Abstract

Senile amyloid plaques are one of the diagnostic hallmarks of Alzheimer’s disease (AD). However, the severity of clinical symptoms of AD is weakly correlated with the plaque load. AD symptoms severity is reported to be more strongly correlated with the level of soluble amyloid-β (Aβ) assemblies. Formation of soluble Aβ assemblies is stimulated by monomeric Aβ accumulation in the brain, which has been related to its faulty cerebral clearance. Studies tend to focus on the neurotoxicity of specific Aβ species. There are relatively few studies investigating toxic effects of Aβ on the endothelial cells of the blood-brain barrier (BBB). We hypothesized that a soluble Aβ pool more closely resembling the in vivo situation composed of a mixture of Aβ40 monomer and Aβ42 oligomer would exert higher toxicity against hCMEC/D3 cells as an in vitro BBB model than either component alone. We observed that, in addition to a disruptive effect on the endothelial cells integrity due to enhancement of the paracellular permeability of the hCMEC/D3 monolayer, the Aβ mixture significantly decreased monomeric Aβ transport across the cell culture model. Consistent with its effect on Aβ transport, Aβ mixture treatment for 24h resulted in LRP1 down-regulation and RAGE up-regulation in hCMEC/D3 cells. The individual Aβ species separately failed to alter Aβ clearance or the cell-based BBB model integrity. Our study offers, for the first time, evidence that a mixture of soluble Aβ species, at nanomolar concentrations, disrupts endothelial cells integrity and its own transport across an in vitro model of the BBB.

Keywords: Alzheimer’s disease, amyloid-β, blood–brain barrier, clearance

1. Introduction

Alzheimer’s disease (AD) is the most common cause of irreversible dementia among the elderly with a rapidly increasing socioeconomic impact [1]. During the last decade, amyloid- and tau-related neuropathologies were considered as the main underlying causes of neurodegeneration, cognitive decline and memory loss associated with AD [2–3]. Amyloid-β (Aβ) peptides are derived from a minor pathway of proteolytic processing of the amyloid-β precursor protein (APP). In AD, amyloid peptides, mainly Aβ40 and Aβ42, accumulate in the parenchymal tissue and the vasculature of cortical and hippocampal regions of the brain where they assemble and form insoluble plaques [4].

Aβ has multiple different assembly states ranging from monomer to insoluble plaque and all of these states have been identified in the brain of AD patient [5–6]. Two main pools of Aβ have been distinguished in the brain of AD patients, a soluble pool that consists of a mixture of Aβ monomers and soluble oligomers, and an insoluble pool of insoluble oligomers and higher order histologically prominent insoluble Aβ fibrils [7]. Increasing evidence indicates that soluble pool of Aβ is more biologically active than the insoluble Aβ fibrils [8–9]. Moreover, a comparison of pathology with clinical diagnosis of AD brains found a weak correlation between Aβ plaque load and the progression of AD symptoms, in contrast to a better correlation of the soluble pool of Aβ with AD clinical severity [8, 10–11].

The soluble Aβ pool consists of multiple species of Aβ; however, Aβ40 and Aβ42 are the most abundant, readily identifiable, and are considered the most important components contributing to the pathology of AD. Aβ40 is the most abundant Aβ species in the brain of AD patients, however, Aβ42 is the main peptide involved in the soluble oligomers due to its high propensity to aggregate [12]. Moreover, Aβ42 oligomers that are initially formed act as a seed that can accelerate the accumulation of Aβ40, which is present in the brain at concentrations several-fold higher than Aβ42 [6].

In late-onset “sporadic” AD, extensive studies have suggested that reduced clearance of Aβ from the brain across the blood-brain barrier (BBB) to the periphery significantly contributes to its accumulation in the brain [13]. P-glycoprotein (P-gp) and low-density lipoprotein receptor-related protein-1 (LRP1) at the BBB have been reported to play important roles in Aβ clearance from the brain to the blood [14–16]. On the other hand, the receptor for advanced glycation end products (RAGE) mediates influx of Aβ from blood to brain [17]. In addition to clearance via transport across the BBB, monomeric Aβ is subjected to proteolytic degradation by insulin degrading enzyme (IDE) and neprilysin (NEP) that are expressed in different cellular component of the brain including BBB endothelium [18–22]. Previous in vitro and in vivo studies have demonstrated reduced expression of P-gp in brain capillaries treated with Aβ40 or Aβ42 monomers, or Aβ42 oligomers [23–24]; LRP1 and RAGE gene expressions were reduced in the brain of wild type mice treated with human sequence Aβ42 monomers but not with Aβ40 monomers [25]. However, none of these studies investigated the effect of Aβ treatment on its own clearance. To our knowledge, studies investigating the effect of more physiologically and pathologically relevant Aβ peptide composition on the clearance of Aβ monomers across the BBB and its degradation are lacking.

Several pathological alterations in BBB function have been observed in AD patients. Disrupted capillary integrity, loss of controlled molecular transport, and uncontrolled solute exchange are among these pathological alterations [26]. Furthermore, available studies have reported loss of tight junction proteins necessary to restrict paracellular transport between blood and brain, which contributes to the pathogenesis of AD [27]. Accumulating evidence suggests that Aβ has disruptive effects on the integrity of the BBB [24, 28–30]. In addition, about 80–90% of AD patients develop cerebral amyloid angiopathy (CAA) that is characterized by Aβ accumulation in brain blood vessel walls and associated with compromised BBB function [31]. Available studies have shown that increased levels of soluble Aβ affect integrity of BBB endothelial cells by reducing the expression and re-localization of tight junction proteins [28–30]. However, most of these studies, which investigated the toxicity of specific species of soluble Aβ isoforms against BBB endothelium used high non-physiological or even pathological Aβ concentrations. Thus, evaluating the effect of Aβ on BBB endothelial cells integrity in the presence of more than one Aβ species at nanomolar concentrations provides a more biologically relevant approach to clarify the pathological changes that are associated with Aβ in AD. Accordingly, in this study, we hypothesized that Aβ mixture consisting of nanomolar levels of both Aβ40 monomer and Aβ42 oligomer exerts greater toxicity against endothelial cells of the BBB than the individual species. To test this hypothesis, the human brain endothelial cell line hCMEC/D3, as an in vitro cell-based BBB model, was used to study the effect of Aβ mixture on the transport of Aβ monomer and Aβ toxic effect on BBB endothelial cells.

2. Methodology

2.1. Preparation and characterization of synthetic amyloid-β mixture

Solutions of synthetic Aβ40 and Aβ42 peptides (AnaSpec, Inc.; CA) were prepared by suspending in 1, 1, 1, 3, 3, 3-hexafluoro-2-propanol (HFIP) (Sigma-Aldrich, MO) each at a concentration of 1 mM and incubated for 1 h at room temperature for complete solubilization. Aβ solutions were aliquoted, HFIP was evaporated overnight and the peptides stored at −20°C as an HFIP film. For Aβ40 monomer, HFIP film was dissolved in media and used immediately for cell treatment or for preparation of Aβ mixture as described below. Aβ42 oligomer was prepared as described previously [32]. Briefly, aliquoted Aβ42 peptide HFIP-film was suspended in anhydrous DMSO (Sigma-Aldrich, MO) to a final concentration of 5 mM, vortex mixed for 1 min. DMSO solution of Aβ42 was diluted with phenol red-free F-12 cell culture media (Gibco, NY) to a concentration of 100 μM, vortexed for 1 min and incubated at 4°C for 24 h. At the end of incubation period, the Aβ42 oligomer solution was centrifuged at 14,000 rpm, 4°C for 10 min. The supernatant was fractionated at room temperature using size exclusion chromatography (SEC) to separate oligomers from monomers. Two hundred microliters of the supernatant was injected onto a sephadex G-75 column and eluted with 15 ml media at flow rate of 0.5 ml/min. Twenty-four fractions of 0.5 ml were collected after the elution of the first 3 ml. Aβ42 oligomer in each fraction was assessed by sandwich ELISA as described previously [33]. 6E10 (aa. 3–8 human Aβ sequence) monoclonal antibody (Covance Research Products, MA) was coated at 5 μg/ml concentration (100 ng/well) on an Maxisorp ELISA plate (Thermo, NY) to capture Aβ42 oligomer. Detection was achieved with HRP-conjugated 6E10 antibody at 1 μg/ml (Covance Research Products, MA). Fractions that contained Aβ42 oligomers were collected and used immediately after proper dilution to the required concentration for cell treatment or for preparation of Aβ mixtures. Aβ mixtures were prepared by mixing Aβ40 monomers at concentrations 0, 50, 100 or 250 nM and Aβ42 oligomers at concentrations 0, 25, 50, or 100 nM. Treatment concentrations of Aβ40 monomer, Aβ42 oligomer and Aβ mixtures were measured using western blot analyses. Forty microliters of the treatment solution and Aβ standards (500, 250, 100, 50, 25 nM) were resolved on a 16% Bis-Tris gel in 3-(N-morpholino) propanesulfonic acid buffer system and transferred onto a 0.45 μm pore size nitrocellulose membrane (Bio-Rad, CA). The membrane was blocked with 5% BSA in TBS buffer (20 mM Tris-HCl, 150 mM NaCl pH 7.5) for 1 h and incubated with 6E10 antibody (1:1000 dilution in TBS buffer containing 5 % BSA and 0.05% Tween-20) for 3 h at room temperature. For antigen detection, the membranes were washed and incubated with HRP-labeled secondary anti-mouse (Santa Cruz, TX) at 1:5000 dilution. The bands were visualized using a SuperSignal West Femto detection kit (Thermo Scientific, IL). Quantitative analysis of the immunoreactive bands was performed using a GeneSnap luminescent image analyzer (Scientific Resources Southwest, TX), and band intensities were measured by densitometry analysis. Band intensities were plotted against concentration of standards and the concentration of treatment solution were interpolated from the resulting calibration curve. For all experiments, Aβ42 oligomers and Aβ mixtures were prepared in the same way described above using Aβ standards purchased from the same manufacturer (AnaSpec, Inc.).

2.2. Cell Culture

Human brain endothelial cells (hCMEC/D3; kindly provided by Dr. P.O. Couraud, Institute Cochin, Paris, France), passage 25–35, were used as a representative model for human BBB. hCMEC/D3 cells were cultured in EBM-2 medium (Lonza, MD) supplemented with 1 ng/ml human basic fibroblast growth factor (Sigma-Aldrich, MO), 10 mM HEPES, 1% chemically defined lipid concentrate (Gibco, NY), 5 μg/ml ascorbic acid, 1.4 μM hydrocortisone, 1% penicillin-streptomycin and 5% of heat-inactivated FBS gold (GE Healthcare Life Sciences, PA). Cultures were maintained in a humidified atmosphere (5%CO2/95% air) at 37°C and media was changed every other day.

2.3. Toxicity of synthetic amyloid-β mixture on hCMEC/D3 cells

MTT cytotoxicity assay was performed to select sub-toxic concentrations of Aβ preparations. hCMEC/D3 cells were seeded onto 24-well plate and maintained as described above. At 70% confluence, cells were treated for 24 h with Aβ40 monomer, Aβ42 oligomers or mixtures of Aβ40 monomer and Aβ42 oligomers at different concentrations. Aβ40 monomer concentration dependent toxicity against hCMEC/D3 cells were studied at the concentrations 0, 50, 100 and 250 nM in the presence or absence of 50 nM Aβ42 oligomers. For Aβ42 oligomers concentration dependent study, cells were treated with 0, 25, 50 and 100 nM Aβ42 oligomers with or without 100 nM Aβ40 monomer. MTT cytotoxicity assays (Trevigen, MD) were performed at the end of incubation period with Aβ preparations as described previously [34].

2.4. Effect of synthetic amyloid-β mixtures on hCMEC/D3 cells monolayer integrity

The barrier function integrity of hCMEC/D3 was evaluated by measuring 14C-inulin ([carboxyl-14C]-inulin, M.W.: 5,000 Da; American Radiolabeled Chemicals, MO) permeation. Inulin is a marker for paracellular transport across a cell monolayer where its transendothelial transport across intact hCMEC/D3 monolayer is greatly restricted [35]. To prepare hCMEC/D3 cell monolayers, transwell polyester membrane inserts, 6.5 mm diameter with 0.4 μm pores (Corning, NY), were coated with rat tail collagen-IV (150 μg/ml) for 90 min at 37°C. Cells were plated onto coated inserts at a seeding density of 50,000 cells/cm2, medium was changed every other day. Trans-epithelial electrical resistance (TEER) was measured using an EVOM epithelial volt-ohmmeter with STX2 electrodes (World Precision Instruments, FL). hCMEC/D3 cell monolayers were used for Aβ40 transport and inulin permeation experiments on day 6 of culture [21, 35]. On day 6, the TEER value was measured and ranged from 35–40 Ω.cm2 that is consistent with previously reported values for this cell line [35]. Cells were treated for 24 h treatment with increasing concentration of monomeric Aβ40 in the presence or absence of 50 nM Aβ42 oligomer or increasing concentration of Aβ42 oligomer with or without 100 nM monomeric Aβ40. At the end of treatment, apical to basolateral 14C-inulin permeation coefficient was measured. For inulin permeation, 200 μl of fresh media containing 0.05 mM 14C-inulin was added to the apical chamber and 800 μl of fresh media was added to the basolateral chamber. Cells were maintained in a humidified atmosphere (5%CO2/95% air) at 37°C for the time course of the permeability experiment (up to 2 h). Fifty microliter aliquots from the basolateral chamber were collected at 15, 30, 45, 60, 90, 120 min and replaced with 50 μl of fresh media to keep the volume of basolateral chamber unchanged and maintain constant osmotic pressure. After mixing samples with 5 ml of scintillation cocktail, 14C-inulin dpm was measured using a Wallac 1414 WinSpectral Liquid Scintillation Counter (PerkinElmer, MA). Concentrations of 14C-inulin in basolateral side (in dpm/ml) were plotted versus time. 14C-inulin permeation coefficient (Papp in cm/sec) was calculated from the following equation [36]:

| (Eq. 1) |

where ΔQ/Δt is the linear appearance rate of the 14C-inulin in the basolateral chamber, A is the surface area of the cell monolayer (0.33 cm2) and Co is the initial concentration of 14C-inulin (dpm/ml).

2.5. Effect of synthetic amyloid-β mixtures on 125I-Aβ40 transport across hCMEC/D3 cell monolayer

The transport of 125I-Aβ40 (PerkinElmer, MA) and 14C-inulin, as a marker for paracellular diffusion, were measured across hCMEC/D3 monolayer after treatment with different Aβ preparations. hCMEC/D3 cell monolayers were seeded and maintained in transwell chambers as described above. One day before conducting transport experiments, cells were treated with increasing concentration of monomeric Aβ40 in the presence or absence of 50 nM Aβ42 oligomer or increasing concentration of Aβ42 oligomer with or without 100 nM monomeric Aβ40. Basolateral to apical (B→A) transport studies were then performed as described previously [21]. In brief, the transport study was initiated by removing media that contained Aβ mixture and addition of 800 μl of fresh media containing 0.1 nM 125I-Aβ40 and 0.05 mM 14C-inulin to the basolateral compartment. At the end of incubation period (6 h), media from both compartments and cells were separately collected for 125I-Aβ40 analysis and 14C-inulin measurement [21]. The transport quotients of B→A (125I-Aβ40 CQB → A) transport were calculated using the following equation [37]:

| (Eq. 2) |

where 125I-Aβ40 total is the total intact cpm in the apical and basolateral compartments, as well as cpm remaining in cells. 14C-inulin total is the total inulin dpm in the apical and basolateral compartments. Trichloroacetic acid (TCA) precipitation [38] was used to measure the amount of intact and degraded 125I-Aβ40. Total 125I-Aβ40 was determined by counting sample radioactivity. Degraded 125I-Aβ40 was measured in the supernatant following precipitation with TCA. To measure degraded 125I-Aβ40, one volume of TCA (20%) was added to the sample, and then samples were vortex mixed, incubated in ice for 30 min, and then centrifuged at 14,000 rpm (4°C) for 30 min. Following centrifugation, the gamma radioactivity of the TCA supernatant containing degraded peptide was measured using a Wallac 1470 Wizard Gamma Counter (PerkinElmer, MA). The intact fraction was calculated by subtracting degraded 125I-Aβ40 from total 125I-Aβ40.

2.6. Expression of P-gp, LRP1, RAGE, IDE and NEP in hCMEC/D3 cells following amyloid-β treatments

Cells were seeded in 100 mm cell culture dishes (Corning, NY) at a density of 1 × 106 cells per dish. The cells were allowed to grow to 70% confluency before treatment with different Aβ preparations in a humidified atmosphere (5%CO2/95% air) at 37°C. Cells were treated for 24 h with control media, 100 nM monomeric Aβ40, 50 nM Aβ42 oligomers or mixture of 100 nM monomeric Aβ40 and 50 nM Aβ42 oligomers. At the end of treatment period, RIPA buffer containing complete mammalian protease inhibitor mixture (Sigma-Aldrich, MO) was used to dissolve cells. For western blot analysis of P-gp, LRP1, RAGE, IDE and NEP in hCMEC/D3 cells after Aβ treatment, 25 μg of cellular protein was resolved on 8% Bis-tris gels in 3-(N-morpholino) propanesulfonic acid buffer system and electrotransferred onto 0.45 μm nitrocellulose membrane. Membranes were blocked with 2% BSA and incubated overnight with monoclonal antibodies for P-gp (C-219; Covance Research Products, MA), LRP1 (Calbiochem, NJ), RAGE (Santa Cruz, TX), IDE (Santa Cruz, TX), NEP (Calbiochem, NJ) or GAPDH (Santa Cruz, TX) at dilutions 1:200, 1:1500, 1:200, 1:200, 1:100 and 1:3000, respectively. For antigen detection, the membranes were washed and incubated with HRP-labeled secondary IgG antibody for P-gp, RAGE, NEP and GAPDH (anti-mouse), LRP1 (anti-rabbit) and IDE (anti-goat) (Santa Cruz, TX) at 1:5000 dilution. The bands were visualized and quantified as described above. Three independent Western blotting analyses were carried out for each treatment group.

2.7. Statistical analysis

Unless otherwise indicated, the data were expressed as mean ± SEM. The experimental results were statistically analyzed for significant difference using two-tailed Student’s t-test for 2 groups, and one-way analysis of variance (ANOVA) for more than two group analysis. Values of P<0.05 were considered statistically significant.

3. Results

3.1. Characterization of Aβ preparations

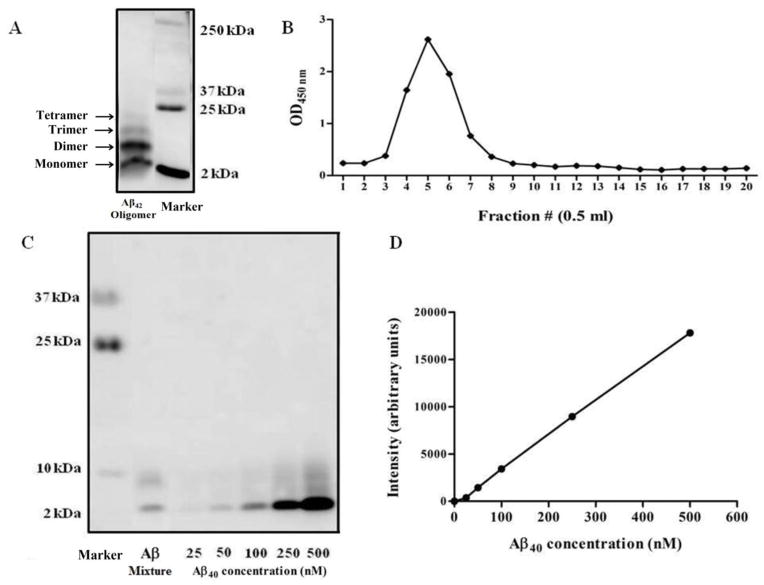

To study the toxicity of Aβ species on hCMEC/D3 cells, Aβ40 monomer and Aβ42 oligomers were first prepared and characterized. These Aβ species were selected because Aβ40 is the most abundant Aβ peptide in the brains of AD patients, and soluble Aβ42 oligomers are the initial seeds for forming higher order assemblies, and they have proved to have high toxicity [6]. Figures 1A and C confirmed Aβ42 oligomers formation; oligomers include SDS-stable dimer, trimer, tetramer; no large protofibrils were detected. Figure 1B shows a representative SEC profile where Aβ42 oligomers, as measured by a total oligomer-specific ELISA, were detected in fractions 4–8. Subsequently, immunoblotting assay was utilized to estimate the concentrations of both, the monomer and oligomers. The concentrations of all Aβ species were calculated based on a calibration curve of Aβ monomer standards (Fig. 1C and D).

Figure 1.

Preparation of Aβ mixtures. Starting from synthetic Aβ42 monomer, a stable oligomer was prepared and fractionated by SEC. (A) A representative blot of crude Aβ42 oligomers. (B) SEC profile of Aβ42 oligomers as measured by an oligomer-specific ELISA. Fractions 4–8 containing oligomers were collected for further analysis. (C) A representative western blot analysis for purified Aβ42 oligomer, Aβ mixture and a calibration curve of monomeric synthetic Aβ40 standards to adjust the concentration of each species for cell treatment. (D) Densitometry versus concentration calibration curve that was used to quantify Aβ concentrations.

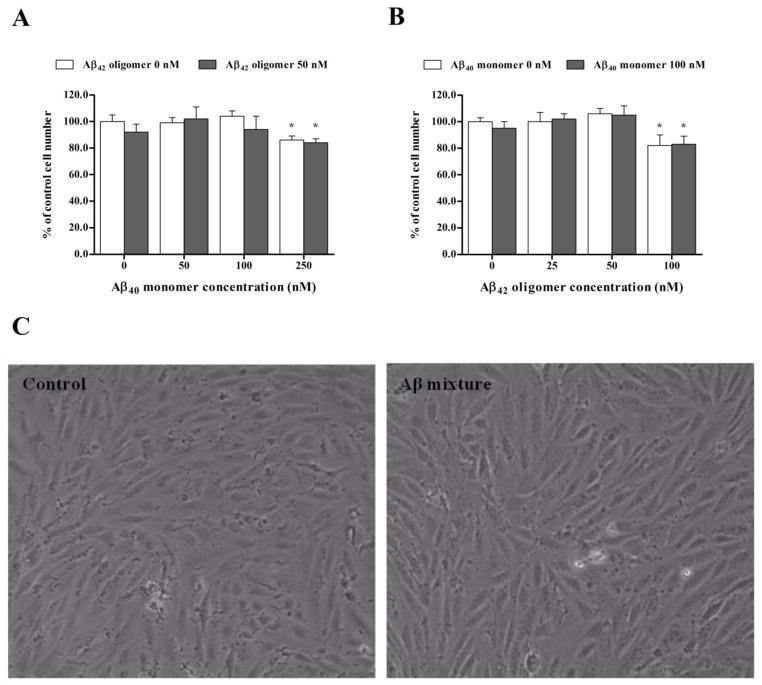

3.2. Assessing toxicity of Aβ preparations against hCMEC/D3

Cell viability assays were performed initially to confirm that Aβ preparations used in the treatment of hCMEC/D3 cells were not toxic at the applied concentrations after 24 h of treatment. MTT cytotoxicity assay with hCMEC/D3 cells demonstrated that cell treatment did not affect the viability of hCMEC/D3 after 24 h exposure to Aβ preparations except at high concentrations of Aβ40 monomers and Aβ42 oligomers added separately or as a mixture. MTT assay results from cells treated with Aβ40 monomers at 50 and 100 nM, Aβ42 oligomers at 25 and 50 nM, or mixtures of these concentrations were comparable to control treated cells (Fig. 2A and B). However, MTT assay showed that the viability of hCMEC/D3 decreased by 14–17% following treatment with 250 nM Aβ40 monomer, mixture of 250 nM Aβ40 monomer and 50 nM Aβ42 oligomer, 100 nM Aβ42 oligomer and mixture of 100 nM Aβ42 oligomer and 100 nM Aβ40 monomer (Fig. 2A and B). Thus, for permeation studies of inulin and Aβ, high concentrations that induced toxicity were excluded and only sub-toxic concentrations were used for cells treatment. Figure 2C demonstrates absence of morphological changes on hCMEC/D3 cells after 24 h treatment with Aβ mixture consisting of 100 nM Aβ40 monomers and 50 nM Aβ42 oligomers when compared to control.

Figure 2.

Cell toxicity assays after treatment with Aβ preparations. (A) Concentration dependent MTT cytotoxcity assay of 0, 50, 100 and 250 nM of monomeric Aβ40 with or without 50 nM Aβ42 oligomer. (B) Concentration dependent MTT cytotoxcity assay of 0, 25, 50 and 100 nM of Aβ42 oligomer with or without 100 nM Aβ40 monomer. Significant reductions in cell viability as measured by MTT reduction to formazan were observed only after 24 h treatment with 250 nM monomeric Aβ40, 100 nM Aβ42 oligomer and their corresponding mixtures. (C) Microscopic images of cells after exposure to control media or Aβ mixture for 24 h. The data are expressed as mean ± SEM of n = 3 independent experiments.

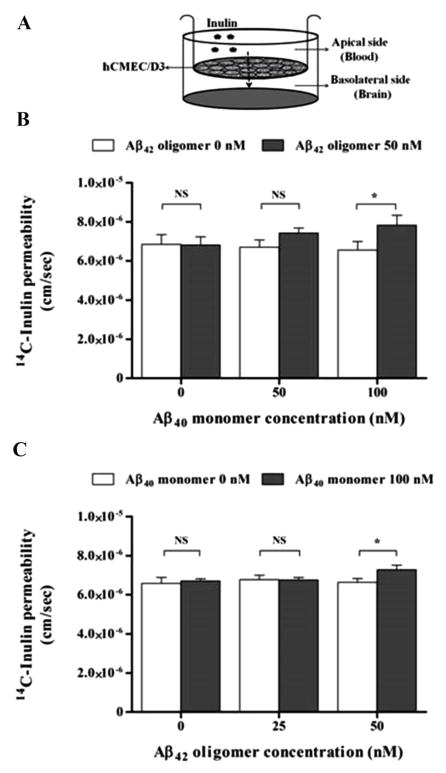

3.3. Treatment of hCMEC/D3 cells monolayer with Aβ mixture increases paracellular permeability

The integrity of the barrier formed by hCMEC/D3 cells grown on inserts after 24 h exposure to Aβ preparations was assessed by measuring permeation of 14C-inulin across the cell monolayer. After 24 h treatment with 0, 50 and 100 nM Aβ40 monomer in the presence or absence of 25 or 50 nM Aβ42 oligomer, only Aβ mixture of 100 nM Aβ40 monomer and 50 nM Aβ42 oligomer disrupted the monolayer integrity and significantly increased apical to basolateral permeation of 14C-inulin across hCMEC/D3 by 11–15% compared to control (p<0.05; Fig. 3A and B). On the other hand, treatments with Aβ species separately, or mixtures at 50 nM each or 100 monomer and 25 oligomer failed to change inulin permeation (Fig. 3A and B).

Figure 3.

Effect of Aβ preparations on the integrity of an hCMEC/D3 monolayer model of the BBB endothelium. Apical to basolateral 14C-inulin permeation across the hCMEC/D3 cell monolayer was monitored for 2 h after 24 h treatment with different Aβ preparations at sub-toxic nanomolar concentrations. (A) Schematic presentation of hCMEC/D3 monolayer shows the direction of inulin permeation when added to the apical side. (B) Concentration dependent studies on the effect of Aβ40 monomer with or without 50 nM Aβ42 oligomer on inulin permeation, and (C) Concentration dependent studies on the effect of Aβ42 oligomer with or without 100 nM Aβ40 monomer on inulin permeation. 14C-inulin permeaion in the apical to basolateral direction was significantly enhanced after treatment with Aβ mixture of 100 nM Aβ40 monomer and 50 nM Aβ40 oligomer indicating the disruptive effect of this Aβ mixture on the integrity of the hCMEC/D3 cells. Data represent mean ± SEM from three independent experiments, * P<0.05.

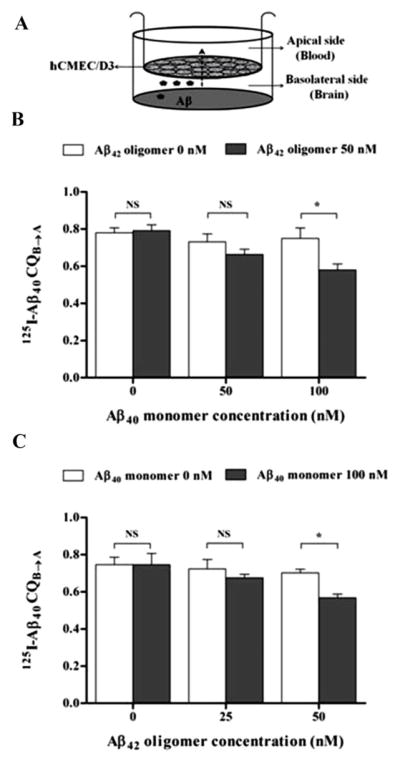

3.4. Treatment with Aβ mixture decreases 125I-Aβ40 transport across hCMEC/D3 cell monolayer

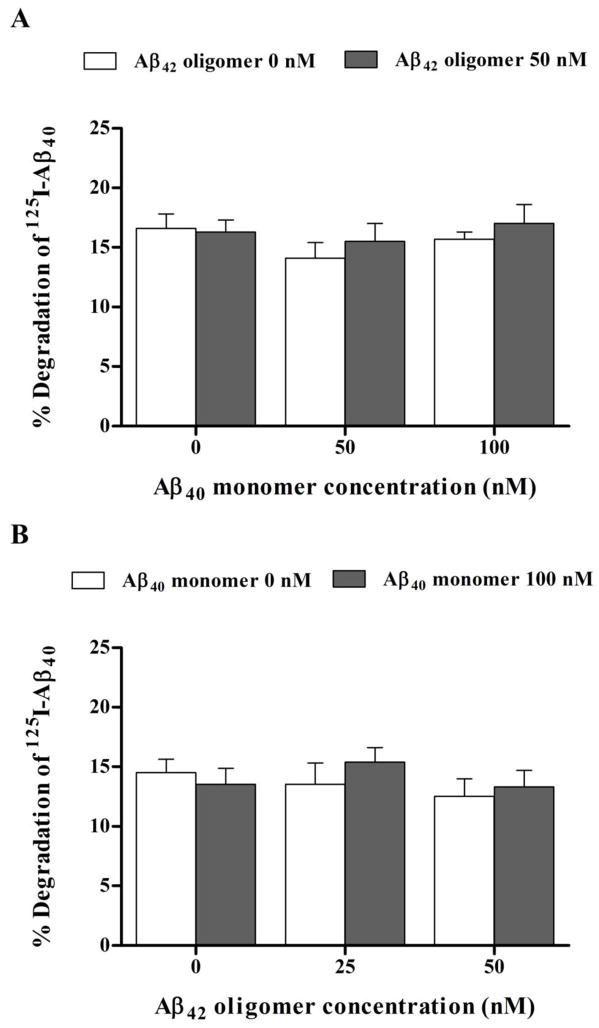

Twenty-four hour treatment of hCMEC/D3 cells monolayer with 100 nM Aβ40 monomer or 50 nM Aβ42 oligomer added separately to the cells failed to alter the transport of 125I-Aβ40 from basolateral to apical side (representative for brain to blood clearance). However, significant reduction in 125I-Aβ40 transport from basolateral to apical side (p<0.05) was only observed following exposure of hCMEC/D3 cells to a mixture of 100 nM Aβ40 monomer and 50 nM Aβ42 oligomer (Fig. 4). In particular, this reduction in Aβ40 transport quotient was a result of decreased transport of Aβ40 across the hCMEC/D3 cells (Supplementary Fig. 1). Transport studies on monomeric 125I-Aβ40 for 12 h across hCMEC/D3 cells monolayer showed a significant reduction in 125I-Aβ40 transport quotients (CQB → A) by 20–25% across cells treated with 100 nM Aβ40 monomer and 50 nM Aβ42 oligomer mixture; while a reduction trend in 125I-Aβ40 CQB → A was observed with other mixtures investigated at different combined concentrations, this reduction was not statistically significant when compared to control treatment (Fig. 4). Besides, treatment with all Aβ preparations for 24 h had no effect on 125I-Aβ40 degradation as measured by TCA assay. The percent degradation of 125I-Aβ40 in the media of hCMEC/D3 were similar for all treatments with degradation % values in the range of 15.7–17% (Fig. 5).

Figure 4.

Transport of 125I-Aβ40 across hCMEC/D3 cell monolayer after exposure to Aβ preparations. (A) Schematic presentation of hCMEC/D3 monolayer shows the direction of transport of 125I-Aβ40 added to the basolateral side. (B) Transport quotient CQB→A of 125I-Aβ40 across hCMEC/D3 monolayer treated for 24 h with increasing concentrations of Aβ40 monomer with or without 50 nM Aβ42 oligomers, and (C) Transport quotient CQB→A of 125I-Aβ40 across hCMEC/D3 monolayer treated for 24 h with increasing concentrations of Aβ42 oligomers with or without 100 nM Aβ40 monomer. While Aβ mixture of 100 nM Aβ40 monomer and 50 nM Aβ42 oligomer significantly reduced CQB→A of 125I-Aβ40, other Aβ preparations did not affect 125I-Aβ40 transport. Data represent mean ± SEM from three independent experiments; * P<0.05.

Figure 5.

Degradation of 125I-Aβ40 by hCMEC/D3 cell monolayer after exposure to Aβ preparations. (A) % degradation of 125I-Aβ40 by hCMEC/D3 monolayer treated for 24 h with increasing concentrations of Aβ40 monomer with or without 50 nM Aβ42 oligomers, and (B) % degradation of 125I-Aβ40 by hCMEC/D3 monolayer treated for 24 h with increasing concentrations of Aβ42 with or without 100 nM Aβ40 monomer. None of Aβ preparations altered % degradation of 125I-Aβ40 after 24 h treatment. Data represent mean ± SEM from three independent experiments; * P<0.05.

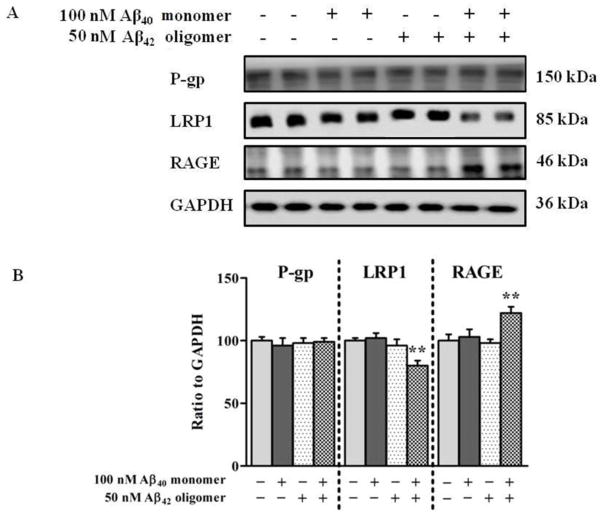

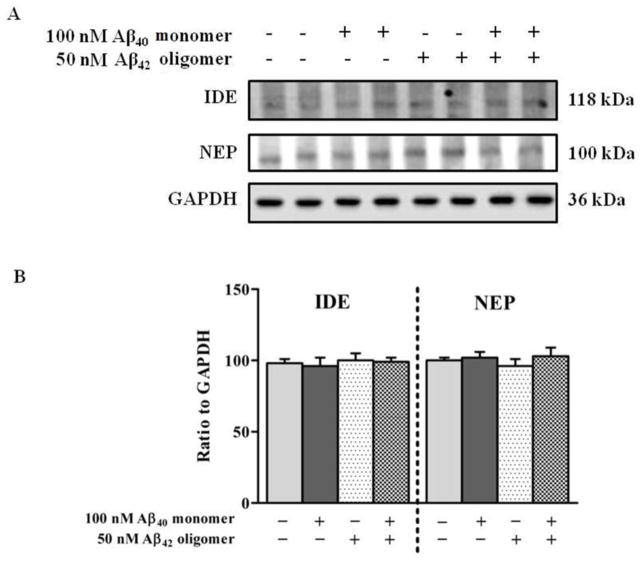

3.5. Aβ mixture differentially affects the expression of LRP1 and RAGE in hCMEC/D3 cells but not P-gp and Aβ degrading enzymes

Given the important role of P-gp and LRP1 in the transport of Aβ across the BBB, we determined the effect of Aβ mixture (100 nM Aβ40 monomers and 50 nM Aβ42 oligomers) on the expression of these proteins in hCMEC/D3 cells in order to explain the reduced transport of Aβ40 across the monolayer. The results of western blot analysis following 24 h treatment demonstrated that the expression of P-gp in hCMEC/D3 was not altered by Aβ40 monomers, Aβ42 oligomers, or Aβ mixture treatments (Fig. 6A and B). However, treatment with Aβ mixture significantly decreased the expression of LRP1 (P<0.01). This reduction was not observed with Aβ40 monomers or Aβ42 oligomers (Fig. 6A). Densitometry analysis of western blot bands showed a significant 20% reduction in the expression of LRP1 after treatment with Aβ mixture (Figure 6B). On the other hand, RAGE showed a significant 23% increase in protein level after exposure to Aβ mixture for 24 h, yet cells treated with Aβ40 monomers or Aβ42 oligomers did not show any significant alterations in RAGE protein expression (Fig. 6A and B). Consistent with the results of TCA degradation assay, there were no significant changes observed in the expression of the Aβ degrading enzymes IDE and NEP following 24 h exposure to Aβ40 monomers, Aβ42 oligomers and Aβ mixture (Fig. 7A and B).

Figure 6.

Expression of P-gp, LRP1 and RAGE in hCMEC/D3 cells. (A) Western blot analysis of P-gp, LRP1, and RAGE protein expressions in hCMEC/D3 cells after 24 h exposure to control media, 100 nM monomeric Aβ40, 50 nM Aβ42 oligomers, or Aβ mixture of both. (B) Densitometry analyses showed similar expression level of P-gp in all treatment groups, significantly higher RAGE expression and lower LRP1 expression in hCMEC/D3 cells treated with Aβ mixture. Data represent mean ± SEM from three independent experiments; ** P<0.01.

Figure 7.

(A) Western blot analysis of IDE and NEP protein expression in hCMEC/D3 cells after 24 h exposure to control media, 100 nM monomeric Aβ40, 50 nM Aβ42 oligomers or Aβ mixture of both. (B) Corresponding densitometry analysis showed that none of the Aβ preparations altered the expression of IDE or NEP. Data represent mean ± SEM from three independent experiments.

4. Discussion

In AD patients, Aβ peptides coexist in the brain as a heterogeneous mixture of different Aβ species with different sizes, solubility and conformational structures [7]. Although qualitative as well as quantitative changes in Aβ species have a central role in the pathogenesis of AD, specific key changes that contribute significantly to the development and progression of AD are still a matter of debate [5, 39]. Available studies indicate that soluble Aβ pool has high toxicity against neurons and is highly correlated with the severity of AD [8, 11]. Some studies have identified specific individual species in the Aβ soluble pool that exerts significant neuronal toxicity, however, the significance of these results remains unclear. It is difficult to attribute Aβ toxicity to a single species because: 1) it is difficult to prepare highly pure and stable specific Aβ assemblies (in vitro or in vivo) due to the unusual behavior of Aβ peptides in the analytical procedures [40], 2) there is a lack of standardization of concentrations or purification methods, and 3) the more important issue is that in the brains of AD patients multiple species of Aβ exist and are expected to change during aging and the course of disease [41–43]. In addition, physiological, or at most pathological, concentrations of specific Aβ species are likely to be the most relevant to the biological situation. Otherwise, it is difficult to compare the intrinsic toxicity of Aβ mixtures to that of specific species. Instead, studies investigating the effect of a mixture of Aβ species (at least the known, abundant and pathogenic ones) at physiological and pathological level are more likely to be informative of the in vivo condition [5].

The intent of this study was to in vitro investigate the effect of different preparations of Aβ on BBB endothelial cells integrity and Aβ40 clearance using hCMEC/D3 cell monolayer as a representative model for the BBB. Brain endothelial cells, astrocytes and pericytes are involved in normal function of BBB [44]. While the astrocytes, pericytes and basement membrane play important role in regulating BBB function, only the capillary endothelium forms the physical barrier separating brain from blood and control barrier functions of the BBB [44]. Although, this model is an in vitro model, it expresses many BBB-specific properties including stringent restriction of paracellular diffusion of large molecules [35, 45]. Moreover, permeability coefficients of hCMEC/D3 cell monolayer were well correlated with in vivo permeability coefficients making this cell line a useful model to study BBB barrier functions [35].

Total Aβ40 has been detected in the brains of AD patients at a level that is 10 times higher than the level of Aβ42. However, the pathological levels of Aβ40 monomer and Aβ42 oligomers in Aβ soluble pool were 100 nM and in the range of 10 to 100 nM for Aβ40 monomer and Aβ42 oligomers, respectively [33, 46]. Therefore, for the purpose of our study, we used Aβ40 monomer and Aβ42 oligomers at previously identified pathologically relevant concentrations at 100 nM and in the range of 10 to 100 nM for Aβ40 monomer and Aβ42 oligomers, respectively.

MTT toxicity studies were initially performed to exclude toxic concentrations of Aβ species when added separately or as mixtures. This is important in order to evaluate the effect of non-toxic concentrations on hCMEC/D3 monolayer integrity as a cell-based BBB model. Thus, all subsequent permeability and active transport studies of Aβ40 were conducted at concentrations ≤ 100 nM Aβ40 monomer and/or ≤ 50 nM Aβ42 oligomers.

Our results demonstrated an effect of the soluble Aβ pool, at nanomolar levels, on the integrity of the hCMEC/D3 model of the BBB assessed by inulin permeation. While several studies have described the disruptive effect of Aβ40 oligomers or Aβ monomers (40 or 42) on BBB permeability [24, 29–30, 47], the single species of Aβ required high micromolar concentrations to exert such toxic effect. Unlike these studies, in the current investigation only Aβ mixture that contains both Aβ40 monomers and Aβ42 oligomers, both in nanomolar concentrations, was able to disrupt the hCMEC/D3 monolayer integrity following 24 h treatment, while at the examined concentrations of individual Aβ40 monomers or Aβ42 oligomers had no effect on the monolayer integrity. This finding suggested that Aβ mixture disrupts the function of tight junction proteins, thereby enhancing paracellular permeation across the hCMEC/D3-BBB model. Previous studies showed that treatment of brain endothelial cells with Aβ40 monomers, Aβ42 monomers or Aβ40 oligomers required high micromolar concentrations to decrease expression of tight junction proteins, re-localize tight junction proteins from the plasma membrane, and enhance paracellular permeation of the culture monolayer [29–30]. The mix of Aβ40 monomers and Aβ42 oligomers at nanomolar concentrations may provoke a more pronounced effect on tight junction protein expression and localization than the individual forms, resulting in a leaky BBB that is unable to provide maximal protection of the brain against circulating neurotoxins.

In spite of leaky hCMEC/D3 monolayer as a result of Aβ mixture treatment, the transport of 125I-Aβ40 was restricted and significantly decreased following the treatment, suggesting Aβ to disrupt its own clearance machinery. This finding confirms Aβ clearance as an active process mediated by transport proteins, and is consistent with studies reporting association between the brain load of Aβ and its disposition [48]. This reduction in the transport of 125I-Aβ40 following Aβ mixture treatment was accompanied by differential effects on the expression of P-gp, IDE and NEP, LRP1, and RAGE in hCMEC/D3 cells. While cells treatment with Aβ mixture for 24 h had no effect on P-gp, IDE and NEP expressions, LRP1 and RAGE expressions were significantly decreased and increased, respectively. P-gp has been reported to efflux Aβ across BBB toward the blood [14]. Several in vivo and in vitro studies [23–25] have shown reduction in P-gp expression following treatment with Aβ monomer or oligomers; however, in the current study this effect was not observed. This discrepancy could be related to differences in experimental protocols used including Aβ concentrations (nanomolar vs micromolar levels) and/or treatment times (24 h vs longer treatment time up to 96 h).

LRP1, a member of the LDL family receptor, is highly expressed at the abluminal side of the brain endothelial cells. It mediates transport of Aβ from the brain to the blood and its expression has been reported to decrease with aging and in patients with AD [38]. Findings from the current study demonstrated that treatment with Aβ mixture down-regulated LRP1 expression in hCMEC/D3 cells, which is consistent with previously reported results following in vivo administration of 100 μg Aβ42 monomers over 26 h that caused a significant reduction in LRP1 expression in brain tissue of FVB wild type mice [25], however with more realistic and relevant concentrations provided by our study. In contrast to LRP1, Aβ mixture up-regulated the cellular expression of RAGE, which is consistent with a pattern observed in AD patients’ brains [17]. While the effect of Aβ mixture on LRP1 and RAGE was obvious 24 h following treatment, the effect of the individual Aβ preparations on LRP1 and RAGE, or on P-gp, IDE, and NEP would be expected to occur following a longer exposure time. Our results suggest that LRP1 and RAGE are more sensitive than P-gp, IDE, and NEP to Aβ changes in the brain. Given the role of LRP1 and RAGE in efflux and influx, respectively, of Aβ across BBB endothelium, changes in their expression would be expected to alter Aβ transport across the BBB.

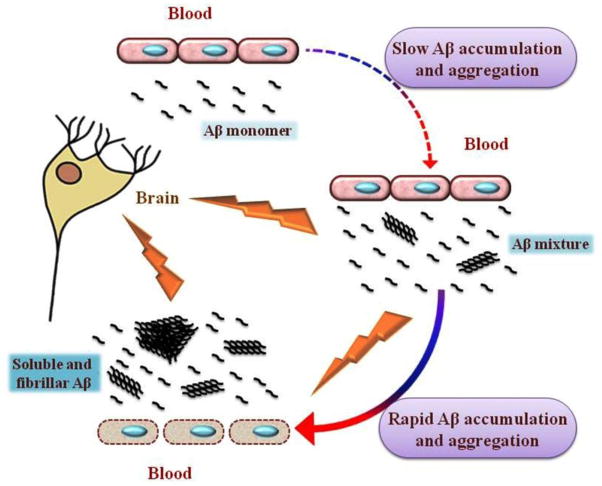

Collectively, our in vitro findings, in addition to previous in vitro and in vivo studies, suggest that faulty clearance of Aβ may start as a slow cascade of monomeric Aβ accumulation and aggregation that result in the formation of a soluble Aβ pool (Aβ mixture). Aβ mixture possesses greater disruption effect on the integrity and functionality of the BBB endothelium compared to either species alone, and enhances rapid accumulation of Aβ in the brain, which inturn could accelerate the pathogenesis of CAA and AD (Figure 8).

Figure 8.

Schematic presentation for a model describing toxic effect of soluble Aβ pool against BBB endothelial cells. Faulty clearance of monomeric Aβ results in its brain accumulation. Accumulated Aβ initiates a cascade of Aβ aggregation to form soluble aggregates of different sizes and types. In addition to their intrinsic neurotoxicity, soluble Aβ aggregates act synergistically with monomeric Aβ40 in the form of Aβ mixture to disrupt BBB endothelial cells and enhance more Aβ accumulation by halting its clearance across BBB. This accelerates the formation of a wide range of soluble and insoluble Aβ assemblies enhancing the development of CAA and AD.

5. Conclusion

Study of a soluble Aβ pool containing a mixture of monomeric and oligomeric Aβ peptide provides a physiologically relevant way to probe the pathogenesis of AD. While previous in vitro and in vivo studies investigated the toxicity of specific Aβ species on the BBB, here, we provide for the first time evidence that a mixture of Aβ possess a greater disruptive effect over and above that of individual Aβ species on the integrity and function of hCMEC/D3 cells as an in vitro model of BBB. This concept may also apply to other biological effects of Aβ.

Supplementary Material

Highlights.

Aβ mixture has great disruption effect on functionality of BBB endothelium model.

Aβ mixture disrupts BBB endothelium model integrity rendering it leaky at low nM levels.

Aβ mixture disrupts its own clearance machinery in a BBB endothelium model.

Aβ mixture has differential effect on expression of P-gp, LRP1, and RAGE.

Acknowledgments

This research work was funded by an Institutional Development Award (IDeA) from the National Institute of General Medical Sciences of the National Institutes of Health under grant number P20GM103424.

Abbreviations

- AD

Alzheimer’s disease

- Aβ

amyloid-β

- APP

amyloid-β precursor protein

- BBB

blood-brain barrier

- IDE

insulin degrading enzyme

- LRP1

low density lipoprotein receptor-related protein-1

- NEP

neprilysin

- P-gp

P-glycoprotein

- RAGE

receptor for advanced glycation end products

- TCA

trichloroacetic acid

Footnotes

Conflict of interest

The authors declare no competing financial interest.

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

References

- 1.Citron M. Alzheimer’s disease: strategies for disease modification. Nat Rev Drug Discov. 2010;9:387–398. doi: 10.1038/nrd2896. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Huang Y, Mucke L. Alzheimer mechanisms and therapeutic strategies. Cell. 2012;148:1204–1222. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2012.02.040. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Ubhi K, Masliah E. Alzheimer’s disease: recent advances and future perspectives. J Alzheimers Dis. 2013;33(Suppl 1):S185–194. doi: 10.3233/JAD-2012-129028. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Selkoe DJ. Physiological production of the beta-amyloid protein and the mechanism of Alzheimer’s disease. Trends Neurosci. 1993;16:403–409. doi: 10.1016/0166-2236(93)90008-a. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Benilova I, Karran E, De Strooper B. The toxic Abeta oligomer and Alzheimer’s disease: an emperor in need of clothes. Nat Neurosci. 2012;15:349–357. doi: 10.1038/nn.3028. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Finder VH, Glockshuber R. Amyloid-beta aggregation. Neurodegener Dis. 2007;4:13–27. doi: 10.1159/000100355. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Jan A, Hartley DM, Lashuel HA. Preparation and characterization of toxic Abeta aggregates for structural and functional studies in Alzheimer’s disease research. Nat Protoc. 2010;5:1186–1209. doi: 10.1038/nprot.2010.72. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.McLean CA, Cherny RA, Fraser FW, Fuller SJ, Smith MJ, Beyreuther K, Bush AI, Masters CL. Soluble pool of Abeta amyloid as a determinant of severity of neurodegeneration in Alzheimer’s disease. Ann Neurol. 1999;46:860–866. doi: 10.1002/1531-8249(199912)46:6<860::aid-ana8>3.0.co;2-m. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Li S, Hong S, Shepardson NE, Walsh DM, Shankar GM, Selkoe D. Soluble oligomers of amyloid Beta protein facilitate hippocampal long-term depression by disrupting neuronal glutamate uptake. Neuron. 2009;62:788–801. doi: 10.1016/j.neuron.2009.05.012. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Irizarry MC, Soriano F, McNamara M, Page KJ, Schenk D, Games D, Hyman BT. Abeta deposition is associated with neuropil changes, but not with overt neuronal loss in the human amyloid precursor protein V717F (PDAPP) transgenic mouse. J Neurosci. 1997;17:7053–7059. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.17-18-07053.1997. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Wang J, Dickson DW, Trojanowski JQ, Lee VM. The levels of soluble versus insoluble brain Abeta distinguish Alzheimer’s disease from normal and pathologic aging. Exp Neurol. 1999;158:328–337. doi: 10.1006/exnr.1999.7085. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Irie K, Murakami K, Masuda Y, Morimoto A, Ohigashi H, Ohashi R, Takegoshi K, Nagao M, Shimizu T, Shirasawa T. Structure of beta-amyloid fibrils and its relevance to their neurotoxicity: implications for the pathogenesis of Alzheimer’s disease. J Biosci Bioeng. 2005;99:437–447. doi: 10.1263/jbb.99.437. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Bell RD, Zlokovic BV. Neurovascular mechanisms and blood-brain barrier disorder in Alzheimer’s disease. Acta Neuropathol. 2009;118:103–113. doi: 10.1007/s00401-009-0522-3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Cirrito JR, Deane R, Fagan AM, Spinner ML, Parsadanian M, Finn MB, Jiang H, Prior JL, Sagare A, Bales KR, Paul SM, Zlokovic BV, Piwnica-Worms D, Holtzman DM. P-glycoprotein deficiency at the blood-brain barrier increases amyloid-beta deposition in an Alzheimer disease mouse model. Journal of Clinical Investigation. 2005;115:3285–3290. doi: 10.1172/JCI25247. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Deane R, Sagare A, Zlokovic BV. The role of the cell surface LRP and soluble LRP in blood-brain barrier Abeta clearance in Alzheimer’s disease. Curr Pharm Des. 2008;14:1601–1605. doi: 10.2174/138161208784705487. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Qosa H, Abuznait AH, Hill RA, Kaddoumi A. Enhanced brain amyloid-beta clearance by rifampicin and caffeine as a possible protective mechanism against Alzheimer’s disease. J Alzheimers Dis. 2012;31:151–165. doi: 10.3233/JAD-2012-120319. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Deane R, Du Yan S, Submamaryan RK, LaRue B, Jovanovic S, Hogg E, Welch D, Manness L, Lin C, Yu J, Zhu H, Ghiso J, Frangione B, Stern A, Schmidt AM, Armstrong DL, Arnold B, Liliensiek B, Nawroth P, Hofman F, Kindy M, Stern D, Zlokovic B. RAGE mediates amyloid-beta peptide transport across the blood-brain barrier and accumulation in brain. Nat Med. 2003;9:907–913. doi: 10.1038/nm890. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Gao W, Eisenhauer PB, Conn K, Lynch JA, Wells JM, Ullman MD, McKee A, Thatte HS, Fine RE. Insulin degrading enzyme is expressed in the human cerebrovascular endothelium and in cultured human cerebrovascular endothelial cells. Neurosci Lett. 2004;371:6–11. doi: 10.1016/j.neulet.2004.07.034. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Lynch JA, George AM, Eisenhauer PB, Conn K, Gao W, Carreras I, Wells JM, McKee A, Ullman MD, Fine RE. Insulin degrading enzyme is localized predominantly at the cell surface of polarized and unpolarized human cerebrovascular endothelial cell cultures. J Neurosci Res. 2006;83:1262–1270. doi: 10.1002/jnr.20809. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Iwata N, Tsubuki S, Takaki Y, Watanabe K, Sekiguchi M, Hosoki E, Kawashima-Morishima M, Lee HJ, Hama E, Sekine-Aizawa Y, Saido TC. Identification of the major Abeta1-42-degrading catabolic pathway in brain parenchyma: suppression leads to biochemical and pathological deposition. Nat Med. 2000;6:143–150. doi: 10.1038/72237. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Qosa H, Abuasal BS, Romero IA, Weksler B, Couraud PO, Keller JN, Kaddoumi A. Differences in amyloid-beta clearance across mouse and human blood-brain barrier models: Kinetic analysis and mechanistic modeling. Neuropharmacology. 2014;79C:668–678. doi: 10.1016/j.neuropharm.2014.01.023. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Chen KL, Wang SS, Yang YY, Yuan RY, Chen RM, Hu CJ. The epigenetic effects of amyloid-beta(1-40) on global DNA and neprilysin genes in murine cerebral endothelial cells. Biochem Biophys Res Commun. 2009;378:57–61. doi: 10.1016/j.bbrc.2008.10.173. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Kania KD, Wijesuriya HC, Hladky SB, Barrand MA. Beta amyloid effects on expression of multidrug efflux transporters in brain endothelial cells. Brain Res. 2011;1418:1–11. doi: 10.1016/j.brainres.2011.08.044. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Carrano A, Hoozemans JJ, van der Vies SM, Rozemuller AJ, van Horssen J, de Vries HE. Amyloid Beta induces oxidative stress-mediated blood-brain barrier changes in capillary amyloid angiopathy. Antioxid Redox Signal. 2011;15:1167–1178. doi: 10.1089/ars.2011.3895. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Brenn A, Grube M, Peters M, Fischer A, Jedlitschky G, Kroemer HK, Warzok RW, Vogelgesang S. Beta-Amyloid Downregulates MDR1-P-Glycoprotein (Abcb1) Expression at the Blood-Brain Barrier in Mice. Int J Alzheimers Dis. 2011;2011:690121. doi: 10.4061/2011/690121. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Zlokovic BV. Neurovascular pathways to neurodegeneration in Alzheimer’s disease and other disorders. Nat Rev Neurosci. 2011;12:723–738. doi: 10.1038/nrn3114. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Forster C. Tight junctions and the modulation of barrier function in disease. Histochem Cell Biol. 2008;130:55–70. doi: 10.1007/s00418-008-0424-9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Hartz AM, Bauer B, Soldner EL, Wolf A, Boy S, Backhaus R, Mihaljevic I, Bogdahn U, Klunemann HH, Schuierer G, Schlachetzki F. Amyloid-beta contributes to blood-brain barrier leakage in transgenic human amyloid precursor protein mice and in humans with cerebral amyloid angiopathy. Stroke. 2012;43:514–523. doi: 10.1161/STROKEAHA.111.627562. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Gonzalez-Velasquez FJ, Kotarek JA, Moss MA. Soluble aggregates of the amyloid-beta protein selectively stimulate permeability in human brain microvascular endothelial monolayers. J Neurochem. 2008;107:466–477. doi: 10.1111/j.1471-4159.2008.05618.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Tai LM, Holloway KA, Male DK, Loughlin AJ, Romero IA. Amyloid-beta-induced occludin down-regulation and increased permeability in human brain endothelial cells is mediated by MAPK activation. J Cell Mol Med. 2010;14:1101–1112. doi: 10.1111/j.1582-4934.2009.00717.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Rensink AA, de Waal RM, Kremer B, Verbeek MM. Pathogenesis of cerebral amyloid angiopathy. Brain Res Brain Res Rev. 2003;43:207–223. doi: 10.1016/j.brainresrev.2003.08.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Klein WL. Abeta toxicity in Alzheimer’s disease: globular oligomers (ADDLs) as new vaccine and drug targets. Neurochem Int. 2002;41:345–352. doi: 10.1016/s0197-0186(02)00050-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.LeVine H., 3rd Alzheimer’s beta-peptide oligomer formation at physiologic concentrations. Anal Biochem. 2004;335:81–90. doi: 10.1016/j.ab.2004.08.014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Cooray HC, Shahi S, Cahn AP, van Veen HW, Hladky SB, Barrand MA. Modulation of p-glycoprotein and breast cancer resistance protein by some prescribed corticosteroids. Eur J Pharmacol. 2006;531:25–33. doi: 10.1016/j.ejphar.2005.12.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Weksler BB, Subileau EA, Perriere N, Charneau P, Holloway K, Leveque M, Tricoire-Leignel H, Nicotra A, Bourdoulous S, Turowski P, Male DK, Roux F, Greenwood J, Romero IA, Couraud PO. Blood-brain barrier-specific properties of a human adult brain endothelial cell line. FASEB J. 2005;19:1872–1874. doi: 10.1096/fj.04-3458fje. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Omidi Y, Campbell L, Barar J, Connell D, Akhtar S, Gumbleton M. Evaluation of the immortalised mouse brain capillary endothelial cell line, b.End3, as an in vitro blood-brain barrier model for drug uptake and transport studies. Brain Res. 2003;990:95–112. doi: 10.1016/s0006-8993(03)03443-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Nazer B, Hong S, Selkoe DJ. LRP promotes endocytosis and degradation, but not transcytosis, of the amyloid-beta peptide in a blood-brain barrier in vitro model. Neurobiol Dis. 2008;30:94–102. doi: 10.1016/j.nbd.2007.12.005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Shibata M, Yamada S, Kumar SR, Calero M, Bading J, Frangione B, Holtzman DM, Miller CA, Strickland DK, Ghiso J, Zlokovic BV. Clearance of Alzheimer’s amyloid-ss(1-40) peptide from brain by LDL receptor-related protein-1 at the blood-brain barrier. J Clin Invest. 2000;106:1489–1499. doi: 10.1172/JCI10498. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Hardy J. The amyloid hypothesis for Alzheimer’s disease: a critical reappraisal. J Neurochem. 2009;110:1129–1134. doi: 10.1111/j.1471-4159.2009.06181.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Hepler RW, Grimm KM, Nahas DD, Breese R, Dodson EC, Acton P, Keller PM, Yeager M, Wang H, Shughrue P, Kinney G, Joyce JG. Solution state characterization of amyloid beta-derived diffusible ligands. Biochemistry. 2006;45:15157–15167. doi: 10.1021/bi061850f. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Shankar GM, Leissring MA, Adame A, Sun X, Spooner E, Masliah E, Selkoe DJ, Lemere CA, Walsh DM. Biochemical and immunohistochemical analysis of an Alzheimer’s disease mouse model reveals the presence of multiple cerebral Abeta assembly forms throughout life. Neurobiol Dis. 2009;36:293–302. doi: 10.1016/j.nbd.2009.07.021. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Steinerman JR, Irizarry M, Scarmeas N, Raju S, Brandt J, Albert M, Blacker D, Hyman B, Stern Y. Distinct pools of beta-amyloid in Alzheimer disease-affected brain: a clinicopathologic study. Arch Neurol. 2008;65:906–912. doi: 10.1001/archneur.65.7.906. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Kawarabayashi T, Younkin LH, Saido TC, Shoji M, Ashe KH, Younkin SG. Age-dependent changes in brain, CSF, and plasma amyloid (beta) protein in the Tg2576 transgenic mouse model of Alzheimer’s disease. J Neurosci. 2001;21:372–381. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.21-02-00372.2001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Cecchelli R, Berezowski V, Lundquist S, Culot M, Renftel M, Dehouck MP, Fenart L. Modelling of the blood-brain barrier in drug discovery and development. Nat Rev Drug Discov. 2007;6:650–661. doi: 10.1038/nrd2368. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Poller B, Gutmann H, Krahenbuhl S, Weksler B, Romero I, Couraud PO, Tuffin G, Drewe J, Huwyler J. The human brain endothelial cell line hCMEC/D3 as a human blood-brain barrier model for drug transport studies. J Neurochem. 2008;107:1358–1368. doi: 10.1111/j.1471-4159.2008.05730.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Gravina SA, Ho L, Eckman CB, Long KE, Otvos L, Jr, Younkin LH, Suzuki N, Younkin SG. Amyloid beta protein (A beta) in Alzheimer’s disease brain. Biochemical and immunocytochemical analysis with antibodies specific for forms ending at A beta 40 or A beta 42(43) J Biol Chem. 1995;270:7013–7016. doi: 10.1074/jbc.270.13.7013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Marco S, Skaper SD. Amyloid beta-peptide1-42 alters tight junction protein distribution and expression in brain microvessel endothelial cells. Neurosci Lett. 2006;401:219–224. doi: 10.1016/j.neulet.2006.03.047. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Villain N, Chetelat G, Grassiot B, Bourgeat P, Jones G, Ellis KA, Ames D, Martins RN, Eustache F, Salvado O, Masters CL, Rowe CC, Villemagne VL. Regional dynamics of amyloid-beta deposition in healthy elderly, mild cognitive impairment and Alzheimer’s disease: a voxelwise PiB-PET longitudinal study. Brain. 2012;135:2126–2139. doi: 10.1093/brain/aws125. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.