Abstract

Objectives

Surrogates involved in decisions to limit life-sustaining treatment for a loved one in the intensive care unit (ICU) are at increased risk for adverse psychological outcomes lasting months to years after the ICU experience. Post-ICU interventions to reduce surrogate distress have not been developed. We sought to 1) describe a conceptual framework underlying the beneficial mental health effects of storytelling and 2) present formative work developing a storytelling intervention to reduce distress for recently bereaved surrogates.

Methods

An interdisciplinary team conceived the idea for a storytelling intervention based upon evidence from narrative theory that storytelling reduces distress from traumatic events through emotional disclosure, cognitive processing, and social connections. We developed an initial storytelling guide based upon this theory and the clinical perspectives of team members. We then conducted a case series with recently bereaved surrogates to iteratively test and modify the guide.

Results

The storytelling guide covered three key domains of the surrogate's experience of the patient's illness and death: antecedents, ICU experience, and aftermath. The facilitator focused on parts of the story that appeared to generate strong emotions and used non-judgmental statements to attend to these emotions. Between September 2012 and May 2013 we identified 28 eligible surrogates from 1 medical ICU and consented 20 for medical record review and recontact; 10 became eligible of whom 6 consented and completed the storytelling intervention. The single-session storytelling intervention lasted 40-92 minutes. All storytelling participants endorsed the intervention as acceptable, and 5 of 6 reported that it was helpful.

Significance of Results

Surrogate storytelling is an innovative and acceptable post-ICU intervention for recently bereaved surrogates and should be evaluated further.

Keywords: decision making, intensive care unit, terminal care, family members, mental disorders, role of surrogates

Introduction

One in 5 Americans die in or shortly after discharge from an intensive care unit (ICU)(Angus, Barnato et al. 2004), and the majority of these deaths are preceded by a decision to limit life-sustaining therapy. (Prendergast and Luce 1997; Prendergast and Puntillo 2002) Clinicians ask family members to participate in these decisions as surrogate decision makers, guided by their understanding of the patient's values and wishes. (Berger, DeRenzo et al. 2008) This process places a burden on surrogates (Vig, Taylor et al. 2006; Vig, Starks et al. 2007; Braun, Beyth et al. 2008; Braun, Naik et al. 2009; Wendler and Rid 2011; Schenker, Crowley-Matoka et al. 2012) and has long-lasting adverse mental health consequences, including post-traumatic stress disorder (PTSD), anxiety, depression, and persistent complex bereavement disorder. (Pochard, Azoulay et al. 2001; Jones, Skirrow et al. 2004; Azoulay, Pochard et al. 2005; Lautrette, Darmon et al. 2007; Anderson, Arnold et al. 2008; Siegel, Hayes et al. 2008; Anderson, Arnold et al. 2009; Gries, Engelberg et al. 2010; Kross, Engelberg et al. 2011). In one study conducted in 21 French ICUs, 81.8% of surrogates involved in a decision to limit life-sustaining treatment exhibited PTSD symptoms 90 days after a loved one's death that are perceived as distinct from normal processes of grief and bereavement. (Azoulay, Pochard et al. 2005) In 2010 a task force of the Society of Critical Care Medicine proposed a new term for the cluster of symptoms experienced by families after an ICU experience: Postintensive Care Syndrome – Family (PICS-F). (Davidson, Jones et al. 2012)

Increasing recognition of surrogate distress has led to the promotion of more family-centered treatment for dying patients in the ICU, including interventions to support surrogates. (Thompson, Cox et al. 2004; Truog, Campbell et al. 2008) To date, these interventions have principally fallen into one of two categories: 1) decision support (i.e., informational pamphlets, pen-and-paper decision aids, or values clarification exercises) (Scheunemann, McDevitt et al. ; Mitchell, Tetroe et al. 2001; Lautrette, Darmon et al. 2007; Kryworuchko 2009; Peigne, Chaize et al. 2011; Cox, Lewis et al. 2012) or 2) psychological and communication support from an ICU professional (i.e., structured family meeting or additional family support from a patient navigator, nurse or social worker). (McCormick, Curtis et al. ; Scheunemann, McDevitt et al. ; Murphy, Kreling et al. 2000) Such efforts conceptualize the problem as one that requires better prognostic information, values clarification, and clinician-surrogate communication in the ICU, and they have shown some benefit. (Scheunemann, McDevitt et al.) For example, a proactive communication strategy that included longer family conferences with more time for family members to talk and providing family members with a brochure on bereavement decreased PTSD, anxiety, and depression at 90 days by roughly one-third in a French cohort. (Lautrette, Darmon et al. 2007) However, despite the substantial relative reduction, prevalence rates of PTSD (45%), anxiety (45%), and depression (29%) symptoms in the intervention group remained high. Furthermore, implementation and scaling of such interventions may prove difficult. A recent multicenter trial of a quality improvement strategy to improve end-of-life care in the ICU through clinician education, local champions, academic detailing, clinician feedback of quality data, and system supports did not improve family outcomes. (Curtis, Nielsen et al. 2011)

Post-ICU interventions offer a promising new frontier for reducing PICS-F. (Davidson, Jones et al. 2012) Such interventions may provide additional benefit by allowing family members at the greatest risk of long-term psychological sequelae to process their experience as surrogates in the acute bereavement period. However, to the best of our knowledge, no post-ICU interventions have been systematically evaluated for their ability to reduce adverse mental health consequences among family members involved in decisions to limit life-sustaining treatment. We therefore sought to develop and pilot test a novel intervention in the early bereavement period for this high-risk population. Based on data from our prior descriptive work (Schenker, Crowley-Matoka et al. 2012), we posited that allowing surrogates to tell the story of their involvement in the decision to limit life-sustaining treatment for a loved one in the ICU would help them to find meaning in this difficult experience, preempt rumination and behavioral avoidance, and promote sleep quality, thereby facilitating the normal work of acute grief and improving mental health outcomes. Our storytelling intervention draws on the theory of narrative ethics and prior empiric work demonstrating the health benefits of narrative self-disclosure after stressful experiences. (Pennebaker, Barger et al. 1989; White and Epston 1990; Pennebaker, Barger et al. 1989; Charon and Montello 2002; Niederhoffer and Pennebaker 2002; Noble and Jones 2005).

In this article, we discuss the conceptual framework underlying the beneficial effects of storytelling. We then present our formative work developing a storytelling intervention for recently bereaved surrogates who participated in life-sustaining treatment decisions. We describe the final components of our intervention and report initial data on feasibility and acceptability from an open-label case series.

Methods

Conceptual Framework

The conceptual framework of narrative ethics posits that the act of telling one's story allows patients and families to understand events in ways that make it possible to process them and move on.(Charon and Montello 2002) As the psychologist Jerome Bruner argued, we use stories to help us understand our plight as humans and what Aristotle termed “peripeteia,” or sudden reversals of our circumstances.(Bruner 2002) Stories help us deal with surprises and upsets, make meaning out of chaos, clarify values, and build connections between past events and the future. As Rita Charon posits in her seminal work Narrative Medicine, stories combat loneliness and build communities, as we “discover the deep, nourishing bonds that hold us together.” We are all storytellers, continually creating and reshaping our identities in the tales we tell each other. (Charon 2006)

An expanding body of research supports the benefits of storytelling on physical and emotional health. Writing about a broad range of emotional topics over multiple sessions has been associated with improved immune responses among healthy students receiving hepatitis B vaccinations (Petrie, Booth et al. 1995) and among patients with HIV. (Petrie, Fontanilla et al. 2004) After loss or traumatic experiences, similar narrative interventions have been associated with fewer physician visits and improved subjective health.(Pennebaker, Barger et al. 1989; Greenberg, Wortman et al. 1996; Cameron and Nicholls 1998) Stories have also been used successfully to bridge cultural divides between physicians and patients and to combat racial/ethnic disparities in health behaviors and outcomes.(Larkey and Gonzalez 2007; Curtis and White 2008; Larkey, Lopez et al. 2009; Houston, Allison et al. 2011) For example, in one study an interactive storytelling intervention distributed on DVDs produced significant improvements in medication adherence and blood pressure control among African American patients with hypertension. (Houston, Allison et al. 2011)

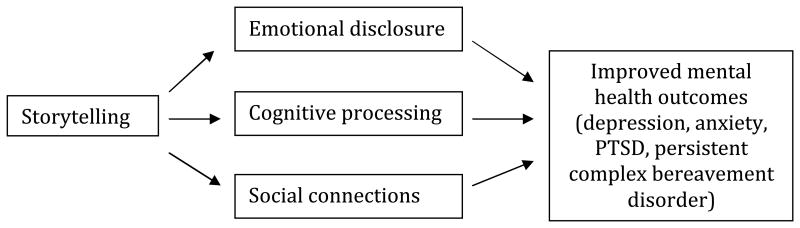

Three theoretical processes purport to explain the salutary effects of storytelling after traumatic events (see Figure 1).(Niederhoffer and Pennebaker 2002) The emotional disclosure framework posits that the benefit of storytelling derives from the opportunity to disclose emotional trauma, counteracting the psychological stress of inhibiting important thoughts and feelings.(Pennebaker 1989; Pennebaker, Barger et al. 1989; Trau and Deighton 1999) Further examination of the storytelling experience has revealed the importance of cognitive processing, i.e., providing needed closure, order and a sense of control through the construction of a coherent narrative about a stressful life event.(Clark 1993; Pennebaker, Mayne et al. 1997) Finally, storytelling is an opportunity to establish richer social connections through sharing difficult experiences, counteracting the feelings of loneliness and social isolation associated with poor mental health.(Holahan, Moos et al. 1996) Mechanistically, we posited that these three processes may preempt the rumination and behavioral avoidance of reminders of the deceased that are core features of persistent complex bereavement disorder (ref DSM-5). Thus, a storytelling intervention may allow surrogates to articulate painful feelings associated with a decision to limit life sustaining treatment and their loved one's death that may be shunted aside in the acute bereavement period. Decreasing dysphoric arousal could in turn facilitate better sleep quality, thereby reducing an important risk factor for the development of subsequent mental disorders.

Figure 1. Proposed mechanisms to explain the beneficial mental health effects of storytelling.

In summary, supported by a strong conceptual framework with applicability to recently bereaved surrogates, storytelling interventions have shown benefit in multiple clinical research settings. However, prior interventions have not been tailored to the unique needs and circumstances of surrogates in the acute post-ICU bereavement period or tested in this vulnerable population. We therefore sought to develop a novel storytelling intervention for recently bereaved surrogates who participated in a decision to limit life-sustaining treatment for a loved one in the ICU.

Intervention Content and Development

We assembled an interdisciplinary development team with experts from the fields of critical care, palliative care, health services research, psychiatry, psychology, decision science, social work, and epidemiology and biostatistics. The team provided expertise in the surrogate experience, mood disorders, bereavement, and behavioral intervention research.

Overview

We conceptualized the intervention as an opportunity for surrogates to tell the story of their experience participating in a decision to limit life-sustaining treatment for a loved one in the ICU within 2-4 weeks of the patient's death. We chose this time frame to balance our likelihood of affecting subsequent development of adverse mental health outcomes while not posing too great a burden in the immediate bereavement period. We chose a single, rather than a multi-session intervention in order to maximize feasibility and scalability in this timeframe. We initially designed the storytelling session as a face-to-face intervention in order to ensure the facilitator's ability to recognize and respond to surrogates' emotions, though we are now developing a telephone-based version (see Discussion below). We offered to conduct the storytelling session either in the surrogate's home or in a private research office to ensure participant comfort and convenience. In this formative work, the principal investigator (AB) conducted all intervention sessions because we viewed it as critical to have an expert facilitator as we worked on intervention development and refinement. After each session, the facilitator debriefed the subject regarding the experience of study participation, including questions about burdensomeness, acceptability, and perceived value.

Eliciting the Story

The initial semi-structured guide included questions to elicit three key domains of the story: the antecedents (the illness that brought the patient to the ICU), the ICU experience (including the decision to limit life sustaining treatment and the patient's death) and the aftermath (the surrogate's feelings or thoughts about the decedent, the ICU experience, and the decision to limit life-sustaining treatment). We conceptualized the story as a narrative with multiple characters - including the decedent and other decision makers - with relationships to the surrogate. Because some surrogates may not view themselves as having “made” a decision (Schenker, Crowley-Matoka et al. 2012), we used general probes to elicit this experience, such as “At what point did you realize that your [relationship] might not survive?” and “Were there any major decisions that had to be made once you realized that?”

Rather than forcing a linear narrative, our goal was to create a safe setting for surrogates to describe experiences and feelings that they may have pushed aside in the acute bereavement period. Historical events provided a scaffold for the interview guide, but we iteratively modified the guide to preferentially probe elements of the story with the strongest emotional valence, identified using non-verbal cues (crying, changes in voice). We conceptualized the intensity of emotion during the storytelling interview as a key active ingredient of the intervention and therefore used probes to elicit how events affected surrogates, rather than the historical events themselves. Examples of these types of probes include “Tell me how that experience was for you,” and “What was it like for you to see your [loved one] like that?”

Emotional Disclosure and Distress

Throughout the storytelling experience, the facilitator attended to surrogate emotions using NURSE statements (Naming, Understanding, Respecting, Supporting and Exploring) (Back A 2009) Definitions adapted from prior work (Pollak, Arnold et al. 2007; Back A 2009) and sample probes for each type of NURSE statement are shown in Table 2. Emotion handling statements were non-judgmental and did not presume that surrogates were experiencing any particular emotion. Rather, the facilitator sought to provide direct support for the surrogate and facilitate the process of acute grief by responding to empathic opportunities.

Table 2. Emotion handling during storytelling.

| Emotion handling skill | Definition | Examples |

|---|---|---|

| Naming | Includes restating / summarizing when the surrogate uses an emotion word or using verbal and non-verbal cues to identify an unspoken emotion. | “It sounds like that was really frustrating for you.” “Some people in this situation would be angry.” |

| Understanding | Includes empathizing with surrogate emotions and may require exploration, active listening, and use of silence. Paradoxically, saying “I cannot imagine what it is like to X” is a good way to show your understanding. | “I think I understand you as saying you feel some guilt about the decision to withdraw life-support.” “That must have been so difficult to say goodbye.” |

| Respecting | Acknowledging (e.g., naming and understanding) is the first step in respecting an emotion. Praising the surrogate's coping skills is another good way to show respect. | “I am very impressed with how you followed your father's wishes.” “It sounds like you were really watching over him.” |

| Supporting | This can be an expression of concern, articulating understanding of the surrogate's situation, a willingness to help, or acknowledging the surrogate's efforts to cope. | “I am impressed by how well you were able to cope with so much internal conflict.” |

| Exploring | Let the surrogate talk about what they went through (and are going through in the aftermath of the decision) by exploring their story. | “You said this was a living hell – tell me more about what you are feeling now.” “Tell me what you mean when you say that.” |

We also asked surrogates to rate their distress using the subjective units of distress (SUDS) 0-100 scale (Tanner 2012), with 0 being completely calm and 100 being the worst distress that a participant could imagine, before, during, and after the storytelling session. The purpose of eliciting SUDS scores was to provide feedback to the participant and facilitator about the strength of the surrogates' emotional experience.

Cognitive Processing and Social Connection

To facilitate cognitive processing and social connections through storytelling, we also asked participants to reflect on what they learned from the experience of being a surrogate in the ICU and what advice they might have for others. Probes to encourage meaning-making included: “What have you shared with other people about this experience?” “Who needs to hear your story?” “What advice might you have for others in similar situations?” “What did you learn through this experience?” “What do you wish you had known beforehand?” and “What do you wish you had done differently?”

Closure

At the end of the storytelling session, the facilitator identified key themes that emerged and drew attention to positive aspects of the surrogate's experience, delivering a validation statement to show respect for the surrogates' role. Often this was that s/he was an attentive caretaker. For example, “I just, I can't tell you how impressed I am with your willingness to tell us this story, but even more so, the respect I have for you for the way that you took care of your brother.” The facilitator expressed thanks and an understanding of how difficult it is to share one's story. Finally, the facilitator reviewed a pamphlet with community bereavement resources with the subject and encouraged self-care.

Participants and Recruitment

We conducted a case series in a single medical ICU in our tertiary care academic medical center. We included recently-bereaved surrogates who participated in a decision to limit life-sustaining treatment that resulted in the inpatient death of an adult ICU patient. Surrogates who were present in the ICU during recruitment hours met initial (screening) eligibility criteria if they were the family member or friend of a patient who lacked capacity and for whom the ICU team anticipated a family meeting about life-sustaining treatment decisions. We included only surrogates who were able to participate in English. To ensure our ability to conduct sessions face-to-face, we excluded surrogates who did not live within 2 hours' driving distance from Pittsburgh. Based on prior experience (Schenker, Crowley-Matoka et al. 2012; Schenker, White et al. 2013), we approached family members prior to a decision to limit life-sustaining treatment in order to build sufficient rapport to recruit surrogates of patients who later died. On this approach, we explained the study in general terms and obtained proxy consent for medical record review to assess eligibility and re-contact. For surrogates who met subsequent (storytelling) eligibility criteria (participation in a life-sustaining treatment decision for an incapacitated ICU patient who died in the hospital), we mailed a condolence letter one week after the patient's death, followed by a telephone call approximately two weeks after the patient's death. At this time, surrogates were given the opportunity to learn more about the study and schedule a storytelling visit. We obtained consent to audio-record the session.

Iterative Modification

We iteratively modified the storytelling guide during multiple team meetings during which team members listened to audio-recordings of role-played storytelling sessions (between a team member and surrogates played by standardized patients, palliative and critical care fellows, and other members of the research team) and, later, to six real storytelling sessions in the case series of study participants. The final guide clarifies key characteristics of the storytelling intervention and distinctions between story elicitation and psychotherapy (see Table 1). We include the final storytelling intervention guide is as an appendix.

Table 1. Key characteristics of the storytelling intervention.

| What it is | What it is not |

|---|---|

|

| |

An elicitation of the surrogate's story of their own experience of the patient's illness and death in the ICU. The elements of the story include:

Open-ended questions / probes Reflective summary statements Emotion-handling statements (NURSE) Elicitation focuses on the “hot cognitions” – i.e., those areas of the story that appear to generate strong emotion, as reflected by verbal and non-verbal signals from the subject. At these points, the SUDS are assessed. |

Psychotherapy. Empathic listening is a necessary but insufficient component of all forms of psychotherapy, including interpersonal psychotherapy, cognitive behavioral therapy, and problem solving therapy. Our intervention will not involve the other key components of psychotherapy:

|

Do not assume the subject conceptualizes the process as involving active decisions

Human Subjects Protections

The University of Pittsburgh institutional review board reviewed and approved the study protocol. All subjects provided written informed consent for participation. Subjects completing a storytelling interview received $50 payment for their time.

Results

Enrollment

We found that 28/61 (46%) of screened subjects met our initial (screening) eligibility criteria. The most common reasons for ineligibility were that the surrogate was not available during recruitment hours (45%) or that the surrogate lived more than 2 hours' drive from Pittsburgh (30%).

Of the 28 surrogates who met initial eligibility criteria, 20 (71%) consented to be followed. Surrogates who declined to participate most commonly cited feeling overwhelmed by the ICU experience. Based upon medical record review, 10 of 20 met subsequent (storytelling) eligibility criteria for the intervention phase, 6 of whom completed the storytelling intervention.

Characteristics of Participants

Surrogate participants were the spouse (2 of 6) parent (2 of 6) or sibling (2 of 6) of a deceased patient. Two-thirds (4 of 6) were women, consistent with the gender demographics of surrogates nationally. Their mean age was 54 years old and all were Caucasian.

Location and Timing of Storytelling Sessions

Storytelling sessions most commonly took place in the surrogate's home (3 of the 6 participants), while 2 participants chose a private research office and 1 chose a public library near their home. Sessions took place on average 37 days after the patient's death (range 22-70). Storytelling sessions lasted an average of 62 minutes (range 40-92).

Emotional Distress

Subjective Units of Distress (SUDS) scores before and after the storytelling sessions are shown in Table 3. Post-intervention SUDS ranged from 5-60 and were no higher than scores before the intervention.

Table 3. Subjective Units of Distress (SUDS) Before and After Storytelling.

| Participant Number | Before* | After |

|---|---|---|

|

| ||

| 1 | -- | 10 |

| 2 | 30 | 20-30 |

| 3 | 60 | 50-60 |

| 4 | 50 | 30 |

| 5 | 30 | 30 |

| 6 | -- | 5 |

Missing data indicates the SUDS was not asked.

Acceptability

In debriefing interviews after each intervention session, all subjects endorsed acceptability; 5/6 participants in the storytelling intervention reported that it was helpful to talk about their experience; 1/6 said he enjoyed the opportunity to “help others” through his participation. although he did not himself think that he needed any help because he had experience dealing with trauma. One participant said “I think that – that helped me to talk to somebody that wasn't judging me or something,” later noting “there's a lot of things I didn't even know that were hurting me, you know? This is feeling good.” Another subject said “for me, it helps to talk about it and to tell the story, because it's my way of going through it again … I think sometimes you have to look back and understand and walk through it to get past and move on.”

Discussion

In this formative study, we developed and pilot-tested a novel storytelling intervention for recently bereaved surrogates who faced life sustaining treatment decisions for a loved one in the ICU, a population known to have adverse psychological outcomes. Our intervention was informed by a conceptual model and related empirical evidence supporting the beneficial mental effects of storytelling after traumatic events. Our storytelling guide facilitated elicitation of the surrogate's story through active, empathic listening and probing of emotional responses. Recruitment was feasible and participants overwhelmingly viewed the intervention as helpful.

While increased understanding of the challenges faced by surrogates has resulted in more support for family members facing decisions in the ICU (Davidson, Powers et al. 2007), little attention has been paid to the needs of surrogates after a decision is made to limit life sustaining treatment. Post-ICU interventions represent an important opportunity for selective prevention to improve mental health outcomes and reduce disability in this vulnerable and high-risk group. We chose a storytelling intervention based, in part, on prior descriptive work in which storytelling emerged as a key coping mechanism amongst surrogates in the ICU (Schenker, Crowley-Matoka et al. 2012). Comments from participants after each session in the current study support our conceptual model of storytelling as an intervention that facilitates emotional disclosure and cognitive processing after traumatic events. We also noted that storytelling sessions allowed participants to articulate feelings and memories from the ICU that they may have ignored in the weeks since a loved one's death, thereby facilitating the work of normal grieving.

A further consideration at this stage was to ensure that our intervention is both practical and sustainable. We posited that a single storytelling session conducted in the surrogate's home may be less burdensome, stigmatizing and/or costly than other potential preventive mental health strategies such as psychotherapy or medication. Intervention expenses may be offset by a decrease in downstream healthcare utilization, as demonstrated in a prior ICU-based intervention study in which surrogate mental healthcare utilization was halved in the intervention group. (Lautrette, Darmon et al. 2007) However, it is possible that a multi-session intervention may be more effective; additional work is needed to determine the optimal storytelling “dose.”

While we conducted all initial sessions in person, we are now developing plans to pilot the surrogate storytelling intervention by telephone, supported by accumulating evidence for the beneficial effects of telephonic mental health interventions in other settings. (Rollman, Belnap et al. 2005; Rollman, Belnap et al. 2009) Given the significant proportion of surrogates who live far away from the medical center where their loved one died, we anticipate that a telephone-based intervention will greatly expand our potential reach. In the “real world,” storytelling sessions could be conducted by a social worker, nurse or chaplain with ICU and/or bereavement experience.

Our work has limitations. We were unable to recruit a racially/ethnically diverse group of surrogates for this pilot phase. Additional work is needed to ensure that our intervention is safe and acceptable to participants from diverse racial/ethnic groups. Because our aim was to develop the storytelling intervention, we found it infeasible to simultaneously train an interventionist; the principal investigator conducted all intervention sessions (AB). Our intervention manual, developed by an experienced and interdisciplinary group through an iterative process of conducting, reviewing and critiquing these storytelling sessions, and including exemplar interviews conducted by a skilled clinician, provides an important starting point for future interventionist training.

In summary, we describe an innovative post-ICU intervention designed by a multidisciplinary team and refined through an open-label case series of recently bereaved surrogate decision makers. This work supports further evaluation of the safety and acceptability of the surrogate storytelling intervention in a phase II study and, ultimately, a larger randomized trial to assess efficacy.

Acknowledgments

Supported by the National Palliative Care Research Center (NPCRC), P30 MH090333, the National Center For Advancing Translational Sciences of the National Institutes of Health (KL2TR000146), and the University of Pittsburgh Department of Medicine's Junior Scholar Award. The content is solely the responsibility of the authors and does not necessarily represent the official views of the National Institutes of Health.

References

- Anderson WG, Arnold RM, et al. Posttraumatic stress and complicated grief in family members of patients in the intensive care unit. J Gen Intern Med. 2008;23(11):1871–1876. doi: 10.1007/s11606-008-0770-2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Anderson WG, Arnold RM, et al. Passive decision-making preference is associated with anxiety and depression in relatives of patients in the intensive care unit. J Crit Care. 2009;24(2):249–254. doi: 10.1016/j.jcrc.2007.12.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Angus DC, Barnato AE, et al. Use of intensive care at the end of life in the United States: an epidemiologic study. Crit Care Med. 2004;32(3):638–643. doi: 10.1097/01.ccm.0000114816.62331.08. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Azoulay E, Pochard F, et al. Risk of post-traumatic stress symptoms in family members of intensive care unit patients. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 2005;171(9):987–994. doi: 10.1164/rccm.200409-1295OC. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Back A, A R, Tulsky J. Mastering Communication with Seriously Ill Patients. New York, NY: Cambridge University Press; 2009. [Google Scholar]

- Berger JT, DeRenzo EG, et al. Surrogate decision making: reconciling ethical theory and clinical practice. Ann Intern Med. 2008;149(1):48–53. doi: 10.7326/0003-4819-149-1-200807010-00010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Braun UK, Beyth RJ, et al. Voices of African American, Caucasian, and Hispanic surrogates on the burdens of end-of-life decision making. J Gen Intern Med. 2008;23(3):267–274. doi: 10.1007/s11606-007-0487-7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Braun UK, Naik AD, et al. Reconceptualizing the experience of surrogate decision making: reports vs genuine decisions. Ann Fam Med. 2009;7(3):249–253. doi: 10.1370/afm.963. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brehaut JC, O'Connor AM, et al. Validation of a decision regret scale. Med Decis Making. 2003;23(4):281–292. doi: 10.1177/0272989X03256005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bruner J, Charon R, Montello M. Stories Matter: The Role of Narrative in Medical Ethics. New York: Routledge; 2002. Narratives of Human Plight: A Conversation with Jerome Bruner; pp. 3–9. [Google Scholar]

- Cameron LD, Nicholls G. Expression of stressful experiences through writing: effects of a self-regulation manipulation for pessimists and optimists. Health Psychol. 1998;17(1):84–92. doi: 10.1037//0278-6133.17.1.84. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Charon R. Narrative Medicine. New York: Oxford University Press; 2006. The Sources of Narrative Medicine; p. 9. [Google Scholar]

- Charon R, Montello M, Charon R, Montello M. Stories Matter: The Role of Narrative in Medical Ethics. New York: Routledge; 2002. Memory and Anticipation: The Practice of Narrative Ethics; pp. ix–xii. [Google Scholar]

- Charon R, Montello M, editors. Stories Matter: The Role of Narrative in Medical Ethics. New York: Routledge; 2002. [Google Scholar]

- Clark LF. Stress and the cognitive-conversational benefits of social interaction. Journal of Social and Clinical Psychology. 1993;12:25–55. [Google Scholar]

- Cox CE, Lewis CL, et al. Development and pilot testing of a decision aid for surrogates of patients with prolonged mechanical ventilation. Crit Care Med. 2012;40(8):2327–2334. doi: 10.1097/CCM.0b013e3182536a63. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Curtis JR, Nielsen EL, et al. Effect of a quality-improvement intervention on end-of-life care in the intensive care unit: a randomized trial. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 2011;183(3):348–355. doi: 10.1164/rccm.201006-1004OC. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Curtis JR, White DB. Practical guidance for evidence-based ICU family conferences. Chest. 2008;134(4):835–843. doi: 10.1378/chest.08-0235. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Davidson JE, Jones C, et al. Family response to critical illness: postintensive care syndrome-family. Crit Care Med. 2012;40(2):618–624. doi: 10.1097/CCM.0b013e318236ebf9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Davidson JE, Jones C, et al. Family response to critical illness: Postintensive care syndrome-family. Crit Care Med. 2012;40(2) doi: 10.1097/CCM.0b013e318236ebf9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Davidson JE, Powers K, et al. Clinical practice guidelines for support of the family in the patient-centered intensive care unit: American College of Critical Care Medicine Task Force 2004-2005. Crit Care Med. 2007;35(2):605–622. doi: 10.1097/01.CCM.0000254067.14607.EB. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Greenberg MA, Wortman CB, et al. Emotional expression and physical health: revising traumatic memories or fostering self-regulation? J Pers Soc Psychol. 1996;71(3):588–602. doi: 10.1037//0022-3514.71.3.588. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gries CJ, Engelberg RA, et al. Predictors of symptoms of posttraumatic stress and depression in family members after patient death in the ICU. Chest. 2010;137(2):280–287. doi: 10.1378/chest.09-1291. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Holahan CJ, Moos RH, et al. Social support, coping strategies, and psychosocial adjustment to cardiac illness: Implications for assessment and prevention. Journal of Prevention and Intervention in the Community. 1996;13:33–52. [Google Scholar]

- Houston TK, Allison JJ, et al. Culturally appropriate storytelling to improve blood pressure: a randomized trial. Ann Intern Med. 2011;154(2):77–84. doi: 10.7326/0003-4819-154-2-201101180-00004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jones C, Skirrow P, et al. Post-traumatic stress disorder-related symptoms in relatives of patients following intensive care. Intensive Care Med. 2004;30(3):456–460. doi: 10.1007/s00134-003-2149-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kross EK, Engelberg RA, et al. ICU care associated with symptoms of depression and posttraumatic stress disorder among family members of patients who die in the ICU. Chest. 2011;139(4):795–801. doi: 10.1378/chest.10-0652. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kryworuchko J. Understanding the Options: Planning care for critically ill patients in the Intensive Care Unit 2009 [Google Scholar]

- Larkey LK, Gonzalez J. Storytelling for promoting colorectal cancer prevention and early detection among Latinos. Patient Educ Couns. 2007;67(3):272–278. doi: 10.1016/j.pec.2007.04.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Larkey LK, Lopez AM, et al. Storytelling for promoting colorectal cancer screening among underserved Latina women: a randomized pilot study. Cancer Control. 2009;16(1):79–87. doi: 10.1177/107327480901600112. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lautrette A, Darmon M, et al. A communication strategy and brochure for relatives of patients dying in the ICU. N Engl J Med. 2007;356(5):469–478. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa063446. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McCormick AJ, Curtis JR, et al. Improving social work in intensive care unit palliative care: results of a quality improvement intervention. J Palliat Med. 13(3):297–304. doi: 10.1089/jpm.2009.0204. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mitchell SL, Tetroe J, et al. A decision aid for long-term tube feeding in cognitively impaired older persons. J Am Geriatr Soc. 2001;49(3):313–316. doi: 10.1046/j.1532-5415.2001.4930313.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Murphy P, Kreling B, et al. Description of the SUPPORT intervention. Study to Understand Prognoses and Preferences for Outcomes and Risks of Treatments. J Am Geriatr Soc. 2000;48(5 Suppl):S154–161. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Niederhoffer K, Pennebaker J, Snyder C, Lopez S. Handbook of positive psychology. New York: Oxford University Press; 2002. Sharing one's story: On the benefits of writing or talking about emotional experience. [Google Scholar]

- Noble A, Jones C. Benefits of narrative therapy: holistic interventions at the end of life. Br J Nurs. 2005;14(6):330–333. doi: 10.12968/bjon.2005.14.6.17802. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Peigne V, Chaize M, et al. Important questions asked by family members of intensive care unit patients. Crit Care Med. 2011;39(6):1365–1371. doi: 10.1097/CCM.0b013e3182120b68. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pennebaker JW, Berkowitz L. Advances in Experimental and Social Psychology. New York: Academic Press; 1989. Confession, Inhibition, and Disease. [Google Scholar]

- Pennebaker JW, Barger SD, et al. Disclosure of traumas and health among Holocaust survivors. Psychosom Med. 1989;51(5):577–589. doi: 10.1097/00006842-198909000-00009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pennebaker JW, Mayne TJ, et al. Linguistic predictors of adaptive bereavement. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology. 1997;72:863–871. doi: 10.1037//0022-3514.72.4.863. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Petrie KJ, Booth RJ, et al. Disclosure of trauma and immune response to a hepatitis B vaccination program. J Consult Clin Psychol. 1995;63(5):787–792. doi: 10.1037//0022-006x.63.5.787. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Petrie KJ, Fontanilla I. Effect of written emotional expression on immune function in patients with human immunodeficiency virus infection: a randomized trial. Psychosom Med. 2004;66(2):272–275. doi: 10.1097/01.psy.0000116782.49850.d3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pochard F, Azoulay E, et al. Symptoms of anxiety and depression in family members of intensive care unit patients: ethical hypothesis regarding decision-making capacity. Crit Care Med. 2001;29(10):1893–1897. doi: 10.1097/00003246-200110000-00007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pollak KI, Arnold RM, et al. Oncologist communication about emotion during visits with patients with advanced cancer. J Clin Oncol. 2007;25(36):5748–5752. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2007.12.4180. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Prendergast TJ, Luce JM. Increasing incidence of withholding and withdrawal of life support from the critically ill. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 1997;155(1):15–20. doi: 10.1164/ajrccm.155.1.9001282. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Prendergast TJ, Puntillo KA. Withdrawal of life support: intensive caring at the end of life. JAMA. 2002;288(21):2732–2740. doi: 10.1001/jama.288.21.2732. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Prigerson HG, Maciejewski PK, et al. Inventory of Complicated Grief: a scale to measure maladaptive symptoms of loss. Psychiatry Res. 1995;59(1-2):65–79. doi: 10.1016/0165-1781(95)02757-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rollman BL, Belnap BH, et al. The Bypassing the Blues treatment protocol: stepped collaborative care for treating post-CABG depression. Psychosom Med. 2009;71(2):217–230. doi: 10.1097/PSY.0b013e3181970c1c. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rollman BL, Belnap BH, et al. A randomized trial to improve the quality of treatment for panic and generalized anxiety disorders in primary care. Arch Gen Psychiatry. 2005;62(12):1332–1341. doi: 10.1001/archpsyc.62.12.1332. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schenker Y, Crowley-Matoka M, et al. I don't want to be the one saying ‘we should just let him die’: intrapersonal tensions experienced by surrogate decision makers in the ICU. J Gen Intern Med. 2012;27(12):1657–1665. doi: 10.1007/s11606-012-2129-y. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schenker Y, White DB, et al. ”It hurts to know… and it helps: exploring how surrogates in the ICU cope with prognostic information. J Palliat Med. 2013;16(3):243–249. doi: 10.1089/jpm.2012.0331. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Scheunemann LP, McDevitt M, et al. Randomized, controlled trials of interventions to improve communication in intensive care: a systematic review. Chest. 139(3):543–554. doi: 10.1378/chest.10-0595. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Siegel MD, Hayes E, et al. Psychiatric illness in the next of kin of patients who die in the intensive care unit. Crit Care Med. 2008;36(6):1722–1728. doi: 10.1097/CCM.0b013e318174da72. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Snaith RP, Zigmond AS. The hospital anxiety and depression scale. Br Med J (Clin Res Ed) 1986;292(6516):344. doi: 10.1136/bmj.292.6516.344. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Spitzer RL, Kroenke K, et al. Validation and utility of a self-report version of PRIME-MD: the PHQ primary care study. Primary Care Evaluation of Mental Disorders. Patient Health Questionnaire. JAMA. 1999;282(18):1737–1744. doi: 10.1001/jama.282.18.1737. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sundin EC, Horowitz MJ. Impact of Event Scale: psychometric properties. Br J Psychiatry. 2002;180:205–209. doi: 10.1192/bjp.180.3.205. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sundin EC, Horowitz MJ. Horowitz's Impact of Event Scale evaluation of 20 years of use. Psychosom Med. 2003;65(5):870–876. doi: 10.1097/01.psy.0000084835.46074.f0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tanner BA. Validity of global physical and emotional SUDS. Appl Psychophysiol Biofeedback. 2012;37(1):31–34. doi: 10.1007/s10484-011-9174-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Thompson BT, Cox PN, et al. Challenges in end-of-life care in the ICU: statement of the 5th International Consensus Conference in Critical Care: Brussels, Belgium, April 2003: executive summary. Crit Care Med. 2004;32(8):1781–1784. doi: 10.1097/01.ccm.0000126895.66850.14. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Trau HC, Deighton R. Inhibition, disclosure and health: Don't simply slash the Gordian knot. Advances in Mind-Body Medicine. 1999;15:184–193. doi: 10.1054/ambm.1999.0086. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Truog RD, Campbell ML, et al. Recommendations for end-of-life care in the intensive care unit: a consensus statement by the American College [corrected] of Critical Care Medicine. Crit Care Med. 2008;36(3):953–963. doi: 10.1097/CCM.0B013E3181659096. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vig EK, Starks H, et al. Surviving surrogate decision-making: what helps and hampers the experience of making medical decisions for others. J Gen Intern Med. 2007;22(9):1274–1279. doi: 10.1007/s11606-007-0252-y. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vig EK, Taylor JS, et al. Beyond substituted judgment: How surrogates navigate end-of-life decision-making. J Am Geriatr Soc. 2006;54(11):1688–1693. doi: 10.1111/j.1532-5415.2006.00911.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wendler D, Rid A. Systematic review: the effect on surrogates of making treatment decisions for others. Ann Intern Med. 2011;154(5):336–346. doi: 10.7326/0003-4819-154-5-201103010-00008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- White M, Epston D. Narrative Means to Therapeutic Ends. New York: W.W. Norton and Co; 1990. [Google Scholar]