Abstract

In the present study, we examined the influence of kindergarten component skills on writing outcomes, both concurrently and longitudinally to first grade. Using data from 265 students, we investigated a model of writing development including attention regulation along with students’ reading, spelling, handwriting fluency, and oral language component skills. Results from structural equation modeling demonstrated that a model including attention was better fitting than a model with only language and literacy factors. Attention, a higher-order literacy factor related to reading and spelling proficiency, and automaticity in letter-writing were uniquely and positively related to compositional fluency in kindergarten. Attention and higher-order literacy factor were predictive of both composition quality and fluency in first grade, while oral language showed unique relations with first grade writing quality. Implications for writing development and instruction are discussed.

Keywords: component skills, beginning writing, kindergarten, first grade, writing development

The act of writing is a vehicle for the expression of knowledge and the transmission of information across time and generations. Most would agree that the ability to write is critical for success throughout the school years and into adulthood, where poor writing skills can have a detrimental impact in the work place (National Commission on Writing, 2005). Students in the United States have demonstrated relatively poor writing ability over time (National Assessment of Educational Progress; Salahu-Din, Persky, & Miller, 2008). The most recent National Assessment of Education Performance writing test results reported only 33% of eighth and 24% of twelfth grade students exhibited proficient writing skills, a result essentially unchanged from 2002. While these data relate to adolescents, Juel (1988) found that students exhibiting difficulty in the area of writing as early as the first grade were highly likely to remain poor writers in the fourth grade, suggesting that problems in writing may begin in the early grades..

In recent years there has been a notable increase in expectations for writing skills of students, beginning in kindergarten and first grade. Among the most recent writing standards for kindergarten and first grade are expectations for students to write about experiences, stories, people, and events by composing informational/explanatory texts with a topic and relevant facts and writing narratives that recount events sequentially (Common Core State Standards Initiative, 2010). Thus, research identifying the potential intractability of early writing difficulties, coupled with heightened expectations for writing, serves to emphasize the need for examining processes and components that influence writing development in the early elementary grades in order to provide possible targets of instruction, intervention and remediation. The present study sought to explore component skills of writing in the earliest years of schooling, kindergarten and first grade, by specifically investigating the relations of early literacy and language abilities, as well as attention, to the development of students’ compositional fluency and quality.

Component skills in early writing development

Some researchers have posited that the ability to write consists of attaining lower-level, more rudimentary skills such as spelling and handwriting (i.e., transcription skills) while also being able to utilize higher-level proficiencies such as creating, organizing, and elaborating ideas (The Simple View of Writing; Juel, Griffith, & Gough, 1986). More recently, Berninger and colleagues’ Not-So-Simple View of Writing (Berninger & Winn, 2006) suggests three primary components: (a) transcription; (b) executive functions regulating focused attention, inhibitory control, and mental shifting during planning, reviewing, and revising of text as well as strategies for self-regulation; and (c) text generation, or transformation of ideas to language representations in writing. In addition, reading component skills may also impact early writing as the two have been called “two sides of the same coin” (Ehri, 2000, p.19). Thus, one may postulate that early developmental differences in transcription, language, or reading skills, or attention and self-regulation, could impact the development of writing.

Transcription skills

There is converging evidence that spelling and handwriting are strong predictors of writing fluency and to some degree, compositional quality as students learn to write in the primary grades (Graham, Berninger, Abbott, Abbott, & Whitaker, 1997; Jones & Christensen, 1999; Juel, 1988; Juel et al., 1986). Graham and colleagues (1997) found that together, spelling and handwriting accounted for 25% and 66% of the variance in compositional quality and fluency, respectively, in Grades 1–3. Individually, after controlling for language ability, first grader’s spelling accounted for 29% of the variance in story writing in comparison to only 10% for students in fourth grade (Juel, 1988). Meanwhile, handwriting fluency has been shown to account for just over one-half of the variance in student’s quality of writing in first grade, even after accounting for reading (Jones & Christensen, 1999). In their recent meta-analysis, Graham, McKeown, Kiuhara, & Harris (2012) found that, on average, elementary students specifically taught transcription skills perform about one-half of a standard deviation (ES = .55) higher than comparison students on measures of writing quality. Most recently, Puranik and Al Otaiba (2012) found that in kindergarten, handwriting fluency and spelling added significant unique variance in predicting writing fluency after accounting for language, reading, and IQ.

Oral language

Investigating the contribution of oral language, primarily verbal reasoning and fluency, Abbott and Berninger (1993) found a statistically significant association with writing quality in first grade and compositional fluency in second and third grade. The structural relationships among the language systems of expressive language and writing have been found to generally change across development in Grades 1–3 with evidence suggesting strengthening relations over time (Berninger et al., 2006). However, less than 25% of the variance in writing achievement was accounted for by expressive language ability. Specific to kindergarten, Hooper et al. (2011) found that expressive and receptive language proficiency longitudinally predicted narrative writing skill in later elementary grades (third to fifth grades). Further, word and syntax-level language skills in kindergarten have demonstrated unique concurrent relations to compositional fluency after accounting for other literacy skills (Kim et al., 2011).

Reading

Given the multidimensional nature of both reading and writing processes, researchers have posited their important and reciprocal relationship may be due to shared knowledge (e.g., metaknowledge, knowledge of text attributes) and cognitive processes such as phonological and orthographic systems and short and long-term memory (Fitzgerald & Shanahan, 2000; Shanahan, 2006). It has been demonstrated that word and sentence-level reading ability contribute directly to spelling, handwriting, and compositional quality in Grades 1–6 and to compositional fluency in Grades 1–3, with the strongest relationship for fluency evident in first grade (Abbott & Berninger, 1993; Berninger, Abbott, Abbott, Graham, & Richards, 2002). Further, Abbott, Berninger, and Fayol (2010) found a longitudinal relationship between reading, specifically comprehension, and a measure of fluency and quality of writing across Grades 2–5.

Two recent studies have investigated several of these potential component skills of writing specifically for students in kindergarten (Kim et al., 2011; Puranik & Al Otaiba, 2012). Kim and colleagues’ (2011) findings supported a model of oral language, spelling, and letter-writing fluency, although reading had a non-significant relation to writing fluency after accounting for other skills. However, overall, only 33% of the variance in writing production was accounted for with these variables. Similarly, Puranik and Al Otaiba (2012) accounted for 39% of the variance in writing fluency with handwriting, spelling, reading, oral language, as well as cognitive and demographic factors. Both findings suggest the need to examine other component skills.

Regulation of Attention

As theorized in the Not-so-Simple-View of writing, executive functions, including supervisory attention, goal setting and planning, reviewing and revising, and strategies for self-monitoring and regulation, are critical to proficiency in text generation and are posited to increase in importance throughout development as the complexity of writing increases in schooling (Berninger & Winn, 2006). More specifically, Berninger and Winn view the supervisory attention system as responsible for selective attention during writing tasks; namely, focusing attention on relevant aspects of the task while inhibiting attention to non-relevant aspects, allowing shifting between mental sets, remaining on task, and metacognitive awareness. Specific executive functions that contribute to selective attention have been identified including inhibitory control, set-shifting, and updating of memory (Lehto, Juuarvi, Kooistra, & Pulkkinen, 2003; Wilcutt et al., 2001). Similarly, cognitive research from Happaney, Zelazo, and Stuss (2004) identified cognitive and attentional flexibility, and inhibitory control, along with working memory, as important to individual self-regulation. Hooper, Swartz, Wakely, de Kruif, and Montgomery (2002) have argued that problems with attentional control may particularly interfere with executive processes that coordinate strategic writing- planning, monitoring, and revising of writing. Barkley (1996) has hypothesized that inattention is a symptom of difficulty with self-regulation of internal cognitive processes. Given that the foundation for self-regulatory behavior occurs early in life, most often in the first five years (Blair, 2002), one would expect to see the influence of a self-regulatory skill such as attentional control, in the earliest grades.

Several studies have demonstrated the impact of attention on early academic outcomes, such as reading and math achievement, in preschool and early elementary grades (Duncan et al., 2007; McClelland, Acock, Piccinin, Rhea, & Stallings, 2013; Rhoades, Warren, Domitrovich, & Greenberg, 2011). One might argue that the ability to regulate attention would also impact early writing, as it allows students engaged in a writing task to specifically attend to relevant tasks and keep previous content written in mind for use in subsequent composing, all while disregarding extraneous information. With regards to writing, Hooper et al. (2002) found that less competent writers in fourth and fifth grade, in comparison to more able writers, demonstrated less proficiency with initiating and sustaining attention, inhibitory control, and set shifting. Subsequently, Hooper et al. (2011) identified a model of writing in first and second grade, including attention, memory, and executive functions, language, and fine motor ability, that accounted for nearly 50% of the variance in outcomes on a standardized measure of writing achievement. Attention/executive function was the only unique predictor of first grade writing while both language and attention/executive function uniquely predicted second grade writing. Teacher ratings of student attentiveness have also been shown to predict substantive quality of writing and writing convention as early as first grade (Kim, Al Otaiba, Folsom, & Greulich, 2013). Meanwhile, Thomson et al. (2005) have suggested that attention plays an indirect role in writing via influence on orthographic coding and rapid naming skills.

Intervention research has demonstrated that training student’s attentional processes (e.g., sustained, selective, and alternating attention), coupled with writing instruction, significantly improves compositional skills of students in fourth through sixth (Chenault, Thomson, Abbott, & Berninger, 2006). Further, many self-regulatory strategies utilized during writing, which focus student’s attention on the task, have been postulated including goal setting and planning, organizing, self-monitoring, self-verbalizing, and revising (Graham & Harris, 2000). The potential importance of such strategies during writing provided impetus for the development of the self-regulated strategy development approach, which subsequently has been proven effective across both grade and writing performance levels (e.g., Graham, Harris, & McKeown, 2013; Graham, McKeown, Kiuhara, & Harris, 2012; Graham & Perin, 2007).

Study Purpose and Research Questions

Although research interest in the area of writing has grown, the extant literature is still sparse at early developmental levels; only a few have specifically examined students as young as kindergarten (Kim et al., 2011; Puranik & Al Otaiba, 2012). While several component skills involved in writing development have been investigated and their potential importance demonstrated, most studies have examined only one or two of these component skills rather than the contribution of multiple component skills on writing. Although recent multivariate research of component skills at the early grades is encouraging (Hooper et al., 2011; Kim et al., 2011, 2013; Puranik & Al Otaiba, 2012), no study has yet examined the unique and shared role of attention, transcription, reading, and language ability in a model of writing development at the kindergarten level nor has the contribution of these skills been examined longitudinally in kindergarten and first grade.

Given the importance of language and literacy and attention skills to early learning, the purpose of the present study was to build upon and extend the extant literature on early writing development by examining four primary research questions (RQ). First,

What are the shared and unique relations of component skills of writing fluency in kindergarten by including attention, reading, transcription, and oral language skills?

Does a model of kindergarten writing development with an attention factor fit better than one without?

What are the longitudinal relations of kindergarten component skills to writing quality and fluency in first grade?

Do kindergarten component skills exhibit a direct effect on writing quality and/or fluency in first grade or are these relationships mediated by kindergarten writing fluency?

Method

Sample Characteristics

The present study examined extant data from a larger, five-year project examining a response to intervention framework for reading, including examination of general education classroom instruction for all students, within a school setting (Al Otaiba et al., 2011). Participants in the present analysis included one cohort of students who participated in the project in both kindergarten and first grade (n = 265).

In kindergarten, students represented 10 schools and 31 classrooms with a range of 1–15 students per participating classroom. The mean age in fall of kindergarten was 5.13 years of age. Sixty-one percent of the students qualified for free or reduced lunch programs, indicating a large proportion of the sample may be classified as low socio-economic status. The sample included 53.6% male students. Students represented a diversity of races/ethnicities, with 54% African American, 31% Caucasian, 8% Hispanic, 4% multi-racial, and less than 1% of Asian or Native American. Data on special education status were available for 253/265 (95%) students with approximately 11% eligible for services; most (over 70%) were identified with either a speech or language impairment. As demographic data was collected from schools, we were unable to obtain specific information relative to medical diagnoses such as Attention-Deficit Hyperactivity Disorder (ADHD). However, in this representative sample of students, only two (< 1%) students were eligible for special education as Other Health Impairment, a category often comprised of students with ADHD.

Measures

Transcription Skills

Student’s spelling and letter writing automaticity/fluency (accuracy and fluency in writing individual letters) were both assessed. On the spelling subtest from the WJ-III students write the corresponding graphemic representation of orally presented letters or words. Responses are scored dichotomously (correct or incorrect) on this measure. Median split-half reliability is .90. On a separate, untimed spelling measure students were presented 10 decodable or high-frequency words (e.g., dog, man, one, come) and 4 nonwords (e.g., sut, frot) used in previous literacy research (Byrne & Fielding-Barnsley, 1993). Using a standard protocol from Byrne et al. (2005), examiners explained to the students that some presented words were real and some were nonwords. All real words were presented orally, used in a sentence, and then repeated, while nonwords were repeated three times. Student performance on each word was assigned a development score ranging from 0 to 6 based on modification of a rubric from Tangel and Blachman (1992). A developmental score, in contrast to a dichotomous score was chosen given the age of the sample in order to capture differences in how students orthographically represented phonological word features. This scoring method has been utilized in recent studies with kindergarten students and in previous research (Jones & Christensen, 1999; Kim et al., 2011; Puranik & Al Otaiba, 2012). The following guidelines were utilized: no response or a random string of letters was assigned a 0, providing at least one letter that was related to the target spelling word phonetically was scored as a 1 (e.g., writing an “o” or “g” for dog), writing the correct initial letter followed by random letters was scored as a 2, including more than one correct phoneme resulted in a score of 3, a score of 4 was given for words spelled with all letters represented and phonetically correct (e.g., “dawg” for dog), a 5 was assigned when all requirements of a score of 4 were met and student made an attempt to mark a long vowel (e.g., “bloo” for blue), and a word received a score of 6 when spelled correctly.

Student’s ability to access, retrieve, and automatically write letter forms was also measured. The task was modified from Berninger and Rutberg’s (1992) task of handwriting automaticity. Students were given 1 min to write, quickly and accurately, all lower case letters of the alphabet in order (Jones & Christensen, 1999; Wagner et al., 2011). Consistent with prior research, the letter writing fluency (LWF) task was scored primarily on penmanship and correct letter formation with a score of 1.0 given for a letter that was correctly formed and sequenced, .5 for letters poorly formed yet recognizable and/or reversed, and 0 for illegible letters, cursive letters, letters written out of order, or uppercase letters.

Oral Language

Student’s oral language ability was assessed using measures of word and syntax knowledge. Expressive vocabulary was assessed using the Picture Vocabulary subtest of the WJ-III (Woodcock, McGrew, & Mather, 2001). Students were presented with pictures of common objects and asked to say the word depicted in the picture. The reported median split-half reliability was .77. Knowledge of syntax, or grammar, was measured by the Grammatic Completion subtest of the Test of Language Development—Primary, third edition (TOLD-P: 3; Newcomer & Hamill, 1997). This task, measures the ability to use various morphological forms found in English (e.g., “Here is a cat. Over there are four more ___ .”). The Sentence Imitation subtest of the TOLD-P: 3 (30 items), measuring auditory short-term memory and grammatical understanding, was also administered. Students were asked to repeat sentences that increase in length and complexity. Reliability was reported to be .90 and .91 respectively, for these subtests.

Reading Skills

Three measures of letter and word reading and decoding were utilized as indicators of student’s reading ability in kindergarten. On the Woodcock-Johnson (WJ-III) Letter-Word Identification subtest (Woodcock, McGrew, & Mather, 2001), which includes 76 items increasing in difficulty, students were required to name individual letters, as well as decode and/or identify real words presented. Median split-half reliability was reported to be .94 for this measure. Decoding skill was measured using the WJ-III Word Attack subtest. Utilizing pseudowords, items proceed from identification of a few single letter sounds to decoding of complex letter combinations. Reported median split-half reliability was .87. The ability to decode phonetically regular words fluently and accurately was assessed using the Phonemic Decoding Efficiency (PDE) subtest of the Test of Word Reading Efficiency (TOWRE; Torgesen, Wagner, & Rashotte, 1999). The PDE measures the number of pronounceable nonwords accurately decoded within 45s. Reported test-retest reliability was .90.

Attention

Student’s attention regulation was assessed through teacher report using the Strengths and Weaknesses of ADHD-symptoms and Normal behavior scale (SWAN; Swanson et al., 2006). This 30-item scale, assessing students’ attention-based behavior was completed by classroom teachers. Some example items include “Engage in tasks that require sustained mental effort” and “Remain focused on task”. Students are rated in comparison to their peers along a 7- point continuum that ranges from “far below” to “far above”, based upon observations made over the past month (Swanson et al., 2006). The Diagnostic and Statistical Manual (DSM-IV; American Psychiatric Association, 2000) criteria used for identifying individuals with Attention Deficit Hyperactivity Disorder was utilized in the development of the SWAN. Although the SWAN is frequently used as one aspect in an ADHD evaluation, it also provides a direct measure of student’s attention skills across a continuum. Recent research (Saez, Folsom, Al Otaiba, & Schatschneider, 2012) has supported the items on the SWAN as representing three separable factors of selective attention, including attention-memory, attention-set shifting, and attention- inhibitory control, which align with the specific components of self-regulation described by previous research (Happaney et al., 2004; Lehto et al., 2003; Wilcutt et al., 2001). The mean score across the items representing each of these three factors was calculated to form three indicators of selective attention. Cronbach’s alpha for this measure across all 30 items was .99.

Writing Skills

In the spring of kindergarten, students were asked to compose a writing sample in response to an examiner-presented prompt. Examiners introduced the task and facilitated a brief group discussion to orient students to expectations. Specifically, examiners said, “You have been in kindergarten for almost a whole year. Today we are going to write about kindergarten. Let’s think about what you enjoyed about being in kindergarten. What did you learn in school? Did anything special happen to you in kindergarten?” These questions and student responses were not written down by examiners. Examiners also instructed students to write what they had learned in kindergarten until instructed to stop and that they could not receive help with spelling words. Students were allowed 15 min to complete the task. This specific researcher-developed task was developed in response to the lack of validated measures to assess students writing in kindergarten.

Students’ writing was scored for the number of words, sentences, and ideas using a coding scheme developed by Puranik, Lombardino, and Altmann (2007). Due to limited production, scoring of correct word sequences (CWS) was not suitable in kindergarten. All actual words, explicitly related to the prompt, that students composed were counted in the computation for the number of words written (e.g., “The end” was not counted), while number symbols and random letters were not counted. All complete sentences were counted in the total number of sentences, regardless of punctuation. When punctuation was absent, raters broke the writing into sentences with the criteria that a sentence had to express a complete thought, feeling, or idea and have an explicit or implied subject and predicate with a verb (e.g., “I eat and play [STOP] and go outside and laugh [STOP] and draw pictures.” counted as three sentences). For calculating the number of ideas in a student’s writing sample, only ideas that could be identified in the writing were counted, Ideas required a subject and a predicate, but could use a common subject/verb (e.g., “I like playing” would be scored as one idea; “I like playing and writing” would count as two ideas). Repeated ideas were only counted once. These scoring measures for writing fluency (i.e., production) have been utilized in previous studies with students in the earliest grades (Kim et al., 2011, in press).

In the spring of first grade, students were asked to compose a brief narrative text when presented with a story prompt (i.e., One day when I got home from school …’) developed by curriculum based writing researchers (McMaster, Du, & Petursdorrir, 2009). Brief 5 min prompts are widely used in writing research as global indicators of writing performance in first grade and also through the elementary grades (Lembke, Deno, & Hall, 2003). Students’ writing was evaluated in two different ways. First, analytic scoring of student essays for the following components was completed: organization of text structure (e.g., beginning, middle, and end), ideas (e.g., development of main idea), word choice (e.g., use of specific/interesting words), and sentence fluency (e.g., grammatical use of sentences and sentence flow). These components of writing were adapted from the widely utilized 6 + 1 Traits of Writing Rubric for Primary Grades (NREL, 2011). These four components were recently identified as representing a separable factor in students’ writing, capturing substantive quality (Kim et al., in press). Second, writing was evaluated for the number of CWS, a commonly used metric within curriculum-based writing measures; in the present study, CWS serves as a proxy for writing fluency in first grade. For writing quality each domain was assigned a score from 1 (“experimenting”) through 5 (“experienced”) based on the degree of proficiency exhibited in the writing. A score of 0 was assigned for each trait if the student’s writing sample was unscorable due to being illegible, the student did not produce any writing, or the student simply rewrote the prompt. For CWS, a word sequence was defined as the sequence between two adjacent words or between a word and punctuation mark. For a sequence to be scored as a CWS, the adjacent words must be spelled correctly and be syntactically and semantically correct within the writing context. To take into account the beginning and end of sentences, the beginning word must be capitalized and the end of the sentence properly punctuated in order to receive a CWS for those writing sequences. All CWS in the student’s writing were summed to create a total score.

Procedures

Reading, spelling, and letter writing fluency assessments for the current study were collected during spring of kindergarten as was the WJ-III Picture Vocabulary measure. The additional oral language measures from the TOLD-P: 3 were part of the fall of kindergarten assessment battery. Writing samples were collected at the end of both kindergarten and first grade. Trained research assistants (RA) served as examiners. Reading and oral language assessments were administered individually, whereas spelling and writing assessments were done in small groups or entire classrooms. Letter-writing fluency, spelling, and writing quality were all scored by trained research assistants using specific rubrics.

For LWF, spelling, and writing scoring, RAs were trained to use each rubric on a small subset of the sample through practice and discussion of scoring issues. A randomly selected 15% of the complete data set for LWF and spelling were scored by each RA individually to calculate reliability. Kappa was .98 for letter-writing fluency and .99 for spelling. For writing samples, interrater reliability for each variable coded was calculated on a random selection of 20% of writing samples. For writing scoring in kindergarten, agreement averaged 88% for total number of words, sentences, and ideas. For first grade samples, inter-rater agreement was 92% for CWS and averaged 91% across the quality components. All discrepancies in scoring were resolved through discussion.

Data Analysis

Confirmatory factor analysis (CFA) and structural equation modeling (SEM) were utilized to answer the research questions. Initially, the appropriateness of the measurement model was established utilizing CFA including latent factors of reading, spelling, letter-writing fluency, oral language, attention, and writing production in kindergarten and writing quality in first grade. While all observed measures of most latent constructs were collected in spring, students’ scores from the TOLD-P: 3 subtests collected in fall of kindergarten were utilized to create an oral language factor. Correlations between the TOLD-P:3 subtests in fall and a vocabulary measure in the spring ranged from .39 to .49 and were statistically significant. Next, a series of SEMs were specified to address the research questions: Model 1- Kindergarten component factors and a single-indicator of letter writing fluency predicting kindergarten writing fluency (research question 1); Model 2- Same as model 1 but with all covariances with, and direct paths from, the attention factor constrained to 0 (RQ 2); Model 3- Kindergarten component skills predicting first grade writing quality and writing fluency (RQ 3); and Model 4- kindergarten factors predicting kindergarten writing production and direct and indirect effects on first grade writing quality and fluency (RQ 4). Measurement error for single indicators of letter-writing fluency and the writing production fluency in kindergarten was accounted for by fixing the residual variances of each observed variable (i.e., [1- reliability]* σ2). Multiple indices were evaluated to assess model fit including chi-square, root mean square error of approximation (RMSEA), comparative fit index (CFI), Tucker-Lewis Index (TLI), and standardized root mean square residuals (SRMR). Given that chi-square values tend to be influenced by sample size, RMSEA values below .085, CFI/TLI values greater than .95, and SRMR below .05 indicate excellent model fit (Kline, 2011).

To account for the non-independence of observations, cluster-corrected standard errors using CLUSTER option and TYPE=COMPLEX in Mplus 6.1 were derived. This approach is an appropriate method for accounting for the nested nature of data without specifically answering questions about variance components at different levels (Asparouhov, 2006). However, for analyses purposes, clusters (i.e., classrooms) with less than 5 students were removed resulting in removal of seven clusters and 10 students. There were no statistically significant differences in sample means for any variable with removal of these 10 cases.

As the extant data utilized in these analyses was collected on students in school, missing data was to be expected. Complete data were available for 195 students, or close to 75% of participants. Missing data was treated as missing at random, which Mplus handles using full-information maximum likelihood estimation.

Results

Descriptive Statistics

Descriptive statistics are presented in Table 1 and where available, standard scores are provided in addition to raw scores. Students in the sample demonstrated mean scores within the average range for word reading, decoding, spelling, and expressive vocabulary, while grammar/syntax skills were low average to below average. Sample means for each area of attention were consistent (M = 4.59–4.69). Kindergarten writing production averaged almost 13 words (0–50). Approximately one in five (22%) kindergarten writing samples were either unscorable due to illegibility or the student was unable to compose any actual words suggesting the presence of a floor effect on this measure. In first grade, students averaged 32 words written (SD = 14.5) and 21 CWS (SD = 12.4) for the narrative writing prompt. Mean ratings on each of the first grade writing quality components ranged from a low of 2.45 on Word Choice to a high of 2.95 for Ideas with only three prompts deemed unscorable. Table 2 presents bivariate correlations among observed variables, all of which were statistically significant (p < .01).

Table 1.

Descriptive Statistics

| M | SD | Range | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Kindergarten Writing Fluency | |||

| Total number of wordsa | 12.64 | 11.3 | 0–50 |

| Total number of ideasa | 2.23 | 2.4 | 0–11 |

| Total number of sentencesa | 1.7 | 2.1 | 0–11 |

| Writing Quality | |||

| Ideasb | 2.95 | .72 | 0–4 |

| Structureb | 2.77 | .66 | 0–4 |

| Word Choiceb | 2.45 | .73 | 0–4 |

| Grammarb | 2.78 | .62 | 0–4 |

| First Grade Writing Fluency | |||

| Correct Writing Sequencesc | 20.80 | 12.4 | 1–61 |

| Reading | |||

| Letter Word Identification – raw scored | 23.99 | 7.8 | 11–52 |

| Letter Word Identification – standard scored | 108.81 | 14.2 | 80–149 |

| Word Attack- raw scoree | 7.64 | 5.2 | 2–27 |

| Word Attack- standard scoree | 112.25 | 13.0 | 78–141 |

| Phonemic Decoding efficiency – raw scoree | 7.05 | 7.9 | 0 – 43 |

| Spelling | |||

| WJ Spelling- raw scoree | 16.28 | 3.9 | 2–29 |

| WJ Spelling- standard scoree | 104.92 | 14.6 | 31–137 |

| Byrne Spelling Taskf | 49.06 | 18.3 | 0–82 |

| Letter writing fluencyg | 10.46 | 5.5 | .5–25 |

| Oral Language | |||

| Picture Vocabulary- raw scored | 18.19 | 2.8 | 12–28 |

| Picture Vocabulary- standard scored | 101.41 | 9.7 | 76–140 |

| TOLD Sentence Imitation- raw scoreh | 8.35 | 5.9 | 0–28 |

| TOLD Sentence Imitation- standard scoreh | 8.29 | 3.0 | 2–20 |

| TOLD Grammatic Completion- raw scoreh | 6.60 | 5.5 | 0–24 |

| TOLD Grammatic Completion- std. scoreh | 7.61 | 2.9 | 1–17 |

| Attention | |||

| SWAN- Memoryi | 4.59 | 1.6 | 1–7 |

| SWAN- Set Shiftingi | 4.70 | 1.7 | 1–7 |

| SWAN- Inhibitory Controli | 4.49 | 1.6 | 1–7 |

Note.

n= 238;

n= 265;

n= 264;

n= 253;

n= 252;

n= 232;

n= 214;

n= 257;

n=249

Table 2.

Correlations between observed variables

| 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | 6 | 7 | 8 | 9 | 10 | 11 | 12 | 13 | 14 | 15 | 16 | 17 | 18 | 19 | 20 | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Reading | 1. LWID | --- | |||||||||||||||||||

| 2. WA | .81 | --- | |||||||||||||||||||

| 3. PDE | .84 | .84 | --- | ||||||||||||||||||

| Transcription | 4. WJ Spelling | .84 | .75 | .73 | --- | ||||||||||||||||

| 5. Spelling: Informal | .77 | .69 | .65 | .77 | --- | ||||||||||||||||

| 6. LWF | .46 | .41 | .41 | .50 | .48 | --- | |||||||||||||||

| Oral Language | 7. PV | .42 | .47 | .41 | .37 | .38 | .24 | --- | |||||||||||||

| 8. TOLD-SI | .36 | .39 | .36 | .32 | .40 | .22 | .39 | --- | |||||||||||||

| 9. TOLD- GC | .42 | .45 | .38 | .34 | .42 | .36 | .49 | .60 | --- | ||||||||||||

| Attention | 10. SWAN: Memory | .47 | .42 | .40 | .44 | .54 | .46 | .19 | .26 | .37 | --- | ||||||||||

| 11. SWAN: Set Shift | .38 | .33 | .34 | .32 | .38 | .32 | .15 | .18 | .24 | .71 | --- | ||||||||||

| 12. SWAN: Inhibitory Control | .37 | .31 | .31 | .33 | .44 | .37 | .15 | .21 | .30 | .83 | .83 | --- | |||||||||

| K Fluency | 13. Words | .60 | .50 | .53 | .59 | .62 | .48 | .16 | .29 | .27 | .44 | .41 | .39 | --- | |||||||

| 14. Sent. | .44 | .37 | .40 | .44 | .51 | .41 | .15 | .21 | .26 | .42 | .37 | .39 | .82 | --- | |||||||

| 15. Ideas | .52 | .47 | .49 | .52 | .58 | .47 | .20 | .26 | .29 | .42 | .36 | .38 | .87 | .90 | --- | ||||||

| First Grade Quality | 16. Ideas | .28 | .27 | .26 | .31 | .34 | .24 | .17 | .23 | .24 | .23 | .16 | .21 | .26 | .23 | .25 | --- | ||||

| 17. Structure | .33 | .26 | .28 | .34 | .34 | .20 | .20 | .15 | .19 | .27 | .17 | .26 | .27 | .20 | .22 | .56 | --- | ||||

| 18. Word Choice | .28 | .27 | .27 | .33 | .32 | .21 | .23 | .20 | .24 | .26 | .18 | .26 | .24 | .23 | .21 | .50 | .46 | --- | |||

| 19. Grammar | .39 | .32 | .35 | .41 | .44 | .28 | .17 | .29 | .35 | .40 | .29 | .35 | .33 | .27 | .30 | .57 | .61 | .46 | --- | ||

| First Grade Fluency | 20. CWS | .60 | .44 | .49 | .54 | .53 | .33 | .16 | .30 | .25 | .46 | .40 | .42 | .51 | .46 | .47 | .37 | .36 | .27 | .58 | --- |

Note. All coefficients are statistically significant at .05 level.

LWID= Letter-Word Identification; WA= Word Attack; PDE= Phonemic Decoding Efficiency; LWF= Letter Writing Fluency; PV= Picture Vocabulary; TOLD-SI= Test of Language Development Sentence Imitation; TOLD-GC= Test of Language Development Grammatic Completion; CWS= Correct writing sequences

Measurement Model

Initial evaluation of the fit indices for the proposed measurement model indicated excellent data fit: χ2 (119) = 234.62, p =.000; CFI= .963; TLI = .952; RMSEA = .060 (CI [ .049, .072]); and SRMR = .048. All predictor factors were significantly and positively related to one another (.33 ≤ r ≤ .95) and with writing in kindergarten and first grade, with generally moderate correlations (see Table 3). Reading and spelling factors were very highly related (r = .95). Given approximately 90% of the variance in one factor was accounted for by the other suggested that the two constructs may be captured by a second-order factor (e.g., global early literacy skills). Previous research has suggested a unitary language and literacy construct at first grade (Mehta, Foorman, Branum-Martin, & Taylor, 2005).

Table 3.

Correlations among reading, spelling, letter-writing fluency, oral language, self-regulation, and writing

| Reading | Spelling | Letter- Writing Fluency |

Oral Language |

Attention | K Writing Production |

First Writing Quality |

|

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Spelling | .95 | --- | |||||

| Letter-Writing Fluency | .51 | .54 | --- | ||||

| Oral Language | .54 | .57 | .40 | --- | |||

| Attention | .45 | .47 | .42 | .35 | --- | ||

| K Writing Production | .64 | .67 | .47 | .35 | .45 | --- | |

| First Writing Quality | .50 | .53 | .31 | .42 | .40 | .37 | --- |

| First Writing Production | .60 | .64 | .34 | .33 | .47 | .52 | .61 |

Note. All coefficients are statistically significant at the .01 level.

K = Kindergarten; First = First grade

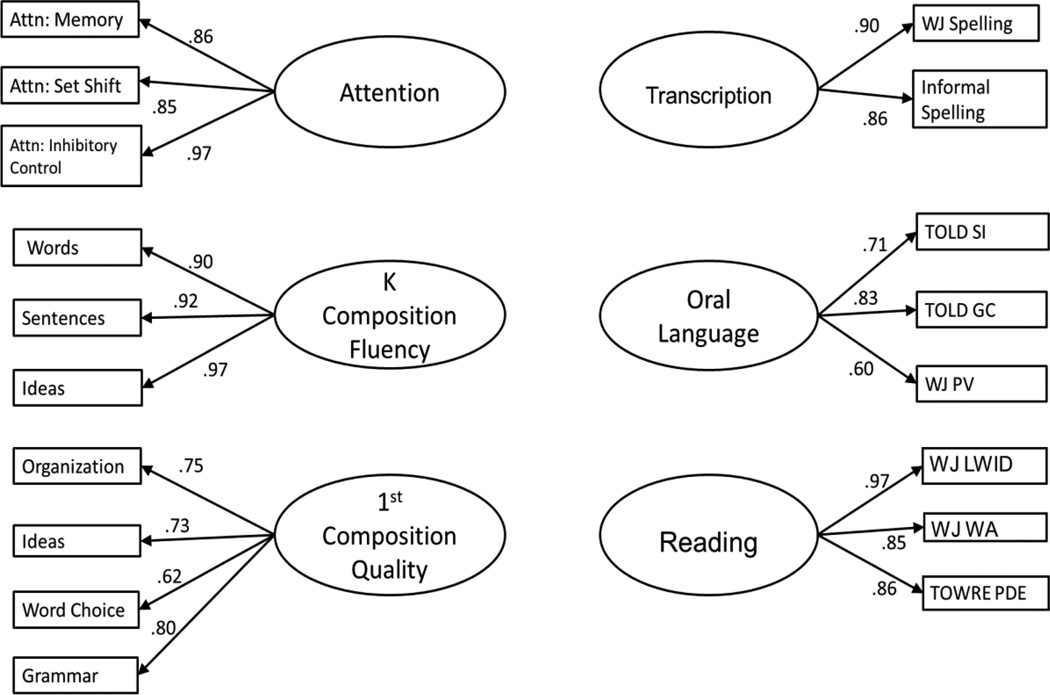

For this reason, CFA was used to examine whether an alternative model with a second-order “literacy” might better explain the data than the existing correlated factors model. The alternative model also demonstrated good fit [χ2 (123) = 243.21, p =.000; CFI = .961; TLI = .952; RMSEA = .061 (CI[.049,.072]); and SRMR = .049]. Results from a chi-square difference test (Δχ2 = 8.84, df = 4, p = .065) suggest this more parsimonious model would be preferred and thus, was used in subsequent analyses.1 Figure 1 displays factor loadings for each latent factor.

Figure 1.

Factor loadings for kindergarten and first grade latent variables

Research Questions 1 & 2

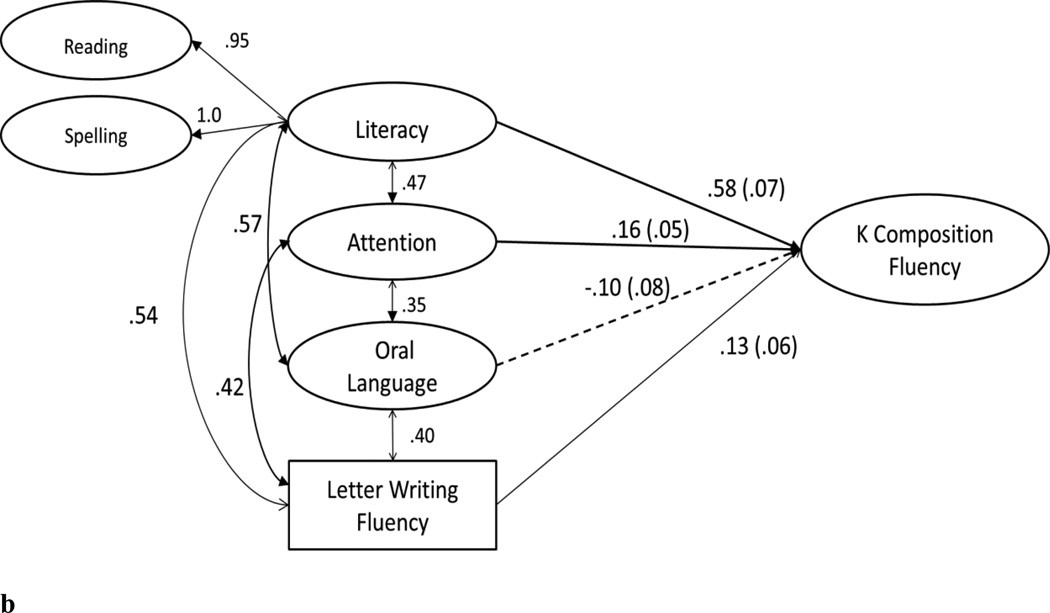

The first research question addressed the unique and shared relations of component skills of writing fluency in kindergarten. Standardized parameter estimates and standard errors for the hypothesized SEM of writing production in kindergarten, are presented in Figure 2a. Results suggested good model fit: χ2 (79) = 186.53, p =.000; CFI = .965; TLI = .954; RMSEA = .076 (CI [.062, .090]); and SRMR = .050. Literacy (i.e., reading and spelling), letter-writing fluency, oral language, and attention were all positively related to one another (φ range = .35–.57, ps < .01). Attention-related skills (γ = .16, p = .001) exhibited a unique and statistically significant relation to kindergarten composition fluency after controlling for literacy, handwriting fluency, and oral language. Early literacy skill in reading and spelling (γ = .58, p < .001), as well as letter-writing fluency (γ = .13, p = .047) were also uniquely and positively related to students’ composition fluency, while oral language (γ = −.10, p = .237) demonstrated no relationship when accounting for the other factors. This model accounted for approximately 49% of the variance in compositional fluency in kindergarten.

Figure 2.

Standardized structural regression weights (standard errors in parentheses) for SEM of kindergarten component skills and writing (a) and model with attention constrained to 0 (b). Solid lines represent p < .01; dashed lines p > .05; dotted lines represent paths constrained at 0

For the second research question, we further sought to confirm the appropriateness of including attention in the model in comparison to a model with only literacy, letter-writing fluency, and oral language as predictors of writing production (Figure 2b). The model including attention had a statistically significant better fit than a model without this factor (Δχ2 = 73.5, df = 4, p < .001) supporting its inclusion.

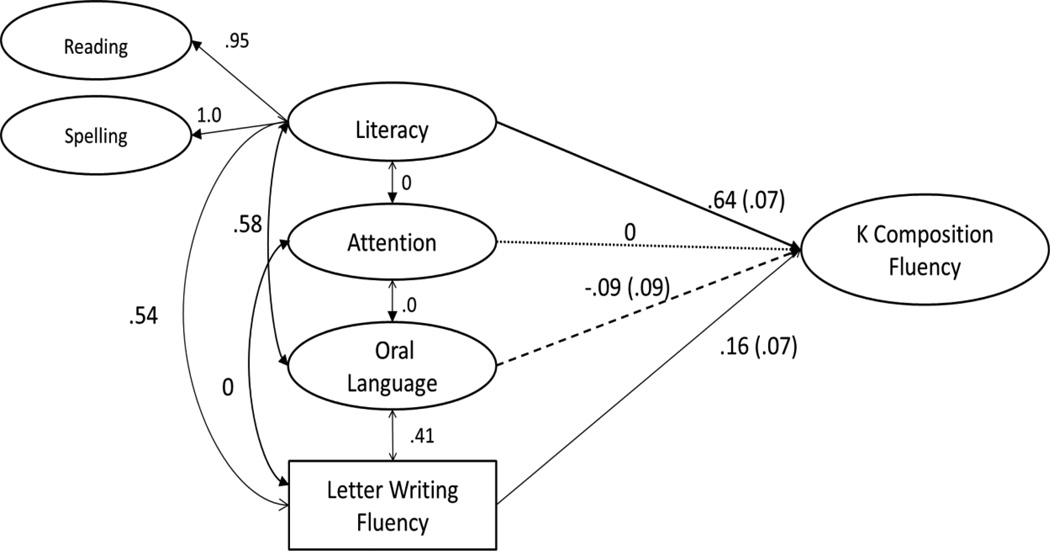

Research Question 3

The third research question considered the longitudinal relations of kindergarten component skills to first grade writing. As presented in Figure 3, a SEM predicting compositional fluency and quality in first grade from kindergarten component skills exhibited excellent fit: χ2 (104) = 203.32, p = .000; CFI = .964; TLI = .953; RMSEA = .061 (CI [.049, .074]); and SRMR = .047. In this longitudinal model, attention in kindergarten was uniquely related to both compositional fluency (γ = .23, p < .001) and quality (γ = .19, p = .001) in first grade after accounting for the other factors. Literacy skills in kindergarten were also uniquely and positively related to fluency (γ = .60, p < .001) and quality (γ = .36, p < .001) of writing in the spring of first grade, while kindergarten letter-writing fluency exhibited no statistically significant relationship to either first grade outcome (γ = −.05 and −.03, ps > .41). Oral language skills in kindergarten were not uniquely related to compositional fluency in first grade (γ = −.07 p = .50) but did exhibit a unique relation to quality of writing in first grade (γ = .16 p = .05). Compositional fluency and quality were moderately related (φ = .42, p < .001). Overall, the model accounted for 33% and 45% of the variance in compositional quality and fluency respectively, in first grade.

Figure 3.

Standardized SEM coefficients (standard errors) for kindergarten component skills predicting 1st grade writing quality and fluency. Solid lines represent p < .01, dashed lines represent p > .05

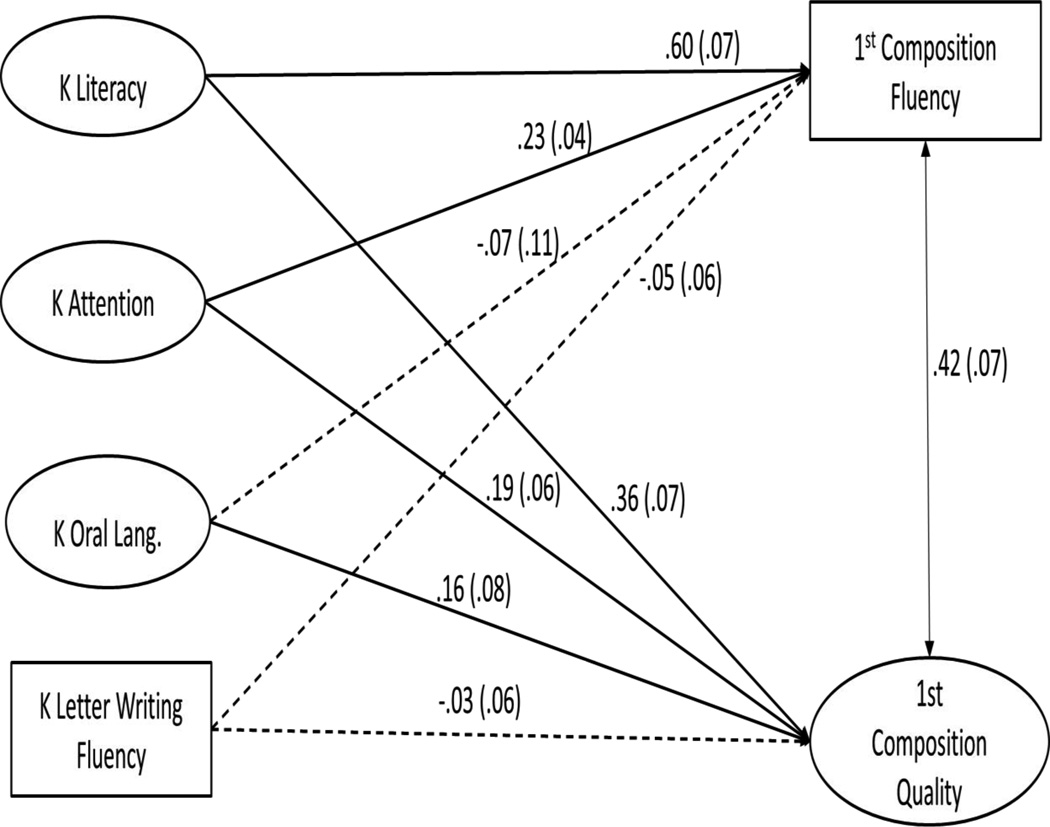

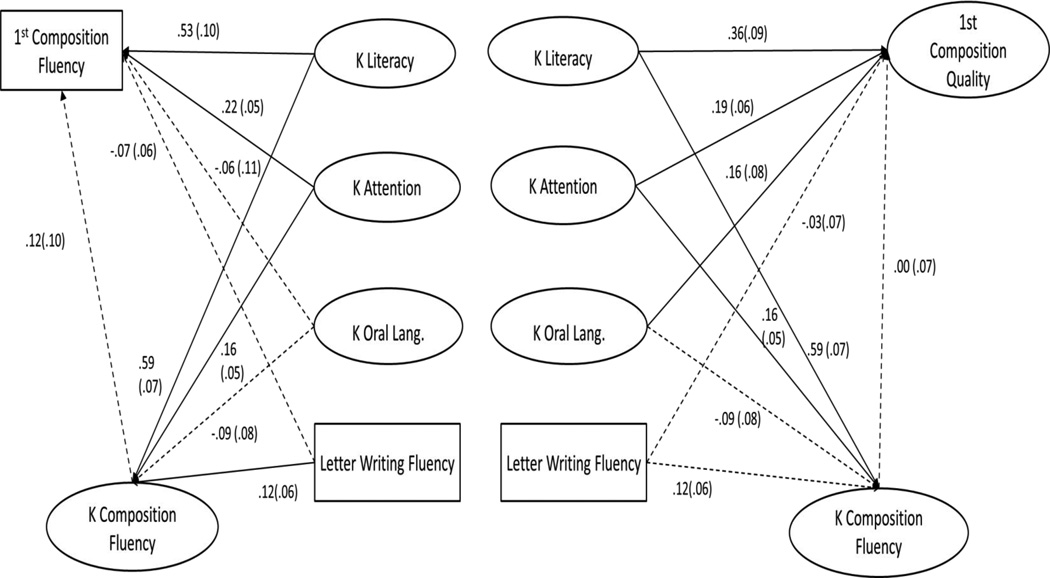

Research Question 4

The final question examined whether kindergarten component skills had a direct or indirect effect on first grade writing quality and fluency. The resulting model (see Figure 4) again demonstrated excellent model-data fit: χ2 (149) = 289.34, p = .000; CFI = .962; TLI = .951; RMSEA = .061 (CI [.050, .071]); and SRMR = .046. After accounting for both compositional fluency in kindergarten and all other component skills, attention (γ = .19, p < .01), literacy skills (γ = .36, p < .001) and oral language (γ = .16, p = .05) in kindergarten exhibited statistically significant direct paths to first grade writing quality. Direct effects to first grade compositional fluency were only statistically significant for attention (γ = .22, p < .01) and early literacy (γ = .53, p < .01), while oral language had no unique relation (γ = −.06, p = .55). Letter-writing fluency demonstrated no unique relationship with composition fluency or quality in this model. Despite the moderate factor correlations between fluency of written composition in kindergarten and first grade compositional quality (r = .37) and fluency (r =.52), kindergarten writing was not predictive of either writing quality (γ = .00, p = .99) or fluency (γ = .12, p = .24) in first grade, after accounting for the direct effects of kindergarten component skills. Thus, kindergarten writing fluency does not appear to mediate the relationship between kindergarten component skills and writing quality or production one year later. This model accounted for approximately 33% of the variance in writing quality and 45% of the variance in first grade writing production. A summary of model-fit statistics for all CFA and SEMs is presented in Table 4.

Figure 4.

Full SEM with standardized structural regression weights (standard errors) of direct and indirect effects of kindergarten component skills on 1st grade writing quality and fluency. Solid lines represent p< .01, dashed lines represent p>.05. Model separated by outcome for presentation purposes

Table 4.

Model Fit Statistics for CFA and SEM

| Model | χ2 (df) |

RMSEA (CI) |

CFI | TLI | SRMR | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| CFA | Correlated Factors | 234.62 (119) | .060 (.049−.072) | .963 | .952 | .048 |

| 2nd Order Literacy Factor | 243.21 (123) | .061 (.049−.072) | .961 | .952 | .049 | |

| SEM | Concurrent | 186.53 (79) | .074 (.060−.088) | .965 | .954 | .050 |

| Concurrent without Attention Factor | 260.03 (83) | .093 (.008−.106) | .942 | .927 | .193 | |

| Longitudinal: Direct Effects | 203.32 (104) | .061 (.049−.074) | .964 | .953 | .047 | |

| Longitudinal: Direct & Indirect Effects | 289.34 (149) | .061 (.050−.071) | .962 | .951 | .046 | |

Note. RMSEA = root mean square error of approximation; CFI = comparative fit index; TLI = Tucker-Lewis index; SRMR = standardized root mean square residuals; CI = confidence interval.

Discussion

The present study provides preliminary findings regarding early predictors of writing development. Based on longitudinal data collected on a diverse sample of students in their kindergarten and first grade years, evidence supports a model of early writing including attention as a component factor given its unique relation to compositional fluency and quality above and beyond early literacy and language ability. An early literacy factor, related to word reading and spelling proficiency, accounted for statistically significant variation in concurrent and future writing outcomes. Student’s handwriting automaticity in kindergarten showed a unique, concurrent relation to fluency of composition but not to writing quality and fluency one year later. Finally, after accounting for other component skills, kindergarten oral language was only related to quality of writing in first grade. Of particular note, all statistically significant relations of component skills, both concurrently and longitudinally, to writing outcomes were direct effects.

Substantiating the important role of attention, an aspect of self-regulation, in writing development serves to bolster previous research findings of this relationship in older grades (Graham and Harris, 2000; Hooper et al., 2002, 2011) and extend recent evidence with students at this young age (e.g., Kim et al., 2013). Difficulties in working memory and attention, both assessed in the present analyses, have been linked to poor writing outcomes in both lower and upper elementary grades (Chenault et al., 2006; Kim et al., 2013), and this study provides emerging evidence of this role in writing development as early as kindergarten. To our knowledge, the present results are the first to examine a component skill model of early writing in kindergarten, and longitudinally to first grade, that includes attention with literacy and language-related skills. Given constraints in self-regulatory processes such as attention during writing, novice writers have been previously described as engaging in “knowledge-telling”, with a primary focus on the act of putting thoughts to words on paper (Bereiter & Scardamalia, 1987; McCutchen, 2000). Our findings suggest that higher levels of attention regulation at this emergent level may free cognitive resources to assist not only in efficient text production by allowing students to remain engaged, abstain from competing demands, and transfer ideas and thoughts to the written word, but also engage in self-regulatory strategies during writing that promote higher quality compositions. While strategies such as goal-setting, planning, and revising has been attributed to older and more skilled writers (Bereiter & Scardamalia, 1987), it is possible that students, particularly those with better attention skills, may begin to develop these strategies at an earlier age.

The individual relations of reading and spelling could not be modeled due to the extreme overlap with these two factors. As previously stated, this finding is not without precedent at this age level (Mehta et al., 2005). Nonetheless, the important role of early literacy on kindergarten writing fluency, as well as both composition fluency and quality one year later, was clearly evident. Both reading and spelling are influenced by phonological, orthographic, and morphological knowledge (Berninger et al., 2002). One could reason that stronger knowledge in these areas facilitates access to written text via reading and subsequently, better understanding of the written language system, potentially aiding the generation of written text. Further, greater phonological, orthographic, and morphological knowledge may allow students to form a lexicon of letter/word forms that can be accessed quickly and accurately (Berninger et al., 2006) and thus, allows ideas to be represented in text at the word, sentence, and discourse levels through efficient encoding.

Automaticity in handwriting also had a small, yet statistically significant relation to the efficient production of words, sentences, and ideas in writing in kindergarten, clearly supporting the extant research with students in the earliest grades (Jones & Christensen, 1999; Kim et al., 2011; Puranik & Al Otaiba, 2012). Although a separable construct, letter-writing fluency, which was moderately correlated with spelling (φ = .54), likely operates similarly to automaticity in spelling skill in that without automatic retrieval of letter forms, generating text becomes slow and effortful and the strategic thought processes required for writing are impeded, particularly on timed measures of writing (Graham et al., 1997; McCutchen, 2000). Of note was the absence of relation between handwriting fluency in kindergarten and writing outcomes one year later. Although evidence exists supporting the role of handwriting fluency on writing in first grade (e.g., Jones & Christensen, 1999; Kim et al., 2013), the present study did not include concurrent measures of these skills in first grade.

The relations of oral language to writing outcomes were mixed, with a small, yet statistically significant finding for writing quality but not compositional fluency. This supports research at the earliest grades demonstrating individual differences in oral language were not related to writing fluency when accounting for other factors (Abbott & Berninger, 1993; Puranik & Al Otaiba, 2012). Our findings do however differ from the Kim et al. (2011) finding of oral language as a unique predictor of writing fluency in kindergarten. The act of writing requires the development and elaboration of ideas and therefore, limitations in children’s vocabulary and knowledge of language structures may serve to constrain the quality of text generated (McCutchen, 2000). Prior research has established the relations between oral language and writing increase across the early grades (Abbott & Berninger, 1993; Berninger et al., 2006), it is plausible that the importance of oral language to compositional quality grows across the grades much like it does to reading comprehension after the earliest grades (Storch & Whitehurst, 2002). Furthermore, Juel and colleagues (Juel, 1988; Juel et al., 1986) have also found that student’s ideation, likely related to language ability, becomes more important to writing after first grade. It may be that larger relations are apparent after first grade because writing production for students becomes less constrained, and thus, individual differences in language skills are more evident in the quality of composition.

In general, findings suggest that students’ literacy and language skills may work in tandem with self-regulatory functions such as attention to influence writing at this early level. Our findings clearly dovetail with results from other studies (Kim et al., 2011, 2013; Puranik & Al Otaiba, 2012) demonstrating the role of early component skills of writing including language and literacy skills, as well as regulation of attention. However, the present study further adds to our understanding of their influence over time (i.e., longitudinally). So, while knowledge of the writing system (e.g., Fitzgerald & Shanahan, 2000), automaticity with transcription, and oral language proficiency appear necessary for early writing development, they may not be sufficient. Individual differences in level of attention also play a role efficient text production (fluency) and qualitative elements of writing such as ideation, organization, structure, and word choice for these early writers. Berninger and Winn’s (2006) view of text generation posits that executive functions, particularly supervisory attention, do play a role in beginning writing along with transcription skills, Thus, we believe that the results of this present study do indeed lend support to their theory at the stage of beginning writing. The Not-So-Simple View (Berninger & Winn, 2006) also stresses the increased role of multiple, more complex functions, such as the link between working memory and long-term memory and the reliance on strategies for self-monitoring and self-regulation for older students; however these particular executive functions were not assessed in the current study. This may represent an area of further exploration at the younger grades.

Despite the prevailing focus on early literacy skills in schools, particularly in kindergarten through third grade, concerns remain. Namely, the amount of explicit instruction in many of these component skills, as well as in writing instruction, in kindergarten may be lacking. Graham et al. (2012) have recommended students in kindergarten spend at least 30 minutes daily writing and developing writing skills. However, Kent, Wanzek, and Al Otaiba (2012) have observed that only 10% (9 minutes) of an appropriated 90 min kindergarten literacy block was allocated to writing instruction, including spelling and handwriting instruction and only 3% explicitly devoted to vocabulary and language development. Additional observational research in kindergarten reported similar amounts of writing instruction, with the majority of time devoted to independent writing rather than teacher instruction such as modeling and group instruction (Puranik, Al Otaiba, Folsom & Greulich, in press). Further, handwriting instruction was observed for less than 2 min across fall and spring observations. If such skills have a clear link to writing development (e.g., Graham et al., 2012), increased instructional attention would be warranted at this early level.

Limitations

Several limitations to the present study should be mentioned. The sample for this study comes from a single school district in the southeast. Although relatively diverse, there were few English Language Learners. In order to have more confidence in the conclusions drawn from these analyses, cross-validation with a different sample would be warranted. Second, although several aspects of writing were assessed, both within fluency and quality, this data was drawn from only a single writing sample in the spring of kindergarten and first grade. Moreover, these writing prompts and the time students were allowed to respond differed. In kindergarten, there was little research guidance to inform the choice of prompt, but for first grade, a CBM-W prompt used in prior research was used. Kindergarten students had more time to respond to the writing prompt. Further, at kindergarten, it was not possible to code correct word sequences; thus differences in the prompts, the time, or scoring methods could have impacted the correlation between writing at both times. The inclusion of multiple samples of student writing, via both authentic and direct assessment, may have increased measurement reliability. Additionally, the presence of a floor effect on the writing sample in kindergarten (about twenty percent deemed unscorable), although attributable to developmental constraints, may have served to decrease the resulting relationships among component skills and writing. Third, only a teacher rating of attention/self-regulation was included in the study. Although the SWAN appears to capture distinct factors related to attention regulation (Saez et al., 2012) further research using additional, more direct measures of executive functioning and self-regulation and their relationship to writing production and quality would be warranted. This might include direct observations of student and teacher behavior during writing tasks (e.g., teacher scaffolding and student planning, reviewing, revising) or the utilization of new technology that allows researchers to record student verbalizations (i.e., self-talk) when engaged in the process of writing which may reflect early attempts at self-regulation.

Future Directions

In the present study, a model of early components of writing that included attention as well as early literacy and language skills accounted for more variance in writing fluency than in studies without this component (Kim et al, 2011; Puranik & Al Otaiba, 2012). Nonetheless, there is still much unexplained variance. It is possible that early writing models could be advanced by examining the role of instructional factors alongside student-level factors. While Kim et al. (2013) recently found that instructional quality during reading and writing instruction in first grade was not uniquely predictive of writing outcomes after accounting for student-level factors, specific research has demonstrated that writing outcomes can be influenced by time allocated to writing instruction (Mehta et al., 2005) and quality of instruction in writing (Moats, Foorman, & Taylor, 2006). However, research has also demonstrated the relative dearth of time allocated to writing instruction in the early grades (Puranik et al., in press; Kent et al., 2012; Mehta et al., 2005). Thus, there is a continued need for research examining specific instructional “ingredients” that promote early writing skills, particularly when examined in a model accounting for individual differences in student skills. The examination of additional student-level factors may also be warranted, such as student attitude or self-efficacy regarding writing. Given its’ complex nature, it reasons that individuals who have greater belief and judgment regarding their ability to complete given writing tasks may demonstrate increased willingness to engage in the task and be more persistent. To date, studies have shown the positive relationship of self-efficacy to writing for students in upper grades (Shell, Colvin, & Bruning, 1995) but we know little about the impact on writing at the earliest grade levels.

In conclusion, the results from the present study offer preliminary findings substantiating the role of attention, as well as early literacy and language skills, in the development of writing fluency and quality in the earliest grades. While further validation is necessary, these findings help provide additional evidence as the field moves toward a more complete understanding of writing development and ways in which such development can be promoted.

Acknowledgments

This research was supported by Grant P50HD052120 from the National Institute of Child Health and Human Development, and Grant R305B04074 from the Institute of Education Sciences. Dr. Petscher’s time was also supported by Grant R305F100005 from the Institute of Education Sciences. The content is solely the responsibility of the authors and does not necessarily represent the official views of the National Institute of Child Health and Human Development, the National Institutes of Health, or the Institute of Education Sciences.

Footnotes

A CFA with a single factor “literacy” variable was also conducted resulting in significantly worse fit than either the correlated factor or higher-order factor model.

Contributor Information

Shawn Kent, Florida Center for Reading Research and School of Teacher Education, Florida State University.

Jeanne Wanzek, Florida Center for Reading Research and School of Teacher Education, Florida State University.

Yaacov Petscher, Florida Center for Reading Research.

Stephanie Al Otaiba, Simmons School of Education and Human Development at Southern Methodist University.

Young-Suk Kim, Florida Center for Reading Research and School of Teacher Education, Florida State University.

References

- Abbott RD, Berninger VW. Structural equation modeling of relationships among development skills and writing skills in primary- and intermediate-grade writers. Journal of Educational Psychology. 1993;85:478–508. [Google Scholar]

- Abbott RD, Berninger VW, Fayol M. Longitudinal relationships of levels of language in writing and between writing and reading in grades 1 to 7. Journal of Educational Psychology. 2010;102(2):281–298. [Google Scholar]

- Al Otaiba S, Connor CM, Folsom JS, Greulich L, Meadows J, Li Z. Assessment data-informed guidance to individualize kindergarten reading instruction: Findings from a cluster-randomized control field trial. Elementary School Journal. 2011;111:535–560. doi: 10.1086/659031. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- American Psychiatric Association. Diagnostic and statistical manual of mental disorders (4th ed.) Washington, DC: Author; 1994. [Google Scholar]

- Asparouhov T. General multi-level modeling with sampling weights. Communications in Statistics: Theory and Methods. 2006;35:439–460. [Google Scholar]

- Barkley R. Linkages between attention and executive functions. In: Lyon GR, Krasnegor N, editors. Attention, memory, and executive functions. Baltimore, MD: Brookes; 1996. pp. 307–326. [Google Scholar]

- Bereiter C, Scardamalia M. The psychology of written composition. Hillsdale, NJ: Lawrence Erlbaum; 1987. [Google Scholar]

- Berninger VW, Abbott RD, Abbott SP, Graham S, Richards T. Writing and reading: Connections between language by hand and language by eye. Journal of Learning Disabilities. 2002;35:39–56. doi: 10.1177/002221940203500104. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Berninger VW, Abbott R, Jones J, Wolf B, Gould L, Anderson-Youngstrom M, Apel K. Early development of language by hand: Composing, reading, listening, and speaking connections; three letter-writing modes; and fast mapping in spelling. Developmental Neuropsychology. 2006;29(1):61–92. doi: 10.1207/s15326942dn2901_5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Berninger VW, Rutberg J. Relationship of finger function to beginning writing: Application to diagnosis of writing disabilities. Developmental Medicine & Child Neurology. 1992;34:155–172. doi: 10.1111/j.1469-8749.1992.tb14993.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Berninger VW, Winn WD. MacArthur CA, Graham S, Fitzgerald J, editors. Implications of advancements in brain research and technology for writing development, writing instruction, and educational evolution. Handbook of Writing Research. 2006 [Google Scholar]

- Blair C. School readiness: Integrating cognition and emotion in a neurobiological conceptualization of children's functioning at school entry. American Psychologist. 2002;57(2):111–127. doi: 10.1037//0003-066x.57.2.111. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Byrne B, Fielding-Barnsley R. Evaluation of a program to teach phonemic Awareness to young children: A one year follow up. Journal of Educational Psychology. 1993;85:104–111. [Google Scholar]

- Byrne B, Wadsworth S, Corley R, Samuelsson S, Quain P, DeFries JC, Olson RK. Longitudinal twin study of early literacy development: Preschool and kindergarten phases. Scientific Studies of Reading. 2005;9:219–235. [Google Scholar]

- Chenault B, Thomson J, Abbott RD, Berninger VW. Effects of prior attention training on child dyslexics' response to composition instruction. Developmental Neuropsychology. 2006;29(1):243–260. doi: 10.1207/s15326942dn2901_12. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Common Core State Standards Initiative. Common core state standards for English language arts & literacy in history/social studies, science, and technical subjects. 2010 Retrieved from http://www.corestandards.org/assets/CCSSI_ELA%20Standards.pdf.

- Duncan GJ, Dowsett CJ, Claessens A, Magnuson K, Huston AC, Klebanov P, Pagani LS, Feinstein L, Engel M, Brooks-Gunn J, Sexton H, Duckworth K, Japel C. School readiness and later achievement. Developmental Psychology. 2007;43:1428–1446. doi: 10.1037/0012-1649.43.6.1428. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ehri LC. Learning to read and learning to spell: Two sides of a coin. Topics in Language Disorders. 2000;20:19–36. [Google Scholar]

- Fitzgerald J, Shanahan T. Reading and writing relations and their development. Educational Psychologist. 2000;35:39–50. [Google Scholar]

- Graham S, Berninger VW, Abbott RD, Abbott SP, Whitaker D. Role of mechanics in composing of elementary school students: A new methodological approach. Journal of Educational Psychology. 1997;89:170–182. [Google Scholar]

- Graham S, Bollinger A, Booth Olson C, D’Aoust C, MacArthur C, McCutchen D, Olinghouse N. Washington, DC: National Center for Education Evaluation and Regional Assistance, Institute of Education Sciences, U.S. Department of Education; 2012. Teaching elementary school students to be effective writers: A practice guide (NCEE 2012-4058) Retrieved from http://ies.ed.gov/ncee/wwc/publications_reviews.aspx#pubsearch. [Google Scholar]

- Graham S, Harris KR. The role of self-regulation and transcription skills in writing and writing development. Educational Psychologist. 2000;35:3–12. [Google Scholar]

- Graham S, Harris KR, McKeown D. The writing of students with learning disabilities, meta-analysis of self-regulated strategy development writing intervention studies, and future directions: Redux. In: Swanson L, Harris KR, Graham S, editors. Handbook of learning disabilities. 2nd ed. New York: Guilford Press; 2013. pp. 405–438. [Google Scholar]

- Graham S, McKeown D, Kiuhara S, Harris KR. A meta-analysis of writing instruction for students in the elementary grades. Journal of Educational Psychology. 2012;104:879–896. [Google Scholar]

- Graham S, Perin D. A meta-analysis of writing instruction for adolescent students. Journal of Educational Psychology. 2007;99:445–476. [Google Scholar]

- Happaney K, Zelazo PD, Stuss DT. Development of orbitofrontal function: Current themes and future directions. Brain and Cognition. 2004;55(1):1–10. doi: 10.1016/j.bandc.2004.01.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hooper SR, Costa L, McBee M, Anderson KL, Yerby DC, Knuth SB, Childress A. Concurrent and longitudinal neuropsychological contributors to written language expression in first and second grade students. Reading and Writing. 2011;24:221–252. [Google Scholar]

- Hooper SR, Swartz CW, Wakely MB, de Kruif RenéeEL, Montgomery JW. Executive functions in elementary school children with and without problems in written expression. Journal of Learning Disabilities. 2002;35(1):57–68. doi: 10.1177/002221940203500105. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jones D, Christensen CA. Relationship between automaticity in handwriting and students’ ability to generate written text. Journal of Educational Psychology. 1999;91:44–49. [Google Scholar]

- Juel C. Learning to read and write: A longitudinal study of 54 children from first through fourth grades. Journal of Educational Psychology. 1988;80:437–447. [Google Scholar]

- Juel C, Griffith PL, Gough PB. Acquisition of literacy: A longitudinal study of children in first and second grade. Journal of Educational Psychology. 1986;78:243–255. [Google Scholar]

- Kent SC, Wanzek J, Al Otaiba S. Print reading in general education kindergarten classrooms: What does it look like for students at-risk for reading difficulties? Learning Disabilities Research and Practice. 2012;27(2):56–65. doi: 10.1111/j.1540-5826.2012.00351.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kim Y-S, Al Otaiba S, Folsom JS, Greulich L. Language, literacy, attentional behaviors, and instructional quality predictors of written composition for first graders. Early Childhood Research Quarterly. 2013;28:461–469. doi: 10.1016/j.ecresq.2013.01.001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kim Y-S, Al Otaiba S, Folsom JS, Greulich L, Puranik C. Evaluating the dimensionality of first grade written composition. Journal of Speech, Hearing, and Language Research. doi: 10.1044/1092-4388(2013/12-0152). (in press). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kim Y, Al Otaiba S, Puranik C, Folsom JS, Greulich L, Wagner RK. Componential skills of beginning writing: An exploratory study. Learning and Individual Differences. 2011;21:517–525. doi: 10.1016/j.lindif.2011.06.004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kline RB. Principles and practice of structural equation modeling. Second edition. New York, NY: Guilford Press; 2011. [Google Scholar]

- Lehto JE, Juuiärvi P, Kooistra L, Pulkkinen L. Dimensions of executive functioning: Evidence from children. British Journal of Developmental Psychology. 2003;21:59–80. [Google Scholar]

- Lembke E, Deno SL, Hall K. Identifying an indicator of growth in early writing proficiency for elementary school students. Assessment for Effective Intervention. 2003;28:23–35. [Google Scholar]

- McMaster KL, Du X, Pestursdottir AL. Technical features of curriculum-based measures for beginning writers. Journal of Learning Disabilities. 2009;42:41–60. doi: 10.1177/0022219408326212. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mehta PD, Foorman BR, Branum-Martin L, Taylor WP. Literacy as a unidimensional mult ilevel construct: Validation, sources of influence, and implications in a longitudinal study in grades 1 to 4. Scientific Studies of Reading. 2005;9(2):85–116. [Google Scholar]

- McClelland MM, Acock AC, Piccinin A, Rhea SA, Stallings MC. Relations between preschool attention span-persistence and age 25 educational outcomes. Early Childhood Research Quarterly. 2013;28(2):314–324. doi: 10.1016/j.ecresq.2012.07.008. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McCutchen D. Knowledge, processing, and working memory: Implications for a theory of writing. Educational Psychologist. 2000;35:13–23. [Google Scholar]

- Moats L, Foorman B, Taylor P. How quality of writing instruction impacts high-risk fourth graders' writing. Reading and Writing. 2006;19(4):363–391. [Google Scholar]

- National Commission on Writing. Writing: A ticket to work… Or a Ticket Out. New York, NY: College Entrance Examination Board; 2004. Sep, Retrieved from: http://www.collegeboard.com/prod_downloads/writingcom/writing-ticket-to-work.pdf. [Google Scholar]

- Newcomer PL, Hamill DD. Test of language development-primary: 3. Austin, TX: Pro-Ed; 1997. [Google Scholar]

- Northwest Regional Educational Laboratory. 6+1 Trait® Writing. 2011 Retrieved from http://educationnorthwest.org/traits. [Google Scholar]

- Puranik CS, Al Otaiba S. Examining the contribution of handwriting and spelling to written expression in kindergarten children. Reading and Writing: An Interdisciplinary Journal. 2012;25:1523–1546. doi: 10.1007/s11145-011-9331-x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Puranik CS, Al Otaiba S, Sidler JF, Greulich L. Exploring the amount and type of writing instruction during language arts instruction in kindergarten classrooms. Reading and Writing: An Interdisciplinary Journal. doi: 10.1007/s11145-013-9441-8. (in press) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Puranik CS, Lombardino LJ, Altmann LJ. Writing through retellings: An exploratory study of language-impaired and dyslexic populations. Reading and Writing: An Interdisciplinary Journal. 2007;20:251–272. [Google Scholar]

- Rhoades BL, Warren HK, Domitrovich CE, Greenberg MT. Examining the link between preschool social-emotional competence and first grade academic achievement: The role of attention skills. Early Childhood Research Quarterly. 2011;26(2):182–191. [Google Scholar]

- Saez L, Folsom JS, Al Otaiba S, Schatschneider C. Relations among student attention behaviors, teacher practices, and beginning word reading skill. Journal of Learning Disabilities. 2012;45:418–432. doi: 10.1177/0022219411431243. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Salahu-Din D, Persky H, Miller J. Washington, D.C.: National Center for Education Statistics, Institute of Education Sciences, U.S. Department of Education; 2008. The nation’s report card: Writing 2007 (NCES 2008–468) [Google Scholar]

- Shanahan T. Relations among oral language, reading, and writing development. In: MacArthur CA, Graham S, Fitzgerald J, editors. Handbook of Writing Research. New York, NY: The Guilford Press; 2006. pp. 83–95. [Google Scholar]

- Shell DF, Colvin C, Bruning RH. Self-efficacy, attribution, and outcome expectancy mechanisms in reading and writing achievement: Grade-level and achievement-level differences. Journal of Educational Psychology. 1995;87(3):386–398. [Google Scholar]

- Storch SA, Whitehurst GJ. Oral language and code-related precursors to reading: Evidence from a longitudinal structural model. Developmental Psychology. 2002;38(6):934–947. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Swanson J, Shuck S, Mann M, Carlson C, Hartman K, Sergeant J, McCleary R. University of California Irvine, CA; 2006. Categorical and dimensional definitions and evaluations of symptoms of ADHD: The SNAP and SWAN Rating Scales. Unpublished manuscript. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tangel DM, Blachman BA. Effect of phoneme awareness instruction on kindergarten children's invented spelling. Journal of Reading Behavior. 1992;24:233–261. [Google Scholar]

- Thomson JB, Chenault B, Abbott RD, Raskind WH, Richards R, Aylward E, et al. Converging evidence for attentional influences on the orthographic word form in child dyslexics. Journal of Neurolinguistics. 2005;18:93–126. [Google Scholar]

- Torgesen JK, Wagner RK, Rashotte CA. Test of Word Reading Efficiency. Austin, TX: Pro-Ed; 1999. [Google Scholar]

- Wagner RK, Puranik CS, Foorman B, Foster E, Tschinkel E, Kantor PT. Modeling the development of written language. Reading and Writing: An Interdisciplinary Journal. 2011;24:203–220. doi: 10.1007/s11145-010-9266-7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Willcutt EG, Pennington BF, Boada R, Ogline JS, Tunick RA, Chhabildas NA, Olson RK. A comparison of the cognitive deficits in reading disability and attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder. Journal of Abnormal Psychology. 2001;110:157–172. doi: 10.1037//0021-843x.110.1.157. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Woodcock RW, McGrew KS, Mather N. Woodcock-Johnson III Tests of Achievement. Itasca, IL: Riverside Publishing; 2001. [Google Scholar]