Abstract

Background and Purpose

Acute stroke education has focused on stroke symptom recognition. Lack of education about stroke preparedness and appropriate actions may prevent people from seeking immediate care. Few interventions have rigorously evaluated preparedness strategies in multiethnic community settings.

Methods

The Acute Stroke Program of Interventions Addressing Racial and Ethnic Disparities (ASPIRE) project is a multi-level program utilizing a community engaged approach to stroke preparedness targeted to underserved black communities in the District of Columbia (DC). This intervention aimed to decrease acute stroke presentation times and increase intravenous tissue plasminogen activator (IV tPA) utilization for acute ischemic stroke.

Results

Phase 1 included: 1) enhancement of EMS focus on acute stroke; 2) hospital collaborations to implement and/or enrich acute stroke protocols and transition DC hospitals toward Primary Stroke Center certification; and 3) pre-intervention acute stroke patient data collection in all 7 acute care DC hospitals. A community advisory committee, focus groups, and surveys identified perceptions of barriers to emergency stroke care. Phase 2 included a pilot intervention and subsequent citywide intervention rollout. A total of 531 community interventions were conducted with over 10,256 participants reached; 3289 intervention evaluations were performed, and 19,000 preparedness bracelets and 14,000 stroke warning magnets were distributed. Phase 3 included an evaluation of EMS and hospital processes for acute stroke care and a yearlong post-intervention acute stroke data collection period to assess changes in IV tPA utilization.

Conclusions

We report the methods, feasibility, and pre-intervention data collection efforts of the ASPIRE intervention.

Keywords: Stroke, Prevention, Community, Disparities

Stroke has a disproportionate impact on blacks compared to whites as reflected in significantly higher incidence and mortality rates.1–5 Several prospective studies have demonstrated disparities in acute stroke treatment and emergency department (ED) presentation time.6–9 Explanations for treatment disparities are difficult to elucidate, but include health literacy, access to care, socioeconomic status (SES), patient mistrust, and clinician bias.10–17 While prevention strategies focus on long-term risk factor control, strategies to increase utilization of acute stroke treatment with thrombolytic therapies would best be characterized as “preparedness” and include competencies where lay individuals recognize stroke symptoms, and take immediate action to seek emergency treatment.18 Campaigns focused solely on recognition of stroke symptoms have been suboptimal in promoting action around stroke preparedness, possibly due to inadequate attention to health literacy, or cultural tailoring. While a few interventions have increased stroke knowledge using culturally tailored strategies, there has been no linkage to behavioral change in large, medically underserved community settings.8, 9, 11, 19, 20 Given the complexity underlying racial treatment disparities, few interventions emphasize the importance of integrating systems change with behavioral change when designing interventions.

The District of Columbia is an urban predominately black community with identified disparities in IV tPA administration for acute stroke.11 A survey among DC veterans found that blacks were less likely than whites to say they would call 911 if experiencing stroke symptoms (40% versus 51%). We have reported that blacks in DC were less likely to be treated with IV tPA and these delays associated with stroke severity, contraindications to treatment, or delayed presentation.21 Given disparities in stroke treatment and lack of acute stroke education in DC, we sought to address these issues through the design and evaluation of a citywide stroke preparedness intervention.

ASPIRE is a multilevel program, examining whether a community engaged, three-pronged approach (individual/community, hospital, EMS) to acute stroke preparedness targeted to underserved black communities in DC will lead to behavioral change as defined by; 1) improved time to arrival to ED upon stroke symptom onset, and 2) increased IV tPA utilization rates (table 1). We report the methods, feasibility and preliminary data collection efforts of the ASPIRE intervention.

Table 1.

Overview of the Multi-dimensional Nature of the ASPIRE Intervention

| Community |

|

|

|

| Hospital |

|

|

|

| DC EMS |

|

|

|

METHODS

Phase 1: Pre-intervention

Community

Key community stakeholders including stroke survivors, stroke caregivers, a local community advocate, and a minister, were assembled to serve on the Community Advisory Committee (CAC). The CAC advised the research team on cultural sensitivity, appropriate outreach, and recruitment strategies, and worked with the research team to interpret focus groups results, key informant interviews, and surveys. Eight focus groups explored knowledge of stroke risk factors, signs and symptoms, attitudes and beliefs regarding stroke treatment and experienced or perceived treatment barriers. Each audio taped and transcribed focus group consisted of 8–10 individuals, balanced by gender. This process elucidated the subjective attitudes and norms of community members and examined themes identified in the brief survey, which then informed intervention development.

In developing stroke education materials for ASPIRE, existing tools were evaluated, including the NINDS Know Stroke campaign, the American Heart Association (AHA) Power to End Stroke (PTES) campaign, Stroke Warning Information for Faster Treatment (SWIFT), and the Massachusetts Health Department stroke video, “Stroke Heroes Act FAST (Face, Arm, Speech, Time)”22–24. The CAC reviewed these materials, and helped culturally and linguistically tailor to the community needs based on identified barriers. Specifically, the materials were community-placed (references to the DC metro area); contained simple messaging focused on preparedness rather than the entire spectrum of stroke (including prevention, risk factors, recovery and psychosocial issues); were visually appealing with people and locations appearing relatable to the DC community; and contained messages that provided instruction and hope. For example, since we found the largest barrier to calling 911 was the belief that nothing can be done to treat a stroke, we created clear messages that included the treatability of stroke with rapid action while promoting preparedness and self-efficacy including “Stroke is Treatable, Call 911” and “Stroke: I am prepared to Call 911”23. To culturally tailor our materials, a PowerPoint slide set and a chart presentation were developed with community-placed messaging. These included education on higher risk of stroke among black populations, use of lay terms and visuals for stroke symptoms, and active decision slides about costs and benefits of calling 911.25 ASPIRE integrated aspects of “Stroke Heroes Act FAST” including animation, repetition (including song), simple instructions about what to do coupled with self-efficacy, such as “You can beat a stroke by calling 9-1-1”22. In partnership with NINDS Communications, ASPIRE developed reinforcement materials including refrigerator magnets, bracelets, presentation charts, and bus advertisements that included pictures of stroke warning signs and action messages such as “call 911”.

Hospital

Between January 2008 and February 2009, trained clinical research coordinators collected demographic information, acute stroke parameters (time to presentation and use of IV tPA), and risk factors for ischemic stroke patients presenting to all seven of the acute care hospitals in Washington, DC including, Howard University Hospital, Georgetown University Hospital, Washington Hospital Center, Providence Hospital, Sibley Memorial Hospital, and United Medical Center. Coordinator training included chart review protocols, documentation of acute stroke parameters (IV tPA eligibility, treatment, and discharge outcomes), cultural competence, and techniques for approaching patients and families. Coordinators conducted prospective stroke surveillance through identification of acute strokes from emergency department admissions using pre-specified stroke screening terms. The stroke admission list was cross-referenced with each hospital’s neurology consultation service. Passive surveillance included identification by discharge ICD-9 codes for acute ischemic stroke (433.01, 433.11, 433.21, 433.31, 433.81, 433.91, 434.01, 434.11, 434.91, 436).

A key objective of ASPIRE was to work with hospitals to attain Primary Stroke Center certification through The Joint Commission (TJC). These hospitals already had neurology consultation available in the ED and an infrastructure to provide tPA. Physician Stroke Champions (SC), who were already stroke leaders within their hospitals, were identified at each hospital to introduce ASPIRE and encourage participation.

A comparison group of five hospitals in Baltimore, Maryland, reported data annually by passive surveillance on the total number and demographics of acute ischemic strokes (identified by discharge ICD-9 codes and patients treated with IV tPA). These hospitals had similar demographics and urban location, but had no ongoing culturally focused stroke education efforts. This allowed us to capture secular trends in tPA utilization which would be important in evaluating the impact of ASPIRE in DC.

Washington DC Emergency Medical Services (DC EMS)

As part of the multi-level intervention the ASPIRE team met quarterly with DC EMS to review and optimize stroke EMS protocols, discuss study progress, work with EMS database staff to link EMS log sheets to ASPIRE subjects, and to evaluate potential increase in EMS utilization over the course of the study. The ASPIRE team worked with EMS database staff to identify all potential stroke cases residing in the DC metro area as defined by zip code and ward number. Each case had a unique EMS record number, which was also recorded in medical records when patients arrived at the hospital. EMS record numbers were retrieved for all ASPIRE cases as part of chart abstraction. If an EMS record number was missing, other variables (gender, age, address, etc.) were used to link EMS data with medical record data.

Phase 2: Intervention

Community

In July 2009, ASPIRE initiated a single DC Ward pilot preparedness intervention to test the feasibility of identifying all stroke admissions with linkage to EMS utilization for the 6 month pre and post intervention periods, and to optimize the ASPIRE educational materials. The one year citywide ASPIRE intervention began in fall 2010, expanding the pilot intervention efforts to reach residents of all 8 DC wards. Educational sessions were administered at senior centers, schools, employee sites, churches, health centers, and other community organizations; and included identification and training of a point person at each site to provide ongoing ASPIRE education.

Hospital

At the hospitals, a major effort was undertaken by the study team to work with Physician SCs, including quarterly check-ins, to obtain updates on TJC stroke center certification. The ASPIRE team shared order set templates, provided guidance in recruitment of key personnel, and provided stroke education and training through clinical and research in-services. Stroke preparedness bracelets and magnets were provided for distribution to staff and patients.

DC EMS

ASPIRE partnered with AHA sponsored DC Stroke Collaborative to assist in DC EMS’s April 2009 diversion protocol, which required DC ambulances to transport all suspected stroke cases to a DC-certified Primary Stroke Center. The research protocol was modified such that hospital data collected on acute stroke patients presenting to DC emergency departments would evaluate the impact of this transport modification on stroke patient arrival times and treatment.

Phase 3: Post Intervention Evaluation

After completion of the citywide intervention, ASPIRE educational materials served as ongoing outreach resources. For the subset of community participants invited to participate in stroke knowledge assessments before and after education sessions, 6 month follow up surveys were administered. Coordinators documented post-intervention acute stroke data parameters. Structured interviews on ED arrival, barriers to calling 911, risk factors, and stroke knowledge were conducted with a subset of patients arriving within 3 hours, and matched controls. These interviews included soliciting information about whether the patient had received prior stroke education and if so, from what source (e.g. ASPIRE). ASPIRE documented progress towards TJC Stroke Center certification. DC EMS personnel shared annual stroke reports, providing data on dispatch and paramedic stroke impressions, transport times, hospital locations, and patient demographics.

Statistical Analysis

The ASPIRE intervention was designed to intervene at the individual/community, EMS and hospital levels and each level will be evaluated separately. The primary objective of ASPIRE is to compare tPA treatment rates pre- and post-intervention in DC hospitals. Power was based on an a priori assumption of a difference between baseline (pre-intervention) tPA treatment rates and post-intervention rate and assumed an increase from 2% to 8% with a secular increase of 1%. Sample sizes were estimated using Chi-square tests with one-sided type I error of 5% and 80% power and further adjusted to account for the within-cluster correlation in hospital using an inflation factor based upon an assumption that care is different in different hospital settings26. The asymptotic Z test will be used to evaluate the statistical significance of pre-post intervention increase in the percent of tPA treatment of all ischemic stroke patients in the DC intervention hospitals combined, after adjusting for any secular increase of tPA treatment rates27. For secondary analyses, multiple logistic regression models will be employed to extend the primary analysis by examining the impact of age, gender, race, and health insurance status on change in tPA utilization before and after the intervention period. The proportion of tPA utilization among eligible patients during the baseline and post-intervention periods will be compared using the same method.

In the evaluation of the hospital-based interventions, change in benchmark times for patients within 3 hours of symptom onset before and after the intervention will be measured. To evaluate the EMS interventions, change in response time from 911 call to ED arrival will be measured before and after the intervention phase.

PRELIMINARY RESULTS

Between January 2008 and February 2009, coordinators collected demographic and acute stroke parameters on 1256 ischemic stroke patients. Of the subjects from the pre-intervention period with arrival times less than 48 hours, the median arrival time to the ED was 9 hours, and 20% presented < 3 hours. Coordinators administered 373 structured interviews to acute ischemic stroke patients arriving within 3 hours of last known well and matched controls arriving > 3 hours.

In the pilot feasibility study, fifty education sessions were conducted in church, civic, educational and work organizations over a six month period in DC’s Ward 7. Pre-post pilot intervention acute ischemic stroke parameters were compared and EMS data was integrated into this dataset (Table 2). Pre-intervention, 142 ischemic strokes were identified in Ward 7 (mean age 63 years, 63% male, and 96% black). Fifty-six percent arrived via EMS, with a mean and median time to arrival of 1600 minutes (27.0 hours) and 890 minutes (14.8 hours). Post-intervention 115 ischemic stroke cases were identified (mean age 66 years, 47% male, and 89% black). Fifty percent arrived via EMS, with a mean and median time to arrival of 1423 min (23.7 hours) and 815 min (13.6 hours). Overall, there was a modest increase in cases arriving in the 4.5 hours group (pre 25% vs. post 28%, p=NS).

Table 2.

Pre-post ASPIRE Feasibility Study in Ward 7

| Characteristics | Pre-Intervention | Post-Intervention |

|---|---|---|

| Ischemic Strokes | 142 | 115 |

| Gender (Female) | 37% | 53% |

| Mean Age | 63 | 66 |

| Proportion using EMS | 56% | 50% |

| Race | ||

| White, Other | 4% | 11% |

| Black | 96% | 89% |

| Mean time from onset to ED | 1600 min (27 hrs) | 1423 min (23.7hrs) |

| Median time from onset to ED | 890 Minutes (14.8 hrs) | 815 (13.6 hrs) |

| Arriving <4.5 hours | 25% | 28% |

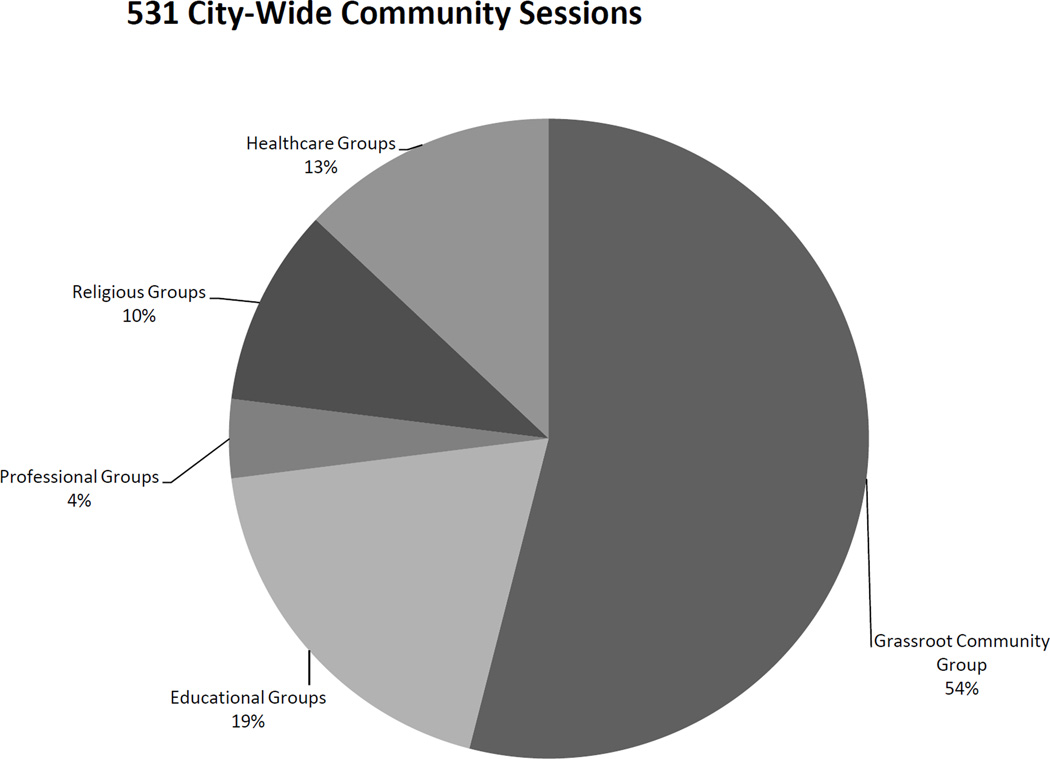

During the citywide intervention year (2010–2011), 531 community intervention sessions (Figure 1) were conducted reaching over 10,256 participants. A total of 3289 intervention evaluations were completed, and over 19,000 preparedness bracelets and 14,000 stroke warning magnets were distributed. Training in stroke knowledge, community education, research protocols, and cultural competence was conducted for 58 volunteer “DC Stroke Educators” to assist with ASPIRE’s citywide intervention efforts. DC Stroke Educators included health professionals and a diverse group of community members. Concurrently, and in collaboration with NINDS Office of Communications, ASPIRE disseminated stroke preparedness messages through a 1500 bus citywide advertisement campaign. Additional social marketing included articles in local newspapers, interviews for area radio, and social media sites.

Figure 1.

Distribution of Types of Community Organizations for ASPIRE Intervention

Coordinators from ASPIRE and Information Specialists from the EMS Fire Safety Education office met regularly to exchange information on upcoming outreach opportunities allowing both parties to maximize community engagement. ASPIRE worked with EMS staff on 12 community sessions, piloting a partnership beneficial to organizations seeking both stroke preparedness education and risk factor measurements.

At the end of the intervention, 4 hospitals were TJC Primary Stroke Centers. Two hospitals were in preparation for TJC review and were recognized as DC department of health primary stroke centers in 2011.

DISCUSSION

ASPIRE was a multilevel intervention targeting acute stroke preparedness in the community, hospital, and EMS, with the overall goal of increased IV tPA utilization in underserved black communities in the DC metro area. Several interventions have actively addressed preparedness with mixed success in different populations including stroke patients, adult communities, and youth2, 3, 9, 28. The Temple Foundation Stroke Project increased the tPA treatment rate for all ischemic stroke patients 4-fold above baseline following intervention (2.2% to 8.6%), but was limited in establishing temporal relationships between knowledge and preparedness29. The ASPIRE project extends this work with specific and measurable preparedness deliverables at the community, hospital, and EMS level to reduce stroke treatment disparities. ASPIRE’s design addresses previously identified variables linked to racial treatment disparities including limited awareness, access to care, socioeconomic status, patient mistrust, and clinician bias10–16. The ASPIRE findings to date highlight the complexity underlying racial treatment disparities and emphasizes the importance of systemic changes in hospitals where underserved patients are more likely to receive their care. While the primary objective of this study is to increase the number of stroke patients treated with IV tPA, pre-specified secondary outcomes include pre-post intervention assessments of EMS utilization, hospital arrival times, and an evaluation of the health economics of a multi-level citywide intervention.

The methodology applied to the ASPIRE project demonstrates numerous strategies needed to approach acute stroke preparedness at key levels of impact (EMS, hospital, community). Using a community engaged approach to establish trust; we identified key barriers to preparedness, and designed educational materials to address these issues.

The intensive hospital baseline data collection demonstrated race disparities in treatment with tPA within DC. Furthermore, in the ASPIRE feasibility pilot, there was a trend towards early acute stroke presentation post-intervention suggesting that multi-dimensional community efforts towards stroke preparedness may be successful. Implementation of citywide interventions can be a moving target and we learned that flexibility is the key to sustaining relationships. EMS had great interest in outreach collaboration, and our ongoing partnership in educating communities speaks to the potential sustainably for this program beyond ASPIRE research funding.

Implementing processes to ensure sustainability is a key component of multi-level interventions. ASPIRE was designed to promote sustainability through 1) overall increase in awareness of stroke preparedness through enhanced education of EMS and hospitals, 2) stroke center certification of all DC hospitals which provide systems for ongoing delivery of acute stroke care, 3) education of lay and medical communities through “train-the-trainer” sessions of key stakeholders and identification of medical stroke champions, and 4) development of accessible materials that can be adapted nationwide. A key component to sustainability of ASPIRE was a change in DC EMS policy that required diversion of stroke patients to primary stroke certified centers. The hospitals that participated in ASPIRE were engaged to varying degrees in the process of Stroke Center Certification, and part of this process included a financial commitment, which was enhanced by DC EMS policy. ASPIRE leveraged this opportunity to provide support to these hospitals through shared resources. If a hospital had no interest in treating stroke patients they would not have been involved in ASPIRE.

The ASPIRE intervention results will inform optimal strategies for stroke preparedness at individual and citywide levels. Further, given the burden of disparities in stroke, it will be of critical interest whether ASPIRE will be a model for reducing disparities in acute stroke treatment among black urban populations.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgements

We would like to acknowledge the collaboration of DC EMS, Marian Emr and the NINDS Office of Communications. We would also like to acknowledge our ASPIRE stroke champions who continue to raise the level of awareness of Stroke Preparedness: George Washington University Hospital - Kathleen Burger, MD; Sibley Memorial Hospital - Jennifer Abele, MD; Susan Ohnmacht, RN, MS, MSN; Howard University Hospital -Annapurni Jayam Trouth, MD; Medstar Good Samaritan (Baltimore)- David Weisman, DO; University of Maryland - Barney Stern, MD; Johns Hopkins University -Brenda Johnson, MS, CRNP-BC, CCRN, ANVP; Medstar Union Memorial - Ramesh Khurana, MD

Sources of Funding

Supported by the National Institute of Neurological Disorders and Stroke (NINDS) and the National Center on Minority Health and Health Disparities (NCMHD) (U54NS057405).

Footnotes

Disclosures

None

Contributor Information

Bernadette Boden-Albala, Division of Social Epidemiology, Global Institute for Public Health, Department of Neurology Langone Medical Center, Department of Epidemiology, College of Dentistry, New York University, New York, NY.

Dorothy F. Edwards, Departments of Kinesiology and Medicine, University of Wisconsin, Madison, WI.

Shauna St Clair, Department of Neurology and Georgetown Stroke Ctr, Georgetown University Medical Center, Washington, DC.

Jeffrey J Wing, Univ of Michigan, Ann Arbor, MI.

Stephen Fernandez, Medstar Health Res Inst, Hyattsville, MD.

Chris Gibbons, Johns Hopkins Urban Health Inst, Baltimore, MD.

Amie W. Hsia, Department of Neurology and Georgetown Stroke Ctr, Georgetown University Medical Center, Washington, DC; Stroke Center, Medstar Washington Hospital Center, Washington, DC.

Lewis B. Morgenstern, Univ of Michigan, Ann Arbor, MI.

Chelsea S. Kidwell, Department of Neurology and Georgetown Stroke Ctr, Georgetown University Medical Center, Washington, DC; Departments of Neurology and Medical Imaging, University of Arizona College of Medicine, Tucson, AZ.

References

- 1.Sacco RL, Boden-Albala B, Gan R, Chen X, Kargman DE, Shea S, et al. Stroke incidence among white, black, and Hispanic residents of an urban community - The Northern Manhattan Stroke Study. Am J Epidemiol. 1998;147:259–268. doi: 10.1093/oxfordjournals.aje.a009445. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Gross CR, Kase CS, Mohr JP, Cunningham SC, Baker WE. Stroke in South Alabama - Incidence and Diagnostic Features - a Population Based Study. Stroke. 1984;15:249–255. doi: 10.1161/01.str.15.2.249. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Friday G, Lai SM, Alter M, Sobel E, Larue L, Gilperalta A, et al. Stroke in the Lehigh Valley - Racial Ethnic-Differences. Neurology. 1989;39:1165–1168. doi: 10.1212/wnl.39.9.1165. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Broderick J, Brott T, Kothari R, Miller R, Khoury J, Pancioli A, et al. The Greater Cincinnati Northern Kentucky Stroke Study - Preliminary first-ever and total incidence rates of stroke among blacks. Stroke. 1998;29:415–421. doi: 10.1161/01.str.29.2.415. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Ayala CN, Croft JB, Greenlund KJ, Keenan NL, Donehoo RS, Malarcher AM, et al. Sex differences in US mortality rates for stroke and stroke subtypes by race/ethnicity and age, 1995–1998. Stroke. 2002;33:1197–1201. doi: 10.1161/01.str.0000015028.52771.d1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Kothari R, Jauch E, Broderick J, Brott T, Sauerbeck L, Khoury J, et al. Acute stroke: Delays to presentation and emergency department evaluation. Ann Emerg Med. 1999;33:3–8. doi: 10.1016/s0196-0644(99)70431-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Schroeder EB, Rosamond WD, Morris DL, Evenson KR, Hinn AR. Determinants of use of emergency medical services in a population with stroke symptoms - The Second Delay in Accessing Stroke Healthcare (DASH II) Study. Stroke. 2000;31:2591–2596. doi: 10.1161/01.str.31.11.2591. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Billings-Gagliardi S, Mazor KM. Development and validation of the stroke action test. Stroke; a journal of cerebral circulation. 2005;36:1035–1039. doi: 10.1161/01.STR.0000162716.82295.ac. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Moser DK, Alberts MJ, Kimble LP, Alonzo A, Croft JB, Dracup K, et al. Reducing delay in seeking treatment by patients with acute coronary syndrome and stroke - A scientific statement from the American Heart Association Council on Cardiovascular Nursing and Stroke Council. Circulation. 2006;114:168–182. doi: 10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.106.176040. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Johnston SC, Fung LH, Gillum LA, Smith WS, Brass LM, Lichtman JH, et al. Utilization of intravenous tissue-type plasminogen activator for ischemic stroke at academic medical centers - The influence of ethnicity. Stroke. 2001;32:1061–1067. doi: 10.1161/01.str.32.5.1061. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Reed SD, Cramer SC, Blough DK, Meyer K, Jarvik JG. Treatment with tissue plasminogen activator and inpatient mortality rates for patients with ischemic stroke treated in community hospitals. Stroke; a journal of cerebral circulation. 2001;32:1832–1840. doi: 10.1161/01.str.32.8.1832. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Evans A, Duckworth S, Kalra L. Racism and tPA use in African-Americans. Stroke; a journal of cerebral circulation. 2001;32:2439. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Syed M, Khaja F, Rybicki BA, Wulbrecht N, Alam M, Sabbah HN, et al. Effect of delay on racial differences in thrombolysis for acute myocardial infarction. Am Heart J. 2000;140:643–650. doi: 10.1067/mhj.2000.109644. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Epstein AM, Weissman JS, Schneider EC, Gatsonis C, Leape LL, Piana RN. Race and gender disparities in rates of cardiac revascularization - Do they reflect appropriate use of procedures or problems in quality of care? Med Care. 2003;41:1240–1255. doi: 10.1097/01.MLR.0000093423.38746.8C. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Schulman KA. The effect of race and sex on physicians' recommendations for cardiac catheterization. New Engl J Med. 1999;340:618–626. doi: 10.1056/NEJM199902253400806. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.van Ryn M, Fu SS. Paved with good intentions: Do public health and human service providers contribute to racial/ethnic disparities in health? Am J Public Health. 2003;93:248–255. doi: 10.2105/ajph.93.2.248. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Bradley EH, Herrin J, Wang YF, McNamara RL, Webster TR, Magid DJ, et al. Racial and ethnic differences in time to acute reperfusion therapy for patients hospitalized with myocardial infarction. Jama-J Am Med Assoc. 2004;292:1563–1572. doi: 10.1001/jama.292.13.1563. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Boden-Albala B, Quarles LW. Education strategies for stroke prevention. Stroke; a journal of cerebral circulation. 2013;44:S48–S51. doi: 10.1161/STROKEAHA.111.000396. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Kleindorfer D, Schneider A, Kissela BM, Woo D, Khoury J, Alwell K, et al. The effect of race and gender on patterns of rt-PA use within a population. Journal of stroke and cerebrovascular diseases : the official journal of National Stroke Association. 2003;12:217–220. doi: 10.1016/j.jstrokecerebrovasdis.2003.09.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Katzan IL, Hammer MD, Hixson ED, Furlan AJ, Abou-Chebl A, Nadzam DM, et al. Utilization of intravenous tissue plasminogen activator for acute ischemic stroke. Arch Neurol-Chicago. 2004;61:346–350. doi: 10.1001/archneur.61.3.346. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Hsia AW, Edwards DF, Morgenstern LB, Wing JJ, Brown NC, Coles R, et al. Racial disparities in tissue plasminogen activator treatment rate for stroke: a population-based study. Stroke; a journal of cerebral circulation. 2011;42:2217–2221. doi: 10.1161/STROKEAHA.111.613828. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Wall HK, Beagan BM, O'Neill J, Foell KM, Boddie-Willis CL. Addressing stroke signs and symptoms through public education: the Stroke Heroes Act FAST campaign. Preventing chronic disease. 2008;5:A49. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Boden-Albala B, Stillman J, Perez T, Evensen L, Moats H, Wright C, et al. A stroke preparedness RCT in a multi-ethnic cohort: design and methods. Contemporary clinical trials. 2010;31:235–241. doi: 10.1016/j.cct.2010.02.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Boden-Albala B, Carman H, Moran M, Doyle M, Paik MC. Perception of recurrent stroke risk among black, white and Hispanic ischemic stroke and transient ischemic attack survivors: the SWIFT study. Neuroepidemiology. 2011;37:83–87. doi: 10.1159/000329522. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Boden-Albala B, Stillman J, Perez T, Evensen L, Moats H, Wright C, et al. A stroke preparedness RCT in a multi-ethnic cohort: design and methods. Contemp Clin Trials. 2010;31:235–241. doi: 10.1016/j.cct.2010.02.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Bland JM. Sample size in guidelines trials. Family practice. 2000;17(Suppl 1):S17–S20. doi: 10.1093/fampra/17.suppl_1.s17. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Murray DM, Hannan PJ, Wolfinger RD, Baker WL, Dwyer JH. Analysis of data from group-randomized trials with repeat observations on the same groups. Statistics in Medicine. 1998;17:1581–1600. doi: 10.1002/(sici)1097-0258(19980730)17:14<1581::aid-sim864>3.0.co;2-n. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Morris DL, Rosamond W, Madden K, Schultz C, Hamilton S. Prehospital and emergency department delays after acute stroke - The Genentech Stroke Presentation Survey. Stroke. 2000;31:2585–2590. doi: 10.1161/01.str.31.11.2585. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Morgenstern LB, Gonzales NR, Maddox KE, Brown DL, Karim AP, Espinosa N, et al. A randomized, controlled trial to teach middle school children to recognize stroke and call 911: the kids identifying and defeating stroke project. Stroke; a journal of cerebral circulation. 2007;38:2972–2978. doi: 10.1161/STROKEAHA.107.490078. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.