fresh medium. On day 7, the medium was removed and replaced with cisplatin diluted in DMEM. As in our previous studies, serum and antibiotics were not included in the medium during the treatment (40). The cisplatin stock solution was diluted in DMEM within 30 min of addition to the cells. The cells were incubated in the cisplatin-containing medium for 3 h at 37°C in 5% CO2. Cells incubated in DMEM alone served as controls. After 3 h, the medium was removed and replaced with DMEM containing 5% FBS and 400 µg/ml G418. The cells were incubated at 37°C in 5% CO2 for an additional 69 h. The number of viable cells was determined by the MTT assay which utilizes dehydrogenase activity in intact cells to assess the number of living cells (43). For all experiments the cells were observed immediately before starting the MTT assay to ensure that MTT data correlated with our observation of cell toxicity.

Treatment of Confluent LLC-PK1/mitAspAT Cells and LLC-PK1/C1 Cells with AOAA and Cisplatin

Treatment of the cells with AOAA was carried out by a modification of a previously published method (11). After 7 days in culture, a stock of 10 mM AOAA in DMEM was added at various concentrations to the cell medium. The cells were then incubated at 37°C in 5% CO2 for 30 min. The medium was removed and replaced with DMEM containing no cisplatin or 120 µM cisplatin and the concentration of AOAA used in the preincubation. The cells were incubated at 37°C for an additional 3 h. At the end of the 3 h incubation, the medium was replaced with DMEM containing 5% FBS and 400 µg/ml G418. The cells were incubated at 37°C in 5% CO2 for an additional 69 h. The number of viable cells was determined by the MTT assay (43).

Cisplatin Toxicity toward Dividing Cells

LLC-PK1/mitAspAT and LLC-PK1/C1 cells were seeded in 96-well plates at 5 × 103 cells/well in DMEM containing 5% FBS and 400 µg/ml G418. The next day, the medium was removed and replaced with cisplatin diluted in DMEM. The stock solution of cisplatin was diluted in the DMEM within 30 min of addition to the cells. The cells were incubated in the cisplatin-containing medium for 3 h at 37°C in 5% CO2. Cells incubated in DMEM alone served as controls. At the end of the incubation, the medium was removed and replaced with DMEM containing 5% FBS and 400 µg/ml G418. The cells were then incubated at 37°C in 5% CO2 for an additional 69 h. The number of viable cells was determined by the MTT assay (43).

Preparation of LLC-PK1 Cell Lysates for Enzyme Measurements

LLC-PK1/C1 and LLC-PK1/mitAspAT cells were seeded in P100 tissue culture plates at a density of 106 cells/plate. On day 4, the cells reached confluence and the medium was changed. On day 7, the medium was removed, replaced with 10 ml of incubation buffer (HBSS/5 mM HEPES, pH 7.2) containing 50 µM cisplatin, 100 µM cisplatin or no cisplatin (control) and incubated for 3 h at 37°C in an air incubator. At the end of the 3-h incubation period, all HBSS solutions were replaced with DMEM containing 5% FBS and 400 mg/ml of G418. The cells were then incubated at 37°C in 5% CO2 for 24 h. After the 24-h incubation period, the cells were detached from the plates by trypsinization and re-suspended in 600 µl of lysis buffer (50 mM Tris-HCl, 5 mM sodium citrate, 0.6 mM magnesium chloride, 1 mM dithiothreitol, 0.2 mM EGTA, 0.08% (v/v) Triton X-100 and 50 µM leupeptin; pH 7.4 (44)). For measurement of aconitase activity, the enzyme was activated by incubating the lysate for 30 min at 37°C in a mixture containing 20 mM sodium thiomalate and 4 mM ferrous ammonium sulfate (44). Freezing the lysate resulted in variable recoveries of KGDHC, aconitase, glutamine transaminase K (GTK), and glyceraldehyde 3-phosphate dehydrogenase (GAPDH) activities. Therefore, the activities of these enzymes (and TFEC β-lyase activity) were determined immediately after suspension of the cells in the lysis buffer. AspAT, GDH, LDH and MDH activities are stable to freeze-thawing and were assayed in lysates that had previously been stored at −80°C.

Enzyme Measurements in LLC-PK1 Cell Lysates

Total AspAT activity [cytosolic (cytAspAT) activity plus mitochondrial AspAT (mitAspAT) activity] was assayed as described by Cooper et al. (29). The reaction mixture (final volume 0.2 ml) contained 100 mM HEPES (pH 7.0), 10 mM L-aspartate, 6 mM α-ketoglutarate, 0.1 mM NADH, 0.6 µg of MDH. The reaction was initiated by addition of a solution containing AspAT (1–10 µl). The disappearance of absorbance of NADH at 340 nm was continuously monitored. Blanks lacked aspartate. To distinguish between cytosolic and mitochondrial isozymes mitAspAT was inactivated by heating for 10 min at 70°C in the presence of 4 mM α-ketoglutarate (45). Under these conditions, cytAspAT is stable. In cells overexpressing mitAspAT, the cell lysate was diluted 25-fold in distilled water before assay of AspAT activity.

GTK activity was measured by the procedure of Cooper (46) modified for 96-well plate analysis. The assay procedure makes use of GTK as a freely reversible glutamine (methionine) aromatic aminotransferase (46,47). The reaction mixture (50 µl) contained 5mM α-keto-γ-methiolbutyrate, 10mM L-phenylalanine, 100mM ammediol buffer (pH 9.0) and enzyme. After incubation at 37°C the reaction was terminated by the addition of 150 µl of 1 M NaOH. The absorbance was read within 2 min at 320 nm (ε phenylpyruvate enol 16,000 M−1cm−1). The blank contained the complete reaction mixture to which enzyme was added immediately prior to addition of NaOH. The reaction is linear for at least 2 hours provided no more than 25 nmol of α-keto-γ-methiolbutyrate is transaminated.

Cysteine S-conjugate β-lyase activity with TFEC as the β-lyase substrate was measured by the procedure of Cooper and Pinto (48). α-Ketoglutarate and α-keto-γ-methiolbutyrate were included in the reaction mixture to prevent accumulation of pyridoxamine 5'-phosphate (PMP) form of the enzyme which cannot support a β-lyase reaction (48). Cysteine S-conjugate β-lyase activity with DCVC as the β-lyase substrate was determined in the presence of PLP as previously described (40).

GDH and LDH were measured in the isolated cells as described above for analysis of these enzymes in subcellular fractions. GAPDH was assayed by the method of Cooper et al. (49) except that the volume of the assay mixtures was reduced from 1.0 ml to 0.2 ml. The activity of MDH was assayed according to the method of Park et al. (36). The disappearance of NADH (for measurement of MDH activity) or the appearance of NADH (for the measurement of GAPDH activity) was continuously recorded at 340 nm. Aconitase and KGDHC activities were determined by continuous fluorometric procedures coupled to NAD+/NADP+ reduction (44).

All enzyme assays, except those of KGDHC and aconitase, were carried out at 37°C in a SpectraMax 96-well plate spectrophotometer (Molecular Devices, Sunnyvale, CA). Aconitase and KGDHC assays were carried out at 30°C in a SpectraMax 96-well plate fluorometer (Molecular Devices, Sunnyvale, CA). Each enzyme was assayed in triplicate for each cell harvest (44).

Protein and Specific Activity Measurements

Protein concentrations were determined using a micro-Biuret assay kit from Sigma (St. Louis, MO, USA) or by the BCA protein assay (Pierce, Rockford, IL). In both cases, bovine serum albumin was used as a standard. For all enzyme activities reported here, one unit of enzyme activity is defined as the amount that catalyzes the formation of one µmole of product per min. Enzyme specific activity is defined as milliunits (mU) per mg of protein.

Data Analyses

Significant differences in the levels of protein-bound Pt between AOAA-treated mice and controls were detected with two-tailed t-tests (Prism, GraphPad Software, Inc., San Diego, CA). In each cell culture toxicity experiment all determinations were done in triplicate. Each experiment was repeated at least three times. The mean and standard deviation (SD) were computed for each treatment. LD50 and its 95% confidence intervals were calculated with Prism sigmoidal dose-response (variable slope) curve fit. The two-tailed t-test was used to detect significant difference in cisplatin toxicity among the cell lines and to detect changes in enzyme activities in LLC-PK1 cells overexpressing mitAspAT. The effects of cisplatin treatment on specific activities of selected enzymes in the cell lysates were analyzed by a one-way ANOVA test using SPSS 11.5 software for Windows. Differences were considered significant if p ≤ 0.05.

RESULTS

Effect of AOAA on Levels of Protein-Bound Pt in Kidney Subcellular Fractions

Mice were treated with cisplatin and the distribution of protein-bound Pt in subcellular fractions of the kidney was analyzed. To identify the subcellular location of the cysteine S-conjugate β-lyases that activate cisplatin to a reactive thiol, half of the mice were treated with cisplatin, the other half were treated with cisplatin plus AOAA. Treatment with AOAA blocks the action of cysteine S-conjugate β-lyases and reduces the binding of Pt in the subcellular fractions that contain these enzymes. The kidneys from the cisplatin-treated mice were homogenized and fractionated into three subcellular fractions. The purity of these subcellular fractions was determined by assaying each fraction for LDH, GDH and NADPH-linked cytochrome c reductase, which are predominantly localized in the cytosol, mitochondria and microsomes, respectively. These markers are of high specific activity and not subject to inactivation by AOAA or by freeze-thawing (data not shown). Table 1 shows that the cytosolic fractions were highly enriched with the cytosolic marker LDH and contained low levels of GDH (mitochondrial marker enzyme) or cytochrome c reductase (microsomal marker enzyme). The low specific activity of GDH in the cytosolic fraction indicates that minimal rupture of mitochondria occurred during isolation. The M1 fraction was enriched with mitochondria as evidenced by the high specific activity of GDH and low relative specific activities of LDH and cytochrome c reductase. The M2 fraction was enriched with microsomes as shown by the high specific activity of NADPH-linked cytochrome c reductase in the M2 fraction compared to the M1 and cytosolic fractions. The M2 fractions also contained mitochondria, more in the AOAA-treated mice than the saline-treated controls, as evidenced by the relatively high specific activity of GDH in that fraction.

Table 1.

Specific Activities of Marker Enzymes in Subcellular Fractions Isolated from Kidneys of Mice Treated with Cisplatin and Saline or with Cisplatin and Aminooxyacetic Acid (AOAA)a

| Fraction | |||

|---|---|---|---|

| Cytosol | M1 | M2 | |

| Cisplatin + Saline | |||

| lactate dehydrogenase (LDH) | 195±25 (87%)b | 13.6±1.7 (6%) | 15.1±2.1 (7%) |

| glutamate dehydrogenase (GDH) | 0.70±0.0.03 (1%) | 47.4±1.2 (58%) | 33.2±3.9 (41%) |

| cytochrome c reductase | 1.86±0.10 (10%) | 2.14±0.66 (11%) | 14.8±0.9 (79%) |

| Cisplatin + AOAA | |||

| lactate dehydrogenase | 224±20 (85%) | 16.4±2.1 (6%) | 23.6±0.8 (9%) |

| glutamate dehydrogenase | 1.44±0.21 (2%) | 33.7±5.5 (38%) | 53.0±6.5 (60%) |

| cytochrome c reductase | 2.86±0.14 (10%) | 4.25±0.32 (14%) | 22.2±2.2 (76%) |

All enzyme specific activities are expressed as mU/mg of protein. n = 8 for all determinations. Data are reported as the mean ± SEM.

The percentage of the enzyme activity that partitioned into each subcellular fraction is in parentheses

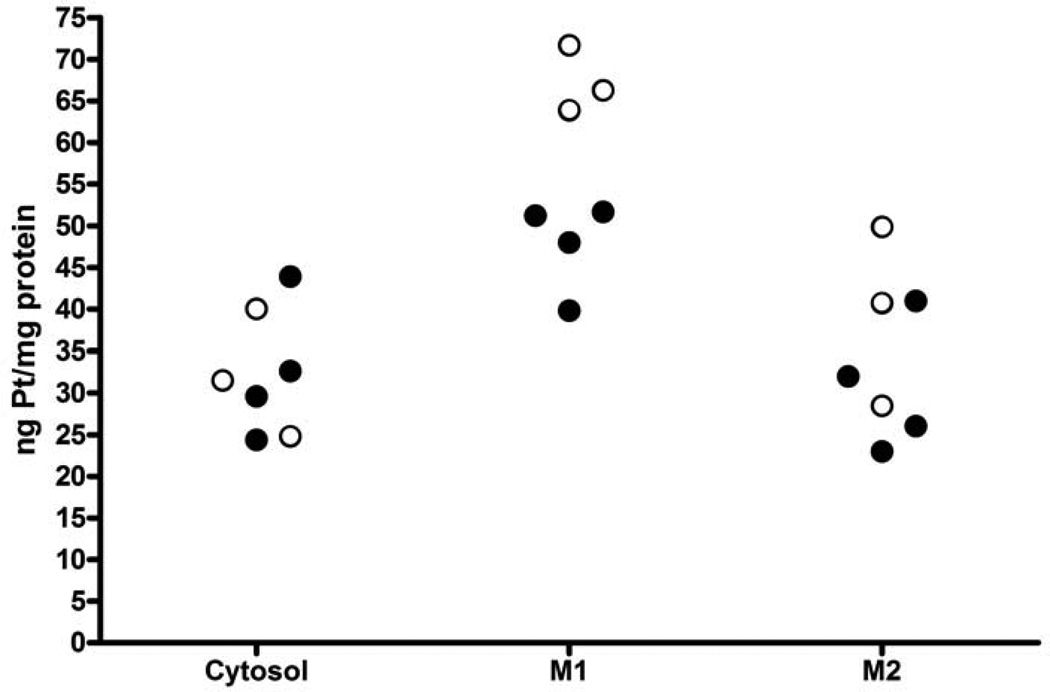

The amount of Pt bound to protein in each of the fractions is shown in Figure 1. In mice treated with cisplatin alone, the concentration of Pt bound to protein was significantly higher in the mitochondrial fraction (M1) than in the cytosolic fraction (67.3 ng Pt/mg protein ± 4.0 (S.D.) vs 32.1 ng Pt/mg protein ± 7.6, n = 3,p = 0.0058). The level of Pt bound to protein in the mitochondrial fraction was also higher than that in the M2 fraction although the difference was not statistically significant, which may be due to the contamination of the microsomal fraction with mitochondria (67.3 ± 4.0 vs 39.7 ± 10.7, p = 0.053). In mice pretreated with AOAA, there was no significant change in the concentration of Pt bound to protein in the cytosolic fraction (32.1 ± 7.6 vs 32.6 ± 8.3, n = 4, p = 0.93). However, inhibition of the cysteine-conjugate β-lyase reaction with AOAA did significantly decrease Pt binding to protein in the mitochondrial fraction (67.3 ± 4.0 vs 47.7 ± 5.5, p = 0.0055). There was a small, but not significant, reduction in the concentration of Pt bound to protein in the M2 fraction in mice treated with AOAA (39.7 ± 10.7 vs 30.5 ± 7.9, p = 0.30). This reduction may be due to the mitochondrial proteins present in the M2 fraction.

Figure 1.

Effect of AOAA on Pt binding to protein in kidneys from mice treated with cisplatin. Mice were pretreated with saline (open circles) or AOAA (filled circles) followed by an injection of 15 mg/kg cisplatin. Twenty-four h after cisplatin treatment, kidney fractions were isolated and the protein in each fraction precipitated with acid. The amount of Pt bound to protein was measured with FAAS. There was significantly more Pt bound to protein in the mitochondrial fraction (M1) than in the cytosol. AOAA had no effect on the amount of Pt bound to proteins in the cytosol (cyto), but significantly reduced the binding to proteins in the M1 fraction. Treatment with AOAA did not significantly reduce the amount of Pt bound to protein in the M2 fraction.

In summary, the data show that in the kidney of cisplatin-treated mice, the highest concentration of Pt bound to protein was in the mitochondrial fraction. Inhibition of the nephrotoxicity of cisplatin with AOAA was associated with a significantly decreased concentration of Pt bound to protein in the mitochondria but not in the cytosol or M2 fraction. These data suggest that the cysteine S-conjugate β-lyase that metabolizes the cisplatin-cysteine S-conjugate to a nephrotoxicant is located in the mitochondria.

Expression of mitAspAT in LLC-PK1/mitAspAT Cells

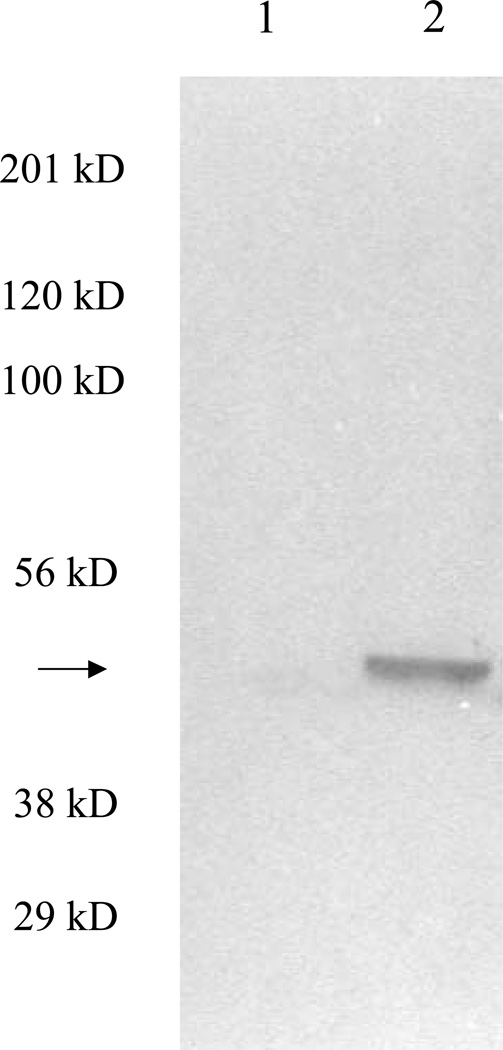

LLC-PK1 cells were transfected with the cDNA for rat liver mitAspAT, a mitochondrial enzyme with cysteine S-conjugate β-lyase activity (29). Individual colonies were grown in the presence of G418. A subline that overexpressed mitAspAT was named LLC-PK1/mitAspAT and used for all subsequent studies. A subline of LLC-PK1 cells stably transfected with empty transfection vector served as a control, and was named LLC-PK1/C1. Rat liver mitAspAT is a homodimer with a subunit molecular mass of 45 kDa (38,39). Expression of the rat liver mitAspAT was detected by Western blot in the LLC-PK1/mitAspAT cells (Fig. 2, lane 2). The band detected by the anti-rat liver mitAspAT antibody was 45 kDa, which demonstrated that the rat liver mitAspAT was correctly processed to mature protein in the LLC-PK1 cells. The anti-rat liver mitAspAT antibody did not bind to any proteins in the LLC-PK1/C1 cell line, which indicated that the antibody did not recognize porcine kidney AspAT (Fig. 2, lane 1).

Figure 2.

Western blot of LLC-PK1/mitAspAT and LLC-PK1/C1 cell lysates. LLC-PK1/C1 (Lane 1) or LLC-PK1/mitAspAT (Lane 2) cell lysate were loaded in each lane (15 µg protein per lane). Rabbit anti-rat liver mitAspAT whole serum was used as the primary antibody. A prominent protein band with molecular mass of ~45 kDa (arrow) was detected in the LLC-PK1/mitAspAT cell line, but not in the LLC-PK1/C1 cell line. The molecular mass of this band is consistent with that of mitAspAT monomer. The positions of molecular mass markers are indicated.

Quantitation of total AspAT activity (i.e. mitAspAT plus cytAspAT) shows a 21-fold increase in specific activity in the LLC-PK1/mitAspAT cells compared with the control cell line (Table 2, p <0.001). As shown in Table 2, ~50% of the total AspAT activity in the control cells is due to mitAspAT. Therefore, the increase in mitAspAT specific activity in LLC-PK1/mitAspAT cells relative to control cells is more than 40-fold.

Table 2.

Specific Activities of AspAT and Cysteine S-Conjugate β-Lyase(s) (DCVC as Substrate) in LLC-PK1 Cells Transfected with mitAspATa

| Cell Lines | ||

|---|---|---|

| LLC-PK1/C1 (control) | LLC-PK1/mitAspAT | |

| Enzymes | ||

| total AspATb | 341 ± 20 (8) | 7,240 ± 509 (8)c |

| cytosolic AspAT | 170 ± 14 (5) | 212 ± 28 (5) |

| cysteine S-conjugate β -lyase | < 0.2d (6) | 25.0 ± 0.7e (6) |

All enzyme specific activities are expressed as mU/mg of protein. Values in parenthesis represent the number of separate cell cultures analyzed. Data are reported as the mean ± SEM.

Total AspAT is the sum of mitAspAT plus cytAspAT.

Significantly different from the control value with p <0.04.

Below the limit of detection.

Significantly different from the control value with p < 0.001.

The increase in specific activity of mitAspAT in the LLC-PK1/mitAspAT cells was accompanied by a large increase in cysteine S-conjugate β-lyase specific activity when either DCVC or TFEC was used as a β-lyase substrate (Tables 2, 3). This result is consistent with our previous findings that rat liver mitAspAT catalyzes a β-lyase reaction with TFEC or DCVC as a substrate (29). In the control cells, cysteine S-conjugate β-lyase activity toward DCVC was too low to be detected (Table 2). However, a low level of endogenous activity could be detected with TFEC as a substrate (Table 3). Overexpression of mitAspAT resulted in a 12-fold increase in the β-lyase specific activity with TFEC as a substrate.

Table 3.

Specific Activities (mU/mg) of GTK and Cysteine S-Conjugate β-Lyase(s) (TFEC as Substrate) in LLC-PK1 Cells Transfected with mitAspAT and Treated with Cisplatin

| Specific Activitiesa | |||

|---|---|---|---|

| Treatment | LLC-PK1/C1 (control) | LLC-PK1/mitAspAT | |

| Cysteine S-conjugate β -lyase | No addition | 1.25±0.21 (4) | 16.0± 1.6 (4)b |

| + 50 µM cisplatin | 1.75±0.0.09 (3) | 14.4 ±0.5 (3)c | |

| + 100 µM cisplatin | 0.96, 2.0 (2) | 19.2, 20.6 (2)b | |

| GTK | No addition | 0.73±0.11 (4) | 1.08±0.16 (5) |

| + 50 µM cisplatin | 0.90±0.14 (3) | 0.91±0.13 (3) | |

| + 100 µM Cisplatin | 0.69±0.19 (4) | 0.82±0.13 (5) | |

Specific activity in cells 24 h after 3-h treatment with 100 µM cisplatin. Data are reported as the mean ± SEM. The numbers of separate cell lysates analyzed for a particular enzyme activity are shown in parenthesis.

Significantly different from the LLC-PK1/C1 cells with p < 0.01.

Significantly different from the LLC-PK1/C1 cells with p < 0.05.

Purified rat kidney GTK exhibits strong β-lyase activity toward TFEC in vitro (see the Discussion). The specific activity of GTK in the control LLC-PK1 cells, however, is low and was not increased in the cells overexpressing mitAspAT (Table 3). This finding rules out the possibility that a) mitAspAT overexpression leads to the concomitant overexpression of GTK, and that b) part of the increase in cysteine S-conjugate β-lyase activity in the cells overexpressing mitAspAT is due to increased GTK. As noted for TFEC β-lyase activity, cisplatin treatment did not affect GTK activity.

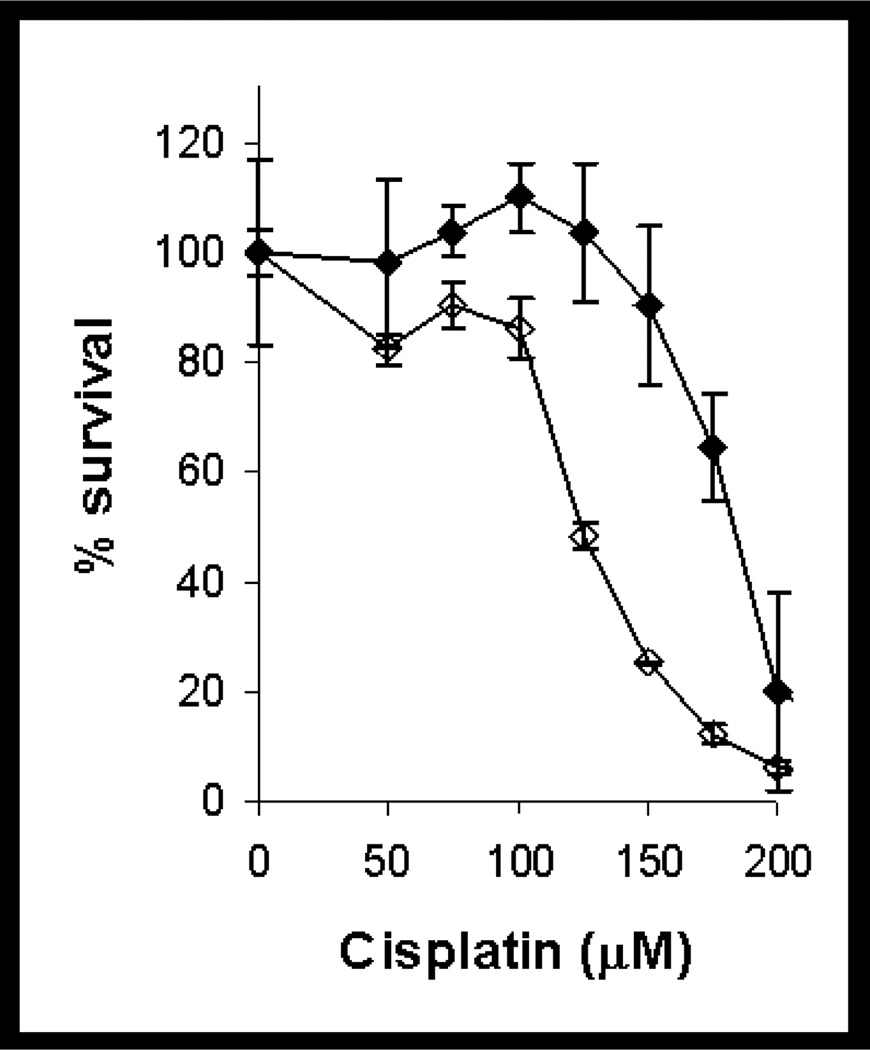

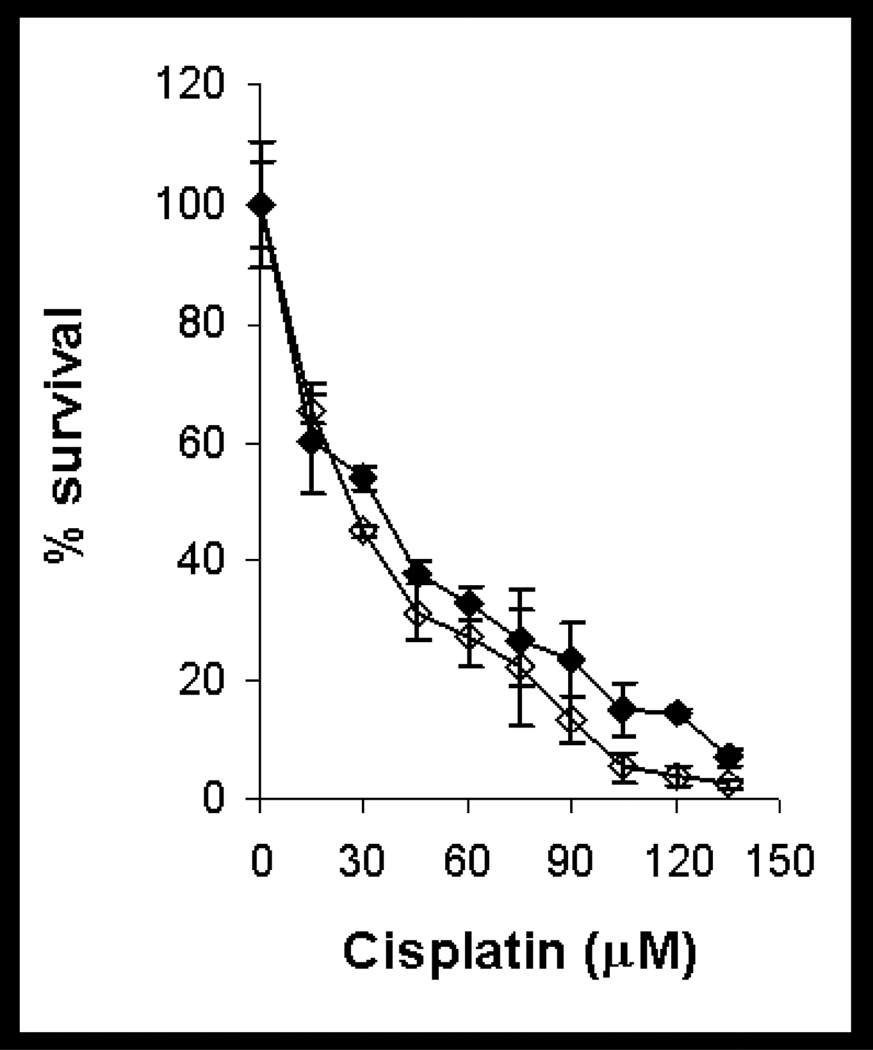

Toxicity of Cisplatin in Confluent mitAspAT-transfected Cells

Confluent monolayers of LLC-PK1/mitAspAT and LLC-PK1/C1 cells were treated with cisplatin. The cells transfected with mitAspAT were more sensitive to cisplatin-induced toxicity than the vector-transfected controls (Figure 3). The LD50 of cisplatin in LLC-PK1/mitAspAT cells was 126 µM with 95% confidence intervals ranging from 116 to 136 µM. The LD50 of cisplatin in LLC-PK1/C1 cells was 182 µM with 95% confidence intervals ranging from 177 to 187 µM. There was a significant difference between the LD50 of LLC-PK1/mitAspAT and LLC-PK1/C1 cells toward cisplatin (p <0.0001), and the slopes of the two dose curves were also significantly different (p = 0.0033). These data demonstrate that overexpression of mitAspAT increases cisplatin induced-toxicity in confluent monolayers of LLC-PK1 cells.

Figure 3.

Toxicity of cisplatin in confluent LLC-PK1/mitAspAT and LLC-PK1/C1 cells. Confluent monolayers of LLC-PK1/mitAspAT cells (open diamonds) or LLC-PK1/C1 cells (filled diamonds) were treated with cisplatin in DMEM for 3 h. The cisplatin was removed at the end of the 3-h exposure and replaced with fresh DMEM, containing 5% FBS and 400 µg/ml G418. The viability of the cells was measured at 72 h. A representative experiment is shown. Each point represents the mean of triplicate samples ± S.D.

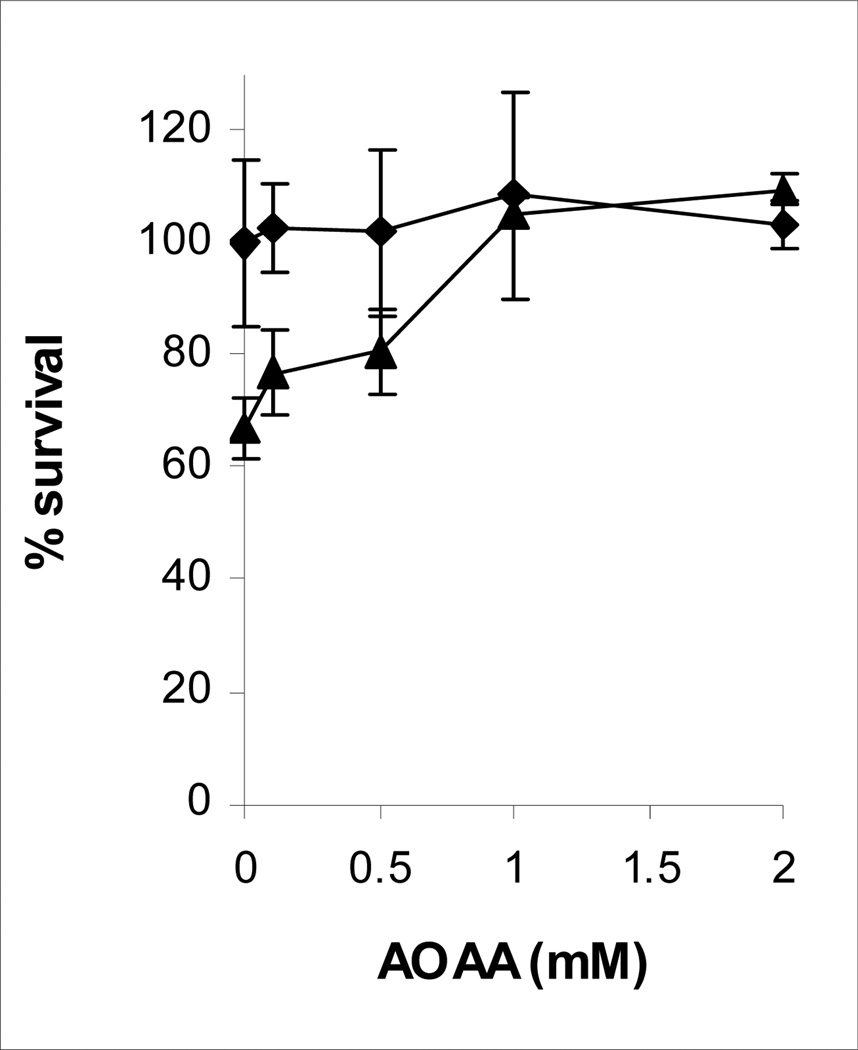

Protection by AOAA against Cisplatin-induced Toxicity in LLC-PK1/mitAspAT Cells

The effect of AOAA on cisplatin toxicity was assessed in confluent monolayers of LLC-PK1/mitAspAT cells (Figure 4). In the absence of AOAA, 120 µM cisplatin killed 33% of the LLC-PK1/mitAspAT cells (p <0.05). AOAA protected confluent LLC-PK1/mitAspAT cells against cisplatin-induced toxicity (p <0.0001). The protective effect was significant with 1 or 2 mM AOAA (p <0.0005). Addition of 0.1 – 2 mM AOAA to LLC-PK1/mitAspAT cells had no effect on cell viability in the absence of cisplatin (p = 0.9). AOAA completely blocked the toxicity of 120 µM cisplatin in mitAspAT-transfected cells (Figure 4).

Figure 4.

Effect of AOAA on cisplatin toxicity in confluent LLC-PK1/mitAspAT cells. Confluent monolayers of LLC-PK1/mitAspAT were preincubated with AOAA for 30 min. The cells were then treated for 3 h with DMEM containing no cisplatin (filled diamonds) or 120 µM cisplatin (filled triangles) and the concentration of AOAA used in the preincubation. The cisplatin and AOAA were removed at the end of the 3-h exposure and replaced with fresh DMEM, containing 5% FBS and 400 µg/ml G418. The viability of the cells was measured at 72 h. The experiment was done three times. A representative experiment is shown. Each point represents the mean of triplicate samples ± S.D.

Toxicity of Cisplatin toward Dividing LLC-PK1 Cells Transfected with mitAspAT

The effect of cisplatin on survival of dividing LLC-PK1/C1 and LLC-PK1/mitAspAT cells is shown in Figure 5. The LD50 of cisplatin in dividing LLC-PK1/C1 cells was 25.7 µM with 95% confidence intervals ranging from 21.2 to 31.1 µM. The LD50 of cisplatin in dividing LLC-PK1/mitAspAT cells was 28.2 µM with 95% confidence intervals ranging from 22.4 to 35.4 µM. There was no significant difference between the LD50 of the dividing LLC-PK1/C1 and LLC-PK1/mitAspAT cells (p = 0.48). The slopes of the two dose-response curves were not significantly different (p = 0.10). Dividing cells are more sensitive than non-dividing cells to the toxicity of DNA-damaging agents such as cisplatin. Both the LLC-PK1/C1 and LLC-PK1/mitAspAT cells were more sensitive to cisplatin toxicity in log growth (Figure 5) than as confluent monolayers (Figure 3). The DNA-damage-induced apoptosis in theses cell lines is independent of cysteine S-conjugate β-lyase activity.

Figure 5.

Toxicity of cisplatin in dividing LLC-PK1/mitAspAT and LLC-PK1/C1 cells. Dividing cells of LLC-PK1/mitAspAT (open diamonds) or LLC-PK1/C1 (solid diamonds) were treated with cisplatin in DMEM for 3 h. The cisplatin was removed at the end of the 3-h exposure and replaced with fresh DMEM, containing 5% FBS and 400 µg/ml G418. The viability of the cells was measured at 72 h. The experiment was done three times. A representative experiment is shown. Each point represents the mean of triplicate samples ± S.D.

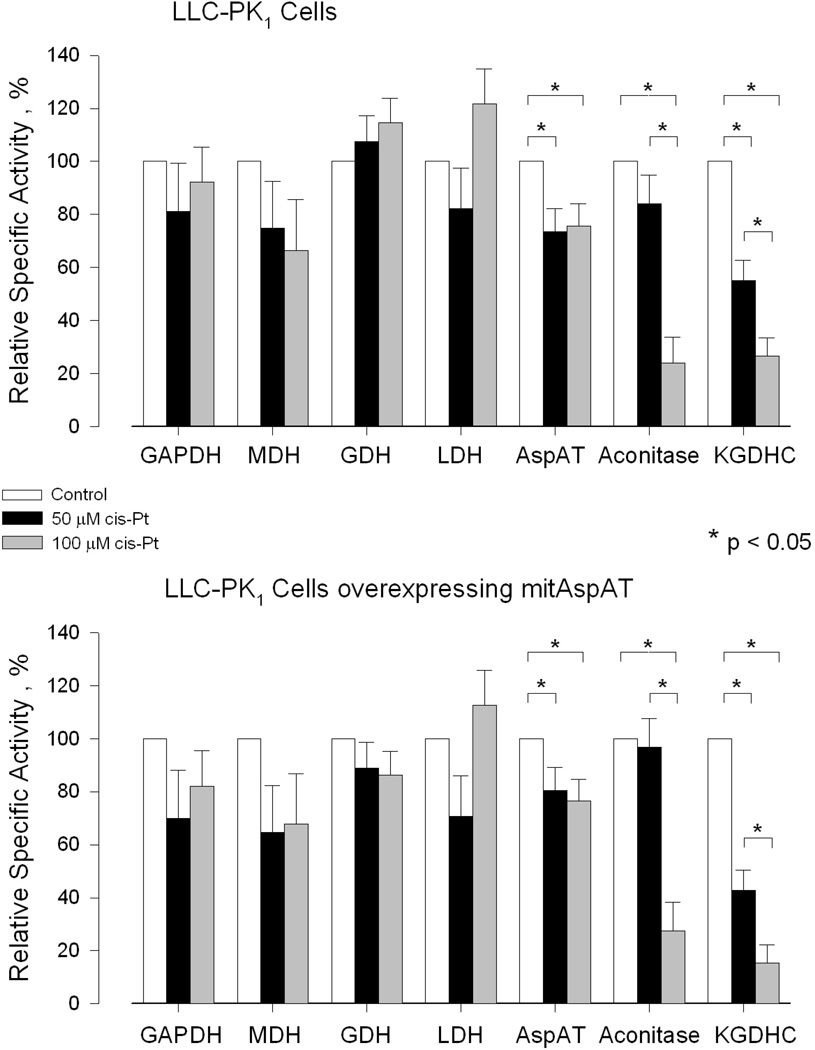

Alteration of the Specific Activities of Some Enzymes of Energy Metabolism when mitAspAT is Overexpressed in LLC-PK1 Cells

The specific activities of KGDHC and aconitase in the LLC-PK1 cells were not significantly affected by overexpression of mitAspAT (Table 4). However, the specific activity of GAPDH in cells overexpressing mitAspAT was significantly increased compared to control cells (12.4±1.8 vs 24.4±6.6; p <0.05). The specific activity of total MDH (mitochondrial plus cytosolic MDH) was significantly decreased in cells overexpressing mitAspAT (486±126 vs 314±44; p <0.05). The specific activity of GDH was increased, but the p value did not quite reach significance (62.1±19.5 vs 139±65; p = 0.07). Similar trends were observed for enzyme specific activities between LLC-PK1/mitAspAT and LLC-PK1/C1 cells treated with cisplatin (Table 4). Thus, overexpression of mitAspAT apparently leads to compensatory changes in the specific activities of some other enzymes of energy metabolism. These changes have to be taken into account when assessing the effects of cisplatin on the specific activities of enzymes of energy metabolism in the cells overexpressing mitAspAT.

Table 4.

Specific Activities of Several Enzymes of Energy Metabolism in LLC-PK1/C1 and LLC-PK1/mitAspAT Cells Exposed to Cisplatina

| Enzyme | Cells transfected with mitAspAT |

No addition | 50 µM cisplatin | 100 µM cisplatin |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| total AspAT | − | 341± 20 (8)b,c | 247±5 (6)d | 267±25 (6)d |

| + | 7,240±509 (8) | 6,470±386 (6) | 5,420±354 (6) | |

| KGDHC | − | 10.2±2.2 (10) | 5.18±2.52 (6) | 3.41±1.20 (9)d |

| + | 12.0±3.0 (10) | 3.03±1.1 (6)d | 1.83±0.7 (9)d | |

| aconitase | − | 5.62±1.32 (7) | 5.77±0.14 (5) | 2.11±1.14 (4)d |

| + | 6.99±2.59 (7) | 6.30±0.16 (5) | 1.82±1.12 (4)d | |

| GAPDH | − | 12.4±1.8 (7) | 12.7±2.0 (3) | 9.49±0.50 (5) |

| + | 24.4±6.6 (7)e | 18.5±3.3 (3) | 14.9±2.8 (5) | |

| GDH | − | 62.1±19.5 (7) | 70.9±28.5 (5) | 89.2±29.4 (5) |

| + | 139±65 (7) | 137±61 (5) | 164±74 (5) | |

| total MDH | − | 486±126 (5) | 346±68 (5) | 336±31 (3) |

| + | 314±44 (5)e | 191±13 (5) | 225±66 (3) | |

| LDH | − | 208±28 (4) | 197±8 (3) | 236± 70 (3) |

| + | 206±32 (4) | 186±19 (3) | 185±33 (3) |

Cells were treated with 50 µM cisplatin or 100 µM cisplatin, and the specific activities of selected enzymes were determined.

Specific activity (mU/mg of protein). The data are reported as the mean ± SEM.

The numbers of separate cell lysates analyzed for a particular enzyme activity are shown in parenthesis.

Treatment with cisplatin significantly (p< 0.05) lowers the specific activity of the enzyme when compared with cells not treated with cisplatin. Relative decreases of the specific activities are shown in Figure 6.

The specific activity of the enzyme differs significantly (p < 0.05) in cells that overexpress mitAspAT compared to control cells. The two-tailed t-test was used for the statistical analysis.

Selective Inhibition of KGDHC in LLC-PK1 Cells Treated with Cisplatin

The specific activities of selected enzymes of energy metabolism were measured in LLC-PK1 cells exposed to 50 µM- or 100 µM cisplatin for 3 h followed by 24 h incubation in the absence of cisplatin (Table 4). The specific activities varied considerably among different experiments carried out on different days accounting for the large SEM. Nevertheless, by comparing relative specific activities of enzymes prepared simultaneously from untreated cells and cisplatin-treated cells lysed on the same day and by using one-way ANOVA, the data showed that KGDHC (a mitochondrial enzyme) is especially sensitive to inactivation by cisplatin (Figure 6). The specific activity of aconitase (another mitochondrial enzyme of energy metabolism) was not significantly affected in the cells treated with 50 µM cisplatin, but was strongly inhibited in cells treated with 100 µM cisplatin (Figure 6). There was a significant decline in the specific activity of total AspAT in both the control cells and cells overexpressing mitAspAT treated with either 50- or 100 µM cisplatin. In the presence of 100 µM cisplatin the relative decline in specific activity, however, was much less for total AspAT than for KGDHC and aconitase in both the control and LLC-PK1/mitAspAT cells (Figure 6). Cisplatin had no significant effect on the specific activities of GDH (a largely mitochondrial enzyme), LDH (cytosolic enzyme), GAPDH (cytosolic enzyme) and total MDH in either the LLC-PK1/mitAspAT- or control cells (Figure 6). Interestingly, the percent relative KGDHC value in the LLC-PK1/mitAspAT cells treated with 100 µM cisplatin (15.4 ± 4.1) is significantly lower than that in the LLC-PK1/C1 cells treated with 100 µM cisplatin (26.6 ± 5.9) as determined by the two-tailed paired t-test (p = 0.008).

Figure 6.

Effect of cisplatin on the relative specific activities of several enzymes of energy metabolism in control LLC-PK1 cells expressing empty vector (LLC-PK1/C1 cells) and in LLC-PK1 cells overexpressing mitAspAT (LLC-PK1/mitAspAT cells). The cells were treated with 50 µM cisplatin or with 100 µM cisplatin for 3 h. The cisplatin-solution was removed and the cells were incubated in DMEM containing 5% FBS for an additional 24 h. At the end of the incubation the specific activities of selected enzymes in the cisplatin-treated cells were compared to those of control cells. The n and absolute values are as shown in Table 4. AspAT = mitAspAT + cytAspAT. The specific activities of the enzymes measured in the cisplatin-treated cells are reported as a percentage of the specific activity of the enzyme in the control cells for each individual cell preparation. Significance values were determined using one-way ANOVA. The data are shown as the mean ± SEM. The * symbol indicates p < 0.05. In addition, the two-tailed paired t-test indicates that the relative specific activity of KGDHC is significantly lower in the LLC-PK1/mitAspAT cells treated with 100 µM cisplatin than in the LLC-PK1/C1 treated with 100 µM cisplatin (p = 0.008).

DISCUSSION

Mechanism of Cisplatin-induced Toxicity toward Mitochondria in Confluent Renal Cells

The present finding that Pt bound to proteins is greater in renal mitochondria of mice injected with cisplatin than in the cytosolic fraction or the microsomal fraction (Figure 1) is consistent with the previous observation that cisplatin is a mitochondrial toxicant in confluent renal proximal tubule cells (50). Our finding leads to the question of how Pt is incorporated into renal mitochondrial proteins. The binding of cisplatin to proteins in the cytosol may be non-enzymatic. When cisplatin enters the cell, the low intracellular chloride concentration can lead to the dissociation of one or more of the chlorides resulting in the formation of monoaquo and diaquo complexes, cis-[Pt(NH3)2(H2O)Cl]+ and cis-[Pt(NH3)2(H2O)2]2+. Platinum forms a co-ordinate covalent bond with negatively charged molecules such as the sulfur on cysteine. Direct interaction of cisplatin with protein cysteine residues would explain the platination of proteins in the cytosolic fraction in the kidneys of mice injected with cisplatin, and the lack of effect of AOAA on protein platination in this fraction (Figure 1). It is of interest that in vivo cisplatin accumulates in both the liver and the kidney (51). However, the accumulation in the liver is transient. In the liver, the cisplatin may be bound to glutathione and excreted from the cell. In the kidney, cisplatin or its S-conjugates must traverse the cytosolic compartment before entry into the mitochondria. Our data show decreased platination of proteins in the renal mitochondria of AOAA-treated mice, but no decrease of protein platination in the renal cytosol of AOAA-treated mice. Our previous studies showed that AOAA protects mice and LLC-PK1 cells against cisplatin (10). AOAA forms an oxime with α-keto acids and with the coenzyme at the active site of many PLP-containing enzymes, inactivating them (52). The present work provides strong evidence that mitAspAT, acting at least in part as a β-lyase, contributes to the bioactivation of cisplatin to a renal toxicant.

Evidence that mitAspAT is a Major Cysteine S-Conjugate β-Lyase involved in the Bioactivation of Halogenated Cysteine S-Conjugates and Cisplatin-Cysteine S-Conjugate in Kidney Mitochondria

There has been some debate concerning which PLP-dependent enzymes are responsible for the bioactivation of halogenated cysteine S-conjugates in the kidney in vivo. Purified rat kidney GTK is very active in vitro as a β-lyase with several toxic halogenated cysteine S-conjugates (24,26,53), and some authors have given this enzyme the alternative name “cysteine S-conjugate β-lyase” as if it were the only such lyase (54). However, work from our laboratory and from other groups has shown that mammalian tissues possess at least ten other PLP-containing enzymes capable of catalyzing β-lyase reactions with toxic, halogenated cysteine S-conjugates (24,25).

Both TFEC and DCVC are mitochondrial toxicants, and renal mitochondrial proteins (but not cytosolic proteins) are thioacylated after rats are treated with pharmacological doses of TFEC (55–59). Moreover, the specific activity of cysteine S-conjugate β-lyase(s) capable of converting S-(6-guaninyl)-L-cysteine (a cysteine S-conjugate) to 6-mercaptoguanine is 45 times higher in a rat kidney mitochondrial fraction than in a rat kidney cytosolic fraction (60). These findings suggest the major involvement of mitochondrial cysteine S-conjugate β-lyase(s) in the bioactivation of nephrotoxic, halogenated (or prodrug) cysteine S-conjugates. In the rat, GTK occurs in the cytosolic and mitochondrial compartments. The same gene codes for cytosolic and mitochondrial forms of GTK (61). Alternative splicing generates a 34 amino acid mitochondrial targeting sequence in mitGTK, but not in cytGTK (61). As a result, about 10% of the total GTK activity in rat kidney homogenates is in the mitochondrial fraction (62). Thus, this enzyme may contribute under certain conditions to bioactivation of halogenated cysteine S-conjugates and cisplatin-cysteine S-conjugate in rat kidney mitochondria (see below).

In a recent study, we showed that cisplatin was significantly more toxic to LLC-PK1 cells overexpressing human cytosolic GTK than to control LLC-PK1/C1 cells (40). In that study, GTK specific activity was increased about 60-fold compared to control cells. Rooseboom et al. have shown that both TFEC and cisplatin are much more toxic to LLC-PK1 cells overexpressing rat kidney GTK than to control LLC-PK1 cells (63). Therefore, highly overexpressed GTK can contribute significantly to the bioactivation of cysteine S-conjugates in LLC-PK1 cells in culture. However, the results do not reveal the most likely cysteine S-conjugate β-lyase contributing to the in vivo mitochondrial toxicity of cisplatin in rat kidneys with normal levels of GTK. We previously showed that GTK does not contribute significantly to total cysteine S-conjugate β-lyase activity (with DCVC and TFEC) in isolated rat kidney mitochondria (64). Mitochondrial enzymes positively identified as cysteine S-conjugate β-lyases to date include a high-Mr β lyase (65), alanine-glyoxylate aminotransferase isozyme II (66), mitochondrial branched-chain aminotransferase (67) and mitAspAT (29). Inasmuch as alanine-glyoxylate aminotransferase II is restricted to kidney, and to a lesser extent liver (66), this enzyme might contribute to the heightened sensitivity of kidney (and to a lesser extent liver) mitochondria to toxic halogenated cysteine S-conjugates. Particularly important, however, are the high-Mr lyase and mitAspAT. The high-Mr lyase was shown to co-purify with HSP70 (68) and contain mitAspAT [manuscript in preparation]. HSP70 is known to be important in the transport of pmitAspAT into the mitochondria (69).

In support of the hypothesis that mitAspAT is an important mitochondrial enzyme involved in the bioactivation of halogenated cysteine S-conjugates, at least 15–20% of the cysteine S-conjugate β-lyase activity with TFEC as substrate in crude rat kidney mitochondria is due to mitAspAT (29). Moreover, the thioacylated proteins found in kidney mitochondria after rats are administered TFEC include mitAspAT, HSP70, HSP60, the E2k and E3 subunits of KGDHC, and aconitase. This labeling pattern is entirely consistent with mitAspAT acting as a mitochondrial TFEC β-lyase. Thioacylation of mitAspAT is presumably due to release of a reactive sulfur-containing fragment at the active site of this enzyme. As noted above, the high-Mr lyase contains both HSP70 and mitAspAT, accounting for the thioacylation of HSP70. mitAspAT is thought to be part of a metabolon that also includes KGDHC and aconitase (24). KGDHC activity is decreased in the kidneys of TFEC-treated rats (58,59) and in TFEC-treated PC12 cells (36). It was proposed that the susceptibility of KGDHC to inactivation by TFEC and to its thioacylation in rats treated with TFEC is due to close juxtapositioning of mitAspAT to KGDHC and to toxicant targeting of a reactive sulfur-containing fragment from mitAspAT to KGDHC (24,25,59).

By analogy with the bioactivation of halogenated cysteine S-conjugates, we suggest that mitAspAT contributes to the toxicity of cisplatin in kidney mitochondria in vivo. If mitAspAT is able to catalyze a β-elimination reaction with the cisplatin-cysteine S-conjugate, and β elimination leads to toxicity, then overexpression of this enzyme in a suitable cell line should lead to increased cisplatin toxicity, that can be attenuated by AOAA. In our experiments, overexpression of mitAspAT in confluent LLC-PK1 cells leads to increased cisplatin toxicity, which can be overcome by AOAA treatment (Figures 3 and 4). Overexpression of mitAspAT, however, had no effect on cisplatin toxicity in dividing LLC-PK1 cells (Figure 5). This finding is consistent with the hypothesis that the metabolism of cisplatin to a reactive thiol does not contribute to cisplatin toxicity in dividing cells, but it does so in confluent, non-dividing cells.

Comparison of Cisplatin and Halogenated Alkene-induced Toxicity to Kidney

Halogenated alkenes are metabolized to their corresponding cysteine S-conjugates, which are nephrotoxicants. The reactive RSH fragments generated from toxic halogenated cysteine S-conjugates induce lipid peroxidation and deplete energy stores (70,71). The S3 regions of the kidney proximal tubules are especially susceptible to the effects of toxic cysteine S-conjugates (72). Mitochondria are the prime targets of toxic halogenated cysteine S-conjugates leading to cell death in kidney cells (24,25).

Toxicity induced by cisplatin is similar to that induced by halogenated alkenes. In the kidney, the proximal tubules are targeted by cisplatin and mitochondria are especially vulnerable (73). Cisplatin-induced renal damage results in inhibition of complexes I to IV of the respiratory chain (73), dose-dependent inhibition of oxygen consumption and inhibition of Na+-K+-ATPase activity (50), decreased respiration and oxidative phosphorylation, altered mitochondrial transmembrane potential in renal proximal tubule cells (74), and increased ROS production (74). These findings are consistent with our hypothesis that the toxicity of cisplatin in confluent cells is the result of the metabolism of a Pt-cysteine S-conjugate to a highly reactive thiol by mitochondrial cysteine S-conjugate β-lyases. In contrast, Tacka et al. showed that exposure of dividing Jurkat cells to low concentrations of cisplatin that are toxic to cells in logarithmic growth, had no immediate effect on cellular mitochondrial oxygen consumption (75). Cellular respiration and viability did not decrease until 24 hr as the cells underwent apoptosis (75). These data are consistent with the hypothesis that cisplatin-induced DNA damage triggers cell death in dividing cells.

Toxicant Targeting May Contribute to Cisplatin-induced Damage to Kidney Mitochondria

The present work is consistent with the hypothesis that a metabolite of cisplatin generated in the kidney, interferes with energy metabolism in the mitochondria. The present findings show that KGDHC activity and, to a lesser extent, aconitase activity are selectively decreased in LLC-PK1 cells exposed to cisplatin. This finding suggests that bioactivation of cisplatin, in a similar fashion to that proposed for TFEC (24,58), may involve targeting of a reactive fragment from the active site of mitAspAT to a metabolon composed in part of mitAspAT, KGDHC and aconitase. We suggest that cisplatin is converted to the corresponding cysteine S-conjugate, which is a β-lyase substrate of mitAspAT. The Pt-S compound resulting from the lyase reaction then binds to proteins in close proximity such as KGDHC and aconitase, thereby inactivating them. The Pt-S compound also apparently slowly inactivates mitAspAT. We found a significant decline in total AspAT activity 24 h after LLC-PK1 cells had been exposed to cisplatin for 3 h. Inhibition of AspAT would lead to disruption of the malate-aspartate shuttle and impeded passage of reducing equivalents across the mitochondrial membrane (52). In summary, inhibition of mitAspAT, KGDHC and aconitase may contribute to the cisplatin-induced mitochondrial dysfunction of energy metabolism in kidney cells.

What Accounts for the Selective Toxicity of the Halogenated Alkenes and Cisplatin to the Renal Proximal Tubules?

A major question that remains to be answered is why the renal proximal tubule cells are killed by cisplatin and by nephrotoxic halogenated alkenes while other cells in the kidney and most other non-dividing cells throughout the body are not affected to the same extent by these toxicants. mitAspAT is widely distributed among various organs (45). Liver, heart, brain, kidney and skeletal muscles exhibit high levels of mitAspAT activity (45). Therefore, the nephrotoxicity of halogenated alkenes and cisplatin cannot be explained on the basis of the tissue expression of this enzyme. Important factors may include uptake of cisplatin into the kidney, activities of glutathione S-transferases and export pumps for the cisplatin-glutathione conjugates, activities of the ecto-enzymes γ-glutamyl transpeptidase (27) and aminopeptidase N (76) on the surface of the renal proximal tubules and an uptake system for cysteine S-conjugates in the kidney (77).

Summary

Previous studies have provided evidence that bioactivation of cisplatin involves the action of cisplatin-cysteine S-conjugate and PLP-containing cysteine S-conjugate β-lyases (8–11,13,40). Analogy with the bioactivation of nephrotoxic, halogenated alkenes, suggested that the cysteine S-conjugate β-lyases generated a reactive sulfur-containing fragment from the cisplatin-cysteine S-conjugate, and that this fragment bound to proteins (8–11,13,40). The present work shows that in the kidney, Pt adduction to proteins in vivo preferentially occurs in the mitochondrial fraction. We also showed that cisplatin-induced toxicity toward kidney mitochondria is associated with targeting of enzymes of energy metabolism, namely KGDHC, and to a lesser extent aconitase. The GGT-dependent, PLP-β-lyase dependent pathway does not play a role in the toxicity of cisplatin to dividing cells (40). It might be possible to administer reversible inhibitors to temporarily diminish binding of cisplatin-cysteine S-conjugate to the active site of mitAspAT. This strategy may allow higher doses of cisplatin to be administered to cancer patients, while at the same time minimizing toxicity to the kidneys.

Footnotes

This work was supported by a grant from the Presbyterian Health Foundation, Oklahoma City, OK (to M.H.M.) and by NIH Grants CA57530 (to M.H.M.), ES08421 (to A.J.L.C) and AG14930 (to A.J.L.C and G.E.G.).

Abbreviations: AOAA, aminooxyacetic acid; AspAT, aspartate aminotransferase; cisplatin, cisdiamminedichloroplatinum(II); cytAspAT, cytosolic aspartate aminotransferase; DCVC, S-(1,2-dichlorovinyl)-L-cysteine; DMEM, Dulbecco’s Modified Eagle’s Medium; GFAAS, graphite furnace atomic absorption spectrometry; FBS, fetal bovine serum; GAPDH, glyceraldehyde 3-phosphate dehydrogenase; GDH, glutamate dehydrogenase; GGT, γ-glutamyl transpeptidase; GTK, glutamine transaminase K; HBSS, Hanks' balanced salt solution; KGDHC, α-ketoglutarate dehydrogenase complex; LDH, lactate dehydrogenase; MDH, malate dehydrogenase; mitAspAT, mitochondrial aspartate aminotransferase; MTT, 3-[4,5-dimethylthiazol-2-yl]-2,5-diphenyltetrazolium bromide; pmitAspAT, precursor of mitochondrial aspartate aminotransferase; PLP, pyridoxal 5'-phosphate; PMP, pyridoxamine 5'-phosphate; SD, standard deviation; SEM, standard error of the mean; TFEC, S-(1,1,2,2-tetrafluoroethyl)-L-cysteine.

REFERENCES

- 1.Masters JR, Koberle B. Curing metastatic cancer: lessons from testicular germ-cell tumours. Nat. Rev. Cancer. 2003;3:517–525. doi: 10.1038/nrc1120. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Arany I, Safirstein RL. Cisplatin nephrotoxicity. Semin. Nephrol. 2003;23:460–464. doi: 10.1016/s0270-9295(03)00089-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Steeghs N, de Jongh FE, Sillevis Smitt PA, van den Bent MJ. Cisplatin-induced encephalopathy and seizures. Anticancer Drugs. 2003;14:443–446. doi: 10.1097/00001813-200307000-00009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Siddik ZH. Cisplatin: mode of cytotoxic action and molecular basis of resistance. Oncogene. 2003;22:7265–7279. doi: 10.1038/sj.onc.1206933. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Boulikas T, Vougiouka M. Cisplatin and platinum drugs at the molecular level (review) Oncology Reports. 2003;10:1663–1682. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Chu C, Sartorelli AC. Cancer Chemotherapy. In: Katzung BG, editor. Basic and Clinical Pharmacology. New York: Lang Medical Books McGraw-Hill; 2004. pp. 898–930. [Google Scholar]

- 7.Daley-Yates PT, McBrien DCH. Cisplatin metabolites in plasma, A study of their pharmacokinetics and importance in the nephrotoxic and antitumour activity of cisplatin. Biochem. Pharmacol. 1984;33:3063–3070. doi: 10.1016/0006-2952(84)90610-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Hanigan MH, Gallagher BC, Taylor PT, Jr, Large MK. Inhibition of gamma-glutamyl transpeptidase activity by acivicin in vivo protects the kidney from cisplatin-induced toxicity. Cancer Res. 1994;54:5925–5929. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Hanigan MH, Lykissa ED, Townsend DM, Ou CN, Barrios R, Lieberman MW. Gamma-glutamyl transpeptidase-deficient mice are resistant to the nephrotoxic effects of cisplatin. Am. J. Pathol. 2001;159:1889–1894. doi: 10.1016/s0002-9440(10)63035-0. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Townsend DM, Hanigan MH. Inhibition of gamma-glutamyl transpeptidase or cysteine S-conjugate beta-lyase activity blocks the nephrotoxicity of cisplatin in mice. J. Pharmacol. Exp. Ther. 2002;300:142–148. doi: 10.1124/jpet.300.1.142. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Townsend DM, Deng M, Zhang L, Lapus MG, Hanigan MH. Metabolism of cisplatin to a nephrotoxin in proximal tubule cells. J. Am. Soc. Nephrol. 2003;14:1–10. doi: 10.1097/01.asn.0000042803.28024.92. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Townsend DM, Marto JA, Deng M, Macdonald TJ, Hanigan MH. High pressure liquid chromatography and mass spectrometry characterization of the nephrotoxic biotransformation products of Cisplatin. Drug Metab Dispos. 2003;31:705–713. doi: 10.1124/dmd.31.6.705. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Hanigan MH, Devarajan P. Cisplatin nephrotoxicity:molecular mechanisms. Cancer Therapy. 2003;1:47–61. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Mayer RD, Lee K, Cockett ATK. Inhibition of cisplatin-induced nephrotoxicity in rats by buthionine sulfoximine, a glutathione synthesis inhibitor. Cancer Chemother. Pharmacol. 1987;20:207–210. doi: 10.1007/BF00570486. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Dekant W, Vamvakas S, Anders MW. Formation and fate of nephrotoxic and cytotoxic glutathione S-conjugates: Cysteine conjugate beta-lyase pathway. In: Anders MW, Dekant W, editors. Advances in Pharmacology. Vol. 27. New York: Academic Press Inc; 1995. pp. 115–162. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.McGoldrick TA, Lock EA, Rodilla V, Hawksworth GM. Renal cysteine conjugate C-S lyase mediated toxicity of halogenated alkenes in primary cultures of human and rat proximal tubular cells. Arch. Toxicol. 2003;77:365–370. doi: 10.1007/s00204-003-0459-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Hayden PJ, Yang Y, Ward AJ, Dulik DM, McCann DJ, Stevens JL. Formation of difluorothionoacetyl-protein adducts by S-(1,1,2,2-tetrafluoroethyl)-L-cysteine metabolites: nucleophilic catalysis of stable lysyl adduct formation by histidine and tyrosine. Biochemistry. 1991;30:5935–5943. doi: 10.1021/bi00238a018. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Anders MW, Dekant W. Glutathione-dependent bioactivation of haloalkenes. Annual Review of Pharmacology and Toxicology. 1998;38:501–537. doi: 10.1146/annurev.pharmtox.38.1.501. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Cooper AJL. Mechanisms of cysteine S-conjugate beta-lyases. Advances in Enzymology. 1998;72:199–238. doi: 10.1002/9780470123188.ch6. 72. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Stevens JL. Isolation and characterization of a rat liver enzyme with both cysteine conjugate beta-lyase and kynureninase activity. J. Biol. Chem. 1985;260:7945–7950. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Lash LH, Elfarra AA, Anders MW. Renal cysteine conjugate beta-lyase - Bioactivation of nephrotoxic cysteine S-conjugates in mitochondrial outer-membrane. J. Biol. Chem. 1986;261:5930–5935. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Jones TW, Chen Q, Schaeffer VH, Stevens JL. Immunohistochemical localization of glutamine transaminase K, a rat kidney cysteine conjugate b-lyase, and the relationship to the segment specificity of cysteine conjugate nephrotoxicity. Mol. Pharmacol. 1988;34:621–627. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Stevens JL, Ayoubi N, Robbins JD. The role of mitochondrial matrix enzymes in the metabolism and toxicity of cysteine conjugates. J. Biol. Chem. 1988;263:3395–3401. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Cooper AJL, Bruschi SA, Anders MW. Toxic, halogenated cysteine S-conjugates and targeting of mitochondrial enzymes of energy metabolism. Biochem. Pharmacol. 2002;64:553–564. doi: 10.1016/s0006-2952(02)01076-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Cooper AJ, Pinto JT. Cysteine S-conjugate beta-lyases. Amino Acids. 2006;30:1–15. doi: 10.1007/s00726-005-0243-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Stevens JL, Robbins JD, Byrd RA. A purified cysteine conjugate beta-lyase from rat kidney cytosol. Requirement for an alpha-keto acid or an amino acid oxidase for activity and identity with soluble glutamine transaminase K. J. Biol. Chem. 1986;261:15529–15537. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Hanigan MH, Frierson HF., Jr Immunohistochemical detection of gamma-glutamyl transpeptidase in normal human tissue. J. Histochem. Cytochem. 1996;44:1101–1108. doi: 10.1177/44.10.8813074. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.McIntyre TM, Curthoys NP. Renal catabolism of glutathione: characterization of a particulate rat renal dipeptidase that catalyzes the hydrolysis of cysteinylglycine. J. Biol. Chem. 1982;257:11915–11921. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Cooper AJL, Bruschi SA, Iriarte A, Martinez-Carrion M. Mitochondrial aspartate aminotransferase catalyses cysteine S-conjugate beta-lyase reactions. Biochem. J. 2002;368:253–261. doi: 10.1042/BJ20020531. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Hayden PJ, Stevens JL. Cysteine conjugate toxicity, metabolism, and binding to macromolecules in isolated rat kidney mitochondria. Mol. Pharmacol. 1990;37:468–476. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.McKinney LL, Picken JCJ, Weakley FB, Eldridge AC, Campbell RE, Cowan JC, Biester HE. Possible toxic factor of trichloroethylene-extracted soybean oil meal. Journal of the American Chemical Society. 1959;81:909–915. [Google Scholar]

- 32.Elfarra AA, Jakobson I, Anders MW. Mechanism of S-(1,2-dichlorovinyl)glutathione-induced nephrotoxicity. Biochem. Pharmacol. 1986;35:283–288. doi: 10.1016/0006-2952(86)90527-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.de Ceaurriz J, Ban M. Role of Gamma-Glutamyl-Transpeptidase and Beta-Lyase in the Nephrotoxicity of Hexachloro-1,3-Butadiene and Methyl Mercury in Mice. Tox. Lett. 1990;50:249–256. doi: 10.1016/0378-4274(90)90017-g. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Hensley K, Kotake Y, Sang H, Pye QN, Wallis GL, Kolker LM, Tabatabaie T, Stewart CA, Konishi Y, Nakae D, Floyd RA. Dietary choline restriction causes complex I dysfunction and increased H2O2 generation in liver mitochondria. Carcinogenesis. 2000;21:983–989. doi: 10.1093/carcin/21.5.983. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Wallin A, Gerdes RG, Morgenstern R, Jones TW, Ormstad K. Features of microsomal and cytosolic glutathione conjugation of hexachlorobutadiene in rat liver. Chem. Biol. Interact. 1988;68:1–11. doi: 10.1016/0009-2797(88)90002-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Park LCH, Gibson GE, Bunik V, Cooper AJL. Inhibition of select mitochondrial enzymes in PC12 cells exposed to S-(1,1,2,2-tetrafluoroethyl)-L-cysteine. Biochem. Pharmacol. 1999;58:1557–1565. doi: 10.1016/s0006-2952(99)00247-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Srinivas KS, Chandrasekar G, Srivastava R, Puvanakrishnan R. A novel protocol for the subcellular fractionation of C3A hepatoma cells using sucrose density gradient centrifugation. J. Biochem. Biophys. Methods. 2004;60:23–27. doi: 10.1016/j.jbbm.2004.04.011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Altieri F, Mattingly JR, Rodriguez-Berrocal FJ, Youssef J, Iriarte A, Wu TH, Martinez-Carrion M. Isolation and properties of a liver mitochondrial precursor protein to aspartate-aminotransferase expressed in Escherichia-Coli. J. Biol. Chem. 1989;264:4782–4786. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Artigues A, Crawford DL, Iriarte A, Martinez-Carrion M. Divergent Hsc70 binding properties of mitochondrial and cytosolic aspartate aminotransferase - Implications for their segregation to different cellular compartments. J. Biol. Chem. 1998;273:33130–33134. doi: 10.1074/jbc.273.50.33130. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Zhang L, Hanigan MH. Role of cysteine S-conjugate beta-lyase in the metabolism of cisplatin. J. Pharmacol. Exp. Ther. 2003;306:988–994. doi: 10.1124/jpet.103.052225. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Mattingly JR, Jr, Youssef J, Iriarte A, Martinez-Carrion M. Protein folding in a cell-free translation system. The fate of the precursor to mitochondrial aspartate aminotransferase. J. Biol. Chem. 1993;268:3925–3937. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Torella C, Mattingly JR, Jr, Artigues A, Iriarte A, Martinez-Carrion M. Insight into the conformation of protein folding intermediate(s) trapped by GroEL. J. Biol. Chem. 1998;273:3915–3925. doi: 10.1074/jbc.273.7.3915. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Mosmann T. Rapid colorimetric assay for cellular growth and survival: Application to proliferation and cytotoxicity assays. J. Immunol. Methods. 1983;65:55–63. doi: 10.1016/0022-1759(83)90303-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Bubber P, Haroutunian V, Fisch G, Blass JP, Gibson GE. Mitochondrial abnormalities in Alzheimer brain: mechanistic implications. Ann. Neurol. 2005;57:695–703. doi: 10.1002/ana.20474. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Parli JA, Godfrey DA, Ross CD. Separate enzymatic microassays for aspartate-aminotransferase isoenzymes. Biochim. Biophys. Acta. 1987;925:175–184. doi: 10.1016/0304-4165(87)90107-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Cooper AJL. Purification of soluble and mitochondrial glutamine transaminase K from rat kidney. Use of a sensitive assay involving transamination between L-phenylalanine and alpha-keto-gamma-methiolbutyrate. Anal. Biochem. 1978;89:451–460. doi: 10.1016/0003-2697(78)90374-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Cooper AJL, Meister A. Comparative studies of glutamine transaminases from rat tissues. Comparative. 1981;69B:137–145. [Google Scholar]

- 48.Cooper AJL, Pinto JT. Aminotransferase, L-amino acid oxidase and beta-lyase reactions involving L-cysteine S-conjugates found in allium extracts. Relevance to biological activity? Biochem. Pharmacol. 2005;69:209–220. doi: 10.1016/j.bcp.2004.08.034. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Cooper AJL, Sheu KR, Burke JR, Onodera O, Strittmatter WJ, Roses AD, Blass JP. Transglutaminase-catalyzed inactivation of glyceraldehyde 3-phosphate dehydrogenase and alpha-ketoglutarate dehydrogenase complex by polyglutamine domains of pathological length. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U. S. A. 1997;94:12604–12609. doi: 10.1073/pnas.94.23.12604. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Brady HR, Kone BC, Stromski ME, Zeidel ML, Giebisch G, Gullans SR. Mitochondrial injury: an early event in cisplatin toxicity to renal proximal tubules. Am. J. Physiol. 1990;258:F1181–F1187. doi: 10.1152/ajprenal.1990.258.5.F1181. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Lange RC, Spencer RP, Harder HC. The antitumor agent cis-Pt(NH3)2Cl2: Distribution studies and dose calculations for 193m Pt and 195m Pt. J. Nuclear Medicine. 1973;14:191–195. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Fitzpatrick SM, Cooper AJL, Duffy TE. Use of beta-methylene-D,L-aspartate to assess the role of aspartate aminotransferase in cerebral oxidative metabolism. J. Neurochem. 1983;41:1370–1383. doi: 10.1111/j.1471-4159.1983.tb00835.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Yamauchi A, Stijntjes GJ, Commandeur JNM, Vermeulen NPE. Purification of glutamine transaminase K/cysteine conjugate beta-lyase from rat renal cytosol based on hydrophobic interaction HPLC and gel permeation FPLC. Protein Expr. Purif. 1993;4:552–562. doi: 10.1006/prep.1993.1073. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Plant N, Kitchen I, Goldfarb PS, Gibson GG. Developmental modulation of cysteine conjugate beta-lyase/glutamine transaminase K/kynurenine aminotransferase mRNA in rat brain. Eur. J. Drug Metab Pharmacokinet. 1997;22:335–339. doi: 10.1007/BF03190967. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Ho HK, Hu ZH, Tzung SP, Hockenbery DM, Fausto N, Nelson SD, Bruschi SA. BCL-xL overexpression effectively protects against tetrafluoroethylcysteine-induced intramitochondrial damage and cell death. Biochem. Pharmacol. 2005;69:147–157. doi: 10.1016/j.bcp.2004.08.030. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Chen Y, Cai J, Anders MW, Stevens JL, Jones DP. Role of mitochondrial dysfunction in S-(1,2-dichlorovinyl)-l-cysteine-induced apoptosis. Toxicol. Appl. Pharmacol. 2001;170:172–180. doi: 10.1006/taap.2000.9107. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Bruschi SA, West KA, Crabb JW, Gupta RS, Stevens JL. Mitochondrial Hsp60 (P1 protein) and A Hsp70-like protein (mortalin) are major targets for modification during S-(1,1,2,2-tetrafluoroethyl)-L-cysteine-induced nephrotoxicity. J. Biol. Chem. 1993;268:23157–23161. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Bruschi SA, Lindsay JG, Crabb JW. Mitochondrial stress protein recognition of inactivated dehydrogenases during mammalian cell death. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U. S. A. 1998;95:13413–13418. doi: 10.1073/pnas.95.23.13413. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.James EA, Gygi SP, Adams ML, Pierce RH, Fausto N, Aebersold RH, Nelson SD, Bruschi SA. Mitochondrial aconitase modification, functional inhibition, and evidence for a supramolecular complex of the TCA cycle by the renal toxicant S-(1,1,2,2-tetrafluoroethyl)-L-cysteine. Biochemistry. 2002;41:6789–6797. doi: 10.1021/bi020038j. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Elfarra AA, Duescher RJ, Hwang IY, Sicuri AR, Nelson JA. Targeting 6-thioguanine to the kidney with S-(guanin-6-yl)-L-cysteine. J. Pharmacol. Exp. Ther. 1995;274:1298–1304. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Mosca M, Croci C, Mostardini M, Breton J, Malyszko J, Avanzi N, Toma S, Benatti L, Gatti S. Tissue expression and translational control of rat kynurenine aminotransferase/glutamine transaminase K mRNAs. Biochim. Biophys. Acta. 2003;1628:1–10. doi: 10.1016/s0167-4781(03)00071-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Cooper AJL. Glutamine aminotransferases and amidases. In: Kvamme E, editor. Glutamine and Glutamate in Mammals. Boca Raton, Florida: CRC Press; 1988. pp. 33–52. [Google Scholar]

- 63.Rooseboom M, Schaaf G, Commandeur JNM, Vermeulen NPE, Fink-Gremmels J. Beta-lyase-dependent attenuation of cisplatin-mediated toxicity by selenocysteine Se-conjugates in renal tubular cell lines. J. Pharmacol. Exp. Ther. 2002;301:884–892. doi: 10.1124/jpet.301.3.884. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Abraham DG, Thomas RJ, Cooper AJL. Glutamine transaminase K is not a major cysteine S-conjugate beta-lyase of rat kidney mitochondria: evidence that a high-molecular weight enzyme fulfills this role. Mol. Pharmacol. 1995;48:855–860. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Abraham DG, Patel PP, Cooper AJL. Isolation from rat kidney of a cytosolic high-molecular-weight cysteine-S-conjugate beta-lyase with activity toward leukotriene E(4) J. Biol. Chem. 1995;270:180–188. doi: 10.1074/jbc.270.1.180. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]