Abstract

We previously showed that striated muscle-selective depletion of lamina-associated polypeptide 1 (LAP1), an integral inner nuclear membrane protein, leads to profound muscular dystrophy with premature death in mice. As LAP1 is also depleted in hearts of these mice, we examined their cardiac phenotype. Striated muscle-selective LAP1 knockout mice display ventricular systolic dysfunction with abnormal induction of genes encoding cardiomyopathy related proteins. To eliminate possible confounding effects due to skeletal muscle pathology, we generated a new mouse line in which LAP1 is deleted in a cardiomyocyte-selective manner. These mice had no skeletal muscle pathology and appeared overtly normal at 20 weeks of age. However, cardiac echocardiography revealed that they developed left ventricular systolic dysfunction and cardiac gene expression analysis revealed abnormal induction of cardiomyopathy-related genes. Our results demonstrate that LAP1 expression in cardiomyocytes is required for normal left ventricular function, consistent with a report of cardiomyopathy in a human subject with mutation in the gene encoding LAP1.

Keywords: nuclear lamins, inner nuclear membrane, LAP1, cardiomyopathy, nuclear envelope

Introduction

Mutations in genes encoding nuclear lamins and other nuclear envelope proteins cause a broad range of human diseases.1 Mutations in the LMNA gene encoding lamins A and C cause autosomal dominant Emery-Dreifuss muscular dystrophy, which is classically characterized by early joint contractures, progressive wasting, and muscle weakness in a scapulohumeral peroneal distribution and dilated cardiomyopathy with conduction defects.2-4 Cardiomyopathy is the life-threatening feature of this disease.3,5 The same mutations in LMNA can also cause dilated cardiomyopathy with much more variable skeletal muscle involvement.6-8

Mutations in genes encoding proteins interacting with lamins A and C can also cause muscular dystrophy and cardiomyopathy, suggesting that these may function together in striated muscle physiology. Emerin, the widely expressed inner nuclear membrane protein, binds to lamins A and C and mutations in its gene, EMD, cause X-linked Emery-Dreifuss muscular dystrophy as well as related disorders with a prominent dilated cardiomyopathy, cardiac conduction abnormalities and variable skeletal muscle involvement.9-11 Emerin knockout mice, however, develop only very minimal skeletal muscle pathology and first-degree atrioventricular conduction at ages older than 40 weeks.12 Subsequently, an amino-acid substitution in another integral inner nuclear membrane protein that binds to lamin A and C, lamina-associated polypeptide 2-α, was found in two affected brothers with dilated cardiomyopathy.13 Germline deletion of the gene encoding lamina-associated polypeptide 2-α from mice induces cardiomyopathy with systolic dysfunction and sporadic fibrosis, suggesting its requirement in the maintenance of normal cardiac function.14,15

Lamina-associated polypeptide 1 (LAP1) is an integral inner nuclear membrane protein encoded by the human gene TOR1AIP1.16,17 Three LAP1 isoforms arise by alternative RNA splicing designated LAP1A, LAP1B, and LAP1C with molecular masses of 75, 68, and 55 kDa, respectively.18,19 Biochemical extractions showed that they are associated with the nuclear lamina.20 Subsequent studies showed that LAP1 interacts with torsinA and protein phophatase1.21-23 We have shown recently that LAP1 interacts with emerin and that they function together in striated muscle maintenance.16,17 LAP1 conditional deletion from striated muscle causes a profound muscular dystrophy leading to early death. As mutations in genes encoding other integral inner nuclear membrane proteins that interact with lamins A and C cause cardiomyopathy as well as muscular dystrophy, we examined the potential physiological significance of LAP1 in heart development and function.

Results

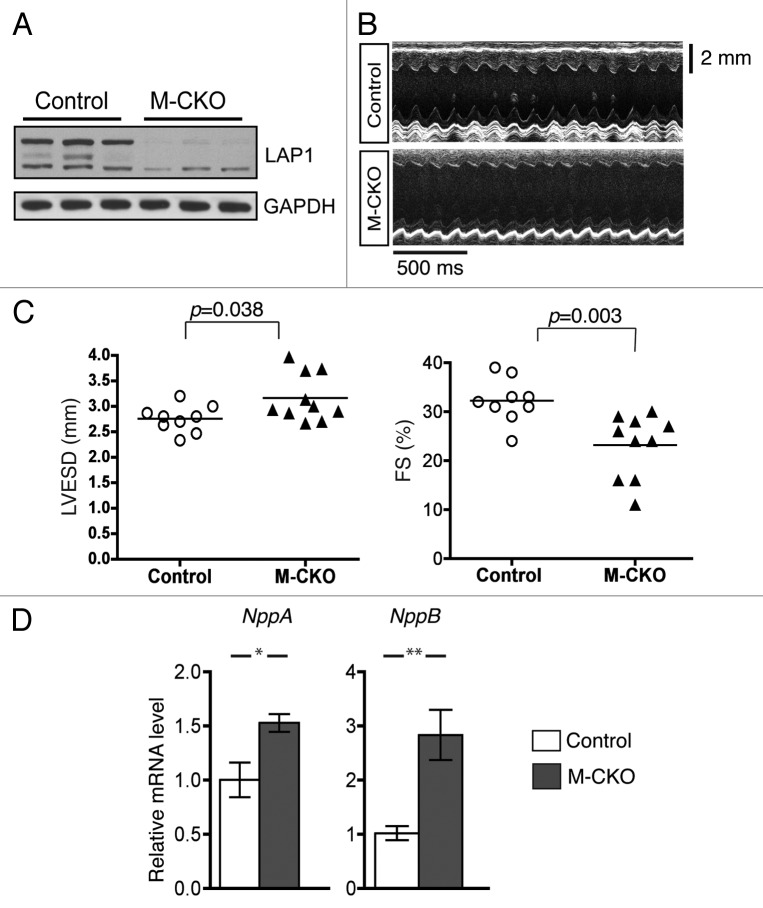

Analysis of hearts in mice with striated muscle-selective depletion of LAP1

We have previously generated a striated muscle-selective conditional LAP1 knockout mouse line by crossing Tor1aip1 floxed mice to MCK-Cre transgenic mice (we referred to these MCK-Cre+/−;Tor1aip1f/f mice as M-CKO mice) and demonstrated that they develop muscular dystrophy and have a shortened lifespan with a medial survival for male mice of approximately 21 weeks.16 As the MCK promoter is also expressed in cardiac muscle, we examined the effect of LAP1 depletion in hearts from M-CKO mice at 9–10 week of age. We confirmed that heart tissue of 9–10 week-old M-CKO mice is almost devoid of LAP1 protein (Fig. 1A). To assess cardiac dysfunction, we performed echocardiography on 9- to 10-week-old control and M-CKO mice (Fig. 1B). Echocardiograms from control and M-CKO mice were analyzed to obtain mean values for heart rate, left ventricular fractional shortening, ejection fraction, and left ventricular end-diastolic and end-systolic diameters (Table 1). Left ventricular end-systolic diameter was significantly increased and left ventricular fractional shortening, which is directly proportional to ejection fraction, was significantly decreased in M-CKO mice (Fig. 1C). This indicated defects in systolic function. Consistent with left ventricular stretching or increased wall tension, expression of NppA and NppB mRNAs respectively encoding atrial natriuretic peptide precursor and brain natriuretic peptide precursor was increased in hearts of M-CKO mice compared with control mice (Fig. 1D).

Figure 1. Analysis of hearts of M-CKO mice with striated muscle-selective depletion of LAP1. (A) Protein extracts from hearts of control (Tor1aip1f/f) and M-CKO mice with striated muscle depletion of LAP1 were used for immunoblotting with antibodies against LAP1 and GAPDH antibodies. Each lane contains an extract from a different mouse. (B) Representative transthoracic M-mode echocardiographic tracing of control and M-CKO male mice at 9–10 weeks of age. (C) Left ventricular end-systolic diameter (LVESD) and fractional shortening (FS) in control (n = 9) and M-CKO (n = 10) male mice at 9–10 weeks of age. Each circle and triangle represents a value from individual mice, and the horizontal bars indicate means. (D) Means ± standard errors of relative expression of mRNAs encoded by NppA and NppB in hearts of control (n = 4) and M-CKO (n = 4) mice at 12 weeks of age. *P < 0.05; **P < 0.01.

Table 1. Echocardiographic parameters for male control and M-CKO mice at 9–10 weeks of age. Values are means ± standard errors for heart rate (HR), left ventricular fractional shortening (FS), left ventricular ejection fraction (EF), left ventricular end-diastolic diameter (LVEDD), and left ventricular end-systolic diameter (LVESD).

| Control (n = 9) | M-CKO (n = 10) | |

|---|---|---|

| HR | 507.9 ± 5.89 | 509.5 ± 4.09 |

| FS (%) | 32.22 ± 1.49 | 23.1 ± 2.05 ** |

| EF (%) | 60.38 ± 2.24 | 46.25 ± 3.64 * |

| LVEDD (mm) | 4.04 ± 0.053 | 4.09 ± 0.091 n.s. |

| LVESD (mm) | 2.75 ± 0.087 | 3.10 ± 0.120 * |

*P < 0.05, **P < 0.01, n.s., not significant (calculated using unpaired, two-tailed student’s t test).

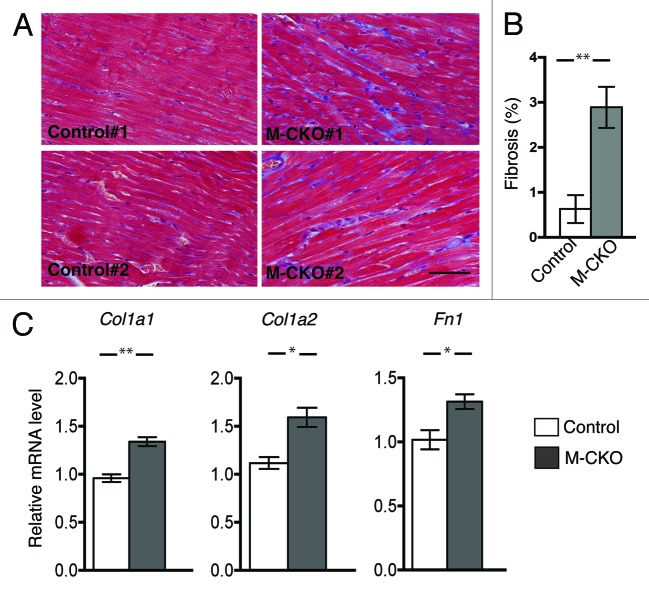

The structure and organization of myofibrils was not overtly altered in left ventricles of 12 week-old M-CKO mice based on histopathological examination of hematoxylin and eosin-stained tissue sections (data not shown). However, staining of heart sections from the M-CKO mice with Masson’s trichrome showed an increase in fibrosis (Fig. 2A and B). Expression of the mRNAs of genes encoding collagen 1 (Col1a1 and Col1a2) and fibronectin (Fn1) was also significantly increased in hearts from M-CKO mice compared with control mice (Fig. 2C), consistent with the induction of myocardial fibrosis.

Figure 2. Cardiac fibrosis in M-CKO mice with striated muscle-selective depletion of LAP1. (A) Masson’s trichrome staining of heart sections from two different 12 week-old control (Tor1aip1f/f) and M-CKO mice are shown. Bar = 50 μm (B) Ventricle sections from 12 weeks-old Tor1aip1f/f mice (Control) and M-CKO mice were stained with Masson’s trichrome as shown in previous panel and percentage of fibrosis per each image was averaged. Two different regions from each section from three mice per group (n = 6) were analyzed. Values are means ± standard errors; **P < 0.01. (C) Means ± standard errors of relative expression of mRNAs encoded by Col1a1, Col1a2 and Fn1 in hearts of control (n = 4) and M-CKO (n = 4) mice at 12 weeks of age. *P < 0.05; **P < 0.01.

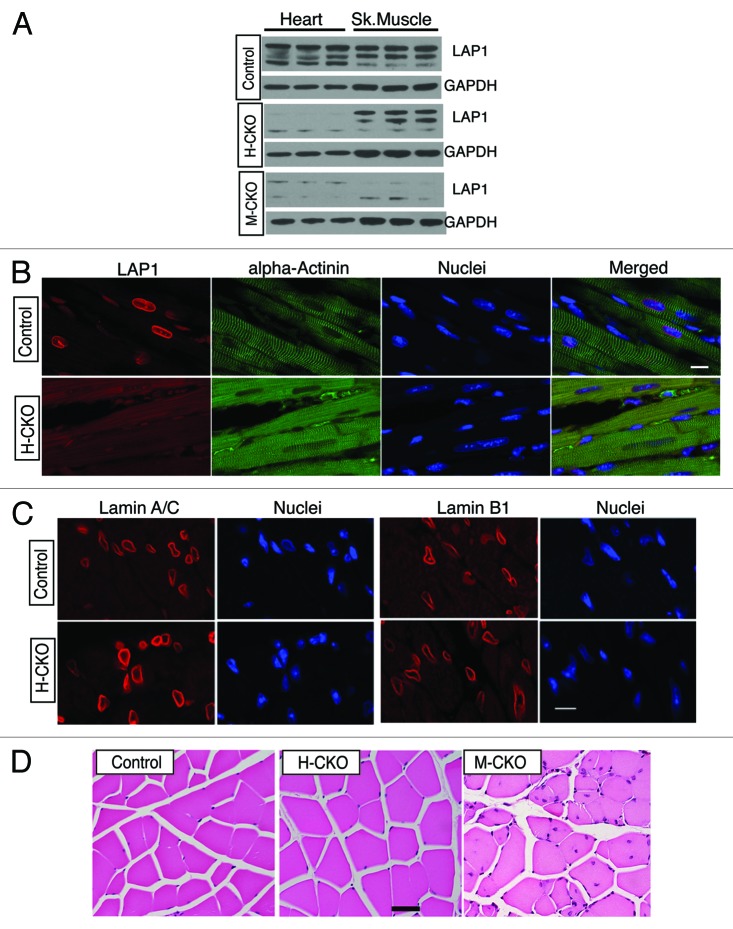

Generation and characterization of mice with cardiomyocyte-selective depletion of LAP1

As M-CKO mice exhibit profound muscular dystrophy with premature death, it is possible that the observed cardiac dysfunction could result from cachexia, malnourishment or some other indirect effect. To generate heart muscle-selective LAP1 conditional knockout mice (H-CKO), we crossed transgenic mice expressing the myosin heavy chain 6 (Myh6) promoter driving Cre expression (Myh6-Cre mice) to Tor1aip1 floxed mice. Myh6-Cre transgenic mice have been widely used to delete genes flanked with loxP sequences in a heart-selective manner, as Myh6 driven Cre expression is restricted to cardiomyocytes.24-26 The cardiomyocyte-selective LAP1-depleted H-CKO mice (Myh6-Cre+/−;Tor1aip1f/f) were born in expected Mendelian ratios and were indistinguishable from their littermate controls in body mass and growth rate until 20 weeks of age (data not shown). To confirm selective LAP1 depletion in heart, we compared the expression of LAP1 in hearts and other tissues from control, M-CKO, and H-CKO mice. While LAP1 expression was unchanged in protein extracts of skeletal muscles from control and H-CKO mice, it was selectively depleted in heart protein lysates from H-CKO mice. In contrast, LAP1 was depleted from both skeletal and heart muscle in M-CKO (Fig. 3A). The residual expression of LAP1 from heart extracts of H-CKO and M-CKO mice is presumably from non-muscle cells such as fibroblasts or endothelial cells. The expression of LAP1 in protein extracts of liver and lung was not altered in H-CKO mice (data not shown). Selective depletion of LAP1 in cardiomyocytes of H-CKO mice was confirmed by immunofluorescence microscopy of left ventricle tissue sections double labeled with antibodies against of LAP1 and α-actinin. While LAP1 was co-expressed with α-actinin in left ventricle sections from control mice, LAP1 expression was undetectable in α-actinin-expressing cardiomyocytes in H-CKO mice (Fig. 3B). Expression of lamin A and C and lamin B1 was similar in the left ventricles sections from both control and H-CKO animals (Fig. 3C). To ensure that skeletal muscle was not affected in H-CKO mice, we examined hematoxylin and eosin-stained sections of quadriceps from control, H-CKO, and M-CKO mice. In contrast to quadriceps from 12-week-old M-CKO mice showing myopathic features such as degenerative myofibers and central nuclei, sections from 20-week-old H-CKO mice did not display any myopathic defects (Fig. 3D). These results indicated that LAP1 was selectively depleted in cardiomyocytes but not skeletal muscle of H-CKO mice.

Figure 3. Generation and characterization of H-CKO mice with cardiomyocyte-selective depletion of LAP1. (A) Protein extracts from hearts and skeletal muscles (Sk. muscle) from control (Tor1aip1f/f), H-CKO and M-CKO mice were used for immunoblotting with antibodies against LAP1 and GAPDH. LAP1 isoforms were detected by the anti-LAP1 antibody. Each lane contains an extract from a different mouse. (B) Micrographs showing immunofluorescence labeling of LAP1 (red) and α-actinin (green) in left ventricle sections from control and H-CKO mice. Nuclei were stained with 4’,6-diamidino-2-phenylindole (blue). Bar = 10 μm (C) Micrographs showing immunofluorescence labeling of lamin A and C (lamin A/C, red) and lamin B1 (red) on cross sections of heart from control and H-CKO mice. Nuclei were stained with 4’,6-diamidino-2-phenylindole (blue). Bar = 10 μm. (D) Micrographs of hematoxylin and eosin-stained cross sections of quadriceps muscle from control, H-CKO at 20 weeks of age and M-CKO male mice at 12 weeks of age. Bar = 50 μm

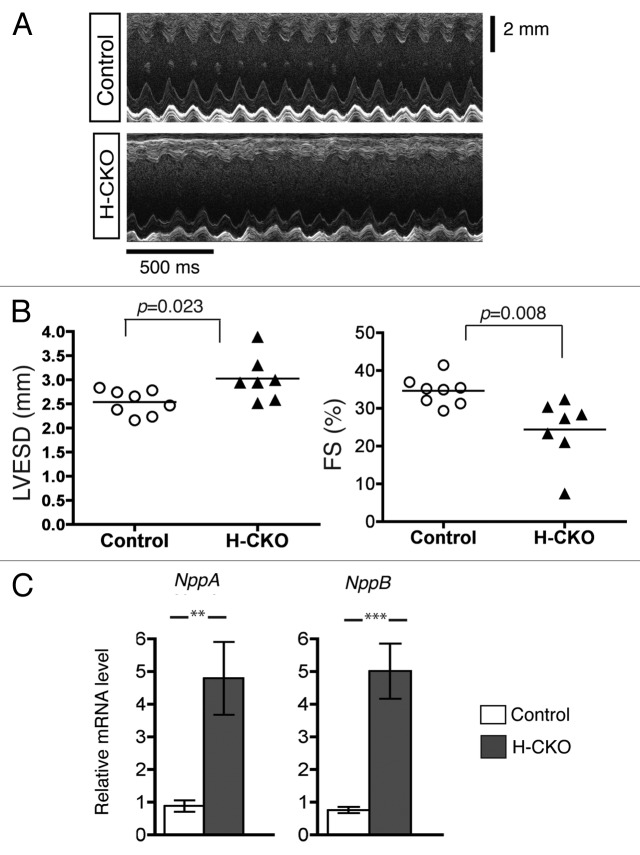

Analysis of hearts of mice with cardiomyocyte-selective depletion of LAP1

To determine if H-CKO mice have cardiac dysfunction, we performed transthoracic M-mode echocardiography when mice were 20 weeks of age (Fig. 4A). The resulting echocardiograms from control and H-CKO mice were analyzed to obtain mean values for heart rate, left ventricular fractional shortening, ejection fraction and left ventricular end-diastolic and end-systolic diameters (Table 2). Left ventricular end-systolic diameter was significantly increased and left ventricular fractional shortening (directly proportional to ejection fraction) was significantly decreased by approximately 30% in H-CKO mice compared with controls (Fig. 4B). These findings indicated that H-CKO mice exhibit significant defects of systolic function. Consistent with this finding, the expression of NppA and NppB mRNAs were also increased in hearts of H-CKO mice compared with controls (Fig. 4C). We also performed electrocardiography and did not find significant differences in PR interval or QRS duration between H-CKO and control mice at 20 weeks of age (Fig. S1).

Figure 4. Analysis of hearts of H-CKO mice with cardiomyocyte-selective depletion of LAP1. (A) Representative transthoracic M-mode echocardiographic tracing of control and H-CKO mice at 20 weeks of age. (B) Left ventricular end-systolic diameter (LVESD) and fractional shortening (FS) in control (n = 8) and H-CKO (n = 7) mice at 20 weeks of age. Each circle and triangle represents a value from individual mice, and the horizontal bars indicate means. (C) Means ± standard errors of relative expression of mRNAs encoded by NppA and NppB in hearts of control (n = 4) and H-CKO (n = 4) mice at 20 weeks of age. **P < 0.01; ***P < 0.001

Table 2. Echocardiographic parameters for male control and H-CKO mice at 20 weeks of age. Values are means ± standard errors for heart rate (HR), left ventricular fractional shortening (FS), left ventricular ejection fraction (EF), left ventricular end-diastolic diameter (LVEDD), and left ventricular end-systolic diameter (LVESD).

| Control (n = 8) | H-CKO (n = 7) | |

|---|---|---|

| HR | 500.1 ± 0.97 | 500.1 ± 1.33 |

| FS (%) | 34.57 ± 1.32 | 24.30 ± 3.17 ** |

| EF (%) | 64.21 ± 1.72 | 53.19 ± 2.82 ** |

| LVEDD (mm) | 3.87 ± 0.141 | 4.13 ± 0.209 n.s. |

| LVESD (mm) | 2.53 ± 0.091 | 3.02 ± 0.175 * |

*P < 0.05, **P < 0.01, n.s., not significant (calculated using unpaired, two-tailed student’s t test).

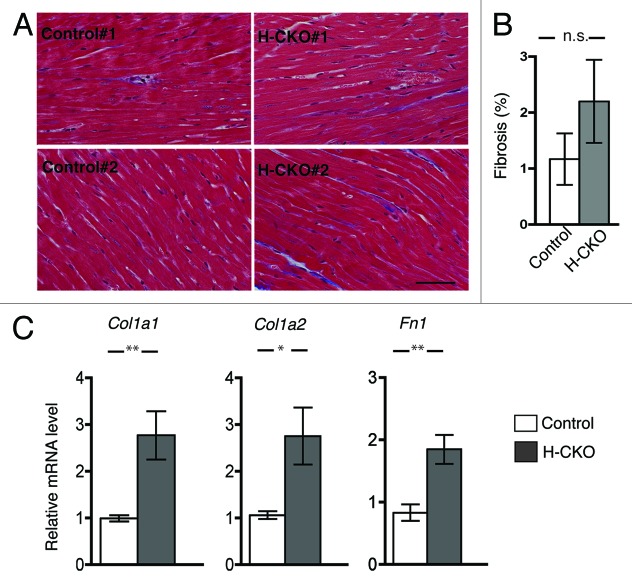

The structure and organization of myofibrils was not overtly altered in left ventricle of 20-week-old H-CKO mice when analyzed by hematoxylin and eosin-stained tissue sections (data not shown). Staining of heart sections from 20-week-old H-CKO mice with Masson’s trichrome showed a trend toward increased fibrosis but the difference was not statistically significant (Fig. 5A and B). However, expression of mRNAs of genes encoding collagen 1 and fibronectin was significantly increased in hearts from H-CKO mice compared with controls indicating induction of myocardial fibrosis (Fig. 5C).

Figure 5. Cardiac fibrosis in H-CKO mice with cardiomyocyte-selective depletion of LAP1. (A) Masson’s trichrome staining of heart sections from two different 20 week-old control (Tor1aip1f/f) and H-CKO mice are shown. Bar = 50 μm (B) Ventricle sections from 20 week-old Tor1aip1f/f mice (Control) and H-CKO mice were stained with Masson’s trichrome as shown in previous panel and percentage of fibrosis per each image was averaged. Two different regions from each section from three mice per group (n = 6) were analyzed. Values are means ± standard errors; n.s. = not significant (C) Means ± standard errors of relative expression of mRNAs encoded by Col1a1, Col1a2 and Fn1 in hearts of control (n = 4) and H-CKO (n = 4) mice at 20 weeks of age. *P < 0.05, **P < 0.01.

Impaired mitogen-activated protein kinase signaling in hearts of mice with cardiomyocyte-selective depletion of LAP1

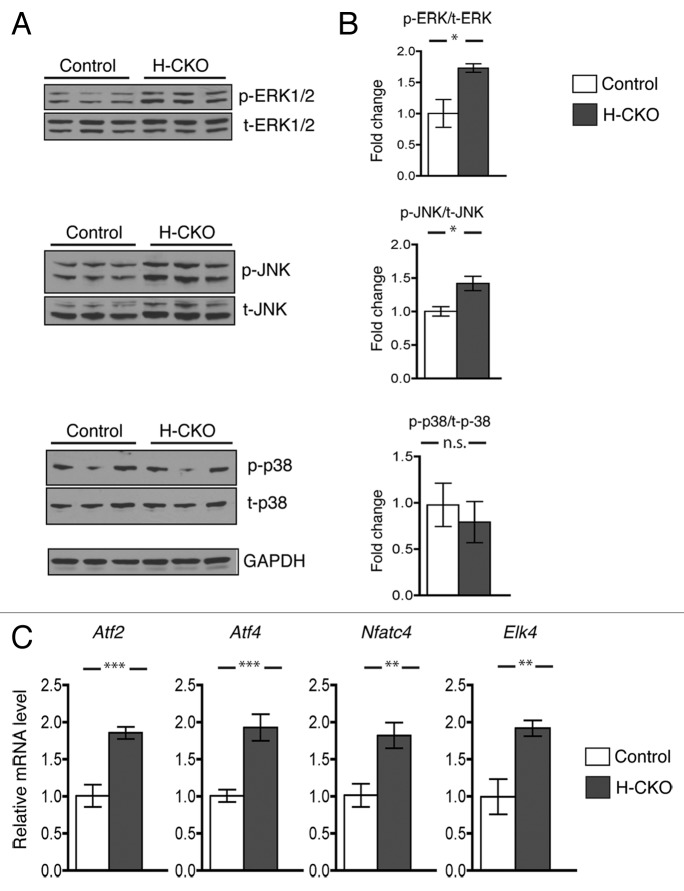

We have previously shown abnormal activation of the extracellular signal-regulated kinase 1/2 (ERK1/2), c-Jun N-terminal kinase (JNK), and p38alpha branches of the mitogen-activated protein kinase signaling pathways in hearts of mice modeling autosomal (LmnaH222P/H222P knock-in mice)27 and X-linked (emerin null mice)28 Emery-Dreifuss muscular dystrophy. Furthermore, pharmacological or genetic inhibition of these signaling cascades improve cardiac function in LmnaH222P/H222P mice.29-33 We therefore assessed phosphorylated (activated) ERK1/2, JNK and p38alpha in protein extracts of hearts from H-CKO and controls at 20 week of age (Fig. 6A). H-CKO mice exhibited increased cardiac activation of ERK1/2 and JNK but not p38alpha (Fig. 6B). Consistently, expression of mRNAs encoded by Atf2, Atf4, Nfatc4, Elk4, downstream genes in the ERK1/2 and JNK signaling cascades, was significantly increased in H-CKO mice (Fig. 6C). In hearts from M-CKO mice, we similarly found increased cardiac activation of ERK1/2 and JNK but not p38alpha compared with controls (Fig. S2). These data indicate that the ERK1/2 and JNK signaling pathways are abnormally activated in hearts lacking LAP1 in mice that develop left ventricular dysfunction.

Figure 6. Mitogen-activated protein kinase signaling in hearts of H-CKO mice with cardiomyocyte-selective depletion of LAP1. (A) Immunoblots using antibodies against phosphorylated ERK1/2 (p-ERK1/2), total ERK1/2 (t-ERK1/2), phosphorylated JNK (p-JNK), total JNK (t-JNK), phosphorylated p38alpha (p-p38), and total p38alpha (t-p38) and GAPDH of protein extracts from hearts of control and H-CKO mice at 20 weeks of age. Each lane contains an extract from a different mouse. (B) Bar graphs showing quantification of the ratio of the phosphorylated protein signals to their respective total protein signals. Values are means ± standard errors (control n = 3; H-CKO n = 3). *P < 0.05, n.s. = not significant. Graphs are presented as fold change over controls. (C) Means ± standard errors of relative expression of mRNAs encoded by Atf2, Atf4, Nfatc4, and Elk4, genes activated by phosphorylated mitogen-activated protein kinases, in hearts of control (n = 4) and H-CKO (n = 4) mice at 20 weeks of age. **P < 0.01, ***P < 0.001.

Discussion

Our findings demonstrate the pathological effects of targeted depletion of LAP1 in intact heart. Both striated muscle-selective and cardiomyocyte-selective LAP1 deletions cause left ventricular systolic dysfunction, leading to decreased fractional shortening and/or ejection fraction, enhanced expression of natriuretic peptides, and myocardial fibrosis-related genes. The consistent results from two different animal models lead us to conclude that LAP1 is required for normal cardiac function.

LAP1 interacts with lamins and emerin.16,20 suggesting that these proteins may form a complex important for maintaining the integrity of the nuclear envelope. In mice, loss of A-type lamins leads to much more significant, early onset cardiac dysfunction, with Lmna null mice developing a severe dilated cardiomyopathy by 6 to 8 weeks of age.34 Mice with homozygous amino acid substitutions or a single amino acid deletion from A-type lamins also develop profound dilated cardiomyopathy.35-37 In contrast, emerin null mice develop minimal cardiac disease.12,38 Loss of LAP1 from striated muscle, or more selectively from cardiomyocytes, causes an intermediate phenotype, with systolic dysfunction but without marked left ventricular dilatation. Hence, the differing phenotypes may be due to differences in the relative importance of A-type lamins, emerin, and LAP1 in forming a protein complex that maintains nuclear envelope integrity.

Defects in a complex composed of A-type lamins, emerin, and LAP1 that functions in maintaining nuclear envelope integrity may make cells more susceptible to stress, leading to abnormal activation of stress-induced signaling cascades in cardiomyocytes subjected to contractile stress. We detected an abnormal activation of the stress-induced mitogen-activated protein kinases ERK1/2 and JNK in hearts of 20 week-old H-CKO mice with reduced LAP1 in cardiomyocytes. We have previously shown abnormally increased activities of the ERK1/2, JNK and p38alpha branches of the mitogen-activated protein kinase pathway in LmnaH222P/H222P mice that have a significant dilated cardiomyopathy at 20 weeks of age.27,39 In contrast, emerin null mice that have no detectable cardiac pathology at 20 weeks of age have increased activity of the ERK1/2 branch.28 It is therefore tempting to speculate that the severity of cardiac pathology in mice with alterations in LAP1, emerin or A-type lamins results from the degree of overall activation of these three branches of the mitogen-activated protein kinase pathway. While there is indeed a correlation, this hypothesis remains to be tested.

Although striated muscle-selective and cardiomyocyte-selective deletion of LAP1 leads to somewhat similar cardiac phenotypes, those lacking LAP1 from all striated muscle have a medial survival of only approximately 21 weeks of age16 while those lacking LAP1 only from cardiomyocytes appear overtly normal at the same age. Hence, it appears that skeletal muscle myocytes are more susceptible to damage from loss of LAP1 than cardiomyocytes. It is unlikely that this difference is originated from the timing of Cre expression as MCK-Cre is expressed at approximately embryonic day 17 in differentiating myocytes,40,41 and Myh6-Cre is expressed from embryonic day 11.5 throughout the myocardium.42,43

Recently, three affected members of a Turkish family with an autosomal recessive limb-girdle muscular dystrophy with joint contractures were reported to carry a mutation in TOR1AIP1 that generates a premature stop codon in the LAP1B coding sequence.44 One affected subject had no cardiac disease at 29 years of age. Another had mild diastolic and systolic dysfunction with an ejection fraction of 57%, a normal electrocardiogram and 24 h Holter monitoring that showed sinus rhythm without heart block or ventricular dysrhythmias. These cardiac findings in this patient are similar to those in our mouse models. Hence, analysis of the TOR1AIP1 gene encoding LAP1 should be considered in patients with inherited muscular dystrophy and cardiomyopathy of unknown genetic origin.

Materials and Methods

Animals

The Institutional Animal Care and Use Committee of Columbia University Medical Center approved all protocols. Mice were kept at room temperature and fed normal chow. The generation and maintenance of floxed alleles of Tor1aip1 (Tor1aip1f/f) and MCK-Cre mice from Jackson laboratory (stock number: 006475) were previously described.16 Myh6-Cre transgenic mice were obtained from Jackson laboratory (stock number: 011038). All mouse lines were maintained on a C57BL/6 background. To generate heart-selective Lap1 knockout mice, Myh6-Cre+/− were bred with Tor1aip1flf mice to obtain Myh6-Cre+/−; Tor1aip1fl+ mice. As described previously,16 the expression of three isoforms of LAP1 was eliminated in the presence of Cre recombinase. These animals were fertile and produced at the expected Mendelian frequency. They were subsequently backcrossed with Tor1aip1f/f mice to obtain Myh6-Cre+/−; Tor1aip1flf (referred to as H-CKO) mice. Mice were monitored and body mass measured weekly after weaning. To genotype Myh6-Cre mice, PCR was performed from tail biopsies using the following primer sequences: 5′-ATGACAGACA GATCCCTCCT ATCTCC-3′ and 5′-CTC ATCACTC GTTGCATCAT CGAC-3′.

Echocardiography

Transthoracic echocardiography was performed as described previously.31,33 Briefly, mice were anesthetized with isoflurane and/or oxygen (1.5%) and all procedures were performed at room temperature. Echocardiography was performed using a Vevo 770 imaging system (Visualsonics) equipped with a 30-MHz linear transducer applied to the chest wall. The echocardiographers who performed the procedures and analyzed the data were blinded to the genotype of the mice.

Electrocardiography

Electrocardigrams were recorded from mice sedated with low-dose inhaled isoflurane using the standard four limb leads and a B08 amplifier (Emka Technologies) with minimal filtering. Waveforms were recorded using Iox Software v1.8.9.18 and intervals were measured manually with ECG Auto v1.5.12.50, using the average of three representative consecutive beats. The electrocardiographer was blinded to mouse genotype.

Quantitative Real Time PCR

Total RNA was extracted from mouse hearts using the RNeasy isolation Kit (Qiagen) as described previously.29,30 Quality and concentrations of RNA were measured using a Nanodrop spectrophotometer (Thermo Scientific). The cDNA was synthesized using Superscript First Strand Synthesis System according to the manufacturer’s instructions (Life Technology). For each replicate in each experiment, RNA from ventricular muscle of different animals was used. PCR primers for Nppa, Nppb, Col1a1, Col1a2, Fn1, Atf2, Atf4, Nfatc4, Elk4, and Gapdh have been described previously.27,29 Quantitative PCR was performed on an ABI 7300 Real-Time PCR System (Applied Biosystems) using HotStart-IT SYBR green qPCR Master Mix (Affymetrix). Relative levels of mRNA expression were calculated using the ΔΔCT method. Individual expression values were normalized by comparison to Gapdh mRNA.

Histology and immunohistochemistry

Mouse hearts or skeletal muscles were placed in 10% neutral buffered formalin for 48 h and embedded in paraffin and sectioned at 5 μm. Sections were stained with hematoxylin and eosin for histopathological assessment. Masson’s trichrome staining was performed to identify collagen-rich fibrotic regions as described previously.31 Stained sections were photographed using a DP72 digital camera attached to a BX53 upright light microscope (Olympus). Fibrotic area was quantified as described previously.16,30 Briefly, Images of Masson’s trichrome-stained sections were analyzed by Jmicrovision software (http://www.jmicrovision.com/). Uploaded images were set up as 2D measurement to obtain Hue histograms in which colors were represented from 0–255 units. The histogram values corresponding to blue color (140–200 units) were summed and the percentage fibrotic area (blue) was calculated out of total values.

For immunohistochemistry, mouse hearts were fixed in 10% neutral buffered formalin for 24 h and moved to 30% sucrose for 24 h. Cryosections were then cut at 5 µm thickness and processed for immunohistochemistry using an M.O.M Kit (Vector Labs). Primary antibodies were anti-α-actinin (Sigma, #A7811), anti-LAP1,21 anti-lamin A/C (Santa Cruz Biotechnologies Inc #SC-20681) and anti-lamin B145 antibodies. Alexa Fluor 488 and 594 conjugated secondary antibodies (Molecular Probes) were used to visualize the primary antibody labeling. Coverslips were mounted with Prolong Gold Anti-fade with 4',6-diamidino-2-phenylindole (Life Technologies) and images acquired using an A1 scanning confocal microscope on an Eclipse Ti microscope stand (Nikon). All images were taken using a 40×/1.3 Plan-Fluor objective lens.

Protein extraction and immunoblotting

Dissected tissues were homogenized in radioimmunoprecipitation assay buffer (RIPA Buffer, Cell Signaling) containing Protease Inhibitor Cocktail (Roche) plus 1 mM phenylmethanesulfonyl fluoride (Sigma). Proteins in samples were denatured by boiling in Laemmli sample buffer46 containing β-mercaptoethanol for 5 min, separated by SDS-PAGE and transferred to nitrocellulose membranes.

For immunoblotting, membranes containing proteins transferred from SDS-polyacrylamide gels were washed with blocking buffer (5% bovine serum albumin and 0.2% polysorbate 20 in phosphate-buffered saline) for 30 min and probed with primary antibodies in blocking buffer overnight at 4 °C. The primary antibodies used for immunoblotting were against LAP1,21 GAPDH (Ambion #AM4300), total ERK1/2 (Santa Cruz Biotechnologies Inc #SC-94), phosphorylated ERK1/2 (Cell Signaling #9101), total JNK (Santa Cruz Biotechnologies Inc #SC-474), phosphorylated JNK (Cell Signaling, #9251), total p38α (Cell Signaling, #9212), phosphorylated p38α (Cell Signaling, #4511). Blots were washed with 0.2% Tween-20 in phosphate-buffered saline and then incubated in blocking buffer with horseradish peroxidase-conjugated secondary antibodies (Amersham) for 1 h at room temperature. Recognized proteins were visualized by enhanced chemiluminescence (Thermo Scientific) and detected by exposure on X-ray films (Kodak). To quantify signals, immunoblots were scanned and densities of the bands quantified using ImageJ64 software. The LAP1 bands density was normalized to GAPDH signal density of each sample. For mitogen-activated protein kinases, band intensity of phosphorylated protein was normalized to the band intensity of respective total protein.

Supplementary Material

Disclosure of Potential Conflicts of Interest

No potential conflict of interest was disclosed.

Acknowledgments

J.-Y.S. is a recipient of a development grant from the Muscular Dystrophy Association (MDA no. 171880). C.L.D. is a recipient of a postdoctoral fellowship from the French Muscular Dystrophy Association, Association Française contre les Myopathies (AFM no. 16054). J.P.M. is supported by NIH grant 1K08HL105801. This work was supported by NIH/NIAMS grant AR048997 to H.J.W. and a University of Michigan Neuroscience Scholar Award to W.T.D.

Glossary

Abbreviations:

- ERK1/2

extracellular signal-regulated kinase 1/2

- JNK

c-jun N-terminal kinase, LAP1, lamina-associated polypeptide 1

- MCK

muscle creatine kinase

- Myh6

myosin heavy chain 6

References

- 1.Dauer WT, Worman HJ. The nuclear envelope as a signaling node in development and disease. Dev Cell. 2009;17:626–38. doi: 10.1016/j.devcel.2009.10.016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Emery AE, Dreifuss FE. Unusual type of benign x-linked muscular dystrophy. J Neurol Neurosurg Psychiatry. 1966;29:338–42. doi: 10.1136/jnnp.29.4.338. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Emery AE. X-linked muscular dystrophy with early contractures and cardiomyopathy (Emery-Dreifuss type) Clin Genet. 1987;32:360–7. doi: 10.1111/j.1399-0004.1987.tb03302.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Bonne G, Di Barletta MR, Varnous S, Bécane HM, Hammouda EH, Merlini L, Muntoni F, Greenberg CR, Gary F, Urtizberea JA, et al. Mutations in the gene encoding lamin A/C cause autosomal dominant Emery-Dreifuss muscular dystrophy. Nat Genet. 1999;21:285–8. doi: 10.1038/6799. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Waters DD, Nutter DO, Hopkins LC, Dorney ER. Cardiac features of an unusual X-linked humeroperoneal neuromuscular disease. N Engl J Med. 1975;293:1017–22. doi: 10.1056/NEJM197511132932004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Fatkin D, MacRae C, Sasaki T, Wolff MR, Porcu M, Frenneaux M, Atherton J, Vidaillet HJ, Jr., Spudich S, De Girolami U, et al. Missense mutations in the rod domain of the lamin A/C gene as causes of dilated cardiomyopathy and conduction-system disease. N Engl J Med. 1999;341:1715–24. doi: 10.1056/NEJM199912023412302. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Bonne G, Mercuri E, Muchir A, Urtizberea A, Bécane HM, Recan D, Merlini L, Wehnert M, Boor R, Reuner U, et al. Clinical and molecular genetic spectrum of autosomal dominant Emery-Dreifuss muscular dystrophy due to mutations of the lamin A/C gene. Ann Neurol. 2000;48:170–80. doi: 10.1002/1531-8249(200008)48:2<170::AID-ANA6>3.0.CO;2-J. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Muchir A, Bonne G, van der Kooi AJ, van Meegen M, Baas F, Bolhuis PA, de Visser M, Schwartz K. Identification of mutations in the gene encoding lamins A/C in autosomal dominant limb girdle muscular dystrophy with atrioventricular conduction disturbances (LGMD1B) Hum Mol Genet. 2000;9:1453–9. doi: 10.1093/hmg/9.9.1453. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Bione S, Maestrini E, Rivella S, Mancini M, Regis S, Romeo G, Toniolo D. Identification of a novel X-linked gene responsible for Emery-Dreifuss muscular dystrophy. Nat Genet. 1994;8:323–7. doi: 10.1038/ng1294-323. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Talkop UA, Talvik I, Sõnajalg M, Sibul H, Kolk A, Piirsoo A, Warzok R, Wulff K, Wehnert MS, Talvik T. Early onset of cardiomyopathy in two brothers with X-linked Emery-Dreifuss muscular dystrophy. Neuromuscul Disord. 2002;12:878–81. doi: 10.1016/S0960-8966(02)00134-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Astejada MN, Goto K, Nagano A, Ura S, Noguchi S, Nonaka I, Nishino I, Hayashi YK. Emerinopathy and laminopathy clinical, pathological and molecular features of muscular dystrophy with nuclear envelopathy in Japan. Acta Myol. 2007;26:159–64. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Ozawa R, Hayashi YK, Ogawa M, Kurokawa R, Matsumoto H, Noguchi S, Nonaka I, Nishino I. Emerin-lacking mice show minimal motor and cardiac dysfunctions with nuclear-associated vacuoles. Am J Pathol. 2006;168:907–17. doi: 10.2353/ajpath.2006.050564. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Taylor MR, Slavov D, Gajewski A, Vlcek S, Ku L, Fain PR, Carniel E, Di Lenarda A, Sinagra G, Boucek MM, et al. Familial Cardiomyopathy Registry Research Group Thymopoietin (lamina-associated polypeptide 2) gene mutation associated with dilated cardiomyopathy. Hum Mutat. 2005;26:566–74. doi: 10.1002/humu.20250. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Gotic I, Leschnik M, Kolm U, Markovic M, Haubner BJ, Biadasiewicz K, Metzler B, Stewart CL, Foisner R. Lamina-associated polypeptide 2alpha loss impairs heart function and stress response in mice. Circ Res. 2010;106:346–53. doi: 10.1161/CIRCRESAHA.109.205724. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Gotic I, Foisner R. Multiple novel functions of lamina associated polypeptide 2α in striated muscle. Nucleus. 2010;1:397–401. doi: 10.4161/nucl.1.5.12394. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Shin JY, Méndez-López I, Wang Y, Hays AP, Tanji K, Lefkowitch JH, Schulze PC, Worman HJ, Dauer WT. Lamina-associated polypeptide-1 interacts with the muscular dystrophy protein emerin and is essential for skeletal muscle maintenance. Dev Cell. 2013;26:591–603. doi: 10.1016/j.devcel.2013.08.012. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Shin JY, Dauer WT, Worman HJ. Lamina-associated polypeptide 1: Protein interactions and tissue-selective functions. Semin Cell Dev Biol. 2014 doi: 10.1016/j.semcdb.2014.01.010. In press. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Senior A, Gerace L. Integral membrane proteins specific to the inner nuclear membrane and associated with the nuclear lamina. J Cell Biol. 1988;107:2029–36. doi: 10.1083/jcb.107.6.2029. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Martin L, Crimaudo C, Gerace L. cDNA cloning and characterization of lamina-associated polypeptide 1C (LAP1C), an integral protein of the inner nuclear membrane. J Biol Chem. 1995;270:8822–8. doi: 10.1074/jbc.270.15.8822. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Foisner R, Gerace L. Integral membrane proteins of the nuclear envelope interact with lamins and chromosomes, and binding is modulated by mitotic phosphorylation. Cell. 1993;73:1267–79. doi: 10.1016/0092-8674(93)90355-T. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Goodchild RE, Dauer WT. The AAA+ protein torsinA interacts with a conserved domain present in LAP1 and a novel ER protein. J Cell Biol. 2005;168:855–62. doi: 10.1083/jcb.200411026. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Kim CE, Perez A, Perkins G, Ellisman MH, Dauer WT. A molecular mechanism underlying the neural-specific defect in torsinA mutant mice. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2010;107:9861–6. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0912877107. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Santos M, Rebelo S, Van Kleeff PJ, Kim CE, Dauer WT, Fardilha M, da Cruz E Silva OA, da Cruz E Silva EF. The nuclear envelope protein, LAP1B, is a novel protein phosphatase 1 substrate. PLoS One. 2013;8:e76788. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0076788. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Agah R, Frenkel PA, French BA, Michael LH, Overbeek PA, Schneider MD. Gene recombination in postmitotic cells. Targeted expression of Cre recombinase provokes cardiac-restricted, site-specific rearrangement in adult ventricular muscle in vivo. J Clin Invest. 1997;100:169–79. doi: 10.1172/JCI119509. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Aanhaanen WT, Boukens BJ, Sizarov A, Wakker V, de Gier-de Vries C, van Ginneken AC, Moorman AF, Coronel R, Christoffels VM. Defective Tbx2-dependent patterning of the atrioventricular canal myocardium causes accessory pathway formation in mice. J Clin Invest. 2011;121:534–44. doi: 10.1172/JCI44350. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Cheng L, Ding G, Qin Q, Huang Y, Lewis W, He N, Evans RM, Schneider MD, Brako FA, Xiao Y, et al. Cardiomyocyte-restricted peroxisome proliferator-activated receptor-delta deletion perturbs myocardial fatty acid oxidation and leads to cardiomyopathy. Nat Med. 2004;10:1245–50. doi: 10.1038/nm1116. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Muchir A, Pavlidis P, Decostre V, Herron AJ, Arimura T, Bonne G, Worman HJ. Activation of MAPK pathways links LMNA mutations to cardiomyopathy in Emery-Dreifuss muscular dystrophy. J Clin Invest. 2007;117:1282–93. doi: 10.1172/JCI29042. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Muchir A, Pavlidis P, Bonne G, Hayashi YK, Worman HJ. Activation of MAPK in hearts of EMD null mice: similarities between mouse models of X-linked and autosomal dominant Emery Dreifuss muscular dystrophy. Hum Mol Genet. 2007;16:1884–95. doi: 10.1093/hmg/ddm137. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Muchir A, Shan J, Bonne G, Lehnart SE, Worman HJ. Inhibition of extracellular signal-regulated kinase signaling to prevent cardiomyopathy caused by mutation in the gene encoding A-type lamins. Hum Mol Genet. 2009;18:241–7. doi: 10.1093/hmg/ddn343. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Wu W, Muchir A, Shan J, Bonne G, Worman HJ. Mitogen-activated protein kinase inhibitors improve heart function and prevent fibrosis in cardiomyopathy caused by mutation in lamin A/C gene. Circulation. 2011;123:53–61. doi: 10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.110.970673. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Muchir A, Reilly SA, Wu W, Iwata S, Homma S, Bonne G, Worman HJ. Treatment with selumetinib preserves cardiac function and improves survival in cardiomyopathy caused by mutation in the lamin A/C gene. Cardiovasc Res. 2012;93:311–9. doi: 10.1093/cvr/cvr301. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Muchir A, Wu W, Choi JC, Iwata S, Morrow J, Homma S, Worman HJ. Abnormal p38α mitogen-activated protein kinase signaling in dilated cardiomyopathy caused by lamin A/C gene mutation. Hum Mol Genet. 2012;21:4325–33. doi: 10.1093/hmg/dds265. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Wu W, Iwata S, Homma S, Worman HJ, Muchir A. Depletion of extracellular signal-regulated kinase 1 in mice with cardiomyopathy caused by lamin A/C gene mutation partially prevents pathology before isoenzyme activation. Hum Mol Genet. 2014;23:1–11. doi: 10.1093/hmg/ddt387. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Nikolova V, Leimena C, McMahon AC, Tan JC, Chandar S, Jogia D, Kesteven SH, Michalicek J, Otway R, Verheyen F, et al. Defects in nuclear structure and function promote dilated cardiomyopathy in lamin A/C-deficient mice. J Clin Invest. 2004;113:357–69. doi: 10.1172/JCI200419448. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Arimura T, Helbling-Leclerc A, Massart C, Varnous S, Niel F, Lacène E, Fromes Y, Toussaint M, Mura AM, Keller DI, et al. Mouse model carrying H222P-Lmna mutation develops muscular dystrophy and dilated cardiomyopathy similar to human striated muscle laminopathies. Hum Mol Genet. 2005;14:155–69. doi: 10.1093/hmg/ddi017. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Mounkes LC, Kozlov SV, Rottman JN, Stewart CL. Expression of an LMNA-N195K variant of A-type lamins results in cardiac conduction defects and death in mice. Hum Mol Genet. 2005;14:2167–80. doi: 10.1093/hmg/ddi221. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Cattin ME, Bertrand AT, Schlossarek S, Le Bihan MC, Skov Jensen S, Neuber C, Crocini C, Maron S, Lainé J, Mougenot N, et al. Heterozygous LmnadelK32 mice develop dilated cardiomyopathy through a combined pathomechanism of haploinsufficiency and peptide toxicity. Hum Mol Genet. 2013;22:3152–64. doi: 10.1093/hmg/ddt172. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Melcon G, Kozlov S, Cutler DA, Sullivan T, Hernandez L, Zhao P, Mitchell S, Nader G, Bakay M, Rottman JN, et al. Loss of emerin at the nuclear envelope disrupts the Rb1/E2F and MyoD pathways during muscle regeneration. Hum Mol Genet. 2006;15:637–51. doi: 10.1093/hmg/ddi479. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Worman HJ. Nuclear lamins and laminopathies. J Pathol. 2012;226:316–25. doi: 10.1002/path.2999. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Brüning JC, Michael MD, Winnay JN, Hayashi T, Hörsch D, Accili D, Goodyear LJ, Kahn CR. A muscle-specific insulin receptor knockout exhibits features of the metabolic syndrome of NIDDM without altering glucose tolerance. Mol Cell. 1998;2:559–69. doi: 10.1016/S1097-2765(00)80155-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Beedle AM, Turner AJ, Saito Y, Lueck JD, Foltz SJ, Fortunato MJ, Nienaber PM, Campbell KP. Mouse fukutin deletion impairs dystroglycan processing and recapitulates muscular dystrophy. J Clin Invest. 2012;122:3330–42. doi: 10.1172/JCI63004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Gaussin V, Van de Putte T, Mishina Y, Hanks MC, Zwijsen A, Huylebroeck D, Behringer RR, Schneider MD. Endocardial cushion and myocardial defects after cardiac myocyte-specific conditional deletion of the bone morphogenetic protein receptor ALK3. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2002;99:2878–83. doi: 10.1073/pnas.042390499. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Zammit PS, Kelly RG, Franco D, Brown N, Moorman AF, Buckingham ME. Suppression of atrial myosin gene expression occurs independently in the left and right ventricles of the developing mouse heart. Dev Dyn. 2000;217:75–85. doi: 10.1002/(SICI)1097-0177(200001)217:1<75::AID-DVDY7>3.0.CO;2-L. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Kayman-Kurekci G, Talim B, Korkusuz P, Sayar N, Sarioglu T, Oncel I, Sharafi P, Gundesli H, Balci-Hayta B, Purali N, et al. Mutation in TOR1AIP1 encoding LAP1B in a form of muscular dystrophy: A novel gene related to nuclear envelopathies. Neuromuscul Disord. 2014 doi: 10.1016/j.nmd.2014.04.007. In press. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Cance WGCN, Worman HJ, Blobel G, Cordon-Cardo C. Expression of the nuclear lamins in normal and neoplastic human tisses. J Exp Clin Cancer Res. 1992;11:233–46. [Google Scholar]

- 46.Laemmli UK. Cleavage of structural proteins during the assembly of the head of bacteriophage T4. Nature. 1970;227:680–5. doi: 10.1038/227680a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.