Abstract

Objective

This study examined the early childhood precursors and adolescent outcomes associated with gradeschool peer rejection and victimization among children oversampled for aggressive-disruptive behaviors. A central goal was to better understand the common and unique developmental correlates associated with these two types of peer adversity.

Method

754 participants (46% African American, 50% European American, 4% other; 58% male; average age 5.65 at kindergarten entry) were followed into seventh grade. Six waves of data were included in structural models focused on three developmental periods. Parents and teachers rated aggressive behavior, emotion dysregulation, and internalizing problems in kindergarten and grade 1 (waves 1–2); peer sociometric nominations tracked “least liked” and victimization in grades 2, 3, and 4 (waves 3–5); and youth reported on social problems, depressed mood, school adjustment difficulties, and delinquent activities in early adolescence (grade 7, wave 6).

Results

Structural models revealed that early aggression and emotion dysregulation (but not internalizing behavior) made unique contributions to gradeschool peer rejection; only emotion dysregulation made unique contributions to gradeschool victimization. Early internalizing problems and gradeschool victimization uniquely predicted adolescent social problems and depressed mood. Early aggression and gradeschool peer rejection uniquely predicted adolescent school adjustment difficulties and delinquent activities.

Conclusions

Aggression and emotion dysregulation at school entry increased risk for peer rejection and victimization, and these two types of peer adversity had distinct, as well as shared risk and adjustment correlates. Results suggest that the emotional functioning and peer experiences of aggressive-disruptive children deserve further attention in developmental and clinical research.

Keywords: Aggression, emotion dysregulation, peer rejection, victimization, adolescent maladjustment

Children with behavior problems at school entry are at risk for peer rejection and peer victimization, and these forms of peer adversity, in turn, are linked with significant maladajustment in adolescence, including school difficulties, social problems, delinquent activity, and compromised mental health (Hanish & Guerra, 2004). However, long-term longitudinal studies have not yet examined the differential precursors of these two types of peer adversity, or explored their differential associations with adolescent maladjustment.

Developmental research suggests that children who enter school exhibiting aggressive-disruptive behavior are at risk for peer rejection, and in turn, rejection appears to amplify risk for chronic aggression and emerging delinquent activities (Coie & Dodge, 1998). In elementary school, peer victimization is also linked with early aggression in some studies (Buhs, Ladd, & Herald, 2006; Crick, Murray-Close, Marks, & Hohajeri-Nelson, 2009) and with emotional dysregulation (Schwartz, Proctor, & Chien, 2001) and internalizing problems in others (Hawker & Boulton, 2000). Peer victimization does not appear to increase future risk for delinquent activities in the same way as peer rejection (Pouwels & Cillessen, 2013), but instead, victimization appears linked with long-term elevations in social avoidance and emotional distress (Boivin, Hymel, & Bukowski, 1995; Buhs et al., 2006; Nishina, Juvonen, & Witkow, 2005). Although peer rejection and victimization represent inter-dependent forms of peer adversity (Hanish & Guerra, 2004), their developmental precursors and adolescent outcomes may be somewhat distinct. A major limitation of the research base on this issue, however, is the lack of longitudinal studies that directly compare the developmental pathways associated with peer rejection and peer victimization while accounting for their overlap. A direct comparison is needed to better understand how these two forms of peer adversity may differentially and uniquely relate to adolescent adjustment, particularly among children who enter school with elevated aggression and are at high-risk for peer problems (Coie & Dodge, 1998). This study sheds light on this issue with participants oversampled for aggressive-disruptive behavior at school entry, and followed prospectively into early adolescence (grade 7). Longitudinal models tested the degree to which behavior problems and emotional functioning at school entry differentially predicted peer rejection and peer victimization in elementary school. In addition, the models explored the degree to which rejection and victimization made unique contributions to the prediction of four types of adolescent adjustment difficulties (social problems, depressed mood, school adjustment difficulties, and delinquent activities).

Peer Adversity: Rejection and Victimization

Rejection and victimization often co-occur, and rejected and victimized children alike experience few reciprocated friendships and a position of relative isolation in classroom social networks (Boivin et al., 1995). Several studies suggest that peer rejection places children at heightened risk for victimization by peers and conversely, victimization increases the likelihood of future rejection (Hanish & Guerra, 2000; Ladd & Troop-Gordon, 2003). Despite these common features, however, rejection and victimization represent distinct social processes from a conceptual and empirical standpoint (Juvonen & Gross, 2005). Peer rejection reflects peer attitudes and is measured by the degree to which members of the peer group dislike a child. In this study, rejection was measured as the proportion of classmates who nominated a peer as “least liked”. In contrast, peer victimization is a behavioral description identifying children who are frequently the target of harassment and hostile behavior by peers. For example, in this study, children were asked to identify classmates who get picked on and teased by other children. Victimized children are thus identified on the basis of their submissive position in the peer group, and their inability to avert or deflect negative treatment (Juvonen & Gross, 2005). Although rejection and victimization are correlated, the level of association is moderate, with reported correlations in the range of r = .30 (Buhs et al., 2006) to r = .60 (Knack et al., 2012).

Aggression, Emotion Dysregulation, Internalizing Behaviors and Peer Difficulties

In the early elementary school years, aggressive children are at high risk for peer problems (Ladd & Troop-Gordon, 2003). Aggressive behavior is off-putting to peers, but in addition, early aggression is often accompanied by other child characteristics that elicit censure from peers, such as low levels of prosocial skills, emotional volatility and dysregulation, and anxious-withdrawn social behaviors (Bierman, 2004; Hodges & Perry, 1999). Some of the poor social outcomes associated with aggression may be due to these concurrent difficulties. For example, Burke and Loeber (2010) have argued that it is the emotional negativity and volatility associated with early aggressive-oppositional behavior that undermines social adjustment and predicts later depression. Emotion dysregulation, which includes a tendency to over-react to stress or threat, along with difficulties modulating and managing emotion once aroused (Eisenberg, Fabes, Guthrie, & Reiser, 2000) creates vulnerability to both peer rejection and victimization (Schwartz, Proctor, & Chien, 2001). Internalizing problems (e.g., crying easily, feeling anxious and sad, withdrawal), which are elevated in samples of aggressive children, are also associated with peer difficulties, particularly victimization (Boivin et al., 1995; Graham & Juvonen, 1998; Troop-Gordon & Ladd, 2005).

Thus, aggression, emotion dysregulation, and internalizing problems may each elicit peer dislike and victimization and may, in turn, be aggravated by hostile peer treatment (Leadbeater & Hoglund, 2009). Despite a relatively large data base on these early childhood correlates of peer rejection and victimization, studies have not identified how these child characteristics put children at differential risk for rejection versus victimization and for adolescent maladjustment.

Aggression and Developmental Pathways Associated with Peer Rejection

A number of studies suggest that aggressive behavior is a primary predictor of peer rejection in early elementary school, and in turn, being rejected by peers increases the chronicity of aggression and predicts the emergence of rebellious behavior and delinquent activity in adolescence (Coie & Dodge, 1998). For example, controlling for kindergarten aggression, Miller-Johnson, Coie, Maumary-Gremaud, Bierman, & CPPRG (2002) found that first grade peer rejection enhanced the prediction of aggressive conduct problems in fourth grade. From a conceptual standpoint, peer rejection increases risk for chronic aggression and emerging antisocial behavior in at least two ways. First, it reduces opportunities for positive peer socialization experiences (Buhs et al., 2006; Powers, Bierman, & CPPRG, 2013). That is, as well-liked classmates play with each other, rejected children are often left to play alone or with younger children (Hektner, August, & Realmuto, 2000). This segregation from more socially-skillful peers results in lower levels of exposure to the types of social support and social exchanges that foster social competence and the development of prosocial play and negotiation skills. Second, peer rejection increases child exposure to other unskilled and aggressive classmates, supporting deviancy training, in which aggressive friends model and positively reinforce each other’s deviant behavior with laughter, interest, and approval (Dishion & Tipsord, 2011; Powers et al., 2012). Through both of these pathways, peer rejection increases the likelihood that aggressive children will experience peer socialization that supports the initiation of delinquent activities at the transition into adolescence (Deptula & Cohen, 2004).

It is important to note that children can be rejected by a majority of classmates, yet still maintain a position of dominance in the peer group that protects them from becoming the target of peer victimization (Perry, Hodges & Egan, 2001). Perhaps for this reason, empirical evidence linking early aggression with victimization is mixed.

Developmental Pathways Associated with Aggression and Peer Victimization

Although aggression is associated with victimization in a number of studies (Buhs et al., 2006; Crick et al., 2009; Ladd & Troop-Gordon, 2003), researchers have suggested that this association may be accounted for by deficits in emotion regulation skills that often accompany aggression and decrease a child’s capacity to tolerate the everyday frustrations and normative negotiations involved in peer interaction (Perry et al., 2001; Schwartz et al., 2001). Children who are easily irritated or annoyed, who over-react to provocations, and find it difficult to calm down and respond strategically to peer provocation may be particularly vulnerable to rejection and victimization by peers (Perry et al, 2001; Schwartz et al., 2001). Children who cry easily, feel distressed, and withdraw from peer interactions at school may also be vulnerable to victimization (Leadbeater & Hoglund, 2009). In support of this hypothesis, prior research has linked behavioral dysregulation (impulsivity) and emotional reactivity with peer victimization (Boivin et al., 1995; Hanish & Guerra, 2004). Existing evidence also links internalizing behavior and emotional distress with peer victimization, both as a predictor and consequence (Hodges & Perry, 1999; Leadbeater & Hoglund, 2009; Nishina et al., 2005). In a meta-analysis of longitudinal studies, internalizing problems emerged consistently as antecedents and consequences of peer victimization (Reijntjes, Kamphuis, Prinzie, & Telch, 2010).

The developmental sequelae of victimization also appear distinct from those associated with rejection. In early childhood, peer victimization appears to incite aggression, presumably as children retaliate in order to prevent future mistreatment (Ostrov, 2010). However, over time, victimization appears to increase social distress, becoming associated with depressed mood (Boivin et al., 1995), social withdrawal (Hanish & Guerra, 2004), internalizing problems (Hodges & Perry, 1999) and school avoidance (Buhs et al., 2006). Although aggression and victimization are significant correlated at school entry, they become increasingly less correlated over the course of the elementary school years (Pouwels & Cillessen, 2013). In fact, in one study of children in high-risk urban contexts, victimization at school entry predicted reduced aggression in the later elementary years for boys (Pouwels & Cillessen, 2013). In one of the few studies to compare the correlates of peer victimization and rejection, Lopez and Dubois (2010) found that, in middle school, victimization and rejection each made distinct contributions to depressive symptoms, but only rejection predicted aggressive and delinquent activities. Ladd and Troop-Gordon (2003) suggested that overt maltreatment by peers may generate distrust and fear of one’s classmates, intensifying feelings of loneliness and social alienation.

In summary, across studies, peer rejection emerges as a consistent predictor of adolescent rebelliousness and antisocial behavior, whereas victimization is more often associated with social isolation and emotional distress. However, none of these studies directly compared peer rejection and victimization longitudinally, in order to determine whether these two forms of peer adversity have distinct early childhood precursors and adolescent sequelae.

The Present Study

This study sought to advance understanding of peer rejection and victimization, focusing on a sample with many at risk for peer adversity due to elevated aggression at school entry. One central aim was to explore differential precursors to gradeschool rejection and victimization. It was hypothesized that aggressive behaviors and emotion dysregulation at school entry would emerge as risk factors for rejection and victimization later in elementary school, and that internalizing problems would also increase risk for victimization. A second aim was to examine the differential developmental sequelae associated with rejection and victimization. We focused on adolescent adjustment in four domains most closely associated with peer difficulties in past research: social problems, depressive symptoms, school adjustment difficulties, and delinquent activities. It was hypothesized that early aggression and subsequent peer rejection would uniquely increase risk for school adjustment difficulties and delinquent activities. In contrast, it was hypothesized that early emotion dysregulation, internalizing problems, and subsequent victimization would increase risk for adolescent social problems and depressed mood.

Method

Participants

This study included participants from the high-risk control and normative samples of the Fast Track project, a multi-site, longitudinal study of children at risk for conduct problems. They were recruited from 27 schools within four sites (Durham, NC; Nashville, TN; Seattle, WA; and rural PA), selected based on elevated crime and poverty statistics. In the first stage of the screening process, teachers rated the aggressive-disruptive behavior of all kindergarten children using a 10-item version of the Authority Acceptance subscale of the Teacher Observation of Child Adaptation-Revised scale (TOCA-R). Parents of children who scored in the top 40% on this screen within cohort and site were contacted; 91% agreed to provide ratings of aggressive-disruptive child behaviors at home on 24 items from the Child Behavior Checklist (CBCL; Achenbach, 199l) and similar scales. Teacher and parent screening scores were standardized and averaged, and children were recruited into the high-risk sample based on the severity of this screen score, moving from the highest score down the list until desired sample sizes were reached within sites and cohorts (see Lochman & CPPRG, 1995 for details). In addition to the high-risk children, who comprised 60% of the present sample, a normative sample of children was selected to represent the population at each site.

The current study utilized data from the high-risk control and normative groups, including 754 participants (46% African American, 50% European American, 4% other ethnic/racial groups; 58% male). At kindergarten entry, children were on average 5.65 years old (SD = .43). The data used in this study was collected at six time points, annually from kindergarten through fourth grade, and in seventh grade. In the structural models, the six waves of data collection were used to represent three developmental periods as follows: school entry (waves 1 and 2, kindergarten and first grade, ages 5–7), middle childhood (waves 3–5, grades 2–4, ages 7–10), and early adolescence (wave 6, grade 7, age12–13). Of the 754 participants with data at the initial kindergarten assessment, 623 (83%) had sociometric data for at least one year (grades 2–4) and 612 (81%) reported on their adolescent outcomes in grade 7. Children with and without missing data in grade 7 did not differ significantly on any of the school entry or sociometric variables used in this study. Maximum likelihood methods were used in the structural modeling in order to reduce spurious effects of missing data on the findings.

Measures

To reduce inflated estimates due to shared method variance, constructs were assessed with different reporters at each time point – parent and teacher ratings of aggression, emotion dysregulation, and internalizing problems at school entry (kindergarten and grade 1), peer nominations for rejection and victimization during middle childhood (grades 2–4), and self-reports assessing delinquency, school difficulties, social problems, and depressed mood in early adolescence (grade 7). Detailed descriptions of all measures are available at the Fast Track study website, http://www.fasttrackproject.org/data-instruments.php.

Child aggression, internalizing, and emotion dysregulation at school entry

At the end of kindergarten and first grade, parents and teachers each provided ratings on the Child Behavior Checklist – Parent and Teacher Report Forms (Achenbach, 1991). On this measure, the respondent indicated the presence of child behavior problems on a 3-point scale (0 = Not True; 1 = Somewhat/Sometimes True; 2 = Very True or Often True). A prior study (Stormshak, Bierman, & CPPRG, 1998) validated a narrow-band dimension of aggression on this measure, distinct from oppositional or hyperactive behaviors using a confirmatory factor analysis. The 9 items on this aggression narrow-band problem scale were used in this study (e.g., gets in many fights, physically attacks people, teases, threatens, destroys things, cruel, swears, lies and cheats). Total raw scores (α = 0.91 for parents, α = .92 for teachers) were standardized and averaged within grade level, to create a parent-teacher composite rating of aggression at each grade level (kindergarten, parent-teacher r = .26; first grade, parent-teacher r = .21).

Teacher and parent ratings on the internalizing scale on this measure were also used in the study. This 25-item scale includes items reflecting social withdrawal (e.g., shy or timid, withdrawn), anxiety (e.g., worries, nervous), and depressed mood (e.g., complains of loneliness, cries a lot). Total raw scores (α = 0.91 for parents, α = .92 for teachers) were standardized and averaged within grade level, to create a parent-teacher composite rating of internalizing problems at each grade level (kindergarten, parent-teacher r = .13; first grade, parent-teacher r = .21).

Parents and teachers also completed the emotion regulation subscale of the Social Competence Scale (CPPRG, 1995), including 9 items (for teachers) and 7 items (for parents), each rated on a 5-point Likert scale. Items described the child’s ability to regulate emotions under conditions of heightened arousal (e.g., controls temper in a disagreement; calms down when excited or wound up; can accept things not going his or her way; copes well with failure; α = 0.81 for parents, α = .78 for teachers). All items were scored such that higher scores represented more dysregulation. They were standardized within reporter and grade level, and then averaged, to create grade-level parent-teacher composites (kindergarten, parent-teacher r = .35; first grade, parent-teacher r = .18).

Peer nominations of rejection and victimization

Sociometric nominations were collected each year for each cohort in the second, third, and fourth grade classrooms of the original study schools, with an average class-level participation rate of 74%. Children with parental informed consent were interviewed individually at school, providing unlimited nominations (within classroom, across gender) in response to the question “Who do you like the least?” which indexed rejection, and to the question “Who gets picked on and teased by other kids?” which indexed victimization. Nominations were summed and standardized within classroom. Children had data for all three years if they remained in their original school districts where sociometric nominations were collected; however, they were missing nominations in one or more of these years if they moved out of their original school districts. 623 of the 754 children in this study (83%) had sociometric data for at least one of these years; 564 (75%) had data in Grade 2, 480 (64%) had data in grade 3, and 474 (63%) had data in grade 4.

Early adolescent adjustment

During a home visit conducted during the summer after seventh grade, youth reported on their social problems, depressed mood, school adjustment difficulties, and delinquent activities. Youth reported on social problems using the social adjustment difficulties subscale of the School Adjustment scale developed for the Fast Track study (CPPRG, 2003), which included 5 items describing peer relations (e.g., “I had a hard time making friends”, “Other kids bothered me this year”, “I did not have many friends”, α = .75). Items were scored so that high scores represented higher levels of maladjustment, and were averaged to create a total score representing social problems. The distribution was skewed and was normalized with a square root transformation. Depressed mood was assessed with the Reynolds Adolescent Depression Scale (Reynolds, 1987) which included 30 items, each rated on a 4-point scale, from “almost never” to “almost all of the time.” Items included “I feel lonely”, “I feel sad”, “I feel that no one cares about me”. The total score (the mean of the 30 items) indicated the number of depression symptoms reported (α = .90). School adjustment difficulties were assessed with an 8-item scale developed for the Fast Track project (CPPRG, 2003). On a 5-point scale (e.g., “never true” to “always true”) youth described academic and behavioral school difficulties they experienced during the prior year (e.g., “the school year was difficult for me,” “I got into trouble this year,” and “teachers were on me because I broke rules”; α = .71). Finally, delinquent activities were assessed using the Self-Reported Delinquency scale (Elliot, Huizinga, & Ageton, 1985), which included property damage, theft, and assault. For each type of delinquent act, youth reported whether they ever committed it, how many times in the past year, if others were involved, and if they were under the influence of alcohol or drugs while committing it. The 25 yes/no items were averaged for a total score (α = .74). The distribution was skewed and was normalized with a log transformation.

Procedures

Parents were interviewed at home in the summer following the child’s kindergarten and first grade year by trained research staff members, who read through all questionnaires and recorded responses. During the first home interview, parents provided initial informed consent for study involvement and they re-consented each year thereafter. Research assistants delivered and explained measures to teachers in the spring of the kindergarten and first-grade years; teachers then completed them on their own and returned them to the Fast Track project. Youth interviews were conducted during home visits held during the summer following seventh grade, using computer-administered processes to increase privacy and confidentiality. Youth provided assent. Youth listened to questions via headphones as they appeared on a computer screen, and they responded directly by indicating their answers on the computer. Teachers, parents, and children received financial compensation for their participation. All study procedures complied with the ethical standards of the American Psychological Association. The Institutional Review Boards of the participating universities approved all study procedures.

Prior analyses of Fast Track demonstrated that the sample was fairly mobile, and rapidly expanded from the original 401classrooms they were nested in at the start of the study. In a prior study, third grade analyses revealed no dependency among students based on their initial classrooms (CPPRG, 2002) and, for this reason, we determined that it was not necessary or appropriate to account for nesting within original classrooms or schools in this study.

Results

Data analyses proceeded in two stages. First, correlations were computed to examine simple associations among child characteristics at school entry, peer rejection and victimization in gradeschool, and adjustment in early adolescence. Then, structural equation models evaluated the associations among the child characteristics at school entry (aggression, emotion dysregulation, internalizing), gradeschool peer adversity (rejection, victimization), and early adolescent outcomes (social problems, depressed mood, school difficulties, delinquent activity).

Descriptive Analyses

Means, standard deviations, and ranges for all study variables are shown in Table 1. Initial tests for sex differences revealed that boys had significantly higher scores than girls on aggression, emotion dysregulation, peer rejection, and adolescent school difficulties. Table 2 provides the correlations among all study variables. Aggression and emotion dysregulation were each moderately stable from kindergarten to first grade (rs = .59 and .58, respectively) and were significantly intercorrelated (r = .68 in kindergarten, r = .59 in first grade). Internalizing behaviors were somewhat less stable from kindergarten to first grade (r = .32), and were mildly to moderately correlated with emotion dysregulation (rs = .32, .27) and aggression (rs = .36, .42) in kindergarten and first grade. All of these child characteristics were significantly associated with peer rejection in kindergarten and first grade (rs ranged from .08 to .36, average r = .25); however, only emotion dysregulation and kindergarten internalizing behaviors were significantly associated with victimization (rs ranged from .08 to .13, average r = .10). Child characteristics and both forms of peer adversity significantly predicted the four measures of early adolescent adjustment, with three exceptions. Internalizing behaviors at school entry were not associated with later delinquent activities, and peer victimization in middle childhood was not associated with later delinquent activities or school difficulties. In general, these correlations validated early aggression, emotion dysregulation, internalizing behavior, as well as peer rejection and victimization as risk factors associated with adolescent maladjustment.

Table 1.

Descriptive Statistics for Study Variables

| Full Sample | Male | Female | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Variables | N | M (SD) | Range | M (SD) | M (SD) |

| School Entry (Grades K-1) | |||||

| Aggression – Ka | 752 | 0.00 (1.00) | −1.32 – 3.88 | 0.22 (1.01) | −0.30 (0.90) |

| Aggression – 1a | 729 | 0.00 (1.00) | −1.20 – 4.07 | 0.21 (1.02) | −0.29 (0.90) |

| Emotion dysregulation- Ka | 754 | 0.00 (1.00) | −3.52 – 2.30 | 0.18 (0.93) | −0.25 (1.05) |

| Emotion dysregulation- 1a | 722 | 0.00 (1.00) | −2.89 – 2.64 | 0.17 (0.97) | −0.24 (1.00) |

| Internalizing - Ka | 752 | 0.00 (1.00) | −1.59 – 6.19 | 0.03 (1.02) | −0.04 (0.98) |

| Internalizing - 1a | 714 | 0.00 (1.00) | −1.32 – 4.50 | 0.03 (0.99) | −0.05 (1.01) |

| Gradeschool (Grades 2–4) | |||||

| Peer rejectiona | 623 | 0.01 (0.89) | −1.63 – 3.48 | 0.20 (0.94) | −0.23 (0.75) |

| Peer victimizationa | 623 | 0.00 (0.83) | − 1.41 – 4.08 | −0.04 (0.82) | 0.06 (0.84) |

| Adolescence (Grade 7) | |||||

| Social Problems | 611 | 0.62 (0.61) | 0.00 – 3.20 | 0.63 (0.61) | 0.59 (0.60) |

| Depressed Mood | 612 | 1.72 (0.43) | 1.00 – 3.30 | 1.69 (0.39) | 1.75 (0.49) |

| School Difficulties | 611 | 2.45 (0.65) | 1.00 – 4.36 | 2.60 (0.62) | 2.25 (0.64) |

| Delinquent Activity | 607 | 0.03 (0.07) | 0.00 – 0.60 | 0.04 (0.08) | 0.02 (0.05) |

Note. K = kindergarten, 1 = first grade. Sex differences were significant for aggression in K, F (1, 750) = 54.05, d = .54 and Grade 1, F (1, 727) = 46.44, d = .51; emotion dysregulation in K, F (1, 752) = 34.89, d = .44 and Grade 1, F (1, 720) = 31.66, d = .42; peer rejection, F (1, 621) = 38.70, d = .49; school difficulties, F (1, 609) = 46.75 d = .56; and delinquency, F (1, 606) = 12.93, d = .29, all p < .01.

indicates a standardized score.

Table 2.

Correlations among Study Variables

| Variable | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | 6 | 7 | 8 | 9 | 10 | 11 | 12 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| School Entry (Grade K-1) | |||||||||||

| 1 Externalizing- K | .59** | .54** | .39** | .36** | .19** | .36** | .04 | .09* | .09* | .32** | .20** |

| 2 Externalizing – 1 | -- | .38** | .45** | .21** | 42** | .30** | −.01 | .10** | .13** | .28** | .12** |

| 3 Emotion dysregulation - K | -- | .58** | .32** | .18** | .31** | .13** | .15** | .17** | .29** | .12** | |

| 4 Emotion dysregulation – 1 | -- | .17** | .27** | .25** | .08* | .17** | .10* | .24** | .10* | ||

| 5 Internalizing - K | -- | .32** | .19** | .10* | .18** | .17** | .15** | .03 | |||

| 6 Internalizing - 1 | -- | .08* | −.02 | .13** | .13** | .14** | .02 | ||||

| Gradeschool (Grade 2–4) | |||||||||||

| 7 Peer rejection | -- | .39** | .21** | .09* | .24** | .17** | |||||

| 8 Peer victimization | -- | .21** | .16** | .05 | .01 | ||||||

| Adolescence (Grade 7) | |||||||||||

| 9 Social Problems | -- | .44** | .33** | .18** | |||||||

| 10 Depressed Mood | -- | .36** | .22** | ||||||||

| 11 School Difficulties | -- | .32** | |||||||||

| 12 Delinquency | -- |

Note. K = Kindergarten. 1 = First grade.

p < .05.

p < .01.

In this table, peer rejection and victimization scores represent the average across grades 2–4.

Examining Multifaceted Longitudinal Models

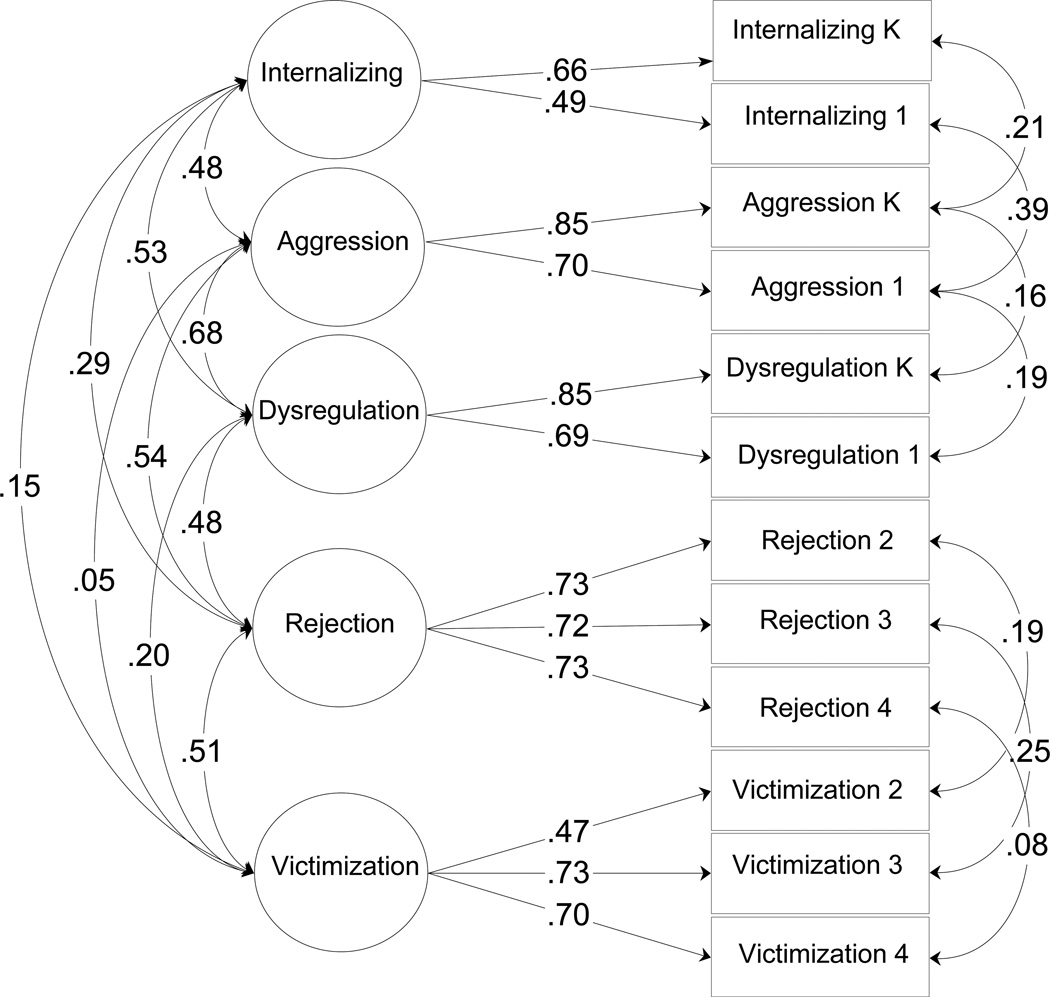

Evaluating the measurement model

Prior to computing the structural equation models predicting each of the adolescent outcomes, a measurement model was estimated (see Figure 1). Child emotion dysregulation and child externalizing behaviors were indexed by the composited parent-teacher ratings at kindergarten and at first grade. Peer rejection and victimization were indexed by peer nominations collected in grades 2, 3, and 4. Errors were allowed to correlate across the measures collected within the same year to adjust for shared temporal associations. Fit indices for the measurement model suggested that the hypothesized relations among observed measures and latent constructs did a good job of representing patterns in the data, χ2 (df = 35) = 64.35, p < .004, relative χ2 = 1.7, CFI = .99, TLI = .97, RMSEA = .031, SRMR=.0002. Although a non-significant χ2 is preferred, this is rare in large samples, and the relative χ2 and other fit indices indicate a good fit.

Figure 1.

Measurement Model: Early Childhood Characteristics and Gradeschool Peer Rejection and Victimization

Note: K = kindergarten, 1 = Grade 1, 2 = Grade 2, 3 = Grade 3, 4 = Grade 4

A test of measurement invariance was conducted for sex by comparing the fit of a measurement model in which all relations were allowed to vary for boys and girls with the fit of a measurement model in which all relations were constrained to be equal. The difference in the CFI was approximately 0 for all outcomes, indicating invariance across sex (Cheung & Rensvold, 2002). A second test of invariance was conducted to compare the fit of the measurement model for European American and African American children. Again, the difference in the CFI was less than −.01 for all outcomes, indicating invariance. A third test of invariance was conducted to compare the fit of the measurement model for children in the high-risk aggressive sample and those in the normative sample. The difference in the CFI was less than −.01 for social problems, and just slightly higher for delinquency, depressed mood, and school difficulties. Overall, these comparisons indicated invariance in the measurement model across sub-samples. Hence, subsequent analyses were run for the entire sample.

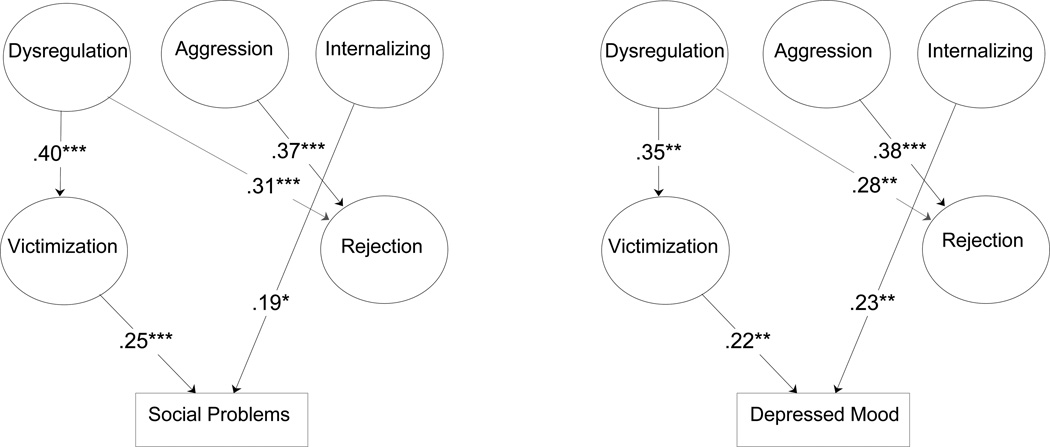

Model predicting social problems

The first structural model evaluated associations between child characteristics at school entry, peer adversity in elementary school, and social problems in early adolescence. This model tested direct links between each of the predictive constructs (e.g., early aggression, emotion dysregulation, internalizing behavior, peer victimization, and peer rejection) and the adolescent outcome, and also included links between the early child characteristics (aggression, emotion dysregulation and internalizing behavior) and the two forms of peer adversity. A characteristic of this model is that these predictive associations control for the concurrent associations of other variables in the model. The overall fit of the model was satisfactory, χ2 (df = 45) = 141, p < .001, relative χ2 = 3.12, CFI = .95, TLI = .91, RMSEA = .05, standardized RMR = .0002. As shown in Figure 2, child aggression and emotion dysregulation each made a significant unique contribution to peer rejection in middle childhood, and child emotion dysregulation significantly predicted victimization. In turn, peer victimization in middle childhood uniquely predicted social problems in adolescence. Although child internalizing behavior at school entry was not significantly associated with either form of peer adversity, it made a unique direct contribution to adolescent social problems.

Figure 2.

Structural Models Predicting Social Problems and Depressed Mood

Note: Emotion dysregulation, aggression, and internalizing were measured in kindergarten and grade 1, victimization and rejection were measured in early elementary school (grades 2–4), and social problems and depressed mood were measured in grade 7. * p < .05; ** p < .01; *** p < .001.

Model predicting depressed mood

The second structural model evaluated associations between child characteristics at school entry, peer adversity in elementary school, and depressed mood in early adolescence. The overall fit of the model was satisfactory, χ2 (df = 45) = 139, p < .004, relative χ2 = 3.09, CFI = .96, TLI = .91, RMSEA = .053, standardized RMR = .0002. As shown in Figure 2, child aggression and emotion dysregulation at school entry each made a significant unique contribution to peer rejection in middle childhood, and child emotion dysregulation significantly predicted victimization. In turn, peer victimization in middle childhood predicted depressed mood in adolescence, but peer rejection did not. Although child internalizing behavior at school entry was not significantly associated with either form of peer adversity, it was directly associated with depressive symptoms in adolescence.

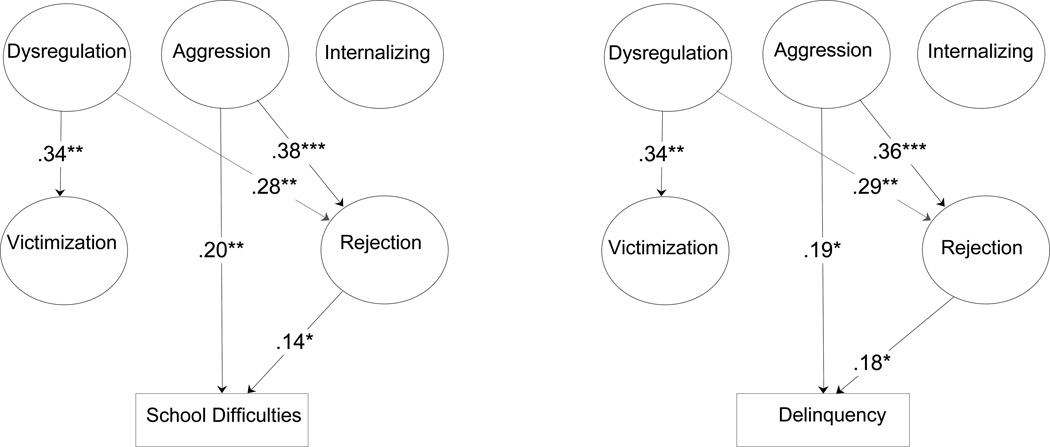

Model predicting school adjustment difficulties

Next, a structural model was computed to evaluate associations between child characteristics at school entry, peer adversity in elementary school, and school adjustment difficulties in early adolescence. The overall fit of the model was satisfactory, χ2 (df = 45) = 136, p < .000, relative χ2 = 3.02, CFI = .96, TLI = .91, RMSEA = .052, standardized RMR = .0002. As shown in Figure 3, child aggression and emotion dysregulation at school entry each made a significant unique contribution to peer rejection, and child emotion dysregulation significantly predicted victimization. In turn, gradeschool peer rejection predicted school adjustment difficulties in adolescence, but peer victimization did not. In addition, child aggression at school entry made an additional direct and unique contribution to adolescent school adjustment difficulties. Child internalizing behavior was not significantly associated with peer adversity or adolescent school adjustment difficulties.

Figure 3.

Structural Models Predicting School Difficulties and Delinquent Activities

Note: Emotion dysregulation, aggression, and internalizing were measured in kindergarten and grade 1, victimization and rejection were measured in early elementary school (grades 2–4), and social problems and depressed mood were measured in grade 7. * p < .05; ** p < .01; *** p < .001.

Model predicting delinquent activities

Last, a structural model evaluated associations between child characteristics at school entry, peer adversity in elementary school, and delinquent activities in early adolescence. The overall fit of the model was satisfactory, χ2 (df = 45) = 140, p < .000, relative χ2 = 3.12, CFI = .95, TLI = .91, RMSEA = .053, standardized RMR = .0002. As shown in Figure 3, child aggression and emotion dysregulation at school entry made unique contributions to peer rejection, and child emotion dysregulation significantly predicted victimization. In turn, gradeschool peer rejection predicted delinquent activities in adolescence, but peer victimization did not. In addition, child aggression at school entry made an additional direct contribution to adolescent delinquent activities. Child internalizing behavior was not significantly associated with peer adversity or with adolescent delinquent activities.

Discussion

Prior research has established that children who enter school with elevated aggressive-disruptive behavior problems are often disliked by a majority of their classmates (peer rejected) and often become targets of peer-directed hostility (peer victimized) (Crick et al., 2009). Both forms of peer adversity are linked with adolescent maladjustment, but they are typically studied separately, leaving unanswered questions about the degree to which their developmental determinants and adolescent sequelae are shared or distinct. Using longitudinal data and a high-risk sample, this study examined the associations between risk factors assessed at school entry (aggression, emotion dysregulation, internalizing problems), gradeschool peer rejection and victimization, and four types of maladjustment in adolescence – social problems, depressed mood, school adjustment difficulties, and antisocial activities. Shared and distinct correlates were evident. In the structural equation models that accounted for all variables in the model, unique associations linked early aggression with peer rejection and early emotion dysregulation with peer rejection and victimization. In turn, rejection and victimization, along with early internalizing problems, were uniquely associated with social problems in adolescence. Victimization and early internalizing problems also predicted depressed mood in adolescence. In contrast, early aggression and peer rejection uniquely predicted adolescent school adjustment difficulties and emerging delinquent activities.

Aggression, Emotion Dysregulation, Peer Rejection, and Adolescent Rebellion

The present findings are consistent with prior research that has documented developmental links between early aggression, peer rejection, and adolescent rule-breaking and delinquent activities. This developmental pathway is most often conceptualized within a social learning theory framework, which posits that aggressive behavior evokes responses from peers that both constrain social learning opportunities and potentiate others (Coie & Dodge, 1998; Dishion & Tipsord, 2011). Specifically, as aggressive behaviors evoke censure and avoidance from prosocial peers, they limit opportunities for constructive social interactions in which positive play and peaceful conflict management strategies are modeled, reinforced, and thereby developed (Hektner et al., 2000). In addition, aggressive behaviors increase the likelihood of deviancy training, in which aggressive friends model deviant behavior and reinforce it with laughter and attention. In these ways, peer rejection may intensify the social segregation of aggressive children, amplifying their exposure to peer deviancy training and future opportunities for rebellious behavior at school and antisocial activity (see also Deptula & Cohen, 2004).

Interestingly, early emotion dysregulation also contributed unique variance to peer rejection, beyond that predicted by aggressive behaviors and distinct from the association with peer victimization. This finding supports the value of further research focused on the emotional functioning of young aggressive children, which is emerging as an important area of developmental study, particularly as advancing technologies are illuminating the impact of early adversity on the development of regulatory functioning in early childhood. Social learning theory emphasizes the instrumental and goal-oriented functions of aggressive behavior, which may be motivated by anticipated rewards and shaped by reinforcement experiences. However, aggression can also be defensive in nature, activated by the more primitive neural circuits that process threat and energize action fueled by anger or fear (Bierman & Sasser, in press; Vitaro & Brendgen, 2005). The development of the stress response system, including the vigilance and reactivity to perceived threat that triggers reactive aggression may be affected significantly by temperament and by early socialization experiences (Cicchetti, 2002). Heightened emotional reactivity and difficulties modulating emotional arousal may impede peer collaboration and contribute to peer dislike in ways that are distinct from aggression (Eisenberg et al., 2000; Murray-Close, 2013), as well as creating vulnerability to peer victimization.

Emotion Dysregulation, Victimization, Adolescent Social Problems and Depressed Mood

In this study, child emotion dysregulation at school entry also figured significantly in a developmental pathway through peer victimization to adolescent social problems and depressed mood. Prior researchers have suggested that emotion dysregulation can increase a child’s vulnerability to peer harassment both because poorly modulated emotional reactions (e.g. tantrums, whining) aggravate peers, and also because dysregulated emotions compromise the child’s ability to respond strategically to peer provocation (Perry et al., 2001; Schwartz et al., 2001). Perry and colleagues (2001) used the term “ineffectual aggressors” to describe aggressive children who are impulsive, volatile, over-reactive, and argumentative; they react to peer provocation with hostility and intensive distress, but remain ineffective socially, unable to use their aggressive behavior to deflect hostile overtures from others. In contrast, other aggressive children, despite being disliked by classmates, are able to use aggression more strategically and effectively, thereby maintaining positions of social dominance that may protect them from future victimization (Bierman, 2004; Knack et al., 2012; Rodkin, Farmer, & Van Acker, 2000).

The preschool and early gradeschool years may represent an important developmental juncture in the diverging pathways associated with the future victimization and/or rejection of aggressive children. Vitaro and Brengden (2005) have proposed a sequential process model to describe continuities (and discontinuities) in the developmental course of aggression. They suggest that emotionally dysregulated and reactive aggression characterizes the majority of aggressive acts instigated by young children. With the rapid development of self-regulatory capacities during early childhood (ages 3–7), some children learn to inhibit and redirect their aggressive impulses. For others, proactive aggression emerges, as they experience social contingencies that “teach” them how to use aggression strategically to attain goals or avoid imposed limits. Children who continue to struggle with emotion dysregulation after the transition into elementary school (and after the normative improvement in self-regulatory skills) may be at highest risk for chronic victimization (Schwartz et al., 2001). Although not tested in this study, prior research suggests that associated deficits in regulatory functioning, particularly poor attention control, often characterize emotionally dysregulated kindergarteners and first-graders (Farmer, Bierman, & CPPRG, 2002; Schwartz et al., 2001). The findings from this study suggest that these children may be particularly vulnerable to victimization.

Interestingly, in this study, although internalizing problems at school entry were significantly correlated with peer rejection and victimization, they did not increase risk for peer rejection or victimization in the models that accounted for co-occurring aggression and emotion dysregulation. However, early internalizing problems explained unique variance in later adolescent social problems and depressed mood, suggesting that they may index vulnerability to emotional distress that operates independently from peer experiences of rejection or victimization, possibly linked with temperament or early family experience (Eisenberg et al., 2000). These findings are also consistent with a pattern evident across studies of children at different ages, in which internalizing behavior and social withdrawal are less likely to predict victimization during the early elementary years (Buhs et al., 2006; Hanish & Guerra, 2000; Schwartz et al., 1999), but more often emerge as significant predictors of victimization in studies of older elementary school students (Boivin et al., 1995; Hanish & Guerra, 2000).

In this study, the social and emotional sequelae associated with chronic exposure to peer victimization emerged as distinct from the social-emotional impact of exposure to peer dislike. Grade school victimization and rejection were both associated with self-reported social problems in early adolescence, including an inability to make friends, get along with peers, or feel comfortable socially at school. Only victimization and early internalizing problems were associated with depressed mood, including loneliness and feelings of worthlessness. These findings are also consistent with prior research, which has documented negative self and peer perceptions associated with victimization (Nishina et al., 2005; Salmivalli & Isaacs, 2005). Ladd and Troop-Gordon (2003) have suggested that being harmed by peers represents a form of trauma that is distinct from being disliked or excluded, and may amplify feelings of interpersonal distrust, fear, and alienation, as well as feelings of helplessness and inadequacy that create particular vulnerability to social isolation and depression in adolescence.

Study Limitations

This study had several limitations. First, the data did not allow for a separate analysis of different types of early aggressive behavior or victimization. Previous researchers have documented important differences in the experiences of children who exhibit or receive primarily physical aggression and victimization compared with those who exhibit or receive primarily relational victimization (Crick et al., 2009; Ostrov, 2010; Taylor et al., 2013). The measures used in this study were weighted toward physical victimization, which may have under-represented the victimization experiences of some participants, particularly girls who may more often experience relational victimization (Crick et al., 2009; Ostrov, 2010). Second, this study relied on peer nominations to assess victimization. This measurement strategy had the advantage of avoiding shared method variance in longitudinal analyses. However, it may have underestimated child exposure to victimization. These results likely reflect a conservative assessment of the association between peer victimization and later social problems and depressed mood (Crick et al., 2009; Scholte, Burk, & Overbeek, 2013). Third, and relatedly, this study did not include measures of social cognitions and self-perceptions, including attributions about others and self-evaluations, that may serve as important mediators of the impact of peer adversity on later adolescent outcomes (Salmivalli & Isaacs, 2005). This study also relied on behavioral ratings to assess emotion dysregulation, which do not provide precise assessments of emotional reactivity or regulatory control, thereby limiting information about the specific mechanisms that may underlie the observed effects. Fifth, the participants in this study were recruited from high-risk schools with an intentional over-sampling of aggressive-disruptive students. This sample allowed for a careful developmental study of the peer adversity experienced by high-risk, aggressive children, but the generalizability of these findings to more normative samples is unknown. Finally, these longitudinal data do not illuminate the causal mechanisms that may account for the developmental associations. The theory-based speculations regarding causal influences discussed in this paper require validation in future research.

Clinical Implications and Future Directions

The results of this study suggest that the emotional vulnerabilities and peer experiences of aggressive-disruptive children deserve further attention in developmental and clinical research. Diverging developmental pathways emerged for rejection and victimization. The findings suggest that aggressive and rejected children are at elevated risk for school adjustment difficulties and delinquent activity. Conversely, emotionally-dysregulated, victimized children and children with early internalizing problems are at risk for social problems and compromised mental health, including significant depressed mood, feelings of social alienation, and emotional distress. Understanding these diverging pathways may enhance the design of prevention and early intervention programs. In general, efforts to promote the emotion regulation skills, as well as the social interaction and conflict management skills of children who enter school with elevated aggression and/or internalizing problems appear warranted in order to reduce exposure to peer victimization or rejection (Bierman, 2004). In addition, a focus on the peer group and social dynamics within the classroom may be critical for effective interventions, in order to create niches of opportunity that provide vulnerable children with positive peer socialization support and reduce the prevalence and impact of victimization and rejection.

Acknowledgments

We thank the Fast Track project staff and participants and acknowledge the critical contributions and support of the Conduct Problems Prevention Research Group members John Coie, Kenneth Dodge, Mark Greenberg, John Lochman, Robert McMahon, and Ellen Pinderhughes. This work was supported by National Institute of Mental Health (NIMH) grants R18 MH48043, R18 MH50951, R18 MH50952, and R18 MH50953. The Center for Substance Abuse Prevention and the National Institute on Drug Abuse also provided support for Fast Track through a memorandum of agreement with the NIMH. This work was also supported in part by Department of Education grant S184U30002, NIMH grants K05MH00797 and K05MH01027, and NIDA grants DA16903, DA017589, and DA015226, and grant R305B090007 from the Institute of Education Sciences. The views expressed in this article are ours and do not necessarily represent the granting agencies.

Contributor Information

Karen L. Bierman, Email: kb2@psu.edu.

Carla B. Kalvin, Email: carla.kalvin@gmail.com.

Brenda S. Heinrichs, Email: ibc@psu.edu.

References

- Achenbach TM. Manual for the Child Behavior Checklist: 4–18 and 1991 profile. Burlington, VT: University of Vermont Department of Psychiatry; 1991. [Google Scholar]

- Bierman KL. Peer rejection: Developmental processes and intervention strategies. New York: Guilford; 2004. [Google Scholar]

- Bierman KL, Sasser TR. Conduct Disorder. In: Lewis M, Rudolph K, editors. Handbook of developmental psychopathology. 3rd edition. New York: Springer; (in press). [Google Scholar]

- Boivin M, Hymel S, Bukowski WM. The roles of social withdrawal, peer rejection, and victimization in predicting loneliness and depressed mood in childhood. Development and Psychopathology. 1995;7:765–785. [Google Scholar]

- Buhs ES, Ladd GW, Herald SL. Peer exclusion and victimization: Processes that mediate the relation between peer group rejection, classroom engagement and achieve-ment? Journal of Educational Psychology. 2006;98:1–13. [Google Scholar]

- Burke J, Loeber R. Oppositional defiant disorder and the explanation of the comorbidity between behavioral disorders and depression. Clinical Psychology: Science and Practice. 2010;17:319–326. [Google Scholar]

- Cheung GW, Rensvold RB. Evaluating goodness-of-fit indexes for testing measurement invariance. Structural Equation Modeling. 2002;9:233–255. [Google Scholar]

- Cicchetti D. The impact of social experience on neurobiological systems: Illustration from a constructivist view of child maltreatment. Cognitive Development. 2002;17:1407–1428. [Google Scholar]

- Coie JD, Dodge KA. Aggression and antisocial behavior. In: Eisenberg N, editor. Handbook of child psychology: Social, emotional, and personality development. 5th ed. Vol. 3. New York: Wiley; 1998. pp. 779–862. [Google Scholar]

- CPPRG. School Adjustment – Child: Fast Track Project Technical Report. 2003 Retrieved March 23, 2013 from http://www.fasttrackproject.org/techrept/s/sac/sac8tech.pdf.

- CPPRG. Evaluation of the first 3 years of the Fast Track prevention trial with children at high risk for adolescent conduct problems. Journal of Abnormal Child Psychology. 2002;30:19–35. doi: 10.1023/a:1014274914287. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- CPPRG. Social Competence Scale – Teacher and Parent Reports. 1995 Retrieved March 23, 2013 from http://www.fasttrackproject.org/techrept/s/sct/sct1tech.pdf.

- Crick NR, Murray-Close D, Marks PEL, Mohajeri-Nelson N. Aggression and peer relationships in middle childhood and early adolescence. In: Rubin KH, Bukowski W, Laursen B, editors. The handbook of peer interactions, relationships, and groups. New York: Guilford; 2009. pp. 287–302. [Google Scholar]

- Deptula DP, Cohen R. Aggressive, rejected, and delinquent children and adolescents: A comparison of their friendships. Aggression and Violent Behavior. 2004;9:75–104. [Google Scholar]

- Dishion TJ, Tipsord JM. Peer contagion in child and adolescent social and emotional development. Annual Review of Psychology. 2011;62:189–214. doi: 10.1146/annurev.psych.093008.100412. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Eisenberg N, Fabes RA, Guthrie IK, Reiser M. Dispositional emotionality and regulation: Their role in predicting quality of social functioning. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology. 2000;78:136–157. doi: 10.1037//0022-3514.78.1.136. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Elliot DS, Huizinga D, Ageton S. Explaining delinquency and drug use. Beverly Hills, CA: Sage; 1985. [Google Scholar]

- Farmer AD, Bierman KL the CPPRG. Predictors and consequences of aggressive-withdrawn problem profiles in early grade school. Journal of Clinical Child Psychology. 2002;31:299–311. doi: 10.1207/S15374424JCCP3103_02. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hanish LD, Guerra NG. Aggressive victims, passive victims, and bullies: Developmental continuity or developmental change? Merrill-Palmer Quarterly. 2004;50:17–38. [Google Scholar]

- Hawker DSJ, Boulton MJ. Twenty years’ research on peer victimization and psychosocial maladjustment: A meta-analytic review of cross-sectional studies. Journal of Child Psychology and Psychiatry. 2000;41:441–455. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hektner JM, August GJ, Realmuto GM. Patterns and temporal changes in peer Affiliation among aggressive and nonaggressive children participating in a summer school program. Journal of Clinical Child Psychology. 2000;29:603–614. doi: 10.1207/S15374424JCCP2904_12. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hodges EVE, Perry DG. Personal and interpersonal antecedents and Consequences of victimization by peers. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology. 1999;76:677–685. doi: 10.1037//0022-3514.76.4.677. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Juvonen J, Gross EF. The rejected and the bullied: Lessons about social misfits from developmental psychology. In: Williams KD, Forgas JP, von Hippel W, editors. The social outcast: Ostracism, social exclusion, rejection, and bullying. New York: Psychology Press; 2005. pp. 155–170. [Google Scholar]

- Knack JM, Tsar V, Vaillancourt T, Hymel S, McDougall P. What protects rejected adolescents from also being bullied by their peers? The moderating role of peer-valued characteristics. Journal of Research on Adolescence. 2012;22:467–479. [Google Scholar]

- Ladd GW, Troop-Gordon W. The role of chronic peer difficulties in the development of children’s psychological adjustment problems. Child Development. 2003;74:1344–1367. doi: 10.1111/1467-8624.00611. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Leadbeater BJ, Hoglund W. The effects of peer victimization and physical aggression on changes in internalizing from first to third grade. Child Development. 2009;80:843–859. doi: 10.1111/j.1467-8624.2009.01301.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lochman JE CPPRG. Screening of child behavior problems for prevention programs at school entry. Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology. 1995;63:549–559. doi: 10.1037//0022-006x.63.4.549. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lopez C, DuBois DL. Peer victimization and rejection: Investigation of an integrative model of effects on emotional, behavioral, and academic adjustment in early adolescence. Journal of Clinical Child and Adolescent Psychology. 2005;34:25–36. doi: 10.1207/s15374424jccp3401_3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Miller-Johnson S, Coie JD, Maumary-Gremaud A, Bierman K CPPRG. Peer rejection and aggression and early starter models of conduct disorder. Journal of Abnormal Child Psychology. 2002;30:217–230. doi: 10.1023/a:1015198612049. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Murray-Close D. Psychophysiology of adolescent peer relations I: Theory and research findings. Journal of Research on Adolescence. 2013;23:236–259. [Google Scholar]

- Nishina A, Juvonen J, Witkow M. Sticks and stones may break my bones, but names will make me sick: The consequences of peer harassment. Journal of Clinical Child and Adolescent Psychology. 2005;34:37–48. doi: 10.1207/s15374424jccp3401_4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ostrov JM. Prospective associations between peer victimization and aggression. Child Development. 2010;81:1670–1677. doi: 10.1111/j.1467-8624.2010.01501.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Perry D, Hodges E, Egan S. Determinants of chronic victimization by peers: A review and new model of family influence. In: Juvonen J, Graham S, editors. Peer harassment in school: The plight of the vulnerable and victimized. New York: Guilford Press; 2001. pp. 73–104. [Google Scholar]

- Powers CJ, Bierman KL CPPRG. The multifaceted impact of peer relations on aggressive-disruptive behavior in early elementary school. Developmental Psychology. 2013;49:1174–1186. doi: 10.1037/a0028400. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pouwels JL, Cillessen AHN. Correlates and outcomes associated with aggression and victimization among elementary school children in a low-income urban context. Journal of Youth and Adolescence. 2013;42:190–205. doi: 10.1007/s10964-012-9875-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Reynolds WM. Reynolds Adolescent Depression Scale: Professional Manual. Odessa, FL: Psychological Assessment Resources; 1987. [Google Scholar]

- Reijntjes A, Kamphuis JH, Prinzie P, Telch MJ. Peer victimization and internalizing problems in children: A meta-analysis of longitudinal studies. Child Abuse & Neglect. 2010;34:244–252. doi: 10.1016/j.chiabu.2009.07.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rodkin PC, Farmer TW, Pearl R, Van Acker R. Heterogeneity of popular boys: Antisocial and prosocial configurations. Developmental Psychology. 2000;36:14–24. doi: 10.1037//0012-1649.36.1.14. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Salmivalli C, Isaacs J. Prospective relations among victimization, rejection, friendlessness, and children’s self- and peer-perceptions. Child Development. 2005;76:1161–1171. doi: 10.1111/j.1467-8624.2005.00842.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Scholte RHJ, Burk WJ, Overbeek G. Divergence in self- and peer-reported victimization and its association to concurrent and prospective adjustment. Journal of Youth and Adolescence, on-line. 2013 doi: 10.1007/s10964-012-9896-y. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schwartz D, Proctor LJ, Chien DH. The aggressive victim of bullying: emotional and behavioral dysregulation as a pathway to victimization by peers. In: Juvonen J, Graham S, editors. Peer harassment in school: The plight of the vulnerable and victimized. New York, NY: Guilford Press; 2001. pp. 147–174. [Google Scholar]

- Stormshak EA, Bierman KL the CPPRG. The implications of different developmental patterns of disruptive behavior problems for school adjustment. Development and Psychopathology. 1998;10:451–467. doi: 10.1017/s0954579498001692. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Taylor KA, Sullivan TN, Kliewer W. A longitudinal path analysis of peer victimization, threat appraisals to the self, and aggression, anxiety, and depression among urban African American adolescents. Journal of Youth and Adolescence. 2013;42:178–189. doi: 10.1007/s10964-012-9821-4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Troop-Gordon W, Ladd GW. Trajectories of peer victimization and perceptions of the self and schoolmates: Precursors to internalizing and externalizing problems. Child Development. 2005;76:1072–1091. doi: 10.1111/j.1467-8624.2005.00898.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vitaro F, Brendgen M. Proactive and reactive aggression: A developmental perspective. In: Tremblay RE, Hartup WW, Archer J, editors. The developmental origins of aggression. New York: The Guilford Press; 2005. pp. 202–222. [Google Scholar]